Plan to lift capital controls: crunching the numbers… again

In the case of Glitnir there was a retrade – the numbers have been renegotiated since the June plan. The government has talked effusively about clarity and transparency in liberalising capital controls but the process of introducing such a plan has been characterised by obfuscation and opacity. The plan seems sensible but earlier promises by the prime minister’s party, the Progressives, of gigantic windfall seem to have pushed the government to play a game of make-believe, smoke and mirrors. Selling the banks will prepare for the coming years: drumming up the fear of foreign investors masks the fact that the greatest danger is the mind-set of the boom years.

The press conference October 28, to introduce the assessment made by the Central Bank of Iceland, CBI of the draft proposals from Glitnir, Kaupthing and LBI, was a very low-key event held at Hannesarholt, a small culture house in the centre of 101 Reykjavík – nothing like the hugely publicised and carefully staged June event at Harpan, the glass palace by the harbour.

In June, when the plan to lift capital controls was formally introduced, the emphasis was on the large funds, altogether ISK850bn or 42.5% of Icelandic GDP, which could be recovered by the planned stability tax. There was albeit to be some deduction, the number was closer to ISK660bn but yet, the tax was the thing and the numbers astronomical.

Already then, it was heard from all directions that in spite of the tax rhetoric, minister of finance Bjarni Benediktsson was not keen on the stability tax. He preferred a negotiated stability contribution, seeing it as best compatible with his goal of the least legal risk and taking the shortest time, as the International Monetary Fund, IMF, also recommended.

Lo and behold, the CBI now recommends stability contribution, as governor Már Guðmundsson presented last week (full version in Icelandic; a short one in English) firmly supported by Benediktsson at last week’s press conference. The stability contribution mentioned is ISK379bn but plenty of numerical froth was whirled up, as so-called counter-active measures, pumped up to a sum of ISK856bn, no doubt meant to trump the tax of ISK850.

With the booming Icelandic economy luckily there are strong indications that the economy can well cope with the measures planned; getting rid of the controls will be a big leap forward for Iceland. What leaves a lingering irritation is the illusion and mis-information used, no doubt to make the Progressive party’s election campaign promises look less outrageous now that the plan goes in an entirely different direction compared to its earlier promises.

A bank or two

Due to the toxic legacy of Icesave, the Left government (2009-2013) was forced to take over the new Landsbankinn. What now came as a surprise was to see the government accepting to take over Íslandsbanki as part of the Glitnir solution.

Clearly, Glitnir with its large share of ISK assets was always going to be a tricky situation to solve but well, this turn of event was a surprise.

Until the announcement, Glitnir’s winding-up board, WuB, had bravely tried to convert its largest Icelandic asset, Íslandsbanki, into foreign currency by selling it to foreigners paying in foreign currency. Time and again there was news about an imminent sale, to outlandish elements – Arabic and Chinese investors were mentioned.

Cough cough, getting such investors accepted as fit and proper by Icelandic authorities was never going to be trivial though getting the Icelandic political class agreeing to foreign owners was a no less daunting task. After all, Iceland is the only European Economic Area, EEA, country where the banks are entirely under domestic ownership.

It is still unclear what the price tag on Íslandsbanki is. At first I understood that the bank would be acquired for a fraction of its book price of ISK185bn, of which Glitnir owns 95%, ie. ISK176bn. Now I’m less sure; apparently the price might be as much as ISK164bn.

Glitnir number crunching

According to previously published information, the stability contribution amounted in total to ISK334bn. The recent changes to the Glitnir contribution are not entirely easy to decipher.

As I pointed out earlier the new Glitnir agreement was indeed a retrade since Íslandsbanki was unable to honour previous plans. With the new plan Glitnir gives up 40% of the planned FX sale of Íslandsbanki, valued in ISK at ISK47bn as well as Íslandsbanki dividend of ISK16bn, meant to be paid in FX, in total ISK63bn. In return creditors are allowed to exchange more ISK into FX than earlier planned.

This seems to rhyme with the Ministry of finance press release: “According to the above-described proposal, the transfer of liquid assets, cash, and cash equivalents will be reduced by 16 b.kr. because of the proposed foreign-denominated dividend to Glitnir, which will not be paid, and 36 b.kr. due to other changes provided for in the amended proposal from the Glitnir creditors.”

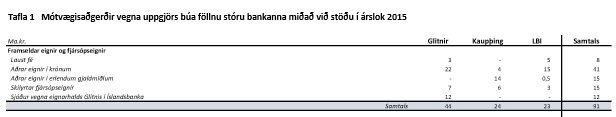

(From the Oct. 28 Icelandic CBI report; counter-active measures related to the estates of the three big banks, at end of 2015; 1. line Cash; 2. Other ISK assets; 3. Other assets in FX; 4. Cash-sweep assets)

The interesting thing is that the CBI report seems to indicate that this has negative impact on the CBI currency reserve, by ISK51bn

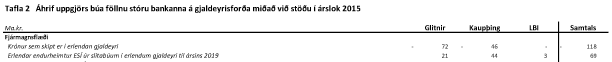

(From the Oct. 28 Icelandic CBI report; counter-active measures related to the estates of the three big banks, at end of 2015; 1. ISK converted into FX; 2. FX recovery by ESÍ, Assets held by CBI, from the estates, in FX until 2019)

Smoke and mirrors

It has been my firm opinion that since the estates, because of capital controls, can’t be resolved as a private company normally would, i.e. without a state interference, the outcome should be negotiated. This has now happened, a welcome and wise approach.

