Has Iceland learnt anything from the 2008 banking crash?

With its 2600 pages report into the banking collapse no nation has better study material to learn from than Iceland. However, with some recent sales in Landsbankinn and uncertainties regarding the sales of the new banks, Icelanders have good reasons to wonder what lessons have indeed been learnt from the 2008 banking collapse. If little or nothing has been learnt it’s worrying that two or three banks will soon be for sale in Iceland.

“During the election campaign I would have liked to hear the candidates form a clear and concise lessons from the 2008 banking collapse,” said one Icelandic voter to me recently. He’s right – there was little or no reference to the banking collapse during the election campaign in October.

The unwillingness to formulate lessons is worrying. So many who needed to learn lessons: bankers, lawyers, accountants, politicians and the media, in addition to every single Icelander.

Also, some recent events would not have happened had any lessons been learnt from this remarkable short time of fully privatised banking, from the beginning of 2003 to October 6 2008. There is a boom in Iceland, reminding many of the heady year 2007 but this time based inter alia tourism and not on casino banking. However, old lessons need to be remembered in order to navigate the good times.

Landsbankinn: six loss-making sales 2010-2016

Landsbankinn was taken over by the Icelandic state in 2011. The largest creditors, the deposit guarantee schemes in Britain and the Netherlands, were unwilling to be associated with the Landsbankinn estate, contrary to creditors in Kaupthing and Glitnir. Consequently, the Icelandic state came to own the new bank, Landsbankinn.

Over the years certain asset sales by Landsbankinn have attracted some attention but each and every time the bank has defended its action. In certain cases it has admitted mistakes but always with the refrain that now lessons have been learnt, time to move on.

Earlier this year, the Icelandic State Financial Investments (Bankasýsla), ISFI, published a report on one of these sales, the one causing the greatest concern – of Landsbanki’s share in a credit card issuer, Borgun. Landsbankinn had undervalued its Borgun share by billions of króna, creating a huge gain for the buyers.

Landsbankinn chose the buyers, nor bidding process etc., this was not a transparent sale. It so happens that some of the buyers happen to be closely related to Bjarni Benediktsson leader of the Independence party and minister of finance. No one is publicly accusing Benediktsson for having influenced the sale.

ISFI concluded that Landsbankinn should have known about the real value of the company and should only have sold via a transparent process, not by handpicking the buyers, some of whom are managers in Borgun. Part of the hidden value was Borgun’s share in Visa Europe, sold in November 2015 after the bank sold its Borgun share. Landsbankinn managers claim they were unaware of the potential windfall that could arise from such a sale.

Following the ISFI report the majority of the Landsbankinn board resigned but not the bank’s CEO, Steinþór Pálsson.

Landsbankinn’s close connections with the Icelandic Enterprise Investment Fund

Now in November the Icelandic National Audit Office, at the behest of the Parliament, investigated six sales by Landsbankinn, conducted in the years 2010 to 2016. It identified six sales, one of them being the Borgun sale, where it concluded that the state’s rules of ownership and asset sale had been broken as well as the bank’s own rules.

The report also points out that some of Landsbankinn’s own staff would have been aware of the potential windfall in Borgun. In a similar sale in another card issuer, Valitor, the sales agreement included a clause giving the bank share in similar gains after the sale.

Landsbankinn CEO Pálsson said he saw no reason to resign since lessons from these sales had already been learnt. However, nine days after the publication of this report Landsbankinn announced that Pálsson would step down with immediate effect.

Interestingly, four of the less-than-rigorous sales involved the Iceland Enterprise Investment Fund (Framtakssjóður), IEIF, set up in 2010 by several Icelandic pension funds. In the first questionable Landsbankinn sale, in 2011, the bank sold a portfolio of assets directly to the IEIF without seeking other buyers. The portfolio was later shown to have been sold at an unreasonably low price.

In relation to the sale Landsbankinn became the IEIF’s biggest owner. The Financial Surveillance Authority, FME, later stipulated that the bank could not hold a IEIF stake above 20%. In 2014 the bank then sold part of its share in the IEIF to the Fund itself, again at an unreasonably low price. In two sales, 2011 and 2014, Landsbankinn sold shares in Promens, producer of plastic containers for the fishing industry, again to the Fund.

As the Audit Office points out all the questionable sales have had two characteristics: a remarkably low price and Landsbankinn has not searched for the highest bidder but conducted a closed sale to a buyer chosen by the bank.

No one is accused of wrongdoing but it smacks of closed circuits of cosy relationships, a chronic disease in the Icelandic business community.

Landsbankinn and the blemished reputation

Landsbankinn claims it has in total sold around 6.000 assets via a transparent process. That may be true but the Audit Office report indicates that the bank chooses at times to be less than transparent, especially when it’s been dealing with the IEIF.

