Archive for the ‘Iceland’ Category

The only secret from October 6 2008: a CBI loan of €500m to Kaupthing – updated (again)

Although plenty is known about the collapse of the three Icelandic banks, given the SIC report, there is still one major unknown chapter in this saga: a loan of €500m granted by the Central Bank of Iceland to Kaupthing on October 6 2008, due to be repaid four days later. It is clear that about half of this loan will never be repaid. Now a parliamentary committee is investigating the loan. The only documentation of the loan is a recording of the phone call between David Oddsson then governor of the CBI and prime minister Geir Hard but so far the CBI is not assisting.

At 4pm on October 6 2008 prime minister Geir Haarde addressed the stunned nation on all media channels ending his speech with ,,god bless Iceland” – an uncustomary ending in a country where god is seldom called upon in the political realm. Interestingly, Haarde did not say the banks were failing but he talked at length about the dire situation abroad, which now could also be felt in Iceland with its outsized banks compared to the country’s economy. In these tough times for banks in many countries, he said deposits in Iceland were safe and the government would in the coming days do its utmost to hinder chaos and confusion in case “the Icelandic banks become un-operational to some extent.” He also announced the emergency legislation, which was passed later that day.

But when did the prime minister and the government actually known that the end of the banks was nigh and unavoidable? In the SIC report Haarde, Ossur Skarphedinsson minister of foreign affairs, trade and banking minister Bjorgvin Sigurdsson and minister of finance Arni Mathiesen all recount they understood this around 2am on this fateful October 6 when the ministers met three bankers from JP Morgan, called to Iceland to advise the Central Bank of Iceland. At this late hour, the three foreigners explained in a few but clear and concise words that there really was nothing to be done – the three banks were beyond salvation.

“… this was a really weird moment,” said Sigurdsson in his statement to the SIC. “Suddenly this was clear like morning light. The man just drew it on the white-board. Just all of a sudden. This was a sort of moment of truth after this insane roller coster ride weekend, which was in hindsight perhaps more or less based on wishful thinking.” (SIC report, vol 7, p. 104; only in Icelandic). – That is what it felt like to realise that the Icelandic banking system was failing: a simple drawing on a white-board.

At this meeting, Haarde finally realised he would have to address the nation and pass the emergency legislation and that is what he sat in motion as the day dawned.

On October 27 2008 the CBI put out a press release saying that on October 6 it had, after conferring with the prime minster, issued a loan of €500m to Kaupthing in order for the bank to meet its obligations to UK authorities related to the bank’s UK subsidiary.

What is known about this loan is that there is no proper documentation in the CBI regarding it. The only tangible evidence of the loan having been issued is apparently a recording of a phone call between the then governor of the CBI David Oddsson and Haarde. Kaupthing held some sort of “receipts” (but nothing resembling a loan agreement or any other formal documentation) for this amount having been paid to the bank. The loan had maturity four days later – i.e. it was a bridge loan but yes, an awfully short bridge. The collateral was nothing less than Kaupthing’s Danish subsidiary FIH Bank, at the time reckoned to be worth €670m and the interest rates set at 9%.

That Monday in the late afternoon, the loan was paid from a CBI account abroad into Kaupthing’s account with Deutsche Bank in Frankfurt in three instalments, totalling €500m. If or how it left Deutsche is not known. The €500m might have been enough to salvage Kaupthing Singer & Friedlander – the preceding week the FSA had demanded that £400m be paid as a guarantee since money was flowing fast out of the bank – but the €500m never seemed to reach the UK authorities.

The loan was not repaid four days later. Eventually, the CBI sold the collateral but the sale only brought in around half of the loan and less, if interest rates are taken into account. Consequently, this undocumented loan has caused the Icelandic state a huge loss of about €250m.

All this is now known – but it is still unknown why CBI and the prime minister thought it was necessary, let alone a good idea, to issue a loan of ca 4% of the bank’s total foreign currency reserve to a bank, which by the time the loan was issued hardly seemed a going concern. When and why the Kaupthing managers secured this loan is not known. It is not clear why the CBI issued a loan without any proper documentation or why, if there was no time right on the Monday, this was not put in place in the following days. And if the CBI really intended the loan to shore up the Kaupthing UK operations why did the bank not pay the money directly to the UK authorities?

A year ago, an Icelandic parliamentary committee started enquiring about this loan, which had caused the state such a loss. When it transpired that the only documentation regarding the loan is to be found in the recording of the phone conversation of the CBI governor and the prime minister the committee asked for a transcript. So far, the CBI has procrastinated. Last week, when the committee was finally going to publish a report on its findings, obviously pointing out the CBI’s lack of answer, the CBI sent a letter to the committee saying it was considering its options. It hinted at the possibility of inviting the committee to read the transcript but then backtracked and has since been quiet on the issue.

