Search Results

Deutsche Bank and its (alleged) failure to recognise up to $12bn losses

It’s not a new story – as Deutsche Bank points out in its response – but it’s a story coming up again with more vigor and new evidence. According to the FT: “Deutsche Bank failed to recognise up to $12bn of paper losses during the financial crisis, helping the bank avoid a government bail-out, three former bank employees have alleged in complaints to US regulators.” – FT Alphaville calls it “papering over the cracks … (allegedly)”

Three Deutsche employees have resigned from the bank, after having raised concerns in 2010 and 2011 with the SEC in the US. One has settled handsomely, has been paid $900,000 to settle a case of unfair dismal, apparently after being in touch with the SEC.

It’s worth keeping in mind that Deutche is the highest leveraged bank in Europe and the US: at the end of last year total assets exceeded Tier 1 capital by 44 times – but that’s still down from 68 times in 2007, when the subprime crisis broke. The average leverage in German banks was 32 times last year and in Europe 26 times.

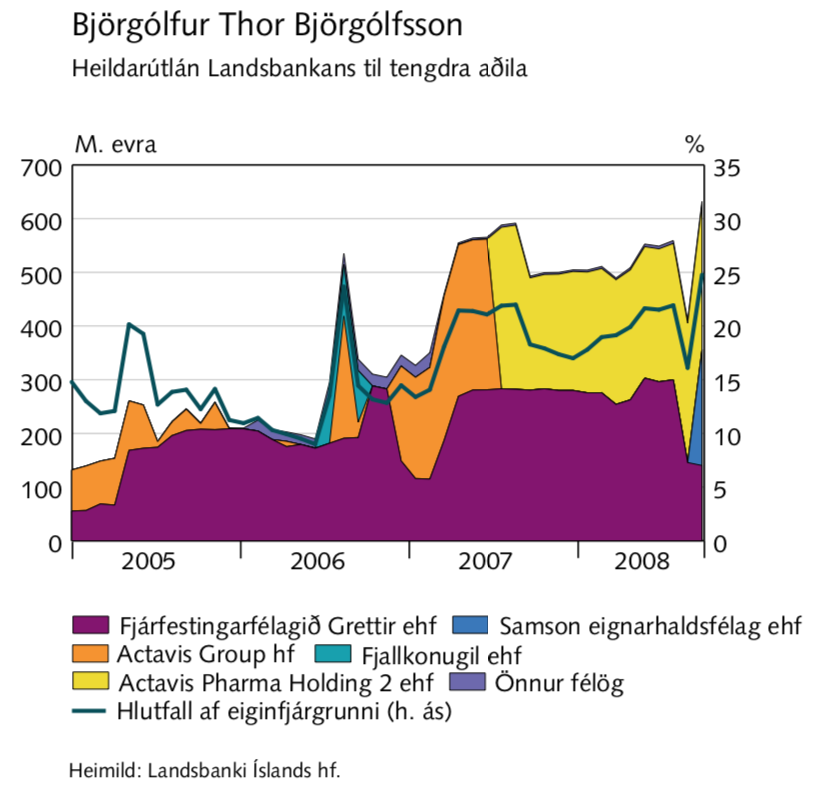

Watching Deutsche from Iceland, it hardly comes as a surprise that some papering was done at and following crisis crunch time in 2008. Deutsche had issued big loans to Icelandic banks and companies. In the case of the pharmaceutical group Actavis, taken off market in 2007 by Bjorgolfur Thor Bjorgolfsson the loan was huge and for some time the biggest loan on Deutsche’s books. Admittedly a loan saga, which belongs to a different age, the year 2007, as pointed out by Breaking View:

Actavis’s 2007 buyout, by Icelandic tycoon Thor Bjorgolfsson, belongs to a different age. Bjorgolfsson was then reckoned among the world’s richest people and the Actavis deal was worth $6.4 billion including debt – five times the value of Iceland’s biggest listed company today. Deutsche employed bubble-era tactics too. The loans totalled a reported 4 billion euros, including 1 billion of “payment-in-kind” notes. These are particularly risky, since instead of paying interest in cash the PIK-note debt burden expands.

This loan backfired for Deutsche – it couldn’t sell the loan on. As Breaking View points out, the loan stayed with Deutsche until it could finally sell Actavis earlier this year.

Deutsche was also a lender into some interesting Kaupthing schemes, where Deutsche advised Kaupthing to lend companies to invest in Kaupthing’s CDS, in order to lower the CDS and consequently the bank’s borrowing cost (it seems to have had some effect). According to Kaupthing documents Deutsche was also a lender, with Kaupthing, when the bank lent money to a Qatari investor to buy shares in Kaupthing. The Office of the Special Prosecutor in Iceland has brought charges against four Icelanders, as earlier reported on Icelog.* Deutsche is not implied in this case.

Deutsche’s lending to Iceland shows quite a bit of recklessness though we can’t see how reckless they were, i.e. in terms of the loan covenants, if they were lending to holding companies (like the Icelandic banks did) and not into companies with operations and more tangible assets. The feeling is that Deutsche in case of some of the Icelandic loans, i.a. the Actavis loans, Deutsche was too late in sensing changed sentiments in the market and couldn’t sell them off. If that was widely happening within the bank Deutsche had some serious issues – and then the speculations now, of the bank having covered its losses, might possibly make sense.

*The persons indicted are ex-chairman of the Kaupthing board Sigurdur Einarsson, Kaupthing’s CEO Hreidar Mar Sigurdsson, Kaupthing Luxembourg manager Magnus Gudmundson and Kaupthing’s second largest shareholder Olafur Olafsson. The District Court has now thrown one of the charges out, related to Magnus Gudmundsson but the OSP will most likely appeal the decision.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

The Kaupthing investigation: outlines of an extensive and calculated fraud

Although the Office of the Special Prosecutor had asked for the court rulings on the custodial sentences of two ex-Kaupthing managers not to be published the charges have been seeping into the Icelandic media through the day. The most extensive leak throws light on the charges against Magnus Gudmundsson ex-manager of Kaupthing Luxembourg and manager of Banque Havilland until his arrest last week. Most likely, it’s the defense team of those arrested who are responsible for the leaks that are clearly against the interest of the OSP.

The OSP is investigating five separate issues of what they call ‘extensive, calculated and unparalleled fraud.’ Gudmundsson appears to be at the centre but it’s highly likely that these issues involve at least Hreidar Mar Sigurdsson Kaupthing’s ex-CEO as well as Sigurdur Einarsson ex-executive chairman.

1 Gudmundsson is being investigated for involvement in dealings with the sole purpose of increasing the bank’s share value. This market manipulation is thought to have been going on from June 2005 until the demise of Kaupthing in October 2008.

It’s known that the Icelandic Financial Authorities, FME, has been investigating what is thought to be an extensive market manipulation in all the banks, not only Kaupthing.

The report of the Althingi Investigative Committee, published on April 12, also throws light on this issue. According to the report the bank bought 29% of the bank’s shares, issued on June 30 2008. The bank’s own trade in its shares amount to 60-75% of all trade on the Icelandic Stock Exchange from June to October 2008.

The OSP seems to suspect that managers and certain key employees responsible for the bank’s proprietary trading carried out these trades in a calculated way in order to influence the share price. It then became a major problem for the bank what to do with all the shares it bought. Gudmundsson seems to have played a key role in ‘parking’ the shares.

This throws light on the extensive loans that Kaupthing issued to key employees and many of its major shareholders and clients with the bank’s shares as collateral. It was almost a rule that the bank’s clients bought shares in addition to what other business they had with the bank, i.e. extra money was thrown into the loans for the purpose of buying Kaupthing shares. A foreign employer of the bank recently explained to me that he had been very surprised when he realized, some years ago, how the bank mildly insisted that any big client/borrower also bought shares in the bank – shares that the client wouldn’t need to pay for but that the bank financed with loans.

2 Issues related to alleged market manipulation and breach of fiduciary duty on behalf of Gudmundsson in relation to several companies. One of them is Holt Investment Ltd, a company related to Skuli Thorvaldsson, an Icelandic businessman living in Luxembourg and a major client of Kaupthing but otherwise not very visible. Thorvaldsson was the biggest borrower in Kaupthing Luxembourg. Another company is Desulo Trading Ltd, registered in Cyprus in October 2007. Desulo’s manager is an Icelandic businessman, Egill Agustsson. From mid 2008 until the collapse of Kaupthing Desulo Trading Ltd borrowed ISK13,4bn to buy shares in Kaupthing. Companies related to Kevin Stanford seem to be part of these suspicious trades. Loan agreements and other documents related to Kaupthing’s dealings with these companies are found to be in breach of the bank’s own rules, made without proper documentation and with insufficient collaterals. It’s alleged that it was clear to the managers that these loans were contrary to the interests of the bank as a listed company.

Most likely, the dealings with these companies are only the tip of the iceberg – it’s clear that this extensive ‘parking’ explains many otherwise inexplicable loans to key employees and trusted clients. The OSP mentions deals going back to 2005 – I’ve heard that signs of market manipulation can be traced as far back as to 2004.

