Archive for the ‘Uncategorised’ Category

Capital controls abolished – offer to offshore króna holders

As Már Guðmundsson governor of the Icelandic Central Bank, CBI underlined at a press conference today ordinary Icelanders have not felt the capital controls for a long time. Today, the controls are lifted for not only individuals but also for companies and the pension funds. Earlier limits have been lifted – de facto the capital controls are coming to an end in Iceland, more than eight years after they were put in place end of November 2008.

What remains in place is the following, according to the CBI press release:

i) derivatives trading for purposes other than hedging; ii) foreign exchange transactions carried out between residents and non-residents without the intermediation of a financial undertaking; and iii) in certain instances, foreign-denominated lending by residents to non-residents. It is necessary to continue to restrict such transactions in order to prevent carry trade on the basis of investments not subject to special reserve requirements pursuant to Temporary Provision III of the Foreign Exchange Act and the Rules on Special Reserve Requirements on New Foreign Currency Inflows, no. 490/2016. Guidelines explaining the above-mentioned restrictions will be issued to accompany the Rules.

The measures announced today were mostly as could be expected. However, the unknown variable was what offshore króna holders would be offered. Last summer they were offered a rate of ISK190 a euro; the onshore rate was ca. ISK140 at the time. The four large funds holding most of the remaining offshore króna – Loomis Sayles, Autonomy, Eaton Vance and Discovery Capital Management – refused that offer and have since been locked into low interest rates with an uncertain date of exit.

Now the offer is quite a bit more attractive: ISK137.50 a euro; the onshore rate is today ISK115.41. Last year, the offshore króna holders were offering ISK160 a euro, quite a bit better had the government been willing to accept it last year.

The CBI has lowered its bar, presumably because getting rid of the offshore króna holdings is seen as a bonus for Iceland. The sums captured inside the capital controls now amount to ISK195bn, less than 10% of GDP. Settling this last important part of trapped offshore króna means that Iceland can now take a step out of the shadow of the 2008 banking collapse – a chapter is coming to an end.

Former prime minister and former leader of the Progressive party Sigmundur Davíð Gunnlaugsson, forced to resign because of his offshore holdings exposed in the Panama papers, wrote today on Facebook that now the vulture funds were being rewarded; the funds had known they could crush the Icelandic government and that’s what they have now done. Others will beg to differ.

According to governor Guðmundsson the amount of offshore króna exiting at the new offer is just under ISK90bn. As far as I’m aware three of the four large funds have agreed to the present offer, which remains in place for the coming two weeks. One fund is considering its options, which must include testing the legality of earlier measures, a route the funds had already embarked on.

In total the four funds hold ISK120bn, further ISK12bn are holdings in shares, which are not being sold (thus nothing volatile there) and ISK60bn are deposits owned by various investors (some of whom might well have forgotten about their holdings or who are for some reason unaware of being the lucky owners of some Icelandic króna).

This means that although ISK90bn is less than half of the remaining offshore króna it’s roughly 3/4 of the offshore króna that could potentially move (though the funds do indeed want to keep their Icelandic relatively high-interest króna assets but that’s another saga).

What now remains in place is hindrance on inflows – as I’ve said earlier some would call it another form of capital controls but I side with the CBI that already in 2012 announced the conditions after capital controls would not be like before November 2008. Iceland isn’t interested in being the destination of money flows looking for lucrative interest rates. Consequently, prudent measures are in place since last summer.

Benedikt Jóhannesson minister of finance called today “a day of gladness.” Given that the controls had already been eased it’s unlikely the Icelandic króna will move much tomorrow or the coming days. The pension funds have good reasons to be vary of moving abroad. Though foreign investments would be wise as means of hedging foreign markets of low interest rates and high asset prices are not inviting.

Iceland is booming – the economy grew by 7.2%(!) of GDP last year. No exaggeration that there are good times in Iceland but good times aren’t necessarily easy times in a small economy with its own currency. With capital controls out of the way Iceland there is one thing less to worry about, the rating agencies will see this as a favourable move that might soon be expressed in more favourable ratings, eventually meaning lower interest rates in Iceland – so as to end on an optimistic note.

PS Why was the government keen to act now re offshore króna holders? Well, first for the entirely obvious reasons that Iceland is doing very well with large foreign currency reserves (not entirely trivial to invest them sensibly) and consequently it’s difficult to claim that economic hardship bars solution. In addition, as the minister of finance mentioned today: the rating agencies have indicated that the rating might move up, with the benefits such as lower interest rates when the sovereign borrows, spilling over into lower interest rates in Iceland. Last, it seems that the International Monetary Fund, very patient so far, was starting to air its worries: Iceland couldn’t keep boxing in the offshore króna holders indefinitely.

From top prime minister Bjarni Benediktsson, minister of finance Benedikt Johannesson (the two ministers are closely related, both from one of the most prominent business families in Iceland) and Már Guðmundsson governor of the CBI. Screenshots from the press conference today – notice the painting behind the two ministers: by Jóhannes Kjarval (1882-1972) the most iconic Icelandic artist, whose favourite motive was Icelandic landscape, most notable the lava landscape like here.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Will the last bit of capital controls soon be removed?

Now that ordinary Icelanders can invest ISK100m abroad a year and buy one property abroad, life is returning back to normal after capital controls or at least for the 0.01% of Icelanders that will be able to make use of this new normal. This new CBI regime was put in place on the last day of 2016.

For all others, capital controls have for a long time not been anything people sensed in everyday life. The controls really were on capital, in the sense that Icelanders could not invest abroad, but they could buy goods and services, i.e. ordered stuff online and, mostly relevant for companies, paid for foreign services.

The almost only tangible remains of the capital controls regard the four large funds – Eaton Vance, Autonomy, Loomis Sayles and Discovery Capital Management – still locked inside the controls with their offshore króna (by definition króna owned by foreigners, i.e. króna owned by foreigners who potentially want to exchange it to foreign currency).

I’ve written extensively on this issue earlier, recently with a focus on the utterly misplaced ads regarding the policy of the Icelandic government (the policy can certainly be disputed but absolutely not in the way the ads chose to portray it; see here and here; more generally here). From over 40% of GDP end of November 2008, when the controls were put in place, the offshore króna amounted to ca. 10% of GDP towards the end of 2016 (see the CBI: Economy of Iceland 2016, p. 75-81.) The latest CBI data is from 13 January this year, showing the amount of offshore króna at ISK191bn, below 10% of GDP.

It now seems there have been high-level talks and as far as I can understand there is great willingness on both sides to find an agreement, which would most likely involve an exit rate somewhat less favourable than the present rate (meaning there would be some haircut for the funds, i.e. some loss) and also that they would exit over some period of time (they have earlier indicated that they are in no hurry to leave).

As before, the greatest risk here is political: will the opposition or parts of it, try to use this case to portray the government as dancing to the tune of greedy foreigners? Icelanders have had a share of the populism so prevalent in other parts of the world but Icelandic politics is by no means engulfed by it.

Arguments in this direction can’t be ruled out but the argument for solving the issue is that Iceland should be moving out of the long shadows of the 2008 collapse, the Central Bank has been buying up foreign currency in order to fetter the ever-stronger króna and this is a problem easier to solve now with the economy booming rather than at some point later in a more uncertain future.

