Iceland’s recovery: myths and reality (or sound basics, decent policies, luck and no miracle)

Icelandic authorities ignored warnings before October 2008 on the expanded banking system threatening financial stability but the shock of 90% of the financial system collapsing focused minds. Disciplined by an International Monetary Fund program, Iceland applied classic crisis measures such as write-down of debt and capital controls. But in times of shock economic measures are not enough: Special Prosecutor and a Special Investigative Committee helped to counteract widespread distrust. Perhaps most importantly, Iceland enjoys sound public institutions and entered the crisis with stellar public finances. Pure luck, i.e. low oil prices and a flow of spending-happy tourists, helped. Iceland is a small economy and all in all lessons for bigger countries may be limited except that even in a small economy recovery does not depend on a one-trick wonder.

“The medium-term prospects for the Icelandic economy remain enviable,” the International Monetary Fund, IMF, wrote in its 2007 Article IV Consultation

Concluding Statement, though pointing out there were however things to worry about: the banking system with its foreign operations looked ominous, having grown from one gross domestic product, GDP, in 2003 to ten fold the GDP by 2008. In early October 2008 the enviable medium-term prospect were clouded by an unenviable banking collapse.

All through 2008, as thunderclouds gathered on the horizon, the Central Bank of Iceland, CBI, and the coalition government of social democrats led by the Independence party (conservative) staunchly and with arrogance ignored foreign advice and warnings. Yet, when finally forced to act on October 6 2008, Icelandic authorities did so sensibly by passing an Emergency Act (Act no. 125/2008; see here an overview of legislation related to the restructuring of the banks and here more broadly on economic measures).

Iceland entered an IMF program in November 2008, aimed at restoring confidence and stabilising the economy, in addition to a loan of $2.1bn. In total, assistance from the IMF and several countries amounted to ca. $10bn, roughly the GDP of Iceland that year.

In spite of mostly sensible measures political turmoil and demonstrations forced the “collapse government” from power: it was replaced on February 1 2009 by a left coalition of the Left Green party, led by the social democrats, which won the elections in spring that year. In spite of relentless criticism at the time, both governments progressed in dragging Iceland out of the banking mess.

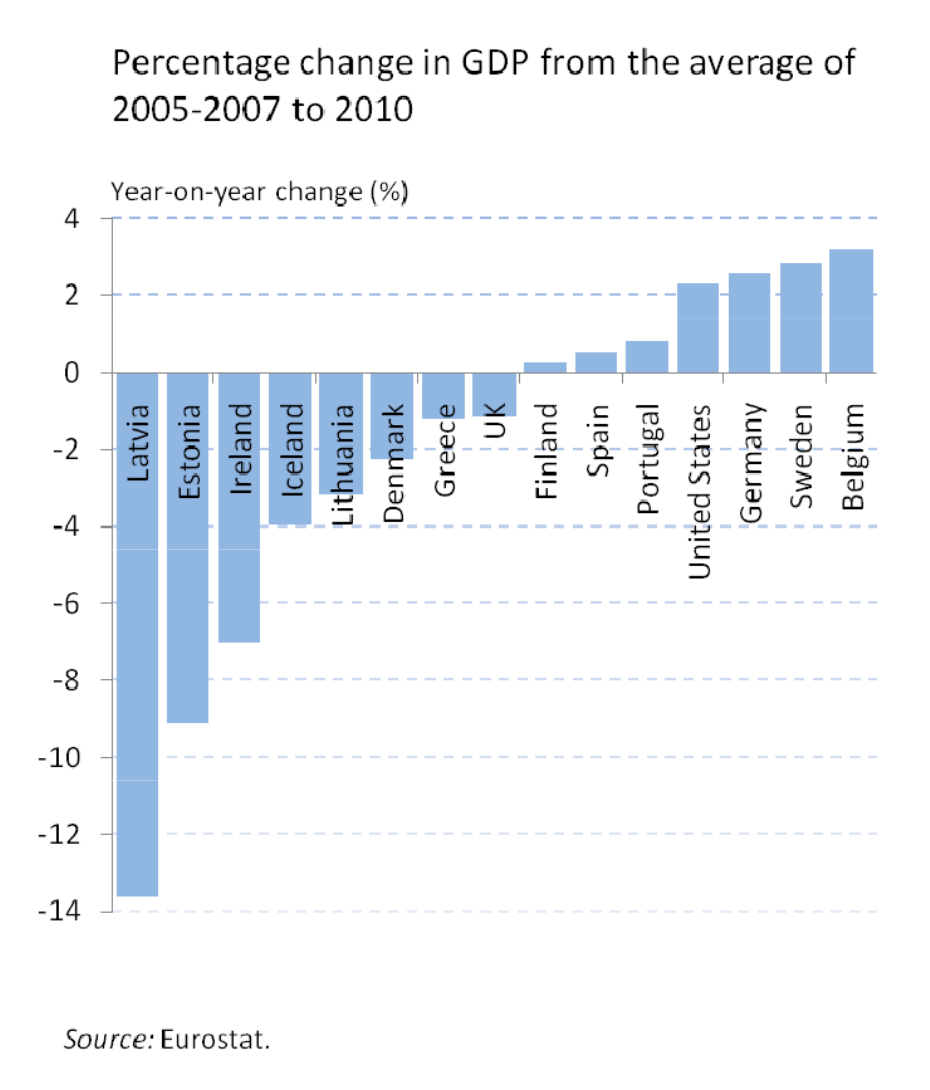

After the GDP contracted by 4% in the first three years the Icelandic economy was already back to growth summer 2011 and is now in its fifth year of economic growth. In 2015, Iceland became the first European country, hit by crisis in 2008-2010, to surpass its pre-crisis peak of economic output.

Iceland is now doing well in economic terms and yet the soul is lagging behind. Trust in the established political parties has collapsed: instead, the Pirate party, which has never been in government, enjoys over 30% following in opinion polls.

Compared to Ireland and Greece, Iceland’s recovery has been speedy, giving rise to questions as to why so quick and could this apparent Icelandic success story be applied elsewhere. Interestingly, much of the focus of that debate is very narrow and in reality not aimed at clarifying the Icelandic recovery but at proving or disproving aspects of austerity, the euro or both.

Unfortunately, much of this debate is misleading because it is based on three persistent myths of the Icelandic recovery: that Iceland avoided austerity, did not save its banks and that the country defaulted. All three statements are wrong: Iceland has not avoided austerity, it did save some banks though not the three largest ones and did not default.

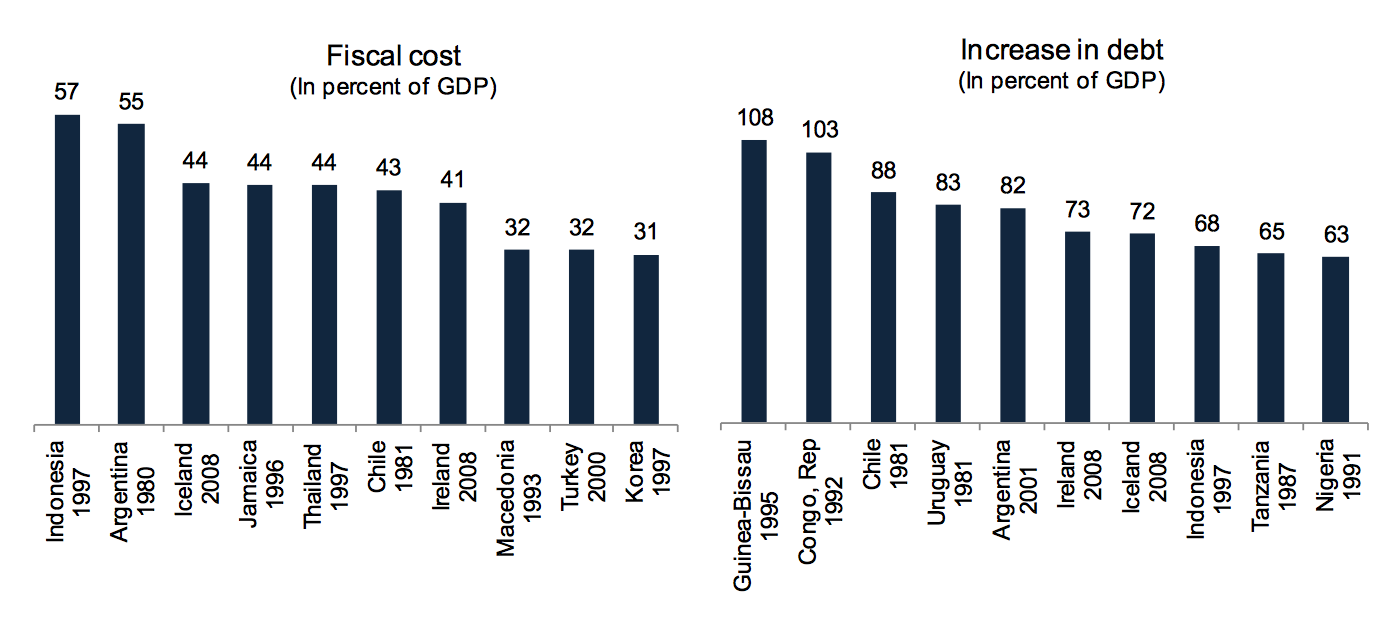

Indeed, the high cost of the Icelandic collapse is often ignored, amounting to 20-25% of GDP. Yet, not as high as feared to begin with: the IMF estimated it could be as much as 40%. The net fiscal cost of supporting and restructuring the banks is, according to the IMF 19.2% of GDP.

Costliest banking crisis since 1970; Luc Laeven and Fabián Valencia.

As to lessons to avoid the kind of shock Iceland suffered nothing can be learnt without a thorough investigation as to what happened, which is why I believe the report, a lesson in itself, by the Special Investigative Commission, SIC, in 2010 was fundamental. Tackling eventual crime, as by setting up the Office of the Special Prosecutor, is important to restore trust. Recovering from a collapse of this magnitude is not only about economic measures and there certainly is no one-trick fix.

On specific issues of the economy it is doubtful that Iceland, a micro economy, can be a lesson to other countries but in general, the lessons are simple: sound public finances and sound public institutions are always essential but especially so in times of crisis.

