Wow Air – uncertainty and unanswered questions

Wow Air, the bold newish privately owned air company on the Icelandic aviation market had planned to be done by now with a bond offering, organised by Pareto Securities, Norway. Closing the offering has been postponed, indicating the bond market is sitting on its hands. The news over the last two weeks has been of a flurry of meetings with no outcome. A presentation on Pareto’s website indicated a weak financial position, which makes the attempt to sell bonds rather unconvincing – and the planned IPO in 18 months more a wishful than a realistic aim.

Tourism is now the largest contributor to balance of payment in Iceland. At the same time, tourism is a major risk factor in the Icelandic economy. Part of that risk is related to aviation – two air companies dominate the aviation market, Icelandair and Wow Air. The news of Wow’s shaky bond offering has rattled the Icelandic króna and the stock market.

Wow Air is privately owned but is now clearly in major financial difficulties. The Icelandic media seems tongue-tied, plenty of rumours but little clarity. One thing seems certain: the bond offering that Pareto Securities launched in August did not seem to be going as hoped.

After silence and then upbeat statements from Wow many questions remain unanswered. Wow has now promised a statement today, Tuesday 18 September.

The much announced bond offer

Over the years, news as to what Wow would do has been a bit here and there. Last year, Skúli Mogensen said to Bloomberg the airline might be sold within the next two years. Finding other shareholders has also been in the air. Now, he aims at an IPO in 18 months. The losses last year were ISK2.4bn, that is around €19m or $22m.

In the meantime, Wow needs to stay in the air. The bond offering now was supposed to give a financial boost of around ISK12bn, €94m or $110m, but half that would be a minimum. After the offering opened the conditions were changed, making the bonds convertible. And the minimum proved elusive. The Icelandic banks and pension funds were courted and apparently put under serious pressure, as there were fears of reputational damage and a nose-diving króna.

Part of the problem is that equity is next to none, something that Wow’s owner nonchalantly mentioned in an interview with the Icelandic Morgunblaðiðin spring. In addition to losses last year and this year, with rising oil prices. Wow does not own any airplanes, which makes it difficult to find any tangible collateral.

In an interview yesterday with the Financial TimesMogensen did not mention the bond offering, only that Wow Air was aiming to raise $200m to $300m in an IPO within 18 months. Those who have studied Wow’s available financial information scratch their head – it is hard to see anything that indicates a turn-around except for Wow’s own very optimistic forecast.

From Oz to Wow

With his predilection for short and sassy company names, Skúli Mogensen had his second coming in the Icelandic business community as the owner of Wow Air in 2012. The first one was in the 1990s as one of the founders of the Icelandic dotcom sputnik Oz. Oz crashed but the experience spawned many other IT companies in the following years as Oz founders and staff kept going elsewhere.

Mogensen however left Iceland and ran Oz Communications in Canada, selling it in 2008 to Nokia. Since it was a private deal little information is available. However, it seems that in spite of rapid and bold, some might say hubristic, expansion the company has been under-financed from the beginning, according to an Icelog source. In may ways, the Wow saga is similar in audacity to the Icelandic banks expansion after 2000.

One of the unanswered questions regards Wow’s debt to Isavia, the state-owned company that runs Keflavík Airport. Morgunblaðið claims Wow’s debt to Isavia is ISK2bn; the number I’ve heard is ISK1bn. If it’s the case that Wow has been allowed to run up a debt to Isavia or has secured more favourable terms than its competitors that is a serious issue. Sadly, that will remind Icelanders of how certain large shareholders in the collapsed banks were allowed to bank on wholly unsustainable terms.

Low-cost carriers are feeling the strain. The business model of offering stop-over in Iceland is also being tested. All of this is at play in the Wow cliff-hanger saga.

*According to Wow Air statement at 3pm Icelandic time, the bond offering has now been closed. Wow Air issuing €60m, €50m of which have already been sold:

*** WOW air – New Bond Issue – Book is closed ***

Tenor…………………3yrs

Issue Size……………EUR 60mm

Coupon………………3m Euribor +9% (Euribor floor at zero) + warrants

Update: Recently, Icelandair made a bid to buy Wow Air. The offer was dependent on due diligence ending this week, in time for Icelandair shareholder meeting on Thursday. According to unconfirmed Icelog sources, the state of affairs at Wow Air is not looking very promising, making it less likely that the sale will go through. Were that to happen, Wow Air would go into receivership. Today, the Icelandic Stock Exchange stopped trade in Icelandair shares, on demand of the FME, the Icelandic financial regulator.

Update 29 November, 9:30: Icelandair has just announced that it’s not going ahead with buying Wow Air, as it had announced, due diligence pending, November 5. Wow CEO Skúli Mogensen recently announced there were other possible buyers. I doubt they will materialise, more likely this is the end of Wow…

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

The unsolved case of Landsbanki in dirty-deals Luxembourg / 10 years on

The Icelandic SIC report and court cases in Iceland have made it abundantly clear that most of the questionable, and in some cases criminal, deals in the Icelandic banks were executed in their Luxembourg subsidiaries. All this is well known to authorities in Luxembourg who have kindly assisted Icelandic counterparts in obtaining evidence. One story, the Landsbanki Luxembourg equity release loans, still raises many questions, which Luxemburg authorities do their best to ignore in spite of a promised investigation in 2013. Some of these questions relate to the activities of the bank’s liquidator, ranging from consumer protection, the bank’s investment in the bank’s own bonds on behalf of clients and if the bank set up offshore companies for clients without their consent.

The Landsbanki Luxembourg equity release loans were issued to clients in France and Spain. Indeed, all these loans were issued to clients outside of Luxembourg. One intriguing fact emerged during the French trial in Paris last year against Landsbanki Luxembourg and nine of its executives and advisors: the French clients got the bank’s loan documents in English, the non-French clients got theirs in French.*

Landsbanki Iceland went into administration October 7 2008. The next day, Landsbanki Luxembourg was placed into moratorium; liquidation proceedings started 12 December. Over the years, Icelog has raised various issues regarding the Landsbanki Luxembourg equity release loans, mostly sold to elderly people (see here). These issues firstly relate to how the bank handled these loans, both the marketing and the investments involved and secondly, how the liquidator Yvette Hamilius, has handled the Landsbanki Luxembourg estate and the many complaints raised by the equity release clients.

A liquidator is an independent agent with great authority to investigate. There is abundant material in Iceland, both from the 2010 Report of the Special Investigative Commission, SIC and Icelandic court cases where almost thirty bankers and others close to the banks have been sentenced to prison. These cases have invariably shown that the most dubious deals were done in the banks’ Luxembourg operations.

Already by June 2015, liquidators of the estates of the three large Icelandic banks were ending their work, handing remaining assets over to creditors. In the, in comparison, tiny estate of Landsbanki Luxembourg there is no end in sight due to various legal proceedings. Yet, its arguably largest problem, the so-called Avens bond, was solved already in 2011. At the time, Már Guðmundsson governor of the Icelandic Central Bank paid tribute to the help received from amongst others Hamiliusfor “considerable efforts in leading this issue to a successful conclusion.”

The Landsbanki Luxembourg equity release clients have another story to tell, both in terms of their contacts with the liquidator and Luxembourg authorities. In May 2012, these clients, who to begin with had each and everyone been struggling individually, had formed an action group and aired their complaints in a press release, questioning Luxembourg’s moral standing and Hamilius’ procedures.

The following day, the group got an unexpected answer: Luxembourg State Prosecutor Robert Biever issued a press release. As I mentioned at the time, it was jaw-droppingly remarkable that a State Prosecutor saw it as his remit to address a press release directed at the liquidator of a private company in a case the Prosecutor had not investigated. According to Biever, Hamilius had offered the borrowers “an extremely favourable settlement” but “a small number of borrowers,” unwilling to pay, was behind the action.

In 2013 Luxembourg Justice Minister promised an investigation into the Landsbanki products that was already taking “great strides.” So far, no news.

The Landsbanki Luxembourg equity release scheme: high risk, rambling investments

In theory, the magic of equity release loans is that by investing around 75% of the loan the dividend will pay off the loan in due course. I have seen calculations of some of the Landsbanki equity release loans that make it doubtful that even with decent investments, the needed level of dividend could have been reached – the cost was simply too high.

If something seems too good to be true it generally is. However, this offer came not from a dingy backstreet firm but from a bank regulated and supervised in Luxembourg, a country proud to be the financial centre of Europe. And Landsbanki was not the only bank offering these loans, which interestingly have long ago been banned or greatly limited in other countries. In the UK, equity release loans wrecked havoc and created misery some decades ago, leading to a ban on putting up the borrower’s home as collateral.

Having scrutinised the investments made for some of the Landsbanki Luxembourg clients the first striking thing is an absolutely staggering foreign currency risk, also related to the Icelandic króna. Underlying bonds on the foreign entities such as Rabobank and European Investment Bank were nominated in Icelandic króna (see here on Rabobank ISK bond issue Jan. 2008), in addition to the bonds of Kaupthing and Landsbanki, the largest and second largest Icelandic banks at the time.

Currencies were bought and sold, again a strategy that will have generated fees for the bank but was of dubious use to the clients.

The second thing to notice is the rudderless investment strategy. To begin with the money was in term deposits, i.e. held for a fixed amount of time, which would generate slightly higher interest rates than non-term deposits. Then shares and bonds were bought but there was no apparent strategy except buying and selling, again generating fees for the bank.

The equity release clients were normally not keen on risk but the investments were partially high risk. The 2007 and 2008 losses on some accounts I have looked have ranged from 10% to 12%. These were certainly testing years in terms of investment but amid apparently confused investing there was indeed one clear pattern.

