Archive for April, 2015

This time, no different from earlier: FX risk hidden from borrowers

The Swiss Franc unpegging from the euro 15 January this year brought the risk of foreign currency borrowing for unhedged borrowers yet again to the fore. In Central, Eastern and South-Eastern Europe lending in Swiss Franc and other foreign currency, most notably in euros, has been common since the early 2000s, often amounting to more than half of loans issued to households. The 2008 crisis put some damper on this lending, did not stop it though and in addition legacy issues remain. Now, actions by foreign currency borrowers in various countries are also unveiling a less glorious aspect: mis-selling and breach of European Directives on consumer protection. Senior bankers involved in foreign currency lending invariably claim that banks could not possibly foresee FX fluctuation. Yet, all of this has happened earlier in different parts of the world, most notably in Australia in the 1980s.

“The 2008-09 financial crisis has highlighted the problems associated with currency mismatches in the balance sheets of emerging market borrowers, particularly in Emerging Europe,” economists at the European Bank of Reconstruction and Development, EBRD, Jeromin Zettelmeyer, Piroska Nagy and Stephen Jeffrey wrote in the summer of 2009.*

In the grand scheme of Western and Northern European countries this mismatch was a little-noticed side-effect of the 2008 crisis. But at the EBRD, focused on Central, Eastern, South East European, CESEE, countries, its chief economist Erik Berglöf and his colleagues worried since foreign currency, FX, lending was common in this part of Europe. FX lending per se was not the problem but the fact that these loans were to a great extent issued to unhedged borrowers, i.e. borrowers who have neither assets nor income in FX. This lending was also partly the focus of the Vienna Initiative, launched in January 2009 by the EBRD, European and international organisations and banks to help resolve problems arising from CESEE countries mainly being served by foreign banks.

In Iceland FX lending took off from 2003 following the privatisation of the banks: with the banks growing far beyond the funding capacity of Icelandic depositors, foreign funding poured in to finance the banks’ expansion abroad. Icelandic interest rates were high and the rates of euro, Swiss Franc, CHF and yen attractive. Less so in October 2008 when the banks had collapsed: at the end of October 2007 1 euro stood at ISK85, a year later at ISK150 and by October 2009 at ISK185.

After Icelandic borrowers sued one of the banks, the Supreme Court ruled in a 2010 judgement that FX loans were indeed legal but not FX indexed loans, which most of household loans were. It took further time and several judgements to determine the course of action: household loans were recalculated in ISK at the very favourable foreign interest rates. Court cases are still on-going, now to test FX lending against European directives on consumer-protection.

In all these stories of FX loans turning into a millstone around the neck of borrowers in various European countries senior bankers invariably say the same thing: “we couldn’t possibly foresee the currency fluctuations!” In a narrow sense this is true: it is not easy to foresee when exactly a currency fluctuation will happen. Yet, these fluctuation are frequent; consequently, if a loan has a maturity of more than just a few years it is as sure as the earth revolving around the sun that a fluctuation of ca. 20%, often considerably more, will happen.

Interestingly, many of the banks issuing FX loans in emerging Europe did indeed make provisions for the risk, only not on behalf of their clients. According to economist at the Swiss National Bank, SNB, Pinar Yeşin “banks in Europe have continuously held more foreign-currency-denominated assets than liabilities, indicating their awareness of the exchange-rate-induced credit risk they face.”

Indeed, many of the banks lending to unhedged borrowers took measures to hedge themselves. Understandably so since it has all happened before. Recent stories of FX lending misery in various European countries are nothing but a rerun of what happened in many countries all over the world in earlier decades: i.a., events in Australia in the 1980s are like a blueprint of the European events. In Australia leaked documents unveiled that senior bankers knew full well of the risk to unhedged borrowers but they kept it to themselves.

It can also be argued that given certain conditions FX lending led to systematic lending to CESEE clients borrowing more than they would have coped with in domestic currency making FX lending a type of sub-prime lending. What now seems clear is that cases of mis-selling, unclear fees and insufficient documentation now seem to be emerging, albeit slowly, in European FX lending to unhedged borrowers.

FX lending in CESEE: to what extent and why

A striking snapshot of lending in Emerging Europe is that “local currency finance comes second,” with the exception of the Czech Republic and Poland, as Piroska Nagy pointed out in October 2010, referring to EBRD research. With under-developed financial markets in these countries banking systems there are largely dominated by foreign banks or subsidiaries of foreign banks.

This also means, as Nagy underlined, that there is an urgent need to reduce “systemic risks associated with FX lending to unhedged borrowers” as this would remove key vulnerabilities and “enhance monetary policy effectiveness.”

Although action has been taken in some of the European countries hit by FX lending, “legacy” issues remain, i.e. problems stemming from prolific FX lending in the years up to 2008 and even later. In short, FX lending is still a problem to many households and a threat to European banks, in addition to non-performing loans, i.e. loans in arrears, arising from unhedged FX lending.

