Search Results

Iceland: the most offshorised country in the world?

What do Russia’s president Vladimir Putin and Iceland’s prime minister Sigmundur Davíð Gunnlaugsson have in common? Both have recently tried some pre-emptive damage-control measures before the material from a leak, administered by International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, ICIJ, is published. Gunnlaugsson’s wife has a BVI company as do or did minister of finance Bjarni Benediktsson and another minister. – While waiting for the ICIJ leak it’s worthwhile revising on the Icelandic offshorisation: Iceland is probably one of the most offshorised countries in the world.

Since his wife posted on Facebook March 15 that she owned a “company abroad” prime minister Sigmundur Davíð Gunnlaugsson has tried in various ways to brush off this whole affair of his link to an offshore company. As so often, when dignitaries are under pressure to inform the information given has proved to be less than informative.

Two things have been taken up by his critics: although members of parliament are required to register financial interests Gunnlaugsson had not seen it necessary to register this company since it was his wife’s and while Iceland was negotiating with creditors to the banks he did not mention that this wife holds claims in the banks.

This led to queries from a Rúv journalist to all parliamentarians as to offshore companies. Both Bjarni Benediktsson minister of finance and minister of justice Ólöf Nordal acknowledged such ownership. They have both mentioned that they had had questions regarding their ownership from an Icelandic journalist working with the ICIJ. Several other politicians or people with political ties now also acknowledge owning offshore companies but nothing as spectacular as the PM offshore link.

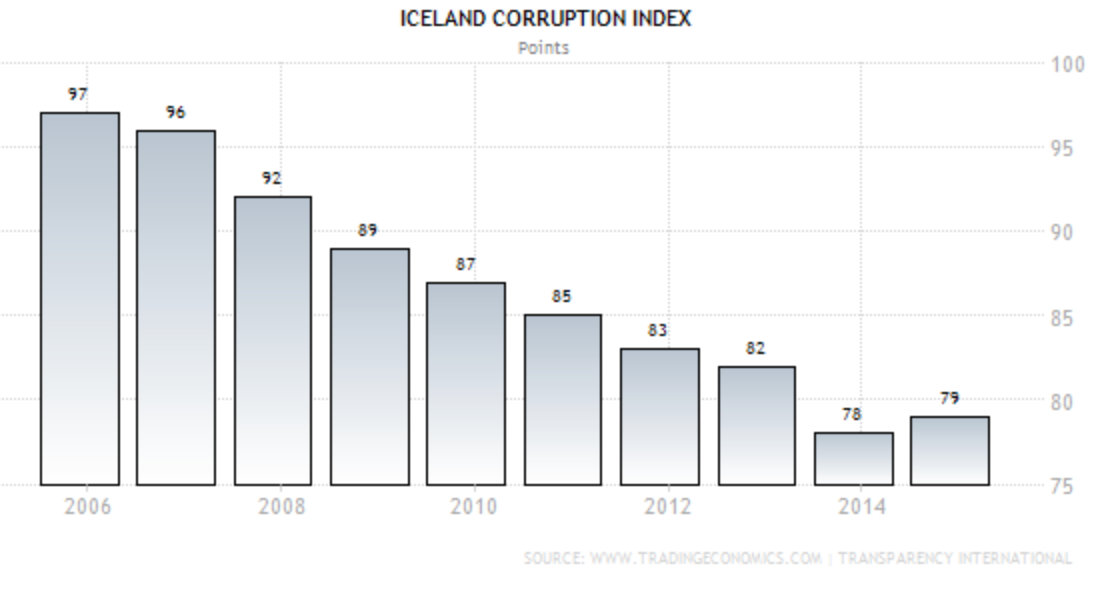

Since 2013 Group of States against Corruption, GRECO, have been reminding Iceland of its faulty measures against corruption, i.a. that interests of public officials are not transparent enough. This was latest underlined in GRECO’s fourth evaluation round, published March 23. In addition, foreign-owned companies are a particularly sore subject in a country where capital controls have for almost eight years prevented both individuals and companies from investing abroad.

Leaked material will be published later today by international media such as the Guardian, Süddeutsche Zeitung, DR, SVT and Rúv in collaboration with the ICIJ. All three offshore companies, which have now surfaced, were set up by Landsbanki Luxembourg. The context for the three new Icelandic-owned offshore companies is interesting: the Icelandic banks were extremely efficient in selling offshore solutions to their clients, also much less wealthy clients than foreign banks would have offered these services to.

Following the banking collapse in October 2008 I started investigating matters related to the Icelandic banks. What I found most surprising was how diligently the banks had been in selling offshore services. I believe it’s not too much to say that Iceland was the most offshorised country in the world because so many small business-owners were offered offshore companies. As often happens in Iceland things spread quickly. During the heady years up to 2008, a source said to me “you just weren’t anyone unless you owned an offshore company.”

Ca 250-300 individuals might have owned offshore companies

The easiest way to search was to use Luxembourg, the gate to most of the Icelandic offshore sphere, to search for companies. There is no official statistics regarding offshore companies but my guess is that perhaps 250-300 individuals owned offshore companies. Most of these people would own only one company except the wealthiest businessmen might have many to their name.

Among companies there were Baugur Group and others that had a veritable offshore galaxy connected to their activities. Certainly, the use of offshore companies is not an Icelandic invention but the Icelandic banks seem to have taken it further than in many other countries, resulting in utterly meaningless ownership of offshore companies by small investors who could perfectly well invest without owning such a company.

“Don’t be silly”

After the prime minister’s wife informed on her “company abroad” it quickly transpired that the company wasn’t only abroad but offshore, registered in the BVI. The debate in Iceland has been hefty and the truth has appeared only slowly.

At first, Gunnlaugsson claimed the company was entirely his wife’s affair, which made people wonder why he then chose to use his own spokesman, paid for by the public purse, to deal with questions. The Icelandic media was also quick to pull up sound-bites from the election campaign in 2009 where Gunnlaugsson pointed out that since his wife was wealthy he couldn’t be bought by anyone.

Apart from questions from the media, which have been sparsely answered, the PM chose to inform through chosen channels. Since the original Facebook message proved somewhat uninformative the couple has brought out the following: a short message on Gunnlaugsson’s own webpage, much in praise of his unselfish wife who had sacrificed possible wealth because of her husband’s political carrier; a letter from KPMG, to confirm that all due taxes have been paid; an interview in Fréttablaðið, owned by the wife of Jón Ásgeir Jóhannesson, of Baugur fame, at one time owner of a myriad of offshore companies, where the questions left something to be desired; an interview on a private radio station, also owned by Jóhannesson’s media company; a 12 page questions and answers, published on Gunnlaugsson’s webpage, informing i.a. on why the offshore company is called Wintris (thus this relevant fact that the name was not chosen by the wife but came with the “company-packet”) – on social media in Iceland this Q&A is widely called “the prime minister’s interview with himself.”

Gunnlaugsson has however been entirely unwilling to submit himself to being questioned by Rúv or any media known for independence. A few days after the story broke a Rúv journalist managed to track him down in the Alþingi’s parking basement where the prime minister had found an unusual way out of the building as the journalist was standing by the main door. When the journalist asked the PM what he wanted to say regarding Wintris Gunnlaugsson said laughing: “Látt’ekki svona” which might be translated as “Don’t be silly.”

The Wintris saga – so far

Pálsdóttir is independently wealthy, the daughter of a businessman who i.a. owned the Toyota dealership in Iceland. Following the sale of the dealership in 2005 Pálsdóttir got her share of the sale in 2007.

Here comes the first slight ambiguity. In his first response the PM says that when she acquired the assets, in 2007, the couple had lived in the UK “for a few years” intending to live abroad for a few more years, either in Denmark or in Britain. Strangely enough the prime minister has never been able to clarify completely where he lived 2005 until late 2008 when he showed up in Icelandic politics. These years have sometimes been referred to as Gunnlaugsson’s lost years and his academic achievements were for a while not quite clear.

What is clear is that he finished the Icelandic equivalent of A levels in 1995 and then graduated from the University of Iceland a decade later with a BS business degree and media studies. During that time he worked for some years at Rúv; a BS degree normally takes three years to finish if the student is studying full time.

According to his CV on the Alþingi website he was an exchange student at the Plekhanov University in Moscow, studied international relations and public affairs in Copenhagen and then economics and politics in Oxford during these three years. Icelandic media has tried, unsuccessfully, to get information from Oxford University as to what exactly Gunnlaugsson had studied; it seemed the student had asked the OU not to give any information on his time there. Also, according to his CV he worked part time for Rúv 2000 until 2007.

Whatever the exact timing of his whereabouts and studies the couple decided to keep the money abroad, meaning that the assets, which originated in Iceland, were moved abroad. This, at the time when Iceland was functionally part of the free flow of funds in the European Economic Area and in terms of access to funds in Iceland it shouldn’t have mattered where the couple lived.

In her FB message Pálsdóttir claimed she was under particular EEA tax scrutiny, something that proved to be a “misunderstanding” when the media inquired as to what exactly this meant. In her original message she also indicated that she was posting this because of rumours regarding her assets. Only later came the information the couple had received questions some days earlier from an ICIJ journalist regarding her offshore company.

Creditors and claims

Another drip of information brought out that Wintris did indeed own claims in the Icelandic banks, i.e. the PM’s wife had invested in bank bonds before the banks collapsed and now owned claims.

Gunnlaugsson has emphasised that Wintris is not his company. Another ambiguity is how exactly the ownership was separated. Pre-nuptials are not uncommon in Iceland but that doesn’t seem to have been their arrangement. The same counts for information that Wintris has always been declared to tax authorities, again somewhat ambiguous.

Before broadcasting a piece on Rúv on Friday regarding “Controlled Foreign Corporations,” CFC, I had asked the PM’s adviser and the KPMG-employee who wrote the letter if the tax filing in Iceland was done by using a CFC form, as is the only correct way of filing a company like Wintris. I did not get an answer. (In a blog post Gunnlaugsson has today expressed anger at my reporting.)

