Search Results

Ireland and Iceland – when cosiness kills

The fate of the Irish and the Icelandic banks are intertwined in time: as the Irish government decided on a blanket guarantee for the Irish banks, the Icelandic government was trying, in vain, to save the Icelandic banks. In spite of the guarantee six Irish banks failed in the coming months; the government bailed them out. The Icelandic banks failed over a few days. Within two months the Icelandic parliament had decided to set up an independent investigative committee – it took the Irish government almost seven years to set up a political committee, severely restricted in terms of what it could investigate and given a very limited time. The Irish report now published is better than nothing but far from the extensive overview given in Iceland: it lacks the overview of favoured clients and the favours they enjoyed.

A small country with a fast-growing banking sector run by managers dreaming of moving into the international league of big banks. To accelerate balance sheet growth the banks found businessmen with a risk appetite to match the bankers’ and bestowed them with favourable loans. Lethargic regulators watched, politicians cheered, nourishing the ego of a small nation wanting to make its mark on the world. – This was Iceland of the Viking raiders and Ireland at the time of the Celtic tiger, from the late 1990s, until the Vikings lost their helmets and the tiger its claws in autumn 2008.

In December 2008, eleven weeks after the Icelandic banking collapse, the Icelandic parliament, Alþingi, set up an independent investigative committee, The Special Investigative Commission, SIC, to investigate and clarify the banking collapse. Its three members were its chairman Supreme Court justice Páll Hreinsson, Alþingi’s Ombudsman Tryggvi Gunnarsson and lecturer in economics at Yale Sigríður Benediktsdóttir. Overseeing the work of around thirty experts, the SIC published its report on 12 April 2010: on 2400 pages (with more material online; only a small part of the report is in English) the SIC outlined why and how the banks had failed.

In November 2014, over six years after the Irish bank guarantee, the Irish Parliament, Oireachtas, set up The Committee of Inquiry into the Banking Crisis, or the Banking Inquiry, with eleven members from both houses of the Oireachtas; its chairman was Labour Party member Ciarán Lynch. The purpose of the Committee was to inquire into the reasons for the banking crisis. Its report was published 27 January 2016.

Both the Irish and the Icelandic reports make valid recommendations. It does however make a great difference if such recommendations are put forward 1 ½ years after the cataclysmic events – or – more than seven years later.

The Irish legal restraints, the Icelandic free reins and prosecutions

As Ciarán Lynch writes in his foreword to the Irish report: “As the Celtic Tiger fell, our confidence and belief in ourselves as a nation was dealt a blow and our international reputation was damaged.” The same happened in Iceland, confidence was dealt a blow and the country’s international reputation damaged. If anything can restore trust in politicians it is undiscriminating investigations and transparency.

In one aspect, the Irish Banking Inquiry differed fundamentally from the Icelandic one: the Irish was legally restrained from naming names. Consequently, the Irish report contains only general information on lending, exposure etc., not information on the individuals behind the abnormally high exposures.

This is unfortunate because in both countries, the high-risk banking was centred on a small group of individuals. In Ireland these were mostly property developers and some well-known businessmen; in Iceland the favoured clients were the banks’ largest shareholders, a somewhat unique and unflattering aspect that puts Iceland in league with countries like Mexico, Russia, Kazakhstan and Moldova.

The SIC had no such restraints but could access the banks’ information on the largest clients, i.e. the favoured clients. The report maps the loans and businesses of the banks’ largest shareholders and their close business partners, also some foreign clients. Consequently, the SIC report made it a public information that the largest borrower was Robert Tchenguiz, owed €2.2bn, second was Jón Ásgeir Jóhannesson, famous for his extensive UK retail investments, with €1.6bn. Björgólfur Thor Björgólfsson, Landsbanki’s largest shareholder (with his now bankrupt-father) owed €865m. These were loans issued by the banks in Iceland; with loans from the banks’ foreign operations these numbers would be substantially higher.

The SIC report also exposes how the banks had in many cases breached rules on individual exposures and then actively hidden it from the regulators and shareholders.

Apart from reacting quickly to set up an investigative commission, Alþingi passed a Bill in December 2008 to set up an Office of a Special Prosecutor, OSP, which came to investigate and prosecute bankers and businessmen. So far, 21 have been sentenced to prison and a number of cases are still pending. The OSP is now part of a permanent structure to investigate financial crimes. Prosecutions have given a further insight into the banking during the boom years, i.a. exposing fraudulent lending, breach of fiduciary duty and market manipulation.

Those prosecuted by the OSP have not been sentenced for wrong or unwise decisions but for criminal behaviour. Some of these cases, at least on the surface, bear close similarities to things going on in the Irish banks, i.a. in lending which unavoidably would lead to losses since the banks were light on collaterals. Icelandic laws do differ substantially from laws in other Western countries – but in Iceland there was the will and courage to explore these practices.

A very brief overview of Ireland and Iceland in autumn 2008

The year 2008 brought increasing worries of the soundness of an over-extended banking sector both in Ireland and Iceland

In Iceland, the board of Glitnir, the smallest of the three largest Icelandic banks, was the first to ask for a meeting with the Icelandic Central Bank, CBI: on September 25 2008 the governors of the CBI learned that the bank would not be able to meet its obligations in the coming weeks. Over the following weekend, the CBI and the government decided to save the bank by taking over 75% of its shares. This was clear early Monday morning September 29, just as the Irish government was furiously debating and preparing a two year blanket guarantee for six Irish banks.

According to the Irish report the Irish government decided solo on the guarantee; the European Central Bank, ECB had made it clear that each country was responsible for its own banks but no bank should fail. Yet, ECB’s views do not seem to have been foremost in the mind of Irish ministers struggling to find a solution September 29 to 30.

In Ireland, the blanket guarantee issued in the early hours of 30 September, valid from 1am 29 September, had been discussed on and off for some time; it was not an idea that arose on the spur of the moment. But in those last days of September 2008 a decision could no longer be postponed: Anglo and INBS had run out of liquidity. The choice was either a guarantee or nationalising the troubled banks.

The Irish guarantee gave food for thought in Iceland; it was briefly outlined for discussion 2 October 2008 as one possible option but apparently not pursued further.

It only took around 48 hours for the CBI and the government to realise that Glitnir’s affairs were a mess and the bank could not be saved. The following Monday, October 6, it was finally clear that the game was over: since the government could not save Glitnir, the smallest bank, it could evidently not save the two larger banks. An Emergency Bill was passed to have a legal framework in place. By October 9 2008 all three banks had failed.

In the UK, where all the Icelandic banks had operated, the government in panic over the state of the British banking system feared Landsbanki, which by then had around £4.2bn on its Icesave accounts, was moving funds out of the country. On 8 October the UK government slammed a Freezing Order on Landsbanki, using a legislation with the word “terrorism” in its title. A confusion ensued whether the Order referred only to Landsbanki or all things Icelandic. It took weeks and months to entangle this, adding to other woes Iceland faced.

The Icelandic quick blow, the Irish lingering stab

With the banks and the financial system in ruins Iceland sought help with the IMF and by 24 October had negotiated a loan of $2.1bn, now repaid. Iceland more or less followed IMF guidelines and made full use of the Fund’s expertise. Iceland was back to growth by mid 2011, 2 ½ years after the collapse (see here my take on the Icelandic recovery).

The guarantee didn’t save the Irish banks but only extended their lives for some months. Already by January 2009, the government had to step in to save the first bank. In the following weeks and months there were five more bail-outs, i.a. of all the banks mentioned in the guarantee. As the guarantee expired 28 September 2010 the Irish state had over-extended itself in saving six banks and in December a Troika bailout had been negotiated. – Ireland was back to growth in the last quarter of 2014, after two dips from 2008.

The ECB – IMF wrestle that the ECB won

There have been stories of the role of the ECB and possible burden sharing with bondholders, which could have been the solution when the two year guarantee was about to expire. The Irish report spells out what happened: it was the ECB against the IMF and the ECB won, also because the Irish government understood that both the US and the whole of the G7 sided with the ECB.