Thus stands this intriguing story, so far without an ending. The report by the parliamentary committee might now be published in the coming days but apparently without information from the transcript.

There is however no lack of rumours and guesses as to why this loan was issued and what it was bridging. The most persistent rumours regard Kaupthing’s alleged Russian clients but it should be stressed that nothing has ever surfaced to corroborate the rumours. There is however a Russian element in the collapse saga: on October 7, the prime minister announced Russia was lending Iceland €4bn to strengthen its foreign reserve. This loan never materialised and it was never clear how this “offer” was made or by whom.

*The Icelandic Parliament has now published its report (in Icelandic but it is short; alors, Google translate is an option) – without an answer from the CBI on the transcript of the fateful telephone call mentioned. All the facts re the loan mentioned above can be found in the report.

**Update 31.3. 2013: Geir Haarde has recently stated that the recording of his conversation with CBI governor Oddsson was done without his knowledge and he would not agree that it was made public. As in many other countries, it is illegal in Iceland to record a phone conversation without making others on the call aware of it.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

The al Thani Kaupthing case on the horizon

The case that the Icelandic Office of the Special Prosecutor is bringing against three Kaupthing managers and Olafur Olafsson, at the time Kaupthing’s second largest shareholder, is coming up in the Reykjavik County Court today. It seems that now all legal quibbles the defendants brought up have been dealt with – all of them brushed aside – which means that the case can now take its course. Not quite now though, that will happen in mid April when the main proceedings are due to start. The Kaupthing managers charged are Sigurdur Einarsson, Hreidar Mar Sigurdsson and Magnus Gudmundsson.

This is by far the largest case brought so far by the OSP. There are fifty names on the witness list. One of them is the man who has given the case its name, Sheikh Mohammed bin Khalifa al Thani. The Sheikh is not accused of any wrongdoing and has not been charged but the OSP would like him to bear witness. It is not known if he will answer the request.

This case has been extensively dealt with on Icelog, i.a. here. The interesting UK angle to the story is that there are striking parallels of this loan story – a Middle Eastern investor being lent money by a bank to invest in that same bank, which then uses that investment as a sign of its rude health – in the Barclay story, also from 2008, now being investigated by the SFO, also covered earlier on Icelog.

Middle Eastern and Russian money is famously finding its way into many London-based investments and investment companies, adding glamour and building cranes to the city. The question is how sparkling clean and healthy all this money is – but as we know from the HSBC money laundering case even major banks are not too squeamish when it comes to the choosing their customers.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Myth-busting

It was good to see the FT (paywall) taking up some of the myths of Icelandic recovery. Funnily enough, Icelanders have not been the proponents of the idea that Iceland is some sort of a model. From early on, after the collapse in October 2008, foreign economists have looked to Iceland in search for arguments for their various ideas, often with quite misunderstood facts and/or context.

More on this later – I’ve often mentioned these myths and will do more of it – but I was intrigued to see my Economonitor article, co-written with professor Thorolfur Matthiasson, University of Iceland, quoted by the FT as the work of “two Icelandic experts.” The article shows that the cost to Iceland of the collapse of the banks has indeed been substantial, 20-25% of GDP. There are now 355 tweets and 205 Facebook shares of the Economonitor article so it is far to say it has had a lively distribution.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Crisis and the manifold damage of cheap money

Now that the financial markets have moved out of Euro crisis mode, at least for the time being, calm reigns again – or as much calm as you are likely to find in that testosterone driven sector. So far, not even a muddled election outcome in Italy has caused much market flurry. However, the Euro debts have not evaporated but with the enchanting words of Governor of the European Central Bank Mario Draghi and a EU banking union in spe debt-ridden Eurozone countries gain time to put its economies in order.

This calm allows us to reflect on the wider aspects of the financial crisis on both sides of the Atlantic, such as the contributing role of interest rates in the crisis. Normally, interest rates shot up in good times and sank in bad times but during the last twenty years the rates have more or less been low all the time in the US, the major European economies and, with the birth of the Euro, also in the Eurozone. Things tend to turn into laws of nature when they have been around for a while. The danger is that “chronic” low interests has turned into a law of financial nature, creating quite devilish problems of its own.

Let us look at interest rates in the US and the Eurozone.

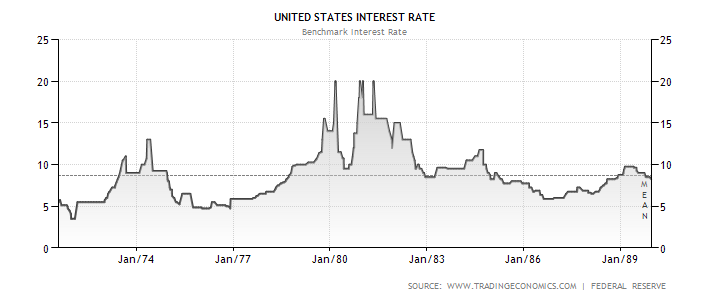

Table 1. US interest rates January 1971-December 1989.

