From the pots and pan revolution to the Panama Papers and other scandals

The outcome of the election provides no clear option in forming a government but it is clear that Icelandic politics is changing: the Independence Party, earlier the backbone of Icelandic politics, has lost its strong position which it partly held because the Left kept splitting but on the Right the Independence Party was the only option. That is no longer the case. The many small parties now seem a fixture on the political scene in Iceland. Contrary to many other countries, nationalism and xenophobia do not colour Icelandic politics though these leanings can be detected. The narrative is unclear: the country of the pot and pan revolution votes in offshore company owners.

The opposition – especially the Social Democratic Alliance – won the election with the government losing twelve seats but it’s not a victory that they can make much use of. The favour of Icelandic voters is now split between eight parties in Alþingi but the political interest is huge with voter participation at 81.2%, up by just over one percentage point from 2016.

There have not been fewer women in Alþingi for a decade, so much for the land of gender equality – two of the new parties, the People’s Party and the Centre Party as utterly male-dominated. The Left victory, indicated by polls, did not materialise. The liberal global current that brought the Pirates, Revival (Viðreisn) and Bright Future 21 seats in 2016 has evaporated; these parties now hold ten seats and Bright Future did not get a single MP.

Forming a government will be tricky, even more so if this government is to last for more than a year or two.

Independence Party: the centre of power that was

The GOP of Icelandic politics is still old but no longer the grand centre of power. Gone are the elections when the party could count on the support of 30 to 40% of voters. In the party’s 2009 wipe-out it lost nine MPs, fell from 36.6% of the votes to 23.70% and 16 seats. It rose to 29%, 21 seats, last year but is now back at 16 seats and 25.2%. If it continues to attract only older voters, as is now the case, the party has a lot to worry about: it will, literally, die out.

The party’s position over the decades was strong: the Left kept shifting like a kaleidoscope the Independence Party ruled undivided and alone, except for very brief interludes. With Bright Future and in particular Revival, the latter is now lead by an ex-Indpenedence Party minister, those on the Right had and have other options.

Bjarni Benediktsson, though young and energetic, has not been able to shift or strengthen the party. He is however an undisputed leader, there are no obvious candidates in sight. Panama Papers companies, his IceHot1 registration on an affair website and his family’s connection to dubious deals and a pedophile have not undermined him. Rumblings in the party are just that, rumblings; unity on the surface.

The politcal centre

Bright Future did not particularly like to place itself on the Left Right axis but it was largely seen as a liberal party, palatable to those on the political Right. It was pro-EU, as is Revival. Bright Future instigated the fall of the government but did not reap any benefits from that. In government it did not manage to make its mark. Bright Future leader Óttarr Proppé did not have a strong enough message though his sartorial style of three piece corduroy and turtlenecks certainly stood out.

The Progressive Party did the remarkable feat of not losing ground, kept its 8 seats, though its former leader Sigmundur Davíð Gunnlaugsson left the party and raked in 10.8% of votes, probably a bit from everyone but most from the Independence Party. Progressive leader Sigurður Ingi Jóhannsson is of the pure Progressive mold, level-headed and portly, ready to work with both the Left and the Right and now wooed from both sides.

The Pirates, the voters’ darling last year, did lose four MPs, now have six. In spite of measured policies and no reasoned promises they did not cut a striking figure on the political scene.

The new political forces: male-oriented populists with a touch of xenophobia

The most remarkable political entry is that of Inga Sæland who rose to fame on the Icelandic X Factor. Sæland is a divorced mother of four and has done this and that. Counting herself as one of them her motivation is to improve the life of poor people in Iceland. Her party, the People’s Party, running for the first seemed to be destined for not making it into Alþingi. At the leaders’ debate two days before the election Sæland, asked what she wanted to achieve in politics, burst into tears, she was so passionate for her causes.

Whether it was the tears or her politics, Sæland secured 6.8% of the votes and four seats. For a party lead by a single mother – many of them in Iceland – it’s rather remarkable that she is the only woman MP of her party’s four MP.

To begin with Sæland struck a tone of xenophobia but only at the very beginning. Later she emphasised the need to live with an influx of foreigners, utterly denied any racist leanings and made no such references. Instead, her message was populist promises of better life for the poorer part of society.

Sigmundur Davíð Gunnlaugsson showed that 10.8% of Icelandic voters do not care about his lying about his offshore company. His voters seem more taken up with his promises of giving Icelanders shares in Arion bank where the government only owns 13% but has options to buy more. Gunnlaugsson’s other policies were less striking but continued his earlier message of subsidised agriculture and anti-EU tones. He has earlier flirted with nationalism and xenophobia and the same could be heard this time.

Less liberal voices, fewer women

Compared to other European countries where nationalism and xenophobia have been on the rise, the same is not the case in Icelandic politics. These tendencies can be detected close-up but the parties that have flirted with them, the Centre Party and the People’s Party have not particularly gained from it.

This is all the more remarkable because the influx of foreigners in Iceland has been very large since 2000: foreign inhabitants have gone from 2.6% in 2000 to 8.9% now. The largest nationality is Polish who have integrated well. In general, foreigners come to Iceland to get work, more than plenty of work to be had.

However, given the leanings of the two new parties, it can be argued that outward looking liberalism and globalisation is now weaker in Iceland than earlier. Due to the electoral system, the densely populated area around Reykjavík has less weight than the countryside.

The People’s Party and the Centre Party have an aura of anachronism in the sense that women are largely absent, except for the People’s Party leader. Otherwise, the appearance is portly elderly males. In total, these two parties hold eleven seats with only two of them filled by women.

In its world view the Centre Party also has an aura of anachronism: its leader has been prone to look back in search for political references rather than the future when his old party was strong because agriculture was a strong sector. Gunnlaugsson is interested in city planning: during his time as PM he even gave the Reykjavík city council drawings – not much more advanced than a kid’s drawings – of houses he thought should be built in the city centre in stead of more modern buildings already planned. If the drawings hadn’t come from the PM Office most people would have considered this a rather embarrassing and amateurish attempt to have a say.

The political narrative in Iceland: rambling and flip-flopping

Iceland very much debuted on the international scene as the first crisis-hit country in October 2008. The pots and pan revolution, which drove out an Independence Party-led government with the Social Democrats and also drove out a former Independent leader then governor of the Central Bank Davíð Oddsson, gave Iceland the image of a feisty young nation. The Office of a Special Prosecutor, which investigated and prosecuted people related to the banks, further supported that image.

However, it’s difficult to square that image with the fact that the Independence Party is still the largest party and the ousted Panama Papers ex-PM Gunnlaugsson secured almost 11% of the votes on Saturday. Icelanders may have flared up in the winter of 2008 and 2009 but they have partly turned to the conservatives, although riddled with scandals. And to Gunnlaugsson’s party, centred not only the political centre like the Progressives, his old party, but around Gunnlaugsson himself – after all, the Independence Party and the Centre Party together hold 36.1% of the votes.

Yet, the pots and pan spirit hasn’t quite disappeared – the Pirates are still in Alþingi and the Left is emboldened – but there certainly is no clear narrative of a country that doesn’t tolerate financial scandals, old family dynasties and their special interests. Flip-flopping and looking at persons rather than principles and ideals is still the Icelandic way to political choices.

Options for forming a government

With the Left Green touching 30% in opinion polls up to the election the Left clearly felt its time had now come. That’s less clear now though the Social Democrats have made a spectacular comeback, doubled their last year outcome. Its leader Logi Einarsson did not seem to have much going for him but rose and shone in the campaign, proved to be relaxed and passionate. He himself claims he has not been media trained and so, has preserved spontaneity and the human touch.

Forming a government is about making a team working towards the same goals. Bjarni Benediktsson did not achieve that with his government. He might have another go, will try to woo the Left Green. However, the opinion forming is that the government has lost, the opposition won.

Jakobsdóttir is adamant that a Left government could and is in the making but more time is needed. For her, it’s crucial that she will succeed, will be able to harness the momentum though she has already lost some of it. Otherwise, she could be destined to become the leader of great promise but ultimately unable to deliver power to her party, unable to show in a tangible way that she can be more than just a popular person.

When pundits were musing on the outcome before the election no one seemed to give it a serious thought that Gunnlaugsson could return to government. His gain came as a surprise but although no one is saying it aloud, it is highly unlikely he will be invited to join any government. He has a reputation for being unreliable also in the literal sense: as a PM he was often away, no one knew where, he rarely showed up in Alþingi for debates and as an MP he has stayed away though without calling in his substitute; most likely that will continue.

