Search Results

Easing capital controls: Non-negotiable terms and national interests

In a heavily staged appearance, prime minister Sigmundur Davíð Gunnlaugsson told Icelanders that ISK850bn, ca 45% of Icelandic GDP would fall into the state coffers, used to reduce the public debt, not for pet projects as earlier announced. With

The size of the problem to solve amounts to ISK1200bn, i.e. this is the sum of ISK, in the estates of the banks and Glacier bonds etc., that cannot be converted to FX and therefore cannot be paid out to creditors right now. What amounts to ISK850bn, or 39% of the assets of the estates at the end of this year will have to be paid off in a stability “contribution” if composition is negotiated and then this amount will be reduced – or tax and bankruptcy if no composition, to fulfil what the government calls “stability conditions.”

Glacier bond-holders and others will either be able to take part in auctions in autumn or buy long-term bonds. All of this is done under the auspice of a phrase repeated over and over again: “National interests takes precedence over interests of private parties.” Here is the English press release, carefully worded and not very clear.

After dealing with this amount, pension funds and ordinary Icelanders will have greater movement. Some quick thoughts on some of the topics du jour:

Size of the problem:

It is clear that the ISK300bn (actually ISK290bn) of the remains of the old overhang (see my last blog before this one on the barest essentials) cannot be paid out in FX – so this amount is clearly a part of the problem. But this is already being dealt with and that action will now continue: the CBI will hold auctions in autumn and those ISK-owners can also buy long-term bonds to come, either in ISK of FX.

That leaves ISK900bn – and this is a more questionable size: ISK500bn (ISK507bn exactly) is the number I have been posting earlier as the size of the problem because these are ISK assets. The remaining ISK400bn are FX assets in Iceland, i.e. assets in Iceland paid off in FX, which I would think was a more debatable size but this is how the government defines the size of the problem.

Stability “conditions” – contributions and tax:

So the problem that needs to be solved amounts to ISK1200 – and by reducing it by 39% the rest can be paid out. Or that seems to be the calculation.

The conditions, i.e. the numbers, are non-negotiable, as was repeated again and again. If the estates negotiate a composition by the end of the year they do not pay a tax but a “contribution”: in fact the same numbers, i.e. 39% or ISK850 but – as far as I understand this will be some reduction so the amount will be ISK500-600bn.

If they do not negotiate a composition the estates go into bankruptcy and pay the full amount: 39%.

This leaves some angles since the ISK850 is well above the ISK500bn but not quite the ISK900bn and well, the ISK300bn is outside of this equation. How these numbers were found I do not know but well, this is how the non-negotiable numbers look like.

The non-mentioned dates

Apart from foreign creditors smarting from controls there are the Icelanders: here, pension funds will be able to invest for ISK10bn a year, more or less what they have asked for, until 2020, unclear from when. And ordinary people will at some non-mentioned date be able to feel liberalisation on certain transactions.

What will creditors do?

Some creditors have already been negotiating with representatives of the government so the plan is indeed not quite out of the blue. According to a Glitnir announcement today, 25% of their creditors agree to this.

Kaupthing’s situation is different, less ISK assets, which might mean that Kaupthing creditors will be less happy to pay. However, no chance to tell until there is an announcement. Everyone might be happy to see an end to this and possible payout in sight.

Either this will all go well, composition beckon and much good will. Or not and the future is legal wrangling in multiple jurisdictions for a decade, like in Argentina. Today, the Icelandic government has taken the country on a journey along a very narrow road above a precipice. If all goes well, everyone reaches the final destination on the other side and there will be much rejoice.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Capital control measures leaked – and soon announced

The Icelandic government, or some parts of it, keep on its game of leaking key information always to the same journalist. Now it is the first big step towards lifting capital controls. As could be expected, this seems more about political posturing than a convincing solution. The coming measures may however provide creditors with their long awaited break to negotiate. If not, Iceland faces the same as Argentina: years of wrangling with ever more aggressive creditors – as the chief foreign adviser to Iceland should be able to inform the government on, from first hand experience.

In March, the Ministry of Finance published three links to regulation and documents regarding duty of silence of advisers, parliamentarians and civil servants who might be in possession of information related to the lifting of capital controls. This was part of a concerted effort to keep under wraps anything related to the lifting of the capital controls – until that day came when the government announced its plans. Whatever the source, DV’s journalist Hörður Ægisson, who over the last few years has been a diligent receiver of government information, published on Friday the outline of this plan, introduced at a cabinet meeting that day, most likely to be made public at a press conference on Monday. The question is if the Ministry of Finance will now look into this leak, considering the measures it took in March.

The Icelandic media landscape is a sorry sight: independent media is weak, the money is where the special interests are. This will no doubt be made clear yet again in the coming weeks as the details of the capital controls plan-to-come will be discussed and debated.

The estates will now have a few weeks to negotiate a composition agreement. If creditors do not accept the parameters the government has in mind the estates will be put into bankruptcy proceedings. So far, the estates and their creditors have been hoping for a composition, since creditors can then run the estates and resolve it when they deem best contrary to bankruptcy proceedings, which are time-limited. Both proceedings do though have the same aim: to maximize the creditors’ recovery.

The problem at the core of this is the foreign-owned ISK: assets worth ISK320bn in Glitnir, ISK160bn in Kaupthing, which means that the size of the ISK problem is different for the two banks – also making it respectively a different case for the two estates for find a solution. The Icelandic government seems to want to get hold of these ISK assets, remains to be seen how it goes. An expected stability tax of 40% can hardly be on priority claims, because that would then hit the UK claims, not the intention. It is difficult to see that the tax could be put in place sooner than 2017, which means no lifting of controls for Icelandic entities until after that, which means still years of capital controls. However, this is speculation until the plan is published.

Among themselves, the hardliners have been talking about getting creditors with their back to the wall facing a gun, i.e. with no options but to follow the government’s diktat. However, Iceland has a rule of law and creditors have legal options in Iceland and abroad. It remains to be seen, as the Icelandic saying goes, who laughs last.

The worrying thing for Iceland is if protracted legal dispute keeps going for years, hindering the lifting of the capital controls. The government seems to be taking the risk of just kicking the process off, in this way, then seeing where it leads to.

Lee Buchheit, advising the government on these issues as on Icesave earlier, brings with him experience, which hopefully will not be relevant. Cleary Gottlieb, the firm he represents, is adviser to the Argentinian government (not Buchheit though but his colleagues). At a conference in Buenos Aires recently, Buchheit foresaw that Argentina’s dispute with creditors might run for at least a decade. Probably not what Cleary envisaged for its stubborn Argentinian client – and hopefully not what is in spe for Iceland.

It certainly has to be kept in mind that Argentine’s problem is sovereign debt and a mismanaged restructuring whereas Iceland has a balance-of-payment problem vs estates of failed private banks. It would take quite a few wrong steps to put the Icelandic government in the situation where it would be directly in dispute with creditors, as is the Argentinian government. So far, no one has really believed the government could end there.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Panic politics in practice

Going on the fourth day since prime minister Sigmundur Davíð Gunnlaugsson announced stability tax, minister of finance Bjarni Benediktsson has not yet said a word on the announcement. Arriving from two weeks holiday in Florida Monday morning he did not attend the first meeting of Alþingi after the Easter break, nor did Gunnlaugsson. The two ministers are said to have spent the afternoon in meetings with Már Guðmundsson governor of the Central Bank, CBI.

My hunch is that Gunnlaugsson did not discuss his statement with Benediktsson before making the speech. The preparations of the capital controls plan-to-be have been carried out in utmost secrecy, drafts not sent in emails etc. and it certainly was not anticipated that one of the insiders, the prime minister, would then go out and announce it at a time that suited him and his party politics. Hardly a statesman-like behavior to use a party conference to make a prime-ministerial announcement of this kind. But with the prime minister getting some numbers wrong it seems he did not have the best advisers at his side in preparing for the speech.

