Archive for the ‘Uncategorised’ Category

No end to the Greek government’s relentless persecution of ELSTAT staff

In spite of earlier promises to the Eurogroup the Greek government continues to persecute former head of ELSTAT Andreas Georgiou and two of his former senior staff. As long as the never-ending prosecutions continue the Greek government cannot claim it is seriously committed to turn the country around. By continuing these persecutions the Greek government is clinging to the story that the fraudulent statistics from around 2000 to 2009 are the correct ones, thereby in effect presenting the 2010 revisions as criminal misreporting. Thus, the Eurogroup and other international partners should refuse to cooperate with the Greek government as long as these trials continue.

In spite of earlier acquittals time and again, Greek authorities keep finding new ways to prosecute the former head of ELSTAT. The latest development happened last week, July 18 and 19. As at the trial in May, there was a shouting and insulting mob of around thirty people present in court at the trial on July 18 when Georgiou was being tried for alleged violation of duty. The mob was clearly cheering on the accusation witnesses in a disturbing way; again, something that would be unthinkable in any civilised country.

On July 19, the Chief Prosecutor of the Greek Supreme Court proposed yet again to annul the acquittal of Georgiou and two senior ELSTAT staff for allegedly intentionally inflating the 2009 government deficit and causing Greece a damage of €171bn.

Mob trial

After being unanimously found innocent of charges of violation of duty in December last year by a panel of three judges, as the trial prosecutor had recommended, this acquittal was annulled by another prosecutor. This is how this farce and mockery of justice has been kept going: acquittals are annulled and on goes the persecution.

This trial will now continue on 31 July when judgement is also expected – and it can be fully expected that Georgiou will be found guilty.

This report from Pastras Times gives an idea of the atmosphere at the trial: The professor [Z. Georganda] argued that from the data she has at her disposal, she considers that the 2009 government deficit was around 4 to 5% [of GDP] – a statement, which ignited the reaction of the audience that began applauding and shouting: “Traitors” “Hang them on Syntagma square”… The witness continued her point arguing that Greece had one of the lowest deficits “but we could and we were paying our debts because there was economic activity. Georgiou led the country to prolonged recession.” Ms. Georganda said characteristically, causing the audience to explode anew.

A pattern over six years: acquittals followed by repeated prosecution

As everyone who knows the story of the discoveries made in 2009 and 2010 of the Greek state statistics Georganda’s arguments are a total travesty of the facts, a story earlier recounted on Icelog (here the long story of the fraudulent stats and the revisions in 2010; here some blogs on the course of this horrendous saga).

July 19 was the deadline for the Chief Prosecutor of the Supreme Court, Xeni Demetriou to make a proposal for annulment of the decision of the Appeals Court Council to acquit Georgiou and two former senior ELSTAT staff of the charge of making false statements about the 2009 government deficit and causing Greece a damage of €171bn. Demitrou opted to propose to annul the acquittal decision.

The Criminal Section of the Supreme Court will now consider her proposal for the annulment of the acquittal. If the latter agrees with the proposal of the Chief Prosecutor of Greece, the case will be re-examined by the Appeals Court Council. If the Appeals Court Council, under a new composition, then decides to not acquit Georgiou and his colleagues, the three will be subjected to full a trial by the Appeals Court. If convicted they face a sentence of up to life in prison.

This would then be yet another round of the same case: in September 2015, the same Prosecutor of the Supreme Court, then a Deputy Prosecutor, proposed the annulment of the then existing acquittal decision of the Appeals Court Council. In August 2016, the Criminal Section of the Supreme Court agreed to this proposal, which is why the Appeals Court Council re-considered the case.

And so it goes in circles, seemingly until the legal process gets to the “right result” – trial and conviction.

Can the three ELSTAT staff get a fair trial?

Given the fact that the same case goes in circles – with one part of the system agreeing to acquittals, which then are thrown out, in the same case – it can only be concluded that Andreas Georgiou and his two ELSTAT colleagues are indeed being persecuted for fulfilling the standard of EU law, as of course required by Eurostat and other international organisations.

As this saga has been on-going for six years it seems that the three simply cannot get a fair hearing in Greece. This raises serious questions about the rule of law in Greece and the state of human rights there.

At the same time the last chapter in this six-year saga took place now in July, €7.7bn of EU taxpayer funds, a tranche of EU and IMF funds for Greece, was paid out. This, inter alia on the basis of the statistics revised in 2010, for which the Greek state keeps prosecuting the ELSTAT statisticians thereby de facto claiming these statistics were the product of criminal misreporting.

Tsakalotos breaks his promise

As reported earlier on Icelog the Eurogroup has clearly noticed the ELSTAT case: at the Eurogroup meeting of 22 May ECB governor Mario Draghi raised the matter, saying that as agreed earlier, priority should be given to implementing “actions on ELSTAT that have been agreed in the context of the programme. Current and former ELSTAT presidents should be indemnified against all costs arising from legal actions against them and their staff.”

Greek minister of finance Euclid Tsakalotos announced that “On ELSTAT, we are happy for this to become a key deliverable before July.”

In an apparent attempt to appease the Eurogroup, it was announced this week that ELSTAT will pay legal costs for the former ELSTAT employees facing trial. However, the legal provision proposed by the government is wholly inadequate and may actually do more harm than good to Georgiou and his colleagues.

For example, it says that these official statisticians will have to return any funds they get if they are convicted. This is legislating perverse incentives. It is like saying: Convict them otherwise we will have to pay them.

The proposed legislation also puts a very low limit on the amounts that would be covered. In addition, it would not cover costs of legal counsel, costs of interpretation of foreign witnesses, nor would it cover the cost of travel and accommodation of these witnesses when they come to Greece abroad to be defence witnesses for Georgiou. There also seems to be a labyrinthine process for accessing the funds making it unlikely the accused will ever see any reimbursement of cost.

It is thus quite clear from events this week that not only has Tsakalotos broken the promise he gave to Draghi and the Eurogroup in May – he clearly has no intention of keeping it. The question is how long the Eurogroup will tolerate broken promises and the fact that by prosecuting the ELSTAT staff the Greek government does indeed keep portraying the revised statistics as criminal misreporting.