Contrary to the anchor of stability as the Independence Party likes to portray itself the party has been in the last three governments that sat for less than a mandate term. The Left government in power from 2009 to 2013 is the only government after the 2008 collapse that sat a whole term, or rather stumbled through it, more dead than alive due to enormous infighting in the two coalition parties Left Green and the Social Democrats who led the government.

Iceland is booming as growth figures around 7% of GDP show. Certainly an enviable situation, seen from the perspective of 0 to max 2% GDP growth in so many other European countries. But doing the “right thing” hasn’t necessarily benefited those in government since 2008 (see my pre-election blog) – and navigating the good times has never been easy in tiny Iceland. As we say in Icelandic: það þarf sterk bein til að þola góða daga, it takes strong bones to stand the good days – and that counts for governing in times of surplus.

Final results:

Bright Future: 0 seats, -4 seats; 1.2%

Progressive Party: 8 seats, as in 2016; 10.7%

Revival: 4 seats, -3; 6.7%

Independence Party: 16 seats, -5; 25.2%

People’s Party: 4 seats, new; 6.9%

Centre Party: 7 seats, new; 10.9%

Pirate Party: 6 seats, -4; 9.2%

Social Democrats: 7 seats, +4; 12.1%

Left Greens: 11 seats, +1; 16.9%

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

While waiting for the elections results

Short and sharp election campaign has come to an end. Foreign media, especially in the other Nordic countries, finds it difficult to understand that a prime minister, Bjarni Benediktsson, who has been anything but forthright on his business affairs before and around the 2008 banking collapse might well yet again be the leader of the largest party.

In addition, there is suspicion that the minister of justice dealt differently with clemency case for a pedofile because the Benediktson’s father helped the pedofile seeking clemency. And the disgraced leader of the Progressive Party Sigmundur Davíð Gunnlaugsson, forced to resign laster year as PM and party leader due to the Panama Papers is back in politics as a leader of his own party, the Centre Party.

Trust has been an issue in the election campaign but no matter these issues Benediktsson’s Independence Party is on a roll and Gunnlaugsson is doing remarkably well, might get around 10% of the votes. So do Icelanders not care about ethics in politics? Well, to a certain degree they do – after all, Gunnlaugsson couldn’t avoid resigning. But all in all, other matters seem to be more important to Icelandic voters. The Independence Party voters and party member have not demanded that their leader should resign.

Environmental issues have been more prominent than earlier, a reflection of the fact that tourism is now the most important sector, contributing more than the fishing industry, the country’s mainstay for decades. However, it was interesting to notice that in the main tv debate, Thursday evening, where leaders of the eight parties, likely to get an MP elected or who have an MP, debated, three leaders did not mention the environment as important: Bjarni Benediktsson, Sigmundur Davíð Gunnlaugsson and Inga Snæland, leader of the People’s Party, a new populist party that seems to be losing ground.

Some stats at the end: Icelanders are 343.960, registered voters are 248.502. Up for elections are 63 seats in Alþingi, the Icelandic parliament. In total, 11 parties offer candidates but seven might get candidates elected: the Independence Party, Left Green, the Social Democratic Alliance, the Centre Party, the Pirates, the Progressive Party, Revival; Bright Future, the party that withdrew from the government, causing it to fall, seems not to have gained from its decision and might disappear from the Alþingi.

My earlier blogs on the elections, here, here and here.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Iceland: political instability in spite of “doing it right”

To claim that Iceland has done all the right things since the financial crisis is hubristic. However, in the grand scheme of things it can be argued that the four governments, in power from 2008 until now, have broadly speaking done what needed to be done: the banks were dealt with without too great a public cost, an independent commission investigated the causes of the crash, matters related to the time up to the collapse have been investigated and individuals prosecuted; the economic policies have broadly stimulated growth, lately fuelled by boom in tourism. Yet, all of these sensible measures have not secured political stability as can be seen by elections held in 2016 and 2017.

Already by summer 2011 Iceland was back to economic growth in spite of the calamities of the banking collapse in October 2008. In spring the previous year, the Special Investigative Commission, SIC, had published its report. In the following years, the Office of the Special Prosecutor, now the District Prosecutor, was busy investigating and bringing bankers and their business partners to court. Well over twenty people have been imprisoned.

Iceland was not the only country hit by the financial catastrophe starting in 2007. In countries like the US and Britain, voters’ anger is often explained by the fact that in these countries little has been done to clarify what went on in the banks, the creators of the financial turmoil that hit various Western countries in 2007 and the following years.

In a long blog in September 2015 on the Icelandic recovery I pointed out that in spite of good recovery and growth the soul of the Icelanders was lagging behind: voters did not seem to embrace the parties bringing them a growing economy. That still seems to be the case judging from the political situation. Trust in political parties and party support is unstable and swinging.

This could very well be the future in Iceland as elsewhere: no matter the growing economy voters don’t put their trust in political parties as they once did, fewer belong to political parties or identify with a single party. It really isn’t about the economy any longer but a more elusive public mood.

Elections one year, minus a day, from the 2016 elections

Last year, the election was held on 29 October. This year it is on 28 October. Last year, the election was brought about by the then PM Sigmundur Davíð Gunnlaugsson leader of the Progressive Party having to step down due to the exposure in the Panama Papers of an offshore company held by him and his wife. The 2016 election ended the two-party coalition with the Independence Party (C) led by the Progressive Party.

In autumn this year, the coalition with two new centre liberal parties, Bright Future and Revival, led by the Independence Party fell when Bright Future lost the trust in PM Bjarni Benediktsson, a story recounted earlier on Icelog. When leaked document on Benediktsson’s business dealings in 2008, conflicting with his earlier explanations surfaced recently it seemed this would weaken the party’s standing (see Icelog).

A swing from left to right – but yet an Independence Party disappointment

To begin with, opinion polls indicated that a left government, albeit a coalition of three to four parties, was looming on the horizon – the only Icelandic left government that ever sat a full parliamentary term was the left government in power 2009 to 2013. The Left Greens and Katrín Jakobsdóttir, the party’s very popular leader, seemed to be raking up a lot of votes, at one point giving the Left Green a clear lead as the largest party. The Social Democratic has been in a limbo since the 2013 elections; its new leader, Logi Einarsson, did not seem to appeal to the voters but might have been a necessary support for the left government

In the last few days, the political landscape has been changing dramatically with the Independence Party surging ahead of the Left Greens. In a historic context the Independence Party surge is no surprise and also last year the party surged ahead in the last few days up to the elections. In one sense this indicates support for Bjarni Benediktsson and his party but the numbers are less uplifting: the party stands to lose around 3 to 5% and possibly four MPs. In addition, the forecast now would be a historic low for Benediktsson’s party, far from its 20th century earlier glory of licking the 40%.

The most surprising swing is the Social Democrats great gain in the polls. They seem to be attracting votes from the Left Green and the Progressive Party. Revival is crawling above the 5% threshold, needed to get the first MP elected. Only some weeks ago the party hastily elected a new leader, Þorgerður Katrín Gunnarsdóttir, after party founder Benedikt Jóhannesson’s unfortunate remarks on sufferers of sexual violence. Gunnarsdóttir is an earlier Independence Party MP and minister who left politics for some years after 2008 due to her links to Kaupthing where her husband worked. In a Parliament of very inexperienced MPs Gunnarsdóttir has proved a skilled politician.

Another surprise: former Progressive leader, the disgraced Gunnlaugsson, who resigned in autumn from his old party to form a new one, the Centre Party, is making good progress, well ahead of his old party. This, although Gunnlaugsson has mostly been invisible in Parliament all through the year though not calling in a substitute and hardly seen at all around in Iceland. Gunnlaugsson seems to be pinching votes from his old party and the Independence Party.

Nine parties are or have been likely to get an MP but it now seems that in the last spurt only seven parties will be represented in Alþingi, the Icelandic Parliament.