Obs.: on 4 June 2016 the CBI announced a new instrument to “temper and affect the composition of capital inflows.” Some people call this a new form of capital controls. I don’t agree and see these measures, as does the CBI, as a set of prudence rules, announced as a possible course of action already in 2012. Over the last decades other countries have taken a similar course to prevent the inflow of capital that could in theory leave quickly.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

A government born out of discontent and weak majority

It took Bjarni Benediktsson leader of the Independence Party 73 days and three attempts to form a government with two small centre-right parties, Bright Future (Björt Framtíð) and the Reform Party (Viðreisn). The majority is the tiniest possible: one seat. And so is the enthusiasm for the new government, really tiny. New opinion poll shows that 25% is content with the government. The left opposition lost an opportunity to form a government, the voters of the two small coalition parties feel they were cheated into securing an Independence Party rule and the latter party is sour because the government seems weak and Southern Iceland that brought the party most votes got no minister(s). – Thus starts the life of a new government, with irritation and anger. Things can only get better or there will be early elections, again.

In the history of Icelandic politics since the founding of the republic in 1944 political instability hasn’t been dominant. Icelanders got through the 2008 banking collapse but shed the collapse government after a winter of protests, which felt more playful than threatening, hence the cute name of the ‘Pots and pans’ revolution. When the left government, voted to power in the spring of 2009, survived a whole parliament term of four years in spite of fierce infighting it seemed that Iceland was back to stability.

Even more so since the new centre right coalition led by the Progressive Party, with the Independence Party had a safe majority, 38 out of 63 seats. The Panama papers shattered that strength April 3 2016. The day after prime minister Sigmundur Davíð Gunnlaugsson stumbled through the now world famous interview and tried to lie his way out of the revealing questions Bjarni Benediktsson signalled the end of Gunnlaugsson’s government by refusing to back Gunnlaugsson. Two days after the interview Gunnlaugsson resigned, ending the politically weirdest 48 hours Icelanders had ever witnessed.

After a political limbo from spring 2016 to autumn came the October 29 election and 73 days later a new government. None of this signals strength. The new government starts its life with bets against it enduring a full term.

EU: both a raison d’etre and a non-issue

The main reason for former Independence Party voters or right-leaning social democrats to vote for Reform (it seems mainly to have taken voters from the latter, many pro-EU voters had already left the IP in the last two elections) was to secure an action regarding an Icelandic EU membership. Reform was founded by angry IP voters who felt the grand old party had been less than grand in going back on its promise of a referendum.

But this raison d’etre for Reform has now turned into a non-issue, both because many Icelanders want to see how Brexit fares and also because EU is not a pressing issue for booming Iceland.

The Reform party: born out of pro-EU sentiments

The broken promise, which spurned some political enthusiasts into action, was a promise that IP leader Bjarni Benediktsson gave before the 2013 elections. In 2009, the social democrats, buoyed by their election victory and the prime minister post, fulfilled their long-standing promise of applying for EU membership. The Left Greens, their coalition partner, was against membership but the social democrats didn’t take no for an answer.

Up to the 2013 elections IP’s Benediktsson, whose party is split on EU, said holding a referendum asking voters if they wanted to continue membership negotiations was the best way to test voters’ EU sentiments. When in government with the Progressives, who had in principle supported such a vote though the party is fiercely anti-EU, Benediktsson suddenly saw nothing but a ‘political impossibility’ in holding such a vote as both coalition parties were against EU membership.

This caused huge outrage and protests for weeks – there has never been a clear majority in opinion polls to join the EU but this time, there was a huge majority for finalising a membership agreement and then vote on it. This anger spurred pro-EU former Independent party-member Benedikt Jóhannesson to form Reform. The Icelandic name, ‘Viðreisn,’ means ‘Revival’ rather than ‘Reform.’ In Icelandic politics the word refers to a period in Icelandic history, end of the 1950s and 1960s, when IP was in government with the social democrats, seen as a time of prosperity and growth in Iceland.

Now: Icelandic EU membership – let’s forget it

After being so wedded to an EU membership many feel that Jóhannesson and BF’s leader Óttarr Proppé have turned very meek in front of the IP’s EU antipathy. All there is left of a promise of a referendum is this: ‘The government parties agree that if the subject of a referendum on accession negotiations with the European Union is raised in the Althingi, the issue will be put to a vote and finalised towards the end of the electoral period. The government parties may have different opinions on this matter and will respect each other’s views.’

This indicates that well, maybe the matter won’t be raised and then there will be no referendum. However, Reform’s MP Jón Steindór Valdimarsson, a prominent advocate for Icelandic EU membership, has stated that people can rest assured: EU membership will be brought up in the Alþingi. And also, that the parties have agreed to disagree when a referendum will be brought to a vote.

EU membership is not a hot topic in Iceland but the anger still simmers against the last government’s blatant change-of-plan. This means that this very feeble promise on the issue is seen as an abject failure by the two small parties to stick to their EU focus; effectively that the IP bulldozed over them.

‘System change’

One of the most prominent words before the election last October was ‘system change’ – in short, the new parties – i.e. Reform, Bright Future and the Pirates – advocated ‘system change’ whereas the ‘four-party’ as the old parties are called in Icelandic – IP, the Progressives, the social democrats and Left Green – sounded less enthusiastic.

The word mostly referred to fundamental changes in how to allot fishery quotas and farming subsidies, i.e. policies concerning the two old sectors in the Icelandic economy. Two sectors still shaped by the political climate of earlier decades though their part of the economy has dwindled – now, tourism is both the largest sector and the growth sector.

Reform advocated what it called ‘the market approach’ to both these old sectors. Fishing quotas should to a certain degree be auctioned off in order to increase the national profit of fisheries, i.e. levies and taxes, akin how the Faroese have done.

This ambition has been whittled down in the new government’s ‘Platform:’ “The government considers that the benefits of the catch quota system are important for continuing creation of value in the fishing industry. Attention will be given to the benefits of basing the system on long-term agreements rather than allocations without time limits; at the same time, other possible choices will be examined, such as market-linking, a special profit-based fee or other methods to better ensure that payment for access to this common resource will be proportional to the gains derived from it. The long-term security of operations in the sector and economic stability in the rural areas must be ensured.”

Those who advocate changed agricultural policy, away from subsidies to a more consumer-friendly, less protective agriculture, with more import of foreign agricultural produce find this statement very weak: “The allocation of import quotas must be revised and the premise for the dairy industry’s derogations from competition law must be analysed and suitable amendments made.”

The government may surely surprise Icelanders but so far, there is little to indicate that the new parties will be allowed to make a strong departure to the way the IP has run the basic industries for decades.

Feeble vision on tourism

The previous Progressive-led government lost three precious years where the fastest growing most cash-giving industry, tourism, blossomed but without any policy guidelines as to what sort of tourism Iceland wants to pursue. The previous government seemed to be beholden to the interests of certain companies: it couldn’t solve the problem of identifying the most pressing infrastructure projects nor was it able to decide on a levy-structure in tourism. Truly a phenomenal omission.

The new government is worryingly vague on its aims for tourism in Iceland, only two sentences on it in its ‘Platform:’ The importance of tourism as an occupational sector is to be reflected in the administration’s tasks and long-term policy-making. In the years to come, emphasis will be placed on projects that will be conducive to harmonised management of tourism, research and reliable gathering of data, increased profitability of the sector, the spread of tourists to all parts of the country, and rationalised levying of fees, e.g. in the form of parking fees.

Is parking fees the only grand idea of funding? Then that’s worryingly limited and unambitious.

At the same time Iceland is clearly becoming immensely dependent on tourism. With hotels sprouting everywhere there are whispers in the banking sector that further lending to tourism-related projects should be severely conservative.

The truly revolutionary turn: no more polluting heavy industries

Many Icelanders are worried that the aspect of clean and pure nature is hugely compromised by several recent heavy-polluting industries around Iceland in addition to the old ones. Hidden in the three-paragraphs on ‘Environment and Natural Resources’ there is this sentence: ‘There will be no new concessionary investment agreements for the building of polluting heavy industry.’