Since becoming a prime minister finding a solution for lifting capital controls, where the banks’ estates and their creditors were a significant part of the equation has been one of Gunnlaugsson’s major task. He claims he was not at all obliged to declare interest, given that his wife held claims in the banks. On the contrary, he claims it would have been an impossible situation had his wife’s interest been known. Some political opponents claim that Gunnlaugsson can’t simply set his own ethical standards and definition.

Gunnlaugsson’s wife is a client of Crédit Suisse, which following the collapse of the Icelandic banks took over private banking for some wealthy Icelandic clients. Crédit Suisse has at times invited its clients to meeting abroad. I have asked the PM’s adviser if Pálsdóttir has ever accepted such invitations but again, no answer has been forthcoming.

Pálsdóttir has claimed she instructed CS not to invest in any Icelandic asset. Questions from Icelandic media on the content of her CS portfolio have not been answered.

Principles, not persons

Much of the debate in Iceland regarding Wintris so far has centred on if Gunnlaugsson profited, via Wintris, from decisions taken regarding the plan to lift capital controls and its effect on creditors.

This angle is, from my point of view, rather futile. Although Gunnlaugsson has in the Wintris debate repeatedly emphasised his own valiant action against the creditors his version can be contested. It was clear already by 2012 that what needed to be done regarding the estates was to write down the ISK assets; there was not enough foreign currency to pay the ISK in the estates in FX.

Creditors were ready to negotiate by late 2012 but given the fact that the left government was greatly weakened by internal fights it didn’t have the political strength and mandate to enter into negotiations. It was clear to all involved that this would have to wait until after the elections.

During the election campaign Gunnlaugsson talked about the billions that would fall in the lap of the Icelandic state; billions that would be used to write down private loans and for other good things. It then took the government two years to find the solution. My understanding was during that time, as I repeatedly mentioned on Icelog, that the two government leaders disagreed: Benediktsson wanted to find the least risky solution in unison with creditors, Gunnlaugsson wanted to play hardball, ignoring the legal risk Benediktsson repeatedly referred to. The two leaders have challenged his course of events.

Ultimately, this affair is not about people but principles – if leading politicians should be connected to offshore companies at the same time that Icelandic authorities have joined international effort to fight tax havens and secrecy jurisdiction. It is after all perfectly possible to invest, at home or abroad, without owning an offshore vehicle.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

The prime minister’s wife and her Tortola company – updated

Since 28 November 2008, Icelanders, both companies and individuals, have been locked inside capital controls. Those who owned assets outside of Iceland before that date were allowed to keep them abroad. Now it turns out that the wife of prime minister Sigmundur Davíð Gunnlaugsson, Anna Sigurlaug Pálsdóttir, was one of the lucky ones with assets outside of capital controls, free to invest according to her choice.

The news came out Tuesday evening when Pálsdóttir announced on Facebook that she hoped to put all rumours to rest by acknowledging the existence of a company of hers, “registered abroad” but administered by a bank in London. This company had been set up some years ago as an investment vehicle around her inheritance.

Only after request from the media was it confirmed that this company, Wintris Inc., is registered in the British Virgin Islands. In Iceland, these companies go by the name of “Tortola companies” and have a very unflattering tone since so many of the viking raiders, the largest shareholders in the Icelandic banks and their fellow travellers, hugely enriched by their close connections with the banks, also had BVI companies.

In her Facebook message Pálsdóttir said that the company had been set up in 2007 at a time when the couple did not know whether they would be living in Britain or Denmark, which meant that having the company abroad would have been convenient.

This explanation does however bypass the fact that at the time the Icelandic banks were operating abroad and there was no hindrance to move capital in and out of the country. Living in Britain or in Denmark would have made no difference to the availability of the funds had they been kept in Iceland.

Also, the sale that released the funds was made in Iceland, meaning that the funds were most likely moved abroad for other reasons than availability abroad. The wife and her husband’s spokesman strenuously deny that this arrangement had any tax purposes. It had all been above board, all reported to the Icelandic Inland Revenue.

The question remaining unanswered is why these funds have not been moved back to Iceland, not least after her husband became party leader in January 2009 or at the latest when he became prime minister in spring 2013. At the time, it was clear that one of his government’s main task would be to lift the capital control, as the prime minister had indeed repeatedly promised to do speedily when in office.

That task in not yet completed but will most likely be very soon; the governor of the Central Bank Már Guðmundsson said Wednesday that an announcement on the offshore króna – the last major part of the capital controls still unsolved – could come as soon as Thursday 17 March.

The reason for Pálsdóttir’s sudden declaration seems to stem less from a certain urge for transparency and more because a journalist had been asking about the existence of a BVI company owned by Pálsdóttir. However, Icelanders will be asking themselves how fit and proper it was that a prime minister of a country locked in by capital controls was wholly unencumbered by these same controls as the family assets were safely beyond the controls.

Update: Turns out the prime minister’s wife not only owns a Tortola company but she holds claims in the collapsed banks, ca ISK500m or €3.5m, making her a creditor in the banks. Since her husband didn’t hold back earlier on, before the government was actually negotiating a solution to the capital controls, to call the creditors “vultures” his political opponents haven’t held back in pointing out that being a creditor would make his wife, seen from his point of view, a vulture. – And which bank does the couple choose? Credit Suisse, which has quite a number of Icelandic clients through ties established before the banking collapse in 2008.

Further: Upcoming on Icelog is a blog on the latest debate in Iceland re Wintris, other ministers who own offshore companies and more on Icelandic offshorisation. This will be a summary of these matters before Rúv and other media will start publishing reports based on leaked material in cooperation with International Consortium of Investigative Journalists this coming Sunday at 18GMT. This leak contains wealth of material regarding Iceland, via Landsbanki Luxembourg as indicated on news in Iceland so far.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Does Iceland have a better legal code to deal with dodgy banking?

“No” is the short answer. The Icelandic penal code on i.a. breach of fiduciary duty and market manipulation is similar to law in Western countries. The difference in Iceland was the swift awareness in autumn 2008 that there might be something worth investigating, later supported by setting up an Office of a Special Prosecutor, Special Investigating Commission and strengthening the financial supervision. Also, the Special Prosecutor quickly realised that behind the invariably complicated web of shell companies and transactions stories of fraud are in reality quite simple and follow the same patterns over and over again. This is why bankers and shareholders have been successfully prosecuted in Iceland – not because Iceland has better penal code.

“How come that Iceland is successfully prosecuting bankers, getting them sentenced to lengthy prison terms when no one else is doing it?” This is a question I keep being asked. The short answer is the one above but there is also a longer one.

Soon after Icelanders got used to the fact that the three large Icelandic banks had collapsed, in early October 2008, the country and the media was rife with rumours that something not entirely normal, not entirely legal, had been going on in the banks. Some tried to explain alleged irregularities by the unavoidable panic; that well, perhaps the bankers had in some cases overstepped the legal borderline, strayed into grey territories, as they fought to keep the banks as going concerns.

The Icelandic parliament, Alþingi, took two measures in December 2008 to clarify the collapse: it set up an investigative commission, The Special Investigative Commission, SIC, into the banking collapse – and it set up an Office of a Special Prosecutor, OSP.

The SIC already came across a number of cases it could not quite align with normal banking practices. These cases were outlined in its thorough report in April 2012 and it also presented its findings to the OSP. At the same time the financial supervisor, FME, was diligently reviewing the operations of the banks prior to the collapse. This meant that the OSP i.a. got input from these two institutions.

The Icelandic lesson from dealing with fraud related to the banks’ operations up to the banking collapse just proved the old saying: where there is a will there is a way.

A meagre and humble start

The beginnings of the OSP were not promising. First, no one applied for the job. Then a small-town sheriff was asked to apply and that is how Ólafur Hauksson, from Akranes across the bay from Reykjavík, got the job. This is a story often told before: Hauksson had never seen anything more serious than speed-driving, drunk driving, moonlighting, domestic violence, break-ins and drunken brawl, the average criminality in an Icelandic small town.

But Hauksson proved that give a person the occasion to shine and he/she very well might. He got funds to hire staff, three prosecutors were hired. Slowly slowly, the charges emerged. Slowly slowly, bankers started to pack to go on an unexpected trip, sent by the Supreme Court, to Snæfellsnes, the beautiful peninsula visible from Reykjavík, to an old farm, Kvíabryggja, a prison for non-violent prisoners.

Last year, following a system change, the OSP was moved into a bigger structure, the Office of County Prosecutor. This time, several people applied to lead the new institution. Hauksson was among the applicants and landed the job.

Digging out the simple truth from entangled webs of emails, shell companies and transactions

The main stories emerging from the collapse cases so far have revolved around market manipulation and breach of fiduciary duty. The real lesson here is the same as everywhere else: these cases look complicated, there are mountains of documents to read, often complicated web of shell companies and offshore companies, money floating around. Interestingly, phone tapping has been used successfully and there are also recordings from the old banks.

However, as in all such cases the underlying stories tend to be simple: the ways to commit a crime are not myriad. Think Enron: looks complicated, with all of the above – at the bottom, a simple story how losses were hidden from shareholders. Another entangled web is the Savings & Loan scandals in the US in the 1980s, nota bene where cases were really investigated and people sentenced to prison.

And these things do not happen by themselves. In every case it takes more than one to do all the necessary things. A prosecutor then decides whose deeds are grave enough to prosecute, who bears the responsibility etc.

Considering how little has been done i.a. in the UK to investigate the banks’ operations leading to the autumn 2008 banking collapse there and considering the screamingly obvious inactions by authorities in Luxembourg regarding banks – all the worst cases in Iceland have ties to the banks’ operations in Luxembourg – it is ironic that the OSP would have been a lot less successful were it not for a fruitful cooperation with these two countries. Authorities in both countries have carried out house searches and assisted in finding and identifying documents relevant for the OSP’s work. Yes, that is hugely ironic…

Market manipulation: burying shares like drug dealers with too much cash

Icelandic cases of market manipulation where bankers have been sentenced have mainly been carried out in two ways: through the banks’ own trading and by parking the banks’ shares into shell companies, invariably owned by clients with some particularly cosy ties to the banks and/or the banks’ shareholders.