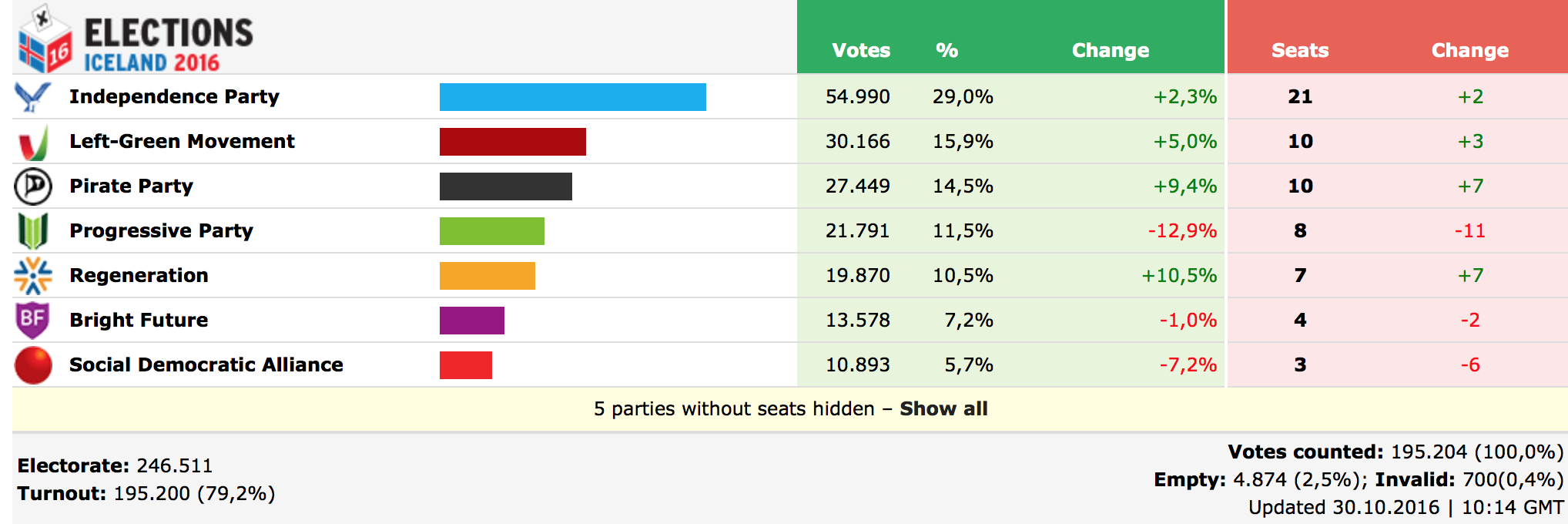

The 2016 results

(Regeneration is the party I call Revival, a name the party itself uses, Viðreisn in Icelandic)

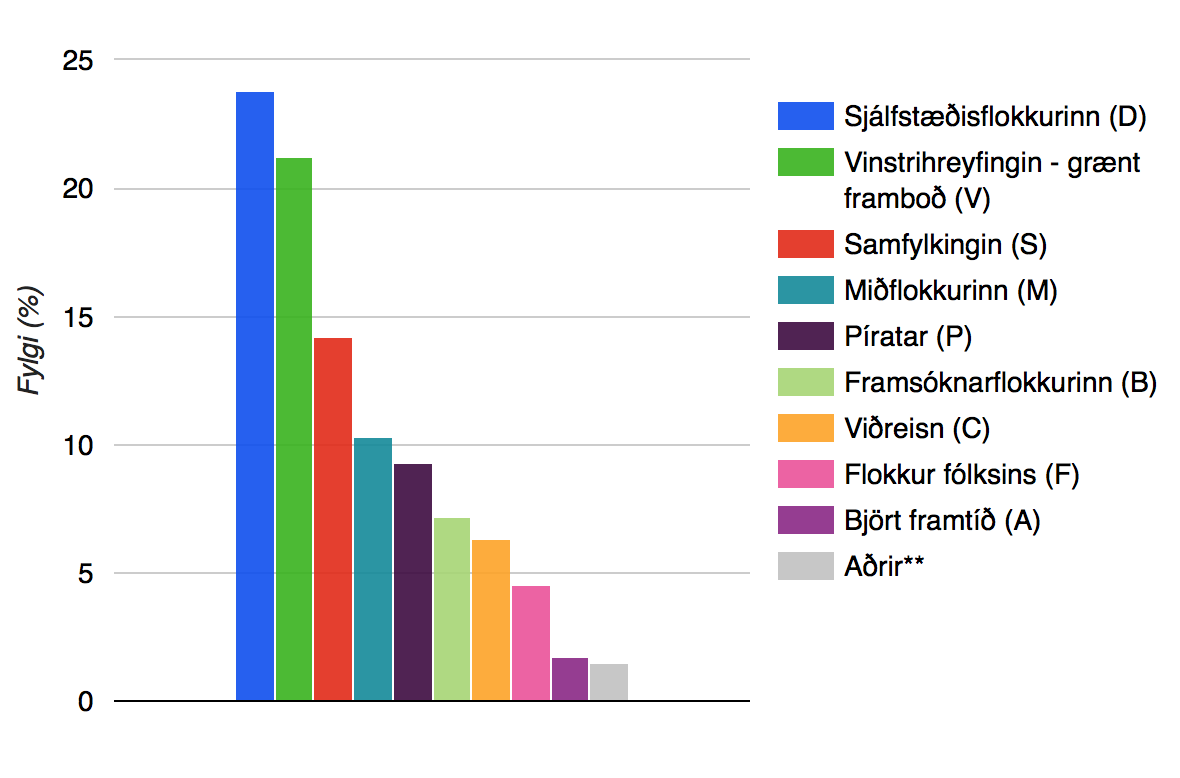

A poll of polls 26 October 2017. From the left: Independence Party, Left Green, Social Democrats, Centre Party, Pirates, Progressive Party, Revival, People’s Party, other parties below the 5% threshold. From Kosningaspá.

The attraction of the new – this time it’s the new-old Centre Party

The Pirates were the stars of 2016 election though they did not make it into government. This time they are doing less well, judging from the opinion polls.

A populist party, the People’s Party, had some chance of being the new stirring choice. The party has an unclear policy except promising a lot of money for every good cause. At the very beginning it seemed it would take up the topic of immigration only to drop it very quickly. The party is now losing ground and might not even make it into Parliament.

The new political kid on the block, Gunnlaugsson’s Centre Party is doing remarkably well, showing that Gunnlaugsson has a strong appeal in spite of his Panama Papers disgrace, a story he tries to manipulate in the face of facts when he gets the chance. Gunnlaugsson is the only leader heavily playing the immigration card. This comes as no surprise, he has been dallying with the topic before but so far, it has not proved to be a winning topic.

In this respect, Iceland has so far proven to be a real exception compared to the US and most European countries. Although immigration is rising rapidly in Iceland there is plenty of work to be had, more than can be filled by only Icelanders. For years and now decades, foreigners have been crucial for the fishing industry and now they keep the tourist industry and other services going.

Gunnlaugsson has always had a populist flare, promising handouts to voters. In the election 2013 he promised to take money from the failed banks’ creditors and give to voters. The plan, introduced with fanfare in November 2013 was nothing of the sort: it was part publicly funded part funded by those who were qualified to apply.

That hasn’t stopped Gunnlaugsson from claiming he kept his promise and again he waves a bundle of money in the face of voters: he promises to give Icelanders publicly held shares in Arion Bank, seemingly similar to the Russian handout of shares in the early 1990s. The idea is to secure a spread ownership and give Icelanders shares in coming profits – an idea that doesn’t stand up to scrutiny. Gunnlaugsson has mentioned the shares will amount to ISK150.000-200.000, €1200-1600.

Topics and European thoughts

A membership of the European Union has not been on the campaign agenda. The leader of the Social Democrats Logi Einarsson has mentioned Icelanders could vote on continued membership negotiations as early as next spring. Due to lack of interest in all things European such a vote is unlikely unless the Social Democrats are in government. This got Einarsson a headline the day he said it but it is not a reverberating topic.

Revival was very much founded in order to offer conservative voters with European leanings a new option instead of the anti-EU Independence Party. However, Revival has put little emphasis on the European ticket and has been more taken up with classic Social Democratic welfare issues.

The main election issues have been welfare, health care and to some degree education as well as classic Icelandic topics such as fishing quotas and power plants versus preserving untouched nature.

Possible outcomes – again, back to the old conservative roots

With a swing from the left to the right, the outcome might be similar to last year when I pointed out that Iceland was, yet again, returning to its old conservative roots. The Independence Party has been the back-bone of Icelandic politics after World War II, left governments have been the exception, contrary to the social democratic Nordic countries (though less so the last few years: only in Sweden the social democrats are now in power).

For the time being it is very unclear what sort of government might be in sight after the elections on Saturday. Last year, it took over two months to form what eventually was the three-party coalition. It might not be much easier this time but as things stand now it is almost certain that Bjarni Benediktsson will first be given the mandate to form a government. Last year, he only managed to do it after failing the first time around and after other leaders had tried.

What sort of coalition?