One clear investment pattern: investing in Landsbanki and Kaupthing bonds

Having analysed statements of four clients there is a recurring pattern, also confirmed by other clients and a source with close knowledge of the bank’s investments: in 2008 (and earlier) Landsbanki Luxembourg invariably bought Landsbanki bonds as an investment for clients, thus turning the bank’s lending into its own finance vehicle. In addition, it also bought Kaupthing bonds. The 2010 SIC report cites examples of how the banks cooperated to mitigate risk for each other.

It is not just in hindsight that buying Landsbanki and Kaupthing bonds as equity release investment was a doomed strategy. Both banks had sky-high risk as shown by their credit default swap, CDS. The CDS are sort of thermometer for banks indicating their health, i.e. how the market estimates their default risk.

The CDS spread for both banks had for years been well below 100 points but started to rise ominously in 2007 as the risk of their default was perceived to rise. At the beginning of 2008, the CDS spread for Landsbanki was around 150 points and 300 points for Kaupthing. By summer, Kaupthing’s CDS spread was at staggering 1000 points, then falling to 800 points. Landsbanki topped close to 700 points. The unsustainably high CDS spread for these two banks indicated that the market had little faith in their survival. With these spreads, the banks had little chance of seeking funds from institutional investors (SIC Report, p.19-20).

The red lights were blinking and yet, Landsbanki Luxembourg staff kept on steadily buying Landsbanki and Kaupthing bonds on behalf of clients who were clearly risk-averse investors.

Equity release investment in some details

To give an idea of the investments Landsbanki Luxembourg made for equity release borrowers, here is some examples of investment (not a complete overview) for one client, Client A:

Loan of €2.1m in January 2008; the loan was split in two, each half converted into Swiss francs and Japanese yens. The first investment, €1.4m, two thirds of the loan,was in LLIF Balanced Fund (in Landsbanki Luxembourg loan documents the term used is Landsbanki Invest. Balanced Fund 1 Cap but in later overviews from the liquidator it is called LLIF Balanced Fund, a fund named in Landsbanki’s Financial Statements 2007 as one of the bank’s investment funds).

Already in February 2008 Landsbanki Luxembourg bought Kaupthing bond for this client for €96.000. End of April 2008 €155.000 was invested in Landsbanki bond, days before €796.000 of the LLIF Balanced Fund investment was sold. Late May and end of August Landsbanki bonds were bought, in both cases for around €99.000. In early September 2008 Landsbanki invested $185.000 in Kaupthing bonds for this client. The next day, the bank sold €520.000 in LLIF Balanced Fund.

Landsbanki’s investments were focused on the financial sector that in 2008 was showing disastrous results. For client A the bank bought bonds in Nykredit, Rabobank, IBRD and EIB, apparently all denominated in Icelandic króna. In addition, there were shares in Hennes & Maurits, and a Swedish company selling food supplement.

A similar pattern can be seen for the other clients: funds were to begin with consistently invested in LLIF Balanced Fund but later sold in favour of Kaupthing and Landsbanki bonds. Although investment funds set up by the Icelandic banks were later shown to contain shares in many of the ill-fated holding companies owned by the banks’ largest shareholders – also the banks’ largest borrowers – a balanced fund should have been seen as a safer investment than bonds of banks with sky-high CDS spreads.

MiFID and the Landsbanki Luxembourg equity release loans

Landsbanki certainly did not invent equity release loans. These loans have been around for decades. Much like foreign currency, FX, loans, a topic extensively covered by Icelog, they have brought misery to many families, in this case mostly elderly people. FX lending has greatly diminished in Europe, also because banks have been losing in court against FX borrowers for breaking laws on consumer protection.

There might actually be a case for considering the equity release loans as FX loans since the loans, taken in euros, were on a regular basis converted into other currencies, as mentioned above. – This is, so far, an unexplored angle of these cases that Luxembourg authorities have refused to consider.

Another legal aspect is that the first investments were normally done before the loans had been registered with a notary, as is legally required in France.

The European MiFID, Markets in Financial Instruments Directive was implemented in Luxembourg and elsewhere in the EU in 2007. The purpose was to increase investor protection and competition in financial markets.

Consequently, Landsbanki Luxembourg was, as other banks in the EU, operating under these rules in 2007. It is safe to say, that the bank was far below the standard expected by the MiFID in informing its clients on the risk of equity release loans.

The following paragraph was attached to Landsbanki Luxembourg statements: “In the event of discrepancies or queries, please contact us within 30 days as stipulated in our “General Terms and Conditions.”– However, the bank almost routinely sent notices of trades after the thirty days had passed.

It is unclear if the liquidator has paid any attention to these issues but from the communication Hamilius has had with the equity release clients there is nothing to indicate that she has investigated Landsbanki operations compliance with the MiFID. MiFID compliance is even more important given that courts have been turning against equity release lenders in Spain due to lack of consumer protection – and that banks have been losing in courts all over Europe in FX lending cases.

Clients offshorised without their knowledge

The “Panama Papers” revealed that Landsbanki was one of the largest clients of law firm Mossack Fonseca; it was Landsbanki’s go-to firm for setting up offshore companies. Kaupthing, no less diligent in offshoring clients, had its own offshore providers so the leak revealed little regarding Kaupthing’s offshore operations. The prime minister of Iceland Sigmundur Davíð Gunnlaugsson, who together with his wife owned a Mossack Fonseca offshore company, became the main story of the leak and resigned less than 48 hours after the international exposure.

In September 2008, a Landsbanki Luxembourg client got an email from the bank with documents related to setting up a Panama company, X. The client was asked to fill in the documents, one of them Power of Attorney for the bank and return them to the bank. The client had never asked for this service and neither signed nor sent anything back.

In May 2009, this client got a letter from Hamilius, informing him that the agreement with company X was being terminated since Landsbanki was in liquidation. The client was asked to sign a waiver and a transfer of funds. Attached was an invoice from Mossack Fonseca of $830 for the client to pay. When the client contacted the liquidator’s office in Luxembourg he was told he should not be in possession of these documents and they should either be returned or destroyed. Needless to say, the client kept the documents.

Company X is in the Offshoreleak database, shown as being owned by Landsbanki and four unnamed holders of bearer shares. – Widely used in offshore companies, bearer shares are a common way of hiding beneficial ownership. Though not a proof of money laundering, the Financial Action Task Force, FATF, considers bearer shares to be one of the characteristics of money laundering.

This shows that Landbanki Luxembourg set up a Panama company in the name of this client although the client did not sign any of the necessary documents needed to set it up. Also, that the liquidator’s office knew of this. (This account is based on the September 2009 email from Landsbanki Luxembourg to the client and a statement from the client).

Other clients I have heard from were offered offshore companies but refused. The story of company X only came out because of the information mistakenly sent from the liquidator to the client.

Landsbanki Luxembourg clients now wonder if companies were indeed set up in their names, if their funds were sent there and if so, what became of these funds. This has led them to attempt legal action in Luxembourg against the liquidator. Only the liquidator will know if it was a common practice in Landsbank Luxembourg to set up offshore companies without clients’ consent, if money were moved there and if so, what happened to these funds.

The curious role of a certain Philomène Ruberto

Invariably, the equity release loans in France and Spain were not sold directly by Landsbanki Luxembourg but through agents. This is another parallel to FX lending characterised by this pattern. According to the Austrian Central Bank this practice increases the FX borrowing risk as agents are paid for each loan and have no incentive to inform the client properly of the risks involved.

One of the agents operating in France was a French lady, Philomène Ruberto. In 2011, well after the collapse of Landsbanki, the Landsbanki Luxembourg was putting great pressure on the equity release borrowers to repay the loans. At this time, Ruberto contacted some of the clients in France. Claiming she was herself a victim of the bank, she offered to help the clients repay their loans by brokering a loan through her own offshore company linked to a Swiss bank, Falcon Private Bank, now one of several banks caught up in the Malaysian 1MDB fraud.