3 It’s clear from earlier reports that Kaupthing, advised by Deutsche Bank, tried to influence its CDS spreads. The investigation focuses on two companies, Chesterfield United Inc. and Partridge Management Group, that Kaupthing fed a loan of €260m through four other companies, Trenvis Ltd., Holly Beach S.A., Charbon Capital Ltd and Harlow Equities S.A. in order to trade in the bank’s CDS and influence the spread. The companies were connected to the bank’s major shareholders/clients Olafur Olafsson and Skuli Thorvaldsson. Loans from Deutsche Bank formed a part of this package. When DB made margin calls Kaupthing lent money to these companies to meet the calls. Kaupthing did in the end lose €510m on these transactions and DB refuses any responsibility.

During its last hours, on Oct. 6 2008, Kaupthing got a loan from the Icelandic Central Bank of €500m. Though Kaupthing already seems to have been doomed there was still a belief among Icelandic regulators that Kaupthing might survive though Landsbanki and Glitnir would fail. It now seems that some of this loan was used to lend these companies used to give entirely wrong information about the bank’s standing. – The investigation aims at clarifying who was responsible and whether it was i.a. a question of a breach of fiduciary duty.

4 Two companies, Marple Holdings S.A., owned by Skuli Thorvaldsson and Lindsor Holdings Corporation, owned by Kaupthing’s key employees, bought Kaupthing bonds, issued in 2008 when Kaupthing, as many other banks, ran into financing difficulties. The aim seems to have been to remove any risk of a falling bond price from the beneficial owners of these companies to the bank itself. Documents related to these companies seem to have been falsified so as to indicate that the deals had been done earlier than was the case.

5 In September 2008 Kaupthing announced that the Qatari investor Sheik Sheikh Mohammed Bin Khalifa Al-Thani was buying 5% of the bank. The OSP is investigating if a Kaupthing loan to companies related to the Sheikh and Olafur Olafsson were intended finance the deal so that the Sheikh was actually not putting any money into the deal, done only to make the bank look stronger than it was. (Olafsson owns a food company, Alfesca, that had announced in summer of 2008 that the Sheikh was buying shares in the company. That deal was never finalized but it’s unclear if Kaupthing was also here the lender of a loan that was never going to be repaid.)

In short: the issues investigated relate to deals between Kaupthing and major shareholders/big clients that favoured the key employees and affiliated clients but dumped any losses onto the bank. The investigation focuses on breach of fiduciary duty, counterfeiting and market manipulation and involves billions of kronur.

Kaupthing operated in Luxembourg for eight years and in London since 2005. It operated in all the Scandinavian countries and in the US. In the UK the FSA was warned: the board of Singer & Friedlander, the bank that Kaupthing bought in 2005, repeatedly made it clear to the FSA that it didn’t think the mangers of Kaupthing were ‘fit and proper’ – and yet, nothing was done and in none of these countries the regulators saw anything questionable. Yet, the meteoric growth of the band and ‘incestuous’ relationships with major shareholders should have been an indication, as well as persistent rumours. The good thing is that Serious Fraud Office is now conducting its own investigation of Kaupthing.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

The financial cliffhangers: some fall others fly

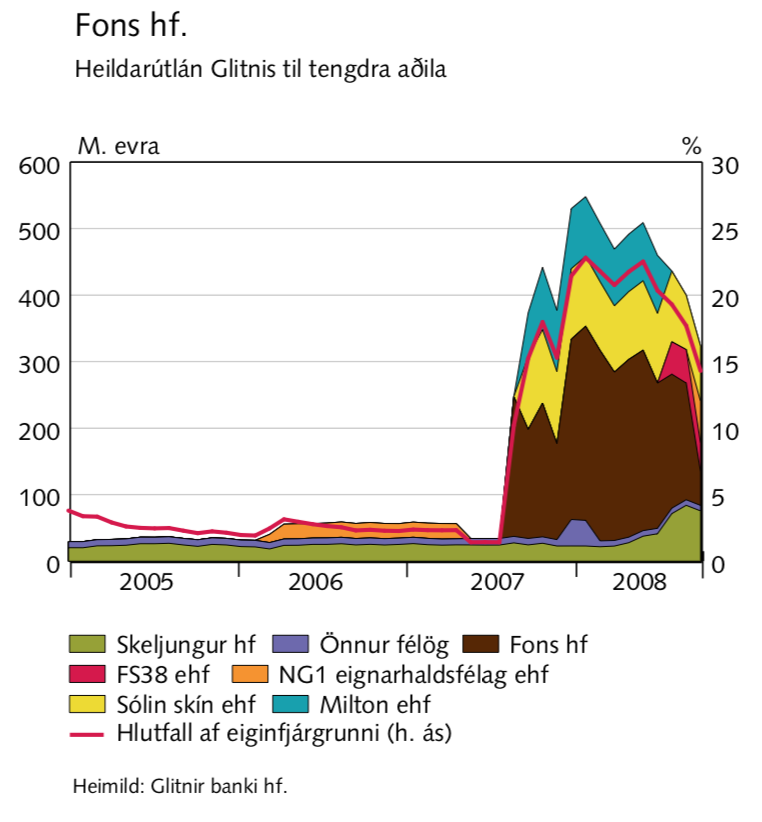

The pre-fall banking system in Iceland had some intriguing characteristics. One of the more astounding one is how willingly all the three major banks lent a small group of businessmen, tied to the banks through ownership and inter-dealings, beyond all rhyme and reason. This completely reversed the power balance between the banks and their main clients – the clients, not the banks, set the rules of the game. In their game the clients were favoured at the expense and to a great risk for the banks.

Last summer I read a fascinating and scary book, ‘Mafia Pulita’, ‘The Clean Mafia’, by Antonio Laudati (now a prosecutor in Bari where the Mafia is particularly ingrained and vicious) and Elio Veltri, both well known for their fight against organised crime. Through stories of a few Mafiosi they explain how the Mafia infiltrates the ‘clean’ economy (as opposed to the ‘dirty’ or ‘black’ economy of organised crime) – this is the Mafia that buys what it can and only kills when it has to. I interviewed Laudati on a hot August Sunday morning in Naples where we shared the Napolitan pastry ‘sfogliata’ as he told me about corrupt Italian banks that seemed uncannily similar to the Icelandic banks.

In former times, the Mafia would find a bank clerk, often a low level one, to help channel its ill begotten money into the licit economy. Now instead, there have been cases, mostly in small banks in the North of Italy, where the criminals collude with the managers. The criminals get loans that systematically are far above the exposure anyone else gets, putting the bank itself at great risk. These banks also assist the criminals to borrow money from other banks by guaranteeing their loans though the collaterals, mostly shares and property, often financed by loans from the ‘helping’ banks. This effective loan machine generates money for the criminals, their loans are never paid back but serviced with more loans.

I’m not suggesting a Mafia connection or anything Mafia-related regarding the Icelandic banks; not at all. I just find it intriguing that the only banks with business patterns similar to the Icelandic ones turn out to be corrupt Italian banks that have been closed down by the authorities. As in the Italian banks the Icelandic banks loaned money to few chosen individuals beyond all sensible limits. These clients weren’t much bothered with margin calls nor the collaterals sold when loan covenants were breeched; old loans were serviced with new ones and it does indeed seem likely that in some cases the banks did not expect the loans to be repaid.

Icelanders are now following with anger and resentment how the new banks –Islandsbanki and Arion Bank owned by credit holders respectively in Kaupthing and Glitnir respectively, Landsbanki by the Icelandic state – are refinancing companies owned by some of the major before-the-fall players. Here are the latest examples:

There isn’t much left of Baugur, Jon Asgeir Johannesson’s retail empire spanning UK high streets and other places. Both Baugur Iceland and Baugur UK collapsed under its debt. Administrators have contested various last-minute dealings. Landsbanki was evidently the biggest lender but the two other banks were fairly generous too. The most valuable Icelandic assets are now in Hagar, a holding company that runs a myriad of shops in Iceland, most importantly two supermarket chains, Bonus and Hagkaup (interestingly, Hagkaup was founded by the father of Jon Asgeir’s wife – first Jon Asgeir bought Hagkaup, later he married into the Hagkaup family, though long after its founder’s day). Arion Bank had taken over Hagar, apparently against a debt of ISK70bn (£350m).

After continuous headlines of Hagar’s fate – last summer Johannesson i.a. wowed to bring in foreign investors in 2-3 years time – Arion Bank has now decided to float Hagar later this year. Johannes, Jon Asgeir’s father (who in 1989 founded Bonus with his son, the first step towards the Baugur empire), is the chairman of Hagar. Arion will grant him the right to buy 10% of the company, in addition to the management getting 5% – in Iceland, the takeover trigger is 30%. Before the fall the bank would no doubt have lent preferred buyers against Hagar shares but Arion claims that’s not on offer now. Many Icelanders would have liked to see Hagar broken up so as to correct the ca 60% market share that Hagar has in the food market. Arion maintain that it’s obliged to focus on its profit not correcting competition.

