Banque Havilland: a lost banking license and suspension of payment

After being fined for money laundering and other interesting chapters in the Banque Havilland story, it‘s come to this: Banque Havilland has lost its banking license. The story of David Rowland buying failed Kaupthing Luxembourg was always an intriguing one. This new chapter in Kaupthing‘s saga brings up earlies events. And it‘s a reminder how little has been done in Luxembourg regarding the Icelandic banks, the Lindsor case being a case in point.

In hindsight, two things regarding Kaupthing Luxembourg are interesting: the Kaupthing top managers were heavily involved in trying to keep the Luxembourg operation going and to sell it – and, when the criminal cases linked to Kaupthing surfaced in Iceland, it turned out that the dirty dealings were almost invariably organised and executed in Luxembourg.

Kaupthing Luxembourg was indeed sold, with a helping hand from Luxembourg authorities, which put in EUR320m loan, later repaid. Allegedly (lot of „allegedly“ in this story) former Kaupthing managers and big shareholders had tried to buy the bank in various ways but in the end, the buyer was David Rowland of Blackfish Capital.

Now, this saga of Kaupthing and its resurrection as Banque Havilland seems to have come to an end, according to a notice on Banque Havilland‘s website – the bank has been granted a suspension of payment by the CSSF after the ECB withdrew its banking license.

Financial warfare, breach of money-laundering and terrorism rules

After buying the failed Kaupthing, David Rowland, a businessman of a somewhat mixed reputation and friends with Prince Andrew set about moving the bank from corporate business to private wealth services. He kept the Icelandic staff until Kaupthing Luxembourg CEO was brought in for questioning in Iceland and later charged in more than one criminal case. Jean-Francois Willems, its present CEO, used to work at Kaupthing Luxembourg.

Havilland‘s first foreign investments were in Belarus and Iceland, fueling rumours that a new Kaupthing, i.e. with Icelandic ties, was in the making but that didn‘t really happen.

Given Rowland‘s reputation, some eyebrows were raised that in Luxembourg he was deemed to be a fit and proper person to own a bank. Under the Rowlands and some of his eight children – Jonathan, David‘s son was the CEO of the bank for years, other younger generation Rowlands also worked there – Banque Havilland courted controversy. In 2018, the Luxembourg regulator, CSSF, fined the bank EUR4m for non-compliance to law on money laundering and terrorism finance.

Only last year, the UK FSA fined the bank EUR10m for a rather crazy scheme, allegedly part of financial warfare agains Qatar. The FSA also ended three careers, of Edmund Rowland, who had been CEO of Havilland‘s London branch and two London colleagues, by banning the three of them from working in financial services, in addition to fining them.

The FCA considers that between September and November 2017, Banque Havilland acted without integrity by creating and disseminating a document which contained manipulative trading strategies aimed at creating a false or misleading impression as to the market in, or the price of, Qatari bonds. The objective was to devalue the Qatari Riyal and break its peg to the US Dollar, thereby harming the economy of Qatar.

Banque Havilland seems to have been set on distributing this document, but the scheme was never implemented. Yet, the FSA acted on it.

Now at the beginning of August came the final blow:

Banque Havilland S.A. (“Bank”) regrets that it has to announce the withdrawal of its banking license by the European Central Bank (“ECB”) as of August 2nd 2024 (“ECB Decision”) and the parallel request by the Commission de Surveillance du Secteur Financier (“CSSF”) to put the Bank under the regime of suspension of payments.

The Bank has decided to challenge the ECB Decision but will not oppose the application of the regime of suspension of payments which is intended to protect the interest of all parties involved and ensure a structured process moving forward.

Kaupthing and the Lindsor case

As I’ve pointed out time and again, the Luxembourg authorities have been fully informed on all Kaupthing investigations going on in Iceland. Investigations ending in jail sentences for some Kaupthing managers and shareholders. Early on, it was decided that one case re Kaupthing would be investigated in Luxembourg, the so-called Lindsor case. Lindsor was a BVI company, owned by some Kaupthing employees.

As I’ve reported on earlier, Lindsor allegedly bought bonds from Skúli Þorvaldsson, a Luxembourg-based businessman and a large client of Kaupthing, and from key employees on the “bank collapse day” 6 October 2008. On that day, the Icelandic Central Bank issued an emergency loan to Kaupthing of €500m, then ISK80bn – of these funds, ISK28bn were used in the Lindsor transaction, effectively moving this sum to Kaupthing insiders and Þorvaldsson (see earlier blogs concerning the Lindsor case).

For years, it seemed that the Lindsor investigation was moving on in Luxembourg, and as far as is known, the case was fully investigated some years ago and the prosecutor was finalising the last hurdles to bring this case to court. Since then, nothing, as far as is known.

This new development in the Kaupthing/Havilland saga might lead to some interesting information becoming available. In the meantime, search Icelog for my earlier reporting related to Kaupthing Luxembourg and Banque Havilland (see for example here).

PS For some reason, it seems impossible to read Icelog in the Chrome browser but it’s fine in Safari.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Luxembourg: a graveyard of financial fraud?

It’s now long since the fateful days in early October when the three main banks in Iceland collapsed, a story well told in an investigative report in April 2010 and on Icelog over the years. However, in Luxembourg untold Icelandic stories still loom, regarding Landsbanki Luxembourg and its equity release loans sold in France and Spain and an entity closely related to Kaupthing and its managers. CSSF, the Luxembourg regulator has kept its blind eye on these stories. But once in a while, the CSSF does rise to act, as a recent decision regarding the afterlife of an investment fund that went into liquidation.

For decades, equity release loans sold mainly to elderly people – often asset rich but cash poor – have caused problems in various countries. Problems, which were not spelled out by the agents, who sold these loans in France and Spain as agents for or on behalf Landsbanki Luxembourg. When the bank collapsed, following the collapse of the mother bank in Iceland, the investment part of these loans were wiped out.

It took the borrowers some years to find out that many of them were experiencing the same problems. The figures didn’t add up and the administrator, Yvette Hamilius, was unwilling to clarify to the borrowers what exactly their positions were. Borrowers claimed they were being told to pay not only what they money they had taken out but the whole loan, with the investment part being ignored. The administrator claimed the borrowers were refusing to pay.

In addition, there seems to be evidence that prior to its collapse, the bank didn’t invest the funds from these loans in an appropriate way.

CSSF: nothing to see, nothing to do

The borrowers have tried to have their cases investigated by the Luxembourg regulator, Commission de Surveillance du Secteur Financier, CSSF. CSSF has completely ignored the borrowers, in spite of a myriad of court cases related to Landsbanki in Iceland. Also, contrary to administrators of the collapsed banks in Iceland, the Landsbanki Luxembourg administrator allegedly never showed any interest in that side of an administrator’s role.

French authorities investigated Landsbanki’s operations in France in a very strange case, which the prosecutor lost. Strange, because it was investigated very differently from the way banking cases were successfully investigated and prosecuted in Iceland. In Spain, some borrowers have successfully thwarted the administrator’s attempt to seize their homes and houses while other cases have been lost.

In a recent French case related to a Landsbanki equity release loan, the Cour d’Appel d’Aix-en-Provence stated that Landsbanki Luxembourg didn’t have the license to operate in France, ie didn’t have the license to sell these loans but that didn’t necessarily change anything for the borrowers – sounds weird to a non-lawyer but that’s what the Court states.

CSSF did however start to investigate a company called Lindsor, related to Kaupthing’s managers and some of its largest shareholders. Already in 2019, Icelog reported that the case was allegedly fully investigated but that the Luxembourg prosecutor was dithering as to whether to prosecute or not. Long story short: nothing has been heard of this case. Yet another case where Luxembourg could have done something, had indeed spent time and man power on investigations but somewhere in the system, this case seems to have expired for good.

The sense is that in a lilliputian country like Luxembourg, which lives and lives well off its financial sector, safeguarding the sector and not those who do business with that sector seems of major importance.

CSSF: a tiny sign of life

In 2020, Icelog reported on how investors in a failed Luxembourg investment fund claimed the CSSF’s only interest seemed to be to defend the Duchy’s status as a financial centre, not investigate alleged misdoing within the Duchy’s financial sector. This story was mentioned as a parallel to the travails and tribulations of the Landsbanki Luxembourg borrowers.

