Kaupthing – prison sentences for market manipulation reach Greece

On October 6 the Supreme Court in Iceland ruled in one of the largest collapse cases so car where nine Kaupthing managers were charged for market manipulation (see an earlier Icelog). As in a similar case against Landsbanki managers the Kaupthing bankers were found guilty. The Reykjavík District Court had already ruled in the Kaupthing market manipulation case in June 2015.

This is how Rúv presented the Supreme Court judgement in October. Kaupthing’s CEO Hreiðar Már Sigurðsson was sentenced to six months in prison, in addition to the 5 1/5 years in the so-called al Thani case where the bank’s executive chairman had received a four year sentence. The market manipulation case added a year to that case. Magnús Guðmundsson managing director of Kaupthing Luxembourg was found guilty but did not receive a further sentence, having been sentenced to 4 1/2 years in the al Thani case.

Other sentenced in October were Ingólfur Helgason managing director of Kaupthing Iceland, 4 1/2 years and Bjarki Diego head of lending 2 1/2 years. Four employees were found guilty: three of them got suspended sentences. The fourth, Björk Þórarinsdóttir was found guilty but not sentenced.

The investigations by the Office of the Special Prosecutor, now the District Prosecutor, have so far resulted in finding guilty around thirty bankers and others related to the banks. As I have often pointed out: the penal code in Iceland is mostly similar to the code in other neighbouring European countries but the difference was the will of the Prosecutor to investigate very complex cases, taking on a huge task undaunted. That’s the difference – no case was seen as being too complicated to investigate.

Last week, the following article was in one of the Greek papers. From the photos I can see that this article is about the above case. Something for the Greeks to ponder on: what’s done in Iceland, less in Greece.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Iceland: back to its old conservative roots?

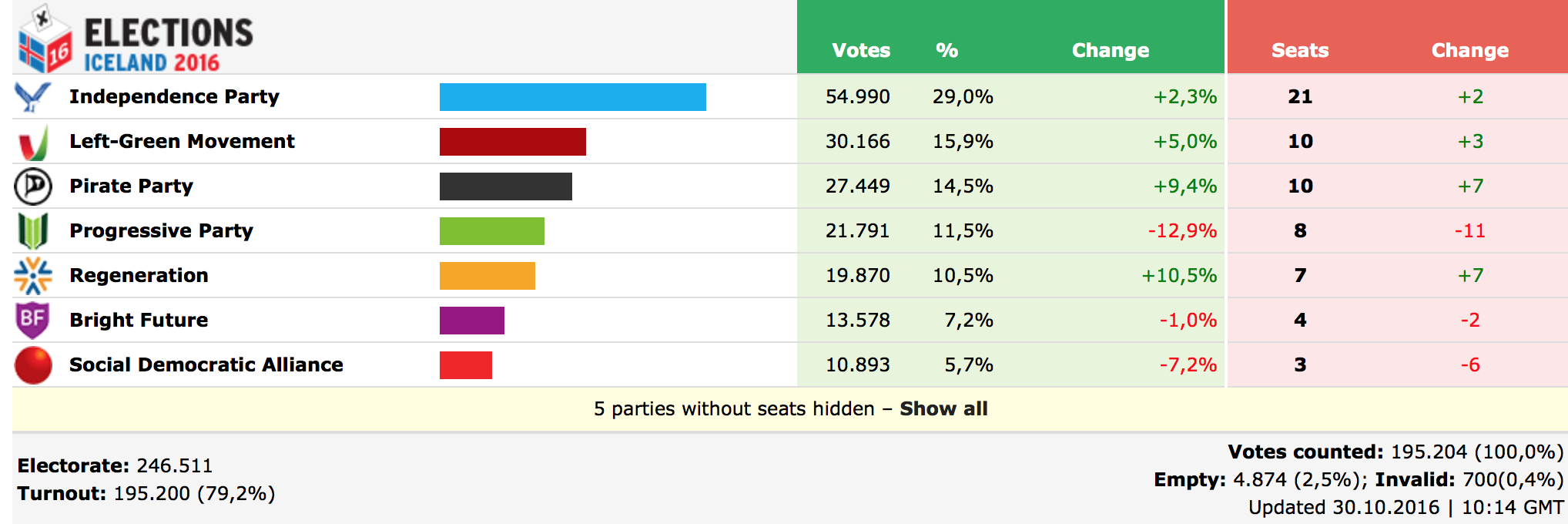

“Epic success! There are a lot of coalition possibilities” tweeted elated newly elected Pirate MP Smári McCarthy the morning after polling day. Quite true, the Pirates did well, though less well than opinion polls had indicated. Two of the four old parties, the Left Greens and the Independence Party could also claim success. The other two oldies, the Progressives and the Social Democrats, suffered losses. Quite true, with Bright Future and the new-comer Viðreisn, Revival, in total seven instead of earlier six parties, there are plenty of theoretical coalition possibilities. But so far, the party leaders have been eliminating them one by one leaving decidedly few tangible ones. Unless the new forces manage to gain seats in a coalition government Iceland might be heading towards a conservative future in line with its political history.

In spite of the unruly Pirates and other new parties the elections October 29 went against the myth of Iceland abroad as a country rebelling against old powers – the myth of a country that lost most of its financial system in a few days in October 2008 instead of a bailout, then set about to crowd-write a new constitution, investigate its banks and bankers and jailing some of them and is now, somehow as a result of all of this, doing extremely well.

True, Iceland is doing well – mostly due to pure luck: low oil prices, high fish prices on international markets and being the darling of discerning well-heeled tourists. No new constitution so far and at a closer scrutiny the elections results show a strong conservative trend, in line with the strong conservative historical trend in Icelandic history: during the 72 years since the founding of the Icelandic republic in 1944 the Independence Party has been in government for 57 years, most often leading a coalition and never more than two to three years in opposition except when the recent left government kept the party out in the cold for four years, 2009 to 2013.

The results: historic shift to new parties

(From Iceland Monitor)

With 63 MPs the minimum majority is 32 MPs.

Of the seven parties now in Alþingi four are seen as the old parties – Independence Party, Left Green, Progressives and the social democrats – in Iceland often called the “Four-party.” Their share of the votes was 62%, the lowest ever and down from 75% in the 2013 elections, meaning that the new parties grabbed 38%. A historic shift since the old parties have for decades captured 80-90% of the votes. The Four-party now has 42 seats, the new-comers 21 seats.

The left government 2009 to 2013: an exception rather than a new direction

As strongly as the Nordic countries have been social democratic Iceland has been conservative. And still is. Iceland is not living up to its radical image and the left government of 2009 to 2013 was more the exception than a change of direction. The present outcome shows no left swing but the swing to the new parties may prove to be a game changer in Icelandic politics.

The left parties, Left Green and the social democrats, now have thirteen seats, compared to sixteen in 2013, the centre/neither-left-nor-right Bright Future, the Pirates and the Progressives have 22 seats, 28 in 2013 but the right/conservative parties, the Independence Party and Revival, are the largest faction with 28 seats, up from nineteen in 2013. – As I heard it put recently in Iceland there are Progressive-like conservatives in all parties and the Progressives tend to strengthen the worst sides of the Independence Party, such as illiberal cronyism.

With seven parties in Alþingi, the Icelandic Parliament, up from six during recent parliamentary term, the party game of guessing the possible coalition, both in terms of number of MPs and political synergies, is now on in Iceland.

A right centre outcome seems more likely than a left one

It’s the role of the president to decide which leader gets the mandate to form a government, normally the leader of the largest party but other leaders are however free to try. The task facing the newly elected president Guðni Th. Jóhannesson, a historian with the Icelandic presidency as his field of expertise, seems a tad complicated.

The president followed the traditional approach and gave the mandate to Bjarni Benediktsson leader of the largest party, the Independence Party who first met with the Progressive’s Sigurður Ingi Jóhannsson who lead the Progressive-Independence coalition that has just resigned. The two parties now only have 29 seats between them. – Given the right-leaning/conservative weight in Alþingi a right-centre government might seem more likely than a left government.

