Archive for May, 2018

Iceland: from fishing to tourism / 10 years on

For some years, Iceland has been the new darling of international tourism, giving the economy a real boost and healthy balance of payment. There are however some worrying signs – overheating is a clear and present risk, never far off in Iceland. The Central Bank warns against compounding risk in tourism and real estate, even more worrying if unhealthy practices in the old banks have not entirely been eradicated in the new ones. In addition, the growing dependence on tourism is, in itself, not entirely a healthy sign, especially as Iceland still lacks clear policy for tourism, which should ideally not be based on ever more tourists but sustainability.

“It’s either at ankles or ears” – This Icelandic saying, meaning it’s either too little or too much, certainly fits the Icelandic economy. Navigating the years following the 2008 banking collapse and laying a reasonably sound foundation for the future was done with reasonable success. Lately, tourism is reshaping the Icelandic economy.

In addition to classic crisis policies, luck played its part in the relatively speedy recovery – low oil prices, high fish prices in international markets and last but not least, Iceland’s popularity as a tourist destination. Consequently, Iceland has, again, seen booming growth– 7.5% of GDP 2016 and 3.6% 2017 with forecast of 2.9% this year.

This time the growth is not leveraged; Icelanders can literally see the cash cows walking around in colourful outdoor clothing: since a few years, tourism, not fishing, is the largest sector in the economy. Though tourism has done miracles for the balance of payment and strengthened the króna to record levels, tourism may not bode much good for young Icelanders.

Add to that the interdependence of tourism, housing and foreign workers and the conclusion is the one reached in the Central Bank of Iceland’s latest Financial Stabilityreport: “Risks relating to tourism and high house prices could interact.”

Why did Iceland become such a popular destination?

The huge growth in tourism over the last few years has taken Icelanders by surprise; a common question is: “Why is Iceland suddenly so popular?” followed by: “Will this popularity last?”

As to the “why” did not entirely materialise out of thin air. Icelandair and later Icelandic tourist authorities have over the years and decades run rather successful campaigns. Posters with glorious photos from Iceland have for example appeared regularly on the walls in London tube stations.