Now in February this year, 7 February 2023, in a press release the CSSF stated that in December, it had indeed taken action in that case by imposing an administrative fine of EUR174,400 on the investment fund manager Alter Domus Management Company S.A. (formerly known as Luxembourg Fund Partners S.A.) which took over the administration of a fund, which went into liquidation in early 2017. Interestingly, investors in the funds in question, felt that not all had been well before the liquidation but that the administrator hadn’t paid any attention to their concerns.

The very brief CSSF press release doesn’t go into the details of what happened but the interesting part of the very brief press release is this: “During its investigations, the CSSF identified the existence of material and persistent failures – originating before the liquidation of the SubFund – to comply with the provisions of the Law relating to general requirements on due diligence, on conflicts of interest and in terms of procedures and organisation.”

From the point of view of the borrowers of Landsbanki Luxembourg equity release loans this is a striking parallel: something wasn’t right before the liquidation, something wasn’t right after it. However, the striking difference is that the fund story was investigated and fine imposed. As the CSSF states this followed an “ad hoc investigations carried out by the CSSF”. Sadly, no ad hoc investigation into Landsbanki Luxembourg and the Lindsor story seems dead.

Icelog has covered these stories extensively in earlier years. Curious readers can find them by searching for key words such as “equity release.” David Mapley has been investing the fund story, mentioned in an Icelog in 2020.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Andreas Georgiou and the eternal wait for justice in Greece

The case of Andreas Georgiou has again surfaced in the Greek media – a case that’s still unresolved, leaving Georgiou living with the same uncertainty as in the last decade, and potentially facing severe cost. His case is also a sad example of political corruption in Greece, the politically convenient disregard by EU institutions and the unwillingness of other EU politicians to express view on actions taken in other countries than their own – being too polite, as Mario Monti once said. Georgiou’s case also shows that civil servants, who are not whistleblowers, have little or no protection against corrupt politicians.

In autumn 2009, Greek authorities were found one more time to have falsified national statistics regarding the government deficit; this time the falsified accounts led to a massive debt crisis in Greece and the EU. In the following months, the statistics were corrected in several steps. The last bit was corrected in late 2010, by the then new head of ELSTAT, Andreas Georgiou, who had been headhunted from the IMF to oversee necessary changes at the Greek statistics office. That has turned into a legal nightmare for Georgiou, exposing political corruption in Greece and unwillingness to acknowledge what went on at the time before the Greek statistics were finally fully corrected. Georgiou has been persecuted but it beggars belief that the falsification of the statistics – who organised it and why – has never been investigated.

Over the years, Georgiou has faced a flurry of legal cases. Some of these cases have evaporated over the eleven years since investigations against him first began in September 2011. There are however still two ongoing cases against Georgiou: criminal conviction for violation of duty, now being tried at the European Court of Human Rights, ECHR, and a civil case for slander.

Recent coverage of Georgiou’s case in Greek media shows that the cases are not forgotten but yet, there is never any attention paid to the original sin in this case: the falsification of the Greek statistics that played its part in pushing Greece and the EU into financial crisis.

Waiting for the ECHR

In 2011, a criminal investigation for violation of duty was opened against Georgiou. This happened only a year after he was trusted to take office in order to put into practice European rules and regulations regarding public finance statistics. In 2013, he faced criminal charges for violation of duty. He was acquitted at the First Instance Court, but inexplicably that acquittal was annulled a few days later. In 2017, two years after he left office, Georgiou was convicted at the Appeals Court and sentenced to two years in prison, suspended unless there would be a second conviction.

The conviction related to not putting the revised statistics of the government deficit, from November 2010, to vote at the then board of the Greek national statistics office. By not doing it, Georgiou followed European rules: the statistics are the sole responsibility of the head of the national statistics office in any EU member state.

After the Greek Supreme Court dismissed Georgiou’s appeal case, Georgiou took the case to the ECHR on account of violations of his human rights by Greek courts in the process of convicting him for violation of duty. ECHR accepted to consider the case in late 2021. The Greek government was given the opportunity to voluntarily acknowledge that Georgiou’s human rights had been breached in this case.

So far, the government has not only not taken that opportunity, but it has submitted arguments to ECHR in May 2022 that there was no such violation and, effectively, that the Greek courts rightly convicted Georgiou. Greece now risks a condemnation by the ECHR as the latter adjudicates the case of Georgiou vs Greece. If Georgiou wins at the ECHR, then, according to Greek law, he would be entitled to be retried in Greece. While that might be a long process, it would give Georgiou – at least in theory – a path to exoneration in his birth country.

“The simple slander” – where statements found to be true can still be used against defendant

In the civil case Georgiou still faces, the plaintiff is Nikos Stroblos, former director of Greek national accounts statistics from 2006 to 2010 and notably still working at ELSTAT. The case refers to a press release Georgiou issued in 2014, when he was already finding himself subjected to criminal prosecutions, alleging that he inflated the government deficit figures so that Greece would incur extraordinary damages and be subjected to the EU supported economic adjustment programs.

Stroblos claimed that when Georgiou defended the revised Greek government deficit and debt data for 2006 to 2009 – a revision validated multiple times by Eurostat – it was damaging for Stroblos’ reputation. In 2017, a Greek First Instance Court found Georgiou liable for something called “simple slander:” that is, the Court ruled Georgiou had told the truth but by telling the truth he damaged Stroblos’ reputation. Georgiou appealed to the Appeals Court but lost.

Following the Appeals Court ruling, Georgiou was to pay Stroblos a compensation of EUR10,000 plus interest since 2014, in addition to paying Stroblos’ legal expenses and publishing large part of the court decision in the Greek newspaper Kathimerini, as a ‘public apology.’ A delay in publishing the apology would result in a fine of EUR200 a day.

In autumn last year, there was a court injunction against Stroblos enforcing the ruling. This case is now set to come up in the Greek Supreme Court in January 2023. The positive outcome for Georgiou would be to get the ruling annulled as the case would then have to be retried by the Appeals Court, possibly in 2024 or later.

The injunction means that Stroblos can’t, for the moment, seize assets Georgiou has in Greece, including the home of Georgiou’s mother, which is in Georgiou’s name. Consequently, not only is Georgiou facing serious financial threats by Stroblos but also his wider family. Although a retrial would be a positive outcome, since it gives Georgiou the possibility of exoneration in his country and – importantl – not losing his family’s home, it also means a continued legal fight for years to come, with no end in sight for the uncertainty for him and his family.

On whose side is the Greek government?

Greek politicians have often claimed – usually to foreign media – that they have nothing to do with Georgiou’s cases. The Greek court system is independent, they claim, as it should be in any democratic state.

That there has been no political interference can definitely be disputed – and as pointed out before: there has never been any political will to investigate the saga of the falsified statistics, which happened before Georgiou took office.

One indication of where the Greek government’s allegiance is in the case of the civil suit by Stroblos is that he has had financial support from the government for pursuing Georgiou in court. As previously reported on Icelog, the Syriza government, then in office, funded a significant part of Stroblos’ legal fees, which seems an abuse of the law under which the funds were provided.

The 2017 law was supposed to assist “current and former ELSTAT presidents” against legal actions arising against them. Instead, the Greek government perverted this intent and funded the misguided efforts of an individual, challenging the very statistics the ECB and Eurogroup sought to defend. A stunning perversion of the intended purpose of these funds, underscoring that the Greek government has funded, at least in part, an effort to continue the persecution of Georgiou.

In 2017, in the midst of Georgiou’s political persecution, the European Central Bank, ECB, and the Eurozone Finance Ministers had pressed the Greek government to provide funding to assist Georgiou in defending his statistics against the legal actions in Greece. As previously reported on Icelog, leaked minutes from the Eurogroup meeting 22 May 2017 show that ECB governor Mario Draghi had brought the ELSTAT case up at the beginning of the meeting, asking that, as agreed earlier, priority should be given to implementing “actions on ELSTAT that have been agreed in the context of the programme. Current and former ELSTAT presidents should be indemnified against all costs arising from legal actions against them and their staff.”

The answer from the Greek minister of finance Euclid Tsakalotos was that “On ELSTAT, we are happy for this to become a key deliverable before July (2017).” – Needless to say, the Greek government has not taken the action promised. Sadly, EU institutions have not pursued the matter.

On a visit to Washington DC this past May, Greek prime minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis of the now ruling New Democracy party was asked about Georgiou’s case. The question came up as the US State Department has pointed out Georgiou’s case (see here, under section E. Denial of Fair Public Trial) in its latest report on human rights. Mitsotakis said it wasn’t appropriate for him to comment on an ongoing legal case, but he would like to see it finished. Further, he claimed the Greek justice system had a structural and systemic problem; cases took far too long but his government was working on solving that problem (see here, 21:28-22:59).

