Search Results

Time to start reading up on Slovenia?

Is Slovenia the next Euro-domino to fall? That is a continuously repeated forecast. But what is the outlook and what are the financial facts?

Recently I spoke to a banker familiar with Slovenian banks. He was reasonably optimistic. The new Government seemed to be taking imminent problems quite seriously – but corruption remains a problem, he said.

According to a Eurobarometer 2012 study of perceived corruption in the 27 EU countries Slovenia topped the list of perceived increased corruption: 74% of Slovenian respondents thought the corruption was increasing, with 73% in Cyprus right behind. This bodes ill for Slovenia since a corrupt country might be less likely to taka the necessary but painful initiatives. However, the new Government has already shown some understanding of what is needed. Recent development in Cyprus might also have concentrated its mind.

On February 28 Prime Minister Janez Jansa, a conservative, lost a vote of confidence due to allegations of corruption amid economic gloom. The new PM is the leader of the opposition Alenka Bratusek, a liberal former civil servant. So far, the most serious allegation of corruption brought against Bratusek is that she had plagiarised one page in her PhD thesis – recently a common vice among German politicians. There are many intellectuals in the new Government, i.a. the minister of culture, Jernej Pikalo who since 2006 has been a visiting professor at the University of Bifroest, Iceland, lecturing on globalisation. Consequently, he should be familiar with what has and has not been done in Iceland post-collapse.

Fitch and the IMF on Slovenia

In a note 22 March 2013 from Fitch Ratings the assumption “remains that Slovenia will be able to avoid requesting international financial assistance. Maintaining investor confidence and therefore the ability to borrow in the market on reasonable terms will require the incoming government to finalise and implement legislation on a bad bank solution and state asset management company. Failure to tackle these issues in a timely manner would increase pressure on the ‘A-‘ sovereign rating.” (Emphasis mine in all quotes).

In the Concluding Statement March 18 2013 of the IMF staff visit to Slovenia the summary reads:

A negative loop between financial distress, fiscal consolidation, and weak corporate balance sheets is prolonging the recession. Prompt policy actions are necessary to break this loop and restart the economy. Repairing the financial sector and improving corporate balance sheets is of the essence. The Bank Asset Management Company is an effective way to clean bank balance sheets. Banks should be quickly recapitalized. A clear and coherent plan is key to access international capital markets quickly. Fiscal consolidation should continue to reduce the structural deficit, while letting the automatic stabilizers work. Recent labor market and pension reforms are steps in the right direction.

What needs to be done?

As can be seen above the IMF statement points out that a “negative loop between financial distress, fiscal consolidation, and weak corporate balance sheets is prolonging the recession.”

The numbers do not look promising. “Real GDP declined by 2.3 percent in 2012 as domestic demand shrank severely.” Here, Slovenia is in league with the worst performing countries such as Greece and the forecast for this year is a further contraction by 2%. However, growth is in sight for next year, depending on implementation of promised reforms, continued market access and – most elusive of all – growth in the Eurozone.

Quite promising, Slovenia has already set up the Bank Asset Management Company (BAMC) and a sovereign state holding company. This is the necessary framework to tackle much needed bank restructuring, debt overhang of corporate debt, improved governance and cutting back on state involvement in the economy. If all of this would be pushed in the right direction much could be achieved. Again, this “if” might prove elusive.

Fiscal consolidation, downsized public sector, labour market reform and more friendly attitude towards foreign investors (Slovenians seem even more hostile than Icelanders to foreign ownership in their economy) are all areas that are being worked on and need more.

The sick part of the economy: banks

No surprise here – the banks are under severe distress. That is of course ominous since we have seen banks causing severe problems in a country after country in the Eurozone (and of course beyond, Iceland being a case in point).

The rapid rise in non-performing loans is a sign of danger and distress in the Slovenian banking sector:

The share of nonperforming claims in total classified claims increased from 11.2 percent at the end of 2011 to 14.4 percent in 2012. The three largest banks saw their ratio increase from 15.6 percent to 20.5 percent in the same period with about ⅓ of their corporate loans non-performing. Meanwhile these banks have repaid the bulk of their debt with foreign private creditors, while increasing reliance on the ECB.

With BAMC the first steps towards a spring-cleaning of balance sheet have been taken but now the brooms and detergents have to be put to a ruthless use. To its relief, the IMF mission notes that international experts have been appointed as non-exec members on the BAMC board.

But the corporate sector – intertwined with banks – is not too healthy either

If the Slovenian corruption is similar to what is coming to light in Cyprus, the danger is that some of these non-performing loans have been given more on grounds of cosy relationships than business rationale, which might then indicate that the collaterals are not water-tight. Again, of course this can be handled professionally if the political powers stay away and the experts are allowed to deal expertly with the problems.

Cross ownership between large corporations, financial holding companies and banks is reminiscent of Iceland pre-collapse. It is a very bad sign indeed. “The debt to equity ratio is among the highest in Europe.” Primitive bankruptcy law make bankruptcy procedures lengthy and are a serious obstacle in dealing with debt. – Hopefully, the new Government gives priority to new bankruptcy legislation since this a mundane but often overlooked problem.

And then there is this:

Viable publicly-owned undercapitalized companies should be recapitalized by the state or attract private capital. However, the mission cautions the authorities against taking actions on debt restructuring or recapitalization that can lead to ineffective use of public funds. Finally, Slovenia has to address corporate governance weaknesses. A Report of Standards and Codes on Corporate Governance by the World Bank and the OECD could help in this respect.

To me this looks like a loud and clear corruption warning without the C-word mentioned.

Funds needed

But even experts cannot be expected to make something out of nothing. The IMF mission points out that transferring bad assets to BAMC is no substitute for real money needed to recapitalise the banks. The three largest ones need around €1bn this year – and if economic conditions deteriorate more might be needed.

Financing requirements are particularly pronounced in summer, with bank recapitalization needed soon and a large 18-month T-bill coming due in June. In all, financing needs for the remainder of the year (excluding the bonds to be issued by the BAMC) could reach some € 3 billion, and possibly more depending on bank recapitalization needs. A large part of this financing need should be met via external borrowing, given banks’ inability to absorb large amounts of government paper, but also to improve the maturity structure of government debt and reduce rollover risk. This highlights the importance of safeguarding market access in the near term.

To give context to the figures above the Slovenian GDP in nominal terms amounted to €35,466m in 2012. The uplifting figure is that debt to GDP was, in 2012, 52.5%.

Over at least 18 months Cyprus had plenty of warnings, its banks were in ECB intensive care for months and yet nothing was done until the patient was almost thrown out of the intensive care, also called “Emergency Liquidity Assistance.”

The key issue is that Slovenia is ok as long as it manages to remain on good terms with the markets – or as long as the markets are keen and willing to be on good terms with Slovenia. And if not… Well, we all know – it ends with an all-night meeting in Brussels, a bail-out at sunrise – or more recently a bail-in – and since that is never enough, it is followed later on by easing of terms and an uncertain future.

But perhaps Slovenia will show that this time it can be different.

*Here is a link from Global Finance to key figures of the Slovenian economy such as GDP, debt, unemployment and all these things that make a nerdy heart beat faster. Here is a link on the economy from the Slovenian Statistical Office.

*Update May 2: here is a Bloomberg article from yesterday when Moody’s cut Slovenia’s rating to junk.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

A Cypriot Icesave coming up – and winding up Laiki Bank – updated

As Icelog has pointed out earlier, there are many similarities between Iceland and Cyprus. One of them is Icesave.

