Archive for June, 2010

Icelandic Tory ties: Rowland, Spencer and Yerolemou

David Rowland, the owner of Blackfish Capital UK, has been named the treasurer of the Conservative party. Through their ownership of Banque Havilland Luxembourg David and his son Jonathan are almost household names in Iceland. But there are other intriguing Tory connections to the Icelandic banks, notably Kaupthing.

David and Jonathan Rowland, or rather their investment company Blackfish Capital, took over the Kaupthing operation in Luxembourg last year and turned it into Banque Havilland. Havilland draws its name from the family’s Guernsey address, the splendid Havilland Hall. Father and son firmly deny any connections to the owners of Kaupthing but they held onto Magnus Gudmundsson until he was taken into custody due to the Kaupthing investigation in Iceland. The Rowlands have stressed that house searches at the former Kaupthing premises in Luxembourg earlier this year were unrelated to Banque Havilland. It is of interest that Martyn Konig, a well merited banker who had worked for Blackfish, resigned as a chairman of Havilland almost as soon as it opened.

Earlier, the Rowlands weren’t bothered neither over the Kaupthing investigation in Iceland nor in the UK – and yet, it’s been clear for a long time that the Kaupthing Luxembourg operation was central in all the deals and connection that are being investigated, be it the al Thani case or loans to UK business men such as Kevin Stanford and Robert Tchenguiz. It’s interesting to notice that al Thani is of the Qatari ruling family. Recently, a court case in London showed that a Qatari company bowed to pressure from Prince Charles. Christian Candy who won that case was also one of Kaupthing’s clients and a partner in joint ventures with the bank.

A source close to the Havilland informed me earlier this year that the Rowlands were interested in private banking and had been looking for a bank to buy for some time. When the Libyian Investment Authority’s offer for restructuring Kaupthing was turned down by the bank’s creditors and JC Flower’s rumoured interest didn’t materialise the Rowlands stepped in to buy the bank. The good assets were put into Havilland and Pillar Securitisation took over the bad assets, administrated by Havilland.

Unexpectedly, the Rowlands and Blackfish are also a well-known name in Latvia. When the renowned newspaper Diena was sold last year it seemed at first that Latvian businessmen with previous ties to the paper were buying it. Then it turned out they didn’t really have that kind of money and in the end the real owners came forth: Blackfish and the Rowlands. Why they suddenly wanted to own a newspaper in Latvia seemed hard to explain – and hasn’t really been explained except the Rowlands say they won’t interfere with the editorial line. That didn’t satisfy the Diena journalist: most of them left the paper and have now founded a new paper.

David Rowland moved from Guernsey to England in 2009 to be able to donate money to the conservatives. He has donated £3m, is now the party’s major donor – and that qualifies him to be the next party treasurer when Michael Spencer steps down in autumn. Now that the Conservatives are in government Spencer isn’t quite the kind of name they want to be linked to. Spencer has long had a reputation for being rather unsquemish when it comes to ways to make money. Last December, Spencer’s company Icap made $25m settlement with the US Securities & Exchange Commission, following a four years investigation, to escape charges for using fake trades to encourage customers to trade.

But Spencer’s company Icap was also a broker in the UK and did business with the Icelandic banks. Butlers, Icap’s financial consultancy, advised its customers, i.a. many of the UK councils, to keep their funds with the Icelandic banks even though the rating agencies, unbelievably late, downgraded the banks. Consequently, the councils that used the advice of Butlers lost badly and lost more than those who had other or no advisors. A possible conflict of interest has been alleged but strongly denied by Icap and Spencer. But the owner of a company that used fake trades would certainly have found a common ground with the Icelandic banks that are now being investigated i.a. for market manipulation.

Interestingly, the incoming and the present treasurer of the Conservative party aren’t the only conservative high-fliers with Icelandic connections. Tony Yerolemou is one of the Tories important donors and has been over the years. The Cypriot food producer was one of the owners of Katsouris Food, sold to Bakkavor in 2001. He got very close with the Bakkavor owners Lydur and Agust Gudmundsson who eventually became Kaupthing’s biggest shareholders. – And mentioning the Rowlands: as administrator Pillar is claiming back a Kaupthing Luxembourg loan to Lydur who might lose his £12.8m house on Cadogan Place if he can’t refinance his loan.

The Rowlands might also have to pick over their fellow conservative Yerolemou who not only sat on the Kaupthing board but had huge loans with the bank through Luxembourg. When the bank collapsed Yerolemou was one of the bank’s biggest debtors, his loans through Luxembourg amounting to €365 (whereof £203m were unused). The report of the Althingi Investigative Commission concludes that because of the loans and because his companies were firmly in red Yerolemou hadn’t been fit and proper to be on the bank’s board. Together with Skuli Thorvaldsson Yerolemou was involved in companies organised by Kaupthing and partly financed by Deutsche Bank to influence Kaupthing’s CDS spread. Yerolemou has been the chairman for Conservatives for Cyprus – and interestingly, the Conservative party had pledged before the election to give Cyprus priority when the party would be in power. Yerolemou has donated money to the campaigns of various MPs, i.a. Theresa Villiers now minister of State for transport and who also very much has the interest of Cyprus at heart.