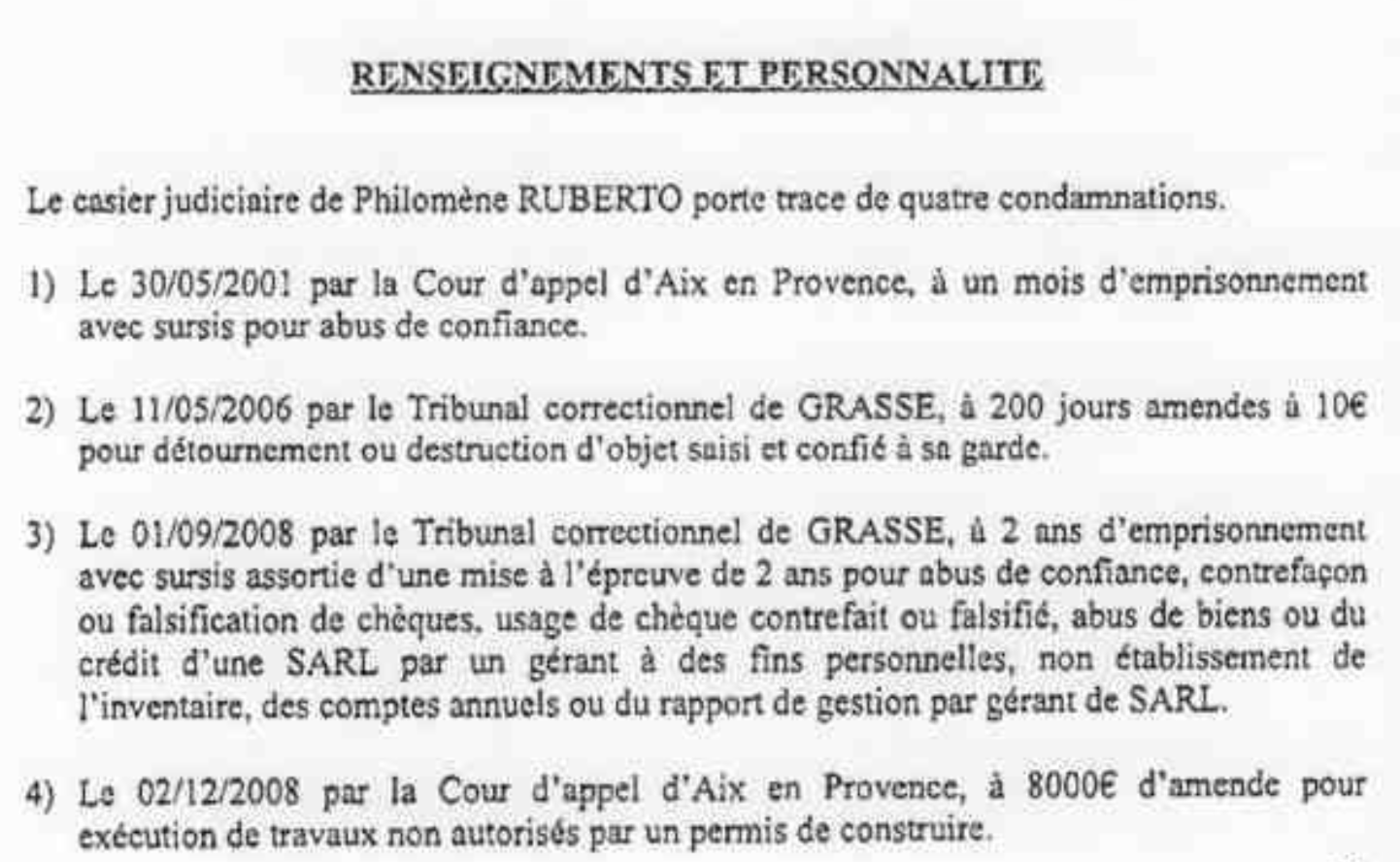

Some clients accepted the offer but that whole operation ended in court, where the clients accused Ruberto of fraud and breach of trust. In a civil case judgement at the Cour d’appel d’Aix en Provence in spring 2013, the judge listed a series of Ruberto’s earlier offenses, committed before and during the time she acted as an agent for Landsbanki:

This case was sent on a prosecutor. In a penal case in autumn 2014 Ruberto was sentenced by Tribunal Correctionnel de Grasse to 36 months imprisonment, a fine of €15,000 in addition to the around €190,000 she was ordered to pay the civil parties. According to the 2104 judgement Ruberto was, at the time of that case, detained for other causes, indicating that she has been a serial financial fraud offender since 2001.

But Ruberto’s relationship with Landsbanki Luxembourg prior to the bank’s collapse has a further intriguing dimension: GD Invest, a company owned by Ruberto and frequently figuring in documents related to her services, was indeed also one of Landsbanki Luxembourg largest borrowers. The SIC Report (p.196) lists Ruberto’s company, GD Invest, as one of the bank’s 20 largest borrowers, with a loan of €5,4m.

In 2007, at the time Ruberto was acting as an agent in France for Landsbanki Luxembourg, she not only borrowed considerably funds but, allegedly, on very favourable terms. In March 2007, GD Invest borrowed €2,7m and then further €2.3m in August 2007, in total almost €5,1m. Allegedly, Ruberto invested €3m in properties pledged to Landsbanki but the remaining €2m were a private loan. It is not clear what or if there was a collateral for that part.

By the end of 2011, Ruberto’s debt to Landsbanki Luxembourg was in total allegedly €7,5m. In January 2012 it is alleged that the Landsbanki Luxembourg liquidator made her an offer of repaying €2,4m of the total debt, around 1/3 of the total debt. Ruberto’s track record of fraudulent behaviour from 2001, raises questions to her ties first to Landsbanki and then to Landsbanki Luxembourg liquidator. (The overview of Ruberto’s role is based on emails and court documents provided by Landsbanki Luxembourg equity release borrowers.)

Inconsistent information from the Landsbanki Luxembourg liquidator

From 2012, when I first heard from Landsbanki Luxembourg equity release borrowers, inconsistent information from the liquidator has been a consistent complaint. The liquidator had then been, and still is, demanding repayment of sums the clients do not recognise. There are also examples of the liquidator coming up with different figures not only explained by interest rates. The borrowers have been unwilling to pay because there are too many inconsistencies and too many questions unanswered.

As mentioned above, Landsbanki Luxembourg was put in suspension of payment, in October 2008 and then into administration in December 2008. As far as is known, people who later took over the liquidation were called on to work at the bank during this time. During this time, many clients were informed that their properties had fallen in value, meaning that the collateral for their loan, the property, was inadequate. Consequently, they should come up with funds. At this time, there was no rational for a drop in property value. This is one of the issues the borrowers have, so far unsuccessfully, tried to raise with the liquidator.

Other complaints relate to how much had been drawn. One example is a client who had, by October 2008, in total drawn €200,000. This is the sum this client want to repay. Mid October 2008, after Landsbanki Luxembourg had failed, this client got a letter from a Landsbanki employee stating that close to €550,000, that the client had earlier wanted transferred to a French account, was still “safe” on the Landsbanki account. This amount was never transferred but the liquidator later claimed it had been invested and demanded that the client repay it.

The liquidator has taken an adversarial stance towards these clients. The clients complain of lack of transparency, inconsistent information, lack of information and lack of will to meet with them to explain controversies.

The role and duty of a liquidator

By late 2009 the liquidator had sold off the investments. This is what liquidators often do: after all, their role is to liquidate assets and pay creditors. However, a liquidator also has the duty to scrutinise activity. That is for example what liquidators of the banks in Iceland have done. A liquidator is not defending the failed company but the interests of creditors, in this case the sole creditor, LBI ehf.

Incidentally, the liquidator has not only been adversarial to the clients of Landsbanki but also to staff. In 2011 the European Court of Justice ruled against the liquidator in reference for a preliminary ruling from the Luxembourg Cour du cassation brought by five employees related to termination of contract.

Liquidators have great investigative powers. In addition to documents, they can also call in former staff as witnesses to clarify certain acts and deeds. If this had been done systematically the things outlined above would be easy to ascertain such as: is it proper in Luxembourg that a bank systematically invests clients’ funds in the bank’s own bonds? Was the investment strategy sound – or was there even a strategy? Were clients’ funds systematically moved offshore without their knowledge? If so, was that done only to generate fees for the bank or were there some ulterior motives? And have these funds been accounted for? A liquidator can take into account the circumstances of the lending and settle with clients accordingly.

And how about informing the State Prosecutor of Landsbanki’s investments on behalf of clients in Landsbanki bonds and the offshoring of clients without their knowledge?

But having liquidators in Luxembourg asking probing questions and conducting investigations is possibly not cherished by Luxembourg regulators and prosecutors, given that the country’s phenomenal wealth is partly based on exactly the kind of dirty deals seen in the Icelandic banks in Luxembourg.

LBI ehf – the only creditor to Landsbanki Luxembourg

Landsbanki Luxembourg has only one creditor – the LBI ehf, the estate of the old Landsbanki Iceland. According to the LBI 2017 Financial Statements the expected recovery of the Landsbanki Luxembourg amounts to €84,3m, compared to €74,3m estimated last year. The increase is following what LBI sees as a “favourable ruling by the Criminal Court in Paris on 28 August 2017,” i.e. that all those charged were acquitted.

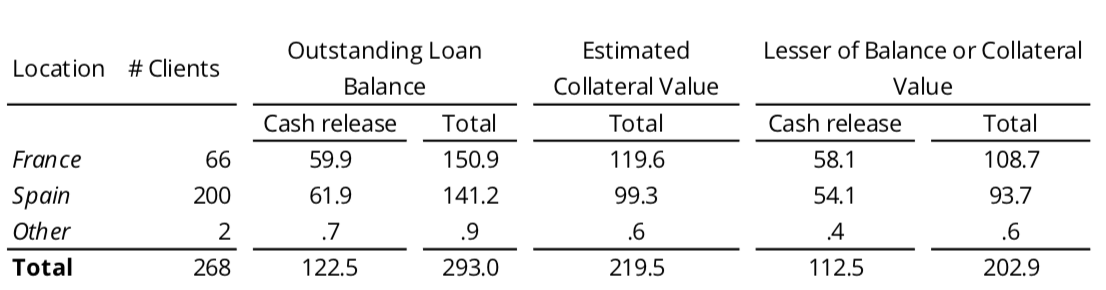

The only assets in Landsbanki Luxembourg are the equity release loans. The breakdown of the loans, in EUR millions, in the LBI 2017 Statements is the following:

Further to this the Statements explain that “LBI’s claims against the Landsbanki Luxembourg estate amounted to EUR 348.1 million, whereas the aggregate balance of outstanding equity release loans amounted to EUR 293.0 million with an estimated recoverable value … of EUR 84.3 million.”

As pointed out, the information “regarding legal matters pertaining to the Landsbanki Luxembourg estate is mainly based on communications from that estate‘s liquidator, and not all of such information has been independently verified by LBI management.”

Apart from the criminal action in Paris and the appeal of the August 2017 judgment, the Financial Statements mention other legal proceedings: “Landsbanki Luxembourg is also subject to criminal complaints and civil proceedings in Spain. … In November 2012, several customers in France and Spain brought a criminal complaint in Luxembourg against the liquidator, alleging that the former activities of Landsbanki Luxembourg are criminal and thus that the estate’s liquidator should be convicted for money laundering by trying to execute the mortgages. Other criminal complaints have been filed in Luxembourg in 2016 and 2017 based on the same grounds against the liquidator personally.”

This all means that “LBI’s presented estimated recovery numbers are subject to great uncertainty, both in timing and amount.”

What is Luxembourg doing?