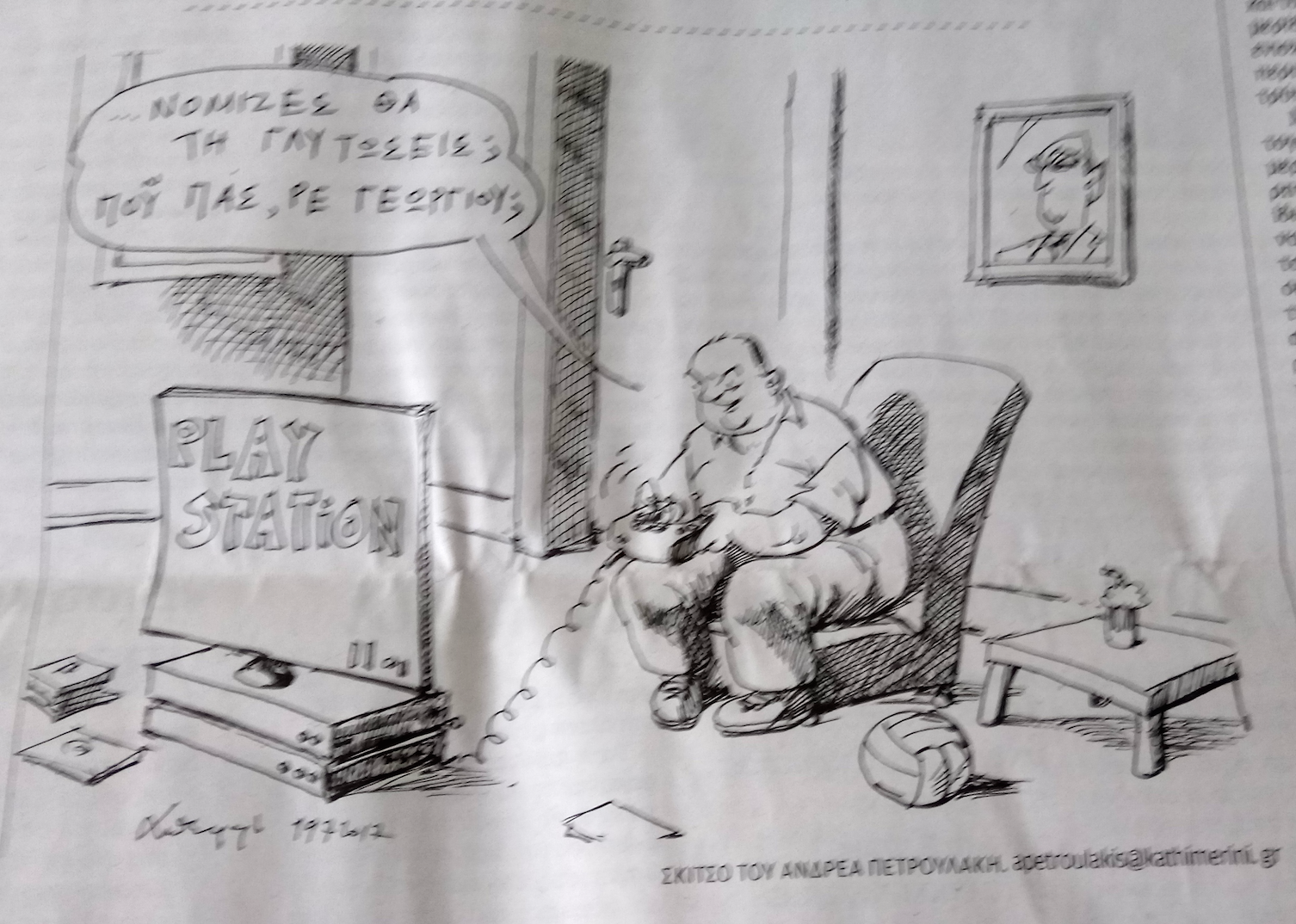

According the Kathimerini‘s cartoonist, the ELSTAT saga is a simple one: New Democracy PM 2004 to 2009 Kostas Karamanlis is unwilling to let go of the persecution – “You thought you would get away? Where do you think you are going, eh Georgiou?”

According the Kathimerini‘s cartoonist, the ELSTAT saga is a simple one: New Democracy PM 2004 to 2009 Kostas Karamanlis is unwilling to let go of the persecution – “You thought you would get away? Where do you think you are going, eh Georgiou?”

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Will special counsel Mueller surprise with Icelandic Russia-related stories?

The Russian Icelandic connections keep stimulating the fantasy. In a recent Bloomberg article Timothy L. O’Brien calls on special counsel Robert Mueller to “check out Iceland.” The facts are indeed elusive but Mueller and his team should be in an ace position to discover whatever there is to discover, via FL Group. If there is no story untold re Russia and Iceland, the unwillingness of the British government to challenge Russian interests is another intriguing Russia-related topic to explore.

“Iceland, Russia and Bayrock – some facts, less fiction” was my recent contribution to the fast growing compendium of articles on potential or alleged connections between nefarious Russian forces and Iceland. The recent Bloomberg article by Timothy L. O’Brien adds nothing new to the topic in terms of tangible facts.

The Russian oligarch Boris Berezovsky was one of those who early on aired the potential connection. Already in 2009, in a Sky interview that O’Brien mentions, Berezovsky made sweeping comments but gave no concrete evidence, as can be heard here in the seven minutes long interview.

What however Berezovsky says regarding London, the dirty money pouring into London is correct. That flow has been going on for a long time and will no doubt continue: it doesn’t seem to matter who is in power in Britain, the door to Russian money and dirty inflow in general is always open, serviced by the big banks and the enablers, such as accountants and lawyers, operating in London.

What Berezovsky really said

Asked how Putin and the oligarchs operated, Berezovsky said they bought assets all over the world but also took on a lot of debt. “They took a lot of credit from the banks and so they were not able to pay that back. And the best example is definitely Iceland. And you remember when lets say three months ago Russian government declared that they would help Iceland. And Russia is so strong that they’re able to help even a member of Nato. And their trick is very simple because Russian let’s say top level bureaucrats like Putin, like others and oligarchs together they created system how to operate on the West. How to use this fantastic money to buy assets and so and so. They found this very clever solution. They took a country and bought the country, which is member of Nato, which is not a member of EU. It means that regulation is different. They put a lot of money, dirty money in general, yeah.”

When asked further if Russians were buying high-end property in London with dirty money Berezovsky said this was indeed the case, all done to gain power: “The example which I gave you. As far as Iceland is concerned just confirmed realistically that Putin and his cronies made absolutely dirty money and tried to invest their money all over the world including Britain.”

This is very much Berezovsky but hardly a clear exposé. Exactly what the connection was, through the banks or the country as a whole isn’t clear. Sadly, Berezovsky died in 2013, under what some see as mysterious circumstances, others consider it a suicide. Incidentally, Berezovsky’s death is one of fourteen deaths in the UK involving Russians, enablers to Russian oligarchs or others with some Russian ties, recently investigated in four articles by Buzzfeed.

The funding of the Icelandic banks – yet again

In his Bloomberg article O’Brien visits the topic of the funding of the Icelandic banks. As I mentioned in my previous Russia blog, the rumours regarding the Russian Icelandic connections and the funding of the Icelandic banks were put to rest with the report of the Special Investigative Commission, SIC. The report analysed the funding the banks sought on international markets, from big banks that then turned into creditors when the banks failed.

O’Brien’s quotes Eva Joly the French investigative judge, now an MEP, who advised Icelandic authorities when they were taking the first steps towards investigating the operations of the then failed banks. Joly says that the Russian question should be asked. “There was a huge amount of money that came into these banks that wasn’t entirely explained by central bank lending,” Joly is quoted as saying, adding “Only Mafia-like groups fill a gap like that.”

I’m not sure where the misunderstanding crept in but of course the Icelandic central bank was not funding the Icelandic banks. As the SIC report clearly showed, the Icelandic banks, as most other banks, sought and found easy funding by issuing bonds abroad at the time when markets were flooded by cheap money. Prosecutor Ólafur Hauksson, who has been in charge of the nine-year banking investigations in Iceland, says to O’Brien that he and his team have not seen any evidence of money laundering but adds that the Icelandic investigations have not focused on international money flows via the banks.

As I pointed out in my earlier Russia blog, the Jody Kriss evidence, from court documents in his proceedings against Bayrock, the company connected to president Donald Trump, is again inconclusive. Something that Kriss himself points out; Kriss is quoting rumours and has nothing more to add to them.

Why and how would money have been laundered through Icelandic banks?

The main purpose of money laundering is to provide illicit money with licit origin. Money laundering in big banks like HSBC, Deutsche Bank and Wachovia is well documented and in general, patterns of money laundering are well established. The Russian Icelandic story will not be any better by repeating the scanty indications. We could turn the story around and ask: if the banks were really used by Russians or any other organized crime how would they have done it?

One pattern is so-called back-to-back loans, i.e. illicit money is deposited in a bank (which then ignores “know your customer” regulation) but taken out as a loan issued by that bank. That gives these funds a legitimate origin; they are now a loan. As far as I understand, there are no sign of this pattern in any of the Icelandic banks.

When Wachovia laundered money for Mexican drug lords cash was deposited with forex exchanges, doing business with Wachovia. The bank brought the funds to Wachovia branches in the US, either via wire transfers, travellers’ cheques or as part of the bank’s cash-moving operations. When the funds were then made available to the drug lords again in Mexico, it seemed as if the money was coming from the US, enough to give the illegitimate funds a legitimate sheen. Nothing like these operations was part of what the Icelandic banks were doing.

Money laundering outside the banks?

There might of course have been other ways of laundering money but again the question is from where to where. As I mentioned in my Russia blog, FL Group, the company connected to the Bayrock story, was short-lived but attracted and lost a spectacular amount of money. As did other Icelandic companies, which have since failed: there could be potential patterns of money laundering there though again there are no Russians in sight (except for Bayrock) – or simply examples of disastrously bad management.

Russians, or anyone else, certainly would not need Icelandic banks to move funds for example into the UK – the big banks were willing to and able to do it, as can be seen from the oligarchs and others with shady funds buying property in London. It was eye-opening to join one of the London tours organised by Kleptocracy Tours and see the various spectacular properties owned by Russian oligarchs here in London.

The Magnitsky Act was introduced in the US in 2012 but is only finding its way into UK law this year in the Criminal Finances Bill, meant to enable asset freezing and denying visa to foreign officials known to be corrupt and having violated human rights.

The Icelandic banks – the most investigated banks

There were indeed real connections to Russians in the Icelandic banks as I listed in my previous Russia blog. In addition, Kaupthing financed the super yacht Serene for Yuri Shefler with a loan of €79.5m according to a leaked overview of Kauthing lending, from September 2008. These customers were among Kaupthing non-Russian high-flying London customers, mostly clients in Kaupthing Luxembourg, such as Alshair Fiyaz, Simon Halabi, Mike Ashley and Robert and Vincent Tchenguiz.

None of the tangible evidence corroborates the story of the Icelandic banks being some gigantic Russian money laundering machine. That said, I have heard from investigators who claim they are about to unearth more material.

