Stanford, Millen and Tchenguiz: victims or favoured clients?

“In my opinion, it is quite wrong that a bank can pretend to have money and security which it doesn’t have, generate a false balance sheet and use its own customers to fund acquisition ambitions.” According to the Guardian, the fashion entrepreneur Karen Millen is pursuing a series of legal claims against the Kaupthing estate, together with her ex-husband Kevin Stanford (more on his Icelandic contacts). Millen is of the opinion that Kaupthing wasn’t entirely straight about its position. She might not be the only one to think so – but before it all went to painfully wrong, her ex-husband was indeed very close to the Kaupthing managers. It’s unclear how well informed Stanford kept his ex-wife on their business dealings. He was the financial motor in their cooperation, Millen the creative one.

Millen and Stanford built up a fashion label, the Karen Millen name is still prominent on UK high streets. But the name no longer belongs to her. Millen has lost her name to Kaupthing. She is understandably upset but she isn’t the first designer to lose her/his name to the bankers by being careless about the small print.

From the SIC report and other sources it’s clear that banking the Icelandic way implied bestowing huge favours on a group of chosen clients – in all three banks the banks’ major shareholders and an extended group around them. As so often pointed out on Icelog, these clients got convenant-light and/or collateral-light loans. In some cases the bankers promised their clients that the collateral wouldn’t be enforced – or the collateral were unenforceable for some reason. They were offered a “risk-free business” – ia risk-free for the customer whereas the bank shouldered all the risk and eventual losses. (This screams of breach of fiduciary duty, indeed part of charges brought in some cases by Office of the Special Prosecutor and not doubt more to come.)

After the collapse, some of Kaupthing’s favoured clients have claimed they were victims of Kaupthing’s managers who did not inform them of the bank’s real standing. Karen Millen is the latest to complain of Kaupthing misleading her. She is, understandably, outraged at not being able to use her name for her label. A clever lawyer would have made sure it couldn’t happen. Stanford was evidently very close to the Kaupthing managers, which might have lulled him into the false believe that he didn’t need to be too careful about the wording of the contracts.

How close was Stanford to Kaupthing? Just before the collapse he was the bank’s fourth biggest shareholder and among the largest borrowers – the familiar correlation between large shareholding and huge loans in the Icelandic banks.

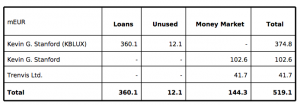

Here is an overview of Stanford’s loans September 2008:

What was this enormous business that Stanford was running that merited loans of €519m?

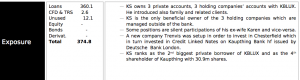

Here is how Stanford was introduced on the loan overview of exposures exceeding €45m:

Pay attention here. Stanford introduced “family and related clients.” – Did he, as sometimes happens, get paid for the introduction? – And then this, that some of this was “silent participation” of his ex-wife and vice versa. Did she have a full insight into how her name was used by her husband? Noticeably, he was the second biggest private borrower in Kaupthing Luxembourg, where all the dodgiest loans were issued.

Stanford’s Icelandic connections are on the whole quite intriguing. He wasn’t only closely connected to Kaupthing but also to Glitnir, at least after Jon Asgeir Johannesson, with ia Hannes Smarason and Palmi Haraldsson, became the bank’s largest shareholder in summer 2007. When Glitnir financed a clever dividend scheme in Byr, the building society, Millen suddenly appeared as one of the stakeholders in Byr. Was that because she was so keen to invest in an Icelandic building society? Some of Stanford’s fashion businesses were joint ventures with Johannesson and his company, Baugur.

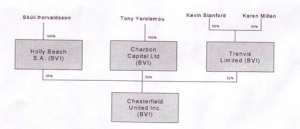

Stanford was also close enough to Kaupthing be part of a clever set-up to influence the bank’s scarily high CDS in the summer of 2008. Together with Olafur Olafsson, Kaupthing’s second largest shareholder, Tony Yerolemou and Skuli Thorvaldsson – all of them in the Kaupthing inner circle in terms of the business opportunities they got from the bank – Stanford and Millen owned one of three companies financed by Kaupthing to buy Kaupthing CDS. This was the set-up:

This scheme doesn’t seem to have hit Stanford and Millen with losses in spite of a loan of €41m to this entreprise.

Last year, Stanford wrote a letter to the Kaupthing Singer & Friedlander estate to substantiate his claim that he should not pay back KSF £130m he had borrowed to buy Kaupthing shares. According to his understanding, this lending was part of Kaupthing’s support scheme, in other words (which Stanford didn’t use) ‘market manipulation.’ – Stanford is and wants to be taken seriously as a business man. Didn’t he see anything strange in the fact that a bank was lending him money, with no risk for Stanford, to buy its own shares, with (if the scheme was the usual one) nothing but the shares as a collateral?

Stanford says that after talking to former Kaupthing Singer & Friedlander staff he now understands that the Kaupthing Edge deposits were used to buy ‘crap’ assets from Kaupthing Iceland, which lent the money on to Kaupthing Luxembourg that then had the money to lend to high net worth clients like Stanford. This scheme, according to Stanford, enabled senior Kaupthing managers to sell their Kaupthing shares.

