Jim Ratcliffe and his feudal hold of Icelandic salmon rivers and farming communities

The largest landowner in Iceland owns around 1% of Iceland, mostly land adjacent to salmon rivers in the North East of Iceland – and he is not Icelandic but one of the wealthiest Brits, James or Jim Ratcliffe, a Sir since last year, of Ineos fame. His secretive acquisitions of farms with angling rights have been facilitated by the Icelandic businessmen who for years have been investing in salmon rivers through offshore companies. Opaque ownership is nothing new. Though the novelty is the grip on these rivers now held by a foreigner, with no ties to the community and assets valued at just above the Icelandic GDP, the central problem is mainly the nationality of the owner, but the concentration of ownership.

“If you are doing honest business, I assume you would feel better if you could talk freely about it. This secrecy breeds suspicion,” says Ævar Rafn Marinósson, a farmer at Tungusel in North East Iceland. The secretive business he is talking about is the business of buying farms adjacent to salmon rivers in his part of Iceland.

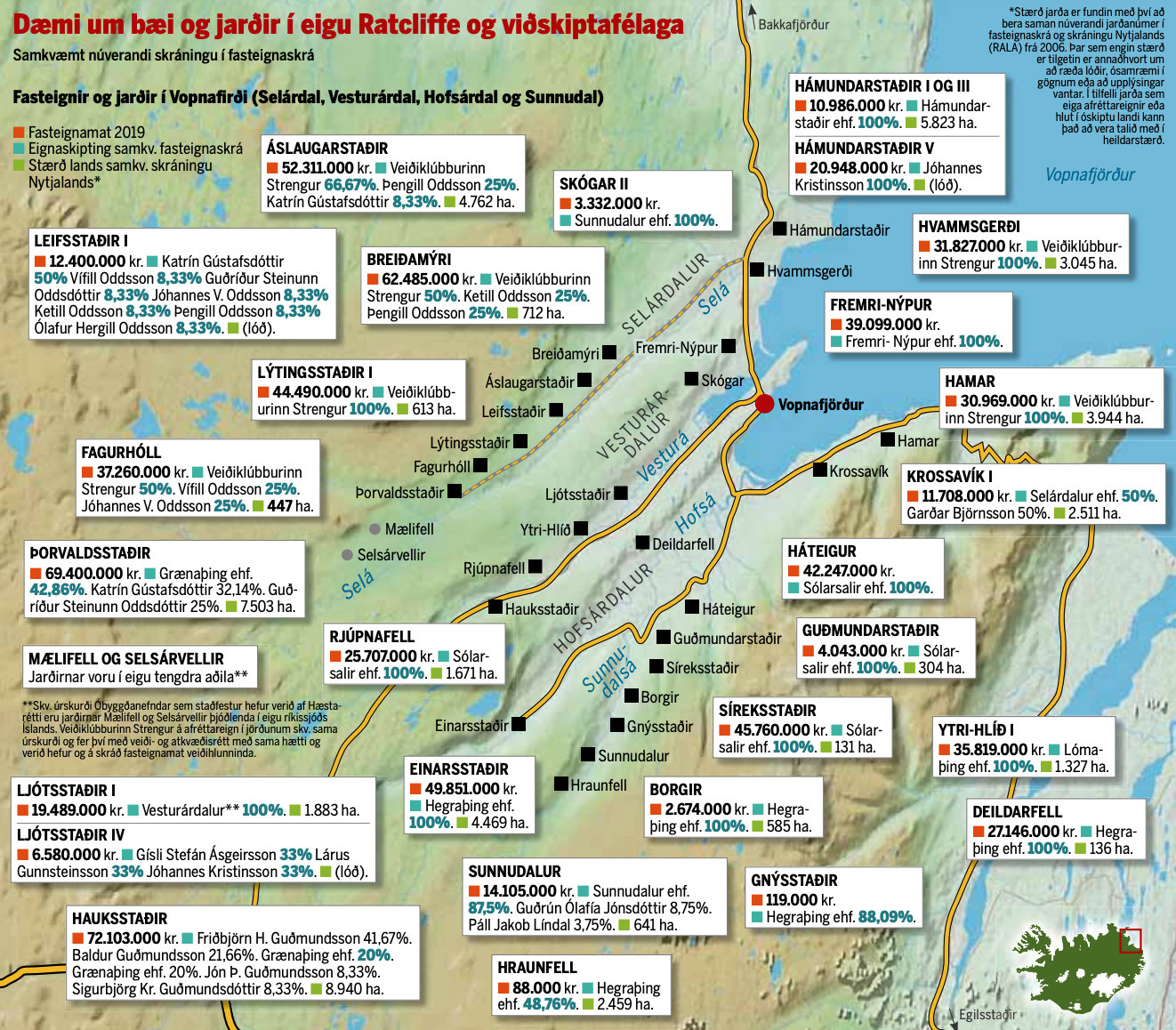

The secrecy is not new: for more than a decade, the ownership of the attractive salmon rivers in Iceland has been hidden in an opaque web of on- and offshore companies. That opacity might now hit the community when rivers and land is increasingly being held by one man, Jim Ratcliffe, whose assets are estimated £18.15bn. Through direct and indirect ownership, Ratcliffe owns over forty Icelandic farms concentrated in and around Vopnafjörður, which gives him the control of angling rights in some of the best salmon rivers in Iceland.

The petrochemical giant Ineos is Ratcliffe’s source of wealth. Interestingly, his salmon investments are part of his recent, rapidly growing investment in sport, from cycling, sailing and football to his, so far, tentative interest in British Premier League football clubs with price tags of billions. Ratcliffe claims that his petrochemical industries are run in an environmentally friendly way and strongly denies that his sport investments are any form of green-washing.

The secrecy surrounding Ratcliffe’s Icelandic investments, so out of proportions in this rural community of salmon and sheep farmers, has bred both rumours and suspicion that splits apart families, neighbours and the local communities as they debate whether the funds on offer are a substitute for losing control of the angling and the land.

Also, because Ratcliffe is a distant owner. He leaves it to his Icelandic representatives to talk to the farmers some of whom, like Marinósson, refuse to sell and as a consequence feel harassed. And then there are the pertinent questions of how Ratcliffe’s funds flow into the local economy, as one farmer opposed to Ratcliffe’s growing hold of the region, mentioned in an interview in the Icelandic media.