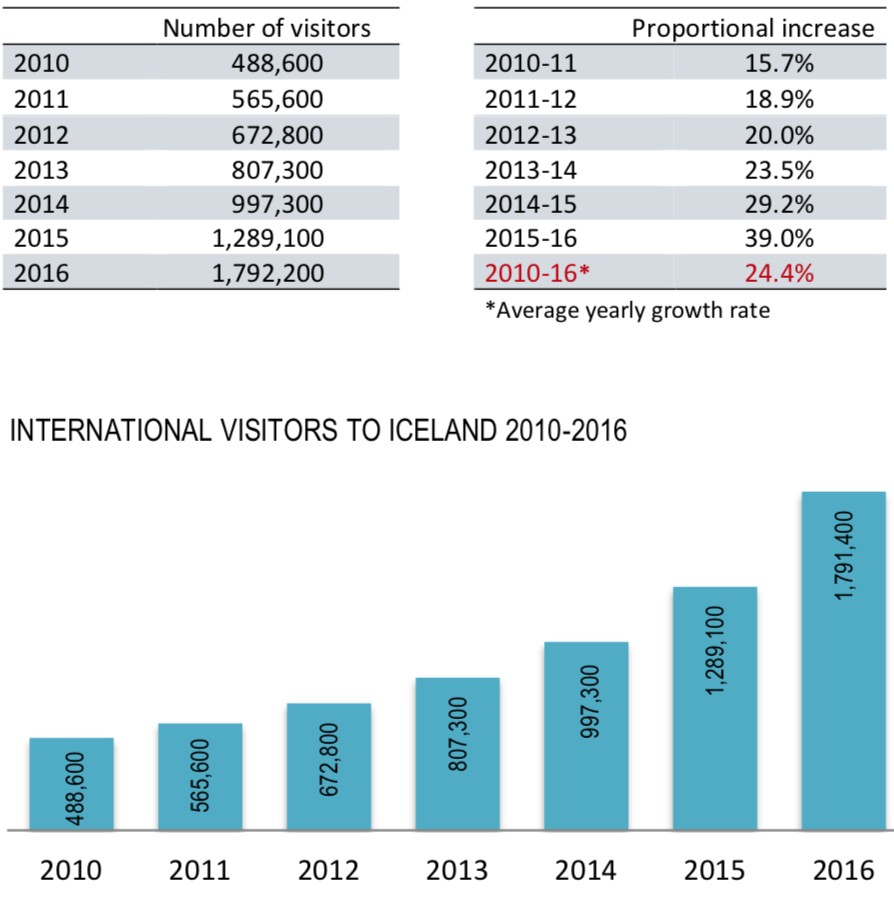

The rise in tourism was not as sudden as it might seem – there had been a steady increase since 2003 when the number of tourists were 320.000, then roughly the size of the population, growing by 3.5% to 15.1% a year until a downturn by 1.6% and 1.1% in 2009 and 2010 – though the great increase 2014 to 2016 were indeed staggering.

Icelandic Tourist Board (International visitors and cruises)

Currency fluctuations have at times made Iceland an expensive destination. That changed for some years after the 2008 banking collapse, making Iceland quite a reasonable destination until around 2014.

Luck helped Iceland when it came to international reports of the banking collapse. At the first Greek bailout in 2010, I did some comparison of international reporting of the crisis in the two countries. As in Greece there had been dramatic scenes of demonstrations and some altercations in the centre of the Reykjavík during the winter of 2008 to 2009.

But quite remarkably, foreign media would often choose to adorn reports from crash-struck Iceland with glorious landscapes rather than demonstrations, fire and fury. Greece also has spectacular and photogenic nature but the Greek financial crisis seemed more often shown in pictures of violent clashes and aggressive graffiti than alluring landscapes.

Far from being the negative impact feared at first, the Eyjafjallajökull eruption in April 2010 proved a gift literally from heaven for Icelandic tourism. An eruption is an awe-inspiring magnificent thing to behold; the Eyjafjallajökull coverage had quite an impact in drawing attention to the island.

The Instagram effect has helped. With the rise of Instagram, the popularity of Iceland was bound to rise – the island is a stunning Instagram backdrop.

Will the popularity last?

“The experience is that if you have a tourism boom of this magnitude, it is there to stay. There might be some ebb and flow, but tourism will, to my mind, continue to be one of the main pillars of the economy. That means we need to manage it well,” said Már Guðmundsson governor of the CBI in an interview with IMF2017.

Common sense dictates that the increase in tourism by 30% to 40% is unlikely to continue but experience from other countries shows that surge in tourism is durable – tourists are not as fickle as fish. According to an IMF study, countries whose travel exports increased by at least 4% of GDP over a decade were likely to see the number of tourists above the pre-surge levels ten years later. Iceland is a case in point – even the drop in arrivals in 2009 and 2010 did not change the underlying trend.

The latest figures show however a dramatic turnaround: the increase the four first months this year was 3.7% compared to last year. The increase was 28.6% 2014 to 2015, 34.7% 2015 to 2016 and a staggering 55.7% 2016 to 2017. The stats do indeed show a decline but all in all still a healthy growth though not the staggering growth of the record years.

In countries where the numbers did indeed decline, the causes are most often political turmoil, crumbling infrastructure – and most interestingly if also worryingly, from the Icelandic perspective – overcrowded tourist sites, environmental degradation and loss in price competitiveness.

The forecast for this year had been 2.2m but there are already some indications that this figure will be lower, even substantially lower. In addition to overcrowding and environmental degradations, difficult to measure, there is the loss in price competitiveness.

With the strong króna Iceland has become the most expensive tourist destination in Europe, even more expensive than Switzerland and Norway. The effect is bordering on the ridiculous: an underwhelming main course at €35 buys in a Reykjavík restaurant doesn’t compare with the quality of a main course at this price in the neighbouring countries.