It is not the first time I ask this question here on Icelog. In July 2013 there was the news from Luxembourg, according to the Luxembourg paper Wort, that there were two investigations on-going in Luxembourg related to Landsbanki. This surfaced in the Luxembourg parliament as the Justice Minister Octavie Modert responded to a parliamentary question from Serge Wilmes, from the centre right CSV, Luxembourg’s largest party since founded in 1944.

According to Modert both cases related to alleged criminal conduct in the Icelandic banks. One investigation was into financial products sold by Landsbanki. “…the deciding judge is making great strides,” she said, adding that in order not to jeopardize the investigation, the State Attorney was unable to provide further details on the results already achieved.”

Sadly, nothing further has been heard of this investigation.

In spring 2016 the Luxembourg financial regulator, Commission de surveillance du secteur financier, CSSF had set up a new office to protect the interests of depositors and investors. This might have been good news, given the tortuous path of the Landsbanki Luxembourg clients to having their case heard in Luxembourg – CSSF has so far been utterly unwilling to consider their case.

The person chosen to be in charge is Karin Guillaume, the magistrate who ruled on the Landsbanki Luxembourg liquidation in December 2008. As pointed out in PaperJam, Guillaume has been under a barrage of criticism from the Landsbanki clients due to her handling of their case, which somewhat undermines the no doubt good intentions of the CSSF. From the perspective of the Landsbanki Luxembourg clients, CSSF has chosen a person with a proven track record of ignoring the interests of depositors and investors.

So far, Luxembourg authorities have resolutely avoided investigating Landsbanki and the other Icelandic banks. In Iceland almost 30 bankers, also from Landsbanki, and others close to the banks have been sentenced to prison, up to six years in some cases (changes to Icelandic law on imprisonment some years ago mean that those sentenced serve less than half of that time in prison before moving to half-way house and then home; they are however electronically tagged and can’t leave the country until the time of the sentence is over).

In the CSSF 2012 Annual Report its Director General Jean Guill wrote:

During the year under review, the CSSF focused heavily on the importance of the professionalism, integrity and transparency of the financial players. It urged banks and investment firms to sign the ICMA Charter of Quality on the private portfolio management, so that clients of these institutions as well as their managers and employees realise that a Luxembourg financial professional cannot participate in doubtful matters, on behalf of its clients.

Almost ten years after the collapse of Landsbanki, equity release clients of Landsbanki Luxembourg are still waiting for the promised investigation, wondering why the liquidator is so keen to soldier on for a bank that certainly did participate in doubtful matters.

*In court, the French singer Enrico Macias mentioned that all his documents were in English. I found this strange since I had seen documents in French from other clients and knew there was a French documentation available. When I asked Landsbanki Luxembourg clients this pattern emerged. All the clients asked for contracts in their own language. When the non-French clients asked for contracts in English they were told the documentation had to be in French as the contracts were operated in France. Conversely, the French were told that the language was English as it was an English scheme. I have now seen this consistent pattern on documents for the various clients. – Here is a link to all Icelog blogs, going back to 2012, related to the equity release loans. Here is a link to the Landsbanki Luxembourg victims’ website.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Lessons from Iceland: the SIC report and its long lasting effect / 10 years after

The Bill passed by the Icelandic parliament in December 2008 on setting up an independent investigative commission, the Special Investigative Commission did not catch much attention at the time. The goal was nothing less than finding out the truth in order to establish events leading up to the 2008 banking collapse, analyse causes and drawing some lessons. The SIC report was an exemplary work and immensely important at the time to establish a narrative of the crisis. But in hindsight, there is yet another lesson to be learnt: its importance does not diminish with time as it helps to counteract special interests seeking to rewrite history.

There were no big headlines when on 12 December 2008 Alþingi, the Icelandic parliament, passed a Bill to set up an investigative commission “to investigate and analyse the processes leading to the collapse of the three main banks in Iceland,”which had shaken the island two months earlier. The palpable lack of enthusiasm and attention was understandable: the nation was still stunned and there was no tradition in Iceland for such commissions. No one knew what to expect, the safest bet was to not expect very much.

That all changed when the Commission presented its results in April 2010. Not only was the report long – 2600 pages in print in addition to online-only material – but it did actually tell the real story behind the collapse: the immensely rapid growth of the banks, from one GDP in 2002 to ten times the GDP in 2008, the stronghold the largest shareholders, incidentally also the largest borrowers, had on the banks’ managements, the political apathy and lax regulation by weak regulators, stemming from awe of the financial sector.

Unfortunately, the SIC report was not translated in full into English; see executive summary and some excerpts here.

With time, the report’s importance has not diminished: at the time, it clarified what had happened thus preventing those involved or others with special interest, to reshape the past according to their own interests. With time, hindering the reshaping of the past has become of major importance, also in order to draw the right lessons from the calamitous events in October 2008.

What was the SIC?

According to the December 2008 SIC Act (in Icelandic), the goal was setting up an investigative commission, that would, at the behest of Alþingi, seek “the truth about the run-up to and the causes of the collapse of the Icelandic banks in 2008 and related events. [The SIC] is to evaluate if this was caused by mistake or neglect in carrying out law and regulation of the financial sector in Iceland and its supervision and who could be held responsible for it.” – In order to fulfil its goal the SIC was inter alia to collect information on the financial sector, assess regulation or lack thereof and come up with proposals to prevent the repetition of these events.

In some countries, most notably in South Africa after apartheid, “Truth Commissions,” have played a major part in reconciliation with the past. Although the remit of the Icelandic SIC was to establish the truth, the SIC was never referred to as a “truth commission” in Iceland though that concept has been used in foreign coverage of the SIC.

The SIC had the power to make use of a vast array of sources, both by calling in people to be questioned and documents, public or private such as bank data, including data on named individuals, data from public institutions, personal documents and memos. Data, normally confidential, had to be shared with the SIC, which was obliged to operate as any other public body handling sensitive or confidential information.

Although the SIC had to follow normal procedures of discretion on personal data the SIC could “publish information, normally subject to discretion, if the SIC deems this necessary to support its conclusions. The Commission can only publish information on personal matters of named individuals, including their financial affairs, if the public interest is greater than the interest of the individuals concerned.” – In effect, this clause lift banking secrecy.

One source close to the process of setting up the SIC surmised the political intentions behind the SIC Act did not include lifting banking secrecy, indicating that the extensive powers given to the SIC were accidental. Others have claimed the SIC’s extensive powers were always part of the plan. I am in two minds about this but my feeling is that the source close to the process was right – the powers to scrutinise the main shareholders were far greater than intended to begin with.

Naming the largest borrowers, incidentally also the largest shareholders

Intentional or not, the extensive powers enabled naming the individuals who received the largest loans from the banks, incidentally their largest shareholders and their closest business partners. This was absolutely essential in order to understand how the banks had operated: essentially, as private fiefdoms of the largest shareholders.

In order to encourage those called in for questioning to speak freely, the hearings were held behind closed doors; there were no public hearings. The SIC had extensive powers to call people in for questioning: it could ask for a court order if anyone declined its invitation, with the threat of taking that person to court on grounds of contempt in case the invitation was declined.

Criminal investigation was not part of the SIC remit but its power to call for material or call in people for questioning was parallel to that of a prosecutor. As stated in the report, the SIC was obliged to inform the State Prosecutor if there was suspicion of criminal conduct:

The SIC’s assessment, pursuant to Article 1(1) of Act no. 142/2008, was mainly aimed at the activities of public bodies and those who might be responsible for mistakes or negligence within the meaning of those terms, as defined in the Act. Although the SIC was entrusted with investigating whether weaknesses in the operations of the banks and their policies had played a part in their collapse, the Commission was not expected to address possible criminal conduct of the directors of the banks in their operations.

As to suspicion of civil servants having failed to fulfil their legal duties, the SIC was supposed to inform appropriate instances. The SIC was not obliged to inform the individuals in question. As to ministers, the SIC was to follow law on ministerial responsibility.

The three members

The SIC Act stipulated it should have three members: the Alþingi Ombudsman, then as now Tryggvi Gunnarsson, an economist and, as a chairman, a Supreme Court Justice. The nominated economist was Sigríður Benediktsdóttir, then lecturer at Yale University (director of Financial Stability at CBI 2012 to 2016 when she returned to Yale). The chairman was Páll Hreinsson (since 2011 judge at the EFTA Court).

In addition to the Commission there was a Working Group on Ethics: Vilhjálmur Árnason professor of philosophy, Salvör Nordal director of the Centre for Ethics, both at the University of Iceland and Kristín Ástgeirsdóttir director of the Equal Rights Council in Iceland. Their conclusions were published in Vol. 8 of the SIC report.

In total, the SIC had a staff of around 30 people. As with the Anton Valukas report, published in March 2010, on the collapse of Lehman Brothers, organising the material, especially the data from the banks, was a major task. The SIC had access to the databases of the three collapsed banks but had only limited data from the banks’ foreign operations.

There were absolutely no leaks from the SIC, which meant it was unclear what to expect. Given its untrodden path, the voices expressing little faith were the most frequently heard. I had however heard early on, that the SIC had a firm grip on turning material into searchable databases, which would mean a wealth of material. With qualified members and staff, I was from early on hopeful that given their expertise of extracting and processing data the SIC report would most likely prove to be illuminating – though I certainly did not imagine how extensive and insightful it turned out to be.

Greed, fraud and the collapse of common sense

After the October 2008 collapse, my attention had been on some questionable practices that I heard of from talking to sources close to the failed banks.

One thing I had quickly established was how the banks, through their foreign subsidiaries, had offshorised their Icelandic clients. This counted not only for the wealthy businessmen who obviously understood the ramifications of offshorising but also people with relatively small funds. These latters had in many cases scant understanding of these services.

