Archive for October, 2017

From the pots and pan revolution to the Panama Papers and other scandals

The outcome of the election provides no clear option in forming a government but it is clear that Icelandic politics is changing: the Independence Party, earlier the backbone of Icelandic politics, has lost its strong position which it partly held because the Left kept splitting but on the Right the Independence Party was the only option. That is no longer the case. The many small parties now seem a fixture on the political scene in Iceland. Contrary to many other countries, nationalism and xenophobia do not colour Icelandic politics though these leanings can be detected. The narrative is unclear: the country of the pot and pan revolution votes in offshore company owners.

The opposition – especially the Social Democratic Alliance – won the election with the government losing twelve seats but it’s not a victory that they can make much use of. The favour of Icelandic voters is now split between eight parties in Alþingi but the political interest is huge with voter participation at 81.2%, up by just over one percentage point from 2016.

There have not been fewer women in Alþingi for a decade, so much for the land of gender equality – two of the new parties, the People’s Party and the Centre Party as utterly male-dominated. The Left victory, indicated by polls, did not materialise. The liberal global current that brought the Pirates, Revival (Viðreisn) and Bright Future 21 seats in 2016 has evaporated; these parties now hold ten seats and Bright Future did not get a single MP.

Forming a government will be tricky, even more so if this government is to last for more than a year or two.

Independence Party: the centre of power that was

The GOP of Icelandic politics is still old but no longer the grand centre of power. Gone are the elections when the party could count on the support of 30 to 40% of voters. In the party’s 2009 wipe-out it lost nine MPs, fell from 36.6% of the votes to 23.70% and 16 seats. It rose to 29%, 21 seats, last year but is now back at 16 seats and 25.2%. If it continues to attract only older voters, as is now the case, the party has a lot to worry about: it will, literally, die out.

The party’s position over the decades was strong: the Left kept shifting like a kaleidoscope the Independence Party ruled undivided and alone, except for very brief interludes. With Bright Future and in particular Revival, the latter is now lead by an ex-Indpenedence Party minister, those on the Right had and have other options.

Bjarni Benediktsson, though young and energetic, has not been able to shift or strengthen the party. He is however an undisputed leader, there are no obvious candidates in sight. Panama Papers companies, his IceHot1 registration on an affair website and his family’s connection to dubious deals and a pedophile have not undermined him. Rumblings in the party are just that, rumblings; unity on the surface.

The politcal centre

Bright Future did not particularly like to place itself on the Left Right axis but it was largely seen as a liberal party, palatable to those on the political Right. It was pro-EU, as is Revival. Bright Future instigated the fall of the government but did not reap any benefits from that. In government it did not manage to make its mark. Bright Future leader Óttarr Proppé did not have a strong enough message though his sartorial style of three piece corduroy and turtlenecks certainly stood out.

The Progressive Party did the remarkable feat of not losing ground, kept its 8 seats, though its former leader Sigmundur Davíð Gunnlaugsson left the party and raked in 10.8% of votes, probably a bit from everyone but most from the Independence Party. Progressive leader Sigurður Ingi Jóhannsson is of the pure Progressive mold, level-headed and portly, ready to work with both the Left and the Right and now wooed from both sides.

The Pirates, the voters’ darling last year, did lose four MPs, now have six. In spite of measured policies and no reasoned promises they did not cut a striking figure on the political scene.

The new political forces: male-oriented populists with a touch of xenophobia

The most remarkable political entry is that of Inga Sæland who rose to fame on the Icelandic X Factor. Sæland is a divorced mother of four and has done this and that. Counting herself as one of them her motivation is to improve the life of poor people in Iceland. Her party, the People’s Party, running for the first seemed to be destined for not making it into Alþingi. At the leaders’ debate two days before the election Sæland, asked what she wanted to achieve in politics, burst into tears, she was so passionate for her causes.

Whether it was the tears or her politics, Sæland secured 6.8% of the votes and four seats. For a party lead by a single mother – many of them in Iceland – it’s rather remarkable that she is the only woman MP of her party’s four MP.

To begin with Sæland struck a tone of xenophobia but only at the very beginning. Later she emphasised the need to live with an influx of foreigners, utterly denied any racist leanings and made no such references. Instead, her message was populist promises of better life for the poorer part of society.

Sigmundur Davíð Gunnlaugsson showed that 10.8% of Icelandic voters do not care about his lying about his offshore company. His voters seem more taken up with his promises of giving Icelanders shares in Arion bank where the government only owns 13% but has options to buy more. Gunnlaugsson’s other policies were less striking but continued his earlier message of subsidised agriculture and anti-EU tones. He has earlier flirted with nationalism and xenophobia and the same could be heard this time.

Less liberal voices, fewer women

Compared to other European countries where nationalism and xenophobia have been on the rise, the same is not the case in Icelandic politics. These tendencies can be detected close-up but the parties that have flirted with them, the Centre Party and the People’s Party have not particularly gained from it.

This is all the more remarkable because the influx of foreigners in Iceland has been very large since 2000: foreign inhabitants have gone from 2.6% in 2000 to 8.9% now. The largest nationality is Polish who have integrated well. In general, foreigners come to Iceland to get work, more than plenty of work to be had.