When discussing the Troika programme in October and November 2010 both the Irish government and the IMF mission were in favour of imposing losses on senior bondholders and the legal issues had been worked out. As Ajai Chopra then deputy director at the IMF informed the Inquiry the IMF staff was of the view that the markets would both have anticipated and been able to absorb ensuing losses “and even if they were not able to absorb it, there were mechanisms to help address that contagion… Recent academic research confirms the view that spillover risks were exaggerated.”

This view ran against the view at the commanding heights of the ECB: in November 2010 ECB governor Jean-Claude Trichet made it clear in a letter that if the government insisted on imposing losses on bondholders there would be no Troika programme. Other powers agreed with the ECB: Ireland’s minister of finance Brian Lenihan knew US Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner was dead against the burden sharing. Lenihan also told governor of the Central Bank of Ireland Patrick Honohan that the leaders of the G7 countries agreed with Geithner. “I can’t go against the whole of the G7,” Lenihan said to Honohan who was of the view Lenihan saw the burden sharing as “politically, internationally politically inconceivable…”

After a new Irish government came to power 9 March 2011 the possibility of a burden sharing was again explored, especially regarding Anglo and INBS, which were no longer going concerns, but had been placed under the Irish Bank Resolution Corporation, IBRC. Noonan stated his position in a phone call to ECB’s governor Jean-Claude Trichet, who according to Noonan “…sounded irate but maybe he wasn’t irate but that’s the way he sounded and he said if you do that, a bomb will go off and it won’t be here, it’ll be in Dublin.”

When asked during a visit to Ireland in spring 2015, Trichet only referred to letters sent by the ECB, nothing more. In a letter in March 2011, Trichet threatened to withdraw Emergency Liquidity Assistance, ELA if the government went ahead with imposing a hair-cut on bondholders.

As in November 2010, the March 2011 attempt by the new Government to impose losses on bondholders, was unsuccessful. “Once again, the intervention of the ECB appears to have been critical.”

The ECB prevailed, with drastic consequences for Ireland: “The ECB position in November 2010 and March 2011 on imposing losses on senior bondholders, contributed to the inappropriate placing of significant banking debts on the Irish citizen.”

It left the Irish with a bailout cost much higher than would have been necessary. Certainly a tragic outcome for Ireland.

The pattern of collective madness

Both the Icelandic and Irish collapse could be summarised as having happened because so many got it wrong, ignored the clear warning signs and made the wrong decisions.

Ciarán Lynch sums up the Irish crisis as “a systemic misjudgement of risk; that those in significant roles in Ireland, whether public or private, in their own way got it wrong; that it was a misjudgement of risk on such a scale that it lead to the greatest financial failure and ultimate crash in the history of the State.” – Further, the banking crisis led to a fiscal crisis. “These were directly caused by four key failures; in banking, regulatory, government and Europe” after which “turning to the Troika became the only solution.”

The Irish banking crisis was caused by the banks pursuing “risky business practices, either to protect their market share or to grow their business and profits. Exposures resulting from poor lending to the property sector not only threatened the viability of individual financial institutions but also the financial system itself.”

Regulators were aware of this, yet did not respond to the systemic risk but adopted “a principles-based “light touch” and non-intrusive approach to regulation. The Central Bank, the leading guardian of the financial stability of the state, underestimated the risks to the Irish financial system.”

In spite of a period of unprecedented growth in tax revenues the government’s fiscal policy was based on long-term expenditure commitments “made on the back of unsustainable cyclical, construction and transaction-based revenue. When the banking crisis hit and the property market crashed, the gulf between sustainable income and expenditure commitments was exposed and the result was a hard landing laying bare a significant structural deficit in the State finances.

The Icelandic crisis also started as a banking crisis, with the banks collapsing. Though bondholders in the large banks were not bailed out (but they were in three smaller banks and an insurance company) significant cost accrued to the state: the net fiscal cost of supporting and restructuring the banks is 19.2% of GDP, according to the IMF. Iceland did indeed suffer at fiscal crisis: it had to be bailed out by an IMF loan.

In summarising its finding the SIC report states that the explanations of the collapse of the three largest banks can “first and foremost to be found in their rapid expansion and their subsequent size when they tumbled in October 2008. Their balance sheets and lending portfolios expanded beyond the capacity of their own infrastructure. Management and supervision did not keep up with the rapid expansion of lending… The banks’ rapid lending growth had the effect that their asset portfolios became fraught with high risk.” The high incentives for growth were found in the banks’ incentive schemes and “the high leverage of the major owners,” in addition to the availability of funds on international markets.

All of this should have been evident to the supervisory authorities, giving cause for concern. “However, it is evident that the Financial Supervisory Authority FME… did not grow in the same proportion as the banks, and its practices did not keep up with the rapid changes in the banks’ practices.”

As in Ireland, Icelandic politicians lowered taxes during an economic expansion, contrary to expert advise “even against the better judgement of policy makers who made the decision. This decision was highly reproachable.” The CBI’s calls for budget restraint were ignored but also the CBI made mistakes, such as failing to raise interest rates in tandem with the state of the economy and in lending to the banks in 2008, resulting in a loss for the CBI of 18% of GDP.

In Ireland, politicians and authorities had, without any test or challenge, adopted a ‘soft landing’ theory, as indeed had many international monitoring agencies. “The failure to take action to slow house price and credit growth must also be attributed to those who supported and advocated this fatally flawed theory.”

Though less clearly formulated, there was a lot of wishful thinking in Iceland. However, as pointed out in the SIC reports, “flawed fiscal and monetary management … exacerbated the imbalance in the economy. They were a factor in forcing an adjustment of the imbalances, which ended with a very hard landing.”

The lethal debts: commercial property in Ireland, holding companies in Iceland

Though banks thrive on debt the wrong type of debt and monoline lending can be lethal when circumstances change and the debt goes from risky to hopeless. The practices of the Irish and the Icelandic banks give some examples of how risky turns lethal.

High exposure to property was claimed to be the main risk on the books of the Irish banks. “Between 2004 and 2008 almost €8 billion worth of commercial investment property was sold in Ireland. 2006 was the peak year for investment volumes, with €3.6 billion traded in 12 months. For context, this compares to the previous record of €1.2 billion in 2005 and an average of €768 million per annum between 2001 and 2004.”

This number is however too low, according to the report, as it only refers to domestic lending to commercial property. The Irish banks funded considerable Irish investments abroad, mostly in the UK and the rest of Europe. Thus, the size of commercial property lending was larger than the domestic market indicates.

Fintan Drury, a former Non-Executive director of Anglo Irish Bank, admitted that Anglo had been “a monoline bank … somewhere between 80% and 90%” of Anglo’s loan book was related to property investment” – or specifically the high exposure to commercial property which turned out to be the most severe risk factor in the Irish banks, later causing the largest losses.

The Irish National Asset Management Agency, NAMA, was set up in 2009 in order to manage and recove bad assets from the banks the government recapitalised. As the Irish report points out the transfer of loans, from the banks saved by the state, exposed the losses. The total par value of loans to commercial property was €74.4bn for which NAMA paid €31.7bn. For the loans remaining on the banks’ balance sheets, the impairment rate of commercial real estate was 56.9%, “over three times that of residential mortgages and over twice the average of all impaired loans.”

Dan McLaughlin former Chief Economist, Bank of Ireland is of the view that lending to commercial property led to the banks needing assistance. In total, commercial property prices dropped by 67% (apparently in 2008-2009 but that is not quite clear from the context) whereas commercial property in the UK fell by 35% and in the US by 40%.

This concentration of a single asset class was seen as a major weakness in September 2008. Merrill Lynch acted as an adviser to the Irish government. During these febrile hours as the guarantee was being prepared the head of European Financial Institutions at Merrill Lynch, Henrietta Baldock wrote in an email that clearly “certain lowly rated monoline banking models around the world, where there is concentration on a single asset class (such as commercial property) are likely to be unviable as wholesale markets stay closed to them.”

