Archive for March, 2012

Guess who came to a Downing Street dinner? David Rowland

The UK Conservative Party battles against the sleaze that’s oozing out in the wake of the under-cover Sunday Times interview with Tory treasurer Peter Cruddas, now understandably the ex-treasurer. In the interview, Cruddas sets the rates for access to Tory leading lights, mentioning that £250.000 will get you a dinner with Prime Minister David Cameron. A case now called “Cash for Cameron” by the UK media.

Cameron completely denies all this, finds Cruddas’ entrepreneurship on behalf of the party “completely unacceptable.” Having admitted to invited some main donors to dinner, Cameron was forced to publish a list of those favoured with such favours. On the list is the man who was going to be treasurer himself, until he found out he didn’t have the time. That decision might have had something to do with a series of very unflattering articles that the Daily Mail published on him.

But however unflattering Daily Mail’s reporting did no lasting harm to Rowland’s reputation in Downing Street. On Feb. 28 last year, David Rowland and his wife were invited to dinner, together with Baron Andrew Feldman, ennobled by his friend Cameron for whom he has been a diligent fundraiser and now a co-chairman of the Conservative Party. They will most likely have sat in this nicely conservative state room above nr 11 Downing Street and sipped whatever those with conservative leanings sip.

Cruddas pointed out that by paying the £250.000 one would be in the “premier league” and would be listened to. Rowland is way beyond that since his contribution to the party is counted in millions of pounds. So what might he have discussed with Cameron? Apart from the usual, such as too much taxation, Rowland might have talked about the fantastic opportunities he finds in having a bank in Luxembourg and Monaco, a newspaper in Latvia and shares in the Icelandic MP Bank, not to mention Belarus.

Since Belarus has been in the news lately for political repression and horrors, Cameron could have been interested in Rowland’s Belarus venture, the first FDI fund there. At the time, Havilland’s press release was probably still on the Havilland website but it’s now been removed. We don’t know how Cameron’s staff prepared these dinners but most likely Cameron was more listening than questioning. After all, Rowland and other guests did quite a bit to bring Cameron to Downing Street and critical questions might have been as unacceptable as Cameron thought Cruddas’ fundraising initiative.

*Rowland also has ties to Prince Andrew. Here are links to other Icelog entries on Rowland.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Stanford, Millen and Tchenguiz: victims or favoured clients?

“In my opinion, it is quite wrong that a bank can pretend to have money and security which it doesn’t have, generate a false balance sheet and use its own customers to fund acquisition ambitions.” According to the Guardian, the fashion entrepreneur Karen Millen is pursuing a series of legal claims against the Kaupthing estate, together with her ex-husband Kevin Stanford (more on his Icelandic contacts). Millen is of the opinion that Kaupthing wasn’t entirely straight about its position. She might not be the only one to think so – but before it all went to painfully wrong, her ex-husband was indeed very close to the Kaupthing managers. It’s unclear how well informed Stanford kept his ex-wife on their business dealings. He was the financial motor in their cooperation, Millen the creative one.

Millen and Stanford built up a fashion label, the Karen Millen name is still prominent on UK high streets. But the name no longer belongs to her. Millen has lost her name to Kaupthing. She is understandably upset but she isn’t the first designer to lose her/his name to the bankers by being careless about the small print.

From the SIC report and other sources it’s clear that banking the Icelandic way implied bestowing huge favours on a group of chosen clients – in all three banks the banks’ major shareholders and an extended group around them. As so often pointed out on Icelog, these clients got convenant-light and/or collateral-light loans. In some cases the bankers promised their clients that the collateral wouldn’t be enforced – or the collateral were unenforceable for some reason. They were offered a “risk-free business” – ia risk-free for the customer whereas the bank shouldered all the risk and eventual losses. (This screams of breach of fiduciary duty, indeed part of charges brought in some cases by Office of the Special Prosecutor and not doubt more to come.)

After the collapse, some of Kaupthing’s favoured clients have claimed they were victims of Kaupthing’s managers who did not inform them of the bank’s real standing. Karen Millen is the latest to complain of Kaupthing misleading her. She is, understandably, outraged at not being able to use her name for her label. A clever lawyer would have made sure it couldn’t happen. Stanford was evidently very close to the Kaupthing managers, which might have lulled him into the false believe that he didn’t need to be too careful about the wording of the contracts.