This may not seem much but in the Icelandic context this is truly revolutionary: a sharp turn from decades of striving to attract heavy polluting industries to Iceland, often with investment agreement granting some form of governmental favours. It can’t be emphasised too much what a turnaround this is – yes, truly revolutionary.

Clear right-leaning policy with a social slant

Although the government advocates responsible housekeeping and financial stability there is also some focus on social matters. Benedikt Jóhannesson has mentioned that Iceland is competing with its Nordic neighbours in holding on to young Icelanders, of getting them to return home from studying abroad or keeping them at home instead of moving abroad.

Jóhannesson has very correctly identified this problem: Icelanders do indeed compare their standard of living to their Nordic neighbours – and Iceland falls short in many aspects.

One policy advocated by the new government is to adapt Icelandic study loans to the system in the other Nordic countries: ‘A scholarship system based on the Nordic model will be adopted and lending from the Student Loan Fund will be based on full cost of living support and incentives for academic progress. Consideration will be given to the social role of the Fund. – This seems a more costly option then the present student loan system and the extra funds needed haven’t been specified as far as I know.

Immigrants are less skilled than Icelanders who emigrate

One potential danger is the above: the mismatch in outflow and inflow of people. The booming tourism needs a lot of low-skilled work, now largely provided by foreign workers whereas educated or highly skilled Icelanders have been tempted to emigrate or don’t return after studying abroad but choose to find work after finishing their studies.

In the 2015 OECD Economic Survey of Iceland this problem is spelled out: ‘The current boom is based to some extent on the rapid development of the tourism sector. With one million visitors in 2014, this is welcome, but it tends to create relatively low-skilled low-wage jobs and comes with limited opportunities for productivity growth. Against the draw of migrants to the booming low-skill jobs, the Icelandic economy is experiencing outmigration of high-skilled people. Furthermore, unemployment amongst university graduates is rising, suggesting mismatch. As such, and despite the economic recovery, Iceland remains in transition away from a largely resource-dependent development model, but a new growth model that also draws on the strong human capital stock in Iceland has yet to emerge.’

This wasn’t at all welcome news in Iceland and it was clear that some politicians are in denial about this mismatch. Icelanders, especially politicians, like to portray Iceland as a country with highly skilled workforce. At a closer look, comparing higher education in Iceland to the neighbouring countries, this isn’t really true. And the above paragraph proved an unpalatable course (as I sensed when reporting for Rúv I brought this up: there was some attempt from political quarters to rubbish the OECD data.)

Therefore it’s particularly refreshing to hear Jóhannesson mention this fact – that Iceland is indeed in many ways struggling to maintain skilled people and people with higher education. Whether something sensible comes out of it remains to be seen but acknowledging the problem is a promising first step.

Will the government last the full parliamentary term?

It’s too early to tell, so far so eventless. Or well, not quite. As a minister of finance Bjarni Benediktsson reacted to the Panama leak – which cost Sigmundur Davíð Gunnlaugsson both his prime minister post and leadership of his party, the Progressives and showed that also Benediktsson had offshore connections – by setting up a taskforce in mid June to estimate Icelandic assets offshore and the loss to the Treasury caused by the Icelandic offshorisation.

The taskforce handed in its report on September 13 and gave a presentation to Benediktsson on October 5. On October 10 Benediktsson said in Alþingi the report would be published in the next few days but nothing happened. It wasn’t until January 6 that the report was unceremoniously published on the ministry’s website and sent to the Alþingi economy and trade committee – after some journalists and politicians had said they would demand access by using the Icelandic Freedom of Information act.

When questioned Benediktsson brusquely denied there had been any cover-up, the report had simply come too late to be discussed in the outgoing parliament. A day later, Benediktsson was forced to retract his words and apologise: there had indeed be enough time to present it before the elections. Notably, elections called because of offshorisation. – Benediktson, now prime minister, has recently refused to discuss the report with the Alþingi economy and trade committee but says he will discuss its finding when the report will be debated in Alþingi.

This wasn’t a glorious end to Benediktsson’s time as minister of finance and the beginning of his reign as prime ministers. His opponents talk of his attempted cover-up, others that this is his typical lack of attention to details, a certain carelessness and sloppiness.

Governing in good times – not as easy as it seems

Politicians in power in times of crisis and hardship may at times dream of the sweetness of power in good times. In Icelandic we say that it takes strong bones to survive prosperity. That’s exactly the challenges facing Iceland for the time being.

The GDP growth last year was around 4%, unemployment is 4%, building cranes crowed the Reykjavík city scape, the Central Bank is facing losses because of the foreign currency it’s hording to keep the króna, now record strong, from being even stronger – all of this both signs of prosperity and challenges. Right now, fishermen have been striking since mid December, no end in sight. They are both demanding substantial wage increases, which the fishing industries refuse to meet and that the government reinstalls earlier tax deductions, flatly denied by minister of finance Jóhannesson.

In spite of good times in Iceland there is a permanent political chill over the island for the time being. It remains to be seen if the new government finds the way to melt the chill without ending up with an overheated and out-of-control economy – a far too familiar phenomenon in the prone-to-bumpy-ride Icelandic economy.

There are eleven ministers and eight ministries in the new Icelandic government – from the Independence Party (6): party leader and prime minister Bjarni Benediktsson, Kristján Þór Júlíusson minister of Education, Science and Culture, Þórdís Kolbrún Reykfjörð Gylfadóttir minister of Tourism, Industries and Innovation (Ministry of Industries and Innovation), Guðlaugur Þór Þórðarson minister of foreign affairs, Sigríður Ásthildur Andersen minister of Justice (Ministry of the Interior), Jón Gunnarsson minister of Transport and Local Government (Ministry of the Interior); Reform Party (3): party leader and minister of Finance Benedikt Jóhannsson, Þorsteinn Víglundsson minister of Social Affairs and Gender Equality (Ministry of Welfare), Þorgerður Katrín Gunnarsdóttir minister of Fisheries and Agriculture (Ministry of Industries and Innovation); Bright Future (2): party leader Óttarr Proppé minister of Health (Ministry of Welfare), Björt Ólafsdóttir minister for the Environment and Natural Resources. – Only ministries with two ministers are mentioned above. The government has announced that it plans to split the Ministry of the Interior into Ministry of Justice and Ministry of Transport and Local Government, which means there will soon be nine ministries. – I have earlier used the name “Revival” for Viðreisn without noticing that on its English website “The Reform Party” is the name used.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

How is this possible, Greece?

The Greek ELSTAT saga has taken yet another turn, which should be a cause for grave concern in any European country: a unanimous acquittal by three judges of the Greek Appeals Court in the case of former head of ELSTAT Andreas Georgiou has been annulled. This was announced Sunday December 18 – the case was up in court December 6 – but no documents have been published so far, another worrying aspect.

The acquittal was the fourth attempt to acquit Gergiou – and this is now the fourth attempt to thwart the course of Greek justice and revive the unfounded charges against him. The intriguing thing to note here is that the acquittal was annulled by a prosecutor at the First Instance Court, who in September brought a whole new case regarding the debt and deficit statistics from 2010 and ELSTAT staff role here, this time not only accusing ELSTAT staff of wrongdoing but also staff from Eurostat and the IMF; a case still versing in the Greek justice system.

All of this rotates around the fact that ELSTAT, and now Eurostat and IMF staff, is being prosecuted for producing correct statistics after more than a decade of fraudulent reporting by Greek authorities.

It beggars belief that the justice system in Greece seems to be wholly under the power of political forces who try as best they can to avoid owning up to earlier misdeeds. In spite of acquittals, those who corrected the fraudulent statistics are being prosecuted relentlessly while nothing is done to explain what went on during the time of the fraudulent reporting. It should also be noted that in order to stop the ELSTAT prosecutions completely, four other cases related to this one, need to be stopped.