The leader of Bright Future Óttar Proppé, seen as a possible coalition partner for the conservatives, seemed surprisingly unenthusiastic: to him a coalition with the Independence Party and Revival “doesn’t seem like an exciting option,” adding that there is a large distance policy-wise between his party and the largest one.

Proppé had earlier suggested to the president that Revival’s leader Benedikt Jóhannesson be given the mandate; Jóhannesson has already suggested he’s better poised to form a government than Benediktsson since Revival can appeal both to left and right.

Katrín Jakobsdóttir leader of the Left Green has stated that her party would be willing to attempt forming a five party centre-left coalition, i.e. all parties except the Independence Party and the Progressives, a rather messy option. The Pirates leader Birgitta Jónsdóttir has said her party could defend a minority left government.

Four winners

Since the founding of the Republic of Iceland in 1944 the Independence Party has always been the country’s largest party and the one most often in government. Its worst ever result was in the 2009 elections, when it got only 16 seats. Getting 19 in 2013 and 21 seats now may seem good but it’s well below the now unreachable well over 30% in earlier decades. Yet, gaining two seats now makes the party a winner.

Its leader Bjarni Benediktsson sees himself as the obvious choice to form a coalition, given the support of his party but it will strongly test his negotiation skills. In the media he comes across as rather wooden but he’s popular among colleagues, which might make his task easier though he can’t erase policy issues unpopular with the other parties such as the parties anti-EU stance and being the watchdog of the fishing industry.

The Left Green Movement was formed in 1999 when left social democrats split from the old party and joined forces with environmentalists. The Left Green has always been the small left party but is now the largest left party next to the crippled social democrats. The elf-like petite Katrín Jakobsdóttir has imbued the party with fresh energy. Her popularity, far greater than the results of the party, no doubt helped secure a last minute swing against predictions. She has been the obvious candidate to lead a left-leaning government, now an elusive opportunity.

Viðreisn, Revival, is a new centre right party, running for the first time but founded in disgust and anger by liberal conservatives from the business community. In general they felt the Independence Party was turning too illiberal, too close to the fishing industry so as to lose sight of other businesses.

But most of all the Revivalists were angered by the broken promises of the Independence Party in 2013 regarding EU membership. During the 2013 campaign the party tried to ease out of taking a stance on EU by promising to hold a referendum asking if EU membership negotiations should be continued. Once in government the Independence Party broke this promise causing weeks of protests and widespread anger some of which Revival captured.

Revival’s founder Benedikt Jóhannesson was seen as an unlikely leader and admitted as much to begin with but has proved an adept leader, also by attracting some strong and well-known candidates from the Icelandic business community. Getting seven MPs in its first run spells good for the party but history has shown that getting elected is the easy part compared to keeping a new party functioning in harmony. However, the Revival’s energetic start has for the first time in decades given the Independence Party a credible competition on the right wing.

The outcome has made Jóhannesson flush with success and he was quick to put his name forward as the right person to form and lead a centre right government. Revival did no doubt capture some Independence party voters but many of them had already defected to the social democrats now leaving that party for Revival.

The Pirate Party is the winner who lost the great support shown earlier in opinion polls, probably never a likely outcome; growing from three MPs to ten is the success McCarthy tweeted about. The party rose out of protests and demonstrations after the 2008 calamities and ran for the first time in 2013, winning three seats.

Their feisty leader Birgitta Jónsdóttir, with 32.000 Twitter followers and foreign fame for her involvement with Wikileaks and Iceland as a data protection haven, is unlikely to be the first Pirate prime minister in the world. Given that the party has had some in-house friction to deal with – they had to call in an occupational psychologist to restore working relations – the unity of the parliamentary group might be in question, making the party less appealing for others as a coalition partner.

Two losers and one survivor

The Social Democrats suffered a crushing defeat, even worse than the opinion polls had predicted and worse than the dismal outcome in 2013. As parties consumed with infighting – the UK Labour Party springs to mind – the energy of the Social Democrats has been wasted on infighting at the cost of a constructive election campaign. Common to other sister parties in Europe the Icelandic Social Democrats have not been able to come up with a convincing policy and its standing with young people is low.

Party leader Oddný Harðardóttir struggled with her speech on election night when all she seemed to be able to think of was that the party once had a good cause; the long list of helping hands she named sounded like each and every of the few voters left. Harðardóttir has now inevitably resigned, giving space for more destructive infighting. Some wonder if the party will survive, others speculate its remains will unite with the Left Green and restore unity and strength on the left wing. Historically seen, the Icelandic left has always split when it grew, adding strength to the right wing and the indomitable Independence Party.

The Progressive Party has lost its incredible upswing of nineteen MPs in 2013 to a much more plausible eight MPs. Plausible, because its upswing to 24% in 2013 was built on cheap promises made by its leader Sigmundur Davíð Gunnlaugsson that brought him all the way into the Prime Minster’s office. But the votes had hardly been counted in 2013 when voters started to lose faith in the party: it has been on a downward slide towards a more natural, in a historical perspective, just over 10% shares of votes.

This old agrarian centre party, sister party of other old Nordic centre parties of similar origin, has traditionally been related to the Icelandic now mostly defunct cooperative movement and still close to certain special interests in agriculture and fishing. Its strength was to appeal to both the left and the right but under Gunnlaugsson it turned more nationalistic/right-leaning, trying to appeal equally to urbanistas and racists and not only old farmers. His successor, representing more traditional Progressive policies might revert to the old party roots, yet needing to find a modern twist for an old party slowly losing ground.

The Panama Papers exposed Gunnlaugsson as a cheat – he had kept quiet about the infamous Wintris, the offshore company he owned with his wife, meaning the couple had huge assets abroad as Icelanders were locked inside capital controls – and a liar as he tried to ease out of the story. He lost his office and then lost his leadership of the party only shortly before the elections. After the elections he claimed to have had a campaign plan, which would have taken the party to 19%. “A bad loser” commented one Progressive ex-MP. Gunnlaugsson’s successor Sigurður Ingi Jóhansson dryly said Gunnlaugsson had not shared this plan with the party leadership.

Bright Future is one of several parties that rose out of protests following the 2008 banking collapse, partially an offspring of the group close to Jón Gnarr the comedian-turned-mayor of Reykjavík 2010 to 2014. It was the new political darling in 2013, securing six MPs. Seen as a centre left liberal party its leader Óttar Proppé is a soft-spoken intelligent politician. The party has recently been hovering around the 5% limit needed to secure a seat in Alþingi but did in the end better than forecasted, losing only two of six seats. Consequently, the party still has a future in Icelandic politics and possibly even a bright one as it might be essential whatever part of the political spectre a coalition will cover.

Scrabbling with numbers – the eliminated options

Juggling parties and numbers of MPs – the minimum majority is 32 MPs – there are in total seventeen possible combinations for a coalition. Although the Progressives have traditionally been a true centre party appealing to left and right, the first elimination seems to be the Progressive Party, unless a path is found around one specific hindrance: the former party leader.

Were the Progressives offered to be in a coalition and given that Gunnlaugsson is an MP it’s almost unthinkable to form a government without him as a minister; but it seems equally unthinkable that the other parties would want to be in government with him. His career as a prime minster has given all but his ardent admirers the feeling that he is shifty and untrustworthy. His admirers will say that opponents fear his toughness.

In spite of losses the Progressive leadership is eager to get into government but Progressive leader Jóhannsson has so far evaded answering if the party could join a coalition without Gunnlaugsson as a minister. There are speculations that the parliamentary group is split: some support Gunnlaugsson, others his successor but some are now speculating that the party would indeed willingly sacrifice Gunnlaugsson in order to get into government again.

Both Left Green Katrín Jakobsdóttir and the Pirates’ Birgitta Jónsdóttir have excluded joining a government with or lead by the Independence Party. When Jónsdóttir went to meet Benediktsson, holding court to hear views of all the parties, she said she doubted that his party was interested in fighting corruption, a key Pirate issue.