Manifestos on tourism – but so far, little action

All of this is highly relevant to tourism in Iceland and merits a close scrutiny as it helps to identify the possible weaknesses.

All indicators show that tourists go to Iceland to experience nature. Even if they only go for a long weekend in Reykjavík they will almost certainly go on a tour for a day. The fantastic aspect of Iceland is that nature is not distant to urban areas, i.e. Reykjavík; it’s all around, in sight and easily accessed. The island is small, distances short. But there are some indications that overcrowding and faulty infrastructure is starting to detract from the pleasures of visiting the most famous places.

Arriving at Þingvellir or Geysir, with these spectacular spots hidden on arrival by dozens of buses and the passengers that spill from them, is not optimal. On the other hand, there are plenty of little known places to be enjoyed in solitude though it may take some research to find them.

As both the IMF and the OECD have pointed out in recent reports on Iceland, the varying governments over the last few years have failed to form a coherent policy for tourism in Iceland. The last three governments that came to power – in 2013 Progressives with the Independence party, in 2016 the Independence party with Bright Future and Revival and the present one, 2017 Left Green with Independence party and the Progressives – had all set high goals for tourism in their manifestos.

All of them aimed at forming a coherent policy for tourism, including plans to tax the sector in order to fund the necessary infrastructure for sustainable tourism. Nothing, absolutely nothing, has come of these well-intended manifestos – there is no policy and consequently, no plan on which to form a coherent tax policy.

Rudderless tourist economy

Managing the tourism boom, as governor Guðmundsson mentions, is still lacking in Iceland. The danger is that without a policy that aims at building up a quality tourism, fitting the (unavoidably) high prices, tourists will soon shun Iceland because they hear too much of crowded attractions and crumbling infrastructure with the pictures on social media to prove it.

With nature like the Icelandic one and high prices, the aim should not be to increase the number of tourists but develop tourism where fewer tourists spend more. This is what Costa Rica and Ireland have successfully done. Again, this requires strategic policies, so far wholly lacking in Iceland.

An economy of diminishing opportunities for high skills and education

Once upon a time in Iceland, there was little to be gained from lengthy education in order to be a high earner. Being a fisherman on a trawler meant very high salary and owning a large house as can still be seen in small fishing villages around the country. Working as a tradesman could also mean good salary.

This is no longer the case. There are fewer trawlers than earlier; a job on a good trawler is harder to come by than a highly paid managerial job. And the construction industry is not providing the same well-paying jobs as earlier. The large construction companies are very different from the small-scale constructor who hired his relatives to work for him.

All movements in a small economy like the Icelandic one tend to be rapid. The rise of tourism is no exception. The labour-intensive tourist sector is gobbling up a lot of manpower. The Dutch Disease might be around the corner, especially in an economy where the largest sector is mostly lacking direction and policies.

Recently, I have heard a number of Icelandic parents express their worries of what the labour market will offer their children in the coming years. In this rudderless tourist economy, there is no policy to develop other sectors. There is a budding tech sector in Iceland but some of the most successful Icelandic tech entrepreneurs have moved abroad and encouraged others to do the same, for the lack of tech infrastructure in Iceland. There is also a small pharmaceutical sector that could be developed further.

But a visionary policy of a diversified economy needs a government with a vision – and that has so far been lacking. The strong economic growth seems to lull Icelandic politicians into complacency. But a country that does not offer its young people the opportunities to seek education and then make use of it at home is not a good place to be. That’s greatly worrying many Icelandic parents.

