Search Results

The Georgiou case: the ongoing decade-old shameful saga for Greece

Among foreign colleagues and international statistical organisations, the case of the former president of ELSTAT, Andreas Georgiou is a cause for grave concern. After Greece was found to have been falsifying its national statistics for years, Georgiou was appointed as head of ELSTAT to put Greek national statistics in order, which he did during his five-year term, 2010 to 2015. It is a sad sign of deep-running corruption in Greece, that even before his term had ended, Georgiou was fighting prosecutions from public bodies and later from private individuals linked to the Greek statistics before Georgiou took office. Yet, no investigation has ever been done into the real scandal: who organised the falsification of the national statistics in the years before Georgiou was appointed to put them in order?

The Georgiou affair is “a witch hunt, not a thirst for justice,” wrote Nikos Konstandaras columnist at Kathimerini in August 2017 in a rare show of understanding in Greece.

Investigations into Andreas Georgiou’s work started already in 2011, only a year after he took over as head of ELSTAT. The first criminal charges – for alleged inflation of the deficit and for violation of duty when Georgiou revised the previously falsified statistics – were brought in 2013; later there were criminal charges and a civil case for slander, ironically brought by the director of Greek national accounts division at the time the falsifications of Greek national statistics were ongoing. Intriguingly, the falsifications have never been investigated, nor those in charge of statistics at the time, only the public servant who put the necessary system in place to produce correct statistics.*5

The “simple slander” case: truth and punishment

In a civil case, brought against Georgiou by Nikos Stroblos, director of Greek national accounts statistics from 2006 to 2010, Georgiou was found liable by a Greek First Instance Court in 2017 for something called “simple slander.” According to the court decision, Georgiou’s statement in 2014, when he defended the Eurostat-validated revised Greek deficit and debt data for 2006 to 2009, was found to be true. However, it was also found to be damaging to the reputation of Stroblos. Georgiou’s appeal against the First Instance Court decision was – after repeated delays – ruled on by the Appeals Court in January this year and was rejected.

More specifically, in the 2014 press release Georgiou had defended the revised fiscal statistics of 2006 to 2009. In effect, he was defending the statistics produced under his watch, a revision of the statistics that the European Commission/Eurostat in 2010 and the European Parliament in 2014 had characterised as “statistical frauds.”

In his fateful statement, Georgiou was responding to the ongoing politically instigated prosecutions and attacks from most of the Greek political spectrum, on the revised statistics. Statistics, which had already been validated eight times since November 2010, when they were first published by Georgiou.

In his 2014 press release he pointed at both the repeated EU validation of the revised statistics and the EU verdict for the previous misreported statistics, asking why the courts did not instead investigate the previous period of the proverbial “Greek statistics.” Further he asked, why the court only invited those responsible for these misreported statistics, including the plaintiff, as the expert witnesses, and not also the EU officials of Eurostat mandated by law with assessing the quality of European statistics.

Georgiou lost at the first instance civil court level for stating the truth, as recognised by the court, and for defending the validated European statistics as he was required to do by EU and Greek law. He had a justified interest in defending the credibility of the newly reformed statistics office, ELSTAT, and he was exercising his human right of free expression.

The private cases against Georgiou by a former director of the Greek statistics office

The former director of the national accounts division of the Greek statistics office claimed that his reputation had been damaged by Georgiou’s press release. Yet, it was actually this director that had publicly slandered Georgiou and Eurostat as evidenced, for example, in an interview in March 2013.

The former director stated: “the wrong multiplier … is on account of the inflated statistics Georgiou sent to them … so with the inflation and alteration of the statistics they took from the [Greek] people more money than the country could bear! … the temporary postponement of the Greek bankruptcy in order to pay back in full the French and German banks … was the goal of the inflation of the deficit by the Greek Statistical Service following orders from Eurostat.”

Quite remarkably, the January 2021 Appeals Court decision rejecting Georgiou’s appeal omits any reference to this interview. Though repeatedly submitted as evidence to the Appeals Court and to the lower court, the Appeals Court decision claims that the plaintiff “had never expressed in the printed or electronic press accusations against [Georgiou].”

Meanwhile, the March 2013 interview with Stroblos was published again on 18 April 2021 as part of an article that celebrates the recent rejection of the appeal of Georgiou titled “New conviction of Georgiou of ELSTAT!!!” The April article highlights some of Stroblos’ public statements, such as “I refused to undersign the inflation of the deficit” and “Then [the Eurostat section chief] sent an expert … to persuade me to approve the changes [to the deficit calculation]. I refused! The work of the National Statistical Institute is to defend the interests of the country and not the interests of Eurostat!” – An altogether remarkable statement.

According to First Instance Court decision, Georgiou is obliged to both make a public apology, by publishing large parts of the convicting court decision in a specified Greek newspaper at Georgiou’s expense, and pay a compensation of EUR10,000, plus interest since 2014 and court expenses, to Stroblos. In addition, there is fine of EUR200 a day for any delays in publishing the apology. All this was upheld by the Appeals Court in its January 2021 decision.

If this January 2021 decision is appealed to the Greek Supreme Court, it seems that the Court can either return the case to the Appeals Court that Georgiou be tried yet again, a process that can potentially take three or more years – or the Supreme Court can, within months, irrevocably confirm the January decision against Georgiou. This means that there seem to be now only two possibilities left, one worse than the other. Georgiou has decided to appeal.

Political action running parallel to the two private cases against Georgiou

This civil case is an integral part of the overall political persecution of Georgiou in Greece. In the first instance, the case was brought at the same time as a criminal case for criminal slander, both brought by the same plaintiff, the two cases being intertwined. Former government officials volunteered and appeared as witnesses for Stroblos in both the civil case and the criminal case and the criminal case conviction[i] was cited during the civil trial.

The two cases were a combined criminal and civil broadside against Georgiou to undermine credible statistics. Common sense, as well as evidence of political intervention,[ii] indicates that these cases are part and parcel of the stream of persecution that has trailed Georgiou for accurately producing European statistics for Greece.

A closer look at the media coverage makes it clear that since 2011, the slander cases have been at the core of the attacks on Georgiou for heading and defending the revision of the 2009 deficit figures. Attacks, levelled by both major political parties as they alternated in power.

There is no lack of examples. Press reports (in Greek), at the time of Georgiou’s press release, titled “Dissatisfaction in Maximos Mansion [PM Antonis Samaras’ office] for the statements of the head of ELSTAT” noted: “the statements of the president of the Hellenic Statistical Authority, Andreas Georgiou, caused irritation at the Ministry of Finance and at the Maximos Mansion. Government sources stressed that “it is not appropriate for an administrator to express such judgments”. At the same time, Prokopios Pavlopoulos, a former top minister of the 2004 to 2009 New Democracy government and later president of Greece nominated by the SYRIZA government, initiated in the Greek Parliament Committee on Institutions and Transparency a successful vote, with support from both New Democracy and SYRIZA MPs in the Committee, to ask for Georgiou’s removal on account of his July 2014 press release but Georgiou’s removal was successfully resisted by Greece’s European partners.

It is hardly a coincidence that only a few weeks later, Stroblos filed his two suits against Georgiou. Stroblos not only used the above parliamentary committee’s decision as a pillar of his legal case. He has continuously been encouraged and tangibly supported by Greek political figures who have acted as trial witnesses and lawyers in his cases against Georgiou.[iii]

The trials of Georgiou for slander were used to publicly defend the pre-2010 government’s misreported deficit and debt statistics, to exonerate this past statistical fraud, and to attack the revised European statistics produced by ELSTAT under Georgiou in 2010 and repeatedly validated by Eurostat in the years since. For example, during one of the trials, a former General Secretary of the Ministry of Finance from the 2004 to 2009 Karamanlis government testified as a prosecution witness, among other things, that “in the period 2004-2009 no intervention in the statistics took place.” This patently false statement was highlighted and widely publicised in politically friendly press coverage of the trials.

The Greek government funds the plaintiff’s case against Georgiou in spite of its promise to the ECB

Quite shockingly, during SYRIZA’s time in government, the government funded a significant part of Stroblos’ legal fees, which seems a misuse of the law and a perversion of the original intent of the law under which the funds were provided.

In the midst of Georgiou’s political persecution, the European Central Bank, ECB, and the Eurozone Finance Ministers pressed the Greek Government to provide funding to assist Georgiou in defending his statistics against the legal actions in Greece. As previously reported on Icelog, leaked minutes from the Eurogroup meeting 22 May 2017 show that ECB governor Mario Draghi brought the ELSTAT case up at the beginning of the meeting, asking that, as agreed earlier, priority should be given to implementing “actions on ELSTAT that have been agreed in the context of the programme. Current and former ELSTAT presidents should be indemnified against all costs arising from legal actions against them and their staff.”

Greek minister of finance Euclid Tsakalotos said that “On ELSTAT, we are happy for this to become a key deliverable before July.”

Though crystal clear that this legal provision was to be specifically directed to assist “current and former ELSTAT presidents” against legal actions arising against them, the Greek government perverted this intent. The law was used to also fund the misguided efforts of an individual, challenging the very statistics the ECB and Eurogroup sought to defend. A stunning perversion of the intended purpose of these funds, underscoring that the Greek Government has funded, at least in part, an effort to continue the persecution of Georgiou.

Praise from foreign statisticians and organisations, persecution by Greek political forces

In stark contrast to the persecutions in Greece, Georgiou’s case has over the years had the attention of individuals and organisations all over the world: the IMF, the European Union, Eurostat, the American Statistical Association, the International Statistical Institute and the International Association for Official Statistics. All these individuals and organisations point out the gravity of the matter: that a public servant, involved in the gathering and processing of national statistics, the lifeblood of any modern state, suffers persecution for his work.

