Archive for April, 2010

The ongoing collapse

Now, eighteen months after the collapse of the three banks – Kaupthing, Landsbanki and Glitnir – in October 2008 it’s clear that their collapse wasn’t an event but a process that hasn’t yet come to an end. A case in point is the Icelandic system of building societies, ‘sparisjóðir.’ Iceland had a strong system of building societies, similar to the German and Scandinavian ‘Sparkasse.’ Last week, two building societies were taken over by the state. Out of ca twenty societies a decade ago, only two are now left as independent institutions. The rest has either been taken over by the state or merged with one of the banks. Sadly, a financial system, closely linked to communities around the country, has been wiped out. The loss of this backbone of the local economy will, no doubt, make it much more difficult for small businesses all over the country to get financial service tailored to their needs.

The building societies, owned by locals, were run like cooperatives. The members owned what they put into the society and got a dividend of this part only. In 2000 these owners owned 15% of the societies’ equity. In 2002, laws on building societies were changed, enabling the owners to sell their part on the market. From this time the societies were allowed to become listed companies though only one of them eventually did, in 2007 as the tide of easy money was turning.

These changes were made around the time when the banks were privatized. In the following years the banks and their biggest shareholders sought to influence the building societies in their ever-greater need for money, manipulating their managements in the interest of the banks. Many building societies turned into hedge funds gambling with shares in the banks and companies like Exista and FL Group. At a closer look, the profits of the building societies didn’t stem from the banking activities but from shares. The building societies turned into satellites of the three banks, eventually doing a lot of repo loans with the Central Bank as the credit crunch struck.

Together, the building societies owned a bank, Icebank, that threw itself head on into unsustainable investments, i.a. some of the most deranged property projects abroad. One of them was a redevelopment of a hotel in Florida, Longkey, where Icebank eventually lost $8,5m. The key person was an Icelandic investor, Karl Wernersson, who was a principal shareholder in Glitnir before he sold to Jon Asgeir Johannesson. Clearly, fast-talking foreign developers who promised riches and delivered nothing led the Icelandic investors badly astray.

Around Christmas I spoke to a manager from one of the two building societies still standing – one is in the West of Iceland, the other in the North. He complained that competition was now tough since his society was competing against state-funded building societies. As to why his fund was still standing he said that the fund had mostly steered clear of investing in shares. And he and his colleagues had stayed away from making business with people from Reykjavik. ‘At one point,’ he said, ‘we had some clients from Reykjavik but our experience of making business with them wasn’t good.’ – Sometimes, it pays to stay close to one’s roots.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Goldman Sachs: who was allowed to profit and who to lose?

From the Icelandic perspective SEC’s charges against Goldman Sachs raise interesting questions. In the Icelandic banks some shareholders and companies were allowed to make huge profits and to borrow exorbitant amount of money against the interests of other shareholders and other clients.

The charges against Goldman Sachs indicate that some clients and the bank itself profited from Abacus, the fund at the core of the charges. I would be interested in knowing who exactly was allowed to make profit and who was allowed to lose, also in possibly similar investment schemes. The answer to this question would go a long way to map the power sphere of Goldman Sachs.

PS For those who want to understand what SEC charges agains Goldman Sachs are about two articles by Steve Randy Waldman clarify the case, even to the layman; Goldman-plated excuses; L’affair Goldman in price/information terms. Waldman blogs at Interfluidity.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

The Icelandic banks: a case of a gigantic market manipulation?

As the crisis hit in 2007 the Icelandic banks could not make use of margin calls because their largest debtors seriously put the banks’ position at risk – a typical example of what happens when the power in a bank’s client relation is reversed: the bank loses the stronghold on a client that has borrowed far beyond all sensible and justifiable limits. I’ve already pointed out the similarities to corrupt Italian banks. But the banks were also seriously hampered in making margin calls among smaller clients who had pledged the banks’ own shares.

In reality, many of the loans against the banks’ shares, particularly prevalent at Kaupthing (and not only towards the end) were no ordinary loans. It’s more precise to describe these transactions as ‘parking’ – the banks, especially Kaupthing, didn’t want just whoever to own shares so they ‘parked’ the shares with friendly partners. The banks wanted to control the shares, originally perhaps to avoid a hostile take-over, later to keep the share price at a level that the bank itself found satisfactory.

