Taxing bankrupt companies, i.e. the estates of the failed Icelandic banks?

In her blog (in Icelandic), minister of social affairs Eygló Harðardóttir has aired the idea that the estates of failed financial companies could be taxed. Yes, that debt should and could be taxed. Harðardóttir is not the first to mention this possible source of taxation – the idea has been around for a while, mostly mentioned by the minister’s party members, i.e. from the Progressive party. One of those is party leader and prime minister Sigmundur Davíð Gunnlaugsson.

Harðardóttir underlines that she is not the minister of finance so it is not for her to decide on this source of taxation but she finds it utterly natural and even desirable that estates should be taxed.

Others beg to differ. I mentioned this idea to some lawyers in Iceland who said that taxing the estate of a bankrupt company, i.e. taxing debt, runs contrary to what is normally seen as a taxable source. The minister clearly begs to differ.

The feeling in Iceland is that since the estates of Glitnir and Kaupthing are owned by foreign creditors the estates are particularly attractive as a source of income for the government. It is though not entirely correct that this will only hit foreign financial institutions – Icelandic creditors, i.a. pension funds and the state itself, own ca. 7-8% of claims in these two estates.

Taxing the estates is clearly being considered – but there are no doubt lawyers in the ministry of finance and elsewhere who will make clear that this would be a highly questionable practice.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Icelandic whaling is a relic of a past some (but ever fewer) Icelanders cannot let go of

When Icelandic politicians defend whaling they refer to the right of indigenous people to cultivate their cultural heritage and the right to control the country’s use of its marine resources. Yet, nothing could be further from the truth – whaling never played a major role in Icelandic culture, it makes no financial sense any longer but the only reason there is still a whaling station is the stubbornness of a man whose father was a major whaling magnate in the early part of last century

“If Christ and Mary give me a whale, I will give you the tail,” is one of the sentences from one of two Icelandic 17th century Basque-Icelandic glossaries. The glossaries indicate cultural ties with Basque whalers who hunted for these magnificent mammals in the oceans around Iceland. First mentioned in Icelandic annals in 1613, the Basques would at times pay a visit, which might explain why there are still people in the Vestfjords with exceptionally black hair and dark eyes.

Icelanders hunted for whale as for other creatures of the seas and made use of “drift-whales,” dead whales that drifted on shore. The meaning of the word “drift-whale” in Icelandic, “hvalreki,” has the same meaning as “wind-fall” – an unexpected good incurred at no cost.

At the time, Basque whalers sailed as far as Newfoundland as did the Dutch and the British, also the Norwegians and whalers from the British colonies in America. The whales were mostly hunted for the oil, i.a. used as fuel for street-lights, ever more frequent in major European cities from the middle of the 18th century. All this was to change in the late 19th century as fossil fuels gained popularity but whaling was still an important industry.

Already around 1900 over-hunting started to drive whalers from old hunting grounds to new. In early 20th century Russians and others used ever bigger ships and more powerful weapons to hunt for whales. After World War II whaling resumed with enormous force, culminating in 1961-62 when almost 70.000 big whales were caught.

The International Whaling Commission and whaling in Iceland

In response to over-exploitation of the big whales, the International Whaling Commission was set up in 1946, both to set quotas and for the purpose of research. For decades the interests of the big whaling nations ruled the IWC and the quotas were too low to make a difference. Over time the protection lobby got stronger and in 1982 the IWC introduced a total ban on commercial whaling, i.e. commercial whaling moratorium, enforced in 1986. Though set to be reviewed at a later time, the moratorium is still in place to this day, except for catch allowed for aboriginal subsistence whaling. The IWC now also establishes protocols for whale-watching and its whole agenda is protection.

Over time, various countries have set their own ban not only on whaling but on any imports of whale products

Around 1900 there were several whaling stations in Iceland, owned by Norwegians who employed Icelanders. In 1948, Hvalur hf, the first and only Icelandic company dedicated to hunt for big whales started operations in Hvalfjörður (Whale-fjord), ca 50 km West of Reykjavík. Minkie whale, a small whale, has been hunted on smaller boats in various places around the country, now almost exclusively in Faxaflói, the gulf around Reykjavík.

At the time, Iceland did not object to the moratorium but in 1992 Iceland left the IWC, having carried on whaling for scientific purposes. In 2002, Iceland sought to re-enter though it did try to preserve some scope for whaling by making a reservation:

Notwithstanding this, the Government of Iceland will not authorise whaling for commercial purposes by Icelandic vessels before 2006 and, thereafter, will not authorise such whaling while progress is being made in negotiations within the IWC … Under no circumstances will whaling for commercial purposes be authorised without a sound scientific basis and an effective management and enforcement scheme.’

Though not all member governments of the IWC accepted this reservation, a majority accepted Iceland’s membership to the IWC.

In 2006, Iceland concluded that commercial whaling could be resumed since the moratorium and the state of whaling had not been re-evaluated as Iceland insisted had been the intention with the moratorium. The quota at the time was only nine fin whales and 30 minkie whales. Since then, Hvalur hf, the Icelandic company, has caught whales on and off.

In 2009 the Icelandic Ministry of fisheries stipulated that fin whales could be haunted in the coming years, through the year 2013. The last two years, Hvalur hf did not send its boat out to hunt for whales but this year, with a quota of 154 fin whales, the whaling boats are out at sea.

Those strongly in favour of whaling are equally strongly opposed to Icelandic membership to the European Union since it is clear that the EU is not in favour of whaling in Iceland.

Icelandic whaling and the convoluted interests: part of the past, not the present

During the centuries, whale meat was been eaten in Iceland. The meat is very perishable, turns rancid very quickly. The layer of fat next to the red meat would be could into strips and preserved in whey. After freezing was introduced as means of preserving food, the whale meat was frozen as soon as possible. Meat from big whales was by no means a stable during the latter part of the 20th century but was at times on sale. When fresh it does not have a strong taste, the texture is similar to beef and it was sometimes used in stews as a substitute for beef. Lately, some restaurants in Iceland serve grilled minkie whale meat or cured like gravlax.

The sense in Iceland has long been that it was of vital importance for Iceland to hold on to its right to whaling – any retraction would seriously undermine Iceland’s sovereign rights to make use of its marine resources, in addition to whaling being part of the Icelandic cultural heritage. “First the foreigners forbid us to hunt for whales, one day they might tell us to stop catching cod,” was a frequent argument.