However, given the leanings of the two new parties, it can be argued that outward looking liberalism and globalisation is now weaker in Iceland than earlier. Due to the electoral system, the densely populated area around Reykjavík has less weight than the countryside.

The People’s Party and the Centre Party have an aura of anachronism in the sense that women are largely absent, except for the People’s Party leader. Otherwise, the appearance is portly elderly males. In total, these two parties hold eleven seats with only two of them filled by women.

In its world view the Centre Party also has an aura of anachronism: its leader has been prone to look back in search for political references rather than the future when his old party was strong because agriculture was a strong sector. Gunnlaugsson is interested in city planning: during his time as PM he even gave the Reykjavík city council drawings – not much more advanced than a kid’s drawings – of houses he thought should be built in the city centre in stead of more modern buildings already planned. If the drawings hadn’t come from the PM Office most people would have considered this a rather embarrassing and amateurish attempt to have a say.

The political narrative in Iceland: rambling and flip-flopping

Iceland very much debuted on the international scene as the first crisis-hit country in October 2008. The pots and pan revolution, which drove out an Independence Party-led government with the Social Democrats and also drove out a former Independent leader then governor of the Central Bank Davíð Oddsson, gave Iceland the image of a feisty young nation. The Office of a Special Prosecutor, which investigated and prosecuted people related to the banks, further supported that image.

However, it’s difficult to square that image with the fact that the Independence Party is still the largest party and the ousted Panama Papers ex-PM Gunnlaugsson secured almost 11% of the votes on Saturday. Icelanders may have flared up in the winter of 2008 and 2009 but they have partly turned to the conservatives, although riddled with scandals. And to Gunnlaugsson’s party, centred not only the political centre like the Progressives, his old party, but around Gunnlaugsson himself – after all, the Independence Party and the Centre Party together hold 36.1% of the votes.

Yet, the pots and pan spirit hasn’t quite disappeared – the Pirates are still in Alþingi and the Left is emboldened – but there certainly is no clear narrative of a country that doesn’t tolerate financial scandals, old family dynasties and their special interests. Flip-flopping and looking at persons rather than principles and ideals is still the Icelandic way to political choices.

Options for forming a government

With the Left Green touching 30% in opinion polls up to the election the Left clearly felt its time had now come. That’s less clear now though the Social Democrats have made a spectacular comeback, doubled their last year outcome. Its leader Logi Einarsson did not seem to have much going for him but rose and shone in the campaign, proved to be relaxed and passionate. He himself claims he has not been media trained and so, has preserved spontaneity and the human touch.

Forming a government is about making a team working towards the same goals. Bjarni Benediktsson did not achieve that with his government. He might have another go, will try to woo the Left Green. However, the opinion forming is that the government has lost, the opposition won.

Jakobsdóttir is adamant that a Left government could and is in the making but more time is needed. For her, it’s crucial that she will succeed, will be able to harness the momentum though she has already lost some of it. Otherwise, she could be destined to become the leader of great promise but ultimately unable to deliver power to her party, unable to show in a tangible way that she can be more than just a popular person.

When pundits were musing on the outcome before the election no one seemed to give it a serious thought that Gunnlaugsson could return to government. His gain came as a surprise but although no one is saying it aloud, it is highly unlikely he will be invited to join any government. He has a reputation for being unreliable also in the literal sense: as a PM he was often away, no one knew where, he rarely showed up in Alþingi for debates and as an MP he has stayed away though without calling in his substitute; most likely that will continue.

Contrary to the anchor of stability as the Independence Party likes to portray itself the party has been in the last three governments that sat for less than a mandate term. The Left government in power from 2009 to 2013 is the only government after the 2008 collapse that sat a whole term, or rather stumbled through it, more dead than alive due to enormous infighting in the two coalition parties Left Green and the Social Democrats who led the government.

Iceland is booming as growth figures around 7% of GDP show. Certainly an enviable situation, seen from the perspective of 0 to max 2% GDP growth in so many other European countries. But doing the “right thing” hasn’t necessarily benefited those in government since 2008 (see my pre-election blog) – and navigating the good times has never been easy in tiny Iceland. As we say in Icelandic: það þarf sterk bein til að þola góða daga, it takes strong bones to stand the good days – and that counts for governing in times of surplus.

Final results:

Bright Future: 0 seats, -4 seats; 1.2%

Progressive Party: 8 seats, as in 2016; 10.7%

Revival: 4 seats, -3; 6.7%

Independence Party: 16 seats, -5; 25.2%

People’s Party: 4 seats, new; 6.9%

Centre Party: 7 seats, new; 10.9%

Pirate Party: 6 seats, -4; 9.2%

Social Democrats: 7 seats, +4; 12.1%

Left Greens: 11 seats, +1; 16.9%

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

While waiting for the elections results

Short and sharp election campaign has come to an end. Foreign media, especially in the other Nordic countries, finds it difficult to understand that a prime minister, Bjarni Benediktsson, who has been anything but forthright on his business affairs before and around the 2008 banking collapse might well yet again be the leader of the largest party.

In addition, there is suspicion that the minister of justice dealt differently with clemency case for a pedofile because the Benediktson’s father helped the pedofile seeking clemency. And the disgraced leader of the Progressive Party Sigmundur Davíð Gunnlaugsson, forced to resign laster year as PM and party leader due to the Panama Papers is back in politics as a leader of his own party, the Centre Party.

