Archive for April, 2011

Landsbanki: derivatives contract is valid

Yesterday, the Icelandic Supreme Court ruled in a Gift, an investment company, vs Landsbanki. In August 2008 Gift made a three months derivative contract with Landsbanki, related to the bank’s share. Three months later the bank was gone, Gift had lost and refused to pay the ISK900m, now €5,5m.

Landsbanki brought Gift to court. The ruling is that the contract is valid and Gift has to pay. Further, the court points out that Gift, being an investment company, it is a sophisticated player in the market and can’t hide behind ignorance of the realities of the contract.

This ruling will have a huge effect since many similar contracts are nesting in the old banks. Those who might be hit by it are basically all the major holding companies that operated in Iceland before the collapse. The ruling will most likely affect the fortunes of investors like Exista and Olafur Olafsson.

Here is the ruling, in Icelandic.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Icesave and emotions

After a clear majority for a ‘yes’ to Icesave III in earlier polls it now seems that the ‘no’ vote is gaining ground. This has been happening as reasoned debate lost ground and emotions took over.

Having followed the referenda in Denmark, Norway, Sweden and Finland in the 90s, on Maastricht in Denmark and on EU membership in the three other countries, the course of the Icesave debate follows a familiar pattern. As always happens, there are other issues at play, such as opposition to an unpopular Government and unpopular banks. Many voters will feel that by saying ‘no’ they can say ‘no’ to various things – whereas the question being asked in the referendum regards paying a minimum deposit guarantee to the UK and the Dutch Governments that the Icelandic Government has never refused to pay.

But the absolutely stunning aspect is the fact that although some of those who lead the ‘no’ are people who were in power during the boom years that lead to the collapse plenty of Icelanders still seem to be willing to head their opinion.

Gylfi Magnusson professor of economics at the University of Iceland was a popular minister of trade and finance for two years in the post-collapse Government that was elected in spring 2009. He was independent, not part of any political party and was widely trusted. He has been advocating for a ‘yes’ in the referendum tomorrow. David Oddsson is a previous leader of the Independence Party, PM during the 90s and well into last decade who then secured himself the post of Governor of the Central Bank 2005-2009 when he was pushed out by the present Government. Oddsson is now an editor of the newspaper Morgunbladid and very driven on the ‘no’ side. – As one countryman pointed out to me, it’s intriguing that so many Icelanders prefer to listen to Oddsson than Magnusson where Oddsson has a clear political agenda and Magnusson doesn’t.

Eva Joly, the judge who put French dignitaries to prison in the Elf case, was a consultant to the Special Prosecutor in Iceland. She took all matters Icelandic to her heart. In an article in the Guardian today, Joly is telling Icelanders to say ‘no’, to show financiers of this world that they shouldn’t be bailed out. – This will reach many Icelandic hearts; Icelanders have a predilection for being an example to the world. It didn’t work in banking but saying no the the banking system might work, they think.

Unfortunately, there are some misunderstandings in Joly’s article. Icesave is in no way comparable to the bailouts in Ireland and Greece. Iceland did indeed the opposite, let the banks fail. And Ireland and Greece would do a lot to get the interest rates that are on the Icesave repayment.

With Icesave, the Icelandic state is honouring earlier agreements with the Dutch and the UK government, regarding deposits. Icesave is about a top up by the Icelandic State since assets from Landsbanki, that ran Icesave, will most likely go a long way to cover Icesave. In 2008 the Icelandic government guaranteed all deposits in Icelandic banks in Iceland but left it to the Dutch and UK to pick up the pieces there, discriminating between Icelanders and foreigners to save the Lilliputian but overstretched economy.

All this goes to show that emotions run high and that leaves little space for reason. A ‘no’ will keep Iceland hanging in the air for months and eventually years to come, in a situation where they themselves have very little control over the course of events. That seems to serve interests that want to keep Iceland isolated. Those who are trying to construct something new in the Icelandic economy tend to be on the ‘yes’ side.