Lately however, more and more Icelanders are asking if Iceland really has any interest at all in continued whaling.

The interests of the whalers weighed against the general interests of Iceland as a country that makes sustainable use of its natural resources was questioned this week from an unexpected direction: a shareholder in Hvalur hf.

In a newspaper article (in Icelandic), Birna Björk Árnadóttir, a grandchild of one of the founders of Hvalur hf and as such, as deeply imbued in the whole ethos of whaling as can be, wrote that for years she was in favour of whaling, for the same arguments so often repeated by Icelandic politicians (translation and emphasis mine):

The species caught by us are not in danger of extinction, it is the right of a sovereign nation to make sustainable use of its resources, whales impoverish us by eating so much and last, but not least, whaling is a profitable profession, contributing export revenues to the national economy. I have now changed my mind and I guess I’m not the only one. Although certain whale species are not about to become extinct, whaling is part of our past, not our future. The argument that we should catch whales because we have the right to and we can is both out-of-date and provincial in the global society we inhabit. Consequently, it is sad to hear a new minister of fisheries refer to centuries’ old tradition in making use of resources and lack of understanding when whaling is criticised in foreign media.

Árnadóttir then poses the question if catching 154 fin whales is necessary and reasonable. She both refutes the argument of aboriginal subsistence whaling and any regional importance though the hunting creates a few jobs in Hvalfjörður. Fin whales are not on sale in Iceland, the meat is exported and since there is no Icelandic industry based on whale products this is just export of raw material.

The only market is Japan and the meat does not really sell there at all – part of the catch from 2009 to 2010 is still unsold, kept frozen there. This is the situation, in spite of numerous marketing trips to Japan the last few years and regular statements that the market is improving.

Árnadóttir is pointing out, what many have surmised: it is an illusion that there is a market for whale meat.

According to Árnadóttir, the Hvalur hf management is unwilling to reveal the cost of whaling. She wonders how much money should be thrown at feeding whale meat to the Japanese who are not buying it. The only buyer seems to have been a Japanese pet food producer who just recently announced it had stopped buying fin whales. There really seem to be no other buyers for fin whales, making the whaling a rather strange undertaking.

Are we perhaps sacrificing greater interest for less interest? Let’s not forget our main trading partners oppose commercial whaling and trade in whale products. As the situation is now there is only one person who decides if these fin whales will be caught or not. I really wish he would let go of this whaling stubbornness and use his energy and assets for something else. The barracks in Hvalfjörður and the old whaling ships do indeed offer plenty of opportunities.

Continued whaling: more Freud than financial arguments

The person Árnadóttir does not name is Kristján Loftsson, son of Loftur Bjarnason who founded Hvalur hf, together with Árnadóttir’s grandfather. There are now 98 shareholders in Hvalur hf, a holding company for various fishing industry assets. Loftsson has always been very close to the Independence Party, which has been a staunch supporter of the company and the Icelandic right to whaling. There is probably no single Icelandic company, which for so many decade has enjoyed as much governmental support as Hvalur hf.

Some say that Loftsson’s push to keep Hvalur hf whaling seems to have more to do with Freud than financial motives; he cannot let go of the activities his father built up.

It is safe to conclude that the profit of whaling is negligible if any. However, another and very different whale-related industry is booming: whale watching. Those who oppose whaling see a conflict of interest here. Those in favour of whaling claim both industries can thrive side by side.

Árnadóttir makes a forceful argument: whaling hardly contributes anything at all to the economy – and it disturbs the relationship Iceland has with its most important trading partners. But as long as politicians continue to make statements as the new minister of fisheries Sigurður Ingi Jóhannsson, the driven owner of Hvalur hf is not the only one showing considerable stubbornness.

As so often, the politicians seem to be the last to sense that ever more Icelanders do indeed think like Árnadóttir: whaling makes no sense whatsoever and it does indeed belong to Iceland’s past and not its future.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

The coalition agreement: no to EU – a softer stance towards creditors

The new coalition of the Progressive Party and the Independence Party indicates it will drop the EU membership negotiations. Former declarations by the Progressive party that money to reduce household debt will be fetched from creditors to Glitnir and Kaupthing have been softened. But voters are already losing faith in the seductive promises.

The main goal of the incoming Government is inducing much needed optimism in Iceland, Bjarni Benediktsson leader of the Independence Party said today. Benediktsson will be Minister of Finance and Economy in a Government led by Sigmundur Davíð Gunnlaugsson leader of the Progressive Party.

The first part of the coalition agreement (so far, only available in Icelandic) is on “Homes” – i.e. debt situation of private households to whom the Progressive Party promised extensive debt relief. This promise was to be financed by negotiating with creditors of Glitnir and Kaupthing in such a way that the Government would get the funds needed. The exact method was however never quite clarified.

Here is what is stated in the coalition agree on this topic (my translation; my comments in brackets):

As indexed debt increased and asset prices fell, i.a. because of the effect of the collapse of financial firms and because of their appetite for risk leading up to the collapse, it is right to use the scope – which will most likely be created parallel to the winding down of the estates (of the collapsed banks) – to assist borrowers and those who put their savings towards their homes, just like the Emergency Law (passed on October 6 2008) secured that the assets of the estates were put to use to defend financial assets and to resurrect domestic banking. The Government keeps open the possibility to set up a special correction fund to reach it goals.

This sounds clunky and unelegant but so is the Icelandic text. This statement is somewhat rambling compared to the campaign promises. This “correction fund” indicates that if the process of recovering funds towards the promises takes (too) long this fund can bridge the time gap. How the fund is going to be financed is not clear nor is it clear how much money will be used for the much announced debt relief. And when borrowers can expect a cheque or correction is not made clear either. – Gunnlaugsson said today that coalition agreements were rarely very specific but added he was very content with how clear the agreement was on this issue. To me, this clarity is totally unclear.

Both coalition parties are opposed to membership to the European Union. This is what the agreement says on the EU:

There will be a break in Iceland’s membership negotiations with the European Union and an assessment made of their status and the development within the Union. This assessment will be put to Parliament for discussion and the nation informed of it. The membership negotiations with the European Union will not be continued except after a referendum.