The ELSTAT staff is here reliving the horrors of the Lernaen Hydra in Greek mythology. Georgiou and his colleagues have had international support but that doesn’t deter Greek authorities from something that certainly looks like a total abuse of justice. How is it possible to time and again take up a case where those charged have already been acquitted?

Icelog has followed the ELSTAT saga, see here for earlier blogs, explaining the facts of this sad saga.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Has Iceland learnt anything from the 2008 banking crash?

With its 2600 pages report into the banking collapse no nation has better study material to learn from than Iceland. However, with some recent sales in Landsbankinn and uncertainties regarding the sales of the new banks, Icelanders have good reasons to wonder what lessons have indeed been learnt from the 2008 banking collapse. If little or nothing has been learnt it’s worrying that two or three banks will soon be for sale in Iceland.

“During the election campaign I would have liked to hear the candidates form a clear and concise lessons from the 2008 banking collapse,” said one Icelandic voter to me recently. He’s right – there was little or no reference to the banking collapse during the election campaign in October.

The unwillingness to formulate lessons is worrying. So many who needed to learn lessons: bankers, lawyers, accountants, politicians and the media, in addition to every single Icelander.

Also, some recent events would not have happened had any lessons been learnt from this remarkable short time of fully privatised banking, from the beginning of 2003 to October 6 2008. There is a boom in Iceland, reminding many of the heady year 2007 but this time based inter alia tourism and not on casino banking. However, old lessons need to be remembered in order to navigate the good times.

Landsbankinn: six loss-making sales 2010-2016

Landsbankinn was taken over by the Icelandic state in 2011. The largest creditors, the deposit guarantee schemes in Britain and the Netherlands, were unwilling to be associated with the Landsbankinn estate, contrary to creditors in Kaupthing and Glitnir. Consequently, the Icelandic state came to own the new bank, Landsbankinn.

Over the years certain asset sales by Landsbankinn have attracted some attention but each and every time the bank has defended its action. In certain cases it has admitted mistakes but always with the refrain that now lessons have been learnt, time to move on.

Earlier this year, the Icelandic State Financial Investments (Bankasýsla), ISFI, published a report on one of these sales, the one causing the greatest concern – of Landsbanki’s share in a credit card issuer, Borgun. Landsbankinn had undervalued its Borgun share by billions of króna, creating a huge gain for the buyers.

Landsbankinn chose the buyers, nor bidding process etc., this was not a transparent sale. It so happens that some of the buyers happen to be closely related to Bjarni Benediktsson leader of the Independence party and minister of finance. No one is publicly accusing Benediktsson for having influenced the sale.

ISFI concluded that Landsbankinn should have known about the real value of the company and should only have sold via a transparent process, not by handpicking the buyers, some of whom are managers in Borgun. Part of the hidden value was Borgun’s share in Visa Europe, sold in November 2015 after the bank sold its Borgun share. Landsbankinn managers claim they were unaware of the potential windfall that could arise from such a sale.

Following the ISFI report the majority of the Landsbankinn board resigned but not the bank’s CEO, Steinþór Pálsson.

Landsbankinn’s close connections with the Icelandic Enterprise Investment Fund

Now in November the Icelandic National Audit Office, at the behest of the Parliament, investigated six sales by Landsbankinn, conducted in the years 2010 to 2016. It identified six sales, one of them being the Borgun sale, where it concluded that the state’s rules of ownership and asset sale had been broken as well as the bank’s own rules.

The report also points out that some of Landsbankinn’s own staff would have been aware of the potential windfall in Borgun. In a similar sale in another card issuer, Valitor, the sales agreement included a clause giving the bank share in similar gains after the sale.

Landsbankinn CEO Pálsson said he saw no reason to resign since lessons from these sales had already been learnt. However, nine days after the publication of this report Landsbankinn announced that Pálsson would step down with immediate effect.

Interestingly, four of the less-than-rigorous sales involved the Iceland Enterprise Investment Fund (Framtakssjóður), IEIF, set up in 2010 by several Icelandic pension funds. In the first questionable Landsbankinn sale, in 2011, the bank sold a portfolio of assets directly to the IEIF without seeking other buyers. The portfolio was later shown to have been sold at an unreasonably low price.

In relation to the sale Landsbankinn became the IEIF’s biggest owner. The Financial Surveillance Authority, FME, later stipulated that the bank could not hold a IEIF stake above 20%. In 2014 the bank then sold part of its share in the IEIF to the Fund itself, again at an unreasonably low price. In two sales, 2011 and 2014, Landsbankinn sold shares in Promens, producer of plastic containers for the fishing industry, again to the Fund.

As the Audit Office points out all the questionable sales have had two characteristics: a remarkably low price and Landsbankinn has not searched for the highest bidder but conducted a closed sale to a buyer chosen by the bank.

No one is accused of wrongdoing but it smacks of closed circuits of cosy relationships, a chronic disease in the Icelandic business community.

Landsbankinn and the blemished reputation

Landsbankinn claims it has in total sold around 6.000 assets via a transparent process. That may be true but the Audit Office report indicates that the bank chooses at times to be less than transparent, especially when it’s been dealing with the IEIF.

The bank’s management has time and again stated the importance of improving the bank’s reputation – after all, the 2008 collapse utterly bereft Icelandic banking of its reputation. This strife is the topic of statements and stipulations but so far, deeds have not followed words. The Audit Office concludes that inspite of its attempts the bank’s reputation has been blemished by the questionable sales.

How the banks were owned before the collapse

During the years of privatisation of the Icelandic banks, from 1998 to end of 2002, it quickly became clear that wealthy individuals were vying to be large shareholders in the banks. There was some talk of a spread ownership but in the end the thrust was towards having few individuals as main shareholders in the three banks.

Landsbankinn was bought by father and son, Björgólfur Guðmundsson and Björgólfur Thor Björgólfsson who during the 1990s got wealthy in the Soviet Union. A fact that gave rise to articles in the magazine Euromoney in 2002, before the Landsbankinn deal was concluded.

Kaupthing’s largest owners were, intriguingly, businessmen who got wealthy through deals largely funded by Kaupthing. The largest shareholder, Exista, was owned by two brothers, Ágúst og Lýður Guðmundsson and the second largest was Ólafur Ólafsson. The brothers own one of Britain’s largest producers of chilled ready-made food, Bakkavör. Ágúst got a suspended sentence in a collapsed-related criminal case. Ólafsson, together with Kaupthing managers, was sentenced to 4 ½ years in prison in the so-called al Thani case.

Glitnir had a less clear-cut owner profile to begin with. The family of Bjarni Benediktsson were large shareholders in the bank (then called Íslandsbanki, as the new bank is now called) but as the SIC report recounts the Landsbankinn father and son had built up a large stake in the bank. The FME kept pestering the father and son about these shares, the authority claimed the two were not authorised to own, later sold to the Benediktsson’s family and others.