It is worth noting that Mitsotakis made his comment just before his government submitted arguments against Georgiou in ECHR.

Although Mitsotakis is right about the slow workings of the Greek courts, that is not the main problem facing Georgiou. His case shows how the justice system has indeed been weaponised for political motives in order to persecute a civil servant who did his job.

International attention – recent coverage

It is rare that a public servant is prosecuted for doing his job. Georgiou’s case has over the years attracted international attention and been decried by professional organisations such as the American Statistical Association, the International Statistical Institute, the Royal Statistical Society, the International Science Council and others (see here, here and here for recent public statements and letters) .

At the same time, however, there has been deafening silence for a couple of years now from the side of the European Commission regarding the above two instances of obviously politically motivated legal proceedings against Georgiou. These cases used to be monitored and publicly commented on by the Commission in its quarterly reports (that were part of the post-program surveillance of Greece) until the end of 2019. However, starting in 2020, all mention of the persecution has been expunged from subsequent post-program surveillance Commission reports, for what can only be seen as political convenience. By doing this, the European Commission is planting the seeds for further problems for European statistics.

The case of Andreas Georgiou also draws attention to the fact that in many countries, also at a European level, regulation connected to whistle-blowers has been strengthened. However, persecuting civil servants for doing their job is rare. Subsequently, little attention has been paid to that danger in European countries or at EU level. Georgiou’s case shows that when this is the case, also at European level, there is little or no protection to be had.

*See here for earlier Icelog blogs on Georgiou’s case.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

The Georgiou case: from bad to worse, also for Greece

Parts of Greece are consumed by horrifying wildfires but in the Greek legal system there is a slow-burning fire exposing Greek corruption, linked to the Greek financial crisis of more than a decade ago. The relentless persecution of Andreas Georgiou is not only a personal matter but is part of a saga of political corruption and European weaknesses.

In autumn 2009, when the financial crisis in Greece was coming to the surface, Greece was found out, for the second time, of having falsified its national accounts, i.e. the statistics of national debt, deficit and GDP. When a Greek IMF statistician, Andreas Georgiou took over as the new head of ELSTAT, the Greek statistical office, the statistics had already been partly adjusted. It fell to Georgiou to make the final adjustment after he took office in August 2010.

In September 2011, an array of legal investigations of Georgiou and some of his colleagues were opened. The first criminal charges, for alleged inflation of the deficit and for violation of duty, by revising the previously falsified statistics, were brought in 2013. Later, cases against other ELSTAT staff were dropped but the legal case remaining against Georgiou is a civil case, where the plaintiff is Nikos Stroblos, director of Greek national accounts statistics from 2006 to 2010 and still working at ELSTAT.

Stroblos sued Georgiou for slander. Stroblos maintained that when Georgiou made a statement in 2014, defending the revised Greek deficit and debt data for 2006 to 2009 – a revision validated by Eurostat – it had been damaging for Stroblos’ reputation. In 2017, a Greek First Instance Court found Georgiou instead liable for something called “simple slander:” that is, the Court ruled Georgiou had told the truth but by telling the truth he damaged Stroblos’ reputation.

The Court ruled that Georgiou should pay Stroblos a compensation of EUR10,000 plus interest since 2014, pay Stroblos’ legal expenses and publish large part of the court decision in the Greek newspaper Kathimerini, as a ‘public apology.’ A delay in publishing the apology would result in a fine of EUR200 a day.

Georgiou’s appeal of the First Instance Court decision was rejected last winter by an Appeals Court. Now Georgiou has taken his appeal to the Greek Supreme Court. After his appeal was submitted to the Supreme Court, Stroblos presented Georgiou with a demand for immediately fulfilling the 2017 court decision: an immediate payment of EUR18,433 (the original EUR10,000 plus interest), to publish within fifteen days the excerpts of the court decision, with the EUR200 fine a day for any delay.

By the end of a year, this amount will be EUR73,000, rising quickly. If there is no payment in full of the award and any fines, the plaintiff can at any time seize funds or assets Georgiou has in Greece, including the home of Georgiou’s mother, whose home is in Georgiou’s name.

It is interesting to note that Stroblos made this demand two weeks after Georgiou had filed to the Greek Supreme Court a request for annulment of the Appeals Court decision in Stroblos’s case against Georgiou.

Political “heresies”

The Greek government is not an innocent bystander in this civil case. The government has given Stroblos financial support in his case against Georgiou. Georgiou put Greek national accounts in order. Stroblos was working at the Greek statistical office at the time of the falsified accounts. The Greek government has actively supported cases against Georgiou, a civil servant who did his duty in an exemplary way. The government has made no attempt at all to investigate who ordered the national accounts to be falsified and who then carried out that order, not just once but ongoing for about a decade before the final reckoning in autumn of 2009.

Greek political forces have pursued investigations and court cases against Georgiou with the relentlessness of the 17th century Roman Inquisition when Italian political and clerical forces at the time wanted the “heresy” of Galileo Galilei’s heliocentrism stamped out. At the centre of the Greek case is a political battle of corrupt forces holding on to a certain version of the saga of the Greek financial crisis.

As long as the corrupt forces are shown to be so relentless and so strong, Greek civil servants can’t be at ease in doing their job. They can’t be sure that the rule of law will protect them in doing their duty. On the contrary, the lesson they can draw from the Georgiou case is that should they inadvertently go against political interests, they can have years and decades of their lives blighted by legal wrangling with a state that isn’t there to protect correct procedures but to protect corrupt political forces.

As long as the Georgiou case is ongoing, Greece as a modern European democratic country is not in a good place. Human rights of a former public servant have been severely challenged in the Georgiou case.

Empty Greek promises to the EU

However, this story of relentless persecution of the former head of ELSTAT, does not solely touch Greece. It is also a matter for the European Union.

During his time as governor of the European Central Bank, Mario Draghi brought the Georgiou case up in a meeting of EU finance ministers in May 2017, as Icelog has previously reported. Leaked minutes from the Eurogroup meeting 22 May 2017 show that Draghi asked that Greece, as agreed earlier, took action to execute what had already been agreed in the EU programme for Greece: “Current and former ELSTAT presidents should be indemnified against all costs arising from legal actions against them and their staff.” Greek minister of finance Euclid Tsakalotos answered that “On ELSTAT, we are happy for this to become a key deliverable before July.”

This was July 2017 but so far, this promise hasn’t been delivered. The Greek Government indeed perverted the promise to assist “current and former ELSTAT presidents” in legal actions against them. Instead of aiding Georgiou, the provision was used to also fund the misguided efforts of Stroblos in challenging the very statistics the ECB and Eurogroup sought to defend. A shocking perversion of the purpose of these funds.

Statistics are a key tool in any modern country or organisation. Georgiou has had support from the European Parliament and from European and international statistical associations. The American Statistical Association, which has long followed the Georgiou case and supports him fully, has already reacted to this latest turn in the Georgiou case, asking for the persecution to end with a complete exoneration of Georgiou. ASA President Katherine Ensor points out that the latest turn “is also a clear message to Greek official statisticians not to speak up. All this is undoubtedly detrimental for official statistics, evidence-based policymaking and informed democratic processes, not to mention human rights of scientists.”

The European Union is dependent on sound national accounts and statistics from its member countries. It is very worrying that it has not taken a more decisive action in the Georgiou case. The work done by Georgiou at ELSTAT was guided by European Statistical System principles. By allowing Greek political forces to undermine this work and persecute a national statistician, the European Union is undermining its own statistics. The European Union should understand the importance of shielding civil servants in the member states against political forces, undermining the vital tool that statistics are.

*Icelog has followed the Georgiou case from 2015. Here is the last blog on the case, with links to earlier blogs.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

The Georgiou case: the ongoing decade-old shameful saga for Greece

Among foreign colleagues and international statistical organisations, the case of the former president of ELSTAT, Andreas Georgiou is a cause for grave concern. After Greece was found to have been falsifying its national statistics for years, Georgiou was appointed as head of ELSTAT to put Greek national statistics in order, which he did during his five-year term, 2010 to 2015. It is a sad sign of deep-running corruption in Greece, that even before his term had ended, Georgiou was fighting prosecutions from public bodies and later from private individuals linked to the Greek statistics before Georgiou took office. Yet, no investigation has ever been done into the real scandal: who organised the falsification of the national statistics in the years before Georgiou was appointed to put them in order?

