Archive for November, 2016

ESA finds Iceland in compliance re offshore króna measures

The EFTA Surveillance Authority, ESA, has now closed two complaints re treatment of offshore króna assets by Icelandic authority: ESA finds the Icelandic laws in compliance with the EEA Agreement (see ESA press release here, the full decision here). The disputed laws were part of measures taken in order to remove capital controls in Iceland.

I have earlier written extensively about the offshore króna issue, also the rather bizarre action taken by the so-called Iceland Watch against the Central Bank of Iceland, which rubbed Icelanders, even those sympathetic to the point of view taken by the offshore króna holders, completely the wrong way. The sound points, which can be made by the offshore króna holders, were missed or ignored and instead the Iceland Watch action was shrill and shallow, based on spurious facts.

In general EEA states are permitted, under the EEA Agreement, to take protective measures when a states is experiencing difficulties as regards its balance of payments. As spelled out in the press release the states, in such situations, “are allowed to implement a national economic and monetary policy aimed at overcoming economic difficulties, as long as the criteria for these protective measures are met.”

As Frank J. Büchel, the ESA College member responsible for financial markets sums it up: “Iceland’s treatment of offshore króna assets is a protective measure within the meaning of the EEA Agreement. The overall objective of the Icelandic law is to create a foundation for unrestricted cross-border trade with Icelandic krónur, which will eventually allow Iceland to again participate fully in the free movement of capital.”

The funds in question, Eaton Vance and Autonomy, are testing their case in an Icelandic court.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Trump and Berlusconi: why some voters prefer “a son of a bitch”

In spite of exemptions over the years it’s been taken for granted that a politician running for office should be a decent law-abiding human being. Consequently, the media has focused on exposing politicians repeatedly caught lying, womanising, making racist or misogynistic remarks and involved in shady business dealings assuming any or all of this would make politicians unfit for office. Silvio Berlusconi, longest serving Italy’s prime minister, disproved that. Now Donald Trump’s victory has shown that some voters not only don’t mind what some see as repugnant behaviour but do indeed find it appealing. – I first understood this in 2008 when I spoke to an Italian voter rooting for Silvio Berlusconi precisely because Berlusconi was ‘a son of a bitch like the rest of us!’

“Mussolini never killed anyone. Mussolini used to send people on vacation in internal exile,” Silvio Berlusconi then prime minister of Italy said in a newspaper interview in 2003. In a speech that same year at the New York Stock Exchange he encouraged investment in Italy because “we have beautiful secretaries… superb girls.” Another infamous Berlusconi comment was that US president Barack Obama and his wife must have sunbathed together since they were equally tanned. The career of the now 80 years old Berlusconi is littered with racist, misogynistic comments and peculiar understanding of history, as well as serious allegations of relations to organised crime. All of this was well known when he first won elections in Italy in 1994 as a media tycoon and the country’s wealthiest man.

It’s as yet untested if Donald Trump was right in saying he could, literally, get away with murder and still not lose voters but like Berlusconi Trump has been able to get away with roughly everything else: racism, misogyny, not paying tax – he’s too smart to pay tax and might actually never make his tax returns public – mob-relations, shady business dealings and Russian connections.

Being an Italian prime minister is next to nothing compared to being a US president. Berlusconi was in and out of power for almost twenty years, winning elections in 2001 and 2008 and losing only by a whisker in 2013. Trump can at most get eight years in power. But apart from the different standing of the two offices the two men, as a political phenomenon, are strikingly similar. Like Berlusconi, Trump was to begin with treated as a political joke.

The lesson here is that accidental politicians – accidental because they turned to politics as outsiders late in life – like Berlusconi and Trump appeal to voters not necessarily in spite of their remarks but because of them. For some voters they are a type of “loveable rascals” immune to media exposures, their spell-like influence based on their business success as if their personal success could be repeated nationwide. The almost twenty year experiment with Berlusconi did help his own businesses, not the country he was running for almost half of that time.

It’s not that all Italian or all Americans have fallen in love with the “lovable rascals:” during his time in power Berlusconi’s party got up to 30% of votes. Since half of US voters didn’t vote it took only around 25% of the voters to sign Trump’s invitation for the White House and as we know Hillary Clinton did indeed get more votes.

The food for thought for the media is that investigations and exposures only go so far. Higher electoral participation would probably help fight demagogues and racists – a worthy project for the US political parties and civil society in general.

1990s – no end to history but a trend towards merging of left and right

Berlusconi built his empire from scratch, Trump started off with some inherited wealth. Although outsiders in the political system they rose on political ties and entered into politics at times of economic upheaval. In Italy growth fell in the early 1990s, zick-zacked on and has been dismal since 2000. Trump’s victory is underpinned by stagnant wages in US for familiar reasons: globalisation, low union participation and technological changes though the exact weight of the three factors is disputed.