How close was Stanford to Kaupthing? Just before the collapse he was the bank’s fourth biggest shareholder and among the largest borrowers – the familiar correlation between large shareholding and huge loans in the Icelandic banks.

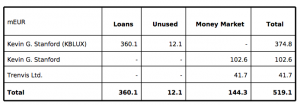

Here is an overview of Stanford’s loans September 2008:

What was this enormous business that Stanford was running that merited loans of €519m?

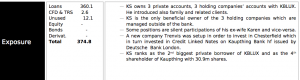

Here is how Stanford was introduced on the loan overview of exposures exceeding €45m:

Pay attention here. Stanford introduced “family and related clients.” – Did he, as sometimes happens, get paid for the introduction? – And then this, that some of this was “silent participation” of his ex-wife and vice versa. Did she have a full insight into how her name was used by her husband? Noticeably, he was the second biggest private borrower in Kaupthing Luxembourg, where all the dodgiest loans were issued.

Stanford’s Icelandic connections are on the whole quite intriguing. He wasn’t only closely connected to Kaupthing but also to Glitnir, at least after Jon Asgeir Johannesson, with ia Hannes Smarason and Palmi Haraldsson, became the bank’s largest shareholder in summer 2007. When Glitnir financed a clever dividend scheme in Byr, the building society, Millen suddenly appeared as one of the stakeholders in Byr. Was that because she was so keen to invest in an Icelandic building society? Some of Stanford’s fashion businesses were joint ventures with Johannesson and his company, Baugur.

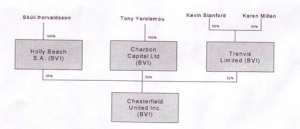

Stanford was also close enough to Kaupthing be part of a clever set-up to influence the bank’s scarily high CDS in the summer of 2008. Together with Olafur Olafsson, Kaupthing’s second largest shareholder, Tony Yerolemou and Skuli Thorvaldsson – all of them in the Kaupthing inner circle in terms of the business opportunities they got from the bank – Stanford and Millen owned one of three companies financed by Kaupthing to buy Kaupthing CDS. This was the set-up:

This scheme doesn’t seem to have hit Stanford and Millen with losses in spite of a loan of €41m to this entreprise.

Last year, Stanford wrote a letter to the Kaupthing Singer & Friedlander estate to substantiate his claim that he should not pay back KSF £130m he had borrowed to buy Kaupthing shares. According to his understanding, this lending was part of Kaupthing’s support scheme, in other words (which Stanford didn’t use) ‘market manipulation.’ – Stanford is and wants to be taken seriously as a business man. Didn’t he see anything strange in the fact that a bank was lending him money, with no risk for Stanford, to buy its own shares, with (if the scheme was the usual one) nothing but the shares as a collateral?

Stanford says that after talking to former Kaupthing Singer & Friedlander staff he now understands that the Kaupthing Edge deposits were used to buy ‘crap’ assets from Kaupthing Iceland, which lent the money on to Kaupthing Luxembourg that then had the money to lend to high net worth clients like Stanford. This scheme, according to Stanford, enabled senior Kaupthing managers to sell their Kaupthing shares.

This is an interesting description of the use of the Kaupthing Edge deposits, which (contrary to Landsbanki’s Icesave) were in a UK subsidiary and consequently guaranteed by the UK deposit guarantee scheme.* Stanford is right that the money was lent to high net worth clients – but not just to any clients: it was lent to the favoured clients who got the conventant-light loans. Kaupthing senior managers may have sold some of their shares but they did by far not sell out – it would have caused too much of attention and undermined trust in the bank.

Other big Kaupthing clients, like Vincent and Robert Tchenguiz, have also complained of being the victims of Kaupthing’s market manipulation. All these people are – or have been – locked in lawsuits with Kaupthing. The claims to the media is part of their PR strategy.

Being duped by Kaupthing means someone did the duping, allegedly the managers of the bank. Yet, none of these ‘ill-treated’ is suing any of the managers. They are suing the failed bank’s estate. That’s logical because the estate has assets. But it also raises the question if the strong bonds, which clearly connected the Kaupthing senior managers and their major clients, have survived the collapse and the consequent losses.