Although Landsbanki and Kaupthing, Glitnir to a much lesser extent, were successfully running high interest rates internet accounts, to fund their operations (Landsbanki and the ill-fated Icesave), all three banks relied on selling bonds on international markets. This funding kept the banks going like mills with water. When funding dried up in summer 2007 it was clear that the banks would come to a grinding halt.

That is also what foreign banks sensed, quickly starting to call in loans and, with sinking asset prices, making margin calls on the big Icelandic businesses, i.e. the banks’ main shareholders and their closest partners. Since Icelandic bank shares were the collaterals in most of these loans (after all, the banks had lent the large shareholders money to buy their shares, another aspect that made Icelandic banks weak), it was clear that the markets would be flooded with Icelandic bank shares if the margin calls went through.

Faced with this the Icelandic banks decided to increase the lending to their largest clients – yes, all of them large and the largest shareholders in the banks – in order to prevent this flooding. The feeling when reading the court rulings in these cases is that the banks were like drug dealers with more cash than they can stash, needing to bury it etc.; i.e. the shares were buried in various companies and these transactions were funded by the banks.

Lending on contracts with no provisions to hinder possible losses

Breach of fiduciary duty has figured prominently in banking collapse cases leading to imprisonment. These cases all revolve in some way around lending where the bank carries all the risk, where eventual losses, were they to arise, would always fall on the bank, i.e. losses were foreseeable.

It seems to me that there are some Irish cases very similar to the Icelandic ones of foreseeable losses, i.e. the management didn’t seem to have the interest of the banks and their shareholders at heart but assisting individual clients beyond rhyme and reason.

These Icelandic loan agreements were often only agreed on by the banks’ managers, i.e. outside of regular processes, without the knowledge of credit committees etc. There would then be lower-placed trusted lieutenants who organised the lending. In some cases they have also been charged and sentenced, in some cases not.

Thus, the banks lend in such a way, apparently knowingly, that would the borrower not be able to pay, it would lead to the bank losing money. Here it is important to keep in mind that these banks were public companies with thousands of shareholders – Kaupthing had well over thirty thousand shareholders – losing money on bad lending.

“No society can tolerate that certain parts of it are beyond law and justice” – well, some can…

From reading the SIC report it is clear that some cases have been prosecuted, others not. There was too much of this going on but yes, the managers and the top tier, in some cases also shareholders, have been targeted by the OSP.

It is important to keep in mind that bankers in Iceland have not been sentenced for stupid or unwise decisions but for actions which the Supreme Court has then ruled were criminal actions.

When I talked to Hauksson following the conviction in the so-called al Thani case, in February 2015, he pointed out that the Supreme Court’s decisions showed “that it is possible to bring complicated financial cases to court and get conviction. Building up the expertise has been a long process but the ruling today demonstrates that setting up an office, which didn’t exist earlier, was fully justified. No society can tolerate that certain parts of it are beyond law and justice.”

For some reason, countries like the US and the UK, with old and esteemed legal traditions have in many cases decided to fine rather than prosecute for financial crimes, thereby showing the opposite of the Icelandic examples show – the US and the UK have indeed at times shown that yes, certain parts of society are indeed beyond law and justice. That has sadly been the UK and the US lessons of the financial calamities of 2008.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Ireland and Iceland – when cosiness kills

The fate of the Irish and the Icelandic banks are intertwined in time: as the Irish government decided on a blanket guarantee for the Irish banks, the Icelandic government was trying, in vain, to save the Icelandic banks. In spite of the guarantee six Irish banks failed in the coming months; the government bailed them out. The Icelandic banks failed over a few days. Within two months the Icelandic parliament had decided to set up an independent investigative committee – it took the Irish government almost seven years to set up a political committee, severely restricted in terms of what it could investigate and given a very limited time. The Irish report now published is better than nothing but far from the extensive overview given in Iceland: it lacks the overview of favoured clients and the favours they enjoyed.

A small country with a fast-growing banking sector run by managers dreaming of moving into the international league of big banks. To accelerate balance sheet growth the banks found businessmen with a risk appetite to match the bankers’ and bestowed them with favourable loans. Lethargic regulators watched, politicians cheered, nourishing the ego of a small nation wanting to make its mark on the world. – This was Iceland of the Viking raiders and Ireland at the time of the Celtic tiger, from the late 1990s, until the Vikings lost their helmets and the tiger its claws in autumn 2008.

In December 2008, eleven weeks after the Icelandic banking collapse, the Icelandic parliament, Alþingi, set up an independent investigative committee, The Special Investigative Commission, SIC, to investigate and clarify the banking collapse. Its three members were its chairman Supreme Court justice Páll Hreinsson, Alþingi’s Ombudsman Tryggvi Gunnarsson and lecturer in economics at Yale Sigríður Benediktsdóttir. Overseeing the work of around thirty experts, the SIC published its report on 12 April 2010: on 2400 pages (with more material online; only a small part of the report is in English) the SIC outlined why and how the banks had failed.

In November 2014, over six years after the Irish bank guarantee, the Irish Parliament, Oireachtas, set up The Committee of Inquiry into the Banking Crisis, or the Banking Inquiry, with eleven members from both houses of the Oireachtas; its chairman was Labour Party member Ciarán Lynch. The purpose of the Committee was to inquire into the reasons for the banking crisis. Its report was published 27 January 2016.

Both the Irish and the Icelandic reports make valid recommendations. It does however make a great difference if such recommendations are put forward 1 ½ years after the cataclysmic events – or – more than seven years later.

The Irish legal restraints, the Icelandic free reins and prosecutions

As Ciarán Lynch writes in his foreword to the Irish report: “As the Celtic Tiger fell, our confidence and belief in ourselves as a nation was dealt a blow and our international reputation was damaged.” The same happened in Iceland, confidence was dealt a blow and the country’s international reputation damaged. If anything can restore trust in politicians it is undiscriminating investigations and transparency.

In one aspect, the Irish Banking Inquiry differed fundamentally from the Icelandic one: the Irish was legally restrained from naming names. Consequently, the Irish report contains only general information on lending, exposure etc., not information on the individuals behind the abnormally high exposures.

This is unfortunate because in both countries, the high-risk banking was centred on a small group of individuals. In Ireland these were mostly property developers and some well-known businessmen; in Iceland the favoured clients were the banks’ largest shareholders, a somewhat unique and unflattering aspect that puts Iceland in league with countries like Mexico, Russia, Kazakhstan and Moldova.

The SIC had no such restraints but could access the banks’ information on the largest clients, i.e. the favoured clients. The report maps the loans and businesses of the banks’ largest shareholders and their close business partners, also some foreign clients. Consequently, the SIC report made it a public information that the largest borrower was Robert Tchenguiz, owed €2.2bn, second was Jón Ásgeir Jóhannesson, famous for his extensive UK retail investments, with €1.6bn. Björgólfur Thor Björgólfsson, Landsbanki’s largest shareholder (with his now bankrupt-father) owed €865m. These were loans issued by the banks in Iceland; with loans from the banks’ foreign operations these numbers would be substantially higher.

The SIC report also exposes how the banks had in many cases breached rules on individual exposures and then actively hidden it from the regulators and shareholders.

Apart from reacting quickly to set up an investigative commission, Alþingi passed a Bill in December 2008 to set up an Office of a Special Prosecutor, OSP, which came to investigate and prosecute bankers and businessmen. So far, 21 have been sentenced to prison and a number of cases are still pending. The OSP is now part of a permanent structure to investigate financial crimes. Prosecutions have given a further insight into the banking during the boom years, i.a. exposing fraudulent lending, breach of fiduciary duty and market manipulation.

Those prosecuted by the OSP have not been sentenced for wrong or unwise decisions but for criminal behaviour. Some of these cases, at least on the surface, bear close similarities to things going on in the Irish banks, i.a. in lending which unavoidably would lead to losses since the banks were light on collaterals. Icelandic laws do differ substantially from laws in other Western countries – but in Iceland there was the will and courage to explore these practices.

A very brief overview of Ireland and Iceland in autumn 2008

The year 2008 brought increasing worries of the soundness of an over-extended banking sector both in Ireland and Iceland

In Iceland, the board of Glitnir, the smallest of the three largest Icelandic banks, was the first to ask for a meeting with the Icelandic Central Bank, CBI: on September 25 2008 the governors of the CBI learned that the bank would not be able to meet its obligations in the coming weeks. Over the following weekend, the CBI and the government decided to save the bank by taking over 75% of its shares. This was clear early Monday morning September 29, just as the Irish government was furiously debating and preparing a two year blanket guarantee for six Irish banks.

According to the Irish report the Irish government decided solo on the guarantee; the European Central Bank, ECB had made it clear that each country was responsible for its own banks but no bank should fail. Yet, ECB’s views do not seem to have been foremost in the mind of Irish ministers struggling to find a solution September 29 to 30.

In Ireland, the blanket guarantee issued in the early hours of 30 September, valid from 1am 29 September, had been discussed on and off for some time; it was not an idea that arose on the spur of the moment. But in those last days of September 2008 a decision could no longer be postponed: Anglo and INBS had run out of liquidity. The choice was either a guarantee or nationalising the troubled banks.

The Irish guarantee gave food for thought in Iceland; it was briefly outlined for discussion 2 October 2008 as one possible option but apparently not pursued further.

It only took around 48 hours for the CBI and the government to realise that Glitnir’s affairs were a mess and the bank could not be saved. The following Monday, October 6, it was finally clear that the game was over: since the government could not save Glitnir, the smallest bank, it could evidently not save the two larger banks. An Emergency Bill was passed to have a legal framework in place. By October 9 2008 all three banks had failed.

In the UK, where all the Icelandic banks had operated, the government in panic over the state of the British banking system feared Landsbanki, which by then had around £4.2bn on its Icesave accounts, was moving funds out of the country. On 8 October the UK government slammed a Freezing Order on Landsbanki, using a legislation with the word “terrorism” in its title. A confusion ensued whether the Order referred only to Landsbanki or all things Icelandic. It took weeks and months to entangle this, adding to other woes Iceland faced.