The smoke-and-mirrors events that the government has chosen in introducing the latest step towards lifting the controls is however neither wise nor welcome. Considering the emphasis in June on the stability tax the step taken now towards stability contribution can’t be said to be a logical step on from the June plan though an entirely sensible plan. Indeed, the June emphasis on the tax was a deviation from what Benediktsson seems to have intended for quite some while, i.e. a negotiated contribution and not a one-sided tax.

Value of Íslandsbanki v Arion

With news that investors are seeking to buy Arion it seems that the p/b in question is 0.6-0.8, where the lower estimate may turn out to be the more realistic one.

However, this is in stark contrast to the p/b that the state seems to be paying for Íslandsbanki, i.e. 0.93. Considering the banking sector in Iceland – probably still too big and still miraculously gaining from one-off legacy windfall – this price for Íslandsbanki would be nothing less than staggering and could well be seen as a total failure on part of those negotiating for the government.

Arctica Finance and Virðing – ties to politics and the past

It comes as no surprise that the pension funds are buyers in spe of the Icelandic banks. According to news in Iceland, it seems there are two finance firms – Virðing and Arctica Finance – vying for buying Arion. As could be expected, both have ties to politics and the past.

Virðing is run by ex-Kaupthing bankers i.a. Kaupthing Singer & Friedlander manager Ármann Þorvaldsson, owned by investors with various ties to the boom times and very active during the last few years. Arctica Finance was set up by bankers mostly from old Landsbanki, i.a. Bjarni Þórður Bjarnason, seen to be strongly connected to the Independence Party, Benediktson’s party. Unsurprisingly, both firma are courting the pension funds, the source of the greatest financial power in Iceland.

The really worrying aspect here is that the pension funds have all clung religiously to their mantra of being non-interfering non-active owners. During the boom years the pension funds were closely aligned with the banks and in the end lost heavily because of these ties and their unquestioning and uncritical attitude to the banks. There were clear indications of clustering: certain pension funds seemed particularly close to certain banks and certain large shareholders.

The billionaire-makers of Iceland: the pension funds

In most countries such ties exist to a certain degree but in Lilliputian Iceland these ties of friendship, kinship and political ties, border on the incestuous.

If we are now seeing these old ties revived among owners of one or more banks Iceland is set for round two of running the banks as during the boom years: with a chosen group of what I have called “preferred clients” and their fellow-travellers, i.e. clients who got collateral-light or no-collateral loans, who got bullet loans that were continuously rolled on, never classified as non-performing – and then all other clients who just got the professional scrutiny any normal person can expect from a bank.

Indeed, the pension funds are not only king-makers in the new Iceland but billionaire-makers. This has to a certain degree started, though on a minor scale so far: the pension funds are already investing with groups of investors who are doing very well from these ties. Clearly, investors chosen as the funds’ co-investors are pre-destined to do exceedingly well.

Indeed, the pension funds are not only king-makers but billionaire-makers.

The fight against foreign ownership – to control Iceland

This possible danger of the pension funds repeating past mistakes is compounded in an Icelandic-owned banking system with no foreign competition and no foreign ownership, a wholly exceptional situation in Europe.

Seen from this point of view it is utterly fascinating to notice that many in power in Iceland, both in politics and business, have for decades fought with all their might against foreign ownership of banks or any sort of important businesses in Iceland – and still do.

From the point of view of these old bastions of power Iceland needs to be connected to the outer world but only to the degree that Icelandic entities can make use of connections abroad, not the other way around, i.e. no foreign ownership in Iceland. Needless to say, these powers fiercely oppose closer connection to the European Union – nothing more than the EEA, thanks!

The fight to link with the pension funds and to buy banks is the latest apparition of interest politics in Iceland: it is a battle of the soul of Iceland and the weapons are fear of foreigners and foreign ownership though the real danger is entirely domestic: the danger of the same mind-set that ruled the banks during the boom years and eventually pushed them off a cliff in October 2008.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Just an idea: privatisation the Russian way

Owning one bank, Landsbanki and, as seems, soon becoming the owner of the second one, Íslandsbanki, the Icelandic government needs to decide on if to privatise the banks again and then how it should be done. Bjarni Benediktsson leader of the Independence Party has aired his idea that five percent should be given to the nation. The most famous example of a privatisation based on giving away shares was the rather notorious privatisation in Russia in the 1990s. Considering that this created an easy way for some oligarchs to acquire public good for little this hardly seems like the brightest idea. In general, the state should not be in the business of handing out presents but maximise returns on behalf of the nation.

