Archive for November, 2012

Landsbanki Luxembourg clients raise complaints in Luxembourg – updated with a video

At a press conference today, a group of almost 200 clients of Landsbanki Luxembourg in Spain and France raised complaints against the bank, because of its equity release lons and its administrator, Yvette Hamilius, for not investigating what went on in the bank prior to its default. A Brussel-based lawyer, Bernard Maingain, discussed the complaints, most of which Icelog has already written about earlier.

The action taken by the group is both aimed at the Landsbanki Luxembourg operations and the administrator. As Maingain pointed out today, the Landsbanki operations raise many questions – such as if the equity release loans were put together in such a way that they would never make the money promised, if they were mis-sold, if Landsbanki really had the license to operate in Spain and France. It is part of an administrator’s duty to investigate any possible irregularities prior to the failure of the company administrated.

Tomorrow, these claims will be presented in Luxembourg. This is just the beginning of a case, which no doubt will run for a while. The interesting thing is that here Luxembourg is being challenged on its supervision of its gigantic banking sector – the lifeblood of this tiny Duchy. But as representatives of the group said today, they are seeking nothing but justice from Luxembourg.

It will be interesting to see how easy it is to seek justice in a bank-related case in a country utterly and completely at the mercy of its banking sector.

*Here is a video link, in English but mostly in French, on the Landsbanki Luxembourg action, made last week during the press conference in Brussels, with interviews with some Landsbanki clients.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Le bras de fer between the Eurogroup and the IMF – or more precisely between Schäuble and Lagarde

Le bras de fer is how the Belgian newspaper Le Soir described the battle between the Eurogroup and the IMF and it has been going on for weeks and months. Tuesday morning, talking to someone who was at the meeting, I got some colours to this battle story.

When Jean-Claude Juncker opened the meeting he said that those present were not leaving until an agreement had been found. And from the IMF point of view it had to be a realistic and sustainable agreement.

Mainly, it was the German minister of finance Wolfgang Schäuble and Christine Lagarde director of the IMF, who discussed the issues. The others were onlookers to this discussion. There were three breaks during the meeting when these two parties had to calculate different option. The Dutch and the Finnish ministers, who had earlier together with their German colleague expressed worries and discontent with further financial support to Greece, did not say much. The two sensed Schäuble arrived with the purpose on finding a compromise.

The Eurogroup met well prepared for negotiating with the IMF. During its teleconference this weekend, where Lagarde wasn’t on the line, the Eurogroup thoroughly discussed her arguments and how to encounter them.

Monday it was reported that before the Monday meeting Samaras had told Juncker that if an agreement would not be reached the Greek coalition Government would collapse. Both parties denied the story. However, I’m told that Juncker made it clear that the Greek Government faced great difficulties if yet another inconclusive meeting would come to an end. – The Greeks are now essentially tied to a ten year plan, well beyond any government’s lifespan.

As to the agreement, have some lines been crossed, which have not been crossed before? Yes, here it counts to observe what the Eurogroup has done, not what they say. No one in the Eurogroup is publicly uttering these three most fearful words – Official Sector Involvement, meaning a haircut or write-downs on loans from the states and official institutions – but OSI has now happened: the official sector – ie the EU member states, the IMF and the ECB – will not get paid on time and in full what they lent to Greece.

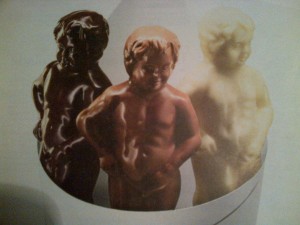

The Official Sector will make losses on loans to Greece. That is the naked truth, as naked as the Manekin Pis but not as sweet as this version:

Various classic measures are used to bring down Greece’s debt to GDP. Interest rates on loans to Greece are lowered by 100bp, maturities extended by 15 years and Greece gets an interest free grace period of 10 years. The IMF had to sway from its aim of 120% debt to GDP in 2020: the aim for 2020 is now 124% but “substantially lower than 110%” in 2022.

