Archive for April, 2010

The principal clients = principal owners

The striking characteristic of the Icelandic banks is that though they were listed companies the banks were run like the private coffers of the principal shareholders. As Sigridur Benediktsdottir, one of the three members of the Investigative Commission, pointed out this morning, shareholders get dividends on the basis of profit. The operation changes fundamentally when people increase their dividends by lending money to themselves – by lending as much as possible the dividend is increased as much as possible. This happened in the Icelandic banks. Clearly, the principal owners completely ignored the interests of small investors.

The Commission concludes that the banks failed because of their rapid growth. In seven years the banks grew 20-fold – growth that was due to poor underwriting, making solvency-related difficulties very likely. The quality of the Icelandic banks loan portfolios eroded successively during this time. One of the Icelandic ways of banking was lending to holding companies with poor assets, often shares in the banks, or even no assets.

After sifting through the banks‘ exposure the Commission concludes that all the banks had an abnormally easy access to loans in these banks, apparently in their capacity as owners. The banks‘ largest clients were the banks‘ principal owners. Was this lending done at arm‘s length? That doesn‘t seem to have been the case. The banks defined ‘related parties‘ in an abnormal way thereby giving a misleading picture of the exposures to the major shareholders.

The abnormal relationship to the principal owners is also clear when it comes to the money market funds: their prime investments included securities and deposits connected to the banks‘ largest owners.

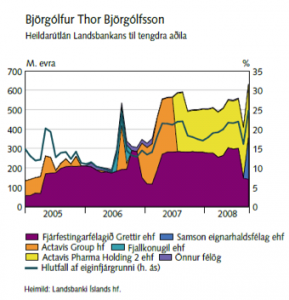

In order to demonstrate the principal shareholders‘s stronghold on the banks two graphs tell a striking story. The graph below shows Landsbanki‘s lending to Bjorgolfur Thor Bjorgolfsson, one of the bank‘s two major shareholders (the other one was his father, with equally gargantuan exposures). Bjorgulfsson also had large exposures in the other two banks. Landsbanki was the bank responsible for the infamous IceSave. In the report, Arni Matthiessen at the time minister of finance claims that all the leading bankers lied to the government just before the collapse – but the worst of the lot, says the minister, was Bjorgolfsson.

(In m of euros; the names above refer to companies owned by BTB).

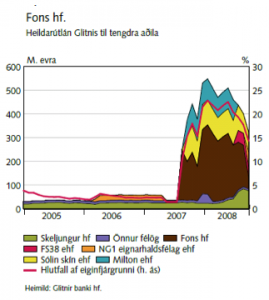

Another equally striking graph shows Glitnir‘s lending to Fons, a holding company owned by Palmi Haraldsson and a constant companion to Baugur, owned by Jon Asgeir Johannesson. What happened in 2007? Fons and Baugur became the principal shareholders of Glitnir – and Glitnir‘s lending to Fons shot up dramatically. Fons was also a large borrower in the other two banks.

(In m of euros; the names above refer to companies owned by Fons).

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

The report: a few highlights from the press conference re public governance

Pall Hreinsson outlined the shortcomings within the government, the Central Bank and the regulators. It’s a tale of staggering lack of coordinated action and share bewilderment. There was a so called ‘coordination group’ but this group didn’t take their task very seriously.

At one point in spring 2008 the government thought that the Central Bank should ‘do something’ – but the Central Bank thought it was up to the government to lead that ‘something’. Not surprisingly, nothing was done. And that’s more or less how things continued.

When the banks failed there was no plan in place how to proceed. However, no matter what, in 2008 the banks were beyond salvation. The necessary measures should have been taken much earlier.

Bank of England was contacted in early spring of 2008. The Icelandic Central Bank wanted to make currency swaps but got a plain ‘no’. However, in a letter Mervyn King offered assistance in terms of advice. His letter wasn’t answered. Instead, Icelandic politicians, like the bankers, continued to claim that Iceland’s problem was a lack of understanding in international markets. The problem was a problem of image.

Leading ministers – the prime minister, minister of finance and minister of trade and bankin – failed in their office. The director of the Icelandic Financial Services, FME, and the three directors of the Central Bank also failed to carry out his duties. It will now be up the Althingi, in case of the ministers, and courts if those mentioned will be brought to court for their failures.