It’s also worth noticing that in spite of enormous loans that the favoured clients got, they have, like Stanford and the Tchenguiz brothers, proved remarkably resilient to losses. That may be due to luck, business acumen or both – but a part of it might also be the convenant- and collateral-light loans that Kaupthing did, after all, bestow on them. Which is part of the Kaupthing-related cases that both the Serious Fraud Office and the OSP are investigating. This way of banking runs against all business logic. The question is what sort of logic it followed.

*The fact that Kaupthing Edge was guaranteed by the UK deposit guarantee seems to be one of the motives for the SFO investigation. I find it incomprehensible that SFO isn’t investigating Landsbanki’s Icesave, which the UK Government did bail out – hence the Icesave dispute.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

The Irish Mahon report: a political corruption uncovered (albeit of the 80s and the 90s)

The 1990s in Ireland were characterised – much like the last decade – by property speculations, based on political connections. There were rumours about politicians getting paid for planning favours. These rumours were so persistent that in November 4 1997 a Tribunal of Inquiry into Certain Planning Matters and Payment was set up. Today, Thursday March 22, good fourteen years later and costing €300m, the Mahon tribunal, called after Judge Alan P. Mahon now its chairman, has published a 3270 pages final report, following four previous reports. It is, to say the very least, a damning description of politics, money and power in Ireland of the 1990s but also points out matters to consider in terms of ethics, regulators and politics.

Ex-Prime Minister Bertie Ahern and his source of money are at the centre of the report – and yes, the report finds ia that he accepted corrupt payments and used the accounts of his daughter Cecelia, now a famous writer, and wife to hide his corrupt income. His earlier explanations were “untrue” – Reuters is more blunt and says Ahern “lied.” Others named for dishonourable sources of money are former EU Commissioner and Minister Padraig Flynn, who on a popular chat show in 1999 defiantly refused rumours and accusations that he had taken money for political favours. The new report establishes that this wasn’t quite true.

Flynn and Ahern are only a few of many leading politicians from the 80s and the 90s whose reputation is now destroyed by the new report. A number of politicians from both main parties, Fianna Fail and Fine Gael, have been brought to court or indicted and cases are still running. More might be to come.

The Irish media and the whole nation has plenty to digest today. This investigation regards cases from over a decade ago and practices reaching back to the 80s. The report points out the staggering apathy there has been in Ireland regarding corruption. This might now be changing – but the question the Irish must be asking them now is how much Ireland has changed.

I have earlier compared Ireland and Iceland, ia on corruption (see ia here and here). After the Icelandic SIC report I pointed out that Icelanders knew a good deal more on their banking failure than Ireland. That changed to a certain degree after the publication of the Nyberg report though the SIC report goes into far greater detail on the major shareholders and the banks’ big clients.

It’s interesting to note that in spite of the entrenched corruption in Ireland it seems to be confined to the relationship between the property sector and politics. Ireland is doing well in attracting foreign investments in high-tech and biotech whereas Iceland is struggling in this respect.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

After the Haarde trial: a farce – or, actually, a trial?

There has widespread dismay in Iceland at the trial over ex-PM Geir Haarde – but not everyone is dismayed for the same reasons. Some are irritated that politicians and civil servants generally claimed nothing could have been done to prevent the collapse of the banks and that bankers can’t see they have done anything wrong. Others are upset that only one politician is on trial – there should have been more… or none.

When asked why Kaupthing had failed, the bank’s former CEO Hreidar Mar Sigurdsson said straightforwardly it had failed because of the Emergency Bill – the legislation passed on Monday Oct. 6 2008 to prevent a total chaos in Iceland as the banks were collapsing. Sigurdsson’s view is, to say the very least, quite narrow. On Friday Oct. 3 the Bank of England had already taken action against Kaupthing by taking over all new deposits to Kaupthing. Sigurdsson didn’t mention this action, which marked the beginning of actions against Kaupthing in the UK.

It needn’t come as any surprise that no one accepts any responsibility – that was already clear from the SIC report, ia based on extensive interviews with many of those involved. This tone of “it wasn’t me” or “nothing could be done” is abundantly clear from the quotes in the report.