If Laiki Bank, a badly hit Cypriot bank, folds it will leave some depositors in the UK under a Cypriot Deposit Guarantee Scheme because Laiki, apparently, has branches in the UK, not subsidiaries. As Landsbanki’s Icesave accounts, set up as a branch, showed so clearly these depositors will have to seek to Cyprus for their deposit guarantees. If Laiki operations in the UK had been in a subsidiary it would fall under the UK DGS.

Ever since Icesave the UK Financial Services Authorities have had their eye on branches. But they seem to have reacted somewhat slowly – Icesave collapsed over four years ago, in October 2008. Yet another failure on part of the FSA.

The lesson from Iceland is that if Laiki folds it is very important that insured deposits are moved into a new entity (for which funds are needed) and the rest left to a resolution company. (In Iceland, all deposits were insured, no minimum).

What Iceland did – which has proved very beneficial to uninsured deposits (which were the deposits abroad) – is that in the Emergency Bill (passed into law just as everything was collapsing October 6 2008) deposits were made a priority claims in bankruptcy. This meant that uninsured depositors get paid first, i.e. have hope of getting something back.

This was relevant not in Iceland but in the Icesave branches in the UK and the Netherlands because these deposits were then given priority and will actually get fully reimbursed. But alas, one’s gain is another’s loss – it means that other creditors to Landsbanki’s foreign operations aren’t getting very much.

What happened in Icesave was that the UK and the Dutch did reimburse depositors (to avoid unrest) but then wanted this money back from Iceland. Iceland resisted – and now in January the EFTA Court ruled that because it was a major systemic failure Iceland did not need to reimburse the two governments. (This is a hotly disputed outcome, the European Court of Justice might see it differently).

In a situation like in Iceland and Cyprus, someone will feel the pain. In Iceland, ordinary deposit holders lost 30-40% of their ISK deposits, measured in euro. Exiting the euro is no solution for Cyprus. With banks kept alive since January by the ECB’s Emergency Liquidity Assistance, the Cypriot catastrophe has been on the horizon for a while. It is a pity that it was not better prepared when the crash finally came.

But now it is here and something needs to be done. Iceland managed to do a few things right – helped by the fact that the there were foreign creditors that could be forced to take the greatest loss, ca 5-6 times the Icelandic GDP – painful though it was. It seems that the Cypriot shock might be greater, no clear cut group of foreign creditors who can be forced to swallow losses. Still, for Cyprus a quick stab might be better than the lingering pain the Greeks have lived with for far too long.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Ireland and Iceland – better to let fail or to bail out?

When it comes to bailing out banks Ireland and Iceland chose different paths. Interestingly, there are those who see the two countries as a test of whether it is better to let the bank system fail – or bail it out. That is at least how Jim Leaviss, head of retail fixed interest at M&G Investments is quoted as saying in an article on Ireland in the FT (subscription needed). “Iceland and Ireland were a test of whether it was better to let your bank system collapse or bail it out. So far it is not clear which was best. Irish bond yields have fallen a lot but that was skewed by the ECB’s actions.”

On the basic indicators, growth and unemployment Iceland, is doing much better.

Unemployment: Iceland: 4.5% – Ireland: 15.1%

Growth 2011/2012 (forecast): Iceland: 2.6% / 2.5% – Ireland 0.7% / 0.9%

The Irish ray of light these last days is the notch up by Fitch: from negative to stable (for those who still take any notice of the big rating firms), at BBB+.

As I’ve pointed out earlier it is however a myth that Iceland didn’t bail out its banks. It did bail out some smaller financial institutions to quite a cost but it didn’t bail out its three big banks – Kaupthing, Glitnir and Landsbanki – in October 2008. From early 2008, the Government (a coalition of the Independence Party, conservative and the social democrats, who now lead the Government) and the Central Bank did try to get loans from all and sundry to prepare for this eventuality – it did get a credit swap from the Scandinavian central banks of €1.5bn – but not enough to save the banks. The reality was that the banks couldn’t be saved.

The Icelandic Government has posted what amounts to 20-25% of GDP in bailing out – or trying to bail out – various other financial institutions and one insurance company. Some of this might be recovered later on but some of it is already lost. It is therefor not correct to say there were no bailouts in Iceland and therefore Iceland is not a crystal clear case of no bailouts vs bailouts.

As I have also pointed out earlier, the recovery in Iceland can partly be attributed to wide-reaching write-downs, both for companies and individuals and for changes in the bankruptcy law. All of this helps but it is over-simplification to say that there is any one policy that has made all the difference.

Ireland and Iceland have been very much in my mind for the last two days. I’ve been immersed in all things Irish, attending a conference at Goldsmiths University on the Future State of Ireland, brilliantly organized by Derval Tubridy senior lecturer in English Literature and Visual Culture at Goldsmiths. With illuminating lecturers like columnist and adviser to the EU on corruption Elaine Byrne, Roy Foster professor of Irish History at Oxford, Luke Gibbons professor of Irish Literary and Cultural Studies at National University of Ireland and journalist and writer Fintan O’Toole, this was bound to be an interesting event.

When I first saw the programme for the conference (which Elaine drew my attention to; thanks Elaine) and saw there were some artists involved my first thought was that this was most likely going to be a pretty fluffy event. It turned out to be the contrary – a very dense event with a fascinating insight into Irish History, culture and the Irish psyche.

The artist duo (Gareth) Kennedy (Sarah) Browne showed a video of ‘How Capital Moves’ – taking inspiration from an American company moving from Ireland to Poland. The story of this move is told from several aspects by creating several characters, all lovingly portrayed by one Polish actor. It’s funny and witty but also sadly true, based on words from people working for this company.

The photographer Anthony Haughey has been photographing the Irish and their surroundings for over 20 years, immigrants in this country of emigrants, as well as looking at parallel stories in other nations. His light is the living light caught by long exposures during the night. This profound realism – real as it gets – turns into strangely surreal scenes. The almost disturbingly beautiful photos reveal tension and troubled lives – portraying at the same time striking, still images and strong stories.

Foster’s stories of Irish radicals in the early 20th century seemed to indicate that something is lost in modern Ireland. Where is the radicalism now? Yet, listening to O’Toole and Byrne there doesn’t seem to be any lack of radical thought among journalists and columnists – and interestingly, Jim Clarke at Trinity College pointed out that the tabloids, though conservative in many ways, have been better at portraying people’s anger and disgust, than others.

There is one thing that Ireland has and not Iceland: a strong diaspora. That enriches the debate since it is easier being an outsider looking inside. Ireland is a small country where people speak carefully because everything and everybody is connected. A journalist who in the 1970s spoke of politicians taking bribes, proven right 40 years later, was at the time ostracized and forced to emigrate.

“Shame” and “blame” were two words that ran through the debate. For foreigners it’s easy to forget the other great power in Ireland, next to the state – the Catholic Church. The Irish have not only been thrown into economic turmoil, seeing the political class fail – but also seen grotesque moral failure and criminal child-abuse exposed in the church. Interesting times for the Irish – as was so strongly born out at the conference.

What the Irish still lack is a comprehensive overview of the collapse of their banks. To my mind, the Irish still have only a sporadic evidence of how they have been governed this last fateful decade before their main banks collapsed. The feeling in Ireland is that they do know it all. Before the SIC report was published in April 2010, Icelanders thought the same. The report showed that things had been much worse than even the most pessimistic thought: a complete failure of politicians, regulators, the Central Bank, the business “elite” – and of course the private banks, where bank managers are now being charged by the Special Prosecutor and sued by the three banks’ Winding-up boards. – In terms of legal action against bankers there is peculiarly little happening in Ireland.