The Icelandic quick blow, the Irish lingering stab

With the banks and the financial system in ruins Iceland sought help with the IMF and by 24 October had negotiated a loan of $2.1bn, now repaid. Iceland more or less followed IMF guidelines and made full use of the Fund’s expertise. Iceland was back to growth by mid 2011, 2 ½ years after the collapse (see here my take on the Icelandic recovery).

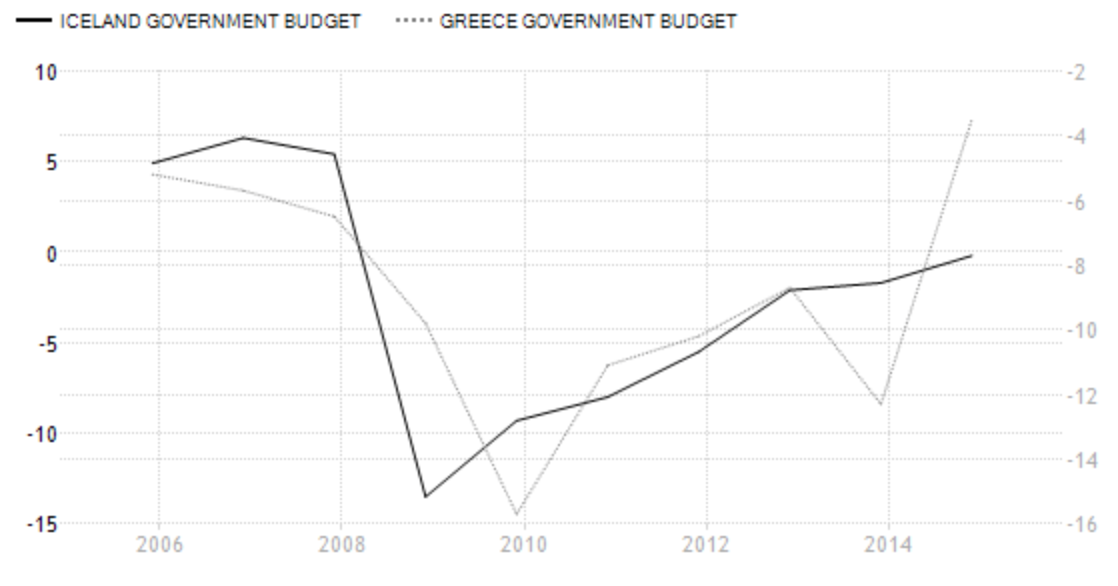

The guarantee didn’t save the Irish banks but only extended their lives for some months. Already by January 2009, the government had to step in to save the first bank. In the following weeks and months there were five more bail-outs, i.a. of all the banks mentioned in the guarantee. As the guarantee expired 28 September 2010 the Irish state had over-extended itself in saving six banks and in December a Troika bailout had been negotiated. – Ireland was back to growth in the last quarter of 2014, after two dips from 2008.

The ECB – IMF wrestle that the ECB won

There have been stories of the role of the ECB and possible burden sharing with bondholders, which could have been the solution when the two year guarantee was about to expire. The Irish report spells out what happened: it was the ECB against the IMF and the ECB won, also because the Irish government understood that both the US and the whole of the G7 sided with the ECB.

When discussing the Troika programme in October and November 2010 both the Irish government and the IMF mission were in favour of imposing losses on senior bondholders and the legal issues had been worked out. As Ajai Chopra then deputy director at the IMF informed the Inquiry the IMF staff was of the view that the markets would both have anticipated and been able to absorb ensuing losses “and even if they were not able to absorb it, there were mechanisms to help address that contagion… Recent academic research confirms the view that spillover risks were exaggerated.”

This view ran against the view at the commanding heights of the ECB: in November 2010 ECB governor Jean-Claude Trichet made it clear in a letter that if the government insisted on imposing losses on bondholders there would be no Troika programme. Other powers agreed with the ECB: Ireland’s minister of finance Brian Lenihan knew US Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner was dead against the burden sharing. Lenihan also told governor of the Central Bank of Ireland Patrick Honohan that the leaders of the G7 countries agreed with Geithner. “I can’t go against the whole of the G7,” Lenihan said to Honohan who was of the view Lenihan saw the burden sharing as “politically, internationally politically inconceivable…”

After a new Irish government came to power 9 March 2011 the possibility of a burden sharing was again explored, especially regarding Anglo and INBS, which were no longer going concerns, but had been placed under the Irish Bank Resolution Corporation, IBRC. Noonan stated his position in a phone call to ECB’s governor Jean-Claude Trichet, who according to Noonan “…sounded irate but maybe he wasn’t irate but that’s the way he sounded and he said if you do that, a bomb will go off and it won’t be here, it’ll be in Dublin.”

When asked during a visit to Ireland in spring 2015, Trichet only referred to letters sent by the ECB, nothing more. In a letter in March 2011, Trichet threatened to withdraw Emergency Liquidity Assistance, ELA if the government went ahead with imposing a hair-cut on bondholders.

As in November 2010, the March 2011 attempt by the new Government to impose losses on bondholders, was unsuccessful. “Once again, the intervention of the ECB appears to have been critical.”

The ECB prevailed, with drastic consequences for Ireland: “The ECB position in November 2010 and March 2011 on imposing losses on senior bondholders, contributed to the inappropriate placing of significant banking debts on the Irish citizen.”

It left the Irish with a bailout cost much higher than would have been necessary. Certainly a tragic outcome for Ireland.

The pattern of collective madness

Both the Icelandic and Irish collapse could be summarised as having happened because so many got it wrong, ignored the clear warning signs and made the wrong decisions.

Ciarán Lynch sums up the Irish crisis as “a systemic misjudgement of risk; that those in significant roles in Ireland, whether public or private, in their own way got it wrong; that it was a misjudgement of risk on such a scale that it lead to the greatest financial failure and ultimate crash in the history of the State.” – Further, the banking crisis led to a fiscal crisis. “These were directly caused by four key failures; in banking, regulatory, government and Europe” after which “turning to the Troika became the only solution.”

The Irish banking crisis was caused by the banks pursuing “risky business practices, either to protect their market share or to grow their business and profits. Exposures resulting from poor lending to the property sector not only threatened the viability of individual financial institutions but also the financial system itself.”

Regulators were aware of this, yet did not respond to the systemic risk but adopted “a principles-based “light touch” and non-intrusive approach to regulation. The Central Bank, the leading guardian of the financial stability of the state, underestimated the risks to the Irish financial system.”

In spite of a period of unprecedented growth in tax revenues the government’s fiscal policy was based on long-term expenditure commitments “made on the back of unsustainable cyclical, construction and transaction-based revenue. When the banking crisis hit and the property market crashed, the gulf between sustainable income and expenditure commitments was exposed and the result was a hard landing laying bare a significant structural deficit in the State finances.