In Iceland, the killer lending was to holding companies. At first sight they seemed to be in diverse sectors such as retail, food, pharmaceuticals, banking, mobile telephony and property. However, these apparently diverse companies were highly inter-linked through cross-ownership where every snippet of asset was collateralised.

In addition, both Icelandic bankers and businessmen knew during the boom that foreign banks tended to see various Icelandic enterprises, whether banks or something else, as just one big bundle: a risk to one bank or one enterprise was a risk to them all. Iceland was like one company, with a GDP as a big but not gigantic international company.

Cross-borrowing and high exposures to small groups

Both Irish and Icelandic banks tied their fortunes to a small group of businessmen. Over time, this changed the power balance between the banks and their clients. The clients were not beholden to the banks but the banks to the clients.

The amount of loans to single borrowers came as a surprise to some when the Irish lending was scrutinised. Michael Somers, former Chief Executive, NTMA, said he “was flabbergasted when I saw the size of the loans … which were advanced by the Irish banking system to individuals. I mean, they ran to billions… some individual had loans from the banking system equivalent to 3% of our GNP, which I thought was absolutely staggering.” – It turned out that the “…top ten borrowers had loans of €17.7bn with the six guaranteed banks and that was before any additional borrowings they had in Ulster Bank or Bank of Scotland Ireland.”

The above indicates one of the problems: the largest Irish borrowers most often borrowed not only from one bank for each project but from several banks. Yet, the banks apparently made no attempt to have a holistic overview of their largest clients’ cross borrowing. This created further risk for the Irish banks that directed most of their risky lending to only a small group of clients. – According to Frank Daly chairman of NAMA the impression was that the banks had been “acting “almost in isolation” from one another” showing little interest in clients’ exposure to other banks.

A case in point is INBS, one of the six banks forced to turn to the state for cover. It had “a concentration of loans in the higher risk development sector, a concentration of loans in the higher loan-to-value bands, a concentration in its customer base – the top 30 commercial customers, for example, accounted for 53% of the total commercial loan book – and a concentration in sources of supplemental arrangement fees, representing 48% of profit in 2006. Indeed, 73% of those fees came from just nine customers.” – The board was indeed aware of this but it did not feel it gave cause for concern.

Fintan Drury, former non-executive director of Anglo Irish Bank, was aware that “a relatively small number of clients who had quite a significant percentage of … of the lending, yes. Was I concerned about that? Not particularly.”

The Banking Inquiry “Committee is of the view that the banks had a prudential duty to themselves to inquire, challenge and assess hidden risks arising from multi-bank borrowing by major clients.”

As mentioned earlier, the unique aspect of the Icelandic banking was the fact that the largest shareholders and their business partners were also the largest borrowers. The SIC report drew attention to warnings from Bank of International Settlement, BIS, that banks may evaluate a borrower’s credit value differently if this person is either a key investor or a board member. In countries where supervision and legal protection for small shareholders is lacking abnormal lending to bank owners is often the case, a hugely worrying factor for Iceland.

And here is the unique aspect of the Icelandic banking practices: “The largest owners of all the big banks had abnormally easy access to credit at the banks they owned, apparently in their capacity as owners. The examination conducted by the SIC of the largest exposures at Glitnir, Kaupthing Bank, Landsbanki and Straumur-Burðarás revealed that in all of the banks, their principal owners were among the largest borrowers.” – The SIC concluded that the fact the largest borrowers in all the banks happened to be their owners “indicated a systematic pattern, i.e. that the banks’ owners had an abnormal access to funds in their own banks.”

These were i.a. Icelandic businessmen well known in the UK such as the two mentioned earlier – Björgólfur Thor Björgólfsson who owns the investment fund Novator, still operating in the UK and Jón Ásgeir Jóhannesson – in addition to the brothers Ágúst and Lýður Guðmundsson who still control Bakkavör, a major supplier to UK supermarkets.

In addition to the risk stemming from the concentration of loans to the same largest shareholders and clusters of companies connected to them and their business partners within each bank the fact that these clusters were highly leveraged in the other banks exacerbated the risk.

Signs of favour: Irish roll-ups and Icelandic bullet loans

Interestingly, both in the Irish and the Icelandic banks the favoured clients got similar types of favourable loans. In Ireland it is the “roll-ups,” in Iceland “bullet loans.” – This strongly indicates that in addition to high exposure and high concentration, financial supervisors should keep an eye on the types of loans issued.

Rolled-up loans transferred to NAMA amounted to €9bn, out of a total of the €74.4bn transferred. The Irish roll-up “refers to the practice whereby interest on a loan is added on to the outstanding loan balance (“rolled-up”) where it effectively becomes part of the loan capital outstanding and accrues further interest. “Rolling-up” interest would generally allow a borrower not to repay interest as it falls due, but this would be done without placing the loan in default.”

The roll-up offered was either an “interest repayment holiday” agreed in advance as the loan was issued or it was a later offer when the borrower had been unable to meet the agreed interest repayment; a sign of the bank’s lenience or its loss of control over the borrower.

According to NAMA’s evidence the existence of these interest roll-ups did not come as a surprise. The surprise was to discover how extensive they were, especially finding that “new loans were being created to take account of the rolled up interest.”

Added to a narrow group of borrowers, their narrow field of investments and high exposures related to these few individuals with monoline investments, roll-ups are a clear sign of concern. At the Banking Inquiry, Gary McGann, Independent Non-Executive Director at Anglo, was asked if with regards to the roll-up “with such a narrow field of individuals did the bank consider that in terms of risk.” His answer was: “Not specifically.”

The Icelandic bullet loans would normally be paid up in one instalment at maturity with the interest rates paid at regular intervals during the life-time of the loan. There were however many examples, especially as the credit crunch hit the leveraged borrowers, of the loan being “rolled up” and everything paid at maturity, both the loan and interest rates. At this point, paying one bullet-loan with a new one became common.

In theory, issuing bullet loans can make sense. However, by extending bullet loans losses can be hidden and that is just what happened in the Icelandic banks. Bullet loans were also a common feature of the US Savings & Loan crisis in the 1980s.

Lending on “hope value” and lack of expertise

At the Banking Inquiry Brendan McDonagh CEO of NAMA pointed out gave that the “banks were quite clearly lending to individuals and companies that, notwithstanding the massive sums involved, had little or no supporting corporate infrastructure, had poor governance and had inadequate financial controls and this applied to companies of all sizes.” In the case of around 600 NAMA debtors “…very few of them seemed to have any expertise in construction.”

Frank Daly mentioned “…lending on hope value…” where the lending related to “land which wasn’t even zoned, which had hope value more than anything else.”

There are also many Icelandic examples of these two features identified in the Irish report: lending on value that had not materialised or even was not clear would ever materialise – and lending to people who had no expertise of the type of projects on which they were borrowing.

The lack of expertise was not something Landsbanki held against the Icelandic businessman Gísli Reynisson when the bank lend him funds in spring 2007 to buy Copenhagen’s most prestigious hotel, D’Angleterre, as well as a second hotel and two restaurants, all in prime locations. Reynisson, who died in 2009, proudly stated to the stunned Danish media that he had indeed no experience of running hotels and restaurants but the opportunity seemed too good to pass on. While buying these Danish trophy assets he was also busy buying every fishmonger in Reykjavík. His earlier activity had mainly been properties and food production in Eastern Europe and the Baltics.

Another unique aspect of Icelandic lending to the banks’ favoured clients, i.e. the large shareholders and their business partners, was the consistent over-pricing, in the range of 10-20%: the clients would very often buy assets above asking price or above the value of these assets. Consequently, the banks persistently lent above value. The Icelandic businessmen invariably explained this by claiming over-paying was a way to shorten the negotiation time and time being money this made sense in their universe.