Apart from ongoing investigations in Iceland the Serious Fraud Office is conducting an investigation into Kaupthing. With the conservatives in power and the particular ties that some conservatives have had with Kaupthing it will be of great interest to see what happens with the SFO investigation. It’s also interesting to see if authorities in Luxembourg make a move to look more closely at the Kaupthing operation in Luxembourg.

Who would have guessed there were so many Icelandic ties to the Conservative party? There are many stories to follow here.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Jon Asgeir Johannesson seeks release from freezing order

Jon Asgeir Johannesson is seeking a release from Glitnir’s freezing order. In May the Glitnir winding-up committee got an international freezing order at court in London. According to sources close to the case Johannesson in now trying to have the order thrown out. It’s not known yet when the case will come up.

Freezing orders are what lawyers call a ‘nuclear option’ and are, consequently, hard to get. The freezing order was made around the time when the GWC brought out charges against Johannesson, his wife, Palmi Haraldsson and other business partners and ex-Glitnir bankers in New York, demanding back some $2bn. It was also around that time that the GWC passed on material to the Office of the Special Prosecutor in Iceland relating to alleged fraud committed by Johannesson and others before the collapse of Glitnir in October 2008.

A freezing order is only effective if it’s passed without the knowledge of the person hit by it. With a freezing order assets can neither be sold nor made use of in another way. The defendant only gets access to a limit amount of his money to meet everyday expenses.

If a defendant is able to get a release from a freezing order the claimant can be liable for damages done. That means that should Johannesson be successful in getting a release the GWC might be liable to paying damages to Johannesson. This is however part of the equation before demanding a freezing order. No doubt, Glitnir’s legal team has taken this risk into account.

An international freezing order is often issued when the person in question has assets abroad and offshore – certainly the case with Johannesson whose web of companies is both intricate and complicated. In considering if the defendant should escape the freezing order the judge will i.a. consider earlier behaviour of the defendant, i.e. if he has shown the will to co-operate.

One of the companies no doubt hit by the freezing order is JMS Partners, registered in the UK. The owners are Baugur’s ex-CEO Gunnar Sigurdsson and House of Fraser chairman Don McCarthy, who has been close to Johannesson’s UK ventures. The third founder was Piano Holding, a company registered in the Cayman Islands, earlier the holding company for the yacht that Johannesson bought in 2007 with a loan from Kaupthing Luxembourg. Since earlier this year Johannesson figures as the third owner of this company. The freezing order will most likely hit this asset.

Following the freezing order Johannesson was obliged to hand over to the GWC a list of his assets. He’s done that but the list is a very closely guarded secret. The myriad of companies related to company groups in the Johannesson’s sphere indicates that searching for his assets might prove a time-consuming process. Luckily, the experts at Kroll, working for Glitnir, are involved in it – and tracing and recovering assets will be part of their expertise.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Entangling the Jon Asgeir Johannesson’s sphere

The charges brought against Jon Asgeir Johannesson, formerly of Baugur Fame, and his closest business allies in Reykjavik and New York and the international freezing order from a London court all relate to an empire so complicated that it’s staggering that any one person could have commanded over it all. It kept an army of lawyers and accountants busy. Now it’s quite a task for the administrators of Baugur in Iceland and the UK, of other Johannesson related companies and for the resolution committees of the three Icelandic banks, as well as foreign creditors, to entangle the web, trying to understand how money and assets were moved around. In an interview some years ago the UK retail tycoon Sir Philip Green, whom Johannesson was no doubt trying to eclipse, said he had never seen anything as complicated as the companies related to Johannesson.

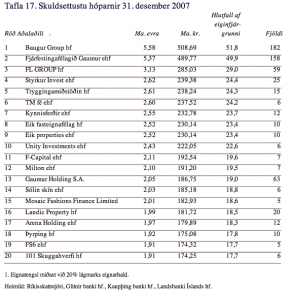

A table in the report of the Althingi Investigative Commission tells a striking story of the complicated web of companies. This table shows the most heavily indebted company groups at the end of 2007:

Out of these 20 companies 18 (!) are closely related to Johannesson:

Baugur, Fjárfestingafélagið Gaumur, FL Group, Styrkur Invest, Tryggingamiðstöðin, TM fé, Eik fasteignafélag, Eik properties, Unity Investments, F-Capital, Milton, Gaumur Holding, Sólkin skín, Mosaic Fashion, Landic Property, Arena Holding, Þyrping, 101 Skuggahverfi. Quite a number of accounts to sort out.

However, the column farthest to the right is interesting as it throws light on the structure of the groups in the Johannesson business sphere. It shows the number of companies related to these groups: 607 (!) companies are related to the 18 companies in the Johannesson sphere.

These loans, at the end of 2007, are not the whole loan saga since this covers only loans from the Icelandic banks. Foreign debt related to Johannesson’s companies isn’t included.* Add to that the fact that at the end of 2007 debt related to Johannesson personally was €1,5bn.