There are speculations of a coalition over the political spectre, with the Independence Party and the Left Green join forces. An unpopular choice for many Left Green voters but perhaps less so if it proves to the party’s only viable path to government.

A blue-red-green government would most likely be arch-conservative, not in the sense of the Independence Party but beholden to special interests in the fishing industry, unwilling to great changes. However, as things stand now the two parties alone will not have a majority.

Benediktsson has said that he would not be keen on leading a three-party coalition. His experience as a PM has clearly not been a happy one: unable to turn the government into a good team he failed the prime minister test. His government lacked the necessary team spirit.

Will Gunnlaugsson made a come-back in government? It is uncertain that an election victory will bring the Centre Party into government because Gunnlaugsson is highly unpopular among the politicians he was in government with. He proved highly unreliable, often incommunicado for days, not showing up at the Prime Minister office, not taking the phone from his fellow ministers. And no one knew where he was. Benediktsson, who was minister of finance in the Gunnlaugsson-lead government, is rumoured to be most unwilling to repeat the experience.

Minority governments have been a rare occurrence in Iceland, not seen for decades, contrary to the other Nordic countries. A minority government will hardly come into being until all option for a majority government have been exhausted. But then, knowing the voters would appreciate it the political party may also be preparing a real surprise: a speedily formed majority government. Given the various alphabetical options, the depressing outlook is another elections in a year’s time.

Here is my overview of the results of the October 2016 elections.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Why are Icelanders good at football… and music?

Björk and Sigurrós may be the most famous Icelandic musicians but there are many others. Now, footballers are doing pretty well. Better tame the football hubris for the time being but there are good reasons for Icelanders to excel in these two fields: young Icelanders have very good opportunities in both.

Recently, I watched a program on Rúv, the Icelandic broadcaster, on kids at the age of 12 to 14 preparing for a national science contest. The program followed the kids, from all around Iceland, at home and in school. One question they all got was what their did in their spare time. The answer? Each and every of them either did sport or music, some did both.

This is nothing new. After the war, the Icelandic music life was revived, or rather to a great degree, created by some Icelanders who had studied abroad and by a few foreign musicians who chose to make Iceland their home. The music life, also the music education, is still to some degree nourished by foreigners. This, in addition to many Icelandic musicians.

Most kids, not only in Reykjavík but also outside of Reykjavík, have access to music education. Many schools have school orchestras where children are taught to play the various instruments that make up an orchestra.

The same with sports. All over the country there are good facilities for the various sports, most notably football, handball and swimming.

It is from a broad base of nurtured talent that Björk and Sigurrós grew – and in football, footballers like the captain of the Icelandic national team Aron Einar Gunnarsson and Björn Bergmann Sigurdsson. Globalisation has helped these talents, both in music and football, to grow far beyond the amateur level with the world as their stage or their field.

Most of the football players playing for Iceland either do play professionally abroad or have done so. In addition they have grown up in the under 21 national team. Then there was the good work of the Swedish trainer Lars Lagerbäck whose assistant trainer Heimir Hallgrímsson is now the trainer of the national team.

Most national teams can count on their countries to support them. In Iceland, the support is tremendous. Basically everyone who is old enough to be aware of the world and not too old to be completely out of it, has his or her whole heart behind the team. On days with important international matches the traffic all over Iceland stops. Completely.

Just to qualify for the World Cup was a fantastic achievement, on the Icelandic scale of achievements – the smallest nation ever to qualify. The joy was profound. Icelanders definitely did not take it for granted that their team would indeed qualify.

From now on, every victory will be a bonus, deeply felt all over the country. The small economy will be shaken by every victory: consumption – such as buying trips to Russia – will go through the roof, productivity will most likely fall if Iceland wins a few matches.

But as you wonder why Icelanders can be so good at music and football keep in mind that it has nothing to do with some sudden wonder: it’s based on good education and easily accessible opportunities and facilities for decades. Something that every nation could match, if it is willing to invest in its youth and equal opportunities in education.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Benediktsson’s saga, the 2008 crash and how some were luckier than others

Nine years after the October 2008 financial crash Iceland is doing well, some justice was done as bankers and businessmen have been sentenced for criminal deeds up to the crash that has been better clarified than anywhere else. Yet, the collapse still looms large in Icelandic politics. Prime minister Bjarni Benediktsson leader of the Independence party is now being asked questions regarding certain transactions before the banking collapse 6 October 2008. An impertinent question is why the banks did indeed open on that day – it did allow some well-connected people to diminish the hit as the banks collapsed.

The family of PM Bjarni Benediktsson can lay claim to being the only political dynasty in Iceland. Often referred to as “Engeyingarnir” – the “Eng-islanders,” Engey being the island on the gulf by Reykjavík – the family has been wealthy and powerful for most part of the past century and still is. The family rose on the basis of fishing industry in the early 20th century but later extended into transport, insurance and banking. The minister of finance and leader of the coalition party Revival Benedikt Jóhannesson is closely related to the PM.

As some other big shareholders in the banks and other companies “Engeyingarnir” were heavily involved in conspicuous transactions in the months and hours up to 4pm 6 October 2008 when the Emergency Act was passed. That Act and that day mark the realisation of the collapse (the three banks had all failed by 9 October). One chapter relating to Benediktsson has now been added to that saga, as told in the Guardian and the Icelandic newspaper Stundin – it was known earlier that Benediktsson sold a position in Glitnir investment funds but the latest reports provide the figures: in total, ISK80m or c €643.000.

Most aspects of the collapse were painstakingly recounted in the 2010 report of the Special Investigation Commission, SIC, the most thorough report any nation has written on the 2007 and 2008 financial crisis. But Benediktsson’s story is a reminder of one catastrophic mistake of the government at the time: to open the banks on Monday 6 October 2008, thus giving privileged clients like Benediktsson the opportunity to make transactions, which minimised their losses following the collapse that no one except a small group around the prime minister knew of.

Last minute transactions under dark clouds

The core of the Guardian story is that up to the October 2008 crash Benediktsson sold assets in two investment funds, managed by Glitnir, the smallest of the three large Icelandic banks.

Late September 2008 it was clear that Glitnir could not meet its obligations in the following October. At the time, Glitnir was controlled by its largest shareholder Jón Ásgeir Jóhannesson and his partners. Jóhannesson is a famous name in the British business community as he owned at the time large retail companies on the UK high street.

The bank’s leadership had no option but to agree to a government takeover of 75% of the bank, thus saving the bank but almost wiping out the shareholders. Only days later it was clear that the bank was in such a state that the 75% takeover was not viable.

Just before midnight of 29 September Bjarni Benediktsson attended an emergency meeting with MP Illugi Gunnarsson, a friend of Benediktsson and also on the board of Fund 9, one of the two investment funds of this story. Together with chairman of Glitnir Þorsteinn Már Baldvinsson they met with Glitnir’s CEO Lárus Welding and Glitnir’s legal council. Why exactly the two MPs were at this meeting is not clear: their connections to Glitnir seems a better explanation rather than the fact they were both MPs.

Why was Fund 9 so toxic?

During these tumultuous days Benediktsson set in motion some private transactions. On 24 September he sold off ISK30m, €241.000 in a Glitnir fund called Fund 1, and bought Norwegian krone, which turned out to be a wise transaction given how much the ISK fell in the coming days and weeks. Incidentally, this happened on the same day that the chairman of Glitnir, Þorsteinn Már Baldvinsson met with governor of the Central Bank Davíð Oddsson to inform him that the bank could not meet its obligations in October.

On 2 October Benediktsson again sold ISK30m, this time in Fund 9 and then again ISK21m on 6 October. In an email the week before Benediktsson had specifically instructed for this latter transaction to be carried out on 6 October.

Late on 5 October PM Geir Haarde said to the Icelandic media that no further actions were needed regarding the Icelandic banks. At 11.29am 6 October the Icelandic financial surveillance authority, FME, effectively closed the Icelandic financial institutions. Benediktsson was one of several well-positioned people who made transactions on that morning.

Fund 9 was a particularly toxic fund because it was full of bonds connected to Jóhannesson’s companies and Glitnir, which, given that these companies relied so heavily on Glitnir funding, would clearly be heavily hit if Glitnir failed. That was indeed the case: these companies suffered heavy losses.

When Fund 9 opened again at the end of October 2008 its assets had been written down: the fund was now only 85.12% of what it had been on 6 October. However, if PM Haarde and the minister of finance had not bolstered Fund 9 with ISK11bn, now €88.5m, of public funds after the fund was closed the situation of the Fund 9 investors had been much worse. It has never been clarified why public funds were used to help Fund 9 investors and not investors in many other funds.