In early April this year, the German Süddeutsche Zeitung brought an article on Georgiou’s case, pointing out the support he gets abroad is the opposite of course of events in Greece.

It is also noteworthy that under the headline “Denial of Fair Public Trial” Georgiou’s case was mentioned in the US State Department’s 2019 and 2020 Country Reports on Human Right Practices. The 2019 Report stated:

Observers reported the judiciary was at times inefficient and sometimes subject to influence and corruption… On February 28, the Council of Appeals cleared, for the third time, the former head of the Hellenic Statistical Authority, Andreas Georgiou, of charges that he falsified 2009 budget data to justify Greece’s first international bailout. The Supreme Court prosecutor had twice revoked his acquittal by the Council of Appeals. Although technically possible, the current government has expressed no interest in revisiting the case. EU officials repeatedly denounced Georgiou’s prosecution, reaffirming confidence in the reliability and accuracy of data produced by the country’s statistical authority under his leadership.

The 2020 Report repeated the statement on the judiciary’s inefficiency and at times subject to influence. Further:

Observers continued to track the case of Andreas Georgiou, who was the head of the Hellenic Statistical Authority during the Greek financial crisis. The Council of Appeals has cleared Georgiou three times of a criminal charge that he falsified 2009 budget data to justify Greece’s first international bailout. At year’s end the government had made no public statements whether the criminal cases against him were officially closed. Separately, a former government official filed a civil suit in 2014 as a private citizen against Georgiou. The former official said he was slandered by a press release issued from Georgiou’s office. Georgiou was convicted of simple slander in 2017. Georgiou appealed that ruling, and at year’s end the court had not yet delivered a verdict.

Given where Georgiou’s case seems to be at, this chapter will still stand for the 2021 Report.

On May 1, Steve Pierson director of science policy at the American Statistical Association and Lynn Wilkinson from Friends of Greece, wrote an article on the AMSTATNEWS website, the ASA magazine, under the headline “ASA, International Community Continue to Decry Georgiou Persecution.” The article gives an overview of the persecution, including the still-ongoing slander case, and points out the false narrative that is being propagated by the continuous prosecutions, as opposed to the work Georgiou did to put in place the proper statistical methods, still the framework at ELSTAT.

Pierson and Wilkinson point out the US State Department’s mention of Georgiou’s case. “Besides the injustice of the prosecutions, the harm to Greece’s reputation, and the undermining of official statistics, Greece’s treatment of Georgiou is also a violation of Georgiou’s human rights.”

“Persecuting a scientific government official for doing his job with rigor and integrity to produce official statistics is deeply concerning,” ASA President Robert Santos said after the Appeals Court in January.

When will the political persecution of a statistician stop in Greece?

One reason Georgiou’s cause has gathered so much interest is the implications in so many countries for civil servants doing their job diligently. And that’s also why his case has been taken up by individuals and organisations. In a tweet March 24, Olivier Blanchard, ex chief economist at the IMF, now a professor emeritus at the MIT, wrote that what is happening to Georgiou is unacceptable. “Now in 10th year, Greece should end the injustice and exonerate him.”

As mentioned above, Georgiou will be appealing the January ruling to the Greek Supreme Court. At the time of the Appeals Court ruling he said: “Certainly, what happens in this case, when it reaches the Greek Supreme Court, will have implications in Greece and in the EU more broadly, for the soundness of future policies that are supposed to be based on honest and reliable official statistics but also for the rule of law, human rights and democracy.“

The implications from the January 2021 rejection of Georgiou’s appeal of the court decision for simple slander, where he was found liable for making true statements, seem truly staggering. How can democracy function when someone who participates in a public debate in order to refute false accusations of grave misdeeds and tells the truth, as the courts accepted he did, is then punished? The whole basis of democracy is free expression and communication of ideas and information for citizens to make their choices.

How can democracy survive when the state suppresses the free expression of ideas and information that are recognised by court as being true? And how can any good policy decisions be made for societies to prosper when truth is suppressed? Furthermore, how can science advance when truth is punished? Is it not evident that EU prosperity but also the functioning and the image of democracy in its realm are at stake? This case is a stain on Greece but a stain that also falls on the European Union, as Greece is a member state, inter alia reporting statistics to Eurostat. It is therefore worrying the EU and EU institutions have recently been silent on the Georgiou case.

[i] The “companion” criminal case for slander led to Georgiou’s conviction to one year in jail but was annulled by the Greek Supreme Court on account of serious legal errors and the statute of limitations did not allow the ordered retrial.

[ii] As an example, in response to Georgiou’s conviction in criminal court for “simple” slander, former Minister of Interior in the 2012 to 2014 New Democracy government, Mr. Michelakis, published an article entitled: “First conviction of A. Georgiou for the “inflated” deficit of 2009.” The article states: “The story of the inflated deficit of 2009 that was reported by George Papandreou and led our country to the Memoranda is beginning to be revealed through court proceedings, effectively vindicating the government of Kostas Karamanlis.”

[iii] Officials that served as witnesses at the trial for slander included George Kouris, former General Secretary of the Ministry of Finance, and Stephanos Anagnostou, former Viceminister to the Prime Minister and Spokesperson of the Government. Both served in New Democracy governments. The lawyer for the plaintiff was Yiannis Adamopoulos, the former president of the Athens Bar association, who had been elected to that post as a New Democracy party member and had played a major role as president of the Athens Bar in instigating the prosecutions of Georgiou about the 2009 deficit figures.

*Icelog has been following the Georgiou case since 2015. Here is an extensive overview, from April 2020, on the whole saga. Here is the first blog, from June 2015, which deals in detail with the statistics, the falsification saga and the adjustments that were made, the last one by Georgiou; this blog was also cross-posted with Fistful of Euros and The Corner. A shorter version was posted on Coppola Comment (thanks to Frances for the edititing!) and Naked Capitalism. – For numerous other Icelog blogs on the case, see here.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

The Georgiou affair: how Greece keeps failing the political corruption test

After the election in Greece last summer, the country seemed to be on a positive path away from populism towards a more stable political environment. Though born into his party New Democracy, the new prime minister, Kyriakos Mistotakis, brought with him the air of the outside world: he had been a banker and consultant in London, before entering Greek politics in the early 2000s. Yet, he seems to stick to the same common thread as his predecessors in office since 2011: the persecution of the former head of ELSTAT, Andreas Georgiou, who took over as the head of the revamped Greek statistical office in August 2010 following the exposure in 2009 of how the national statistics had been falsified. Intriguingly, Georgiou and his staff have been persecuted relentlessly by political forces, whereas the falsification of the national statistics has not even been investigated at all. And not only that: those in positions of responsibility for the statistics from the time of falsified statistics sued Andreas Georgiou for slander and won at first instance civil court in 2017; since then, Georgiou’s hearing to appeal this decision has been continuously postponed, most recently to September 2020.

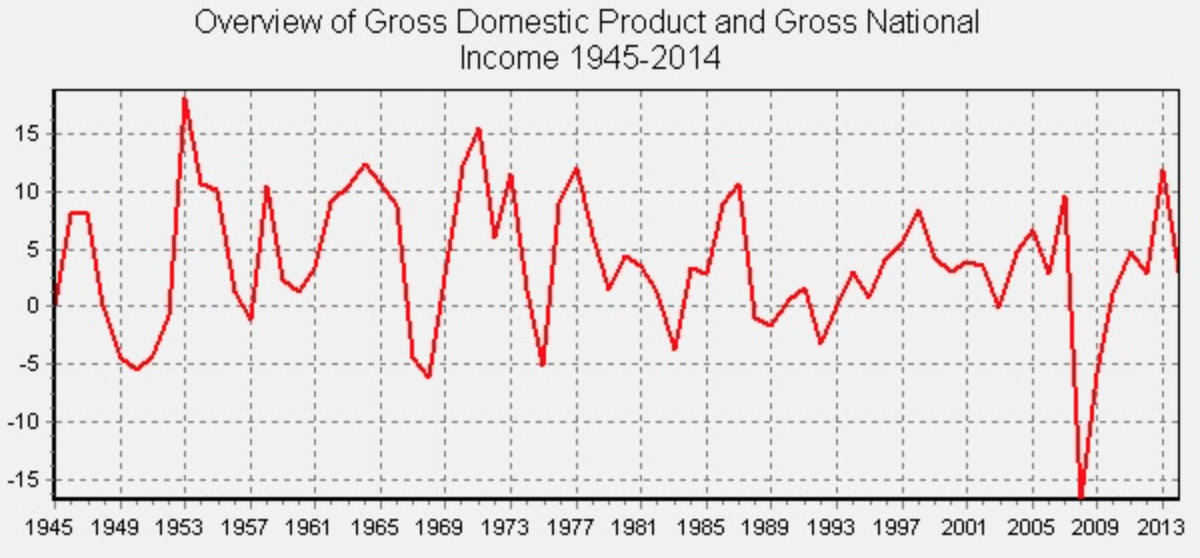

Just like Icelanders, Greeks earned a lot of sympathy when Greece tumbled into a financial crisis in 2009. But the Greek crisis exposed that the political ruling class in Greece had, since the end of the 1990s, falsified the Greek national statistics, i.e. the government deficit and debt were considerably higher than the published figures showed. For example, the deficit in 2006, 2007 and 2008 had been presented in official Greek statistics in mid-2009, just before the Greek crisis erupted, at 2.8%, 3.6% and 5% of GDP, respectively. However, the real figures, which were calculated by ELSTAT, the reformed statistical office, in 2010, were about double that, reaching 6.2%, 6.8% and 9.9% of GDP, respectively. And the government debt, which had been misreported at oscillating from 96 to 99% of GDP those years, was actually rising and had reached 110% of GDP by end 2008.

