Archive for July, 2018

The unsolved case of Landsbanki in dirty-deals Luxembourg / 10 years on

The Icelandic SIC report and court cases in Iceland have made it abundantly clear that most of the questionable, and in some cases criminal, deals in the Icelandic banks were executed in their Luxembourg subsidiaries. All this is well known to authorities in Luxembourg who have kindly assisted Icelandic counterparts in obtaining evidence. One story, the Landsbanki Luxembourg equity release loans, still raises many questions, which Luxemburg authorities do their best to ignore in spite of a promised investigation in 2013. Some of these questions relate to the activities of the bank’s liquidator, ranging from consumer protection, the bank’s investment in the bank’s own bonds on behalf of clients and if the bank set up offshore companies for clients without their consent.

The Landsbanki Luxembourg equity release loans were issued to clients in France and Spain. Indeed, all these loans were issued to clients outside of Luxembourg. One intriguing fact emerged during the French trial in Paris last year against Landsbanki Luxembourg and nine of its executives and advisors: the French clients got the bank’s loan documents in English, the non-French clients got theirs in French.*

Landsbanki Iceland went into administration October 7 2008. The next day, Landsbanki Luxembourg was placed into moratorium; liquidation proceedings started 12 December. Over the years, Icelog has raised various issues regarding the Landsbanki Luxembourg equity release loans, mostly sold to elderly people (see here). These issues firstly relate to how the bank handled these loans, both the marketing and the investments involved and secondly, how the liquidator Yvette Hamilius, has handled the Landsbanki Luxembourg estate and the many complaints raised by the equity release clients.

A liquidator is an independent agent with great authority to investigate. There is abundant material in Iceland, both from the 2010 Report of the Special Investigative Commission, SIC and Icelandic court cases where almost thirty bankers and others close to the banks have been sentenced to prison. These cases have invariably shown that the most dubious deals were done in the banks’ Luxembourg operations.

Already by June 2015, liquidators of the estates of the three large Icelandic banks were ending their work, handing remaining assets over to creditors. In the, in comparison, tiny estate of Landsbanki Luxembourg there is no end in sight due to various legal proceedings. Yet, its arguably largest problem, the so-called Avens bond, was solved already in 2011. At the time, Már Guðmundsson governor of the Icelandic Central Bank paid tribute to the help received from amongst others Hamiliusfor “considerable efforts in leading this issue to a successful conclusion.”

The Landsbanki Luxembourg equity release clients have another story to tell, both in terms of their contacts with the liquidator and Luxembourg authorities. In May 2012, these clients, who to begin with had each and everyone been struggling individually, had formed an action group and aired their complaints in a press release, questioning Luxembourg’s moral standing and Hamilius’ procedures.

The following day, the group got an unexpected answer: Luxembourg State Prosecutor Robert Biever issued a press release. As I mentioned at the time, it was jaw-droppingly remarkable that a State Prosecutor saw it as his remit to address a press release directed at the liquidator of a private company in a case the Prosecutor had not investigated. According to Biever, Hamilius had offered the borrowers “an extremely favourable settlement” but “a small number of borrowers,” unwilling to pay, was behind the action.

In 2013 Luxembourg Justice Minister promised an investigation into the Landsbanki products that was already taking “great strides.” So far, no news.

The Landsbanki Luxembourg equity release scheme: high risk, rambling investments

In theory, the magic of equity release loans is that by investing around 75% of the loan the dividend will pay off the loan in due course. I have seen calculations of some of the Landsbanki equity release loans that make it doubtful that even with decent investments, the needed level of dividend could have been reached – the cost was simply too high.

If something seems too good to be true it generally is. However, this offer came not from a dingy backstreet firm but from a bank regulated and supervised in Luxembourg, a country proud to be the financial centre of Europe. And Landsbanki was not the only bank offering these loans, which interestingly have long ago been banned or greatly limited in other countries. In the UK, equity release loans wrecked havoc and created misery some decades ago, leading to a ban on putting up the borrower’s home as collateral.