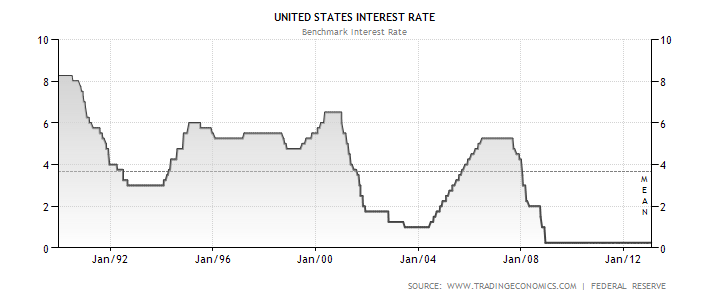

Table 2. US interest rates January 1990-March 2013.

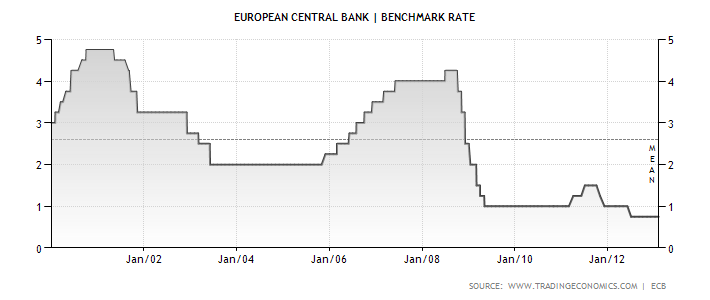

Table 3. ECB interest rates January 2000-March 2013.

In the US money has been cheap since 1990 and exceedingly cheap since 2000, compared to 1971-1990. The Euro, in existence from 2000, knows nothing but low interest rates. Consequently, funding cost in the developed world has been low. This has affected not only the behaviour in the financial sector but also sovereigns.

The 1990s and dotcom defying financial gravity

During the internet bubble of the late 1990s investment bankers, trying to be with it, took off their ties to bond with young dotcom visionaries brimming with bright but unproven ideas. When the tie-less bankers needed to calm their “tied” colleagues, who disbelieved that businesses with no profits in sight could be good investment, they explained that these new businesses were governed by new information age laws beyond the understanding of anyone except the dotcom-initiated.

Of course things proved to be less different than it had seemed. And so the new millennium started with the reaffirmation of the old rule that things are only worth as much as someone is willing to pay. Great losses ensued from the new age not being new and from other fallacies. In 1998, the demise of an obscure hedge fund called Long Term Capital Management – two of its board members, Myron S. Scholes and Robert C. Merton, won the Nobel Prize in economics in 1997 – threatened to bring down the US financial system. The New York Federal Reserve quietly organised a $ $3.625bn bailout by the fund’s largest creditors. Thus ended a decade with – in historical perspective – low interest rates. But yet lower rates were still to come – and even greater losses, this time not absorbed by creditors but tax-payers.

Cheap money, revolving doors, light/no-touch regulation

At the time it seemed like a good idea to start the new European currency with low interest rates; in making their decisions European central bankers looked to the US where interest rates had started to fall even before 9/11. The belief in light-touch, or almost no-touch, regulation inherited from the 1990s also took firm hold on both sides of the Atlantic.

The first decade of the new millennium was thus marked by historically low interest rates, pared down regulation and hands-off financial supervision. Another new feature was the revolving door between banks and their regulators. This back-and-forth enmeshed banks and their authorities in a spider web of cosy relations and friendships.

Money was so cheap that spending it poorly had little consequences. Banking was done like a Jackson Pollock painting: you took a really big canvas and splashed it with colours. It didn’t matter too much if it didn’t make sense – it looked fine in the annual reports written by auditors who knew how to make the balance sheets look good, with tools such as Lehman’s now so infamous Repo 105.

Cheap money, favours and the separation of debt and assets

When the appalling banking practises of the Icelandic banks were exposed in the Icelandic SIC report in April 2010, not only were widespread suspicions of shady dealing confirmed, but the report showed that what had gone on was much worse than anyone had imagined. Big international banks and auditors from the Big Four were also part of the new Icelandic saga of failed banks and extreme banking.