In the last few years, as information on offshorisation has come to the light via Offshoreleaks etc., it has become clear that Iceland was – and still is – the most offshorised country in the world (here, 2016 Icelog on this topic). Once the “art” of offshorisation is established, with all the vested interests accompanying it, it does not die easily – this might be considered one of the failed banks’ more evil legacies.

Another point of interest was how the banks had systematically lent clients, small and large, funds to buy the banks’ own shares, i.e. Kaupthing lent funds to buy Kaupthing shares etc. Cross-lending was also a practice: Bank A would lend clients to buy Bank B shares and Bank B lent clients to buy Bank A shares. This was partly used to hinder that shares were sold when buyers were few and far behind, causing fall in market value. In other words, massive market manipulation had slowly been emerging. Indeed, the managers of all three failed banks have in recent years been sentenced for market manipulation.

It had also emerged, that the banks’ largest shareholders/clients and their business partners had indeed been what I have called “favoured clients,” i.e. enjoying services far beyond normal business practices. One side of this came to light in the banks’ covenants in lending agreements: in the case of the “favoured clients,” the lending agreements tended to guarantee clients’ profit, leaving the banks with the losses. In other words, the banks took on far greater portion of the risk than these clients.

Icelog blogs I wrote in February 2010, before the publication of the SIC report, give some sense of what was known at the time. Already then, it seemed fair to conclude that greed, fraud and the collapse of common sense had been decisive factors in the event in Iceland in October 2008.

Monday morning 12 April 2010 – when time stood still in Iceland

The excitement in Iceland on Monday morning 12 April 2010 was palpable. The press conference was transmitted live. All around Iceland employers had arranged for staff to watch as the SIC presented its conclusions.

After Páll Hreinsson’s short introduction, Sigríður Benediktsdóttir gave an overview of the main findings regarding the banks, presenting “The main reasons for the collapse of the banks,” followed by Tryggvi Gunnarsson’s overview of the reactions within public institutions (here the presentations from the press conference, in Icelandic).

The main reason for the collapse of the three banks was their rapid growth and their size at the time they collapsed; the three big banks grew 20-fold in seven years, mainly 2004 and 2005; the rapid expansion into new/foreign markets was risky; administration and due diligence was not in tune with the banks’ growth; the quality of loans greatly deteriorated; the growth was not in tune with long-time interest of sound banking; there were strong incentives within the banks grow.

Easy access to short-term lending in international markets enabled the banks’ rapid growth, i.e. the banks’ main creditors were large international banks. With the rapid expansion, also abroad, the institutional framework in Iceland, inter alia the Central Bank and the FME, quickly became wholly inadequate. The under-funded FME, lacking political support, was no match for the banks, which systematically poached key staff from the FME. Given the size of the humungous size of the Icelandic financial system relative to GDP there was effectively no lender of last resort in Iceland; the Central Bank could in no way fulfil this role.

This had no doubt be clear to the banks’ management for some time. In his book, “Frozen Assets,” published in 2009, Ármann Þorvaldsson, manager of KSF, Kaupthing’s UK operation, writes that he “always believed that if Iceland ran into trouble it would be easy to get assistance from friendly nations… despite the relative size of the banking system in Iceland, the absolute size was of course very small.” (P. 194). – A breath-taking recklessness, naivety or both but might well have been the prevalent view at the highest echelons of the Icelandic financial sector at the time.

The banks’ largest shareholders and their “abnormally easy access to lending”

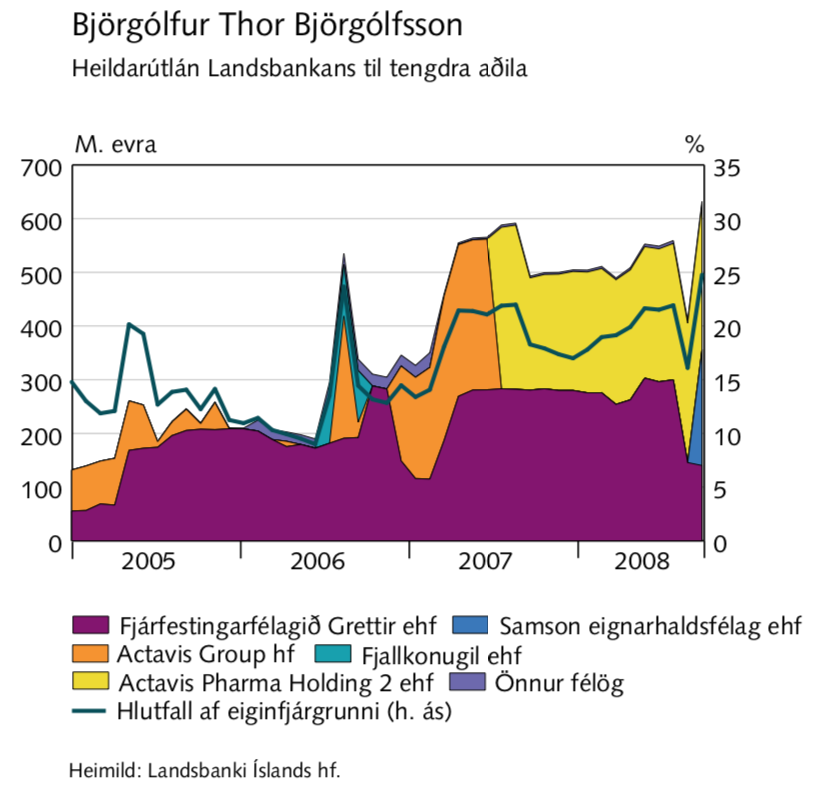

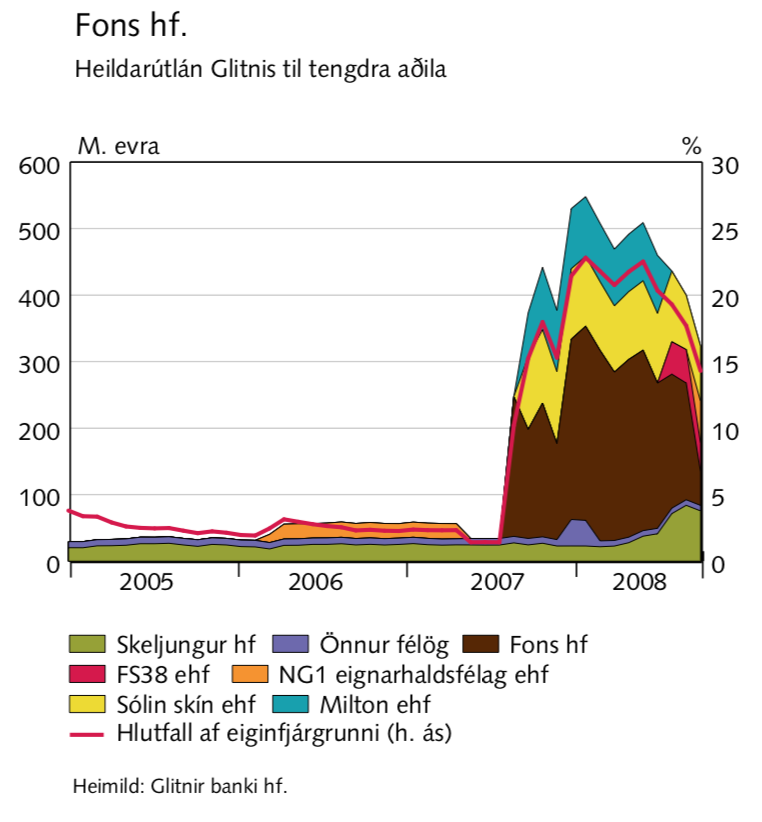

When it came to “Indebtedness of the banks’ largest owners” the conclusions were truly staggering: “The SIC concludes that the owners of the three largest banks and Straumur (investment bank where the main shareholders were the same as in Landsbanki, i.e. Björgólfur Thor Björgólfsson and his fater) had abnormally easy access to lending in these banks, apparently only because their ownership of these banks.”

The largest exposures of the three large banks were to the banks’ largest shareholders. “This raises the question if the lending was solely decided on commercial terms. The banks’ operations were in many ways characterised by maximising the interest of the large shareholders who held the reins rather than running a solid bank with the interest of all shareholders in mind and showing reasonable responsibility towards shareholders.” – Creative accounting helped the banks to avoid breaking rules on large exposures.

Benediktsdóttir showed graphs to illustrate the lending to the largest shareholders in the various banks. It is worth keeping in mind that these large shareholders all had foreign assets and were all clients of foreign banks as well. In general, the Icelandic lending shot up in 2007 when international funding dried up. At this point, the Icelandic banks really showed how favoured the large shareholders were because these clients were, en masse, getting merciless margin calls from their foreign lenders.

In reality, the Icelandic banks were at the mercy of their shareholders. If the large shareholders and/or their holding companies would default, the banks themselves were clearly next in line. The banks could not make margin calls where their own shares were collateral as it would flood the markets with shares no one wanted to buy with the obvious consequence of crashing share prices.

Two of the graphs from the SIC report, shown at the press conference in April 2010, exposed the clear drift in lending at a decisive time: to Björgólfur Thor Björgólfsson, still an active investor based in London and to Fons, a holding company owned by Pálmi Haraldsson, who for years was a close business partner of Jón Ásgeir Jóhannesson, once a king on the UK high street with shops like Iceland, Karen Millen, Debenhams and House of Fraser to his name.

The lending related to Fons/Haraldsson is particularly striking since Haraldsson was part of the consortium Jóhannesson led in spring of 2007 to buy around 40% of Glitnir: after the consortium bought Glitnir, the lending to Haraldsson shot up like an unassailable rock.

Absolution of risk

The common thread in so many of the SIC stories was how favoured clients – and in some cases bank managers themselves – were time and again wholly exempt from risk. One striking example is an email (emphasis mine), sent by Ármann Þorvaldsson and Kaupthing Luxembourg manager Magnús Guðundsson, jokingly calling themselves “associations of loyal CEOs,” to Kaupthing’s chairman Sigurður Einarsson and CEO Hreiðar Sigurðsson.