Malaise in the old parties both on the left and the right goes far in explaining the success of the two politicians. In Italy, the parties left right and centre were for years in a kaleidoscopic flux, and still are to a certain degree, following the collapse of the political system based on the Christian Democrats and the Socialists brought down by the end of the Soviet Union in 1991 and the ‘Mani Pulite’ corruption cases.

Berlusconi founded his own party in 1993 and conquered the Italian right-of-centre, orphaned after the demise of the Christian democrats, many of whom found a second home and political career in Berlusconi’s Forza Italia. After his first short stint as prime minister 1994 to 1995 the Italian left kept Berlusconi out of government but he didn’t give up. His time came in the elections in 2001 when he sat as prime minister until 2006, a record in post-war Italy and then again 2008 to 2011.

Trump won a double victory: first by hijacking the Republican candidacy against the party elite, then by winning over the Democratic candidate Hillary Clinton. Contrary to the outsider Barack Obama she belonged to the party elite who since the 1990s, her husband’s time in power, have embraced capitalism, light regulation and big corporation – a course that hasn’t helped to improve the lot of the lower and middle class.

As the Nobel-prize economist Angus Deaton spelled out so brilliantly in his book “The Great Escape”: when banks and private wealth fund campaigns for Republicans and Democrats both ends of the political spectrum root for the same special interest policies and the general public is left behind (the long view on the Democrats is brilliantly told here, by Matt Stoller).

Berlusconi and Trump: the “lovable rascals” framing their own political persona

As politicians have lost trust businessmen have gained greater weight in shaming politicians and public officials claiming that a country should be run like a business. Both Berlusconi and Trump have incessantly touted their business acumen to prove their political astuteness emphasising that being wealthy they can’t be bribed. In addition Berlusconi owns a famous football club in a football-besotted country.

With a party of his own Berlusconi set his own rules. Trump welcomed his loss of support among the Republican elite, claiming it unshackled him. Both were free to create their own political persona, both seem to be consummate actors. Trump changed his rhetoric from the primaries to the campaign and now seems to be interpreting his presidential role in yet another way. The controversial statements were, as Trump said on CBS’s Sixty Minutes, “necessary to win.”

It’s too simple to say that both men have found support among working class angry men. They found support among women (Berlusconi though less than Trump) and both appeal to well-off voters. The anger, now the common explanation for Trump’s success (and the Brexit outcome), hadn’t really been discovered when Berlusconi rose to power. But both men are very good at vilifying their opponents: Berlusconi stoked the fear of communism; Trump claimed Hillary Clinton was the embodiment of all the evil in Washington.

For those who find the behaviour of first Berlusconi and now Trump inexcusable and worry about aspects of their businesses, quite apart from their rambling politics, it’s difficult to understand that media investigations and exposures has little or no effect on their supporters. It’s not necessarily that their followers don’t know about the questionable sides, they often do. Some may identify with them on the premise that no one is perfect. For others, the two are some sort of “loveable rascals.”

It doesn’t mean that any kind of foul-mouthed shady business man can win support and rise to power but foulmouthed and frivolous inexperienced politicians seemed unthinkable before the rise of Berlusconi in 1990s in Italy and of Trump most recently in the US. “Lovable rascal” are exempts from the criteria normally used and critical coverage doesn’t really bite: their voters like them as they are.

Confirmed Putin-admiring sinners with strong appeal to religious voters

Berlusconi was a prime minister in a country partly ruled by the Vatican and has courted voters who support conservative family values. Also Trump has diligently appealed to devout evangelical Christians. These voters seem to ignore that Berlusconi and Trump have diligently sought media attention surrounded by young girls, Trump as a co-owner of the Miss Universe Organization, Berlusconi via his TV stations, feeding stories of affairs and escapades. Berlusconi has been involved in a string of court cases due to sex with underage prostitutes.

This paradox is part of the “loveable rascal” – the two are exempt from the ethics their Christian followers normally hold in esteem.

Both men have shown great vanity in having gone to some length in fighting receding hairline. As is now so common among the far-right both men openly admire Russia’s president Vladimir Putin. Berlusconi has hosted Putin in style at his luxury villa in Sardinia and visited Putin at his dacha. And both Trump and Berlusconi have spoken out against international sanctions aimed at Putin’s Russia.

The “I-me-mine” self-centred political discourse and mixture of public and private interests

Since their claim to power rests on their business success the political discourse of Berlusconi and Trump is strikingly self-centred: a string of “I-me-mine” utterances with rambling political messages. Both are devoid of any oratory excellence and their vocabulary is mundane.