Revival’s Benedikt Jóhannesson excluded reviving the present government of Progressives and the Independence Party by joining them. – Thus, the realistic possibilities seem quite fewer than the theoretical ones.

Scrabbling with numbers – the realistic options

Out of the flurry of the first days and considering parties and policies the most realistic combination seemed to be a government with the Independence Party, Bright Future and Revival. That poses an existential dilemma for Revival: though ideologically close to the Independence Party there is this one marked exception – the EU stance.

In the same vein as the British conservatives, to whom the Independence Party is much more similar than to its Nordic sister parties, the anti-EU sentiments have over the years gradually grown stronger. Bjarni Benediksson was on the pro-EU line around ten years ago but not any longer. The lack of EU option on the right was indeed the single most important reason why Revival was founded as mentioned above.

Jóhannesson is a former fairly influential member of the Independence Party – and a close relative of Benediktsson in a country where blood is always much thicker than water and family-relations matter. One of the party’s MPs, Þorgerður Katrín Gunnarsdóttir, was a minister for the Independence Party in 2003 to 2009 but left politics after the banking collapse, tainted by her husband’s high position with Kaupthing, at the time the largest bank in Iceland.

The question most often put to Revival candidates during the election campaign was if the party wasn’t just the Independence Party under another name. Going into government simply to help the Independence Party stay in power would be unwise as Revival would risk to be seen as exactly that what it’s claimed to be: the Independence Party under another name.

Fishing quota – and EU: a lukewarm topic but possibly a political dividing line

Revival will have to take up the EU matter, i.e. in a coalition with the Independence Party it would have to get that party to fulfil its 2013 promise to hold a referendum on the EU negotiations started under the Left government in summer of 2009. At the time EU membership was driven by the social democrats in spite of the Left Green anti-EU stance: the social democrats had for years campaigned for EU membership, also in the 2009 spring election, and once in government felt they had the mandate to open membership negotiations. The plan was to put a finalised membership agreement to a referendum on membership. Ever since the negotiations started anti-EU forces have claimed it was without a mandate.

The attempts of the Progressive-Independence coalition after it came to power in 2013 to end the negotiation turned into a farce: the two parties didn’t want to bring it up in Alþingi where it risked being voted down and the EU didn’t want to accept a termination unless supported by a parliamentary vote.

Forcing a referendum on the membership negotiation would fulfil Revival’s EU promises and it could most likely count on the support of Bright Future. For the Independence Party it would be a very bitter pill to swallow. Opinion polls have always shown a majority for negotiating though there rarely has been a majority for joining the EU. Event though EU membership isn’t an issue in Icelandic politics it could well draw certain insuperable lines in the coalition talks.

If Revival’s Jóhannesson should be given the mandate to form a government as Bright Future’s Proppé has suggested it would certainly strengthen Jóhannesson’s agenda.

Apart from EU policy Revival has fought for a new agriculture policy, away from the old Progressive emphasis on state aid and most of all for a new way to allocate fishing quota, a hugely contentious issue in Icelandic policies. The two old former coalition partners are dead against any changes whereas all the other parties have presented more or less radical policies to change the present fishery system.

Left government in a conservative country

Ever since the 2013 elections, which ended the left government in power since 2009, the opposition parties have aired the idea of joining political forces against the Progressive-Independence coalition.

Few days before the elections the Pirate leader Birgitta Jónsdóttir called the opposition to a meeting to prepare some sort of a pre-elections alliance or as she stated to clarify the options for a coalition. Revival didn’t accept the invitation and Bright Future wasn’t keen. The Independence Party claimed this was a first step towards a left government and by stoking left fears this Pirate initiative might indeed have driven voters to the conservatives.

Jónsdóttir is now peddling a more simple solution: a minority government of Revival, Bright Future and Left Greens that the Pirates, together with the remains of the Social Democrats, would support. Five parties in a government sounds chaotic – coalitions of three parties have never sat a full term in Iceland. And given the alleged tension in the Pirate Party the other parties might be wary of fastening their colours to the Pirate mast, inside or outside a government.

Minority governments have been rare in Iceland contrary to the other Nordic countries and suggesting this solution as politicians are only starting to explore coalition options will hardly tempt anyone until possibilities of a majority government have been exhausted.

Supporting a government but not being in it would be a plum position for the Pirates. The party has pledged to finish the new constitution, in making since 2008. A new constitution needs to be ratified by a new parliament and the Pirates had called for the coming parliament to sit only for s short period, pass a new constitution and then call elections again. No other party is keen on this and there has been only a limp political drive to finalise a radical rewrite of the constitution.

There are those who dream of a government spanning the Independence Party and the Left Green; this government would however need the third party to have majority. For anti-EU forces this is the ideal government since it would most likely prevent any EU move. But as stated: Left Green Jakobsdóttir has so far claimed the distance between the parties is too great, leaving no basis for such a coalition.

Discontent in a boom without xenophobia and racism

In a certain sense all the new parties are protest parties but not with the sheen of demagogy seen in many other recent European protest parties. The response to the banking crisis and the ensuing massive fall in living standards was certainly a protest against the four old parties giving rise to various new parties of which Bright Future and the Pirates are the only ones now in Alþingi.

The only real touch of demagogy with a tone of xenophobia didn’t come from any of these parties but from the Progressive Party under the leadership of Gunnlaugsson in the 2013 elections and the 2014 local council elections. However, there has so far never been any real appetite in Iceland for this agenda. The Icelandic Popular Front, lingering on the fringe of Icelandic politics for years and the only party offering a pure xenophobic racist agenda, this time got the grand sum of 303 votes or 0.16%.

Compared to the political environment in Europe the real political sensation in Iceland, so far, is that there is no sign of the xenophobia and outright racism in the main parties. Yes, people lost jobs following the 2008 collapse but there wasn’t the sense that foreigners were taking jobs or that foreigners were to blame. As so clear from the debate on foreigners, inter alia in Britain, sentiments normally override facts and figures. These sentiments can be heard rumbling in Iceland but have so far not flourished.

Although the economy has been growing since 2011 following the sharp downturn the previous years and is now booming the discontent is still palpable. Very much directed towards politicians based on a sense of cronyism and the sense that politicians, especially from the old parties, are there to guard and aid special interests such as the fishing industry and wealthy individuals with political ties.

Gunnlaugsson with his Panama connections was ousted. But both Bjarni Benediktsson and Ólöf Nordal his deputy chairman, named in the Panama Papers, have brushed it off easily. Nordal was linked to Panama through her husband, working for Alcoa, but claimed the company was just an old story. Benediktsson owned an offshore company related to failed investments in Dubai and also claimed it was an old story, causing remarkably little curiosity and coverage in Iceland.

The left government, in power 2009 to 2013, did in many ways tackle the ever-present cronyism in Iceland by using stringent criteria and gender balance for hiring people on boards, leading jobs in the public sector etc. Yet, it earned little gratitude for this. One of the most noticeable changes when the Progressive-Independence coalition came to power in 2013 was its reverting back to the bad habits of former times. Over the last few years sales of certain state assets have also raised some questions. Sales of the two now state-owned banks and other state assets on the agenda these will again test the Icelandic hang to cronyism and corruption.

The underlying discontent in booming Iceland possibly shows that it’s not only the economy that matters. But it also shows that after a severe shock it takes time for the political powers to gain trust. The coming four years will be a further test. As one voter said: “I would have liked to see all parties acknowledge the events in 2008 and come forth with a plan as to how to how to avoid the kind of political behaviour that led to the 2008 demise – but there was no such comprehensive plan.”