Following Ratcliffe’s purchases, foreign ownership of land is now a hot topic in Iceland. The government is looking at legal restrictions to limit foreign ownership. A new poll shows that 83.6% of Icelanders support this step. – But that might be a mistaken angle: the problem is not foreign ownership but concentrated ownership.

“I’m not upset with Ratcliffe, he’s just a businessman pursuing his interests. I’m upset with the government of Iceland that is letting this happen,” says Marinósson. He is not the only one to point out that a new legislation might come too late for the salmon rivers in the North East.

Angling – strictly regulated

Though far from being a mass industry, angling has long been both a beloved sport in Iceland and attracted wealthy foreigners. In the early and mid 20th century, English aristocrats came to fish in Iceland. In the 1970s and 1980s, the Prince of Wales was fishing in Hofsá, now controlled by Ratcliffe. With the changing pattern of wealth came high-flyers from the international business world.

As angling interest grew, net fishing for salmon was restricted so as to let the angling flourish. In 2011, 90% of the salmon caught in Iceland was from angling. The annual average salmon catch is around 36.000 salmon, with the figures jumping over 80.000 in the best years. There are in total 62 salmon rivers with 354 rods allowed; the rivers in the North East are thirty, with 124 rods (2011 brochure in English; Directorate of Fisheries).

According to the Salmon and Trout Act from 2006, the fishing rights are privately owned by those who own the land adjacent to rivers and lakes. The fishing rights come with a string of obligations, supervised by the Directorate of Fisheries and most importantly: the fishing rights cannot be split from the land – the only way to control the angling is to own a farm or farms holding the angling right.

The owners of the farms owning a river or lake are obliged to set up a fishing association to manage the angling; both the necessary investment and the profit has to be shared according to the amount of land owned. The ownership is split according to voting rights and percentage owned.

Wielding control over the angling, these associations can decide either to manage the angling themselves or lease out the rights to angling clubs or other consortia.

From overfishing to highly regulated angling regime

Already in the 1970s, the fishing associations run by the farmers owning the best salmon rivers were increasingly leasing out the angling rights to groups of wealthy Icelandic anglers, mostly business men from Reykjavík.

In some rare cases, foreign anglers who frequented Iceland, held the angling rights through a lease. One attractive salmon river in the North East, Hafralónsá, where Ævar Rafn Marinósson and his family are among the owners, was leased by a Swiss angler from 1983 to 1994; from 1995 to 2003, a British and a French angler leased the river.