Having scrutinised the investments made for some of the Landsbanki Luxembourg clients the first striking thing is an absolutely staggering foreign currency risk, also related to the Icelandic króna. Underlying bonds on the foreign entities such as Rabobank and European Investment Bank were nominated in Icelandic króna (see here on Rabobank ISK bond issue Jan. 2008), in addition to the bonds of Kaupthing and Landsbanki, the largest and second largest Icelandic banks at the time.

Currencies were bought and sold, again a strategy that will have generated fees for the bank but was of dubious use to the clients.

The second thing to notice is the rudderless investment strategy. To begin with the money was in term deposits, i.e. held for a fixed amount of time, which would generate slightly higher interest rates than non-term deposits. Then shares and bonds were bought but there was no apparent strategy except buying and selling, again generating fees for the bank.

The equity release clients were normally not keen on risk but the investments were partially high risk. The 2007 and 2008 losses on some accounts I have looked have ranged from 10% to 12%. These were certainly testing years in terms of investment but amid apparently confused investing there was indeed one clear pattern.

One clear investment pattern: investing in Landsbanki and Kaupthing bonds

Having analysed statements of four clients there is a recurring pattern, also confirmed by other clients and a source with close knowledge of the bank’s investments: in 2008 (and earlier) Landsbanki Luxembourg invariably bought Landsbanki bonds as an investment for clients, thus turning the bank’s lending into its own finance vehicle. In addition, it also bought Kaupthing bonds. The 2010 SIC report cites examples of how the banks cooperated to mitigate risk for each other.

It is not just in hindsight that buying Landsbanki and Kaupthing bonds as equity release investment was a doomed strategy. Both banks had sky-high risk as shown by their credit default swap, CDS. The CDS are sort of thermometer for banks indicating their health, i.e. how the market estimates their default risk.

The CDS spread for both banks had for years been well below 100 points but started to rise ominously in 2007 as the risk of their default was perceived to rise. At the beginning of 2008, the CDS spread for Landsbanki was around 150 points and 300 points for Kaupthing. By summer, Kaupthing’s CDS spread was at staggering 1000 points, then falling to 800 points. Landsbanki topped close to 700 points. The unsustainably high CDS spread for these two banks indicated that the market had little faith in their survival. With these spreads, the banks had little chance of seeking funds from institutional investors (SIC Report, p.19-20).

The red lights were blinking and yet, Landsbanki Luxembourg staff kept on steadily buying Landsbanki and Kaupthing bonds on behalf of clients who were clearly risk-averse investors.

Equity release investment in some details

To give an idea of the investments Landsbanki Luxembourg made for equity release borrowers, here is some examples of investment (not a complete overview) for one client, Client A:

Loan of €2.1m in January 2008; the loan was split in two, each half converted into Swiss francs and Japanese yens. The first investment, €1.4m, two thirds of the loan,was in LLIF Balanced Fund (in Landsbanki Luxembourg loan documents the term used is Landsbanki Invest. Balanced Fund 1 Cap but in later overviews from the liquidator it is called LLIF Balanced Fund, a fund named in Landsbanki’s Financial Statements 2007 as one of the bank’s investment funds).

Already in February 2008 Landsbanki Luxembourg bought Kaupthing bond for this client for €96.000. End of April 2008 €155.000 was invested in Landsbanki bond, days before €796.000 of the LLIF Balanced Fund investment was sold. Late May and end of August Landsbanki bonds were bought, in both cases for around €99.000. In early September 2008 Landsbanki invested $185.000 in Kaupthing bonds for this client. The next day, the bank sold €520.000 in LLIF Balanced Fund.

Landsbanki’s investments were focused on the financial sector that in 2008 was showing disastrous results. For client A the bank bought bonds in Nykredit, Rabobank, IBRD and EIB, apparently all denominated in Icelandic króna. In addition, there were shares in Hennes & Maurits, and a Swedish company selling food supplement.