It is also clear that the Bill Gunnlaugsson announced had not been presented earlier because the government leaders had not been able to come to an agreement on the final version. By saying that a stability tax bringing billions to the state will be presented before the end of this Alþingi Gunnlaugsson has put pressure on Benediktsson. It seems like a retaliation for the pressure Benediktsson tried to put on Gunnlaugsson last year when Benediktsson kept announcing that a liberalisation plan would be presented last year – only a much harder pressure because Gunnlaugsson did not just announce the plan but also what it actually should contain.

Vilhjálmur Bjarnason MP for Independence party said in Morgunblaðið yesterday that a tax on estates was far from international practice, would be contested in court, leading to years of court wrangling during which time the controls could not be lifted. Hörður Ægisson journalist at DV said in an interview with the webzine Eyjan that using the lifting of capital controls to make money for the state ran counter to earlier statements. Anything except dealing with foreign-owned ISK was unacceptable, according to Ægisson.

Gunnlaugsson then went a step further over the weekend when he said, in an interview to Morgunblaðið, that the billions from the stability tax would not be used but set aside, on which he and Benediktsson were in total agreement – another poisoned arrow.

So what is all this about? First of all, the stability tax is nothing like the previously discussed exit tax. An exit tax taxes capital movements. The stability tax is indeed a form of asset tax, i.e. will be levied on assets according to certain criteria. One theory is that it will be levied on assets in order to prepare for or at the time of composition of the banks’ estate. And it is to be a double digit tax.

That the advisory committee has been split on how to proceed on the tax, i.a. how to use the billions, echoes in Gunnlaugsson’s words. Of course, parking the billions goes counter to what Gunnlaugsson has been announcing. For Gunnlaugsson to claim that the two agreed on this seems like an attempt to making peace with Benediktsson after his major faux-pas in his speech.

Benediktsson was unavailable for comments yesterday. Gunnlaugsson did not want to be interviewed on Rúv. What happens now is anybody’s guess – some say this is the end of the government but as I have pointed out earlier Benediktsson is in a difficult situation. Should he swallow this or try to act? In theory, he could turn to the opposition and see if he can find some common ground there to form a new government. That would though crave a heroic force and spirit, non of which Benediktsson has shown so far. In addition, the opposition parties have been fairly lame, difficult to gauge there the energy needed for some political fireworks.

According to a Sunday Times article by Philip Aldrick there are some meetings going on between government representatives and creditors. I have not been able to ascertain that this is indeed the case but I believe that yes, there have been some meetings, even as late as last week. The winding-up boards do not seem to be involved and only a few large creditors. It may well be that there are some parties involved trying to map some common ground where negotiations could start from. So far, the government’s official line has been not to negotiate although that seems the most sensible approach for a speedy and efficient end to the misery of capital controls. Remains to be seen.

And it also remains to be seen what comes out of Gunnlaugsson’s statement and how the government will proceed. Benediktsson has been badly treated by Gunnlaugsson who, though most likely not seeing any fault with his behaviour, has not only breached the trust of his coalition party but also ventured into Benediktsson’s territory, quite apart from the substance, i.e. that the Bill had not been presented yet because there was, as yet, no final agreement on the coming plan.

Why Gunnlaugsson chose to make his announcement? Well, this was panic politics in practice: he was standing in front of a party he led to almost 25% of votes, but now standing at ca. 10% in the polls.

– – –

Gunnlaugsson speech is now available online, in Icelandic. I.a. he claims the numbers at stake for creditors in Iceland are high in international context as can be seen from Hollywood films, where $10m are a high number. An interesting insight into an apparently quite parochial mind who likes Hollywood films.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Gunnlaugsson goes solo on the abolition plan: beginning of an action plan or end of coalition?

In an “overview speech” at his party’s annual conference prime minister Sigmundur Davíð Gunnlaugsson announced today an outline of an abolition plan, short on content – only stability tax mentioned – but long on scaremongering of creditors and their wealth amassed in Iceland, with strikingly wrong numbers. From earlier statements by Bjarni Benediktsson minister of finance, whose remit the capital controls are, it is difficult to imagine he condones Gunnlaugsson’s views. Apart from whether this is a good plan or not it is worrying that the prime minister has lately been quite “statement-happy,” expressing views, which neither Benediktsson nor others have heard of until reported on in the media.

Before the Parliament’s summer recess the government will present a Bill to lift capital controls. This is what prime minister Sigmundur Davíð Gunnlaugsson leader of the Progressive party announced at the party’s annual conference Friday.

The only concrete measure Gunnlaugsson announced is “stability tax” that according to the prime minister will bring billions of Icelandic króna to the state coffers. As earlier, Gunnlaugsson emphasised the financial gain and the need to remove the new bank’s ownership from creditors. Worryingly, Gunnlaugsson presented wrong numbers and statements, which do not quite seem to make sense or at least rest on some fairly particular interpretation of reality.

From earlier statements by minister of finance Bjarni Benediktsson on capital controls it is difficult to see how Gunnlaugsson’s statements fit Benediktsson’s prerequisites of an orderly process based on classic measures, as outlined in Benediktsson’s last status report on the controls (see my take on it here). In addition, Gunnlaugsson has now taken the initiative from Benediktsson. The question is if he did at all discuss his speech with Benediktsson beforehand – allegedly, the two do not spend much time and effort communicating.

This in addition to some recent statements from Gunnlaugsson, which have not been discussed with Benediktsson or in the government. Also, there is the report by his fellow party member Frosti Sigurjónsson on monetary systems, another solo initiative by the prime minister.

With Gunnlaugsson’s latest statement there have been some speculation if Benediktsson and his party feel to stay in this coalition much longer. However, it might prove tricky for the party to leave without making it look as if they are somehow caving into creditors whereas Gunnlaugsson is gallantly fighting them.

Icelanders are slowly learning that whenever the prime minister speaks they glimpse the world according to his “Weltanschuung” – and it does not always seem to rhyme with reality.

Wrong numbers, remarkable calculations

In his speech Gunnlaugsson said, according to Icelandic media (I have so far not found a link to the speech), that most of the creditors were hedge funds that having bought the claims in a fire sale had profited quite enormously. The claims in the collapsed banks are so high, he said, that it is difficult to imagine it – as much as ISK2500bn (which being ca 1 ½ Icelandic GDP is not that hard to imagine). “Were this sum invested it would be possible to hold Olympic games, just for the interests, every four years, for eternity.”

This is wrong. The claims themselves are around ISK7000bn, the assets of the three estates are at ISK2250bn. As to the interests of this sum possibly being a sort eternity machine to finance the Olympics this hardly adds up. If we postulate that half of the assets are in cash at 1% interest rates and other assets carry 5% interest rates the annual interest rates would amount to ISK67.5bn or ISK270bn, just under $2bn, over four years. Would that be enough to finance the Olympics? The cost of the London games amounted to $14.6bn, ISK2000bn, the cost of Sochi $51bn, ISK7000bn.

This is worryingly wrong and far beyond reality. The fact that the prime minister does not know the correct numbers is bad but almost worse that he does not have advisers to enlighten him and find the correct numbers for him. Whoever tried to impress him with the Olympics parallel if clearly not fit to be an adviser on financial matters.

Tellingly, all these numbers and the Olympics calculations were diligently reported on Morgunblaðið’s front page today.

The spying conniving creditors

With all these assets (albeit a wrong number) Gunnlaugsson concluded that creditors would be prepared to go to some length to protect their assets. Who wouldn’t? he asked, considering the sums.

“It is known that most if not all larger legal firms in Iceland have worked on behalf of these parties or their representatives. It would be hard to find a PR firm, operating in Iceland that has not worked for these same parties in addition to a large number of advisers in various fields. This activity is almost frightening and it is impossible to tell how far they reach but according to recent news creditors have bought services to protect their interests in this country for ISK18bn in recent years.”