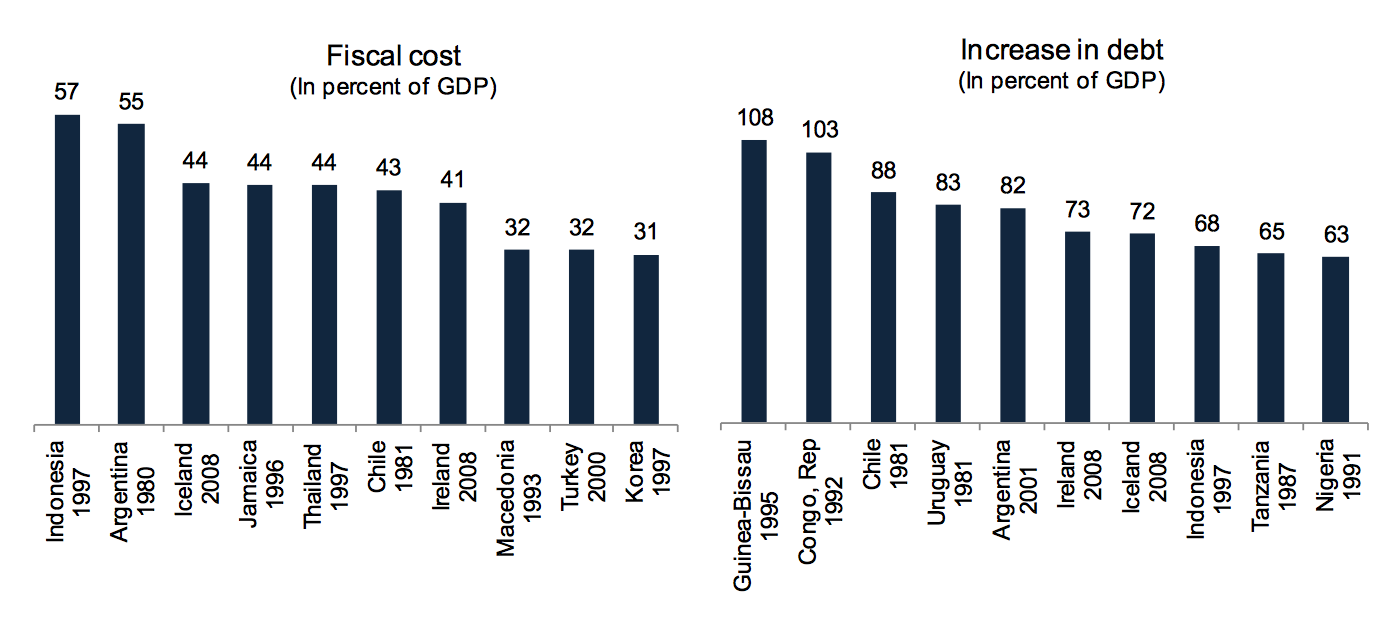

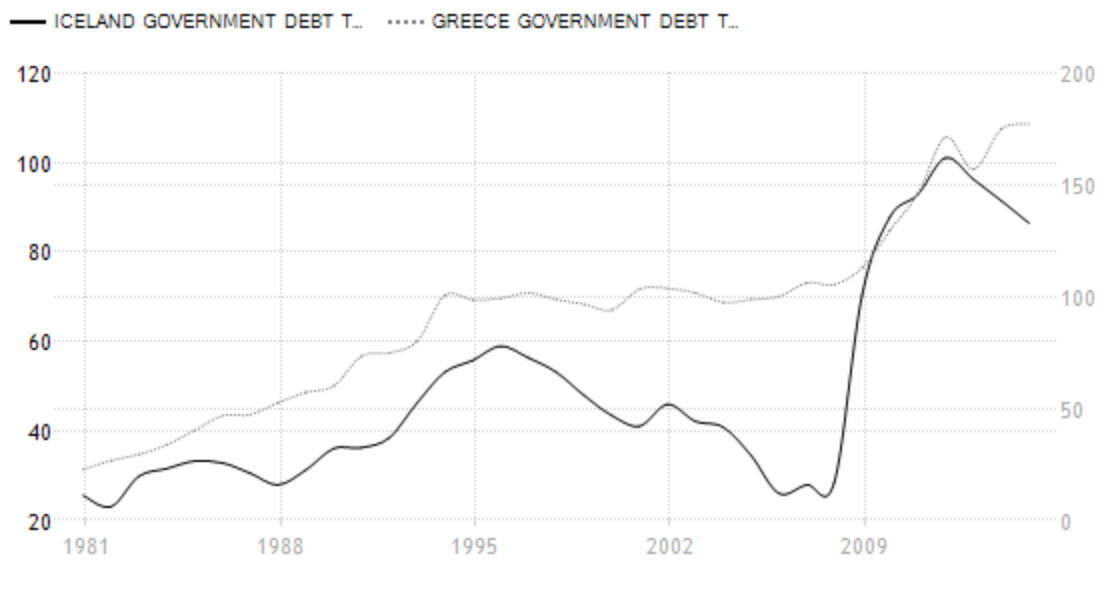

The Icelandic crisis also started as a banking crisis, with the banks collapsing. Though bondholders in the large banks were not bailed out (but they were in three smaller banks and an insurance company) significant cost accrued to the state: the net fiscal cost of supporting and restructuring the banks is 19.2% of GDP, according to the IMF. Iceland did indeed suffer at fiscal crisis: it had to be bailed out by an IMF loan.

In summarising its finding the SIC report states that the explanations of the collapse of the three largest banks can “first and foremost to be found in their rapid expansion and their subsequent size when they tumbled in October 2008. Their balance sheets and lending portfolios expanded beyond the capacity of their own infrastructure. Management and supervision did not keep up with the rapid expansion of lending… The banks’ rapid lending growth had the effect that their asset portfolios became fraught with high risk.” The high incentives for growth were found in the banks’ incentive schemes and “the high leverage of the major owners,” in addition to the availability of funds on international markets.

All of this should have been evident to the supervisory authorities, giving cause for concern. “However, it is evident that the Financial Supervisory Authority FME… did not grow in the same proportion as the banks, and its practices did not keep up with the rapid changes in the banks’ practices.”

As in Ireland, Icelandic politicians lowered taxes during an economic expansion, contrary to expert advise “even against the better judgement of policy makers who made the decision. This decision was highly reproachable.” The CBI’s calls for budget restraint were ignored but also the CBI made mistakes, such as failing to raise interest rates in tandem with the state of the economy and in lending to the banks in 2008, resulting in a loss for the CBI of 18% of GDP.

In Ireland, politicians and authorities had, without any test or challenge, adopted a ‘soft landing’ theory, as indeed had many international monitoring agencies. “The failure to take action to slow house price and credit growth must also be attributed to those who supported and advocated this fatally flawed theory.”

Though less clearly formulated, there was a lot of wishful thinking in Iceland. However, as pointed out in the SIC reports, “flawed fiscal and monetary management … exacerbated the imbalance in the economy. They were a factor in forcing an adjustment of the imbalances, which ended with a very hard landing.”

The lethal debts: commercial property in Ireland, holding companies in Iceland

Though banks thrive on debt the wrong type of debt and monoline lending can be lethal when circumstances change and the debt goes from risky to hopeless. The practices of the Irish and the Icelandic banks give some examples of how risky turns lethal.

High exposure to property was claimed to be the main risk on the books of the Irish banks. “Between 2004 and 2008 almost €8 billion worth of commercial investment property was sold in Ireland. 2006 was the peak year for investment volumes, with €3.6 billion traded in 12 months. For context, this compares to the previous record of €1.2 billion in 2005 and an average of €768 million per annum between 2001 and 2004.”

This number is however too low, according to the report, as it only refers to domestic lending to commercial property. The Irish banks funded considerable Irish investments abroad, mostly in the UK and the rest of Europe. Thus, the size of commercial property lending was larger than the domestic market indicates.

Fintan Drury, a former Non-Executive director of Anglo Irish Bank, admitted that Anglo had been “a monoline bank … somewhere between 80% and 90%” of Anglo’s loan book was related to property investment” – or specifically the high exposure to commercial property which turned out to be the most severe risk factor in the Irish banks, later causing the largest losses.

The Irish National Asset Management Agency, NAMA, was set up in 2009 in order to manage and recove bad assets from the banks the government recapitalised. As the Irish report points out the transfer of loans, from the banks saved by the state, exposed the losses. The total par value of loans to commercial property was €74.4bn for which NAMA paid €31.7bn. For the loans remaining on the banks’ balance sheets, the impairment rate of commercial real estate was 56.9%, “over three times that of residential mortgages and over twice the average of all impaired loans.”

Dan McLaughlin former Chief Economist, Bank of Ireland is of the view that lending to commercial property led to the banks needing assistance. In total, commercial property prices dropped by 67% (apparently in 2008-2009 but that is not quite clear from the context) whereas commercial property in the UK fell by 35% and in the US by 40%.

This concentration of a single asset class was seen as a major weakness in September 2008. Merrill Lynch acted as an adviser to the Irish government. During these febrile hours as the guarantee was being prepared the head of European Financial Institutions at Merrill Lynch, Henrietta Baldock wrote in an email that clearly “certain lowly rated monoline banking models around the world, where there is concentration on a single asset class (such as commercial property) are likely to be unviable as wholesale markets stay closed to them.”

In Iceland, the killer lending was to holding companies. At first sight they seemed to be in diverse sectors such as retail, food, pharmaceuticals, banking, mobile telephony and property. However, these apparently diverse companies were highly inter-linked through cross-ownership where every snippet of asset was collateralised.

In addition, both Icelandic bankers and businessmen knew during the boom that foreign banks tended to see various Icelandic enterprises, whether banks or something else, as just one big bundle: a risk to one bank or one enterprise was a risk to them all. Iceland was like one company, with a GDP as a big but not gigantic international company.

Cross-borrowing and high exposures to small groups

Both Irish and Icelandic banks tied their fortunes to a small group of businessmen. Over time, this changed the power balance between the banks and their clients. The clients were not beholden to the banks but the banks to the clients.

The amount of loans to single borrowers came as a surprise to some when the Irish lending was scrutinised. Michael Somers, former Chief Executive, NTMA, said he “was flabbergasted when I saw the size of the loans … which were advanced by the Irish banking system to individuals. I mean, they ran to billions… some individual had loans from the banking system equivalent to 3% of our GNP, which I thought was absolutely staggering.” – It turned out that the “…top ten borrowers had loans of €17.7bn with the six guaranteed banks and that was before any additional borrowings they had in Ulster Bank or Bank of Scotland Ireland.”

The above indicates one of the problems: the largest Irish borrowers most often borrowed not only from one bank for each project but from several banks. Yet, the banks apparently made no attempt to have a holistic overview of their largest clients’ cross borrowing. This created further risk for the Irish banks that directed most of their risky lending to only a small group of clients. – According to Frank Daly chairman of NAMA the impression was that the banks had been “acting “almost in isolation” from one another” showing little interest in clients’ exposure to other banks.

A case in point is INBS, one of the six banks forced to turn to the state for cover. It had “a concentration of loans in the higher risk development sector, a concentration of loans in the higher loan-to-value bands, a concentration in its customer base – the top 30 commercial customers, for example, accounted for 53% of the total commercial loan book – and a concentration in sources of supplemental arrangement fees, representing 48% of profit in 2006. Indeed, 73% of those fees came from just nine customers.” – The board was indeed aware of this but it did not feel it gave cause for concern.

Fintan Drury, former non-executive director of Anglo Irish Bank, was aware that “a relatively small number of clients who had quite a significant percentage of … of the lending, yes. Was I concerned about that? Not particularly.”

The Banking Inquiry “Committee is of the view that the banks had a prudential duty to themselves to inquire, challenge and assess hidden risks arising from multi-bank borrowing by major clients.”

As mentioned earlier, the unique aspect of the Icelandic banking was the fact that the largest shareholders and their business partners were also the largest borrowers. The SIC report drew attention to warnings from Bank of International Settlement, BIS, that banks may evaluate a borrower’s credit value differently if this person is either a key investor or a board member. In countries where supervision and legal protection for small shareholders is lacking abnormal lending to bank owners is often the case, a hugely worrying factor for Iceland.

And here is the unique aspect of the Icelandic banking practices: “The largest owners of all the big banks had abnormally easy access to credit at the banks they owned, apparently in their capacity as owners. The examination conducted by the SIC of the largest exposures at Glitnir, Kaupthing Bank, Landsbanki and Straumur-Burðarás revealed that in all of the banks, their principal owners were among the largest borrowers.” – The SIC concluded that the fact the largest borrowers in all the banks happened to be their owners “indicated a systematic pattern, i.e. that the banks’ owners had an abnormal access to funds in their own banks.”

These were i.a. Icelandic businessmen well known in the UK such as the two mentioned earlier – Björgólfur Thor Björgólfsson who owns the investment fund Novator, still operating in the UK and Jón Ásgeir Jóhannesson – in addition to the brothers Ágúst and Lýður Guðmundsson who still control Bakkavör, a major supplier to UK supermarkets.