The Georgiou affair is “a witch hunt, not a thirst for justice,” wrote Nikos Konstandaras columnist at Kathimerini in August 2017 in a rare show of understanding in Greece.

Investigations into Andreas Georgiou’s work started already in 2011, only a year after he took over as head of ELSTAT. The first criminal charges – for alleged inflation of the deficit and for violation of duty when Georgiou revised the previously falsified statistics – were brought in 2013; later there were criminal charges and a civil case for slander, ironically brought by the director of Greek national accounts division at the time the falsifications of Greek national statistics were ongoing. Intriguingly, the falsifications have never been investigated, nor those in charge of statistics at the time, only the public servant who put the necessary system in place to produce correct statistics.*5

The “simple slander” case: truth and punishment

In a civil case, brought against Georgiou by Nikos Stroblos, director of Greek national accounts statistics from 2006 to 2010, Georgiou was found liable by a Greek First Instance Court in 2017 for something called “simple slander.” According to the court decision, Georgiou’s statement in 2014, when he defended the Eurostat-validated revised Greek deficit and debt data for 2006 to 2009, was found to be true. However, it was also found to be damaging to the reputation of Stroblos. Georgiou’s appeal against the First Instance Court decision was – after repeated delays – ruled on by the Appeals Court in January this year and was rejected.

More specifically, in the 2014 press release Georgiou had defended the revised fiscal statistics of 2006 to 2009. In effect, he was defending the statistics produced under his watch, a revision of the statistics that the European Commission/Eurostat in 2010 and the European Parliament in 2014 had characterised as “statistical frauds.”

In his fateful statement, Georgiou was responding to the ongoing politically instigated prosecutions and attacks from most of the Greek political spectrum, on the revised statistics. Statistics, which had already been validated eight times since November 2010, when they were first published by Georgiou.

In his 2014 press release he pointed at both the repeated EU validation of the revised statistics and the EU verdict for the previous misreported statistics, asking why the courts did not instead investigate the previous period of the proverbial “Greek statistics.” Further he asked, why the court only invited those responsible for these misreported statistics, including the plaintiff, as the expert witnesses, and not also the EU officials of Eurostat mandated by law with assessing the quality of European statistics.

Georgiou lost at the first instance civil court level for stating the truth, as recognised by the court, and for defending the validated European statistics as he was required to do by EU and Greek law. He had a justified interest in defending the credibility of the newly reformed statistics office, ELSTAT, and he was exercising his human right of free expression.

The private cases against Georgiou by a former director of the Greek statistics office

The former director of the national accounts division of the Greek statistics office claimed that his reputation had been damaged by Georgiou’s press release. Yet, it was actually this director that had publicly slandered Georgiou and Eurostat as evidenced, for example, in an interview in March 2013.

The former director stated: “the wrong multiplier … is on account of the inflated statistics Georgiou sent to them … so with the inflation and alteration of the statistics they took from the [Greek] people more money than the country could bear! … the temporary postponement of the Greek bankruptcy in order to pay back in full the French and German banks … was the goal of the inflation of the deficit by the Greek Statistical Service following orders from Eurostat.”

Quite remarkably, the January 2021 Appeals Court decision rejecting Georgiou’s appeal omits any reference to this interview. Though repeatedly submitted as evidence to the Appeals Court and to the lower court, the Appeals Court decision claims that the plaintiff “had never expressed in the printed or electronic press accusations against [Georgiou].”

Meanwhile, the March 2013 interview with Stroblos was published again on 18 April 2021 as part of an article that celebrates the recent rejection of the appeal of Georgiou titled “New conviction of Georgiou of ELSTAT!!!” The April article highlights some of Stroblos’ public statements, such as “I refused to undersign the inflation of the deficit” and “Then [the Eurostat section chief] sent an expert … to persuade me to approve the changes [to the deficit calculation]. I refused! The work of the National Statistical Institute is to defend the interests of the country and not the interests of Eurostat!” – An altogether remarkable statement.

According to First Instance Court decision, Georgiou is obliged to both make a public apology, by publishing large parts of the convicting court decision in a specified Greek newspaper at Georgiou’s expense, and pay a compensation of EUR10,000, plus interest since 2014 and court expenses, to Stroblos. In addition, there is fine of EUR200 a day for any delays in publishing the apology. All this was upheld by the Appeals Court in its January 2021 decision.

If this January 2021 decision is appealed to the Greek Supreme Court, it seems that the Court can either return the case to the Appeals Court that Georgiou be tried yet again, a process that can potentially take three or more years – or the Supreme Court can, within months, irrevocably confirm the January decision against Georgiou. This means that there seem to be now only two possibilities left, one worse than the other. Georgiou has decided to appeal.

Political action running parallel to the two private cases against Georgiou

This civil case is an integral part of the overall political persecution of Georgiou in Greece. In the first instance, the case was brought at the same time as a criminal case for criminal slander, both brought by the same plaintiff, the two cases being intertwined. Former government officials volunteered and appeared as witnesses for Stroblos in both the civil case and the criminal case and the criminal case conviction[i] was cited during the civil trial.

The two cases were a combined criminal and civil broadside against Georgiou to undermine credible statistics. Common sense, as well as evidence of political intervention,[ii] indicates that these cases are part and parcel of the stream of persecution that has trailed Georgiou for accurately producing European statistics for Greece.

A closer look at the media coverage makes it clear that since 2011, the slander cases have been at the core of the attacks on Georgiou for heading and defending the revision of the 2009 deficit figures. Attacks, levelled by both major political parties as they alternated in power.

There is no lack of examples. Press reports (in Greek), at the time of Georgiou’s press release, titled “Dissatisfaction in Maximos Mansion [PM Antonis Samaras’ office] for the statements of the head of ELSTAT” noted: “the statements of the president of the Hellenic Statistical Authority, Andreas Georgiou, caused irritation at the Ministry of Finance and at the Maximos Mansion. Government sources stressed that “it is not appropriate for an administrator to express such judgments”. At the same time, Prokopios Pavlopoulos, a former top minister of the 2004 to 2009 New Democracy government and later president of Greece nominated by the SYRIZA government, initiated in the Greek Parliament Committee on Institutions and Transparency a successful vote, with support from both New Democracy and SYRIZA MPs in the Committee, to ask for Georgiou’s removal on account of his July 2014 press release but Georgiou’s removal was successfully resisted by Greece’s European partners.

It is hardly a coincidence that only a few weeks later, Stroblos filed his two suits against Georgiou. Stroblos not only used the above parliamentary committee’s decision as a pillar of his legal case. He has continuously been encouraged and tangibly supported by Greek political figures who have acted as trial witnesses and lawyers in his cases against Georgiou.[iii]

The trials of Georgiou for slander were used to publicly defend the pre-2010 government’s misreported deficit and debt statistics, to exonerate this past statistical fraud, and to attack the revised European statistics produced by ELSTAT under Georgiou in 2010 and repeatedly validated by Eurostat in the years since. For example, during one of the trials, a former General Secretary of the Ministry of Finance from the 2004 to 2009 Karamanlis government testified as a prosecution witness, among other things, that “in the period 2004-2009 no intervention in the statistics took place.” This patently false statement was highlighted and widely publicised in politically friendly press coverage of the trials.

The Greek government funds the plaintiff’s case against Georgiou in spite of its promise to the ECB

Quite shockingly, during SYRIZA’s time in government, the government funded a significant part of Stroblos’ legal fees, which seems a misuse of the law and a perversion of the original intent of the law under which the funds were provided.

In the midst of Georgiou’s political persecution, the European Central Bank, ECB, and the Eurozone Finance Ministers pressed the Greek Government to provide funding to assist Georgiou in defending his statistics against the legal actions in Greece. As previously reported on Icelog, leaked minutes from the Eurogroup meeting 22 May 2017 show that ECB governor Mario Draghi brought the ELSTAT case up at the beginning of the meeting, asking that, as agreed earlier, priority should be given to implementing “actions on ELSTAT that have been agreed in the context of the programme. Current and former ELSTAT presidents should be indemnified against all costs arising from legal actions against them and their staff.”

Greek minister of finance Euclid Tsakalotos said that “On ELSTAT, we are happy for this to become a key deliverable before July.”