Again, there is no reference to where this number comes from but it seems farfetched, to say the very least. Further, Gunnlaugsson stated:

“We know that representatives of creditors have gathered personal information on politicians, journalists and others who have expressed views on these issues or are likely to do so. And in some cases people have been psychoanalysed in order to better understand how best to deal with them. Secret reports are written regularly in this country for creditors, which inform on how things are going in Iceland, on the politics, public debate, the financial system and so on. In one of the first reports it was stated that the greatest threats to the hedge funds reaching their goals, the main obstacle for them to do as they pleased, was called the Progressive party.”

Exactly what creditors have done to collect information in Iceland I don’t know but what the prime minister describes here is normal proceedings for doing business in a country (though the psychoanalysis might be rare though by far not unknown): they want to follow what is going on, how it affects their interests and so on. The alarmist tone is somewhat misplaced – creditors would not be pursuing their interests well if they did not keep a close eye on Iceland. It does not matter if it is Argentina, Greece of Iceland: firms want to understand the environment they operate in.

“One has to give it to these guys (creditors): they get the main facts right,” said Gunnlaugsson. – Getting the facts right is something less accurate people might try to learn from creditors.

The government’s turnaround in lifting capital controls

According to Gunnlaugsson it was a narrow escape that there were not major mistakes made in 2012 with regard to creditors. He especially thanked “our Sigurður Hannesson,” the MP banker who heads one of the party’s committees, is also on the capital controls’ advisory committee and known to be a close friend of Gunnlaugsson. – Gunnlaugsson did not clarify what heroic deeds were won in 2012; could be the decision to send the Icesave case to the EFTA Court or change in the currency controls legislation, which placed the foreign assets under the controls.

Gunnlaugsson stated that after the present government came to power there had been a real turnaround with regard to the capital controls and all earlier plans had been revised. – This work may ongoing but the only official plan in place is the plan presented by the Central Bank of Iceland, CBI, in 2011.

According to Gunnlaugsson, creditors worked diligently for having Iceland joining the European Union, EU, which would have forced Iceland to follow the bailout path of the euro-crisis countries. This would have forced Iceland to “pay all creditors in full and the whole overhang, not only at full price but at the overprice inherent in the creditors’ paper profit being financed by the Icelandic public through loans. This would have left Icelanders with the debt and no mercy shown. For this government this was always out of the question.”

I am somewhat at loss to understand the remarks about overprice etc. so I leave it to the reader to find the logic here. I am also unaware that creditors have been trying to drag Iceland into EU but they prime minister may well know more on this than mere mortals.

When the road towards the EU had been closed, stated Gunnlaugsson, the government told the representatives of the winding-up boards and the hedge funds that it could not wait any longer. Action will be taken in the following weeks and they will bring the state hundreds of billions of króna, he said.

Again, it is difficult to marry this statement with facts. Just recently, the government sent a letter to the EU, apparently intending to break off negotiations. However, the EU says nothing has changed. According to Icelandic officials briefing foreign diplomats in Iceland the letter does not materially change anything. And so on. Linking the recent moves on the EU and the government driving a harder bargain is not obvious, to say the very least.

The need to act

Gunnlaugsson claims the creditors are not putting forth any realistic solution, which now forces the government to act on lifting capital controls. The plan is to do it before the Parliament’s summer recess. – No mention here of winding-up boards sending composition drafts to the CBI without getting answers.

As often pointed out on Icelog it is clear that government advisers have for over a year been trying to come up with a plan that could suit the two coalition leaders. Tax is one of the points of disagreement: the prime minister wants to make money on the estates; Benediktsson wants to lift the capital controls according to practice in other countries.

It might be difficult to join Benediktsson’s many statements on orderly lifting to the Progressive’s money making scheme. Politically, the Independence party does not feel it owes much to the other coalition party after Benediktsson masterminded the “correction,” Gunnlaugsson’s great election promise of debt relief.

By the time the deadline for handing in new parliamentary Bills expired end of March the coalition parties had not found a common ground on important issues regarding a plan to lift capital controls. A government can always make use of exemption to get Bills into parliament but now the thorny topics are being discussed – reaching an agreement has so far eluded the government.

With his speech Gunnlaugsson might intend to bring pressure on Benediktsson – as did Benediktsson try to do, albeit unsuccessfully, last year with repeated statements on a plan by the end of the year.

The only measure announced: stability tax

According to Gunnlaugsson, with no realistic plans from creditors there is no other way for the government is now forced to launch a plan to lift credit controls before the Parliament ends. The plan is a special stability tax that will bring hundreds of billions to the state, stated Gunnlaugsson. Exactly how it will be applied is unclear but it seems to replace ideas of an exit tax.

This tax, together with other action will enable the government to lift controls without endangering financial stability. “It is unacceptable,” said Gunnlaugsson, “that the Icelandic economy is held hostage by unchanged conditions and to have ownership of the financial systems as it is now (i.e. that the two new banks, Íslandsbanki and Arion Bank are owned by creditors).” – This fits with Gunnlaugsson’s earlier ambitions of both getting money out of creditors and ownership of the two new banks.

The left government would have made “terrible mistakes” of all this, contrary to the Progressive party, which has been remarkable prescient time and again, said Gunnlaugsson:

“It is indeed remarkable how often we (i.e. Progressive party) experience that when we point out opportunities, warn against threats or urge that something is more closely explored or in a new light it is at first met with derision. Then it is fought but in the end viewed as common sense that should have been obvious to all. The main thing is that we Icelanders do not forget that for us everything is possible.”

“Pinch of butter” policies

During his years in office the prime minister has time and again made unfounded allegations and presented views he has not discussed with the government. In a recent article in Morgunblaðið MP Vilhjálmur Bjarnason pointed out how unfortunate it was when ministers thought aloud. One characteristic of the prime minister’s statements that sometimes he is not heard or seen for weeks for then suddenly to burst on the scene with views on everything.

Gunnlaugsson has accused the CBI of being engaged in politics. And he has accused ministries officials of leaking information, almost on a daily basis, he said. Neither allegations have been clarified or substantiated. He also worried about import of foreign food to Iceland because it could carry with it something that was changing the character of whole nations; he did not name it but seemed to be talking about toxoplasma, which luckily has not had this drastic effect in foreign lands.

Then there are all the “plans” Gunnlaugsson has announced without carrying them out or having sought any anchoring in the government. Just after coming into office he was going to appoint a capital controls “abolition manager.”

Most recently, Gunnlaugsson has announced plans to extend the Parliament house by a building sketched by Iceland’s most famous architect, Guðjón Samúelsson (1887-1950) – a house that only exists in a sketch from 1918, the year Denmark acknowledged Iceland’s sovereignty. Gunnlaugsson made this statement of Facebook April 1; when reported in the media it was widely thought to be April fools’ news.

Around that time, Gunnlaugsson also said he thought it was a good idea to build a new hospital – a long-running plan and matter of great debate in Iceland – by the Rúv building, thereby introducing a wholly new direction for the hospital. No previous discussion with minister of health or Landspítali management.

The Icelandic media has now found a name for these unexpected ideas of Gunnlaugsson: “smjörklípa” or “pinch of butter,” meaning that something is thrown into the debate to divert attention. Around the time Gunnlaugsson aired his most recent views one of his party member ministers had been unable to introduce a new housing policy, planned in four new bills. It will come at a great cost, is uncosted, and apparently the Independence party is wholly against it.

Another “pinch of butter”: new monetary system in Iceland?

Plans to revolutionise the Icelandic monetary system has made news abroad recently but less so in Iceland. The news spring from a new report, written at the behest of the prime minister (as I have already explained in detail in comment to FT Alphaville). In short, this report seems more of a favour to a Progressive party member than a basis for a new and revolutionary monetary system in Iceland.

It is indicative of the lackadaisical attitude to form and firm procedures that this report was written at the behest of the prime minister and not the minister of finance, who indeed has never expressed any interest for this topic and has not commented on the report.

All those who have been hyper-ventilating in excitement at this bold Icelandic experiment now starting should find some other source of excitement: this experiment has no political backing in Iceland. The Progressive party, whose following has collapsed from 25% in the 2013 election to ca. 10% in the polls, has little political credibility and force to further this cause.