At the weekend’s party conference, Bjarni Benediktsson minister of finance and Independence Party’s leader aired his idea that the state could create the largest possible shareholder base in the three new banks by giving every Icelander shares in the new banks. His suggestion was 5%. At present, the state owns 13% of Arionbanki, 97.9% of Landsbanki and might soon own the whole of Íslandsbanki, where it currently owns 5%.

The party conference, a biannual event, was held as the party’s standing in the polls is record-low, at 21%, compared to 25% in the elections 2013, far from the 35% to even above 40% in earlier decades.

It is no doubt a well-intended idea but the fact that the party leader throws this out as just an idea is intriguing, perhaps also rather worrying, considering that this regards a state asset. So far, Benediktsson has been more associated with planned policy-making rather than the top-of-my-head policy prime minister Sigmundur Davíð Gunnlaugsson has become known for.

It was also interesting that Benediktsson mentioned Icelanders were 300.000 when they are actually 330.000 – after all, Icelanders take great pride in the fairly rapidly growing nation. And most of all: Benediktsson does not seem to remember that privatisation via gifts has indeed been tried before – in Russia.

When this dawns on Benediktsson and his advisers they will learn the whole story of the origin of the wealth of some of the largest oligarchs of the 1990s, who organised a buy-out for a pittance of large chunk of these shares to the popolo. Not a very edifying story. After all, a hand-out of this kind seems unthinkable in the kind of well-governed countries Iceland likes to compare itself to.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

The Glitnir agreement: crunching the numbers and the politics

“Is this a retrade?” creditors will be asking themselves as they scrutinise the agreement reached between the Icelandic Task Force, the government’s advisers, and representatives of the three estates. As regards LBI and Kaupthing, probably not – relevant decisions will be made according to the June 8 agreement. However, Glitnir is a different case: yes, it is a retrade but the June agreement was probably never going to work for Glitnir. the main thing is that the present agreement with Glitnir and earlier with LBI (and Kaupthing probably by the end of this week), which means that the yoke of the capital controls will be off Icelandic shoulders.

Without much ado LBI announced last week that it was ready for a composition following the June 8 guide-lines. The LBI situation is very different from Glitnir and Kaupthing – LBI has hardly any ISK assets to speak of, it doesn’t own Landsbankinn, the Icelandic state does. The relative ease can be seen from the fact that the LBI stability contribution is only ISK14bn. The lion share of the LBI funds goes to priority creditors, i.e. the UK Treasury and those who bought the claims of the Dutch Central Bank earlier this year but the stability contribution will be paid by those holding general claims.

Kaupthing is due to pay ISK120bn in stability contribution according to the June 8 guidelines and will most likely do so. Will its main Icelandic asset, Arion bank, also end up in public ownership? That is unlikely, the constellation in Kaupthing is entirely different compared to Glitnir. Kaupthing’s only ISK asset is Arion bank, whereas Glitnir had around ISK150bn in ISK cash and assets, in addition to Íslandsbanki, i.e. the problem of foreign-owned ISK assets is much greater in Glitnir than Kaupthing.

Consequently, Glitnir was a much harder nut to crack. The task force accepted Glitnir’s solution in the letter Glitnir sent in, as did the other banks, in connection to the June 8 plan; i.e. the task force accepted that the solution Glitnir suggested fulfilled the stability criteria. However, at a closer scrutiny – most likely done by the CBI (which should have been kept closer to the negotiations because they have the necessary insight but weren’t) – it became clear that no, it actually did not. Therefor a retrade, i.e. a new agreement for Glitnir.

Discussing the Glitnir agreement on Rúv October 20 minister of finance Bjarni Benediktsson stated that “we (i.e the government) intervened in the process at the right time.” Another way to look at it is that it took the government two and a half years of wrestling to agree to sing from the same hymn sheet and accept that should the process be consensual the only sensible way was to negotiate the outcome with creditors.

After deducting priority claims the stability contribution amounts to 80% of the ISK assets in the tree estates or 20% of their total assets – interestingly, numbers that have been swirling in the air from 2012. Something in this direction has always been the obvious solution. The delay in acting on it was the political price.

The contribution, which in June amounted to ISK334bn – ISK14bn from LBI, ISK120bn from Kaupthing (given that the finalising brings no further changes) and ISK200bn from Glitnir – will now most likely amount to almost ISK380bn, with the increase coming from the new Glitnir agreement.

The June plan versus the new plan

Benediktsson mentioned that the government had intervened, a word which could for years not be uttered aloud. In the October 20 statement it is for the first time mentioned that there were indeed negotiations. This was necessary because contrary to what the task force stated in June the Glitnir June proposals did indeed not fulfil the CBI stability criteria.

So what is the difference between the June and the new proposals (see the details here)?

The key item is Íslandsbanki. At the end of last year the bank’s capital was ISK184bn of which ISK175bn or 95% belongs to Glitnir, 5% to the Icelandic state (which owns 5% shares in the bank).

The June plan was to lower the capital by a dividend of ISK37bn, i.e. dividend paid out in ISK, in addition to dividend paid out in foreign currency, amounting to ISK16bn, roughly reducing the bank’s capital down to ISK120bn. The dividend paid out in ISK was to go towards the stability contribution, i.e. to the Icelandic state; the foreign currency dividend to creditors.