Whatever the real reason was, this over-pricing and consequent over-lending seems to be an Icelandic version of “hope value.” But it also meant that when asset prices started to fall both the borrowers and the lenders were far more vulnerable than if the assets had been keenly and more realistically priced.

All risk to the bank, little or none to the borrower

Both in Ireland and in Iceland the banks, with little else in mind than growth at any cost, fought fiercely over the clients with the biggest deals. In both countries this seems to have led to deterioration in both lending criteria and general banking practices. Interestingly, the net effect was the same in both countries: the risk fell on the lender, not the borrower.

The Irish report points out that the effect of this deterioration was that the banks provided the real funding whereas the equity from the borrower “usually existed only on paper.” As Frank Daly explained: “The result is that the borrower was typically not the first to lose. In the event of a crash the banks stood to take 100% of the losses, and that’s what happened.”

The same kind of lending to favoured clients in the Icelandic banks was common. Concentrated lending, both in terms of sectors and clients, constituted a huge risk in the Icelandic banks, effectively absolving the clients of risk. As stated in the SIC report: “…if a bank provides a company with such a high loan that the bank may anticipate substantial losses if the company defaults on payments, it is in effect the company that has established such a grip on the bank that it can have an abnormal impact on the progress of its transactions with the bank.”

In some cases brought by the Icelandic OSP, the charges relate to loans where the collaterals seemed to be weak or non-existent already when the loans were issued. Loans by Kaupthing to a group of under-capitalised or “technically bankrupt” (a description used in court by one of those charged) companies, leading to a loss of €510m for Kaupthing is one such example.

Partially blind auditors, passive regulators

Both in Iceland and Ireland it was evidently the biggest auditors, the international big four – Deloitte, EY, KPMG and PwC – that audited the banks. The two reports point fingers at the auditors: the audited accounts did not reflect the mounting risk. Both in Iceland and Ireland the banks were large clients of the auditors with all the implication it entails. All of this was going on in the realms of passive regulators.

As the Irish banks were concentrating their lending in 2007 and 2008 “to the property and construction industry at record rates, there were few “notes to the accounts” informing the reader of the potential risks involved with this strategy. Therefore, the audited accounts provided little information as to the implications of the risks undertaken.”

The Irish auditors’ riposte is that it was neither their role to advise clients on risk nor to challenge the banks’ business model. – That seems to be beside the point: the serious flaw in the auditors’ work was that leaving aside the auditors’ opinion of the risk and business model, the audits didn’t give the correct information on the banks’ position.

What made the situation worse was the long-standing relationships between the banks and their auditors: “In the 9 years up to the Troika Programme bailout, KPMG, EY and PwC not only dominated the audits of Ireland’s financial institutions, but they audited particular banks for extended, unbroken periods.”

On the regulatory side “there was passivity.”

According to the SIC the auditors did not “perform their duties adequately when auditing the financial statements of” 2007 and 2008. “This is true in particular of their investigation and assessment of the value of loans to the corporations’ biggest clients, the treatment of staff-owned shares, and the facilities the financial corporations provided for the purpose of buying their own shares. With regard to this, it should be pointed out that at the time in question matters had evolved in such a way that there was particular reason to pay attention to these factors.”

As to the Icelandic regulator, FME, it “was lacking in firmness and assertiveness, as regards the resolution of and the follow-up of cases. The Authority did not sufficiently ensure that formal procedures were followed in cases where it had been discovered that regulated entities did not comply with the laws and regulations applicable to their operations… insufficient force was applied to ensure that the financial corporations would comply with the law in a targeted and predictable manner commensurate with the budget of the FME.”

Cosiness and corruption

The Irish know a thing or two about corruption: the Mahon tribunal (1997-2012) and the Moriarty tribunal (1997-2011) did establish that leading politicians, i.a. Bertie Ahern, Charles Haughey og Michael Lowrie, received money from businessmen who profited from governmental favours. Consequently, corruption is a topic in the Irish Banking inquiry.

Nothing similar has ever been established in Iceland. The SIC did investigate loans from the three big banks to politicians. The highest loans are mostly related to spouses and nothing conclusive can be drawn from these loans.

There is however a striking Irish and Icelandic parallel in the cosy relationship between politicians and businessmen. In tiny Iceland these relations often stem from being the same age and having gone to the same schools, through friendships unrelated to business and politics or through family ties of some sort, either direct or indirect, through spouses or close friends.

Elaine Byrne, Consultant to European Commission on corruption and governance and well known in Ireland for her fight against corruption, pointed out the indirect aspect of cosy relations: “often … it is indirect and is a case of doing someone a favour and thereafter, down along the line, that person will return the favour in an indistinct way.” Doing it the old-fashioned way, with money is traceable, relationship is less so. “What the Moriarty tribunal in particular exposed was benefits in kind through different land transactions that may have arisen.” Benefits could later follow decisions. “Corruption is not black and white and is not direct. It is indirect and these relationships are very difficult to examine.”

The journalist Simon Carswell also mentioned what he called the “extremely cosy” relationship, on one hand between individuals in “the property sector, the construction industry, government, certain elected representatives and the banks” and on the other hand “the relationship between the Government, the banks and the financial supervisory authorities.” Carswell underlines a feeling among these parties of being on the same bandwagon leading to group-thinking within these institutions.

“These relationships appear to have been too cosy to have allowed any one of these collective groups, be it banks, government, builders or regulators, to shout stop and offer the kind of critical dissent that might have changed the behaviour of all and the direction in which the country was heading… contrarians were ridiculed, silenced or ignored to ensure the credit fuelled boom continued for years as their past warnings did not come true.”

The crisis would have been less costly and less severe, says Carswell, if someone belonging to these groups had had the courage to point out the dangers but these parties had it too good and were making too much money to speak out. The cost of the banking bailout is normally said to be €64bn but Carswell maintains that to this figure should be added losses on loans in all of the Irish banks, “well in excess of €100 billion, including tens of billions of euro covered by the UK Treasury. This is sometimes forgotten.”

The Banking Inquiry points out the cosiness in “the relationship banking, where some developers built strong relationships with particular banks, was a part of the Irish banking system. In some cases, both parties became business partners in a joint venture.”

There were also numerous Icelandic examples of joint ventures between the banks and their large clients. Nothing wrong per se and commonly found but also a potential basis for corrupt practices where joint ventures turn into a way of giving the chosen clients favourable treatment, i.e. with the banks giving these clients loans with no or little guarantee to fund their joint ventures.

Conclusions

It is abundantly clear that there were many signs of danger both in Iceland and Ireland prior to the banking collapse in these two countries. The pertinent question is if the proper lessons have been learned so as to prevent another similar future crisis. If read instead of buried the two reports do indeed provide a healthy antidote.

It was however not only the bad – and in proven cases in Iceland, criminal – practices that felled the Irish and the Icelandic banks. It was also the inherent risk of fast growth with regulators not keeping up and not realising the risk. In Iceland, the size of the banking system relative to the GDP topped at 10 times the GDP in early 2008, from around one GDP in 2002, around 150% of GDP in June 2015. In Ireland the banking system reached around eight times the GDP in 2008, is now just under five times. – The risk of the banking sector’s size might still be lingering in Ireland (and elsewhere!); this risk of a sector being so big that parliament and government tend to lack courage to set sensible limits to the financial system.

The Icelandic SIC allowed mining the banks’ accounts, also exposures to specific individuals, i.e. the banks’ largest shareholders and their business partners. This has given a keen understanding of how the banks really operated: by serving their largest shareholders way beyond reasonable risk and way beyond what other clients could expect. This was banking on and with a chosen circle that the banks helped to enrich.

One reason why it is important to make this information public is that it also explains why these individuals have done well after the banking collapse. Yes, they went through difficult times as many of their entities did fail but cleverly constructed company clusters, all with offshore angles, did make it possible for them to keep at least some of their assets showered on them as favours in an unhealthy banking system. It is no coincidence that many of the favoured clients are still operating, both in Iceland and Ireland.