More Icelanders leaving than returning

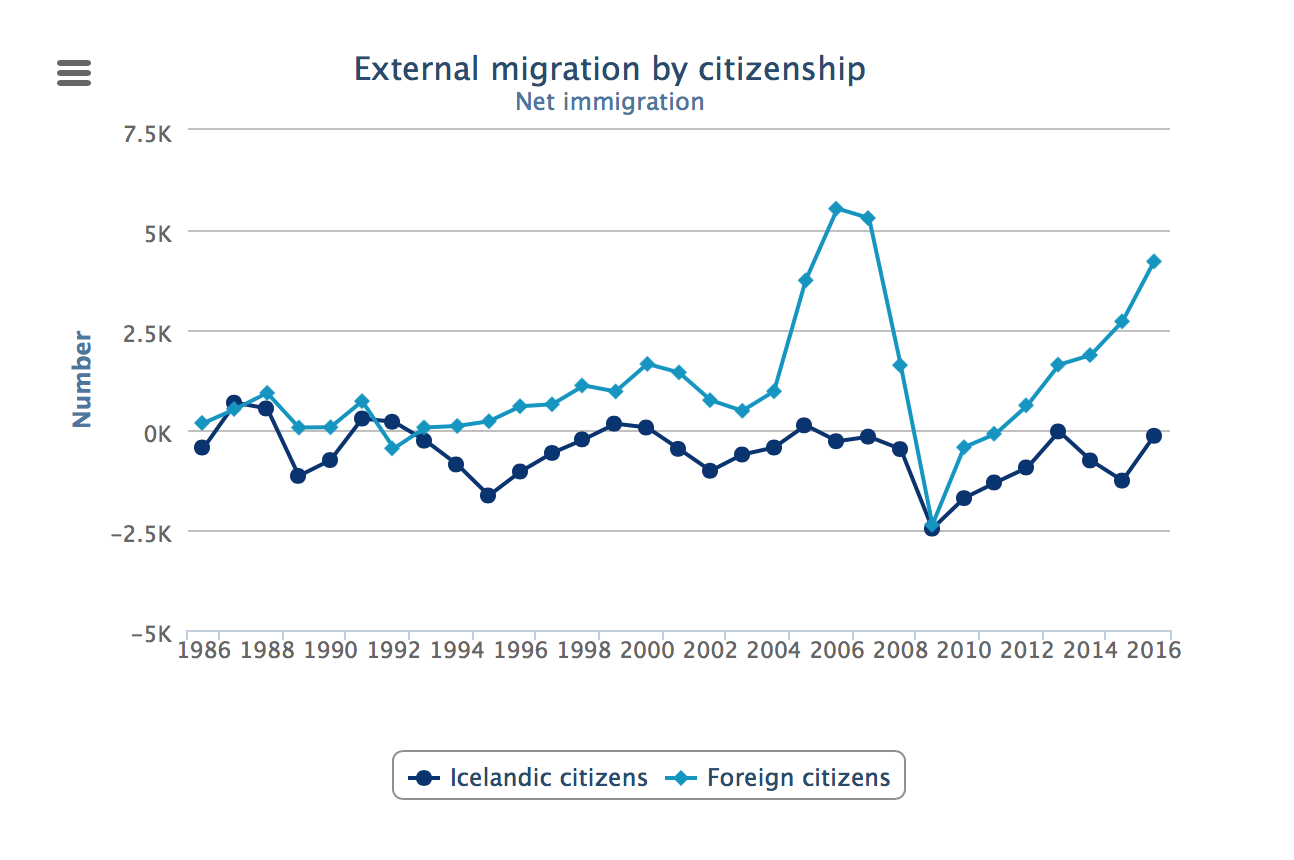

The demographics of Iceland is pretty healthy, it’s a nation of young people, compared to some other European nations. Icelanders are now just over 350.000, the number rises steadily. Except for a few years in the 1960s, 1970s and 1990s and then more recently in 2009, 2010 and 2011, more people enter the country than leave.

This looks promising – the nation is growing and more people move to Iceland than leave. However, there is potentially a more worrying underlying trend: in spite of the boom, more Icelanders are leaving Iceland than Icelanders moving home. Foreign nationals are keeping the inflow figures up – more foreigners come to Iceland than leave.

After the 2008 banking collapse whole sectors like construction were nearly wiped out, meaning not only the construction workers and tradesmen but also architects and engineers. Icelanders left in droves, both families and individuals, for work abroad. Norway was a particular popular destination as well as Denmark and Sweden.