During the 1990s, the popularity of angling led to overfishing in many salmon rivers with tension between biology and the financial profits from the angling rights. But the owners of the angling rights quickly came to understand that overfishing would kill the goose laying the golden eggs, or rather the salmon that brought wealth to the community.

The angling is now restricted in many ways: each river has only a certain number of rods; the angling time is restricted to certain hours of the day and a certain amount of annual angling days, often 90 days, from mid-June.

In addition, some form of “fish and release” is in place in most if not all the highly sought after and expensive salmon rivers. All these protective measures have been driven by those who control the angling, i.e. the fishing associations owned by the landowners.

Foreign anglers mainly pursue the sporty fly-fishing, whereas Icelanders tend not to frown upon using spoons and worms. Icelandic anglers know it is good to fish with spoons and worms after the foreign fly-anglers have been “beating the river” as we say in Icelandic. That normally ensures great catch, a trick the Icelandic anglers are happy to use.

Angling – from farmers to wealthy business men

The leases related to the salmon rivers normally run for some years. The fees to the fishing associations are a significant part of income for the farmers. The lessees are normally obliged to undertake investment in the infrastructure around the river.

Part of cultivating the salmon population in the rivers is expanding the habitat. This is for example done by building “salmon-ladders,” enabling the salmon to migrate beyond waterfalls or other hindrances, potentially increasing the rods allowed in each river and thus making the river more profitable.

Those who rent the rivers try to sell each rod at as high a price as the market can tolerate. Angling in the best rivers in Iceland is an expensive sport, also because the fishing is sold as a package with accommodation and meals included.

No longer primitive huts, the best fishing lodges are like boutique hotels, where the best chefs in Iceland come and cook for discerning anglers with the wines to match. Part of the summer news in the Icelandic media is reporting on the number of salmon caught in the well-known rivers, size and weight, what tools were used and sometimes also who is angling where.

This is the angling of the very wealthy. But angling is also popular with thousands of ordinary Icelanders. Angling for salmon, trout and sea trout in less famous rivers and lakes, is an affordable and ubiquitous sport in Iceland.

The opaque ownership web that Ratcliffe is buying into

Incidentally, this development of buying farms, not just licensing the angling rights, has been going on in Iceland for decades. In the early 1970s, a medical doctor and keen angler in Reykjavík, Oddur Ólafsson, bought five farms along Selá. Decades and several owners later these farms are now owned by Ratcliffe.

Orri Vigfússon (1942-2017) was a businessman and passionate angler, who in 1990 set up the North Atlantic Salmon Fund as an international initiative in order to protect and support the wild North Atlantic salmon. Vigfússon was influential in Icelandic angling circles and well known in angling circles all around the North Atlantic. He was also primus motor in Strengur, a company that for decades has controlled the best rivers in the North East, now controlled by Ratcliffe.

The web of on- and offshore companies related to angling has been in the making in Iceland since the late 1990s, when the general offshorisation of wealthy Icelanders boomed through the foreign operations of the Icelandic banks. A key person in this web is an Icelandic businessman.

Born in 1949, Jóhannes Kristinsson has been living in Luxembourg for years. Media-shy in Iceland he was in business with flashy businessmen like the duo Pálmi Haraldsson and Jón Ásgeir Jóhannesson of Baugur fame, synonymous with the Icelandic boom before the 2008. Kristinsson seems to be linked to around 25 Icelandic companies.

By 2006, it was attracting media attention in Iceland that wealthy anglers were no longer just licencing the angling rights but were outright buying farms holding angling rights. One name figured more often than others, Jóhannes Kristinsson. In an interview at the time, Kristinsson said he probably owned only one farm outright but was mostly a co-owner with others, without wanting to divulge how much he owned.

The farmers felt they knew Kristinsson, a frequent guest in the North East and the opaque ownership did not seem much of an issue. However, the effect of the opacity is now becoming very clear as Kristinsson is selling to a foreigner with no ties to the community, leaving the community potentially little or no control over some of its glorious rivers and land.

Luxembourg, Ginns and Reid

Kristinsson’s ownership of lands and rivers in the North East seems to have been held in Luxembourg from early on. Dylan Holding is a Luxembourg company, registered in 2000, by BVI companies, which Kaupthing owned and used to offshorise its clients. No beneficial owner is named in any of the publicly available Dylan Holding documents but the company was set up with Icelandic króna, indicating its Icelandic ownership.