The most striking mismatch in terms of banks’ behaviour is evident in the operations of the Austrian banks that have been lending in FX at home in Austria the euro country, but also abroad in the neighbouring CESEE countries. In Austria, FX loans were available to wealthy individuals who mostly hedged their FX balloon loans (i.e. a type of “interest only” loans) with insurance of some sort. Abroad however, “these loans in most cases had not been granted mostly to relatively high income households,” as somewhat euphemistically stated in the Financial Stability report by the Austrian Central Bank, OeNB in 2009.

There is plenty of anecdotal evidence to conclude that during the boom years banks were pushing FX loans to borrowers, rather than the other way around. Thus, it can be concluded that the FX lending in CESEE countries was a form of sub-prime lending, that is people who did not meet the requirements for borrowing in the domestic currency could borrow, or borrow more, in FX. This would then also explain why FX loans to unhedged borrowers did become such a major problem in these countries.

Where these loans have become a political issue FX borrowers have often been met with allegations of greed; that they were trying to gain by gambling on the FX market. In 2010 Martin Brown, economist at the SNB and two other economists published a study on “Foreign Currency Loans – Demand or Supply Driven?” They attempted to answer the question by studying loans to Bulgarian companies 2003-2007. What they discovered was i.a. that for 32% of the FX business loans issued in their sample the companies had indeed asked for local currency loan.

“Our analysis suggests that the bank lends in foreign currency, not only to less risky firms, but also when the firm requests a long-term loan and when the bank itself has more funding in euro. These results imply that foreign currency borrowing in Eastern Europe is not only driven by borrowers who try to benefit from lower interest rates but also by banks hesitant to lend long-term in local currency and eager to match the currency structure of their assets and liabilities.”

In other words, the banks had more funding in euro than in the local currency and consequently, by lending in FX (here, euro), the banks were hedging themselves in addition to distancing themselves from instable domestic conditions. A further support for this theory is FX lending in Iceland, which took off when the banks started to seek funding on international markets. (The effect on banks’ FX funding is not uncontested: further on reasons for FX lending in Europe see EBRD’s “Transition Report” 2010, Ch. 3, esp. Box 3.2.)

The Australian lesson: with clear information “…nobody in their right mind… would have gone ahead with it”

Financial deregulation began in Australia in the early 1970s. Against that background, the Australian dollar was floated in December 1983. In the years up to 1985 banks in Australia had been lending in FX, often to farmers who previously had little recourse to bank credit. However, the Australian dollar started falling in early 1985; from end of 1984 to the lowest point in July 1986 the trade-weighted index depreciated by more then a third. Consequently, the FX loans became too heavy a burden for many of the burrowers, with the usual ensuing misery: bankruptcy, loss of homes, breaking up of marriages and, in the most tragic cases, suicide.

The Australian bankers shrugged their shoulders; it had all been unforeseeable. FX borrowers who tried suing the banks lost miserably in court, unable to prove that bankers had told them the currency fluctuations would never be that severe and if it did the bank would intervene. As one judge put it: “A foreign borrowing is not itself dangerous merely because opportunities for profit, or loss, may exist.” The prevailing understanding in the justice system was that those borrowing in FX had willingly taken on a gamble where some lose, some win.

But gambling turned out to be a mistaken parallel: a gambler knows he is gambling; the FX borrowers did not know they were involved in FX gambling. The borrowers got organised, by 1989 they had formed the Foreign Currency Borrowers Association and assisted in suing the banks. The tide finally turned in favour of the borrowers and against the banks; the courts realised that unlike gamblers the borrowers had been wholly unaware of the risk because the banks had not done their duty in properly informing the FX borrowers of the risk. But by this time FX borrowers had already been suffering pain and misery for four to five years.

What changed the situation were internal documents, two letters, tabled on the first day of a case against one of the banks, Westpac. The letters, provided by a Westpac whistle-blower, John McLennan, showed that when the loan in question was issued in March 1985 the Westpac management was already well aware of the risk but said nothing to clients. Staff dealing with clients was often ignorant of the risks and did not fully understand the products they were welling. When it transpired who had provided the documents Westpac sued McLennan – a classic example of harassment whistle-blowers almost invariably suffer – but later settled with McLennan.

As a former senior manager summed it up in 1991: “Let us face it – nobody in their right mind, if they had done a proper analysis of what could happen, would have gone ahead with it.” (See here for an overview of some Australian court cases regarding FX loans).

FX borrowers of all lands, unify!

“Probably like a lot of other people (.) I felt that the banks knew what they were doing, and you know, that they could be trusted in giving you the right advice,” is how one Westpac borrower summed it up in a 1989 documentary on the Australian FX lending saga.

This misplaced trust in banks delayed action against the banks in Australia in the 1980s and in all similar sagas. However, at some point bank clients realise the banks take their care of duty towards clients lightly but are better at safeguarding own interests. As in Australia, the most effective way is setting up an association to fight the banks in a more targeted cost-efficient way.

This has now happened in many European countries hit by FX loans and devaluation. At a conference in Cyprus in early December, organised by a Cypriot solicitor Katherine Alexander-Theodotou, representatives from fifteen countries gathered to share experience and inform of state of affairs and actions taken in their countries regarding FX loans. This group is now working as an umbrella organization at a European level, has a website and aims i.a. at influencing consumer protection at European level.