What the SIC report described, under the term “banking,” was in fact a double standard banking: while most clients were treated as any clients in an ordinary bank a small group of clients – the biggest shareholders and their satellites – were lent beyond legal limits, often against weak or no collateral. The financial rational was unclear but the bankers were certainly egged on by cheap money. Iceland has traditionally been a high-inflation high-interest country and when Icelandic bankers suddenly had access to almost unlimited low-interest loans abroad they behaved as if they were at an open bar for the first time in their lives: they binge-borrowed and binge-lent.

The last few years have shown that the favours during the boom years were greatly profitable to those who were allowed to binge-borrow. A mercenary army of specialised lawyers and accountants made sure that the cheap money turned into lasting favour. In galaxies of offshore companies debt was skilfully separated from assets. After 2008, one empty shell company after the other has collapsed, leaving behind astronomical debt and hardly any assets. The creditors, not only the failed banks but also pension funds, get next to nothing.

For every such bankruptcy it seems likely that previously underlying assets are tucked away offshore. Consequently, the Icelandic tycoons who profited from the binge-borrowing are, almost without exception, so far doing alright in spite of spectacular bankruptcies in companies previously owned by them.

Separating debt and assets was not unique to Icelandic tycoons. London remains one of the biggest offshore centres in the world with a large number of offshore specialists. The Irish media are following the gigantic asset struggle as Irish tycoons like Sean Quinn, Patrick McKillen and Derek Quinlan are fighting not to pay their debt to the public bodies that now hold debt from Irish banks, recapitalised by the state.

In all debt-ridden Euro-countries the crisis has exposed reckless – and often corrupt – lending that has enriched favoured clients who continue to profit. Lending fuelled by cheap money, made more reckless by securitisation as lenders did not need to fear the consequences of unsustainable lending.

The sovereign curse of the cheap

During the boom time of cheap money sovereigns like the UK were tempted to fiscal frivolity. Instead of cutting down borrowing, debts expanded. Even in frugal countries like Germany sovereign debt shot up. Cheap money meant there was little pressure on governments to think of necessary but difficult and complicated structural reform, such as labour market reform or competition.

In a recent article in Foreign Affairs, Fareed Zakaria sums up the effect of cheap credit in the US:

In poll after poll, Americans have voiced their preferences: they want low taxes and lots of government services. Magic is required to satisfy both demands simultaneously, and it turned out magic was available, in the form of cheap credit. The federal government borrowed heavily, and so did all other governments — state, local, and municipal — and the American people themselves. Household debt rose from $665 billion in 1974 to $13 trillion today. Over that period, consumption, fueled by cheap credit, went up and stayed up.

Pricing risk is now a much-discussed topic in finance. Under-priced risk in lending to countries like Greece is a case in point. Lending will always be seen as less risky in times of low interest rates – and with chronic low interest the risk assessment can be unhealthily affected.

The financial sector thrived and expanded with low interest rates and soft regulation. So much so that it became more powerful than the state bodies set to guard it. Certain financial institutions became too big to fail. Instead of punishing creditors it was mainly taxpayers in developed countries like the US and Europe who shouldered the losses of the financial sector. Debt from the private sector migrated effortlessly to the public sector. Now, the link between profit and risk was broken and those who pocketed profits no longer shouldered much risk.

There is no change in sight. In the present crisis-doomed atmosphere there are – for obvious reasons – few calls for higher interest rates. Yet, in Japan low interest rates have not solved the problem. All the money printed to sustain the low interest rates should have fuelled inflation but for some reason it has not happened. Maybe we are just postponing another even greater disaster with our low interest rates.

I am not arguing low interest rates is the only root to the troubles in the financial sector, that would be overly simplistic. But cheap money should be considered a contributing factor in the present financial misère and its curse takes on many forms.

Yes, we need proper structures to rein in the financial sector – splitting apart retail banking and investment banking, firm regulation and supervision, the next set of Basel rules etc – but all these measures with fancy names must do one simple thing: to prevent bankers from administering money as if were worthless.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Anyone remember the rating agencies?

In Iceland, the rating agencies and their uncritical look at the Icelandic banks isn’t likely to be forgotten soon. I have just blogged on the Icelandic experience, tied to other more recent examples, at the Left Foot Forward blog, see here.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Landsbanki Luxembourg victims’ website

Icelog has earlier dealt extensively dealt with the saga of the Landsbanki Luxembourg equity release loans. As pointed out there seem to be good reasons to question both how Landsbanki dealt with its customers before its demise in October 2008 and then later how the administrator has allegedly dealt with these loans, as well as ignoring questions regarding the Landsbanki Luxembourg operations.

The clients, mostly elderly people, have shown great resilience in drawing attention to questions seeking answers but the authorities in Luxembourg have not been too keen in taking up the issues raised by the group. One of many remarkable events was when the Luxembourg Prosecutor went out of his way to issue a press release defending the administrator, i.a. by throwing doubt on the victims’ motives, though he did not publish any tangible proof for these allegations.