The bank’s management has time and again stated the importance of improving the bank’s reputation – after all, the 2008 collapse utterly bereft Icelandic banking of its reputation. This strife is the topic of statements and stipulations but so far, deeds have not followed words. The Audit Office concludes that inspite of its attempts the bank’s reputation has been blemished by the questionable sales.

How the banks were owned before the collapse

During the years of privatisation of the Icelandic banks, from 1998 to end of 2002, it quickly became clear that wealthy individuals were vying to be large shareholders in the banks. There was some talk of a spread ownership but in the end the thrust was towards having few individuals as main shareholders in the three banks.

Landsbankinn was bought by father and son, Björgólfur Guðmundsson and Björgólfur Thor Björgólfsson who during the 1990s got wealthy in the Soviet Union. A fact that gave rise to articles in the magazine Euromoney in 2002, before the Landsbankinn deal was concluded.

Kaupthing’s largest owners were, intriguingly, businessmen who got wealthy through deals largely funded by Kaupthing. The largest shareholder, Exista, was owned by two brothers, Ágúst og Lýður Guðmundsson and the second largest was Ólafur Ólafsson. The brothers own one of Britain’s largest producers of chilled ready-made food, Bakkavör. Ágúst got a suspended sentence in a collapsed-related criminal case. Ólafsson, together with Kaupthing managers, was sentenced to 4 ½ years in prison in the so-called al Thani case.

Glitnir had a less clear-cut owner profile to begin with. The family of Bjarni Benediktsson were large shareholders in the bank (then called Íslandsbanki, as the new bank is now called) but as the SIC report recounts the Landsbankinn father and son had built up a large stake in the bank. The FME kept pestering the father and son about these shares, the authority claimed the two were not authorised to own, later sold to the Benediktsson’s family and others.

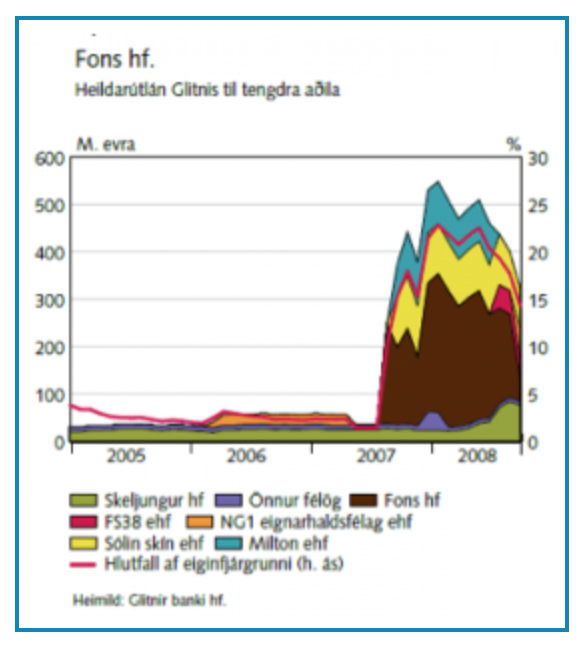

In spring of 2007 Jón Ásgeir Jóhannesson, who had insistently but unsuccessfully tried to buy a bank in 1998, gathered a group to buy around 40% in Glitnir. Involved were Baugur and FL Group, both owned or largely owned by Jóhannesson. One of his partners was Pálmi Haraldsson, a long-time co-investor with Jóhannesson. This graph (from the SIC report) shows Glitnir’s lending to Fons and other Haraldsson’s related companies: the cliff of debt rises after these businessmen bought Glitnir. It could also be called Icelandic banking in a nutshell:

Biggest shareholders = biggest borrowers

The graph above is Icelandic banking a nutshell. It characterises what the word “ownership” meant for the largest shareholders: they were also the banks’ largest borrowers, as well as borrowing in the other two banks. The shareholding of the largest groups in each of the banks was around and above 40% during most of the short run – the six years – of privatised banks.

Here some excerpts from the SIC report about the borrowing of the largest shareholders:

The largest owners of all the big banks had abnormally easy access to credit at the banks they owned, apparently in their capacity as owners. The examination conducted by the SIC of the largest exposures at Glitnir, Kaupthing Bank, Landsbankinn and Straumur-Burðarás revealed that in all of the banks, their principal owners were among the largest borrowers.

At Glitnir Bank hf. the largest borrowers were Baugur Group hf. and companies affiliated to Baugur. The accelerated pace of Glitnir’s growth in lending to this group just after mid-year 2007 is of particular interest. At that time, a new Board of Directors had been elected for Glitnir since parties affiliated with Baugur and FL Group had significantly increased their stake in the bank. When the bank collapsed, its outstanding loans to Baugur and affiliated companies amounted to over ISK 250 billion (a little less than EUR 2 billion). This amount was equal to 70% of the bank’s equity base.