The Greek debt buy-back seems the least clear action. Juncker said the Greeks were considering it, Lagarde said it would definitely happen but she was noticeably tongue-tied when asked about it, answering that the less there is said about it the better. This is what the statement says: “The Eurogroup was informed that Greece is considering certain debt reduction measures in the near future, which may involve public debt tender purchases of the various categories of sovereign obligations. If this is the route chosen, any tender or exchange prices are expected to be no higher than those at the close on Friday, 23 November 2012.”

The fund, which collects money to repay loans, has been a soar issue for the Greeks. The Germans, wanting to guarantee that the fund would be used for nothing except the designated purpose, almost seemed to be insisting on an escrow account, which ia Züd-Deutsche Zeitung felt was offensive to the Greeks. Here is what the agreement stipulates on this issue: “Greece has also significantly strengthened the segregated account for debt servicing. Greece will transfer all privatizations revenues, the targeted primary surpluses as well as 30% of the excess primary surplus to this account, to meet debt service payment on a quarterly forward-looking basis. Greece will also increase transparency and provide full ex ante and ex post information to the EFSF/ESM on transactions on the segregated account.” – The word is now “segregated,” not an outright escrow account.

In addition, the Greek Government is subjected to a demanding (or heavy-handed) monitoring. I’m told that at the Eurogroup meeting last night, the Greeks were told in no uncertain terms that should they stray from the narrow path of sustainability, disgruntled nations such as the Finns and the Dutch would be quick to declare an end to the Greek programme (but ugh, will they risk a Greek default and a euro collapse? Another story.)

Is the Monday agreement the final plan to put Greece on a sustainable path? As an economist explained to me today: it’s much more realistic than anything done before. Antonis Samaras’ Government has really worked miracles, compared to before. But questions remain, as is clearly spelled out in this paper by the Bruegel economist Zsolt Darvas. – Earlier, agreements have fallen apart when unclear wording was in the end interpreted differently by different parties. There is also some scope for that happening here but if the Eurogroup’s sincere will is in this agreement it will put an end to the Greek debt issue.

Being indebted means losing independence – that is the bitter truth – and it counts both for individuals and nations. The Greeks have been living with that painful fact for three years now. Now, they are hopefully out of their three-year limbo of uncertainty and can work more constructively on rebuilding their society.

The question I’ve heard echoing today here in Brussels is what the new agreement on Greece – OSI and everything – means for the other two bailout countries, Portugal and Ireland. The future of Portugal and Ireland may look decidedly rosier if the Greek solution is calculated into their economy forecast – but the harsh terms and supervision, bordering on encroaching on Greek sovereignty, must make the Greek solution most unappealing to these two countries. Bailouts don’t come in one size fits all – for those as badly indebted as the Greeks are, with as woefully dysfunctional public sector and plain corruption, the harsh measures correspond to the harsh realities of Greece.

*Here is an article from the English version on Kathimerini, a Greek newspaper, on the Greek political prospects post-agreement.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Shareholders of the world, unite!

The Adoboli case brings a lesson for shareholders – but for how long are shareholders going to let banks squander their capital in an Alice-in-Wonderland topsy turvy banking

It’s difficult to find any sympathy for Kweko Adoboli, the 32 year older UBS trader who this week was sentenced to seven years in prison for causing the bank a loss of $2.3bn – the largest rogue trading loss in the UK. It’s rather sickening to hear of a 30 year old, earning £360.000 in 2010, up from £93.000 in 2007, spending £123.000 on betting and being so short of money in between that he had to turn to payday lenders. But he’s hardly the only young banker to seek some kick in spread betting and to squander his money away – though his reckless way of hiding losses and lying about it puts him in the exclusive category of rogue traders, such as the recently sentenced Jerome Kerviel causing SocGen a loff of $7.2bn – on an international level by far the highest rogue loss so far.

However shocking Adoboli’s behaviour is his case raises some mind-boggling questions about UBS’s own workings. In August 2011, Adoboli’s losses had peaked at $11.8bn – yes, can you imagine: that’s almost the entire Icelandic GDP. At that point the oblivious accounting systems and supervisors at the bank deemed the bank’s risk exposure was $2.3… not billion but million. By mid September 2011, the loss had come down to “only” $2.3bn, Adoboli finally lost his cool, sent this now so famous email telling his superiors he was sorry for the losses and resigned.