As reported earlier, the group has now sought legal assistance and is seeking ways how best to proceed with their claims. The group has now open a website with all relevant information, contact details etc.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Iceland: reaping Icesave success – but capital controls are the unknown

Fitch Ratings have upgraded Iceland’s status – it is now BBB instead of BBB-. The upgrade, as a similar move by Moody’s recently, partly stems from the EFTA Court’s Icesave ruling, which has removed uncertainty of possible state liabilities. Fitch underlines the improved economic situation, not least the debt status of the sovereign, all moving in a positive direction and gives Iceland a slightly higher rating than Moody’s and S&P.

The capital controls are the great unknowns. But first, a few words on the situation in Iceland here and now, relevant to the capital controls.

In the wake of the collapse of the Italian political system, following the corruption investigations in the early 1990s, old powers in the new centre around Silvio Berlusconi found ways of conquering the political vacuum. The collapse of the Icelandic banks set the scene for similar movements, not only for power but for assets as well. Shortly after the collapse of the banks a person with a great insight into Icelandic society said to me that we would, in the coming years, see a fierce battle for assets and power in Iceland.

This battle is now taking place, centered around the ownership of the holding companies which control the two banks, Islandsbanki and Arion. The owners of these two holding companies are foreign creditors, ca half and half original creditors and funds that have bought claims. The crux of the matter is if the two holding companies will go through an orderly composition and a sale of asset at the best possible time or if the companies will be brought into bankruptcy, forcing them to sell off assets in a relatively short time, assumedly at a knock-down price.

Mar Gudmundsson governor of the Central Bank of Iceland has expressed that the best solution would be to sell one of these banks for foreigners who brought in fresh foreign currency. The delicacy of the situation is partly that whichever bank is sold first will, in a sense, knock down the price of the remaining one, especially if there are only Icelandic buyers interested.

The latest is that a fund owned by Icelandic pension funds, in conjunction with major shareholders of MP Bank, are negotiating a purchase of Islandsbanki. The group is led by Skuli Mogensen, who after leaving a bankrupt IT company OZ ca ten years ago, made his fortune in Canada, and like in a novel, returned to his homeland a rich investor, keen on building his fortunes there again. In MP Bank he has allied himself with two investors, who have previous Icelandic ties – David Rowland and Joe Lewis.

However, the “ruler” in deciding the turn of events re selling the two banks is the CBI. The bank will have the last word on agreements re the composition, which have to be weighed against the pressure on the Icelandic krona due to lack of foreign currency in Iceland. The CBI is well aware of the problems and yet, some forces in Iceland are trying to undermine its authority by insisting on political control and the role of the Parliament in deciding the fate of the two holding companies.

Before the privatisation of the Icelandic banks they were run like political fiefdoms. Following the privatisation, fully in place by 2003, the banks were still run as fiefdoms, this time with the largest shareholders as the bank ruling class. The publication of the SIC report drew a concise, insightful and bleak image of these convoluted alliances and power structures.

One way of understanding the ongoing struggle in Iceland re ownership of the two major banks is to see it as the attempt of those who used to rule, before 2008, to reclaim their position. Others might say that this sounds like fiction – but lets wait and see. The outcome of the elections will be a decisive factor in constructing the future of Iceland.

Now, back to Fitch. Below is the Fitch press release, emphasis is mine.

Fitch Ratings has upgraded Iceland’s Long-term foreign currency Issuer Default Rating (IDR) to ‘BBB’ from ‘BBB-‘ and affirmed its Long-term local currency IDR at ‘BBB+’. The agency has affirmed the Short-term foreign currency IDR at ‘F3’ and upgraded the Country Ceiling to ‘BBB’ from ‘BBB-‘. The Outlooks on the Long-term IDRs are Stable.

KEY RATING DRIVERS The upgrade reflects the impressive progress Iceland continues to make in recovering from the financial crisis of 2008-09. The economy has continued to grow, notwithstanding developments in the eurozone; fiscal consolidation has remained on track and public debt/GDP has started to fall; financial sector restructuring and deleveraging are well-advanced; and the resolution of Icesave in January has removed a material contingent liability for public finances and brought normalisation with external creditors a step closer.

The Icelandic economy has displayed the ability to adjust and recover at a time when many countries with close links to Europe have stumbled in the face of adverse developments in the eurozone. The economy grew by a little over 2% in 2012, notwithstanding continued progress with deleveraging economy-wide. Macroeconomic imbalances have corrected and inflation and unemployment have continued to fall. Iceland has continued to make progress with fiscal consolidation following its successful completion of a three-year IMF-supported rescue programme in August 2011. Fitch estimates that the general government realised a primary surplus of 2.8% of GDP in 2012, its first since 2007, and a headline deficit of 2.6% of GDP. Our forecasts suggest that with primary surpluses set to rise to 4.5% of GDP by 2015, general government balance should be in sight by 2016.