Vilhjalmur Arnason, from the Commission’s Ethical committee, is now pointing out the destructive influence of political appointments of civil servants. That fact that David Oddsson governor of the Central Bank had been a politician had a particularly bad influence of the bank’s trust.

Criticism from abroad was always branded as ‘evil’, a sign of ‘jealousy’ instead of taking it seriously. Banks and wealthy individuals made donations to the political party – no doubt an unhealthy effect on critical thought towards these same individuals and banks within the political parties.

Last but not least: by travelling the world and extolling the Icelandic financial geniuses the president of Iceland didn’t portray the nation in a sensible way as the so called Icelandic success made the standing of the banks in Iceland far too great.

Salvor Nordal, also from the Ethical committee, pointed out the ingrained lack of respect for law and order in Iceland.

Sigridur Benediktsdottir gave a fascinating insight into the banks – will deal with that later…

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

The report – a complete insight

After quickly glancing through the report it is clear that it, i.a., gives a thorough overview of the operations of the three Icelandic banks. Their relationship with their largest clients and major shareholders, numbers and all.

Pall Hreinsson is now telling the press that the Commission points out areas where fraud could be found.

In short: whatever its shortcomings will be, at closer inspection the report is dynamite!

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Iceland holds its breath – report Monday

‘Happy festivity’ – ‘gleðilega hátíð’ – one of my colleagues at the radio said as he walked in earlier this morning. His greeting gives a sense of the spirit in Iceland. Even the weather is completely still, not a straw moving, after gales and rain yesterday. Here at Ruv, the Icelandic State Broadcaster, there is tremendous excitement in the air.

Driving through Reykjavik around 7.30 local time (GMT) I could sense the country holding its breath. Yesterday, at a café in Reykjavik a couple and two men all in their forties on the table next to me were discussing the report. They weren’t sure they would read the whole thing but they were going to follow transmissions during the day and have a look at the website. Last night, visiting relatives, we spent most of the evening talking about the situation in Iceland and what we expect from the report.

Yesterday, I talked to the director of a large public institution. At his work place the television will be running in the canteen the whole day. People can gather there to watch the press conference later on and then interviews and reporting. Those who want to read the report during the day can do so. The same is the case all over the country. At the City Theatre, Borgarleikhusid, actors will start reading as soon as the report is published.

Early this morning the Investigative Commission meets the Althingi’s presidium and the MPs get their copies of the report – over 2000 pages in 9 volumes – you need roughly 40cm in your bookshelves to house it. The press conference is due to start at 10 and at 10.40 the report should be available on-line. The on-line version, with additions not in the printed version, will first be available on the Commission’s website but will then be put on the Ruv website and do doubt other websites as well.

In addition to the on-line version the report has been printed in 6000 copies that are now being driven to bookshops, with great care being taken that no one takes an untimely peep. These copies are now sold out, have all been pre-ordered. Consequently, 2,4 km of bookshelves will be filled today all over Iceland.

I’ve just realised that I’ll need a pass to get into the press conference so I better go and see the lady here at Ruv who is in charge of these precious things. She’s expecting me so I better run.

‘With all this excitement I hope there’s something in the report!’ a technician said just now as he greeted me. I’m pretty sure there’s a lot to take in – it will take some time to digest. Whatever its content, the report is the first deep-ploughing report in any country on the crises. Just that is a feat in itself. Now that a lot of things will be clarified the hope is that some of this past can be laid behind – though justice will need to be done in those cases where individuals have allegedly broken the law.

PS Re justice – the Investigative Commission met yesterday with a special prosecutor, from the Office of the Special Prosecutor set up to deal with cases related to the collapse of the banks. The purpose of the meeting was to inform him on issues and areas where the Commission thinks there might be grounds for further investigation.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

A modern amorality tale – or how to wipe out a ISK6bn debt

How can a bank break all rules to lend ISK6bn, £30m, to a shelf company without any assets – and buy back this company, debt and all, for 1 krona? This might seem to run counter to both business sense and common sense – but welcome to the Icelandic way of banking.