In the meantime we should not forget that Iceland has diligently been prosecuting bankers for financial assistance, breach of fiduciary duty and market manipulation – almost thirty bankers and others close to the banks have been sentenced to prison. Now that 2008 investigations are drawing to a close in Iceland, four Barclays bankers are facing charges in London, the first SFO case related to events in 2008, in a case very similar to one of the Icelandic cases, as I have pointed out earlier.

Exactly because the Icelandic banks have been so thoroughly investigated and so much is known about them, their clients etc., it is difficult to imagine there are humongous stories there waiting to be told. But perhaps Robert Mueller and his team will surprise us.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

The Icelandic al Thani case and the British al Thani / Barclays case

Prosecuting big banks and senior bankers is hard for many reasons: they hire big name lawyers that fight tooth and nail, with delays, deviations and imaginable and unimaginable obstructions of all sorts. PR firms are hired to deviate and create smoke and mirrors. And some journalists seem easily to identify with the pillars of financial society, even talking about “victimless crime.” All of this springs to mind regarding the SFO charges against John Varley former CEO of Barclays and three senior managers – where an Icelandic parallel can possibly throw some light on the few facts in the case of Varley e.al.

In the summer of 2008, as liquidity was tight for many banks, two high-flying banks in the London business community, Barclays and Kaupthing, were struggling. Both sought salvation from Qatari investors. Not the same investors though the name al Thani, a ruling clan in the dessert state of Qatar, figures in both investment stories.

In 2012 as the Icelandic Office of the Special Prosecutor, OSP, brought charges against three Kaupthing managers and the bank’s second largest investor Ólafur Ólafsson, related to Qatari investment in Kaupthing in September 2008, the British Serious Fraud Office, SFO, was just about to start an investigation into the 2008 Qatari investment in Barclays.

In 2015 the four Icelanders were sentenced to 4 to 5 1/2 years in prison for fraudulent lending and market manipulation (see my overview here). SFO is now bringing ex CEO John Varley and three senior Barclays bankers to court on July 3 on the basis of similar charges. As the first UK bankers are charged for actions during the 2008 crisis such investigations are coming to a close in Iceland where almost 30 bankers and others have been sentenced since 2011 in crisis-related cases.

The Kaupthing charges in 2012 filled fourteen pages, explaining the alleged criminal deeds. That is sadly not the case with the SFO Barclays charges: only the alleged offences are made public. Given the similarities of the two cases it is however tempting to use the Icelandic case to throw some light on the British case.

SFO is scarred after earlier mishaps. But is the SFO investigation perhaps just a complete misunderstanding and a “victimless crime” as BBC business editor Simon Jack alleges? That is certainly what the charged bankers would like us to believe but in cases of financial assistance and market manipulation, everyone acting in the financial market is the victim.

These crimes wholly undermine the level playing field regulators strive to create. Do we want to live in a society where it is acceptable to commit a crime if it saves a certain amount of taxpayers’ money but ends up destroying the market supposedly a foundation of our economy?

The Barclays and Kaupthing charges – basically the same

When the Icelandic state prosecutor brings charges the underlying writ can be made public three days later. The writ carefully explains the alleged criminal deeds, quoting evidence that underpins the charges. Thus, Icelanders knew from 2012 the underlying deeds in the Icelandic case, called the al Thani case after the investor Sheikh Mohammed bin Khalifa al Thani who was not charged.

As to the SFO charges in the Barclays case we only know this:

Conspiracy to commit fraud by false representation in relation to the June 2008 capital raising, contrary to s1 and s2 of the Fraud Act 2006 and s1(1) of the Criminal Law Act 1977 – Barclays Plc, John Varley, Roger Jenkins, Thomas Kalaris and Richard Boath.

Conspiracy to commit fraud by false representation in relation to the October 2008 capital raising, contrary to s1 and s2 of the Fraud Act 2006 and s1(1) of the Criminal Law Act 1977 – Barclays Plc, John Varley and Roger Jenkins.

Unlawful financial assistance contrary to s151 of the Companies Act 1985 – Barclays Plc, John Varley and Roger Jenkins.

The Gulf investors named in 2008 were Sheikh Hamad bin Jassim bin Jabr al Thani, Qatar’s prime minister at the time and Sheikh Mansour bin Zayed al-Nahyan of Abu Dhabi. The side deals the bankers are charged for relate to the Qatari part of the investment, i.e. Barclays capital raising arrangements with Qatar Holding LLC, part of Qatar’s sovereign wealth fund and al Thani’s investment vehicle Challenger Universal Ltd and $3bn loan issued by Barclays to the State of Qatar, acting through the Ministry of Economy and Finance in November 2008.

Viewing the Barclays side deals via the Kaupthing case

The Barclays saga is allegedly that apart from the Qatari investments in Barclays in June and October 2008, in total £6.1bn, there were two side deals, allegedly financial assistance: Barclays promised to pay £322m to Qatari investors, apparently fee for helping Barclays with business development in the Gulf; in November 2008, Barclays agreed to issue a loan of $3bn to the State of Qatar, allegedly fitting the funds prime minister Sheikh al Thani invested, according to The Daily Telegraph.

Thus it seems the Barclays bankers (all four following the June 2008 investment, two of them following the October investment) were allegedly misleading the markets, i.e. market manipulation, when they commented on the two Qatari investments.

If we take cue from the Icelandic al Thani case it is most likely that the Barclays managers begged and pestered the Gulf investors, known for their deep pockets, to invest.

In the al Thani case, the Abu Dhabi sovereign wealth fund had earlier considered buying Kaupthing shares but thought the price was too high. Kaupthing then wooed the Qatari investors with some good offers.

What Kaupthing promised was a “risk-free” loan, a classic Kaupthing special offer to special clients, to place as an investment in Kaupthing. In other words, there was never any money coming into Kaupthing as an investment. It was just money merry-go-round from one Kaupthing account to another: funds going out as a loan and coming back as an investment. In addition, the investors got a loan of $50m directly into their pockets, defined as pre-paid profit.

Barclays hardly made such a crude offer to the Qatari investors but the £322m fee leads the thought to the pre-paid profit in the Kaupthing saga; the Barclays fee could allegedly be defined as pre-payment for services-to-come.

The $3bn loan to the state of Qatar is intriguing, given that the state of Qatar is and the finances of its ruling family have allegedly often seemed closely connected.

What we don’t know regarding the Barclays side deals

The September 2008 Qatari investment in Kaupthing figured in the 2010 report of the Special Investigative Commission, SIC, a report that thoroughly explained and mapped the operations of the Icelandic banks up to the 2008 collapse. The criminal case added details to the SIC saga. It is for example clear that Kaupthing didn’t really expect the Gulf investors to pay back the investment but handed them $50m right away.

Little is yet known about the details of the alleged Barclays side deals. How were the covenants for the $3bn loan? Has this loan been repaid or is it still on Barclays books? And was the service for the £322m ever carried out? Was there any specification as to what Barclays was paying for? Why were these services apparently pre-paid instead of being paid against an invoice after the services had been carried out?

These are some of the things we would need to know in order to assess the side deals and their context and connections to the Qatari investment in Barclays. Clearly, the SFO knows and this will no doubt be part of the coming court case.

The whiff of Qatari investors and how it touches Deutsche Bank

The Kaupthing resolution committee went after the Qatari investors to recover the loans, threatening them with legal proceedings. Investigators from the Office of the Special Prosecutor did question the investors.

According to Icelog sources, the Qatari investors were adamant about clarifying the situation both with Kaupthing and the OSP. The understanding was that the investors were worried about their reputation. They did in the end reach a settlement with the Kaupthing resolution committee as Kaupthing announced in 2013.

These two investment sagas do however leave a certain whiff. In August last year, when it transpired that Qatari investors had invested in troubled Deutsche Bank I sent a query to Deutsche’s spokesman asking if the bank was possibly lending the investors money. I got a stern reply that I was hinting at Deutsche committing a legal offense (well, as if Deutsche had not been found to have rigged markets, assisted in money laundering etc) but was later assured that no, Deutsche had not given any financial assistance to its Qatari investors, no side deals related to their investment in the bank.

Companies don’t commit crimes – people do

Although certainly not the only one, Barclays is a bank with a long register of recent financial sins, inter alia: in 2012 it paid a fine of £290m for Libor manipulation; in 2015 it paid £2.3bn for rigging FX markets and £72m to settle money laundering offenses.

As to lessons learnt: this spring, it turned out that Barclays CEO Jes Staley, has broken whistleblower-rules by trying to unmask a Barclays whistleblower. CEOs have been remarkably short lived at Barclays since Varley left in 2010: his successor Bob Diamond was forced out in 2012, replaced by Antony Jenkins who had to leave in 2015, followed by Jes Staley.