In contrast to near rating peers Ireland (‘BBB+’) and Spain (‘BBB’), Iceland’s general government debt/GDP peaked at 101% of GDP in 2011 and now appears to be set on a downward trajectory, falling to an estimated 96% of GDP in 2012. Fitch’s base case sees debt/GDP falling to 69% by 2021. Net public debt at 65% of GDP in 2012 is markedly lower than gross debt due to large government deposits. This also contrasts with Ireland (109% of GDP) and Spain (81% of GDP).

Renewed access to international capital markets has allowed Iceland to prepay 55% of its liabilities to the IMF and the Nordic countries.

Risks of contingent liabilities migrating from the banking sector to the sovereign’s balance sheet have receded significantly following the favourable legal judgement on Icesave in January 2013 that could have added up to 19% of GDP to public debt in a worst case scenario. Meanwhile, progress in domestic debt restructuring has been reflected by continued falls in commercial banks’ non-performing loans from a peak of 18% in 2010 to 9% by end-2012. Nonetheless, banks remain vulnerable to the lifting of capital controls, while the financial position of the sovereign-owned Housing Finance Fund (HFF) is steadily deteriorating and will need to be addressed over the medium term.

Little progress has been made with lifting capital controls and EUR2.3bn of non-resident ISK holdings remain ‘locked in’. However, Fitch estimates that the legal framework for lifting capital controls will be extended beyond the previously envisaged expiry at end-2013, thereby reducing the risk of a disorderly unwinding of the controls. Fitch acknowledges that Iceland’s exit from capital controls will be a lengthy process, given the underlying risks to macroeconomic stability, fiscal financing and the newly restructured commercial banks’ deposit base. However, the longer capital controls remain in place, the greater the risk that they will slow recovery and potentially lead to asset price bubbles in other areas of the economy.

Iceland’s rating is underpinned by high income per capita levels and by measures of governance, human development and ease of doing business which are more akin to ‘AAA’-rated countries. Rich natural resources, a young population and robust pension assets further support the rating.

RATING SENSITIVITIES The main factors that could lead to a negative rating action are: – Significant fiscal easing that resulted in government debt resuming an upward trend, or adverse shocks that implied higher government borrowing and debt than projected – Crystallization of sizeable contingent liabilities arising from the banking sector. In this regard, the HFF represents the main source of risk.

– A disorderly unwinding of capital controls leading to significant capital outflows a sharp depreciation of the ISK and a resurgence of inflation. The main factors that could lead to a positive rating action: – Greater clarity about the evolution capital controls and, in particular the mechanism for releasing offshore krona.

– Enduring monetary and exchange rate stability.

– Further signs of banking sector stabilisation accompanied by continued progress of private sector domestic debt restructuring.

– Continued reduction in public andexternal debt ratios.

KEY ASSUMPTIONS In its debt sensitivity analysis, Fitch assumes a trend real GDP growth rate of 2.5%, GDP deflator of 3.5%, an average primary budget surplus of 3.2% of GDP, nominal effective interest rate of 6% and an annual depreciation of 2% (to capture potential exchange rate pressures resulting from the lifting of capital controls) over 2012-21. Moreover a recapitalization of HFF equivalent to 0.7% of GDP is assumed in 2013. Under these assumptions, public debt/GDP declines from its current level to 69% of GDP in 2021. The debt path is sensitive to growth shocks. Under a growth stress scenario (0.2% potential growth), public debt would remain on a downward trajectory but it would stabilise at a markedly higher level (90% of GDP) by 2019. While Iceland’s debt dynamics appears to be resistant to an interest-rate stress scenario, a sharp deterioration in the exchange rate (possibly associated with a disorderly unwinding of capital controls) would have a more adverse effect.

Similarly, a scenario with no fiscal consolidation (primary deficit of 0.3% of GDP in the medium-term) would reverse the debt downward path: debt would reach 100% of GDP in 2015 and would remain above that level for 2015-21.

Fitch assumes that contingent liabilities arising from the banking sector (mainly through HFF) will be limited. Under a scenario where contingent liabilities arise due to the recapitalisation of HFF and they account for 4% of GDP each year from 2014 to 2016, public debt would still remain on a downward trajectory. However, it would reach 81% of GDP by 2021 (versus 69% under the baseline).

Fitch assumes that capital controls will ultimately be unwound in an orderly manner.