In general: small economies fall and bounce fast(er than big ones)

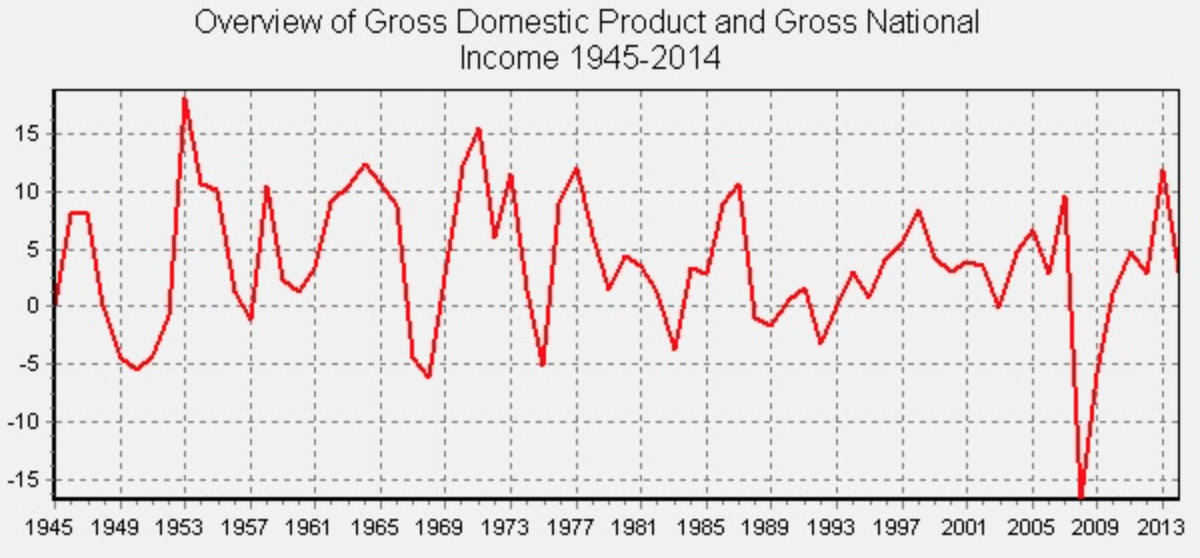

The path of the Icelandic economy over the past fifty years has been a path up mountains and down deep valleys. Admittedly, the banking collapse was a major shock, entirely man-made in a country used to swings according to whims of fishing stocks, the last one being in the last years of the 1990s.

(Statistics, Iceland)

Sound public finances, sound institutions

What matters most in a crisis country? Cleary a myriad of things but in hindsight, if a country is heading for a major crisis make sure the public finances are in a sound state and public authorities and institutions staffed with competent people, working for the general good of society and not special interests – admittedly not a trivial thing.

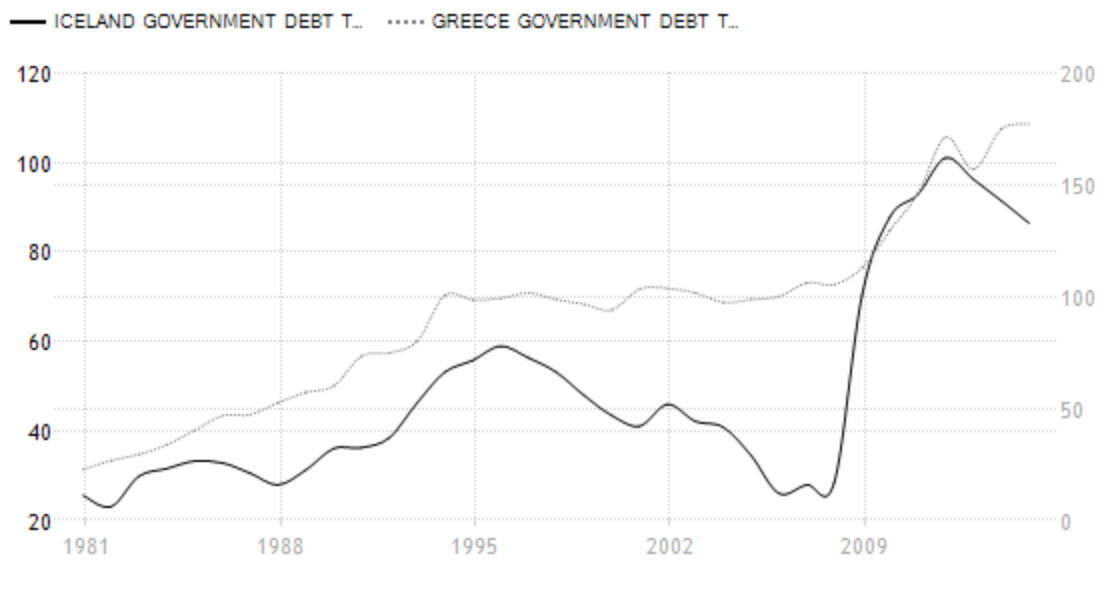

Since 1980 Icelandic sovereign debt to GDP was on average 48.67%, topped at almost 60% around the crisis in late 1990s and had been going down after that. Compare with Greece.

Trading Economics

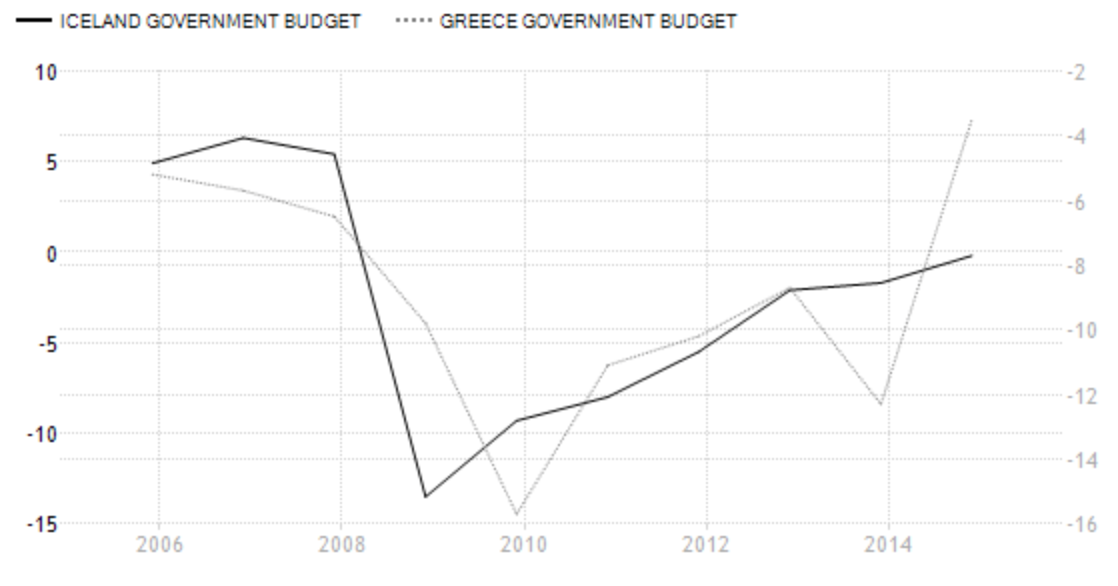

Same with the public budget: there was a surplus of 5-6% in the years up to 2008, against an average of -1.15% of GDP from 1998 to 2014. With a shocking deficit of 13.5% in 2009 it has since steadily improved, pointing to a balanced budget this year and a tiny surplus forecasted for next year. Again, compare with Greece.

Trading Economics

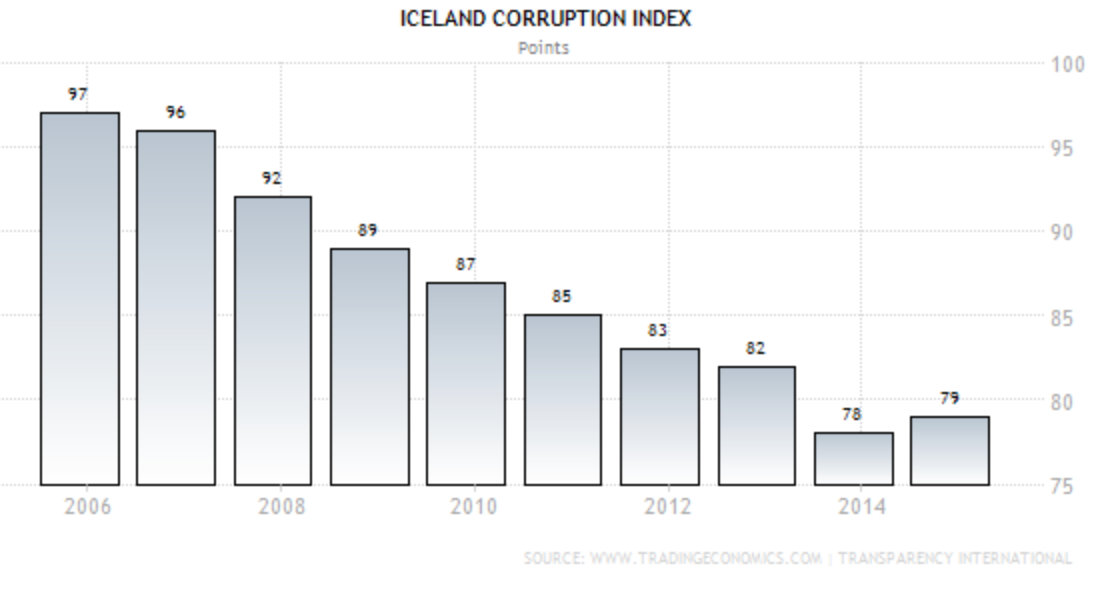

As to institutions, the CBI has been crucial in prodding the necessary recovery policies; much more so after change of board of governors in early 2009. Sound institutions and low corruption is the opposite of Greece, where national statistics were faulty for more than a decade (see my Elstat saga here).

Events in 2008

In early 2007, with sound state finances and fiscal strength the situation in Iceland seemed good. The banks felt invincible after narrowly surviving the mini crisis on 2006 following scrutiny from banks and rating agencies (the most famous paper at the time was by Danske Bank’s Lars Christensen).

Icelanders were keen on convincing the world that everything was fine. The Icelandic Chamber of Commerce hired Frederic Mishkin, then professor at Columbia, and Icelandic economist Tryggvi Þór Herbertsson to write a report, Financial Stability in Iceland, published in May 2006. Although not oblivious to certain risks, such as a weak financial regulator, they were beating the drum for the soundness of the Icelandic economy.