There are pro-EU members of the Independence Party, the party’s MPs are mostly against membership but some of them – i.a. both Benediktsson and Illugi Gunnarsson who will be a Minister for Culture and Education – have earlier aired pro-EU stance. The pressure from strong interest groups such as the fishing industry and from the party’s old guard has swayed the party into a more hard-line direction in later years. However, many of their traditional voters are still pro-EU.

The list of ministers was published tonight. From the Progressive Party:

Sigmundur Davíð Gunnlaugsson Prime Minister, Gunnar Bragi Sveinsson Minister of Foreign Affairs, Sigurður Ingi Jóhannsson Minister for Fisheries, Agriculture and Environment, Eygló Harðardóttir Minister for Social Affairs.

From the Independence Party:

Bjarni Benediktsson Minister of Finance and Economy, Hanna Birna Kristjánsdóttir Home Secretary, Illugi Gunnarsson Minister of Education and Culture, Ragnheiður Elín Árnadóttir Minister of Industry and Trade, Kristján Þór Júlíusson Minister of Health.

According to a poll published today, the Progressive Party is already losing votes, indicating that voters are turning skeptical. The party got 24.4% of votes but has now 19,9% meaning it has lost about 20% of its votes in three weeks. The Independence Party is strengthened, from 26.7% in the elections to 28.4% now. The Social Democrats are on the same losing course as the Progressive Party, drop from 12.8% to just below 12% but the Left Green rise from 10.8% to 12%.

Apart from introducing a coalition agreement today, Gunnlaugsson had an indirect brush with the justice. As he headed back to Reykjavík, from Laugavatn – the village where the signing ceremony and press conference was held – his political adviser who was driving got stopped by the police for speed-driving. The youngest Prime Minister in Iceland since 1944 is clearly eager to get on with his job. The polls today indicate that he has no time to lose.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

New Government – what is known so far (updated)

At 11.15 Icelandic time, the two parties, the Progressive Party and the Independence Party will hold a press conference to announce new ministers and their coalition agreement. What is known so far is that the Independence Party will get five ministries: finance, home office, trade and industry, education and health. The Progressive Party will lead the Government, i.e. Sigmundur Davíð Gunnlaugsson will be Prime Minister. In addition, his party will get social affairs, agriculture and fisheries, environment and foreign affairs.

The ministries are fewer than the ministerial posts because there will be more than one minister in some of the ministries. The Left Government had merged ministries. In the Welfare Ministry there is health and social affairs. In the Ministry of Industries and Innovation there is trade and industry.

And what about the membership negotiations with the European Union? According to Morgunblaðið, whose editorial stance is against Icelandic membership of the EU, the negotiations will be called off immediately. This is an indirect quote (in Icelandic) from leader of the Independence Party, Bjarni Benediktsson.

New Government, new style: the two leaders will sign the coalition agreement at some sort of a ceremony, apparently in the presence of the media, ca 100 km from Reykjavík, at Laugarvatn, a small village on the lake, Laugarvatn, which has grown around a few schools there.

In addition:

There are two things that I will be paying most attention to: EU membership and negotiations with creditors of the estates of Glitnir and Kaupthing that respectively own the two new banks, Íslandsbanki and Arion. As I have blogged on earlier, the development of these negotiations determine if and how the capital controls will be abolished.

In his recent piece on Vox EU, the Icelandic economist Jón Daníelsson writes about the Icelandic recovery, “myth or a miracle?” – Just briefly, I rather believe it is neither of these two. Further, he states: “The main reason why the Icelanders voted out their government was its deference towards foreign creditors. Iceland came under significant pressure from the IMF to accommodate foreign creditors, and the government gave in.” – I also disagree on this. The unanimous understanding in Iceland is that the Progressive Party did well because it made the simple promise of returning money to voters. As irresistible to Icelandic voters as a similar promise by Silvio Berlusconi to Italian voters recently.

Daníelsson seems to ignore that Iceland cannot both fleece foreign creditors and expect foreigners to be willing to invest in Iceland. In a global world isolationism and nationalism have its limits if a country wants to be connected to foreign trade and investments. And, by the way, attracting foreign investments has always been a problem in Iceland, incidentally as it has been in Italy.

Daníelsson seems to indicate that the drop in inflation is just a temporary one and the króna, having been stronger recently, will fall again. It remains to be seen but so far, the indication is that inflation is falling, partly due to a stronger króna, that might be fairly steady in the coming months. The Central Bank has indicated it will aim for the present króna level. More on the here, in analysis from Íslandsbanki.

According to polls, major part of Icelanders is against membership – but the majority wants to end the negotiations, get an agreement and vote on it.

PS I will be following the press conference, tweeting from it – and will blog on it later today.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Is Luxembourg waking up to the fishy smell of its finance sector?

A group of investors in Luxembourg funds have been trying to lodge complaints with the Luxembourg financial services authority, CSSF, after enduring losses in 2008. According to the FT (paywall), the group got a negative answer and little understanding from the CSSF in 2011 and has since been trying to get their complaints taken seriously, lately by sending a flurry of letters to prominent politicians in Luxembourg, i.a. PM Jean-Claude Juncker and Minister of Finance Luc Frieden.

One of the group’s interesting discoveries is that although financial regulation in Luxembourg is, on paper, comparable to other EU countries, the enforcement lags far behind. The result seems to be that if things go sour, as in these investments, the CSSF allegedly is not there to protect the interests of investors. The feeling is that Luxembourg is a country where the interests of the financial sector are seen to be best served by doing very little about eventual rogue elements.

This attitude of the CSSF will not come as a great surprise to regular Icelog readers.* Icelog has earlier dealt extensively with the plight of a group of clients of Landsbanki Luxembourg to get authorities in Luxembourg take their complaints seriously. Complaints that both regard the dealings of the bank before its demise in October 2008 and also how the bank’s administrator has handled both complaints and these clients. This group has run into closed doors time and again. Only through the extremely diligent work of the Landsbanki Victim Action Group – at great cost, both pecuniary and emotional – is the group hopefully moving its case onward.

One of the most remarkable events in that whole saga was when the Luxembourg Prosecutor issued a press release to declare his support for the Landsbanki Luxembourg administrator, thereby alleging that the clients were seeking to avoid paying their debt. The fact that the State Prosecutor saw fit and proper to give his support to an administrator of a private company puts Luxembourg in a league of its own among EU countries.