After years of legal wrangling, there seems to be no end in sight of the persecutions of the statistician who put Greek statistics on the path stipulated by European regulations on national statistics. Persecutions, which are an affront to Greek and European rule of law on many counts. If the Greek Government of Mitsotakis wants to confirm that the bad habits of falsified statistics are well and truly over and that Greece is firmly in the core of the European Union, it should give the Greek courts an opportunity to right a wrong and to exonerate Andreas Georgiou instead of punishing him for doing his job according to the European and Greek law.

Exposed: Greek statistical frauds… from 1997 to 2003

Greek statistics, as they are now for the years before the crisis hit, are not what Greek statistics were showing before autumn of 2009. Not for the first time, there was a lingering suspicion that not all was well with Greek statistics. Before joining the euro in 2001, the Greek budget deficit and public debt dived miraculously low, well below their less glorious average in the years before joining the euro. Although only the deficit figure ever went below the required Maastricht criteria, Greece was allowed to join the euro.

The lingering suspicion was there for a reason. Already in 2004 Eurostat had discovered that the debt and deficit dip around the euro entry was no miracle but manipulation: Greek authorities simply reported the wrong figures. In 2004, Eurostat’s Report on the revision of the Greek government deficit and debt figures showed that this had been an on-going story from 1997 to 2003.

Consequently, the Greek statistical authorities, the then National Statistical Service of Greece, NSSG, was forced to revise its data upward for the years 1997 to 2003, including for the test year of 1999 for Greece’s entry into the Eurozone, above the criteria set by the EU for Greece: Revisions in statistics, and in particular in government deficit data, are not unusual… However, the recent revision of the Greek budgetary data is exceptional.” – The unusual aspect was that the wrong figures did not stem from missing or faulty data but from deliberate misreporting. The real figures were dismal so “better” figures, even though wrong, were reported.

Exposed again in 2009: repeated falsifications of national statistics

After the exposure in 2004, Greek statistics were under intense and unprecedented scrutiny. But NSSG was not prepared to abandon its earlier bad practices. In autumn 2009 the ECOFIN Council requested a new report, this time from the EU Commission, due to “renewed problems in the Greek fiscal statistics” after the “reliability of Greek government deficit and debt statistics (has) been the subject of continuous and unique attention for several years.”

Greek figures on debt and deficit had, yet again, significant problems: First, deficit forecasts for 2009 changed drastically between March 2009 and September 2009 and then the forecasts changed again even further in October 2009. Regarding the actual statistics, the EC report on Greek Government Deficit and Debt Statistics, published in January 2010, showed that the statistics for the actual 2008 deficit had been revised upward significantly (by 2.7 % of GDP). Again, as the report pointed out, such a revision was rare in EU member states “but have taken place for Greece on several occasions.” Once the real statistics for 2009 were available in April 2010, the numbers proved to be higher than any of the projections provided earlier and previous years’ statistics were again revised upwards.

As earlier, the faulty statistics had not been produced solely at the NSSG but were also made with components produced at the General Accounting Office (GAO) and other parts of the Ministry of Finance, as well as other public sector institutions responsible for providing data to NSSG. There was political interference and “deliberate misreporting” with the NSSG, GAO, MoF and other institutions involved in the reporting all playing their part, according to the January 2010 EC report. In total, the word “misreporting” was used eight times in the report.

Events before the setting up of ELSTAT and Georgiou’s time there

The Goldman Sachs, GS, off-market swap story was one chapter in the faulty statistics saga and one of many examples of misreporting affecting government deficit and debt statistics. In 2008, when Eurostat made official enquiries in all member states on off-market swaps, Greek authorities informed Eurostat promptly that the Greek state had engaged in nothing of the sort.

This statement turned out to be a blatant lie as Eurostat found out when investigating the matter in 2010; the findings were published in a Eurostat report (p.16) in November 2010. By 2009, this misreporting was understating the level of the Greek government debt by 2.3 percent of GDP. As with many other examples of faulty statistics, this misreporting, on the off-market swaps and the ensuing effect on government debt, was not a single event but a deceit running for years, in this case since 2001, where several Greek government agencies played their part.

Needless to say, fiddling with the numbers did not eradicate the actual debt and deficit problem. While this deceit was being uncovered in the last quarter of 2009 and early 2010, Greece was losing access to markets. Negotiations on a bailout were complicated by unreliable information on Greek public finances. On May 2, 2010, as the first Greek Memorandum of Understanding was signed, accompanied by a €110bn loan – €80bn from European institutions and €30bn from the IMF – it was clear that the crucial figures of debt and deficit might still go up.

Following these major failures at the NSSG, its head had resigned in mid-October 2009. With the new government of George Papandreou taking office in early October 2009, there were changes at the leadership of the MoF and the GAO, with a new minister, vice minister and general secretaries. However, the ranks below remained unchanged, as did the mentality.

With a new government and following these exposures the laws on official statistics were changed in the spring of 2010. NSSG was abolished, replaced by a new statistical office, ELSTAT. Andreas Georgiou, who having been with the IMF for more than 20 years, returned home to be the head of the new statistical office. After Georgiou took over, the last upward revisions to government deficit and debt data were done.

The context of the 2009 deficit and the statistical adjustments 2009 to 2010

It is important to keep in mind the context for the 2009 deficit: there was the forecasted deficit of 3.9% of GDP, put forth by the MoF and conveyed to the European Commission by NSSG in April 2009 and then the estimate of the actual 2009 deficit of 13.6%, as produced and reported by NSSG in April 2010. All of this, an upward adjustment of almost 10 percentage points of GDP, took place before Georgiou took over at ELSTAT in August 2010.

With the 2009 deficit number of 13.6% in April 2010, way up from the originally forecasted 3.9%, it was still clear and publicised by Eurostat that the final figure could be higher. As indeed it was: the final adjustment from 13.6% to 15.4% was made by Georgiou and his team. The actual monetary figure behind the last revision of the deficit figure was about 4 billion euro.

This final adjustment made by Georgiou and his team seemed at the time wholly innocuous and a straightforward continuation of the earlier and much larger adjustments. But things were changing in Greece, though not in the direction of what those hoping for new and better times in Greece, would have hoped for.

The worm pit of Greek politics

Greek politics was a veritable worm pit during these months of fears over the country’s finances as the Papandreou government negotiated rescue packages and bailouts – in May 2010 and in June 2011 – with the IMF and European institutions.

After the elections that New Democracy lost in early October 2009, Antonis Samaras replaced the long-standing and earlier so powerful leader of the party of 12 years, Kostas Karamanlis. Karamanlis had been prime minister from 2004 until he lost the elections in 2009, that is during the time of the second round of the fraudulent statistics. In a much-noted speech in September 2011, Samaras attacked George Papandreou, accusing him of manipulating the statistics after Papandreou came to power in 2009, claiming Papandreou had done this only to discredit Kostas Karamanlis. This speech proved fateful, not for Papandreou but for ELSTAT’s president Andreas Georgiou.

Shortly after the Samaras’ speech, Georgiou was called to the parliament to explain the revision of the deficit and debt figures he had done. He was accused of ignoring national interests and inflating the 2009 figures under instruction of Eurostat to push Greece into the Adjustment Programme, set up to save the Greek state.

This narrative ignored four facts: the main corrections had been done before Georgiou took over at ELSTAT; Georgiou followed the same European regulation on national accounts statistics (Regulation 2223/96) and the same European Statistics Code of Practice as all other statistical offices in the EU; Greece had entered the Adjustment Programme three months before Georgiou took over at ELSTAT; Greece had repeatedly reported faulty data up to 2004 and then again up to end of 2009.

Political figures both on the left and the right of the political spectrum united against the ELSTAT president as if the only reason for the country’s debt and deficit problems were the statistics. The Greek Association of Lawyers even accused Georgiou of high treason.

Politicians unite in finding a scapegoat for the crisis: ELSTAT staff

In addition to the parliamentary hearing, the Samaras’ speech sat another thing in motion: a prosecutor opened a case against Georgiou and two ELSTAT managers and eventually pressed criminal charges in January 2013. In August 2013 an investigating judge recommended that the case be dropped as nothing was found to merit taking the case further.

However, political interventions, out in the open for all to see, kept the case alive in the Greek judicial system where it has been like a yo-yo: two additional times, in 2014 and 2015, prosecutors proposed that the case be dropped. However, what followed were interventions from nearly all sides of the political spectrum, fuelling the narrative of “false statements on the 2009 deficit and debt,” thus allegedly causing the Greek state to suffer staggering damages. A narrative that pushed the case to trial where the punishment should be relative to the damages, calculated to amount to €171bn, effectively amounting to a prison sentence for life.

In 2015 the charges against Georgiou and two ELSTAT managers, for allegedly making false statements on the 2009 statistics, were dropped by the Appeals Court Council after proceedings behind closed doors. However, this decision was annulled by the Supreme Court in 2016 after a proposal by Greece’s Chief Prosecutor and the Appeals Court Council, with new members, had to reconsider the case.

In 2017, the Appeals Court Council decided again to drop the charges, but the Supreme Court yet again annulled the decision, following yet another proposal for annulment by the Chief Prosecutor, an extraordinary move in Greek legal history. Then, in March 2019, the Appeals Court Council, under yet a new composition, decided for a third time to drop the charges against Georgiou and two senior staff regarding the alleged inflation of the deficit. This time, the decision was not annulled by the Supreme Court.