Trust has been an issue in the election campaign but no matter these issues Benediktsson’s Independence Party is on a roll and Gunnlaugsson is doing remarkably well, might get around 10% of the votes. So do Icelanders not care about ethics in politics? Well, to a certain degree they do – after all, Gunnlaugsson couldn’t avoid resigning. But all in all, other matters seem to be more important to Icelandic voters. The Independence Party voters and party member have not demanded that their leader should resign.

Environmental issues have been more prominent than earlier, a reflection of the fact that tourism is now the most important sector, contributing more than the fishing industry, the country’s mainstay for decades. However, it was interesting to notice that in the main tv debate, Thursday evening, where leaders of the eight parties, likely to get an MP elected or who have an MP, debated, three leaders did not mention the environment as important: Bjarni Benediktsson, Sigmundur Davíð Gunnlaugsson and Inga Snæland, leader of the People’s Party, a new populist party that seems to be losing ground.

Some stats at the end: Icelanders are 343.960, registered voters are 248.502. Up for elections are 63 seats in Alþingi, the Icelandic parliament. In total, 11 parties offer candidates but seven might get candidates elected: the Independence Party, Left Green, the Social Democratic Alliance, the Centre Party, the Pirates, the Progressive Party, Revival; Bright Future, the party that withdrew from the government, causing it to fall, seems not to have gained from its decision and might disappear from the Alþingi.

My earlier blogs on the elections, here, here and here.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Iceland: political instability in spite of “doing it right”

To claim that Iceland has done all the right things since the financial crisis is hubristic. However, in the grand scheme of things it can be argued that the four governments, in power from 2008 until now, have broadly speaking done what needed to be done: the banks were dealt with without too great a public cost, an independent commission investigated the causes of the crash, matters related to the time up to the collapse have been investigated and individuals prosecuted; the economic policies have broadly stimulated growth, lately fuelled by boom in tourism. Yet, all of these sensible measures have not secured political stability as can be seen by elections held in 2016 and 2017.

Already by summer 2011 Iceland was back to economic growth in spite of the calamities of the banking collapse in October 2008. In spring the previous year, the Special Investigative Commission, SIC, had published its report. In the following years, the Office of the Special Prosecutor, now the District Prosecutor, was busy investigating and bringing bankers and their business partners to court. Well over twenty people have been imprisoned.

Iceland was not the only country hit by the financial catastrophe starting in 2007. In countries like the US and Britain, voters’ anger is often explained by the fact that in these countries little has been done to clarify what went on in the banks, the creators of the financial turmoil that hit various Western countries in 2007 and the following years.

In a long blog in September 2015 on the Icelandic recovery I pointed out that in spite of good recovery and growth the soul of the Icelanders was lagging behind: voters did not seem to embrace the parties bringing them a growing economy. That still seems to be the case judging from the political situation. Trust in political parties and party support is unstable and swinging.

This could very well be the future in Iceland as elsewhere: no matter the growing economy voters don’t put their trust in political parties as they once did, fewer belong to political parties or identify with a single party. It really isn’t about the economy any longer but a more elusive public mood.

Elections one year, minus a day, from the 2016 elections

Last year, the election was held on 29 October. This year it is on 28 October. Last year, the election was brought about by the then PM Sigmundur Davíð Gunnlaugsson leader of the Progressive Party having to step down due to the exposure in the Panama Papers of an offshore company held by him and his wife. The 2016 election ended the two-party coalition with the Independence Party (C) led by the Progressive Party.

In autumn this year, the coalition with two new centre liberal parties, Bright Future and Revival, led by the Independence Party fell when Bright Future lost the trust in PM Bjarni Benediktsson, a story recounted earlier on Icelog. When leaked document on Benediktsson’s business dealings in 2008, conflicting with his earlier explanations surfaced recently it seemed this would weaken the party’s standing (see Icelog).

A swing from left to right – but yet an Independence Party disappointment

To begin with, opinion polls indicated that a left government, albeit a coalition of three to four parties, was looming on the horizon – the only Icelandic left government that ever sat a full parliamentary term was the left government in power 2009 to 2013. The Left Greens and Katrín Jakobsdóttir, the party’s very popular leader, seemed to be raking up a lot of votes, at one point giving the Left Green a clear lead as the largest party. The Social Democratic has been in a limbo since the 2013 elections; its new leader, Logi Einarsson, did not seem to appeal to the voters but might have been a necessary support for the left government

In the last few days, the political landscape has been changing dramatically with the Independence Party surging ahead of the Left Greens. In a historic context the Independence Party surge is no surprise and also last year the party surged ahead in the last few days up to the elections. In one sense this indicates support for Bjarni Benediktsson and his party but the numbers are less uplifting: the party stands to lose around 3 to 5% and possibly four MPs. In addition, the forecast now would be a historic low for Benediktsson’s party, far from its 20th century earlier glory of licking the 40%.