In addition to the risk stemming from the concentration of loans to the same largest shareholders and clusters of companies connected to them and their business partners within each bank the fact that these clusters were highly leveraged in the other banks exacerbated the risk.

Signs of favour: Irish roll-ups and Icelandic bullet loans

Interestingly, both in the Irish and the Icelandic banks the favoured clients got similar types of favourable loans. In Ireland it is the “roll-ups,” in Iceland “bullet loans.” – This strongly indicates that in addition to high exposure and high concentration, financial supervisors should keep an eye on the types of loans issued.

Rolled-up loans transferred to NAMA amounted to €9bn, out of a total of the €74.4bn transferred. The Irish roll-up “refers to the practice whereby interest on a loan is added on to the outstanding loan balance (“rolled-up”) where it effectively becomes part of the loan capital outstanding and accrues further interest. “Rolling-up” interest would generally allow a borrower not to repay interest as it falls due, but this would be done without placing the loan in default.”

The roll-up offered was either an “interest repayment holiday” agreed in advance as the loan was issued or it was a later offer when the borrower had been unable to meet the agreed interest repayment; a sign of the bank’s lenience or its loss of control over the borrower.

According to NAMA’s evidence the existence of these interest roll-ups did not come as a surprise. The surprise was to discover how extensive they were, especially finding that “new loans were being created to take account of the rolled up interest.”

Added to a narrow group of borrowers, their narrow field of investments and high exposures related to these few individuals with monoline investments, roll-ups are a clear sign of concern. At the Banking Inquiry, Gary McGann, Independent Non-Executive Director at Anglo, was asked if with regards to the roll-up “with such a narrow field of individuals did the bank consider that in terms of risk.” His answer was: “Not specifically.”

The Icelandic bullet loans would normally be paid up in one instalment at maturity with the interest rates paid at regular intervals during the life-time of the loan. There were however many examples, especially as the credit crunch hit the leveraged borrowers, of the loan being “rolled up” and everything paid at maturity, both the loan and interest rates. At this point, paying one bullet-loan with a new one became common.

In theory, issuing bullet loans can make sense. However, by extending bullet loans losses can be hidden and that is just what happened in the Icelandic banks. Bullet loans were also a common feature of the US Savings & Loan crisis in the 1980s.

Lending on “hope value” and lack of expertise

At the Banking Inquiry Brendan McDonagh CEO of NAMA pointed out gave that the “banks were quite clearly lending to individuals and companies that, notwithstanding the massive sums involved, had little or no supporting corporate infrastructure, had poor governance and had inadequate financial controls and this applied to companies of all sizes.” In the case of around 600 NAMA debtors “…very few of them seemed to have any expertise in construction.”

Frank Daly mentioned “…lending on hope value…” where the lending related to “land which wasn’t even zoned, which had hope value more than anything else.”

There are also many Icelandic examples of these two features identified in the Irish report: lending on value that had not materialised or even was not clear would ever materialise – and lending to people who had no expertise of the type of projects on which they were borrowing.

The lack of expertise was not something Landsbanki held against the Icelandic businessman Gísli Reynisson when the bank lend him funds in spring 2007 to buy Copenhagen’s most prestigious hotel, D’Angleterre, as well as a second hotel and two restaurants, all in prime locations. Reynisson, who died in 2009, proudly stated to the stunned Danish media that he had indeed no experience of running hotels and restaurants but the opportunity seemed too good to pass on. While buying these Danish trophy assets he was also busy buying every fishmonger in Reykjavík. His earlier activity had mainly been properties and food production in Eastern Europe and the Baltics.

Another unique aspect of Icelandic lending to the banks’ favoured clients, i.e. the large shareholders and their business partners, was the consistent over-pricing, in the range of 10-20%: the clients would very often buy assets above asking price or above the value of these assets. Consequently, the banks persistently lent above value. The Icelandic businessmen invariably explained this by claiming over-paying was a way to shorten the negotiation time and time being money this made sense in their universe.

Whatever the real reason was, this over-pricing and consequent over-lending seems to be an Icelandic version of “hope value.” But it also meant that when asset prices started to fall both the borrowers and the lenders were far more vulnerable than if the assets had been keenly and more realistically priced.

All risk to the bank, little or none to the borrower

Both in Ireland and in Iceland the banks, with little else in mind than growth at any cost, fought fiercely over the clients with the biggest deals. In both countries this seems to have led to deterioration in both lending criteria and general banking practices. Interestingly, the net effect was the same in both countries: the risk fell on the lender, not the borrower.

The Irish report points out that the effect of this deterioration was that the banks provided the real funding whereas the equity from the borrower “usually existed only on paper.” As Frank Daly explained: “The result is that the borrower was typically not the first to lose. In the event of a crash the banks stood to take 100% of the losses, and that’s what happened.”

The same kind of lending to favoured clients in the Icelandic banks was common. Concentrated lending, both in terms of sectors and clients, constituted a huge risk in the Icelandic banks, effectively absolving the clients of risk. As stated in the SIC report: “…if a bank provides a company with such a high loan that the bank may anticipate substantial losses if the company defaults on payments, it is in effect the company that has established such a grip on the bank that it can have an abnormal impact on the progress of its transactions with the bank.”

In some cases brought by the Icelandic OSP, the charges relate to loans where the collaterals seemed to be weak or non-existent already when the loans were issued. Loans by Kaupthing to a group of under-capitalised or “technically bankrupt” (a description used in court by one of those charged) companies, leading to a loss of €510m for Kaupthing is one such example.

Partially blind auditors, passive regulators

Both in Iceland and Ireland it was evidently the biggest auditors, the international big four – Deloitte, EY, KPMG and PwC – that audited the banks. The two reports point fingers at the auditors: the audited accounts did not reflect the mounting risk. Both in Iceland and Ireland the banks were large clients of the auditors with all the implication it entails. All of this was going on in the realms of passive regulators.

As the Irish banks were concentrating their lending in 2007 and 2008 “to the property and construction industry at record rates, there were few “notes to the accounts” informing the reader of the potential risks involved with this strategy. Therefore, the audited accounts provided little information as to the implications of the risks undertaken.”

The Irish auditors’ riposte is that it was neither their role to advise clients on risk nor to challenge the banks’ business model. – That seems to be beside the point: the serious flaw in the auditors’ work was that leaving aside the auditors’ opinion of the risk and business model, the audits didn’t give the correct information on the banks’ position.

What made the situation worse was the long-standing relationships between the banks and their auditors: “In the 9 years up to the Troika Programme bailout, KPMG, EY and PwC not only dominated the audits of Ireland’s financial institutions, but they audited particular banks for extended, unbroken periods.”

On the regulatory side “there was passivity.”

According to the SIC the auditors did not “perform their duties adequately when auditing the financial statements of” 2007 and 2008. “This is true in particular of their investigation and assessment of the value of loans to the corporations’ biggest clients, the treatment of staff-owned shares, and the facilities the financial corporations provided for the purpose of buying their own shares. With regard to this, it should be pointed out that at the time in question matters had evolved in such a way that there was particular reason to pay attention to these factors.”

As to the Icelandic regulator, FME, it “was lacking in firmness and assertiveness, as regards the resolution of and the follow-up of cases. The Authority did not sufficiently ensure that formal procedures were followed in cases where it had been discovered that regulated entities did not comply with the laws and regulations applicable to their operations… insufficient force was applied to ensure that the financial corporations would comply with the law in a targeted and predictable manner commensurate with the budget of the FME.”

Cosiness and corruption

The Irish know a thing or two about corruption: the Mahon tribunal (1997-2012) and the Moriarty tribunal (1997-2011) did establish that leading politicians, i.a. Bertie Ahern, Charles Haughey og Michael Lowrie, received money from businessmen who profited from governmental favours. Consequently, corruption is a topic in the Irish Banking inquiry.

Nothing similar has ever been established in Iceland. The SIC did investigate loans from the three big banks to politicians. The highest loans are mostly related to spouses and nothing conclusive can be drawn from these loans.

There is however a striking Irish and Icelandic parallel in the cosy relationship between politicians and businessmen. In tiny Iceland these relations often stem from being the same age and having gone to the same schools, through friendships unrelated to business and politics or through family ties of some sort, either direct or indirect, through spouses or close friends.

Elaine Byrne, Consultant to European Commission on corruption and governance and well known in Ireland for her fight against corruption, pointed out the indirect aspect of cosy relations: “often … it is indirect and is a case of doing someone a favour and thereafter, down along the line, that person will return the favour in an indistinct way.” Doing it the old-fashioned way, with money is traceable, relationship is less so. “What the Moriarty tribunal in particular exposed was benefits in kind through different land transactions that may have arisen.” Benefits could later follow decisions. “Corruption is not black and white and is not direct. It is indirect and these relationships are very difficult to examine.”

The journalist Simon Carswell also mentioned what he called the “extremely cosy” relationship, on one hand between individuals in “the property sector, the construction industry, government, certain elected representatives and the banks” and on the other hand “the relationship between the Government, the banks and the financial supervisory authorities.” Carswell underlines a feeling among these parties of being on the same bandwagon leading to group-thinking within these institutions.

“These relationships appear to have been too cosy to have allowed any one of these collective groups, be it banks, government, builders or regulators, to shout stop and offer the kind of critical dissent that might have changed the behaviour of all and the direction in which the country was heading… contrarians were ridiculed, silenced or ignored to ensure the credit fuelled boom continued for years as their past warnings did not come true.”

The crisis would have been less costly and less severe, says Carswell, if someone belonging to these groups had had the courage to point out the dangers but these parties had it too good and were making too much money to speak out. The cost of the banking bailout is normally said to be €64bn but Carswell maintains that to this figure should be added losses on loans in all of the Irish banks, “well in excess of €100 billion, including tens of billions of euro covered by the UK Treasury. This is sometimes forgotten.”

The Banking Inquiry points out the cosiness in “the relationship banking, where some developers built strong relationships with particular banks, was a part of the Irish banking system. In some cases, both parties became business partners in a joint venture.”