– – –

The new Alþingi: The new gathering of MPs has a greater number of women than ever before: 30 MPs of 63 are women. The tree youngest MPs are born in 1990, the oldest, and newly elected, is born in 1948. Katrín Jakobsdóttir, born in 1976, is one of seven MPs voted into Alþingi before 2008. Following the three last elections a large number of MPs have left and new ones coming in. As prime minister Sigurður Ingi Jóhannsson said it’s good to get new energy into the austere halls of Alþingi but it’s equally worrying to lose competence, knowledge and experience: 22 have never sat in Parliament before, ten are new but with some parliamentary experience, in total 32 out of 63 MPs.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Elections in Iceland: voters seem to prefer new to old as never before

After remarkably large swings in opinion polls it seems that the old and largest party, Independence Party, is picking up support from voters, shown in one poll to pick up 27% of votes. The Pirate Party, which has at times touched 40% in polls is now settling at just above 20%. With nine parties running country-wide and twelve parties in total offering their ideas to the voters Icelanders have enough to choose from in the elections October 29. The big news is that the four old parties, or the “four-party” as Icelanders call them are now only polling at fifty or sixty per cent, the lowest in the roughly one century old history of the old parties, meaning that the new parties are taking forty to fifty per cent.

Iceland provides a clear argument that the economy isn’t everything in elections; Icelandic voters seem to choose leaders they find trustworthy, regardless of policies. In spite of strong economy a new party untested in government like the Pirate party has held a strong appeal, robbing some of the old parties of support. The old parties are the Independence Party, the Progressives, the SD Alliance and the Left Green but the new ones are the Pirates, Bright Future Viðreisn and some smaller parties unlikely to get into parliament.

Now, as the day of reckoning October 29 looms opinion polls indicate that the tried and tested are attracting voters again. That helps the Independence party and to some degree the Progressive party that after the hapless Winstris affair of its leader chose a new leader, Sigurður Ingi Jóhannsson, who has been serving as a prime minister since Sigmundur Davíð Gunnlaugsson resigned in April due to the Panama Papers. Yet, nothing is like it once was – the old parties are appealing to fewer voters than ever.

The latest figures

The latest figures out Friday October 28 vary quite a bit but still show a jump for the Independence party. The Independence Party has the greatest success in a Gallup poll, at 27% with Pirates at 17.9%, Left Green 16.5%, the other government coalition party the Progressives at 9.3%, Viðreisn (“Restoration,” a new liberal centre-right party) 8.8%, the Social Democratic Alliance 7.4% and Bright Future 6.8%. Other parties are below the 5% threshold needed to get into parliament. All these parties except Viðreisn are already in parliament.

MMR poll shows the Independence party at 24.75%, Pirates 20.5%, Left Green 16%, Progressives 11.4%, Viðreisn 8.9%, Bright Future at 6.7% and the Social Democratic Alliance 6.1%.

Morgunblaðið, the daily, also published today its last poll before the election, putting the Independence party at 22.5%, Pirates 21.2%, Left Green 16.8%, Viðreisn 11.4%, Progressives 10.2%, Bright Future 6.7% and the SD Alliance 5.7%.

On the whole the Pirates have lost their incredible popularity a year ago but are still competing with the Independence party for the highest amount of votes – a remarkable success for a young party, only running for the second time.

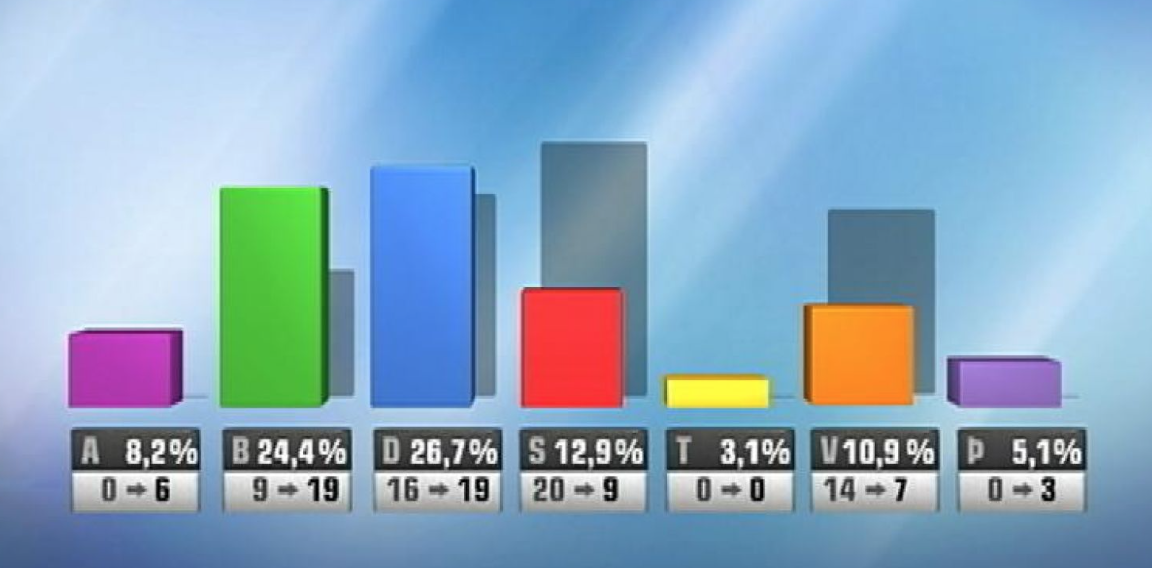

The outcome 2013

The 2013 elections resulted in the largest losses ever for any parties when the two left parties in government, the Left Green (V above) and the SD Alliance (S) went from being two big parties to two small parties, from jointly having 34 members to 16. The Left Greens have, according to the recent polls, been gaining strength under their young energetic leader, Katrín Jakobsdóttir, minister of education and culture in the 2009-2013 left government. The SD Alliance seems to be stuck in spite of a new leader recently elected, Oddný Harðardóttir, who has only made things worse for the party according to the polls.

In the 2013 elections Bright Future (A) literally lived up to its name, as the new darling in the hood and got 6 members, a phenomenal success for a new party. Now it’s hovering just above the 5% limit. The Pirates (Þ), another new party, got 3 members. The present coalition partners, the Independence Party (D) and the progressives (B) got the same amount of MPs; the Independence Party got a greater numbers of votes but the Progressives made a larger jump and against the tradition of giving the largest party the mandate to form a government the then president Ólafur Ragnar Grímsson gave the Progressives the mandate for form a government.

The Pirate party: not as wild as the name suggests

Since early this year I’ve heard foreign analysts and other pundits worry that the rise and rise of the Pirate party bode ill for political and financial stability in Iceland. That is however not the perception in Iceland. The main reason for their popularity is their measured and reasonable performance in Alþingi, the Icelandic parliament. Making big and broad promises is for example not their way of doing politics.

Their main focus has been on the new constitution, on finishing the work in progress, and they are very much wedded to the idea of the Alþingi sitting for only enough time to pass a new constitution and then vote again as is needed; a new constitution needs to be agreed on by two parliaments. This might very well drive other parties away from a Pirate-led coalition, even if they might otherwise be positioned to lead a new government. Other parties just want to get things done and not be tied up by a short-term constitution-only Alþingi.

Apart from the constitution the Pirates reject the left right dualism but support left-wing welfare issues like free health-care, not the case in Iceland, public ownership of natural resources, direct democracy and fight against corruption – all issues that have loomed large in the election debate.

What colour of coalition?

If the Independence Party turns out to be the biggest party come Sunday morning its leader will start to ask around for support among other parties. Nothing indicates that the Progressives will be strong enough for a two-party coalition. In addition, it would be difficult to sideline Sigmundur Davíð Gunnlaugsson who will almost certainly be elected to Alþingi in spite of having resigned as a party leader and prime minister.

The feeling is however that none of the other parties are keen to be with him in government, which means that the Progressives are unlikely to be in government however things go. In politics “never say never” but suffice it to say that a government including the Progressives seems unlikely.

The new liberal conservative party Viðreisn doesn’t seem to be much of a help. Incidentally, its leader Benedikt Jóhannesson was earlier active in the Independence Party and is, as most well-informed Icelanders know, closely related to Benediktsson in a family where blood certainly is thicker than water, as the saying goes in Iceland.

Viðreisn portrays itself as more liberal, less wedded to old power and old money and is EU-friendly, hardly relevant in Iceland these days. Many voters see Viðreisn as all too ready to jump into bed with the Independence Party but it seems to have attracted many SD Alliance members on the party’s right side. SD Alliance, earlier often in coalition with the Independence party, has hardly any political strength to be in government and would in any case provide too few if any MPs.