The most surprising swing is the Social Democrats great gain in the polls. They seem to be attracting votes from the Left Green and the Progressive Party. Revival is crawling above the 5% threshold, needed to get the first MP elected. Only some weeks ago the party hastily elected a new leader, Þorgerður Katrín Gunnarsdóttir, after party founder Benedikt Jóhannesson’s unfortunate remarks on sufferers of sexual violence. Gunnarsdóttir is an earlier Independence Party MP and minister who left politics for some years after 2008 due to her links to Kaupthing where her husband worked. In a Parliament of very inexperienced MPs Gunnarsdóttir has proved a skilled politician.

Another surprise: former Progressive leader, the disgraced Gunnlaugsson, who resigned in autumn from his old party to form a new one, the Centre Party, is making good progress, well ahead of his old party. This, although Gunnlaugsson has mostly been invisible in Parliament all through the year though not calling in a substitute and hardly seen at all around in Iceland. Gunnlaugsson seems to be pinching votes from his old party and the Independence Party.

Nine parties are or have been likely to get an MP but it now seems that in the last spurt only seven parties will be represented in Alþingi, the Icelandic Parliament.

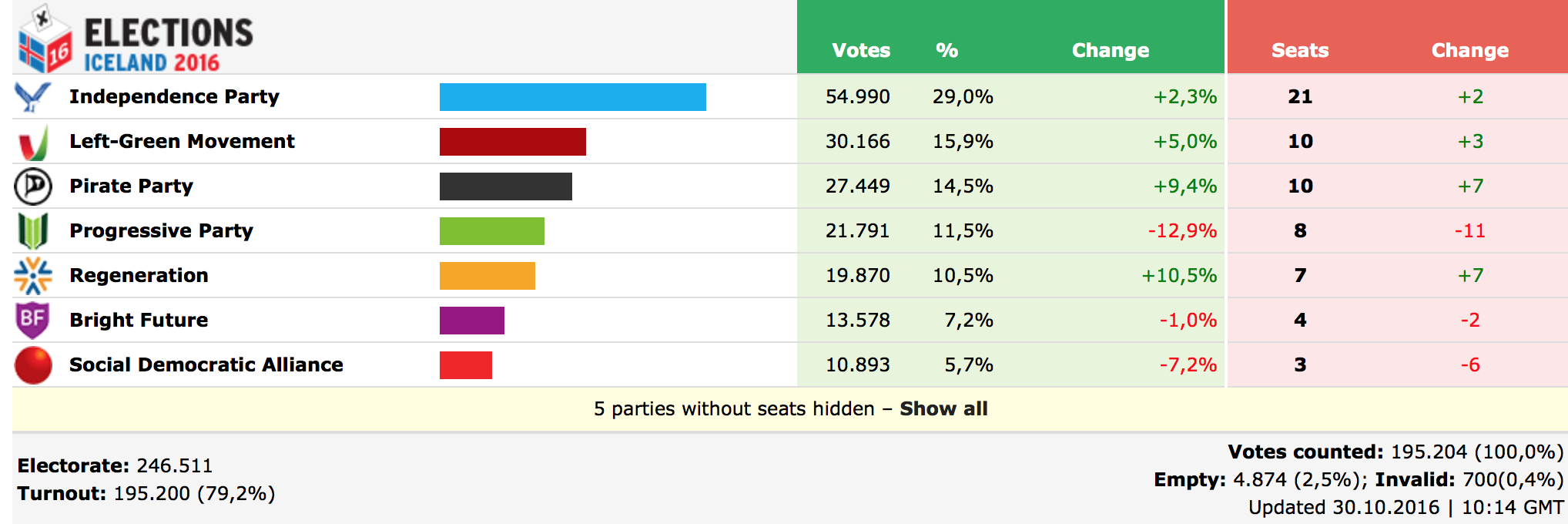

The 2016 results

(Regeneration is the party I call Revival, a name the party itself uses, Viðreisn in Icelandic)