It’s clear that from early on Kaupthing was heavily and intimately involved in financing Johannesson’s companies. Landsbanki was also a diligent lender, not only to the companies but also to Johannesson’s private consumption, i.a. the flat at Gramercy Park where no collaterals were asked against a loan of $25m. Until lately, he seems to have had this flat for his personal use. And then towards the end it was Glitnir that was, according to the charges brought in New York, practically raided by Johannesson, ‘a convicted white collar criminal’ and ‘a cabal of businessmen’, his closest business partners.

The lingering question is how it was possible for one man to borrow all this money – it’s important to note that the loans were issued against a myriad of companies that by all means didn’t all do well but were continuously bought, sold, sliced and diced, sold and resold.

The continuum of quicksilver movements was one of the means to keep the merry roundabout going attracting ever more loans – and it’s now one of the reasons why it’s so time-consuming and complicated to entangle the web to figure out where the assets are and what the real status of Johannesson is. A lawyer close to one of the debtors told me that figuring out where his personal assets are is proving to be quite a task; it would be more simple if he were personally bankrupt but that’s not the case. Not yet, at least.

The sad thing is that all this money has mostly evaporated, not only because falling asset prices but also because the investments were simply not very clever. Johannesson didn’t turn out to be quite the business wizard made out to be: those who know him say he has an uncanny eye for retail – but he reached far beyond retail. The staggering trail of debt tells the story of lost opportunities and hubris. In an interview yesterday on Icelandic radio with Olafur Hauksson from the Office of the Special Prosecutor in Iceland Hauksson indicated the Johannesson’s affairs are now being investigated. Again, that is quite a task as the table above indicates.

*Earlier today, I had added the debt of the companies in the Johannesson sphere together. However, that doesn’t give a correct overview of the loan status since the loans do, in some cases, overlap.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Cameron reminds Icelanders of the unpaid Icesave bill

Icelanders have to pay the Icesave bill. In a statement yesterday to Parliament on the meeting last week of the European Council PM David Cameron stressed that ‘this country should be a good friend to Iceland and a strong supporter of continued EU enlargement. But Iceland does owe the United Kingdom £2.3 billion…We will use the application process to make sure that Iceland meets its obligations because we want that money back.’

There have been some speculation in Iceland that the Tories might have a different view on Icesave than Labour and the, for Icelanders, mean Gordon Brown. Some months ago I heard from a leading Conservative that his party shared Labour’s stance on Icesave so I wasn’t surprised to hear Cameron’s words. What some Icelanders fail to understand is that there are no UK political interests aligned with the Icelandic interests on not paying. In the UK, Icesave is an unpaid bill, not a cause that the voters are worried about or interested in. Neither are the politicians except they want their money back.

Cameron’s words haven’t gone unnoticed in Iceland. Some even think this was a diplomatic blunder of great dimensions that will only strengthen the opposition in Iceland to EU membership. That’s a rather crude view since Icesave is an issue that needs to be resolved while a EU membership is about very long-term interests, not about paying or not paying for Icesave.

The fact is that Iceland owes £2.3 billion to the U.K. and €1.3 billion to the Netherlands as compensation for depositors who lost money in the collapse of Internet bank Icesave. The Icesave saga is turning into a long one – no wonder that the UK government wants to use all possible means to solve the issue. What would Icelanders do if they were owed money by a nation that had gone back and forth on its words on paying?

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Hubris and the demise of the ‘currency-basket loans’

A major factor in the Icelandic expansion of banks and businesses abroad was the belief held by these expanding forces that they had important qualities and ways of doing business that outdid foreigners. Time and again, Icelandic bankers and business leaders said that their way of doing business was something others could learn from. Olafur Ragnar Grimsson president of Iceland was a diligent propagator of this thesis of the Icelandic business Übermench. Grimsson eventually formed a theory of thirteen key characteristics that made Icelandic banks and businesses so good at conquering the world, most eloquently explained in a speech in May 2005. The collapse of the three Icelandic banks, a large part of the Icelandic financial sector and many of those businessmen who formed part of the Icelandic financial elite has seriously undermined the validity of this theory. Interpreting this belief through the Icelandic sagas ‘hubris’ is a better explanation – after hubris comes the fall.

The recent ruling of the Icelandic High Court on the so-called ‘currency-basket loans’ is another chapter in the story of the Icelandic hubris. Instead of doing something to properly strenghten the economy and fight inflation the created a byway, linking loans to low interest rates abroad by issuing loans to individuals and companys that were set up as loans in foreign currencies but were actually in Icelandic kronur. This has now been ruled an illegal form of loans by the Icelandic High Court: it’s illegal to tie interest rates to foreign currencies when the loans aren’t really in foreign currencies.

A source familiar with the situation pointed out to me that the ruling is yet another ‘thumbs down’ for the Icelandic banks. These loans could easily have been set up so that they would have complied to Icelandic law. It was just a matter of wording the loan contracts more precisely. If the legal departments of the banks had done their job properly and the managers of the banks had been alert to the importance of working out the details, acknowledging that the devil is in the details, and leaving no issue unexplored this wouldn’t have happened. Not only did the banks mess up things abroad. They didn’t do a brilliant job at home either.