The banking collapse in Cyprus has led the attention to other financial centers in small economies, such as Luxembourg. It seems that much of the shady money, previously nesting in banks in Luxembourg, has not gone back to countries of their owners, such as Russia, but is seeking shelter in other offshore places, Luxembourg being one of them. It seems that ties between Russian and Luxembourg might be strengthening.

The fact that the Luxembourg media and international media is now reporting more on irregularities in Luxembourg increases the hope that the Luxembourg finance sector will at long last operate under the rules and regulations as should be the standard in the EU. Though Luxembourg certainly is not the only country with questions to answer regarding its finance sector, it still seems too difficult for clients of the very potent financial sector to seek justice in cases of alleged irregularities and outright fraudulent behaviour.

*Here is one log on Landsbanki Luxembourg; here are logs related to “equity release” loans, which are at the core of the Landsbanki Luxembourg saga. A log on the CSSF and the Icelandic banks.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Still waiting for a new Icelandic Government: the real test of escaping the crisis

It is interesting to see how intensely relaxed Icelandic media seems to be about the new Government in the making. First, Sigmundur Davíð Gunnlaugsson leader of the Progressive Party summoned Bjarni Benediktsson leader of the Independence Party to coalition talks in unannounced places. They went to the haute-luxe summer house of Benediktsson’s father by Lake Þingvellir, which to Icelanders signals old wealth. Then to the summer house of Gunnlaugsson’s father-in-law, more the nouveau-riche type – his father-in-law got rich from importing Toyota cars and then selling the agency at a good time. Having exhausted good countryside places they started meeting in Reykjavík but they have not much been followed around – the Icelandic media is not chasing them for the latest and tiniest moves, as happens in some other countries.

The latest report, from this weekend’s Morgunblaðið, interestingly close to both parties, says that a new Government is almost there, just few remaining issues to be resolved. According to the paper, Gunnlaugsson will be Prime Minister and Benediktsson will be Minister of Finance. Other Progressive ministries will be foreign affairs, transport and the environment whereas IP will have education, justice and most importantly health, an area the IP has signaled great interest in and, more importantly, politicies.

Though the Government is not in place yet it seems that there is one decision, which will be acted on soon: repealing of a much disputed levy on the fishing industry, the so-called “veiðileyfisgjald.” Ever since transferable quotas were introduced in Iceland in the late 1980s, levy and tax on this natural resource that fish is has been a bone of cronic contention in Icelandic politics. The measures (half-measures according to many on the left; too much for many on the right) introduced by the Left Government, i.a. this levy, did not remove the contention. If the Government starts by repealing this fishing levy, its direction and interests will be very clear to most Icelanders: yet again, there is a Government clearly following the interests of the powerful Icelandic fishing industry.

Another important signal that will be awaited is the abolition of the capital controls. Part of that big bundle is finalising the fate of the estates of Glitnir and Kaupthing, thereby clarifying ownership of the new banks, Íslandsbanki and Arion, respectively owned by the estates. Both the Central Bank of Iceland and the creditors themselves have done all the necessary work over winter. Data has been analysed back and forth and what can and cannot be done is now pretty clear. A new Government cannot truthfully say it has to start gathering information on these issues – it is all there and now needs to be acted on.

If the Government does not make a move before the high-summer and holiday season, it could be seen as if the Government is fearful of tackling this very tricky and most complicated issue or lacks the ideas as to how to proceed – or feels the options are not gainful enough for the interest groups it wants to service. And if that were the case, this Government would be a disaster for Iceland, much in need to escape the fetter of capital control in order to be, again, part of a European area of free flow of capital.

For good reasons, Iceland is seen as a country that, after all, got remarkable easy out of its collapse and crisis. But that saga is not over until the country successfully gets rid of the capital controls.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Deka Bank loses its €336m case against the Icelandic state

Deka Bank has lost its case against the Icelandic state. The bank had claimed the state was responsible for its loss of €336m, stemming from repo agreements with Glitnir, involving bonds from Kaupthing and Landsbanki. These agreements were made in early 2008, which means the bank at the time was willing to do these highly risky deals.

Deka sued the state for causing the bank’s loss both because of lack of supervision and because of the Emergency Law, passed October 6, 2008. The Reykjavík District Court passed the same judgement last year but Deka appealed. The Icelandic Supreme Court has now confirmed the earlier judgement. Seven judges passed a unanimous judgement. Normally, the judges are three but the fact that seven judges were on the case shows its importance. The judgement sets precedence for other possible claims. In addition, Deka Bank has to pay costs for the state, in total ISK3m, almost €19.000.

The ruling, so far only in Icelandic, gives an interesting insight into the relationship between Deka and Glitnir and the way these deals were done.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Important step towards clarifying the relationship between Björgólfur Thor Björgólfsson and Landsbanki

Today, a small investor in Landsbanki Vilhjálmur Bjarnason, now a newly elected member of Parliament for the Independence Party, won an appeal (in Icelandic) at the Icelandic Supreme Court, which will allow Bjarnason to call 15 witnesses and access a certain crucial email in order to clarify the role of Björgólfur Thor Björgólfsson in the collapse of Landsbanki. Bjarnason, together with other small investors, is preparing a possible compensation claim against Björgólfsson. The judgement today brings Bjarnason one step closer to such a case.

Björgólfsson, known as Thor Bjorgolfsson abroad, was the bank’s largest shareholder, together with his father, Björgólfur Guðmundsson. Pere et fils owned ca. 42% of the bank and are alleged to have controlled around 70% of the bank, through the bank’s own shares. Bjarnason alleges that Björgólfsson’s influence played part in the bank’s demise. In order to clarify these issues Bjarnason wanted to be allowed to call Björgólfsson and 15 others as witnesses.

Reykjavík County Court had earlier turned down his request. The Supreme Court has now turned that judgement around in Bjarnason’s favour, with the exception that he will not be allowed to have Björgólfsson questioned since Bjarnason might later bring a case against Björgólfsson.