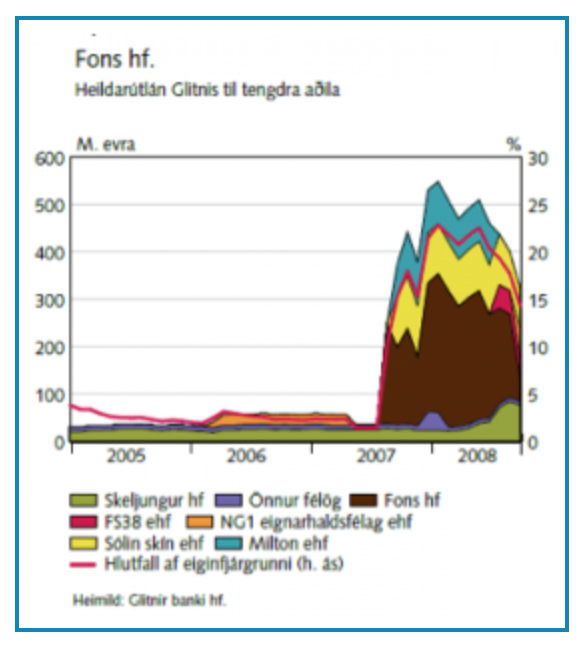

In spring of 2007 Jón Ásgeir Jóhannesson, who had insistently but unsuccessfully tried to buy a bank in 1998, gathered a group to buy around 40% in Glitnir. Involved were Baugur and FL Group, both owned or largely owned by Jóhannesson. One of his partners was Pálmi Haraldsson, a long-time co-investor with Jóhannesson. This graph (from the SIC report) shows Glitnir’s lending to Fons and other Haraldsson’s related companies: the cliff of debt rises after these businessmen bought Glitnir. It could also be called Icelandic banking in a nutshell:

Biggest shareholders = biggest borrowers

The graph above is Icelandic banking a nutshell. It characterises what the word “ownership” meant for the largest shareholders: they were also the banks’ largest borrowers, as well as borrowing in the other two banks. The shareholding of the largest groups in each of the banks was around and above 40% during most of the short run – the six years – of privatised banks.

Here some excerpts from the SIC report about the borrowing of the largest shareholders:

The largest owners of all the big banks had abnormally easy access to credit at the banks they owned, apparently in their capacity as owners. The examination conducted by the SIC of the largest exposures at Glitnir, Kaupthing Bank, Landsbankinn and Straumur-Burðarás revealed that in all of the banks, their principal owners were among the largest borrowers.

At Glitnir Bank hf. the largest borrowers were Baugur Group hf. and companies affiliated to Baugur. The accelerated pace of Glitnir’s growth in lending to this group just after mid-year 2007 is of particular interest. At that time, a new Board of Directors had been elected for Glitnir since parties affiliated with Baugur and FL Group had significantly increased their stake in the bank. When the bank collapsed, its outstanding loans to Baugur and affiliated companies amounted to over ISK 250 billion (a little less than EUR 2 billion). This amount was equal to 70% of the bank’s equity base.

The largest shareholder of Kaupthing Bank, Exista hf., was also the bank’s second largest debtor. The largest debtor was Robert Tchenguiz, a shareholder and board member of Exista. When the bank collapsed, Exista’s outstanding debt to Kaupthing Bank amounted to well over ISK 200 billion.

When Landsbankinn collapsed, Björgólfur Thor Björgólfsson and companies affiliated to him were the bank’s largest debtors. Björgólfur Guðmundsson was the bank’s third largest debtor. In total, their obligations to the bank amounted to well over ISK 200 billion. This amount was higher than Landsbankinn Group’s equity.

Mr. Thor Björgólfsson was also the largest shareholder of Straumur-Burðarás and chairman of the Board of Directors of that bank. Mr. Björgólfur Thor Björgólfsson and Mr. Björgólfur Guðmundsson were both, along with affiliated parties, among the largest debtors of the bank and together they constituted the bank’s largest group of borrowers.

The owners of the banks received substantial facilities through the banks’ subsidiaries that operated money market funds. An investigation into the investments of money market funds under the aegis of the management companies of the big banks revealed that the funds invested a great deal in securities connected to the owners of the banks. It is difficult to see how chance alone could have been the reason behind those investment decisions.

During a hearing, an owner of one of the banks (Björgólfur Guðmundsson), who also had been a board member of the bank, said he believed that the bank “had been very happy to have [him] as a borrower”. Generally speaking, bank employees are not in a good position to assess objectively whether the bank’s owner is a good borrower or not.

De facto, the Icelandic banks were “lenders of last resort” for their largest shareholders: when foreign banks called in their loans in 2007 and 2008 the Icelandic banks to a large extent bailed their largest shareholders out with massive loans.

Needless to say, systemically important banks in most European countries are owned by funds and investors, not few large shareholders who are also the banks’ most ardent borrowers. Icelandic banks will hopefully never return to this kind of lending again.

Separating investment banking and retail banking

As very clearly laid out in the SIC report the banks did not only turn their largest shareholders into their largest debtors but the banks’ own investments were usually heavily tied to the interests of their largest shareholders. Therefor, it’s staggering that now eight years after the collapse and three governments later a Bill separating investment banking and retail banking has not yet been passed in the Icelandic Parliament.

This means that most likely the new banks – Landsbankinn, Arion and Íslandsbanki – will be sold without any such limitation on their banking operations.

It is indeed difficult to see that there could be a market in Iceland for three banks. There is speculation that there will be foreign buyers but sadly, the history of foreign investment in Iceland is not a glorious one. Iceland is not an easy country to operate in as heavily biased as it is towards cosy relationships so as not to say cronyism.

Another way to attract foreign buyers is to offer shares for sale at foreign stock exchanges; Norway has been mentioned. Clearly a good option but I’ll believe it when I see it.

Judging from the short span of privatised banks in Iceland it’s also a worrying thought that the banks will again be owned by large shareholders, holding 30-50%.

The fact that state-owned Landsbankinn could over six years conduct six questionable sales with no consequence until much later, raises questions about lessons learnt. And the fact that this potentially simple risk-limiting exercise of splitting up investment and retail banking hasn’t yet been carried out by the Icelandic Parliament makes one again wonder about the lessons learnt. And yet, Iceland has the most thorough report in recent times in the world to learn from.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

The ELSTAT saga: the latest

Former head of ELSTAT, the Greek statistical authority, Andreas Georgiou has been acquitted in the case where he was charged with misdemeanour. Three foreign statisticians came to Athens to bear witness in the case, testifying to Georgiou’s positive work on rectifying the problems of earlier false statistics.

The irony is that the Greek government is silently accepting that civil servants who fixed the problem of a decade or fraudulent statistics are being prosecuted, not those who committed the fraud for years.

But as lister earlier on Icelog this is only one of four cases Georgiou is fighting in Greece. The other cases against Georgiou are still lingering in Greek courts. In the largest case against himm where he is charged with treason for in fact correctly reporting correct statistics, the examining judge has now proposed that the case be dismissed. Stunningly, this is the fourth time a judge proposes to have the case dropped but so far it’s always risen again in a new guise.

Here is Kathimerini report on the latest trial and its outcome.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Offshore króna owners allowed to seek independent estimates – inflows have stopped

An application with the Reykjavík District Court for independent assessment of the Icelandic economy, launched by two of the funds holding the majority of the Icelandic offshore króna, has been met by the Court. Originally, the funds had eleven requests; the Court granted three of them according the Icelandic daily DV.

The two funds claim the measures taken against the offshore króna holders this summer – effectively forcing them out at a great discount or freezing the funds at below-inflation interest rates – are harmful measures, utterly unnecessary in the booming Icelandic economy. They now want an independent assessment of the economy, in order to show that the Icelandic government could well afford more generous terms.

According to a recent decision by the EFTA Surveillance Authority the offhore króna measures were within the remit of the Icelandic government and did not break any EEA rules.

The measures no doubt had a sobering effect on foreign visitors but it the use of a new tool to temper inflows, announced in June this year that has had an effect: according to new figures released by the Central Bank, inflows into Icelandic sovereign bonds have completely stopped since June when the measures were put in place.

There had been some concern that the large inflows might jeopardise Icelandic financial stability as indeed it did in 2008 when capital controls were put in place exactly because of these inflows. Governor of Central Bank Már Guðmundsson said earlier this year that the renewed inflows, which the Bank would monitor, were a sign of trust in the Icelandic economy. Well, no worries – the measures in June stopped the inflows.