Those who advocate for ‘yes’ underline that a ‘yes’ won’t eliminate all uncertainty – but it would at least give mental space for Iceland to rebuild the economy, no trivial task in a country with capital restrictions. The referendum seems to be about saying ‘no’ and holding on to the mental fetters of an Icesave process that can drag on for months and years, with no control over events by Icelanders – or saying ‘yes’ and moving on with rebuilding the economy, tackling any uncertainties if and when they arise.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

The first OSP ruling: 2 years jail sentence

This morning, Reykjavik County Court ruled in the first case brought by the Office of the Special Prosecutor. Baldur Gudlaugsson was the permanent secretary at the Ministry of Finance in Iceland. He was charged in 2009 the the OSP for insider trading and breach of duty as a civil servant when he sold his shares in Landsbanki on September 17 and 18 2008 for ISK192m (now just ca €1,2m).

The County Court has now ruled: 2 years prison, whereof Gudlaugsson must serve at least a year, as well as paying back the proceeds of the sale.

Gudlaugsson was never a major player on the Icelandic business scene but he was closely connected to the Independence Party, especially to its former leader David Oddsson.

The ruling was completely in line what the prosecutor had asked for. It shows that in this fairly simple case the OSP was able to formulate charges and bring them through. The cases to come will be far more complex but at least this first step shows a firm grasp, which is promising.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Rowland and Jo Lewis shareholders in MP bank in Iceland

After buying Kaupthing Luxembourg, the object of serial searches by the Icelandic Special Prosecutor and now also the UK Serious Fraud Office, David Rowland hasn’t lost the appetite for Icelandic banks with a questionable reputation. He, together with the ex-Kaupthing Singer & Friedlander client, Jo Lewis, is buying 10% of the Icelandic bank MP Bank, according to Vidskiptabladid, the Icelandic business newspaper.

MP bank survived the crash but now needs more equity. A group of Icelandic shareholders, led by Skuli Mogensen, earlier CEO of Oz. Oz was an Icelandic dotcom venture in the 90s that a huge number of Icelanders lost money on in a case that was never investigated. According to Vidskiptabladid, the Icelanders have procured 10% from Rowland, Lewis and a third foreign investor who hasn’t been named.

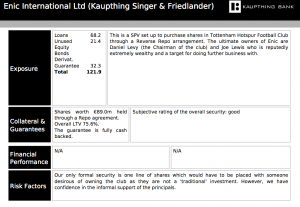

According to the leaked Kaupthing loan book, Lewis and Daniel Levy, through their holding company Enic, had a loan facility with KSF of €121.9 million, in a ‘reverse repo’ arrangement, against a collateral in shares in their trophee asset Tottenham Hotspur, worth only €89m, meaning the loan was only partly covered. A note on the risk read: “Our only formal security is one line of shares which would have to be placed with someone desirous of owning the club as they are not a traditional investment.” I.e., the collateral was highly illiquid. Yet, it said that the subjective rating of the collateral was ‘good.’

Lewis and Levy, the chairman of the club, used the loan to raise their stake in Tottenham to 84% in 2007, the year of golden deals. It is fair to say that by receiving this loan, Lewis and Levy had firmly placed themselves as clients that KSF wanted to keep happy with good deals, or as it read in the loan book: “Joe Lewis is reputedly extremely wealthy and a target for doing further business with.’ I.e. KSF wanted to smooze up to Lewis by offering him a bit of something extra.

From any normal business perspective it beggars belief that Rowland, now teamed up with Lewis, would want to buy into a bank in Iceland. A bank under scrutiny from the regulator where the MP himself, its founder Margeir Petursson a famous chess player, has resigned. Petursson had until last year an image of being whiter than snow in the Icelandic business community. There is now some ash on the snow. Deals between MP bank and Byr, a saving society, are part of charges that the Office of the Special Prosecutor has pressed i.a. against the former MP CEO. In addition, Rowland and Lewis are buying into a bank in a country with capital restrictions. Rowland, through Havilland, is investing in Belarus. MP operates in Ukraine.

There have been consistent rumours that Rowland bought Kaupthing Luxembourg as a front man for someone else. Rowland has always denied this, saying the bank is his and his alone. These rumours will flare up now that he moves to buy shares in MP bank. Hasn’t Rowland had enough of buying into Icelandic banks with questionable reputation? But at least, he will recognise the Special Prosecutor Olafur Hauksson if ever he meets him in the corridors of MP Bank.