Though crystal clear that this legal provision was to be specifically directed to assist “current and former ELSTAT presidents” against legal actions arising against them, the Greek government perverted this intent. The law was used to also fund the misguided efforts of an individual, challenging the very statistics the ECB and Eurogroup sought to defend. A stunning perversion of the intended purpose of these funds, underscoring that the Greek Government has funded, at least in part, an effort to continue the persecution of Georgiou.

Praise from foreign statisticians and organisations, persecution by Greek political forces

In stark contrast to the persecutions in Greece, Georgiou’s case has over the years had the attention of individuals and organisations all over the world: the IMF, the European Union, Eurostat, the American Statistical Association, the International Statistical Institute and the International Association for Official Statistics. All these individuals and organisations point out the gravity of the matter: that a public servant, involved in the gathering and processing of national statistics, the lifeblood of any modern state, suffers persecution for his work.

In early April this year, the German Süddeutsche Zeitung brought an article on Georgiou’s case, pointing out the support he gets abroad is the opposite of course of events in Greece.

It is also noteworthy that under the headline “Denial of Fair Public Trial” Georgiou’s case was mentioned in the US State Department’s 2019 and 2020 Country Reports on Human Right Practices. The 2019 Report stated:

Observers reported the judiciary was at times inefficient and sometimes subject to influence and corruption… On February 28, the Council of Appeals cleared, for the third time, the former head of the Hellenic Statistical Authority, Andreas Georgiou, of charges that he falsified 2009 budget data to justify Greece’s first international bailout. The Supreme Court prosecutor had twice revoked his acquittal by the Council of Appeals. Although technically possible, the current government has expressed no interest in revisiting the case. EU officials repeatedly denounced Georgiou’s prosecution, reaffirming confidence in the reliability and accuracy of data produced by the country’s statistical authority under his leadership.

The 2020 Report repeated the statement on the judiciary’s inefficiency and at times subject to influence. Further:

Observers continued to track the case of Andreas Georgiou, who was the head of the Hellenic Statistical Authority during the Greek financial crisis. The Council of Appeals has cleared Georgiou three times of a criminal charge that he falsified 2009 budget data to justify Greece’s first international bailout. At year’s end the government had made no public statements whether the criminal cases against him were officially closed. Separately, a former government official filed a civil suit in 2014 as a private citizen against Georgiou. The former official said he was slandered by a press release issued from Georgiou’s office. Georgiou was convicted of simple slander in 2017. Georgiou appealed that ruling, and at year’s end the court had not yet delivered a verdict.

Given where Georgiou’s case seems to be at, this chapter will still stand for the 2021 Report.

On May 1, Steve Pierson director of science policy at the American Statistical Association and Lynn Wilkinson from Friends of Greece, wrote an article on the AMSTATNEWS website, the ASA magazine, under the headline “ASA, International Community Continue to Decry Georgiou Persecution.” The article gives an overview of the persecution, including the still-ongoing slander case, and points out the false narrative that is being propagated by the continuous prosecutions, as opposed to the work Georgiou did to put in place the proper statistical methods, still the framework at ELSTAT.

Pierson and Wilkinson point out the US State Department’s mention of Georgiou’s case. “Besides the injustice of the prosecutions, the harm to Greece’s reputation, and the undermining of official statistics, Greece’s treatment of Georgiou is also a violation of Georgiou’s human rights.”

“Persecuting a scientific government official for doing his job with rigor and integrity to produce official statistics is deeply concerning,” ASA President Robert Santos said after the Appeals Court in January.

When will the political persecution of a statistician stop in Greece?

One reason Georgiou’s cause has gathered so much interest is the implications in so many countries for civil servants doing their job diligently. And that’s also why his case has been taken up by individuals and organisations. In a tweet March 24, Olivier Blanchard, ex chief economist at the IMF, now a professor emeritus at the MIT, wrote that what is happening to Georgiou is unacceptable. “Now in 10th year, Greece should end the injustice and exonerate him.”

As mentioned above, Georgiou will be appealing the January ruling to the Greek Supreme Court. At the time of the Appeals Court ruling he said: “Certainly, what happens in this case, when it reaches the Greek Supreme Court, will have implications in Greece and in the EU more broadly, for the soundness of future policies that are supposed to be based on honest and reliable official statistics but also for the rule of law, human rights and democracy.“

The implications from the January 2021 rejection of Georgiou’s appeal of the court decision for simple slander, where he was found liable for making true statements, seem truly staggering. How can democracy function when someone who participates in a public debate in order to refute false accusations of grave misdeeds and tells the truth, as the courts accepted he did, is then punished? The whole basis of democracy is free expression and communication of ideas and information for citizens to make their choices.

How can democracy survive when the state suppresses the free expression of ideas and information that are recognised by court as being true? And how can any good policy decisions be made for societies to prosper when truth is suppressed? Furthermore, how can science advance when truth is punished? Is it not evident that EU prosperity but also the functioning and the image of democracy in its realm are at stake? This case is a stain on Greece but a stain that also falls on the European Union, as Greece is a member state, inter alia reporting statistics to Eurostat. It is therefore worrying the EU and EU institutions have recently been silent on the Georgiou case.

[i] The “companion” criminal case for slander led to Georgiou’s conviction to one year in jail but was annulled by the Greek Supreme Court on account of serious legal errors and the statute of limitations did not allow the ordered retrial.

[ii] As an example, in response to Georgiou’s conviction in criminal court for “simple” slander, former Minister of Interior in the 2012 to 2014 New Democracy government, Mr. Michelakis, published an article entitled: “First conviction of A. Georgiou for the “inflated” deficit of 2009.” The article states: “The story of the inflated deficit of 2009 that was reported by George Papandreou and led our country to the Memoranda is beginning to be revealed through court proceedings, effectively vindicating the government of Kostas Karamanlis.”

[iii] Officials that served as witnesses at the trial for slander included George Kouris, former General Secretary of the Ministry of Finance, and Stephanos Anagnostou, former Viceminister to the Prime Minister and Spokesperson of the Government. Both served in New Democracy governments. The lawyer for the plaintiff was Yiannis Adamopoulos, the former president of the Athens Bar association, who had been elected to that post as a New Democracy party member and had played a major role as president of the Athens Bar in instigating the prosecutions of Georgiou about the 2009 deficit figures.

*Icelog has been following the Georgiou case since 2015. Here is an extensive overview, from April 2020, on the whole saga. Here is the first blog, from June 2015, which deals in detail with the statistics, the falsification saga and the adjustments that were made, the last one by Georgiou; this blog was also cross-posted with Fistful of Euros and The Corner. A shorter version was posted on Coppola Comment (thanks to Frances for the edititing!) and Naked Capitalism. – For numerous other Icelog blogs on the case, see here.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Greensill’s grand idea: close connections, jets and convoluted relationships

For anyone interested in cross-lending and cross-ownership, the collapse of the Icelandic banks provides insights into its effects: the meteoric growth and how opacity hides transactions between related parties, risk and debt within the ensuing complex structures, perfected by owning a bank as well. – All of this is well known to banks and regulators and should have caused concern regarding Lex Greensill’s operations. Yet, Greensill not once but twice had financial institutions – GAM and Credit Suisse – lending insanely against his debt, much of it growing around his dealings with the complex sprawl of companies related to Sanjeev Gupta and later with SoftBank. – Greensill, a consummate networker, made a strategic use of his private jets to woo and impress a small group of people who proved instrumental for Greensill in building up his business; some of them have not fared well.

Afterhours on 1 March, three Greensill companies – Greensill Capital Pty Ltd, Greensill Capital (UK) Ltd and Greensill Bank AG – respectively registered in Australia, UK and Germany, sought to force through an extension of insurance policies, worth US$4.6bn through an injunction at the New South Wales Supreme Court. Justice Stevenson refused the plea. After all, the Greensill companies had known since at least 1 September 2020, that the insurance policy would expire 1 March 2021 and yet did nothing until only days earlier.

On 5 March 2021, the court decision tipped all three Greensill companies – the mother company in Australia and its UK and German subsidiaries, as well as other Greensill companies – into insolvency, putting at risk 50,000 jobs worldwide with 40 Greensill clients.

In an internal recording of his address to staff 15 February, Lex Greensill, the founder of Greensill Group, claimed there was very good work going on regarding the insurance, which would even allow the firm to ramp up activity. – His reassuring words seem to run contrary to the New South Wales decision.