“Hi Siggi and Hreidar, Armann and I have discussed this (association of loyal CEOs) and have come to the following conclusion on our shares in the bank: 1. We set up a SPV (each of us) where we place all shares and loans. 2. We get additional loans amounting to 90% LTV or ISK90 to every 100 in the company which means that we can take out some money right away. 3. We get a permission to borrow more if the bank’s shares rise, up to 1000. It means that if the shares go over 1000 we can’t borrow more. 4. The bank wouldn’t make any margin calls on us and would shoulder any theoretical loss should it occur.We would be interested in using some of this money to put into Kaupthing Capital Partners [an investment fund owned by the bank and key managers] Regards Magnus and Armann”

This set-up, where the borrower is risk-free and the bank shoulders all the risk, has lead to several cases where bankers being sentenced for breach of fiduciary duty, i.e. lending in such a way that it was from the beginning clear that losses would land with the bank. (Three of these Kaupthing bankers, Guðmundsson, Einarsson and Sigurðsson, not Þorvaldsson, have been charged and sentenced in more than one criminal case).

The “home-knitted” crisis

Due to measures taken in October 2008 in the UK against the Icelandic banks, there was a strong sense in Iceland that the Icelandic banks had collapsed because of British action. The use of anti-terrorism legislation by the British government against Landsbanki greatly contributed to these sentiments.

A small nation, far away from other countries, Icelanders have a strong sense of “us” and “the others.” This no doubt exacerbated the understanding in Iceland around the banking collapse that if it hadn’t been for evil-meaning foreigners, hell-bent on teaching Iceland a lesson, all would have been fine with the banks. Some leading bankers and large shareholders were of the opinion that Icelanders had been such brilliant bankers and businessmen that they had aroused envy abroad: British action was a punishment for being better than foreign competitors (yes, seriously; see for example Þorvaldsson’s book “Frozen Assets”).

The story told in the SIC report showed convincingly and in great detail how wrong all of this was: the banks had dug their own grave. Icelandic politicians and civil servants had tried their best to fool foreign countries and institutions how things stood in Iceland. Yes, the turmoil in international markets toppled the Icelandic banks but they were weak due to bad governance, great pressure by the largest shareholders and then weak infrastructure in Iceland, as I pointed out in a blog following the publication of the SIC report.

This understanding is at times heard in Iceland but the convincing and well-documented story told in the SIC report has slowly all but eradicated this view.

Court cases and political controversies

Some, but by far not all, of the dubious deals recounted in the SIC report have ended up in court. The SIC brought a substantial amount of cases deemed suspicious to the attention of the Office of Special Prosecutor, incidentally set up by law in December 2008. However, most if not all of these cases had also been spotted by the FME, which passed them on to the Special Prosecutors.

CEOs and managers in all three banks have been sentenced in extensive market manipulation cases – the bankers were shown to have directed staff to sell and buy shares in a pattern indicating planned market manipulation. In addition, there have been cases involving shareholders, most notably the so-called al Thani case (incidentally strikingly similar to the SFO case against four Barclays bankers) where Ólafur Ólafsson, Kaupthing’s second largest shareholder, was sentenced to 5 1/2 years in prison, together with the bank’s top management.

In total, close to thirty bankers and major shareholders have been sentenced in cases related to the old banks, the heaviest sentence being six years. The cases have in some instances thrown an interesting light on operations of international banks, such as the CLN case on Deutsche Bank.

The SIC’s remit was inter alia to point out negligence by civil servants and politicians. It concluded that the Director General of the FME Jónas Fr. Jónsson and the three Governors of the CBI, Davíð Oddsson, Eiríkur Guðnason and Ingimundur Friðriksson, had shown negligence as defined in the law “in the course of particular work during the administration of laws and rules on financial activities, and monitoring thereof.” – None of them was longer in office when the report was published in April 2010 and no action was taken against them.

The Commission was of the opinion that “Mr. Geir H. Haarde, then Prime Minister, Mr. Árni M. Mathiesen, then Minister of Finance, and Mr. Björgvin G. Sigurðsson, then Minister of Business Affairs, showed negligence… during the time leading up to the collapse of the Icelandic banks, by omitting to respond in an appropriate fashion to the impending danger for the Icelandic economy that was caused by the deteriorating situation of the banks.”

It is for Alþingi to decide on action regarding ministerial failings. After a long deliberation, Alþingi voted to bring only ex-PM Geir Haarde to court. According to Icelandic law a minister has to be tried by a specially convened court, which ruled in April 2012 that the minister was guilty of only one charge but no sentence was given (see here for some blogs on the Haarde case). Geir Haarde brought his case to the European Court of Human Rights but the judgment went against him. Haarde is now the Icelandic ambassador in Washington.

The SIC lacunae

In hindsight, the SIC was given too short a time. With some months more, the role of auditors in the collapse could for example have been covered in greater detail. It is quite clear that the auditing was far too creative and far too wishful, to say the very least. The relationship between the banks and the four large international auditors, who also operate in Iceland, was far too cosy bordering on the incestuous.

The largest gap in the SIC collapse story stems from the fact that the SIC had little access to the banks foreign operations. Greater access would not necessarily have altered the grand narrative. But court cases have shown that some of the banks’ criminal activities, were hidden abroad, notably in the case of Kaupthing Luxembourg. – As I have time and again pointed out, it is incomprehensible that authorities in Luxembourg have not done a better job of investigating the banking sector in Luxembourg. The Icelandic cases are a stern reminder of this utter failure.

As mentioned above, only excerpts of the report were translated into English. To my mind, this was a big error and extremely short-sighted. Many of the stories in the report involve foreign banks and foreign clients of the Icelandic banks. The detailed account of what happened in Iceland throws light on not only what was going on in Iceland but also in other countries where the banks operated. The excerpts are certainly better than nothing but by far not enough – publishing the whole report in English would have done this work greater justice and been extremely useful in a foreign context.

Why the SIC report’s importance has grown with time

It is now just over eight years since the publication of the SIC report. Whenever something related to the collapse is discussed the report is a constant source and the last verdict. The report established a narrative, based on extensive sources, both verbal and written.

Some of those mentioned in the report did not agree with everything in the report. When they sent in their own reports these have been published on-line. However, undocumented statements amount to little compared to the report’s findings. Its narrative and conclusions can’t be dismissed without solid and substantiated arguments to counter its well-documented conclusions.

This means the story of the 2008 banking collapse cannot easily be reshaped. This is important because changing the story would mean undermining its conclusions and lessons to be learnt. In a recent speech, Tory MP Tom Tugendhat mentioned the UK financial crisis as the “forces of globalisation.” These would be the same forces that caused the collapse of the Icelandic banks – but from the SIC report Icelanders know full well that this is far too imprecise a description: the banks, both in the UK and Iceland, collapsed due to lack of supervision and public and political scrutiny, following year of lax policies.

Lessons for other countries

In order to learn from the financial crisis, countries need to know why there was a crisis – with no thorough analysis no lessons can be learnt. Also, not only in Iceland was criminality part of the crisis. Though not a criminal investigation, many of these stories surfaced in the SIC report, another important aspect.

Greece, Cyprus, UK, Ireland, US – five countries shaken and upset by overstretched banks, which needed to be bailed out at great expense and pain to taxpayers. However, all of these countries have kept their citizens in the dark as to what happened apart from some tentative and wholly inadequate attempts. The effect of hiding how policies and actions of individuals, in politics, banking etc, caused the calamities has partly been the gnawing discontent and lack of trust, i.a. visible in Brexit and the election of Donald Trump as US president.

Although Iceland enjoyed a speedy recovery (Icelog Sept. 2015), I’m not sure there are any particular economic lessons to be learned from Iceland. There were no magic solutions in Iceland. What contributed to a relatively speedy recovery was the sound state of the economy before the crisis, classic but unavoidably painful economic measures, some prescribed by the IMF, in 2008 and the following years – and some luck. If there is however one lesson to learn it is the importance of a thorough analysis of the causes of the crisis.

The SIC was, and still is, a shiny example of thorough investigative work following a major financial crisis, also for other countries. It did not alleviate anger; anger is still lingering in Iceland. An investigative report is not a panacea, nothing is, but it is essential to establish what happened and why, with names named.

There are never any mystical “forces” or laws of nature behind financial crisis and collapse. They are caused by a combination of human actions, which can all be analysed and understood. Without analysis and investigations it is easy to tell the wrong story, ignore the causes, ignore responsibility – and ultimately, ignore the lessons.

This is the second blog in “Ten years later” – series on Iceland ten years after the 2008 financial collapse, running until the end of this year.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

EU is financing Greece – as the Greek government persecutes ex-head of ELSTAT

The horrifying political prosecutions by the Greek government against the former head of ELSTAT, ongoing for seven years, is no longer just a Greek affair. The European Union is undermining Greek and European statistics by not taking a stronger stance.

Even the Greek newspaper Kathimerini has called the relentless prosecutions of Andreas Georgiou former head of ELSTAT “witch hunt.” Last year, the paper published a cartoon showing Kostas Karamanlis playing a videogame of chasing Georgiou. Karamanlis, prime minister from 2004 to 2009, is widely seen as the driving force behind the political persecutions against Georgiou and other ELSTAT staff. Karamanlis’ party, New Democracy, is in opposition and Karamanlis long out of office. The cases against Georgiou, now running for seven years, indicate that Karamanlis is still a political force to be reckoned with, a sign of ill omen for Greece.