There were from the beginning critical voices regarding the currency loans – but the banks seemed to have ignored them, probably thinking it was good enough to function. Rather like the BP employee who wrote in an email when BP cut corners drilling the now so infamous well in the Gulf of Mexico: “Who cares, it’s done, end of story, will probably be fine.” – Relying on the ‘probable’ can be a damaging and dangerous strategy.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

EU membership: The striking lack of Icelandic enthusiasm

Today, the EU leaders didn’t only agree on a new pan-European bank levy. The Council of Ministers also agreed that the membership negotiations with Iceland could now begin. No Icelandic minister was present in Brussels today. June 17 is the Icelandic national day, the tradition is that the prime minister addresses the people on that day. That’s what PM Johanna Sigurdardottir did today instead of going to Brussels like the Norwegian PM Jens Stoltenberg who media-wise made the most out of his visit. But the national day doesn’t explain why the Icelandic minister of foreign affairs couldn’t be in Brussels today.

The Council also expressed hope that the Icesave dispute would be resolved. It’s clear that without an agreement on Icesave a EU membership is impossible. It’s still over a year until an agreement will be crucial but it’s a timely reminder that at one point or another the matter has to be resolved. In an interview with the daily Morgunbladid president Olafur Ragnar Grimsson said that his stopping the Icesave bill in Althingi, the Icelandic parliament, had been the wise thing to do and had strengthened the Icelandic position in Icesave. Others will beg to differ – as long as there’s no agreement in place it’s unclear if Iceland really has gained from the delay.

Now that the EU membership negotiations can start the lack of political leadership on the issue is striking. The opinion polls show a dwindling support for an Icelandic EU membership – according to the latest polls 58% are against membership – reflecting that there isn’t any political enthusiasm at all for membership. Last summer, Althingi agreed to formally apply for a membership indicating there was an interest – but that interest has since evaporated.

Having followed the debate on EU membership in Norway, Sweden and Finland in 1994 when Norway, for the second time, turned down membership and Finland and Sweden joined, I can only say that there was, at the time, a huge momentum around EU in these countries. In Iceland there is nothing, simply nothing. And when voices are heard they are usually negative. Those who preach that Iceland will lose its national characteristics can be heard loud and clearly. Those who think Iceland belongs in Europe because it’s already part of the European Economic Area and should be a fully paid up member of the union either don’t speak up or wait and see.

Now, just as so long as I can remember, there are those who claim that Iceland is so special that it can only follow its own rules. These are usually those who think it’s fine that Iceland profits from international fora but shouldn’t be tied or obliged or committed in any way. Iceland tried to run its bank in a particularly Icelandic free-style. It didn’t end well. The emphasis on Icelandic superiority rings both false and hollow to my ears but it’s an underlying current in much of the political debate in Iceland – a very strong and prominent current found in some corners of all the political parties.

The Social democrats, now leading the government, are in principle pro-EU and have driven the EU agenda but without much conviction. The Independence Party is split on the issue – and since that party was in power during the 90s and well into this decade this party is largely responsible for preventing the European co-operation ever to become an issue for the best part of the last twenty years. As the other Nordic countries voted on the issue the IP decided that the EEA was good enough for Iceland. The Progressive Party has been split on the issue and consequently fairly silent on Europe. The Left-Green, in coalition with the social democrats, are against but have bowed to going through the process of applying, ultimately resigned to a referendum on the issue.

In 1997 I interviewed the historian and diplomat Sergio Romano. He said that nothing would change in Italy until there were enough Italians in power who had been abroad and learned that there are other ways of doing things than just the Italian way. There are plenty of Icelanders who have lived abroad but it seems that as soon as they move back they are more than happy to do things the Icelandic way.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

The Icelandic High Court: ‘currency-basket loans’ are illegal

One of the reasons so many Icelanders have been badly hit by the collapse of the Icelandic banks and the simultaneous collapse of the Icelandic krona is that for years a big share of mortgages and car loans were linked to foreign currencies instead of the krona. Today, the Icelandic High Court ruled that tying loans to the value of foreign currencies was illegal. Loans in Iceland can only be linked to the domestic currency, the krona. The two cases related to car loans issued by two financial companies specialising in these loans but the same principle is thought to apply equally to ‘currency-basket mortgages,’ another popular form of currency loans. According to figures from the Icelandic Central Bank ISK125bn, £660m, in car loans and ISK225bn, £1,3bn, worth of mortgages are currency loans.

The loans were usually a selection, or a basket, of different currencies, hence the name ‘currency basket loans’ – often a combination of yen, euros and dollars. This flight to foreign currencies was a move by the banks as the Icelandic interest rates steadily got higher and higher, to combat the rising inflation.

Interestingly, the ever-higher interest rates didn’t take the pressure off the system and the inflation steadily crept upwards – also because so much of the lending was done outside the realm of the krona and the Icelandic interest rates. Consequently, interest rates close to 20% didn’t punch the inflation down but had the adverse effect of luring foreign capital into Iceland making the krona ever stronger.