This tale, not a fairy tale but a bank tale, rotates around Fons, a now bankrupt company owned by Palmi Haraldsson and closely connected to Baugur, the now bankrupt company of Jon Asgeir Johannesson. In early 2008 Fons’ debt to Glitnir was so ominous that Glitnir could hardly avoid making margin calls. Johannesson and Haraldsson then rather insistently presented a plan to Glitnir: the bank agrees to finance a deal between two Fons’ subsidiaries that triggers a loan of ISK6bn whereby Fons’ debt of ISK4bn is paid and ISK2bn in cash is released to Fons out of which ISK1bn goes into Johanesson’s private current account.

This is the apparent structure behind charges brought recently by Glitnir’s resolution committee against Jon Asgeir Johannesson who built up the Baugur empire in Iceland, the UK, Denmark and elsewhere, Palmi Haraldsson the present owner of Iceland Express as well as a string of failed companies and a frequent business partner of Johannesson, Larus Welding former CEO of Glitnir, brought in when Johannesson and Haraldsson became the bank’s major shareholders in 2007 and three employees of the bank who, after Glitnir’s collapse, have continued to work at Islandsbanki, the new Glitnir. All six claim innocence. The case will open in late April. The charges clarify news that has been brewing in the Icelandic media over the last few weeks, complete with excerpts from emails of the personae dramatis.

The loan was structured around the sale of a Fons subsidiary to another subsidiary of Fons’ share in Aurum, the holding company of Goldsmiths, a UK jewelry chain, where Baugur and Fons were major shareholders. Glitnir valued the shares at no more than ISK1,5bn but in emails Johannesson and Haraldsson insist on a loan of ISK6bn against the shares. In an email to the bank Johannesson ‘expects’ his plan to be carried out. Welding ordered his employees to ‘prepare a loan agreement’ according to the plan outlined by the two businessmen.

Out of the 6bn 4bn were used to pay up older loans – and 2bn in cash put into Fons’ account. Fons sends 1bn to Kaupthing Luxembourg, allegedly to settle a loan there. Johannesson claims a billion for himself. In an email Johannesson explains that he absolutely doesn’t want to be overdrawn since that doesn’t look good – accordingly, the bank settles the overdraft and puts 750m in ready money into Johannesson’s account. Fixing the overdraft and providing cash of the bank’s major shareholder seems to be enough for the bank to give a helping hand.

According to the charges the only motive for the loan is to the help an already insolvent Fons from Glitnir’s inescapable claims, to dump Baugur’s and Fons’ obligations into an empty shelf company and to provide the two businessmen with cash without any collaterals or obligations. According to the charges all three motives were perfectly clear to the bank.

In an email written as the loan was in the making, a Glitnir employee points out to Welding that he can’t understand why Glitnir needs to go to this length of setting up the Aurum sale – it would have been a lot simpler just to send 2bn directly into Fons’ account in the Cayman Islands.

The emails quoted in the charges give an interesting insight into the minds of the two businessmen and the bankers ordered to prepare the loan. In an email at the end of May Johannesson explains how the loan should be structured, adding that if these requirements won’t be met ‘I should perhaps consider becoming an executive chairman of Glitnir.’ – This has been widely understood as a threat. After the charges became public Johannesson claimed that by deleting a smiley after this sentence the resolution committee had changed its meaning. Apparently, a smiley is no laughing matter to the businessman.

Smiley or not: only three weeks later, this was a threat without any claws. June 5 2008 the Icelandic High Court confirmed an earlier verdict over Johannesson by the Reykjavik County Court Johannesson of three months conditional prison sentence – thereby excluding Johannesson from sitting on any company boards for the next many years.

But there is a further twist to this tale. As the loan agreement was finally in place in July 2008 and FS38, the shelf company, saddled with the loan Fons did a call option with Glitnir obliging the bank to buy FS38 for 1 krona in December 2008 if FS38 so wished. In December, Fons made use of its option and Glitnir, by then taken over by the resolution committee, was forced to buy back its own glorious 6bn debt structure for the agreed 1 krona. In April 2009 Fons went bankrupt. One of Glitnir’s credit claims in Fons is the 6bn loan that then gave rise to the present charges.

According to the charges, Johannesson and Haraldsson were the instigators who commanded the four bankers to fix the loan that was only a make-believe deal, made to provide the two businessmen with 2bn in cash. The businessmen are charged with violations of company law. The bankers are charged with breaking the bank’s internal rules and violating company law.