It’s difficult to say which of the two countries will fare better. I still believe it’s been wrong for European governments to save failed banks. In Iceland, it was a relatively easy decision to take – there was no alternative regarding to the three big banks. The fact that the creditors were foreign financial institutions – mainly German banks – made it easier, both politically and financially.

Interestingly, it was the same with the Irish banks. Also there, the creditors were mainly foreign and yes, mainly German. But the sums in Ireland were much bigger – and the European Central Bank and the Germans weren’t happy to see banks fail in the euro zone: the ECB because of principles and euro pride; the Germans because German banks were at risk. The Germans are rather sanctimonious about their banks – after all, they are still standing. But the story is that German banks were prudent at home but wrecked havoc abroad – the German banks have been like teenagers who are model kids at home but cut up the furniture and paintings on the walls when they go partying out of their parents’ sight.

As has later become evident, the troika treatment of Ireland in November 2010 set the example of private bank debt migrating to the state, turning the state into an unsustainable borrower – as has now happened in Greece, Portugal and Cyprus, with Spain fiercely resisting to pick up that lethal same burden.

For every imprudent borrower there is a risk-blind lender. With the one-notch up on the Irish rating scale some will hope that the example made of Ireland will turn out to be the good example. There are voices in Ireland saying it is just not fair for the state – and the taxpayers – to be paying the privately accrued debt. It is painful to see the Irish struggling with the debt, which was so recklessly showered over them.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

The Western banking crisis in the shadow of corrupt practices

Today, the Spanish Government formally asked for aid to recapitalise its banks – the word “bailout” isn’t mentioned but that’s what this aid is – and no numbers mentioned either. Even €100bn might only offer the briefest relief. Cyprus’ bid today for the same mostly goes unnoticed. Apparently Russia’s aid to the island isn’t enough. Will the EU keep on throwing good money after bad, without digging out the roots of corrupt banking practices?

Do you remember in 2008 when some British, Irish and American banks were below sea-level and people pointed at Spain and Spanish banks as the example to follow? Those were the days – days of Spanish clever accounting, not of their banks’ rude health. That’s a point made in a clear and insightful article, “The EU Smiled While Spanish Banks Cooked Their Books,” by Bloomberg’s Jonathan Weil.

At the core of the Spanish loan debacle are local banks, the cajas, heavily connected to the construction sector and local politicians, just like in Ireland. The Mahon report uncovers the unhealthy relationship in Ireland in the 80s and the 90s between these two elements: the building sector and politics. A relationship that has a lot to do with the escalating debt of the Irish financial sector, which the EU then forced the Irish state to shoulder. The cajas saga seems to mirror the Irish state of things completely, even down to brown envelopes.

Spain now needs billions to save its banks – €65-100bn, depending on the calculation – the official Spanish bid for a bailout today doesn’t come with a number. At the centre of this salvage project is Bankia – a bank created in 2010 out of several of the worst cajas, with – as is now turning out to be the classic way – far too little write-downs. As if pooling together the worst cases would create a bank in brilliant health.

In the best tradition of the marriage between finance and politics, the role of a chairman was given to a politician, Rodrigo Rato. Rato had an apparent merit, having been the director of the IMF 2004-2007. Why did he resign after only three years, before the end of his term? Apparently, he wanted more time with his family. Quite often, when people in power resign to be with their families, it’s because no one else wants them but dares not say it aloud. The Spanish press is overflowing with stories about corrupt lending to political pet projects like airports that have yet to see an airplane and exorbitant salaries of cajas managers.

There are also cajas in Iceland, small local saving banks, originally set up to serve individuals and small enterprises in the local community, based on small is beautiful in a closely-knit community where the directors are pillars of society. Last year, PriceWaterhouseCooper did a report on one of these local institutions in Iceland – the local saving society in the village of Keflavik, on the Reykjanes peninsula, right in the shadow of the now defunct US base. This report has now been leaked – and it provides a grotesquely clear image of small-town corruption with no small money.

The methods aren’t new –it doesn’t come as any surprise that there were plenty of loans with no or weak collaterals – but the methods are really crude. The CEO lent and then wrote-off loans to his son, not to mention the bank’s staff, local politicians and entrepreneurs with the odd bank CEO among favoured borrowers. And as with the banks: what were the accountants doing?

Like in the cajas, this is the story of how the vision of community service turned to the vision of greedy self-service.

SpKef has now been thrown under the wings of the state-owned Landsbanki, as if Landsbanki were the best place to keep toxic waste, no questions asked. That said, the Office of the Special Prosecutor is no doubt looking at the SpKef operations. SpKef managers seem sitting ducks for a criminal case of breach of fiduciary duties, comparable to the Byr case. But so far, the Government isn’t asking any questions and yet it is putting ISK25bn, €197m, to fill the empty SpKef coffers in an unexplained bailout (and in Icelandic terms, the bailout amounts to the budget contribution to the University of Iceland for two years).

But how come that banks, costing governments in the UK, the US, in Ireland, Greece, Portugal, little Cyprus and now in Spain the earth and the sky aren’t being properly investigated? Is it too complicated? Of course it isn’t. It’s a question of picking and choosing the right topics – such as breach of fiduciary duty, possibly market manipulation and in the small local banks corrupt lending.

A recent court case, studied by Matt Taibbi in a Rolling Stones article, uncovers how major US banks, over a decade, have used tried and tested Mafia methods to rig bond auctions by public authorities, universities and other institutions. It’s an article that merits reading more than once just to fathom the banks’ dizzying arrogance and pure will to cheat. The defense argued ia that the rigged price was just as fair as any other price. Yes, why bother with free competition when only monopoly is deemed to assure the satisfying gains?

Banks in the US and the EU are all profiting from abnormally low interest rates though they aren’t lending. How ironic: it was the unwillingness to lend that triggered the credit crunch in 2007, thought at the time to be a tiny naughtiness by the banks. In the UK, the subsidy to banks has been estimated to amount to £220bn over the last few years. Now, this seems more like a good plan to get capital.

And in case you haven’t noticed: the banks are still not lending but hoarding money against the losses they seem to suspect are looming out there. Understandable, in the light of the latest, from the WSJ:

Regulators and investors are concerned that some European banks are artificially boosting a key measure of their financial health, a worry that is further eroding market confidence in the Continent’s banks.

Such concerns have been building up for more than a year. But they have intensified lately, with a parade of banks announcing that they intend to increase their capital ratios—a key gauge of their abilities to absorb future losses—partly by tinkering with the way they assess the riskiness of their assets. Spanish banks, including Banco Santander SA, are among those that have announced plans to boost their capital ratios …

Does it come as a surprise that in spite of repeated stress tests, the banks might actually not be showing their true colours? No, it doesn’t. In an unnamed central bank a stress test was recently being discussed. Some innocent soul asked why the test didn’t test more severe and realistic circumstances. There was a troubled silence before someone muttered: “Because then they would all fail.”

In Iceland – an interesting measure because of the thorough overview of the banks, the SIC report – it’s clear that bank auditors have questions to answer. Some will be answered in court: Glitnir and Landsbanki have sued their auditors, PwC, for misrepresenting the health of these banks. The rapid expansion of Kaupthing is worryingly similar to Santander’s growth.