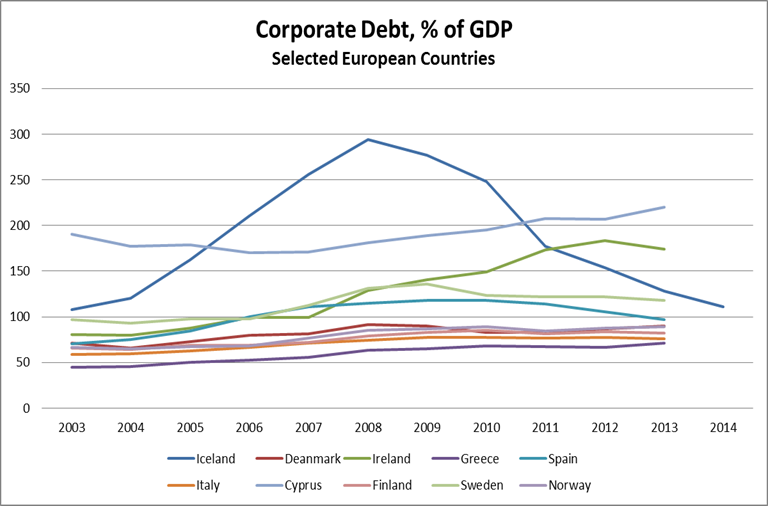

But like in fairy tales there was one major weakness in the economy: a banking system with assets, which by 2008 amounted to ten times the country’s GDP. Among economists it is common knowledge that rapidly growing financial sector leads to deterioration in lending. In Iceland, this was blissfully ignored (and in hindsight, not only in Iceland: Royal Bank of Scotland is an example).

Instead, the banking system was perceived to be the glory of Icelandic policies in a country that had only ever known wealth from the sea. Finance was the new oceans in which to cast nets and there seemed to be plenty to catch.

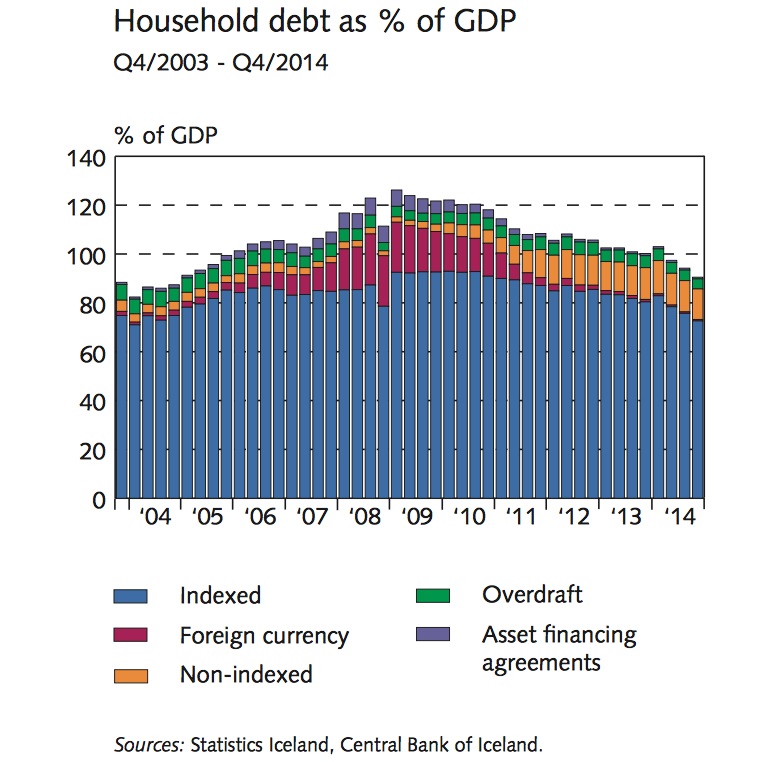

In early 2008 things had however taken a worrying turn: the value of the króna was declining rapidly, posing problems for highly indebted households – 15% of their loans were in foreign currency, i.a. practically all car loans. The country as a whole is dependent on imports and with prices going up, inflation rose, which hit borrowers; consumer-price indexed, CPI, loans (due to chronic inflation for decades) are the most common loans.

Iceland had been flush with foreign currency, mainly from three sources: the Icelandic banks sought funding on international markets; they offered high interest rates accounts abroad – most of these funds came to Iceland or flowed through the banks there (often en route to Luxembourg) – and then there was a hefty carry trade as high interest rates in Iceland attracted short- and long-term investors.

“How safe are your savings?” Channel 4 (very informative to watch) asked when its economic editor Faisal Islam visited Iceland in early March 2008. CBI governor Davíð Oddsson informed him the banks were sound and the state debtless. Helping the banks would not be “too much for the state to swallow (and here Oddsson hesitated) if it wanted to swallow it.” – Yet, timidly the UK Financial Services Authority, FSA, warned savers to pay attention not only to the interest rates but where the deposits were insured the point being that Landsbanki’s Icesave accounts, a UK branch of the Icelandic bank, were insured under the Icelandic insurance scheme.

The 2010 SIC report recounts in detail how Icelandic authorities ignored or refused advise all through 2008, refused to admit the threat of a teetering banking system, blamed it all on hedge funds and soldiered on with no plan.

The first crisis measure: Emergency Act Oct. 6 2008

Facing a collapsing banking system did focus the minds of politicians and key public servants who over the weekend of October 4 to 5 finally realised that the banks were beyond salvation. The Emergency Act, passed on October 6 2008 laid the foundation for splitting up the banks. Not into classic good and bad bank but into domestic and foreign operations, well adapted to alleviating the risk for Iceland due to the foreign operations of the over-extended banks.

The three old banks – Kaupthing, Glitnir and Landsbanki – kept their old names as estates whereas the new banks eventually got new names, first with the adjective “Nýi,” “new,” later respectively called Arion bank, Íslandsbanki and Landsbankinn. Following the split, creditors of the three banks own 87% of Arion and 95% of Íslandsbanki, with the state owning the remaining share. Due to Icesave Landsbanki was a different case, where the state first owned 81.33%, now 97.9%.

In addition to laying the foundation for the new banks, one paragraph of the Emergency Act showed a fundamental foresight:

In dividing the estate of a bankrupt financial undertaking, claims for deposits, pursuant to the Act on on (sic) Deposit Guarantees and an Investor Compensation Scheme, shall have priority as provided for in Article 112, Paragraph 1 of the Act on Bankruptcy etc.

By making deposits a priority claim in the collapsed banks interests of depositors were better secured than had been previously (and normally is elsewhere).

When 90% of a financial system is swept away keeping payment systems functioning is a major challenge. As one participant in these operations later told me the systems were down for no more than ca. five or ten minutes during these fateful days. All main institutions, except of course the three banks, withstood the severe test of unprecedented turmoil, no mean feat.

The coming months and years saw the continuation of these first crisis measures.

It is frequently stated that Iceland, the sovereign, was bankrupted by the collapse or defaulted on its debt. That is not correct though sovereign debt jumped from ca. 30% of GDP in 2008 until it peaked at 101% in 2012.

IMF and international assistance of $10bn

That fateful first weekend of October 2008 it so happened that there were people from the IMF visiting Iceland and they followed the course of events. Already then seeking IMF assistance was discussed but strong political forces, mainly around CBI governor Davíð Oddsson, former prime minister and leader of the Independence party, were vehemently against.

One of the more surreal events of these days was when governor Oddsson announced early morning on October 7 that Russia would lend Iceland €4bn, with maturity of three to four years, the terms 30 to 50 basis points over Libor. According to the CBI statement “Prime Minister Putin has confirmed this decision.” – It has never been clarified who offered the loan or if Oddsson had turned to the Russians but as the Cypriot and Greek government were to find out later this loan was never granted. If Oddsson had hoped that a Russian loan would help Iceland avoid an IMF program that wish did not come true.

On November 17, 2008 the Prime Minister’s Office published an outline of an Icelandic IMF program: Iceland was “facing a banking crisis of extraordinary proportions. The economy is heading for a deep recession, a sharp rise in the fiscal deficit, and a dramatic surge in public sector debt – by about 80%.”

The program’s three main objectives were: 1) restoring confidence in the króna, i.a. by using capital controls; 2) “putting public finances on a sustainable path”; 3) “rebuilding the banking system… and implementing private debt restructuring, while limiting the absorption of banking crisis costs by the public sector.”

An alarming government deficit of 13.5% was now forecasted for 2009 with public debt projected to rise from 29% to 109% of GDP. “The intention is to reduce the structural primary deficit by 2–3 percent annually over the medium-term, with the aim of achieving a small structural primary surplus by 2011 and a structural primary surplus of 3½-4 percent of GDP by 2012.” – This was never going to be austerity-free.

By November 20 2008 IMF funds had been secured, in total $2.1bn with $827m immediately available and the remaining sum paid in instalments of $155m, subject to reviews. The program was scheduled for two years and the loan would be repaid 2012 to 2015.

Earlier in November Iceland had secured loans of $3bn from the other Nordic countries together with Russia and Poland (acknowledging the large Polish community in Iceland). Even the tiny Faroe Islands chipped in with $50m. In addition, governments in the UK, the Netherlands and Germany reimbursed depositors in Icelandic banks, in all ca. $5bn. Thus, Iceland got financial assistance of around $10bn, at the time equivalent of one GDP, to see it through the worst.

In spite of a lingering suspicion against the IMF, both on the political left and right, there was never the defiance à la greque. Both the “collapse coalition” and then the left government swallowed the bitter pill of an IMF program and tried to make the best of it. Many officials have mentioned to me that the discipline of being in a program helped to prioritise and structure the necessary measures.

Recently, an Icelandic civil servant who worked closely with the IMF staff, told me that this relationship had been beneficial on many levels, i.a. had the approach of the IMF staff to problem solving been an inspiration. Here was a country willing to learn.

Part of the answer to why Iceland did so well is that the two governments more or less followed the course set out in he IMF program. This turned into a success saga for Iceland and the IMF. One major reason for success was Iceland’s ownership of the program: politicians and leading civil servants made great effort to reach the goals set in the program. – An aside to the IMF: if you want a successful program find a country like Iceland to carry it out.

Capital controls: a classic but much maligned measure

For those at work on crisis measures at the CBI and the various ministries there was little breathing space these autumn weeks in 2008. No sooner was the Emergency Act in place and the job of establishing the new banks over (in reality it took over a year to finalise) when a new challenge appeared: the rapidly increasing outflow of foreign funds threatened to sink the króna below sea level and empty the foreign currency reserves of the CBI.