Political risk: the major risk in Iceland

I have earlier pointed out that the greatest risk in Iceland is the political risk. It is intriguing that Gunnlaugsson chose to break the secrecy of the capital controls plan at a party conference, where he has to confront a total collapse in voters’ support is intriguing. His rhetoric of fights and battles against the conniving creditors and the party’s and his own earlier prescience is an important element in this respect.

With the two party leaders at loggerheads on major topics like the capital controls it is unavoidable that it will come to a confrontation at some point if the government is to take action. The outcome is far from clear.

There is great unhappiness among many of Benediktsson’s MPs, whom he incidentally has not trusted recently with cabinet seats. The general feeling is that it is the Independence party, which so far has been carrying out the policies of the coalition partner.

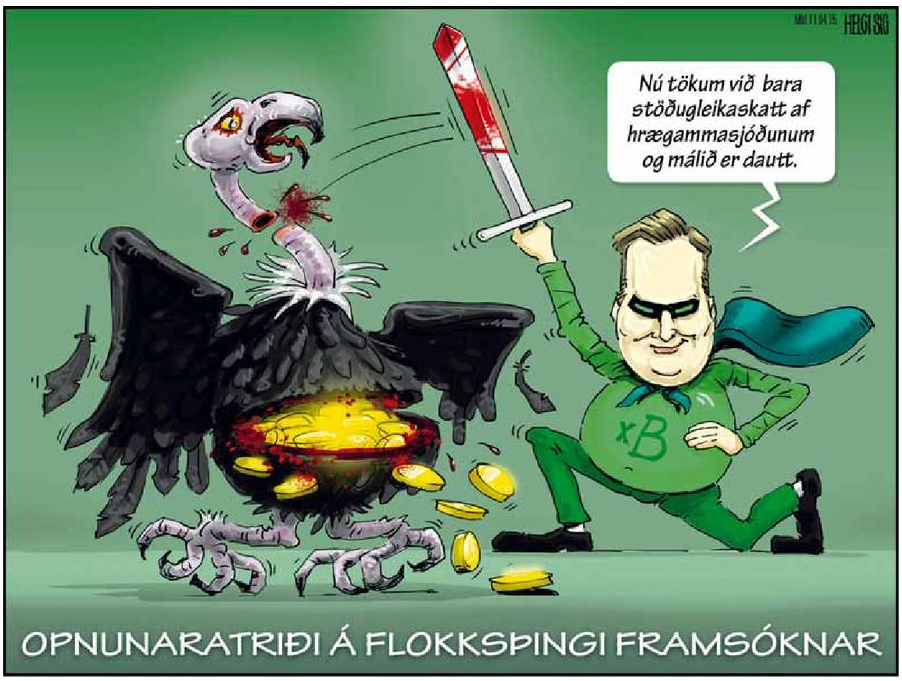

Whatever Benediktsson chooses to do he will need great political skill to steer the party through the coming months. Inaction might not help since creditors may well lose patience and explore their own possibilities, i.a. legal possibilities. If Benediktsson chooses to break away from the Progressive party he will need a clever scheme if he is not to give the coalition party and Gunnlaugsson the role that Morgunblaðið’s cartoonist has given Gunnlaugsson after his speech on Friday:

“Now we just put stability tax on the vulture funds and that will kill the problem”

“Now we just put stability tax on the vulture funds and that will kill the problem”

– – – –

Update: minister of finance Bjarni Benediktsson has not yet made himself available to the Icelandic media on his view regarding stability tax. Some members of the opposition have expressed surprise that there is now talk of stability tax instead of the earlier much discussed exit tax. Guðmundur Steingrímsson leader of Bright Future pointed out both the legal risk and risk to the economy were this plan to be pursued.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Cyprus and Iceland: a tale of two capital controls

Both in Cyprus and Iceland foreign funds flowed into the islands, in the end forcing the government to make use of extreme measures when the tide turned. These measures are normally called ‘capital controls’ which in these two cases hides the fact that the measures used are fundamentally different in all but name. In Iceland, the controls contain the effect of lacking foreign currency, effectively a balance of payment problem – in Cyprus, the controls were a way of defending banks against bank run, i.e. preventing depositors to move funds freely.

It is a sobering thought that two European countries now have capital controls: Iceland and Cyprus; sobering for those who think that in modern times capital controls are only ever used by emerging markets and other immature economies. Cyprus has been a member of the European Union, EU, since 2004 and part of the Eurozone since 2008; since 1994 Iceland has been member of the European Economic Area, EEA, i.e. the inner market of the EU. – The two EEA countries were forced to use measures not much considered in Europe since the Bretton Woods agreement.

Although the concept “capital controls” is generally used for the restrictions in both countries the International Monetary Fund, IMF, is rightly more specific. It talks about “capital controls” in Iceland and “payment restrictions,” i.e. both domestic and external, in Cyprus.

Both countries enjoyed EEA’s four freedoms, i.e. freedom of goods, persons, services and capital. –Article 63 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union prohibits “all restrictions” on the movement of capital between Member States and between Member States and third countries.

Both countries attracted foreign funds but different kind of flows. While the going was good the two islands seemed to be thriving on inflows of foreign funds; in Iceland as a straight shot into the economy, in Cyprus by building a financial industry around the inflows. Yet, in the end the islands’ financial collapse showed that neither country had the infrastructure to oversee and regulate a rapidly expanding financial sector.

It can be argued that in spite of the geography both countries were immature emerging markets suffering from the illusion that they were mature economies just because they were part of the EEA. As a consequence, both countries now have capital controls and clipped wings, i.e. with only three of the EEA’s four fundamental freedoms.

The “international finance centre”-tag and foreign funds

Large inflows of foreign funds are a classic threat to financial stability. At the slightest sign of troubles the tide turns and these funds flow out, as experienced by many Asian countries in the 1980s and the 1990s. Capital controls are the classic tool to resume control over the situation. None of this was supposed to happen in Europe – and yet it did.

Although not on the OECD list of tax havens Cyprus has attracted international funds seeking secrecy by inviting companies with no Cypriot operations to register. After the collapse of the Soviet Union money from Russia and Eastern Europe flowed to the island as well as from the Arab world. Even Icelandic tycoons some of whom grew rich in Russia made use of the offshore universe in Cyprus.

The attraction of Cyprus was political stability, infrastructure, a legal system inherited from its time as a British colony and the fact that English is widely spoken in Cyprus. By the time of the collapse in March 2013 the Cypriot banking sector had expanded to be the equivalent of seven times the island’s GDP. This status did also clearly limit the crisis measures: president Nicos Anastasiades was apparently adamant to shelter the reputation of Cyprus as an international finance centre arguably resulting in a worse deal and greater suffering for the islanders themselves (see my article on the Cyprus collapse and bailout here).

Iceland also tested the offshore regime. Under the influence of a growing and partly privatised financial sector the Icelandic Parliament passed legislation in 1999 allowing for foreign companies with no Icelandic operations to be registered in Iceland. Although it could be argued that Iceland enjoyed much the same conditions as Cyprus, i.e. political stability etc. (minus an English legal system), few companies made use of the new legislation and it was abolished some years later.

But Iceland did attract other foreign funds. Around 2000 a few Icelandic companies started their shopping spree abroad. The owners were also large, in some cases the largest, shareholders of the three main banks – Kaupthing, Landsbanki and Glitnir. The banks’ executives saw great opportunities for the banks to grow in conjunction with the expanding empires of their main shareholders and largest clients. By 2003 the financial sector was entirely privatised, another important step towards the expansion of the financial sector.

In addition, the Icelandic banks had offered high interest accounts abroad from autumn 2006, first in the UK, later in the Netherlands and other European countries, even as late as May 2008. Clearly, Icelandic deposits were not enough to feed the growing banks. They found funding on international markets brimming with money. In 2005 the three banks sought foreign financing to the amount of €14bn, slightly above the Icelandic GDP at the time. In seven years up to the collapse the banks grew 20-fold. In the boom times from 2004 the assets of the three banks expanded from 100% of GDP to 923% at the end of 2007.