In spite of Barclays being fined for matters, which are a criminal offence, the SFO has treated these crimes (and similar offences in many other banks) as crimes not committed by people but companies, i.e. no Barclays bankers have been charged… until now.

After all, continuously breaking the law in multiple offences over a decade, under various CEOs indicates that something is seriously wrong at Barclays (and in many other big banks). Normally, criminals are not allowed just to pay their way out of criminal deeds. In the case of banking fines banks have actually paid with funds accrued by criminal offences. Ironically, banks pay fines with shareholders’ money and most often, senior managers have not even taken a pay cut following costs arising from their deeds.

In all its unknown details the Barclays case is no doubt far from simple. But compared to FX or Libor rigging, it is manageable, its focus being the two investments, in June and October 2008, the £322m fee and the November 2008 loan of $3bn.

The BBC is not amused… at SFO charges

Instead of seeing the merit in this heroic effort by the SFO BBC’s business editor Simon Jack is greatly worried, after talking to what only appear to be Barclays insiders. There is no voice in his comment expressing any sympathy with the rule of law rather than the culpable bankers.

Jack asks: Why, over the past decade, has the SFO been at its most dogged in the pursuit of a bank that DIDN’T require a taxpayer bailout? In fact, it was Barclays’ very efforts to SPARE the taxpayer that gave rise to this investigation.

This is of course exactly the question and answer one would hear from the charged bankers but it is unexpected to see this argument voiced by the BBC business editor on a BBC website as an argument against an investigation. In the Icelandic al Thani case, those charged and eventually sentenced also found it grossly unfair that they were charged for saving the bank… with criminal means.

Jack’s reasoning seems to justify a criminal act if the goal is deemed as positive and good for society. One thing for sure, such a society is not optimal for running a company – the healthiest and most competitive business environment surely is one where the rule of law can be taken for granted.

Another underlying assumption here is that the Barclays management sought to safe the bank by criminal means in order to spare the taxpayer the expense of a bailout. Perhaps a lovely thought but a highly unlikely one. There were plenty of commentaries in 2008 pointing out that what really drove Barclays’ John Varley and his trusted lieutenants hard to seek investors was their sincere wish to avoid any meddling into Barclays bonuses etc.

Is the alleged Barclays fraud a “victimless crime”?

It’s worth remembering that taxpayers didn’t bail out Barclays and small shareholders didn’t suffer the massive losses that those of RBS and Lloyds did. One former Barclays insider said that if there was a crime then it was “victimless” and you could argue that Barclays – and its executives – did taxpayers and its own shareholders a massive favour, writes Jack.

It comes as no surprise that “one former Barclays insider” would claim that saving a bank, even by breaking the law, is just fine and actually a good deed. For anyone who is not a Barclays insider it is a profound and shocking misunderstanding that a financial crime like the Barclays directors allegedly committed is victimless just because no one is walking out of Barclays with a tangible loss or the victims can’t be caught on a photo.

We don’t know in detail how Barclays was managed, there is no British SIC report. So we don’t know if the $3bn loan has been paid back. If it was not repaid or had abnormally weak covenants it makes all Barclays clients a victim because they will have had to pay, in one way or another, for that loan.

Even if the loan was normal and has been paid a bank that uses criminal deeds to survive turns the whole society into the victims of its criminal deeds: financial assistance and market manipulation skew the business environment, making the level playing field very uneven.

Pushing Jack’s argument further it could be conclude that the RBS and Lloyds managers at the time did evil by not using criminal deeds to save their banks, compared to the saintly Barclays managers who did – a truly absurd statement.

Charging those at the top compared to charging only the “arms” of the top managers, i.e. those who carry out the commands of senior managers, shows that the SFO understands how a company like Barclays functions; making side deals like these is not decided by low-level staff. Further, again with an Icelandic cue, it is highly likely that the SFO has tangible evidence like emails, recordings of phone calls etc. implicating the four charged managers.

The Barclays battles to come

Criminal investigations are partly to investigate what happened, partly a deterrent and partly to teach a lesson. If the buck stops at the top, charging those at the top is the right thing to do when these managers orchestrate potentially criminal actions.

But those at the top have ample means to defend themselves. Icelandic authorities now have a considerable experience in prosecuting alleged crimes committed by bankers and other wealthy individuals.

And Icelanders also have an experience in observing how wealthy defendants react: how they try to manipulate the media via their own websites and/or social media, by paying PR firms to orchestrate their narrative, how their lawyers or other pillars of society, strongly identifying with the defendants, continue to refute sentences outside of the court room etc. And how judges, prosecutors and other authorities come under ferocious attack from the charged or sentenced individuals and their errand boys.

All of this is nothing new; we have seen this pattern in other cases where wealth clashes with the law. And since this is nothing new, it is stunning to read such a blatant apology for the charged Barclays managers on the website of the British public broadcaster. Even if the SFO prosecution against the Barclays bankers were to fail apologising the bankers ignores the general interest of society in maintaining a rule of law for everyone without any grace and favour for wealth and social standing.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Greece – still failing the ELSTAT test

Greek authorities have not yet dropped the wholly unfounded criminal cases against former head of ELSTAT Andreas Georgiou. As expressed earlier on Icelog, the ELSTAT saga is a test if Greece is beholden to a corrupt past or trying to amend its ways. So far, no amendment. And interestingly, Greece is again stalling in terms of improving the economy and disbursement of €7bn from the Eurozone are being withheld.

The case of Georgiou and two ELSTAT colleagues was again up in court in Athens on Friday, Again acquitted but in this saga, where everything goes in circles and nothing is brought to an end, it is far from certain if this really is the end. There is, yet again the distinct possibility that the Chief Prosecutor of the Supreme Court will again reverse the acquittal, as in September 2015.

Another part of this case – for some reason it has been split up and the two cases are tried separately – came up this Monday, 29 May.

Also a new criminal investigation about exactly the same issue, ordered last September by the same Chief Prosecutor, could theoretically continue and keep the case going for years to come.

Leaked minutes from the Eurogroup meeting 22 May shows that ECB governor Mario Draghi brought the ELSTAT case up right at the beginning of the meeting, asking that, as agreed earlier, priority should be given to implementing “actions on ELSTAT that have been agreed in the context of the programme. Current and former ELSTAT presidents should be indemnified against all costs arising from legal actions against them and their staff.”

Greek minister of finance Euclid Tsakalotos said that “On ELSTAT, we are happy for this to become a key deliverable before July.”

The Eurogroup has clearly noticed the ELSTAT case. It remains to be seen if Tsakalotos does indeed deliver before July. I’m told that there is a real opposition in some quarters to give earlier ELSTAT president indemnity against cost. Unless he and his staff is included this action does not have the intended effect. Hopefully, Draghi and others in the Eurogroup will not lose sight of this issue.

Sir, As you reported on May 22 (FT.com), the eurogroup failed to complete the review of the economic programme with Greece and enable the disbursement of €7bn of Eurozone member taxpayer money to Greece. Negotiations are continuing. Meanwhile, on May 29, Andreas Georgiou again went on trial for violation of duty while he was president of the Hellenic Statistical Authority (Elstat) from August 2010 to August 2015 (The Big Read, December 30, 2016).

These two strands should be linked, but to date have not been. The eurogroup and associated European organizations (the European Stability Mechanism, the European Commission and the European Central Bank) have not established the appropriate linkage.

Mr Georgiou and senior colleagues of his at Elstat are being prosecuted for doing their job in producing honest statistics about Greece’s fiscal condition for 2009, before the start of the first Greek programme, and during the first five years of programmes. Their work is central to the Greek economic reform efforts. It was based on European standards for statistical data quality. Successive Greek governments have committed to comply with those standards and to defend the professional independence of Elstat. The current government and several previous governments have failed to live up to these commitments.

We the undersigned call on the European authorities not to complete the programme review with Greece until and unless the Greek government declares publicly in writing that the statistics compiled by Mr Georgiou and his colleagues at Elstat were accurate and that they were produced and disseminated using appropriate processes and procedures based on European standards.