Here is the page from the Kaupthing loan book, on the Enic loan (click on it to enlarge):

*An update: the third investor is a Canadian tax lawyer, Robert Raich, with no apparent Icelandic connections.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

After the house searches in Luxembourg

The house searches instigated by the Office of the Special Prosecutor in Iceland, the UK Serious Fraud Office and the Luxembourg police are now over. Investigators are still in Luxembourg, conducting questioning related to the searches.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

“Lessons from a collapse of a financial system”

An article, published in Economic Policy by Sigridur Benediktsdottir, an economist at Yale and one of the three members of the Special Investigative Commission that wrote the SIC report on the collapse of the Icelandic banks, Jon Danielsson senior lecturer at the LSE and Gylfi Zoega professor at the University of Iceland, deals with the above topic. It also throws light on some of the problems concerning Icesave.

The summary:

The paper draws lessons from the collapse of Iceland’s banking system in October 2008. The rapid expansion of the banking system following its privatization in the early 2000s is explained, as well as the inherent fragility due to the size of the banking system relative to the domestic economy and the central bank’s reserves, market manipulation enabling bank capital to expand rapidly and the weak and understaffed public institutions. Most of Iceland’s banking system was traditionally in state hands but was privatized and sold to politically favoured entities at the turn of the century, with laws and regulations subsequently changed to facilitate the expansion of the banking system. Political connections and the tacit support of the authorities enabled senior bank managers and key shareholders to extract significant private benefits while shifting risk to domestic and foreign taxpayers and foreign creditors.

These problems were exacerbated by symptoms of what the paper terms the small country syndrome. The size of the banking sector made the central bank incapable of serving as the lender of last resort. The domestic supervisor, the central bank and the ministries in charge of economic affairs were understaffed and lacking in experience in how to manage a large financial sector. The rapid growth was also ultimately unsustainable due to high levels of leverage and a weak capital base due to both the rapid expansion of balance sheets and lending to finance investment in own shares. The episode demonstrates the importance of closely monitoring rapidly growing financial institutions and even possibly slowing growth when institutions are systemically important.

One lesson to be drawn from the crisis relates to the role of politics in a financial crisis. The Icelandic authorities as a matter of policy encouraged the creation of an international banking centre. This involved the privatization and deregulation of the banking system, rules and regulations being relaxed and the neglect of financial supervision. Another lesson is that floating exchange rates can be hazardous in the presence of large capital flows. The central bank raised interest rates during the boom years in order to meet an inflation target. This created an interest rate differential with other countries that encourages a large volume of carry trades and incentivized domestic agents to borrow in foreign currency. Both conspired to create an asset price bubble, excessive currency appreciation and – counter-intuitively – high inflation.

The result was that monetary policy as conducted was ineffective at curbing domestic demand. The eventual large depreciation of the currency made a large section of the economy insolvent. Finally, there are lessons about the European passport system in financial services and the common market. The Icelandic banks had the right to set up branches in the European Union by means of the passport on the explicit assumption that home regulators were exercising adequate controls.

The collapse of the banks left the United Kingdom and the Netherlands with significant costs, demonstrating the inherent weakness in the passport when one member country can undercut the supervisory standards of other member countries. For the passport system to work, the home supervisor must be trustworthy.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Icesave – an end in sight or chapter 4?

In Iceland, Icesave III is hotly debated, splitting families and work places. Most Icelanders have a story to tell of a family party where tempers flared debating Icesave and the party came to an acrimonious end. The polls indicate a very close run, with an earlier majority for a yes shrinking.

Compared to last year, there is much less attention abroad on the Icesave referendum this time around. A foreign journalist who has covered Icelandic affairs for the last few years said to me recently that it was hard to make his editor interested in Icesave third time around. If Iceland was really going to pay and got much better terms third time round why didn’t they accept the agreement?

As regular Icelog readers will know it isn’t quite that simple. Yes, the Icelandic negotiation team, this time led by Lee Buchheit an American lawyer experienced in sovereign debt, negotiated a much better deal (explained here by Buchheit). Yes, there was a strong majority in Althingi for the deal, also among the opposition. Still, the Icelandic president chose to ignore the parliamentary rule and sent the bill to a referendum. The referendum is on this coming Saturday, April 9.