In principle, it’s a huge risk to take out loans in a currency that’s unrelated to your source of income. For example a teacher in Iceland with all his or her income in krona and no exposure to other currencies shouldn’t really take out a loan in euro yen and dollars to buy a new car. With more than 10% difference in interest rates and the loans indexed (i.e. moving with the inflation) many people thought this was a risk they could live with: even if the krona lost some value it wouldn’t hurt except in the case of a massive and highly unlikely devaluation. With a krona steadily gaining strength from 2003, when these loans started to crop up, by 2005 it seemed that the krona couldn’t be anything but strong and the loans really took off.

As the banks collapsed in October 2008 so did the krona. Repayments of currency loans doubled or even more. Even prudent borrowers woke up to sky-high debts, in some cases higher than the value of the assets they had borrowed against. This has often been most noticeable in terms of cars: people might have borrowed five million krona to buy a car that now is worth only 3 millions and the loan is at 10 millions – clearly not a good situation to be in.

While the going was good, the krona strong and the interest rates low on the currency loans they seemed a good deal and no one complained. As the collapse in 2008 changed all that there were voices claiming that actually it was against Icelandic law to tie interest rates to a foreign currency. Even more so since those who took out the loan took it out in krona, i.e. no currency changed hands. The currency rate was only a point of reference but the loan wasn’t actually in any currency but the Icelandic krona.

Today, the High Court confirmed what many suspected: loans in Iceland can only be connected to the domestic currency. However, the High Court didn’t rule on the interest rates nor what should substitute the currency link. The banks claim they are already well on their way in solving this issue and that they already have a firm grip on it. The government says the same: that it had already had planned for this eventuality. There are however some financial companies that have mainly operated on currency loans and they might now go bankrupt. The two cases that the High Court ruled on today were related to loans taken out with two such companies.

The government now has two problems to solve: firstly, how to calculate the currency loans now that the currency link isn’t valid anymore; secondly, how to hinder a bias against those with indexed loans in Icelandic krona. Since it’s been known for a while that the High Court ruling was imminent and that this outcome was likely (an earlier ruling had indicated what could be expected) the government has had time to prepare. Having already had to refinance the banking sector it remains to be seen if the loan companies will need to be bailed out and if they really should be bailed out. Many debtors with currency loans will see the ruling today as a vindication of their struggle to meet repayments – anything that smacks of the government robbing people of their victory will most likely be met with great anger.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

The dark stain of Kreppa

By guest contributor Michael Schulz. A social scientist who has worked for 30 years as a humanitarian manager in development, natural disasters and conflict on missions for the Red Cross in Africa, Asia, the Middle East, Russia and Trans-Caucasus and was i.a. based in Ramallah for two years. The last 5 years Michael was a diplomat with a Red Cross delegation in New York, accredited to the UN. – His Icelandic connection is through his partner who gives Michael an ‘Icelandicness’ and the authority to speak of Iceland though seen through his European eyes. Michael takes a keen interest in all aspects of the ‘Kreppa’ (Icelandic for ‘crisis’) in a philosophical, historical, political, socio-economic and cultural context.

Isn’t it amazing: the Icelandic elites are being pilloried. Former large shareholders and CEO’s of banks, so called banksters, amongst them many who also owned large chunks of the Icelandic economy and media, politicians, members of parliament, “political” ministers, governors of the Central Bank, et al are being critically targeted by the special prosecutors, social media and the general public, not least the voters in elections.

At long last the big players and not merely the bystanders seem to be held accountable. Their criminal acts, corruption, un-ethical and immoral deeds have finally rendered them “vulnerable” to justice, both legally and politically.

Of course, the vast majority of the vulnerable are all those who had fallen victim to manipulation (some might call it marketing) by banks that had for example talked them into high risk, outright toxic credits, indexed or foreign currency loans, to buy property they couldn’t afford or luxury cars they didn’t need. The property prices were based on virtual not real value; the limousines and sports cars were unnecessary as there are no real highways to drive them in Iceland.

These are the people who did not so much lose illegitimate fortunes but ill-aspired affluence transcending Icelanders general prosperity. True, all could have been sceptical and questioned the origins and legitimacy of all those unexpected riches. Instead they indulged in a frenzy of consumerism, with luxury brands topping the lists.

But, it has to be said, being excluded from the elite’s exclusive circles it was near impossible to see through the bubble or net that had been cast over the entire society. Economists, the experts, for example, didn’t see that the bubble was about to burst – did they? Regulatory authorities did not provide oversight – did they? Besides, the ideological climate and a policy of laissez-faire was such that the excesses ruled over balanced supply and demand.

All in all up to 35% of Icelandic households are seriously hit by debt. Some will manage thanks to remainders of their former prosperity. Icelanders are a resilient people. But others will become the newly poor as opposed to the nouveaux riche.

Then there are the vulnerable, the people who did not lose ill-aspired affluence but lost a livelihood as they were on the fringe of relative prosperity and social security. They are poor.

The poor they are not one iota concerned whether their poverty is measured in relative or absolute terms. Their poverty is not only one of socio-economic terms as they lost employment or are a single parent or are elderly or old. For many poor their status is aggravated by personal, physical and/or mental adversities. And their social status is such that they are deprived of coping mechanisms.