True, USB is a big bank and even a small country’s GDP is insignificant compared to its balance sheet. End of September last year its total assets amounted to $1.8t. But it still is rather incomprehensible that Adoboli could have such sums as $11.8bn sloshing around out of view from the bank’s supervision. According to the Daily Telegraph, UBS will now have to pay a record fine, imposed on it by the FSA – the FT guesses the fine might run up to £50m – the largest such fine ever in the UK – for the management oversight that led to the loss of the $2.3bn. The FSA and the Swiss regulator, Finma, have been investigating UBS, because of the Adoboli case, since spring this year.

If this case ends with a fine for the bank it’s yet another example of management oversight, which the managers can just load onto the bank. Yes, some managers have indeed resigned, but they walk quietly into the night, no questions asked and they seem to keep what they have earned from their unsatisfactory work.

What I also find absolutely astounding is another piece of evidence that came out during the trial: in 2007, Adoboli, then aged 27, and his co-worker, later his superior, John Hughes, 24 at the time, were left to manage a $50bn portfolio – that’s now just about three times the Icelandic GDP. On this Adoboli said (subscription): “Our book was massive – a tiny mistake could lead to huge losses. We were two kids trying to figure how this could work. We were losing so much money it was mental.” – Isn’t it a bit mental of UBS to put two kids in charge of a portfolio three times the size of a small country’s GDP?

An internal UBS review in 2008 on the bank’s subprime losses came to the damning conclusion that at a senior level UBS investment bank the focus was on maximising revenue and too little focus on the risk. Now, what did UBS do? Did it reign in the investment bank? No, on the contrary – it expanded fixed income and equity trading. Intoxicated by this spirit, Adoboli ended by blowing up his life and a lot else: UBS is now re-organising the bank, i.a. with people losing their jobs.

If banks such as UBS didn’t learn from the subprime saga, upheavals and losses on 2008 what could teach it a lesson? The Aboboli saga?

Where are shareholders in all of this? Are they for eternity just accepting one wave after the other of losses and fines accrued by the guardians of the shareholder values and assets? Capitalism is based on… capital. In theory, the capital owners are those who take risk and reap reward. In the Alice-in-Wonderland banking of today things are topsy turvy and the old rules of capitalism have been obliterated. Now it’s the capital owners, the shareholders, who reap the losses (or the state, when things go completely awry) but the bankers – no matter the oversight, such as not noticing $11.8bn losses or letting kids fool around with GDP-sized portfolios – are more or less sheltered by cleverly constructed pay packages.

On whose side are regulators? On the side of the capital owners or its guardians? And what about the politicians? Has everyone completely lost sight of the fundamentals of capitalism? The world needs capital put to good use, not capital squandered away by careless bank managers who don’t understand or don’t examine what’s going on in their institutions. And the world needs intellectually curious and plain curious central bankers and regulators.

Shareholders of the world, follow Marx’s advice and unite – against the squanderers of your capital!

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

FT’s front page today dedicated to fraud cases

Interesting to observe the front page of the FT today.

The three main items – Hewlett Packard taking a hit, the picture of the trader Kweku Adoboli, sentenced yesterday to seven years in prison and a US insider trading case – all refer to fraud cases.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Ireland and Iceland – better to let fail or to bail out?

When it comes to bailing out banks Ireland and Iceland chose different paths. Interestingly, there are those who see the two countries as a test of whether it is better to let the bank system fail – or bail it out. That is at least how Jim Leaviss, head of retail fixed interest at M&G Investments is quoted as saying in an article on Ireland in the FT (subscription needed). “Iceland and Ireland were a test of whether it was better to let your bank system collapse or bail it out. So far it is not clear which was best. Irish bond yields have fallen a lot but that was skewed by the ECB’s actions.”

On the basic indicators, growth and unemployment Iceland, is doing much better.