Modern society undoubtedly needs banks – but we need banks that do not just serve themselves but society as a whole. We are still waiting and it’s costing us all a lot. It’s not just a euro crisis but a crisis of Western banking under the long, dark shadows of corrupt business practices.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

The al Thani story behind the Kaupthing indictment (updated)

The Office of the Special Prosecutor is indicting Kaupthing’s CEO Hreidar Mar Sigurdsson and Kaupthing’s chairman Sigurdur Einarsson for a breach of fiduciary duty and market manipulation in giving loans to companies related to the so-called ‘al Thani’ case; indicting Kaupthing Luxembourg manager Magnus Gudmundsson for his participation in these loans and Kaupthing’s second largest shareholder Olafur Olafsson for his participation. In addition, Olafsson faces charges of money laundering because he accepted loans to his companies without adequate guarantees.

In September 2008 Kaupthing made much fanfare of the fact that Sheikh Mohammed bin Khalifa al Thani, a Qatari investor related to the Qatar ruler al Thani, bought 5.1% of Kaupthing’s shares. The 5.1% stake in the bank made al Thani Kaupthing’s third largest shareholder, after Olafsson who owned 9.88%. This number, 5.1%, was crucial, meaning that the investment had to be flagged – and would certainly be noticed. Einarsson, Sigurdsson and Olafsson all appeared in the Icelandic media, underlining that the Qatari investment showed the bank’s strong position and promising outlook.

What these three didn’t tell was that Kaupthing lent the al Thani the money to buy the stake in Kaupthing – a well known pattern, not only in Kaupthing but in the other Icelandic banks as well. A few months later, stories appeared in the Icelandic media indicating that al Thani wasn’t risking his own money. More was told in SIC report – and now the OSP writ tells quite a story. A story the four indicted and their defenders will certainly try to quash.

The story told in the OSP writ is that on Sept. 19 Sigurdsson organised that a loan of $50m was paid into a Kaupthing account belonging to Brooks Trading, a BVI company owned by another BVI company, Mink Trading where al Thani was the beneficial owner. Sigurdsson bypassed the bank’s credit committee and was, according to the bank’s own rules, not allowed to authorise on his own a loan of this size. The loan to Brooks was without guarantees and collaterals. This loan, first due on Sept. 29 but referred to Oct. 14 and then to Nov. 11 2008, has never been repaid. – Gudmundsson’s role was to negotiate and organise the payment to Brooks. According to the charges he should have been aware that Sigurdsson was going beyond his authority by instigating the loan.

But this was only the beginning. The next step, on Sept. 29, was to organise two loans, each to the amount of ISK12.8bn, in total ISK25.6bn (now €157m) to two BVI companies, both with accounts in Kaupthing: Serval Trading, belonging to al Thani and Gerland Assets, belonging to Olafsson. These two loans were then channelled into the account of a Cyprus company, Choice Stay. Its beneficial owners are Olafsson, al Thani and another al Thani, Sheikh Sultan al Thani, said to be an investment advisor to al Thani the Kaupthing investor. From Choice Stay the money went into another Kaupthing account, held by Q Iceland Finance, owned by Q Iceland Holding where al Thani was the beneficial owner. It was Q Iceland Finance that then bought the Kaupthing shares. As with the Brooks loan, none have been repaid.

These loans were without appropriate guarantees and collaterals – except for Serval, which had al Thani’s personal guarantee. After noon Wed. Oct. 8, when Kaupthing had collapsed, the US dollar loan to Brooks was sent express to Iceland where it was converted into kronur at the rate of ISK256 to the dollar (twice the going rate in Iceland that day) and used to repay Serval’s loan to Kaupthing – in order to free the Sheik from his personal guarantee.

This is the scheme, as I understand it from the OSP writ. And all this was happening as banks were practically not lending. There was a severe draught in the international financial system.

The Brooks loan is interesting. It can be seen as an “insurance” for al Thani that no matter what, he would never lose a penny. When things did go sour – the bank collapsed and all the rest of it – this money was used to unburden him of his personal guarantee. Otherwise, it would have been money in his pocket. It’s also interesting that the loan was paid out to Brooks on Sept. 19, his investment was announced on Sept. 22 – but the trade wasn’t settled until Sept. 29. This means that his “guarantee” was secured before he took the first steps to become a Kaupthing investor.

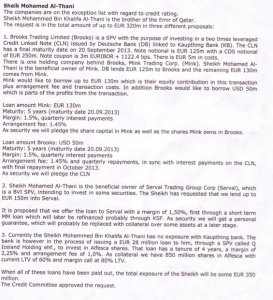

Apparently, Kaupting’s credit committee was in total oblivion of all this. The CC was presented with another version of reality. Below is an excerpt from the minutes regarding the al Thani loan, discussed when the Board of Kaupthing Credit Committee met in London Sept. 24. 2008 (click on the image to enlarge).

Three things to note here: that the $50m loan “is parts of the profits from the transaction.” Second, that al Thani borrowed €28m to invest in Alfesca. It so happens that Alfesca belonged to Olafsson. Al Thani’s acquisition in Alfesca was indeed announced in early summer of 2008 and should, according to rules, have been settled within three months. At the end of Oct. 2008 it was announced that due to the market upheaval in Iceland al Thani was withdrawing his Alfesca investment. Thirdly, it’s interesting to note that Deutsche bank did lend into this scheme – as it also did into another remarkable Kaupthing scheme where the bank lent money to Olafsson and others for CDS trades, to lower the bank’s spread; yet another untold story.

According to the OSP writ, the covenants of the al Thani loans differed from what the CC was told. It’s also interesting to note that the $50m loan to al Thani’s company was paid out on Sept. 19, five days before the CC meeting. This fact doesn’t seem to have been made clear to the CC.

The OSP writ also makes it clear that any eventual profits from the investment would have gone to Choice Stay, owned by Olafsson and the two al Thanis.

Why did al Thani pop up in September 2008? It seems that he was a friend of Olafsson who has is said to have extensive connection in al Thani’s part of world. Olafsson’s Middle East connection are said to go back to the ‘90s when he had to look abroad to finance some of his Icelandic ventures. London is the place to cultivate Middle East connections and that’s also where Olafsson has been living until recently. It is interesting to note that the Financial Times reports on the indictments without mentioning the name of Sheikh al Thani.

The four indicted Icelanders are all living abroad. Sigurdur Einarsson lives in London and it’s not known what he has been doing since Kaupthing collapsed. Hreidar Mar Sigurdsson lives in Luxembourg where he, together with other former Kaupthing managers, runs a company called Consolium. His wife runs a catering company and a hotel in Iceland.

Magnus Gudmundsson also lives in Luxembourg. David Rowland kept him as a manager after buying Kaupthing Luxembourg, now Banque Havilland, but Rowland fired Gudmundsson after Gudmundsson was imprisoned in Iceland for a few days, related to the OSP investigation. In the Icelandic Public Records it’s said that Olafsson lives in the UK but he has now been living in Lausanne for about two years. In Iceland, he has a low profile but is most noted in horse breeding circles, a popular hobby in Iceland. He breeds horses at his Snaefellsnes farm and owns a number of prize-winning horses.

Following the indictment, Olafsson and Sigurdsson have stated that they haven’t done anything wrong and that the al Thani Kaupthing investment was a genuine deal. The case could come up in the District Course in the coming months. But perhaps this isn’t all: it’s likely that there will be further indictment against these four on other questionable issues related to Kaupthing.

*The OSP indictment, in Icelandic.