There were also numerous Icelandic examples of joint ventures between the banks and their large clients. Nothing wrong per se and commonly found but also a potential basis for corrupt practices where joint ventures turn into a way of giving the chosen clients favourable treatment, i.e. with the banks giving these clients loans with no or little guarantee to fund their joint ventures.

Conclusions

It is abundantly clear that there were many signs of danger both in Iceland and Ireland prior to the banking collapse in these two countries. The pertinent question is if the proper lessons have been learned so as to prevent another similar future crisis. If read instead of buried the two reports do indeed provide a healthy antidote.

It was however not only the bad – and in proven cases in Iceland, criminal – practices that felled the Irish and the Icelandic banks. It was also the inherent risk of fast growth with regulators not keeping up and not realising the risk. In Iceland, the size of the banking system relative to the GDP topped at 10 times the GDP in early 2008, from around one GDP in 2002, around 150% of GDP in June 2015. In Ireland the banking system reached around eight times the GDP in 2008, is now just under five times. – The risk of the banking sector’s size might still be lingering in Ireland (and elsewhere!); this risk of a sector being so big that parliament and government tend to lack courage to set sensible limits to the financial system.

The Icelandic SIC allowed mining the banks’ accounts, also exposures to specific individuals, i.e. the banks’ largest shareholders and their business partners. This has given a keen understanding of how the banks really operated: by serving their largest shareholders way beyond reasonable risk and way beyond what other clients could expect. This was banking on and with a chosen circle that the banks helped to enrich.

One reason why it is important to make this information public is that it also explains why these individuals have done well after the banking collapse. Yes, they went through difficult times as many of their entities did fail but cleverly constructed company clusters, all with offshore angles, did make it possible for them to keep at least some of their assets showered on them as favours in an unhealthy banking system. It is no coincidence that many of the favoured clients are still operating, both in Iceland and Ireland.

*As can be seen on my blog I have often blogged on Ireland. Here are my blogs on the earlier reports on the Irish collapse: mentioning Regling and Watson but mainly on the Honohan report, as well as the report by Peter Nyberg in 2011. – Here is an excellent overview on the Banking Inquiry conclusions and recommendations, by Daniel McConnell.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

In the company of good books: recommended reading for Jeremy Corbyn

Jeremy Corbyn will no doubt discover that the wisdom of crowds isn’t always enough nor is meeting with busy world-famous economists and other wise-men and -women four times a year. Here are some books to hone his arguments and stimulate and inspire the intellectually inquisitive mind.

The distorting effect of debt and how to avoid socialising losses and privatise the profit

I’m almost finished reading House of Debt: How They (and You) Caused the Great Recession, and How We Can Prevent It from Happening Again by Atif Mian, Princeton and Amir Sufi, Chicago University. I had bought it even before Mark Carney recommended it; it was recommended to me soon after it was published last year.

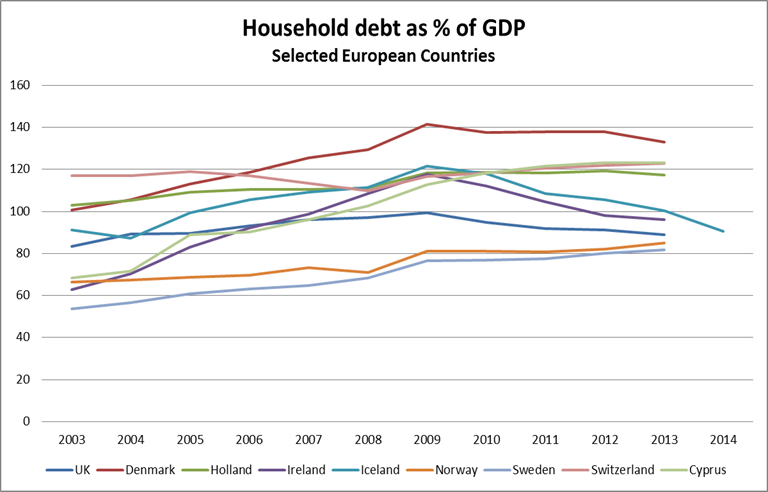

No doubt Corbyn knows why debt is harmful, why fueling the housing market with debt is dangerous and why it is ominous that household debt in the UK is high. But in order to clarify and stimulate the mind Mian and Sufi’s book is both an essential and timely read, also to argue against the received wisdom that banks are different from other companies and need to be saved – no, they don’t.

The two economists have formulated what they call “the primary policy lesson of bank support: To prevent runs and preserve the payment system, there is absolutely no reason for the government to protect long-term creditors and shareholders of banks.” – So true (as Icelanders know). Alors, an essential read, also to gather sensible arguments in the debate on banks and banking, debt and the housing market, all topics that the new Labour leader needs to be as skillful in debating as he is cultivating his allotment.

The anti-social mixture of aggressive tax planning, tax evasion and offshore havens

Tax and the revenue lost to society due to the anti-social mixture of aggressive tax planning, tax evasion and offshore havens are close to Corbyn’s heart. To my mind, the most illuminating writer on these matters right now is the French economist Gabriel Zucman, who studied with Thomas Piketty (they have written articles together) and who has recently (and sadly) left the London School of Economics for Berkeley. I read his little book on tax havens when it came out in French last year but now it has luckily been published in English, called The Hidden Wealth of Nations.

Much of the material is on-line and much of the reasoning is put forth in his 2013 article, The missing wealth of nations: are Europe and the U.S net debtors or net creditors? where Zucman i.a. points out “that around 8% of the global financial wealth of households is held in tax havens, three-quarters of which goes unrecorded.” – Yes, things to work on.

Inequality, health and wealth

These days, not only the lefties are preoccupied with inequality – not only is it socially harmful in terms of wasting and wasted human resources but it also hampers growth. An easy and insightful read, the harvested fruits of a lifetime of studying these issues, is gathered in The Haves and the Have-Nots: A Brief and Idiosyncratic History of Global Inequality, published in 2010.

As an economist at the World Bank, the author Branko Milanovic (blogs here) worked on these issues long before they turned into a fashionable topic beyond the left margin of politics. And being an economist with a wealth of fabulous statistics at his finger tips he is both brilliant at choosing and presenting intriguing numbers, also with some striking graphs.

The book that led me to reading Milanovic’ book was another very different but equally weighty book, also harvesting a life time of studying these issues. Angus Deaton’s The Great Escape: Health, Wealth and the Origin of Inequality, was published two years ago and I had the pleasure of listening to Deaton present his book in London last year.

Deaton is a professor at Princeton and the inspiration for the book is partly his own family story of better lives in the generations spanning the 19th and into the 20th century. He investigates inequality not only from the perspective of wealth but also health. One point is that better health not only depends on money but good institutions.

The great escape of the title is the escape from hunger and poverty, spanning centuries in historical overview. A riveting and optimistic read, though far from wishful thinking, i.a. on development. The clear conclusion is that concentrated wealth in the hands of few is now being used to buy influence on policy making for narrow special interests, not the general good of society.

The synthesis of privatisation

Again, Corbyn will not need to be exhorted in his doubts on privatisation but it is always good to gather insight and arguments for familiar causes, especially when you spend most of your waking hours arguing and reasoning for your points of view.

I read The Commanding Heights by Daniel Yergin and Joseph Stanislaw when it came out in 1998. At the time its full title was The Commanding Heights: the Battle Between Government and the Marketplace that is Remaking the Modern World (the latter part was changed in a later edition to The Battle for the World Economy; I prefer the old one, more telling; here is a 3 parts documentary based on the book). Readers of Lenin will recognise where ,,commanding heights” stems from.

At the time, I read it more or less in one go and have since given away several copies because I think that everyone remotely interested in politics should read it. Agree or not, it is essential to understand the driving forces behind privatisation especially for those who want to question them. I have for a long time meant to re-read it, would be interesting, considering events since the book was published.

The book is often taken to have been one big bravo for globalisation and privatisation but that was not my impression at the time. After all, the authors strongly warn against special interests and stress the need for legitimacy.

And something for the soul

Apart from reading up topics that nourish his political thinking and reasoning the soul must not be forgotten. Here I suggest two books that tell stories of the have-nots in different parts of Europe in the 1930s, shaped by circumstances and ideas of that time.

Independent People by the Icelandic Nobel price winner in 1955 Halldór Laxness was published in 1934. Inspired by Laxness’ infatuation with communism and socialism, it tells the story of Bjartur, a dirt-poor crofter who fights for being independent of others, without realising that his strife goes against his own interests.

Carlo Levi’s Christ stopped at Eboli is the memoir of his political exile in a remote part of Southern Italy, Basilicata, in the years 1935-1936, not published until 1945. In Iceland, the cold harsh climate made for a difficult life but in Italy the heat and the barren earth was no less harsh. Written by brilliant and reflecting minds, both books are further demonstrations of the topics above: debt, private ownership and inequality.

Cross-posted with A Fistful of Euros.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Iceland’s recovery: myths and reality (or sound basics, decent policies, luck and no miracle)

Icelandic authorities ignored warnings before October 2008 on the expanded banking system threatening financial stability but the shock of 90% of the financial system collapsing focused minds. Disciplined by an International Monetary Fund program, Iceland applied classic crisis measures such as write-down of debt and capital controls. But in times of shock economic measures are not enough: Special Prosecutor and a Special Investigative Committee helped to counteract widespread distrust. Perhaps most importantly, Iceland enjoys sound public institutions and entered the crisis with stellar public finances. Pure luck, i.e. low oil prices and a flow of spending-happy tourists, helped. Iceland is a small economy and all in all lessons for bigger countries may be limited except that even in a small economy recovery does not depend on a one-trick wonder.