The witnesses are i.a. the two former CEOs of Landsbanki, various other Landsbanki employees and employees of Novator, the investment company owned by Björgólfsson. Bjarnason will also get access to an email, said to be from Björgólfsson and his employee to FME, the Icelandic Financial Services Authority, sent early 2007, relating to ownership of Samson, the pere et fils company that held their Landsbanki shares. Björgólfsson’s father was the chairman of the Landsbanki board and there were at times two people closely connected to Björgólfsson on the board.

In the aftermath of the collapse of Landsbanki Guðmundsson went bankrupt but Björgólfsson survived. He was the largest owner of Actavis, a generic pharmaceutical company and did for a while hold the single largest loan in Deutsche Bank. Björgólfsson still has some investments in Iceland and Bulgaria and lives in London’s Notting Hill.

What Bjarnason is trying to show is that Björgólfsson and others hid the extent of Björgólfsson’s control of Landsbanki – that Björgólfsson did in fact control the bank to a greater extent than his shareholding showed and also that he got more loans from the bank than indicated in Landsbanki annual accounts. If all this had been clear, Bjarnason says, he would not have invested in Landsbanki.

Statements of these witnesses are bound to throw a clearer light on Björgólfsson’s role in Landsbanki. Whether it will tell the saga Bjarnason alleges remains to be seen. So far, Björgólfsson has always refused these allegations and claims he never exerted any influence on the bank’s management.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Iceland – will there be a Progressive-led coalition with the Independence Party?

The leaders of the Progressive Party and the Independence Party are still optimistic that their Government is just about to come into being or at least soonish. This means that a 1990s Government is almost reborn, though with one noticeable change, Icelandic tycoons like Thor Björgólfsson are rich again, people are again borrowing to buy shares in the capital controls’ fast expanding bubble. But will the two parties really be able to form a Government – and who will pay for the after-party if a bubble is forming?

The new political star in Iceland is undoubtedly Sigmundur Davíð Gunnlaugsson who single-handedly secured his vanishing Progressive Party a remarkable victory. The party, which only last year was nothing but a Cheshire cat grin, is now a big fat cat again. A cat that climbed from miserable ca. 10% in polls last year to 25% in the recent elections. Gunnlaugsson now has to secure the victory by taking the expected jump into the Prime Minister’s office.

With good times returning in Iceland – asset inflation, probably due to the bubble-making side-effects of capital controls – it seems in tune with the times that the Government just about to be born is a remake of former times. A remake though with the clear difference of the Progressives about to become the leading party. Compared to earlier times, the roles are now reversed and the rules of political law in Iceland might be broken: contrary to former times, it is no longer the Independence Party that leads.

The difficult, nigh impossible, choice of the Independence Party

After the elections I was certain the Independence Party would get the mandate to form a Government. After all, they did get most votes and I thought the Progressives would be much less likely to get other parties under their wings. The Progressives were, as I saw it, burdened with unenforceable campaign promises on private debt relief and I thought no party would be willing to tie their political fortune to this promise. I was wrong – they did get the mandate, two of the six parties elected recommended that the Progressives went ahead. They then did get the IP to the negotiation table, attempting to form the only possible two-party coalition.

I still find it difficult to believe the IP will actually go into a Progressive-led Government but then, I might very well be wrong on that one too. Many point out that the IP will feel it has to get into Government, no matter what and not leading it would be a small, or at least a tolerable, price to pay.

My feeling is that were this Government to materialise, Bjarni Benediktsson, its leader, might soon be in the situation David Cameron has been in ever since the Conservatives got to lead a coalition. Both leaders are weak within their own parties. For Cameron, merely getting to lead a coalition and not a majority Government is seen as his failure. For Benediktsson, getting into Government but merely as the second violin, might very well be held against him for the coming years.

No matter what, Benediktsson’s position will be difficult – unless he gets to lead a Government, which for the time being does not seem to be a likely outcome. Certainly, many is his parliamentary group dread being led by the Progressive Party. I still find it difficult to believe that this Government will materialise since I hear voices from the IP saying they could not possibly support such a coalition. But then the option of staying out of Government might focus these minds.

Is there any real progress in the coalition talks?

The two leaders have so far only been willing to say, every other day or so, that the talks are going well and a Government will soon come into being. This weekend, Benediktsson says they were discussing tax system changes, debt relief and the economy in general. Changes to the tax system, not only lower taxes, is an IP campaign promise the party will not back down from, he says. The Progressives did not have a firm stand on this issue but debt relief is not merely the Progressives’ Big Thing but so much did they make of it that it almost is their whole raison d’etre.

The Progressives promised to squeeze ISK300bn out of the estates, i.e. from the foreign creditors owning them, of Glitnir and Kaupthing. This money was/is then to be distributed to households in need. The opponents said this would mostly land with well-off families with high debt but able to pay down their debt, i.e. not the most in need. Their reasonably well-off middle class voters will now be waiting for the cheque and if it doesn’t appear some time soon they will feel betrayed.

If the two leaders are still discussing these key issues and have not reached an agreement one wonders what they have been talking about since the talks started some ten days ago. And why they still feel so optimistic.

Other options?

Theoretically, there are several options open to form a Government of three or more parties. However, nothing seems to be stirring in that direction. The Social democrats, the third largest party, seems to be in tatter after its shattering results. As the left tends to do in Iceland, the party is far from united behind its new leader, Árni Páll Árnason who is not seen to have the authority needed to lead the party into a new Government, were the occasion to rise.

The state of the economy, the damaging capital controls and the advisers

As pointed out on Icelog earlier, the greatest challenge for the next Government is to get Iceland out of the conundrum of capital controls and the challenge of refinancing both sovereign debt and debt of several big entities in the coming years. The Central Bank of Iceland keeps a close eye on the possible side effects such as asset bubble. In its latest report (p. 25-26) on financial stability the CBI points out the risks but its over-all conclusion is that so far all good – no bubble.

Though based on limited data and, to certain degree only anecdotal evidence, I disagree. I think the bubble is building up fast and furiously, as can for example be seen from recent IPOs of two insurance companies, TM and VÍS, whose price has risen respectively by 33.6% and 28.3% though the fundamentals have not changed. Pension Funds’ assets are rising fast – and, most scarily, I am told that banks are again lending companies and individuals to buy shares, something that characterised Icelandic banking before the collapse.