The plan was all along to sell the bank for foreign currency, i.e. convert this ISK asset into foreign currency asset so the creditors could easily be paid out without upsetting the holy grail in all of this – Iceland’s balance of payment.

Further, the June agreement stipulated that 60% from the expected sale in foreign currency would go towards the stability contribution, i.e. paid in foreign currency whereas the Glitnir’s creditors would get 40%.

The June snag

So far, so sensible. Except this apparently so perfect plan had one snag: Íslandsbanki did not have the financial strength to pay all this dividend in addition to the deposits of the failed banks, which creditors could take over at composition (the three estates have deposits in the three banks – Landsbankinn, Arionbank and Íslandsbanki – amounting to ISK109bn in ISK and ISK138bn in foreign currency at end of 2014; table vii-2).

This problem became clear in July when Glitnir and Íslandsbanki came to an agreement regarding the recapitalisation of Íslandsbanki which involved extending the maturity of Glitnir’s deposits in Íslandsbanki. The stability contribution clearly had to be paid out in cash, not by a bond.

So what are the changes made in the new plan?

The creditors pass on the ISK16bn dividend (that should have been paid out in foreign currency) and they also pass on the 40% in the hoped-for foreign currency sale of Íslandsbanki (which frankly did not seem about to happen, also because the foreign owners might not suit the political commanding heights in Iceland) – in total, they pass on ISK63bn.

What do they get in return for this sum? They don’t need to refinance a subordinate foreign currency loan, which the Icelandic state placed in Íslandsbanki, set up to entail Glitnir’s domestic operations. In Glitnir’s accounts end of June 2015 this is put at ISK20bn.*

Thus, what the creditors are in reality giving up is ISK16bn + (0.4 x 120bn) – 20bn = ISK44bn or 25% of their share of Íslandsbanki capital of ISK175bn. The task force is offering them to buy the bank at price to book 0.75.

Given that Landsbanki and Kaupthing will pay respectively ISK14bn and ISK120bn in stability contribution and Glitnir will now pay additional ISK244bn, the total is ISK378bn.

The most important outcome is that is the one Benediktsson has long been advocating, as has i.a. the IMF and the CBI: a consensual agreement, meaning that creditors take this as a final solution and will not sue the Icelandic state neither for this nor earlier actions, i.a. tax on the estates in 2014. No legal wrangling, no litigation all over the world that could delay the lifting of the capital controls for unforeseeable future. The stability tax is out, the stability contribution in.

Through the prism of Icelandic politics

Nothing can be understood in this lengthy process since Kaupthing and Glitnir presented their composition plans in 2012 and 2013 except through the prism of Icelandic politics.

Panic politics is now a passé possibility for the Progressive party. At ca. 10% in polls, compared to 24% in the elections in spring 2013, prime minister Sigmundur Davíð Gunnlaugsson could in theory have attempted to raise hell and claim that the difference between the tax and the contribution was unacceptable and he was the man fighting Iceland’s case to wring more out of creditors than the paltry ca. ISK400bn compared to ISK850bn from the tax. However, with the standing of the Pirate party in the polls – ca. 35% over the last few months – any discontent is more likely to fatten the Pirates rather than the progressives.

The June plan was to a certain degree presented on false premises by putting so much emphasis on the tax and how much it would bring. The risk linked to the non-consensual stability tax was humongous, compared to low risk of a negotiated and consensual stability contribution. These numbers have lingered on in the debate, thus kept on skewing it.

It took less than six years to bankrupt the privatised banks (they were fully privatised by end of 2002), many Icelanders will now feel uneasy that the state now owns not only one but two banks. However, that is a challenge for Icelanders to solve and will test how much, if anything was learnt following the 2008 collapse.

A good deal for Iceland?

Is this a good deal for Iceland? And is this a good deal for creditors? Yes. Both parties have a great interest in bringing the matter to a close. Iceland needs to move out of the shadow of the capital controls and now that the economy is booming again (perhaps dangerously so but that’s another saga) it’s paramount to make full use of the good times. The creditors will want to run for the exit, with whatever they get in order to invest elsewhere and get out of the sphere of Icelandic politics.

Both parties will be asking themselves what is the price of risk. Reducing uncertainty will be a profit for both parties and not the least for Icelanders themselves. In addition, Iceland should be worried about the reputational risk. As I have pointed out earlier the path towards a deal has, from the point of view of foreigners “been tortuous, with new deadlines, conflicting messages from Icelandic politicians and deals that are a deal until the authorities think of something else. Some may think this is maverick and cool, little Iceland fooling the financial markets. Others will beg to differ.”

I have earlier written extensively on all aspects of the estates and capital controls so please browse and search if you are looking for specific issues.