Icesave was never a major issue in Britain and the Netherlands as the respective governments chose to bail out the deposit holders. It is not correct that the two governments did this without asking Iceland. The Icelandic government, at that time a coalition with the social democrats, led by the Independence Party (conservative) accepted that the two governments would pay the deposit holders the €20.000 minimum guaranteed on Iceland’s behalf.

As Iceland’s three major banks collapsed in October 2008 the country became the first victim of the credit crunch (though it’s becoming more and more clear that fraud played a substantial part in the banks’ demise). Since then, much greater financial calamities have hit first Greece and then Ireland, two countries bailed out by the IMF and the EU. Portugal and Spain are still facing severe funding problems. In an international context the Icelandic events of October 2008 have turned into an introduction to what went wrong in the Western financial systems. That is i.a. how the events of the last few years are presented in brilliant documentary, Inside Job, by Charles Ferguson.

In spite of a general disinterest in Icesave everywhere except in Iceland many experts follow the course of events. Financial analysts and other debt nerds notice that while the Greeks and the Irish have to pay around and above 6% in interest on their loans the interests on Icesave III are around the half of that figure. The reason is that the interest rates for the two countries on one hand and Iceland on the other reflect two very different things. The interests on the loans to Greece and Ireland reflect the risk involved in lending to these two countries. The low Icesave III interests reflect the fact that though Icelandic regulators bore the main responsibility for regulating Icesave the Dutch and the British regulators shared some of the responsibility.

Last year, the referendum was widely interpreted by the international media as a story of a little country defying the Goliaths of the financial markets. Icesave III tells a whole different story. Iceland is getting far better interest rates than both Greece and Ireland. Enda Kenny and his party, Fine Gael came to power in Ireland by promising to renegotiate the interest rates of the loans to Ireland.

Now it might soon be Greece and Ireland’s turn to defy the big bands by refusing to pay the bondholders every cent back and insist on haircuts. Shouldn’t the banks shoulder part of the responsibility for having sunk far too much money into the Greek and Irish economy? Icesave isn’t about paying bondholders but about honouring a deposit guarantee on deposits owned by ordinary people who sought out the high interest rates that Landsbanki offered (and every Money section in the UK papers recommended), as they were being told that the bank was regulated in Iceland, as well as by the respective financial services authorities in the two countries (because it was never the meaning that cross-border branches should be less well regulated than home banks or subsidiaries of foreign banks). And as said earlier, the joint responsibility is reflected in the radically lower interest rates in Icesave III.

The Icesave debate in Iceland doesn’t have any recent foreign parallel in terms of the subject of the debate. But there are striking similarities between the Icesave debate and the debates in Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden on a EU membership.

The question that Icelanders are being asked in this referendum is if they want to ratify the law regarding Icesave that Althingi voted for but the president refused to sign. However, judging from the debate one might conclude that Icesave threatened Iceland’s independence and sovereignty. In the four Nordic countries and now in Iceland forces farthest to the left and the right in the political spectrum have unified in their crusade against Icesave. New alliances are created but after the referendum left and right tend retreat to former positions.

A general characteristic of referenda is that some of the voters don’t necessarily form an objective opinion of the question asked but vote, no matter what, for or against the government in power. The Icelandic government is unpopular and has been wise enough not the advocate a yes vote too strongly for fear of driving its opponents into the arms of the no side.

In the Nordic EU debates there was a strong tendency by the no side to exaggerate the uncertainty as to the course of event within the EU. Consequently, by saying yes, according to the no side, people are courting uncertainty. The no side was striving to keep things as they were and close the door to the outer world while the tendency on the yes side was just the opposite. The same tendency is prevalent in Iceland in spite of the fact that there is much greater uncertainty as to what will happen if the outcome is a victory to the no vote. The no side hasn’t tried to address the fact that a no vote will give rise to unchartered waters. Nor does it acknowledge the various difficulties that an unfinished Icesave agreement inflicts on Iceland.

In addition to unavoidable costs Icesave has hijacked the interest and attention from other important things, such as attracting foreign investment, dealing with unemployment and other issues of vital importance. It’s safe to say that Icesave has deflected important issues from the attention they need and deserve. For some, that might exactly have been their hidden benefit of saying no.