This is an interesting description of the use of the Kaupthing Edge deposits, which (contrary to Landsbanki’s Icesave) were in a UK subsidiary and consequently guaranteed by the UK deposit guarantee scheme.* Stanford is right that the money was lent to high net worth clients – but not just to any clients: it was lent to the favoured clients who got the conventant-light loans. Kaupthing senior managers may have sold some of their shares but they did by far not sell out – it would have caused too much of attention and undermined trust in the bank.

Other big Kaupthing clients, like Vincent and Robert Tchenguiz, have also complained of being the victims of Kaupthing’s market manipulation. All these people are – or have been – locked in lawsuits with Kaupthing. The claims to the media is part of their PR strategy.

Being duped by Kaupthing means someone did the duping, allegedly the managers of the bank. Yet, none of these ‘ill-treated’ is suing any of the managers. They are suing the failed bank’s estate. That’s logical because the estate has assets. But it also raises the question if the strong bonds, which clearly connected the Kaupthing senior managers and their major clients, have survived the collapse and the consequent losses.

It’s also worth noticing that in spite of enormous loans that the favoured clients got, they have, like Stanford and the Tchenguiz brothers, proved remarkably resilient to losses. That may be due to luck, business acumen or both – but a part of it might also be the convenant- and collateral-light loans that Kaupthing did, after all, bestow on them. Which is part of the Kaupthing-related cases that both the Serious Fraud Office and the OSP are investigating. This way of banking runs against all business logic. The question is what sort of logic it followed.

*The fact that Kaupthing Edge was guaranteed by the UK deposit guarantee seems to be one of the motives for the SFO investigation. I find it incomprehensible that SFO isn’t investigating Landsbanki’s Icesave, which the UK Government did bail out – hence the Icesave dispute.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Sigrún,

The developments you reference above are interesting. More exciting developments in the Kaupþing-KSF-Hedgefund (market manipulators)-British-Regulators-and-Government Saga!! Your information is in addition to that exposing the market manipulating that was going on, which Mike the Nordic Analyst provided example of in his link to a Barclay Capital clients-advisory some blogs back.

For the market manipulating being done by Barclay Capital and its fellow market-shorting players the actions by Kaupþing were share-manipulations, not market manipulations, to manipulate share prices and values(and thence company value) for self-defence. They were, for being responsive, not market manipulations. Their aggressive opponents’ actions were that (the opponents sought to profit by manipulating the shares and values, and the CDS spreads, and so the CDS values). Share manipulations for profit-taking, ostensibly for “hedging” purposes, along with CDS insurance fraud (both trading in CDS policies [by buying, destabilizing the company to widen the spread, then selling] and forcing defaults to collect from the underwriters) were, and are, significant contributors to the destruction of market trust and market confidence that brought the world’s economy to a halt, bringing us all to where we are now.

It will take private lawsuits, like those of Millen and Stanford, and pass-throughs from those, to reach those who began the chain-reactions to straighten the business out, because involved governments, like Britain’s, are not positioned to, and see as their first responsibility damage control, to deflect blame for permitting the manipulators-for-profits to manipulate, so the manipulators-for-self-defence had to ‘participate’ (it is similar to the world of bubbles, where once a bubble is going all have to go along, or become victims of the inflation–it is why regulators are supposed to regulate, instead of taking a cut and looking off whistling, not noticing).

All of the questions you note being raised by the situation need investigating. You being a journalist, I hope you are in the field digging to find answers for the questions you are asking.

There is one error in your presentation which I must draw your attention to. It is important: In your footnote you write, “…Landsbanki’s Icesave, which the UK Government did bail out”. It was not the UK Government, it was the UK’s banking Industry’s Depositor Guarantee Fund, the British private enterprise counterpart of Iceland’s Banking Industry’s TIF, also a private enterprise entity, that agreed, with its Icelandic counterpart, the TIF,to reimburse the Icesave depositors (with, it believed, the Icelandic government sure to agree to co-sign for the TIF as guarantor). The same is the case with the Dutch private enterprise depositor insurer, who made agreement with the TIF and reimbursed for the TIF, who had the responsibility.

We can compare the situation to one of the TIF being a minor child whose older British and Dutch friends lent to, assuming they could take advantage because TIF’s mother, the Icelandic government, would co-sign and see them paid. After some ups and downs mother-government agreed to, but then little TIF’s father, the Icelandic People, said, “NO WAY! The kid wants to play in the big-time, he pays his own bills!”

That the debt is a private debt, between private parties, and the ESA is trying to squirrel the busienss around to make the extraordinary claim that Iceland is the TIF (for parenting [supervising the kid] so closely it somehow has become him), that the ESA is walking into a wall. It is a regulatory authority pretending it is a private firm of lawyers and so can represent the private British and Dutch banking insurance companies, and have its court, the EFTA Court, render a private-case judgment.

[The ESA claim that the government of Iceland did pay the depositors in Iceland is incorrect, because the government of Iceland nationalized the banks in Iceland: It took them away from their owners lock-stock-and-depositor. Thus, the Icelandic depositors were the only ones who were not reimbursed by the TIF, who had the responsibility (there does not seem to be any regulation prohibiting an government from relieving a depositor insurer from its responsibilities, by taking away its insureds’ depositors, and everything else)]

I am very excited to see how the EFTA Court reacts to the ESA’s Application, which has all the marks of having been written by clerks trying to pretend they are clever law-spinners.

R.L.Dogh

25 Mar 12 at 12:50 am