As Benediktsson had sold his Fund 9 assets worth ISK51m he was unaffected by the Fund 9 losses. In addition, there were the Icelandic króna Benediktsson converted into Norwegian krone. – In a media interview last year Benediktsson said he had owned “something” in Fund 9, nothing substantial and could not really remember the figures.

Benediktsson sold Glitnir shares in bleak February 2008

These were however not the only transactions Benediktsson made in 2008. In early February 2008 the future of the banks looked worryingly bleak though publicly bankers and politicians denied it. In addition to evaporating funding on international markets foreign banks were making margin calls on all the major Icelandic businessmen who also happened to own large parts of the banks.

The banks were now in a turbo-drive to help this selected group of businessmen to pay off their foreign loans, thus increasing lending to the selected few when lending was generally withdrawn. One of these businessmen was Karl Wernersson who in 2006 had bought large part of the Engeyingar’s shareholding in Glitnir.

The foreign margin calls led to some financial acrobatics for Wernersson, which also involved the Engeyingar because of the 2006 sale. This case, called the Vafningur (Bundle) case centres on loans from Glitnir and Sjóvá, an insurance company controlled by the Engeyingar.

Benediktsson signed some of the documents on behalf of Vafningur. The Sjóvá lending involved alleged fraudulent use of Sjóvá’s insurance funds. In the end, the case was not prosecuted and Benediktsson has always claimed that in spite of his signature he really did not know what the whole case was about.

One key event in February 2008 was a meeting of the three governors of the Central Bank with PM Geir Haarde, Árni Matthiesen minister of finance and leader of the social democrats Sólrún Gísladóttir minister of foreign affairs. The governors were profoundly pessimistic and news of this meeting flew around among politicians and others though it did not reach the media.

It’s not known if Benediktsson knew of the meeting and the unhappy tidings there. However, on 19 February Benediktsson and his friend Illugi Gunnarsson met with Lárus Welding CEO of Glitnir and the bank’s legal council, a meeting Benediktsson did ask for. Two days later Benediktsson set in motion to sell ISK119m, now €960.000, of his Glitnir shares, keeping only ISK3m. The transaction was carried out between 21 to 23 February 2008. On the 26 February Benediktsson and Gunnarsson wrote a much noted article in Iceland, outlining the dire straits of the Icelandic banks with no mention that Benediktsson had already sold the lion share of his shares in Glitnir.

Of the ISK119m worth of shares he sold he placed ISK90m in Fund 9. In March his assets in Fund 9 amounted to ISK165m, €1.3m. – In 2011, the daily DV told the story of the share sale, incidentally written by Ingi Freyr Vilhjálmsson who is also behind the latest and revealing reports in Stundin. At the time, Benediktsson refused to comment.

The power and influence of a prominent family

What was Bjarni Benediktsson doing in 2008? He was an MP, investor, close friend with some of the Glitnir staff, a member of a family who had been one of Glitnir’s largest shareholder and wielded considerable power in Icelandic politics and businesses. And Benediktsson had been a guest on some of Glitnir’s more ostentatious trips in the years before, such as football in London and salmon fishing in Siberia.

Benediktsson, born in 1970, became a member of Alþingi in 2003 but held at the same time positions in family companies. Not until after the 2008 collapse did he leave the family businesses where he had been on the boards of several companies.

Stundin has now exposed a far more detailed account of Benediktsson’s business dealings than was previously known, such as a failed property adventure in Dubai, related to his offshore company found in the Panama Papes and a much more successful venture in Miami, where Benediktsson was in charge of payments to constructors, literally all through the October 2008 collapse.

Due to the family assets and connections he had a far deeper relationship with Glitnir than just being an MP who happened to bank with Glitnir. His father Benedikt Sveinsson and his uncle Einar Sveinsson had been one of the largest shareholders of Glitnir 2003 to 2006. His uncle Einar was indeed the bank’s chairman at the time. Both his father and uncle sold both shares in Glitnir in 2008 and their positions in Fund 9 just before the banking collapse.

During these fateful autumn days Benedikt sold for ISK500m in Fund 9 and had the proceeds wired to Florida where the family has property. Einar sold for over ISK1bn. If the two brothers had waited Benedikt would have lost ISK24m due to falling value of Fund 9, his brother ISK183m.

An email from uncle Einar to a Glitnir employee on 1 October 2008 throws light on the kind of relationship the family had with Glitnir. The bank had made a margin call. “I don’t need to waste words,” wrote Einar, “that I don’t like this kind of message from the bank” expecting the employee to follow earlier decisions made.

The Teflon man of Icelandic politics

Benediktsson has been leader of the Independence party since 2009 but the rumours related to his family businesses have never left him. Apart from his sales of Glitnir shares and assets in Glitnir and the highly contentious Vafningur transactions, Benediktsson and his family have been associated to more recent cases.

In 2014 Benediktsson was minister of finance when Landsbanki, a state-owned bank, sold off a credit card company, Borgun. Borgun was sold without any bidding process, in fact it was sold without anyone knowing anything about the sale. Until it transpired Borgun had been sold to a consortium led by Benediktsson’s uncle Einar Sveinsson. This, in spite of the public policy of selling state assets in a transparent process to a highest bidder.

It later turned out that Borgun had been heavily undervalued. Less than a year after the sale, Borgun’s equity amounted to almost twice the sale’s price. Eventually, the Landsbanki CEO and board were forced to resign due to the Borgun sale. Benediktsson has always claimed he had been wholly oblivious of the whole thing, both that Borgun would be sold in a closed sale to a company of his uncle and the undervaluation.

Last year, the Panama Papers exposed that Benediktsson had owned part in a Seychelles company, set up by Mossack Fonseca. Only a year earlier, Benediktsson had staunchly denied he had owned a company in a tax haven. Asked about the Seychelles company he said he had not known it was offshore since it was set up through Luxembourg. Again, Benediktsson was blissfully ignorant and his party supported him.

The latest case, that also landed Benediktsson in international headlines, related to a bizarre relationship between his father and a sentenced paedophile. Iceland does not have a sex-offenders registry and people who have abused children can, as others who have been sentenced, recover their civil rights via a clemency process.

Called “honour revival” it requires a statement to confirm the soundness of character of the person in question. Benediktsson’s octogenarian father had given a statement to the sentenced paedophile who the father knew through old friends. What gave rise to questions was not that Benediktsson should be held responsible for his father’s action but that the minister of justice might have dealt with the case differently because of the family connections.

6 October 2008: the right and wrong decisions

As to the latest story of his Glitnir dealings Bjarni Benediktsson staunchly refuses he had any inside information. He just acted on what everyone could see: the banks were in serious trouble. His party still supports him.

It is worth keeping in mind that a large part of the Icelandic population owned shares in the banks. Many people saving up for their pension had, apart from obligatory savings via pension funds, privately saved by buying shares in the banks. Grandparents and parents had given children shares to save for their adult years. There were almost 40.000 shareholders in Kaupthing, the largest bank.

Benediktsson now says everyone knew the situation was precarious and he had only been trying to protect his assets. It is however not correct that everyone knew. The small shareholders quietly hoped the bankers were in control and that both bankers and politicians were right when they said publicly that everything would be fine.

The fact that the banks were kept open on the morning of 6 October 2008 was the wrong decision. It allowed the well-connected to take precautions but was of no help for the small shareholders who had no idea what was going on.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

A fallen government and breach of trust

The Icelandic government has fallen due to lack of trust – Bright Future has decided to leave the government. That is the simple fact. The story behind this is a tad more complicated, based on a horrid story of sexual abuse, a strange system of “reviving honour” after an ended prison sentence and connections to the father of prime minister Bjarni Benediktsson leader of the Independence party. Benediktsson, the Teflon man of Icelandic politics, again has a case that raises questions but so far, he has not lost the trust of his party. He now wants to call elections in November. – This is not a case of pedophilia but of politics and trust.

The shortest lived government in the history of Iceland and the third government led by the Independence party to fall has now come to an end, greatly challenging the party’s claim to be the great stabiliser in Icelandic politics. The only government after the 2008 banking collapse that so far has lasted its full parliamentary term is the left government, which did manage to sit the full 4 years though struggling at times.

In spring last year, Bjarni Benediktsson pulled his party out of government led by the Progressives’ leader Sigmundur Davíð Gunnlaugsson; the reason was lack of trust. Gunnlaugsson, named in the Panama papers, had for weeks known of the infamous interview where confronted with evidence he walked out. When Benediktsson saw the interview he walked out of government.