An acquittal that did not end the case

However, charges against Georgiou for alleged violation of duty, for not bringing the 2009 revised deficit and debt figures to a vote by the former board of ELSTAT before their publication in November 2010, were upheld. This, despite proposals to the contrary, by various investigating judges and prosecutors assigned to the case on three different occasions, in 2013, 2014 and 2015. Eventually, Georgiou was tried in open court in 2016 and acquitted.

However, this acquittal did not put an end to the case: ten days later, and before even the rationale of the acquitting decision had been made available, another prosecutor annulled the acquittal and Georgiou had to be retried in a “Double Jeopardy” trial in 2017. He was convicted to two years in jail, a suspended sentence unless he gets another conviction within three years. Georgiou appealed to the Greek Supreme Court, but his appeal was rejected, and the conviction sustained in a 2018 Supreme Court decision.

In court, Georgiou had argued that he was following both Greek and EU law, which refer to the European Statistics Code of Practice, making it clear that the head of the statistical authority has the “sole responsibility for deciding on statistical methods, standards and procedures, and on the content and timing of statistical releases”.

Georgiou requested the Greek courts to put – as provided in the Treaties – a pre-trial question to the European Court of Justice on the matter of the interpretation of the European Statistics Code of Practice in this matter; the courts ignored Georgiou’s request. Instead the convicting decision chose to use a blatantly false translation and interpretation of the European Statistics Code of the Practice asserting that “sole responsibility for deciding” does not really mean what is stated in the Code.

It seems safe to conclude that the conviction of Andreas Georgiou to two years in jail for not putting up the revised deficit and debt statistics to a vote does not rhyme with Greek and European rule of law. If the Greek Government of Mitsotakis wanted to set Greece back on the right track in this fundamental area and show that Greece is firmly in the core of the EU, it should initiate a re-examination of the case and give the Greek courts an opportunity to right a wrong and to exonerate Andreas Georgiou as he did his job according to the European and Greek law.

Further, two criminal cases

There are also two other ongoing criminal cases in Greece involving Andreas Georgiou.

In September 2016, the Chief Prosecutor of Greece ordered a new, preliminary criminal investigation into allegedly the 2009 deficit figures. This case, not the same as the case in which Georgiou and the two ELSTAT staff were acquitted in 2019, implicated not only Georgiou and the two ELSTAT staff for inflating the deficit figures but also officials from the European Commission, Eurostat and the IMF. So far, no charges have been pressed and Georgiou has not been summoned by the assigned prosecutor.

Another criminal case against Andreas Georgiou is with regard to his requesting ELSTAT staff in 2013 to sign a statistical confidentiality declaration, as required under the European Statistics Code of Practice, Indicator 5.2, for the purpose of protecting the private information of households and enterprises. There were two separate preliminary criminal investigations initiated in mid-2013 related to the Code, later combined into one. To this date no charges have been pressed but, as with the above-mentioned case, there is no evidence that the case has been closed.

If Greece and its political class wants to stop the scapegoating, all these cases against Andreas Georgiou ought to be dropped.

In addition to criminal cases: civil cases

In 2014, a civil case for criminal slander was brought against Georgiou. The plaintiff was Nikos Stroblos, who had been director of national accounts of the Greek statistics office in 2006 to 2010. Stroblos claimed Georgiou had engaged in criminal slander when he, as head of ELSTAT issued a press release in 2014, defending the final revised 2009 deficit and debt statistics produced by ELSTAT after Georgiou took over. The press release was published because of the legal proceedings since 2011 and the continuous attacks from most of the Greek political spectrum.

In 2017, the First Instance Civil Court decided that Georgiou had committed what is called in Greek legal terminology “simple slander,” meaning that what Georgiou said in his press release was true but had hurt the plaintiff’s reputation, (as opposed to “criminal slander”, whereby false statements are made to hurt somebody’s reputation). Thus, the court decided that Georgiou told the truth but he should not have made the statement he did. To atone for this, Georgiou was obliged to pay a compensation to the plaintiff and make a public apology in the Greek newspaper, Kathimerini, in the form of publishing large parts of the court decision against him.

When Georgiou appealed the decision, things took a peculiar turn: the appeal hearing has been postponed time and again. The last delay happened in January this year: the case was scheduled for January 16 but then postponed, for more than nine months, until September 24, 2020.

There is a peculiar irony here: Georgiou is appealing a court decision that found him guilty of “simple” slander for publicly defending his agency’s work; in layman’s terms, he was found liable for making true statements that happened to hurt someone’s reputation, an actual crime in Greece. If found liable, the person who restored the credibility of Greek statistics will have to publicly apologize to the person who was fudging the data previously and pay him compensation. This outcome would further damage Greece’s troubled image in the eyes of the global community.

European Convention on Human Rights: cases should be heard within a reasonable time

Now, six years after this civil case started, and nine years after Georgiou was first put under investigation, he and his family are still living with these never-ending court proceedings and the eternal postponements. It is of interest to keep in mind Article 6.1. of the European Convention on Human Rights: In the determination of his civil rights and obligations or of any criminal charge against him, everyone is entitled to a fair and public hearing within a reasonable time by an independent and impartial tribunal established by law.

Interestingly, one of Stroblos’ witnesses in the civil suit against Georgiou is Nikos Logothetis, who was vice-chairman of the board of ELSTAT when the board had demanded to vote on the revised 2009 deficit and debt figures in November 2010. Only weeks earlier, Logothetis was forced to resign from the ELSTAT board after the Greek police found that Logothetis had hacked Georgiou’s private email. A criminal investigation was opened against Logothetis at that time and in early 2011 two charges, of felony and misdemeanour, were pressed against him.

However, both cases against him were dropped for reasons that are difficult to fathom in the context of the rule of law and how Georgiou’s cases have fared in the Greek courts: one case was dropped as the court did not consider it before the five-year statute of limitations expired; the other case was thrown out because a receipt for a €20 fee, due when a complaint is filed, could not be found in the court file. And then, as if this was not scandalous enough, the court later met Logothetis’ request: that his computer, which the police had previously confiscated and which still contained Georgiou’s stolen emails, should be handed back to him.

International support for Georgiou – but that does not save him from the persecutions

There have been many instances of international support for Andreas Georgiou over the years. Below are some examples of recent ones.

The European Commission has repeatedly mentioned Georgiou’s case in its periodic reports of the post-program reviews for Greece. In its November 2019 Enhanced Surveillance Report it noted: The Commission has continued to monitor developments in relation to the legal proceedings against … the former President and senior staff of the Hellenic Statistical Authority. The case against the former Hellenic Statistical Authority President A. Georgiou related to charges filed in connection with fiscal statistics has been irrevocably dismissed. An appeal introduced by Mr. Georgiou in a civil defamation lawsuit is scheduled to be heard in January 2020.”

The International Statistical Institute noted in a statement published in December 2019: “It is of great concern to us that the legal harassment of Mr Georgiou is not yet over. There are three legal cases against him in Greece which are still open. He took these actions in accordance with statistical principles in his capacity as head of the national statistics office… Defending official statistics, as required by the UN Fundamental Principles of Statistics and the European Statistics Code of Practice, should not lead to any legal proceedings and even less to damages being awarded and public apologies. Now is the time for a fresh start in Greek statistics, and the ending of the victimisation of Mr Georgiou.”

The Board of the American Statistical Association also issued a statement in December 2019 stating inter alia that the Association was “troubled by Greece’s continued persecution of its former head statistician. Now in the ninth year, there are still open investigations and trials of Georgiou, a government professional who is loyal to his country. Greece’s new government provides an opportunity to remedy the unjust official treatment of Georgiou. Ending the prosecutions, accusations and legal proceedings and exonerating Georgiou would signal Greece’s commitment to accurate and ethical official statistics. This, in turn, could help foster foreign investment and overall confidence among Greece’s international partners, which helps Greece’s economy.”

Political witch hunt

In August 2017, Nikos Konstandaras columnist at Kathimerini and the New York Times warned that the Georgiou affair was “a witch hunt, not a thirst for justice.” Konstandaras concluded:

Beyond the injustice and the terrible personal cost for a fellow citizen, beyond the damage to the country’s credibility, the most tragic aspect of the affair is that people who know how dangerous this all is are investing in fantasies and encouraging fanaticism.

History, though, will record the role they played. In the end they will be loaded with more blame than that which they are trying to saddle onto others.

Now, more than two and a half years after this was written, the persecution of a civil servant who did what he was supposed to do, is still ongoing. Much to the shame of Greece the man who led ELSTAT from August 2010 to August 2015, putting in procedures for correct reporting of statistics following the exposure of fraudulent statistics for over a decade, is being prosecuted. At the same time, the people who for years provided false and fraudulent statistics to Greece, European authorities and the world, enjoy total impunity and even participate and benefit from Georgiou’s prosecutions.

In an article in the Washington Post as recently as 2 January this year, Georgiou’s case was brought up, pointing out how both professional rivals and politicians had decided to scapegoat Georgiou during the contagious time he was in office, creating the narrative that “he had “inflated” the deficit to “trap” Greece into accepting bigger international bailouts, with harsher conditions, than it needed.”

As pointed out, “the Greek government has changed hands multiple times” since the legal cases against Georgiou started, a particularly damning point for Mitsotakis and his government. “So far, though, those in power have continued to foment or tolerate the scapegoating of civil servants, and refused to help Georgiou clear his name.”

A worrying disincentive to service truthful information

The numerous prosecutions are utterly damning for the Greek political system. Equally, that the IMF and EU have not been able to adequately and decisively assist the quest for truthful statistics. It is a travesty of the rule of law that a civil servant has for more than eight years been persecuted for doing his job truthfully, to the professional standards expected of his office. A travesty that is harmful for not only for Greek civil servants and their work but elsewhere. Or, as concluded in the Washington Post article 2 January:

“And make no mistake: Georgiou may be the primary victim of this weaponization of the judicial system, but he is hardly its only target. Other civil servants — in Greece and in other countries weighing their commitment to rule of law — are watching and learning what happens when a number cruncher decides to tell the truth.”