According to Dylan Holding’s 2018 annual accounts, the company, still filing accounts in Icelandic króna, held assets worth ISK2.6bn. Its 2017 accounts list eleven Icelandic holding companies, fully or majority-owned by Dylan Holding, among them Grænaþing. Last year, Ratcliffe bought Grænaþing, as part of the deal with Kristinsson; an indication of Kristinsson being the beneficial owner of Dylan Holding.

The names of two of Ratcliffe’s trusted Ineos lieutenant, Jonathan F Ginns and William Reid, are closely linked to Ratcliffe’s Icelandic ventures as to so many other Ratcliffe ventures. According to UK Companies House, Ginns sits or has been on the board of over seventy Ineos/Ratcliffe related companies, Reid on seven.

Ginns and Reid sit on the boards of three Icelandic companies previously owned by Dylan Holding indicating that these companies are now under Ratcliffe’s control. Whether Ratcliffe has bought Dylan Holding outright or where exactly his ownership stands at, remains to be seen but it seems safe to conclude that Ratcliffe now owns significantly more land on his own rather than, as earlier, through joint venture with Kristinsson and others. Kristinsson seems to be withdrawing, leaving Ratcliffe as the sole owner.

Ratcliffe’s rapid rise to being Iceland’s largest landowner

Jim Ratcliffe, the angler with the funds to indulge his salmon passion was nr.3 on the Sunday Times Rich List this year, with assets valued at £18.15bn, down from £20.05bn in 2018, when he ranked nr.1. A Brexiteer who is not waiting for Brexit to happen: after relocating to the UK from Switzerland, where Ratcliffe and Ineos were domiciled from 2010 until some months after the EU referendum in 2016, Ratcliffe moved to Monaco last year. Tax and regulation seem to be his main concerns.

Ratcliffe had been fishing in Vopnafjörður for some years without attracting any attention. It was not until late 2016, when he visibly started buying into the Icelandic angling consortia, that his name first appeared in the Icelandic media. By then, he already owned eleven farms in the area, both through sole ownership and through his share in Strengur. Local sources believe Ratcliffe started investing earlier in angling assets, hidden in opaque ownership structures.

In December 2016 it was announced that Ratcliffe had bought the major part of the single largest farmland in Iceland, Grímsstaðir. This mostly barren wasteland of glorious beauty in the highlands beyond Mývatn had been owned by Grímstaðir farmers and their families for generations. The Icelandic state was a minority owner and has retained its share of the land. Ratcliffe stated at the time he was buying Grímsstaðir because it was part of the Selá water system; buying the land was part of his plan to support and protect the wild salmon.

The Grímsstaðir deal drew a lot of media attention in Iceland because in 2011, a Chinese businessman and poet, Huang Nubo, had tried to purchase this land with unclear intentions. Nubo had some Icelandic friends from his university years but practically no assets abroad except some real estate in the US, which he seemed to struggle to maintain. In 2014, the Icelandic government vetoed Nubo’s plans: he was not European, and his plans lacked clarity.

For decades, Strengur, under changing ownership, has managed the angling rights in Selá and Hofsá, two of the best salmon rivers in the North East and bought up farms adjacent to the rivers. In 2012, a new 960sq.m fishing lodge opened by Selá, a good example of the investment done in order to improve the angling experience and cater to wealthy anglers.

Following a 2018 transaction Ratcliffe owns almost 87% of Strengur, a jump from the 34% he had owned earlier, meaning that he controls the angling rights in both Selá and Hofsá. Ratcliffe bought the 52.75% by purchasing a company owned by Jóhannes Kristinsson. Strengur’s director Gísli Ásgeirsson (who features in this Ineos PR video) is now seen as Ratcliffe’s mouthpiece. He has ties to around twenty Icelandc companies, many of which are linked to Kristinsson.

The Ratcliffe Kristinsson consortium now owns 40 to 50 farms. But Ratcliffe is looking for more: earlier this year, Ratcliffe added one farm to his Icelandic portfolio. He now seems trying to secure ownership of yet another river, Hafralónsá.

The Icelandic media had reported that he had now secured majority in the angling association of that river but that does not seem to be the case. Ævar Rafn Marinósson is one of the owners of Hafralónssá. He says to Icelog that as far as he knows, Ratcliffe is still a minority owner.