Michel Camdessus Paris, France; José Manuel Campa Madrid, Spain; Edwin M. Truman Washington, DC, US; Gertrude Trumpel-Gugerell Vienna, Austria; Nicolas Véron Washington, DC, US and Paris, France; Geoffrey Woglom Amherst, MA, US; Edmond Alphandéry Paris, France; Paul Armington Washington, DC, US; Ruthanne Deutsch Washington, DC, US; Robert D Kyle Washington, DC, US; Barry D Nussbaum Annandale, VA, US; Christopher Smart Boston, MA, US; Peter H. Sturm Washington, DC, US; Stephanie Tsantes Lewes, DE, US; Ronald L. Wasserstein Springfield, VA, US; Charles Wyplosz Geneva, Switzerland; Jeromin Zettlemeyer Washington, DC, US

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Iceland, Russia and Bayrock – some facts, less fiction

Contacts between Iceland and Russia have for almost two decades been a source of speculations, some more fancifully than others. The speculations have now again surfaced in the international media following the focus on US president Donald Trump and his Russian ties: part of that story involves his connections with Bayrock where two Icelandic companies, FL Group and Novator, are mentioned. Contrary to the rumours at the time, Icelandic expansion abroad up to the banking collapse in 2008 can be explained by less sensational sources than Russian money – but there are some Russian ties to Iceland.

“We have never seen businessmen who operate like the Icelandic ones, throwing money around as if funding was never a problem,” an experienced Danish business journalist said to me in 2004. From around 2002 to the Icelandic banking collapse in October 2008, the Icelandic banks and their largest shareholders attracted attention abroad for audacious deals.

The rumours of Russian links to the Icelandic boom quickly surfaced as journalists and others sought to explain how a tiny country of around 320.000 people could finance large business deals by Icelandic businesses abroad. The owners of one of Iceland’s largest banks, Landsbanki, father and son Björgólfur Guðmundsson and Björgólfur Thor Björgólfsson, had indeed become rich in Saint Petersburg in the 1990s.

The unequivocal answer on how the foreign expansion of Icelandic banks and businesses was funded came in the Special Investigative Commission Report, SICR, in 2010: the funding came from Icelandic and international banks; the Icelandic banks found easy funding on international markets, the protagonist were at the same time the banks’ largest shareholders and their largest borrowers.

The rumours of Russian connections have surfaced again due to the Bayrock saga involving US president Donald Trump and his relations to Russia and Russian mobsters. Time to look at the Icelandic chapter in the Bayrock saga and Russian Icelandic links.

The Bayrock saga

By now, there is hardly a media company in the world that has not paid some attention to Donald Trump and Bayrock, with a mention of the Icelandic FL Group and the Russian money in Icelandic banks and businesses. The short version of that saga is the following:

Tevfik Arif, born in Kazakhstan during the Soviet era, was a state-employed economist who turned to hotel development in Turkey in the 1990s before moving into New York property development where he founded Bayrock in 2001. As with many real estate companies Bayrock’s structure was highly complex with myriad companies and shell companies, on- and offshore.

Arif hired a Russian to run Bayrock. Felix Sater or Satter was born in Russia in but moved to New York as youngster with his family. In 1991 Sater was sentenced to prison for a bar brawl cutting up the face of his adversary with a broken glass. Having admitted to security fraud in cohort with some New York Mafia families in 1998 he was eventually found guilty but apparently got a lenient sentence in return for becoming an informant for the law enforcement.

In 2003, Arif and Sater were introduced to a flamboyant property developer by the name of Donald Trump, already a hot name in New York. One of their joint projects was the Trump Soho. The Trump connection did attract media attention. Apparently following a New York Times profile of Sater in December 2007, unearthing his criminal records, Arif dismissed Sater in 2008.

Bayrock and FL Group

By then, another scheme was brewing and that is where the Icelandic FL Group enters the Bayrock and Trump story. This part of the story has surfaced in court cases, still ongoing, where two ex-Bayrock employees, Jody Kriss and Michael Ejekam, are suing Bayrock for cheating them of profit inter alia from the Trump SoHo deal.

Their story details complicated hidden agreements whereby Arif and Sater, according to Kriss and Ejekam, essentially conspired to skim off profit from Bayrock, cheating everyone who entered an agreement with them. According to the story told in the court documents (see inter alia here) Bayrock entered an agreement with FL Group in May 2007: for providing a loan of $50m FL Group would get 62% of the total profits from four Bayrock entities, expected to generate a profit of around $227.5m.

The loan arrangement with FL Group did not make a great financial sense for Bayrock, again according to Kriss and Ejekam, but it was part of Arif and Sater’s scheme to cheat investors as well the US tax authorities. When Kriss complained to Sater that the $50m loan from FL Group was not distributed as agreed, Sater “made him (Kriss) an offer he couldn’t refuse: either take $500,000, keep quiet and leave all the rest of his money behind, or make trouble and be killed.” – Given Sater’s criminal record and threats he had made to another Bayrock partner Kriss left Bayrock.

The short and intense FL saga and its record losses

FL Group was one of the companies that formed the Icelandic boom. Out of many financial follies in pre-crash Iceland the FL Group saga was one of the most headline-creating. In 2002 Jón Ásgeir Jóhannesson, of Baugur fame, bought 20% in the listed air carrier Flugleiðir. In 2004 he teamed up with Hannes Smárason who with a degree from the MIT and four years at McKinsey in Boston had a stellar CV.

Smárason was first on the board until he became a CEO in October 2005. The duo oversaw the take-over of Flugleiðir, sold off assets and turned the company into an investment company, FL Group; inter alia FL Group was for a short while the largest shareholder in EasyJet.

In spring 2007, a group of investors led by Jóhannesson became the largest shareholder in Iceland’s third largest bank, Glitnir. Their Glitnir holding was through FL Group, consequently the bank’s largest shareholder.

At the beginning of 2007, the FL Group debt with the Icelandic banks amounted to almost €600m but had risen to €1.1bn in October 2008. Interestingly, its debt to Glitnir rose by almost 800%. As mentioned above, Jóhannesson and his business partners, among them FL Group, became Glitnir’s largest shareholder in spring 2007, following the pattern that the banks’ largest shareholders were also their largest borrowers.

FL Group – folly or a classic “pump and dump”?

By the end of 2007, 26 months after Hannes Smárason became CEO, FL Group had set an Icelandic record in losses: ISK63bn, now €660m, ten times the previous record, from 2006, incidentally set by a media company controlled by Jóhannesson.

Facing these stunning losses Smárason left FL Group in December 2007. The story goes that at the shareholders’ meeting where his departure was announced he left the room waving, saying “See you in the next war, guys” (In Icelandic: “Sjáumst í næsta stríði, strákar).

There are endless stories of staggering cost and insane spending related to the FL Group boom and bust. Interestingly, a large part of the losses stemmed from consultancy cost for projects that never materialised. Smaller investors lost heavily and in hindsight the question arises if the FL saga was a folly or some version of a “pump and dump.” Smárason was charged with embezzlement in 2013, acquitted in Reykjavík District Court but the State Prosecutor’s appeal was thrown out of the Supreme Court due to the Prosecutor’s mistakes.

FL Group never recovered from the losses and was delisted in the spring of 2008 and its name changed to Stoðir. FL Group never went into bankruptcy but its debt was written off. A group of earlier FL Group managers (Smárason is not one of them) now owns over 50% of Stoðir.

FL Group and the Icelandic Bayrock

Part of FL Group’s eye-watering losses was the Bayrock adventure. FL Group set up a company in Iceland, FL Bayrock Holdco, financed by the Icelandic mother company. Already in 2008 the FL Group Bayrock was a loss-making enterprise, its three FL Bayrock US companies were written off with losses amounting to ISK17.6bn, now €157m. When the Icelandic FL Bayrock finally failed in January 2014 Stoðir (earlier FL Group) was more or less the only creditor, its claims amounting to ISK13bn; no assets were found.

According to the Kriss-Ejekam story, FL Group willingly and knowingly took part in a scam. When I approached a person close to FL Group, he maintained the investment had not been a scam but just one of many loss-making investments, not even a major investment, compared to what FL Group was doing at the time.

An FL Group investor told me that he had never even heard of the Bayrock investment until the Trump-related Bayrock stories surfaced. He expressed surprise that such a large investment could have been made without the knowledge of anyone except the CEO and managers. He added however that this was perhaps indicative of the problems in FL Group: managers making utterly insane and ill-informed decisions leading to the record losses.

Bayrock and Novator

Another Icelandic company, mentioned in the Kriss-Ejekam case is Novator, which was offered to participate in Bayrock. There is a whole galaxy of Novator companies, inter alia 19 in Luxembourg, encompassing assets and businesses of Björgólfur Thor Björgólfsson.

This, according to court documents (emphasis mine):

During the early FL negotiations, Bayrock was approached by Novator, an Icelandic competitor of FL’s, which promised to go into the same partnership with Bayrock as FL was contemplating, and at better terms. Arif and Satter told Kriss that this would not be possible, because the money behind these companies was mostly Russian and the Russians behind FL were in favor with Putin, but the Russians behind Novator were not, and so they had to deal with FL. Whether or not this was true and what further Russian involvement existed must await disclosure.