In December 2016, Georgiou said to Icelog: “The numerous prosecutions and investigations against me and others that have been going on for years – as well as the persistence of political attacks and the absence of support by consecutive governments – have created disincentives for official statisticians in Greece to produce credible statistics. As a result, we cannot rule out the prospect that the problem with Greece’s European statistics will re-emerge. The damage already caused concerns not only official statistics in Greece, but more widely in the EU and around the world, and will take time and effort to reverse.”

How can Greece, the political class in Greece, face the fact that an innocent man is persecuted, and the real fraud of national statistics has never been investigated?

*Icelog has followed the Georgiou case since I visited Greece in 2015. See here for earlier blogs on the case.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Media reactions to Georgiou’s conviction – Kathimerini: it’s a “witch hunt”

There has been a general outcry in international media after the recent sentencing of former ELSTAT president Andreas Georgiou following six years of persecution by Greek authorities. With the exception of Kathimerini, the Greek press has however mostly been silent. As pointed out in the foreign media the “witch hunt” bodes ill for Greece and now, ELSTAT is indeed struggling with the national statistics… again.

The reporting on the recent conviction of former ELSTAT president Andreas Georgiou in Greece and abroad is decidedly different: abroad there is condemnation and genuine worry, in Greece there is little of that though with noticeable exception: Kathimerini did not hesitate to speak of “witch hunt.” The Financial Times’s headline was a “legal farce calls Greek reform into question.”

The Georgiou case exposes a rift in Greek society

In a short and concise comment by the newspaper’s editor, Nikos Konstandaras, sets out how “the very name Andreas Georgiou – has come to symbolize a rift in society.” On one side there are those who worry about the future of Greece, “knowing that only rational measures will help Greece get back on its feet; on the other, a heterogeneous crowd of indignant citizens and cynical politicians, united by their passionate desire to abdicate responsibility for the past and the present, demands that reality bend to their will.

I am afraid that the second group has more passion, a longer history and the momentum that the first one does not: It is, of course, much easier to rouse the crowd with promises to avoid pain than to embrace it. And loading all the responsibilities for the country’s problems on one man, the former head of Greece’s statistical service, is most seductive: Those who are truly to blame get to play judge, while others believe that because one person is guilty for the crisis and for austerity, the rest don’t have to pay anything… History, though, will record the role they played. In the end they will be loaded with more blame than that which they are trying to saddle onto others.”

The political figure behind the ELSTAT persecution: Karamanlis

Even before the verdict at the end of July, Kathimerini was clear about the direction of the ELSTAT trial – Kostas Karamanlis is the driving force as shown on a cartoon where Karamanlis, playing a video game, is hell-bent on not letting Andreas Georgiou get away. Same could be seen in a recent article in Parapolitika: Karamanlis is still furious with Georgiou and could not hide his satisfaction when Georgiou was sentenced.

As mentioned by Kathimerini when it brought the news of the conviction, this was “the second time that the country’s top prosecutor overturned an earlier ruling in favor of Georgiou, in a case that has become a touchstone for relations between Greece and its creditors.”

The worrying thing is that the Karamanlis faction is still fighting the battles of 2010, still pretending that the fraudulent statistics, indeed exposed before Georgiou took office, are somehow part of evil foreigners kicking Greece.

Worries among international partners and professionals

The various international media and organisations are rightly worried about the relentless persecution of Georgiou: it is a clear sign of political unwillingness to face the facts of political governance in Greece.

For good reasons, the European Commission has been following the case with trepidation but so far it has been utterly unsuccessful in preventing the ELSTAT staff persecutions. Spokeswoman for the Commission’s financial issues Annika Breidthardt said after the conviction that it was not in line with previous acquittal for the same charges:

“The independence of statistical offices in our member states is a key pillar the proper functioning of the Economic and Monetary Union (EMU), this is why it is protected by EU law. We take note of the specific ruling which we note that is not in line with the previous ruling in the previous procedure. We understand that today’s ruling is open for appealing on legal grounds before the Greek Supreme Court. “We have full confidence in the reliability and accuracy of ELSTAT data during 2010-2015 and beyond” … We underlined the importance of the independence of ELSTAT as a key commitment under the terms of the Memorandum of Understanding of the Program,” said Breidthardt.

As the International Statistical Institute, ISI has pointed out, Georgiou acted in complete compliance with Eurostat practice, European Statistics Code of Practice: “Not only is the verdict unfair to Mr Georgiou, it also has negative implications for the integrity of Greek and European official statistics. Accordingly, the ISI calls on the Greek Government and the EU Commission, in consultation with their respective statistical authorities, to take all necessary measures to challenge this verdict and seek its reversal as a matter of the utmost priority.”

The absurdity of it all

As pointed out the The Greek Reporter there is the absurdity of the whole process: “Just to let the absurdity sink in: Greece falsified its official statistics for years & the only person prosecuted is the one who fixed them.”

Bloomberg commentator Leonid Bershidsky pointed out that the legal troubles of Georgiou “are about conflicting political visions of the country.”

In a personal and insightful article on Politico, the economist Megan Greene who has followed the Greek crisis from early on, raises the question of the integrity of Greece’s institutions.

New doubts regarding ELSTAT figures

There is now, again a looming suspicion hanging over ELSTAT. As FT reported recently, some discrepancy has surfaced regarding Greek national statistics, this time related to the country’s GDP figures leading the paper to connect this to the ELSTAT case: “The announcement came amid renewed scrutiny of Elstat following an outcry over the conviction by an Athens court last week of Andreas Georgiou, who headed the agency between 2010 and 2015 for “violating his duties.” Mr Georgiou faces a series of trials for allegedly inflating Greece’s budget deficit figure in 2009, the year the country plunged into financial crisis, even though all the statistics produced during his tenure were accepted without reservation by Eurostat, the EU’s statistical service.”

These are only few voices from a large choir of worrying voices. So far, Andreas Georgiou has been prosecuted for the last six years. As long as this is going on, the political forces around Kostas Karamalis clinging on to the past and obstructing a healthy revival of the Greek economy, have the upper hand. That is profoundly worrying for the Europen Union, the IMF and other international partners working with Greece for, hopefully, a better and more sound future for the country.

Greece needs an independent report on its crisis – as was done in Iceland

Incidentally, in Iceland after the October 2008 banking collapse there were also political voices claiming the collapse was all the work of foreigners somehow wanting to get control of Iceland, its natural resources etc. What finally and effectively silenced these voices was the very thorough report published in April 2010 by the Special Investigation Commission.

This independent commission did a brilliant work of clarifying all the relevant aspects of the collapse, from political apathy to the abusive control the largest shareholders had on the three largest banks. The report was an important step for Iceland in working itself out of the crisis but time has made it no less important: it is there as a reference in order to keep in mind what really happened so the time and selective memory cannot alter the facts. – Surely the kind of work sorely needed in Greece (and in all other crisis-hit countries).

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

How is this possible, Greece?

The Greek ELSTAT saga has taken yet another turn, which should be a cause for grave concern in any European country: a unanimous acquittal by three judges of the Greek Appeals Court in the case of former head of ELSTAT Andreas Georgiou has been annulled. This was announced Sunday December 18 – the case was up in court December 6 – but no documents have been published so far, another worrying aspect.

The acquittal was the fourth attempt to acquit Gergiou – and this is now the fourth attempt to thwart the course of Greek justice and revive the unfounded charges against him. The intriguing thing to note here is that the acquittal was annulled by a prosecutor at the First Instance Court, who in September brought a whole new case regarding the debt and deficit statistics from 2010 and ELSTAT staff role here, this time not only accusing ELSTAT staff of wrongdoing but also staff from Eurostat and the IMF; a case still versing in the Greek justice system.

All of this rotates around the fact that ELSTAT, and now Eurostat and IMF staff, is being prosecuted for producing correct statistics after more than a decade of fraudulent reporting by Greek authorities.

It beggars belief that the justice system in Greece seems to be wholly under the power of political forces who try as best they can to avoid owning up to earlier misdeeds. In spite of acquittals, those who corrected the fraudulent statistics are being prosecuted relentlessly while nothing is done to explain what went on during the time of the fraudulent reporting. It should also be noted that in order to stop the ELSTAT prosecutions completely, four other cases related to this one, need to be stopped.

The ELSTAT staff is here reliving the horrors of the Lernaen Hydra in Greek mythology. Georgiou and his colleagues have had international support but that doesn’t deter Greek authorities from something that certainly looks like a total abuse of justice. How is it possible to time and again take up a case where those charged have already been acquitted?

Icelog has followed the ELSTAT saga, see here for earlier blogs, explaining the facts of this sad saga.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Greek authorities punish the messenger, not the culprits of fraud

In Greece, authorities go after those who tried to sort out the mess of the Greek economy, not those who created it. That’s one conclusion to be drawn for charges, yet again, brought against Andreas Georgiou former head of ELSTAT, the Greek statistics bureau. It should be scary for Greeks and European institutions to see the relentless persecutions of a civil servant who did his job.

Since he was appointed head of ELSTAT in summer of 2010, well after it was clear that the Greek statistics were unreliable, Andreas Georgiou has had to fight forces in Greece who simply refuse to let go of him and his colleagues, a story carefully recounted on Icelog a year ago, with the precise data of statistics and the development of the ELSTAT saga. Time and again, the case against Georgiou has been dropped but always brought up again.