Bankrupt companies related to Baugur and Fons now come by the dozen and their combined debt amounts to hundreds of billions of kronas that will never be paid. Each of the three Icelandic banks lent tens of billions, in some cases hundreds of billions, to these companies. Around 2000, Kaupthing was instrumental in the making of Baugur as the company started expanding abroad. Landsbanki later lent Baugur astronomical amounts, even when Kaupthing appears to have become more reticent. Baugur and Fons had already done pretty well for themselves when these two became the principal shareholders in Glitnir in summer 2007.

As the credit crunch was slowly crushing the Icelandic banks in the summer of 2008, Glitnir decided on the loan and the call option of 1 krona with the foreseeable final loss shouldered by the bank. The loan of 6bn is not only an offense to all business ethics and to common sense but also runs contrary to good business practice.

It’s an intriguing question why all the three major Icelandic banks went down the same path of lending only a handful of people exorbitant amounts of money on such shaky premises – in deals that time and again run against the interests of the banks, all listed companies.

The Italians have a great expertise when it comes to organised crime – and one of their lessons is that crime propagates in a vacuum beyond the state. The charges against the six haven’t yet been resolved in court – and as long as it hasn’t happened the six are innocent – but these charges and other cases seem to indicate that there was a lawless vacuum in the banks. Hopefully, the report of the Investigative Commission, coming out tomorrow will clarify these issues.

It’s deals like these that have left the Icelanders somewhat perplexed as to what kind of bank system was actually run in Iceland. At the root of this modern amorality tale are bankers prepared to break every rule in the book and major shareholders pulling the strings.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

‘The Investigative Report’ – the play

Next Monday, ‘the report day’, the City Theatre, Borgarleikhusid, known for fabulous productions of classics such as Chekov and Shakespeare (now showing i.a. ‘Faust’ with music by Nick Cave written for Borgarleikhusid’s production), will bring to the stage its hitherto most unique production: the long awaited report of the Investigative Commission.

On ‘report day’, as soon as the report is published, actors will start reading it aloud continuing till the last word is read. It will take theatre’s 45 actors approximately 3-5 days to read the ca 2000 pages. The reading will be divided into shifts of 2-4 hours where two actors take turn reading the text.

During the reading time, day and night, the theatre will remain open and free for all. Those who can’t come can follow the reading via webcast on Borgarleikhusid’s website. According to the theatre’s press release the idea is to create a kind of sanctuary where people can drop in, listen and reflect on the report’s ‘topics, its content and the causes’ of the collapse of the three Icelandic banks in October 2008.

With this public reading Borgarleikhusid is underlining the importance of the report, impatiently awaited by the whole nation and possibly the most important Icelandic event for decades. The report won’t be dramatised – the drama is the text itself – but the theatre’s aim is participating in the national conversation that the report will no doubt create. Borgarleikhusid has already staged two plays reflecting the collapse of the banks one of which will be performed at the theatre-festival in Wiesbaden.

Icelanders are great at turning things into events – I’m sure that next week will be a special week in Iceland. Icelanders will no doubt mark the publication of the report in many ways though Borgarleikhusid’s event might easily be the most spectacular one.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Will the April 12 report only be a whitewash?

‘No’, is my short answer to the question above echoing all around Iceland. I am confident that the report of the Investigative Commission, set up at the behest of Althingi, the Icelandic parliament, will answer many of the questions that have been in the air since the collapse of the three main Icelandic banks in October 2008. And I’m sure it will also answer questions that no one has thought of asking. We just have to keep in mind that the Commission’s remit is to clarify the collapse – i.a. why the banks collapse, how they operated and the role of the regulators, the politicians and the media – it’s not a criminal investigation.

The report has taken much longer than foreseen. It was supposed to come out on November 1, less than a year after it set to work. This was undoubtedly far too optimistic to begin with but not until well into October did the Commission announce up to three months’ delay. Late January the publication was again postponed, no date give – until finally that Monday April 12 has now been set as the date of publication.