This is the clause that has yet again fuelled speculations of Russian dirty money in the Icelandic banks and Icelandic companies. As stated in the last sentence this is however all pure speculation.

The story from the Novator side is a different one. In an email answer to my query, the spokeswoman for Björgólfsson wrote that Bayrock approached Novator Properties, which considered the project far from attractive. Following some due diligence Novator concluded that the people involved were not appealing partners, which led Novator to decline the invitation to participate.

The origin of rumours of corrupt Russian connections to Iceland

Towards the end of 2002 the largest Icelandic banks and their main shareholders were already attracting foreign media attention. Euromoney (paywall) raised “Questions over Landsbanki’s new shareholder” in November 2002 focusing on the story of the father and son Björgólfur Guðmundsson and Björgólfur Thor Björgólfsson, who with their business partner Magnús Þorsteinsson struck gold in Saint Petersburg in the 1990s and were now set to buy over 40% of privatised Landsbanki.

The two businessmen, the Brit Bernard Lardner and his Icelandic partner Ingimar Ingimarsson, who in the mid 1990s had hired the three Icelanders to run their joint Saint Petersburg venture, were less lucky. In 2011 Ingimarsson published a book in Iceland, The Story that Had to be Told, (Sagan sem varð að segja), where he tells his side of the story: how father and son through tricks and bullying took over the Lardner and Ingimarsson venture, essentially the story told in Euromoney in 2002 (see earlier Icelog).

In June 2005, Guardian’s Ian Griffith wrote an article on the Icelandic businessmen Björgólfsson and Jón Ásgeir Jóhannesson, ever more visible in the London business community, asking where the Icelandic “Viking raiders” as they were commonly called got their money from, hinting at Russian mafia money. The quick rise to riches, wrote Griffith, exposed the Icelanders to “the persistent but unsubstantiated whispering that the country’s economic miracle has been funded by Russian mafia money rather than growth and liberalisation.”

As Griffith points out, Björgólfsson and his partners were operating in Saint Petersburg, “the city regarded as the Russian mafia capital. That investment was being made in the drinks sector, seen by the mafia as the industry of choice.

Yet against all the odds, Bravo went from strength to strength.

Other St Petersburg brewing executives were not so fortunate. One was shot dead in his kitchen from the ledge of a fifth-floor window. Another perished in a hail of bullets as he stepped from his Mercedes. And one St Petersburg brewery burned to the ground after a mishap with a welding torch.

But the Bravo business, run by three self-confessed naives, suddenly found itself to be one of Russia’s leading brewers. In under three years it became the fastest-growing brewer in the country. It secured a 17% market share in the St Petersburg region and 7% in the Moscow area. It was selling 2.5m hectolitres of beer a year in 2001 and heading for 4m when Heineken of the Netherlands stepped in to buy it for $400m in 2002. Heineken said one of the reasons for the Bravo purchase was the absence of any corruption.”

Björgólfsson has always vehemently denied stories of his alleged links to the Russian dark forces and Ingimarsson’s story. Billions to Bust and Back, published in 2014, is Björgólfsson’s own story of his life. The book has not been published in Iceland.

The Icelandic miracle exposed: international banks and “favoured clients”

During the Icelandic boom years Griffith was not the only one to question how the tiny economy of tiny Iceland could fund the enormous expansion of Icelandic banks and businesses abroad. The Russian rumours were persistent, some of them originating in the murky London underworld, all to explain this apparently miraculous growth. Most of this coverage was however more fiction than facts (the echo of this is found in my financial thriller, Samhengi hlutanna, which takes place in London and Iceland after the collapse, published in Iceland in 2011; English synopsis.)

The Icelandic Special Investigative Commission Report, SICR, published in April 2010, convincingly answered the question where the money came from: “Access to international financial markets was, for the banks, the principal premise for their big growth,” facilitated by their high credit ratings and Iceland’s membership of the European Economic Area, EEA. As to the largest shareholders the SICR concluded: “The largest owners of all the big banks had abnormally easy access to credit at the banks they owned, apparently in their capacity as owners… in all of the banks, their principal owners were among the largest borrowers.”

The story told in the SICR is how the Icelandic banks essentially ran a double banking system: one for normal bank clients who got loans against sound collaterals and loan contracts with normal covenants – and then another system for what I have called the “favoured clients,” i.e. the largest shareholders and their business partners.

The loans to the “favoured clients” were on very favourable terms, mostly bullet loans extended as needed, often with little or no collateral and light covenants. The consequence was that systematically, these clients profitted but if things went wrong the banks shouldered the losses. – In recent years, some of these abnormally favourable loans have sent around twenty bankers to prison.

The real Russian connections in Iceland

Although the Icelandic expansion abroad can be explained with less exciting facts than Russian Mafia and money laundering, there are a few tangible Russian contacts to Iceland: Vladimir Putin and the Kremlin did show an interest in Iceland at a crucial time, just as in Cyprus in 2013; Alisher Usmanov had ties to Kaupthing; the Danish lawyer Jens Peter Galmond, famous for his Leonid Reiman connections, and his partner Claus Abildstrøm did have Icelandic clients and Mikhail Fridman gets a mention.

At 4pm Monday 6 October 2008 prime minister and leader of the Independence party (conservative) Geir Haarde addressed Icelanders via the media: the government was introducing emergency measures to deal with the banks in an orderly manner. Icelanders sat glued to their tv sets struggling to understand the meaning of it all.

Haarde’s last words, “God bless Iceland,” brought home the severity of the situation. Icelanders had never heard head of government bless the country and never heard of measures like the ones introduced. The speech and the emergency Act it introduced came to be seen as the collapse moment – the three banks were expected to fail and by Wednesday 8 October they had all failed indeed.

An elusive Russian loan offer

The next morning, 7 October 2008 as Icelanders woke up to a failing financial system, the then governor of the Icelandic Central Bank, CBI, Davíð Oddsson, an earlier leader of the Independence Party and prime minister, told the still shocked Icelanders that all would be well: around 7am Victor I. Tatarintsev the Russian ambassador in Iceland had called Oddsson to inform him that the Russian government was willing to lend €4bn to Iceland, bolstering the Icelandic foreign reserves.

According to the CBI press release the loan would be at 30-50bp above Libor and have a maturity of three to four years. Later that day another press release just stated that representatives of the two countries would meet in the coming days to negotiate on “financial issues” – no mention of a loan.

According to Icelog sources, the morning news was hardly out when the CBI heard from news agencies that Russian minister of finance Alexei Kudrin had denied the story of a Russian loan to Iceland; indeed the loan never materialised though some CBI officials did fly out to Moscow a week later.

There have of course been wild speculations as to if the offer was real, why Kremlin was ready to offer the loan and then why Kremlin did, in the end, not stand by that offer.

Judging from Icelog sources it seems no misunderstanding that Tatarintsev mentioned a loan to Oddsson. As to why Kremlin – because that is where the offer did come from – wanted to lend or at least to tease with the offer is less clear though there is no lack of undocumented stories.

One story is that some Russian oligarchs did have money invested in Iceland. Fearing their funds would be inaccessible they pulled some strings but when they realised their funds were not in danger they lost interest in helping Iceland and so did Kremlin. Another explanation is that Kremlin just wanted to tease the West a bit, make as if it was stretching its sphere of interest further west. Yet another story is that a European minister of finance called his Russian counterpart telling him to stay away from Iceland; the European Union, EU would take care of the country.

Iceland found in the end a more conventional source of emergency funding: by 19 November 2008 it had secured $2.1bn loan from the International Monetary Fund, IMF.

Russia, Iceland and Cyprus

In 2013, Russia played the same game with Cyprus: it teased Cyprus with a loan. The difference was however that the Russian offer to Cyprus did not come as a surprise: Russia had long-standing and close political ties to the island. Russian oligarchs and smaller fries had for years made use of Cyprus as a first stop for Russian money out of Russia. At the end of 2011, Russia had lent €2.5bn to Cyprus. However, the crisis lending did not materialise, any more than it had in Iceland (see my Cyprus story).

The international media reported frequently that the EU and the IMF were reluctant to assist Cyprus because these organisations were irritated by the easy access of Russian funds to and through the island’s banks. A classified German report was said to show how Cyprus had been a haven for money laundering (if that report did indeed exist Germans could and should have used the same diligence to check their own Deutsche Bank!)

After the 2008 collapse in Iceland a credible source told me he had seen a US Department of Justice classified report on money laundering stating that Icelandic banks were mentioned as open to such flows. Given the credibility of the source I have no doubt that the report exists (though all my efforts to trace it have failed). I have however no idea if that report was thoroughly researched or not nor in what context the Icelandic banks were mentioned.