The interesting – and for the Icelandic economy, worrisome – thing is that this flow has not stopped though the figures are lower. Icelanders are still leaving for jobs abroad. This, in addition to the decades-long tradition of young Icelanders seeking education abroad, returning as they graduate.

In 1999, 2000 and 2005 more Icelanders moved to Iceland than left but that is the exception. The rule is the other way around: more Icelanders leave than return. The one question Icelandic politicians really do not like to be asked is how they explain that in spite of the boom, there are still more Icelanders moving abroad than returning:

The intriguing fact is that going back as far as the stats show, more Icelanders have been leaving than foreigners immigrating, with over 2.500 foreigners arriving in 2005, 2006 and 2007 – and again since 2015.

There is no statistics to show clearly who is leaving but the Icelandic Statistics is working on a more informative registry. Anecdotal evidence indicates that the Icelanders who leave are better educated than the foreigners who immigrate; young people who leave to study look for jobs after studying abroad and do not necessarily return.

Also, that it is not just young people leaving but people in mid career. As Icelanders tend to have children early (though not as early as twenty years ago) some might be tempted to leave as the children have left home. One thing that all Icelanders notice when travelling abroad is how expensive food is in Iceland, one good reason to move, in addition to a primitive rental market. More Icelanders living abroad now own property in Iceland as a pied-à-terre. Iceland is well connected to Europe and the US, which does not only facilitate tourism but makes it easier for Icelanders to visit.

My sense is that the old tradition of faithfully returning after studying abroad might be changing. In international studies on migration the general reference is that if people do not return after eight years abroad it is unlikely they return. If the Icelandic pattern is indeed changing it might take some time before the statistics capture it clearly.

The main risk: the combined effect of falling tourist numbers and falling property prices

What could be the interaction between tourism and property prices that the CBI is warning against? To a certain degree it comes down to the classic effect of leverage and falling demand.

At first sight, the connection between tourism and property prices may not be an obvious one. However, one figure connects the two sectors: 16.5% of working people in Iceland are foreigners, up from just under 6% in 2005.

Since 1996, Poles have consistently been the largest number of immigrants each and every year, except in 2004, when they were beaten by Portuguese workers. Consequently, the largest foreign community in Iceland is the Polish one, just under 4% – in total, 8.9% of Icelanders are foreigners, i.e. born abroad. The foreign workers who came in the 1990s mostly came to work in the fishing industry. Later, the construction industry needed foreign workers – building sites in Iceland and London look the same, mostly foreigners from Eastern and Central Europe working there – and now there are the jobs in tourism.

The foreigners are, for obvious reasons, more likely to live in rental accomodation than own their home. If there is a real downturn in tourism, the foreigners will most likely be the first to lose their jobs. If there are few or no jobs to go around, the foreigners leave meaning they will leave their rented accommodation. This would most likely cause a downturn in the rental market, largely catered for by few large property companies. A downturn in tourism will to a certain degree affect construction work, with a compounding effect on the rental market.

This is how Iceland might be hit by the combined effect of falling number of tourists and falling property prices. In addition, external changes affect foreign workers such as changing circumstances in their countries. Poland is doing better, which might tempt some of the Polish workers to return home.

Tourism and the real estate market dominated by few large unlisted companies

An IMF 2014working paper on determinants in international tourism found that tourism “to small islands is less sensitive to changes in the country’s real exchange rate, but more susceptible to the introduction/removal of direct flights.”

Consequently, one risk to the Icelandic tourism economy is a rupture in flights. The eruption in Eyjafjallajökull was one example of how that might happen. That eruption luckily only caused disruption in flights for a few days. Other scenarios might be different.

But man-made havoc may be a cause for greater concern. The two Icelandic airlines, Icelandair and Wow Air carry between 70 and 80% of tourists coming to Iceland; this figure was 73.5%in April. The rest was shared by 13 international airlines with EasyJet having the largest market share among the foreign ones.