Nowadays food security is an issue for many Icelanders. The charity Fjölskylduhjálpin alone (there are also a number of other charity organizations) provides between 400-500 families, roughly 1200 individuals, with weekly food rations. That’s about triple the number compared to before the crisis. The charity is still not able to serve all those who apply for assistance.

It is difficult to assess the number of families and individuals in need of immediate humanitarian assistance. Understandable albeit false shame and pride prevent many to register as there is social stigma attached. But, be it seems a reasonable estimate that 10000 families, 27000 individuals, now live in dire straits in Iceland.

Funding and donations in kind do not cover needs. Without volunteers recruited from amongst the beneficiaries the charity couldn’t function. The premises from which Fjölskylduhjálpin operates – ironically the historical location where the now bankrupted supermarket chain Hagkaup was started – have to be rented from Reykjavik City for annually ISK 1.2 mill. – almost half the annual amount (ISK 2.5 mill.) the City grants the organization.

To date, just over one and a half years into the crisis, it seems depressions or suicide rates are not on the increase. But in Iceland, with a population of just over 300 000, eventual trends might start on a miniscule scale, detectable and readable only over time. By contrast, psychiatry and psychology practitioners today report a significantly increased “pressure”, as more people seek help because of i.a. anxieties, fear, stress and anger.

Iceland is a small nation. Perhaps its national pride or misguided chauvinism when one hears there are needy and poor but(!) they are only very few and official welfare helps!

One wonders: Does it make a difference if the poor are only few? What about the proportionality of figures or are about 27000 individuals or almost 10% of a population of roughly 300 000 enough?

Welfare helps? Of course it does. It better does. But is it a generous gift from society or authorities? Isn’t it a “natural” entitlement, indeed a human right!?

Quantifiably, today’s monthly welfare support stands at about 125 000 ISK (leaving aside inflation, tax increases, etc.). Quantifiably, it has also been established that in today’s Icelandic society one requires monthly ISK 180.000 – ISK 220.000, say, rounded up and down, ISK 200.000 to make a living.

ISK 200.000 minus ISK 125.000 thus leaves a balance of ISK 75.000.

ISK 75.000? Yes, this amount marks the dark stain on the downside of Kreppa!

The authorities have argued social security can’t be increased because there was no money in spite of and because of millions being spent to repair a criminally wrecked financial sector and turning around the economy. How much do only the negotiations around the Icesave case cost in – say – salaries, legal fees, travel costs, mounting interest rates, etc.?

Besides, if the poor are the few, isn’t ISK 75.000 only a low sum per individual per month – compared to spending billions elsewhere?

There is no upside to the downside of Kreppa – except perhaps the return to social values, family, friendships and knitting. But there are the poor and that dark stain. The authorities should recall the ethical and moral failings of the past. They should understand that any society is only as strong as its weakest member and they should seek to wipe away that stain.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Searching the bankers’ soul – through their salary schemes (Glitnir)

What did the managers and key bankers really think about the operations they were running? ‘Well, they clearly didn’t trust the banks because it was all about getting as much money out of them, via salaries and bonuses, as possible,’ a source close to one of the collapsed banks said to me recently. Bankers’ bonuses has been an international media topic for the last many years – both the numbers and the inbuilt incentives – but in this, as in so many other fields, the Icelandic bankers were well ahead of their foreign colleagues when it came to unreasonable claims and general lack of stringency. Out of the many, Glitnir offers some striking examples: Glitnir’s ex-CEO Bjarni Armannsson got Glitnir to pay him ISK380m when he left the bank in 2007, based on a contract that expired in 2006. A property company registered in his wife’s name owned a house in London and rented it out to Baugur, already then one of Glitnir’s biggest client.

The report of the Althingi Investigative Commission throws a revealing light on i.a. the lending practices, the financing of the banks and their internal and external auditing and is an endless source of illuminating material. But no chapter gives a more profound insight into the thinking of the managers of the banks than the report’s chapter on salaries and incentive schemes: the top bankers were generous in handing out the banks’ money to the small clique of major shareholders – and they weren’t stingy either when it came to their own salaries. Let’s focus here on Glitnir.*

In 2000 a merger of Islandsbanki and FBA, an investment bank, formed Islandsbanki-FBA. The CEO of FBA Bjarni Armannsson, the ‘golden boy’ of Icelandic banking and already famous for his high salary, was named the CEO of the new bank. As the report points out the management’s salary schemes were frequently changed, always for the benefit of the management but against the interest of the bank and its shareholders.

Armannsson brought with him the ‘Economic Value Added’ scheme from FBA but already in 2003 there was a deviation from that scheme in his own salary. In general, the rules weren’t stringent and changes were frequent. A change in 2004 made an end to deferred bonuses – whatever Armannsson got was his, no matter how the bank did. In 2001 Armannsson had made a contract based on options that then expired in 2006 without him making any use of it. When he was planning to leave the bank early 2007 he insisted that is should be honoured. The remuneration committee didn’t even have a copy of the contract and wasn’t too keen on letting Armannsson exercising his rights according to the expired contract. Armannsson’s suggested solution was a cash payment of 370m, the same as the contract would have given him but that wasn’t accepted.