This time, the story could not be more different but at the bottom is, again, lack of trust. Benediktsson did not inform his fellow ministers that his father had signed a statement of character for a sentenced pedofile seeking to rehabilitate his honour and thereby seeking to reclaim civil rights lost due to his long prison sentence.

The sordid origin of a political story

Róbert Árni Hreiðarsson is a lawyer, earlier convicted for grooming under-aged girls in a particularly vicious case. After ending his sentence he changed to name to Robert Downey (apparently taking up the name of his American father). A convicted lawyer can’t enter the legal profession again unless he goes through the process of rehabilitating, “reviving his honour” as it is called in Icelandic.

The process can be initiated five years after ending a prison sentence and implies inter alia getting someone to sign a statement confirming that this person is indeed a sound and good person. Though not without exceptions, this has mostly been a rather mechanical process where the rehabilitation is rarely denied.

The fact that Downey seemed so easily to get his place in society again caused a widespread disgust in Iceland. The father of one of his victims aired the distress of the family, shared by many Icelanders. Rúv, the Icelandic state broadcaster, tried for months to get minister of justice Sigríður Andersen, also an Independence party MP, to inform who had supported Downey in “reviving his honour.”

The very Icelandic story of a pedofile connected to the PM’s father

As a side story, the attention was also on others sentenced for sexual abuse and who had helped them to rehabilitate. One of them is a Hjalti Sigurjón Hauksson, sentenced for years of abusing his under-aged stepdaughter. It now turns out that one of those who assisted Hauksson was a well known businessman Benedikt Sveinsson, father of PM Bjarni Benediktsson.

Mostly, those who assist ex-prisoners to regain their full civil rights are people who have some standing in society and who known the convicted people for a long time. So what are the connections between Sveinsson, firmly in the centre of power and money in Iceland, and a sentenced pedofile?

In a press release, Sveinsson says that Hjalti Sigurjón Hauksson was for a while related to acquaintances of him and his wife from their school years and that Hauksson had over the years sometimes sought his help, mostly related to financial matters or work. Last year, Hauksson had brought him a letter for Sveinsson to sign, in order to use for his process of regaining his honour. Sveinsson signed the letter as it was, thereby signing off that Sveinsson now merited to be rehabilitated.

Hauksson has worked as a bus driver, also working for a bus company owned by Sveinsson and his family. This bus company has the license to operate on the very lucrative route Reykjavík – Keflavik airport.

Nagging suspicion and belated acknowledgment

With the focus on Downey there had been some political manoeuvre, which caused suspicion and the media kept asking for more information. In hindsight, some media probably hard heard of a connection to the PM’s family that kept the Downey case alive in the media.

Following a Rúv Freedom of Information request, which ordered the ministry of justice to release information, Sigríður Andersen was just about to release information not only on Downey but all similar cases since 1995. On Monday, PM Benediktsson informed the two other coalition leaders that his father was implicated in one of these cases.

According to Óttarr Proppé leader of Bright Future he was then of the understanding that this information was about to be released. But when he then understood yesterday that Andersen had informed Benediktsson in July about his father’s involvement with the known pedofile, Proppé and his party concluded that this was such a breach of trust that leaving government was the only option.

Benediktsson adds to his list of political mishaps

There is no allegation of any connection between Benediktsson and a sentenced pedofile and this case has nothing to do with pedophilia, contrary to headlines in foreign media. The government did not fall due to a case of pedophilia but due to breach of trust, how Benediktsson had handled the case and if the minister of justice had acted properly by informing the PM of his family connections to this specific case.

But this case adds to Benediktsson’s list of mishaps that have so far not tainted his standing as a political leader. His father was connected to a banking collapse case, called the Vafningur case, related to illegal use of funds of Sjóvá, an insurance company where the family has for decades been a major shareholder. The case was not prosecuted. Benediktsson gave a witness statement where he claimed he had not known the details.

In 2014 Benediktsson was the minister of finance when the state-owned Landsbanki sold a credit card company to a consortium of businessmen. It later turned out the bank had grossly undervalued the company leaving a huge windfall to the consortium. Again, Benediktsson had been wholly aware of the whole thing.

Last, but not least, Benediktsson figured in the Panama Papers. He had owned an offshore company, holding failed investments in Macao. By saying this had all been only losses and was long gone, Benediktsson was able to move on and keeping his position as an undisputed leader of his party.

The political aftermath

So, what now? The first reaction was that the government had now fallen and there would be a quick election though there have also been rumours of other options. There are theoretical options for the government to continue operating for a limited time – for two months or so, long enough for the government to pass the budget, or if its live could be stretched until spring. Benediktsson has said he would prefer to call elections in November.

Sigurður Ingi Jóhannsson leader of the Progressive party, an old coalition partner of the Independence party, denied quite harshly today that he was interested in filling Bright Future’s seats in government. At the same time, the rumour mill claimed the party was indeed interested in this option. Less easy now after Jóhannsson’s firm denial.

One mealy-mouthed politician today is Benedikt Jóhannesson minister of finance and leader of “Revival,” partly a splinter party out of the Independence party touting itself as a liberal euro-phile party contrary to the old party of anti-European sentiments and special interests. Contrary to other Revival MPs, Jóhannesson was remarkably unwilling to criticise Benediktsson and unwilling to mention breach of trust. In a country where blood is thicker than water, all Icelanders know full well that Jóhannesson is closely related to Benediktsson.

Quite remarkably, Iceland has in many ways done all the right things following the banking collapse in 2008 – it investigated the collapse, prosecuted bankers and shareholders and its economy turned to growth already in summer of 2011. Yet, it has not yet found political stability or political strength. That however has perhaps more to do with the times we live in: in Iceland, the widespread demand for transparency keeps running against political love of opacity.

The Independence party and its loss of claim to stability

Given that the world has lately seen Brexit and Trump victory, I’ve been saying tongue in cheek that if there will be elections soon Iceland might wake up to a government of Independence party, the Progressives and a new anti-immigration populist party called Party of the People. So far, it is a joke (albeit not funny).

The new party has caught the favour of voters always looking for a new solution to the world’s ill. The Pirate party has held much of these votes but seems to be losing them to this new party. Compared to other European countries, anti-immigration sentiments have not surfaced as a political force in Iceland. Not for lack of trying: the Progressives have flirted with these sentiments but so far, no success. However, as we have seen, such a party can pull other parties in its direction. Remains to be seen.

In terms of political reputation, the greatest loser from this debacle is so far the Independence party: it has for decades laid claim to its central part in Icelandic politics as the great stabiliser. Now, the party has set a new record: the three last government is has sat in – after elections in 2007, 2013 and 2016 (with government formed in January 2017) – have fallen.

But as the Independence party knows better than any other party it can normally rely on its voters, no matter what. It has been hovering around 25% of votes in opinion polls lately, record low compared to its earlier glory of close to 40%. Our times of flimsy voters might test this but other parties have a lot harder battle, especially the two other coalition parties who are in danger of not getting any MP though Bright Future might have created some political sparks by walking out of government. All to be tested in November…

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Landsbanki equity release borrowers lose at first instance court in Paris

After investigations by judge Renaud van Ruymbeke on Landsbanki Luxembourg equity release loans the case against its main shareholder and chairman of the board Björgólfur Guðmundsson and eight ex Landsbanki employees was concluded in a Paris court yesterday 28 August: the judge acquitted all of them. The group of borrowers who have been seeking answers and clarification to their situation is hoping the prosecutor will appeal.

The main issue addressed by Justice Olivier Geron in the magnificent Saint-Chapelle yesterday was alleged fraud by the nine accused bankers. After clarifying some procedural issues, the judge read for an hour his verdict with gusto, making only a short break when he realised that one page was missing from his exposé.

The Justice established that the financial collapse in Iceland had not affected the bank in Luxembourg and there had been no connection between events in Iceland and Luxembourg. – That is one view but we should of course keep in mind that the Landsbanki Luxembourg operations were closely connected to the financial health and safety of the mother bank in Iceland as funds flowed between these banks and the Landsbanki Luxembourg did indeed fail when the mother bank failed.

The Justice also considered if the behaviour of the individuals involved could be characterised as fraudulent behaviour and concluded that no, it could not. Thirdly, he considered the quality of the lending, if the clients had been promised or guaranteed the loans could not go wrong. He concluded there had been no guarantees and consequently, no fraud had been committed.