At Kaupthing, many employees borrowed from the bank to buy Kauphting shares with the shares as collateral. These sums were often far beyond what the employees’ salaries could reasonably justify. There are indications that the bank used pressure to induce the staff to make use of this offer that the bank said were ‘risk-free.’ In late 2002, as the share-price started to fall the bank couldn’t make margin calls on these loans thus leaving the employees who mostly didn’t have their shares in a limited liabilities holding company in a limbo. Just before the bank collapsed these employees were released of their responsibility for these loans. The legal wrangle on that decision is still unsolved. On the whole, these loans appear a horribly cynical action by the bank’s management that literally gambled with the employees’ future – a modern version of slavery.

This share ‘parking’ and other means the banks apparently used to keep up their share price is now under investigation in Iceland as market manipulation. It seems these tricks might have started well before the collapse in October 2008. If this proves to be the case investors and bond holders might well see a case for legal action against those responsible. At least one of the banks’ large creditors is preparing a case on these grounds.

It’s also interesting that the Serious Fraud Office is investigating Kaupthing with a team of eleven people. A possible market manipulation is most likely a part of that investigation.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

The ‘home-knitted’ crisis

‘How far are you in reading the report?’ is a question that everyone asks in Iceland these days. The report in question is of course the report of the Investigative Commission, published April 12. The 2600 pages offer a lot of information to mull over regarding the banks and the public sector, including the Financial Services Authority, FME and the Central Bank.

One of the most important findings is that the banks didn’t fail because of evil foreigners – hedge funds, the UK Treasury or the FSA or any other foreign force. The banks collapsed because they were allowed to grow too quickly. In addition, there were some serious anomalies within the banks: the main shareholders used ‘their’ banks as their personal ‘piggy-banks’, the same small clique borrowed from all the banks and the banks made use of cross-financing to finance their own shares and shares of the other banks.

The report shows clearly that the banks’ principal shareholders were also the banks’ largest borrowers. At Kaupthing, the second largest debtor was Exista, a listed company ruled by Agust and Lydur Gudmundsson. Robert Tchenguiz had been on the board of Exista since early 2007 and was, as the bank collapsed, the bank’s largest debtor, with a debt of ISK200bn, ca €1,7bn, which also makes him the largest single debtor in Iceland. – In Iceland, foreigners with strong ties to Iceland are called ‘Íslandsvinir,’ ‘friends of Iceland. Tchenguiz’ strong ties to Iceland add a new meaning to the word ‘Íslandsvinur.’ – Another large debtor in Kauphing and a large shareholder is Olafur Olafsson who still owns the shipping company Samskip.

Bjorgolfur Thor Bjorgolfsson and his father, Bjorgolfur Gudmundsson, were the main shareholders at Landsbanki. Bjorgolfsson was also the main shareholder in the investmentbank Straumur. In total, father and son owe Landsbanki over ISK200bn which is more than Landbanki’s entire equity. At Straumur father and son are also the bank’s largest debtors.

At Glitnir, the largest borrower was Baugur and related companies/investors. Jon Asgeir Johannesson, his wife Ingibjorg Palmadottir (who miraculously still owns the 101 Hotel in Reykjavik), his father Johannes Jonsson as well as his mother in total owed ISK250bn to the banks. Related to Johannesson is his business partner for many years Palmi Haraldsson. From 1998 Johannesson had been trying to become a principal shareholder in an Icelandic bank but it wasn’t until mid-year 2007 that he and Haraldsson finally got hold of a bank, Glitnir. Their borrowing, already high, accelerated. As the bank collapsed Baugur and related companies owed more than ISK250bn, equal to 70% of the bank’s equity base.

In addition to using the banks as their personal piggy-banks, the largest shareholders seem to have swayed the investments of the banks’ money market funds towards their own companies and the banks themselves. Consequently, the funds lost heavily. The Icelandic money market funds never operated as normal MMFs, were i.a. not independently rated. In addition, the funds were marketed as ‘as save as current accounts, only with better interests.’

The management of the banks’ MMFs is a chapter in itself in this sad story. In a Glitnir fund a politician from the Independence Party was on the board. Whether it mattered in the end is an open question but the state did put money into the funds in order to minimize the losses – an action that still raises questions as to political influence in the collapse and why these funds were helped thereby helping many individuals, typically middle class professionals.