The capital controls have – again, based on anecdotal evidence – for real changed business activities. I.a. companies are buying assets abroad in order to avoid bringing precious foreign currency back to Iceland. There are rumours of small financial companies specialising in “control-avoidance” measures. And a propos the CBI: persistent rumours say a Progressive-IP coalition would be more than happy to see Governor of the CBI Már Guðmundsson leave but so far, no names are circulating as to who might succeed him.

The CBI offers the possibility of bringing foreign capital into the country for new investments, allowing the investor to exchange half of the funds invested at the more favourable ISK off-shore rate. Consequently, those investors get 20-25% more for their funds than investors using solely domestic funds. This creates inequality in the business community, which in the long run is both unfair and a potential danger to competition.

Talking to a foreign economist recently, he asked why Iceland could not just borrow its way out of the controls, i.e. extending maturities by borrowing to pay off foreign liabilities. After all, Iceland is a fairly sound European country. – The problem is that the potential lenders are among the creditors of the Glitnir and Kaupthing estates who want to see how they fare in getting hold of their assets before agreeing to further lending. In numbers the funds needed are small but they are large, measured against the GDP – somewhere between 60 to 150% of the economy, depending on how the problem is calculated. This, added to a present sovereign debt of a quite reasonable 60%, would take the debt levels uncomfortably high.

If the Progressives get to lead a Government they will have to form a policy not only to fleece the creditors but to maintain a constructive relationship. Since last year, all sorts of people have been coming up with possible solutions to the capital controls. One of those is a banker, Sigurður Hannesson, who earlier worked for Straumur, where Thor Björgólfsson was the largest shareholder, as in Landsbanki (with his father). Hannesson, now running the Jupiter fund, related to MP Bank (where David Rowland is a large shareholder) was against the Icesave agreement and is now said to be advising Gunnlaugsson on the issues regarding the foreign creditors and the estates. – And yes, with the sale of Actavis, Björgólfsson seems to have found his financial ground again though his creditors, such as Deutsche Bank, might also get a cut of his Actavis profits. Yet another sign of things returning to the pre-collapse state.

Although Iceland has returned to growth it will be a struggle in the long run to sustain growth with capital controls. The longer the Icelandic economy has to endure capital controls the greater the danger of permanently changing the business climate – and damaging the economy.

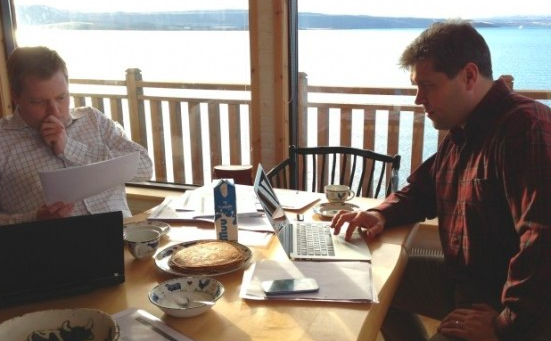

This photo appeared on Rúv last week, with Benediktsson to the right and Gunnlaugsson to the left. The photo is taken by Svanhildur Hólm, Benediktsson’s adviser, during the coalition talks, at the summer house of Benediktsson’s father. Incidentally, both leaders come from wealthy families and having a summer house, as Benediktsson’s family does, on the shores of Þingvallavatn (the lake at Thingvellir) speaks of old wealth and status in Iceland. Later, the two leaders met at the country house of Gunnlaugsson’s father-in-law, a wealthy businessman. Having exhausted family houses outside of Reykjavík the leaders have then been meeting in the capital.

This photo appeared on Rúv last week, with Benediktsson to the right and Gunnlaugsson to the left. The photo is taken by Svanhildur Hólm, Benediktsson’s adviser, during the coalition talks, at the summer house of Benediktsson’s father. Incidentally, both leaders come from wealthy families and having a summer house, as Benediktsson’s family does, on the shores of Þingvallavatn (the lake at Thingvellir) speaks of old wealth and status in Iceland. Later, the two leaders met at the country house of Gunnlaugsson’s father-in-law, a wealthy businessman. Having exhausted family houses outside of Reykjavík the leaders have then been meeting in the capital.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Iceland – back in growth but at the mercy of foreign markets

Under the demanding eyes of the IMF, the Icelandic Left Government turned the economy around – growth returned and unemployment went down. But Iceland is far from being on top of things. Both the sovereign and some of the big corporations have to meet tough payments in foreign currency in the next few years, several times more than the current account surplus. This gap can only be met with extended maturity and/or foreign loans. If the Icelandic Government is, at the same time, going to spirit money from the pockets of foreign creditors – in some cases the big banks that will most likely be asked for loans – it is difficult to see a happy ending to this saga.

“Iceland Chamber of Commerce recommends that Iceland stops comparing itself to the Nordic countries since we are way ahead of them in most respect.” Instead, Iceland should compare itself to champions such as Ireland, Cyprus and Greece.

This statement, from a 2006 report on “Iceland in 2015” was published by the Icelandic Chamber of Commerce, at a time when it seemed Icelandic bankers and the business leaders closest to them could both fly and walk on water. The matter-of-fact statement perfectly captures the hubris in the Icelandic business community during the few years of expanding financial sector and is often quoted to demonstrate the mind-set at the time. Most of the apostolic twelve who wrote the report are tainted by the collapse in October 2008 and one of them has been charged with serious financial misconduct.

Now, anno 2013 the outlook for 2015 is rather different. In 2015, Iceland needs to have at hand current account surplus of ISK120bn, €787m, in order to cover exposure of some large enterprises like the national energy company, Landsvirkjun and Orkuveita Reykjavíkur, the Reykjavík Energy Company, OR. At present, a realistic sum to expect is ISK30-40bn, €197-262m. The outlook for the three following years is similar. The situation is carefully explained in the most recent financial stability report from the Central Bank of Iceland, CBI (so far, only in Icelandic; expected in English this coming week).