A similar pattern can be seen for the other clients: funds were to begin with consistently invested in LLIF Balanced Fund but later sold in favour of Kaupthing and Landsbanki bonds. Although investment funds set up by the Icelandic banks were later shown to contain shares in many of the ill-fated holding companies owned by the banks’ largest shareholders – also the banks’ largest borrowers – a balanced fund should have been seen as a safer investment than bonds of banks with sky-high CDS spreads.

MiFID and the Landsbanki Luxembourg equity release loans

Landsbanki certainly did not invent equity release loans. These loans have been around for decades. Much like foreign currency, FX, loans, a topic extensively covered by Icelog, they have brought misery to many families, in this case mostly elderly people. FX lending has greatly diminished in Europe, also because banks have been losing in court against FX borrowers for breaking laws on consumer protection.

There might actually be a case for considering the equity release loans as FX loans since the loans, taken in euros, were on a regular basis converted into other currencies, as mentioned above. – This is, so far, an unexplored angle of these cases that Luxembourg authorities have refused to consider.

Another legal aspect is that the first investments were normally done before the loans had been registered with a notary, as is legally required in France.

The European MiFID, Markets in Financial Instruments Directive was implemented in Luxembourg and elsewhere in the EU in 2007. The purpose was to increase investor protection and competition in financial markets.

Consequently, Landsbanki Luxembourg was, as other banks in the EU, operating under these rules in 2007. It is safe to say, that the bank was far below the standard expected by the MiFID in informing its clients on the risk of equity release loans.

The following paragraph was attached to Landsbanki Luxembourg statements: “In the event of discrepancies or queries, please contact us within 30 days as stipulated in our “General Terms and Conditions.”– However, the bank almost routinely sent notices of trades after the thirty days had passed.

It is unclear if the liquidator has paid any attention to these issues but from the communication Hamilius has had with the equity release clients there is nothing to indicate that she has investigated Landsbanki operations compliance with the MiFID. MiFID compliance is even more important given that courts have been turning against equity release lenders in Spain due to lack of consumer protection – and that banks have been losing in courts all over Europe in FX lending cases.

Clients offshorised without their knowledge

The “Panama Papers” revealed that Landsbanki was one of the largest clients of law firm Mossack Fonseca; it was Landsbanki’s go-to firm for setting up offshore companies. Kaupthing, no less diligent in offshoring clients, had its own offshore providers so the leak revealed little regarding Kaupthing’s offshore operations. The prime minister of Iceland Sigmundur Davíð Gunnlaugsson, who together with his wife owned a Mossack Fonseca offshore company, became the main story of the leak and resigned less than 48 hours after the international exposure.

In September 2008, a Landsbanki Luxembourg client got an email from the bank with documents related to setting up a Panama company, X. The client was asked to fill in the documents, one of them Power of Attorney for the bank and return them to the bank. The client had never asked for this service and neither signed nor sent anything back.

In May 2009, this client got a letter from Hamilius, informing him that the agreement with company X was being terminated since Landsbanki was in liquidation. The client was asked to sign a waiver and a transfer of funds. Attached was an invoice from Mossack Fonseca of $830 for the client to pay. When the client contacted the liquidator’s office in Luxembourg he was told he should not be in possession of these documents and they should either be returned or destroyed. Needless to say, the client kept the documents.

Company X is in the Offshoreleak database, shown as being owned by Landsbanki and four unnamed holders of bearer shares. – Widely used in offshore companies, bearer shares are a common way of hiding beneficial ownership. Though not a proof of money laundering, the Financial Action Task Force, FATF, considers bearer shares to be one of the characteristics of money laundering.

This shows that Landbanki Luxembourg set up a Panama company in the name of this client although the client did not sign any of the necessary documents needed to set it up. Also, that the liquidator’s office knew of this. (This account is based on the September 2009 email from Landsbanki Luxembourg to the client and a statement from the client).

Other clients I have heard from were offered offshore companies but refused. The story of company X only came out because of the information mistakenly sent from the liquidator to the client.