*As can be seen on my blog I have often blogged on Ireland. Here are my blogs on the earlier reports on the Irish collapse: mentioning Regling and Watson but mainly on the Honohan report, as well as the report by Peter Nyberg in 2011. – Here is an excellent overview on the Banking Inquiry conclusions and recommendations, by Daniel McConnell.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

New indictments against Kaupthing managers

Last week, the Office of the Special Prosecutor initiated criminal proceedings against three Kaupthing managers for breach of fiduciary duty. The managers are Sigurður Einarsson formerly chairman of Kaupthing, its CEO Hreiðar Már Sigurðsson and Kaupthing Luxembourg managers Magnús Guðmundsson.

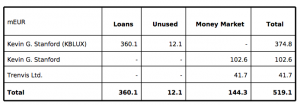

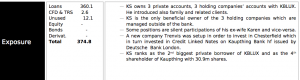

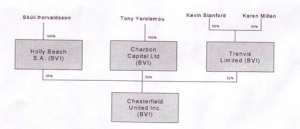

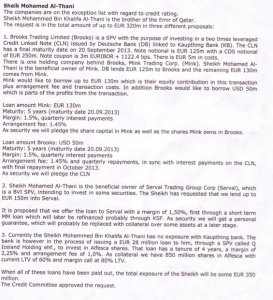

At stake are loans to four companies, in total €510m, owned by Ólafur Ólafsson, the bank’s largest shareholder, Conservative party donor and at one time a Kaupthing board member Tony Yerolemou and two big clients of the bank, Kevin Stanford and his ex-wife Karen Millen. The loans were used to fund two companies, which traded in Kaupthing’s CDS, in order to encourage a fall in the CDS and reduce the bank’s financing cost. These CDS deals were done in cooperation with Deutsche Bank. None of the clients nor Deutsche are under investigation at the OSP in relation to this scheme.

The loans were issued to BVI companies with little or no other assets than the financial assets, which were being funded. In some cases Kaupthing issued loans to these companies without the knowledge of their owners. According to the claims, the loans were not taken up in the bank’s credit committees nor were credit committees told of previous loans to these companies.

Although there are higher sums at stake in two large market manipulation cases against Kaupthing and Landsbanki managers – cases that consist of actions stretching over some time, this latest case is the largest single case so far and is likely to remain so. So far, all the OSP cases relating to the collapse of the banks are stories already known from the SIC report, published in April 2010 and this CDS case is no exception.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Debt “Correction” outlined – but funding (still) a pie in the sky

The “Correction” – that is the nickname now given by the Icelandic government to its planned debt relief. It could potentially cut ISK150bn, ca 9% of GDP, 920m, off the private mortgage stock; the maximum amount on each mortgage will be ISK4m (cf press release here in English). Of the ISK150bn ISK80bn is expected to be written off, according to certain criteria, whereas ISK70bn is estimated to come from tax relief as the Treasury waives taxes on payments used to pay down mortgages instead of paying towards a private pension. It effectively means that the Treasury is guaranteeing to pay the mortgage companies ISK150bn over the next four years.

At a press conference today to introduce the long-awaited and much promised debt relief prime minister Sigmundur Davíð Gunnlaugsson said that these measures will herald a new beginning for Icelandic families. However, Iceland did indeed turn to growth already by mid 2011 and has been in growth since.

Minister of finance and leader of the Independence Party Bjarni Benediktsson estimated that the cost of the collapse of the Icelandic banks now amounted to ISK200bn (GDP ca 1700bn). Since the cost is so great – and more could be coming – something should be done for homes, or so he said, to correct the hit that households took when the inflation rose, as a consequence of the sinking króna 2007-2010. Much was said about justice and fairness at the meeting, less on how this is going to be funded.

So far, the focus has been on not increasing the sovereign debt or risking the Icelandic credit rating. This is what the press release states on the funding: “The action requires the Treasury to serve as an intermediary in financing and implementing it. There is no need to establish a debt relief fund, as the action will be fully financed.”

This stipulates that contrary to what the government has said before, the state is indeed responsible for financing the new plan. And contrary to what the prime minister has been saying for a long time the funding is not coming from the winding-up process of the estates of Glitnir and Kaupthing. Funds he has earlier said could easily and justifiably be within the reach of the government.

According to (as I understood it) Benediktsson and chairman of the debt relief working group Sigurður Hannesson (here are his slides, in Icelandic) the methodology is that after calculating the amount each loan can be written down by, this amount is put apart – by middle of next year – and will then be paid off over 4 years by the Treasury. Thus, from mid next year each mortgage holder, fulfilling the criteria, will only paying off the written-down mortgage.

As to the Treasury, this new liability will be paid off with a new banking tax, levied on both operating and defunct (i.e. estates) banks. For operating banks deposits are the base, for estates the claims. The tax on the estates was tentatively announced when the 2014 budget was presented this autumn. At the time, the outline was unclear. The estates have indicated that there is no tax base in estates of collapsed banks and will most likely challenge the proposed tax.

As Benediktsson pointed out, some years ago a new bank tax was put on operating banks, annually bringing ISK1bn in for the Treasury. In comparison, the proposed tax is calculated to bring the Treasury ISK37.5bn next year.

It may all come down to semantics but a plan that partly relies on a disputed tax, which might be ruled illegal, can to my mind not be judged to be funded. And since the Treasury is an intermediary in a potentially unfunded plan it is taking on some risk – some added risk. Also, if the estates are to be used as a tax base for the next four years, the government seems to be underlining that they will not be wound down and assumedly the capital controls kept in place.

As to the effect on the economy it is both said to be only mild – and to be beneficial for consumption and growth. It will add 3.7% to inflation over 4 years, not trivial in a country with chronic inflation. Greater consumption will increase imports, with the unavoidable negative impact on the current account and the króna rate. It is forecast to stimulate the property market, which some already see as showing signs of overheating. That is good for the construction sector but less for other sectors. The measures are not thought to stimulate investment and the export sectors, which is what is needed to boost the current account, which again is needed to abolish the currency controls. – So far, there is no comparative analysis of what these ISK150bn could do for the country if used i.a. to pay off sovereign debt or for some infra structure projects.

Still plenty of question marks, these are just my first impressions – and they might change as more is revealed of the plan.

As pointed out on Icelog earlier, some Independence Party MPs had earlier indicated skepticism. I have heard of some discontent within the party. An ex-leader of young conservatives has already said the plan is worse than he expected. How the plans fare in parliament will not be clear immediately since the Bills needed to put this plan into action are not yet written.

Update 1.12. 2013:

*Clarifications: the mortgages now being “corrected” are not currency loans but indexed loans that jumped up when inflation rose 2007 to 2010. Currency loans (or some types of currency loans) have earlier been deemed illegal. Banks, which had issued these loans, have had to recalculate them and write-down substantial amounts. The two ministers introducing the new measures have said that it now is time that the banks, which behaved so badly before the collapse, should shoulder some of the burden. In reality, the banks have already been hit by write-downs resulting from the currency rulings. – The banks now functioning are not the old banks but new banks created with deposits from the old banks.

*Here is the legal opinion from the Kaupthing estate to the Icelandic parliament re taxing bank estates. Given that both Glitnir and Kaupthing doubt the estates constitute a legal base the coming measures will most likely be challenged in court. It will be intriguing to how the courts, first the Reykjavík District Court and then the Supreme Court, rule in a case where the government has already acted on its own assessment of the legality of these actions.

Update 4.12. 2013:

According to IFS Greining, the Icelandic CDS has jumped up 11% since the weekend. That is at least an indication of how market forces outside of Iceland view the ,,correction.” Unfortunately, I do not have a link to this since the IFS website is behind a payment wall. – It is most likely that the fact that the funding is not secure, that it will hit the Housing Finance Fund, already deemed a sovereign risk by IMF and others and that the Treasury is a de facto guarantor has an effect on the CDS.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Iceland: capital controls, government action – and (possible) creditor counteractions

There is yet no clear plan in sight as to how to deal with the estates of the failed banks and, eventually, lifting the capital controls in Iceland. However, the fact that the government has declared it intends to use a given “wind-fall” from the estates indicates that there is a certain wish(ful thinking). The question is how this “wish” will materialise – and most of all, if the creditors will stage some counteraction, either as a group or single creditors, to seek to claim their foreign assets in foreign courts.