Olafur Olafsson’s foreign profile has been much lower than Jon Asgeir’s though he has been living abroad for years, recently swapping Knightsbridge for Lausanne. Olafsson, who spans the gamut of the pre- and post-privatisation period, rose on the tail of the Progressive Party and the co-operative movement and built his empire on the shipping company Samskip. He later became one of the biggest shareholders in Kaupthing and was the main shareholder of Alfesca that sprung from one of the two main fishing companies, operating since after the war. It seems to have been through Olafsson’s networking that the Quatari businessman al-Thani invested in both Kaupthing (Sept. 2008) and Alfesca (summer 2008). The Alfesca investment never materialised; the Kaupthing one is being investigated as an alleged market manipulation. Olafsson and Samskip’s management have now negotiated a financial reorganisation with Arion and Fortis Bank – it is understood that the owners will bring in new capital.

Icelandic Group is the other major Icelandic fishing company that in 2005 was bought by Magnus Thorsteinsson and Björgolfur Gudmundsson. These two, together with Gudmundsson’s son Bjorgolfur Thor Bjorgolfsson, bought 40% as Landsbanki was privatised in 2002. At the time it was understood that the money came from the sale of the Bravo Brewery in St Petersburg to Heineken for $400m (their St Petersburg enterprise gave rise to myriads of stories about Iceland’s ‘Russian connections’ and ‘Russian money’ culminating when Russian authorities seemed to contemplate bailing Iceland out in Oct. 2008 – one of the many untold stories of the fall). It’s now clear that if there was any profit from the Bravo sale it only partly, if at all, financed the Landsbanki deal – the three simply got a loan from Bunadarbanki just like those who bought Bunadarbanki (later merging with Kaupthing), Olafsson being one of them, got a loan from Landsbanki.

Thorsteinsson and Gudmundsson are both bankrupt in Iceland. As most companies touched by the two (and all the other ‘viking’ investors) Icelandic sank under its debt in October 2008 when Landsbanki’s new CEO, put in place just after the bank’s demise, revived it. Icelandic’s present management has been running the company since 2007. In spite of losses since 2005, Landsbanki, now on its second CEO since the fall, still keeps the company afloat, claiming that the company will be able to clear out its debt in due course. Since Icelandic hasn’t published an annual report since 2007 it’s difficult to judge its position.

The latest stories of Hagar, Samskip and Icelandic – all important companies within the major Icelandic business conglomerates during the boom – show that certain relations seem to reach if not beyond the grave then at least beyond bankruptcies. Those who had the greatest hold on the old banks are still flying but some of these financial cliffhangers might still crash as the administrators edge in. In Iceland, the feeling is that it’s happening only very slowly – people find it difficult to understand that billions in debt in companies fallen by the road side do not affect the general standing of those whose financial acrobatics brought down the banks and the krona. Returning to former times when the political parties meted out favours through the banks is not an option – and yet there is a great pressure on the Government to do whatever it takes to prevent what is seen as cementing the unfairness in the unhealthy banking system before the fall.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Kaupthing Luxembourg and Banque Havilland – risk, fraud and favoured clients

Banque Havilland has just celebrated its tenth anniversary: it is now ten years since David Rowland bought Kaupthing Luxembourg out of bankruptcy. A failed bank not only tainted by bankruptcy but severely compromised by stark warnings from the regulator, CSSF. Yet, neither the regulator nor the administrators nor later the new owner saw any reason but to keep the Kaupthing Luxembourg manager and key staff. In four criminal cases in Iceland involving Kaupthing the dirty deals were done in the bank’s Luxembourg subsidiary with back-dated documents. Two still-ongoing court cases, which Havilland is pursuing with fervour in Luxembourg, indicate threads between Kaupthing Luxembourg and Havilland, all under the nose of the CSSF.

“The journey started with a clear mission to restructure an existing bank and the ambition of the new shareholder to lay strong foundations, which an international private bank could be built on,” wrote Juho Hiltunen CEO of Banque Havilland on the occasion of Havilland’s 10th anniversary in June this year.

This cryptic description of the origin of Banque Havilland hides the fact that the ‘existing bank’ David Rowland bought was the subsidiary of Kaupthing Luxembourg, granted suspension of payment 9 October 2008, the same day that the mother-company, Kaupthing hf, defaulted in Iceland.

The last year of Kaupthing Luxembourg’s operations had been troubled by serious concerns at the Luxembourg regulator, Commission de Surveillance du Secteur Financier, CSSF, regarding the bank’s risk management and the management’s willingness to move risk from clients onto the bank.

Unperturbed by all of this, Rowland not only bought the bank but kept the key employees, including the bank’s Icelandic director, Magnús Guðmundsson, instrumental in selling Kaupthing Luxembourg to Rowland. Guðmundsson stayed in his job until 2010, when news broke in Iceland he was under investigation, later charged and found guilty in two criminal cases (two are still ongoing) in Iceland, where he has served several prison sentences. He was replaced by Jean-Francois Willems, another Kaupthing Luxembourg manager, CEO of Banque Havilland Group since 2017. Willems was followed by Peter Lang, also an earlier Kaupthing manager. Lang left that position when Banque Havilland was fined by the CSSF for breaches in money laundering procedures.

David Rowland’s reputation in his country of origin, Britain, was far from pristine – in Parliament, he has been called a ‘shady financier.’ However, all that seemed forgotten in 2010 when the media-shy tycoon was set to become treasurer of the Conservative Party, having donated in total £2.8m to the party in less than a year. As the British media revised on Rowland stories, Rowland realised he was too busy to take on the job and stepped out of the spotlight again.

In the Duchy of Luxembourg, Rowland was seen as fit and proper to own a bank. And the bank, CSSF had severely criticised, was seen as fit and proper to receive a state aid in the form of a loan of €320m in order to give the bank a second life.

Criminal investigations in Iceland showed that Kaupthing hf’s dirty deals were consistently carried out in Luxembourg. There were clearly plenty of skeletons in the Kaupthing Luxembourg that Rowland bought. Two still-ongoing legal cases connect Kaupthing and Havilland in an intriguing way.

In December 2018, the CSSF announced that Banque Havilland had been fined €4m and now had “restrictions on part of the international network” for lack of compliance regarding money laundering and terrorist financing, the regulator’s second heftiest fine of this sort. Eight days later the bank announced a new and stronger management team: a new CEO, Lars Rejding from HSBC. It was also said that there were five new members on the independent board but their names were not mentioned. An example of the bank’s rather sparse information policy.

KAUPTHING LUXEMBOURG: RISK, FRAUD AND FAVOURED CLIENTS

2007: CSSF spots serious lack of attention to risk in Kaupthing Luxembourg

On August 25 2008, the CSSF wrote to the Kaupthing Luxembourg management, following up on earlier exchanges. The letter shows that as early as in the summer of 2007, the CSSF was aware of the serious lack of attention to risk. The regulator’s next step, in late April 2008, was to ask for the bank’s credit report, based on the Q1 results, from the bank’s external auditor, KPMG. In the August 2008 letter, the CSSF identified six key issues where Kaupthing Luxembourg was at fault:

1 The CSSF deemed it unacceptable that Kaupthing Luxembourg financed the buying of Kaupthing shares “as this may represent an artificial creation of capital at group level.”

2 Analysing the bank’s loan portfolio, the CSSF concluded that the bank’s activity was more akin to investment banking than private banking as the bulk of credits were “indeed covered by highly concentrated portfolios (for example: (Robert) Tchenguiz, (Kevin) Stanford, (Jón Ásgeir) Johannesson, Grettir (holding company owned by Björgólfur Guðmundsson, Landsbanki’s largest shareholder, together whith his son, Björgólfur Thor Björgólfsson) etc.)” The CSSF saw this “as highly risky and we ask you to reduce it.” This could only continue in exceptional cases where the loans would have a clear maturity (as opposed to bullet loans that were rolled on).

3 Private banking loans should have diversified portfolio of quoted securities and be easy to liquidate, based on a formal written procedure as to how that should be done.

4 Personal guarantees from the parent company should be documented in the loan files so that the external auditor and the CSSF could verify how these exposures were collateralised in the parent bank.

5 As the CSSF had already pointed out in July 2007, the indirect concentration risk should not exceed 25% of the bank’s own funds. CSSF concluded that the bank was not complying with that requirement as the indirect risk concentration on Eimskipafélagið hf, owned by Björgólfur Guðmundsson, and on Kaupthing hf, the parent bank, was above this limit.

6 At last, CSSF stated that only quoted securities could be easily liquidated, meaning that securities illiquid in a stress scenario, could not be placed as collateral. CSSF emphasised that securities like Kaupthing hf, Exista hf and Bakkavor Group hf, could not be used as a collateral, exactly the securities that some of Kaupthing’s largest clients were most likely to place as collaterals.