Kaupthing and Usmanov

Some Icelandic banks did have clients from Russia and the former Soviet Union. The only one mentioned in the SICR, is the Uzbek Alisher Usmanov. He turned to Kaupthing in summer of 2008 when he was seeking to buy shares in Mmc Norilsk Adr. According to the SICR the bank also sold Usmanov shares in Kaupthing – by the end of September 2008 he owned 1.48% in the bank.

I am told that Usmanov was not Kaupthing client until in the summer of 2008 (earlier Icelog). Funding was generally drying up but Kaupthing was keen on the connection as it was planning to branch out to Russia and consequently looking for Russian connections.

If Usmanov’s shareholding in Kaupthing comes as surprise it is important to keep in mind that part of Kaupthing’s business model was to lend money to clients to buy Kaupthing shares. This was no last minute panic plan but something Kaupthing had been doing for years.

This model, which looks like a share-parking scheme, is a likelier explanation for Usmanov’s stake in Kaupthing rather than a sign of Usmanov’s interest in Kaupthing. A Kauphting credit committee minute from late September 2008, leaked after the collapse, shows that Kaupthing had agreed to lend Usmanov respectively €1,1bn and $1.2bn. According to Icelog sources the bank failed before the loans were issued.

Fridman, Exista and Baugur/Gaumur

There are two Icelandic links to Mikhail Fridman, through Kaupthing and the investment bank Straumur. Its chairman, largest investor and eventually largest borrower was Björgólfur Thor Björgólfsson.

By 1998, Kaupthing was operating in Luxembourg. In June that year, a Luxembourg lawyer, Francis Kass, appeared twice on the same day as a representative of two BVI companies, Quenon Investments Ltd and Shapburg Ltd, both registered at the same post box address in Tortola. His mission was to set up two companies, both with names linked to the North: Compagnie Financiere Scandinave Holding S.A. and Compagnie Financiere Pour L’Atlantique du Nord Holding S.A. The directors were offshore service companies, owned by Kaupthing or used in other Kaupthing offshore schemes.

These two French-named companies, founded on the same day by the same lawyer, came to play major roles in the Icelandic boom until the bust in October 2008. The former was for some years controlled by Kaupthing top managers until it changed name in 2004 to Meiður and to Exista the following year. By then it was the holding company for Lýður and Ágúst Guðmundsson who became Kaupthing’s largest shareholders, owning 25%. In 2000, the latter company’s name changed to Gaumur. Gaumur was part of the Baugur sphere, controlled by Jón Ásgeir Jóhannesson.

The owners of Exista and Baugur were dominating forces in the years when Icelandic banks and businesses were on their Ikarus flight.

Apart from the UK, the Icelandic business expansion abroad was most noticeable in Denmark. Danish journalists watched with perplexed scepticism as swaggering Icelanders bought some of their largest and most eye-catching businesses. In Iceland, politicians and business leaders talked of Danish envy and hostility, claiming the old overlords of Iceland were unable to tolerate the Icelandic success. They were much happier with the UK press that followed the Icelandic rise rather breathlessly.

In 2006 the Danish tabloid Ekstra bladet wrote a series of articles again bringing up Russian ties. Part of the coverage related to the two Krass companies: Quenon and Shapburg have also set up Alfa companies, part of Mikhail Fridman’s galaxy of on- and offshore companies.

The Danish articles were translated into English and posted on the internet. Kaupthing sued the Danish tabloid, which was forced to retract the articles in order to avoid the crippling costs of a libel case in an English court.

JP Galmond – the fixer who lost his firm

An adversary of Fridman, with Icelandic ties, figures in a long saga where also Usmanov plays a role: the Danish lawyer, Jeffrey Peter Galmond. – Some of the foreign fixers who have worked for ex-Soviet oligarchs have in some cases lost their lives under mysterious circumstance. JP Galmond lost his law firm. His story has been told in the international media over many years (my short overview of the Galmond saga).

Galmond was one of the foreign pioneers in St Petersburg in the early 1990s where he soon met Leonid Reiman, manager at the city’s telephone company. By the end of 1990s many foreign businessmen had learnt there was not a problem Galmond could not fix. Reiman went on to become a state secretary in 1999 when Boris Jeltsin made his Saint Petersburg friend Vladimir Putin prime minister.

By 2000 the Danish lawyer had turned to investment via IPOC, his Bermuda-registered investment fund. The following year he bought a stake in the Russian mobile company Megafon. Soon after the purchase Mikhail Fridman claimed the shares were his. This turned into a titanic legal battle fought for years in courts in the Netherlands, Sweden, Britain, Switzerland, the British Virgin Islands and Bermuda.

In 2004 Galmond’s IPOC had to issue a guarantee of $40m to a Swiss court in one of the innumerable Megafon court cases. The court could not accept the money without checking its origin. An independent accountant working for the court concluded that the intricate web of IPOC companies sheltered a money-laundering scheme. In spring of 2008 IPOC was part of a criminal case in the BVI. That same spring, the Megafon battle ended when Alisher Usmanov bought IPOC’s Megafon shares.

The Megafon battle exposed Galmond as a straw-man for Leonid Reiman who was forced to resign as a minister in 2009 due to the IPOC cases. In 2007, Galmond was forced to leave his law firm due to the Megafon battle; his younger partner Claus Abildstrøm took over and set up his own firm, Danders & More, in 2008.

Galmond’s Icelandic ties

In spite of the international media focus on Galmond, he and his partner Claus Abildstrøm enjoyed popularity among Icelandic businessmen setting up business in Copenhagen. An Icelandic businessman operating in Denmark told me he did not care about Galmond’s reputation; what mattered was that both Galmond and Abildstrøm understood the Icelandic mentality and the need to move quickly.

Already in 2002, Abildstrøm had an Icelandic client, Birgir Bieltvedt, a friend and business partner of both Björgólfur Thor Björgólfsson and Jón Ásgeir Jóhannesson. In 2004 Abildstrøm assisted Bieltvedt, Jón Ásgeir Jóhannesson and Straumur investment bank, where Björgólfsson was the largest shareholder, to buy the department store Magasin du Nord, where Abildstrøm then became a board member.

In 2007, when the IPOC court cases were driving Galmond to withdraw from his legal firm, the Danish newspaper Børsen reported that among Galmond’s clients were some of the wealthiest Icelanders operating in Denmark, such as Björgólfur Thor Björgólfsson and Jón Ásgeir Jóhannesson.

In his book, Ingimar Ingimarsson claimed that Galmond acted as an advisor to Björgólfsson. According to an Icelog source Galmond represented a consortium led by Björgólfsson’s father Björgólfur Guðmundsson when they bought a printing press in Saint Petersburg in 2004. Björgólfsson has denied any ties to Galmond and to Reiman but has confirmed that Abildstrøm has earlier worked for him.

Alfa, Pamplona Capital Management and Straumur/Björgólfsson

Pamplona Capital Management is a London-based investment fund, which in late 2007 entered a joint venture, according to the SICR, with Straumur, an investment bank where Björgólfur Thor Björgólfsson was the largest shareholder, chairman of the board and Björgólfsson-related companies were eventually the largest borrower (SICR).

In 2005 Pamplona had bought a logistics company, ADR-HAANPAA, operating in the Nordic countries, the Baltics, Poland and Russia. In 2007 Straumur provided a loan of €100m to refinance ADR in a structure where Pamplona owned 80.8%, Straumur 7.7% and ADR managers the rest.

Pamplona was set up in 2004 by the Russian Alexander Knaster, who as a teenager had immigrated to the US with his parents. Knaster was the CEO of Fridman’s Alfa Bank from 1998 until 2004 when he founded Pamplona, partly with capital from Fridman. Knaster has been a British citizen since 2009 and has, as several other Russian billionaires living in the UK, donated money, £400.000, to the Conservatives.

Incidentally, Pamplona shares the same London address as Novator, Björgólfsson’s investment fund, according to Companies House data: 25 Park Lane is one of London’s most attractive business addresses.

The Icelandic business model: corrupt patterns v “time is money”

Big banks such as Wachovia and Citigroup have been fined for facilitating money laundering for Mexican gangs. Deutsche Bank as been fined recently for doing the same for Russians with ties to president Trump. All of this involves violating anti-money laundering rules and regulations and this criminal activity has almost invariably only been discovered through whistle-blowers. Since large international banks could get away with laundering money, could something similar have been going on in the Icelandic banks?

The Icelandic Financial Supervisor, FME, was famously lax during the years of the banks’ stratospheric growth and expansion abroad. One anecdotal evidence does not inspire confidence: during the boom years an Icelandic accountant drew the attention of the police to what he thought might be a case of money laundering in a small company operating in Iceland and offshore. The police seemed to have a very limited understanding of money laundering other than crumpled notes literally laundered.