Fitch assumes that the eurozone remains intact and that there is no materialisation of severe tail risks to global financial stability.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

While waiting for a Cyprus bail-out – or a bail-in

Someone will have to take losses as Cypriot banks deleverage and the sovereign debt is brought down. The next big date for Cyprus is the beginning of June when a redemption on a €1.4bn euro bond is due – not a trivial sum in an €18bn economy. It might all be undramatic – but so far the EZ has shown amazing aptitude for tension and brinkmanship

After Pimco was hired to find out how much would be needed to recapitalise the Cypriot banks the first number the Pimcoans aired was €10bn, not a trivial sum in an €18bn economy. Following this shock, Blackrock was asked to review the Pimco methodology, after which Pimco continued its work. Instead of publishing the report as first intended it will be kept confidential until a bailout has been negotiated (or until it is leaked).

The number optimistic Cypriots are hoping for from Pimco is €8bn but that might be somewhat optimistic – €8.8bn might be more realistic. That the report isn’t made public might indicate that Pimco landed on the scary €10bn.

Now, why would 10bn be scary? Because, in this €18bn economy the €10bn adds to the 2.5bn loan already received from the Russians and to the ca €5bn the state will need to fulfil its obligations until it can return to the market. At the end of the third quarter of last year the public debt stood at 82% of GDP. The worst case bailout need of roughly a GDP would pull the debt up to a crippling 140% or so.

The feeling in Cyprus is that €10bn for the banks means that there will a great pressure on the island’s government to privatise in full. There are still plenty of semi state-owned entities, i.e. companies where the state owns 51%. This counts for telecoms, utilities companies and many others. – This makes me think of Iceland after the war and up to the 80s when political power was concentrated around state-owned companies, creating some very cosy relationships but not the most effective use of resources.

In spite of a left-leaning population in Cyprus the unwillingness to privatise doesn’t necessarily stem from ideological aversion but from the envisaged pain from sacking people, adding to the growing number of unemployed people. In a country of only 800.000 this is understandable. Unavoidably, privatisation spells loss of jobs and those in charge know it will hit family and friends. Privatisation in Cyprus will no doubt happen – but it will be painful if it needs to be done in a short span of time at exactly the time austerity is arriving on the shores of Cyprus.

Cyprus clearly has unrealised state-owned assets, which it wants to make money on according to its own plan. The same counts for revenue in sight from gas resources, now in sight off the shores of the island. Cyprus doesn’t want to pledge this revenue against the coming loans. The worse the situation is shown to be the less flexibility there is for the new Cypriot government following presidential election on February 17 and a second round a week later, in case no candidate gets a majority. The strongest candidate is Nicos Anastasiades, a conservative from Angela Merkel’s sister party in Germany. Merkel has already showed up on the island to support Anastasiades.

This time, the Troika won’t be the only lender. Russia has a stake in keeping the island afloat and has alread indicated it wants to add to the bailout packet, through the IMF.

The bailout hinder right now is the persistent rumour of money laundering in the island. Cypriot authorities have answered by pointing at the island’s track record in fulfilling the requirement of the OECD and other international instituations. That hasn’t helped and now, having realise that more is needed, the Cypriot Parliament and ministers have promised that whatever needs to be investigated can be so, however the Troika will want to go about it.

In summer when Cyprus requested a bailout my first impression of the Cypriot situation was that Cyprus will be another Greece with bad news surfacing over months and possibly years. My Cypriot sources strongly reject this theory and are adamant that in spite of being geographical neighbours, Cypriots and Greeks couldn’t be more different.

For a bailout to do the trick two things seem to be essential – to force the banks to shed debt and to find some way of writing down or extending maturity on Cypriot debt. This will have to be done, in order to find a sustainable solution but the question is how fast and how, which ultimately means that someone is going to lose. With no write-down, the bailout won’t be sustainable anymore than it was first and second time around in Greece.

Only recently Germany’s finance minister Wolfgang Schäuble last aired his argument that Cyprus isn’t important enough to save but he seems to be isolated here. The reputational argument is: if the EU can’t bail out one of its smallest brothers how convincing is it that they are able to see a big brother like Spain through its difficulties? The troika will fix a programme and loan for Cyprus. From EU sources it seems likely that Olli Rehn’s view will prevail – no write-down.

The financial argument is that there are no proper private sector investors to drag to the barber’s chair, forcing them to take a haircut. The bank debt hasn’t yet migrated to the state except for the €2.5bn Russian loan. As to the two biggest banks one is 85% owned by the Cypriot state and in the other the shareholders are the general Cypriot public, with the largest shareholder owning 1%. A hair-cut will hit domestic investors and the state.