Fish and aluminium are the largest components of Icelandic exports – and since both of these are finite resources, i.a. cannot be produced ad infinitum, it is out of the question that increased exports can cover the lack of funds. Something more is needed – and this “something more” should at best be some combination of extended maturities and borrowing.*

During the election campaign, the leader of the Progressive Party Sigmundur Davíð Gunnlaugsson told Icelanders that ISK300bn, ca. €2bn, could be wrenched out of foreign creditors of the two collapsed banks, Kaupþing and Glitnir, and distributed to indebted households – nota bene, not households struggling to pay, just indebted households, which are in fact mostly the best off households (the household debt is explained in a CBI report from June 2012). Fetching this money – never quite explained how (the estates are private companies, unrelated to the sovereign) – would be easy since the foreign creditors were in great hurry to get their money out of a country with capital controls. And consequently, the capital controls would be abolished pretty soon.

None of the other parties in Alþingi, the Icelandic Parliament, wanted to follow this path. Some critics pointed out this debt-relief paid out in cash, would only fuel the already too high inflation. However, this is the promise the Progressives are working on winning support for now that they are conducting coalition talks.

No matter the outcome, finding a way to abolish the capital controls as well as solving the lack of foreign funds is the largest, most complex and most pressing task awaiting a new Government in Iceland. There is no lack of ideas in the public debate, many of them utterly unrealistic bordering on the dangerous, often aired by businessmen who never declare their own personal interests.

But who is really in hurry – and what are the issues at stake? In short, Icelandic entities are under huge financial pressure. This pressure can only be solved by foreign loans – which have to come from financial institutions some of which are creditors to the estates of the two banks, Kaupthing and Glitnir.

The claims, the creditors and the “glacier bonds”

Roughly half of the creditors of Kaupthing and Glitnir – there is quite an overlap – are the original bondholders, most of them big financial institutions. The other half are investors who bought claims post-collapse. The division is not clear-cut – bondholders often put forth some of the financing as they sell the claims in order to have a stake in the possible upside.

The original bondholders lost ca. 5-6 times the Icelandic GDP – at present ca. ISK1600bn, €10bn – the moment the three banks folded. Their losses were no doubt greatly diminished by credit insurance and most likely many of them incurred little losses. Anecdotal evidence indicates that some large loans in 2007 from foreign lenders to Icelandic entities did indeed cause losses because the lenders could not sell them on as they intended to.

Just after the collapse, the claims were sold for a song but the price rose quickly. Much is made of the astronomical profit of the creditors, often called vulture-funds in the Icelandic parlance even by those who should know that vulture funds pray on sovereigns in or facing default (trying to squeeze the sovereign to pay its bonds in full), not creditors to private companies (where the value of the estate depends on the recovery). During the election campaign Gunnlaugsson stated that there was no harm in squeezing the creditors who all, according to him, had bought their claims at 95% write-down and consequently made so much money that they had to accept some write-down. Though far from true, this statement seemed music to the ears of the voters.

For the time being Icelandic experts on the issue think the price of the claims is too high. There is a great turnover in the market for Icelandic claims – one claim has for example allegedly been sold over 60 times – but that seems to have little to do with value and more to do with incentive-structures in funds dealing in claims. The Landsbanki estate recently seized the opportunity and sold its claims in Glitnir.

In addition to the creditors of Glitnir and Kaupthing there are the owners of the so-called “glacier-bonds” – bonds sold in the years up to 2008 to profit from high interest in Iceland. The largest issuer was Toronto Dominion.

The assets at stake – and the core of the problem: ISK assets owned by foreigners

The creditors own assets worth roughly ISK2500bn, ca. 150% of GDP, whereof ISK-denominated assets amount to ca. ISK800bn. The foreign part, ISK1700 consists of ca. ISK1000bn in foreign currencies, cash and roughly ISK700bn in foreign assets, such as stakes in retail, foreign property etc. The “glacier-bonds” amount to ca. ISK400bn. All in all, the ISK “problem” amounts to ca. ISK1200bn (and could well be ISK100-200bn more, depending on valuation etc).

When the split between the old banks and the new banks was effectuated, the old banks were made to lend assets to the new banks in order to make them sustainable. This means that the estates of Glitnir and Kaupthing own the new banks almost entirely, their stakes valued at ca. ISK250bn – the Icelandic state owns 5% in Íslandsbanki and 13% in Kaupthing.

Because of the Icesave problem, Landsbanki (owned by the Icelandic state) is in a category of its own. When the new Landsbanki was founded, the new bank got a forex loan worth ca. ISK350bn, from the old bank, which it has to start repaying in 2014 but the largest repayments come in four instalments, 2015-2018. The loan being a forex loan it is a forex liability and has to be paid back in foreign currency.

The general understanding amongst those working on these issues in Iceland is that the repayment problems rising from the repayment of the Landsbanki bond, as it is generally called, have to be solved first, i.e. before the problems related to the foreign creditors. Some extension might be possibly but it is essential for new Landsbanki to refinance the loan by borrowing, obviously in foreign currency, i.e. borrowing abroad.

The core of the problem is assets owned by foreigners in Icelandic króna, these ca. ISK1200bn (though of different origin, the Landsbanki bond is part of this sum) – because there is not enough foreign currency to pay out the ISK assets. Although the scale of the problem was not clear, capital controls were put in place – weirdly late, not until November 27, 2008, almost two months after the collapse. Until the CBI and the coming Icelandic Government have figured out how to secure an orderly solution – most discussed is some sort of an exit levy, a write-down through the currency rate or a combination of both – the capital controls cannot be lifted unless greatly jeopardising the financial stability in Iceland.

None of this is news to most of the creditors many of whom follow things in Iceland closely, i.a. by being part of “Informal Creditors Committees of Kaupthing and Glitnir,” the ICCs, represented by restructuring firm Talbot Hughes McKillop Partners and the law-firms Bingham McCutchens and the Icelandic Logos Legal Services. There is now also an ad hoc committee with members from the IMF, the ECB and Icelandic institutions to discuss various ways of solving these problems. The ad hoc committee is not part of the process of solving the issues but is expected to come up with thoughts and ideas, so sorely needed. – In the end, the CBI and the Icelandic Government will have to solve the problems related to the capital controls.

But the creditors do not only have an eye on their ISK assets – they are very much vying for getting hold of their foreign assets, worth in total ISK1700bn, whereof there is ISK1000bn in foreign currency, ready for picking. Since these are foreign assets in foreign currency, they do not affect the stability of the Icelandic economy. However, the CBI will hardly want to let go of these assets until it is clear how the ISK assets are dealt with and eventual haircut.