New criminal charges now against Georgiou do not only threaten him with a prison sentence but also threaten to awaken earlier dropped charges against him and two of his colleagues.

And those who for years falsified statistics? No, not one hair on their head has been ruffled, no investigations set up as to how it was possible that wrong and falsified statistics were reported to Greeks themselves and to international bodies such as Eurostat, the European statistical bureau, more or less from 2000 until 2009.

In Game Over, the Inside Story of the Greek Crisis, George Papaconstantinou minister of finance during the fateful time from the October 2009 election until June 2011 recounts thoroughly how the falsified statistics came up as soon as the PASOK government came to power.

Already during his first days in Office, Papaconstantinou heard from various institutions that inter alia the much watched budget deficit was well beyond what the Greek authorities had reported to Eurostat two days before the October 2009 election. “In short, they had lied,” Papaconstantinou concludes in his book. What ensued was a discovery of fraudulent statistics going back years.

No one could precisely show Papaconstantinou how the reported figure was found. One of his first acts in office was to call the head of the national statistics, professor Emmanouil Kontopyrakis to his office. The professor had no idea how the deficit figure was computed but to him it did seem like a “reasonable projection” – the minister asked him to resign.

As Papaconstantinou carefully recounts much of the mistrust of his European colleagues directed at Greece was based on the fact that there wasn’t even precise statistics and figures to work with to begin with.

When Andreas Georgiou took over as head of ELSTAT in August the much-debated deficit figures, both forecasted and the real figures, had been corrected, of course greatly increasing the deficit, under the auspice of Eurostat.

As carefully detailed in my ELSTAT saga last year, the numbers kept going upwards. The 2009 deficit first forecasted 3.7% in early October was by April 2010 estimated by Eurostat to be an actual deficit of 13.6% but Eurostat was still not sure it couldn’t rise; by late 2010 Georgiou and his team found it to be 15.4%.

In his book, Papaconstantinou writes that Georgiou proved to be the right man for the job, “helping to make Greek statistics credible. I was less lucky with of the other people appointed to the ELSTAT board.” In a police investigation one board member was later discovered to have hacked Georgiou’s email account. Another member accused Georgiou of inflating the deficit figure, causing the bailout, a “totally absurd” accusation according to Papaconstantinou.

The memorandum on the Greek rescue packet was finalised May 2 2010. Yet, Georgiou, who only took over in August 2010, is continuously persecuted for having influenced the bailout.

Considering how poisonous the unreliable data proved to be in the discussions up to the May 2010 memorandum it would have been greater reason to thank Georgiou and his team for delivering sound statistical data.

But that is not what happened and things didn’t stop there. The opposition lapped up the accusations. “Soon the justice system was involved. Prosecutors brought criminal charges against Georgiou for actions having caused billions of damage to Greece. We were suddenly in a parallel universe; rather than bringing to task those who had lied about the true size of the deficit, we were accused for having told the truth!”

No matter though Georgiou’s case has been thrown out several times the dark forces in Greek politics always find a way of bringing it back. And that has now happened again, the case is being brought back in a new guise (see here and here). It seems that Europe risks having a political prisoner within its boundaries, imprisoned for doing his job.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Iceland’s recovery: myths and reality (or sound basics, decent policies, luck and no miracle)

Icelandic authorities ignored warnings before October 2008 on the expanded banking system threatening financial stability but the shock of 90% of the financial system collapsing focused minds. Disciplined by an International Monetary Fund program, Iceland applied classic crisis measures such as write-down of debt and capital controls. But in times of shock economic measures are not enough: Special Prosecutor and a Special Investigative Committee helped to counteract widespread distrust. Perhaps most importantly, Iceland enjoys sound public institutions and entered the crisis with stellar public finances. Pure luck, i.e. low oil prices and a flow of spending-happy tourists, helped. Iceland is a small economy and all in all lessons for bigger countries may be limited except that even in a small economy recovery does not depend on a one-trick wonder.

“The medium-term prospects for the Icelandic economy remain enviable,” the International Monetary Fund, IMF, wrote in its 2007 Article IV Consultation

Concluding Statement, though pointing out there were however things to worry about: the banking system with its foreign operations looked ominous, having grown from one gross domestic product, GDP, in 2003 to ten fold the GDP by 2008. In early October 2008 the enviable medium-term prospect were clouded by an unenviable banking collapse.

All through 2008, as thunderclouds gathered on the horizon, the Central Bank of Iceland, CBI, and the coalition government of social democrats led by the Independence party (conservative) staunchly and with arrogance ignored foreign advice and warnings. Yet, when finally forced to act on October 6 2008, Icelandic authorities did so sensibly by passing an Emergency Act (Act no. 125/2008; see here an overview of legislation related to the restructuring of the banks and here more broadly on economic measures).

Iceland entered an IMF program in November 2008, aimed at restoring confidence and stabilising the economy, in addition to a loan of $2.1bn. In total, assistance from the IMF and several countries amounted to ca. $10bn, roughly the GDP of Iceland that year.

In spite of mostly sensible measures political turmoil and demonstrations forced the “collapse government” from power: it was replaced on February 1 2009 by a left coalition of the Left Green party, led by the social democrats, which won the elections in spring that year. In spite of relentless criticism at the time, both governments progressed in dragging Iceland out of the banking mess.

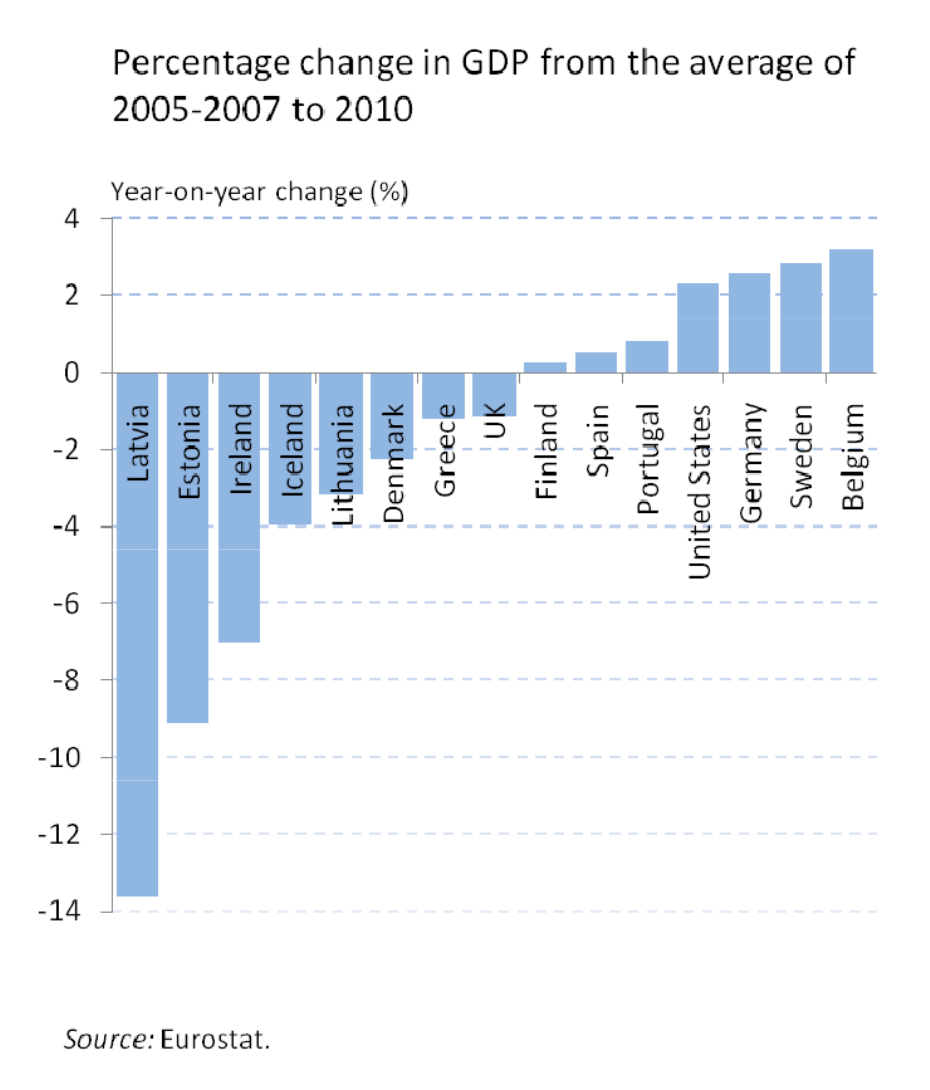

After the GDP contracted by 4% in the first three years the Icelandic economy was already back to growth summer 2011 and is now in its fifth year of economic growth. In 2015, Iceland became the first European country, hit by crisis in 2008-2010, to surpass its pre-crisis peak of economic output.

Iceland is now doing well in economic terms and yet the soul is lagging behind. Trust in the established political parties has collapsed: instead, the Pirate party, which has never been in government, enjoys over 30% following in opinion polls.

Compared to Ireland and Greece, Iceland’s recovery has been speedy, giving rise to questions as to why so quick and could this apparent Icelandic success story be applied elsewhere. Interestingly, much of the focus of that debate is very narrow and in reality not aimed at clarifying the Icelandic recovery but at proving or disproving aspects of austerity, the euro or both.

Unfortunately, much of this debate is misleading because it is based on three persistent myths of the Icelandic recovery: that Iceland avoided austerity, did not save its banks and that the country defaulted. All three statements are wrong: Iceland has not avoided austerity, it did save some banks though not the three largest ones and did not default.