The Icelandic crunch: lack of foreign reserve

At the collapse of the Icelandic banks in October 2008 Icelandic króna, ISK, owned by foreigners, mostly through so-called “glacier bonds” and other ISK high interest-rates products amounted to 44% of GDP. These products, popular with investors seeking to make money on high Icelandic interest rates, had been flowing into the country, very much like “hot money” flowing to Asian countries during 1980s and 1990s.

Already in early 2005 foreign analysts spotted funding as the weakness of the Icelandic banks. In. February 2006 Fitch pointed out how dependent on foreign funding the Icelandic banks were. In order to diversify its funding one bank, Landsbanki, turned to British depositors in October 2006 with its later so infamous Icesave accounts. The two other banks followed suit. In addition, the banks were supporting carry trade for international investors making use of high interest rates in Iceland.

Steady stream of bad news from Iceland during much of 2008 caused the króna to depreciate drastically. After the collapse foreigners with funds in Iceland sought to withdraw them. On November 28 2008 the Central Bank of Iceland, CBI, with the blessing of the IMF, put capital controls in place (an overview of events here). IMF’s favourable stance to capital controls was a novelty at the time; not until autumn 2010 did the Fund officially admit that controls could at times solve acute problems as indeed in Iceland.

It was clear that the CBI’s foreign reserves were not large enough to meet the demand for converting ISK into foreign currency. What no one had wanted to face before the collapse was that the CBI could not possibly be a lender of last resort in foreign currency.

The controls were from the beginning on capital, i.e. capital could neither move freely out of the country nor into the country. The controls were not on goods and services, hence companies could buy what they needed and people travel but investment flows were interrupted (further re the controls see here).

The migrating króna problem

The core problem calling for controls was and still is ISK owned by foreigners, i.e. offshore ISK, but the nature of the problem has changed over the years: the original carry trade overhang has dwindled down to 16% of GDP, through CBI auctions where funds seeking to leave were matched with funds seeking to enter. Now, the major problem is foreign-owned ISK assets in the estates of the three banks, i.e. owned by foreign creditors who, without controls, would seek to convert their ISK into foreign currency.*

As outlined in CBI’s latest Financial Stability report, published last September there is a difference between the onshore and the offshore ISK rate: 17% in autumn 2014, about half of what it was a year earlier. These and other factors indicate that the non-resident ISK owners, i.e. those who owned funds in the original overhangs, are most likely patient investors; after all, interest rates in Iceland are higher than in the Eurozone. Although these investors cannot move their funds abroad the interests can be taken out of the country.

The classic problem with capital controls as in Iceland is that the controls – put in place to gain time to solve the problems, which made them necessary – can also with time shelter inaction. With the controls in place the urgency to lift them disappears. Over time, controls invariably create problems as the CBI pointed out in its latest Financial Stability report: The most obvious (cost) is the direct expense involved in enforcing and complying with them. But more onerous are the indirect costs, which can be difficult to measure. The controls affect the decisions made by firms and individuals, including investment decisions. Over time, the controls distort economic activities that adapt to them, ultimately reducing GDP growth.

The main ISK problem is now nesting in the estates of the three collapsed banks where the problem, as spelled out in the CBI’s last Financial Stability report , is that “…settling the estates will have a negative impact on Iceland’s international investment position in the amount of just under 800 b.kr., or about 41% of GDP. This is equivalent to the difference in the value of domestic assets that will revert to foreign creditors, on the one hand, and foreign assets that will revert to domestic creditors, on the other. The impact on the balance of payments is somewhat less, at 510 b.kr., or 26% of GDP.

The balance of payment, BoP, problem could be solved in various ways, i.a. through swaps between Icelandic creditors who are set to get foreign currency assets from the estates, sales of ISK assets for foreign currency and write-down on some of the ISK assets. In addition there are tried and tested remedies such as time-structured exit tax where those who are most keen to leave pay an exit tax, which is then scaled back as the problem shrinks.

The political stalemate

In March 2011, under the Left government in office from early 2009 until spring 2013, the CBI published Capital account liberalisation strategy, still the official strategy. The strategy is first to tackle the offshore króna problem outside the estates, which has been done successfully (judging by the diminishing difference between the on- and offshore ISK rate) through the CBI auctions. That part of the strategy has now come to an end with the last auction held on 10 February.

The next important step towards lifting the controls is finding a solution to the foreign-owned ISK in the bank estates. Their creditors are mostly foreign financial institutions, either the original bondholders or investors who have bought claims on the secondary market.

As indicated above there are solutions – after all, Iceland is not the first country to make use of capital controls while struggling with BoP impasse. However, as long as the political unwillingness, or fear, to engage with creditors prevails nothing much will happen.

When the present Icelandic coalition government of Progressive party (centre; old agrarian party) and the Independence party (C) came to power in spring 2013 it promised rapid abolition of the capital controls. So far, the process has been a protracted one with changing advisers, unclear goals and general procrastination. There has at times been an echo of the belligerent Argentinian tone, blaming foreign creditors for the inertia in solving the underlying problems; importantly, the Progressive party has promised huge public gains from the resolution of the estates, which it seems to struggle to fulfil.

In its concluding statement in December 2014 following the Article IV Consultation IMF points out that the path chosen in lifting the controls “will shape Iceland for years to come. The strategy for lifting the controls should: (i) emphasize stability; (ii) remain comprehensive and conditions-based; (iii) be based on credible analysis; and (iv) give emphasis to a cooperative approach, combined with incentives to participate, to help mitigate risks.” The “cooperative approach” refers to some sort of negotiations with creditors, which the government has so far completely ruled out.

It is important to keep in mind that the estates of the banks, by now the major obstacle in lifting the controls, are estates of failed private companies. The banks were not nationalised and the state has no formal control over the estates. However, as long as the ISK problems of the estates are unsolved the winding-up procedure cannot be finished and consequently there can be no payouts to creditors.

The winding-up procedure will either end with bankruptcy proceedings, which majority of creditors are against, or with composition agreement, which the majority seems to favour. Crucially, the minister of finance has to agree to exemptions needed for composition, which means that the government is indirectly if not directly responsible for the fate of the estates.

The political tension regarding the controls is between those who claim that solving problems necessary to lift the controls is the main objective and those who claim that no, this is not enough: the state needs and should get a cut of the estates.

Finance minister Bjarni Benediktsson has strongly indicated that his objective is to lift the controls whereas prime minister Sigmundur Davíð Gunnlaugsson has allegedly been of the latter view. He has recently been supporting his views by stressing the great harm the banks caused Iceland reasoning that pay-back from the banks would be only fair. This simplified saga of the banking collapse is in conflict with the 2010 report of the Special Investigative Committee, SIC, which spelled out the cause of the collapse as regulatory failure, failure of the CBI and political failure in addition to how the banks were funded and managed.

The government has Icelandic and foreign advisers working on these issues. But as long as the government does not make up its mind on what direction to take nothing moves. Meanwhile Iceland is effectively cut from markets, which makes the financing cost high, in addition to other detrimental effects of the capital controls.

The Cypriot crunch: bank run

The run up to the Cypriot banking collapse in March 2013 was a sorry saga of mismanaged banks, mismanaged country and the stubborn denial of the situation ever since Cyprus lost market access in May 2011. But contrary to Iceland, there has been no investigative report into the collapse, which means that in Cyprus hardly any lessons can be drawn yet from the calamities.

Data from the European Central Bank, ECB, shows that deposits were seeping out: in June 2012 they stood at €81.2bn. In January 2013 they were €72.1bn, down by 2%, in February at €70bn, 2.1% month on month and in March €64.3bn. According to the Anastasiades report (written at the behest of president Anastasiades, leaked to NYTimes and published in November 2014) €3.3bn were taken out of Cypriot banks March 8–15, the week up to the bail-in.