**Does it matter that the four indicted are all living abroad? When I made an inquiry at the Ministry of Justice in Iceland some time ago whether Icelanders, living abroad but indicted in Iceland, could seek shelter in any country in Europe by refusing to return to Iceland I was told they couldn’t. If an Icelandic citizen is indicted in Iceland and refuses to return, extradition rules will apply. In this case, Iceland would be seeking to have its own citizens extradited and such a request would be met. – It has been noted in Iceland how many of those seen to be involved in the collapse of the banks now live abroad. It can hardly be because they intend to avoid being brought to court – they would have to go farther. Ia it’s more likely they want to avoid unwanted attention. For those with offshore funds it might be easier to access them outside of Iceland rather than in a country fenced off by capital controls.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Splitting apart debt and assets – and the lost sense of honour to pay one’s debt

Sean Quinn, who four years ago was Ireland’s richest man, has been forced into bankruptcy by his largest creditor, Anglo Irish. The man who over the years amassed a debt of €2bn with Anglo Irish now declares that his assets are worth only £50,000.

Similar losses have happened to the Icelandic billionaires. In the summer of 2010 the Glitnir Winding-Up Board sought a freezing order on the assets of Jon Asgeir Johannesson, the bank’s largest debtor. At the trial, Justice Steel was intrigued by the fact that a man who once was said to be worth £600m, who had in the years 2001-2008 a monthly expenditure £280,000-350,000 (!) and also had £11m flowing through his Glitnir account in autumn 2008, as the banks were collapsing, only had a paltry £1,1m worth of asset to show for it. The judge felt that such a substantial expenditure couldn’t but leave behind more substantial assets and confirmed the freezing order.

In the case of Quinn, Anglo is pursuing a case against him in Cyprus, thinking that Quinn and members of his family have conspired to move assets beyond the bank’s reach. Quinn speaks of a “vendetta” against him. Similar complaints have also been heard in Iceland from those pursued by WUBs.

It’s interesting to compare Quinn and other who go bankrupt leaving behind mountains of debt with stories from earlier decades and centuries about people doing everything to pay off their debt because their honour depended on it. Towards the end of the 19th Century, Mark Twain lost money on attempts to develop a new type of a printing machine and the company went bankrupt. Although the debt wasn’t in his name Twain toured Europe for some years, giving lectures to a paying audience and publishing as he could, until he had paid off his debt.

Now a days some of those who got astronomically rich quickly and equally lost their fortune in a short time, are unperturbed to use their meagre assets to hire lawyers to defend themselves from the creditors. It’s as if using all means to avoid paying one’s debt has become the natural thing to do – instead of using all one’s possible means to pay it back.

But before it comes to bankruptcy, there are ways to siphon assets off. This was done in the Iceland – not only in the banks but also in the smaller financial institutions such as the building societies. The basic way is to use a cluster of companies as a centrifuge where, in the course of a few years, debt and asset is split apart: the debt stays in certain companies, the assets migrate elsewhere. When things go badly, the debt-ridden companies go bankrupt, little or nothing is left for the creditors whereas assets, bought with the help of loans, have been spirited away.

There are three basic ways to split apart debt and assets. One is to pay out dividends. Secondly, to buy assets from related parties – at whatever price that suits you – and thirdly, to lend money to related parties, not bothering about collaterals or security of any sort. In all three cases the debt doesn’t disappear but the assets bought are beyond the reach of creditors.

In addition, the Icelandic lenders lent exorbitant amount of money into holding companies such as FL Group, Exista, Samson, Baugur and Milestone, which in turn lent the money on to related parties, paid out dividends or did in other ways split apart debt and assets. By lending money into these holding companies, the companies turned into banks with no risk management.

The three main banks in Iceland all lent to big borrowers who used these methods. But not only the big lenders lent in this way. The building societies lent much smaller amounts to a number of people, often related to the managers or to the board members in such a way that the borrowers could split apart assets and debt.

One example that I have looked as it a cluster of six related companies. Debt was split from assets and debt by paying dividends and by buying assets of doubtful value. After a few years, the debt was in one company that went bankrupt after 2008. No assets were there to speak of. What however troubled the borrowers in this case was that at some point they were obliged to take on a personal guarantee of ISK50m (€310,000) though not much for a debt of more than ISK200m.

During 2007 and 2008, some of the big Icelandic borrowers were forced to accept a personal guarantee since the banks found it increasingly difficult to justify little or no collateral in their accounts. Magnus Thorsteinsson, who together with Bjorgolfur Thor Bjorgolfsson and his father got rich in Russia during the 1990s and bought the newly privatised Landsbanki in 2002, was sued by the Landsbanki WUB in 2010 to enforce a personal guarantee.

During the trial, Thorsteinsson claimed that yes, he had accepted a personal guarantee but only because the Landsbanki managers had promised it would never been enforced. The WUB begged to differ, Thorsteinsson couldn’t pay and went bankrupt in Iceland. He has now returned to St Petersburg where he got rich in the 1990s.

In trials related to his Oscatello pledge, Vincent Tchenguiz – a major client of Kaupthing though dwarfed by his brother Robert – has claimed that Kaupthing never intended to liquidate this collateral. Quinn has spoken of a similar treatment by Anglo: he put up collaterals that the bank had given him verbal assurance would never be liquidated.

A source familiar with large bankruptcy cases says it is quite common that people in these large cases make claim of this type. From a source familiar with Kaupthing it seems though to be the case that, as is so often seen in the Icelandic bank deals, Kaupthing had given its favoured clients reasons to believe that collaterals would not be liquidated.

A prerequisite of splitting apart assets and debt is a willingness on part of the lender to accept weak or no collaterals, to lend into a cluster of companies and to turn a blind eye as to how the loans are used.

Ordinary mortals can’t get loans like these. By these lending practices, the Icelandic financial institutions (and Anglo Irish?) created a two-tier system: on one hand the normal loans with careful scrutiny of lenders; on the other, the abnormal loans for the chosen few who could split apart debt and assets. In the case of the really big lenders, with a vast system of off shore companies, it’s a kid’s play to get the assets well beyond the reach of any WUB – just as Anglo is experiencing in Cyprus, which interestingly has traditional ties to wealthy Russians.

There are many examples of companies amassing enormous debt, then going bankrupt with return to creditors is 1-5%. This is happening with many Icelandic companies. Where did the assets go? It takes a lot of work to trawl through transactions to find the invoices to companies, which have been paid high sums of money for consultancy though there is no employee to carry out the consultancy. Or to find sales contract for worthless assets.

And it doesn’t only take a lot of work: it also takes expertise to recognise the signs. An accidental hiker who sees a trail in the snow, can’t necessarily distinguish between the trail of a rabbit and a hare. The experienced hunter can.

Once money has been channelled out of sight and reach of WUBs and authorities such as tax authorities it isn’t trivial to get the money back into the country of origin, let’s say Ireland or Iceland. One way is through back-to-back loans. A man called Midas has borrowed – or rather been lent money – beyond all rhyme and reason. He has used a part of these loans to buy assets, pay dividend and with time these assets ended up in Panama.

In the end, Midas has to declare himself bankrupt but luckily for Midas his creditors don’t know about the assets in Panama. Midas doesn’t want to pay more of his debt than strictly necessary and he has lawyers working for him to keep the creditors away. How can Midas pay his lawyers when he has no money?

Midas is lucky. His friend Croesus has a company in Cyprus. Midas sends £1m to Croesus’ company. In London, Croesus “lends” £1m to Midas who can then pay his legal team there. To his creditors Midas points at how lucky he is to have such a good friend as Croesus, willing to lend him money. There isn’t much the creditors can do against this sign of pure friendship.