Berlusconi’s general political direction is centre-right but often unfocused apart from the unscrupulous defence of his own interests. Shortly after he became prime minister for the second time the so-called Gasparri Act on media ownership was introduced, adapted to Berlusconi’s share of Italian media. When Cesare Previti, a close collaborator, ended in prison in 2006 for tax fraud it took only days until the law had been changed enabling white-collar criminals to serve imprisonment at home rather than in prison.

In general, Berlusconi’s almost twenty years in politics, as a senator and prime minister, were spent in the shadow of endless investigations into his businesses and private life, keeping his lawyers busy. An uninterrupted time of personal fights with judges and that part of the media he didn’t own. Journalists at Rai, the public broadcaster, who criticised Berlusconi lost their jobs and Italy fell down the list of free media.

Trump seems to think he doesn’t need to divest from his businesses. For now he is only president-elect but if the similarities with Berlusconi continue once Trump is in the White House he can be expected to bend and flex power for his own interest. Trump’s time is limited but he can take strength from the fact that just as vulgar behaviour and questionable business dealings didn’t hinder Berlusconi’s rise in politics neither did they shake his power base. Berlusconi won three elections and was in power for nine years from 1994 to 2011.

The bitter lessons of Berlusconi’s long reign

In 2011 Berlusconi his time in power was messily and ungraciously curtailed: having failed utterly to fulfil his promises of reviving the economy he was forced to resign. After being convicted of tax fraud in summer 2013 he lost his last big political fight: to remain a senator in spite of his conviction. Thrown out of the senate after almost twenty years he’s still the leader of his much-marginalised party, now polling around 12%, down from 30% in the elections 2013.

Berlusconi’s businesses went from strength to strength but Berlusconi’s Italy suffered low growth and stagnation.

We don’t know what Trump’s time in office will be like. Personally he isn’t half as wealthy and powerful as Berlusconi was – the wealthiest Italian when he first became prime minister in 1994. It’s unclear how Trump’s businesses will be run while he takes a stab at running the country. His businesses might well come under investigation and we might see a similar wrestle between Trump and investigators as the ones Berlusconi fought.

Although Italy didn’t thrive in the first decade of the 21st century, the Berlusconi era, he seemed for years invincible for lack of better options and for his promises and appeal. For the “lovable rascal” politician it doesn’t seem to matter if their promises never come to fruition or if they say one thing and do something else – their policies are not the only root of their popularity.

Democracy, lies and the media

Many Italians worried that Berlusconi undermined democracy both in his overt use of power and his own media to further own interests and the more covert use, such as putting pressure on judges and Rai journalists. Whereas Romans were fed bread and games Berlusconi fed his voters on TV shows with scantily clad girls. Berlusconismo referred to all of this: his centre-right ideas, his use of power to further own interests and the vulgarity of it all.

The palpable sense of political disillusionment in the wake of Berlusconi hobbling off the political scene in a country with depressed economy hasn’t made it any easier to be an Italian politician. The void left space for this strange phenomenon that is Beppe Grillo and his muddled Cinque Stelle movement in addition to the constant flux of parties merging or forming new coalitions.

But the political momentum is neither on the far-right Lega movement and the cleaned-up fascist party, Alleanza Nazionale nor the far-left fringe. Italian democracy after Berlusconi isn’t weaker than earlier in spite of the unashamed demagogy and his self-serving use of power. There is no second Berlusconi in sight in Italy.

Berlusconi seemed to be a singular political event but with the rise of Donald Trump Berlusconi is no longer unique. And there seem to many American voters who think like the Italian one who in 2008 told me he was going to vote for Berlusconi because Berlusconi was ‘a son of a bitch like the rest of us!’ – these voters don’t care what the media reports on their chosen politicians. Consequently, the media needs to figure out how to operate in times of flagrant lies and dirty deals from politicians who can appeal to voters in spite of what was once thought to rule out any possibility of a political career.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Kaupthing – prison sentences for market manipulation reach Greece

On October 6 the Supreme Court in Iceland ruled in one of the largest collapse cases so car where nine Kaupthing managers were charged for market manipulation (see an earlier Icelog). As in a similar case against Landsbanki managers the Kaupthing bankers were found guilty. The Reykjavík District Court had already ruled in the Kaupthing market manipulation case in June 2015.

This is how Rúv presented the Supreme Court judgement in October. Kaupthing’s CEO Hreiðar Már Sigurðsson was sentenced to six months in prison, in addition to the 5 1/5 years in the so-called al Thani case where the bank’s executive chairman had received a four year sentence. The market manipulation case added a year to that case. Magnús Guðmundsson managing director of Kaupthing Luxembourg was found guilty but did not receive a further sentence, having been sentenced to 4 1/2 years in the al Thani case.