Landsbanki Luxembourg clients now wonder if companies were indeed set up in their names, if their funds were sent there and if so, what became of these funds. This has led them to attempt legal action in Luxembourg against the liquidator. Only the liquidator will know if it was a common practice in Landsbank Luxembourg to set up offshore companies without clients’ consent, if money were moved there and if so, what happened to these funds.

The curious role of a certain Philomène Ruberto

Invariably, the equity release loans in France and Spain were not sold directly by Landsbanki Luxembourg but through agents. This is another parallel to FX lending characterised by this pattern. According to the Austrian Central Bank this practice increases the FX borrowing risk as agents are paid for each loan and have no incentive to inform the client properly of the risks involved.

One of the agents operating in France was a French lady, Philomène Ruberto. In 2011, well after the collapse of Landsbanki, the Landsbanki Luxembourg was putting great pressure on the equity release borrowers to repay the loans. At this time, Ruberto contacted some of the clients in France. Claiming she was herself a victim of the bank, she offered to help the clients repay their loans by brokering a loan through her own offshore company linked to a Swiss bank, Falcon Private Bank, now one of several banks caught up in the Malaysian 1MDB fraud.

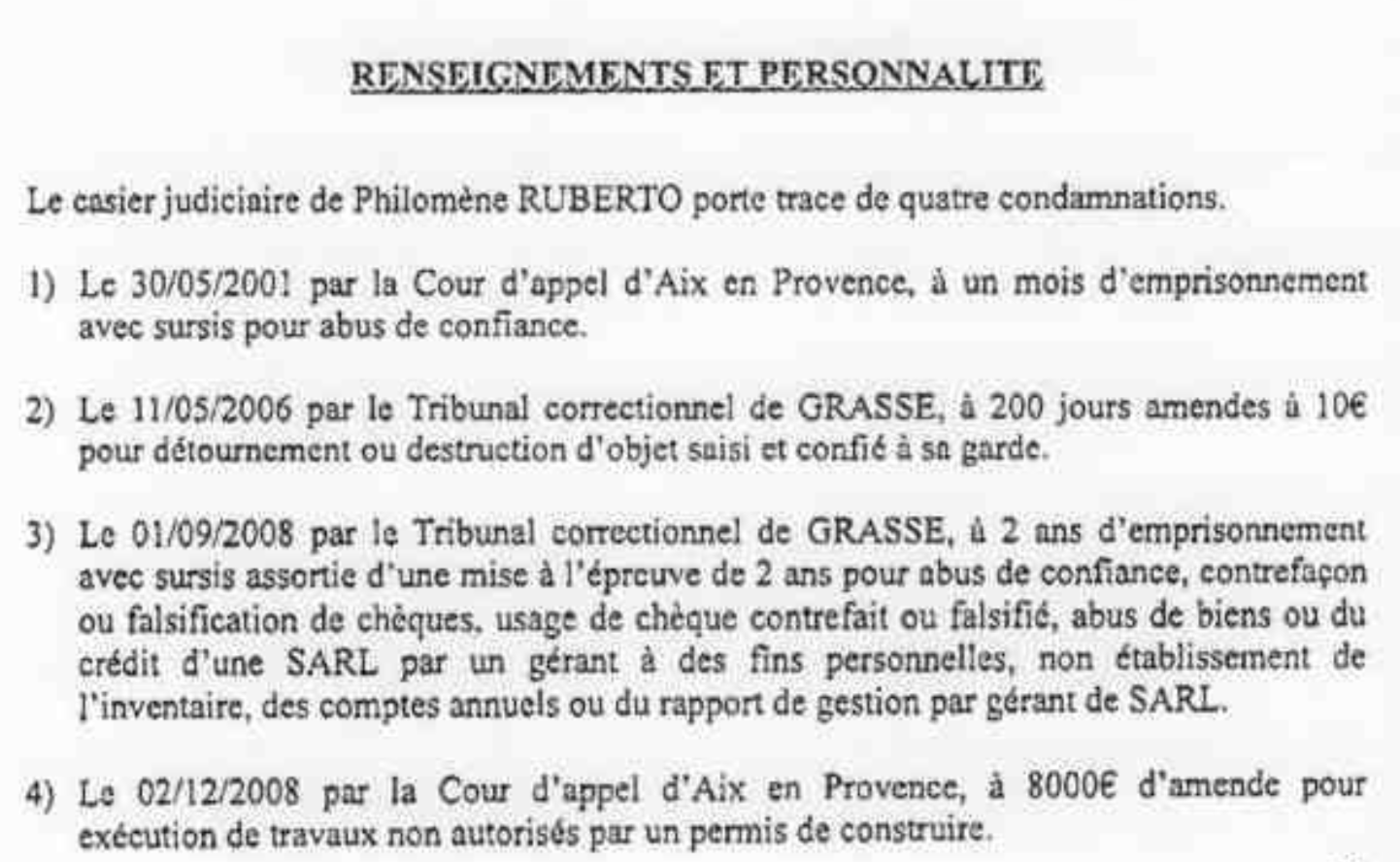

Some clients accepted the offer but that whole operation ended in court, where the clients accused Ruberto of fraud and breach of trust. In a civil case judgement at the Cour d’appel d’Aix en Provence in spring 2013, the judge listed a series of Ruberto’s earlier offenses, committed before and during the time she acted as an agent for Landsbanki:

This case was sent on a prosecutor. In a penal case in autumn 2014 Ruberto was sentenced by Tribunal Correctionnel de Grasse to 36 months imprisonment, a fine of €15,000 in addition to the around €190,000 she was ordered to pay the civil parties. According to the 2104 judgement Ruberto was, at the time of that case, detained for other causes, indicating that she has been a serial financial fraud offender since 2001.