Things to consider

I have dealt with the Landsbanki Luxembourg at length on Icelog (see here) and would argue that the reasoning of the French Justice did not address the grounds on which suspicions were raised that then led to the French investigation.

France is not exactly under-banked: it raises questions why the loans against property in France (and Spain, another case) were all issued from a foreign bank in Luxembourg. Keep in mind that equity release loans, very common for example in the UK some twenty years ago, were all but outlawed there (can’t be issued against a home, i.e. a primary dwelling). This is not to say these loans should be banned but, like FX loans (another frequent topic on Icelog) they are not an everyman product but only of use under very special circumstances.

It is also interesting to keep in mind that other Nordic banks were selling equity release loans out of Luxembourg. Also there, problems arose and in many cases the banks have indeed settled with the clients, thus acknowledging that the loans were not appropriate. Consequently, the cost should be shared by the bank and its clients, not only shouldered by the clients.

The judge seemed taken up with the distinction between promises and guarantees, that the clients had perhaps been promised but not guaranteed that they could not lose, not lose their houses set as collaterals. – The witnesses were however very clear as to what exactly had been spelled out to them. Yes, borrowers bear responsibility to what they sign but banks also bear responsibility for what is offered.

One thing that came up during the hearing in May was the intriguing fact that English-speaking Landsbanki borrowers got loan documentation in English whereas a French borrower like the singer Enrico Macias got documents in English to sign. One English borrower told me he had asked for an English version, was told he would get one but it never arrived. So at least in this respect there was a concerted action on behalf of the bank to, let’s say, diminished clarity.

Landsbanki managers have been sentenced in Iceland for market manipulation. This is interesting since many of the borrowers realised later that contrary to their wish for low-risk investments their funds had been used to buy Landsbanki bonds, without their knowledge and consent.

And now to Luxembourg

As I have repeatedly pointed out, Luxembourg has done nothing so far to investigate banks operating in the Duchy. The concerted actions by the prosecutors in Iceland show that in spite of the complexity of modern banking banks can be investigated and prosecuted. All the dirty and dirtiest dealings of the Icelandic banks went through Luxembourg, also one of the key organising centres of offshorisation in the world.

In spite of the investigations and sentencing in Iceland, nothing has surfaced in Luxembourg in terms of investigating and prosecuting. One case regarding Kaupthing Luxembourg is under investigation there but so far, no charges have been brought.

A tale of two judges and their conflicting views

Judge Renaud van Ruymbeke is famous in France for taking on tough cases of white-collar and financial crimes. Justice Olivier Geron is equally famous for acquitting the accused in such cases. One of Geron’s latest is the Wildenstein case last January where a large tax scandal ended in acquittal, thanks to Geron.

After the Enron trial and the US there has been a diminished appetite there for bringing bankers and others from the top level of the business community to court, a story brilliantly told by Jess Eisinger in The Chickenshit Club – and nothing good coming since the Trump administration clearly is not interested in investigating and prosecuting this type of crimes.

In so many European countries it is clear that prosecuting banks is a no-go or no-success zone. As shown by Ruymbeke’s investigations there is the French will there but with a judge like Geron these investigations tend to fail in court.

Update: the Public Prosecutor in charge of the Landsbanki case has decided to appeal the 28 August decision, meaning the case will come up again in a Paris court.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Landsbanki shareholders seek damages by suing Björgólfur Thor Björgólfsson – and more could follow

A whole new type of court cases is emerging in Iceland: shareholders are suing in civil cases for damages suffered as the collapse of Landsbanki and Kaupthing wiped out their shareholdings. Three recent Supreme Court decisions have paved the way for class action against Landsbanki’s largest shareholder, Björgólfur Thor Björgólfsson, to test if he was responsible for shareholders’ losses as the bank collapsed 7 October 2008. Those behind the Landsbanki class action intend to sue Kaupthing’s managers for the same reason, i.e. financial losses, based on a criminal case where nine Kaupthing managers have already been sentenced for market manipulation.

“Around thirty men are to blame for the banking collapse” – this is how Vilhjálmur Bjarnason, now member of Alþingi for the Independence party, dramatically described the situation a few weeks after Iceland’s three largest banks failed one after the other from 6 to 8 October 2008.

Bjarnason was himself one of tens of thousands of Icelanders who owned small shareholdings in the Icelandic banks, worthless after these October days in 2008. Some years ago, he was one of the instigators in setting up a group to test if damages could possibly be sought through class action.

Class action – a novelty in Icelandic courts

Nothing like that had ever been tried in Iceland and the path has proven tortuous. Last year, the Reykjavík District Court dismissed the case. The Supreme Court confirmed that decision but at the same time gave the group a direction to test: the Supreme Court pointed out the group’s diverse interests; after splitting the original group into three homogenous groups, according to when they bought the shares, the case was tried again. Again, the District Court threw the case out but the Supreme Court has now ordered the District Court to process the case.

This means that the three groups can now have their case tested.

The thrust of the case is that Björgólfur Thor Björgólfsson, as the bank’s largest shareholder, withheld relevant information that should have been in the bank’s annual accounts for 2005 and onwards. The information relates to loans to related partners, i.e. Björgólfsson and his father and also information regarding control over the bank. Had the shareholders been aware of this, they would not have wanted to invest in the bank.

A case built on the SIC report and witnesses

The case is partly built on the report of the Special Investigative Commission, SIC, published in 2010, which indeed recounts all of this. In addition, the group has sought documents and statements from witnesses in an earlier case, brought for the purpose of gathering evidence. If Björgólfsson will be found to have been in breach he will consequently be forced to pay damages to the shareholders behind the class action.

These attempts by the shareholders to sue Björgólfsson have been followed closely by the Icelandic media. Björgólfsson claims the action is utterly baseless and only a personal vendetta against him. One of the shareholders funding the action is Róbert Wessman, earlier CEO of Actavis. Shortly after Björgólfsson took over Actavis in 2007 Wessman left the company and founded his own generic pharmaceutical company. Wessman and Björgólfsson, who parted on bad terms, were for some years suing and counter-suing each other and as often reported in the Icelandic media there is no love lost between the two businessmen.

Kaupthing managers face action from the same shareholders

In October 2016, Sigurður Einarsson former chairman of Kaupthing, former CEO Hreiðar Már Sigurðsson and seven other Kaupthing managers were found guilty of market manipulation by the Supreme Court (see earlier Icelog). Since the managers have already been found guilty, the three groups behind the Landsbanki class action plan to sue Kaupthing managers personally for damages.

Who exactly will be sued is not clear but it seems highly likely that Einarsson and Sigurðsson will be among those sued.

*Here are the three recent Supreme Court decisions mentioned above: case 447/2017, 448/2017, 449/2017.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Media reactions to Georgiou’s conviction – Kathimerini: it’s a “witch hunt”

There has been a general outcry in international media after the recent sentencing of former ELSTAT president Andreas Georgiou following six years of persecution by Greek authorities. With the exception of Kathimerini, the Greek press has however mostly been silent. As pointed out in the foreign media the “witch hunt” bodes ill for Greece and now, ELSTAT is indeed struggling with the national statistics… again.

The reporting on the recent conviction of former ELSTAT president Andreas Georgiou in Greece and abroad is decidedly different: abroad there is condemnation and genuine worry, in Greece there is little of that though with noticeable exception: Kathimerini did not hesitate to speak of “witch hunt.” The Financial Times’s headline was a “legal farce calls Greek reform into question.”

The Georgiou case exposes a rift in Greek society

In a short and concise comment by the newspaper’s editor, Nikos Konstandaras, sets out how “the very name Andreas Georgiou – has come to symbolize a rift in society.” On one side there are those who worry about the future of Greece, “knowing that only rational measures will help Greece get back on its feet; on the other, a heterogeneous crowd of indignant citizens and cynical politicians, united by their passionate desire to abdicate responsibility for the past and the present, demands that reality bend to their will.

I am afraid that the second group has more passion, a longer history and the momentum that the first one does not: It is, of course, much easier to rouse the crowd with promises to avoid pain than to embrace it. And loading all the responsibilities for the country’s problems on one man, the former head of Greece’s statistical service, is most seductive: Those who are truly to blame get to play judge, while others believe that because one person is guilty for the crisis and for austerity, the rest don’t have to pay anything… History, though, will record the role they played. In the end they will be loaded with more blame than that which they are trying to saddle onto others.”