Other sentenced in October were Ingólfur Helgason managing director of Kaupthing Iceland, 4 1/2 years and Bjarki Diego head of lending 2 1/2 years. Four employees were found guilty: three of them got suspended sentences. The fourth, Björk Þórarinsdóttir was found guilty but not sentenced.

The investigations by the Office of the Special Prosecutor, now the District Prosecutor, have so far resulted in finding guilty around thirty bankers and others related to the banks. As I have often pointed out: the penal code in Iceland is mostly similar to the code in other neighbouring European countries but the difference was the will of the Prosecutor to investigate very complex cases, taking on a huge task undaunted. That’s the difference – no case was seen as being too complicated to investigate.

Last week, the following article was in one of the Greek papers. From the photos I can see that this article is about the above case. Something for the Greeks to ponder on: what’s done in Iceland, less in Greece.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Iceland: back to its old conservative roots?

“Epic success! There are a lot of coalition possibilities” tweeted elated newly elected Pirate MP Smári McCarthy the morning after polling day. Quite true, the Pirates did well, though less well than opinion polls had indicated. Two of the four old parties, the Left Greens and the Independence Party could also claim success. The other two oldies, the Progressives and the Social Democrats, suffered losses. Quite true, with Bright Future and the new-comer Viðreisn, Revival, in total seven instead of earlier six parties, there are plenty of theoretical coalition possibilities. But so far, the party leaders have been eliminating them one by one leaving decidedly few tangible ones. Unless the new forces manage to gain seats in a coalition government Iceland might be heading towards a conservative future in line with its political history.

In spite of the unruly Pirates and other new parties the elections October 29 went against the myth of Iceland abroad as a country rebelling against old powers – the myth of a country that lost most of its financial system in a few days in October 2008 instead of a bailout, then set about to crowd-write a new constitution, investigate its banks and bankers and jailing some of them and is now, somehow as a result of all of this, doing extremely well.

True, Iceland is doing well – mostly due to pure luck: low oil prices, high fish prices on international markets and being the darling of discerning well-heeled tourists. No new constitution so far and at a closer scrutiny the elections results show a strong conservative trend, in line with the strong conservative historical trend in Icelandic history: during the 72 years since the founding of the Icelandic republic in 1944 the Independence Party has been in government for 57 years, most often leading a coalition and never more than two to three years in opposition except when the recent left government kept the party out in the cold for four years, 2009 to 2013.

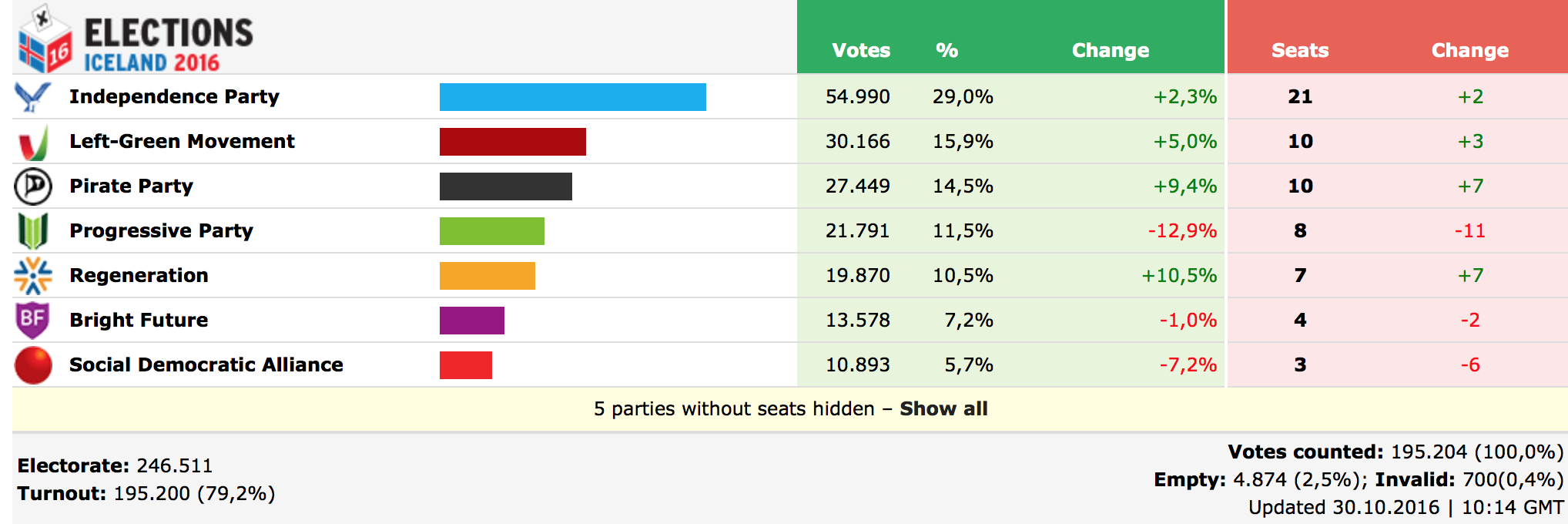

The results: historic shift to new parties

(From Iceland Monitor)

With 63 MPs the minimum majority is 32 MPs.