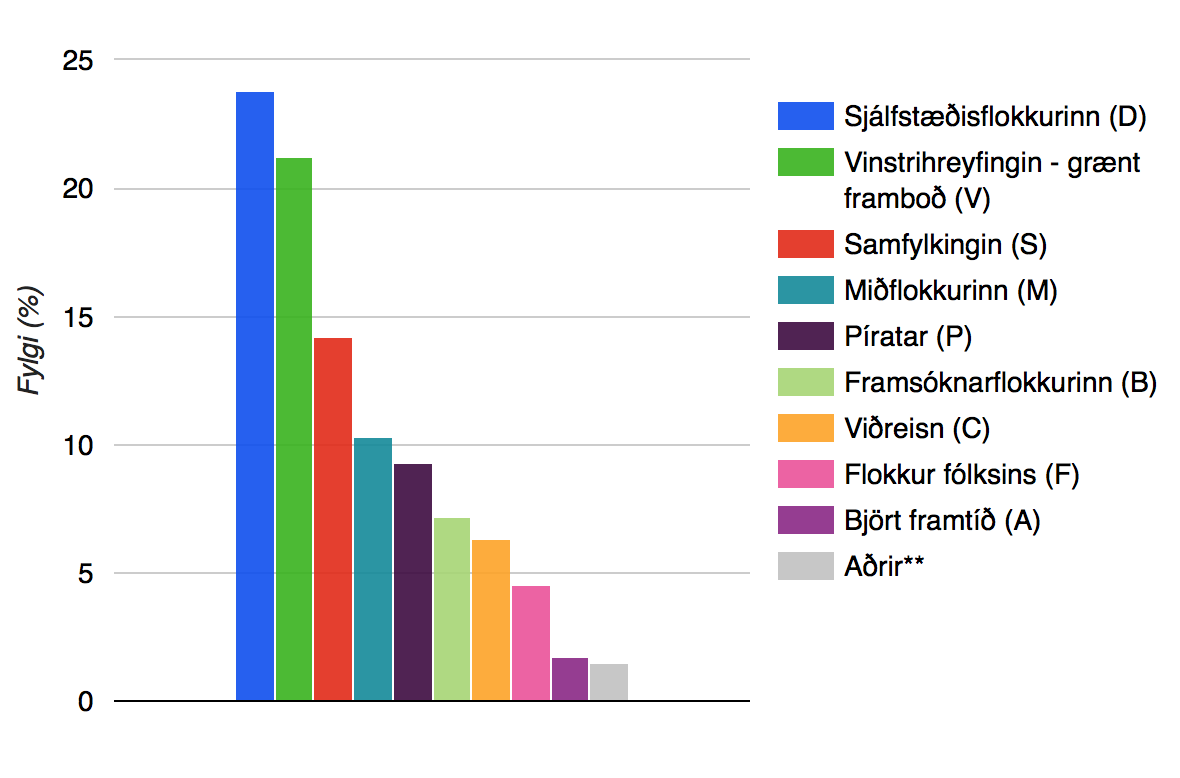

A poll of polls 26 October 2017. From the left: Independence Party, Left Green, Social Democrats, Centre Party, Pirates, Progressive Party, Revival, People’s Party, other parties below the 5% threshold. From Kosningaspá.

The attraction of the new – this time it’s the new-old Centre Party

The Pirates were the stars of 2016 election though they did not make it into government. This time they are doing less well, judging from the opinion polls.

A populist party, the People’s Party, had some chance of being the new stirring choice. The party has an unclear policy except promising a lot of money for every good cause. At the very beginning it seemed it would take up the topic of immigration only to drop it very quickly. The party is now losing ground and might not even make it into Parliament.

The new political kid on the block, Gunnlaugsson’s Centre Party is doing remarkably well, showing that Gunnlaugsson has a strong appeal in spite of his Panama Papers disgrace, a story he tries to manipulate in the face of facts when he gets the chance. Gunnlaugsson is the only leader heavily playing the immigration card. This comes as no surprise, he has been dallying with the topic before but so far, it has not proved to be a winning topic.

In this respect, Iceland has so far proven to be a real exception compared to the US and most European countries. Although immigration is rising rapidly in Iceland there is plenty of work to be had, more than can be filled by only Icelanders. For years and now decades, foreigners have been crucial for the fishing industry and now they keep the tourist industry and other services going.

Gunnlaugsson has always had a populist flare, promising handouts to voters. In the election 2013 he promised to take money from the failed banks’ creditors and give to voters. The plan, introduced with fanfare in November 2013 was nothing of the sort: it was part publicly funded part funded by those who were qualified to apply.

That hasn’t stopped Gunnlaugsson from claiming he kept his promise and again he waves a bundle of money in the face of voters: he promises to give Icelanders publicly held shares in Arion Bank, seemingly similar to the Russian handout of shares in the early 1990s. The idea is to secure a spread ownership and give Icelanders shares in coming profits – an idea that doesn’t stand up to scrutiny. Gunnlaugsson has mentioned the shares will amount to ISK150.000-200.000, €1200-1600.

Topics and European thoughts

A membership of the European Union has not been on the campaign agenda. The leader of the Social Democrats Logi Einarsson has mentioned Icelanders could vote on continued membership negotiations as early as next spring. Due to lack of interest in all things European such a vote is unlikely unless the Social Democrats are in government. This got Einarsson a headline the day he said it but it is not a reverberating topic.

Revival was very much founded in order to offer conservative voters with European leanings a new option instead of the anti-EU Independence Party. However, Revival has put little emphasis on the European ticket and has been more taken up with classic Social Democratic welfare issues.

The main election issues have been welfare, health care and to some degree education as well as classic Icelandic topics such as fishing quotas and power plants versus preserving untouched nature.

Possible outcomes – again, back to the old conservative roots

With a swing from the left to the right, the outcome might be similar to last year when I pointed out that Iceland was, yet again, returning to its old conservative roots. The Independence Party has been the back-bone of Icelandic politics after World War II, left governments have been the exception, contrary to the social democratic Nordic countries (though less so the last few years: only in Sweden the social democrats are now in power).

For the time being it is very unclear what sort of government might be in sight after the elections on Saturday. Last year, it took over two months to form what eventually was the three-party coalition. It might not be much easier this time but as things stand now it is almost certain that Bjarni Benediktsson will first be given the mandate to form a government. Last year, he only managed to do it after failing the first time around and after other leaders had tried.

What sort of coalition?

There are speculations of a coalition over the political spectre, with the Independence Party and the Left Green join forces. An unpopular choice for many Left Green voters but perhaps less so if it proves to the party’s only viable path to government.

A blue-red-green government would most likely be arch-conservative, not in the sense of the Independence Party but beholden to special interests in the fishing industry, unwilling to great changes. However, as things stand now the two parties alone will not have a majority.