For earlier Icelog on the offshore króna issues please search the website.

Update: this piece has been updated as the earlier report re the effect on inflows was incorrect.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

The ELSTAT saga: ongoing vendetta against civil servants who saved Greek statistics

There is no end in sight of the ELSTAT saga of political vendetta against the ex ELSTAT director Andreas Georgiou who oversaw the correction of Greek statistics 2010 to 2015. Yes, the Prosecutor of the Appeals Court has recommended to throw the case of Georgiou and his colleagues out, not once but three times, only to resurface again. In addition, the case has transformed into several case all migrating through the Greek judicial system. I’ve earlier claimed that the ELSTAT case is a test of Greek political willingness to own up to the past and move on. The steadfast will to prosecute civil servants for doing their job exposes the damaging corrupt political forces still at large in Greece, a very worrying signal for the European Union and the International Monetary Fund – but most of all worrying for Greece.

If anyone thought that the long-running saga of prosecutions against ex head of ELSTAT Andreas Georgiou was over, just because so little is now heard of it, then pay attention: the case is still ongoing, there is an upcoming decision in the Appeals Court that could potentially send Georgiou to trial with the possibility of a life sentence for him. In addition, there are side stories here, other ongoing investigations and prosecutions.

The ELSTAT saga started after Georgiou had only been in office for just over year. It really is a saga (here my earlier reports and detailed account of it) of upside down criminal justice but it’s so much taken for granted in Greece that little or no attention is paid to the fundamental issue:

How is it possible that the man who as Head of ELSTAT from August 2010 until August 2015, putting in place procedures for correct reporting of statistics following the exposure of fraudulent statistics for around a decade, is being prosecuted and not the people who for years provided false and fraudulent statistics to Greece, European authorities and the world?

This case of a Hydra with many heads is rearing one of these heads next on 6 December when Georgiou is to face charges of violation of duty in producing the correct 2009 government deficit statistics. On important aspect is this: the charges imply that the Greek government isn’t accepting the correct figures on which the current bailout program and debt relief is based on.

European and international organisations have supported Georgiou’s point of view, the last being a letter from the International Association for Research in Income and Wealth (IARIW), to prime minister Alexis Tsipras now in November. However, the support from abroad does not seem to have had any effect on the prosecutions against Georgiou in Greece. As can be seen from the overview below of how the cases have sprawled in various directions there really is no end in sight. A worrying trend in a European democracy, the country that calls itself the cradle of Western democracy.

To Icelog, Georgiou says: “The numerous prosecutions and investigations against me and others that have been going on for years – as well as the persistence of political attacks and the absence of support by consecutive governments – have created disincentives for official statisticians in Greece to produce credible statistics. As a result, we cannot rule out the prospect that the problem with Greece’s European statistics will re-emerge. The damage already caused concerns not only official statistics in Greece, but more widely in the EU and around the world, and will take time and effort to reverse.”

Charges three times thrown out resurface in wider charges

The original criminal case concerned criminally inflating the 2009 deficit causing damages to Greece in the order of €171bn or €210bn (depending on how it was calculated on different occasions by his detractors). For three consecutive years – in 2013, 2014 and 2015 – investigating judges and prosecutors proposed to drop the case only to see the charges resurfacing again each and every time. In 2016, the Prosecutor of the Appeals Court assigned to the case yet again proposed that the case be dropped. A decision is pending at the Council of the Appeals Court.

The same issue of the 2009 deficit did indeed resurface in the form a separate, brand new case on 1 September this year, now not only alleging criminal actions by Georgiou and ELSTAT staff but by the EU Commission and the IMF. A separate criminal investigation has begun and is running parallel to the over five year old case above. On the losing end here are not only the individuals hit by these charges but also public statistics, Greece, EU and international partners.

A worrying disincentive to service truthful information

Now, on 6 December, Georgiou is facing a trial for violation of duty, exactly the violations that various prosecutors and investigating judges had, in 2013, 2014 and 2015, proposed to drop. However, the Appeals Court decided in 2015 to refer the case to an open trial. In Greece, this trial is being presented as doing justice for Greece, implying that earlier cases may have been dropped due to European pressure.

Again, this clearly shows that there are political forces in Greece refusing to shoulder any responsibility for fraudulent statistics and a huge cover up of the dismal governance in Greece up to the surfacing crisis in 2009.

If convicted for violation of duty, Georgiou faces a possible conviction of two years in prison. Greek statistics face an uncertain future: a trial against the people who fixed the problem of Greek statistics is hardly a great incentive to Greek civil servants to service truthful information instead of untruthful politicians.

Twelve months for “criminal slander”: told the truth but should have kept quiet

In June, Georgiou was tried for criminal slander for defending the 2009 deficit statistics, the very numbers ELSTAT produced as required by the European Statistics Code of Practice. The Court Prosecutor recommended to the Court that the case be dropped and that Georgiou be acquitted. But the Court ruled in the end that although it believed Georgiou to have told the truth he should still not have said the things he said and sentenced him to twelve months in prison.

The appeal of this conviction was due to be heard in October in the Appeals Court. However, the plaintiff – actually the former director of national accounts at the National Statistics Office (later ELSTAT) in 2006 to 2010, i.e. during the fraudulent reporting – succeeded in having the appeal trial postponed. It’s now due in 16 January 2017, possibly a tactical move to influence two other ongoing cases involving Georgiou, the above-mentioned criminal case and a civil case.

The civil case is related to the criminal slander case. Decision is due in the coming weeks and could land Georgiou with a crippling fine of tens of thousands of euro.

Protecting the perpetrator of a crime, not the victim

As reported last summer in my detailed article of the ELSTAT saga, ELSTAT’s former vice president Nikos Logothetis was found by the police to have repeatedly hacked into Georgiou’s ELSTAT email account. This started already on Georgiou’s first day as president of ELSTAT, in August 2010, before he had even started to look at the thorny issue of the 2009 deficit, and continued until the hacking was exposed late October 2010.

Police investigations showed who was responsible for the criminal action of hacking Georgiou’s account – Logothetis was actually logged into the account as the police came unannounced to his home.

Georgiou was informed that Logothetis would be prosecuted for this and that following the criminal case he could then bring a civil case against Logothetis. However, in early July this year Logothetis was acquitted of violating Georgiou’s email account in a felony case. The Court also decided Logothetis could not be retried for the felony charge due to the time passed since the hacking.

According to the ruling it was not disputed that Logothetis had indeed accessed Georgiou’s account. However, the action was deemed not to have been carried out because of monetary gains or to hurt Georgiou but only because Logothetis “wanted to understand Georgiou’s illegal actions and to legally defend the legitimate interests of ELSTAT and consequently of the Greek state.”

Quite remarkably, the felony case was allowed to wait for five years before it was considered by the Appeals Court, thus triggering the statute of limitations. In addition, somehow Georgiou received no notice of the decision of the Appeals Court on the Logothetis felony case acquittal and thus had no chance to take legal action to potentially reverse the ruling within the allowed one month period.

Furthermore, the Court hadn’t taken any note of the fact that Logothetis actually hacked the account before Georgiou even looked at the 2009 deficit numbers nor did it figure in the case that Logothetis had continuously slandered and attacked Georgiou during his five years in office, even calling for the hanging of Georgiou in a published interview.

Another case against Logothetis, also for the hacking but as a misdemeanor and not a felony, was due to go to trial now in November but has been postponed in accordance with Logothetis’ wishes. It’s now been set for February 2017.

The ELSTAT case in the European Parliament:

On 22 November the ongoing political pressure on Greek statistics and Georgiou and his colleagues was taken up in a hearing at the Committee on Economic and Financial Affairs of the European Parliament. Both Georgiou and Walter Rademacher president of Eurostat participated, presented their views and were questioned by MEPs.