Spain is part of the euro zone and yet banks in Spain have been selling FX loans. Patricia Suárez Ramírez is the president of Asuapedefin, a Spanish association of FX borrowers set up in 2009. She says that since the Swiss unpegging in January the number of Asuapedefin members has doubled. “There is an information mismatch between the banks and their clients. Given the full information, nobody in their right mind would invest all their assets in foreign currency and guarantee with their home. Banks have access to forecasts like Bloomberg and knew from early 2007 that the euro would devalue against the Swiss Franc and Japanese Yen.”

As in Australia, the first cases in most of the European countries have in general and for various reasons not been successful: judges have often not been experienced enough in financial matters; as in Australia clients lack evidence; there tends to be a bias favouring the banks and so far, only few cases have reached higher instances of the courts. However, in Europe the tide might be turning in favour of FX borrowers, thanks to an fervent Hungarian FX borrower.

The case of Árpád Kásler and the European Court of Justice

In April 2014 the European Court of Justice, ECJ, ruled on a Hungarian case, referred to it by a Hungarian Court: Árpád Kásler and his wife v OTP Jelzálogbank, ECJ C‑26/13. The Káslers had contested the bank’s charging structure, which they claimed unduly favoured the bank and also claimed the loan contract had not been clear: the contract authorised the bank to calculate the monthly instalment on the basis of the selling rate of the CHF, on which the loan was based, whereas the amount of the loan advanced was determined by the bank on the basis of the buying rate of the CHF.

After winning their case the bank appealed the judgement after which the Hungarian Court requested a preliminary ruling from the ECJ, concerning “the interpretation of Articles 4(2) and 6(1) of Council Directive 93/13/EEC of 5 April 1993 on unfair terms in consumer contracts (OJ 1993 L 95, p. 29, ‘the Directive’ or ‘Directive 93/13’).”

In its judgment the ECJ partly sided with the Káslers. It ruled that the fee structure was unjust: the bank did not, as it claimed, incur any service costs as the loan was indeed only indexed to CHF; the bank did not actually go into the market to buy CHF. The Court also ruled that it was not enough that the contract was “grammatically intelligible to the consumer” but should also be set out in such a way “that consumer is in a position to evaluate… the economic consequences” of the contract for him. Regarding the third question – what should substitute the contract if it was deemed unfair – the ECJ left it to the national court to decide on the substitute.

Following the ECJ judgement in April 2014, the Hungarian Supreme Court ruled in favour of the Káslers: the fee structure had indeed favoured the bank and was not fair, the contract was not clear enough and the loan should be linked to interest rates set by the Hungarian Central Bank. – As in the Australian cases Kásler’s fight had taken years and come at immense personal pain and pecuniary cost.

Hungarian law are not precedent-based, which meant that the effect on other similar loan contracts was not evident. In July 2014 the Hungarian Parliament decided that banks lending in FX should return the fee that the Kásler judgement had deemed unfair.

The European Banking Authority, EBS is the new European regulator. The ECJ ruling in many ways reflects what the EBA has been pointing from the time it was set up in 2011. In its advice in 2013 on good practice for responsible mortgage lending it emphasises “a comprehensive disclosure approach in foreign currency lending, for example using scenarios to illustrate the effect of interest and exchange rate movements.”

Calculated gamble v being blind-folded at the gambling table

“Since the ECJ judgment in the Kásler case, judges in Spain have started to agree with consumers from banks,” says Patricia Suárez Ramírez. So far, anecdotal evidence supports her view that the ECJ judgment in the Kásler case is, albeit slowly, determining the course of other similar cases in other EU countries.

The FX loans were clearly a risk to unhedged borrowers in the countries where these loans were prevalent. If judgements to come will be in favour of borrowers, as in ECJ C‑26/13, the banks clearly face losses: in some cases even considerable losses if the FX loans will have to be recalculated on an extensive scale, as did indeed happen in Iceland.

Voices from the financial sector are already pointing out the unfairness of demands that the banks recalculate FX loans or compensate unhedged FX borrowers. However, it seems clear that banks took a calculated gamble on FX lending to unhedged borrowers. In the best spirit of capitalism, you win some you lose some. The unfairness here does not apply to the banks but to their unhedged clients, who believed in the banks’ duty of care and who, instead of being sold a sound product, were led blind-folded to the gambling table.

*The first draft was written in July 2009; published 2010 as EBRD Working Paper.

This is the first article in a series on FX lending in Europe: the unobserved threat to FX unhedged borrowers – and European banks.The next article will be on Austrian banks, prolific FX lenders both at home and abroad, though with an intriguing difference. The series is cross-posted on Fistful of Euros.

See here an earlier article of mine on FX lending, cross-posted on Fistful of Euros and my own blog, Icelog.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

The Aurum case: media battle and a second round in Court

Today, the Icelandic Supreme Court annulled the Reykjavík District Court acquittal in the Aurum case. This means that the District Court has to start all over again on the case. Those charged are Jón Ásgeir Jóhannesson and Lárus Welding who became Glitnir’s CEO when Jóhannesson and a group of investors bought over 30% in the bank in spring 2007. Two other Glitnir employees are also charged.