Midas is of the new breed of rich men. Unlike Mark Twain, Midas doesn’t see it as a matter of honour to repay his debt. On the contrary, he sees it as a matter of pride that he was clever enough to channel money off shore before things turned nasty. And clever enough to have such understanding lenders. The question is if the creditors to the financial institutions run by these understanding lenders are equally understanding of the fact that managers have not only lent beyond rhyme and reason but also lent in such a way that the creditors get much less than if the managers had been really tough on collaterals. Isn’t that called a breach of fiduciary duty?

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

‘Samhengi hlutanna’ – the literary side and sense of the Icelandic bank crash

‘Samhengi hlutanna’ (the English title is, so far, Not a Single Word) is my latest novel, published last week. It’s best described as a docu-drama and a financial thriller. It takes place from mid December 2009 till May 2010 in London and Iceland.

Hulda is an Icelandic journalist living in London. She has reported on the Icelandic boom-and-bust and the collapse of the Icelandic banks. When she dies in a bicycle accident her partner, the lawyer-turned-artist Arnar, struggles to hold his life together. A few months later Raggi, an Icelandic journalist and old friend of Hulda, turns up on Arnar’s doorstep. Raggi has decided that with Arnar’s help he is going to finish the book Hulda was working on before she died.

Arnar tries to dissuade him but Raggi, a stubborn Icelander and sober alcoholic, drags him into his scheme. Rambling, they start looking up people that Hulda had talked to, in order to pick up where she left off. One of Hulda’s contacts puts them in touch with Mara, a Hong Kong-based Finnish private investigator. Mara guides them through a maze of intrigues and whole galaxies of off shore companies but she also seems to have her own agenda.

They meet one person after the other who all shed some light on what happened but the bits and pieces don’t add up and no coherent picture emerges. Until, as Mara had predicted, the confusion begins to take shape though Arnar and Raggi find it much more difficult than Mara, specialised in financial fraud, to figure out what really took place.

The Icelandic title can be translated as ‘the context of things’ and that’s what Arnar discovers: a whole new context to what happened in Iceland and eventually to his own family. There is an Icelander who got rich in Russia, bought a bank in Iceland and is now investing in Africa. Another made his money in Latvia.

In the Icelandic context there are company groups stretching from Iceland to Germany, Luxembourg, London, Cyprus and other secrecy jurisdictions where money flows into unnamed bank accounts. Nothing makes much business sense but it all makes sense if the context is money laundering and bribes. And where did the money sloshing around in the collapsed Icelandic banks come from? Not just from Iceland, that’s for sure.

‘Samhengi hlutanna’ has a Facebook page (with comments and links to interviews, reviews etc) – and can be bought in most Icelandic book shops, so far only in Icelandic, and here on-line.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

The price of politeness

Rubbish heaps in Naples and ever-increasing eurozone bail-outs are two sides of the same phenomenon within the EU: unresolved underlying problems

Rubbish heaps in Naples and ever-increasing eurozone bail-outs are two sides of the same phenomenon within the EU: unresolved underlying problems

‘Why are you taking a photo of the rubbish heap?’ A swarthy man, in his early 40s, double chin and flabby belly in a wife-beater, appeared from nowhere. I had just snapped a photo of a rubbish heap ‘lungo mare’ in downtown Naples. I told him that Naples is my favourite city in the world, I’ve been coming there for twenty years and I find it painful to watch the decline of this glorious city with its spirited inhabitants. ‘But why do you want to take a photo of the rubbish?’ ‘Why shouldn’t I?’ I asked. ‘The city is now defined by this disgrace.’

The rubbish heaps in Naples have been in the news for years. It’s a miracle that there hasn’t been an outbreak of some horrific plague from the ominously smelly mounds in the sweltering summer heat. Every now and then, the military steps in to remove the rubbish but it’s only a temporary relief. After years of empty promises from politicians the underlying problem still hasn’t been solved.

The local ‘malavita’, the Camorra, dominates the city’s garbage sector and to them, rubbish is gold. Camorra-related companies ignore proper waste disposal but dump any amount of highly toxic amalgam of industrial waste, rubbish from hospitals and homes on land bought from farmers by making them a Camorra offer: an offer that can’t be refused. Whole regions of Naples upland are now horrendously polluted causing birth defects in children, cancer rate to escalate, poison to enter the food chain and making animals suffer.

The crime-infested rubbish sector isn’t confined to Naples. When a company in Northern Italy accepts an offer to have its rubbish removed for a pittance it knows full well that proper rubbish management costs much more. By saving money it supports the ‘malavita.’ The Neapolitan journalist Roberto Saviano, who has recounted the ghastly rubbish business in his books and numerous articles, is on the Camorra’s death list and lives in hiding.

Every time I visit Italy it strikes me how rich this country must be since it’s able to afford the waste of resources and human capacity that organised crime causes. Organised crime hinders progress because it stifles efficiency and the learning that promotes development. The Italians themselves bear the responsibility for the Italian situation. But sadly, the disgraceful rubbish heaps in Naples are also part of a European problem.

The rubbish sector is one part of the ‘clean’ side of Mafia Ltd. The ‘malavita’ managed to take hold of the rubbish sector via the private-public partnerships, widespread in Italy. This interaction of private and public bodies is a hugely lucrative operation ground for the Italian ‘malavita,’ be it the Camorra in Naples, the Mafia in Sicily or the ‘Ndrangheta in Calabria. Sadly, EU money has floated through these channels and fed organised crime. Incidentally, private public partnerships have also been a fertile ground for corruption in Greece. On the whole, the EU has been far from vigilant when it comes to corruption in the member countries.

In a recent FT article the Italian ex-EU commissioner Mario Monti blamed the euro debacle partly on the EU being too deferential and too polite to its member states. The large and powerful ones within the EU, have time and again prevented monitoring economic development. Greece’s unsustainable debt was hidden under incorrect official figures – and interestingly, Germany and France opposed giving Eurostat powers to conduct proper investigations. (It’s an interesting angle though it doesn’t quite explain the problem of the eurozone. Data on lending to the eurozone countries has at all times been available from Bank for International Settlements.)

Evidence for the same is evident in many other EU countries. The EU has systematically closed its eyes to corruption in Greece. In 2008 Bertie Ahern resigned as a prime minster due to corruption allegation. Amongst other things he had bought a flat for money he couldn’t account for. In Italy, 84 out of 945 MPs, almost 10%, are under investigation for corruption; 49 out of the 84 are members of prime minister’s Silvio Berlusconi’s party. Minister of agriculture in Berlusconi’s government Saverio Romano has been under investigation for eleven years for alleged Mafia connections, going back more than two decades. France had its Elf affaire. – Only corruption in Bulgaria and Romania seems visible enough for the EU to worry the EU.

Monti is right that had the EU been less polite and taken a more critical approach the problems of the eurozone would not have risen. But the EU reflects the individual countries. In all the European countries, and in the US, debt has been extolled and welcomed, both at private and public level and the purveyor of debt, the banks, have been praised to the skies and the architects of debt, the bankers, have been awarded obscene remuneration.

It’s now abundantly clear that there wasn’t a credit crunch but a debt crunch, caused by reckless over-lending by banks who thought they would forever be able to securitise and sell it off. Yet, the European politicians keep on being polite. Polite to the bankers that armed with excel and inspired by greed and badly structured incentives over-lent to Greece, Ireland, Portugal, Spain, Italy and now clearly to Cyprus as well. Belgium could very well be going the same way – and then it’s no longer a crisis in the periphery but right at the heart of Europe.