*Update: as stated, creditors don’t need to refinance the loan – not easy to measure the time value of money involved. They do however get what remains of the loan as a payment for Íslandsbanki, which means that their gain is a bit more than ISK20bn, to be precise.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

What Iceland needs to consider…

Now that a deal with creditors of the three largest banks – Kaupthing, Glitnir and Landsbanki – has been drawn up and is being finalised (by the end of the week?), there are issues for Icelandic authorities to consider.

From the point of view of foreigners, the path towards a deal has been tortuous, with new deadlines, conflicting messages from Icelandic politicians and deals that are a deal until the authorities think of something else. Some may think this is maverick and cool, little Iceland fooling the financial markets. Others will beg to differ.

Iceland, as any other country, needs investment, i.a. in infrastructure and that will partly have to be financed by foreign loans. Yes, financial markets have short-term memory and there will always be young gung-ho traders rearing to do a deal. But large institutional investors, such as pension funds and other long-term investors, who are often somewhere behind the large infrastructure investments, may think differently after struggling or seeing others struggle to get their share of the assets in the failed banks.

So who is then left to finance it? The Chinese, as the British government is so enthusiastic about. Icelanders have a huge problem in general with foreign ownership, wonder if it’s any easier if it’s a foreign dictator and not just a foreign greedy hedge fund, as creditors are normally called in the Icelandic parlance.

Another worrying aspect, in terms of Icelandic financial stability, is carry trade. Eh, for real? Yes, for real. Carry trade – trading on interest rates differential – brought Iceland under capital controls in November 2008, following the banking collapse. It is stirring again.

In summer, soon after the June 8 plan on lifting capital controls was announced, foreign currency from carry trade deals started to appear in Icelandic stats. There were some inflows in July, more in August. It might now amount to 2% of GDP I’m told, far from the 44% it was in November 2008 but still… suddenly growing fast.

I thought that part of the explanation might be creditors in the three estates hedging but I’m told that is very unlikely (possibly in LBI but probably not and would not explain it all). The truth is that Icelandic bankers are again – and before their last mess is mopped up – selling this fantastic product: carry trade on the Icelandic krona in high-yield Iceland. Look around, there might even be some right now close to you in New York. And London is always close to Iceland.

The Icelandic Central Bank, CBI, has earlier put in place prudence rules, in order to counteract the carry trade situation in autumn 2008. But I wonder why Icelandic bankers still think it’s a good idea to tour the financial megapoles to sell this product that proved so toxic in 2008. Lessons learnt? I hope the CBI is paying good attention, tooth and claw.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Retrade on Glitnir – deals by end of this week

The Icelandic state will take over Íslandsbanki from creditors of Glitnir, according to a press release from Ministry of finance. This means that the June 8 agreement with Glitnir creditors has been changed. However, the trade off is certainty for a possible future upside. Given the Icelandic political climate, that is probably not a bad deal.

LBI, old Landsbanki, has already announced its intention to do a composition and is on track with it, meaning that it must already have the blessing of the government.

Kaupthing will most likely finalise its composition this week. That means that all the three banks are on track towards a composition and a stability contribution.

And the delayed Financial Stability report from the Central Bank of Iceland is now out, published on Friday to no fanfare. Intriguingly, in the introduction there is no mention of the stability tax, only the consensual contribution, levied on the estates, exactly as is now being done.

Updated to include the para on the FS report.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Agreement with creditors… almost there

As far as I understand, Icelandic officials are in London to finalise agreements regarding the estates of the three failed banks – Landsbanki (LBI), Glitnir og Kaupthing. The agreements are a necessary step in the plan to lift capital controls, long in the making.

The agreements agreed to in June were only lose outlines. The recent work aims at spelling out the precise meaning, terms and conditions.

Creditors in Glitnir and Kaupthing own respectively the new banks, Íslandsbanki and Arionbank. These two entities are also the largest part of the estates’ Icelandic assets, which cause the problem: these assets can’t be paid out in foreign currency, as the creditors, mostly foreigners, would prefer.

Glitnir has been trying to sell Íslandsbanki to foreigners but it so far without success.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Three Landsbanki managers sentenced to jail

The Icelandic Supreme Court has sentenced (in Icelandic) three ex-managers of Landsbanki to jail sentences. Two of them – the bank’s CEO Sigurjón Árnason and director of corporate lending Elín Sigfússdóttir – had earlier been acquitted by Reykjavík District Court. The Supreme Court sentenced the two to respectively 3 1/2 years prison and 18 months prison. The third manager, Steinþór Gunnarsson director of proprietary trading had been been given a nine months suspended jail sentence, which the Supreme Court turned into nine months in prison.

The case was yet another example of bankers being convicted for breach of fiduciary duty, i.e. causing losses by fraudulent lending where laws and the banks own rules were broken, in addition to market manipulation. In this particular case over ISK5bn were lent to Ímon, a company with no assets except the Landsbanki shares bought for the fraudulent loans from Landsbanki on September 30 and October 3 2008, only days before the bank collapsed.

This case, called the Ímon case, was one of the first cases of suspicious lending to surface after the banks collapsed in early October 2008. The case became symptomatic for the three banks’ lending patterns where the banks lent money to asset-less companies to buy the banks’ own shares, with only the shares as collateral in the days, weeks and months before the banks failed, as share prices were collapsing. As so many of these loans the Ímon lending was later described in detail in the Special Investigation Committee report, published in April 2010.