This was an altogether different situation from circumstances in Iceland ensuing from the collapsing banks. Cyprus, part of the Eurozone, was not struggling to convert euros to other currency but it was struggling to convince those holding funds in the Cypriot banks not to withdraw them and move them abroad.

As Iceland, Cyprus was trying to maintain a banking system far larger than the domestic economy could possibly support under adverse circumstances. By the end of 2011 there were 41 banks in Cyprus: only six were Cypriot; 16 were from EU countries and tellingly 19 were non-EU banks. It was clear to regulators that the size was a risk but they maintained that both regulation and supervision was conservative enough to counteract the risk, as bravely stated in a report by the Ministry of Finance on the financial sector in Cyprus. – Ironically, Cyprus had to seek help from the troika just a few months after these assertive words were written.

The controls were put in place with the full acceptance of the troika, i.e. the IMF, the EU Commission and the ECB. “The Enforcement of Restrictive Measures on Transactions in case of Emergency Law of 2013” as the capital controls measures were called by the Cyprus Central Bank, CBC, restricted i.a. daily cash withdrawal to €300 daily, no matter if directly or with a card, or its equivalent in foreign currency, per person in each credit institution. Cheques could not be cashed.

Trade transactions were restricted to €5,000 per day; payments above this sum, up to €200,000 were subject to the approval of a Committee established within the CBC to deal with issues related to the controls. For payments above €200,000 the Committee would take into account the liquidity buffer situation of the credit institution. Salaries could be paid out based on supporting documents. Those travelling abroad could only take the equivalent of €1,000 with them.

The roadmap for abolishing them came in August 2013, again with the full blessing of the troika. There was no time frame, only that the measures would be “in place for as long as it is strictly necessary.” They would be removed gradually and with prudence, always with a view on financial stability. First the restrictive measures on transaction within Cyprus would be abolished and only subsequently could the restrictions on cross-border transactions be lifted.

The controls have since gradually been eased and by May 2014 all domestic restrictions were indeed fully eliminated. On 5 December 2014 i.a. the limit for travel abroad was sat at €6,000, from previous €3,000 and business activity not subject to approval was sat at €2m. With the last change, on 13 February, those travelling abroad can now take €10,000 with them. Transfers of funds abroad were increased from the December limit of €10,000 to €50,000. The island’s pension funds are still subject to capital controls.

As in Iceland, abolishing, for unspecified time, one of the EEA’s freedoms was to be in place only for a short time. Until late 2014 it seemed as if the Cypriot capital controls might be entirely abolished by the end of that year. That did not happen. The last bit remaining is the politically tough one.

The task for Cyprus: overcoming the political hurdles

With the domestic restrictions abolished the IMF Staff report in October 2014 for the Article IV Consultation pointed out that the “external-payment restrictions” in Cyprus have to be relaxed in a gradual and transparent way. “…owing to the short deposit-maturity structure, significant foreign deposits (close to 40 percent of the total), large reliance of BoC (Bank of Cyprus) on ELA (Emergency Liquidity Assistance), and the lack of other market funding, external restrictions remain in place. While restrictions do not apply to fresh foreign inflows into Cyprus, they limit outflows, hampering trade credit and affecting overall confidence.” If the external restrictions remain in place they can damage investors’ confidence and consequently foreign direct investment, FDI.

As in Iceland, the main Cypriot problems stem from political tensions, which “could have adverse implications for confidence and the recovery,” according to the IMF. The key obstacle in Cyprus is lack of progress in addressing non-performing loans, NPL, staggeringly high in Cyprus at 37.9% of total gross loans in 2014. Debt-restructuring framework, including i.a. a foreclosure legislation and insolvency regime is still a lingering political problem. Further, banks need to restructure and build capital buffers, critical to lift the remaining restrictions.

Visiting Cyprus in early December I was told that the work on the NPLs was about to be finished and a new insolvency framework would be in place by the end of the year. It is still not in place, a sign that the politial tensions have not eased. In spite of all that has been done Cypriots have lost trust in their banking system: almost two years after the collapse it is estimated that the islanders keep up to 6% of GDP at home, under their proverbial mattresses or wherever people stash cash.

The political test for Cyprus and Iceland

Both islands face a political challenge lifting capital controls.

In 2012 the CBI published a report on Prudential Rules Following Capital Controls, thus outlining what is needed once the capital controls have been lifted. This is greatly facilitated by the fact outstanding work of the SIC. Consequently, life and prudence after the controls are lifted has been staked out.

Iceland is however struggling to throw off shackles of nepotism, even more so under the present government than for quite a while: personal connections seem to matter more not less than before. Lifting the controls will test the times, if they are new times with accountability, transparency and fairness or the old times of nepotism, opacity and special favours.

Cyprus stands harrowingly high on the Eurobarometer corruption index and it suffers from lack of stringent analysis of what happened, making it difficult to draw any lessons, i.e. on how regulation needs to be improved, failures at the CBC etc. Cyprus authorities have some way to go in order to win trust with the islanders. The fact that no public inquiry has been held into the collapse, no investigation, no report written adds fuel to the already low trust. I have earlier written that Cyprus with high unemployment and contracting economy bitterly needs hope.

Both Cyprus and Iceland will have to show that they understand what happened and how it can be prevented from happening again. The exit from capital controls for both these islands will depend on political decisions, which will shape their next decades.

*I have blogged extensively on Icelog on the capital controls in Iceland. Here is the latest one, on the politics. Here is one from end of last year, on i.a. the various possible solutions. I have at times blogged on Icelog on Cyprus or compared Iceland and Cyprus. Here is a collection of blogs on Cyprus, i.a. two on the topic of Cyprus, Iceland and capital controls. – This post is being cross posted on A Fistful of Euros.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Capital controls and political stalemate

For the time being the topic of capital controls in Iceland seems shrouded in silence. Yes, recently yet another MP banker was added to the controls steering committee, the prime minister mentioned the controls in a speech without maligning creditors or talking about the billions the state could derive from the bank estates. In other words, so far so little, which means that little is changing from what it has been.

“Lifting the capital controls is the single most important issue for Iceland,” prime minister and leader of the Progressive party Sigmundur Davíð Gunnlaugsson said in a speech recently. Gunnlaugsson has mostly just made stray comments on the controls, lately far from his earlier so belligerent tone and no mention of the funds that could be derived from the estates.

The force minister of finance and leader of the Independence party Bjarni Benediktsson seemed to be putting into control-lifting late last year seems to have seeped out of him as he could not deliver on his promise: to present a plan by the end of 2014.

There is now little apparent energy behind this issue. Compared to same time last year the progress is that there are now foreign advisers working on capital controls and a new steering committee, the third such advisory group. In addition to hiring foreign advisers Benediktsson’s major achievement last year was pulling through the Landsbanki bond agreement. But instead of being the agreement being first it has remained the only step so far.

“I fully expect something to happen regarding the capital controls after the next election, in 2017,” was the wry comment from one Icelandic observer some days ago expressing the sentiment that this single most important issue seems to be devoid of all political urgency. The third Thursday in April is the Icelandic first day of summer when parents give their children something seasonal for summer presents such as a ball to play outside. Spring might also be the time when some next step might be taken towards lifting the capital controls.

The young and yet so lethargic power-players

The left government, in power from spring 2009 until spring 2013, surely got some things done such as targeted debt write-down for households, steering Iceland through an IMF program and dragging the country back to growth already by mid-2011. However, it was consumed by infighting and was its own worst enemy. Following this government an energetic government focusing on growth of opportunities and ideas, as well as growing the economy would have been a great asset.

A government led by two young coalition leaders – the youngest ever prime minister and a young minister of finance – seemed indeed very promising. However, in many ways the duo seems be heading towards the past rather than the future. The language of the prime minister’s tends to echo patriotic language harking back to the mid 20th century. New appointments often seem to smell of nepotism and old ties.