At the centre of the case is a loan from Glitnir to a shelf company, FS38 to buy a share in the retailer Goldsmith, owned by Aurum Holding, from Fons, owned by Pálmi Haraldsson, a business associate of Jóhannesson. Haraldsson was i.a. a co-investor in Glitnir with Jóhannesson, where the duo were close up and intimate with the management. So much so that Welding at some point, in an email to Jóhannesson, complained that he was being treated like a branch manager and not the CEO.

The particulars of this whole loan arrangement was that after various evaluations of Goldsmith, Glitnir lent ISK6bn to FS38; it so happened that of the 6bn ISK1bn landed on Haraldsson’s account with Glitnir and an equal amount landed on Jóhannesson’s personal account.

The FS38 loan saga was already familiar from the SIC report, published in April 2010, one of many SIC’s loan sagas related to the major shareholders of the three banks. The four were charged by the Office of the Special Prosecutor. When the case came up in the District Court it was presided over by two District Court Judges the third one being a Court-appointed external expert, Sverrir Ólafsson.

In June last year the Court acquitted all four charged in the Aurum case. Soon after, it transpired that Ólafsson was the brother of Ólafur Ólafsson, at the time already sentenced by the District Court in the so-called al Thani case. Ólafur is now serving a sentence of 4 1/2 years after the Supreme Court sentenced him last January (thereby adding a year to Ólafsson’s sentence in the District Court). Foreigners always think that in Iceland everyone knows everybody, which definitely was not the case with the Ólafsson brothers – special prosecutor Ólafur Þ. Hauksson denied he had known about the relationship (and yes, Ólafsson is a very common name in Iceland and the two brothers are not at all similar) nor had the Icelandic media picked this up.

Following the revelation, Sverrir Ólafsson said in an interview with Rúv that it was inconceivable Hauksson and the OSP had not been aware of whose brother he was. According to Sverrir the fuss was only to undermine the judgement. In this interview Ólafsson used harsh words about Hauksson, seen by many as somewhat unsuited for a judge, even a lay one.

Following the District Court ruling in the Aurum case the state prosecutor (a different authority from the OSP) demanded that the judgement should be annulled because of doubt of the impartiality of one of the judges. Today, this is exactly what the Supreme Court did, which means that now the case must start anew, probably adding at least another year and probably more to the story of this case.

In addition to this the Glitnir Winding up Board has sued Jóhannesson and others for damages caused by the FS38 loan. In connection to that case, and at the demand of Glitnir, Jóhannesson’s assets were subjected to an international freezing order by a London Court in May 2010 (see here, here and here). The Glitnir case is resting until a final judgement in the criminal case; as far as is known the freezing order is still standing. However, Jóhannesson is again an active investor, i.a. in the UK but investing on behalf of his wife.

Recently, there have been articles in Icelandic on the website Vísir and in the newspaper (distributed for free) Fréttablaðið owned by 365 Media, under the ownership of Ingibjörg Pálmadóttir, wife of Jóhannesson. These articles have been insinuating lies on behalf of the Special Prosecutor regarding Ólafsson, i.e. stating that Hauksson and others at the OSP did indeed know whose brother Sverrir Ólafsson was. Earlier, the paper had also sought to sow doubt of the al Thani judgement; the sentence in one of its articles, saying that when the Courts fail the media must take over, was much noted. No doubt, Jóhannesson and his allies will fight their case ferociously, not only in the Courts but also in the media in the Jóhannesson’s sphere of influence.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

The latest re stability tax

Bjarni Benediktsson minister of finance did not answer directly when asked by Rúv if he knew beforehand that prime minister Sigmundur Davíð Gunnlaugsson. He only said that he and the prime minister were working closely together towards lifting the capital controls. He said work was ongoing to prepare Bill, expected before summer, but was not firm on a date.

He reiterated that the estates were a threat to stability and stability tax – not a concept heard until mentioned by the prime minister on Friday – was intended to do just that: preserve stability when it came to lifting capital controls. He did not want to answer exactly who would pay this tax or how but the tax would help authorities to control the process of lifting the controls. He also repeated what the prime minister said, that the estates had not put forward any useful plan for lifting controls.

The winding-up boards of the estates will no doubt beg to differ: they have put forth plans, which have not been answered.

At an open committee meeting on Monday governor of the Central Bank of Iceland Már Guðmundsson was asked about the tax. He said it could be compared to “pollution tax” – the estates were like a source of pollution within the economy and the tax was to mitigate the effect of this pollution. What exactly this Delphic utterance meant in practice he would not say.

For more on this issue see the two most recent blogs here below.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Panic politics in practice

Going on the fourth day since prime minister Sigmundur Davíð Gunnlaugsson announced stability tax, minister of finance Bjarni Benediktsson has not yet said a word on the announcement. Arriving from two weeks holiday in Florida Monday morning he did not attend the first meeting of Alþingi after the Easter break, nor did Gunnlaugsson. The two ministers are said to have spent the afternoon in meetings with Már Guðmundsson governor of the Central Bank, CBI.