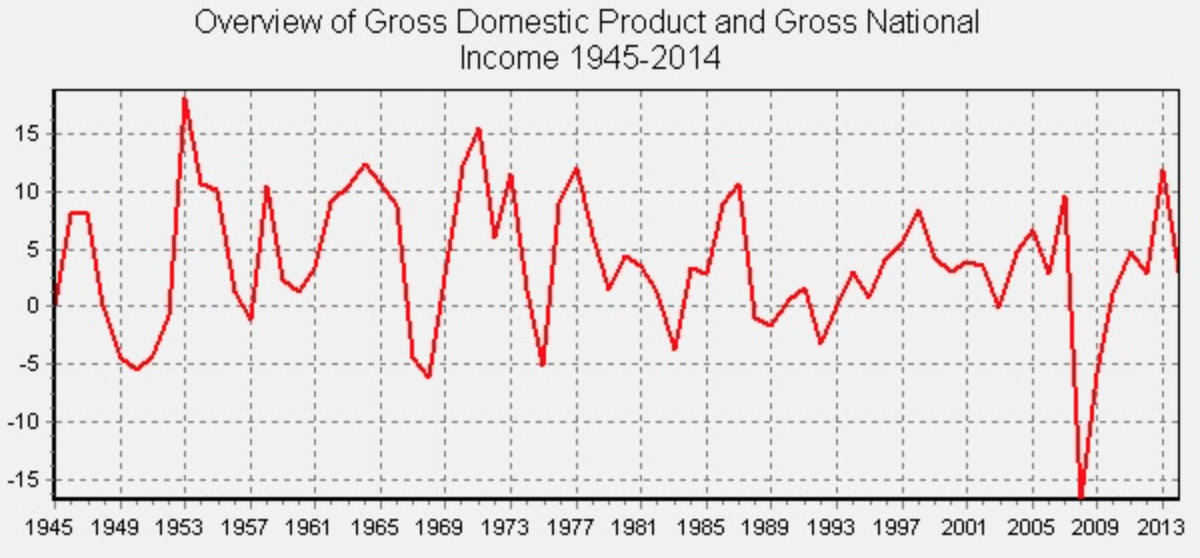

“The medium-term prospects for the Icelandic economy remain enviable,” the International Monetary Fund, IMF, wrote in its 2007 Article IV Consultation

Concluding Statement, though pointing out there were however things to worry about: the banking system with its foreign operations looked ominous, having grown from one gross domestic product, GDP, in 2003 to ten fold the GDP by 2008. In early October 2008 the enviable medium-term prospect were clouded by an unenviable banking collapse.

All through 2008, as thunderclouds gathered on the horizon, the Central Bank of Iceland, CBI, and the coalition government of social democrats led by the Independence party (conservative) staunchly and with arrogance ignored foreign advice and warnings. Yet, when finally forced to act on October 6 2008, Icelandic authorities did so sensibly by passing an Emergency Act (Act no. 125/2008; see here an overview of legislation related to the restructuring of the banks and here more broadly on economic measures).

Iceland entered an IMF program in November 2008, aimed at restoring confidence and stabilising the economy, in addition to a loan of $2.1bn. In total, assistance from the IMF and several countries amounted to ca. $10bn, roughly the GDP of Iceland that year.

In spite of mostly sensible measures political turmoil and demonstrations forced the “collapse government” from power: it was replaced on February 1 2009 by a left coalition of the Left Green party, led by the social democrats, which won the elections in spring that year. In spite of relentless criticism at the time, both governments progressed in dragging Iceland out of the banking mess.

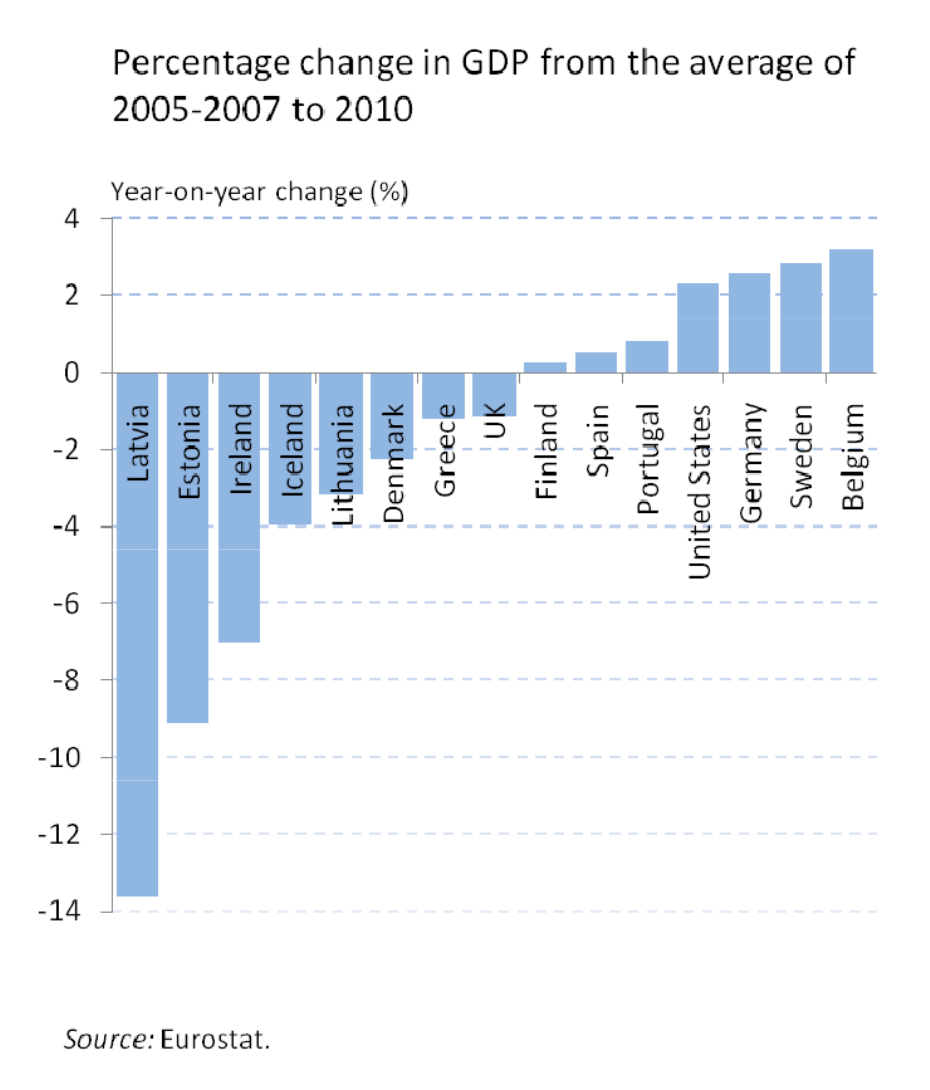

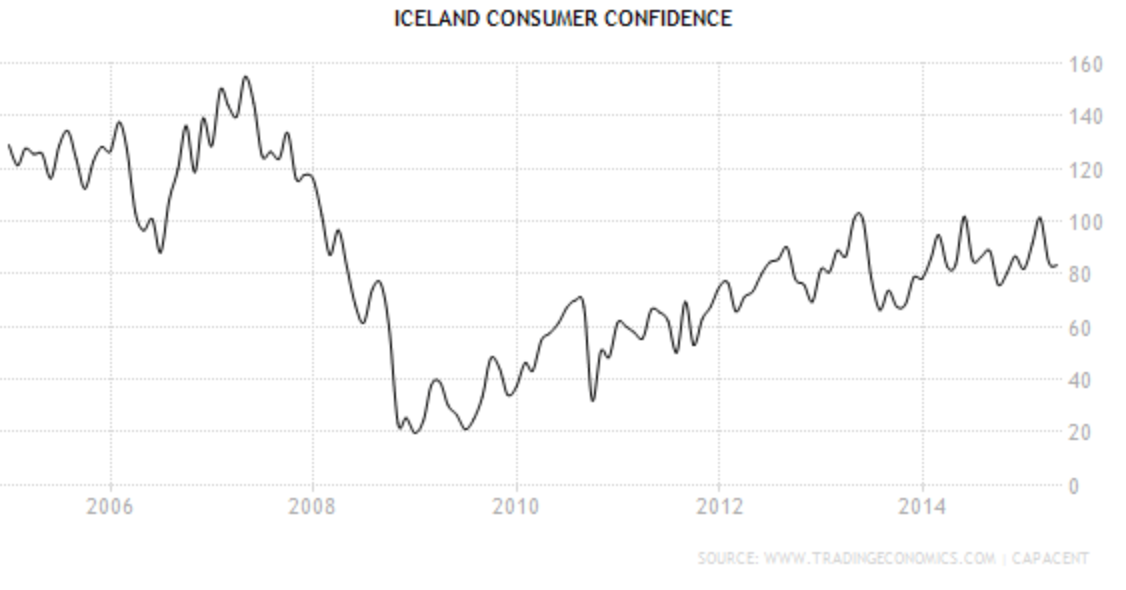

After the GDP contracted by 4% in the first three years the Icelandic economy was already back to growth summer 2011 and is now in its fifth year of economic growth. In 2015, Iceland became the first European country, hit by crisis in 2008-2010, to surpass its pre-crisis peak of economic output.

Iceland is now doing well in economic terms and yet the soul is lagging behind. Trust in the established political parties has collapsed: instead, the Pirate party, which has never been in government, enjoys over 30% following in opinion polls.

Compared to Ireland and Greece, Iceland’s recovery has been speedy, giving rise to questions as to why so quick and could this apparent Icelandic success story be applied elsewhere. Interestingly, much of the focus of that debate is very narrow and in reality not aimed at clarifying the Icelandic recovery but at proving or disproving aspects of austerity, the euro or both.

Unfortunately, much of this debate is misleading because it is based on three persistent myths of the Icelandic recovery: that Iceland avoided austerity, did not save its banks and that the country defaulted. All three statements are wrong: Iceland has not avoided austerity, it did save some banks though not the three largest ones and did not default.

Indeed, the high cost of the Icelandic collapse is often ignored, amounting to 20-25% of GDP. Yet, not as high as feared to begin with: the IMF estimated it could be as much as 40%. The net fiscal cost of supporting and restructuring the banks is, according to the IMF 19.2% of GDP.

Costliest banking crisis since 1970; Luc Laeven and Fabián Valencia.