The Icelandic media has at times focused on the prime minister’s somewhat erratic behaviour; apparently he often goes on un-announced trips abroad. He has the habit of making remarks that then turn out to be factually wrong or misleading. Words seem to come very easy to the prime minister but all too often the substance is doubtful.

With the prime minister as a comparison Benediktsson strikes a more serious and competent tone and demeanour. His approach is conciliatory and he seems widely liked, except by the old guard in the party who still mourns the, perceived by them, golden age of Davíð Oddsson. It has been apparent time and again that Morgunblaðið, with Oddsson as its editor-in-chief seems to side more with Gunnlaugsson than Benediktsson reflecting that the paper is owned 50-50 by companies with ties to the Independence party and the Progressive party. A powerful person in the latter camp is Þórólfur Gíslason, a relative of Oddsson. (If blood ties matter or not is unsure but most Icelanders will see this as relevant).

The two coalition leaders come from families at the heart of the Icelandic power structure. Benediktsson’s family is the core of the Independence party story of power. His namesake, the brother of his grandfather (if my genealogy does not fail me) was a legendary leader of the party from 1963 to 1970, the party’s glorious age. “It’s not enough just to carry this name,” one Independence voter remarked sardonically. Gunnlaugsson’s political family ties only goe back a generation: his father was briefly an MP and his business interests allegedly rose from political connections.

Political deadlock

Although the government tension is not apparent on the surface the tension shows in the fact that amazingly little seems to get done. The government is i.a. hovering as to breaking up the EU membership negotiation or not. A recent example is a draft proposal for a new Act on fishery management, expected to be introduced to Alþingi before its summer recess; the proposal’s course is now uncertain. Another topic is the Interconnector, i.e. a cable connecting Iceland to the UK: UK has shown interest in buying Icelandic electricity but the government seems unable to act on this interest, i.a. due to deep-running political and interest divergences on this issue.

On the whole, the government is seen as moving slowly, even remarkably slowly, considering that is has a strong majority and no internal opposition, at least not on the surface. It is also blessed with an opposition, which for a long time seemed to be waking up every day from a crushing defeat the previous night. Only recently the leaders of the Left Green and the social democrats have made a bit of a splash in the political debate.

There are no apparent explanations as to why the government is so lethargic. It is not so much words as action that “don’t come easy:” the prime minister is good at making speeches about the promising future of Iceland but moving beyond the words is difficult.

As one source in the Icelandic business community said there are plenty of examples in the world of countries with natural resources and other advantages that still do not manage to harness what they have. “Capturing the possibilities doesn’t happen automatically.” In Iceland, it seems not to be happening at all.

The latest polls show that the government now has support of 36.4% of the voters, compared to 34.1% end of January and 34.8% mid January. The top line figures are Independence party 25.5%, compared to 24.9% earlier and the Progressive party 13.1%, compared to 12.7%. Hovering around 25% is the Independence party’s destiny now, far from the around and above 40% at the time of Benediktsson’s namesake in power, last seen in the elections in 1999, 40.7%, under Oddsson’s leadership. – The fractioned opposition, four parties, are not moving the voters much.

Yet another committee

Following the meeting between the Winding-up boards and their advisers with the government’s advisers in December the feeling was one of cautious optimism among creditors. At the time, Benediktsson had for months boldly been announcing “a plan” by the end of the year.

Unofficial announcements following the meeting were that everything should be in place to proceed early in the New Year. In his end-of-year interviews and statements the prime minister, in his freewheeling mode, drummed up the optimism by first talking about “a plan” soon, then by the end of January. This has to be seen in context with statements after coming to power in summer of 2013 as to how easy and quick the lifting of the controls would and could be.

The only thing that January brought was a new committee. As earlier, Glenn Kim is the chairman. Others are Benedikt Gíslason, adviser to Benediktsson, and Eiríkur Svavarsson, by now veterans in this field, together with Sigurður Hannesson from MP Bank, a close friend of Gunnlaugsson and two from the CBI, Ingibjörg Guðbjartsdóttir and Jón Sigurgeirsson.

Gíslason used to work at MP Bank and now just recently MP bank’s chief legal officer, Ásgeir Helgi Reykfjörð Gylfason (this long names are uncommon in Iceland) has been added to the committee.* The CEO of MP Bank is Gunnlaugsson’s brother-in-law but as the bank stated in its press release on Gylfason it is proud that the bank’s expert are sought to work on such important issues.

Svavarsson, Hannesson and Gylfason are seen as close to the prime minister. Sigurgeirsson is close to the governor of the CBI, who shares a good understanding with Benediktsson. Apart from speculations of intimacy and allegiance, it is worrying that none of the Icelandic lawyers on the committee has any international experience.

This is the third group set up to work on the capital controls. The feeling is that previous groups have broken apart because of differences of opinion on how to approach the resolution of the three bank estates, a necessary step towards lifting the controls.

What could come next, apart from more procrastination?

Glitnir has made news in Iceland following a leak that Íslandsbanki might be sold to Middle Eastern investors. Earlier, Chinese interest had been in the air. Certainly, selling Arion, owned by Kaupthing, and Íslandsbanki would make a composition easier.

The estates have had plenty of time to calculate a positive outcome. Although no decision was announced for a next meeting after the December meeting it is expected that another meeting will or would follow soon.

Some weeks ago Víglundur Þorsteinsson, an old businessman who lost his company into bankruptcy following the banking collapse, made allegation about wrongdoing regarding the splitting up of the banks, i.a. that creditors had profited unduly. This was not the first time he stated these claims and he has never found any serious support for them. This time the prime minister sided with him, saying this should be investigated.

Brynjar Níelsson, an Independence party MP, got the task of reviewing the claims, which he did by utterly rubbishing them. It is not clear if the prime minister will see this case as a reason to move slowly regarding the estates, probably not, but his support to Þorsteinsson was much noted.

As far as is known the new group is working on proposals towards lifting the controls. The two coalition leaders have often spoken about a “holistic solution,” a “framework” etc. Considering the fact that the two estates ripe for composition, Kaupthing and Glitnir, have very different problems – Kaupthing with no ISK assets beyond its ownership of Arion but Glitnir with ca. ISK100bn in addition to Íslandsbanki – the framework might turn out to be of a general nature so as to accommodate tailored solutions for the estates.

The much discussed exit tax might be pressed for, in order to get the funds the prime minister seems to think can be had from the estates. However, as I have pointed out earlier exit tax does not solve the ISK problem, unless used in a targeted way, as did Malaysia in the late 1990s. Possible solutions have been dealt with in earlier blogs.

The business community is up in arms about the stalemate on controls but the voters do not really sense the effect of the controls, meaning there is only a moderate pressure on the government to act. As pointed out earlier it seems that the two coalition leaders do not proceed on the controls because they really are at loggerheads on how to go about it. There really is no longer anything unknown in this issue. It has all been mulled over, no stone is unturned. What is lacking are decisions, not more analysis etc.

At the core of that dispute is really if lifting the controls is a gain in itself or if Benediktsson is willing to help Gunnlaugsson find a way to lift the controls in such a way that he, the prime minister, can proclaim victory.

*As reported earlier, the appointment of Sigurður Hannesson was first announced by MP Bank, not confirmed by the government until days later. Now the saga is being repeating by appointment of Gylfason: the bank announced his secondment on February 13 but no official announcement has yet been made by the Ministry of Finance. Another indication of the lackadaisical attitude for formalities.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

A revealing leak in Morgunblaðið

A journalist at Morgunblaðið, Hörður Ægisson, has a remarkable access to mole/moles within the CBI and/or the civil service who provide him most lavishly with one leak after the other. Ægisson has earlier touched upon Project Slack, apparently the code name for the plan being hatched on the capital controls. Today, he not only mentions the plan by name but seems to copy and paste parts of it: interesting information on exit tax etc. with most interesting ramifications. The leak might be good news for creditors as it gives them the time to figure out a line of defense. But whether it will be used is another matter: it does not seem in line with the minister of finance vision of a simple route steering well away from legal risks.