It’s unlikely that any of the witnesses took much joy in bearing witness. Many of them will still feel uneasy about the past – and their future. Several of the witnesses at the Haarde trial have already been indicted by the Office of the Special Prosecutor – Sigurdsson is one of them – and/or are being sued by the Winding-up Boards of the banks and others might face lawsuits and charges. Everything they say will be coloured by their situation. Many of them have most likely rehearsed their answers with their lawyers.

Complaints that the trial is a farce seem to rest on a wholly unrealistic understanding of the nature of the trial. The trial is held because Haarde is accused of failures in office. The charges are built on a documentation of alleged failures. The trial is an act where the prosecutor seeks to clarify the documents and Haarde’s defence lawyer seeks to defend his client. The High Court Judges will come to their conclusion in 4-5 weeks.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Glitnir pays out its priority claims

Today, the Winding-up Board of Glitnir is paying out the whole of its priority claims, in total about £500m. About half is being payed out at once, the rest are claims that are still disputed. The disputed sum now goes to an escrow account, which will collect interest rates as of today. The happy recipients of the pay-out are 55 UK local councils and universities.

After taking over the failed bank, the ResCom of Glitnir (contrary to Kaupthing) never brought its foreign currency to Iceland which means that the currency controls in Iceland don’t affect its currency holdings. The Glitnir currency holdings cover about 80% of the priority claims now paid out. The remaining 20% are paid out in Icelandic krona. Because of the currency control, this 20%, in Icelandic krona, is being held on an account with the Central Bank of Iceland. The owners of these krona can participate in the CBI’s auction – or if they are adventurous they could of course use their krona to invest in Iceland, buy goods there etc. The bids for the next CBI auction have to be in by March 28, see the CBI’s announcement here.

They payout has been widely covered in the UK press (I’ve been on three BBC interviews) and has obviously raised hopes for more money to return. Icesave depositors have been paid by the UK Government so there are no angry depositors camping outside the Icelandic Embassy – now it’s the UK Government waiting for the Icesave money from the Landsbanki WuB. Then there is of course this small matter of unpaid interest and the ESA case – yet another collapse saga.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Iceland is doing pretty well, thank you – except in FDI

Iceland is not only on track but is actually ahead in paying off its loans to the IMF, as this press release today indicates:

“Iceland announced today that it repaid, ahead of schedule, obligations to the IMF amounting to some SDR 288.8 million (US$ 443.4 million). The payment was made on March 12.

The early repayment is about one fifth of the SDR 1.4 billion (US$2.15 billion) that Iceland borrowed from the IMF under its Stand-By Arrangement (SBA) (see Press Release 08/296). The amounts repaid early are the obligations falling due in 2013 under the original repayment schedule.

Together with a scheduled payment made in February 2012, this early repayment will reduce Iceland’s outstanding obligation to the IMF to SDR 1.041 billion (about US$1.60 billion). This outstanding balance is projected to be repaid during 2012-16.

After this early repayment, and taking into account a similar early repayment of Iceland’s Nordic loans, reserve adequacy—as measured by the ratio of reserves-to-short term debt—will remain above the standard benchmark of 100 percent.”

The recovery in Iceland has, in many ways been remarkably good and quick, considering the sharp fall, following the collapse of its three main banks in October 2008.

Richard Barley, WJS, recently compared the Icelandic and the Irish crisis – who had a better crisis? There are striking similarities:

The costs of dealing with banking failure have been similar. Bank recapitalization cost about 45% of GDP in Iceland and 40% in Ireland. Both saw deep economic declines of 12%-13% of GDP. And both ended up with budget deficits in the double digits, as a percentage of annual GDP, which have required stiff fiscal tightening. Government debt is lower in Iceland, but not by much, reaching 100% of GDP in 2011. The difference is that Iceland grew 3% in 2011, Fitch estimates, versus 1% for Ireland.

The growth in Iceland is promising but Barley points out that Ireland is doing strikingly better in one aspect:

Longer-term, euro membership should help Ireland lure investment and boost exports: Even in 2011, there was a 30% increase in companies investing in Ireland for the first time. Over time, that may prove the deciding factor.

Barley singles out the deterring effect of the currency controls to Iceland – it’s difficult to lure foreign investors over the sky-high barriers of the currency controls. Unfortunately, the problem of luring foreign investors is both deeper, longer-running and more severe than just the currency controls, in place since post-collapse 2008.