The suspicion among those who are not in Ratcliffe’s fold is rife as a change in ownership might bring about drastic changes. With majority hold, Ratcliffe might for example drive the farmers in minority to bankruptcy by forcing through investments in the Hafralónsá angling association, which would wipe out the profits that make an important part of the farmers’ annual income.

Ratcliffe’s representative made Marinósson an offer to buy his farm. His answer was that the farm, which he owns with his parents, was not for sale. The representative then visited his elderly parents with the same offer, although it had been made clear to him that the farm was not for sale.

Misinformed passion

In a PR video from Ineos, Jim Ratcliffe talks of “overfishing and ignorance” that threat the salmon populations in Iceland. In the video Ratcliffe’s passion for salmon fishing is given as his drive for investing “heavily in the region to help expand the salmon’s natural breeding grounds” through constructing of salmon ladders in six rivers. The latter part of the video is about his investment in safari parks in Africa, with both initiatives presented as rising from Ratcliffe’s environmental concerns.

As mentioned earlier, the times of overfishing in Icelandic salmon rivers are long over. To portray Ratcliffe as a saviour of the salmon rivers in the North East is at best misinformed, at worst profoundly patronising to the farmers who have lived and bred salmon all their live and whose livelihoods have partly depended on the silvery fish. But the fact that Ratcliffe has the funds to follow his passion cannot be disputed.

In August this year Ineos Technology Director Peter S. Williams signed an agreement on behalf of Ratcliffe with the Marine and Fresh Water Institute in Iceland, where Ratcliffe takes on to fund salmon research to the amount of ISK80m, around £525.000. At the time it was announced that any profit from Strengur will be ploughed into maintaining and supporting the salmon populations in the rivers that Strengur controls. Strengur’s director Gísli Ásgeirsson said at the time that the aim was sustainability in cooperation with the farmers and local councils. There will be those in the local community who feel that cooperation is exactly what is lacking.

In a Rúv tv interview I did with Ratcliffe in 2017 (unfortunately no longer available online), Ratcliffe said he was driven by his passion for angling and the uniqueness of the unspoiled nature in Iceland, a value in itself. There is some speculation in Iceland that Ratcliffe’s angling investments might be driven by something else then his passion for angling.

Some think water as commodity in a world facing water shortage is his real interest, which would explain his emphasis on buying the rivers outright instead of joint venture or just renting the angling rights. Others, that plans by Bremenport to build a port in nearby Finnafjörður in order to service the coming Transpolar Sea Route might be in Ineos’ interest. Again, total speculation but heard in Iceland. – Ineos is investing in facilities in Willhelmshaven, where Bremenport is building a new container terminal.

Mushrooming sport investment: from millions in salmon and safari to, possibly, billions in Premier League football

Ratcliffe’s UK holding company for his Icelandic assets is Halicilla Ltd, incorporated in 2015, its business being “mixed farming.” Halicilla’s 2017 accounts list two Icelandic companies as assets, Fálkaþing, incorporated in 2013 and Grenisalir, incorporated in 2016, “Icelandic companies, which in turn hold land and fishing rights.”

Ratcliffe has been unwilling to divulge how much he has invested in Iceland but that can be gleaned with some certainty from the Halicilla accounts: its assets amounted to £9.7m in 2016, which with further acquisitions in 2017, had grown to £15.3m by the end of 2017, financed directly by the shareholder, i.e. Ratcliffe.

In addition to investments in Icelandic salmon rivers, Ratcliffe’s sports investments have mushroomed in the recent years. In December 2017, he announced his investment in luxury eco-tourism project in safari parks in Tanzania through a UK company, Falkar Ltd, incorporated in 2015. As Halicilla, Falkar is financed by Ratcliffe, with a loan of £6.3m, at the end of 2017. With his interest in sailing, Ratcliffe owns two yachts, one of them, Hampshire II a superyacht worth $150m, with two of his Ineos partners owning three yacths. In addition, Ratcliffe owns four jets, three Gulfstream jets and one Dassault Falcon.

Ratcliffe’s other sport investments involve much higher figures than his investments in salmon and safari. Last year, he invested £110m in Britain’s America’s Cup team. His investment in March in the cycling Team Sky, now Team Ineos, seemed to imply that the Team’s earlier budget of £34m would increase significantly. In 2017 he bought the Lausanne-Sport football club, where his brother is now the club’s president, and has recently completed a £88.7m deal to buy Ligue 1 club Nice.