My hunch is that Gunnlaugsson did not discuss his statement with Benediktsson before making the speech. The preparations of the capital controls plan-to-be have been carried out in utmost secrecy, drafts not sent in emails etc. and it certainly was not anticipated that one of the insiders, the prime minister, would then go out and announce it at a time that suited him and his party politics. Hardly a statesman-like behavior to use a party conference to make a prime-ministerial announcement of this kind. But with the prime minister getting some numbers wrong it seems he did not have the best advisers at his side in preparing for the speech.

It is also clear that the Bill Gunnlaugsson announced had not been presented earlier because the government leaders had not been able to come to an agreement on the final version. By saying that a stability tax bringing billions to the state will be presented before the end of this Alþingi Gunnlaugsson has put pressure on Benediktsson. It seems like a retaliation for the pressure Benediktsson tried to put on Gunnlaugsson last year when Benediktsson kept announcing that a liberalisation plan would be presented last year – only a much harder pressure because Gunnlaugsson did not just announce the plan but also what it actually should contain.

Vilhjálmur Bjarnason MP for Independence party said in Morgunblaðið yesterday that a tax on estates was far from international practice, would be contested in court, leading to years of court wrangling during which time the controls could not be lifted. Hörður Ægisson journalist at DV said in an interview with the webzine Eyjan that using the lifting of capital controls to make money for the state ran counter to earlier statements. Anything except dealing with foreign-owned ISK was unacceptable, according to Ægisson.

Gunnlaugsson then went a step further over the weekend when he said, in an interview to Morgunblaðið, that the billions from the stability tax would not be used but set aside, on which he and Benediktsson were in total agreement – another poisoned arrow.

So what is all this about? First of all, the stability tax is nothing like the previously discussed exit tax. An exit tax taxes capital movements. The stability tax is indeed a form of asset tax, i.e. will be levied on assets according to certain criteria. One theory is that it will be levied on assets in order to prepare for or at the time of composition of the banks’ estate. And it is to be a double digit tax.

That the advisory committee has been split on how to proceed on the tax, i.a. how to use the billions, echoes in Gunnlaugsson’s words. Of course, parking the billions goes counter to what Gunnlaugsson has been announcing. For Gunnlaugsson to claim that the two agreed on this seems like an attempt to making peace with Benediktsson after his major faux-pas in his speech.

Benediktsson was unavailable for comments yesterday. Gunnlaugsson did not want to be interviewed on Rúv. What happens now is anybody’s guess – some say this is the end of the government but as I have pointed out earlier Benediktsson is in a difficult situation. Should he swallow this or try to act? In theory, he could turn to the opposition and see if he can find some common ground there to form a new government. That would though crave a heroic force and spirit, non of which Benediktsson has shown so far. In addition, the opposition parties have been fairly lame, difficult to gauge there the energy needed for some political fireworks.

According to a Sunday Times article by Philip Aldrick there are some meetings going on between government representatives and creditors. I have not been able to ascertain that this is indeed the case but I believe that yes, there have been some meetings, even as late as last week. The winding-up boards do not seem to be involved and only a few large creditors. It may well be that there are some parties involved trying to map some common ground where negotiations could start from. So far, the government’s official line has been not to negotiate although that seems the most sensible approach for a speedy and efficient end to the misery of capital controls. Remains to be seen.

And it also remains to be seen what comes out of Gunnlaugsson’s statement and how the government will proceed. Benediktsson has been badly treated by Gunnlaugsson who, though most likely not seeing any fault with his behaviour, has not only breached the trust of his coalition party but also ventured into Benediktsson’s territory, quite apart from the substance, i.e. that the Bill had not been presented yet because there was, as yet, no final agreement on the coming plan.

Why Gunnlaugsson chose to make his announcement? Well, this was panic politics in practice: he was standing in front of a party he led to almost 25% of votes, but now standing at ca. 10% in the polls.

– – –

Gunnlaugsson speech is now available online, in Icelandic. I.a. he claims the numbers at stake for creditors in Iceland are high in international context as can be seen from Hollywood films, where $10m are a high number. An interesting insight into an apparently quite parochial mind who likes Hollywood films.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Gunnlaugsson goes solo on the abolition plan: beginning of an action plan or end of coalition?

In an “overview speech” at his party’s annual conference prime minister Sigmundur Davíð Gunnlaugsson announced today an outline of an abolition plan, short on content – only stability tax mentioned – but long on scaremongering of creditors and their wealth amassed in Iceland, with strikingly wrong numbers. From earlier statements by Bjarni Benediktsson minister of finance, whose remit the capital controls are, it is difficult to imagine he condones Gunnlaugsson’s views. Apart from whether this is a good plan or not it is worrying that the prime minister has lately been quite “statement-happy,” expressing views, which neither Benediktsson nor others have heard of until reported on in the media.

Before the Parliament’s summer recess the government will present a Bill to lift capital controls. This is what prime minister Sigmundur Davíð Gunnlaugsson leader of the Progressive party announced at the party’s annual conference Friday.