Historically seen, it’s always been difficult to attract foreign investors to Iceland. In this respect, Italy and Iceland are similar. Foreigners often sense in Iceland that things are done in some specific Icelandic ways that foreigners find hard to understand and penetrate. Personal relationships matter everywhere but in Iceland it’s very difficult to get anywhere at all without the right Icelandic personal relationships. Ad hoc decisions and opacity cloud the island.

Who are investing in Iceland? David Rowland has invested in a small bank, MP Bank. Rowland bought the Kaupthing Luxembourg operation in the summer of 2009. He was chosen to be treasurer for the British Conservative Party but after the Daily Mail published a series of rather unflattering articles on him Rowland realised he didn’t have the time to dedicate himself to the unpaid honorary but extremely influential job. Mike Ashley, owner of Newcastle United football club, is another investor in MP Bank. He was a client of Kaupthing and an intimate friend of Kaupthing Singer & Friedlander’s CEO Armann Thorvaldsson, according to Thorvaldson’s book, Frozen Assets.

Iceland and Ireland are small countries and there is quite a bit of cronyism in both countries. In Ireland, the cronyism is heavily connected to the building sector, which collapsed spectacularly in 2008 and brought down the three main banks. Other sectors, like high-tech and bio-tech, seem to be outside the cronyism sphere and are healthily attracting foreign investors. For some reason, Iceland is struggling in this respect. The feeling is that it’s not just because of the currency controls and not being members of the eurozone.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

The Haarde trial drawing to an end: a summary

State prosecutor Sigridur Fridjonsdottir has now summed up her reasoning in the case against ex-PM Geir Haarde. She points out that Haarde is not on trial for not preventing the collapse but for not taking action. She has listed a whole raft of warnings, meetings and other interaction that Haarde did not act upon. She also points out that there were plenty of warnings, ia from the CBI and Haarde as an economist and minister should have been able both to understand the warnings and take action. Maximum sentence is two years imprisonment. The prosecutor stated that the seriousness of the offence could constitute extenuating circumstances. In contrast, a clean criminal record and the time, which has elapsed since the offence was committed, might be alleviating circumstances. The sentence can be up to two years’ imprisonment.

Haarde’s defense lawyer will be speaking tomorrow.

One of the witnesses, Tryggvi Palsson former head of financial stability at the CBI, pointed out in his testimony that CBI’s reports from 2003 indicated that financial stability never improved. In May 2008 it said: “Present circumstances will test the banks’ resistance.” – Testing indeed. This is central bank speak for an unmitigated and colossal catastrophe.

Both Palsson and other CBI staff pointed out that there were signs of grave problems in the banks already in 2005. – It’s still a mystery why rating agencies and others who sounded warnings in 2006 seemed to retract these warnings. Many of the witnesses spoke of the mini crisis in 2006, which almost led to the collapse of the banks. They did recover in the sense that they saved themselves but they were in a bad shape. Instead of selling assets and strengthen the operations bad loans and loans to buy their own shares escalated. Bad assets replaced good ones.

The central question is if the Government had the tools to do anything. There was abundant evidence at the trial that yes, the Government could have taken action but didn’t. And interesting example of how indirect action could be used is the Government’s opposition to Kaupthing’s acquisition of NIBC. When the Kaupthing management sensed the political opposition it backed off. – If the acquisition had gone through with it, it would most surely have spelled an earlier demise of Kaupthing but that’s another story.

Former Minister of Finance Arni Mathiesen indicated the lack of implementing policy when he said it was the Government’s policy to reduce the size of the banking sector. It’s difficult to find any indication of implementation. The bankers have said that they didn’t sense that there was any ongoing action in this direction. It was at most mentioned or loosely indicated. Nothing more. In general, the banks led the way, the Government followed.

The ongoing question through the trial is: what could have been done? David Oddsson former Governor of the CBI said that something could always be done. If the meaning behind this question is: could the banks be saved? No, not from 2005 or so. The state and the banks were like a mouse and an elephant. The mouse can’t lift the elephant. In addition to size, the banks were in reality Siamese triplets – if one failed, they would all fail.

Moving the banks abroad was vaguely discussed. Kaupthing had a plan to move. The question is how realistic this was. It would have taken 1-2 years, by 2008 it was too late as a solution for an imminent problem. Was there any country that would have wanted the banks to register there? And what would the due diligence, taken by any FSA have shown? The fact that the Winding-Up Boards of Landsbanki and Glitnir have now sued the auditors, incidentally PwC for both banks, for the audits of 2007 and 2008 makes this plan of moving dubious if not wholly unrealistic.