The figures might rise: last year, Ratcliffe led an unsuccessful bid of £2bn for Chelsea FC and has aired his interest to buy his favourite team, Manchester United – one day, some super-star footballers might be practicing fly-fishing under Ratcliffe’s instructions in Vopnafjörður.

Split families and farming communities, threats and bullying

The farmers in the North East face a dilemma. It is in the interest of farmers to be able to sell their farm for a reasonable price if they intend to retire or give up farming for other reasons. However, seeing whole fjords and entire rivers now owned not by a consortium of wealthy anglers in Reykjavík but by a single foreigner, wholly unrelated to the country and the North East, with a strangle hold on the community, has spread unease.

When the Icelandic consortia started buying farms in order to gain control of the angling, the farmers often continued to live on the farm, as tenants. On the whole, the farms have continued to be farmed, though there are exceptions.

Ratcliffe has stated he is keen for the farmers to keep living on the farms and has offered them to stay as tenants. With money in the bank the tenants can profit from the land as earlier but no longer benefit from the angling rights as earlier or have any say on the use of the river.

Ratcliffe’s acquisitions have completely changed the game around the rivers. The novelty is his immense buying power. His entrance into the angling circles has split families and communities. To sell or not to sell is a burning question for many since Ratcliffe’s representatives keep making lucrative offers to the few farmers who have so far been unwilling to sell.

This is, as such, not entirely Ratcliffe’s fault – he simply has an exorbitant amount of money to indulge in one of his hobbies though he has shown little interest in learning from the farmers who know the rivers like the back of their hands. But this sowing of anger and unease has been the side effect of his investments. Perhaps also to some degree because of the people he has chosen to work with in Iceland; how well informed Ratcliffe is of the circumstances surrounding his investments is unclear.

Ratcliffe flies in and out of Iceland. The Icelanders who work for him are there and some live in the communities Ratcliffe has already bought or is trying to buy. His salmon shopping spree may be backed by the best intensions, but the side effect is effectively making him the ruler of a few hundred Icelanders who live off the land they love dearly. The land, which Ratcliffe visits at his leisure, once in a while.

Restrictions on ownership of land may come too late for the North East

Foreign ownership is a hot topic in Iceland for the time being, given the quick and enormous concentration of Ratcliffe’s ownership in the North East. But it would be wrong to focus on foreign ownership – the real problem is concentrated ownership.

Ratcliffe is not the only foreign landowner in Iceland. There are a few others but there is increased interest from abroad for land in Iceland. One foreign owner closed off his land with signs of “Private road,” much to the irritation of his Icelandic neighbours since free passage in the country side is seen as a general right in Iceland. One practical reason is the gathering of sheep: sheep roam freely in summer and farmers need to roam just as freely when the sheep is gathered in autumn.

Though rapidly developing, luxury tourism is still a rarity in Iceland, and has so far not led to land being closed off. As Ratcliffe’s Tanzania investment shows, he is interested in luxury tourism. Seeing angling turning into an even more rarefied luxury than it already is, marketed mainly for people in Ratcliffe’s wealth bracket, is not an enticing thought for most Icelanders.

The government led by Katrín Jakobsdóttir, leader of the Left Green party (Vinstri Grænir), with the Independence party (Sjálfstæðisflokkur) and the Progressives (Framsóknarflokkur), is now under pressure to consider means to limit foreign ownership. A working group has been gathering material and new law is promised this coming winter. One step in the right direction of focusing on concentrated ownership, not just foreign ownership, would be to reintroduce pre-emptive purchase rights of local councils, abolished in 2004.

Finding the proper criteria that drive rural development in the right direction will not be easy. But Icelanders are certainly waiting for that to happen – having stratospherically wealthy people, Icelandic or foreign, owning entire rivers and fjords on a scale not seen since the time of the feudal lords of the Icelandic sagas is not seen as positive rural development. When law is finally passed, it might be too late to prevent that to happen in the North East.

*This image is from a July 21 July 2018 article on Ratcliffe’s acquisitions in the Icelandic daily Morgunblaðið and shows ownerships of farms in Vopnafjörður (there are other farms in the neighbouring communities.)