Of the seven parties now in Alþingi four are seen as the old parties – Independence Party, Left Green, Progressives and the social democrats – in Iceland often called the “Four-party.” Their share of the votes was 62%, the lowest ever and down from 75% in the 2013 elections, meaning that the new parties grabbed 38%. A historic shift since the old parties have for decades captured 80-90% of the votes. The Four-party now has 42 seats, the new-comers 21 seats.

The left government 2009 to 2013: an exception rather than a new direction

As strongly as the Nordic countries have been social democratic Iceland has been conservative. And still is. Iceland is not living up to its radical image and the left government of 2009 to 2013 was more the exception than a change of direction. The present outcome shows no left swing but the swing to the new parties may prove to be a game changer in Icelandic politics.

The left parties, Left Green and the social democrats, now have thirteen seats, compared to sixteen in 2013, the centre/neither-left-nor-right Bright Future, the Pirates and the Progressives have 22 seats, 28 in 2013 but the right/conservative parties, the Independence Party and Revival, are the largest faction with 28 seats, up from nineteen in 2013. – As I heard it put recently in Iceland there are Progressive-like conservatives in all parties and the Progressives tend to strengthen the worst sides of the Independence Party, such as illiberal cronyism.

With seven parties in Alþingi, the Icelandic Parliament, up from six during recent parliamentary term, the party game of guessing the possible coalition, both in terms of number of MPs and political synergies, is now on in Iceland.

A right centre outcome seems more likely than a left one

It’s the role of the president to decide which leader gets the mandate to form a government, normally the leader of the largest party but other leaders are however free to try. The task facing the newly elected president Guðni Th. Jóhannesson, a historian with the Icelandic presidency as his field of expertise, seems a tad complicated.

The president followed the traditional approach and gave the mandate to Bjarni Benediktsson leader of the largest party, the Independence Party who first met with the Progressive’s Sigurður Ingi Jóhannsson who lead the Progressive-Independence coalition that has just resigned. The two parties now only have 29 seats between them. – Given the right-leaning/conservative weight in Alþingi a right-centre government might seem more likely than a left government.

The leader of Bright Future Óttar Proppé, seen as a possible coalition partner for the conservatives, seemed surprisingly unenthusiastic: to him a coalition with the Independence Party and Revival “doesn’t seem like an exciting option,” adding that there is a large distance policy-wise between his party and the largest one.

Proppé had earlier suggested to the president that Revival’s leader Benedikt Jóhannesson be given the mandate; Jóhannesson has already suggested he’s better poised to form a government than Benediktsson since Revival can appeal both to left and right.

Katrín Jakobsdóttir leader of the Left Green has stated that her party would be willing to attempt forming a five party centre-left coalition, i.e. all parties except the Independence Party and the Progressives, a rather messy option. The Pirates leader Birgitta Jónsdóttir has said her party could defend a minority left government.

Four winners

Since the founding of the Republic of Iceland in 1944 the Independence Party has always been the country’s largest party and the one most often in government. Its worst ever result was in the 2009 elections, when it got only 16 seats. Getting 19 in 2013 and 21 seats now may seem good but it’s well below the now unreachable well over 30% in earlier decades. Yet, gaining two seats now makes the party a winner.

Its leader Bjarni Benediktsson sees himself as the obvious choice to form a coalition, given the support of his party but it will strongly test his negotiation skills. In the media he comes across as rather wooden but he’s popular among colleagues, which might make his task easier though he can’t erase policy issues unpopular with the other parties such as the parties anti-EU stance and being the watchdog of the fishing industry.

The Left Green Movement was formed in 1999 when left social democrats split from the old party and joined forces with environmentalists. The Left Green has always been the small left party but is now the largest left party next to the crippled social democrats. The elf-like petite Katrín Jakobsdóttir has imbued the party with fresh energy. Her popularity, far greater than the results of the party, no doubt helped secure a last minute swing against predictions. She has been the obvious candidate to lead a left-leaning government, now an elusive opportunity.

Viðreisn, Revival, is a new centre right party, running for the first time but founded in disgust and anger by liberal conservatives from the business community. In general they felt the Independence Party was turning too illiberal, too close to the fishing industry so as to lose sight of other businesses.