At the end of 2007 the banks were way beyond what the state could shoulder and save. At that point, with a catastrophe in sight – for anyone who was in the position to see it – the Government should have prepared for the banks’ end. There were some tentative actions such as a draft by mid 2008 for an Emergency Bill, passed on October 6 2008. Another tentative action was the consultative group, which never functioned properly.

Tryggvi Palsson said that the testimonies of the bankers at the Haarde trial showed they were still in denial of what happened. Kaupthing’s former chairman of the board Sigurdur Einarsson said that one reason for the bank’s fate was CBI’s high interest policy. – That’s one way of seeing it but banks were truly good at exploiting it, ia by selling forex loans and by selling the Glacier bonds – and all of this strengthened the krona, which influenced the CBI rates. The question is: where the banks perpetrators or victims? The understanding from the many witnesses is that the banks really ruled, not the Government.

The trial finishes tomorrow. The court’s ruling is expected in 4-6 weeks.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Who were the “muppets” of the Icelandic banks?

Today, Greg Smith, a Goldman Sachs employee in London, suddenly shot to fame, at least in the banking world. He is leaving Goldman because he thinks its environment is “toxic and destructive.” But instead of just leaving in silence he penned a resignation letter as an Op Ed piece for the New York Times, published today, on his last day at work. It might well have been the most read serious piece in the media today.

He’s uncomfortable with the bank’s business ethics: Goldman sees nothing wrong in selling junk and rubbish to its clients, making the clients lose while the bank makes money. A lot of it. In the infamous Abacus case, Goldman actually ended up paying $550m to settle claims – without admitting it did anything wrong – when it failed to disclose that the product sold was designed to fail. A favoured Goldman client was allowed to make money on it, with the bank. Everyone else was magnanimously allowed to lose on it. But this case and other similar haven’t taught Goldman’s managers any humility, according to Smith. “Over the last 12 months I have seen five different managing directors refer to their own clients as “muppets,” sometimes over internal e-mail.”

Now, it’s normal in business that some lose, others gain. But, as Smith points out, it’s interesting if there is a pattern to it and if a bank thinks nothing of clients’ predictable losses. One of the striking thing about the Icelandic banks is to consider who lost and who profited. Or, in the Goldman thinking, who were the muppets?

There were quite a number of muppets among the clients of the Icelandic banks. There were for example plenty of ordinary people who trusted the banks with their savings and invested in the banks’ money market funds, not knowing that these funds were used to buy bonds and shares in failing holding companies. These clients didn’t know that the Icelandic banks ran their money market funds quite a bit differently from what is the acknowledged banking practice (even with Goldman). This is one of the many bad banking practices stories in the SIC report – a story the Special Prosecutor might one day show an interest in.

Then there are those who put some savings into shares in the banks – Kaupthing had some 33.000 shareholders. These people didn’t know that the banks were buying shares off some shareholders shortly before the collapse. These people were just allowed to lose the savings they put into the shares.

The most striking muppets were possibly the pension funds. They lost heavily because they could be led to manage their investments against the interest of the funds and their owners but in the interest of the banks and their largest shareholders. This is particularly clear from the fact that the funds invested in unlisted companies – and from the fact that the funds hedged their foreign assets (that in themselves hedge the funds’ domestic assets) with the banks. A report* from February on the pension funds concludes that after mid 2007 currency hedges turned very risky, the pension funds should have sought advice – and the banks should have warned the funds. But they didn’t. Losses from currency hedges are about 12-15% of the total losses – some have yet to be settled with the banks’ Winding-Up Boards.

It’s safe to conclude that much of the funds’ losses were incurred because the banks gave the pension funds (as others) wrong or misleading information. In a recent report (only in Icelandic) by an expert group, on behalf of VR, one of the biggest Icelandic pension funds, the experts conclude that VR “and other pension funds should consider suing those who possibly played a role in giving wrong information to shareholders, bondholders and others with an interest. Those who could possibly be sued are the managers of the banks and companies and their auditors. … It can be critcised that the pension funds haven’t taken the initiative here or shown any interest in doing so.”