One of the key concepts mentioned again and again to justify exit tax – i.e. the omnibus one on the whole of Iceland – is equality: exit tax should be equal for everyone, both foreign creditors and Icelandic businesses. This never sounded plausible; after all, those who want the state to make money out of lifting the controls aim at getting that money from the estates and foreign creditors, not from just everyone in Iceland. The leak in Morgunblaðið clarifies this strife for “equality.”

Morgunblaðið writes (p. 16 of print copy; my translation; emphasis in bold and additions in brackets are mine):

In other words, the (exit) tax is a declaration on behalf of Icelandic authorities that cross-border payments, for example due to possible exemptions for the estates (of the failed banks) accompanying a composition agreement, would be treated as is the case with other Icelandic entities. There would be no difference if the payment was in ISK or foreign currency. … Further, the aim is to find ways for domestic entities, both pension funds and businesses, to bring funds out of the country without having to pay the exit tax planned to be introduced as part of the plan of lifting capital controls.

So much for the declared intention of equality. This is a plan where there are foreign creditors on one hand, domestic entities on the other and some are more equal than others. I.e. first there is a general rule for everyone and then exemptions for some, who all happen to be Icelandic.

This does of course not come as any surprise. It has long been clear that a) the Progressive Party wants to channel funds, not only ISK but also FX, from the estates to the Treasury; b) if this channeling were an easy path to follow it would have been done as soon as the government came to power. – The path towards the funds has to be done under the sign of equality but in order for these measures only to hit the foreign creditors some special paths are needed. It is never easy to formulate “equality” that effectively is discriminatory; which explains why it is taking so long. And even more difficult since Bjarni Benediktsson minister of finance defined the route he wants to take: simple and avoiding legal risks.

Further, Morgunblaðið writes: “The estates’ foreign assets will not be treated separately, as creditors had planned, since they only own claims in ISK in Icelandic estates.”

It remains to be seen if this somewhat narrow definition matters or not. Following a Supreme Court ruling on November 10 (an unofficial English translation here) creditors can now ask for a payout in FX, even to the degree that the estates are free to buy FX to provide for a payout.

As to levying the exit tax (or “exit levy” – Morgunblaðið uses the term “levy,” as in the 2011 capital control plan, not “tax” as has been used lately) Morgunblaðið writes: “The exit levy will however cover offshore ISK owned by foreign entities (which is odd to mention because the definition of offshore ISK is “foreign-owned ISK” – does this indicate that there is no levy on offshore ISK owned by Icelandic entities through foreign bank accounts? Or is this just a manner of writing?) after they have been forced to convert their ISK, with a haircut, into FX bonds with maturity of more than 30 years. According to Morgunblaðið’s sources the proposal is to issue these bonds with fixed interest rates below 3%. It is likely that the sovereign would have to pay close to 50% higher interest rates by issuing comparable bonds in international markets.”

Here it is of interest to note that these (foreign) offshore ISK owners would be subjected to haircut twice: first when they would be forced (how? By law?) to convert their ISK into FX bonds – and then when they take the bonds abroad.

Interestingly, long maturity is normally imposed to keep funds inside a country, i.e. to prevent it from leaving, when capital controls are lifted. This double-fencing in does, at first sight, not quite seem to add up.

Also, this only seems to fit offshore ISK holders in the original overhang, not the foreign-owned ISK in the estates but that might be my misunderstanding.

The worrying, or out-right scary, news for Icelanders is however that this plan seems built on the belief that with this plan Icelandic sovereign bonds will stay near to a junk/below-investment-grade level if the authors of this mighty plan calculate that 3% is a way for Iceland to get cheap interest rates. That is definitely bad news for Iceland and for Icelandic businesses, which to a great degree are dependent on the sovereign rating. After all, lifting the controls is meant to provide market access for Iceland and Icelandic businesses, not to keep them stuck under a new name in capital-control environment for another 30 years.

As Bjarni Benediktsson put it so well in a speech in October foreign investors tend to mistrust countries that need capital controls to survive.

The original overhang offshore ISK owners (now amounting to ISK307bn; 16% of GDP) are in for some changes if Morgunblaðið is in possession of the real plan: “Investment provisions of offshore ISK owners, who now hold ISK130bn in deposits and ISK170bn in sovereign bonds, will be tightened so they will have a choice either to participate in such a sovereign bond exchange or hold their ISK on non-interest bearing accounts in the CBI without any investment provisions. Offshore ISK owners who have invested in sovereign bonds will be forced into a bond exchange when their bonds mature. Foreign entities own ca. ISK80bn in state securities maturing in 2015 and 2016. The (exchange) bond, issued by the sovereign, is tradable but if investors wish to sell their bonds they will have to pay a 35% exit levy.”

It would be most interesting to know if Project Slack has already been blessed and signed by the foreign advisers or if this is “home-knitted,” to use an Icelandic idiom, i.e. if it is put together by Icelandic experts fulfilling the wish of the powers that are. My understanding is that the foreign advisers are indeed familiar with this project. The leak might hone their understanding of the political territory they are operating in.

In an interview with Viðskiptablaðið CBI governor Már Guðmundsson throws some cold water on speculation regarding an exit tax. In a most becoming governor-like Delphic utterance he points out that such a tax was already part of the 2011 plan but it is untimely to speculate what role it might play or how high it might be used. – Keeping in mind the original 2011 exit tax, targeted at foreign-owned ISK against the all-encompassing exit tax now discussed it is indeed appropriate to mention its role and eventual usage as something that needs to be pondered on.

Whoever named the project must be complemented for his (must be a “he” – no women working on this project) sense of irony given the myriad of connotations it can have: the slack legal framework, the slow-moving project etc.

Perhaps creditors know all of this already and have themselves acquired copies of Project Slack, just like Morgunblaðið. But if not, Morgunblaðið has done the creditors a huge big favour providing their lawyers with stuff with which to prepare for the eventualities listed above. Unless of course the slack project in the end neither fits the CBI, IMF, EU and Benediktsson’s sense of practicality and enforceability, not to mention irony.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Lifting the capital controls: attacking the central ISK problem or dallying around it

The depressing thing is that resolving the capital controls in Iceland might not be that tricky: there are some really sound ideas on lifting the capital controls and there is no lack of literature/IMF papers on similar situations in other countries. The problem is a political one: politicians have on one hand promised too much, on the other fear the responsibility of fateful decisions. Dallying around has already caused a costly delay for Iceland. But two significant steps have been taken recently: the Landsbankinn bonds agreement is finally in place and the Central Bank has announced its final foreign currency auction on February 10.

Finally, creditors – or rather the Winding-up Boards of the three failed banks and some of their advisers – got to meet the government’s so-called advisory group. An IMF-group, in Iceland now, was not at the meeting according to sources but had meetings with i.a. representatives of the creditors following the meeting yesterday. This is a meeting that will sprout many meetings but nothing more concrete for the time being.

The meeting was called for by the foreign advisers to hear the view of Winding-up Boards and creditors. With no plan presented it seems a bit of an exercise in trying to be seen doing something but as Lee Buchheit said to Rúv last night the foreign advisers thought it was time to hear from the Winding-up Boards before presenting their proposals. – And when could a plan be expected? Early next year, according to Buchheit. In the light of the past that seems an optimistic bid.

With the Landsbankinn bonds agreement in place Benediktsson has shown long-awaited determination though the press release curiously has six statements about what is not being done. Further, it is of great interest to see that the CBI auctions are now being brought to an end with a final auction on February 10. It is reasonable to think it will then take a couple of months to finalise plans, which means that in early spring some plan for dealing with the estates and easing capital controls might reasonably be expected; perhaps in the Icelandic tradition of giving summer presents on the first day of summer, celebrated annually on the third day of April.

However, an exercise in cleverness that does not resolve quickly and effectively the ISK assets, the core of the capital controls, will not be a happy solution for Iceland: most Icelandic business leaders agree that Iceland needs a speedy lifting of the capital controls, of course always with an eye on financial stability.

No conclusion – it wasn’t that kind of a meeting