How might things proceed? The wishful scenario is that after the signing of the MoU, possibly in March, Cyprus will – as it has already started – implent the necessary measures, demanded by the lenders. Well on track, let’s say six months later, it will ask for longer maturities. Russia has already indicated it is willing to extend the maturity of the five year loan 2.5bn loan from end of 2011. This needs to have happened by beginning of March when a €1.4bn is due on a Cyprus euro bond.

This is the undramatic version. Something dramatic might of course upset this smooth forecast. There has been a flurry of guesses today, following an FT article last night, which spelled out options, ia some form of a bail-in – looks like capital controls – that would hinder depositors in moving their money, to be discussed at an EZ meeting of finance ministers in Brussels today. Cypriot ministers ruled this firmly out. The EZ group chairman Jeroen Dijsselbloem refused to answer such a hypothetical question when asked if he would like to keep his money in a Cyprus bank. After the EZ meeting we seem to be back to wishful scenario. Until the unforeseen strikes.

*An earlier Icelog on Cyprus, a link to a recent update on Cyprus on the Prodigal Greek – and another earlier blog on Iceland and Cyprus.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

More on Barclays and Kaupthing Middle East investors

Tonight, BBC’s Panorama shed further light on the investment in Barclays, made by Middle Eastern investors in autumn 2008 – an investment that has some striking similarities with the investment from the same part of the world in Kaupthing in September 2008. At that time, Kaupthing managers proudly announced that a Qatari investor, Sheihk Mohammed bin Khalifa al Thani, had so much faith in the bank that he had bought 5.1% of the bank’s shares.

Only later did it transpire that the faith in Kaupthing wasn’t quite as strong as the statements indicated. Kaupthing lent money to companies connected to the Sheikh and allegedly channeled $50m, an in-advance profit, to a company controlled by the Sheikh. As reported earlier on Icelog the Office of the Special Prosecutor in Iceland has charged ex Kaupthing managers – Sigurdur Einarsson, Hreidar Mar Sigurdsson and Magnus Gudmundsson – and the bank’s second largest shareholder at the time Olafur Olafsson – for alleged misdoings related to this investment. The Sheikh has not been charged in this loan saga.

Interestingly, the Panorama programme indicated that allegedly and as far as it could be gauged from Barclays public documents the Abu Dhabi sovereign investment fund made the investment whereas profit went into an offshore company controlled by Sheikh Mansour bin Zayed al-Nahyan.

An FT article on Qatari debt illustrates Qatar’s toughness in squeezing as much as possible out of every deal and the global power they derive from their financial strength. According to the FT “Qatar is notorious for trying to get something for nothing,” says one observer of the region’s financial institutions. “You have to almost pay them to do the deal.” Indeed an interesting statement in view of the Kaupthing Qatari deal. The Panorama programme indicates this toughness might apply to some of their neighours as well.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Jon Asgeir Johannesson yet again on the FT front page – this time for tax fraud

The Icelandic Supreme Court has sentenced Jon Asgeir Johannesson to one year prison, suspending the sentence for two years for tax evasion. In addition, Johannesson is ordered to pay ISK62m, €371.445. The case is a part of a case that has been running since Baugur’s offices were raided in 2002. In the summer of 2008 he was sentenced to 3 month prison, also suspended, for fraud, in a case that also sprung from the raids in 2002. In its sentencing the Supreme Court reprimanded the Reykjavik County Court for giving Johannesson too much scope to delay the case. The sentence was more lenient, according to the judgement, because the criminal behaviour stems from tax returns in the years 1999-2003. The charges were not brought until 2008.

But this is not the only case that brings Johannesson to court these days. The Office of the Special Prosecutor has charged Johannesson and Glitnir managers for causing Glitnir fraudulent losses, as recounted earlier on Icelog. In another case the Glitnir Winding-up Board is suing Johannesson and eight others – Glitnir managers and board members – for a fraudulent lending of ISK15bn to companies related to Johannesson. In both these cases Johannesson is effectively being charged and sued as a shadow director – as someone who was not legally a director but who acted like one who by putting pressure on managers and board caused these huge losses, stemming from loans issued to companies related to Johannesson and his close business partners.

The Glitnir case is related to a case the WuB tried to bring to a New York court but failed. This case is now being fought in Iceland but the New York exercise did probably help the WuB gather valuable information, which will benefits its case in Reykjavik. Johannesson’s defender claimed in court today that his client had no powers to manipulate the Glitnir management. Johannesson emphasises his innocence in both cases.

Johannesson has lately made some investments in the UK, on behalf of his independently wealthy wife. His investment in Muddy Boots, a very successful fine food start-up, made headlines recently. News of his investment indicated he would be on the board of Muddy Boots. It is unclear if this sentencing will affect these plans but with this sentencing he can’t sit on boards of Icelandic companies in the near future. After the sentencing in 2008 he was forced to step down from the board of some UK companies where he had been a board member.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.