But most of all the Revivalists were angered by the broken promises of the Independence Party in 2013 regarding EU membership. During the 2013 campaign the party tried to ease out of taking a stance on EU by promising to hold a referendum asking if EU membership negotiations should be continued. Once in government the Independence Party broke this promise causing weeks of protests and widespread anger some of which Revival captured.

Revival’s founder Benedikt Jóhannesson was seen as an unlikely leader and admitted as much to begin with but has proved an adept leader, also by attracting some strong and well-known candidates from the Icelandic business community. Getting seven MPs in its first run spells good for the party but history has shown that getting elected is the easy part compared to keeping a new party functioning in harmony. However, the Revival’s energetic start has for the first time in decades given the Independence Party a credible competition on the right wing.

The outcome has made Jóhannesson flush with success and he was quick to put his name forward as the right person to form and lead a centre right government. Revival did no doubt capture some Independence party voters but many of them had already defected to the social democrats now leaving that party for Revival.

The Pirate Party is the winner who lost the great support shown earlier in opinion polls, probably never a likely outcome; growing from three MPs to ten is the success McCarthy tweeted about. The party rose out of protests and demonstrations after the 2008 calamities and ran for the first time in 2013, winning three seats.

Their feisty leader Birgitta Jónsdóttir, with 32.000 Twitter followers and foreign fame for her involvement with Wikileaks and Iceland as a data protection haven, is unlikely to be the first Pirate prime minister in the world. Given that the party has had some in-house friction to deal with – they had to call in an occupational psychologist to restore working relations – the unity of the parliamentary group might be in question, making the party less appealing for others as a coalition partner.

Two losers and one survivor

The Social Democrats suffered a crushing defeat, even worse than the opinion polls had predicted and worse than the dismal outcome in 2013. As parties consumed with infighting – the UK Labour Party springs to mind – the energy of the Social Democrats has been wasted on infighting at the cost of a constructive election campaign. Common to other sister parties in Europe the Icelandic Social Democrats have not been able to come up with a convincing policy and its standing with young people is low.

Party leader Oddný Harðardóttir struggled with her speech on election night when all she seemed to be able to think of was that the party once had a good cause; the long list of helping hands she named sounded like each and every of the few voters left. Harðardóttir has now inevitably resigned, giving space for more destructive infighting. Some wonder if the party will survive, others speculate its remains will unite with the Left Green and restore unity and strength on the left wing. Historically seen, the Icelandic left has always split when it grew, adding strength to the right wing and the indomitable Independence Party.

The Progressive Party has lost its incredible upswing of nineteen MPs in 2013 to a much more plausible eight MPs. Plausible, because its upswing to 24% in 2013 was built on cheap promises made by its leader Sigmundur Davíð Gunnlaugsson that brought him all the way into the Prime Minster’s office. But the votes had hardly been counted in 2013 when voters started to lose faith in the party: it has been on a downward slide towards a more natural, in a historical perspective, just over 10% shares of votes.

This old agrarian centre party, sister party of other old Nordic centre parties of similar origin, has traditionally been related to the Icelandic now mostly defunct cooperative movement and still close to certain special interests in agriculture and fishing. Its strength was to appeal to both the left and the right but under Gunnlaugsson it turned more nationalistic/right-leaning, trying to appeal equally to urbanistas and racists and not only old farmers. His successor, representing more traditional Progressive policies might revert to the old party roots, yet needing to find a modern twist for an old party slowly losing ground.

The Panama Papers exposed Gunnlaugsson as a cheat – he had kept quiet about the infamous Wintris, the offshore company he owned with his wife, meaning the couple had huge assets abroad as Icelanders were locked inside capital controls – and a liar as he tried to ease out of the story. He lost his office and then lost his leadership of the party only shortly before the elections. After the elections he claimed to have had a campaign plan, which would have taken the party to 19%. “A bad loser” commented one Progressive ex-MP. Gunnlaugsson’s successor Sigurður Ingi Jóhansson dryly said Gunnlaugsson had not shared this plan with the party leadership.

Bright Future is one of several parties that rose out of protests following the 2008 banking collapse, partially an offspring of the group close to Jón Gnarr the comedian-turned-mayor of Reykjavík 2010 to 2014. It was the new political darling in 2013, securing six MPs. Seen as a centre left liberal party its leader Óttar Proppé is a soft-spoken intelligent politician. The party has recently been hovering around the 5% limit needed to secure a seat in Alþingi but did in the end better than forecasted, losing only two of six seats. Consequently, the party still has a future in Icelandic politics and possibly even a bright one as it might be essential whatever part of the political spectre a coalition will cover.