On November 28 the CBI announced that following the approval of the IMF, capital flows were now restricted but would be lifted “as soon as circumstances allow.” De facto, Iceland was now exempt from the principle of freedom of capital movement as this applies in the European Economic Area, EEA. The controls were on capital only, not on goods and services, affected businesses but not households.

At the time they were set, the capital controls kept in place foreign-owned ISK650bn, or 44% of Icelandic GDP, mostly harvest from carry trades. Following auctions and other measures these funds had dwindled down to ISK291bn by the end of February 2015, just short of 15% of GDP. However, other funds have grown, i.e. foreign-owned ISK assets in the estates of the failed banks, now ca. ISK500bn or 25% of GDP.

In addition, there is no doubt certain pressure from Icelandic entities, i.e. pension funds, to invest abroad. The Icelandic Pension Funds Association estimates the funds need to invest annually ISK10bn abroad. Greater financial and political stability in Iceland will help to ease the pressure. (Further to the numbers behind the capital controls and plan to ease them, see my blog here).

With capital controls to alleviate pressure politicians in general have the tendency to postpone solving the problems kept at bay by the controls; this has also been the case in Iceland. The left government made various changes to the Foreign Exchange Act but in the end lacked the political stamina to take the first steps towards lifting them. With up-coming elections in spring 2013 it was clear by late 2012 that the government did not have the mandate to embark on such a politically sensitive plan so close to elections.

In spring 2015, after much toing and froing, the coalition of Independence party led by the Progressive party presented a plan to lift the controls. The most drastic steps will be taken this winter, first to bind what remains from the carry trades and second to deal with the estates, where ca. 80% of their foreign-owned ISK assets will be paid as a “stability contribution” to the state. (I have written extensively on the capital controls, see here). The IMF estimates it might take up to eight years to fully lift the controls.

It is notoriously difficult to measure the effects of capital controls. It is however a well-known fact that with time capital controls have a detrimental effect on the economy, as the CBI has incessantly pointed out in its Financial Stability reports.

In its 2012 overview over the Icelandic program the IMF summed up the benefits of controls:

“… as capital controls restricted investment opportunity abroad, both foreign and local holders of offshore króna found it profitable to invest in government bonds, which facilitated the financing of budget deficit and helped avoid a sovereign financing crisis.” – Considering the direct influence of inflation, due to CPI-indexation of household debt, the benefits also count for households.

Again, measuring is difficult but the stability brought by the controls seems to have helped though the plan to lift them came none too soon. Some economists claim the controls were unnecessary and have only done harm. None of their arguments convince me.

Measures for household and companies

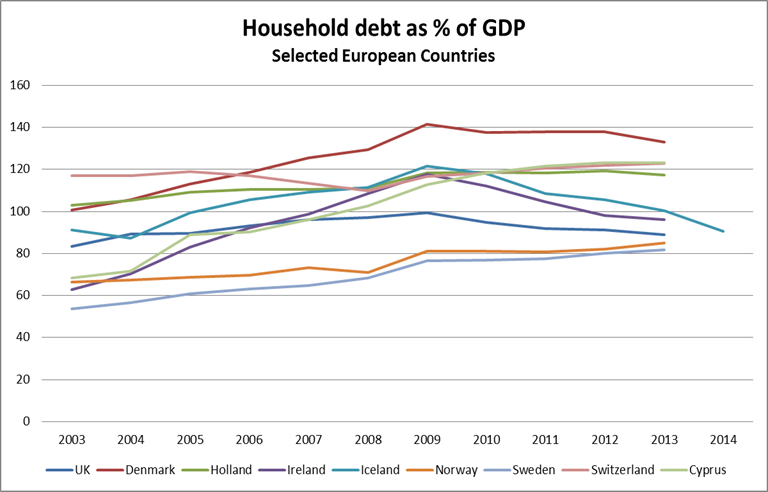

Icelandic households have for decades happily lived beyond their means, i.e. household debt has been high in Iceland. The debt peaked in 2009 but has been going down rapidly since then.

CBI

Already in early 2008, the króna started to depreciate versus other currencies. From October 2007 to October 2008 the changes were dramatic: €1 stood at ISK85 at the beginning of this period but at ISK150 in the end; by October 2009 the €1 stood at ISK185.

Even before the collapse it was clear that households would be badly hit in various ways by the depreciating króna, i.a. due to the CPI-indexation of loans as mentioned above. In addition, banks loaded with foreign currency from the carry trades had for some years been offering foreign currency loans, in reality loans indexed against foreign currencies. With the króna diving instalments shot up for those borrowing in foreign currency; as pointed out earlier, 15% of household debt was in foreign currency.

The left government’s main stated mission was to shield poorer households and defend the welfare system during unavoidable times of austerity following the collapse. In addition, there was also the point that in a contracting economy private spending needed to be strengthened.

The first measure aimed directly at households was in November 2008 when the government announced that people could use private pension funds to pay down debt.

Soon after the banking collapse borrowers with loans in foreign currency turned to the courts to test the validity of these loans. As the courts supported their claims the government stepped in to push the banks to recalculate these loans.

In total, at the end of January 2012 write-downs for households amounted to ISK202bn. For non-financial companies the write-downs totalled ISK1108bn by the end of 2011 (based on numbers from Icelandic Financial Services Association). In general, Icelandic households have been deleveraging rapidly since the crisis.

CBI

Governments in other crisis countries have been reluctant to burden banks with the cost of write-downs and non-performing loans. In Iceland, there was a much greater political willingness to orchestrate write-downs. The fact that foreign creditors owned two of the three banks may also have made it less painful to Icelandic politicians to subject the banks to the unavoidable losses stemming from these measures.

Changes in bankruptcy law

In 2010 the Icelandic Bankruptcy Act was changed. Most importantly, the time of bankruptcy was shortened to two years. The period to take legal action was shortened to six months.

There are exemptions from this in case of big companies and bankruptcy procedures for financial companies are different. However, the changes profited individuals and small companies. In crisis countries such as Greece, Ireland and Spain bankruptcy laws has been a big hurdle in restructuring household finances, only belatedly attended to.

… and then, 21 months later, Iceland was back to growth

It was indicative of the political climate in Iceland that when the minister of finance, trade and economy Steingrímur Sigfússon, leader of the Left Green party, announced in summer 2011 that the economy was now growing again his tone was that of an undertaker. After all, the growth was “only” forecasted to be around 2%, much less than what Iceland had enjoyed earlier. Yet, this was a growth figure most of his European colleagues would have shouted from the rooftops.

Abroad, Sigfússon was applauded for turning the economy around but he enjoyed no such appreciation in Iceland.

As inequality diminished during the first years of the crisis the government could to a certain degree have claimed success (see on austerity below). However, the left government did poorly in managing expectations. Torn by infighting, its political opponents, both in opposition and within the coalition parties never tired of emphasising that no measures were ever enough. That was also the popular mood.

The króna: help or hindrance?

Much of what has been written on the Icelandic recovery has understandably been focused on the króna – if beneficial and/or essential to the recovery or curse – often linked to arguments for or against the EU and the euro.

A Delphic verdict on the króna came from Benedikt Gíslason, member of the capital controls taskforce and adviser to minister of finance Bjarni Benediktsson. In an interview to the Icelandic Viðskiptablaðið in June 2015 Gíslason claimed the króna had had a positive effect on the situation Iceland found itself in. “Even though it (the króna) was the root of the problem it is also a big part of the solution.”

Those who believe in the benefits of own independent currency often claim that Iceland did devalue, as if that had been part of a premeditated strategy. That however was not the case: the króna has been kept floating, depreciating sharply when funds flowed out in 2008. The capital controls slammed the break on, stabilising and slowly strengthening the króna.

Lately, with foreign currency inflows, i.a. from tourism, the króna has further appreciated but not as much as the inflows might indicate: the CBI buys up foreign currency, both to bolster its reserve and to hinder too strong a króna. Thus, it is appropriate to say that the króna float is steered but devaluation, as a practiced in Iceland earlier (up to the 1990s) and elsewhere, has not been a proper crisis tool.

Had Iceland joined the EU in 1995 together with Finland and Sweden, would it have taken up the euro like Finland or stayed outside as Sweden did? There is no answer to this question but had Iceland been in the euro capital controls would have been unnecessary (my take on Icelandic v Greek controls, see here). Would the euro group and the European Central Bank, ECB, have forced Iceland, as Ireland, to save its banks if Iceland had been in the euro zone? Again, another question impossible to answer. After all, tiny Cyprus did a bail-in (see my Cyprus saga here).

On average, fisheries have contributed around 10% to the Icelandic GDP, 11% in 2013 and the industry provided 15-20% of jobs. Fish is a limited resource with many restrictions, meaning that no matter markets or currency fishing more is not an option.

Tourism has now surpassed the fishing industry as a share of GDP. Again, depreciating króna could in theory help here but Iceland is not catering to cheap mass tourism but to a more exclusive kind of tourism where price matters less. Attracting over a million tourists a year is a big chunk for a population of 330.000 but my hunch is that the value of the króna only has a marginal effect, much like on the fishing industry: the country’s capacity to receive tourists is limited.

Currency is a barometer of financial soundness. One of the problems with the króna is simply the underlying economy and the soundness of the governments’ economic policies or lack of it, at any given time. Sound policies have often been lacking in Iceland, the soundness normally not lasting but swinging. Older Icelanders remember full well when the interests of the fishing industry in reality steered the króna, much like the soya bean industry in Argentina.

The króna is no better or worse than the underlying fundamentals of the economy. In addition, in an interconnected world, the ability of a government to steer its currency is greatly limited, interestingly even for a major currency like the British pound. What counts for a micro economy like Iceland is not necessarily applicable for a reserve currency.

Needless to say, the króna did of course have an effect on how Iceland fared after the collapse but judging exactly what that effect has been is not easy and much of what has been written is plainly wrong. (I have earlier written about the right to be wrong about Iceland; more recent example here). In addition, much of what has been written on Iceland and the króna is part of polemics on the EU and the euro and does little to throw light on what happened in Iceland.

Iceland: no bailouts, no austerity?

There have been two remarkably persisting stories told about the Icelandic crisis: 1) it didn’t save its banks and consequently no funds were used on the banks 2) Iceland did not undergo any austerity. – Both these stories are only myths, which have figured widely in the international debate on austerity-or-not, i.a. by Paul Krugman (see also the above examples on the right to be wrong about Iceland) who has widely touted the Icelandic success as an example to follow. Others, like Tyler Cowen, have been more sceptical.