Benediktsson has said that he would not be keen on leading a three-party coalition. His experience as a PM has clearly not been a happy one: unable to turn the government into a good team he failed the prime minister test. His government lacked the necessary team spirit.

Will Gunnlaugsson made a come-back in government? It is uncertain that an election victory will bring the Centre Party into government because Gunnlaugsson is highly unpopular among the politicians he was in government with. He proved highly unreliable, often incommunicado for days, not showing up at the Prime Minister office, not taking the phone from his fellow ministers. And no one knew where he was. Benediktsson, who was minister of finance in the Gunnlaugsson-lead government, is rumoured to be most unwilling to repeat the experience.

Minority governments have been a rare occurrence in Iceland, not seen for decades, contrary to the other Nordic countries. A minority government will hardly come into being until all option for a majority government have been exhausted. But then, knowing the voters would appreciate it the political party may also be preparing a real surprise: a speedily formed majority government. Given the various alphabetical options, the depressing outlook is another elections in a year’s time.

Here is my overview of the results of the October 2016 elections.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Why are Icelanders good at football… and music?

Björk and Sigurrós may be the most famous Icelandic musicians but there are many others. Now, footballers are doing pretty well. Better tame the football hubris for the time being but there are good reasons for Icelanders to excel in these two fields: young Icelanders have very good opportunities in both.

Recently, I watched a program on Rúv, the Icelandic broadcaster, on kids at the age of 12 to 14 preparing for a national science contest. The program followed the kids, from all around Iceland, at home and in school. One question they all got was what their did in their spare time. The answer? Each and every of them either did sport or music, some did both.

This is nothing new. After the war, the Icelandic music life was revived, or rather to a great degree, created by some Icelanders who had studied abroad and by a few foreign musicians who chose to make Iceland their home. The music life, also the music education, is still to some degree nourished by foreigners. This, in addition to many Icelandic musicians.

Most kids, not only in Reykjavík but also outside of Reykjavík, have access to music education. Many schools have school orchestras where children are taught to play the various instruments that make up an orchestra.

The same with sports. All over the country there are good facilities for the various sports, most notably football, handball and swimming.

It is from a broad base of nurtured talent that Björk and Sigurrós grew – and in football, footballers like the captain of the Icelandic national team Aron Einar Gunnarsson and Björn Bergmann Sigurdsson. Globalisation has helped these talents, both in music and football, to grow far beyond the amateur level with the world as their stage or their field.

Most of the football players playing for Iceland either do play professionally abroad or have done so. In addition they have grown up in the under 21 national team. Then there was the good work of the Swedish trainer Lars Lagerbäck whose assistant trainer Heimir Hallgrímsson is now the trainer of the national team.

Most national teams can count on their countries to support them. In Iceland, the support is tremendous. Basically everyone who is old enough to be aware of the world and not too old to be completely out of it, has his or her whole heart behind the team. On days with important international matches the traffic all over Iceland stops. Completely.

Just to qualify for the World Cup was a fantastic achievement, on the Icelandic scale of achievements – the smallest nation ever to qualify. The joy was profound. Icelanders definitely did not take it for granted that their team would indeed qualify.

From now on, every victory will be a bonus, deeply felt all over the country. The small economy will be shaken by every victory: consumption – such as buying trips to Russia – will go through the roof, productivity will most likely fall if Iceland wins a few matches.

But as you wonder why Icelanders can be so good at music and football keep in mind that it has nothing to do with some sudden wonder: it’s based on good education and easily accessible opportunities and facilities for decades. Something that every nation could match, if it is willing to invest in its youth and equal opportunities in education.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Benediktsson’s saga, the 2008 crash and how some were luckier than others

Nine years after the October 2008 financial crash Iceland is doing well, some justice was done as bankers and businessmen have been sentenced for criminal deeds up to the crash that has been better clarified than anywhere else. Yet, the collapse still looms large in Icelandic politics. Prime minister Bjarni Benediktsson leader of the Independence party is now being asked questions regarding certain transactions before the banking collapse 6 October 2008. An impertinent question is why the banks did indeed open on that day – it did allow some well-connected people to diminish the hit as the banks collapsed.

The family of PM Bjarni Benediktsson can lay claim to being the only political dynasty in Iceland. Often referred to as “Engeyingarnir” – the “Eng-islanders,” Engey being the island on the gulf by Reykjavík – the family has been wealthy and powerful for most part of the past century and still is. The family rose on the basis of fishing industry in the early 20th century but later extended into transport, insurance and banking. The minister of finance and leader of the coalition party Revival Benedikt Jóhannesson is closely related to the PM.

As some other big shareholders in the banks and other companies “Engeyingarnir” were heavily involved in conspicuous transactions in the months and hours up to 4pm 6 October 2008 when the Emergency Act was passed. That Act and that day mark the realisation of the collapse (the three banks had all failed by 9 October). One chapter relating to Benediktsson has now been added to that saga, as told in the Guardian and the Icelandic newspaper Stundin – it was known earlier that Benediktsson sold a position in Glitnir investment funds but the latest reports provide the figures: in total, ISK80m or c €643.000.