But Ruberto’s relationship with Landsbanki Luxembourg prior to the bank’s collapse has a further intriguing dimension: GD Invest, a company owned by Ruberto and frequently figuring in documents related to her services, was indeed also one of Landsbanki Luxembourg largest borrowers. The SIC Report (p.196) lists Ruberto’s company, GD Invest, as one of the bank’s 20 largest borrowers, with a loan of €5,4m.

In 2007, at the time Ruberto was acting as an agent in France for Landsbanki Luxembourg, she not only borrowed considerably funds but, allegedly, on very favourable terms. In March 2007, GD Invest borrowed €2,7m and then further €2.3m in August 2007, in total almost €5,1m. Allegedly, Ruberto invested €3m in properties pledged to Landsbanki but the remaining €2m were a private loan. It is not clear what or if there was a collateral for that part.

By the end of 2011, Ruberto’s debt to Landsbanki Luxembourg was in total allegedly €7,5m. In January 2012 it is alleged that the Landsbanki Luxembourg liquidator made her an offer of repaying €2,4m of the total debt, around 1/3 of the total debt. Ruberto’s track record of fraudulent behaviour from 2001, raises questions to her ties first to Landsbanki and then to Landsbanki Luxembourg liquidator. (The overview of Ruberto’s role is based on emails and court documents provided by Landsbanki Luxembourg equity release borrowers.)

Inconsistent information from the Landsbanki Luxembourg liquidator

From 2012, when I first heard from Landsbanki Luxembourg equity release borrowers, inconsistent information from the liquidator has been a consistent complaint. The liquidator had then been, and still is, demanding repayment of sums the clients do not recognise. There are also examples of the liquidator coming up with different figures not only explained by interest rates. The borrowers have been unwilling to pay because there are too many inconsistencies and too many questions unanswered.

As mentioned above, Landsbanki Luxembourg was put in suspension of payment, in October 2008 and then into administration in December 2008. As far as is known, people who later took over the liquidation were called on to work at the bank during this time. During this time, many clients were informed that their properties had fallen in value, meaning that the collateral for their loan, the property, was inadequate. Consequently, they should come up with funds. At this time, there was no rational for a drop in property value. This is one of the issues the borrowers have, so far unsuccessfully, tried to raise with the liquidator.