It has happened in Icelandic politics that the Independence Party, in most governments in Iceland since the founding of the republic in 1944, has cooperated with the far left. Jakobsdóttir has not been flirting with that idea at all, underlining that there is little if any political harmony between the two parties. Bar something unexpected it’s difficult to imagine that any of the four old parties could form a coalition lead by or together with the Independence Party.

All of this, in addition to the polls, many think that a left government is more likely than a centre-right government. That again would probably require at least three parties to form a government, even four. Needless to say the greater the number the more potential for splits and a politically lame government. The next PM could be a lady, most likely Jakobsdóttir. The Pirate Birgitta Jónsdóttir has indicated that she would be more interested in being president of the Alþingi, rather than a prime minister but there are some popular Pirates around her.

Strong economy isn’t enough

The turmoil in Icelandic politics since the winter of 2008 to 2009 is over in the sense that the pots and pans stay in the kitchens. Yet, the political distrust is still palpable and strong economy and what’s best described as boom doesn’t change the fact that voters seem more ready than ever to embrace new parties and, except for the Left Green, keep the old “fourparty” at bay.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

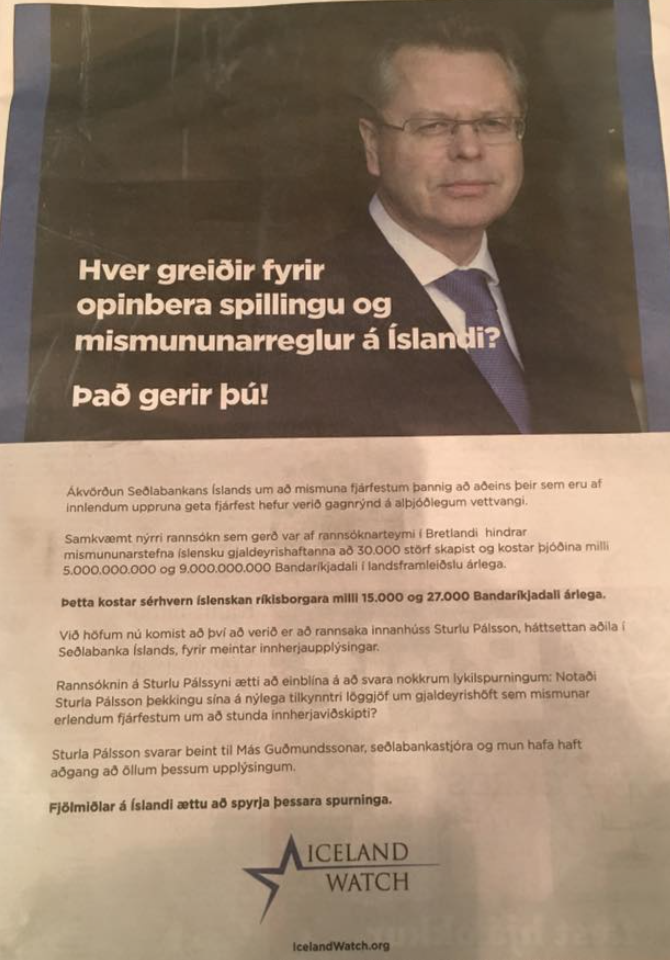

Further to the Iceland Watch campaign

For the second day, the Iceland Watch, watching over the interest of the four largest offshore króna holders, has published an ad in Iceland warning Icelanders of corruption and claiming that an official at the Central Bank of Iceland is under investigation at the CBI for insider trading. The whole page ad is under a big portrait of the governor of the CBI Már Guðmundsson, see my yesterday blog.

This morning, the governor met with prime minister Sigurður Ingi Jóhannsson, Lilja Alfreðsdóttir minister of foreign affair and minister of finance Bjarni Benediktsson. After the meeting Guðmundsson said that no Icelandic action is being planned. He said the CBI was certain the measures taken regarding the offshore króna in order to protect the Icelandic economy were sound. “Of course there might be a reason to worry that people get the idea to put out statements like these but there is no reason to worry that any of the statements (in the ad) is based on fact because it isn’t,” Guðmundsson said to Rúv.

Negative response from the EFTA Surveillance Authority

The four funds holding offshore króna and contesting the measures taken earlier this year are Eaton Vance, Autonomy Capital, Loomis Sayles and Discovery Capital Management. This summer, two of the funds, Eaton Vance, brought the Icelandic offshore króna measures to the attention of the EFTA Surveillance Authority, ESA. Already in August ESA answered the complaint pointing out that it had already dealt with a number of complaints regarding the Icelandic capital controls.

The ESA conclusion was:

“It follows from the assessment set out above that an EEA State enjoys a wide margin of discretion as regards the adoption of protective measures as long as the (sic) comply with the substantive and procedural requirements of Articles 43(4) and 45 EEA. Once compliance with these requirements has been established, the exercise of the powers conferred on an EEA State pursuant to Article 43 EEA precludes the application of primary provisions in the sector concerned (such as Article 40 EEA).

Having taken account of the information on the facts of this case and the applicable EEA law, the Directorate cannot conclude that the Icelandic Government has erred in its application of Article 43 EEA.”

Eaton Vance was invited to submit its observations, which it did in September. ESA is now considering this last submission but given the earlier answer and previous ESA cases regarding the capital controls it now seems unlikely that Eaton Vance’s argument will win ESA over. That decision will then be final; there is no other instance to appeal to. So far, the EFTA Court has dismissed ruling on ESA decisions.

Who is behind the ads and the offshore króna holders?

Over the years, Icelanders have furiously speculated that there are large Icelandic stakeholders among the offshore króna holders. Nothing that I have seen or heard so far indicates that this is the case.

I’ve said earlier that there may well be Icelanders owning or having owned offshore króna but I find it highly unlikely that any of them hold large interests in the four main funds who own the largest part of the remaining funds, now ca. 10% of Icelandic GDP (see here for a recent overview of the capital controls and offshore króna from the CBI).

Funds as these four organise their investments normally in separate offshore funds as the maturity of underlying assets vary etc. Some of these funds may well have Icelandic names but I would imagine the names relate to the place of investment rather than the owners being Icelandic.

As I’ve pointed out earlier the funds have allied with Institute for Liberty, mostly dormant since it fought the Obama care some years ago and now revived with the offshore króna cause. The PR company DCI Group, based in Washington, is advising the funds. As far as I can see these are the entities driving the campaign against Iceland.

Baseless claims of Iceland in breach

The bombastic claims by Iceland Watch that Iceland is somehow breaching international rules and regulations have so far been shown to be baseless. As pointed out earlier, the International Monetary Fund has not criticised the measures taken in Iceland and these measures, as others, have been taken with the full knowledge of the IMF.

That said, the funds may well have success in litigating Icelandic authorities somewhere sometime but so far it seems the ESA challenge will not have a successful outcome for the four funds.

As to the ad campaign in Iceland it’s as ill advised and as unintelligent as can be.

Updated: I’ve been made aware that Loomis Sayles is not at all involved in the Iceland Watch campaign against Iceland. I’m sorry that my earlier information here was not correct.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

A weird ad in bad Icelandic against the Central Bank of Iceland

The libertarian Iceland Watch has posted quite a remarkable ad in Icelandic media insinuating serious corruption by a named individual at the Central Bank of Iceland with a large photo of the governor of the Central Bank Már Guðmundsson. If the four largest offshore króna holders, on whose behalf Iceland Watch seems to be campaigning, think they are winning friends in Iceland with these serious and unfounded insinuations, they should think again: the few who seem to notice it ridicule it or find it hugely upsetting.

Iceland Watch, earlier fighting Obama care and now fighting for the cause of the offshore króna holders that feel they have been wronged by the Icelandic government and the Central Bank of Iceland, CBI, has topped its earlier ads. It is now directly addressing Icelandic voters, claiming they are losing out due to the bad policies and corruption at the CBI. Whereas earlier ad was placed in media in Iceland, Denmark and the US, the latest one has, as far as I can see, only been posted in Iceland.