Icelandair is a listed company; Wow Air is privately owned. Icelandair has often had a bumpy ride in terms of profits and profitability. With new management and some new board members there is good reason to believe it will be better run now than in the past.

Wow Air is a different story. Early last year it published some financial indicators, which were not great. This year, so far – a total silence. Quite remarkably, its CEO and main owner Skúli Mogensen mentioned in a recent interview that the company was thinly capitalised – a statement that had some wow factor to it. It’s unlikely it was just a slip of the tongue, more likely a message but to whom is less clear.

In general, budget airlines have been experiencing problems; the demise of Monarch and the troubles of Norwegian are two cases in point. It’s difficult to see why Wow Air would be doing that much better. An under-capitalised company in a market of fewer customers and diminishing returns sounds ominous though they claim their sales went up this winter when Icelandair sold fewer seats.

The three largest property companies – Gamma, Heimavellir and Almenna leigufélagið – are all privately held. Again, the question is how well capitalised they are, how leveraged and how prepared for a down-turn in property prices, demand and rental prices. Gamma has recently shed its CEO and founder, shrunk its foreign operations (which seemed more based on dreams of 2007 than reality) but claims it is otherwise doing well.

Are there still “favoured” clients in the Icelandic banks?

The CBI risk warning related to the interlinked tourism and property market. A compounding factor is the relative opacity of the privately-held companies, quite large in the context of the Icelandic economy. The question is if any of the unhealthy practices of Icelandic banking pre-collapse can still be found such as the banks having, what I have called, “favoured” clients they serviced in a wholly abnormal way.

The Icelandic financial regulator, FME, has recently given noticeto Stefnir, an Arion Bank investment fund, for its risk management: Stefnir had, amongst other things, seven times exceeded its legal investment limits during the year from July 2016 to end of June 2017.

The FME notice does not mention what the investments relate to but most likely they are investment in United Silicon, a now failed venture that Arion was highly exposed to. The story of United Silicon is a sorry saga (which I investigated in detail for Rúv) of fraud and greed where Arion played a rather doubtful role as a lender and investor. In addition, pension funds managed by Arion were investors in United Silicon and kept investing well after it was clear that something was seriously wrong in United Silicon.

The Arion involvement with United Silicon smacked of how Kaupthing (and the two other large banks, Glitnir and Landsbanki) went out on a limb for their largest shareholders and their fellow travellers: the rule was that the “favoured” clients never lost, only the banks (i.a. by buying assets above market price). That the pension funds lost on United Silicion, is a sad reminder of how the old banks used (or abused) pension funds before the collapse, leading to gigantic losses after the collapse.

Given these indications of the return of bad banking, the large privately held and possibly thinly capitalised tourism companies and property companies take on a whole new dimension of risk.

If the risk materialises?

The short- and medium-term risk to the Icelandic economy is as the CBI has identified, overheating and the interconnection between tourism and the real estate market. Were this risk to materialise the effect would be nothing like the 2008 collapse, more the classic contraction of the economy Iceland has known for decades where depreciating króna and inflation eat away purchasing power, with rising unemployment (but not necessarily in a dramatic way; the foreigners partly take the hit and leave) and a lower standard of living.

To my mind, the no less worrying risk related to tourism is however the Dutch disease and lack of job opportunities for people with higher education or good skills – circumstances, that would cause young Icelanders to move abroad or stay abroad after studying and might also tempt mid-career people to leave.

Given that Icelanders who leave are more likely to be better educated than the foreigners who move to Iceland there might already be an on-going brain-drain in Iceland. All of this would in the long run make Iceland less attractive for Icelanders.

This risk is growing bigger every year as Icelandic governments seem sadly complacent in forming a long-term policy for tourism – a policy that would develop a high-yield tourism economy and tax it, both to invest in infrastructure and the diversification of the economy.

Next October there will be ten years since the banking collapse. Over the comings months I’ll be publishing blogs that in some way reflect on where Iceland is at now. This is the first “10 years on” blog.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.