After a bit of to and fro Armansson did indeed walk away with 380m. He also got premium on other shares – and did in the end leave the bank with just over ISK1bn that could be seen as a golden handshake. After the collapse of the bank Glitnir’s resolution committee claimed the final salary payment was illegal. Facing a threat of being brought to court Armannsson decided to repay in total around ISK1bn and make no further claims.

From 2004-2007 Armannsson’s average monthly salary rose from 9m a month to 50m a month, in other words it rose more than fivefold. In 2004 his bonus amounted to 1,8m a month but had reached 9m a month when he left the bank in 2007. But he also had a lucrative business on the side. When Glitnir ventured into the mortgage market Armannsson’s wife, a nurse, set up a property company, Landsyn, with loans from Glitnir. Amongst the properties in Landsyn’s portfolio was a house in a gated community in Richmond where many Icelandic bankers and businessmen lived. The house, valued at more than £1m, was rented out to Baugur already in 2006 – so while Baugur was one of Glitnir’s biggest clients the CEO’s wife was Baugur’s landlady. The Icelandic media has reported that in spite of Landsyn being registered under the name of Armannsson’s wife he himself ran the business.

When Jon Asgeir Johannesson, Palmi Haraldsson and Hannes Smarason – the FL Group cabal – became the major shareholders in Glitnir in spring 2008 they brought about drastic changes in the bank, also regarding remuneration. In 2004 the 10% of staff with the highest salary got around 30% of salaries paid in total by the bank – in 2007 this group got over 45% of all salaries at Glitnir.

Already from early on key employees got loans from the bank on highly favourable terms to buy shares in the bank. As frequently encountered in the Icelandic banks the loans were made out to be ‘risk free’, i.e. the risk was all on the bank not on the borrowers, the covenants were absurdly lenient, the interest rates outrageously low and the only collaterals were the shares themselves. The new board wowed to put an end the loans but that didn’t turn out to be the case at all. Two key employees were even given loans where part of the loans was paid out as dividends as soon as the shares were bought: one employee got a loan of 480m whereof 150 went directly into his pocket – another got a loan of 1bn with additional 150m paid out.

The employee loans escalated over the years – and it now seems clear that this sale of Glitnir’s shares, planned by the bank’s management, was organised market manipulation, comparable to similar but possibly even more extensive ‘parking of shares’ by Kaupthing. In both banks the aim was to make the banks immune to the swinging mood of the market. At the end of 2007 the loans amounted to 17% of the bank’s own capital.

The new owners of Glitnir brought in Larus Welding who had been the head of Landsbanki’s London office. Compared to Welding’s salary Armannsson turned out to have been poorly paid. Welding’s average monthly salary in 2007, including the golden handshake, was 84m out of which 4m was his salary and 80m bonuses. At that time a senior civil servant, i.a. a permanent secretary could expect to get around ISK700.000 – so Welding, at the time 31 years old, got paid the equivalent of 120(!) senior civil servants.

So what was the job that Welding was so well rewarded for? Emails published in the report and charges brought by Glitnir’s resolution committee show that Welding was essentially a private cashier for the new clique. Johannesson and Haraldsson were continuously on-line with harsh demands. At one point, Welding complained he was being treated like a branch manager, not like a CEO.

Although Armansson had been unrestrained when it came to his own salary the running of Glitnir under his management was more conservative than both Landsbanki and Kaupthing. The major shareholders during Armannsson’s time – one of Iceland’s old families famous for political power and unostentatious wealth joined by the much more aggressive Wernerson’s brothers – didn’t have the bank and its CEO in their pockets as did the FL cabal.

No doubt inspired by the fantastic success of the high-interest Internet accounts of Landsbanki and Kaupthing, Glitnir’s new owners aimed at the same lucrative market that Welding was already familiar with from London. But they entered the game too late, the international wholesale funding was dwindling and with the crisis hitting the Icelandic banks early on plans to set up the Internet accounts didn’t materialise. In addition, the new owners were so aggressive that Glitnir was the first of the three banks to run aground – and swept the two other banks along in the fall.

*The salary and incentive schemes for Kaupthing and Landsbanki offer a different insight and will be dealt with in later logs.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

The Ponzi scheme beneath the loans

What does a banker think, who awards himself or big clients of his bank loans with interest rates comparable to a state, lower interest rates than the bank gets in its own finance, continuously rolls over bullet loans for himself and major clients and on the whole constructs the loan covenants in such a way that the bank gets all the downside and the client/he himself gets all the upside? Does he think that this bank has a great future? Or only a limited future so he better hurry up to profit as he can while there is something to profit from?

After the fall of banks I was of the opinion that the banks had been badly governed by people who had, in most cases, never seen anything but an Icelandic bank – that the combination of a lack of experience of international banking, hubris and arrogance had brought them down. Now, I’m less sure. Already in his short and concise report in April last year, Kaarlo Jannari pointed out that most probably the three Icelandic banks would have folded, crisis or not, since their business model was unsustainable. At the time, the possibilities of an extensive fraud were only starting to come to light. With the report of Althingi’s Investigative Commission we know much more – and I don’t think the lack of experience explains the whole demise.