The four funds holding offshore króna are Eaton Vance, Autonomy Capital, Loomis Sayles and Discovery Capital Management.

So what is the Iceland Watch message, accompanied by a photo of CBI governor Már Guðmundsson, to Icelandic voters?

“Who is paying for public corruption and discriminating rules in Iceland? You do!

The decision taken by the Central Bank of Iceland to discriminate between investors so that only those of domestic origin can invest there has been criticised internationally.

According to a new study done by a research team in Britain the discriminatory policy of the Icelandic capital control hinders the creation of 30.000 new jobs and costs the nation between 5.000.000.000 and 9.000.000.000 US dollars in GDP annually.

This costs each Icelandic citizen between 15.000 and 27.000 US dollars annually.

We have now discovered that Sturla Pálsson, a highly placed individual at the Central Bank of Iceland, is being investigated in-house for alleged insider information.

The investigation of Sturla Pálsson should focus on answering some key questions: Did Sturla Pálsson use his knowledge of the recently announced legislation on capital control that discriminate foreign investors in carrying out insider trading?

Sturla Pálsson answers directly to governor Már Guðmundsson and is believed to have had access to all this information.

Media in Iceland should be asking these questions.

Capital controls and booming economy

Corruption is not an unknown theme in Icelandic politics but it will come as a surprise to most Icelanders that Icelandic officials are acting in a corrupt way to punish the four foreign funds holding offshore króna. We should keep in mind that the International Monetary Fund has followed and scrutinised policies in Iceland since October 2008.

The policy that’s such a thorn in the side of the four funds that they are willing to go to these lengths in advertising their pain internationally has also been passed with full acceptance of the IMF. Yes, the IMF isn’t infallible and perhaps the EFTA Surveillance Agency will indeed find Iceland at fault. But to think that the measures in summer came about because of corruption in Iceland seems pretty far-fetched. Shouting it from the roof tops won’t add to the arguments the funds have presented with the ESA and possibly in courts.

Saying that only domestic investors can invest in Iceland isn’t correct. This does no doubt refer to measures re offshore króna holders but it’s not a correct presentation.

Why doesn’t the Iceland Watch quote the UK research? As far as I know it comes from the Legatum Institute, connected to the Dubai-based Legatum Group established in 2006 by Christopher Chandler. The Legatum Institute recently had a discussion on Iceland and capital controls and has also published research of capital controls and anti-competitive policies. What is wholly missing is how the easing of capital controls has been done; it only focuses on the perceived harm caused by the most recent measures that has so upset the four funds.

Eh, creating 30.000 jobs in an economy with close to full employment in a country of 332.000 that needs to import people to fill jobs? And let’s put the figures in context: $5bn to $9bn amounts to 25-40% of Icelandic GDP. Is it credible that these latest measures hurting the four funds are really costing the Icelandic economy these sums annually? Intelligent readers can figure out the answers on their own.

If Iceland Watch intended to clarify to Icelanders the enormous losses they are suffering it would have helped to publish these losses in Icelandic króna, not in US dollars.

Serious allegation against a CBI official

It will be news to Icelanders that the CBI is investigating Sturla Pálsson for using his knowledge of the recent measures for his own gain via insider trading. Again, this is a statement with no verification. Given that the Icelandic media mostly ignores the ad and the reaction in Iceland is not to take this seriously at all it’s not certain that the CBI will see any reason to answer.

Pálsson has however recently been named in the Icelandic media related to breach of trust over the weekend October 4 to 5 2008: he told his wife, who was at the time the legal council at the Icelandic Banking Association (and is in addition closely related to Bjarni Benediktsson leader of the Independence Party and minister of finance) of the imminent Emergency Act. – The Iceland Watch allegation could possibly be a misunderstood echo of this recent reporting in the Icelandic media or indeed a new and much more serious allegation, unknown in Iceland.

Regardless of the basis for the allegation against Pálsson the question as it is put is ambivalent: Did Sturla Pálsson use his knowledge of the recently announced legislation on capital control that discriminate foreign investors in carrying out insider trading? – I guess this is insinuating Pálsson used his information to carry out insider trading but the sentence is so muddled that this isn’t clear at all. (The Iceland Watch text is: “Did Palsson use his position of knowledge about the recently announced capital controls legislation which discriminates against foreign investors to make insider trades?”)

Losing friends and influence… in Iceland

I’ve earlier expressed surprise that the funds think they are gaining friends and influence in Iceland through their alliance with Iceland Watch. This latest ad, apparently only directed at Icelanders, indicates a profound lack of understanding of the country they are trying to influence (tough I can’t imagine this approach will indeed work anywhere).

The photo of the ad above is my screenshot of a post on Facebook by minister of foreign affairs Lilja D. Alfreðsdóttir. Her comment to the ad is: “This attack on Icelandic interests is intolerable and what’s the aim of those behind it?” There are only few comments to the ad but some mention that this will hardly help the cause of those sponsoring it.

The ad is now also on the Iceland Watch website in English. The translation above is my translation as it gives some sense of what it looks like in Icelandic. The story is that this remarkable ad addressed to Icelandic voters is written in a version of Icelandic that resembles a Google translate text. Given that Icelanders are often quite pedantic about their language this will hardly induce Icelanders to take the ad seriously. Or as it says in one comment on Alfreðsdóttir’s Facebook page the ad is “a crime against the Icelandic language” – and that’s a serious offence in Iceland.

Updated: I’ve been made aware that Loomis Sayles is not at all involved in the Iceland Watch campaign against Iceland. I’m sorry that my earlier information here was not correct.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Iceland – lessons from an offshored country

Iceland is, in my opinion, the most offshorised economy in the world, from the point of view of how pervasive it was. The banks diligently sold offshore solutions as an everyman product. I talked about this topic as a Tax Justice Network workshop in spring. This was also the topic of an interview Naomi Fowler from the TJN recently did with me.

After the collapse of the Icelandic banks in October 2008 my attention turned to the role of offshorisation in Iceland. The banks operated in London, the Channel Islands and most important of all, in Luxembourg.

The widespread offshorisation, its effect and general lessons of offshorisation in Iceland was the topic of the interview Naomi Fowler did with me for Tax Justice Network recently, see here.

After my talk at the TJN spring workshop I wrote an article on the TJN see here.

The general lesson is: offshore creates an onshore shelter from tax, rules and regulation and thus creates a two tier society where tax, rules and regulation becomes optional for those offshored while living onshore, wether it’s in Iceland, the UK, US or elsewhere…

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

International ad campaign and un-worried Icelanders

The offshore króna holders have now taken to the international media to cry out over the unfair treatment they have been submitted to by the Icelandic government. As earlier, they have allied with a strongly libertarian organisation, Institute for Liberty, a think-tank of sort. Perhaps the ads will shake international investors but the effect in Iceland seems to be next to none and the move is clearly not intended to win them friends in Iceland. Perhaps it’s too early to tell but so far, the International Monetary Fund does not seem to side with offshore króna holders and rating agencies seem forgiving. All of this is taking place as Iceland has taken yet another step to lift capital controls, which are now almost entirely lifted for both businesses and individuals.

After placing articles in various international media recently, “Iceland Watch,” an initiative organised by a so-called think tank, Institute for Liberty with the slogan “Defending America’s Right To Be Free” has now taken a new step: placing an ad in US, Danish and Icelandic media. As mentioned earlier, DCI Group, a political PR group based in Washington acts on behalf of the funds involved.*

If Iceland will be hit with a full-force international legislation the offshore króna holders may be the last to laugh but so far Icelanders are just shrugging their shoulders at the ad campaign they don’t really understand.

A clever campaign?

It’s not clear to me who this campaign is supposed to stir and shake. Here in Iceland, very few people have any particular understanding of the issues at stake. After the very unexpected outcome of the EFTA Court Icesave ruling in January 2013 most Icelanders will feel there is little to fear from international courts.

Of course an erratic opinion, the offshore króna case is a different problem but in addition to lacking the insight the words “international litigation” will not sound frightening in Iceland. Given how few Icelanders understand the issues at stake the ads look bizarre to most Icelanders.