There is no doubt that quite a number of court cases will arise from the collapse of the Icelandic banks. The other day, I was walking towards the pond, ‘Tjornin,’ in the heart of Reykjavik when I saw a firework exploding over the hill beyond the pond. It reminded me that when I was in Naples in the summer of 2007 there were bursts of fireworks almost every day. A Neapolitan friend explained that it was customary to celebrate the release of a prisoner with fireworks – and that was happening all the time because of an amnesty to diminish the prison population. Since no one has yet been put in prison because of the banks this single firework can’t have had anything to do with a prison sentence. Perhaps Icelanders, who are the most firework-happy population on earth on New-years eve, will one day learn to use fireworks to express relief when those responsible for the banks’ collapse will be convicted.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Eyjafjallajokull: blinking into the crater

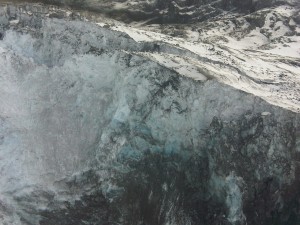

I had the opportunity today, at 7pm, to fly in a helicopter up to Eyjafjallajokull to visit the crater that’s cancelling flights all over Europe. The trip to the crater took about 10 mins. As we came flying up the volcano we saw directly into the crater, the ash, fumes and steam bulging up.

Just in front there was this pristine white tip of snow.

Close up, there was ash over the glacier, everything black and grey except the blue sky beyond.

Flying back, we glided down the glacier, following a crevice formed by floods of warm water that melted as the eruption started. The water ran under the glacier causing parts of it to collapse, forming crevices as if the ice cap had been torn apart.

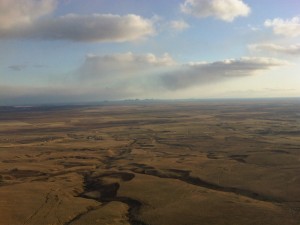

When we came down to the flatland the Vestmanna Islands seemed only a stone’s throw away, resting on the ocean under the tip of the ash spreading out over the Atlantic. Heimaey, the biggest island, erupted in 1973 – the island was evacuated over night and no one lived there for the best part of the year. Those who returned say that live wasn’t the same afterwards. Farthest to the right is Surtsey, formed on the ocean in an eruption 1963-67 that began underwater. As you can see the surface of the earth is cut and torn by rivers and floods.

Just before landing by Hotel Ranga with the plume out by the horizon.

This is the view I had with my dinner at Hotel Ranga, at around 8.50pm. Earlier, the volcano drew a deep breath with only white steam rising up from the crater. At this time, the lightening that plays around in the steam all the time was visible from time to time. – I sent the photo to someone who is in Germany and who had planned to fly back to London Thursday evening. He remarked that this eruption certainly didn’t look like forces of nature strong enough to bring halt all flights in Europe.

And that’s true. Here, so close to the volcano, life goes on as if nothing had happened. So far, it’s not a catastrophe – but the outlooks is different if this goes on for long. It will make life difficult i.a. for the farmers living right under the plume where the ash falls. The earth there is covered with what looks like pale grey snow.

And this is the tip of the plume lit up by the setting sun – like a tongue stuck out at Europe, the river Ranga floating by. A serene evening under the volcano.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Under the volcano – the source of the ash

Little did I know some weeks ago when I booked a room at Hotel Ranga that I would have an eruption outside my window. The hotel is ca 20 km from Eyjafjallajokull, the glacier now erupting and putting Europe to a standstill.

I left Reykjavik this morning. I didn’t realise it at the time but the top of some clouds, visible from Reykjavik, were indeed the top of the plume. Already on the heath East of Reykjavik the glacier and the plume hovering over it were visible. Below are photos that I took as I approached the volcano.

Eyjafjallajokull seen from Selfoss, ca 50 km from the volcano.

The horses didn’t seem to mind the volcano ca 20 km away. It’s a cold day today but the air clear and the view spectacular. The volcano is ca 1500m high, the steam and ash around 8km.

This is the view from the hotel. Around 4pm the eruption stopped…

… but only while the volcano took a deep breath: ca 20 min later it was spewing ash and steam again. The dark blanket to the right is the plume of ash that drifts over the sand South of the glacier and then out over the Atlantic, over to Scotland, England and down the continent.

This is only a small eruption on Icelandic scale – and yet it’s powerful enough to halt the life of millions of people all over the world. A friend in Paris was going to a concert tonight but the concert was cancelled because the orchestra from Lisbon hadn’t been able to fly to Paris. Another friend is stuck in Cincinnati, can’t get back to England. But here, close up to the volcano all is peaceful, the view is spectacular and it’s as if nothing had happened except nature following its course.