True, Iceland did not save its three largest banks. Not for lack of trying though but simply because that task was too gigantic: the CBI could not possibly be the lender of last resort for a banking system ten times the GDP, spread over many countries.

When Glitnir, the first bank to admit it had run out of funds, turned to the CBI for help on September 29 2008, the CBI offered to take over 75% of the bank and refinance it. It only took a few days to prove that this was an insane plan. The CBI lent €500m to Kaupthing on the day the Alþingi passed the Emergency Act, October 6 2008, half of which was later lost due to inappropriate collaterals. This loan is the only major unexplained collapse story.

The left government later tried to save two smaller banks – a futile exercise, which only caused losses to the state – and did save some building societies. The worrying aspect of these endeavours was the lack of clear policy; it smacked of political manoeuvring and clientilismo and only added to the high cost of the collapse, in international context.

As to austerity, every Icelander has stories to tell about various spending cuts following the shock in October 2008. Public institutions cut salaries by 15-20%, there were cuts in spending on health and education. (Further on cuts see IMF overview 2012).

With the left government focused on the poorer households it wowed to defend benefit spending and interest rebates on mortgages. These contributions are means-tested at a relatively low income-level but helped no doubt fending off widening inequality. Indeed, the Gini coefficients have been falling in Iceland, from 43 in 2007 to 24 in 2012, then against EU average of 30.5. (See here for an overview of the social aspects of the collapse from October 2011, by Stefán Ólafsson).

In addition, it is however worth observing that although inequality in general has not increased, there are indications that inter-generational inequality has increased, as pointed out in the CBI Financial Stability Report nr. 1, 2015: at end of 2013 real estate accounted for 82% of total assets for the 30 to 40 years age group, compared to 65% among the 65 to 70 years old. The younger ones, being more indebted than the older ones are much more vulnerable to external shocks, such as changes in property prices and interest rates. Renters and low-income families with children, again more likely to be young than older people, are still vulnerable groups.

In the years following the crisis the unemployment jumped from 2.4% in 2008 to peak of 7.6% in 2011, now at 4.4%. Even 7.6% is an enviable number in European perspective – the EU-28 unemployment was 9.5% in July 2015 and 10.9.% for the euro zone – but alarming for Iceland that has enjoyed more or less full employment and high labour market participation.

Many Icelanders felt pushed to seek work abroad, mostly in Norway, either only one spouse or the whole family. Poles, who had sought work in Iceland, moved back home. Both these trends helped mitigate cost of unemployment benefits.

Austerity was not the only crisis tool in Iceland but the country did not escape it. And as elsewhere, some have lamented that the crisis was not used better to implement structural changes, i.a. to increase competition.

The pure luck: low oil prices, tourism and mackerel

Iceland is entirely dependent on oil for transport and the fishing fleet is a large consumer of oil. Iceland is also dependent on imports, much of which reflect the price of oil, as does the cost of transport to and from the country. It is pure luck that oil prices have been low the years following the collapse, manna from heaven for Iceland.

The increase in tourism has been crucial after the crisis. Tourism certainly is a blessing but the jobs created are notoriously low-paying jobs. As anyone who has travelled around in Iceland can attest to, much of these jobs are filled not by Icelanders but by foreigners.

Until 2008, mackerel had never been caught in any substantial amount in Icelandic fishing waters: the catch was 4.200 ton in 2006, 152.000 ton in 2012. Iceland risked a new fishing war by unilaterally setting its mackerel quota. Fishing stocks are notoriously difficult to predict and the fact that the mackerel migrated north during these difficult years certainly was a stroke of luck.

The non-measureables: Special Prosecutor and the SIC report

As Icelanders caught their breath after the events around October 6 2008 the country was rife with speculations as to what had indeed happened and who was to blame. There were those who blamed it all squarely on foreigners, especially the British. But the collapse also changed the perception of Icelanders of corruption and this perception has lingered in spite of action taken against individuals. This seems to be changing, yet slowly.

When Vilhjálmur Bjarnason, then lecturer at the University of Iceland, now MP for the Independence party, said following the collape that around thirty men (yes, all males) had caused the collapse, many nodded.

Everyone roughly knew who they were: senior bankers, the main shareholders of the banks and the largest holding companies, all prominent during the boom years until the bitter end in October 2008. Many of these thirty have now been charged, some are already in prison and other fighting their case in courtrooms.

Alþingi responded swiftly to these speculations, by passing two Acts in December: setting up an Office of a Special Prosecutor, OSP and a Special Investigative Committee, SIC to clarify the collapse of the financial sector. These two Acts proved important steps for clearing the air and setting the records straight.

After a bumpy start – no one applied for the position of a Special Prosecutor – Ólafur Hauksson a sheriff from Reykjavík’s neighbouring town Akranes was appointed in January 2009. Out of 147 cases in the process of being investigated at the beginning of 2015, 43 are related to the collapse (the OSP now deals with all serious cases of financial fraud).

The Supreme Court has ruled in seven cases related to the collapse and sentenced in all but one case; Kaupthing’s second largest shareholder and three of the bank’s senior managers are now in prison after a ruling in the so-called al Thani case. – Gallup Iceland regularly measures trust in institutions. Since the OSP was included, in 2010, it has regularly come out on top as the institution enjoying the highest trust.

As to the SIC its report, published on 12 April 2010, counts a 2600 page print version, which sold out the day it was published, with additional material online; an exemplary work in its thoroughness and clarity.

The trio who oversaw the work – its chairman then Supreme Court judge Páll Hreinsson (now judge at the EFTA Court), Alþingi’s Ombudsman Tryggvi Gunnarsson and Sigríður Benediktsdóttir then lecturer in economics at Yale (now head of Financial Stability at the CBI) – presented a convincing saga: politicians had not understood the implication of the fast growing banking sector and its expansion abroad, regulators were too weak and incompetent, the CBI not alert enough and the banks egged on by over-ambitious managers and large shareholders who in some cases committed criminality.

How have these two undertakings – the OSP and the SIC – contributed to the Icelandic recovery? I fully accept that the effect, as I interpret it, is subjective but as said earlier: recovery after such a major shock is not only about direct economic measures.

Setting up the OSP has strengthened the sense that the law is blind to position and circumstances; no alleged crime is too complicated to investigate, be it a bank-robbery with a crowbar or excel documents from within a bank. The OSP calmed the minds of a nation highly suspicious of bankers, banks and their owners.

The benefit of the SIC report is i.a. that neither politicians nor special interests can hi-jack the collapse saga and shape it according to their interests. The report most importantly eradicated the myth that foreigners were only to blame – that Iceland had been under siege or attack from abroad – but squarely placed the reasons for the collapse inside the country.

The SIC had a wide access to documents, also from the banks. The report lists loans to the largest shareholders and other major borrowers. This clarified who and how these people profited from the banks, listed companies they owned together with thousands of Icelandic shareholders.

The SIC’s thorough and well-documented saga may have focused the political energy on sensible action rather than wasting it on the blame game. Interestingly, this effect is no less relevant as time goes by. To my mind, the atmosphere both in Ireland and Greece, two countries with no documented overview of what happened and why, testifies to this.

In addition, the report diligently focuses on specific lessons to be learnt by the various institutions affected. Time will show how well the lessons were learnt but at least heads of some of these institutions took the time and effort, with their staff, to study the outcome.

A country rife with distrust and suspicion is not a good place to be and not a good place for business. Both these undertakings cleared the air in Iceland – immensely important for a recovery after such a shock, which though in its essence an economic shock is in reality a profound social shock as well.

I mentioned sound institutions above. Their effect is not easily measureable but certainly well functioning key institutions such as ministries, National Statistics and the CBI have all been important for the recovery.

Lessons?

In its April 2012 Ex Post Evaluation of Exceptional Access Under the 2008 Stand-by Arrangement the IMF came up with four key lessons from Iceland’s recovery:

(i) strong ownership of the program … (ii) the social impact can be eased in the face of fiscal consolidation following a severe crisis by cutting expenditures without compromising welfare benefits, while introducing a more progressive tax system and improving efficiency; (iii) bank restructuring approach allowing creditors to take upside gains but also bear part of the initial costs helped limit the absorption of private sector losses by public sector; and (iv) after all other policy options are exhausted, capital controls could be used on a temporary basis in crisis cases such as Iceland, where capital controls have helped prevent disorderly deleveraging and stabilize the economy.

The above understandably refers to the economic recovery but recovering from a shock like the Icelandic one – or as in Ireland, Greece and Cyprus – is not only about finding the best economic measures, though obviously important. It is also about understanding and coming to terms with what happened.

As mentioned above, I firmly believe that apart from classic measures regarding insolvent banks and debt, both sovereign and private, the need to clarify what happened, as was done by the SIC and to investigate alleged criminality, as done by the OSP, is of crucial importance – something that Ireland (with a late and rambling parliamentary investigation), Greece, Cyprus and Spain could ponder on. All of this in addition to sound institutions and sound public finances before a crisis.

The soul lagging behind

In the olden days it was said that by traveling as fast as one did in a horse-drawn carriage the soul, unable to travel as fast, lagged behind (and became prone to melancholia). Same with a nation’s mood following an economic depression: the soul lags behind. After growth returns and employment increases it takes time until the national mood moves into the good times shown by statistics.

Iceland is a case in point. Although the country returned to growth, with falling unemployment, in 2011 the debate was much focused on various measures to ease the pain of households and nothing seemed ever enough.