Loan contracts aren’t generally available – breech of bank secrecy. Luckily, the Glitnir resolution committee was forced to make a few contracts public earlier this year in a lawsuit. The contracts offer a fascinating insight into the world of unsustainable banking. The contracts are between Glitnir and Fons, a holding company owned by Palmi Haraldsson. In close association with Jon Asgeir Johannesson and his Baugur empire, Fons became a major shareholder in Glitnir in the summer of 2007 – and the loans shot up like a rocket.

Not only were Glitnir’s coffers wide open to Fons but the rates and covenants were wholly unsustainable. The rates were absurdly low, marginally higher than the rates for the Icelandic states and even lower than the rates available to Glitnir financing itself. The rates reflected no risk.

Was that because the collaterals were so fabuolous? A bank’s criteria for collaterals is that they can be easily sold – not exactly the case with the Fons collaterals that were illiquid shares in Baugur and Fons companies, much less so at the evaluation Glitnir adorned them with.

A well-structured loan comes with covenants that secure the bank the possibility to make a margin call and/or has a personal guarantee. None of this was carefully spelled out in the Fons loans. In addition, Fons could choose which currency the loans were in – at a time, late 2007 and during 2008 when Glitnir itself couldn’t find any finance abroad.

These are the general characteristics of the four loans that Fons got from December 2007 until summer 2008. Let’s look closer at the loan contract for the biggest loan, a ISK10bn bullet loan, from December 2007. The context for the loan is to be found in the Althingi Investigative Report, published earlier this year. According to the minutes of Glitnir’s risk committee Fons was buying shares in FL Group from two of Fons’ and Baugur’s steady business partners, Magnus Armann and Hannes Smarason, now both living in the UK. The two had bought FL Group’s shares with loans from Glitnir and no longer met the covenants. To save everyone, except the bank, Fons borrowed the 10bn to buy the FL shares.

Fons had this minor problem that it didn’t have the necessary collaterals. That problem was resolutely resolved: Glitnir secured Fons it would buy one of its subsidiary that owned Skeljungur, an oil company, in a year’s time and valued Skeljungur at 8,7bn. The sale and the loan seem to be part of the concerted efforts of Glitnir and major shareholders in FL Group to hide that the company was in fact bankrupt. The movements here indicate serious market minipulation. In August Glitnir sold 51% of Skeljungur for 1,5bn – even considering the diminishing share value in many listed companies this price indicates that 8,7bn was a wild over-valuations. Glitnir’s write off is unclear. Even though the collateral was now apparently nowhere near the loan it doesn’t seem that Glitnir did anything to secure its position.

In a newspaper interview earlier this year, before the very revealing report was published, the owner of Fons Palmi Haraldsson said that he was Glitnir’s victim. Emails published in the report tell another story: the loans were made under huge pressure on Glitnir’s management from Haraldsson but most noticeably from Jon Asgeir Johannesson in spite of the frequent smileys. It’s difficult to picture Fons as the victim here but easier to see how seriously the minor shareholders and other clients suffered at the hand of managers who squandered the bank’ money on loans to major shareholders with the covenants so biased against the bank and in favour of these borrowers that the loans didn’t make any business sense.

Scrutinising this loan shows that the covenants went completely against the interest of the bank and minor shareholders. They are in no way comparable to loan covenants in foreign banks that the Icelandic banks liked to compare themselves with.

Another indication of lax or doubtful covenants came forward in a case at the Reykjavik County Court a few days ago where the Landsbanki resolution committee tried to secure a company that the ResCom thought Fons had pledged to Landsbanki. It turned out that although the company in question was on the bank’s book as a collateral it was neither correctly filed with the bank nor was it legal to use it as a collateral – another example of the favours granted to Fons, this time not with Glitnir but with Landsbanki. Other loans in Landsbanki seem to have been used to pay out record dividends from the supermarket chain Iceland – a textbook example of corporate raiders leaving a company struggling to service staggering loans to pay dividends.

In 1993 George Akerlof, who won the Nobel prize in economy in 2001, wrote an article, ‘Looting: The Economic Underworld of Bankruptcy for Profit.’ In many aspects it seems to describe what happened in Iceland. One day, the bankruptcy of the Icelandic banks might be shown to be an extensive case of bankruptcy for profit.

There’s no reason to believe that Glitnir’s loan to Fons were in any way unique. Rather they seem to be the usual kind of loans that the banks gave its biggest clients who in all cases were also among their major shareholders. The loans couldn’t give the necessary returns for the banks to run a viable operation. It means that the banks could only operate if there was a flow of money into them. An operation where new loans are funded by incoming money, not by loans being repaid or other normal financing for banks, looks more like a Ponzi scheme and less like a bank.

I wonder where the accountants were in all this. And what did the bankers when they makes out loans with lower interest rates than the bank got for its own funding or at interests rates comparable to the state? Didn’t the bankers know that the banks were a machinery of favours, not a proper bank? In an email printed in the Investigative Report that a Glitnir employee sent to the bank’s CEO the employee writes that he doesn’t really understand why the bank has to go to all this length of setting up complicated loan structure; surely it would be a lot simpler just to send the money to Haraldsson’s Cayman accounts.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.