It’s now four years since the European Central Bank first provided liquidity ‘to permit an orderly functioning of the money market.’ In a statement 14 August 2007 Jean-Claude Trichet president of the ECB said: ‘We are now seeing money market conditions that have gone progressively back to normal… This attitude… will help to consolidate a smooth return to a normal assessment of risks in liquid markets.’ That was wishful thinking – but this same wishful thinking still prevails: that by bailing out the banks everything will be normal.

That key question is ‘what’s normal?’ It’s clearly not returning back to the over-lending of this last decade. And it’s clearly not following the risk assessment of the last decade. Risk was miscalculated and underpriced.

Trichet’s view in August 2007 still guides the action of the ECB and the European Union, expressed in ever more insane amount of money tied up in bailing out the banks that got it all wrong in the first place. In autumn 2008 many politicians gravely warned against socialising the losses and privatising the profits. Yet, this is exactly what’s going on.

In her comment to Monti’s article the economist Megan Greene pointed out the dangers to this route: ‘A new political class will be brought to power by electorates in the core countries that are fed up with contributing to bail-out programmes.’ There will be ample room for demagogues and unsavoury forces to play on voters’ anger and frustration.

Europe is a rich continent. So rich that it’s now inflating the EFSF with €440bn, though €2 trillion is needed to pre-empt a meltdown in Italy and Spain. The second Greek rescue packet of €160bn, added to the €110bn last year, will only tide Greece over for a limited period.

So far, the ECB and EU politicians have pretended there is only one way of resolving the problem: by letting the tax payers pay. When will the European Union and the ECB drop the politeness and say bluntly to the banks: ‘Your calculations were wrong, you over-lent and as you know, in the financial sector rectifying this kind of mistake is called a write-down. In this case the mistake was huge. Alors, the write-down has to reflect the size of the mistake.’ Any other solution will be like the rubbish heaps in the centre of Naples: they are removed but new heaps grow because the underlying problem hasn’t been resolved.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

The complicated life of David Rowland

David Rowland, who will be the Conservative Party’s treasurer come October, has had a colourful live with some dirty spots here and there – or that’s at least what the Daily Mail has dug up. Rowland bought Kaupthing Luxembourg, turned it into Banque Havilland with his son Jonathan now as its CEO after Magnus Gudmundsson who used to run Kaupthing Luxembourg and was retained by the Rowlands was remanded in custody because of an ongoing Icelandic investigation of Kaupthing. Havilland is the administrator of the failed bank, through Pillar Securitisation.

It was through Kaupthing Luxembourg that Kaupthing, under Gudmundson, ran its most shady deals – and from there the web trails to offshore havens such as Panama, Cyprus and most notably the BVI. Recently, authorities in Luxembourg searched the premisses of Havilland on behalf of the Office of the Special Prosecutor in Iceland, to aid investigations unrelated to the present Banque Havilland.

It’s interesting to note, however, that there are still some Icelandic clients at Havilland. Gaumur, a company owned by Jon Asgeir Johannesson and his family, has a Luxembourg subsidiary registered with Havilland with three BVI companies, previously owned by Kaupthing, registered as Gaumur S.A.’s directors so no changes there in that respect.

Daily Mail notes that Rowland once said that money makes your life complicated and the more money the more complicated life becomes. Now that Rowland will be taking up a position with the Tories he’s bound to be heavily scrutinised by the press and that might in turn make his life more complicated.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Where are they now?

‘Iceland was bankrupted by twenty or thirty men.’ That’s how Vilhjalmur Bjarnason lecturer at the University of Iceland and a vocal commentator on finance and business put it a few months after the collapse of the banks in October 2008. At first, many felt that Bjarnason was overstating his case but time – and most clearly the report of the Althingi Investigative Commission – has shown that it did indeed only take ca thirty people (almost all male) to bankrupt Iceland.

Most Icelanders will be able to list these thirty odd names. These are the bank managers, the banks’ chairmen and the banks’ principal shareholders. The understanding is that the Office of the Special Prosecutor will in due course most likely bring criminal charges against these people. The banks’ resolution and winding-up committees are already bringing charges or planning charges against these people to claw back the money extracted from the banks by illegal means.

All these people were extremely prominent and visible in Iceland in the years up to October 2008. They sponsored art, culture, sport and charities and appeared frequently in the media. Some of them gave interviews in the weeks and months after the collapse but as more light was thrown on the operations of the banks and their shareholders they have become increasingly silent. After the report, little is heard from them – there isn’t much to say now that the report has spelled it out so clearly what went on, including verbatim sources such as emails. Some of this material contains phrases that everyone in Iceland now knows by heart such as ‘Thank you, more than enough:-)’ – the succinct answer from Magnus Gudmundsson director of Kaupthing Luxembourg when Kaupthing’s executive chairman informed him, in equally few words, that his bonus for 2007 would be €1m.

From being feted and admired these people are now generally despised in Iceland. There are stories of theatregoers unwilling to stand up to let them to their seats at the theatre, guests at restaurants driving them out, passengers accosting them as they waited for their luggage at Keflavik airport. There are even stories that they have been hit or spat on, on the streets. People threw snowballs at Jon Asgeir Johannesson when he left his wife’s hotel in Reykjavik during the winter following the collapse of the banks.

No wonder that many of them prefer to live abroad. There have been rumours lately that some of them might want to move to Luxembourg but sources close to a well known Luxembourg bank claim that some of the more famous names have already been turned down as clients. And in order to properly settle down in Luxembourg one has to register with the police. People then do have to declare if they have an earlier conviction or if they are under investigation – not a trivial question for some of the Icelanders who might be considering to move to Luxembourg.

For most of these people the yachts and private jets are gone. Some are bankrupt other still hold on to some assets though more might be lost later on. In Iceland, many speculate if and then how much these people have stacked away on in offshore save havens. But where are they now, the bankers and the Viking raiders?

Kaupthing

When Sigurdur Einarsson ex-executive chairman of Kaupthing was summoned to Iceland in May to be interviewed by the OSP in Iceland he refused to go to Iceland since he didn’t want to risk following three Kaupthing ex-top executives into custody. He probably didn’t expect that he would end up on Interpol’s wanted list – but that’s where he’s now. Einarsson isn’t known to have been involved in any business after the collapse of the bank and has been living in London since 2005. According to the AIC report Kaupthing lent Einarsson the £10m needed to buy his house in Chelsea – and then Einarsson rented his house to the bank so he could live in the house, apparently an exceedingly smart way of living for free as the rent paid or didn’t pay off the mortgage.

Kaupthing’s CEO Hreidar Mar Sigurdsson moved to Luxembourg last year to run Consolium, a consultancy staffed by several ex-Kaupthing managers. Sigurdsson was held in custody for ten days in May as the OSP picked through his testimony and some of his colleagues’. Sigurdsson is now back in Luxembourg.

Magnus Gudmundsson was the director of Kaupthing Luxembourg where some think that Kaupthing’s darkest secrets, if there are any, were kept. When David and Jonathan Rowland, father and son, took over Kaupthing Luxembourg last year and turned the good bank into Banque Havilland and put the bad assets into Pillar Securitisation that Havilland administrates, they retained Gudmundsson as a director, much to the surprise of those who thought that the new owners wanted to start with a clean slate and a new business. When however the OSP put Gudmundsson into custody the Rowlands dropped him like a hot potato. Consolium had business ties with Havilland and Pillar and according to my sources these ties are still in place.

Olafur Olafsson has a longer business record than most of the other high-flying Icelandic bankers and businessmen since he’s older than most of them. He grew up when political ties were essential and his fortune was tied to the Progressive Party and the co-op movement, part of the Progressive sphere of influence. From Kaupthing’s first ventures during the late 90s he was close to them, underlining that bank’s connection to this party.