With this sentence, top managers from both Landsbanki and Glitnir have been sentenced to prison. There are still on-going cases against Glitnir managers.

Updated 9 Oct., clarifying the loan and lending date.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Capital controls and political rumblings

With the June plan on lifting capital controls the Icelandic government had finally managed to agree on a way out of controls or rather, the two government leaders had. But the implementation still left a room for disagreement. A recent letter to the governor of the Central Bank from the In Defence group, active during the Icesave debate and close to prime minister Sigmundur Davíð Gunnlaugsson showed unease among a certain faction of Icelandic politics. A delay in publishing the CBI’s Financial Stability report, scheduled for October 6, including a summary of the so called “stability contribution” indicates that something has been brewing. – The question is how deep this disagreement runs and if there still are political obstacles to be overcome.

Although strongly denied all along that there was any difference of opinion, the comments on lifting the capital controls from prime minister Sigmundur Davíð Gunnlaugsson and minister of finance Bjarni Benediktsson pointed in different directions. Benediktsson stressed solutions that would take the shortest time and steer clear of legal risks whereas Gunnlaugsson emphasised the funds the state would acquire. The difference was ironed out in June when a plan to lift capital controls was presented.

At the presentation all the emphasis was put into presenting the “stability tax” – and later a law on that tax was passed. However, following talks with creditors of the failed banks an agreement on “stability contribution” was what the creditors wished for, as did those who wanted to avoid legal wrangling and a stalled process to lift the capital controls.

In a recent letter, the In Defence group (set up by individuals opposing the attempt by the left green government to reach an agreement with the British and Dutch government) indicated that the stability tax would be better solution than a stability contribution. The letter was addressed to Már Guðmundsson governor of the CBI, who has already answered the group, clarifying the bank’s position.

October 6, the CBI Financial Stability report was due to be presented (including a summary of the stability measures and the plan for lifting the capital controls; only a summary of known facts, nothing new as far as I understand) but at the last moment the publication was postponed.

The CBI explanation was that there had not been enough time to present the stability contribution as expected, i.a. to the Alþingi economics and trade commission. According to the CBI there had been a last minute addition to the report, which still needed to be presented to the minister of finance. Interestingly, there is no date as to when this could happen.

Creditors of the estates of the three largest failed banks have recently agreed to what they are due to pay in stability contribution: Glitnir ISK200bn, Kaupthing ISK120bn and Landsbanki ISK14bn, in total ISK334bn. The tax would probably be just between ISK600 and 700bn.

In terms of practicality the difference is i.a. that the contribution is already agreed on whereas the tax is not and would most likely be disputed, causing further delays for Icelanders in escaping the capital controls. When the plan was presented in June it sounded as if there were two equally viable routes: a high tax or a lower contribution.

This was rather unfortunate since the debate in Iceland is now evolving in the direction of “why accepting a lower contribution when a higher tax can be harvested?” – A very misleading question, originating in the June presentation, again an attempt to paper over what seems to have been an unsolved disagreement all along.

As the Icelandic economy has been doing well, there were viable solutions to lifting the controls and these were put forth in the capital controls plan. As Benediktsson has stressed, the plan would provide the final solution to the problems keeping the controls in place. The wobbles now will test Benediktsson’s grip of things.

The question is if the In Defence letter is a sign that the group’s earlier close ally, the prime minister, is having doubts about the agreement with creditors. His party has a strikingly low following in polls, ca. 11% compared to 24% in the 2013 elections. It has been clear for a long while that now the economy is doing well the greatest risk regarding Iceland is political risk – and it still is.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

In the company of good books: recommended reading for Jeremy Corbyn

Jeremy Corbyn will no doubt discover that the wisdom of crowds isn’t always enough nor is meeting with busy world-famous economists and other wise-men and -women four times a year. Here are some books to hone his arguments and stimulate and inspire the intellectually inquisitive mind.

The distorting effect of debt and how to avoid socialising losses and privatise the profit

I’m almost finished reading House of Debt: How They (and You) Caused the Great Recession, and How We Can Prevent It from Happening Again by Atif Mian, Princeton and Amir Sufi, Chicago University. I had bought it even before Mark Carney recommended it; it was recommended to me soon after it was published last year.

No doubt Corbyn knows why debt is harmful, why fueling the housing market with debt is dangerous and why it is ominous that household debt in the UK is high. But in order to clarify and stimulate the mind Mian and Sufi’s book is both an essential and timely read, also to argue against the received wisdom that banks are different from other companies and need to be saved – no, they don’t.

The two economists have formulated what they call “the primary policy lesson of bank support: To prevent runs and preserve the payment system, there is absolutely no reason for the government to protect long-term creditors and shareholders of banks.” – So true (as Icelanders know). Alors, an essential read, also to gather sensible arguments in the debate on banks and banking, debt and the housing market, all topics that the new Labour leader needs to be as skillful in debating as he is cultivating his allotment.