The feeling is that the foreign creditors are ready to accept some write-down on the ISK assets against getting the entire foreign assets. As in any other Western country, the creditors are protected by property rights – and should be rather sure of their right to the foreign assets. The ISK assets are more problematic – there is not the currency to pay it out.

Composition or bankruptcy?

During 2012 creditors in both banks worked on terms of the compositions of Glitnir and Kaupthing. Because of the capital controls the CBI needs to agree to the composition. Both estates had hoped to have the composition in place by the end of last year but the CBI was not ready to negotiate the final terms. The feeling is that the CBI wanted to wait until new Government was in place; there might be some Icelanders quaking in their boots at taking these vital decisions that will affect the Icelandic economy for years to come.

With changes to laws on capital controls, made just before the Alþingi went into recess, the CBI now has to confer with ministers. When new Government is in place this will be one of its first tasks. As to time, it is difficult to imagine this will go speedily. Once source said it could take as much as 5-8 years – and obviously the repayment of the ISK assets might stretch over a very long time indeed.

There are clearly huge interests at stake but there are wheels within wheels here. The creditors want composition, which means that the estates (now holding companies not banks) will operate in the coming years to maximise recovery of assets, most noticeably the stakes in the two new banks, Íslandsbanki, owned by Glitnir creditors and Arion, owned by Kaupthing creditors. According to this plan, the banks would be sold when good buyers were found. The CBI has aired the view that it would be best to sell the banks to foreigners, or at least for foreign currency, not króna.

There are forces at large in Iceland who have been airing the opinion that the two estates should be denied composition and instead should go into bankruptcy. A bankrupt company cannot own assets, meaning that the two banks would be sold right away at an accordingly low price. This is very much against the interest of the creditors and very much in the interest of whoever wants to buy a bank at a fire-sale price.

It is another saga but the idea of the two banks again being owned by a few Icelandic shareholders with controlling stakes makes me shudder. The battle for the ownership of the two banks will be the largest battle of interests and ownership ever to be fought out in Iceland, since the 13th Century.

The unmentioned interest group: Icelandic owners of offshore ISK

During the election campaign the Progressives, who wanted to fetch money from the creditors for the party’s generous promise of debt relief, made much of their claim that the creditors were in a hurry to get their money and run.

Surely they would no doubt want to see their assets soon but these are financial institutions and investors, many of whom have great expertise in the field of distressed assets and will be familiar with the circumstances, even with operating inside capital controls. There is nothing to indicate they are in such a hurry that they have no patience for negotiating. On the contrary, they have both knowledge and experience to deal with whatever problem is thrown at them.

The development of the ISK rate in the CBI auctions indicates that investors who bought “glacier bonds” are satisfied with the high interest rates in Iceland, compared to rates in Europe and the US. It is safe to say that there is no particular rush among many or most of the owners of “glacier bonds.”

Those who might be in a rush to release their offshore króna are Icelanders who happen to own ISK, either legally or less so. Some Icelandic businessmen have been drumming on about the importance of solving all these issues – and abolishing the capital controls – as soon as possible. Preferably by a big haircut on the foreigners and preferably by bankrupting the estates, denying them composition. These people no doubt have the decency of having the interest of the country at heart but it is less clear where their own personal interests lie. Some of these people are rumoured, in Icelandic media, to be special advisers to the leadership of the Progressive Party.

And now to the real problem: Icelandic current account surplus doesn’t cover repayments in the near future

Capital control, the ISK assets that need to be paid in foreign currency and the Landsbanki bond are problems that need to be resolved in conjunction. But quite apart from this, Iceland is facing serious current account drought – there is not enough foreign currency coming into the country to meet outstanding obligations of payment.

This is very clearly described in the latest report on financial stability from the CBI (my translation):

Domestic entities, others than the sovereign and the CBI, are facing large payments on foreign loans until 2018. The expected payments rise from ISK87bn 2014 to ISK128bn 2015 when the repayment of the Landsbanki bond will start with full force. For comparison, current account surplus in 2012 is calculated to have been ISK52bn. If the surplus remains similar in the coming years, as it has been in the past years, ca. 3-3.5% of GDP, other entities than the sovereign and the CBI need to refinance what amounts to ISK265bn until 2018.

The repayment of the Landsbanki bond is too heavy for the economy as a whole. Its maturity must be extended or it must be refinanced. Without extended maturity or considerable refinancing it is clear that there is no scope in the coming years for using the surplus to release ISK assets owned by foreigner. The interaction between abolishing the capital controls and the repayment of foreign loans is the greatest risk in the system.

Really, the risk facing the Icelandic economy cannot be stated more clearly than this. And for foreigners holding ISK assets this is bad news. Again, the creditors are highly aware of the situation – the dire situation.

Iceland has been seen as the first of crisis-hit European countries to recover. True, the economy is in its third year of growth and unemployment has peaked. But until these issues of refinancing payment obligation are safely solved, Iceland is not free of the problems that hit when the three banks collapsed in October 2008.

Now, it is also pretty clear who is in a hurry to solve the issue of refinancing debt – it is Icelanders themselves, the sovereign and others who need to repay debt in foreign currency. As pointed out in the CBI report, it is important – really of vital importance to the Icelandic economy – that foreign financial markets stay open for Icelandic entities. Arion recently borrowed money in Norway. But with interest rates above 6% this loan was more to show it could borrow than this being some sustainable solution. OR borrowed recently from Goldman Sachs but it only seems to be a facility stretching over 18 months – again, no sustainable solution. Until we see loans of 10 years maturity with sustainable interest rates the problems facing Icelandic entities are not over.

The sovereign only has debt of 58% of GDP, below the European average. We all know that Ireland, Greece and Cyprus had to turn to the troika when they lost market access. The frosty reality in Iceland is that among the creditors of Glitnir and Kaupthing there are big financial institutions to whom Icelandic entities will have to turn sooner rather than later for refinancing. Election promises to fleece foreign creditors will hardly pave the way for the kind of sustainable solution Iceland needs – and in the end, these promises could turn out to be much more expensive than just their nominal value.

*Here is a video from Bloomberg where Sigríður Benediktsdóttir director of financial stability at the CBI explains the situation.

DISCLAIMER: please observe that these are complicated issues. Certainly, none of the above should be taken as advice for any financial transactions.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.