The largest shareholder of Kaupthing Bank, Exista hf., was also the bank’s second largest debtor. The largest debtor was Robert Tchenguiz, a shareholder and board member of Exista. When the bank collapsed, Exista’s outstanding debt to Kaupthing Bank amounted to well over ISK 200 billion.

When Landsbankinn collapsed, Björgólfur Thor Björgólfsson and companies affiliated to him were the bank’s largest debtors. Björgólfur Guðmundsson was the bank’s third largest debtor. In total, their obligations to the bank amounted to well over ISK 200 billion. This amount was higher than Landsbankinn Group’s equity.

Mr. Thor Björgólfsson was also the largest shareholder of Straumur-Burðarás and chairman of the Board of Directors of that bank. Mr. Björgólfur Thor Björgólfsson and Mr. Björgólfur Guðmundsson were both, along with affiliated parties, among the largest debtors of the bank and together they constituted the bank’s largest group of borrowers.

The owners of the banks received substantial facilities through the banks’ subsidiaries that operated money market funds. An investigation into the investments of money market funds under the aegis of the management companies of the big banks revealed that the funds invested a great deal in securities connected to the owners of the banks. It is difficult to see how chance alone could have been the reason behind those investment decisions.

During a hearing, an owner of one of the banks (Björgólfur Guðmundsson), who also had been a board member of the bank, said he believed that the bank “had been very happy to have [him] as a borrower”. Generally speaking, bank employees are not in a good position to assess objectively whether the bank’s owner is a good borrower or not.

De facto, the Icelandic banks were “lenders of last resort” for their largest shareholders: when foreign banks called in their loans in 2007 and 2008 the Icelandic banks to a large extent bailed their largest shareholders out with massive loans.

Needless to say, systemically important banks in most European countries are owned by funds and investors, not few large shareholders who are also the banks’ most ardent borrowers. Icelandic banks will hopefully never return to this kind of lending again.

Separating investment banking and retail banking

As very clearly laid out in the SIC report the banks did not only turn their largest shareholders into their largest debtors but the banks’ own investments were usually heavily tied to the interests of their largest shareholders. Therefor, it’s staggering that now eight years after the collapse and three governments later a Bill separating investment banking and retail banking has not yet been passed in the Icelandic Parliament.

This means that most likely the new banks – Landsbankinn, Arion and Íslandsbanki – will be sold without any such limitation on their banking operations.

It is indeed difficult to see that there could be a market in Iceland for three banks. There is speculation that there will be foreign buyers but sadly, the history of foreign investment in Iceland is not a glorious one. Iceland is not an easy country to operate in as heavily biased as it is towards cosy relationships so as not to say cronyism.

Another way to attract foreign buyers is to offer shares for sale at foreign stock exchanges; Norway has been mentioned. Clearly a good option but I’ll believe it when I see it.

Judging from the short span of privatised banks in Iceland it’s also a worrying thought that the banks will again be owned by large shareholders, holding 30-50%.

The fact that state-owned Landsbankinn could over six years conduct six questionable sales with no consequence until much later, raises questions about lessons learnt. And the fact that this potentially simple risk-limiting exercise of splitting up investment and retail banking hasn’t yet been carried out by the Icelandic Parliament makes one again wonder about the lessons learnt. And yet, Iceland has the most thorough report in recent times in the world to learn from.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Thank you so much for this very revealing report and analysis. Around the world, Iceland is known for “jailing its bankers and corrupt officials” after the collapse, but this is usually said without much depth of understanding.

This report also seems to shed light on why and how recent corruption involving Sigmundur Davíð Gunnlaugsson took the turn that it did. In a New York Times article, I found this line: “Icelanders might forgive sexual experimentation, but ever since the devastating bank collapse in 2008, we have zero tolerance for shady financial dealings.” (http://www.nytimes.com/2016/04/09/opinion/thecheating-politicians-of-iceland.html?_r=0)

So thanks. Your thoughtful analysis is appreciated.

Cougar Brenneman

11 Dec 16 at 12:33 am

Needed to create you this very small observation just to thank you so much as before with your superb tactics you have shown in this article. It’s really particularly generous with people like you to convey unhampered what exactly a lot of people could have supplied for an e book to generate some profit for their own end, even more so considering the fact that you might have tried it if you ever considered necessary. Those tactics likewise acted to be the fantastic way to understand that most people have the same keenness the same as my very own to figure out a whole lot more with respect to this issue. I’m sure there are lots of more enjoyable sessions up front for people who read through your site.

goyard

21 Jul 23 at 4:44 am