The softly spoken cultivated Olafsson wasn’t much seen in Iceland during the noughties but he had and still has a charity there. He used to have an office in Knightsbridge and lived close by. Last year he moved to Lausanne. According to a Swiss source he lives modestly. The SIC report is full of juicy stories of Olafsson – there’s his connection to the Qatari investor al Thani who seemed to have the greatest trust and belief in Olafsson’s two main undertakings in Iceland, Alfesca and Kaupthing. But according to the report there was less trust and more loans from Kaupthing. Through Kjalar Olafsson owned 10% in Kauphting but still holds on to companies in Iceland, most notably the shipping company Samskip. The Kaupthing loan overview from end of September 2008 indicates that Olafsson’s personal loans from Kaupthing Luxembourg were €49m.

Until shortly before the collapse of Kaupthing brothers Lydur and Agust Gudmundsson, the bank’s biggest shareholders, were seen as being of a different breed from Viking raiders such as Jon Asgeir Johannesson and Thor Bjorgulfsson. The brothers started in fish manufacturing during the 90s, seemed to have built their wealth up out of concrete things and not only financial acrobatics. But the report throws a different light on their activities, their close if not incestuous connections with Kaupthing and equally close ties to many of the bulging Icelandic pension funds. Robert Tchenguiz sat on the board of Exista.

Lydur owns a beautiful house in Reykjvik where he hasn’t been much seen lately and a grand house on Cadogan Place that Pillar now wants to take over due to unpaid mortage of £12,8m. It seems that Agust might suffer the same fate – Pillar isn’t showing any mercy and according to the loan overview Agust had a mortage of €9m with Kaupthing Luxembourg. As Olafsson the brothers still hold on to companies in Iceland, most notably the investment company Exista and the food company Bakkvor UK – but the final outcome is still unclear.

Landsbanki

Father and son, Bjorgolfur Gudmundsson and Thor Bjorgolfsson, shot to fame in Iceland when they managed to set up a brewery in St Petersburg in the 90s. The story of that venture is most fully told in a front-page article in Euromoney November 2002, ‘Is this man fit to be at the helm (of Landsbanki)?’ and in documents on Wikileaks: the short version is that father and son were working for two investors running a bottling plant in St Petersburg in the early 90s. One day in 1995 the investors found out they no longer owned the bottling plant though they couldn’t remember ever having sold the plant father and son and their co-worker Magnus Thorsteinsson. The venture took off and the St Petersburg power elite, i.a. Vladimir Putin, was friendly. Deutsche Bank started financing other Bjorgolfsson’s ventures in Easter Europe in the late 90s. When the trio sold the brewery to Heineken in 2002 they had the money to buy 40% of Landsbanki, then already partly privatised.

The distinguished-looking Gudmundsson is now bankrupt, having not only lost his share of Landsbanki but also his ultimate trophy asset West Ham and lives in Iceland. His son, with the body of a body builder and the square jaws to go with it, still lives in Holland Park though there might be fewer vintage cars in the garage now. It’s not clear if he still owns his country house in Oxfordshire but he is holding on to Novator, his investment company with ties to Luxembourg, the Cayman, Cyprus and other offshore havens. The fate of his biggest asset, Actavis, depends on what Deutsche Bank intends to do about the loan against Actavis, said to the single biggest loan on DB’s loanbook. The question is if DB turns the debt into equity, practically taking Actavis over, or if Bjorgolfsson manages to turn things to his benefit. Thorsteinsson was declared bankrupt in Iceland last year, used to have a large country estate in the UK but is now said to live where it all started, St Petersburg.

Landsbanki had two CEOs, Sigurjon Arnason and Halldor Kristjansson. Kristjansson was a civil servant before becoming the CEO of Landsbanki as it was being privatised. Arnason was the CEO of Bunadarbanki but when Kaupthing bought the bank he and a whole team from Bunadarbanki defected over to Landsbanki. Kristjansson kept the quiet demeanour of a civil servant, Arnason was the aggressive banker known to empty bowls of chocolate is within his reach. It’s interesting to note that Kristjansson kept his post after the privatisation, possibly underlining that the change wasn’t as fundamental as one might have thought – the political ties were still important. Kristjansson now lives in Canada, working for a financial company. Arnason lives in Iceland and is, as far as is known, not involved in any business.

Glitnir

While Landsbanki and Kaupthing were involved with high-flyers abroad Islandsbanki, later Glitnir, seemed more down-to-earth expanding in Norway. Bjarni Armannsson ran the bank with experience from the investment bank FBA in the late 90s. The AIC report shows that Armannsson was very deft at trading for his own companies along running the bank leading the report to advice clearer regulation of CEO’s personal dealings. Armannsson left the bank when Jon Asgeir Johannesson and the FL Group gang became the bank’s largest shareholder in early 2007. He moved to Norway for a while but has recently returned to Iceland and runs his own business there.

Earlier on, two brothers were among Glitnir’s major shareholder, Karl and Steingrimur Wernersson. Their father was a wealthy pharmacist and they, mainly Karl, built on that wealth which mushroomed into companies at home and abroad under their investment fund Milestone. Milestone bought into the Swedish financial sector, bought a bank in Macedonia and an Icelandic insurance company, Sjova, in Iceland. The crudeness and excesses of it all, i.a. a villa in Italy and a vinyard in Macedonia, have been masterly documented by the daily DV in Iceland. Milestone is bankrupt and the brothers are no longer on speaking terms as Steingrimur, who now lives in North London, has accused his brother of bullying him into business ventures. Karl lives in Iceland and spends most of his time on his farm in Southern Iceland where he tames and breeds horses.

The group that came to power and ownership in Glitnir was headed by Jon Asgeir Johannesson, famous his UK retail partners such as Sir Philip Green, Tom Hunter, Kevin Stanford and Don McCarthy. Johannesson started his business ventures by opening a supermarket with his father Johannes Jonsson who now lives in Akureyri. Jonsson is still involved in business though there a now more debts than assets to care for.

Johannesson has for years invested together with a small group of Icelandic businessmen, most notably Palmi Haraldsson, Magnus Armann and his wife Ingibjorg Palmadottir, herself the daughter of the man who built up the biggest retail empire until Johannesson arrived on the scene, bought the empire and later got the princess as well. These shareholders brought in a new CEO, Larus Welding who ran the bank for just over a year. Welding now lives in Northern London and doesn’t seem to be involved in banking anymore. Johannesson still owns the biggest private media company in Iceland. His ownership is the source of some speculation in Iceland since Baugur, also Baugur UK, and so many other investments of his have failed.

On the sideline in this group but for a while extremely powerful was Hannes Smarason, much admired as the McKinsey man who turned biotech to gold at deCode and later built up the investment fund FL Group that outshone everyone in excesses and, in the end, losses. Smarason lives in Notthing Hill, London and documents at Companies House show a string of failed business ventures of his.

The connection between Johannesson, Armann and Haraldsson goes roughly a decade back and though his Icelandic partners were less famous than some of his UK partners they stayed with him. Now they all and Palmadottir are charged by the Glitnir Winding Up Committee that wants $2bn dollars back. Haraldsson has two major investment companies, one is bankrupt the other is in operation and he still owns Iceland Express. Haraldsson has been living in Iceland but has a flat in Chelsea, London.

Johannesson allegedly lives with his wife in Surrey on the same road as Armann, yet again underlining not only the closeness of these two but also the Icelandic tendency to stay with one’s own countrymen. A clan mentality that also characterised the now failed Icelandic banks and businesses.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.