Indeed, why had Greensill Group done so little to have the policies extended? After all, Greensill’s operability relied on insuring the receivables of the invoices it sold on to investors: without insurance, no rating and without rating, no market for the invoices.

The Lex Greensill saga has many intriguing angles. He made good use of his Australian farming family, his “from farming to finance” saga. With support from former prime minister David Cameron and chancellor Rishi Sunak, Greensill’s relatively small company kept UK top civil servants remarkably busy, during the Covid crisis; a sure sign of Greensill’s consummate networking skills.

The Greensill Group went from a value of some hundreds of millions in 2017 to $4bn in 2019 and will leave losses in banking and the UK public sector amounting to billions of pounds. “It’s disturbing that yield-starved investors are still misjudging the dangers of exotic investment products more than a decade after the banking crisis,” Chris Bryant wrote on Bloomberg recently.

Disturbing indeed that banks and investors did not spot the flashing red lights: cross-lending, cross-ownership, the small-time auditors used by the Gupta companies and the mishmash of debt Greensill was peddling. – The Greensill operation is uncannily similar to the Icelandic model, which collapsed in 2008: own plenty of companies and a bank, deal with trusted friends and it all grows very quickly.

Intriguingly, a closer look at the Lex Greensill saga shows that a small number of people – in politics, insurance and finance – have been crucial to his rapid rise. His most important relationship was with Sanjeev Gupta and, in the end, with SoftBank and Masatoyshi Son, giving a particularly interesting insight into the SoftBank way of doing business.

2012: Greensill’s first UK stop: Downing street

In 2011, Lex Greensill, born in 1977, set up a fund, named after himself, in his home country, Australia, as a vehicle for his grand idea: a supply chain financing business. In the UK, Greensill set up Greensill Capital (UK) Ltd in July 2012. To begin with, nothing much happened.

One of the more bizarre parts of Greensill’s bizarre story is his relationship with the Tory-ruled Downing street. When working at Morgan Stanley 2005 to 2009, he bonded with a colleague, the late Jeremy Heywood, who in 2007 joined the Cabinet Office, when Gordon Brown became prime minister. In December 2011, it was announced Heywood would take over as Cabinet Secretary in January 2012. From September 2014 until he resigned in October 2018 for health reasons, Heywood was also “Head of the Civil Service.”

Heywood seems to have been Greensill’s key card to the Cabinet Office. In January 2012, half a year before he set up his UK company, Greensill had been appointed as an unpaid adviser on supply chain financing and stayed in that role until 2015. From 2013, Greensill was a Crown Representative until he left the Cabinet Office in 2016, then well into a blossoming business career.

There is however no contract, so it’s unclear who hired Greensill, what exactly he did and why he got a desk and security clearance, which allowed him to come and go as he pleased. Interestingly, Greensill does not list his Cabinet Office roles on his LinkedIn page, though he does mention the Commander of the British Empire he was awarded in 2017 for his services to the economy, though it is exceedingly hard to point out what exactly he had done for the British economy at the time. An honour also noted in his homeland.

While in Downing street, Greensill hired two other Downing street insiders: Bill Crothers and David Brierwood. Crothers, the government’s chief commercial officer, began advising Greensill Capital in September 2015 and left the civil service at the end of 2015 to join Greensill as a director where he stayed until February 4, 2021. His role at Greensill was known but seen as acceptable since Greensill had at the time no public-sector work.

David Brierwood is another ex Morgan Stanley banker and another Crown Representative at the Cabinet Office from October 2014 to June 2018 and a director of Greensill Capital (UK) from the beginning of 2015 until January 2018.

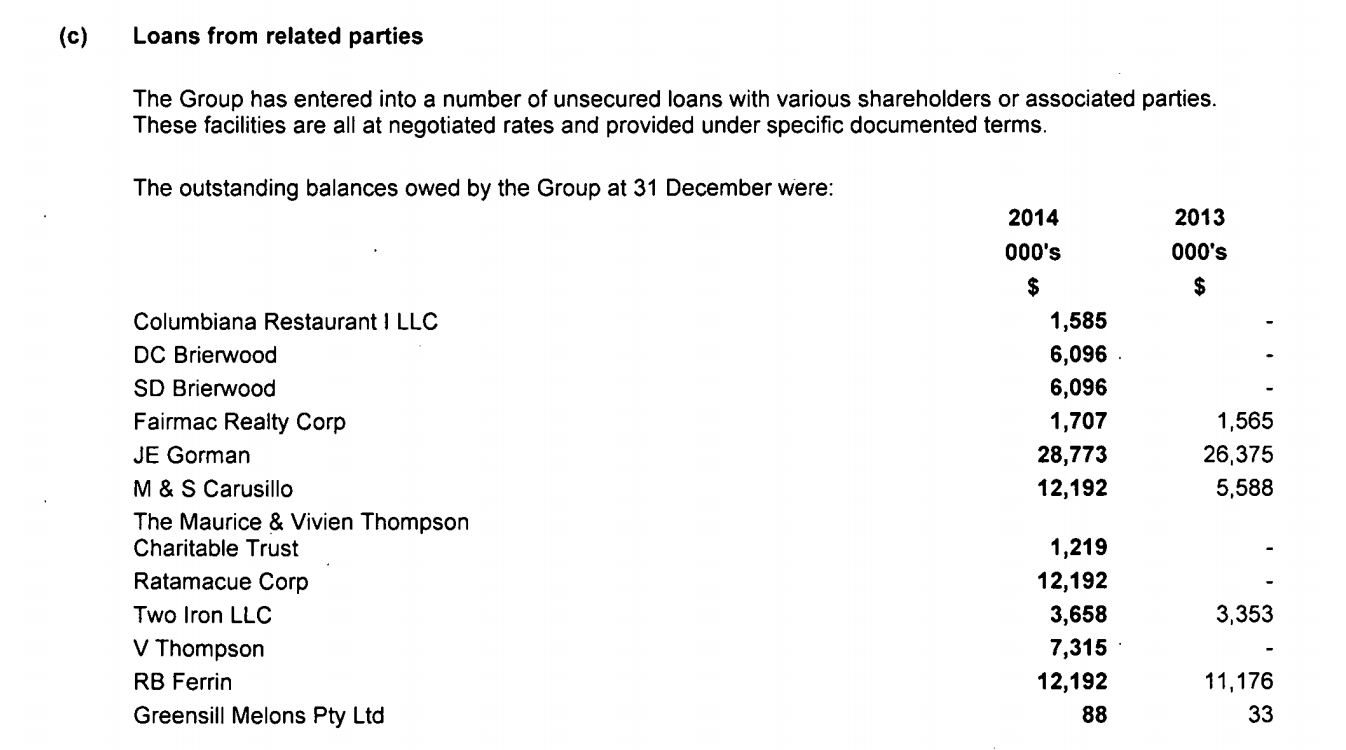

Brierwood was one of those insiders Greensill was carefully cultivating. As pointed out earlier on Icelog, Brierwood benefitted from a generous loan from the Australian Greensill company in 2014 of AU$6,096,000 with SD Brierwood (likely David’s spouse or other relative) receiving exactly the same amount; thus, loans to the Brierwood family amounted in total to AU$12,192,000. Other related parties profited from loans from Greensill. The revenue of the Australian Greensill company in 2014 was AU$38m.

The ultimate trophy asset: hiring a former prime minister

In 2018, David Cameron started working for Greensill, as is now well known. Cameron was untiring in travelling, taking meetings for Greensill and, when Covid-19 stopped all travelling and in-person meetings, he was equally untiring in messaging former colleagues in government, civil servants who worked under him during his time in Downing street and even foreign officials. Having Cameron acting on his behalf, was a major reason why Greensill was allowed to waste the time of top officials.

Apart from the grandeur of having an ex PM on the team, the Downing street insiders were precious, because Greensill was not only cultivating supply chain financing with businesses but also with the public sector. In addition to Brierwood and Crothers, Cameron would have been a valuable employee to have in dealing with the public sector.

Greensill and public sector contracts

Lex Greensill had his eyes firmly on public sector contracts for supply chain finance scheme. One scheme was set up in the UK, for pharmacists dispensing drugs for the NHS under the “Pharmacy Early Payments Scheme.” How much it earned Greensill Group is not clear.

Also, both in Australia and the UK, Greensill tried to set up a payday scheme for health workers, in the UK for NHS workers. He presented this as a sort of altruism, to be run through a wholly owned Greensill company, Earnd, set up in May 2018 but now in administration. Bill Crothers was one of Earnd’s directors. According to the Company House accounts available, this was never an operation of more than a few hundred thousand pounds, apparently financed by a loan from the mother company of almost £500,000.