Scrabbling with numbers – the eliminated options

Juggling parties and numbers of MPs – the minimum majority is 32 MPs – there are in total seventeen possible combinations for a coalition. Although the Progressives have traditionally been a true centre party appealing to left and right, the first elimination seems to be the Progressive Party, unless a path is found around one specific hindrance: the former party leader.

Were the Progressives offered to be in a coalition and given that Gunnlaugsson is an MP it’s almost unthinkable to form a government without him as a minister; but it seems equally unthinkable that the other parties would want to be in government with him. His career as a prime minster has given all but his ardent admirers the feeling that he is shifty and untrustworthy. His admirers will say that opponents fear his toughness.

In spite of losses the Progressive leadership is eager to get into government but Progressive leader Jóhannsson has so far evaded answering if the party could join a coalition without Gunnlaugsson as a minister. There are speculations that the parliamentary group is split: some support Gunnlaugsson, others his successor but some are now speculating that the party would indeed willingly sacrifice Gunnlaugsson in order to get into government again.

Both Left Green Katrín Jakobsdóttir and the Pirates’ Birgitta Jónsdóttir have excluded joining a government with or lead by the Independence Party. When Jónsdóttir went to meet Benediktsson, holding court to hear views of all the parties, she said she doubted that his party was interested in fighting corruption, a key Pirate issue.

Revival’s Benedikt Jóhannesson excluded reviving the present government of Progressives and the Independence Party by joining them. – Thus, the realistic possibilities seem quite fewer than the theoretical ones.

Scrabbling with numbers – the realistic options

Out of the flurry of the first days and considering parties and policies the most realistic combination seemed to be a government with the Independence Party, Bright Future and Revival. That poses an existential dilemma for Revival: though ideologically close to the Independence Party there is this one marked exception – the EU stance.

In the same vein as the British conservatives, to whom the Independence Party is much more similar than to its Nordic sister parties, the anti-EU sentiments have over the years gradually grown stronger. Bjarni Benediksson was on the pro-EU line around ten years ago but not any longer. The lack of EU option on the right was indeed the single most important reason why Revival was founded as mentioned above.

Jóhannesson is a former fairly influential member of the Independence Party – and a close relative of Benediktsson in a country where blood is always much thicker than water and family-relations matter. One of the party’s MPs, Þorgerður Katrín Gunnarsdóttir, was a minister for the Independence Party in 2003 to 2009 but left politics after the banking collapse, tainted by her husband’s high position with Kaupthing, at the time the largest bank in Iceland.

The question most often put to Revival candidates during the election campaign was if the party wasn’t just the Independence Party under another name. Going into government simply to help the Independence Party stay in power would be unwise as Revival would risk to be seen as exactly that what it’s claimed to be: the Independence Party under another name.

Fishing quota – and EU: a lukewarm topic but possibly a political dividing line

Revival will have to take up the EU matter, i.e. in a coalition with the Independence Party it would have to get that party to fulfil its 2013 promise to hold a referendum on the EU negotiations started under the Left government in summer of 2009. At the time EU membership was driven by the social democrats in spite of the Left Green anti-EU stance: the social democrats had for years campaigned for EU membership, also in the 2009 spring election, and once in government felt they had the mandate to open membership negotiations. The plan was to put a finalised membership agreement to a referendum on membership. Ever since the negotiations started anti-EU forces have claimed it was without a mandate.

The attempts of the Progressive-Independence coalition after it came to power in 2013 to end the negotiation turned into a farce: the two parties didn’t want to bring it up in Alþingi where it risked being voted down and the EU didn’t want to accept a termination unless supported by a parliamentary vote.

Forcing a referendum on the membership negotiation would fulfil Revival’s EU promises and it could most likely count on the support of Bright Future. For the Independence Party it would be a very bitter pill to swallow. Opinion polls have always shown a majority for negotiating though there rarely has been a majority for joining the EU. Event though EU membership isn’t an issue in Icelandic politics it could well draw certain insuperable lines in the coalition talks.

If Revival’s Jóhannesson should be given the mandate to form a government as Bright Future’s Proppé has suggested it would certainly strengthen Jóhannesson’s agenda.

Apart from EU policy Revival has fought for a new agriculture policy, away from the old Progressive emphasis on state aid and most of all for a new way to allocate fishing quota, a hugely contentious issue in Icelandic policies. The two old former coalition partners are dead against any changes whereas all the other parties have presented more or less radical policies to change the present fishery system.

Left government in a conservative country

Ever since the 2013 elections, which ended the left government in power since 2009, the opposition parties have aired the idea of joining political forces against the Progressive-Independence coalition.

Few days before the elections the Pirate leader Birgitta Jónsdóttir called the opposition to a meeting to prepare some sort of a pre-elections alliance or as she stated to clarify the options for a coalition. Revival didn’t accept the invitation and Bright Future wasn’t keen. The Independence Party claimed this was a first step towards a left government and by stoking left fears this Pirate initiative might indeed have driven voters to the conservatives.