Most aspects of the collapse were painstakingly recounted in the 2010 report of the Special Investigation Commission, SIC, the most thorough report any nation has written on the 2007 and 2008 financial crisis. But Benediktsson’s story is a reminder of one catastrophic mistake of the government at the time: to open the banks on Monday 6 October 2008, thus giving privileged clients like Benediktsson the opportunity to make transactions, which minimised their losses following the collapse that no one except a small group around the prime minister knew of.

Last minute transactions under dark clouds

The core of the Guardian story is that up to the October 2008 crash Benediktsson sold assets in two investment funds, managed by Glitnir, the smallest of the three large Icelandic banks.

Late September 2008 it was clear that Glitnir could not meet its obligations in the following October. At the time, Glitnir was controlled by its largest shareholder Jón Ásgeir Jóhannesson and his partners. Jóhannesson is a famous name in the British business community as he owned at the time large retail companies on the UK high street.

The bank’s leadership had no option but to agree to a government takeover of 75% of the bank, thus saving the bank but almost wiping out the shareholders. Only days later it was clear that the bank was in such a state that the 75% takeover was not viable.

Just before midnight of 29 September Bjarni Benediktsson attended an emergency meeting with MP Illugi Gunnarsson, a friend of Benediktsson and also on the board of Fund 9, one of the two investment funds of this story. Together with chairman of Glitnir Þorsteinn Már Baldvinsson they met with Glitnir’s CEO Lárus Welding and Glitnir’s legal council. Why exactly the two MPs were at this meeting is not clear: their connections to Glitnir seems a better explanation rather than the fact they were both MPs.

Why was Fund 9 so toxic?

During these tumultuous days Benediktsson set in motion some private transactions. On 24 September he sold off ISK30m, €241.000 in a Glitnir fund called Fund 1, and bought Norwegian krone, which turned out to be a wise transaction given how much the ISK fell in the coming days and weeks. Incidentally, this happened on the same day that the chairman of Glitnir, Þorsteinn Már Baldvinsson met with governor of the Central Bank Davíð Oddsson to inform him that the bank could not meet its obligations in October.

On 2 October Benediktsson again sold ISK30m, this time in Fund 9 and then again ISK21m on 6 October. In an email the week before Benediktsson had specifically instructed for this latter transaction to be carried out on 6 October.

Late on 5 October PM Geir Haarde said to the Icelandic media that no further actions were needed regarding the Icelandic banks. At 11.29am 6 October the Icelandic financial surveillance authority, FME, effectively closed the Icelandic financial institutions. Benediktsson was one of several well-positioned people who made transactions on that morning.

Fund 9 was a particularly toxic fund because it was full of bonds connected to Jóhannesson’s companies and Glitnir, which, given that these companies relied so heavily on Glitnir funding, would clearly be heavily hit if Glitnir failed. That was indeed the case: these companies suffered heavy losses.

When Fund 9 opened again at the end of October 2008 its assets had been written down: the fund was now only 85.12% of what it had been on 6 October. However, if PM Haarde and the minister of finance had not bolstered Fund 9 with ISK11bn, now €88.5m, of public funds after the fund was closed the situation of the Fund 9 investors had been much worse. It has never been clarified why public funds were used to help Fund 9 investors and not investors in many other funds.

As Benediktsson had sold his Fund 9 assets worth ISK51m he was unaffected by the Fund 9 losses. In addition, there were the Icelandic króna Benediktsson converted into Norwegian krone. – In a media interview last year Benediktsson said he had owned “something” in Fund 9, nothing substantial and could not really remember the figures.

Benediktsson sold Glitnir shares in bleak February 2008

These were however not the only transactions Benediktsson made in 2008. In early February 2008 the future of the banks looked worryingly bleak though publicly bankers and politicians denied it. In addition to evaporating funding on international markets foreign banks were making margin calls on all the major Icelandic businessmen who also happened to own large parts of the banks.

The banks were now in a turbo-drive to help this selected group of businessmen to pay off their foreign loans, thus increasing lending to the selected few when lending was generally withdrawn. One of these businessmen was Karl Wernersson who in 2006 had bought large part of the Engeyingar’s shareholding in Glitnir.

The foreign margin calls led to some financial acrobatics for Wernersson, which also involved the Engeyingar because of the 2006 sale. This case, called the Vafningur (Bundle) case centres on loans from Glitnir and Sjóvá, an insurance company controlled by the Engeyingar.

Benediktsson signed some of the documents on behalf of Vafningur. The Sjóvá lending involved alleged fraudulent use of Sjóvá’s insurance funds. In the end, the case was not prosecuted and Benediktsson has always claimed that in spite of his signature he really did not know what the whole case was about.

One key event in February 2008 was a meeting of the three governors of the Central Bank with PM Geir Haarde, Árni Matthiesen minister of finance and leader of the social democrats Sólrún Gísladóttir minister of foreign affairs. The governors were profoundly pessimistic and news of this meeting flew around among politicians and others though it did not reach the media.

It’s not known if Benediktsson knew of the meeting and the unhappy tidings there. However, on 19 February Benediktsson and his friend Illugi Gunnarsson met with Lárus Welding CEO of Glitnir and the bank’s legal council, a meeting Benediktsson did ask for. Two days later Benediktsson set in motion to sell ISK119m, now €960.000, of his Glitnir shares, keeping only ISK3m. The transaction was carried out between 21 to 23 February 2008. On the 26 February Benediktsson and Gunnarsson wrote a much noted article in Iceland, outlining the dire straits of the Icelandic banks with no mention that Benediktsson had already sold the lion share of his shares in Glitnir.