The Corona Virus Business Interruption Loan Scheme, CVBILS, was administered by the British Business Bank. Greensill Capital (UK) became one of its trusted lenders. The UK firm used the German Greensill Bank AG to pay out the loans. Banks are not lacking in the UK and it’s difficult to understand why the BBB chose a bank for the scheme that could only administer loans in Germany. Possibly, political connections helped.

In the end, it seems that an abnormal chunk of the Greensill CVBILS lending went in the same direction at most other Greensill lending: to companies owned by Sanjeev Gupta.

Nick Macpherson, a former permanent secretary at the Treasury, recently told the Treasury committee, the intense engagement last year between top officials and such a small firm as Greensill was “unusual” and would have been a huge waste of time, a valuable commodity at a time of crisis. Paul Myners, former City minister, told the committee Lex Greensill had offered him a directorship. Myners refused, thinking after his meeting with Greensill that his operations had “many of the elements of a Ponzi scheme.”

Sacking of an insurance manager set the Greensill collapse in motion

An early key figure in Greensill’s business success was Greg Brereton, the insurance manager at Bond & Credit Company, BCC, now owned by Tokio Marine. In total, BCC underwrote A$10bn for Greensill, i.e. the accumulated figure for the accounts receivable of Greensill, not exposure to Tokio Marine. A clarification Tokio Marine gave after its shares tumbled following news in March of the insurer’s potential exposure to Greensill.

According to the 1 March New South Wales Supreme Court decision, Brereton was placed under internal investigation in May 2020 and dismissed in early July 2020. Two weeks after the dismissal, Tokio Marine first gave notice that Greensill’s insurance policies would not be extended. It can be said that Brereton was Greensill’s most important link but at the same time, the weakest link due to the concentrated insurance risk.

Intriguingly, David Cameron visited BCC on his trip to Australia in 2018 and met with Brereton. It’s easy to imagine what Brereton and the other 23 employees at BCC would have felt at meeting such a notable visitor. An example of Lex Greensill’s consummate understanding of networking and showing off his connections. He had a certain tendency to bigging up his connection: after meeting Barack Obama he apparently called himself an adviser to the US president.

The Gupta connection

The 1 March New South Wales Supreme Court decision tipped Greensill Group into insolvency with administrators appointed 8 March. But other ominous things had already been threatening the company.

On 2 March, before news of the Australian court decision broke, British Business Bank had removed government guarantee for Greensill’s CVBILS loans to Sanjeev Gupta companies. This followed an assessment of EY and law firm Hogan Lovells, finding that in lending to Gupta companies, the German Greensill bank had inadequate security. In addition, Greensill was facing insolvency after Credit Suisse had frozen $10bn investment funds linked to Greensill.

The British Business Bank was not the only one suspicious of the Greensill loans to Gupta. Already in early 2020, the German regulator BaFin, scarred and tarred from the Wirecard scandal, had started investigating Greensill Bank AG’s links to Gupta: allegedly, as much as two thirds of the bank’s lending was to Gupta-related companies. It is alleged that as much as $1bn was lent against insufficient collaterals.

Gupta had been investing in steel and metal for years, buying mothballed steel mills and small mills. In 2016, he had enough companies to set up the Gupta Family Group, GFG, apparently the year Lex Greensill and Gupta met in Australia. Since then, their operations have expanded at the speed of light, together and ever more intertwined, whether in creating debt instruments to create more debt for debt financing or meeting politicians.

At a dinner in Glasgow in June 2017, where they met with Scottish rural economy minister Fergus Ewing, Ewing spoke of the Scottish government’s positive experience of working with Gupta’s GFG.

Like a lender in a small village, Gupta in the global village likes doing business with friends, which has led to myriad of companies with an overload of cross-lending and cross-ownership. Interestingly, Gupta also owns a bank, Wyelands, which Gupta set up only in 2016. The Prudential Regulation Authority recently intervened and ordered Wyelands to repay its depositors, the first time the PRA has taken this action. It had discovered that Gupta’s bank mostly lent funds to only one client: Gupta.

There are other interesting aspects to Gupta: he mostly uses only a small auditor, King & King. It has an office in Wembley and in London: though among the shops on Regents street the office is far from fashionable. This tiny audit firm seems to have audited Gupta companies with combined revenues of almost £2.5bn. As long as Gupta doesn’t fulfil a promise from 18 months ago of comprehensible group accounts, there is no overview over his company sprawl, linked at it is to companies run by Gupta’s friends, employees and others connected to Gupta.

This sprawl of companies didn’t scare Greensill. He also liked doing business with related parties, as well as complexity, things that a financial firm should abhor. Given the complexity, it will not come as a surprise if the Greensill Capital’s debt exposure to the Gupta sprawl, turns out to be more than the $5bn it now stands at.

Greensill’s key contacts in finance: now mostly out of job

Tim Haywood had been jetted to Glasgow for the June 2017 dinner with Fergus Ewing. Haywood was at the time a fund manager at GAM, a Swiss fund set up in 1983 by Gilbert de Bottom, (father of Alain the philosopher). Greensill had introduced the two, Haywood and Gupta, in early 2017, after striking up a business relationship with Haywood in 2016. In total, Haywood would invest more than £2bn in assets Greensill sourced, much of it related to Gupta.

However, already in 2017 colleagues of Haywood were worried over his relationship with Greensill and Gupta, how Haywood was jetting around the world on Greensill’s jets and piling illiquid assets from Greensill, often linked to Gupta, into GAM funds. After internal probes, starting in November 2017, GAM concluded Haywood had broken rules regarding presents and entertainment, as well as rules on investing. Haywood was sacked in February 2019. The Greensill saga has marred GAM ever since.

Some of the GAM purchases were apparently quite out of the ordinary. One example is when Haywood orchestrated buying an entire issue of bonds issued by a special purpose vehicle called Laufer. Here, the transaction worked since the bonds paid the full amount, as Financial Times mentioned in an article on the GAM saga in March 2019, saying that Laufer had provided funding for Lex Greensill’s firm.

However, as can be seen from Company House documents, Laufer, a UK registered company, did not only provided funding for Greensill but was wholly owned by Lex Greensill, who was also one of its directors. According to Company House, Laufer has not followed other Greensill companies into insolvency and Lex Greensill is still listed as one of its directors.

The GAM saga ran in the financial media for months and yet, Lex Greensill was not out of luck. Next stop was Credit Suisse, where Greensill cultivated an executive, who has been much less visible than Haywood, Helman Sitohang, CEO of Credit Suisse Asia Pacific. Five months before Greensill Group collapsed, Sitohang had invited Lex Greensill as a special guest to address its Asia top staff.

At Credit Suisse Greensill apparently had another supporter, Lara Warner, then chief risk and compliance officer but ousted in early April this year. Against advice from risk managers, Warner agreed to a bridge loan of $160m in October, when Greensill failed to secure the $1bn in funding he had hoped for. Credit Suisse had funds stuffed with $10bn of Greensill sourced debt. Greensill’s collapse might cost the bank’s clients as much as $3bn.

Guided by common sense, it is wholly inexplicable how Credit Suisse, after the GAM saga, could enter into this remarkably cosy relationship with Greensill.

From a Softbank star to a falling star

Last but not least, there is Lex Greensill’s short, but sweet and crucial, connection to SoftBank / Vision Fund. Nothing of importance is agreed on at SoftBank without the blessing of its founder Masayoshi Son.

Apparently, a junior executive at the Vision Fund was the first to reach out to Greensill. In May 2019, clearly unperturbed by the GAM debacle, SoftBank invested $800m in Greensill Group, adding $655m in October, then valuing the company at $4bn. Quite a jump from General Atlantic investment of $250m and a value of $1.6bn the previous year. Son in known for liking big vision; Lex Greensill’s vision of a global working-capital market of $55tn was undeniably big.

Given that SoftBank is a serial investor, not all founders enjoy Son’s attention. Greensill though, was quickly enjoying the star treatment at SoftBank, with weekly calls from Son, invitations to SoftBank events where he would be favourably introduced and where he could express his gratitude at “having Masa as a partner and a mentor.” At Vision Fund meetings and presentation, Greensill’s name was often heard.