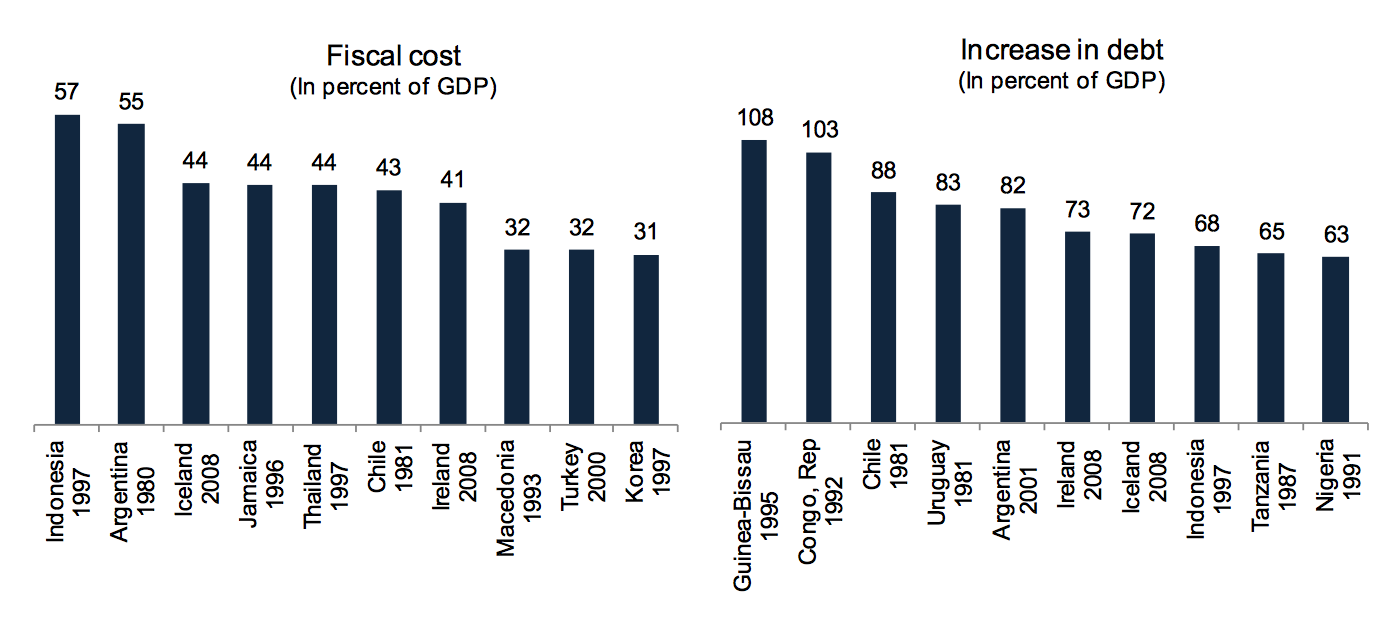

Indeed, the high cost of the Icelandic collapse is often ignored, amounting to 20-25% of GDP. Yet, not as high as feared to begin with: the IMF estimated it could be as much as 40%. The net fiscal cost of supporting and restructuring the banks is, according to the IMF 19.2% of GDP.

Costliest banking crisis since 1970; Luc Laeven and Fabián Valencia.

As to lessons to avoid the kind of shock Iceland suffered nothing can be learnt without a thorough investigation as to what happened, which is why I believe the report, a lesson in itself, by the Special Investigative Commission, SIC, in 2010 was fundamental. Tackling eventual crime, as by setting up the Office of the Special Prosecutor, is important to restore trust. Recovering from a collapse of this magnitude is not only about economic measures and there certainly is no one-trick fix.

On specific issues of the economy it is doubtful that Iceland, a micro economy, can be a lesson to other countries but in general, the lessons are simple: sound public finances and sound public institutions are always essential but especially so in times of crisis.

In general: small economies fall and bounce fast(er than big ones)

The path of the Icelandic economy over the past fifty years has been a path up mountains and down deep valleys. Admittedly, the banking collapse was a major shock, entirely man-made in a country used to swings according to whims of fishing stocks, the last one being in the last years of the 1990s.

(Statistics, Iceland)

Sound public finances, sound institutions

What matters most in a crisis country? Cleary a myriad of things but in hindsight, if a country is heading for a major crisis make sure the public finances are in a sound state and public authorities and institutions staffed with competent people, working for the general good of society and not special interests – admittedly not a trivial thing.

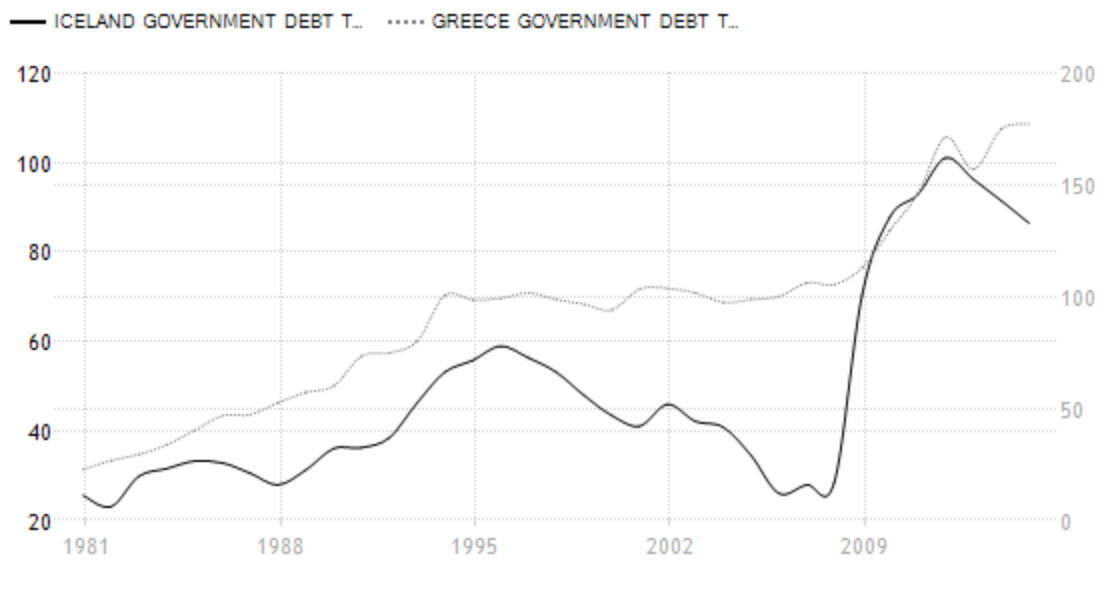

Since 1980 Icelandic sovereign debt to GDP was on average 48.67%, topped at almost 60% around the crisis in late 1990s and had been going down after that. Compare with Greece.

Trading Economics

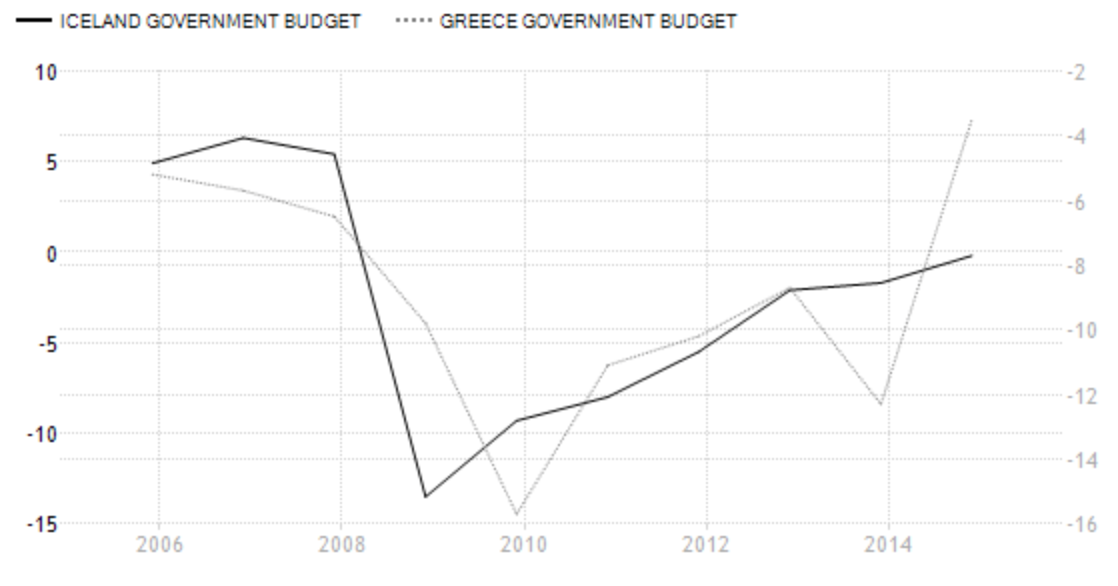

Same with the public budget: there was a surplus of 5-6% in the years up to 2008, against an average of -1.15% of GDP from 1998 to 2014. With a shocking deficit of 13.5% in 2009 it has since steadily improved, pointing to a balanced budget this year and a tiny surplus forecasted for next year. Again, compare with Greece.

Trading Economics

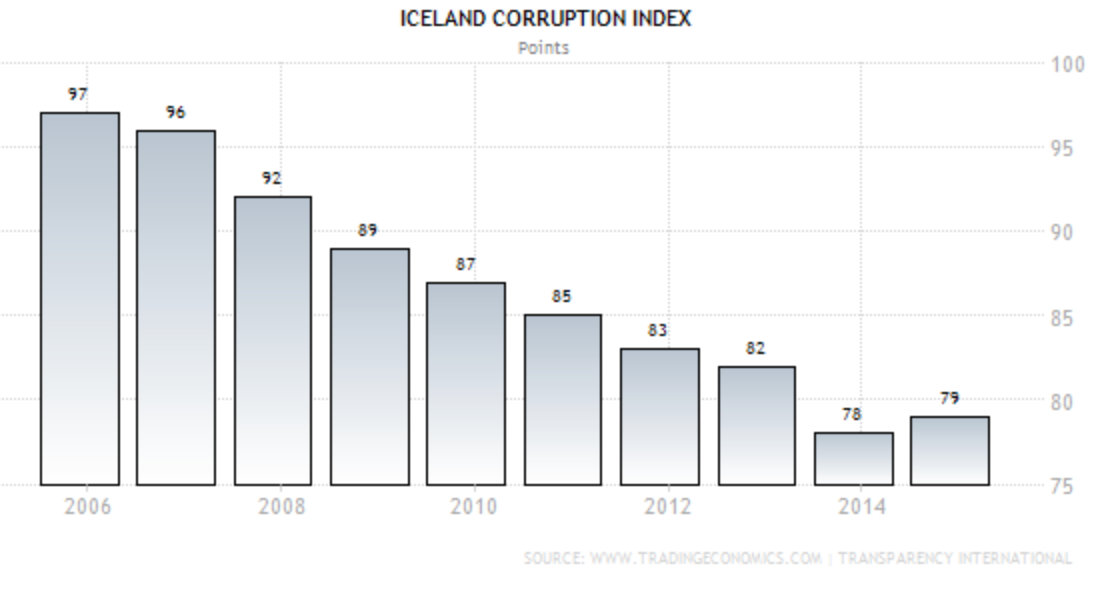

As to institutions, the CBI has been crucial in prodding the necessary recovery policies; much more so after change of board of governors in early 2009. Sound institutions and low corruption is the opposite of Greece, where national statistics were faulty for more than a decade (see my Elstat saga here).

Events in 2008

In early 2007, with sound state finances and fiscal strength the situation in Iceland seemed good. The banks felt invincible after narrowly surviving the mini crisis on 2006 following scrutiny from banks and rating agencies (the most famous paper at the time was by Danske Bank’s Lars Christensen).

Icelanders were keen on convincing the world that everything was fine. The Icelandic Chamber of Commerce hired Frederic Mishkin, then professor at Columbia, and Icelandic economist Tryggvi Þór Herbertsson to write a report, Financial Stability in Iceland, published in May 2006. Although not oblivious to certain risks, such as a weak financial regulator, they were beating the drum for the soundness of the Icelandic economy.

But like in fairy tales there was one major weakness in the economy: a banking system with assets, which by 2008 amounted to ten times the country’s GDP. Among economists it is common knowledge that rapidly growing financial sector leads to deterioration in lending. In Iceland, this was blissfully ignored (and in hindsight, not only in Iceland: Royal Bank of Scotland is an example).

Instead, the banking system was perceived to be the glory of Icelandic policies in a country that had only ever known wealth from the sea. Finance was the new oceans in which to cast nets and there seemed to be plenty to catch.

In early 2008 things had however taken a worrying turn: the value of the króna was declining rapidly, posing problems for highly indebted households – 15% of their loans were in foreign currency, i.a. practically all car loans. The country as a whole is dependent on imports and with prices going up, inflation rose, which hit borrowers; consumer-price indexed, CPI, loans (due to chronic inflation for decades) are the most common loans.

Iceland had been flush with foreign currency, mainly from three sources: the Icelandic banks sought funding on international markets; they offered high interest rates accounts abroad – most of these funds came to Iceland or flowed through the banks there (often en route to Luxembourg) – and then there was a hefty carry trade as high interest rates in Iceland attracted short- and long-term investors.

“How safe are your savings?” Channel 4 (very informative to watch) asked when its economic editor Faisal Islam visited Iceland in early March 2008. CBI governor Davíð Oddsson informed him the banks were sound and the state debtless. Helping the banks would not be “too much for the state to swallow (and here Oddsson hesitated) if it wanted to swallow it.” – Yet, timidly the UK Financial Services Authority, FSA, warned savers to pay attention not only to the interest rates but where the deposits were insured the point being that Landsbanki’s Icesave accounts, a UK branch of the Icelandic bank, were insured under the Icelandic insurance scheme.

The 2010 SIC report recounts in detail how Icelandic authorities ignored or refused advise all through 2008, refused to admit the threat of a teetering banking system, blamed it all on hedge funds and soldiered on with no plan.

The first crisis measure: Emergency Act Oct. 6 2008

Facing a collapsing banking system did focus the minds of politicians and key public servants who over the weekend of October 4 to 5 finally realised that the banks were beyond salvation. The Emergency Act, passed on October 6 2008 laid the foundation for splitting up the banks. Not into classic good and bad bank but into domestic and foreign operations, well adapted to alleviating the risk for Iceland due to the foreign operations of the over-extended banks.

The three old banks – Kaupthing, Glitnir and Landsbanki – kept their old names as estates whereas the new banks eventually got new names, first with the adjective “Nýi,” “new,” later respectively called Arion bank, Íslandsbanki and Landsbankinn. Following the split, creditors of the three banks own 87% of Arion and 95% of Íslandsbanki, with the state owning the remaining share. Due to Icesave Landsbanki was a different case, where the state first owned 81.33%, now 97.9%.

In addition to laying the foundation for the new banks, one paragraph of the Emergency Act showed a fundamental foresight:

In dividing the estate of a bankrupt financial undertaking, claims for deposits, pursuant to the Act on on (sic) Deposit Guarantees and an Investor Compensation Scheme, shall have priority as provided for in Article 112, Paragraph 1 of the Act on Bankruptcy etc.

By making deposits a priority claim in the collapsed banks interests of depositors were better secured than had been previously (and normally is elsewhere).

When 90% of a financial system is swept away keeping payment systems functioning is a major challenge. As one participant in these operations later told me the systems were down for no more than ca. five or ten minutes during these fateful days. All main institutions, except of course the three banks, withstood the severe test of unprecedented turmoil, no mean feat.

The coming months and years saw the continuation of these first crisis measures.

It is frequently stated that Iceland, the sovereign, was bankrupted by the collapse or defaulted on its debt. That is not correct though sovereign debt jumped from ca. 30% of GDP in 2008 until it peaked at 101% in 2012.

IMF and international assistance of $10bn

That fateful first weekend of October 2008 it so happened that there were people from the IMF visiting Iceland and they followed the course of events. Already then seeking IMF assistance was discussed but strong political forces, mainly around CBI governor Davíð Oddsson, former prime minister and leader of the Independence party, were vehemently against.

One of the more surreal events of these days was when governor Oddsson announced early morning on October 7 that Russia would lend Iceland €4bn, with maturity of three to four years, the terms 30 to 50 basis points over Libor. According to the CBI statement “Prime Minister Putin has confirmed this decision.” – It has never been clarified who offered the loan or if Oddsson had turned to the Russians but as the Cypriot and Greek government were to find out later this loan was never granted. If Oddsson had hoped that a Russian loan would help Iceland avoid an IMF program that wish did not come true.

On November 17, 2008 the Prime Minister’s Office published an outline of an Icelandic IMF program: Iceland was “facing a banking crisis of extraordinary proportions. The economy is heading for a deep recession, a sharp rise in the fiscal deficit, and a dramatic surge in public sector debt – by about 80%.”

The program’s three main objectives were: 1) restoring confidence in the króna, i.a. by using capital controls; 2) “putting public finances on a sustainable path”; 3) “rebuilding the banking system… and implementing private debt restructuring, while limiting the absorption of banking crisis costs by the public sector.”

An alarming government deficit of 13.5% was now forecasted for 2009 with public debt projected to rise from 29% to 109% of GDP. “The intention is to reduce the structural primary deficit by 2–3 percent annually over the medium-term, with the aim of achieving a small structural primary surplus by 2011 and a structural primary surplus of 3½-4 percent of GDP by 2012.” – This was never going to be austerity-free.

By November 20 2008 IMF funds had been secured, in total $2.1bn with $827m immediately available and the remaining sum paid in instalments of $155m, subject to reviews. The program was scheduled for two years and the loan would be repaid 2012 to 2015.

Earlier in November Iceland had secured loans of $3bn from the other Nordic countries together with Russia and Poland (acknowledging the large Polish community in Iceland). Even the tiny Faroe Islands chipped in with $50m. In addition, governments in the UK, the Netherlands and Germany reimbursed depositors in Icelandic banks, in all ca. $5bn. Thus, Iceland got financial assistance of around $10bn, at the time equivalent of one GDP, to see it through the worst.

In spite of a lingering suspicion against the IMF, both on the political left and right, there was never the defiance à la greque. Both the “collapse coalition” and then the left government swallowed the bitter pill of an IMF program and tried to make the best of it. Many officials have mentioned to me that the discipline of being in a program helped to prioritise and structure the necessary measures.

Recently, an Icelandic civil servant who worked closely with the IMF staff, told me that this relationship had been beneficial on many levels, i.a. had the approach of the IMF staff to problem solving been an inspiration. Here was a country willing to learn.

Part of the answer to why Iceland did so well is that the two governments more or less followed the course set out in he IMF program. This turned into a success saga for Iceland and the IMF. One major reason for success was Iceland’s ownership of the program: politicians and leading civil servants made great effort to reach the goals set in the program. – An aside to the IMF: if you want a successful program find a country like Iceland to carry it out.

Capital controls: a classic but much maligned measure

For those at work on crisis measures at the CBI and the various ministries there was little breathing space these autumn weeks in 2008. No sooner was the Emergency Act in place and the job of establishing the new banks over (in reality it took over a year to finalise) when a new challenge appeared: the rapidly increasing outflow of foreign funds threatened to sink the króna below sea level and empty the foreign currency reserves of the CBI.