“I hope to see you and your money! in Iceland,” said prime minister Sigmundur Davíð Gunnlaugsson at the end of his speech at “Iceland Investment Forum” in London September 19. His words were met with laughter, more nervous than merry. Many of those present are creditors to the Icelandic banks, possibly not eager to invest more in Iceland until the fate of their last investment is clear.

In his speech the prime minister sought to stress that Iceland was keen to receive foreign investors in Iceland. “My government understands that vibrant business and industry is the basis of growth and welfare. We, therefore, welcome investments in Iceland and are willing to create an environment that is conducive to your needs as investors.”

Interestingly, last Saturday the prime minister said on Rúv that Iceland was not necessarily in need of foreign investments. Although foreign investment might in some cases bring the added value of knowledge, it was essentially a foreign loan; foreign investors just intended to get more out of their investments than they put into it. – An interesting insight into the PM’s business acumen.

In his London speech the prime minister did air his so oft repeated statements of the “leeway” in the estates of the fallen banks:

This brings me to my fourth point, namely the necessary settlement of debts of failed financial undertakings and assets of insolvent estates. My government intends to take advantage of the leeway, which inevitably will develop in tandem with the settlement of the insolvent estates, to address the needs of borrowers and persons who placed their savings in their homes. I have described this as a win-win situation as these settlements will allow us to lift the capital controls to the benefit of the creditors and borrowers alike.

The intriguing question for creditors is what this means for their recovery.

Spending time in Iceland recently I sought to gather impressions on a possible plan regarding the estates. My feeling is that this win-win situation will mostly apply to the government. For the creditors it might be more lose-lose in terms of their Icelandic assets though everyone with interests in Iceland will eventually win-win by having the capital controls lifted.

No doubt the creditors are aware of this – and might be contemplating their next move. In total, the claims against the three estates run to ISK7836, €47.6bn. The three estates hold ISK2750bn, €16.7bn. The difference is what the creditors have already lost.

So far, the estates’ foreign assets amount to ISK1793 bn, €11bn (Central Banki of Iceland, CBI Financial Stability 1, 2013, chapter viii). Of this sum, 57% is liquid funds. Although these are foreign assets, to a large extent held abroad and do not threaten the financial stability of Iceland, the CBI has not allowed them to be paid out, thus securing that Icelandic authorities keep an upper hand in the wrangle over the estates.

The Icelandic upper hand could however quickly turn limp if the foreign creditors, either as a group or single creditors, would choose to test their luck abroad. The fact that the government has only yesterday levied tax on the estates, could possibly instigate legal action, in this case from the estates themselves.

Below, I will try to go through issues related to the capital controls as things stand now. The topics of interest are the Landsbanki bonds, a recent Supreme Court ruling in Iceland regarding old Landsbanki, LBI, guesses as to what the government might be contemplating and what the creditors might be contemplating.

The reality behind the Landsbanki bonds

The three failed banks – Kaupthing, Glitnir and Landsbanki – were, each of them, split in two parts. Not bad and good bank, as might have been logical, but into an domestic operating bank, overtaking domestic, i.e. Icelandic, deposits and other domestic assets and liabilities and then an estate holding foreign deposits and other foreign assets and liabilities. Thus there are the three estates – LBI, Glitnir and Kaupthing – and respectively the new operating banks, Landsbankinn, Íslandsbanki and Arion Bank. The two latter are owned by the estates, i.e. the largest assets of the tow old banks are the two new banks whereas the state owns Landsbankinn.

Because of Icesave – the Landsbanki internet accounts set up in the UK and the Netherlands 2006 and 2008 – the main creditors of LBI are the deposit guarantee schemes of these two countries, both with priority claims. To some degree there is an overlap between the general creditors of the three banks. Around half of the creditors are the original bondholders; the rest has bought claims on the secondary market.

Due to uncertainties regarding Landsbanki assets, the new bank, Landsbankinn, eventually issued two bonds to LBI, to be paid in 2014-2018, mostly in foreign currency. It has been clear for a while that the scheduled repayments are too steep for the economy, i.e. LBI does not holds enough foreign currency to cover the repayment and there is not enough left on the current account for it to buy from the CBI.

The payment schedule is: 2014 ISK17bn, €100m, then ISK60-74bn, €360-450m, the next three years, having then paid the bonds in full 2018. It is disputed how much is needed. The numbers flying around have ranged from ISK50bn, €300m to 200bn, €1.21bn. This does not mean the new bank doesn’t have the funds to pay. It does, but not in foreign currency.

Under normal circumstances, a bank never pays up all its debt in full but refinances. As things are now, that is not a realistic option for any Icelandic financial firm – Icelandic financial companies do not have access to sustainable funding. That could change but for the time being the option is not there.

The Landsbanki bonds, its stakeholders and a step towards abolishing capital controls

After some wrangling between Landsbankinn and LBI, echoing in the Icelandic press this summer, the two entities have now entered into negotiations “on possible adjustments” to earlier settlement regarding the bonds (press release here).

The outcome will be interesting for several reasons: it will remove a certain threat, explained above, to Landsbankinn and its owner, the Icelandic state; it will indicate positions of those negotiating the bonds – and it is a first big step, regarding the estates, towards abolishing the capital controls. The numbers at stake here are considerable: the expected recovery of LBI is now ISK1531bn, €9.29bn with priority claims at ISK1325, €8.04bn. This leaves ISK206bn, €1.25bn, for general claims.

The management of Landsbankinn seems to have felt that LBI was not being very forthcoming in negotiating. On the LBI side the priority creditors, essentially the Dutch and the British governments, certainly have a lot to say on this issue.

The Dutch and the British governments stand to recover their Icesave compensations, i.e. minimum compensation of €20.000 for each depositor. They have already recovered 53.9% of what they expect to get, paid out in three instalments. However, it makes quite some difference to them if they recover everything by 2018 or have to wait considerably longer.

From what I understand there is still some pent-up Icesave irritation among the Dutch and the British negotiators. But the general creditors have also been vocal on rescheduling. Although they stand to get “only” ISK206bn, this is money as well. But since general claims are not paid out until priority claims have been paid out in full, any extension of the Landsbanki bonds will mean that their waiting is prolonged.

The CBI views the rescheduling as the first firm step towards abolition of the capital controls. Many of the general creditors are also creditors to the two other banks, making the Landsbanki bond negotiation interesting in terms of issues that need to be settled re the two other estates. The Landsbanki negotiations can thus be seen as a dress rehearsal for the full performances to come.

Landsbanki bonds – possible solutions

It is clear to everyone involved that the Landsbanki bonds need to be extended. The prospect of the Icelandic economy will be debated, in terms of what could possibly be set aside of foreign currency towards bond payments but also to what extent Landsbankinn could possibly refinance its debt. All of these issues will be mulled over by those negotiating the rescheduling, in addition the more specific terms and conditions of the bonds themselves.

In Iceland, it has officially be mentioned that the rescheduling needs to be “a few years” but that seems far too optimistic. Ten or 15 years seems a more reasonable number. As it is now, the interest rates are low, which means that interest rates will no doubt be negotiated.

Landsbankinn and its owner, the state, are obviously unwilling to see the bank fail. With the bonds being a sizeable chunk of the LBI assets, its creditors are no doubt adamant to secure that the bonds get paid – if not on time then in the foreseeable future.

It is however very difficult to imagine that LBI will agree to any extension unless the creditors get something substantial in return. The intriguing question is what this “substantial” could be. An obvious bit would be a substantial up-front payment. Steinþór Pálsson CEO of Landsbankinn has already mentioned (in Icelandic) a sum of ISK70bn, €420m.