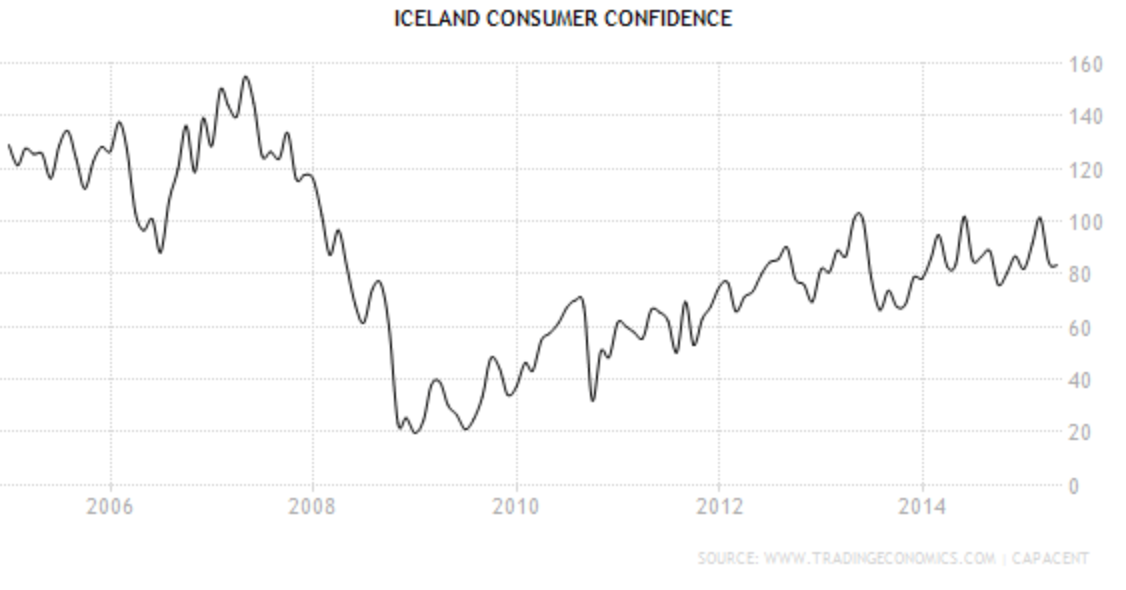

The Gallup Expectations monitor turned upwards in late 2009, after a steep fall from its peak in late 2007, and has been rising slowly since. Yet it is now only at the 2004 level; the Icelandic inclination to spending has been sig-sawing upwards. – Here two graphs, which indicate the mood:

With plan in place to lift capital controls, the last obvious sign of the 2008 collapse will be out of the way. Implementation will take some years; a steady and secure execution this coming winter will hopefully lift spirits in the business community.

Living intimately with forces of nature, volcanoes and migrating fish stocks, and now tourists, as fickle as the fish in the ocean, Icelanders have a certain sangue-froid in times of uncertainty. Actions by the three governments since the collapse have at times been rambling but on the whole they have sustained recovery.

A sign of the lagging soul is that growth has not brought back trust in politics. Politicians score low: the most popular party now enjoying ca. 35% in opinion polls, almost seven years after the collapse and four years since turning to growth, is the Pirate party, which has never been in government.

Recovery (probably) secured – but not the future

As pointed out in a recent OECD report on Iceland the prospect is good and progress made on many fronts, the latest being the plan to lift capital controls: “inflation has come down, external imbalances have narrowed, public debt is falling, full employment has been restored and fewer families are facing financial distress. “

However, the worrying aspect is that in addition to fisheries partly based on cheap foreign labour the new big sector, tourism, is the same. Notoriously low productivity – a chronic Icelandic ill – will not be improved by low-paid foreign labour. Well-educated and skilled Icelanders are moving abroad whereas foreigners moving to the country have fewer skills. Worryingly, there is little political focus on this.

As the OECD points out “unemployment amongst university graduates is rising, suggesting mismatch. As such, and despite the economic recovery, Iceland remains in transition away from a largely resource-dependent development model, but a new growth model that also draws on the strong human capital stock in Iceland has yet to emerge.”

Iceland does not have time to rest on its recovery laurels. Moving out of the shadow of the crisis the country is now faced with the old but familiar problems of navigating a tiny economy in the rough Atlantic Ocean.

This post is cross-posted with A Fistful of Euros.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Iceland: growth and sound(er) economy ≠ political popularity

A short aside to those who think it’s only the economy, stupid – well, at least this is not the case in Iceland. If this is the case elsewhere, winning against parties overseeing economic growth is far from impossible: interesting now that the British Labour party is searching its feet with Jeremy Corbyn.

Early in October 2008, 90% of the Icelandic financial system collapsed, leaving the nation shocked and bewildered. The government coalition at the time – social democrats led by the Independence party (c) – took some sensible measures and i.a. called in the International Monetary Fund, IMF. Yet, the coalition could not withstand the turmoil, in society and politics, and by February 2009 it had resigned, replaced by a left coalition with the Left Green party, never before in government, led by the social democrats.

By summer 2011, less than three years after this national cataclysm, Iceland was back to 2% growth. Nothing like the growth before the collapse but still growth, enviable in a European context.

The unemployment had spiked by that time, never went above the forecasted 10%. Still, shocking in Icelandic context though again benign compared to other crisis-hit European countries.

At the time of the next election, in spring 2013, the economy was doing well,unemployment clearly falling, household debt falling and the two most important industries, fishing and tourism, doing well. Yet, the government that turned the economy around lost (yes, for many reasons such as vicious infighting and, what simply seemed a lack of will to live… another saga).

Now, things are going even better, finally with a plan to lift the capital controls (execution remains to be seen) and many even talk of/fear a brewing boom in Iceland.

And what do the voters say? Aren’t they happily embracing the government that has brought the economy onwards and upwards? No, actually not. Nor is there any nostalgia for the old left government, these two parties are doing badly as are the two parties in government.

Instead, the voters have cast their love, at least in polls, on the Pirate party, which has never been in government and only just made it above the 5% hurdle, needed to get elected, in the 2013 election. In an early September poll, the Pirates scored an incredible 35.9%.

In the olden days it was said that when a man traveled by a carriage the soul would lag behind as it could not keep up with the speed of the fast-moving carriage. This seems to apply to the national mood in Iceland: the economy is growing, even close to booming but the soul of the Icelanders has far from caught up – unless the Icelandic soul is simply yearning for an elusive something else not caught by the politics on offer from the other parties.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Corbyn’s European context and the challenge to turn popularity into power

After barely making it on to the ballot paper, Jeremy Corbyn beats even Tony Blair’s 1994 record and gathers 59.5% support for leadership. Anti-establishment parties have been sprouting in Europe but the fairly unique aspect of Corbyn’s success is his rise within an old and established party. Much is made of his (self-proclaimed) socialism. Yet, it is more likely that Corbyn gathered support not because he is a socialist but in spite of being one. Getting elected as a leader was the easy bit; leading will be the truly tricky part unless Corbyn proves to be a political virtuoso – and the European left will be watching.

For his opponents, it seems easiest to attack Jeremy Corbyn for being a socialist as the majority of voters are clearly without the slightest leaning in that direction. However, if personality matters as much as politics that tactic is bound to fail to scare voters away from him. To my mind, Corbyn was not voted for his socialism but in spite of it – in times of personality politics his ideas seem as much part of him as his beard compared to what I call patch-work politics stitched together from focus-group material and political advisers.*

Given the earlier success of Tony Blair and another charismatic politician Bill Clinton it became received wisdom that no political career could possibly be successful without their kind of flashy charisma. Also here, Corbyn disproves so far the accepted wisdom: he is serious at rallies and often grumpy in the media but what he says fits him like his beard.

Compared to recent political stars in Europe Corbyn is the only outsider in an old party to challenge the party elite and be voted as a leader. The last outsider achieving was Margret Thatcher elected as Tory leader in 1975. As Corbyn, she was not expected to last long. Famously, Thatcher and later Blair proved themselves to be eminent at capturing the nation’s mood. Briefly, Corbyn has done the same but a lasting success will only arise if he can use his popularity to create a Labour power base. The European left will be watching.

What matters is not left or right but the outsider-image

In times of slow growth and contraction, there has been no lack of new European parties of discontent and anger. The Italian Movimento Cinque Stelle, M5S rose on the fame of its leader Beppe Grillo, accountant and comedian, a year older than Corbyn. M5S has more or less imploded: Grillo was good at being angry in public but useless at organising a party machine.

The Greek Syriza, born on the old-style Greek left, shot to fame with its energetic leader Alexis Tsipras. Unable to fulfil his promises, he now fights an election and might be losing the surge that brought him to power in February. New political movements in Spain – the left Podemos, the activist “idignados” and Ciudadanos on the right – will no doubt influence the coming elections there. Again, unclear if these parties can turn popularity into power.

In the stable North long-simmering far-right anti-establishment sentiments have grown stronger in Finland, Sweden and Denmark. In Iceland, the Pirate party got 5% in the election in spring 2013, just enough to get into Parliament but has been scoring over 30% in polls since early this year.

Compared to once upon a time voters are now not only less wedded to one party but also travel back and forth between left and right. Considering the volatility of voters it seems to make more sense to see these new-comers as an expression of discontent with old parties rather than necessarily as a sign of swing to the left or right in the respective countries. It is more a question of who appeals strongest to the party-unfaithfuls and disillusioned at any given time.

This also seems to be the context for Corbyn – there is no indication that British voters are swinging to the left. After all, Ukip did well in last elections. Given the chance, voters turn against the political establishment and embrace something new.

The irony is that the new is now a 66 years old leftie backbencher, in Parliament since 1983, echoing the socialism of his youth, generally unknown to others than his Islington voters, whom he has served by mostly being in opposition to the Labour party leadership at any given time.

The lack of left response to 2008

The singular aspect of the Western crisis that surfaced in 2007 was the fact that it was created by banks and their, for the society at large, unhealthy and anti-social activities in the years up to 2007.

Strangely enough, Labour let itself be ensnared by the opposition’s narrative during the 2015 spring elections that it had mismanaged the economy during its years in power, 1997 to 2010. Fettered by this narrative Labour kept quiet about the fact that Labour and the Tories, united in its admiration for an apparently booming finance industry, shared the laissez-faire view of scaled-back regulation. During the boom, neither party worried about weak regulators and underfunded and little-loved Serious Fraud Office and Inland Revenue.

The underlying public anger surfaced in the Occupy movements and grass-root activities, largely ignored by the old and established parties both in Britain and elsewhere. In the 2010 elections Liberal democrats rose on the 2008 anger but were unable to turn that surge of popularity into lasting power.

Yet, political elites might well have found a convincing response to 2008. Politicians on the right could argue for the capitalism of creation. It is not necessarily in the capitalistic spirit to let a sector, that in theory should be serving and nurturing the economy, tie up so much capital in its own money spinning activities that went so disastrously wrong, causing calamity for the rest of society.

More surprisingly, European established left parties have mostly not responded to the crisis in any meaningful way and Labour is one of them. No leading Labour politicians seems i.a. interested in a coherent investigation of the UK banks’ activities before and after 2007. One reason why I notice the underlying anger it that hardly a week goes by without hearing someone mention the Icelandic example of investigating financial fraud related to the 2008 collapse.

This silent space has been Corbyn’s to occupy, rhetorically asking if teachers, nurses etc. caused the financial crisis and weaving into it his anti-austerity stance. Quite remarkably, seven years on from 2008 and with the economy growing again, this old anger and frustration is still a fertile ground as Corbyn has now discovered and demonstrated.