The anti-social mixture of aggressive tax planning, tax evasion and offshore havens

Tax and the revenue lost to society due to the anti-social mixture of aggressive tax planning, tax evasion and offshore havens are close to Corbyn’s heart. To my mind, the most illuminating writer on these matters right now is the French economist Gabriel Zucman, who studied with Thomas Piketty (they have written articles together) and who has recently (and sadly) left the London School of Economics for Berkeley. I read his little book on tax havens when it came out in French last year but now it has luckily been published in English, called The Hidden Wealth of Nations.

Much of the material is on-line and much of the reasoning is put forth in his 2013 article, The missing wealth of nations: are Europe and the U.S net debtors or net creditors? where Zucman i.a. points out “that around 8% of the global financial wealth of households is held in tax havens, three-quarters of which goes unrecorded.” – Yes, things to work on.

Inequality, health and wealth

These days, not only the lefties are preoccupied with inequality – not only is it socially harmful in terms of wasting and wasted human resources but it also hampers growth. An easy and insightful read, the harvested fruits of a lifetime of studying these issues, is gathered in The Haves and the Have-Nots: A Brief and Idiosyncratic History of Global Inequality, published in 2010.

As an economist at the World Bank, the author Branko Milanovic (blogs here) worked on these issues long before they turned into a fashionable topic beyond the left margin of politics. And being an economist with a wealth of fabulous statistics at his finger tips he is both brilliant at choosing and presenting intriguing numbers, also with some striking graphs.

The book that led me to reading Milanovic’ book was another very different but equally weighty book, also harvesting a life time of studying these issues. Angus Deaton’s The Great Escape: Health, Wealth and the Origin of Inequality, was published two years ago and I had the pleasure of listening to Deaton present his book in London last year.

Deaton is a professor at Princeton and the inspiration for the book is partly his own family story of better lives in the generations spanning the 19th and into the 20th century. He investigates inequality not only from the perspective of wealth but also health. One point is that better health not only depends on money but good institutions.

The great escape of the title is the escape from hunger and poverty, spanning centuries in historical overview. A riveting and optimistic read, though far from wishful thinking, i.a. on development. The clear conclusion is that concentrated wealth in the hands of few is now being used to buy influence on policy making for narrow special interests, not the general good of society.

The synthesis of privatisation

Again, Corbyn will not need to be exhorted in his doubts on privatisation but it is always good to gather insight and arguments for familiar causes, especially when you spend most of your waking hours arguing and reasoning for your points of view.

I read The Commanding Heights by Daniel Yergin and Joseph Stanislaw when it came out in 1998. At the time its full title was The Commanding Heights: the Battle Between Government and the Marketplace that is Remaking the Modern World (the latter part was changed in a later edition to The Battle for the World Economy; I prefer the old one, more telling; here is a 3 parts documentary based on the book). Readers of Lenin will recognise where ,,commanding heights” stems from.

At the time, I read it more or less in one go and have since given away several copies because I think that everyone remotely interested in politics should read it. Agree or not, it is essential to understand the driving forces behind privatisation especially for those who want to question them. I have for a long time meant to re-read it, would be interesting, considering events since the book was published.

The book is often taken to have been one big bravo for globalisation and privatisation but that was not my impression at the time. After all, the authors strongly warn against special interests and stress the need for legitimacy.

And something for the soul

Apart from reading up topics that nourish his political thinking and reasoning the soul must not be forgotten. Here I suggest two books that tell stories of the have-nots in different parts of Europe in the 1930s, shaped by circumstances and ideas of that time.

Independent People by the Icelandic Nobel price winner in 1955 Halldór Laxness was published in 1934. Inspired by Laxness’ infatuation with communism and socialism, it tells the story of Bjartur, a dirt-poor crofter who fights for being independent of others, without realising that his strife goes against his own interests.

Carlo Levi’s Christ stopped at Eboli is the memoir of his political exile in a remote part of Southern Italy, Basilicata, in the years 1935-1936, not published until 1945. In Iceland, the cold harsh climate made for a difficult life but in Italy the heat and the barren earth was no less harsh. Written by brilliant and reflecting minds, both books are further demonstrations of the topics above: debt, private ownership and inequality.

Cross-posted with A Fistful of Euros.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Landsbanki Luxembourg managers charged in France for equity release loans

After a French investigation, Landsbanki Luxembourg managers and Björgólfur Guðmundsson, who together with his son Thor Björgólfsson was the bank’s largest shareholder, are being charged in relation to the bank’s equity release loans. These charges would never have been made except for the diligence of a group of borrowers. Intriguingly, authorities in Luxembourg have never acknowledged there was anything wrong with the bank’s Luxembourg operations, have actively supported the bank’s side and its administrator and shunned borrowers. The question is if the French case will have any impact on the Luxembourg authorities.

In the years up to the Icelandic banking collapse in October 2008, all the Icelandic banks had operations in Luxembourg. Via its Luxembourg subsidiary, Landsbanki entered a lucrative market, selling equity release loans to mostly elderly and retired clients, not in Luxembourg but in France and Spain (I have covered this case for a long time, see links to earlier posts here). Many other banks were doing the same, also out of Luxembourg. The same type of financial products had been offered in i.a. Britain in the 1980s but it all ended in tears and these loans have largely disappeared from the British market after UK rules were tightened.