However, the banking collapse set many things in motion. The failed banks’ administrators, foreign consultants and later experts at the Office of the Special Prosecutor have scrutinised the accounts of the failed banks landing some bankers and large shareholders in prison. I have never heard anyone with plausible insight and authority mention money laundering and/or hidden Russian connections.

I do not know if it was systematically investigated but some of those familiar with the failed banks would know that money laundering, though of course hidden, leaves a certain patterns of transactions etc. But most importantly, the banks’ operation in Luxembourg, where in the Kaupthing criminal cases the dirty deals were done, have not been scrutinised at all by Luxembourg authorities.

The Icelandic businessmen most active in Iceland and abroad were famous for two things: complex structures, not an Icelandic invention – and buying assets at 10-20% higher prices than others were willing to offer.

As one Danish journalist asked me in 2004: “Why are Icelanders always willing to pay more than the asking price?” The Icelandic businessmen explained this by “time is money” – instead of wasting time to negotiate pennies or cents it paid off to close the deals quickly, they claimed.

Paying more than the asking price, exorbitant consultancy fees, sales at inexplicable prices to related parties and complicated on- and offshore structures are all known characteristics of systematic looting, control fraud and money laundering – and there are many examples of all of this from the Icelandic boom years. But these features can also be the sign of abysmally bad management.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Landsbanki Luxembourg: the investigated and non-investigated issues

The long-winding saga of the Landsbanki Luxembourg equity release loans is now in a French court in Paris, i.e. the alleged mis-selling. However, as the oral hearings brought out so clearly, other angles of this case have been ignored, i.e. the bank’s potential mismanagement of clients’ funds and the very questionable handling of the Landsbanki Luxembourg administrator. These last two issues have left so many clients frustrated and at their wit’s end.

A court case at the Palais de Justice, part of the spectacular Palais de la Cité on the Îsle de la Cité in the heart of Paris, is a grand spectacle to behold. Or at least that was my impression last week as I sat through two afternoons of oral hearing in the penal case against Landsbanki Luxembourg bankers and Landsbanki’s chairman Björgólfur Guðmundsson, the only one of the accused who was not present.

Apart from the three judges and the prosecutor there were the thirty or so lawyers fluttering around in their black cloaks with white bands around the neck. The lawyers were defence lawyers for those charged, lawyers for some of the witnesses and then there were lawyers related to civil cases connected to this case.

The case, brought by a prosecutor after an investigation led by Justice Renaud van Ruymbeke, centres on alleged mis-selling of equity release loans, as explained in an earlier Icelog. Oral hearings are scheduled until May 24, but the hearings were taking longer than expected and extra days to be added. The judgement can be expected in autumn.

French borrowers got contract in English, foreigners in French

The involvement of the very famous French singer Enrico Macias in the Landsbanki Luxembourg case has secured the attention of the French media; Macias took out an equity release loan of around €35m and his losses amount to €9m.* On the first day of the oral hearings, 2 May, Macias sat in court surrounded by his black-cloaked lawyers. On the second day of the hearings when Macias was questioned I counted nine lawyers apparently part of his entourage.

Macias was questioned back and forth for ca. three hours, no mercy there for this elderly gentleman, by the very astute and sharp judge. Only at one point, when one of the defence lawyers had probed Macias’ story did the singer lose his patience, crying out he had lost his wife and his house because of this bank. The judge reminded him that the charges were serious and the nine men accused had the right to defend themselves.

When Macias’ contract was brought up during the questioning an interpreter was called to assist. It turned out that Macias’ contract was in English. Some of the foreign borrowers were in court – German, English, American etc. It turns out that the foreign equity release borrowers all seem to have a contract in French. One told me he had asked for a contract in English and been told he would get it later; he didn’t.

Intriguingly, there seems to be a pattern here as I heard when I spoke to other borrowers: Landsbanki Luxembourg gave the foreign borrowers, i.e. non-French, a contract in French but the French borrowers, like Macias, got a contract in English.

“Produit autofinancé”

Much of the questioning centred on the fact that Landsbanki Luxembourg promised the borrowers the loans were “auto-financed.” To take an example: if the loan in total was for example €1m, the borrower got 20-30% paid out in cash and the bank invested the rest, stating the investment would pay for the loan. Ergo, Landsbanki promised the borrowers they would get a certain amount of cash for free, so to speak.

The judge asked the various witnesses time and again if that had not sounded to too good to be true to get a loan for free. As Macias and others pointed out the explanations given by the bankers and the brokers selling the loans seemed convincing. After all, these borrowers were not professionals in finance.

This line of questioning rests on the charges of alleged mis-selling. Other questions related to information given, who was present when the contracts were signed, validity of signatures etc.

The dirty deals in Luxembourg

The operations of the Icelandic banks have been carefully scrutinised in Iceland, first in the SIC report, published in April 2010 and later in the various criminal cases where Icelandic bankers and some of their closest collaborators have been prosecuted in Iceland.

There is one common denominator in all the worst cases of criminal conduct and/questionable dealings: they were conducted in and through Luxembourg.

All of this and all of these cases are well known to authorities in Luxembourg: Luxembourg authorities have assisted the investigations of the Icelandic Special Prosecutor, i.e. enabled the Prosecutor to gather information and documents in house searches in Luxembourg.

These cases exposing the role of Luxembourg in criminal conduct are all Icelandic but the conduct is not uniquely Icelandic. I would imagine that many financial crooks of this world have equally made use of Luxembourg enablers, i.e. bankers, lawyers and accountants, in financial shenanigans and crimes.

The Landsbanki questions Luxembourg has ignored

As I have pointed out earlier, alleged mis-selling is not the only impertinent question regarding the Landsbanki Luxembourg operations. There are also unanswered questions related to management of clients’ fund by Landsbanki Luxembourg, i.e. the investment part of the equity release loans (and possibly other investments) and, how after the bank’s collapse in October 2008, the bank’s court appointed Luxembourg administrator Yvette Hamilius has fulfilled her role.

As to the management of funds, some borrowers have told me that after the collapse of Landsbanki Luxembourg they discovered that contrary to what they were told the bank had invested their funds in Landsbanki bonds and bonds of other Icelandic banks. This was even done when the clients had explicitly asked for non-risky investments. As far as is known, Luxembourg authorities have neither investigated this nor any of the Icelandic operations with one exception: one case regarding Kaupthing is being investigated in Luxembourg and might lead to charges.

The latter question refers to serious complaints by equity release borrowers as to how Hamilius has carried out her job. Figures and financial statements sent to the clients do not add up. Hamilius has given them mixed information as to what they owe the bank and kept them in the dark regarding the investment part of their loans. Icelog has seen various examples of this. Hamilius has allegedly refused to acknowledge them as creditors to the bank.

On the whole, her communication with the clients has been exceedingly poor, letters and calls ignored and she has been unwilling to meet with clients. One client, who did manage to get a meeting with her, was seriously told off for bringing his lawyer along even though he had earlier informed her the name of the person he would bring with him.

Hamilius, on the other hand, claims the clients are only trying to avoid paying their debt. She has tried to recover properties in Spain and France, even after the bankers were charged in France. One of many remarkable turns in this case (see here) was a press release issued Robert Biever Procureur Général d’Etat – nothing less than the Luxembourg State Prosecutor – in support of Hamilius in her warfare against the equity release clients.

The court case at the imposing Palais de Justice in Paris gives an interesting insight into the operations of Landsbanki Luxembourg. As to management of funds prior to the bank’s collapse and the administrator’s handling of her duties Luxembourg has, so far, only shown complete apathy.

*I picked these numbers during the hearings but French media has reported different figures so I can’t certify these are the correct figures.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Macron and the power of ideas

During the Cold War there was no lack of Western intellectuals prophesying the end of the Western world as the efficient Soviet bloc would unavoidably win over democracy. Now the pre-destined outcome is seen to be populism that will engulf Western democracy. Making democracy work certainly is no mean task but one way of understanding the victory of Emmanuel Macron in France is reason beating irrational fears. Or as Macron himself has said: you convince people “by speaking to their intelligence.”

What do you do if you want to become a political leader? Listen to angry voters airing ideas politicians for decades haven’t had the wisdom or courage to challenge, such as foreigners and Europe being the reason for all problems – or do you formulate ideas you feel are important and debate them?

The latter is what Emmanuel Macron did in France: instead of lapping up anti-Europe sentiments and xenophobia advocated by Marine le Pen and her National Front, echoed in Brexit and, on a wider scale, the Trump victory in the US, Macron took two ideas seemingly on the vain, free trade and Europe, and won.