The delay has given rise to all sorts of conspiracy theory. One of the more persisting ones is that the report was finished already in January but has since been purged of ‘compromising’ material. I don’t for a second believe that this has been the case. Everyone who has ever written something that involves a large amount of information from various sources knows that editing is a time-consuming process. In addition, extensive parts though not the whole report have been translated into English.

When the text was more or less finished leading politicians and high-ranking civil servants, in all twelve persons, were allowed to read and control what was written about them and to counter or clarify the report’s account, with documentation if they wished. Out of this came allegedly 500 pages of material that the Commission then had to review. Except for eventual errors it’s unlikely that the Commission has changed its text much during this review. If those twelve wish their views to be known their riposte is published as an appendix.

So far, the only known fact is that the report will be published on Monday April 12 but the programme for that day is still unknown. Monday April 12 will be the first day that Althingi gathers after the Easter recess, with a meeting scheduled at 3pm. It’s always been understood that Althingi and the general public will receive the report at the same time, i.e. that the web version will be released as soon as the Althingi is presented with the printed version (which will be sold in books shops for ISK6.000, £30, the price of a hardback though the report, running to more than 2000 pages, is a tad longer than a normal hardback).

However, since the Althingi’s Presidium (consisting of MPs from all the parties in Althingi) appointed the Commission it seems logical that the Presidium will first be presented with the report – then they can answer the questions that undoubtedly will arise once the rest of us can read the report. My guess – and it’s only a guess – is that the Commission will meet with the Presidium early in the day, followed by a press conference as the text will be released on the internet.

In a comment on Icelog, Tony Shearer, CEO of Singer & Friedlander at the time Kaupthing bought it, points out that the Icelandic report emphasises ‘the fact that the UK Government is not doing so, and has steadfastly refused to do so. The reasons are simply that the current UK Government and Prime Minister have no desire for one to be published as it would inevitably place the main causes of the failures of the British Banks at the doors of Gordon Brown, Ed Balls and Tony Blair, the three politicians who, at that time, were responsible for the UK economy. Their failures lead to the collapse of the UK banks, but also were heavily instrumental in the collapse of the Icelandic banks of Kaupthing and Landsbanki. Hopefully the Icelandic report will be direct and clear as to where the blames truly lies. If so, it will be a tribute to Icelanders. It will also show how the Icelandic political system is strong enough to force such a report, and the UK one so weak that people in power are not held accountable.’

Telling the truth is a sign of strength. Of course, banks such as Royal Bank of Scotland, Lloyds and the three Irish banks, Anglo Irish, Allied Irish and Bank of Ireland where the state now is a major shareholder, should be scrutinised. It’s not enough just to bring Anglo Irish’s chairman to court. The Irish need to know what happened – and the same counts for the UK: the British need to know why the British government was forced to become a bank owner.

But there is more in store regarding the banks. Glitnir’s resolution committee has hired Kroll to scrutinise Glitnir’s operations. When finished, this report will be published, possibly later in spring or early summer. I’ve already heard that the report is a riveting read. The resolution committees of both Kaupthing and Landsbanki have had forensic teams doing similar work. Hopefully, their reports will also be published.

As to possible criminal acts within the banks that’s for the Special prosecutor to work on. Another story of delays – the first charges were expected at the beginning of this year – but now it seems as if they might appear before the end of April. Again, it takes time to chase information through the tangled web of companies stretching from Iceland, Cyprus and Panama, to name but a few off shore jurisdictions used by Icelandic businessmen and their bankers.

The Commission’s report will hopefully tell the story of the Icelandic financial system in a clear and concise way. But it might also give us a different story from the one mostly expected. One thing that’s been repeated over and over again for the last months is that the Icelandic FSA, FME, was a cheerleader for the banks instead of keeping them on a short leash. Clearly the FME was no better than regulators in so many other countries but recently, I spoke to someone who has read the minutes of the board at one of the banks: the minutes show clearly that the FME did indeed try to enforce rules and regulations on the bank – but the bank spent a lot of time and man power to figure out how best to evade the rule.

The fact that the UK FSE, as late as February 2008, allowed Kaupthing to set up a high- interest internet account, not to mention Landsbanki and the Icesave, indicates that the FSE also has some things to clarify – but so far, only silence. No matter how dismal the story in the April 12 report will be the relief is that knowing is better than not knowing.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.