From a private election machine to a party machine

According to Corbyn, he had an army of sixteen thousand volunteers working for him. Quite something in an era of shrinking membership in established political parties. It is difficult to believe that this machine was put together in only three months – more likely, supportive trade unions provided him with all it took to build a smooth-running operation.

If Corbyn the Labour leader translates his success into convincing policies backed by the Labour party he and his party will unavoidably become a leading light on the European left as New Labour once was. However, his challenges are formidable. He must i.a. enthuse the Labour party machine as he did with his own private election machine.

Corbyn must also grapple with anchoring his messages into policies that gather support within in the party. A received wisdom in politics is that no one goes anywhere without a supportive media. Given that Corbyn uses every opportunity to kick the media, possibly perceiving it as part of the establishment and to strengthen his outsider-image, it will be interesting to see how he fares versus the media: if he will change course and court it or if he continues his adversarial angry attitude.

When new Labour rose to power in 1997 they did not only lead Britain but set the tone for the whole of the European left. New Labour is no longer new but old and stale and the top-trend post has been empty for a while. The most recent contender was Syriza. With popularity and power Tsipris shot to fame among the European left who flocked to Greece to meet Syriza’s leading lights. I.a. Italian prime minister Matteo Renzi avidly courted Tsipras but, as others, quickly seemed to realise there was little to fetch.

The European left, lately poor of success stories, will be following Corbyn closely though his anti-EU stance will make some Europeans wary. As seen in many European countries over the last few years, anger and frustration may gather popularity; but unless sustained by action and comprehensive policies it has little staying power and wanders on to the next eye-catching political promise-bidder.

*See my earlier blog on Corbyn and patch-work politicians.

This blog is cross-posted with A Fistful of Euros.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Personality politics and the New Labour legacy: Corbyn v patchwork politicians

Jeremy Corbyn has come into the political summer like a red storm rising. No political neophyte and not charismatic in the flashy way (but well, neither are his three opponents) he sweeps up support with his slightly dour, dry reasoning embracing the word “socialism.” His message, like it or loath, has that one thing the other three lack: a coherent narrative that fits him like his beard. – His political assets stand all the more out compared to what his three contenders offer: a homeopathic blend of old New Labour and patchwork politics.

Who would have thought in early summer that electing a Labour leader would reveal a political yearning for something new by a surging support for the oldest candidate? With three wholly presentable political thoroughbreds the candidate from the “loony left” was intended as a red-hot chilli to enliven a bland concoction. But chilli is a tricky ingredient and can easily dominate a dish.

Over the last few years voters in some European countries have flocked around challengers to old party-political structures: there is the Cinque Stelle in Italy, Podemos in Spain, Syriza in Greece, the Pirate Party in Iceland and to a certain degree UKIP – new, or relatively new parties that suddenly capture the voters’ political imagination.

Contrary to these new political splashes it is interesting that Jeremy Corbyn, voted into Parliament in 1983, as were Tony Blair and Gordon Brown, is neither new in politics nor aspiring to lead a new party. Only rarely does an old hand challenging the party’s ruling elite gather the votes needed to get elected as a leader. Yes, there is the effect of Labour’s new voting rules but this does not explain the Corbyn-mania.

Two political phenomena – Tony Blair’s surge in the election 1997, which lasted until tainted by the Iraqi invasion and Nick Clegg’s unexpected popularity in 2010 – can both partly be explained by the fact that the two were political newcomers. But Corbyn is no political newcomer and neither his politics nor his rhetoric is new.

Adapted to our times his words echo the sixties and seventies when Corbyn was young and a great part of his supporters not even born. Corbyn’s newness is however something that has slowly been seeping out of politics for the last two decades: coherent conviction and a sense of mission – i.e. vision embedded in a political narrative.

Typically of the politicians of their generation Andy Burnham, Yvette Cooper and Liz Kendall are efficient, presentable and no doubt capable. But their message lacks coherence; they have no political narrative.

This lack of narrative is partly Labour’s problem but Corbyn has filled the gaping gap with his own narrative, rooted in his political story whereas his three contenders present a patchwork of headlines assembled from pollsters and focus groups with the help of political advisers. Compared to Corbyn’s red cloak, so eminently his own, the three struggle to carry their patchwork cloaks convincingly.

But why has it come to this sad state of patchwork politics?

Vision can’t be out of political fashion – politics IS vision

New Labour did not invent this adage that vision is dead, long live politics. But the Labour party reinvented and owned by Tony Blair, Peter Mandelson and Alastair Campbell certainly made this their over-arching political idea. Following scandals and the disintegration of the Tory government politics was a dirty word. The New Labour message was nothing as dirty as politics and vision but all about doing the right thing and managing well.

Ever since Labour has told voters that politics is about finding better solutions to manage the economy, the NHS, education and everything else. Oh, so wrong. Politics is not like running a company and the state is not like a company. If so, politicians like Andy Burnham, Liz Kendall and Yvette Cooper would be all the political rage. But they clearly are not.

Worshipping the managerial approach is the essence of the New Labour legacy. Since New Labour was so successful the New Labour vision-less managerial-style politics is still being remixed and reheated by the Burnham-Cooper-Kendall generation that grew up flush with its success. The three candidates are the latest blend, by now wholly diluted – a homeopathic solution of the original New Labour ideas.

But in times of Occupy and anger over rising inequality Labour voters are saying “thanks, but no thank you” to the weak blend the managerial no-vision. They want something new and potent. Against this background Corbyn rises and shines. The irony is that the new is now an elderly and battered socialist with a political soul.

Political language reeking of death and the making of patchwork politics

Under normal circumstances politicians like Burnham, Cooper and Kendall would not be compared to Corbyn but simply to other politicians more or less similar to themselves: thoroughly media-trained, only rarely at loss for an answer because every possible and impossible question has been thrown at them by media-coaches behind closed doors hours on end.

All three have Oxbridge credentials, Corbyn doesn’t. They entered professional politics as advisers soon after university and though young have lived and breathed politics and media training.

Large doses of undigested media training creates a political language reeking of death – death, because no living normal person speaks a language where the simple words “yes” and “no” have largely been banished. Where answers are long enough to make everyone forget the question that the politician doesn’t want to give a straight answer to. Where quirky words are never used but mostly only sanitised words in sentences with vacuous meaning. And no wit please, we are serious politicians (except Boris Johnson).

Corbyn certainly has a touch of media training about him but at least it hasn’t beaten the soul and spirit out of him, as it seems to have done with his contenders. Possibly because they were younger when they were subjected to the training, now seemingly permeating their grey matter.

In addition to the institutionalised media training there is the institutionalised content-building. An expert who participated in policy discussions to help a young politician (none of the three) formulate political ideas told me that whenever the participants dwelled on a topic the adviser orchestrating the whole séance stopped the discussion and told the participants to stick to the headlines. Ultimately an utterly frustrating and uninteresting experience, my source said.

This is how patchwork politics are made – no wonder politicians struggle to give it a convincing tone.

Politics in the times of personality politics

Labour’s loss in spring has i.a. been blamed on Ed Miliband’s leftism. However, in the age of personality politics maybe Labour voters sensed in Miliband the same as in the three of his generation who now offer to replace him: that he was too bland, too unconvincing because he had lost his political soul and offered only patchwork politics.

Corbyn’s supporters have not necessarily studied his thoughts on People’s Quantitative Easing and other issues but they clearly embrace him as a politician they would like to see lead the Labour party and eventually the country.

Those fearing a Corbyn leadership have tried various ways to undermine him: there are the allegedly dubious people like Hamas terrorists and Holocaust deniers he has engaged with during his many years in politics. Is it wise that Corbyn the socialist should replace a candidate thought to be too far to the left? I’ve heard it whispered he might even be posh, a cardinal sin in British politics. And so on.

None of this, however, is likely to drive his supporters away. In times of personality politics – when many voters choose leaders more for who the politician is and the combination of personality and politics matters more than single issues – any such criticism will shake the supporters no more than a splash of water on a goose.

How Corbyn the unruly whip-denier will fare as a leader is another matter. But what the Corbyn-mania shows is that yes, people are interested in politics, vision and narrative matter; patchwork politics dressed up in a dead language fail to engage with the political enthusiasm out there. – The shortcomings of patchwork politicians are all too apparent when they share the stage with a politician whose politics fits his personality like his grey beard.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Greek politics and poisonous statistics – an on-going saga

Why the Troika and the EU member states find it so difficult to trust Greece

The word “trust” has been mentioned time and again in reports on the tortuous negotiations on Greece. One reason is the persistent deceit in reporting on debt and deficit statistics, including lying about an off market swap with Goldman Sachs: not a one-off deceit but a political interference through concerted action among several public institutions for more then ten years.

As late as in the July 12 Euro Summit statement “safeguarding of the full legal independence of ELSTAT” was stated as a required measure. Worryingly, Andreas Georgiou president of ELSTAT from 2010, the man who set the statistics straight, and some of his staff, have been hounded by political forces, also Syriza. Further, a Greek parliamentary investigation aims at showing that foreigners are to blame for the odious debt, which should not be paid while there is no effort to clarify a decade of falsifying statistics.

In Iceland there were also voices blaming its collapse on foreigners but the report of the Special Investigation Committee silenced these voices. – As long as powerful parts of the Greek political class are unwilling to admit to past failures it might prove difficult to solve its results: the excessive debt and deficit.

“This is all the fault of foreigners!” In Iceland, this was a common first reaction among some politicians and political forces following the collapse of the three largest Icelandic banks in October 2008. Allegedly, foreign powers were jealous or even scared of the success of the Icelandic banks abroad or aimed at taking over Icelandic energy sources. In April 2010 the publication of a report by the Special Investigation Committee, SIC, effectively silenced these voices. It documented that the causes were domestic: failed policies, lax financial supervision, fawning faith in the fast-growing banking system and thoroughly reckless, and at times criminal, banking.

As the crisis struck, Iceland’s public debt was about 30% of GDP and budget surplus. Though reluctant to seek assistance from the International Monetary Fund, IMF, the Icelandic government did so in the weeks following the collapse. An IMF crisis loan of $2.1bn eased the adjustment from boom to bust. Already by the summer of 2011 Iceland was back to growth and by August 2011 it completed the IMF programme, executed by a left government in power from early 2009 until spring 2013. Good implementation and Iceland’s ownership of the programme explains the success. For Ireland it was the same: it entered the crisis with strong public finances and ended a harsh Troika programme late 2013; its growth in 2014 was 4.8%.