Unemployment: Iceland: 4.5% – Ireland: 15.1%

Growth 2011/2012 (forecast): Iceland: 2.6% / 2.5% – Ireland 0.7% / 0.9%

The Irish ray of light these last days is the notch up by Fitch: from negative to stable (for those who still take any notice of the big rating firms), at BBB+.

As I’ve pointed out earlier it is however a myth that Iceland didn’t bail out its banks. It did bail out some smaller financial institutions to quite a cost but it didn’t bail out its three big banks – Kaupthing, Glitnir and Landsbanki – in October 2008. From early 2008, the Government (a coalition of the Independence Party, conservative and the social democrats, who now lead the Government) and the Central Bank did try to get loans from all and sundry to prepare for this eventuality – it did get a credit swap from the Scandinavian central banks of €1.5bn – but not enough to save the banks. The reality was that the banks couldn’t be saved.

The Icelandic Government has posted what amounts to 20-25% of GDP in bailing out – or trying to bail out – various other financial institutions and one insurance company. Some of this might be recovered later on but some of it is already lost. It is therefor not correct to say there were no bailouts in Iceland and therefore Iceland is not a crystal clear case of no bailouts vs bailouts.

As I have also pointed out earlier, the recovery in Iceland can partly be attributed to wide-reaching write-downs, both for companies and individuals and for changes in the bankruptcy law. All of this helps but it is over-simplification to say that there is any one policy that has made all the difference.

Ireland and Iceland have been very much in my mind for the last two days. I’ve been immersed in all things Irish, attending a conference at Goldsmiths University on the Future State of Ireland, brilliantly organized by Derval Tubridy senior lecturer in English Literature and Visual Culture at Goldsmiths. With illuminating lecturers like columnist and adviser to the EU on corruption Elaine Byrne, Roy Foster professor of Irish History at Oxford, Luke Gibbons professor of Irish Literary and Cultural Studies at National University of Ireland and journalist and writer Fintan O’Toole, this was bound to be an interesting event.

When I first saw the programme for the conference (which Elaine drew my attention to; thanks Elaine) and saw there were some artists involved my first thought was that this was most likely going to be a pretty fluffy event. It turned out to be the contrary – a very dense event with a fascinating insight into Irish History, culture and the Irish psyche.

The artist duo (Gareth) Kennedy (Sarah) Browne showed a video of ‘How Capital Moves’ – taking inspiration from an American company moving from Ireland to Poland. The story of this move is told from several aspects by creating several characters, all lovingly portrayed by one Polish actor. It’s funny and witty but also sadly true, based on words from people working for this company.

The photographer Anthony Haughey has been photographing the Irish and their surroundings for over 20 years, immigrants in this country of emigrants, as well as looking at parallel stories in other nations. His light is the living light caught by long exposures during the night. This profound realism – real as it gets – turns into strangely surreal scenes. The almost disturbingly beautiful photos reveal tension and troubled lives – portraying at the same time striking, still images and strong stories.

Foster’s stories of Irish radicals in the early 20th century seemed to indicate that something is lost in modern Ireland. Where is the radicalism now? Yet, listening to O’Toole and Byrne there doesn’t seem to be any lack of radical thought among journalists and columnists – and interestingly, Jim Clarke at Trinity College pointed out that the tabloids, though conservative in many ways, have been better at portraying people’s anger and disgust, than others.

There is one thing that Ireland has and not Iceland: a strong diaspora. That enriches the debate since it is easier being an outsider looking inside. Ireland is a small country where people speak carefully because everything and everybody is connected. A journalist who in the 1970s spoke of politicians taking bribes, proven right 40 years later, was at the time ostracized and forced to emigrate.

“Shame” and “blame” were two words that ran through the debate. For foreigners it’s easy to forget the other great power in Ireland, next to the state – the Catholic Church. The Irish have not only been thrown into economic turmoil, seeing the political class fail – but also seen grotesque moral failure and criminal child-abuse exposed in the church. Interesting times for the Irish – as was so strongly born out at the conference.