The word going around in Iceland now is that the last wish of the Icelandic Financial System was for its ashes to be spread out over Europe…

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Eruption – report – eruption

That’s the cards that nature has dealt Iceland recently: first there was a small neat eruption at Fimmvorduhals. As it was residing on Monday out came the report of the Investigative Commission and shook the country, leaving us with 2000 pages to read and learn from on how the banks and their principal shareholders used them to line their own investments watched over by at first enthralled and then bewildered politicians and regulators.

Yesterday, this little neat eruption was declared extinguished – but early this morning water started to flood down from Eyjafjallajokull, a glacier close by. Now it’s clear that there is an eruption under the ice cap; it has already melted a hole the cap, with steam now rising several km up into the air.

The glacier is part of a mountain ridge in the South of Iceland. South of the glacier, down to the Atlantic there are sands, now partly flooded by the melted ice. Floods of this type are called ‘leap’ in Icelandic, the water leaps down from the glacier. Quite a spectacle that you can see here!

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

A triple-A failure: Iceland and the rating companies

The report of the Investigative Commission, ICR, gives a clear and detailed insight into the running of the three Icelandic banks – Kaupthing, Landsbanki og Glitnir – compareable to the insight into Lehman in Anton Valukas’ recent report. The Icelandic insight is far from flattering. Much of it should have been obvious to the actors in international markets, i.a. also the credit rating agencies, yet again raising questions about the CRAs and their methods.

As Mark Flannery points out in his article in the ICR the banks’ exponential growth and expanding operations abroad drew the attention of the international financial sector. Their growth was remarkable, ‘at least double that of the other Nordic banks. Put another way, in the same markets and under the same world financial conditions, the Icelandic banks had found a way to earn substantially more than their more experienced, overseas com- petitors. Moreover, these higher earnings were attained with a higher cost of funds, because the Icelandic banks relied more heavily on relatively expensive wholesale funding.’

Was there any reason to believe that the newcomers knew something the others didn’t know? That was often the explanation in Iceland: that the Icelandic bankers were far more clever and savvy than their competitors.

Against the apparent success stood two potential warning signs: “surprisingly low reported loan problems and a growing (but uncertain) reliance on shares to collateralize their loans.”

After the rapid expansion in 2003-05 the Icelandic banking success started to attract the attention and curiosity of foreign banks and CRAs. Their reports contained a barrage of criticism. Danske Bank’s report stung the Icelanders’ national pride and Lars Christensen, the bank’s chief economist, became the most unpopular person in Iceland.

These reports identified four problematic aspects of the Icelandic banking system: lending to related entities, questionable credit quality, funding and the expanding banking sector compared to country’s economy and the central bank’s foreign reserves.

How did the Icelandic banks and Icelandic authorities meet this criticism that led to the Icelandic mini-crisis in 2006? In just the same way as criticism was met in 2008: by changes directed toward style instead of substance, flat denial and xenophobic accusations of foreigners’ malign intents.

Kaupthing did i.a., to some degree, severe its incestuous relationship with Exista, the bank’s largest shareholder. In spite of the responses FME, the Icelandic financial services authorities, concluded, among other things, that the banks didn’t properly recognise relationships among entities they lent to. The ICR clearly outlines the banks’ rambling and inexact classification of related entities.

The Icelandic window dressing satisfied the rating companies. In February 2007 Moody’s improved the three banks’ credit rating and was, quite remarkably, widely criticised. Yet, nothing changed for the worse for the Icelandic banks until well into 2008.

The three banks did, like Lehman, direct much of its efforts at appeasing the CRAs, instead of addressing their weaknesses – and the CRAs seem to have been far too easy to fool. The CRAs have had a lot of bashing lately though possibly not enough. The Icelandic banks are just one further inglorious example of the CRAs’ failure.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

The report finds it way through Reykjavík

Here you see the report, in the box, carried out of the press conference yesterday morning by my colleague Thordis Arnljotsdottir. As you can see it’s a heavy burden, yet carried with a smile!

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

The report – in English

Substantial parts of the report of the Investigative Commission will be published in English. Due to technical glitches only a part of the translation is in place so far but more will come tomorrow. On this same page there are also transparencies in English used at the press conference today and the conclusions of the Working Group on Ethics working alongside the Investigative Commission.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.