The only concrete measure Gunnlaugsson announced is “stability tax” that according to the prime minister will bring billions of Icelandic króna to the state coffers. As earlier, Gunnlaugsson emphasised the financial gain and the need to remove the new bank’s ownership from creditors. Worryingly, Gunnlaugsson presented wrong numbers and statements, which do not quite seem to make sense or at least rest on some fairly particular interpretation of reality.

From earlier statements by minister of finance Bjarni Benediktsson on capital controls it is difficult to see how Gunnlaugsson’s statements fit Benediktsson’s prerequisites of an orderly process based on classic measures, as outlined in Benediktsson’s last status report on the controls (see my take on it here). In addition, Gunnlaugsson has now taken the initiative from Benediktsson. The question is if he did at all discuss his speech with Benediktsson beforehand – allegedly, the two do not spend much time and effort communicating.

This in addition to some recent statements from Gunnlaugsson, which have not been discussed with Benediktsson or in the government. Also, there is the report by his fellow party member Frosti Sigurjónsson on monetary systems, another solo initiative by the prime minister.

With Gunnlaugsson’s latest statement there have been some speculation if Benediktsson and his party feel to stay in this coalition much longer. However, it might prove tricky for the party to leave without making it look as if they are somehow caving into creditors whereas Gunnlaugsson is gallantly fighting them.

Icelanders are slowly learning that whenever the prime minister speaks they glimpse the world according to his “Weltanschuung” – and it does not always seem to rhyme with reality.

Wrong numbers, remarkable calculations

In his speech Gunnlaugsson said, according to Icelandic media (I have so far not found a link to the speech), that most of the creditors were hedge funds that having bought the claims in a fire sale had profited quite enormously. The claims in the collapsed banks are so high, he said, that it is difficult to imagine it – as much as ISK2500bn (which being ca 1 ½ Icelandic GDP is not that hard to imagine). “Were this sum invested it would be possible to hold Olympic games, just for the interests, every four years, for eternity.”

This is wrong. The claims themselves are around ISK7000bn, the assets of the three estates are at ISK2250bn. As to the interests of this sum possibly being a sort eternity machine to finance the Olympics this hardly adds up. If we postulate that half of the assets are in cash at 1% interest rates and other assets carry 5% interest rates the annual interest rates would amount to ISK67.5bn or ISK270bn, just under $2bn, over four years. Would that be enough to finance the Olympics? The cost of the London games amounted to $14.6bn, ISK2000bn, the cost of Sochi $51bn, ISK7000bn.

This is worryingly wrong and far beyond reality. The fact that the prime minister does not know the correct numbers is bad but almost worse that he does not have advisers to enlighten him and find the correct numbers for him. Whoever tried to impress him with the Olympics parallel if clearly not fit to be an adviser on financial matters.

Tellingly, all these numbers and the Olympics calculations were diligently reported on Morgunblaðið’s front page today.

The spying conniving creditors

With all these assets (albeit a wrong number) Gunnlaugsson concluded that creditors would be prepared to go to some length to protect their assets. Who wouldn’t? he asked, considering the sums.

“It is known that most if not all larger legal firms in Iceland have worked on behalf of these parties or their representatives. It would be hard to find a PR firm, operating in Iceland that has not worked for these same parties in addition to a large number of advisers in various fields. This activity is almost frightening and it is impossible to tell how far they reach but according to recent news creditors have bought services to protect their interests in this country for ISK18bn in recent years.”

Again, there is no reference to where this number comes from but it seems farfetched, to say the very least. Further, Gunnlaugsson stated:

“We know that representatives of creditors have gathered personal information on politicians, journalists and others who have expressed views on these issues or are likely to do so. And in some cases people have been psychoanalysed in order to better understand how best to deal with them. Secret reports are written regularly in this country for creditors, which inform on how things are going in Iceland, on the politics, public debate, the financial system and so on. In one of the first reports it was stated that the greatest threats to the hedge funds reaching their goals, the main obstacle for them to do as they pleased, was called the Progressive party.”

Exactly what creditors have done to collect information in Iceland I don’t know but what the prime minister describes here is normal proceedings for doing business in a country (though the psychoanalysis might be rare though by far not unknown): they want to follow what is going on, how it affects their interests and so on. The alarmist tone is somewhat misplaced – creditors would not be pursuing their interests well if they did not keep a close eye on Iceland. It does not matter if it is Argentina, Greece of Iceland: firms want to understand the environment they operate in.

“One has to give it to these guys (creditors): they get the main facts right,” said Gunnlaugsson. – Getting the facts right is something less accurate people might try to learn from creditors.

The government’s turnaround in lifting capital controls

According to Gunnlaugsson it was a narrow escape that there were not major mistakes made in 2012 with regard to creditors. He especially thanked “our Sigurður Hannesson,” the MP banker who heads one of the party’s committees, is also on the capital controls’ advisory committee and known to be a close friend of Gunnlaugsson. – Gunnlaugsson did not clarify what heroic deeds were won in 2012; could be the decision to send the Icesave case to the EFTA Court or change in the currency controls legislation, which placed the foreign assets under the controls.