What the Irish still lack is a comprehensive overview of the collapse of their banks. To my mind, the Irish still have only a sporadic evidence of how they have been governed this last fateful decade before their main banks collapsed. The feeling in Ireland is that they do know it all. Before the SIC report was published in April 2010, Icelanders thought the same. The report showed that things had been much worse than even the most pessimistic thought: a complete failure of politicians, regulators, the Central Bank, the business “elite” – and of course the private banks, where bank managers are now being charged by the Special Prosecutor and sued by the three banks’ Winding-up boards. – In terms of legal action against bankers there is peculiarly little happening in Ireland.

It’s difficult to say which of the two countries will fare better. I still believe it’s been wrong for European governments to save failed banks. In Iceland, it was a relatively easy decision to take – there was no alternative regarding to the three big banks. The fact that the creditors were foreign financial institutions – mainly German banks – made it easier, both politically and financially.

Interestingly, it was the same with the Irish banks. Also there, the creditors were mainly foreign and yes, mainly German. But the sums in Ireland were much bigger – and the European Central Bank and the Germans weren’t happy to see banks fail in the euro zone: the ECB because of principles and euro pride; the Germans because German banks were at risk. The Germans are rather sanctimonious about their banks – after all, they are still standing. But the story is that German banks were prudent at home but wrecked havoc abroad – the German banks have been like teenagers who are model kids at home but cut up the furniture and paintings on the walls when they go partying out of their parents’ sight.

As has later become evident, the troika treatment of Ireland in November 2010 set the example of private bank debt migrating to the state, turning the state into an unsustainable borrower – as has now happened in Greece, Portugal and Cyprus, with Spain fiercely resisting to pick up that lethal same burden.

For every imprudent borrower there is a risk-blind lender. With the one-notch up on the Irish rating scale some will hope that the example made of Ireland will turn out to be the good example. There are voices in Ireland saying it is just not fair for the state – and the taxpayers – to be paying the privately accrued debt. It is painful to see the Irish struggling with the debt, which was so recklessly showered over them.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Hvitsstadir, Kaupthing managers and a tale of cosy relationships

Shortly after the collapse of the major part of Icelandic financial system in autumn 2008, widespread irregularities of lending started to surface. Loans to favoured clients were never paid but rolled on, collaterals were weak or insufficient. Financial institutions financed the buying of their own shares, essentially converting their loan book to own capital. And all of this happened through a web of cosy relationships.

An intriguing story that I have only recently unearthed regards an Icelandic company, Hvitsstadir, privately owned by five Kaupthing managers – Sigurdur Einarsson, Hreidar Mar Sigurdsson, Magnus Gudmundsson, Steingrimur Karason and Ingolfur Helgason – set up in 2003 to buy farmland next to a salmon river in Borgarfjordur, ca 150 km from Reykjavik. The entire Hvitsstadir enterprise was financed by loans from two small saving societies, Sparisjodur Myrasyslu and Spron, their business being heavily connected to and intertwined with Kaupthing.

In 2005, Hvitsstadir paid ISK300m for a farm, which earlier owners had bought just over a year earlier for ISK85m. The owners of this farm who pocketed ISK215m from the sale were Palmi Haraldsson and Johannes Kristinsson, who already then were major clients of Kaupthing, not least through their close connection with Baugur and its owner Jon Asgeir Johannesson. In the following years, Haraldsson was the steady companion of Johannesson and Kristinsson was Haraldsson’s companion.

The timing of this farm deal is interesting because at this time the Sterling transaction was in the making. Sterling was a Danish air company, bought and sold between related Icelandic parties, making billions of Icelandic krona for the Baugur sphere and its closest allies, such as Haraldsson and Kristinsson. At the time, the Sterling sales stunned observers both in Iceland and Denmark. It was very difficult to understand why this loss making air company went up in price every few months and absorbed ever more debt until 2008 when Sterling finally sank under its debt.

With the sale of the farm in Borgarfjordur, the duo Haraldsson and Kristinsson pocketed a tidy sum of money, just as the Sterling enterprise took off. Kaupthing was a party to the Sterling saga. The Hvitsstadir saga is interesting because this tiny company exposes the private connection between the Kaupthing managers, major clients of the bank and the two small saving societies. It shows how the duo got a very good deal and consequently money right into their bank account, just when the first chapters of the mysterious Sterling saga were being written.

As to Hvitsstadir, the company continued to buy assets, financed by the saving societies. The loans – bullet loans running for a few years – were never repaid but rolled over or new loans issued to pay off existing loans. Interestingly, the last loan issued to pay up an existing loan was in Decmember 2008, after the collapse of Kaupthing and at a time when both saving societies were experiencing severe problems. The two saving societies went into a technical default few months into 2009.

But in spite of favourable loans the five Kaupthing managers aren’t free of Hvitsstadir. There was a personal guarantee attached to the loans and the five men are now being sued for the repayment of at least one of the Hvitsstadir loans, now just over ISK1bn.

Personal guarantees were widely used in loans to favoured clients in Icelandic banks, apparently to make up insufficient collaterals. It may come as a surprise that personal guarantees were part of the loan obligations on loans that apparently seem to have been set up for not being repaid. The explanation seems to be that the personal guarantees were only for the records, to make the loans look better. Witness statements in several recent court cases indicate that those who took loans with a personal guarantee were told they would never be held accountable, ie the bank in question would never make use of the personal guarantee although they were written into the loan contracts.

The key element in this kind of lending was that it wasn’t for everyone – it was only for those who had the right kind of contacts. Apart from the intriguing contacts between bank managers and their clients, the Hvitsstadir saga exposes the general favours included in these deals: loans that weren’t repaid and personal guarantees that allegedly weren’t meant to be drawn on. These were the typical features of favours in the Icelandic banking system. There is no indication of any illegalities here but Hvitsstadir is an example of a cosy relationship between bank managers, major clients and small institutions closely connected to the bank.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

What is HSBC doing in Jersey?

The short answer, provided by Daily Telegraph, is that HSBC uses this UK secrecy jurisdiction to service those who are not at ease with banks who follow the “know your customer” rules. Whatever HSB means the C, in HSBC’s Jersey operation, seems to stand for “Criminals.”

After US authorities exposed and fined HSBC for not doing enough to prevent money laundering in its US operations one might think the UK authorities would have been keen to investigate HSBC domestic operations. But it’s no such investigation that has now exposed some highly questionable HSBC accounts in Jersey. No, according to DT the accounts have been exposed because earlier this week a whistleblower sent a list of 4000 names with addresses and account balances with the HSBC Jersey to HMRC.

The list seems to read like a veritable “Who is who” of those who might find it problematic to bank with more law-abiding banks. There is Daniel Bayes, an English drug dealer now living in Venezuela. His father was sent to prison for three years after the police found Bayes’ parents housesitting a cannabis farm, owned by Bayes. Interestingly, among HSBC Jersey clients there are also three Italian bankers –Antonia Creanza and Fulvio Molvetti, both with JP Morgan and Carlo Arosio, Deutsche Bank – standing trial in Italy together with six others for misselling complicated financial instruments to the city of Milan, costing the city millions of euros with Jersey accounts.

And what is HSBC doing about this? The bank is investigating who leaked the material to HMRC.

The use of Jersey, under UK jurisdiction, is of interest here. It’s nothing new that UK arcane offshore jurisdictions are used by big banks and big companies to do things they can’t do closer to the regulators. As long as Jersey loopholes aren’t closed banks will continue their lucrative offshore activities in Jersey and other UK secrecy jurisdiction. Is the British Government going to do anything about this? Not very likely.

The Lib Dem Business Secretary Vince Cable has often criticised bankers. If he is serious about his criticism he should take a look at the role of UK offshore jurisdictions in UK banking.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Ireland: AIB pensions paid out but no investigations to speak of

There is moral indignation in Ireland right now over royal pension being paid to former managers at Allied Irish Bank. The Oireachtas finance committee is criticising the present AIB management for not requesting that former executives return their pension. Ia former AIB chief executive Eugene Sheehy is paid a pension of €529,000 per annum, while former managing director Colm Doherty will receive an annual pension of €300,000 on reaching his 65th birthday. Minister for finance Michael Noonan says there is nothing he can do but is appealing to the bank managers’ moral sense to relinquish the payments.

This is starting at the wrong end. The managers shouldn’t be dealt with on a moral ground but on a legal ground. In any company that fails it’s of vital importance that those who take over as managers investigate decisions made over the last months in order to prove their soundness and the effect it has had on the standing of the creditors. AIB received a bailout of €3.5bn in Februar 2009, which together with bailouts for five other banks contributed to Ireland itself needing a bailout in November 2011.

What should be done is to investigate the decisions taken by the AIB management (and the other banks). Is there no ground there for suing these managers?

The three main Icelandic banks failed in October 2008, ie they were not recapitalised. The winding-up boards of all the three failed banks are suing managers and some board members for damages and losses caused. The amounts run to millions of euros. If these cases are won these managers won’t have much left. – In addition, the Office of the Special Prosecutor is pressing criminal charges against some of the managers but that’s an other saga.

Apart from charges against Anglo Irish manager Seán FitzPatrick and two colleagues (concerning loans to ten businessmen in summer 2008 to buy AI shares no one else wanted to buy), not much is happening on the legal front. I fully understand that Irish ministers feel they can’t relieve bankers of their pensions – but ministers could use their power to push the boards of banks, now partly or mostly state-owned, to explore thoroughly if all was sound and safe in these banks before they failed. Indeed, that should have been done long time ago. Is the AI loan to the “golden circle” really the only questionable deed before the six Irish banks failed?

*I have earlier written on the “golden circle” (ia here) – I find it astonishing that if this “trick” was known it would be the only questionable action taken by the six failed Irish banks. The Mahon report tells stories of some dubious dealings here and there in the 1980s and the 1990s.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Crisis, corruption and the pressing need to uproot corruption

One of the things I’ve learnt after the Icelandic collapse – and from observing economic disasters in the euro zone – is the importance of sound allocation of money. If a banking sector, or big parts of that sector, ignores financial rationale and allocates money not according to financial soundness but according to connections, cronyism, own benefits, disaster looms.

I have written on this topic earlier – and now I’ve expanded on it in a blog on the Le Monde Diplomatique website. I firmly believe that the crisis in the eurozone countries can’t be fully understood – and dealt with – unless some attention is paid to uprooting corruption. People in the worst hit countries aren’t just upset because of austerity measures but because they know that austerity isn’t enough.

For anyone who isn’t Irish, it may come as a surprise that Ireland can be seen as a corrupt country. True, it’s not a country where you can bribe a judge but that’s not the only level open to corruption. The Mahon report on Ireland in the 1980s and the 1990s throws a light on the situation at that time. The events leading up the collapse of the Irish banking system in 2009 shows the same trends.

The European Union needs to wake up and take this matter seriously. Corruption needs to be fought and uprooted. It won’t happen over night, it won’t happen at all if no attention is given to it – but it will happen slowly slowly if corruption is fought sensibly and forcefully.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

OECD: fighting corruption sub specie aeternitatis

OECD has published a report on bribery in France. OECD’s fight against bribery in international business is a work in progress and this report is the Phase 3 Report on Implementing the OECD Anti-Bribery Convention in France. The report includes damning criticism on France’s “lacklustre response” by French authorities in taking measures against French companies practicing bribery abroad by paying foreign officials.

The press release states:

France should intensify its efforts to combat the bribery of foreign public officials. Only five convictions – of which one, under appeal, involves a company – have been handed down in twelve years. The OECD Working Group on Bribery is concerned by the lacklustre response of the authorities in actual or alleged cases of foreign bribery involving French companies. The Working Group finds that sanctions are not sufficiently dissuasive and expresses concern over the lack of confiscation of the proceeds of corruption.

The criticism is so serious that major media publications wrote about the French shortcomings and citing examples, see a BBC reporting here.

The time scale here is interesting. The OECD Convention on Combating Bribery of Foreign Public Officials in International Business Transactions entered into force on 15 February 1999. Over 13 years later, France isn’t doing better than this. France now has 2 years (!) to respond to the OECD Working Group on steps it has taken to implement the new recommendations put forth by OECD in the Phase 3 report.

The worthwhile goal of clamping down on corruption in international business seems to be pursued sub specie aeternitatis.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.