It is worth keeping in mind that the regulator had been studying figures from Q1 2008; in August, when CSSF sent its letter, the Q2 figures were already available: the numbers had changed much for the worse. Unfazed, Kaupthing Luxembourg managers insisted in their answer 18 September 2008 that the regulator was wrong about essential things and they were doing their best to meet the CSSF concerns.

What the CSSF identified: the pattern of “favoured clients”

The CSSF had been crystal clear: after closely analysing the Kaupthing Luxembourg operation it did not like what it saw. Kaupthing’s way of banking, lending clients funds to buy the bank’s shares and absolving certain clients of risk and moving it onto the bank, was not to the CSSF’s liking. What the CSSF had indeed identified was a systematic pattern, explained in detail in the 2010 Icelandic SIC report.

This was the pattern of Kaupthing’s “favoured clients”: Kaupthing defined a certain group of wealthy and risk-willing clients particularly important for the bank. In addition to loans for the client’s own projects, there was an offer of extra loans to invest in Kaupthing shares, with nothing but the shares as collateral. In some cases, Kaupthing set up companies for the client for this purpose, or the bank would use companies, owned by the client, with little or no other assets. The loans were issued against Kaupthing shares, placed in the client’s company.

How this system would have evolved is impossible to say but over the few years this ran, these shareholding companies profited from Kaupthing’s handsome dividend. The loans were normally bullet loans, rolled on, where the client’s benefit was just to collect the dividend at no cost. In some cases, the dividend was partly used to pay off the loan but that was far from being the rule.

What the bank management gained from this “share parking,” was knowing where these shares were, i.e. that they would not be sold or shorted without the management’s knowledge. Kaupthing had to a large extent, directly and indirectly funded the shareholdings of the two largest shareholders, Exista and Ólafur Ólafsson. In addition to these large shareholders there were all the minor ones, funded by Kaupthing. It can be said that the Kaupthing management had de facto complete control over Kaupthing.

All the three largest Icelandic banks practiced the purchase of own shares against loans to a certain degree but only Kaupthing had sat this up as part of its loan offer to wealthy clients. In addition, Kaupthing had funded share purchase for many of its employees.* This activity effectively turned into a gigantic market manipulation machine in 2008, again especially in Kaupthing, as the share price fell but would no doubt have fallen steeper and more rapidly if Kaupthing had not orchestrated this share buying on an almost industrial scale.

The other main characteristic of Kaupthing’s service for the favoured clients was giving them loans with little or no collaterals. This also led to concentrated risk, as pointed out in para 2 and 3 in the CSSF’s letter from August 2008 and later in the SIC report. As one source said to Icelog, for the favoured clients, Kaupthing was like a money-printing machine.

Back-dated documents in Kaupthing

After the Icelandic Kaupthing failed, the Kaupthing Resolution Committee, ResCom, quickly discovered it had a particular problem to deal with. The ResCom had kept some key staff from the failed bank, thinking it would help to have people with intimate knowledge working on the resolution.

A December 23 2008 memorandum from the law firm Weil Gotschal & Manges, hired by the ResCom, pointed out an ensuing problem: lending to companies owned by Robert Tchenguiz, who for a while sat on the board of Exista, Kaupthing’s largest shareholder, had been highly irregular, according to the law firm. As the ResCom would later find out, this irregularity was by no means only related to Tchenguiz but part of the lending to favoured clients.

The law firm pointed out that some employees had been close to these clients or to their closest associates in the bank and advised that all electronic data and hard drives from Sigurður Einarsson, Hreiðar Már Sigurðsson and seven other key employees should be particularly taken care of. Also, it noted that two of those employees, working for the ResCom, should be sacked; it could not be deemed safe that they had access to the failed bank’s documents. The ResCom followed the advice but by then these employees had already had complete access to all material for almost three months.

Criminal cases against Kaupthing managers have exposed examples of back-dated documents, done after the bank failed. According to one such document, Hreiðar Már Sigurðsson was supposed to have signed a document in Reykjavík when he was indeed abroad (from the embezzlement case against HMS). There is also an example of September 2008 minutes of a Kaupthing board meeting being changed after the collapse of Kaupthing. No one has been charged specifically with falsifying documents, but these two examples are not the only examples of evident falsification.

The central role of Kaupthing Luxembourg in Kaupthing hf’s dirty deals

The fully documented stories behind the many dirty deals in Kaupthing first surfaced in April 2010 in the report by the Special Investigative Commission, SIC. Intriguingly, these deals were, almost without exception, executed in Luxembourg.

By the time the SIC published its report, the Icelandic regulator, FME, already had a fairly clear picture of what had been going on in the banks. The fraudulent activities in Kaupthing made that bank unique – and most of these activities involved fraudulent loans to the favoured clients. In January 2010, the Icelandic regulator, FME, sent a letter to the CSSF with the header “Dealings involving Kaupthing banki hf, Kaupthing Bank Luxembourg S.A., Marple Holding S.A., and Lindsor Holdings Corporation.”

Through the dealings of these two companies, Skúli Þorvaldsson profited over the last months before the bank’s collapse by around ISK8bn, at the time over €50m. These trades mainly related to Kaupthing bond trades: bonds were bought at a discount but then sold, even on the same day, at a higher price or a par. Þorvaldsson profited handsomely through these trades, which effectively tunnelled funds from Kaupthing Iceland to Þorvaldsson, via Kaupthing Luxembourg.

Þorvaldsson was already living in Luxembourg when Kaupthing set up its Luxembourg operations in the late 1990s. He quickly bonded with Magnús Guðmundsson; Icelog sources have compared their relationship to that of father and son. When the bank collapse, Þorvaldsson was Kaupthing Luxembourg’s largest individual borrower and, in September 2008, the bank’s eight largest shareholder, owning 3% of Kaupthing hf through one of his companies, Holt Investment Group. At the end of September 2008, Kaupthing’s exposure to Þorvaldsson amounted to €790m. The CSSF would have been fully familiar with the fact that Þorvaldsson’s entire shareholding was funded by Kaupthing loans.

In addition, the FME pointed out that four key Kaupthing Luxembourg employees, inter alia working on those trades, had traded in bonds, financed by Kaupthing loans, profiting personally by hundreds of thousands of euros. Intriguingly, these employees had not previously traded in Kaupthing bonds for their own account. Some of these trades took place days before Kaupthing defaulted, with the FME pointing out that in some cases the deals were back-dated.

The central role of Kaupthing Luxembourg in Kaupthing’s Icelandic criminal cases

Following the first investigations in Iceland, the Office of the Special Prosecutor, OSP, in Iceland, now the County Prosecutor, has in total brought charges in five cases against Kaupthing managers, who have been found guilty in multiple cases: the so-called al Thani case, and the Marple Holding case, connected to Skúli Þorvaldsson, who was charged in that case but found not guilty.

The third is the CLN case, the fourth case is the largest market manipulation ever brought in Iceland. The charges in the fifth case concern pure and simple embezzlement where Hreiðar Már Sigurðsson, at the time the CEO of Kaupthing Group, is charged with orchestrating Kaupthing loans to himself in summer of 2008 in order to sell Kaupthing shares so as to create fraudulent profit for himself. Three of the cases are still ongoing. The two cases, which have ended, the al Thani case and the market manipulation case resulted in heavy sentencing of Sigurðsson, Magnús Guðmundsson and Sigurður Einarsson, as well as other employees.

The first case brought was the al Thani case where Sigurðsson, Guðmundsson, Einarsson and Ólafsson were charged were misleading the market – they had all proclaimed that Sheikh Mohammed Bin Khalifa al Thani had bought shares in the bank without mentioning that the shares were bought with a loan from Kaupthing. The lending issued by the Kaupthing managers was ruled to be breach of fiduciary duty. The hidden deals in this saga were done in Kaupthing Luxembourg. Equally in the Marple case and the CLN case: the dirty deals, at the core of these cases, were done in Kaupthing Luxembourg.

Hreiðar Már Sigurðsson has been charged in all five cases; Magnús Guðmundsson in four cases and chairman of the board at the time Sigurður Einarsson in two cases. In addition, the bank’s second largest shareholder and one of Kaupthing’s largest borrowers Ólafur Ólafsson was charged and sentenced in the al Thani case.

What the CSSF has been investigating: Lindsor and the untold story of 6 October 2008

One of the few untold stories of the Icelandic banking collapse relates to Kaupthing. On 6 October 2008, the Icelandic Central Bank, CBI, issued a €500m loan to Kaupthing after the CBI governor Davíð Oddsson called the then PM Geir Haarde to get his blessing. This loan was not documented in the normal way: it is unclear where this figure of €500m came from, what its purpose was or how it was then used. As Oddsson nonchalantly confirmed on television the following day, the loan was announced by accident on the day it was issued. The loan was issued on the day the government passed the Emergency Act, in order to take over the banks and manage their default.

On the day that Kaupthing received the CBI loan, Kaupthing issued a loan of €171m to a BVI company, Lindsor Holdings Corporation, incorporated in July 2008 by Kaupthing, owned by Otris, a company owned by some of Kaupthing’s key managers. The largest transfer from Kaupthing October 6 was €225m in relation to Kaupthing Edge deposit holders, who were rapidly withdrawing funds. The second largest transfer was the Lindsor loan.