There is now an election campaign going on in Iceland, election on October 29 and the offshore króna situation doesn’t figure at all. Nor are the capital controls an issue since they have now been lifted on domestic entities and individuals. I’ve earlier pointed out that Icelanders didn’t really seem to notice when measures to lift capital controls were announced.

I’m not sure the campaign rocks the boat among international investors. Anyone with a nuanced understanding of the Icelandic situation will sense that the Iceland Watch claims are not really fitting the situation in Iceland but bombastic, unintelligent and wide off the mark.

Select default? Doesn’t sound like it according to IMF or rating agencies

I have earlier expressed surprise at the action taken in Iceland. Iceland is clearly exposing itself to a legal risk – there is a question of discrimination, as the offshore króna holders claim and given the good times in Iceland it’s difficult to argue for the haircut.

That said, it’s interesting to observe that neither the IMF nor rating agencies, have so far admitted to the haircut potentially being a case of selected default. The offshore króna holders might have wanted the international community to kick Iceland in place but no one is moving for them except those the króna holders muster to speak their case.

Choosing Institute for Liberty as an ally is intriguing but perhaps not surprising given that many large players in the hedge fund world have libertarian leanings.

The offshore króna saga according to the CBI

In its latest Financial Stability report the CBI spells out the offshore króna problem:

Important steps have been taken towards lifting the capital controls in recent months. In May, Parliament passed legislation on the treatment of offshore krónur, providing for amendments designed to ensure that the special restrictions applying to offshore krónur under the capital controls will hold even though large steps are taken to lift controls on individuals and businesses. In June, the Central Bank of Iceland held a foreign currency auction in which it invited owners of offshore krónur to exchange their krónur for euros before general liberalisation begins. Although most of the bids submitted in the auction were accepted, large owners submitted bids at an exchange rate higher than the Central Bank could accept, and the stock of offshore krónur was therefore reduced by one-fourth. During the summer, the Central Bank set the Rules on Special Reserve Requirements for New Foreign Currency Inflows, and afterwards there was a reduction in new investment in domestic Treasury bonds, which can prove to be a source of volatile capital flows. With the passage of a bill of legislation in October, most of the capital controls on individuals and businesses have been lifted.

This is of course the offshore problem according to the CBI and Icelandic authorities, so far neither challenged by the IMF nor, perhaps more surprising, the rating agencies. The four large offshore króna holders will beg to differ.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

European FX loans revisited – the wandering curse

The Polish “Stop BankingInjustice Association” is one of many grass root organisations that have sprouted in many European countries in the last few years, due to FX loans: retail lending to people only with income and assets in their domestic currency. Today, the Polish organisation held a meeting in the Polish Parliament in order to explain the politicians and others the status of FX loans affairs in Poland and elsewhere in Europe, with speakers inter alia from Italy, Spain, Ukraine, Hungary and Iceland. – Interestingly, only in Iceland have the FX loans been dealt with, fairly speedily though never without pain for the borrowers.

The problems of FX loans in Iceland came up fairly quickly after the banking collapse in October 2008. No wonder, the króna had collapsed and everything linked to the currency rates was rapidly rising. To begin with, I was not particularly interested, felt that the borrowers should have been aware of the risk, not much to do. However, after getting an email from a Croatian FX borrower, telling me of the plight of FX borrowers in her country, I started looking at these loans in a wider perspective.

FX loans: a wandering curse for more than 40 years

In short, FX loans have been a wandering curse, going from one country to another, for over forty years. There is abundant evidence that FX loans are utterly unsuited as a standard financial product for ordinary people with no income in FX and no buffer.

I have earlier pointed out this wandering curse element of FX loans, how they have wandered from country to country – Australia in 1980s, New Zealand in the 1990s, also in Austria, Germany, Italy and then after 2000 in Iceland and many countries of Central and Eastern Europe – is quite remarkable and also the fact that the pattern is always the same: it ends in tears. This is not a case of this time it’s different; indeed, it’s always the same.

Lessons learnt long time ago, yet banks keep offering FX loans

This statement from the Australian FX loan saga, captures the risk perfectly: “…nobody in their right mind, if they had done a proper analysis of what could happen, would have gone ahead with it (i.e. FX loans).” And in 2013 the Austrian National Bank warned: “Foreign currency loans to private consumers are not suitable as a mass product…” This was the lesson that the Austrian Finance Market Authority, FMA had already drawn in 2008 but only in 2013 did it state this so clearly and unequivocally.

The FX lending pattern is always the same: the banks have the need to hedge themselves, for various reasons (usually because their financing is in some way FX linked) so they offer retail FX loans. Because the interest rates are lower than the domestic rates people can borrow more, thus in a certain sense creating sub prime lending, from the point of view of the capacity to service loans in the domestic currency.

FX loans, sub prime aspects and the unavoidable shock

Given that the loans normally stretch over years and even decades and FX fluctuations happen quite frequently, it’s clear that the circumstances at the time when the loan is issued are unlikely to stay unchanged. It can be argued that borrowers with FX assets or available funds can profit from FX loans over the lifetime of the loan. That however is not the situation for the majority of FX borrowers who at the outset borrow what they at most can service.

In all countries, where FX retail loans have become widespread, the pattern has always been the same: first, the borrowers are castigated for taking loans they then can’t service. Then, the sub prime lending aspects appear: banks haven’t really informed the clients properly, minimised the risks etc and haven’t done the due diligence as to what would happen to these clients should the currency rates change. The question how far authorities should go in protecting people is certainly justified but all European countries do indeed have a strong focus on consumer rights and scrutinising the banks’ information and behaviour with regard to FX loans should be obvious.

The ruling of the Árpad Kásler case, in the European Court of Justice, ECJ, ECJ C?26/13 in 2014 turned the tables against the banks and in the favour of borrowers. Slowly slowly, the sub prime aspect, the insufficient information and the fact that these loans are normally not really FX loans but FX indexed loans has also mattered.

Iceland and elsewhere: FX indexed loans illegal, not FX loans per se

Iceland is the only country in the recent FX loan saga where the loans have sytematically been written down. In that sense, the Icelandic FX loan saga is success from the point of view of hard-hit borrowers. But it didn’t happen over night, it took time: the króna collapsed in 2008 and kept falling until late 2009. The two first Supreme Court rulings, testing the validity of the loans came in summer of 2010. Only by the end of 2014 and after ca. 30 Supreme Court rulings had the loans been recalculated.

The Supreme Court ruled that FX loans are not illegal but the FX lending isn’t really a FX lending but lending in domestic currency where another currency or a combination of more than one currency set the interest rate.

At the conference there were FX loan stories from different European countries, reflecting the state of affairs in the respective countries. In general it can be said that courts, taking note of the Kásler ECJ case, have at times ruled in favour of borrowers but it differs how willing courts are to take note of the precedence.

In Italy, FX loans cases have been in the courts for five years but have yet to reach a verdict in the lowest court. In Ukraine, there has been a moratorium on enforcing FX loans collaterals since 2014.

All in all, what is generally needed is an acknowledgement of the fact that FX loans all follow a similar pattern, no matter if it’s Australia in the 1980s or Spain in the 21st Century. FX loans are a type of sub prime lending and not a product fit as a general product. Until banks and authorities draw the same conclusion as the Austrian central bank and the Austrian Financial Services Authority in 2013 banks can go on selling these poisonous product and pretend to be surprised when it goes, so predictably, wrong.

FX loans are a great interest of mine, see my earlier blogs on FX loans, inter alia here and here.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

The ELSTAT case takes a new turn – IMF and Eurostat staff implicated

Anyone who has followed the Greek crisis will be familiar with stories of insane corruption and absurd clientilismo. As the criminal prosecution of the former head of ELSTAT, Andreas Georgiou, shows the Tsipras government prefers scapegoats rather than facing painful truths about the past. Now, also foreigners working for the IMF and Eurostat are being implicated in a new criminal case against Georgiou and his colleagues.