Rademacher gave an overview of the problems with Greek statistics and emphasised the need to close with the past, stop going after ELSTAT staff and to recognise what had been wrong (see video; Rademacher at 2:20-12:15). Rademacher paid tribute to Georgiou and the ELSTAT staff in modernising the organisations, bringing the governance to the proper standard and thus re-establishing trust in Greek statistics, a much needed contribution.

Rademacher pointed out that the serious misreporting didn’t cause the crisis in 2009 but was a “blatant symptom of very serious flaws” within the Greek statistics administration “at that time.” He also underlined the immense effort taken by various organisations to aid and support ELSTAT in improving its work, inter alia hundred Eurostat missions since 2010 to the present day, around one a month, to ELSTAT as well as to Eurostat in-house assistance, to the cost of around €1m in addition to technical assistance from the IMF and other EU National Statistical Institutes – no other country has needed anything like this.

In his presentation, Georgiou (12:26-20:12) emphasised the enormous disincentive for official statistics in Greece his case has been.

“These and other cases and investigations send a strong signal to today’s guardians of honest, transparent statistics in Greece: you do so at your own risk. The point cannot be lost on them that compiling reliable statistics according to EU law and statistical principles can endanger their personal well-being.”

The ELSTAT case: a scary disincentive for Greek civil servants

Georgiou had only been in office for around thirteen months when political forces in Greece openly started questioning in parliament his professional integrity. That was also the time when allegation emerged of him committing treason in reporting the correct figures.

Now, more than five years later, the case is still going on in various ways. Quite remarkably, Georgiou has not had any support from the Tsipras government. Given how the ELSTAT case has progressed, there are clearly forces both in the government and in the main opposition party who have a personal and political interest in hiding the truth on how the fraudulent reporting was kept going for around a decade, until 2009 and who find a convenient scapegoat in Georgiou and his staff.

Given the strong Greek political forces at large here the only way to stop the scapegoating seems to be that the donor countries and institutions show Greece that it can’t be helped until it helps itself. Until it helps itself by putting an end to prosecuting civil servants who fixed a serious problem that severely undermined the trust in the Greek government. As it stands, there is no incentive for Greek civil servants to withstand political pressure for corrupt action.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

ESA finds Iceland in compliance re offshore króna measures

The EFTA Surveillance Authority, ESA, has now closed two complaints re treatment of offshore króna assets by Icelandic authority: ESA finds the Icelandic laws in compliance with the EEA Agreement (see ESA press release here, the full decision here). The disputed laws were part of measures taken in order to remove capital controls in Iceland.

I have earlier written extensively about the offshore króna issue, also the rather bizarre action taken by the so-called Iceland Watch against the Central Bank of Iceland, which rubbed Icelanders, even those sympathetic to the point of view taken by the offshore króna holders, completely the wrong way. The sound points, which can be made by the offshore króna holders, were missed or ignored and instead the Iceland Watch action was shrill and shallow, based on spurious facts.

In general EEA states are permitted, under the EEA Agreement, to take protective measures when a states is experiencing difficulties as regards its balance of payments. As spelled out in the press release the states, in such situations, “are allowed to implement a national economic and monetary policy aimed at overcoming economic difficulties, as long as the criteria for these protective measures are met.”

As Frank J. Büchel, the ESA College member responsible for financial markets sums it up: “Iceland’s treatment of offshore króna assets is a protective measure within the meaning of the EEA Agreement. The overall objective of the Icelandic law is to create a foundation for unrestricted cross-border trade with Icelandic krónur, which will eventually allow Iceland to again participate fully in the free movement of capital.”

The funds in question, Eaton Vance and Autonomy, are testing their case in an Icelandic court.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Trump and Berlusconi: why some voters prefer “a son of a bitch”

In spite of exemptions over the years it’s been taken for granted that a politician running for office should be a decent law-abiding human being. Consequently, the media has focused on exposing politicians repeatedly caught lying, womanising, making racist or misogynistic remarks and involved in shady business dealings assuming any or all of this would make politicians unfit for office. Silvio Berlusconi, longest serving Italy’s prime minister, disproved that. Now Donald Trump’s victory has shown that some voters not only don’t mind what some see as repugnant behaviour but do indeed find it appealing. – I first understood this in 2008 when I spoke to an Italian voter rooting for Silvio Berlusconi precisely because Berlusconi was ‘a son of a bitch like the rest of us!’

“Mussolini never killed anyone. Mussolini used to send people on vacation in internal exile,” Silvio Berlusconi then prime minister of Italy said in a newspaper interview in 2003. In a speech that same year at the New York Stock Exchange he encouraged investment in Italy because “we have beautiful secretaries… superb girls.” Another infamous Berlusconi comment was that US president Barack Obama and his wife must have sunbathed together since they were equally tanned. The career of the now 80 years old Berlusconi is littered with racist, misogynistic comments and peculiar understanding of history, as well as serious allegations of relations to organised crime. All of this was well known when he first won elections in Italy in 1994 as a media tycoon and the country’s wealthiest man.

It’s as yet untested if Donald Trump was right in saying he could, literally, get away with murder and still not lose voters but like Berlusconi Trump has been able to get away with roughly everything else: racism, misogyny, not paying tax – he’s too smart to pay tax and might actually never make his tax returns public – mob-relations, shady business dealings and Russian connections.

Being an Italian prime minister is next to nothing compared to being a US president. Berlusconi was in and out of power for almost twenty years, winning elections in 2001 and 2008 and losing only by a whisker in 2013. Trump can at most get eight years in power. But apart from the different standing of the two offices the two men, as a political phenomenon, are strikingly similar. Like Berlusconi, Trump was to begin with treated as a political joke.

The lesson here is that accidental politicians – accidental because they turned to politics as outsiders late in life – like Berlusconi and Trump appeal to voters not necessarily in spite of their remarks but because of them. For some voters they are a type of “loveable rascals” immune to media exposures, their spell-like influence based on their business success as if their personal success could be repeated nationwide. The almost twenty year experiment with Berlusconi did help his own businesses, not the country he was running for almost half of that time.

It’s not that all Italian or all Americans have fallen in love with the “lovable rascals:” during his time in power Berlusconi’s party got up to 30% of votes. Since half of US voters didn’t vote it took only around 25% of the voters to sign Trump’s invitation for the White House and as we know Hillary Clinton did indeed get more votes.

The food for thought for the media is that investigations and exposures only go so far. Higher electoral participation would probably help fight demagogues and racists – a worthy project for the US political parties and civil society in general.

1990s – no end to history but a trend towards merging of left and right

Berlusconi built his empire from scratch, Trump started off with some inherited wealth. Although outsiders in the political system they rose on political ties and entered into politics at times of economic upheaval. In Italy growth fell in the early 1990s, zick-zacked on and has been dismal since 2000. Trump’s victory is underpinned by stagnant wages in US for familiar reasons: globalisation, low union participation and technological changes though the exact weight of the three factors is disputed.

Malaise in the old parties both on the left and the right goes far in explaining the success of the two politicians. In Italy, the parties left right and centre were for years in a kaleidoscopic flux, and still are to a certain degree, following the collapse of the political system based on the Christian Democrats and the Socialists brought down by the end of the Soviet Union in 1991 and the ‘Mani Pulite’ corruption cases.

Berlusconi founded his own party in 1993 and conquered the Italian right-of-centre, orphaned after the demise of the Christian democrats, many of whom found a second home and political career in Berlusconi’s Forza Italia. After his first short stint as prime minister 1994 to 1995 the Italian left kept Berlusconi out of government but he didn’t give up. His time came in the elections in 2001 when he sat as prime minister until 2006, a record in post-war Italy and then again 2008 to 2011.