In Iceland, a public debate of hotly contested issues differs on one important point from the debate in the neighbouring countries. In Iceland there is a strong tendency to focus less on the opponent’s arguments and more on personal issues such as who he sides with and why. Political muck-racking isn’t a uniquely Icelandic sport but muck-racking is more noticeable in the public debate in Iceland, not just behind closed doors. That makes the Icelandic debate particularly ferocious.

That is also the case now. The no side is run most viciously by David Oddsson editor of Morgunbladid, governor of the Central Bank during the crash and a leader of the conservatives in the 90s and the first part of last decade. His motive falls in a familiar category, he’s trying to bring down the government. But he also seems to be using the opportunity to make the situation intolerable for the present leader of the party, Bjarni Benediktsson who advocates for a yes in the referendum.

Benediktsson might have to resign as a leader if the no vote win. However crazy it sounds, there are speculations that Oddsson might run again in a leadership contest. Be that as it may: if Icesave III falls Oddsson will be much stronger than before and that will strengthen his position in two major debates coming up soon. One is on the future of the transferable fishing quota system, where Oddsson defends the present system. The other is the EU membership. Because of Oddsson’s vocal stance on Icesave, a yes vote is also a vote against his continued influence in Icelandic politics.

Another leader, who might face a challenge to his leadership, depending on the outcome, is Sigmundur David Gunnlaugsson leader of the Progressive party, in opposition like the conservatives. He is advocating a no and that has forged strong relationship between him and his party to the Oddsson wing of no vote.

A no vote will have widespread ramifications, both politically and financially. Politically, a yes vote will most likely not cause any major changes.

But the greatest change brought out by a yes vote would be that Icelanders could stop talking about Icesave and concentrate on the far more pressing issues that Icesave has over shadowed.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Lee Buchheit on Icesave

Today, Ruv aired an interview *(ca 20 mins; it starts with a short introduction in Icelandic but is in English) with the American lawyer Lee Buchheit who lead the Icelandic team in the Icesave negotiations with the UK and the Dutch. The referendum on Icesave takes place next Sat., April 9.

The votes seem to be fairly evenly split. Though polls have lately given majority to the ‘yes’ side there might be a greater momentum for the ‘no’ among undecided voters.

Judging from comments on the blog of Egill Helgason, the journalist who interviewed Buchheit, the clear and balanced presention that Buchheit gave of the negotiation and the possible consequences of a ‘yes’ and ‘no’ vote, did make an impression.

Icesave has repeatedly been presented as the most serious and wide-reaching effect of the collapse of the bank. It isn’t but it has blocked and stalled many other things in Iceland. Measuring the damage of prolonged Icesave limbo is difficult but in spite of unavoidable uncertainty Buchheit made a strong and convincing case for the ‘yes’ vote.

*The link has been improved and now leads directly to the interview.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Wholesale deposits: priority claims

This morning, the Reykjavik County Court ruled in nine cases regarding wholesale deposits, seven in Landsbanki, two in Glitnir. In each of the cases there tens of entities involved. The crux of the cases was the status of the wholesale deposits as claims, if they are a priority claim or not. Landsbanki had defined these deposits as a priority claim, Glitnir hadn’t. The Court has now defined them as priority claims. That puts them first in the queue to be paid out. Others, with general claims, will loose out.

This means that the many institutions – councils, universities, banks and others, in the UK and elsewhere – who had their money as wholesale deposits with the Icelandic banks will recover a larger percentage of their deposits with the collapsed banks. However, these rulings will no doubt be appealed to the Supreme Court so it’s still too early for the wholesale depositors to celebrate.

Part of the emergency measures on October 6, when the Icelandic banking system was about to collapse was to define deposits as priority claims in order to safeguard the interest of ordinary deposit holders. The government then went a step further, guaranteeing all deposits in the banks in Iceland but not abroad. Thus, the Icesave affair – but that’s another saga.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Banque Havilland: searches still going on

According to Luxembourg sources, Banque Havilland is still full of policemen and others who are searching the premises. The house searches started on Tuesday and are lead by the Luxembourg police, with people from the Serious Fraud Office and the Office of the Special Prosecutor in Iceland present. The searches are being done at the request of the SFO and the OSP. The feeling is the the search is well targeted and that the authorities know very well what they are looking for.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.