Having obtained the loan of €171m, Lindsor purchased bonds from Kaupthing entities and from Skúli Þorvaldsson, again via Marple, which seems to have profited by €67.5m from this loan alone. In its January 2010 letter to the CSSF, FME stated it “believes that the purpose of Lindsor was to create a “rubbish bin” that was used to dispose of all of the Kaupthing bonds still on the books of Kaupthing Luxembourg as the mother company, Kaupthing Iceland, was going bankrupt… Lindsor appears to FME to be a way to both reimburse favoured Kaupthing bondholders (Marple and Kaupthing Luxembourg employees) as well as remove losses from the balance sheet of Kaupthing Luxembourg. These losses were transferred to Lindsor, and entity wholly owned by Kaupthing Iceland,” at the time just about to go into default.

In addition, FME pointed out that most of the documents related to these Lindsor transactions had not been signed until December 2008 “but forged to appear as though they had been signed in September 2008. Employees in both Kaupthing Luxembourg and Kaupthing Iceland appear to have been complicit in this forgery.” – Yet another forgery story.

Intriguingly, when the OSP in Iceland decided to investigate Marple Holding, it already had a long-standing relationship with authorities in Luxembourg, having inter alia conducted multiple house searches in Luxembourg, first in 2010, with assistance from the Luxembourg authorities.

The purpose of the FME letter in January 2010 was not only to inform but to encourage the CSSF to open investigations into these trades. It took the CSSF allegedly some years until it started to investigate Lindsor. According to the Icelandic daily Morgunblaðið, the Prosecutor Office in Luxembourg now has the fully investigated case on his desk – the only thing missing is a decision if the case will be prosecuted or not.

Judging from evidence available on Lindsor in Iceland, there certainly seems a strong case to prosecute but the question remains if the investigation wins over the extreme lethargy in the Duchy of Luxembourg in investigating financial institutions.

AND SO, BANQUE HAVILLAND ROSE FROM KAUPTHING LUXEMBOURG’S COMPROMISED BOOKS

Enter the administrators

It is clear, that already in the summer of 2008, before Kaupthing Luxembourg collapsed together with the Icelandic mother company, Luxembourg authorities were fully aware that not everything in the Kaupthing Luxembourg operations had been in accordance with legal requirements and best practice.

On 9 October 2008, Kaupthing hf was put into administration in Iceland. On that same day, Kaupthing Luxembourg was granted suspension of payment for six months with the CSSF appointing administrators: Emmanuelle Caruel-Henniaux from PricewaterhouseCoopers, PWC, and the lawyer Franz Fayot. After Banque Havilland later came into being, PWC became the bank’s auditor. Its auditing fees in 2010 amounted to €422,000. In 2017, the fees had jumped to €1.3m.

Fayot was to play a visible role in the second coming of Kaupthing Luxembourg and has, as PWC, continued to do legal work for Banque Havilland. From 1997 to 2015 Fayot worked for the law firm Elvinger Hoss Prussen, EHP, another name to note; in 2015 Fayot joined the Luxembourg lawyer, Laurent Fisch, setting up FischFayot.

Contrary to the measures taken in Kaupthing Iceland, there was allegedly no visible attempt by the Kaupthing Luxembourg administrators to comparable scrutiny: Magnús Guðmundsson stayed with the bank and worked alongside the administrators with other Kaupthing employees. Their aim seems to have been to make sure that the bank, bursting with skeletons, would be sold on to someone with a certain understanding of Kaupthing’s business model.

The Kaupthing sale could only have happened with the understanding and goodwill of Luxembourg authorities: in spite of knowing of the severe issues and faulty management, the regulator seems to have left the administrators and Kaupthing staff to its own devices. Crucially, the state of Luxembourg was instrumental in giving the bank a second life, as Banque Havilland, by guaranteeing it a state aid of €320m.

JC Flowers, the Libyans and Blackfish Capital

Consequently, right from the beginning, everything was in place to enhance Kaupthing Luxembourg’s appeal for restructuring; the only thing missing was a new owner. The Luxembourg government had already outlined a rescue plan, drawing in the Belgian government, as Kaupthing Luxembourg had operated a subsidiary in Belgium where it marketed its high-interest accounts, Kaupthing Edge.

In a flurry of sales activity, the administrators contacted 40 likely buyers but the call for tender was open for everyone. The investment fund JC Flowers, which earlier had been involved with Kaupthing hf, had briefly shown interest in buying the Luxembourg subsidiary. But already by late 2008, Kaupthing Luxembourg seemed to be firmly on the path of being sold to the Libyan Investment Authority, LIA, the Libyan sovereign wealth fund, at the time firmly under the rule of the country’s leader Muammar Gaddafi.

The LIA certainly had the means to purchase the Luxembourg bank. In the end, however, two things proved an unsurmountable obstacle. The creditors rejected the Libyan plan 16 March 2009, possibly taking the reputational risk into account. And perhaps most importantly, given that the Luxembourg state wanted to enable the purchase with considerable funds, the Luxembourg authorities did in the end balk at the deal with the Libyans but only after months of negotiations.

Blackfish Capital and Jonathan Rowland’s “lieutenant”

In 2008, Michael Wright, a solicitor turned businessman, was working for Jonathan Rowland, son of David Rowland. In an ensuing court case, Wright described his role as being Jonathan’s “lieutenant” in spotting investment opportunities.

By 2013, Wright had fallen out with the Rowlands, later suing father and son in London where he lost his case in 2017. According to the judgement, Wright maintained that he had played a leading role in securing the purchase of Kaupthing Luxembourg for the Rowlands: after being introduced to Sigurður Einarsson or “Siggi” as he called him, already in late 2008, Wright brought the opportunity to purchase Kaupthing Luxembourg to the Rowlands.

The Rowlands admitted that Wright had been involved in “some discussions” with Einarsson and Kaupthing Bank representatives in early 2009 relating to “a proposed transaction concerning bonds,” which did not materialise but that the contact leading to the Rowlands acquiring Kaupthing Luxembourg came “subsequently.” The judge on the case noted that all three men were unreliable witnesses.

As late as March 2009, a deal with the LIA to purchase Kaupthing Luxembourg still seemed on track. According to Kaupthing hf Creditors’ report, updated in March 2009, the government of Luxembourg and a consortium led by the LIA had signed a memorandum of understanding with the aim of enabling Kaupthing Luxembourg to continue its operations. In order to facilitate the restoration, the governments of Luxembourg and Belgium had agreed to lend the bank €600m, enabling the bank to repay its 22,000 retail depositors.

From other sources, Icelog understands that the Rowlands were only contacted after it was clear that neither JC Flowers nor LIA would be buying Kaupthing Luxembourg. The person who contacted the Rowlands, according to Icelog sources, was indeed Magnús Guðmundsson, who had heard that father and son might be looking for a private bank to buy. By early June 2009, the Rowlands’ agreement with the administrators was in place.

Interestingly, there had apparently been some tentative interest from large Kaupthing shareholders – who nota bene had all bought Kaupthing shares with Kaupthing loans. The Guðmundsson brothers, Lýður and Ágúst, who owned Exista, Kaupthing’s largest shareholder, had allegedly been interested in joining David Rowland as minority shareholders but that did not happen. In an open letter to Hreiðar Már Sigurðsson and Magnús Guðmundsson, published in January 2019, Kevin Stanford, once close to the Kaupthing managers, claimed the two bankers did explore the possibility of buying Kaupthing together with the Guðmundsson brothers but the plan was abandoned.

Whatever the reality of these tentative plans, they show that the Kaupthing managers and the largest shareholders focused on keeping Kaupthing Luxembourg alive, caring less for other parts of the bank. That is intriguing, given the role of the Luxembourg subsidiary in Kaupthing’s dirty deals.

The €320m Luxembourg state aid for restructuring

From contemplating a loan of €600m, as the Kaupthing hf creditors had been led to believe, the final figure was a still generous €320m. Led by Luxembourg, with half of the funds provided by the Belgian government through an inter-state loan, the deal was finalised 10 June 2009. The sum of €320m was decided since €310m was deemed to cover the liquidity shortfall with €10m extra as a margin.

In December 2008, the Kaupthing Luxembourg shares had been moved to a new company, Luton Investments (now BH Holdings), set up by a BVI nominee company, Quebec Nominees Limited that Kaupthing Luxembourg had often used (and most likely owned).

Rowland took Luton Investments over in May 2009. On 10 July, Rowland increased its capital by the agreed amount of €50m, raising its capital to the agreed figure, according to the restructuring plan. Rowland also pledged to add further €25 to 75m in liquidity. The private banking activities and the deposits, at 13 March 2009 €275 to 325m, were taken over by Rowland’s Blackfish Capital, and registered as a new bank, Banque Havilland. Its starting balance was €1.3bn, €750 to 800m of which were existing commitments to the Luxembourg Central Bank, BCL.