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Qjirphd

[email protected]

:

Wfdfyew

24 Aug 20 at 9:10 am

rjkczkague

Arcanescarkague

19 Oct 21 at 11:23 pm

Mqmewde

[email protected]

:

Wlnbeyp

21 Oct 21 at 1:40 pm

milashakague

yfneyzkague

22 Oct 21 at 10:51 pm

flfvsxkague

vfhbyzkague

18 Nov 21 at 11:38 pm

Doomwindkague

anastasyushkakague

21 Nov 21 at 10:54 pm

frcifkague

ktrczkague

23 Dec 21 at 2:52 am

Jurassiakague

ctyhfkague

21 Jan 22 at 2:57 pm

Kirillichkague

Fusselmankague

25 Jan 22 at 6:42 am

avdhohakague

kiryunyakague

16 Feb 22 at 1:52 pm

Gjebarb

[email protected]

:

Dnchxab

16 Feb 22 at 11:54 pm

vtktifkague

vfyfkague

19 Feb 22 at 6:45 am

Reshegakague

Arlenakague

21 Mar 22 at 6:29 am

Michaelkague

Nikolashakague

24 Mar 22 at 11:04 am

aluniakague

Monyakague

18 Apr 22 at 12:04 am

Naderikague

Larakague

21 Apr 22 at 1:23 pm

left

lega

22 May 22 at 11:03 am

fgjkkbyfhbz

fgjkkbyfhrf

25 May 22 at 3:02 pm

Kornilich

Kornyukha

20 Jun 22 at 6:24 pm

andya

Anener

24 Jun 22 at 4:02 am

him

himiliana

21 Jul 22 at 1:35 pm

Solinger

Solverson

24 Jul 22 at 1:25 pm

karinka

Karisar

23 Aug 22 at 8:46 am

bynf

bytccf

26 Aug 22 at 6:29 pm

yfcnf

variant2

yfcnfc

18 Sep 22 at 12:22 am

gjkbrcif

variant2

gjkbrctybz

21 Sep 22 at 1:12 am

Helloł jestem znany pod imieniem Jacek. Adwokat Rzeszów z moją pomocą zdobędziesz od ręki. Aktualnie moim miejscem zamieszkiwania jest imponujące miasto Serock. Adwokat Rzeszów w Polsce a kredyty zaciągnięte w Profi Credit.

adwokat odszkodowania rzeszów

18 Dec 22 at 1:24 am

https://casinofa.github.io

DonaldEcows

18 Feb 23 at 6:49 pm

paxlovid buy https://paxlovid.life/# paxlovid buy

Paxlovid

25 Jul 23 at 1:23 pm

Szukasz pomocy w oddłużaniu? Zapraszamy na naszą stronę.

Oddłużanie

23 Aug 23 at 2:38 am

After examine a couple of of the weblog posts on your website now, and I really like your approach of blogging. I bookmarked it to my bookmark website record and can be checking again soon. Pls try my website online as nicely and let me know what you think.

kyrie 6

19 Sep 23 at 4:01 pm

mail order pharmacy india https://indiapharmacy.guru/# – online pharmacy india

IndiaPh

22 Dec 23 at 4:22 am

buy prescription drugs from india best india pharmacy top 10 pharmacies in india indiapharmacy.guru

IndiaPh

22 Dec 23 at 4:32 am

This article is absolutely outstanding. The level of detail and the clarity of your writing are exceptional. You’ve managed to convey complex ideas with remarkable precision and accessibility. I’m grateful for this valuable contribution. Best wishes, Pasang Iklan Properti Gratis

Pasang Iklan Sewa Hotel

25 Oct 24 at 12:30 am

Such a great find Regards from Pasang Iklan Properti Gratis

Pasang Iklan Jual Rumah

21 Dec 24 at 4:13 am

Saya sangat terkesan dengan bagaimana artikel ini menjelaskan topik yang kompleks dengan cara yang begitu jelas dan mudah dipahami. Anda benar-benar menguasai materi ini. Terima kasih banyak atas karya yang sangat bermanfaat ini. Salam sukses, Pasang Iklan Properti Gratis

Cara Iklan Apartemen

21 Dec 24 at 9:51 pm

Artikel yang inspiratif, pantas mendapatkan komentar. Salam dari : IDProperti.com | Pasang Iklan Properti Gratis

Iklan Jual Beli Rumah

22 Dec 24 at 12:31 am

With family members or sole follow makes you more efficient.

ジュニアNISA今年いつまで楽天証券

22 Mar 25 at 12:32 pm