Of the ISK119m worth of shares he sold he placed ISK90m in Fund 9. In March his assets in Fund 9 amounted to ISK165m, €1.3m. – In 2011, the daily DV told the story of the share sale, incidentally written by Ingi Freyr Vilhjálmsson who is also behind the latest and revealing reports in Stundin. At the time, Benediktsson refused to comment.

The power and influence of a prominent family

What was Bjarni Benediktsson doing in 2008? He was an MP, investor, close friend with some of the Glitnir staff, a member of a family who had been one of Glitnir’s largest shareholder and wielded considerable power in Icelandic politics and businesses. And Benediktsson had been a guest on some of Glitnir’s more ostentatious trips in the years before, such as football in London and salmon fishing in Siberia.

Benediktsson, born in 1970, became a member of Alþingi in 2003 but held at the same time positions in family companies. Not until after the 2008 collapse did he leave the family businesses where he had been on the boards of several companies.

Stundin has now exposed a far more detailed account of Benediktsson’s business dealings than was previously known, such as a failed property adventure in Dubai, related to his offshore company found in the Panama Papes and a much more successful venture in Miami, where Benediktsson was in charge of payments to constructors, literally all through the October 2008 collapse.

Due to the family assets and connections he had a far deeper relationship with Glitnir than just being an MP who happened to bank with Glitnir. His father Benedikt Sveinsson and his uncle Einar Sveinsson had been one of the largest shareholders of Glitnir 2003 to 2006. His uncle Einar was indeed the bank’s chairman at the time. Both his father and uncle sold both shares in Glitnir in 2008 and their positions in Fund 9 just before the banking collapse.

During these fateful autumn days Benedikt sold for ISK500m in Fund 9 and had the proceeds wired to Florida where the family has property. Einar sold for over ISK1bn. If the two brothers had waited Benedikt would have lost ISK24m due to falling value of Fund 9, his brother ISK183m.

An email from uncle Einar to a Glitnir employee on 1 October 2008 throws light on the kind of relationship the family had with Glitnir. The bank had made a margin call. “I don’t need to waste words,” wrote Einar, “that I don’t like this kind of message from the bank” expecting the employee to follow earlier decisions made.

The Teflon man of Icelandic politics

Benediktsson has been leader of the Independence party since 2009 but the rumours related to his family businesses have never left him. Apart from his sales of Glitnir shares and assets in Glitnir and the highly contentious Vafningur transactions, Benediktsson and his family have been associated to more recent cases.

In 2014 Benediktsson was minister of finance when Landsbanki, a state-owned bank, sold off a credit card company, Borgun. Borgun was sold without any bidding process, in fact it was sold without anyone knowing anything about the sale. Until it transpired Borgun had been sold to a consortium led by Benediktsson’s uncle Einar Sveinsson. This, in spite of the public policy of selling state assets in a transparent process to a highest bidder.

It later turned out that Borgun had been heavily undervalued. Less than a year after the sale, Borgun’s equity amounted to almost twice the sale’s price. Eventually, the Landsbanki CEO and board were forced to resign due to the Borgun sale. Benediktsson has always claimed he had been wholly oblivious of the whole thing, both that Borgun would be sold in a closed sale to a company of his uncle and the undervaluation.

Last year, the Panama Papers exposed that Benediktsson had owned part in a Seychelles company, set up by Mossack Fonseca. Only a year earlier, Benediktsson had staunchly denied he had owned a company in a tax haven. Asked about the Seychelles company he said he had not known it was offshore since it was set up through Luxembourg. Again, Benediktsson was blissfully ignorant and his party supported him.

The latest case, that also landed Benediktsson in international headlines, related to a bizarre relationship between his father and a sentenced paedophile. Iceland does not have a sex-offenders registry and people who have abused children can, as others who have been sentenced, recover their civil rights via a clemency process.

Called “honour revival” it requires a statement to confirm the soundness of character of the person in question. Benediktsson’s octogenarian father had given a statement to the sentenced paedophile who the father knew through old friends. What gave rise to questions was not that Benediktsson should be held responsible for his father’s action but that the minister of justice might have dealt with the case differently because of the family connections.

6 October 2008: the right and wrong decisions

As to the latest story of his Glitnir dealings Bjarni Benediktsson staunchly refuses he had any inside information. He just acted on what everyone could see: the banks were in serious trouble. His party still supports him.

It is worth keeping in mind that a large part of the Icelandic population owned shares in the banks. Many people saving up for their pension had, apart from obligatory savings via pension funds, privately saved by buying shares in the banks. Grandparents and parents had given children shares to save for their adult years. There were almost 40.000 shareholders in Kaupthing, the largest bank.

Benediktsson now says everyone knew the situation was precarious and he had only been trying to protect his assets. It is however not correct that everyone knew. The small shareholders quietly hoped the bankers were in control and that both bankers and politicians were right when they said publicly that everything would be fine.

The fact that the banks were kept open on the morning of 6 October 2008 was the wrong decision. It allowed the well-connected to take precautions but was of no help for the small shareholders who had no idea what was going on.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.