Part of Rowland’s lot was also Kaupthing Luxembourg’s entire infrastructure, including headquarters and IT system. With Kaupthing’s staff of 100 employees, Banque Havilland had from the beginning funding, infrastructure and staff to ensure a smooth transition from the old Kaupthing Luxembourg to the new Banque Havilland.

On July 9 2009, the European Commission gave its approval of the state aid. It indicates that the Banque Havilland’s main source of income during its early years, was indeed the money coming from the Luxembourg state.

Pillar Securitisation

Banque Havilland’s €1.3bn starting balance was only around half of old Kaupthing Luxembourg’s balance sheet. The rest, €1.2bn, more or less the old bank’s lending operations, for which no buyer was found, was placed in a new company, Pillar Securitisation, in order to be sold over the coming years, to pay off the main creditors: the Luxembourg state, the Luxembourg deposit guarantee fund, AGDL, Luxembourg Deposit Guarantee Association (funded by retail banks), and Kaupthing Luxembourg’s inter-bank creditors.

Having received a banking licence, Banque Havilland came into being on July 10 2009: Luton Investments, the sole owner of Kaupthing Luxembourg, was split in two, Banque Havilland, the “living” bank and Pillar Securitisation, the “dead” bank. Crucially, Pillar was de facto not a separate unit: it had no staff but was run in-house by Banque Havilland, residing at the Banque Havilland address at 35A avenue J.F. Kennedy, formerly the premises of Kaupthing Luxembourg.

The proceeds of Pillar were vital for the recovery of creditors since asset sales of that company determine their recovery. The main creditors were the two governments that lent into the restructuring. The loan was divided into a super-senior tranche of €210m and a senior tranche of €110m, split in two to repay the two states, Luxembourg and Belgium. The same was for the AGDL, and the around €300m it covered as deposits were transferred: AGDL received bonds in return.

Having scrutinised the state loans to Kaupthing Luxembourg, the European Commission ruled that the loans amounted to state aid: after all, no commercial bank would have agreed to a non-interest loan to a bank during suspension of payment. These advantages were conferred to Blackfish Capital via the state-aided restructuring plan. However, the Commission was equally clear that this state aid was compatible with the Treaty, which does allow for a remedy caused by “serious disturbance in the economy of a Member State.”

Interestingly, the original plan was to wind Pillar down in just a few years; ten years later, that goal has still not been reached.

ROWLAND, THE BANK OWNER

What Rowland bought: CSSF’s concerns and Kaupthinking in practice

By buying a failed bank, Rowland showed he was not too bothered about reputational risk. By keeping the ex-manager of Kaupthing Luxembourg, Magnús Guðmundsson and his staff, he also showed that he was not worried about Kaupthing’s activities. True, much of that story was not public at the time. Rowland would however have heard of CSSF’s serious concern in summer of 2008, before the bank failed. Concern, related to risky loans to large shareholders and related parties, that would have leapt out of the books on due diligence.

Although the CSSF had been chasing Kaupthing for credit risk and over-exposure to large clients and shareholders, the regulator was apparently as unbothered as the administrators that the Kaupthing managers were in charge of the bank during its suspension of payment.

Not only did CSSF apparently not follow up on earlier worries but the Luxembourg state decided to facilitate the bank’s second life with loans, notably without making it a condition that the management should be changed.

In Banque Havilland’s 2010 annual accounts, COO Venetia Lean (Rowland’s daughter) and CFO Jean-Francois Willems stated in their introduction that the bank would focus on retaining clients who met “strategic requirements… Towards the end of the year the family started to introduce members of its network to the Bank and we are working on the development of co-investment products whereby clients have the opportunity to invest alongside the family.” This focus, on co-investing with the family, is no longer mentioned.

Rowland’s first foreign investments after Luxembourg: Belarus and Iceland

In November 2010, Banque Havilland embarked on its first foreign venture, in Belarus: ‘the first Belarusian foreign direct investment fund,’ apparently a short-lived joint-venture with the Russian Sberbank Group. The press release seems to have disappeared from the Havilland website.

From 2011 to 2015 Banque Havilland expanded both in Luxembourg and abroad, i.e. in Monaco, London, Moscow, Liechtenstein, Switzerland and Nassau, either by buying banks or opening offices. The expansion in Monaco, Liechtenstein and Switzerland were done inter alia by buying Banque Pasche in these three locations. In the London office it set up a partnership with 1858Ltd in order to add art consultancy to its services.

Rowland’s interest for Icelandic investments did not end with Kaupthing Luxembourg. Contrary to most other foreign investors at the time, Rowland did not seem unduly worried by capital controls in Iceland, in place since autumn 2008. In the spring of 2011, it transpired that he had bought just under 10% of shares in the Icelandic MP Bank, which he held through a family-owned company, Linley Limited, represented on the MP board by Michael Wright.

MP Bank was named after its founder Margeir Pétursson, a Grand Master in chess, who set it up in 1999. In 2005, Pétursson was interested in expanding abroad but rather than following Icelandic bankers to the neighbouring countries, he made use of his knowledge of Russian and bought Lviv Bank in Ukraine. MP Bank survived the banking collapse in 2008 but was struggling. By 2010, the bank was no longer under Pétursson’s control and he left the board. In early 2011 the bank was split in two, with Pétursson still running that part owning the bank’s foreign assets.

At the time Rowland bought shares in MP Bank the bank was being revived with new capital and new shareholders. Another new foreign shareholder, who bought a stake in MP, equal to Rowland’s, was the ex-Kaupthing client, Joe Lewis, who, with Kaupthing loan to buy shares in Kaupthing and scantily covered loans, fitted the characteristics of a favoured client.

Enic was a holding company Lewis co-owned with Daniel Levy through which they held their trophy asset, Tottenham Hotspur. Kaupthing Singer & Friedlander, KSF, Kaupthing’s UK subsidiary, had issued a loan of €121.9 million to Enic, with shares in the football club as collateral. Kaupthing deemed the club was worth €89m, which meant the loan was only party covered in addition to the collateral being highly illiquid. Yet, the rating of the collateral on Kaupthing books was ‘good’ as Kaupthing had “confidence in the informal support of the principals.” According to the loan book “Joe Lewis is reputedly extremely wealthy and a target for doing further business with.”

Kaupthing, Banque Havilland and Kvika

In 2009, the former KSF director Ármann Þorvaldsson published a book, Frozen Assets, about his Kaupthing life. In it, he tells, almost with palpable nostalgia, of sitting on Lewis’ yacht in June 2007, discussing further projects; Þorvaldsson was keen to build a stronger relationship with the man estimated to be one of the 20 richest people in the UK. What ties were being forged on the yacht is anyone’s guess.

Rowland was clearly as unworried about MP Bank’s reputation – at the time, involved in some court cases – as he had been about Kaupthing Luxembourg’s reputational risk. In 2014, MP Bank and Virðing, an Icelandic asset management company with numerous ex-Kaupthing employees, attempted to merge with MP Bank, giving rise to rumours in Iceland that a new Kaupthing was in the making. The merger floundered. In the summer of 2015, both Rowland and Lewis apparently sold their stakes to Straumur, another resurrected Icelandic investment bank. Yet, according to Linley Limited 2015 annual accounts, the MP Bank shares were written down that year and Rowland is no longer a shareholder in the bank.

After the Straumur purchase in 2015, MP Bank changed its name to Kvika. As Virðing and Kvika did indeed merge in 2017, the former director of KSF, Ármann Þorvaldsson became CEO of Kvika until he recently demoted himself by swapping places with Kvika’s deputy CEO Marínó Örn Tryggvason, another ex-Kaupthing employee, and moved to London in order to focus on Kvika London. The question is if Kaupthing’s former clients in London will be tempted to bank with Kvika. One of them has already stated to Icelog that he will not be switching to Kvika.

Out of the three largest Icelandic banks, that collapsed in October 2008, Kaupthing, or rather Kaupthing-related people, both managers and shareholders, seem to be the only ones who keep giving the idea that Kaupthing-connections are still alive and meaningful. These musings reverberate in the Icelandic media from time to time.

THE KAUPTHING SKELETONS IN BANQUE HAVILLAND

The Kaupthing – Banque Havilland link: Immo-Croissance

One link that connects old Kaupthing with Banque Havilland is the real estate company, Immo-Croissance, founded in 1988. By the time, Immo-Croissance attracted Icelandic attention, it owned two prime assets in Luxembourg, Villa Churchill and a building, set for demolition, on Boulevard Royal, where the land was the valuable asset. In 2008, Jón Ásgeir Jóhannesson, the Icelandic businessman of Baugur-fame and a long-time large borrower of Kaupthing and all other Icelandic banks, had set his eyes on Immo-Croissance.

Jóhannesson had hoovered up real estate companies here and there, most notably in Denmark, where he had been on a wild shopping spree, all merrily funded by the three Icelandic banks. Interestingly, he used Kaupthing Luxembourg for this transaction – Kaupthing put up a loan of €122m – although a consortium under Jóhannesson’s control had been the largest shareholder in Glitnir since spring 2007.