The political figure behind the ELSTAT persecution: Karamanlis

Even before the verdict at the end of July, Kathimerini was clear about the direction of the ELSTAT trial – Kostas Karamanlis is the driving force as shown on a cartoon where Karamanlis, playing a video game, is hell-bent on not letting Andreas Georgiou get away. Same could be seen in a recent article in Parapolitika: Karamanlis is still furious with Georgiou and could not hide his satisfaction when Georgiou was sentenced.

As mentioned by Kathimerini when it brought the news of the conviction, this was “the second time that the country’s top prosecutor overturned an earlier ruling in favor of Georgiou, in a case that has become a touchstone for relations between Greece and its creditors.”

The worrying thing is that the Karamanlis faction is still fighting the battles of 2010, still pretending that the fraudulent statistics, indeed exposed before Georgiou took office, are somehow part of evil foreigners kicking Greece.

Worries among international partners and professionals

The various international media and organisations are rightly worried about the relentless persecution of Georgiou: it is a clear sign of political unwillingness to face the facts of political governance in Greece.

For good reasons, the European Commission has been following the case with trepidation but so far it has been utterly unsuccessful in preventing the ELSTAT staff persecutions. Spokeswoman for the Commission’s financial issues Annika Breidthardt said after the conviction that it was not in line with previous acquittal for the same charges:

“The independence of statistical offices in our member states is a key pillar the proper functioning of the Economic and Monetary Union (EMU), this is why it is protected by EU law. We take note of the specific ruling which we note that is not in line with the previous ruling in the previous procedure. We understand that today’s ruling is open for appealing on legal grounds before the Greek Supreme Court. “We have full confidence in the reliability and accuracy of ELSTAT data during 2010-2015 and beyond” … We underlined the importance of the independence of ELSTAT as a key commitment under the terms of the Memorandum of Understanding of the Program,” said Breidthardt.

As the International Statistical Institute, ISI has pointed out, Georgiou acted in complete compliance with Eurostat practice, European Statistics Code of Practice: “Not only is the verdict unfair to Mr Georgiou, it also has negative implications for the integrity of Greek and European official statistics. Accordingly, the ISI calls on the Greek Government and the EU Commission, in consultation with their respective statistical authorities, to take all necessary measures to challenge this verdict and seek its reversal as a matter of the utmost priority.”

The absurdity of it all

As pointed out the The Greek Reporter there is the absurdity of the whole process: “Just to let the absurdity sink in: Greece falsified its official statistics for years & the only person prosecuted is the one who fixed them.”

Bloomberg commentator Leonid Bershidsky pointed out that the legal troubles of Georgiou “are about conflicting political visions of the country.”

In a personal and insightful article on Politico, the economist Megan Greene who has followed the Greek crisis from early on, raises the question of the integrity of Greece’s institutions.

New doubts regarding ELSTAT figures

There is now, again a looming suspicion hanging over ELSTAT. As FT reported recently, some discrepancy has surfaced regarding Greek national statistics, this time related to the country’s GDP figures leading the paper to connect this to the ELSTAT case: “The announcement came amid renewed scrutiny of Elstat following an outcry over the conviction by an Athens court last week of Andreas Georgiou, who headed the agency between 2010 and 2015 for “violating his duties.” Mr Georgiou faces a series of trials for allegedly inflating Greece’s budget deficit figure in 2009, the year the country plunged into financial crisis, even though all the statistics produced during his tenure were accepted without reservation by Eurostat, the EU’s statistical service.”

These are only few voices from a large choir of worrying voices. So far, Andreas Georgiou has been prosecuted for the last six years. As long as this is going on, the political forces around Kostas Karamalis clinging on to the past and obstructing a healthy revival of the Greek economy, have the upper hand. That is profoundly worrying for the Europen Union, the IMF and other international partners working with Greece for, hopefully, a better and more sound future for the country.

Greece needs an independent report on its crisis – as was done in Iceland

Incidentally, in Iceland after the October 2008 banking collapse there were also political voices claiming the collapse was all the work of foreigners somehow wanting to get control of Iceland, its natural resources etc. What finally and effectively silenced these voices was the very thorough report published in April 2010 by the Special Investigation Commission.

This independent commission did a brilliant work of clarifying all the relevant aspects of the collapse, from political apathy to the abusive control the largest shareholders had on the three largest banks. The report was an important step for Iceland in working itself out of the crisis but time has made it no less important: it is there as a reference in order to keep in mind what really happened so the time and selective memory cannot alter the facts. – Surely the kind of work sorely needed in Greece (and in all other crisis-hit countries).

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

The Trump saga in the grand scheme of Russian influence

During the Cold War, both the United States and the Soviet Union used various ways to influence political leaders and decision makers all over the world. Parts of the Soviet power structure, most notably of the KGB, live on in Russia. Three angles are of interest: 1) Vladimir Putin’s Russia has for years sought to influence the West via Nord Stream. 2) Admiration of Putin as the strong man thrives on the far Right in Europe and elsewhere. 3) The evolving saga of US president Donald Trump’s Russian ties might show a new side of Russian influence if it turns out that the Trump empire did receive Russian funds in its hour of need. – In addition, the Magnitsky Act proves to be an intriguing prism on Russian influence in the West.

Nord Stream and Nord Stream 2

The planning of a Russian gas pipeline from Russia to Europe started in the 1990s. It happened in an atmosphere of uncertainty following the collapse of the Soviet Union as to how the Russian relationship with the democratic West could or would develop. Some even thought Russia could join the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation, Nato.

From the beginning, Nord Stream was developed within and closely related to Gazprom, the Russian state-owned natural gas company founded in 1989 and a key factor in the Russian power structure. The first concrete step towards the pipeline was taken in 1997 but in 2005, the year the construction started, Nord Stream AG was incorporated in Zug, Switzerland. Gazprom has had various partners over the years but it still holds 51% of the shares.

In the countries affected by Nord Stream – Poland, the Baltic states, Finland, Sweden, Denmark and Germany – the effect of the pipeline in terms of environmental effect, national security, energy security and political influence has been a hotly debated topic all these years.

The pipeline was ceremoniously inaugurated in 2011 by Russian president Dmitry Medvedev, German Chancellor Angela Merkel and French Prime Minister Francois Fillon. Nord Stream 2 is now being planned.

Nordstream has always been about “Russia’s pipeline power” as Edoardo Saravelle at the Center for a New American Security wrote recently: Russia’s attempt to influence the US reaches far beyond attempting to influence the US presidential elections. “The pipeline is a naked Russian attempt to divide and conquer Europe. What makes the Kremlin so clever, and this effort so insidious, is that Gazprom has engineered an attractive business case for the project for a number of European gas importers,” writes Saravelle.

Due to the geo-political dimension of Nord Stream not only politicians and voters in the affected countries were interested in the Nord Stream development but also US politicians.

The Nord Stream effect

As German Chancellor 1998 to 2005, the social democratic leader Gerhard Schröder showed to begin with little liking for Boris Yeltsin’s Russia. That changed when Vladimir Putin, fluent in German after living there as a KGB agent, rose to power. One sign of Schröder’s strong ties to Russia was his enthusiasm for the Baltic gas pipeline and Nord Stream. One of Schröder’s last acts in office was to agree to a state guarantee of €1bn for part of the Nord Stream construction cost.

Only weeks after stepping down as Chancellor, Schröder accepted the Nord Stream offer to become head of the shareholder group of Nord Stream AG, a post he still holds. Not only Germans were shocked. Washington Post wrote an editorial on what the paper called Schröder’s “Sellout” – Democrat Congressman Tom Lantos, a holocaust survivor who died in 2008, chair of the House of Representatives foreign relations committee said that Schröder’s close ties to the Russian energy sector was “political prostitution.”

Equally, it shocked many Fins in 2008 when their social democratic Prime Minister 1995 to 2003 Paavo Lipponen became a Nord Stream consultant. A year later, Poland blocked Lipponen from being put forward as EU foreign policy chief because of his work for Nord Stream.

The new US sanctions against Russia enjoy a large bipartisan support in spite of Trump’s opposition. The new sanctions threaten to hit European companies working on the Nord Stream 2 joint venture with Russia, a major headache for the EU.

The far Right admiration for Putin

As social democrats and in spite of their ties to Putin’s Russia, both Schröder and Lipponen have been advocates of a strong and united Europe Union. But over the last decade or so, many far Right politicians in Europe and the US have shown great sympathy and even admiration for Putin.

Wholly ignoring the dismal state of the Russian economy under Putin and no matter his decidedly undemocratic and despotic tendencies many on the far Right seem to admire him as a strong leader. They have swallowed Putin’s own portrayal of himself, utterly ignoring that Putin’s iconography is unattached to reality.