Another – and a truly interesting “substantial” – would be for the LBI to get a permission from the CBI (which has to agree to all payments) to pay out all the foreign assets of the LBI. The reason this is so interesting is that so far, none of the estates have paid out any of the foreign assets, although they, as pointed out above, to not threaten financial stability in Iceland.

At a meeting in London September 26 possible solutions were introduced. It is a pure guess as to what exactly has been offered to the LBI but it is difficult to imagine that the creditors will not try to use their bargaining position to get their foreign assets paid out.

And it is also clear, that the prime minister and Bjarni Benediktsson minister of finance, representing Landsbankinn’s owner, will need to accept whatever solution is negotiated. It must be equally likely that only a solution that the owner accepts a priori will be seriously discussed.

The two tales of a Supreme Court judgment re LBI

September 24, the Icelandic Supreme Court ruled in a case (553/2013) brought by creditors of LBI, both priory and general claimants and the Icelandic state against the LBI. The case centred on how partial payments in foreign currency should be calculated, i.e. what ISK exchange rate should be used. The LBI had used the exchange rate on April 22 2009, the date when the winding-up proceeding commenced. The Reykjavík District Court had originally ruled in favour of LBI but the Supreme Court reversed that ruling.

This case has been interpreted in two distinctly different ways in Iceland, basically spinning two different tales.

The first one is a low-key tale: this ruling brings no fundamental changes. It points out, what was already known, that once the winding-up proceedings starts the assets in an estate holding foreign assets are converted into ISK, for accounting purposes. An estate can – but does not need to – pay out in foreign currency. The exchange rate for payment in foreign currency should be the rate on the day of the payment. This is how several lawyers have interpreted the ruling in the Icelandic media.

The other interpretation is a more sensational tale, so far mostly heard from politicians, i.a. the minister of finance: this ruling is a fundamental confirmation that the estates are in ISK and should only pay out in ISK.

It is interesting that both creditors and the Icelandic state supported the conclusion of the Supreme Court. The motive behind the state’s view is a remnant from the Icesave case where it held the view that the exchange rate on payment day should be used, hoping in due course to gain from ISK appreciation, as a set-off against the interest rates.

Is paying out the estates in ISK the way out of the ISK dilemma?

As mentioned above, the three estates hold ISK2750bn, €16.7bn, of which 2/3, ISK1800bn, €11bn is in foreign assets and 1/3 is ISK assets. This 1/3 is part of the problem that the capital controls keep at bay: there is not, and will not be in the foreseeable future, enough foreign currency to convert these (and some others) ISK assets, owned by foreigners. This problem is further crystallised by the fact that 5% of the claims are domestic, 95% foreign whereas 33% of the assets are domestic, 67% foreign (Central Banki of Iceland, CBI Financial Stability 1, 2013, chapter viii).

Listening to politicians following the Supreme Court judgment, it sounds as if paying out all of the assets of the estates in ISK, the total ISK2750bn, would be the solution to the ISK problem. A priori, as seen from the numbers above, paying all out in ISK can hardly be a solution to anything but only make a huge problem utterly humungous.

Unless, of course, something else is done as well, such as offering the creditors, now holding nothing but ISK, a certain exchange rate in order to exchange their Hvannadalshnjúkur (the highest summit in Iceland) of ISK into foreign currency, with the government then having found its frequently mentioned “leeway” there. More on that below.

As an Icelandic lawyer (not working for the creditors) said recently: “If Iceland wants to remain on good terms with the outer world the estates will be allowed to pay out their foreign assets in the foreign currency they own,” meaning that the ISK problem needs to be solved separately.

Glitnir, Kaupthing and composition

Glitnir and Kaupthing have both applied for an exemption from the capital controls, under the Foreign Exchange Act No. 87/1992 in order to proceed with composition. In this respect, composition means that the estates will be run as holding companies, working on recovering and realising assets on behalf of creditors and eventually paying out the funds recovered.

From the point of view of creditors this process is preferable to bankruptcy proceedings because a bankrupt estate needs to sell off assets in a shorter time. One of the comments heard in Iceland after the LBI ruling was that bankruptcy would allow for all assets to be paid out in ISK. This is however wrong. There is no difference as to payment between composition or bankruptcy.

Both Glitnir and Kaupthing sent an application for composition to the CBI before end of last year. CBI has not answered but following a query this summer from Glitnir, the CBI has now answered Glitnir in a letter September 23. The bank emphasises that analysis of the situation of the Glitnir estate is on-going, both within the bank and the estate.

Although a detailed analysis is not yet complete, it is clear that the Central Bank of Iceland cannot give a positive answer to the Glitnir winding-up committee’s exemption request without a solution concerning the assets that, other things being equal, will have a negative effect on Iceland’s balance of payments when they are disbursed to creditors, 93.8% of whom are non-residents, as is stated in Central Bank of Iceland Special Publication no. 9. Reference is made here to the classification of creditors, to Glitnir hf.’s króna assets (including shares in Íslandsbanki), and foreign-denominated claims against domestic parties. In order for the Central Bank to be able to grant an exemption for the above-mentioned composition agreement, there must be a solution concerning these assets, so that Iceland’s balance of payments and planned capital account liberalisation provide scope for disbursement to foreign creditors. It is important to emphasise that this is not a matter for negotiation. Either this condition is fulfilled, or it is not. Glitnir’s exemption request does not fulfil this condition at present.

In view of the foregoing, the Central Bank considers that there are no premises for setting up a process of the type proposed in the winding- up committee’s letter, and certainly not one subject to binding time limits. It is the role of the Glitnir hf. winding-up committee, in connection with its exemption request, to create the conditions that allow for the approval of an application for a composition agreement. As before, the Central Bank of Iceland is prepared to assess whether it is likely that specified options fulfil the above-mentioned conditions. If the Glitnir hf. winding-up committee has developed ideas of this type, as is asserted in its letter, the Bank is ready and willing to discuss them.

This letter indicates that the estate – and this would assumedly apply to Kaupthing as well – will need to come up with a solution on the ISK assets. The CBI is not going to negotiate though it seems to indicate willingness to engage in assessing if conditions are met or not.

Creative taxing: taxing estates of financial companies

The first action taken by the new coalition government, in power since May, regarding the estates of the fallen banks is a tax on the estates of failed financial companies, announced October 1 in the budget proposal for 2014. Bank tax will be increased from 0.041% to 0.145%, levied on all licensed financial companies, operating or in winding-up proceedings.

At first sight, this might seem to indicate all financial companies in winding-up proceedings, i.e. the three estates but also other failed financial companies such as Saga Capital, VBS, Icebank and some saving societies. However, according to the FME (Icelandic FSA) website over licensed financial companies there is only one such licensed company, now in winding-up proceedings, LBI. The other failed financial companies have all lost their licensed status and are mere holding companies.

The idea was hardly to tax only LBI but as the proposal stands, the tax apparently only hits LBI. If the tax should cover the other estates the proposal, as far as can be seen, needs to be rewritten or clarified along the lines of “companies, which were once licenced/licensed before/after anno XXX as financial companies…”

Taxing estates is, I’m told, normally not done and has, to my knowledge, never been the practice in Iceland, anymore than in other countries. Lawyers have mentioned that a tax on failed companies could be seen as an expropriation. The ministry of finance has definitely shown remarkable creativity here.*

What the government wants – all of the ISK assets and/or even more?

It is safe to conclude that the Progressive Party was voted to power on the basis of its election promises of finding a “leeway” in the estates of the collapsed banks in order to provide what the prime minister has called the most extensive debt-relief in the world. He has been unwilling to mention any numbers but one persistent number is ISK300bn, €1.8bn.

The debt-relief has been widely criticised, i.a. because of inflationary effects, by economists. It also goes against promises of the Independence Party of a sustainable fiscal policy and paying down public debt.

The government and some businessmen have been pointing out lately that it is wrong to portray the problem of capital controls as touching solely creditors locked in with their assets in Iceland. All Icelanders are locked in. Consequently, drastic moves are needed to abolish the controls.