The pension funds report shows close personal relationships between the banks and the funds though more work could have be done on that issue. The banks are no longer pullings strings – but perhaps personal relations and the wish to move on and away makes some people behave as if the strings, holding the muppets, were still in place.

*The English summary starts on p. 29. See here for an earlier Icelog on the report.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

The Haarde trial: witness list for tomorrow changed

The previous list of witnesses due to appear tomorrow at the Haarde trial has been changed. Those who now have been called in are Tryggvi Palsson previous head of financial stability at the Central Bank of Iceland, Joh Thorsteinn Oddleifsson former head of treasure, Landsbanki, Steingrimur Sigfusson member of Parliament (and now Minister for Economic Development) and Arni Mathiesen former Minister of Finance. It is also expected that Geir Haarde will again be questioned tomorrow.

The link to the charges, in Icelandic, is here.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

The Kaupthing clients Tchenguiz, Fiyaz and Usmanov: allegations fly in court

“In Praise of Folly” is a book published by Erasmus of Rotterdam in 1509. Happily, businessmen of all sorts are still committing the folly of chasing each other in court, thus exposing their dirty linen in public. The most spectacular recent case of this folly was the clash of the oligarchs Boris Berezovsky and Roman Abramovitch. If it hadn’t been so outrageously offensive to hear the two recounting tales of corruption – as if it all was business as usual – in an English courtroom, it would have been utterly hilarious.

But the two oligarchs aren’t the only billionaires willing to stage a public fight at the Royal Courts of Justice. Simon Bower at the Guardian has unearthed some interesting stories from an ongoing court case involving Vincent Tchenguiz and his countryman, confidante, childhood friend and employee Keyvan Rahimian. Rahimian was so close to Tchenguiz that while he worked for him he also lived in his house. In late 2008 they fell out bitterly. Rahimian claims his former friend owes him £6.7m – Tchenguiz claims that Rahimian stole from his and is suing him for £2m.

But there is more to this case. In court, Tchenguiz has accused Rahimian of taking consultancy fees of almost €791,000 from a company called Carule, in undisclosed ownership, while Rahimian was working for him. Lawyers for Tchenguiz seem to have an idea where the money came from. They asked Rahimian if the oligarch Alisher Usmanov had paid him or a Pakistani millionaire, Alshair Fiyaz, recently in the UK news after abandoning a bid to buy a fashion chain, Peacock.

Rahimian only admitted that the payment was for financial research, though not disclosing who paid him. He says Usmanov is a friend but that he has never traded for him. Rahimian admits that he later got €388,000 to buy a Mercedes Benz in Paris and then passed the car on to Fiyaz.

All sorts of interesting pieces of information have popped up in this case, according to the Guardian:

“In angry exchanges, Rahimian accused Tchenguiz’s lawyers of raising irrelevant matters in the hope of embarrassing him in court. The property tycoon’s counsel made similar accusations about the evidence that Rahimian has sought to include. They claim that Rahimian is making “irrelevant” allegations that money transfers had been made, using his account, to pay for “eastern European models to come to the UK”. They characterise this as a threat and say Rahimian is hoping to embarrass Tchenguiz into a settlement of an otherwise “ridiculous” claim.”

Rahimian seems to be claiming that his accounts were used to pay for Eastern European girls, apparently for Tchenguiz. Why Tchenguiz is so touchy about this matter is difficult to understand since every article on him is almost invariably with photos of him with more than one lady. Perhaps he and Dominque Strauss Kahn see eye to eye on this: that any hint of money being paid for female company is abhorrent to them.

The question is still why this stream of money was going through the accounts of Rahimian, while he was working for Tchenguiz.

But the names of Tchenguiz, Usmanov and Fiyaz are not only united in the protocols of the Royal Court of Justice. Their names are to be found in Kaupthing loan books – they are all mentioned on the Kaupthing overview of larger than €45m exposures, presented to the Kaupthing management on September 25, 2008 (and later leaked to Wikileaks: Tchenguiz p62; Fiyaz p67; see here on Usmanov and Kaupthing) – the loans to these three allegedly had questionable collaterals.

This case is a further reminder that it’s not only in the present court case that there are untold stories. The feeling is that there are untold stories about the connections between some of the Kaupthing clients and why they all ended up being Kaupthing clients.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.