Trump won a double victory: first by hijacking the Republican candidacy against the party elite, then by winning over the Democratic candidate Hillary Clinton. Contrary to the outsider Barack Obama she belonged to the party elite who since the 1990s, her husband’s time in power, have embraced capitalism, light regulation and big corporation – a course that hasn’t helped to improve the lot of the lower and middle class.

As the Nobel-prize economist Angus Deaton spelled out so brilliantly in his book “The Great Escape”: when banks and private wealth fund campaigns for Republicans and Democrats both ends of the political spectrum root for the same special interest policies and the general public is left behind (the long view on the Democrats is brilliantly told here, by Matt Stoller).

Berlusconi and Trump: the “lovable rascals” framing their own political persona

As politicians have lost trust businessmen have gained greater weight in shaming politicians and public officials claiming that a country should be run like a business. Both Berlusconi and Trump have incessantly touted their business acumen to prove their political astuteness emphasising that being wealthy they can’t be bribed. In addition Berlusconi owns a famous football club in a football-besotted country.

With a party of his own Berlusconi set his own rules. Trump welcomed his loss of support among the Republican elite, claiming it unshackled him. Both were free to create their own political persona, both seem to be consummate actors. Trump changed his rhetoric from the primaries to the campaign and now seems to be interpreting his presidential role in yet another way. The controversial statements were, as Trump said on CBS’s Sixty Minutes, “necessary to win.”

It’s too simple to say that both men have found support among working class angry men. They found support among women (Berlusconi though less than Trump) and both appeal to well-off voters. The anger, now the common explanation for Trump’s success (and the Brexit outcome), hadn’t really been discovered when Berlusconi rose to power. But both men are very good at vilifying their opponents: Berlusconi stoked the fear of communism; Trump claimed Hillary Clinton was the embodiment of all the evil in Washington.

For those who find the behaviour of first Berlusconi and now Trump inexcusable and worry about aspects of their businesses, quite apart from their rambling politics, it’s difficult to understand that media investigations and exposures has little or no effect on their supporters. It’s not necessarily that their followers don’t know about the questionable sides, they often do. Some may identify with them on the premise that no one is perfect. For others, the two are some sort of “loveable rascals.”

It doesn’t mean that any kind of foul-mouthed shady business man can win support and rise to power but foulmouthed and frivolous inexperienced politicians seemed unthinkable before the rise of Berlusconi in 1990s in Italy and of Trump most recently in the US. “Lovable rascal” are exempts from the criteria normally used and critical coverage doesn’t really bite: their voters like them as they are.

Confirmed Putin-admiring sinners with strong appeal to religious voters

Berlusconi was a prime minister in a country partly ruled by the Vatican and has courted voters who support conservative family values. Also Trump has diligently appealed to devout evangelical Christians. These voters seem to ignore that Berlusconi and Trump have diligently sought media attention surrounded by young girls, Trump as a co-owner of the Miss Universe Organization, Berlusconi via his TV stations, feeding stories of affairs and escapades. Berlusconi has been involved in a string of court cases due to sex with underage prostitutes.

This paradox is part of the “loveable rascal” – the two are exempt from the ethics their Christian followers normally hold in esteem.

Both men have shown great vanity in having gone to some length in fighting receding hairline. As is now so common among the far-right both men openly admire Russia’s president Vladimir Putin. Berlusconi has hosted Putin in style at his luxury villa in Sardinia and visited Putin at his dacha. And both Trump and Berlusconi have spoken out against international sanctions aimed at Putin’s Russia.

The “I-me-mine” self-centred political discourse and mixture of public and private interests

Since their claim to power rests on their business success the political discourse of Berlusconi and Trump is strikingly self-centred: a string of “I-me-mine” utterances with rambling political messages. Both are devoid of any oratory excellence and their vocabulary is mundane.

Berlusconi’s general political direction is centre-right but often unfocused apart from the unscrupulous defence of his own interests. Shortly after he became prime minister for the second time the so-called Gasparri Act on media ownership was introduced, adapted to Berlusconi’s share of Italian media. When Cesare Previti, a close collaborator, ended in prison in 2006 for tax fraud it took only days until the law had been changed enabling white-collar criminals to serve imprisonment at home rather than in prison.

In general, Berlusconi’s almost twenty years in politics, as a senator and prime minister, were spent in the shadow of endless investigations into his businesses and private life, keeping his lawyers busy. An uninterrupted time of personal fights with judges and that part of the media he didn’t own. Journalists at Rai, the public broadcaster, who criticised Berlusconi lost their jobs and Italy fell down the list of free media.

Trump seems to think he doesn’t need to divest from his businesses. For now he is only president-elect but if the similarities with Berlusconi continue once Trump is in the White House he can be expected to bend and flex power for his own interest. Trump’s time is limited but he can take strength from the fact that just as vulgar behaviour and questionable business dealings didn’t hinder Berlusconi’s rise in politics neither did they shake his power base. Berlusconi won three elections and was in power for nine years from 1994 to 2011.

The bitter lessons of Berlusconi’s long reign

In 2011 Berlusconi his time in power was messily and ungraciously curtailed: having failed utterly to fulfil his promises of reviving the economy he was forced to resign. After being convicted of tax fraud in summer 2013 he lost his last big political fight: to remain a senator in spite of his conviction. Thrown out of the senate after almost twenty years he’s still the leader of his much-marginalised party, now polling around 12%, down from 30% in the elections 2013.

Berlusconi’s businesses went from strength to strength but Berlusconi’s Italy suffered low growth and stagnation.

We don’t know what Trump’s time in office will be like. Personally he isn’t half as wealthy and powerful as Berlusconi was – the wealthiest Italian when he first became prime minister in 1994. It’s unclear how Trump’s businesses will be run while he takes a stab at running the country. His businesses might well come under investigation and we might see a similar wrestle between Trump and investigators as the ones Berlusconi fought.

Although Italy didn’t thrive in the first decade of the 21st century, the Berlusconi era, he seemed for years invincible for lack of better options and for his promises and appeal. For the “lovable rascal” politician it doesn’t seem to matter if their promises never come to fruition or if they say one thing and do something else – their policies are not the only root of their popularity.

Democracy, lies and the media

Many Italians worried that Berlusconi undermined democracy both in his overt use of power and his own media to further own interests and the more covert use, such as putting pressure on judges and Rai journalists. Whereas Romans were fed bread and games Berlusconi fed his voters on TV shows with scantily clad girls. Berlusconismo referred to all of this: his centre-right ideas, his use of power to further own interests and the vulgarity of it all.

The palpable sense of political disillusionment in the wake of Berlusconi hobbling off the political scene in a country with depressed economy hasn’t made it any easier to be an Italian politician. The void left space for this strange phenomenon that is Beppe Grillo and his muddled Cinque Stelle movement in addition to the constant flux of parties merging or forming new coalitions.

But the political momentum is neither on the far-right Lega movement and the cleaned-up fascist party, Alleanza Nazionale nor the far-left fringe. Italian democracy after Berlusconi isn’t weaker than earlier in spite of the unashamed demagogy and his self-serving use of power. There is no second Berlusconi in sight in Italy.

Berlusconi seemed to be a singular political event but with the rise of Donald Trump Berlusconi is no longer unique. And there seem to many American voters who think like the Italian one who in 2008 told me he was going to vote for Berlusconi because Berlusconi was ‘a son of a bitch like the rest of us!’ – these voters don’t care what the media reports on their chosen politicians. Consequently, the media needs to figure out how to operate in times of flagrant lies and dirty deals from politicians who can appeal to voters in spite of what was once thought to rule out any possibility of a political career.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.