However, the SoftBank bliss was short-lived: in March 2020, only a month after an investment trip to Indonesia meeting dignitaries, where Son’s light shone warmly on Greensill, the relationship between mentor and mentee evaporated.

Investors were pulling money from the Credit Suisse funds, which had provided the lion share of Greensill’s funding. The phone calls stopped but in December 2020, when Greensill was running out of cash, SoftBank did invest further $440m. However, it seems the cash wasn’t ultimately destined for Greensill though there are at least two stories on where it ended.

One story is that the cash was earmarked for the Credit Suisse funds stuffed with Greensill-sourced debt but did instead go to the German Greensill Bank. Another story is that the cash was meant for Katerra, a Softbank portfolio company, financed by Greensill but with Greensill struggling found itself also in a dire situation.

There is another story of SoftBank’s funding going in an unexpected direction. With the first SoftBank funding for Greensill, the $800m, Greensill’s message was that the funding would be used to develop new technology and expand the invoice financing. Instead, it seems it mostly went to bolster the German Greensill Bank. The question is if SoftBank thought that was a great idea or if it was not informed.

SoftBank and Son do indeed both like size and complexities, one reason why helping Greensill grow rapidly was to SoftBank’s liking. SoftBank hooked some of its own portfolio companies into the Greensill lending carousel.

Financing hypothetical future sales, not actual invoices

The SoftBank connection brings us to the core of Greensill’s business, which eventually became a nail or two in its coffin. The Greensill Group vision was, according to its 2019 annual accounts “to make working capital faster, cheaper and easier to access for businesses of all sizes. We accelerate the movement of cash to where it is needed most, in the real economy.” Acceleration is exactly what Lex Greensill took to new heights, for his own group.

Greensill’s grand idea was invoice discounting or supply chain financing: companies and notably governments around the world pay their invoices from suppliers or service providers within 90 days or more. From the point of view of those who are invoicing, getting paid quickly will lower working capital cost.

Therefore, invoicing parties can be more than happy to accept an offer of 97 or 98cents/pence a dollar/pound, a standard offer from an invoice financing company. The math is simple: if you invoice the government or a company for £100, you are owed this sum. You can then sell your invoice to someone like Greensill for 98p today, instead of waiting for 100p to up to 180 days, or even longer if the invoice isn’t paid on time or at all.

In a market of growing complexities, Lex Greensill was known for very complicated structures and very complicated products. And he had the reputation for being a brilliant salesman, making good use of his “from farming to finance” story. The kind of a salesman who could sell sand in Sahara, or very complicated structures and products where there is no lack of such things.

Being a brilliant salesman created one problem: not getting enough invoices. Consequently, in his drive to accelerate, Lex Greensill seems to have been fine with invoices for non-existing goods or services. Utterly insane, says one source; it made no sense to issue debt to companies for invoices, which might or might not later come into being.

Matt Levine explains this really well on Bloomberg’s Money Stuff. Bluestone is a coal mining company that in mid March, sued Greensill Capital (UK), Lex Greensill and Roland Hartley-Urquhart, Greensill’s vice president, alleging fraud, thereby opening a window into Greensill’s operations, showing a novel and audacious interpretation of “future receivables” – it was so much future that it was based on completely hypothetical transactions that Bluestone hadn’t even contemplated might happen.

These transactions on a hypothetical future seem to have been to SoftBank’s taste. So, Greensill allegedly provided financing to some SoftBank companies based on predicted future sales, not on issued invoices.

SoftBank invested in the invoice-financing funds Credit Suisse set up around Greensill’s products, the ones that attracted $10bn from investors, which then lent to SoftBank portfolio companies such as Oyo, Fair Financial Corp. and Katerra Inc., creating an intriguing loop. However, this did at some point go too far for Credit Suisse, which saw a conflict-of-interest for SoftBank in this carousel. SoftBank agreed to pull $700m out of the funds.

These future transactions invoices apparently also proved a loop too far for Greensill’s insurers, which brings us back to the March 1 New South Wales Supreme Court decision. As far as I understand, these future invoices were a major issue for the insurers; slightly too much of a froth to insure.

Greensill’s taste for convoluted relationships

Gupta is not the only one who likes doing business with friends. Greensill’s relationship with Andy Ruhan is a good example of his penchant for close and convoluted relationships.

Ruhan, recently in the UK media because of a divorce row – one of these millionaire divorces where the wife claims, and seems to be right, that the husband is concealing assets. Ruhan pops up in a chapter of the Greensill saga where Greensill-sourced assets are causing major problems for investment funds, once so greedy for Greensill assets, i.e. GAM and Credit Suisse.

The assets in question was debt related to Ruhan’s property investments in New York, a good example of how Greensill, although claiming to be a straightforward invoice financing firm, was in reality a debt peddler able to sell whatever he picked up. Here, it clearly didn’t hurt to have a jet to fly people around in: Greensill-jetting Tim Haywood at GAM had bought the debt, although GAM property experts had advised against the purchase.

The Ruhan connection appears to go far back in Greensill’s operations: when Lex Greensill started buying up the German bank, NordFinanz Bank in 2013, then naming it Greensill Bank AG, it turned out that surprisingly the property and hotel investor Ruhan owned a sizeable stake, 26.19%, in this little local German bank. No price given but “for deferred consideration to be determined based on the future enterprise value of the bank.” The transaction is mentioned in Greensill UK 2013 annual accounts, Ruhan isn’t identified by name but has been named later as a previous shareholder in the German bank.

The strategic use of jets and connections

In order to understand Lex Greensill’s modus operandi, it would be interesting to study the flight records of his four jets. Records show for example David Cameron’s use of Greensill’s jets. Greensill paraded Cameron around when Cameron, freshly hired by Greensill, visited Australia in 2018.

The jets seem to have been a Greensill strategy from early on to impress and woo possible business partners and, for Greensill, important people. In January 2015, Greensill Bank AG came handy: according to Greensill Capital UK, the German bank bought a used Piaggio P-180 aircraft, for nine passengers. At this time, Greensill was still in Downing street and the revenue of the Australian Greensill company in 2014 was only AU$38m. – Later he added a second Piaggio.

In 2018, Lex Greensill had various lucky breaks: he got a $250m investment from General Atlantic and hired an ex prime minister. That called for a celebration: that year, Greensill bought a $22m Dassault Falcon 7X. The following year was even better as millions turned into billions with the $1.5bn investment from SoftBank and a valuation of $4bn. He upped his air fleet, with Gulfstream G650, listed at $50m.

With the first Piaggio, the German bank leased the plane to Greensill Capital Management (IoM), listed in the 2014 accounts as an associated company of the Greensill Group. The same arrangement might have been used for the three other jets.

Last November, shareholders in the privately held Greensill Group complained over the group’s many aircrafts and demanded that the planes be sold. The jets neither looked good from an environmental perspective nor did it fit with the planned fundraising of $500m to $600m and further, an IPO planned within two years.

The use of jets figures in stories related to others whose goodwill Lex Greensill found it worth to cultivate. As mentioned earlier, Tim Haywood, the GAM fund manager, was a frequent flier on Greensill’s jets and proved exceedingly important for Greensill during the strategic years of climbing towards ever more sales of his debt.

The flight records of Greensill’s four jets, would no doubt show quite clearly who were his most strategic connections.

Greensill’s strategic use of sponsorship

Lex Greensill also treated Tim Haywood to events in high places. Greensill was awarded Commander of the British Empire in 2017, presented to him by prince Charles. As pointed out earlier, Greensill’s contribution to the UK economy, for which he got the CBE, was minuscule. That same year, Greensill Capital sponsored a concert at Buckingham Palace with the Monteverdi Choir and Orchestra. Lex Greensill invited Haywood but who Greensill’s other guests were is not clear.

By sponsoring the concert, Greensill was helping in several ways. One of the directors of the Monteverdi Choir and Orchestra at this time was David Brierwood, one of Greensill’s Downing street connections, who became a Greensill director. As pointed out earlier on Icelog, Brierwood benefitted from a generous loan from Greensill in 2014 of AU$6,096,000 with SD Brierwood (allegedly David’s spouse or other relative) receiving exactly the same amount.

It was all quite neat: Greensill had Brierwood as a director of Greensill, gave him a generous loan and sponsored the orchestra, where Brierwood was a director – and got a gig at Buckingham Palace, where he could then invite people who were important to his business. – In addition to flight records, it would be really interesting to see the guest list at the Palace concert.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Greensill’s 2014 private loans to related parties