In a nutshell, this double product, i.e. part loan part investment, was offered to people who were asset rich but cash poor as elderly people and pensioners can be. A loan was offered against a property; typically, 1/4 paid out in cash and the remainder invested with the promise that it would pay for the loan. As so often when a loan is sold with some sort of insurance it does not necessarily work out as promised (see my blog post on Austrian FX loans).

The question is if Landsbanki promised too much, promised a risk-free investment. Also, if it breached the outline of what sort of products it invested in when it invested in Landsbanki and Kaupthing bonds. This relates to what managers at Landsbanki did. In addition, the borrowers allege that the Landsbanki Luxembourg administrator ignored complaints made, mismanaged the investments made on behalf of the borrowers. Consequently, the complaints made by the borrowers refer both to events at Landsbanki, before the bank collapsed and to events after the collapse, i.e. the activities of the administrator.

The authorities in Luxembourg have shown a remarkable lack of interest in this case and certainly the borrowers have been utterly and completely shunned there. The most remarkable and incomprehensible move was when the Luxembourg state prosecutor, no less, Robert Biever Procureur Général d’Etat sided with the administrator as outlined here on Icelog. The prosecutor, without any investigation, doubted the motives of the borrowers, saying outright that they were simply trying to avoid to pay back their debt.

However, a French judge, Renaud van Ruymbeke, took on the case. Earlier, he had passed his findings on to a French prosecutor. He has now formally charged Landsbanki managers, i.a. Gunnar Thoroddsen and Björgólfur Guðmundsson. Guðmundsson is charged as he sat on the bank’s board. He was the bank’s largest shareholder, together with his son Thor Björgólfsson. The son, who runs his investments fund Novator from London, is no part in the Landsbanki Luxembourg case. In total, nine men are charged, in addition to Landsbanki Luxembourg.

According to the French charges, that I have seen, Thoroddsen and Guðmundsson are charged for having promised risk-free business and for being in breach of the following para of the French penal code:

“ARTICLE 313-1

(Ordinance no. 2000-916 of 19 September 2000 Article 3 Official Journal of 22 September 2000 in force 1 January 2002)

Fraudulent obtaining is the act of deceiving a natural or legal person by the use of a false name or a fictitious capacity, by the abuse of a genuine capacity, or by means of unlawful manoeuvres, thereby to lead such a person, to his prejudice or to the prejudice of a third party, to transfer funds, valuables or any property, to provide a service or to consent to an act incurring or discharging an obligation.

Fraudulent obtaining is punished by five years’ imprisonment and a fine of €375,000.

ARTICLE 313-3

Attempt to commit the offences set out under this section of the present code is subject to the same penalties.

The provisions of article 311-12 are applicable to the misdemeanour of fraudulent obtaining.

ARTICLE 313-7

(Act no. 2001-504 of 12 June 2001 Article 21 Official Journal of 13 June 2001)

(Act no. 2003-239 of 18 March 2003 Art. 57 2° Official Journal of 19 March 2003)

Natural persons convicted of any of the offences provided for under articles 313-1, 313-2, 313-6 and 313-6-1 also incur the following additional penalties:

1° forfeiture of civic, civil and family rights, pursuant to the conditions set out under article 131-26;

2° prohibition, pursuant to the conditions set out under article 131-27, to hold public office or to undertake the social or professional activity in the course of which or on the occasion of the performance of which the offence was committed, for a maximum period of five years;

3° closure, for a maximum period of five years, of the business premises or of one or more of the premises of the enterprise used to carry out the criminal behaviour;

4° confiscation of the thing which was used or was intended for use in the commission of the offence or of the thing which is the product of it, with the exception of articles subject to restitution;

5° area banishment pursuant to the conditions set out under article 131-31;

6° prohibition to draw cheques, except those allowing the withdrawal of funds by the drawer from the drawee or certified cheques, for a maximum period of five years;

7° public display or dissemination of the decision in accordance with the conditions set out under article 131-35.

ARTICLE 313-8

(Act no. 2003-239 of 18 March 2003 Art. 57 3° Official Journal of 19 March 2003)

Natural persons convicted of any of the misdemeanours referred to under articles 313-1, 313-2, 313-6 and 313-6-1 also incur disqualification from public tenders for a maximum period of five years.”

As far as I know the scale of this case makes it one of the largest fraud cases in France. As with the FX lending the fact that the alleged fraud was carried out in more than one country by non-domestic banks helps shelter the severity and the large amounts at stake.

Again, I can not stress strongly enough that I find it difficult to understand the stance taken by the Luxembourg authorities. After all, Landsbanki has been under investigation in Iceland, where managers have been charged i.a. for market manipulation. – Without the diligent attention by a group of Landsbanki Luxembourg borrowers this case would never have been brought to court. Sadly, it also shows that consumer protection does not work well at the European level.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.