For Greece it was a different story: high budget deficit and high public debt were chronic. From 1995 to 2014 it had an average budget deficit of -7%. Already in 1996, government debt was above 100% of GDP, hovering there until the debt started climbing worryingly in the period 2008 to 2009 – far from the prescribed Maastricht euro criteria of budget deficit not exceeding 3% and public debt no higher than 60% of GDP. Both Greek figures had however one striking exception: they dived miraculously low, below their less glorious averages in time for joining the euro. Yet, only the deficit number ever went below the required Maastricht criteria, which enabled Greece to join the euro in 2001.

Greece had an extra problem not found in Iceland, Ireland or any other crisis-hit EEA countries: in addition to dismal public finances for decades there is the even more horrifying saga of deliberate hiding and falsifying economic realities by misreporting Excessive Deficit Procedure, EDP and hide debt and deficit with off market swaps.*

This is not a saga of just fiddling the figures once to get into the euro but a deceit stretching over more than ten years involving not only the Greek statistical authorities but the Greek Ministry of Finance, MoF, the Greek Accounting Office, GAO and other important institutions involved in the compilation of EDP deficit and debt statistics – in short, the whole political power base of Greece’s public economy.

Already in 2002 Eurostat discovered that the debt and deficit dip around the euro entry was no miracle but manipulation: Greek authorities simply reported wrong numbers. In 2004, Eurostat’s Report on the revision of the Greek government deficit and debt figures showed that this had been on-going between 1997 to 2003. Consequently, the Greek statistical authorities, the then National Statistical Service of Greece, NSSG (from which ELSTAT was created in mid-2010) were forced to revise its data for the years 2000 to 2003 upward, above the criteria set for Greece’s entry in the Eurozone. These issues were unique to Greece: “Revisions in statistics, and in particular in government deficit data, are not unusual… However, the recent revision of the Greek budgetary data is exceptional.”

The Eurostat 2004 report was followed by intense and unprecedented scrutiny with Eurostat using all its power to control and make sure the Greek stats were correct. Yet, NSSG did not learn its lessons, or rather, the political interference was relentless.

In autumn 2009 the ECOFIN Council requested a new report, this time from the EU Commission, EC, due to “renewed problems in the Greek fiscal statistics” after the “reliability of Greek government deficit and debt statistics (has) been the subject of continuous and unique attention for several years.”

The EC report on Greek Government Deficit and Debt Statistics, published in January 2010 showed that Greek numbers on debt and deficit were still wrong: deficit forecasts changed drastically from the March to the September reporting more than once and once the real statistics were available the numbers were still higher. Again, such a revision was rare in EU member states “but have taken place for Greece on several occasions.”

As earlier, the reason for the faulty data was methodological shortcomings, not only at the NSSG but also at the GAO and the MoF responsible for providing data to NSSG and, even more grave, political interference and “deliberate misreporting,” where the NSSG, GAO, MoF and other institutions involved in the reporting, all played their part.

The Goldman Sachs, GS, off market swap story was one chapter in the faulty data saga. In 2008, when Eurostat made enquiries in all member states on off market swaps, Greek authorities informed Eurostat promptly that the Greek state had engaged in nothing of the sort. This 2008 statement turned out to be a blatant lie when Eurostat investigated the matter, as shown in a Eurostat report in November 2010. The swap story is a parallel to the Greek data deceit in the sense that it was not a single event but a deceit running for years, involving several Greek authorities.

Needless to say, fiddling the numbers did not eradicate the debt and deficit problem. The EC report was published as Greece was losing access to markets. Negotiations on a bailout were complicated by unreliable information on Greek public finances. On May 2, 2010, as the first Greek Memorandum of Understanding was signed, with a €110bn loan – €80bn from European institutions and €30bn from the IMF – it was clear that the crucial figures of debt and deficit might still go up.

Following these major failures at the NSSG its head had resigned in 2009. At the GAO and the MoF ministers, vice ministers and general secretaries changed with the new Papandreou government but the ranks below remained unchanged, as did the mentality. With changes in the statistics law in summer 2010 ELSTAT replaced NSSG. A new board was put in place and also a new head: Andreas Georgiou, earlier at the IMF, returned home to take over at ELSTAT. This ended the battle to produce correct statistics: since August 2010, neither Eurostat nor other European authorities have questioned Greek national statistics.

It was however the beginning of an on-going horror story for Georgiou and some of his staff who have been hounded since ELSTAT began reporting correct statistics in accordance with European standards: three times, competent judiciary officials have recommended to have the criminal case launched against them put to file, i.e. to drop the case. Only recently, a council of appeals court judges have let go of charges against the three for having caused the state a loss of €171bn, which would have meant a prison sentence for life. However, charges against Georgiou for violation of duty are still being upheld; should he be found guilty he will not be able to hold a public post again.

There are now two committees, set up by the Greek parliament, investigating the past. One is the Parliamentary Truth about the Debt Committee. Set up in April 2015, with members chosen by the Syriza president of the Greek parliament Zoe Konstantopoulou, it concluded in its preliminary report, presented June 17, that Greece neither can nor should pay its debt to the Troika because that debt is “is illegal, illegitimate, and odious.” The other, a Parliamentary Investigative Committee made up of members of parliament and normally referred to as the Investigative Committee about the Memoranda, is scrutinising how Greece got into the two Memoranda of Understanding with international partners, in 2010 and 2012, in the context of adjustment programs. – Both committees have repeated the claims against Georgiou and the two ELSTAT managers.

In spite of over a decade long saga of false statistics and political interference there has been no attempt so far to set up an independent committee to tell the whole Greek debt saga, from the 1990s to the present day, manipulated statistics, deceitful swaps, political interference, warts and all.

2004: the first Greek crisis … of unreliable statistics

The first Greek crisis did not attract much attention although it was indirectly a crisis of deficit and debt – it was a crisis caused by faulty statistics, unearthed by Eurostat already in 2002. After going through the deficit and debt figures reported by Greece the 2004 Eurostat’s Report on the revision of the Greek government deficit and debt figures rejected figures put forward by the NSSG in March 2004. After revision the numbers for the previous years looked drastically different – the budget deficit, which should have been within 3%, moved shockingly:

| 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | ||

| DEFICIT | % GDP | % GDP | % GDP | % of GDP | |

| March 2004 | -2.0 | -1.4 | -1.4 | -1.7 | |

| September2004 | -4.1 | -3.7 | -3.7 | -4.6 | |

| DEBT | |||||

| March 2004 | 106.1 | 106.6 | 104.6 | 102.6 | |

| September 2004 | |||||

| 114.0 | 114.7 | 112.5 | 109.9 | ||

Report on the revision of the Greek government deficit and debt figures

The institutions responsible for reporting on the debt and deficit figures were NSSG, the MoF through the GAO as well as MoF’s Single Payment Authority and Bank of Greece. Specifically, NSSG and the MoF were responsible for the deficit reporting; the MoF was fully responsible for the debt figures.

The Eurostat drew various lessons from the first Greek crisis. Legislative changes were made to eradicate the earlier problems – not an entirely successful exercise as could be seen when the same problems re-surfaced. But the most important result of the 2004 crisis was a set of statistical principles known as the European Statistics Code of Practice, adopted in February 2005, revised in September 2011, following the next Greek crisis of statistical data. Unfortunately, NSSG drew no such lessons.

2009: the second Greek crisis … of unreliable statistics

Following the 2004 report Eurostat had NSSG in what can best be described as a wholly exceptional and intensive occupational therapy: from the ten EDP notifications 2005 to 2009 Eurostat had reservations to five of them, far more than any other country received. No country but Greece got “methodological visits” from Eurostat. The Greek notifications, which passed, did so only because Eurostat had corrected them during the notification period, always increasing the deficit from the numbers reported by Greek authorities.

But in spite of Eurostat’s efforts the pupil was unwilling to learn and in 2009 there was a second crisis of statistics: things had not improved as was bluntly stated in a 30-page report on Greek Government Deficit and Debt Statistics from the EC in January 2010. In addition: what had been going on at Greek authorities had no parallel in any other EU country.

This second crisis of Greek statistics in 2009 was in the first instance not set off by a real figure but by the dramatic revisions of the deficit forecast for 2009. As in 2004, this new crisis led to major revisions of earlier forecast: the April forecast was revised twice in October. What happened between spring and October was that George Papandreou and the PASOK ousted New Democracy and prime minister Kostas Karamanlis from power; the new government was now beating drums over much worse state of affairs than earlier data and forecast showed.

After first reporting on October 2 2009 there came another set of numbers from NSSG on October 21, revising earlier reported deficit for 2008 from 5% of GDP to 7.7% – and the forecasted deficit ratio for 2009 of 3.7% was revised to 12.5% (as explained in footnote, numbers for current year are a forecast, whereas numbers for earlier years should be actual data).

And this was not all: in early 2010, Eurostat was still not convinced about the actual EDP data from the years 2005 to 2008. The earlier 2009 deficit forecast of 12.5% had risen to an actual deficit of 13.6% by April 2010 to finally land on 15.4% in late 2010.

The EC report detected common features with events in 2004 and 2009: a change of government – in March 2004, Kostas Karamanlis and New Democracy came to power, ending eleven years of PASOK rule and as mentioned above George Papandreou and PASOK won back power in October 2009.

In both cases “substantial revisions took place revealing a practice of widespread misreporting, in an environment in which checks and balances appear absent, information opaque and distorted, and institutions weak and poorly coordinated. The frequent missions conducted by Eurostat in the interval between these episodes, the high number of methodological visits, the numerous reservations to the notifications of the Greek authorities, on top of the non-compliance with Eurostat recommendations despite assurances to the contrary, provide additional evidence that the problems are only partly of a methodological nature and would largely lie beyond the statistical sphere.

In other words, the problem was not statistics but politics. As politics is well outside its remit, Eurostat could not get to the core of the problem: “Though eventually an overall level of completion was achieved, given that Eurostat is restricted to statistical matters in its work the measures foreseen in the action plan were mainly of a methodological nature, and did not address the issues of institutional settings, accountability, responsibility and political interference.”

The political interference could i.a. be seen from the fact that reservations expressed by Eurostat between 2005 and 2008 on specific budgetary issues, which had then been clarified and corrected, resurfaced in 2009, i.e. earlier corrections were reverted and were now once more wrong.

Good faith versus fraud