It now seems that one of the solutions possibly contemplated by the government is to “take over” all the ISK assets and possibly some of the foreign assets – though how this would be possible is still unclear. The motive for this drastic move is that the Icelandic current account will not, for the many coming years, allow for any foreign currency to be used to convert ISK assets of foreign creditors.

Those who propose this “take over” seem to feel that the “ISK-isation” of the estates, i.e. regarding all the assets as ISK assets and paying them out in ISK, is an essential move. Writing the assets down via the exchange into foreign currency would then be one possible way of achieving this “take over.”

Although – as far as I can see – creating quite a number of problems, this would however solve two fundamental problems for the coalition government: it would provide the Progressive Party with the ISK300bn, or whatever it will decide is needed for the debt relief – and it will placate those within the Independence Party who think that “estate-windfall” should benefit Icelanders in paying down public debt.

From the numbers above, it is possible to guess at the numbers involved: all the ISK debt is about 1/3 of the estates, ISK950bn, €5.76bn, meaning there would be something like ISK650, €3.94bn, out of this process, a third of Icelandic GDP, to pay down public debt. Given that the Icelandic public debt to GDP is forecasted to be just below 100% of GDP this year, this sum would reduce the debt by a third.

Will the government proceed with these ideas? Time will tell. Relevant ministries and the CBI all have legal opinions at hand, underlining Icelandic law on property right, the importance of keeping all actions within Icelandic law etc. But if the wishful thinking becomes so strong, fuelled by little sympathy for foreign creditors, one never knows. All solutions can be made pretty in an excel document – but to turn them into something that withstands legal challenges and doesn’t just solve the problem like warming one’s toes by peeing in the shoe is quite another matter.

What the creditors could do

Five years from the collapse in Iceland, the capital controls are still in place and the foreign creditors have not yet received any of their assets, apart from the priority creditors to Landsbanki. The priority claimants to Kaupthing and Glitnir have already been paid out, respectively ISK130, €790m and ISK54bn, €330m.

Faced with the possibility that their assets will now be gnawed into by tax, it is seems likely that the estates will take a legal action to challenge the new taxation.

It has taken some years to clarify various legal issues. From the point of view of the foreign creditors, the cash part of the foreign assets – ISK1029bn, €6.24bn, of the ISK1793bn, €10.88bn or 57% – is just waiting there to be paid out.

However, that is not happening as long as the fate of the ISK assets has not been settled. And after a change in the foreign currency law in March 2012, the CBI has to agree to, give exemption to, all payments of the estates.

The bondholders and other creditors may eventually lose patients and sell their claims. In Iceland, much is made of the huge profits made by creditors. That is somewhat misleading. The bondholders have already incurred huge losses though large institutions have no doubt sought shelter behind CDS. Depending on when the buyers in the secondary bought some of them will profit handsomely.

Invariably when creditors lose hope and patience claims get sold and the buyers are those who specialise in difficult assets. These creditors use the courts as much as they can. From small creditors in the Icelandic banks I have heard that there is no lack of suitors from this pack.

It is difficult to avoid the thought that at some point the creditors might lose patience – either as a group or single creditors – and seek legal action against the Icelandic state. That would then most likely start with proceedings where the foreign assets are, to get the assets frozen, after which the creditors would try to prove that they have been waiting needlessly long and nothing is being done to solve the issues.

The Icelandic government has, until earlier this year, not been party to the fate of the estates. With a change in the foreign currency law (nr. 87/1992), the minister of finance and minister of banking have to agree to CBI exemption regarding companies with a larger balance sheet than ISK400bn, €2.42bn, which includes the estates.

This might prove to be a double-edged sword in the sense that the government now risks to be sued because of the estates of the collapsed banks.

The creditors are much vilified in the Icelandic debate, seen as vultures and predators and no politician mentions them without these words. It is ironic that now on the fifth anniversary of the collapse there are again foreigners to blame, thus clouding the fact that the creditors are there as a result of actions taken by a group of ca. thirty Icelanders.

There is much at stake for the creditors, as there is for everyone who stands to gain from the abolition of the capital controls. But those who can gain most from a successful abolition – and consequently stand to lose most from mishaps and delays – are Icelanders themselves. Hopefully, all those involved will recognise this and have the good sense to seek constructive solutions. As an economist said recently: “Capital controls are a slow death.”

*At a closer look, the three estates – of Kaupthing, Landsbanki and Glitnir – are named in the budget proposal (the budget proposal, in Icelandic). As mentioned above, there are other estates of failed financial companies in Iceland but apart from size, the real difference between these other estates and the three big estates is that in the small ones most of the creditors are Icelandic whereas the creditors to the three big ones are 93% foreign entities. – The text seems ambiguous and will most likely be clarified at some later stage.

These are all complicated issues. I hope I haven’t made mistakes, will correct them if found. However, I hope Icelog readers do check the sources if needed.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Deutsche Bank and its (alleged) failure to recognise up to $12bn losses

It’s not a new story – as Deutsche Bank points out in its response – but it’s a story coming up again with more vigor and new evidence. According to the FT: “Deutsche Bank failed to recognise up to $12bn of paper losses during the financial crisis, helping the bank avoid a government bail-out, three former bank employees have alleged in complaints to US regulators.” – FT Alphaville calls it “papering over the cracks … (allegedly)”

Three Deutsche employees have resigned from the bank, after having raised concerns in 2010 and 2011 with the SEC in the US. One has settled handsomely, has been paid $900,000 to settle a case of unfair dismal, apparently after being in touch with the SEC.

It’s worth keeping in mind that Deutche is the highest leveraged bank in Europe and the US: at the end of last year total assets exceeded Tier 1 capital by 44 times – but that’s still down from 68 times in 2007, when the subprime crisis broke. The average leverage in German banks was 32 times last year and in Europe 26 times.

Watching Deutsche from Iceland, it hardly comes as a surprise that some papering was done at and following crisis crunch time in 2008. Deutsche had issued big loans to Icelandic banks and companies. In the case of the pharmaceutical group Actavis, taken off market in 2007 by Bjorgolfur Thor Bjorgolfsson the loan was huge and for some time the biggest loan on Deutsche’s books. Admittedly a loan saga, which belongs to a different age, the year 2007, as pointed out by Breaking View:

Actavis’s 2007 buyout, by Icelandic tycoon Thor Bjorgolfsson, belongs to a different age. Bjorgolfsson was then reckoned among the world’s richest people and the Actavis deal was worth $6.4 billion including debt – five times the value of Iceland’s biggest listed company today. Deutsche employed bubble-era tactics too. The loans totalled a reported 4 billion euros, including 1 billion of “payment-in-kind” notes. These are particularly risky, since instead of paying interest in cash the PIK-note debt burden expands.

This loan backfired for Deutsche – it couldn’t sell the loan on. As Breaking View points out, the loan stayed with Deutsche until it could finally sell Actavis earlier this year.

Deutsche was also a lender into some interesting Kaupthing schemes, where Deutsche advised Kaupthing to lend companies to invest in Kaupthing’s CDS, in order to lower the CDS and consequently the bank’s borrowing cost (it seems to have had some effect). According to Kaupthing documents Deutsche was also a lender, with Kaupthing, when the bank lent money to a Qatari investor to buy shares in Kaupthing. The Office of the Special Prosecutor in Iceland has brought charges against four Icelanders, as earlier reported on Icelog.* Deutsche is not implied in this case.

Deutsche’s lending to Iceland shows quite a bit of recklessness though we can’t see how reckless they were, i.e. in terms of the loan covenants, if they were lending to holding companies (like the Icelandic banks did) and not into companies with operations and more tangible assets. The feeling is that Deutsche in case of some of the Icelandic loans, i.a. the Actavis loans, Deutsche was too late in sensing changed sentiments in the market and couldn’t sell them off. If that was widely happening within the bank Deutsche had some serious issues – and then the speculations now, of the bank having covered its losses, might possibly make sense.