Andreas Georgiou had been working at the IMF in Washington when he applied for the position of head of ELSTAT. When he took over in August 2010, the systematic falsification of Greek statistics, ongoing since before 2000, had already been exposed. During his five year in office, Georgiou and his staff made the last correction, rebuilt ELSTAT, helped introduce the necessary legal framework and fully implemented the statistical principles in the European Statistics Code of Practice: professional independence, impartiality and objectivity, commitment to quality and other principles. All of this was vital in order to put Greece on a more virtuous economic path, fulfilling its duties as a member of the European Union.

But this was more than the dark forces around Karamanlis and those who had been in power during the years of falsified statistics could endure. Although Georgiou and his staff had only been doing their duty as public servants and statisticians, the first prosecution started already a year after Georgiou took over at ELSTAT.

In 2015, when his five year term ended, Georgiou left ELSTAT and has now moved back to Washington DC. However, the preposterous abuse of power continues, giving good reasons to worry about the state of justice in Greece. There are several court cases ongoing – Georgiou has been charged with damages to Greece of €171bn, violation of duty, felony and slander. Acquittals have systematically been annulled, cases re-opened and new charges brought – an utter travesty of justice.

Economists, statisticians and others in the international community have time and again expressed support for Georgiou’s case, condemning the Greek government’s behaviour and the abuse of the justice system. There is now an international fundraising to meet Georgiou’s legal costs (see here, please consider supporting it).

As Georgiou said on May 29 when addressing the Financial Assistance Working Group of the Economic and Monetary Affairs Committee at the European Parliament the fact that these prosecutions have continued for seven years in Greece seriously undermines Greek and ultimately European statistics. This has long ceased to be only a Greek affair – it is a serious threat to European institutions.

As Georgiou pointed out incentives created in Greece “are poisonous. Would the responsibility for allowing such incentives to arise burden only the Greek State or also EU institutions and other EU stakeholders that are willing to live for years with this situation, which gives rise to these incentives?”

Further, Georgiou stated he was “not happy to report all this. But Greece—which I love dearly—will leave its troubles behind and prosper only if there is a firm commitment to credible official statistics. And this commitment will not be there—irrespective of anything that may be declared or signed—as long as the relentless prosecution of statisticians who followed European statistical law and statistical principles continues.”

Allowing these prosecutions to continue within the borders of the European Union surely undermines not only European statistics everywhere and the governance of the Union, but also the fundamental principles of human rights and the rule of law that the European Union is supposed to uphold and champion in the world.

Icelog has covered the ELSTAT case extensively since I visited Greece in 2015. In “Greek statistics and poisonous politics, July 2015, I explained in some detail the whole saga of the falsified statistics, the corrections and then the processes Georgiou put in place. Here is an overview of later blogs on the ELSTAT case. – Here is the link to the crowdfunding page with a short overview of Georgiou’s case and links to international media coverage of his case. Again, please consider donating.

UPDATE: the case of Andreas Georgiou has now taken a turn for the worse. The Greek Supreme Court has rendered “final and irreversible his conviction for not submitting the 2009 deficit and debt statistics to approval by a vote (this was judged to be a violation of duty, despite the fact that the European Statistics Code of Practice is very clear that statistics are not voted upon). This conviction makes final Andreas’ conviction to 2 years in prison, which is suspended for two years unless he gets another conviction in the meantime. Moreover, there is no further recourse in the Greek justice system for this case. The next step would be to take the case to the European Court of Human Rights.” See here, please consider supporting the crowd-funding for Georgiou’s legal defence. – Following the news, around 80 chief statisticians and heads of statistical associations from all over the world have published a statement, declaring their support for the cause of Georgiou, see their statement and names here.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Iceland: from fishing to tourism / 10 years on

For some years, Iceland has been the new darling of international tourism, giving the economy a real boost and healthy balance of payment. There are however some worrying signs – overheating is a clear and present risk, never far off in Iceland. The Central Bank warns against compounding risk in tourism and real estate, even more worrying if unhealthy practices in the old banks have not entirely been eradicated in the new ones. In addition, the growing dependence on tourism is, in itself, not entirely a healthy sign, especially as Iceland still lacks clear policy for tourism, which should ideally not be based on ever more tourists but sustainability.

“It’s either at ankles or ears” – This Icelandic saying, meaning it’s either too little or too much, certainly fits the Icelandic economy. Navigating the years following the 2008 banking collapse and laying a reasonably sound foundation for the future was done with reasonable success. Lately, tourism is reshaping the Icelandic economy.

In addition to classic crisis policies, luck played its part in the relatively speedy recovery – low oil prices, high fish prices in international markets and last but not least, Iceland’s popularity as a tourist destination. Consequently, Iceland has, again, seen booming growth– 7.5% of GDP 2016 and 3.6% 2017 with forecast of 2.9% this year.

This time the growth is not leveraged; Icelanders can literally see the cash cows walking around in colourful outdoor clothing: since a few years, tourism, not fishing, is the largest sector in the economy. Though tourism has done miracles for the balance of payment and strengthened the króna to record levels, tourism may not bode much good for young Icelanders.

Add to that the interdependence of tourism, housing and foreign workers and the conclusion is the one reached in the Central Bank of Iceland’s latest Financial Stabilityreport: “Risks relating to tourism and high house prices could interact.”

Why did Iceland become such a popular destination?

The huge growth in tourism over the last few years has taken Icelanders by surprise; a common question is: “Why is Iceland suddenly so popular?” followed by: “Will this popularity last?”

As to the “why” did not entirely materialise out of thin air. Icelandair and later Icelandic tourist authorities have over the years and decades run rather successful campaigns. Posters with glorious photos from Iceland have for example appeared regularly on the walls in London tube stations.

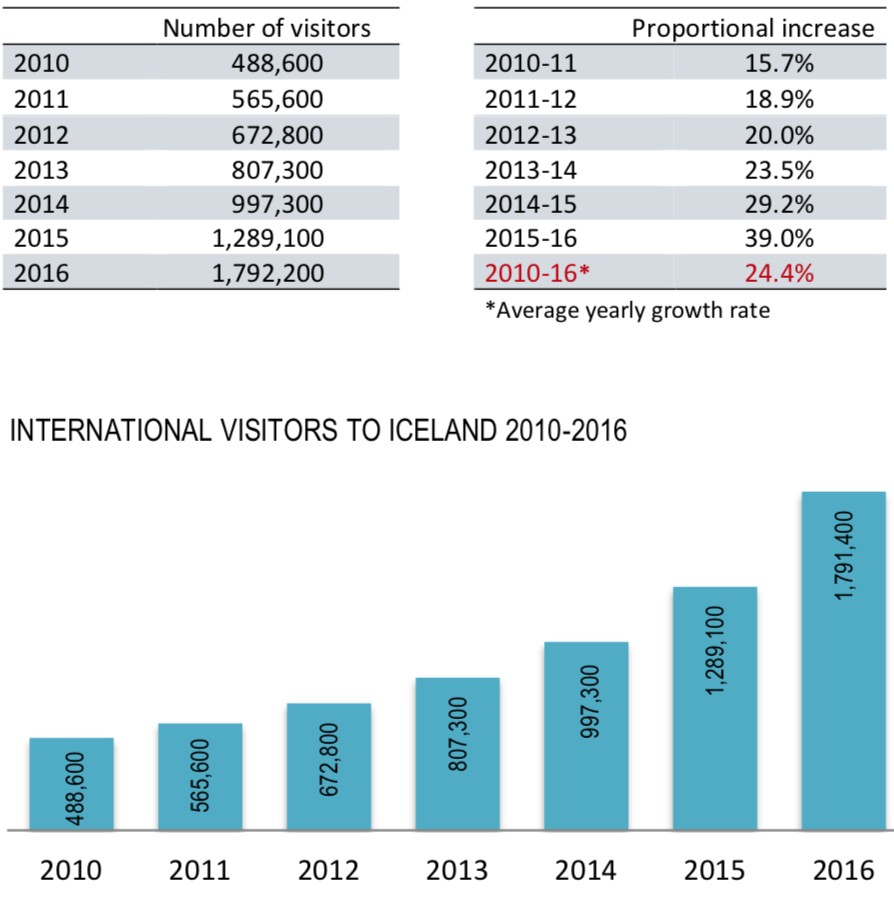

The rise in tourism was not as sudden as it might seem – there had been a steady increase since 2003 when the number of tourists were 320.000, then roughly the size of the population, growing by 3.5% to 15.1% a year until a downturn by 1.6% and 1.1% in 2009 and 2010 – though the great increase 2014 to 2016 were indeed staggering.

Icelandic Tourist Board (International visitors and cruises)

Currency fluctuations have at times made Iceland an expensive destination. That changed for some years after the 2008 banking collapse, making Iceland quite a reasonable destination until around 2014.

Luck helped Iceland when it came to international reports of the banking collapse. At the first Greek bailout in 2010, I did some comparison of international reporting of the crisis in the two countries. As in Greece there had been dramatic scenes of demonstrations and some altercations in the centre of the Reykjavík during the winter of 2008 to 2009.

But quite remarkably, foreign media would often choose to adorn reports from crash-struck Iceland with glorious landscapes rather than demonstrations, fire and fury. Greece also has spectacular and photogenic nature but the Greek financial crisis seemed more often shown in pictures of violent clashes and aggressive graffiti than alluring landscapes.

Far from being the negative impact feared at first, the Eyjafjallajökull eruption in April 2010 proved a gift literally from heaven for Icelandic tourism. An eruption is an awe-inspiring magnificent thing to behold; the Eyjafjallajökull coverage had quite an impact in drawing attention to the island.

The Instagram effect has helped. With the rise of Instagram, the popularity of Iceland was bound to rise – the island is a stunning Instagram backdrop.

Will the popularity last?

“The experience is that if you have a tourism boom of this magnitude, it is there to stay. There might be some ebb and flow, but tourism will, to my mind, continue to be one of the main pillars of the economy. That means we need to manage it well,” said Már Guðmundsson governor of the CBI in an interview with IMF2017.