In November 2007, Immo-Croissance’s board reflected the Baugur ownership as Baugur-related directors took seat on the board, together with Kaupthing employee Jean-François Willems. Under Baugur-ownership, Immo-Croissance apparently went on a bit of a cruise through several Baugur-owned companies. In June 2008, a Baugur Group company, BG Real Estate Europe, merged with Immo-Croissance, whereby magically the €122m loan to buy Immo-Croissance landed on Immo-Croissance own books.

But as with so many purchases by the Kaupthing’s favoured clients, Baugur’s purchase depended entirely on Kaupthing’s funding. By the end of September 2008, Baugur was in dire straits and Immo-Croissance was sold, or somehow passed on to SK Lux, a company belonging to the Kaupthing Luxembourg’s largest borrower, Skúli Þorvaldsson.

According to Icelog sources in Luxembourg, familiar with the Immo-Croissance deals in 2008, the SK Lux purchase of Immo-Croissance left all the risk with Kaupthing Luxembourg, a consistent pattern in deals financed by Kaupthing for the bank’s favoured clients.

The second and third life of Immo-Croissance

A key person in the Immo-Croissance saga, as in the origin of Banque Havilland, is the lawyer Franz Fayot, Kaupthing Luxembourg’s administrator until the bank was sold in summer of 2009. It was during his time as administrator of Kaupthing Luxembourg that Immo-Croissance was put up for sale, as SK Lux defaulted when the Kaupthing loan came to maturity at the end of October 2008.

At the time, Dexia was interested in buying Immo-Croissance. Its offer was a set-off against Kaupthing debt to Dexia, in addition to a cash payment. Kaupthing Luxembourg however preferred to sell to an Italian businessman Umberto Ronsisvalle and his company, R Capital. Guðmundsson arranged the deal for Ronsisvalle through Consolium, a Luxembourg company set up by an Icelandic company, later taken over by Guðmundsson and a few other ex-Kaupthing bankers. Consolioum went through name changes, with some of the bankers’ wives later taking over the ownership as the bankers got indicted or were at risk from being indicted in Iceland.

Ronsisvalle offered €5.5m. In addition, Immo-Croissance would get a loan from Kaupthing Luxembourg of €123m to refinance the earlier loan. This time however the loan was against proper guarantees, not like the earlier loan to the Icelandic Immo-Croissance owners, where no guarantees to speak of were in place.

By the end of January 2009, Umberto Ronsisvalle was in charge of Immo-Croissance but only for some months. By early summer 2009, the Kaupthing-related directors were again in charge, amongst them Jean-François Willems.

The unexpected turn of events took place in early 2009. Ronsisvalle paid the €5.5m but asked for some payment extension since he had problems in moving funds. He had understood that Kaupthing had agreed but hours after he provided the funds, Kaupthing changed its mind: it announced the loan was in default and moved to take a legal action to seize not only Immo-Croissance but also the collaterals, getting hold of €35m. The thrust of Kaupthing’s legal action was that Ronsisvalle had tried to take over Immo-Croissance without paying for it.

Early on, a judge refuted this Kaupthing allegation, pointing out that there was both the down-payment of €5.5m and the guarantees, contrary to earlier arrangements. Ronsisvalle’s side of event is that Kaupthing manipulated a default in order to get hold of the cash and the collaterals, in addition to keeping the assets in Immo-Croissance, a saga followed by the Luxembourg Land.

Havilland, Immo-Croissance and EHP

The lawyer for Kaupthing in the Immo-Croissance case was Pierre Elvinger from the legal firm Elvinger Hoss Prussen, EHP, where Franz Fayot worked prior to taking on the administration of Kaupthing. As the case has stretched over a decade now, Pillar Securitisation replaced the old Kaupthing Luxembourg in the Immo-Croissance chain of legal cases. Franz Fayot has been a lawyer for Havilland in these cases.

In 2013, the case had reached a point where a judge had ordered Pillar to hand back Immo-Croissance to Ronsisvalle, its legal owner according to the judge. The problem was that in the meantime, Pillar had sold the company’s two most valuable assets, Villa Churchill and the building on Boulevard Royal.

In an article in Land, in July 2013, it was pointed out that Villa Churchill was sold to a company owned by three partners at EHP. The Boulevard Royal asset was sold to Banque de Luxembourg, a private bank where one EHP partner was a member of the board. In both cases, questions were raised regarding the price and a friendly deal.

EHP complained about the reporting and its comment was published in Land: EHP pointed out that Fayot ceased to be administrator as Banque Havilland and Pillar Securitisation came in to being in July 2009, whereas the two assets were sold in 2010. Also, that the price had to be agreed on by Immo-Croissance owner, Pillar Securitisation, i.e. the Pillar creditors’ committee.

What the law firm does not mention is that Fayot has stayed in business relationship with Banque Havilland, inter alia as a lawyer for Banque Havilland, for example in the Immo-Croissance cases and in a case against a Kaupthing employee whom Havilland has kept in a legal battle for over a decade.

Court cases related to this action are still ongoing but Ronsisvalle has so far won at every stage and has regained control of the company after fighting in court for years. He is now involved in a legal battle with Banque Havilland and Pillar regarding the assets sold. Since Immo-Croissance was placed in Pillar Securitisation, the outcome could in the end spell losses for the creditors of Pillar, mainly the two governments that provided the state-aid, which made Kaupthing Luxembourg an attractive and largely risk-free purchase.

The ex-Kaupthing employee hounded by Banque Havilland

On 9 October 2008, the day of Kaupthing Luxembourg’s default, the bank’s risk manager resigned. In his opinion, the bank had paid far too little attention to his warnings on exposures to the large favoured clients, with equally little notice being taken to the CSSF’s warnings on the same issues. The attitude of the bank’s management seemed to be that it could not care less.

In his resignation letter, the risk manager referred to the CSSF August letter to the Kaupthing management. In spite of the warnings, Kaupthing had, according to the risk manager, not taken any measures to diminish the risk, thus probably aggravating the bank’s situation. And by doing nothing, the bank had cast shadow over the reputation of both the bank itself and its risk professionals.

In addition, the bank had not dedicated enough resources to its risk management, leaving it both lacking in personnel and IT solutions. This had also led to the standards of risk management, as expressed in the bank’s Handbook, being wholly unachievable. All of this had become much more pressing since the bank’s liquidity position had turned dramatically for the worse after 3 October 2008.

As he had resigned by putting forth a harsh criticism of the bank, effectively making himself an internal whistle-blower, he expected to be contacted by the CSSF. When that did not happen, he did contact the regulator. It turned out that the letter had not been passed on to the CSSF and no one there was particularly interested in meeting him. After pressing his point, the risk manager did get a meeting with the CSSF, which showed remarkable little enthusiasm for his message.

The CSSF, in August 2008 so critical of the Kaupthing Luxembourg management, now seemed wholly uninterested in the bank. That is rather remarkable, given that the state of Luxembourg had risked millions of euros to revive the bank, now run by the bankers that the CSSF had earlier criticised.

Baseless accusations of hacking and theft of documents

The risk manager heard nothing further from the CSSF nor from the administrators but strangely enough he got a letter from Magnús Guðmundsson, with the Kaupthing logo as if nothing had happened. He finally brought his case to Labour Court in Luxembourg both to assert that he had had the right to resign and to get a final salary settlement with Kaupthing Luxembourg.

Although the risk manager quit Kaupthing around nine months before Banque Havilland came into being, that bank counter-sued the risk manager for hacking, theft of documents and breach of banking secrecy. Interestingly these allegations were raised in 2010, after the risk manager had been called in as a witness by the UK Serious Fraud Office and the Icelandic OSP.

The hacking and theft allegations ended with a judgment in 2015, where the risk manager won the case. The judge found that the risk manager had obtained these documents as part of his duties and could legitimately hold them as evidence in the Labour Court case. This case had delayed the Labour Court case, which then could only be brought to court by the end of 2017, a still ongoing case.

Technically, the labour case was part of the liabilities that Banque Havilland took over and litigations take time. The remarkable thing is that Banque Havilland has pursued the case without any regard for the evidence of illegalities taking place in Kaupthing as well as not paying consideration to the fact that the CSSF had severely criticised Kaupthing’s management.

After all the risk manager had quit Kauthing as he felt he could no longer work with the management the CSSF had found to be failing. Using the courts to harass people is a common tactic, used to the fullest in this case. Havilland has pursued the case forcefully, which is why the case is still doing the rounds in the various courts of Luxembourg thus undermining the risk manager both financially and in terms of his professional reputation.

If a Banque Havilland employee has ever contemplated criticising the bank or in any way bringing up anything about the bank, this case shows how the Havilland owners might react. It is not certain that the attitude of Luxembourg authorities regarding whistle-blowers rhyme with European legislation.

Luxembourg, the rotten heart of financial Europe

The ongoing legal wrangling with the risk manager and the Immo-Croissance are two stories that embody the strong and long-lived ties between Kaupthing Luxembourg and Banque Havilland. Both Franz Fayot and Pierre Elvinger from EHP, the company that still resides in Villa Churchill bought out of Immo-Croissance, have represented Banque Havilland in court.

Quite remarkably, the CSSF lost all interest in Kaupthing Luxembourg, after the bank failed. Instead, it chose to lend funds to its new owners, who had less than a stellar reputation. Owners, who kept the Kaupthing management, that had given rise to the CSSF’s earlier concerns.

In addition, after knowing full well what had gone on in Kaupthing Luxembourg and being fully informed about the criminal cases in Iceland, the Luxembourg Prosecutor, now seems to be dithering as to bringing a case related to Lindsor Holding, not to mention other cases that were never investigated.

This is the state of affairs in Luxembourg, still the rotten heart of financial Europe.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Lessons from Iceland: the SIC report and its long lasting effect / 10 years after

The Bill passed by the Icelandic parliament in December 2008 on setting up an independent investigative commission, the Special Investigative Commission did not catch much attention at the time. The goal was nothing less than finding out the truth in order to establish events leading up to the 2008 banking collapse, analyse causes and drawing some lessons. The SIC report was an exemplary work and immensely important at the time to establish a narrative of the crisis. But in hindsight, there is yet another lesson to be learnt: its importance does not diminish with time as it helps to counteract special interests seeking to rewrite history.

There were no big headlines when on 12 December 2008 Alþingi, the Icelandic parliament, passed a Bill to set up an investigative commission “to investigate and analyse the processes leading to the collapse of the three main banks in Iceland,”which had shaken the island two months earlier. The palpable lack of enthusiasm and attention was understandable: the nation was still stunned and there was no tradition in Iceland for such commissions. No one knew what to expect, the safest bet was to not expect very much.

That all changed when the Commission presented its results in April 2010. Not only was the report long – 2600 pages in print in addition to online-only material – but it did actually tell the real story behind the collapse: the immensely rapid growth of the banks, from one GDP in 2002 to ten times the GDP in 2008, the stronghold the largest shareholders, incidentally also the largest borrowers, had on the banks’ managements, the political apathy and lax regulation by weak regulators, stemming from awe of the financial sector.

Unfortunately, the SIC report was not translated in full into English; see executive summary and some excerpts here.

With time, the report’s importance has not diminished: at the time, it clarified what had happened thus preventing those involved or others with special interest, to reshape the past according to their own interests. With time, hindering the reshaping of the past has become of major importance, also in order to draw the right lessons from the calamitous events in October 2008.

What was the SIC?

According to the December 2008 SIC Act (in Icelandic), the goal was setting up an investigative commission, that would, at the behest of Alþingi, seek “the truth about the run-up to and the causes of the collapse of the Icelandic banks in 2008 and related events. [The SIC] is to evaluate if this was caused by mistake or neglect in carrying out law and regulation of the financial sector in Iceland and its supervision and who could be held responsible for it.” – In order to fulfil its goal the SIC was inter alia to collect information on the financial sector, assess regulation or lack thereof and come up with proposals to prevent the repetition of these events.

In some countries, most notably in South Africa after apartheid, “Truth Commissions,” have played a major part in reconciliation with the past. Although the remit of the Icelandic SIC was to establish the truth, the SIC was never referred to as a “truth commission” in Iceland though that concept has been used in foreign coverage of the SIC.

The SIC had the power to make use of a vast array of sources, both by calling in people to be questioned and documents, public or private such as bank data, including data on named individuals, data from public institutions, personal documents and memos. Data, normally confidential, had to be shared with the SIC, which was obliged to operate as any other public body handling sensitive or confidential information.

Although the SIC had to follow normal procedures of discretion on personal data the SIC could “publish information, normally subject to discretion, if the SIC deems this necessary to support its conclusions. The Commission can only publish information on personal matters of named individuals, including their financial affairs, if the public interest is greater than the interest of the individuals concerned.” – In effect, this clause lift banking secrecy.

One source close to the process of setting up the SIC surmised the political intentions behind the SIC Act did not include lifting banking secrecy, indicating that the extensive powers given to the SIC were accidental. Others have claimed the SIC’s extensive powers were always part of the plan. I am in two minds about this but my feeling is that the source close to the process was right – the powers to scrutinise the main shareholders were far greater than intended to begin with.

Naming the largest borrowers, incidentally also the largest shareholders

Intentional or not, the extensive powers enabled naming the individuals who received the largest loans from the banks, incidentally their largest shareholders and their closest business partners. This was absolutely essential in order to understand how the banks had operated: essentially, as private fiefdoms of the largest shareholders.

In order to encourage those called in for questioning to speak freely, the hearings were held behind closed doors; there were no public hearings. The SIC had extensive powers to call people in for questioning: it could ask for a court order if anyone declined its invitation, with the threat of taking that person to court on grounds of contempt in case the invitation was declined.

Criminal investigation was not part of the SIC remit but its power to call for material or call in people for questioning was parallel to that of a prosecutor. As stated in the report, the SIC was obliged to inform the State Prosecutor if there was suspicion of criminal conduct:

The SIC’s assessment, pursuant to Article 1(1) of Act no. 142/2008, was mainly aimed at the activities of public bodies and those who might be responsible for mistakes or negligence within the meaning of those terms, as defined in the Act. Although the SIC was entrusted with investigating whether weaknesses in the operations of the banks and their policies had played a part in their collapse, the Commission was not expected to address possible criminal conduct of the directors of the banks in their operations.

As to suspicion of civil servants having failed to fulfil their legal duties, the SIC was supposed to inform appropriate instances. The SIC was not obliged to inform the individuals in question. As to ministers, the SIC was to follow law on ministerial responsibility.

The three members

The SIC Act stipulated it should have three members: the Alþingi Ombudsman, then as now Tryggvi Gunnarsson, an economist and, as a chairman, a Supreme Court Justice. The nominated economist was Sigríður Benediktsdóttir, then lecturer at Yale University (director of Financial Stability at CBI 2012 to 2016 when she returned to Yale). The chairman was Páll Hreinsson (since 2011 judge at the EFTA Court).

In addition to the Commission there was a Working Group on Ethics: Vilhjálmur Árnason professor of philosophy, Salvör Nordal director of the Centre for Ethics, both at the University of Iceland and Kristín Ástgeirsdóttir director of the Equal Rights Council in Iceland. Their conclusions were published in Vol. 8 of the SIC report.

In total, the SIC had a staff of around 30 people. As with the Anton Valukas report, published in March 2010, on the collapse of Lehman Brothers, organising the material, especially the data from the banks, was a major task. The SIC had access to the databases of the three collapsed banks but had only limited data from the banks’ foreign operations.

There were absolutely no leaks from the SIC, which meant it was unclear what to expect. Given its untrodden path, the voices expressing little faith were the most frequently heard. I had however heard early on, that the SIC had a firm grip on turning material into searchable databases, which would mean a wealth of material. With qualified members and staff, I was from early on hopeful that given their expertise of extracting and processing data the SIC report would most likely prove to be illuminating – though I certainly did not imagine how extensive and insightful it turned out to be.

Greed, fraud and the collapse of common sense

After the October 2008 collapse, my attention had been on some questionable practices that I heard of from talking to sources close to the failed banks.

One thing I had quickly established was how the banks, through their foreign subsidiaries, had offshorised their Icelandic clients. This counted not only for the wealthy businessmen who obviously understood the ramifications of offshorising but also people with relatively small funds. These latters had in many cases scant understanding of these services.

In the last few years, as information on offshorisation has come to the light via Offshoreleaks etc., it has become clear that Iceland was – and still is – the most offshorised country in the world (here, 2016 Icelog on this topic). Once the “art” of offshorisation is established, with all the vested interests accompanying it, it does not die easily – this might be considered one of the failed banks’ more evil legacies.

Another point of interest was how the banks had systematically lent clients, small and large, funds to buy the banks’ own shares, i.e. Kaupthing lent funds to buy Kaupthing shares etc. Cross-lending was also a practice: Bank A would lend clients to buy Bank B shares and Bank B lent clients to buy Bank A shares. This was partly used to hinder that shares were sold when buyers were few and far behind, causing fall in market value. In other words, massive market manipulation had slowly been emerging. Indeed, the managers of all three failed banks have in recent years been sentenced for market manipulation.

It had also emerged, that the banks’ largest shareholders/clients and their business partners had indeed been what I have called “favoured clients,” i.e. enjoying services far beyond normal business practices. One side of this came to light in the banks’ covenants in lending agreements: in the case of the “favoured clients,” the lending agreements tended to guarantee clients’ profit, leaving the banks with the losses. In other words, the banks took on far greater portion of the risk than these clients.

Icelog blogs I wrote in February 2010, before the publication of the SIC report, give some sense of what was known at the time. Already then, it seemed fair to conclude that greed, fraud and the collapse of common sense had been decisive factors in the event in Iceland in October 2008.

Monday morning 12 April 2010 – when time stood still in Iceland