Jónsdóttir is now peddling a more simple solution: a minority government of Revival, Bright Future and Left Greens that the Pirates, together with the remains of the Social Democrats, would support. Five parties in a government sounds chaotic – coalitions of three parties have never sat a full term in Iceland. And given the alleged tension in the Pirate Party the other parties might be wary of fastening their colours to the Pirate mast, inside or outside a government.

Minority governments have been rare in Iceland contrary to the other Nordic countries and suggesting this solution as politicians are only starting to explore coalition options will hardly tempt anyone until possibilities of a majority government have been exhausted.

Supporting a government but not being in it would be a plum position for the Pirates. The party has pledged to finish the new constitution, in making since 2008. A new constitution needs to be ratified by a new parliament and the Pirates had called for the coming parliament to sit only for s short period, pass a new constitution and then call elections again. No other party is keen on this and there has been only a limp political drive to finalise a radical rewrite of the constitution.

There are those who dream of a government spanning the Independence Party and the Left Green; this government would however need the third party to have majority. For anti-EU forces this is the ideal government since it would most likely prevent any EU move. But as stated: Left Green Jakobsdóttir has so far claimed the distance between the parties is too great, leaving no basis for such a coalition.

Discontent in a boom without xenophobia and racism

In a certain sense all the new parties are protest parties but not with the sheen of demagogy seen in many other recent European protest parties. The response to the banking crisis and the ensuing massive fall in living standards was certainly a protest against the four old parties giving rise to various new parties of which Bright Future and the Pirates are the only ones now in Alþingi.

The only real touch of demagogy with a tone of xenophobia didn’t come from any of these parties but from the Progressive Party under the leadership of Gunnlaugsson in the 2013 elections and the 2014 local council elections. However, there has so far never been any real appetite in Iceland for this agenda. The Icelandic Popular Front, lingering on the fringe of Icelandic politics for years and the only party offering a pure xenophobic racist agenda, this time got the grand sum of 303 votes or 0.16%.

Compared to the political environment in Europe the real political sensation in Iceland, so far, is that there is no sign of the xenophobia and outright racism in the main parties. Yes, people lost jobs following the 2008 collapse but there wasn’t the sense that foreigners were taking jobs or that foreigners were to blame. As so clear from the debate on foreigners, inter alia in Britain, sentiments normally override facts and figures. These sentiments can be heard rumbling in Iceland but have so far not flourished.

Although the economy has been growing since 2011 following the sharp downturn the previous years and is now booming the discontent is still palpable. Very much directed towards politicians based on a sense of cronyism and the sense that politicians, especially from the old parties, are there to guard and aid special interests such as the fishing industry and wealthy individuals with political ties.

Gunnlaugsson with his Panama connections was ousted. But both Bjarni Benediktsson and Ólöf Nordal his deputy chairman, named in the Panama Papers, have brushed it off easily. Nordal was linked to Panama through her husband, working for Alcoa, but claimed the company was just an old story. Benediktsson owned an offshore company related to failed investments in Dubai and also claimed it was an old story, causing remarkably little curiosity and coverage in Iceland.

The left government, in power 2009 to 2013, did in many ways tackle the ever-present cronyism in Iceland by using stringent criteria and gender balance for hiring people on boards, leading jobs in the public sector etc. Yet, it earned little gratitude for this. One of the most noticeable changes when the Progressive-Independence coalition came to power in 2013 was its reverting back to the bad habits of former times. Over the last few years sales of certain state assets have also raised some questions. Sales of the two now state-owned banks and other state assets on the agenda these will again test the Icelandic hang to cronyism and corruption.

The underlying discontent in booming Iceland possibly shows that it’s not only the economy that matters. But it also shows that after a severe shock it takes time for the political powers to gain trust. The coming four years will be a further test. As one voter said: “I would have liked to see all parties acknowledge the events in 2008 and come forth with a plan as to how to how to avoid the kind of political behaviour that led to the 2008 demise – but there was no such comprehensive plan.”

– – –

The new Alþingi: The new gathering of MPs has a greater number of women than ever before: 30 MPs of 63 are women. The tree youngest MPs are born in 1990, the oldest, and newly elected, is born in 1948. Katrín Jakobsdóttir, born in 1976, is one of seven MPs voted into Alþingi before 2008. Following the three last elections a large number of MPs have left and new ones coming in. As prime minister Sigurður Ingi Jóhannsson said it’s good to get new energy into the austere halls of Alþingi but it’s equally worrying to lose competence, knowledge and experience: 22 have never sat in Parliament before, ten are new but with some parliamentary experience, in total 32 out of 63 MPs.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.