Other complaints relate to how much had been drawn. One example is a client who had, by October 2008, in total drawn €200,000. This is the sum this client want to repay. Mid October 2008, after Landsbanki Luxembourg had failed, this client got a letter from a Landsbanki employee stating that close to €550,000, that the client had earlier wanted transferred to a French account, was still “safe” on the Landsbanki account. This amount was never transferred but the liquidator later claimed it had been invested and demanded that the client repay it.

The liquidator has taken an adversarial stance towards these clients. The clients complain of lack of transparency, inconsistent information, lack of information and lack of will to meet with them to explain controversies.

The role and duty of a liquidator

By late 2009 the liquidator had sold off the investments. This is what liquidators often do: after all, their role is to liquidate assets and pay creditors. However, a liquidator also has the duty to scrutinise activity. That is for example what liquidators of the banks in Iceland have done. A liquidator is not defending the failed company but the interests of creditors, in this case the sole creditor, LBI ehf.

Incidentally, the liquidator has not only been adversarial to the clients of Landsbanki but also to staff. In 2011 the European Court of Justice ruled against the liquidator in reference for a preliminary ruling from the Luxembourg Cour du cassation brought by five employees related to termination of contract.

Liquidators have great investigative powers. In addition to documents, they can also call in former staff as witnesses to clarify certain acts and deeds. If this had been done systematically the things outlined above would be easy to ascertain such as: is it proper in Luxembourg that a bank systematically invests clients’ funds in the bank’s own bonds? Was the investment strategy sound – or was there even a strategy? Were clients’ funds systematically moved offshore without their knowledge? If so, was that done only to generate fees for the bank or were there some ulterior motives? And have these funds been accounted for? A liquidator can take into account the circumstances of the lending and settle with clients accordingly.

And how about informing the State Prosecutor of Landsbanki’s investments on behalf of clients in Landsbanki bonds and the offshoring of clients without their knowledge?

But having liquidators in Luxembourg asking probing questions and conducting investigations is possibly not cherished by Luxembourg regulators and prosecutors, given that the country’s phenomenal wealth is partly based on exactly the kind of dirty deals seen in the Icelandic banks in Luxembourg.

LBI ehf – the only creditor to Landsbanki Luxembourg

Landsbanki Luxembourg has only one creditor – the LBI ehf, the estate of the old Landsbanki Iceland. According to the LBI 2017 Financial Statements the expected recovery of the Landsbanki Luxembourg amounts to €84,3m, compared to €74,3m estimated last year. The increase is following what LBI sees as a “favourable ruling by the Criminal Court in Paris on 28 August 2017,” i.e. that all those charged were acquitted.

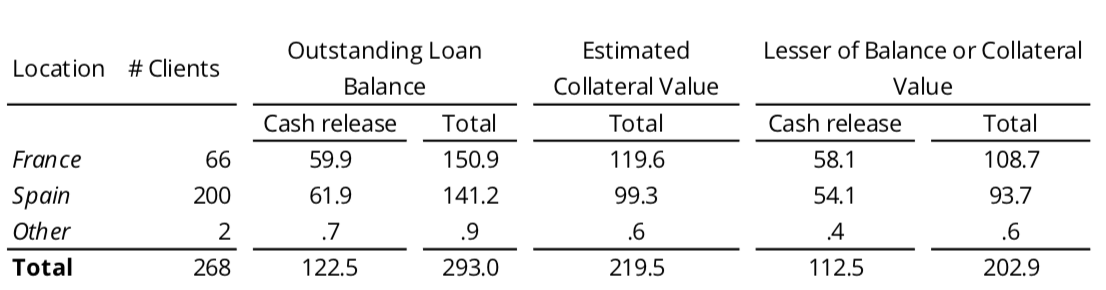

The only assets in Landsbanki Luxembourg are the equity release loans. The breakdown of the loans, in EUR millions, in the LBI 2017 Statements is the following:

Further to this the Statements explain that “LBI’s claims against the Landsbanki Luxembourg estate amounted to EUR 348.1 million, whereas the aggregate balance of outstanding equity release loans amounted to EUR 293.0 million with an estimated recoverable value … of EUR 84.3 million.”