Gunnlaugsson stated that after the present government came to power there had been a real turnaround with regard to the capital controls and all earlier plans had been revised. – This work may ongoing but the only official plan in place is the plan presented by the Central Bank of Iceland, CBI, in 2011.

According to Gunnlaugsson, creditors worked diligently for having Iceland joining the European Union, EU, which would have forced Iceland to follow the bailout path of the euro-crisis countries. This would have forced Iceland to “pay all creditors in full and the whole overhang, not only at full price but at the overprice inherent in the creditors’ paper profit being financed by the Icelandic public through loans. This would have left Icelanders with the debt and no mercy shown. For this government this was always out of the question.”

I am somewhat at loss to understand the remarks about overprice etc. so I leave it to the reader to find the logic here. I am also unaware that creditors have been trying to drag Iceland into EU but they prime minister may well know more on this than mere mortals.

When the road towards the EU had been closed, stated Gunnlaugsson, the government told the representatives of the winding-up boards and the hedge funds that it could not wait any longer. Action will be taken in the following weeks and they will bring the state hundreds of billions of króna, he said.

Again, it is difficult to marry this statement with facts. Just recently, the government sent a letter to the EU, apparently intending to break off negotiations. However, the EU says nothing has changed. According to Icelandic officials briefing foreign diplomats in Iceland the letter does not materially change anything. And so on. Linking the recent moves on the EU and the government driving a harder bargain is not obvious, to say the very least.

The need to act

Gunnlaugsson claims the creditors are not putting forth any realistic solution, which now forces the government to act on lifting capital controls. The plan is to do it before the Parliament’s summer recess. – No mention here of winding-up boards sending composition drafts to the CBI without getting answers.

As often pointed out on Icelog it is clear that government advisers have for over a year been trying to come up with a plan that could suit the two coalition leaders. Tax is one of the points of disagreement: the prime minister wants to make money on the estates; Benediktsson wants to lift the capital controls according to practice in other countries.

It might be difficult to join Benediktsson’s many statements on orderly lifting to the Progressive’s money making scheme. Politically, the Independence party does not feel it owes much to the other coalition party after Benediktsson masterminded the “correction,” Gunnlaugsson’s great election promise of debt relief.

By the time the deadline for handing in new parliamentary Bills expired end of March the coalition parties had not found a common ground on important issues regarding a plan to lift capital controls. A government can always make use of exemption to get Bills into parliament but now the thorny topics are being discussed – reaching an agreement has so far eluded the government.

With his speech Gunnlaugsson might intend to bring pressure on Benediktsson – as did Benediktsson try to do, albeit unsuccessfully, last year with repeated statements on a plan by the end of the year.

The only measure announced: stability tax

According to Gunnlaugsson, with no realistic plans from creditors there is no other way for the government is now forced to launch a plan to lift credit controls before the Parliament ends. The plan is a special stability tax that will bring hundreds of billions to the state, stated Gunnlaugsson. Exactly how it will be applied is unclear but it seems to replace ideas of an exit tax.

This tax, together with other action will enable the government to lift controls without endangering financial stability. “It is unacceptable,” said Gunnlaugsson, “that the Icelandic economy is held hostage by unchanged conditions and to have ownership of the financial systems as it is now (i.e. that the two new banks, Íslandsbanki and Arion Bank are owned by creditors).” – This fits with Gunnlaugsson’s earlier ambitions of both getting money out of creditors and ownership of the two new banks.

The left government would have made “terrible mistakes” of all this, contrary to the Progressive party, which has been remarkable prescient time and again, said Gunnlaugsson:

“It is indeed remarkable how often we (i.e. Progressive party) experience that when we point out opportunities, warn against threats or urge that something is more closely explored or in a new light it is at first met with derision. Then it is fought but in the end viewed as common sense that should have been obvious to all. The main thing is that we Icelanders do not forget that for us everything is possible.”

“Pinch of butter” policies

During his years in office the prime minister has time and again made unfounded allegations and presented views he has not discussed with the government. In a recent article in Morgunblaðið MP Vilhjálmur Bjarnason pointed out how unfortunate it was when ministers thought aloud. One characteristic of the prime minister’s statements that sometimes he is not heard or seen for weeks for then suddenly to burst on the scene with views on everything.

Gunnlaugsson has accused the CBI of being engaged in politics. And he has accused ministries officials of leaking information, almost on a daily basis, he said. Neither allegations have been clarified or substantiated. He also worried about import of foreign food to Iceland because it could carry with it something that was changing the character of whole nations; he did not name it but seemed to be talking about toxoplasma, which luckily has not had this drastic effect in foreign lands.

Then there are all the “plans” Gunnlaugsson has announced without carrying them out or having sought any anchoring in the government. Just after coming into office he was going to appoint a capital controls “abolition manager.”

Most recently, Gunnlaugsson has announced plans to extend the Parliament house by a building sketched by Iceland’s most famous architect, Guðjón Samúelsson (1887-1950) – a house that only exists in a sketch from 1918, the year Denmark acknowledged Iceland’s sovereignty. Gunnlaugsson made this statement of Facebook April 1; when reported in the media it was widely thought to be April fools’ news.