Common sense dictates that the increase in tourism by 30% to 40% is unlikely to continue but experience from other countries shows that surge in tourism is durable – tourists are not as fickle as fish. According to an IMF study, countries whose travel exports increased by at least 4% of GDP over a decade were likely to see the number of tourists above the pre-surge levels ten years later. Iceland is a case in point – even the drop in arrivals in 2009 and 2010 did not change the underlying trend.

The latest figures show however a dramatic turnaround: the increase the four first months this year was 3.7% compared to last year. The increase was 28.6% 2014 to 2015, 34.7% 2015 to 2016 and a staggering 55.7% 2016 to 2017. The stats do indeed show a decline but all in all still a healthy growth though not the staggering growth of the record years.

In countries where the numbers did indeed decline, the causes are most often political turmoil, crumbling infrastructure – and most interestingly if also worryingly, from the Icelandic perspective – overcrowded tourist sites, environmental degradation and loss in price competitiveness.

The forecast for this year had been 2.2m but there are already some indications that this figure will be lower, even substantially lower. In addition to overcrowding and environmental degradations, difficult to measure, there is the loss in price competitiveness.

With the strong króna Iceland has become the most expensive tourist destination in Europe, even more expensive than Switzerland and Norway. The effect is bordering on the ridiculous: an underwhelming main course at €35 buys in a Reykjavík restaurant doesn’t compare with the quality of a main course at this price in the neighbouring countries.

Manifestos on tourism – but so far, little action

All of this is highly relevant to tourism in Iceland and merits a close scrutiny as it helps to identify the possible weaknesses.

All indicators show that tourists go to Iceland to experience nature. Even if they only go for a long weekend in Reykjavík they will almost certainly go on a tour for a day. The fantastic aspect of Iceland is that nature is not distant to urban areas, i.e. Reykjavík; it’s all around, in sight and easily accessed. The island is small, distances short. But there are some indications that overcrowding and faulty infrastructure is starting to detract from the pleasures of visiting the most famous places.

Arriving at Þingvellir or Geysir, with these spectacular spots hidden on arrival by dozens of buses and the passengers that spill from them, is not optimal. On the other hand, there are plenty of little known places to be enjoyed in solitude though it may take some research to find them.

As both the IMF and the OECD have pointed out in recent reports on Iceland, the varying governments over the last few years have failed to form a coherent policy for tourism in Iceland. The last three governments that came to power – in 2013 Progressives with the Independence party, in 2016 the Independence party with Bright Future and Revival and the present one, 2017 Left Green with Independence party and the Progressives – had all set high goals for tourism in their manifestos.

All of them aimed at forming a coherent policy for tourism, including plans to tax the sector in order to fund the necessary infrastructure for sustainable tourism. Nothing, absolutely nothing, has come of these well-intended manifestos – there is no policy and consequently, no plan on which to form a coherent tax policy.

Rudderless tourist economy

Managing the tourism boom, as governor Guðmundsson mentions, is still lacking in Iceland. The danger is that without a policy that aims at building up a quality tourism, fitting the (unavoidably) high prices, tourists will soon shun Iceland because they hear too much of crowded attractions and crumbling infrastructure with the pictures on social media to prove it.

With nature like the Icelandic one and high prices, the aim should not be to increase the number of tourists but develop tourism where fewer tourists spend more. This is what Costa Rica and Ireland have successfully done. Again, this requires strategic policies, so far wholly lacking in Iceland.

An economy of diminishing opportunities for high skills and education

Once upon a time in Iceland, there was little to be gained from lengthy education in order to be a high earner. Being a fisherman on a trawler meant very high salary and owning a large house as can still be seen in small fishing villages around the country. Working as a tradesman could also mean good salary.

This is no longer the case. There are fewer trawlers than earlier; a job on a good trawler is harder to come by than a highly paid managerial job. And the construction industry is not providing the same well-paying jobs as earlier. The large construction companies are very different from the small-scale constructor who hired his relatives to work for him.

All movements in a small economy like the Icelandic one tend to be rapid. The rise of tourism is no exception. The labour-intensive tourist sector is gobbling up a lot of manpower. The Dutch Disease might be around the corner, especially in an economy where the largest sector is mostly lacking direction and policies.

Recently, I have heard a number of Icelandic parents express their worries of what the labour market will offer their children in the coming years. In this rudderless tourist economy, there is no policy to develop other sectors. There is a budding tech sector in Iceland but some of the most successful Icelandic tech entrepreneurs have moved abroad and encouraged others to do the same, for the lack of tech infrastructure in Iceland. There is also a small pharmaceutical sector that could be developed further.

But a visionary policy of a diversified economy needs a government with a vision – and that has so far been lacking. The strong economic growth seems to lull Icelandic politicians into complacency. But a country that does not offer its young people the opportunities to seek education and then make use of it at home is not a good place to be. That’s greatly worrying many Icelandic parents.

More Icelanders leaving than returning

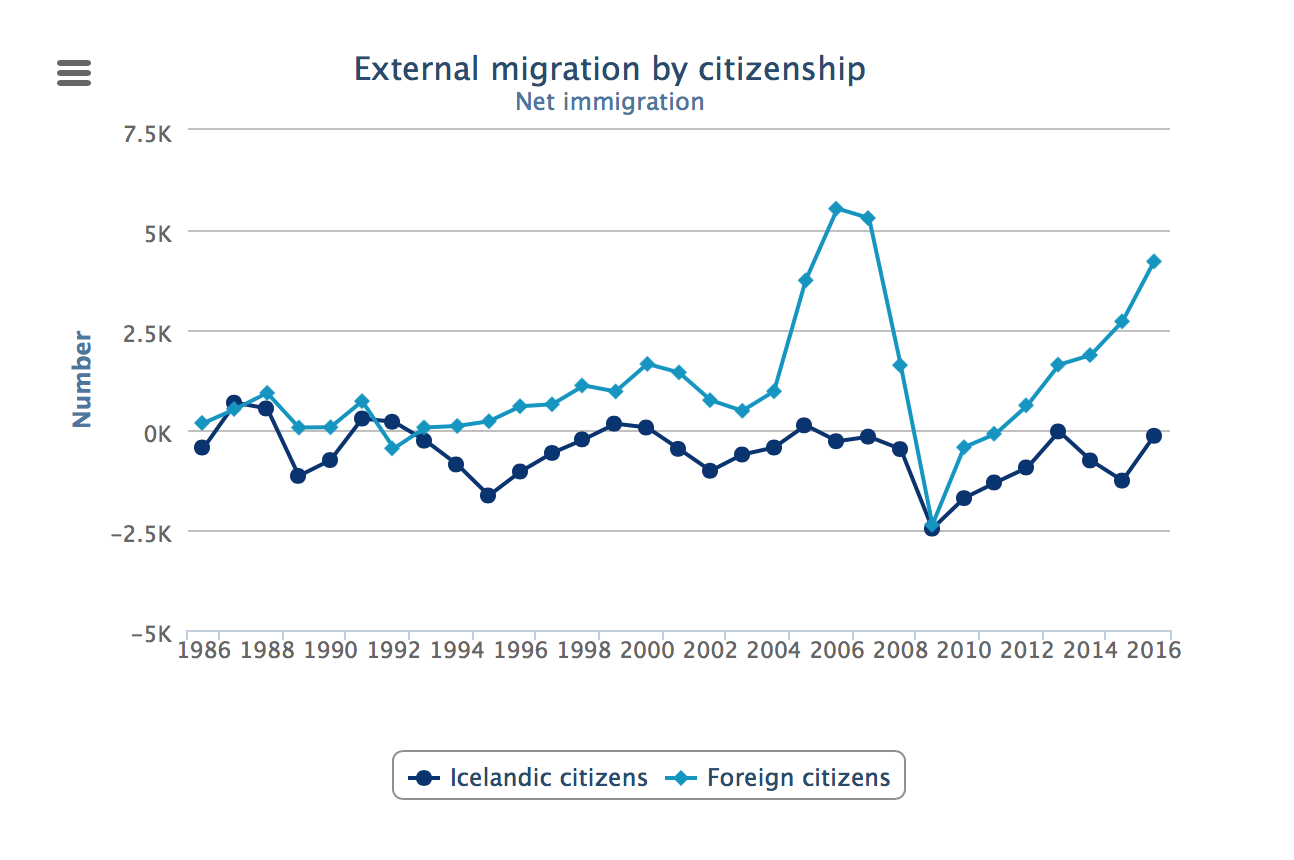

The demographics of Iceland is pretty healthy, it’s a nation of young people, compared to some other European nations. Icelanders are now just over 350.000, the number rises steadily. Except for a few years in the 1960s, 1970s and 1990s and then more recently in 2009, 2010 and 2011, more people enter the country than leave.

This looks promising – the nation is growing and more people move to Iceland than leave. However, there is potentially a more worrying underlying trend: in spite of the boom, more Icelanders are leaving Iceland than Icelanders moving home. Foreign nationals are keeping the inflow figures up – more foreigners come to Iceland than leave.

After the 2008 banking collapse whole sectors like construction were nearly wiped out, meaning not only the construction workers and tradesmen but also architects and engineers. Icelanders left in droves, both families and individuals, for work abroad. Norway was a particular popular destination as well as Denmark and Sweden.

The interesting – and for the Icelandic economy, worrisome – thing is that this flow has not stopped though the figures are lower. Icelanders are still leaving for jobs abroad. This, in addition to the decades-long tradition of young Icelanders seeking education abroad, returning as they graduate.

In 1999, 2000 and 2005 more Icelanders moved to Iceland than left but that is the exception. The rule is the other way around: more Icelanders leave than return. The one question Icelandic politicians really do not like to be asked is how they explain that in spite of the boom, there are still more Icelanders moving abroad than returning: