Archive for March, 2013

Myth-busting

It was good to see the FT (paywall) taking up some of the myths of Icelandic recovery. Funnily enough, Icelanders have not been the proponents of the idea that Iceland is some sort of a model. From early on, after the collapse in October 2008, foreign economists have looked to Iceland in search for arguments for their various ideas, often with quite misunderstood facts and/or context.

More on this later – I’ve often mentioned these myths and will do more of it – but I was intrigued to see my Economonitor article, co-written with professor Thorolfur Matthiasson, University of Iceland, quoted by the FT as the work of “two Icelandic experts.” The article shows that the cost to Iceland of the collapse of the banks has indeed been substantial, 20-25% of GDP. There are now 355 tweets and 205 Facebook shares of the Economonitor article so it is far to say it has had a lively distribution.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Crisis and the manifold damage of cheap money

Now that the financial markets have moved out of Euro crisis mode, at least for the time being, calm reigns again – or as much calm as you are likely to find in that testosterone driven sector. So far, not even a muddled election outcome in Italy has caused much market flurry. However, the Euro debts have not evaporated but with the enchanting words of Governor of the European Central Bank Mario Draghi and a EU banking union in spe debt-ridden Eurozone countries gain time to put its economies in order.

This calm allows us to reflect on the wider aspects of the financial crisis on both sides of the Atlantic, such as the contributing role of interest rates in the crisis. Normally, interest rates shot up in good times and sank in bad times but during the last twenty years the rates have more or less been low all the time in the US, the major European economies and, with the birth of the Euro, also in the Eurozone. Things tend to turn into laws of nature when they have been around for a while. The danger is that “chronic” low interests has turned into a law of financial nature, creating quite devilish problems of its own.

Let us look at interest rates in the US and the Eurozone.

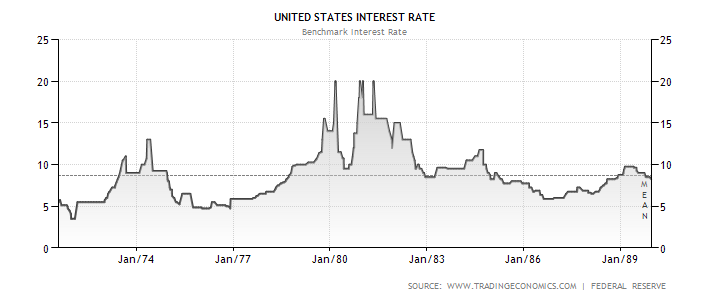

Table 1. US interest rates January 1971-December 1989.

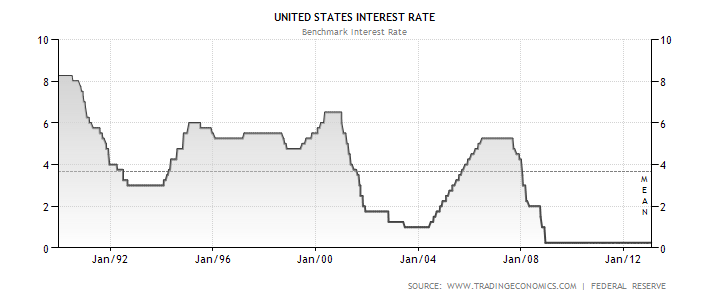

Table 2. US interest rates January 1990-March 2013.

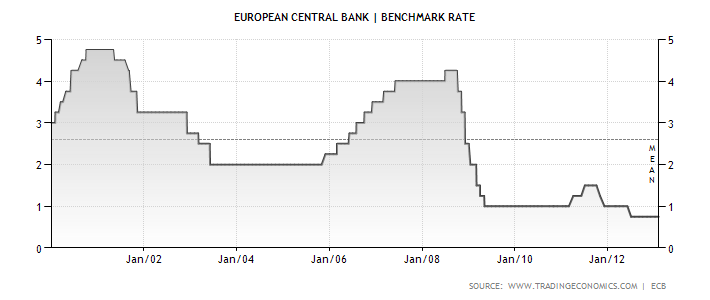

Table 3. ECB interest rates January 2000-March 2013.

In the US money has been cheap since 1990 and exceedingly cheap since 2000, compared to 1971-1990. The Euro, in existence from 2000, knows nothing but low interest rates. Consequently, funding cost in the developed world has been low. This has affected not only the behaviour in the financial sector but also sovereigns.

The 1990s and dotcom defying financial gravity

During the internet bubble of the late 1990s investment bankers, trying to be with it, took off their ties to bond with young dotcom visionaries brimming with bright but unproven ideas. When the tie-less bankers needed to calm their “tied” colleagues, who disbelieved that businesses with no profits in sight could be good investment, they explained that these new businesses were governed by new information age laws beyond the understanding of anyone except the dotcom-initiated.

Of course things proved to be less different than it had seemed. And so the new millennium started with the reaffirmation of the old rule that things are only worth as much as someone is willing to pay. Great losses ensued from the new age not being new and from other fallacies. In 1998, the demise of an obscure hedge fund called Long Term Capital Management – two of its board members, Myron S. Scholes and Robert C. Merton, won the Nobel Prize in economics in 1997 – threatened to bring down the US financial system. The New York Federal Reserve quietly organised a $ $3.625bn bailout by the fund’s largest creditors. Thus ended a decade with – in historical perspective – low interest rates. But yet lower rates were still to come – and even greater losses, this time not absorbed by creditors but tax-payers.

Cheap money, revolving doors, light/no-touch regulation

At the time it seemed like a good idea to start the new European currency with low interest rates; in making their decisions European central bankers looked to the US where interest rates had started to fall even before 9/11. The belief in light-touch, or almost no-touch, regulation inherited from the 1990s also took firm hold on both sides of the Atlantic.

The first decade of the new millennium was thus marked by historically low interest rates, pared down regulation and hands-off financial supervision. Another new feature was the revolving door between banks and their regulators. This back-and-forth enmeshed banks and their authorities in a spider web of cosy relations and friendships.

Money was so cheap that spending it poorly had little consequences. Banking was done like a Jackson Pollock painting: you took a really big canvas and splashed it with colours. It didn’t matter too much if it didn’t make sense – it looked fine in the annual reports written by auditors who knew how to make the balance sheets look good, with tools such as Lehman’s now so infamous Repo 105.

Cheap money, favours and the separation of debt and assets

When the appalling banking practises of the Icelandic banks were exposed in the Icelandic SIC report in April 2010, not only were widespread suspicions of shady dealing confirmed, but the report showed that what had gone on was much worse than anyone had imagined. Big international banks and auditors from the Big Four were also part of the new Icelandic saga of failed banks and extreme banking.

What the SIC report described, under the term “banking,” was in fact a double standard banking: while most clients were treated as any clients in an ordinary bank a small group of clients – the biggest shareholders and their satellites – were lent beyond legal limits, often against weak or no collateral. The financial rational was unclear but the bankers were certainly egged on by cheap money. Iceland has traditionally been a high-inflation high-interest country and when Icelandic bankers suddenly had access to almost unlimited low-interest loans abroad they behaved as if they were at an open bar for the first time in their lives: they binge-borrowed and binge-lent.

The last few years have shown that the favours during the boom years were greatly profitable to those who were allowed to binge-borrow. A mercenary army of specialised lawyers and accountants made sure that the cheap money turned into lasting favour. In galaxies of offshore companies debt was skilfully separated from assets. After 2008, one empty shell company after the other has collapsed, leaving behind astronomical debt and hardly any assets. The creditors, not only the failed banks but also pension funds, get next to nothing.

For every such bankruptcy it seems likely that previously underlying assets are tucked away offshore. Consequently, the Icelandic tycoons who profited from the binge-borrowing are, almost without exception, so far doing alright in spite of spectacular bankruptcies in companies previously owned by them.

Separating debt and assets was not unique to Icelandic tycoons. London remains one of the biggest offshore centres in the world with a large number of offshore specialists. The Irish media are following the gigantic asset struggle as Irish tycoons like Sean Quinn, Patrick McKillen and Derek Quinlan are fighting not to pay their debt to the public bodies that now hold debt from Irish banks, recapitalised by the state.

In all debt-ridden Euro-countries the crisis has exposed reckless – and often corrupt – lending that has enriched favoured clients who continue to profit. Lending fuelled by cheap money, made more reckless by securitisation as lenders did not need to fear the consequences of unsustainable lending.

The sovereign curse of the cheap

During the boom time of cheap money sovereigns like the UK were tempted to fiscal frivolity. Instead of cutting down borrowing, debts expanded. Even in frugal countries like Germany sovereign debt shot up. Cheap money meant there was little pressure on governments to think of necessary but difficult and complicated structural reform, such as labour market reform or competition.

In a recent article in Foreign Affairs, Fareed Zakaria sums up the effect of cheap credit in the US:

In poll after poll, Americans have voiced their preferences: they want low taxes and lots of government services. Magic is required to satisfy both demands simultaneously, and it turned out magic was available, in the form of cheap credit. The federal government borrowed heavily, and so did all other governments — state, local, and municipal — and the American people themselves. Household debt rose from $665 billion in 1974 to $13 trillion today. Over that period, consumption, fueled by cheap credit, went up and stayed up.

Pricing risk is now a much-discussed topic in finance. Under-priced risk in lending to countries like Greece is a case in point. Lending will always be seen as less risky in times of low interest rates – and with chronic low interest the risk assessment can be unhealthily affected.

The financial sector thrived and expanded with low interest rates and soft regulation. So much so that it became more powerful than the state bodies set to guard it. Certain financial institutions became too big to fail. Instead of punishing creditors it was mainly taxpayers in developed countries like the US and Europe who shouldered the losses of the financial sector. Debt from the private sector migrated effortlessly to the public sector. Now, the link between profit and risk was broken and those who pocketed profits no longer shouldered much risk.

There is no change in sight. In the present crisis-doomed atmosphere there are – for obvious reasons – few calls for higher interest rates. Yet, in Japan low interest rates have not solved the problem. All the money printed to sustain the low interest rates should have fuelled inflation but for some reason it has not happened. Maybe we are just postponing another even greater disaster with our low interest rates.

I am not arguing low interest rates is the only root to the troubles in the financial sector, that would be overly simplistic. But cheap money should be considered a contributing factor in the present financial misère and its curse takes on many forms.

Yes, we need proper structures to rein in the financial sector – splitting apart retail banking and investment banking, firm regulation and supervision, the next set of Basel rules etc – but all these measures with fancy names must do one simple thing: to prevent bankers from administering money as if were worthless.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.