Around that time, Gunnlaugsson also said he thought it was a good idea to build a new hospital – a long-running plan and matter of great debate in Iceland – by the Rúv building, thereby introducing a wholly new direction for the hospital. No previous discussion with minister of health or Landspítali management.

The Icelandic media has now found a name for these unexpected ideas of Gunnlaugsson: “smjörklípa” or “pinch of butter,” meaning that something is thrown into the debate to divert attention. Around the time Gunnlaugsson aired his most recent views one of his party member ministers had been unable to introduce a new housing policy, planned in four new bills. It will come at a great cost, is uncosted, and apparently the Independence party is wholly against it.

Another “pinch of butter”: new monetary system in Iceland?

Plans to revolutionise the Icelandic monetary system has made news abroad recently but less so in Iceland. The news spring from a new report, written at the behest of the prime minister (as I have already explained in detail in comment to FT Alphaville). In short, this report seems more of a favour to a Progressive party member than a basis for a new and revolutionary monetary system in Iceland.

It is indicative of the lackadaisical attitude to form and firm procedures that this report was written at the behest of the prime minister and not the minister of finance, who indeed has never expressed any interest for this topic and has not commented on the report.

All those who have been hyper-ventilating in excitement at this bold Icelandic experiment now starting should find some other source of excitement: this experiment has no political backing in Iceland. The Progressive party, whose following has collapsed from 25% in the 2013 election to ca. 10% in the polls, has little political credibility and force to further this cause.

Political risk: the major risk in Iceland

I have earlier pointed out that the greatest risk in Iceland is the political risk. It is intriguing that Gunnlaugsson chose to break the secrecy of the capital controls plan at a party conference, where he has to confront a total collapse in voters’ support is intriguing. His rhetoric of fights and battles against the conniving creditors and the party’s and his own earlier prescience is an important element in this respect.

With the two party leaders at loggerheads on major topics like the capital controls it is unavoidable that it will come to a confrontation at some point if the government is to take action. The outcome is far from clear.

There is great unhappiness among many of Benediktsson’s MPs, whom he incidentally has not trusted recently with cabinet seats. The general feeling is that it is the Independence party, which so far has been carrying out the policies of the coalition partner.

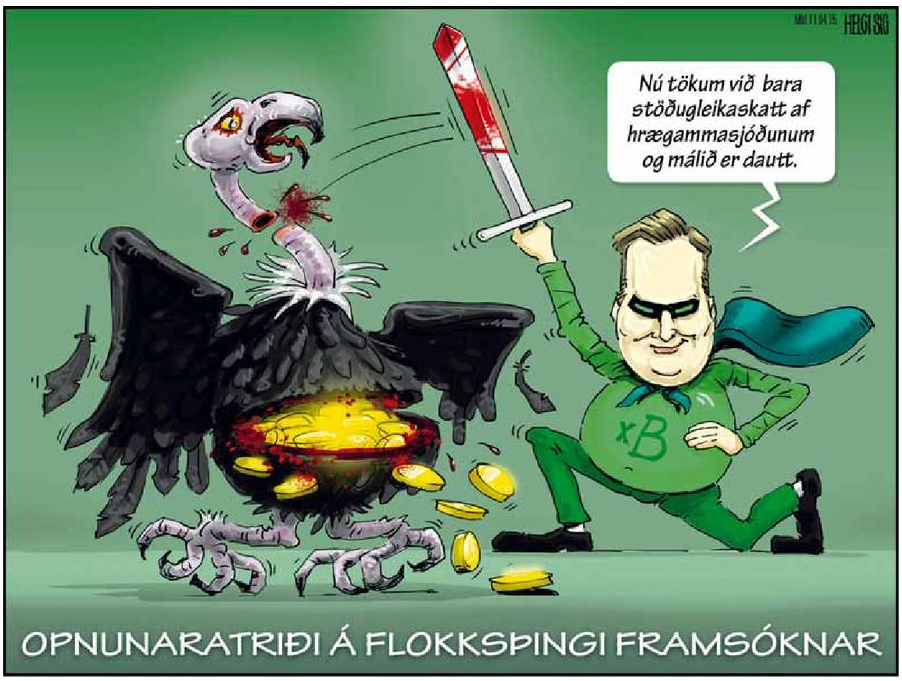

Whatever Benediktsson chooses to do he will need great political skill to steer the party through the coming months. Inaction might not help since creditors may well lose patience and explore their own possibilities, i.a. legal possibilities. If Benediktsson chooses to break away from the Progressive party he will need a clever scheme if he is not to give the coalition party and Gunnlaugsson the role that Morgunblaðið’s cartoonist has given Gunnlaugsson after his speech on Friday:

“Now we just put stability tax on the vulture funds and that will kill the problem”

“Now we just put stability tax on the vulture funds and that will kill the problem”

– – – –

Update: minister of finance Bjarni Benediktsson has not yet made himself available to the Icelandic media on his view regarding stability tax. Some members of the opposition have expressed surprise that there is now talk of stability tax instead of the earlier much discussed exit tax. Guðmundur Steingrímsson leader of Bright Future pointed out both the legal risk and risk to the economy were this plan to be pursued.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.