As pointed out, the information “regarding legal matters pertaining to the Landsbanki Luxembourg estate is mainly based on communications from that estate‘s liquidator, and not all of such information has been independently verified by LBI management.”

Apart from the criminal action in Paris and the appeal of the August 2017 judgment, the Financial Statements mention other legal proceedings: “Landsbanki Luxembourg is also subject to criminal complaints and civil proceedings in Spain. … In November 2012, several customers in France and Spain brought a criminal complaint in Luxembourg against the liquidator, alleging that the former activities of Landsbanki Luxembourg are criminal and thus that the estate’s liquidator should be convicted for money laundering by trying to execute the mortgages. Other criminal complaints have been filed in Luxembourg in 2016 and 2017 based on the same grounds against the liquidator personally.”

This all means that “LBI’s presented estimated recovery numbers are subject to great uncertainty, both in timing and amount.”

What is Luxembourg doing?

It is not the first time I ask this question here on Icelog. In July 2013 there was the news from Luxembourg, according to the Luxembourg paper Wort, that there were two investigations on-going in Luxembourg related to Landsbanki. This surfaced in the Luxembourg parliament as the Justice Minister Octavie Modert responded to a parliamentary question from Serge Wilmes, from the centre right CSV, Luxembourg’s largest party since founded in 1944.

According to Modert both cases related to alleged criminal conduct in the Icelandic banks. One investigation was into financial products sold by Landsbanki. “…the deciding judge is making great strides,” she said, adding that in order not to jeopardize the investigation, the State Attorney was unable to provide further details on the results already achieved.”

Sadly, nothing further has been heard of this investigation.

In spring 2016 the Luxembourg financial regulator, Commission de surveillance du secteur financier, CSSF had set up a new office to protect the interests of depositors and investors. This might have been good news, given the tortuous path of the Landsbanki Luxembourg clients to having their case heard in Luxembourg – CSSF has so far been utterly unwilling to consider their case.

The person chosen to be in charge is Karin Guillaume, the magistrate who ruled on the Landsbanki Luxembourg liquidation in December 2008. As pointed out in PaperJam, Guillaume has been under a barrage of criticism from the Landsbanki clients due to her handling of their case, which somewhat undermines the no doubt good intentions of the CSSF. From the perspective of the Landsbanki Luxembourg clients, CSSF has chosen a person with a proven track record of ignoring the interests of depositors and investors.

So far, Luxembourg authorities have resolutely avoided investigating Landsbanki and the other Icelandic banks. In Iceland almost 30 bankers, also from Landsbanki, and others close to the banks have been sentenced to prison, up to six years in some cases (changes to Icelandic law on imprisonment some years ago mean that those sentenced serve less than half of that time in prison before moving to half-way house and then home; they are however electronically tagged and can’t leave the country until the time of the sentence is over).

In the CSSF 2012 Annual Report its Director General Jean Guill wrote:

During the year under review, the CSSF focused heavily on the importance of the professionalism, integrity and transparency of the financial players. It urged banks and investment firms to sign the ICMA Charter of Quality on the private portfolio management, so that clients of these institutions as well as their managers and employees realise that a Luxembourg financial professional cannot participate in doubtful matters, on behalf of its clients.

Almost ten years after the collapse of Landsbanki, equity release clients of Landsbanki Luxembourg are still waiting for the promised investigation, wondering why the liquidator is so keen to soldier on for a bank that certainly did participate in doubtful matters.

*In court, the French singer Enrico Macias mentioned that all his documents were in English. I found this strange since I had seen documents in French from other clients and knew there was a French documentation available. When I asked Landsbanki Luxembourg clients this pattern emerged. All the clients asked for contracts in their own language. When the non-French clients asked for contracts in English they were told the documentation had to be in French as the contracts were operated in France. Conversely, the French were told that the language was English as it was an English scheme. I have now seen this consistent pattern on documents for the various clients. – Here is a link to all Icelog blogs, going back to 2012, related to the equity release loans. Here is a link to the Landsbanki Luxembourg victims’ website.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.