Before the January 2015 elections, which brought Alex Tsipras and his Syriza party to power, Tsipras had been adamant on the need to tackle corruption. Once in power this discourse ebbed out. Now Tsipras and his government is watching a so-called independent judiciary persecuting the former head of ELSTAT, the Greek statistical bureau, Andreas Georgiou, who demonstrably turned ELSTAT and statistics around after a decade of falsified statistics.

The latest and most remarkable turn in the ELSTAT saga is a new criminal investigation, not only focusing on Georgiou and two of his colleagues, whose cases have all been dismissed more than once (see my detailed ELSTAT saga, written after I visited Athens in June 2015) but also on the IMF and Eurostat staff.

As I have earlier pointed out the ELSTAT prosecutions are a test of the new Greece trying to be born after the crisis: as long as ELSTAT staff and now foreigners striving to bring clarity to statistics, one of the absolute pillars of any modern country, are being prosecuted Greece is failing to free itself of political corruption. The fact that the Greek state is yet again trying to prosecute civil servants who did their jobs admirably is a sign of something seriously wrong in this country.

To Icelog Georgiou says: “The prosecutions within the borders of the European Union of official statisticians, whose work has been thoroughly checked and fully validated by the competent European Union institutions for six years in a row, should be a cause of great concern given their important precedential significance at a European Union level and an international level as well.”

A new criminal investigation of ELSTAT directors – as well as IMF and Eurostat staff

The latest move was brought on by the chief prosecutor of the Greek Supreme Court, Xeni Demetriou. As a deputy prosecutor of the Supreme Court until June 2016, Demetriou had been responsible for proposing in September 2015 to annul the last acquittal decision regarding Andreas Georgiou and his two colleagues. In the event, the Supreme Court published a decision in August 2016 accepting that annulment proposal and referring the case back to the lower court so that the latter reconsider its decision.

Amazingly, in this latest move, Demetriou as chief prosecutor, initiates an additional, brand new criminal investigation. The case was brought following a publication of two articles in the Greek newspaper Dimokratia at the end of August; the articles were introduced with photos of Andreas Georgiou, as well as of Eurostat and IMF officials.

Apparently based on emails and other sources, Dimokratia focuses on the 2009 deficit calculation. The newspaper’s coverage doesn’t seem to add anything but clamours statements such as “The Mafia of the Deficit,” to what was earlier investigated and then dismissed in previous attempts to bring Georgiou and his colleagues to court. The magazine reported inter alia of burglaries to allegedly make the case against the ELSTAT directors go away, postulating that they incriminate Georgiou and his colleagues.

This new prosecution does not only involve ELSTAT directors but goes further, involving IMF and Eurostat staff. Dimokratia claims that Eurostat’s Director General Walter Radermacher forced Greece to use statistical methods not used in any other country, directly causing the high deficit. The grand scheme was to force Greece to pay foreign banks, or as stated by the magazine: “the dirty plan of the destruction of Greece was planned and executed with distorted data so that the foreign banks can be repaid completely.”

One of the Dimokratia sources is Nikos Stroblos, a former director of the national accounts division of Greece’s statistics office during the years of fraudulent reporting. As so often pointed out on Icelog: quite extraordinarily, Georgiou and ELSTAT directors who brought the reporting of statistics to international standards, are being hounded in Greece but nothing has been done to investigate what went on during the years of false reporting.

International support for Georgiou and his ELSTAT colleagues

Eurostat and the European commission have earlier voiced concern over the turn of events in Greece. On August 24 Commissioner for Employment, Social Affairs, Skills and Labour Mobility, as well as European statistics, Marianne Thyssen was adamant that the independence of ELSTAT and the quality of its statistics were essential, adding that from the point of view of the Commission and Eurostat “it is absolutely clear that data on Greek Government debt during 2010-2015 have been fully reliable and accurately reported to Eurostat.” The Commission called “upon the Greek authorities to actively and publicly challenge the false impression that data were manipulated during 2010-2015 and to protect ELSTAT and its staff from such unfounded claims.”

The International Statistical Institute, ISI, has earlier voiced great concern for the course of events in Greece and has recently, yet again, called upon “the Greek authorities to actively and publicly challenge the false impression that data were manipulated during 2010-2015 and to protect ELSTAT and its staff from such unfounded claims.”

Further, ISI, “is extremely concerned about the persecution/prosecutions of Mr. Andreas Georgiou, Ms. Athanasia Xenaki and Mr. Kostas Melfetas for doing their work with the highest professionalism, integrity and adherence to international standards and the UN Principles, regardless of political pressure. It is inconceivable that such work, independently verified and approved in line with international standards, could lead to prosecution, and even successful prosecution of those responsible. Instead, such work should be praised!”

Persecution due to correct statistics shows the Tsipras government’s ties to the past

So far, none of this has had the slightest effect on the Tsipras government.

As pointed out recently on Icelog, the case against Georgiou and his colleagues, and now also involving IMF and Eurostat staff, is a test of the Greek government’s commitment to change and to acknowledge fraudulent behaviour in the past.

As pointed out by Tony Barber in the Financial Times on September 12, Tsipras is “yet again testing his EU partners’ patience. He is not only dragging his heels on economic reform, but is letting a criminal prosecution go ahead in a blatantly politicised case against Andreas Georgiou, a former head of the national statistics agency.”

In his review of “Game Over,” ex minister of finance George Papaconstantinou’s book on his six years in politics, Peter Spiegel notes the significance of the ELSTAT case and the Greek tendency to find scapegoats: “… it is Greece’s abiding myth that somehow the day of reckoning was avoidable. Papaconstantinou’s highly readable book makes that falsehood clear. No doubt Mr Georgiou’s trial will do the same.”

As long as Alexis Tsipras and his government continue to persecute the ELSTAT directors it is clear that the old bad ways and corrupt powers are untouched and still ruling.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Iceland back to A series, A3 to be more specific

For a long time Iceland didn’t know anything but A from the credit rating agencies. As so many other things the As evaporated with the banking collapse in October 2008. Lately, everything has been going swimmingly for the Icelandic economy except the A rating has proven to be elusive. Now, Moody’s has fixed that: Iceland is back to A3, outlook stable. Icelandic politicians and central bankers will nod approvingly, they feel the A should have been there a while ago; the only group, which might feel perplexed are the offshore króna holders who think they are being short-shrifted in spite of the boom.

Icelandic politicians and central bankers feel that Iceland has been doing much better than reflected in the rating agencies’ ratings. This is partly acknowledged by Moody’s (emphasis mine):

Iceland’s rating trajectory has lagged the improvement in some of its core fundamentals since the financial crisis, because of the residual risks posed to economic and financial stability by the complex process of removing the capital controls first imposed in 2008. The second driver for the upgrade of Iceland’s government rating to A3 at this point in time reflects Moody’s expectation that the phasing out of capital controls will proceed smoothly to completion and therefore not disrupt economic and financial stability.

Moody’s argues that Iceland now is far into liberalising the capital controls – the third step, lifting controls on Icelanders and Icelandic entities, is now in sight, having been announced recently. As I pointed out recently, the lifting now longer seems to capture Icelanders, the announcement went largely unnoticed.

As to offshore króna holders Moody’s isn’t worried either:

The first two stages of the liberalization process are now complete. The resolution of the failed bank estates was completed in late 2015. In June 2016, the central bank auctioned part of its FX reserves for ‘offshore krónur’ (mainly non-resident-owned ISK assets trapped when capital controls were imposed in late 2008 at the time the old banks collapsed), thereby further reducing the overhang of such assets. Moody’s view is that while the few remaining holdings of offshore krónur are sizeable at 8% of GDP, the event risk they pose for Iceland’s external position is limited. The liberalization of capital controls on residents will begin immediately following parliamentary approval of the relevant legislation. A further easing of controls on residents is scheduled to take place on January 1, 2017.

If the offshore króna holders thought the rating agencies would favour their points of view, inter alia interpreting the offshore króna measures as a selective default as has been heard from the offshore króna holders, or would be likely to calculate litigation as a risk, that doesn’t seem to be the case. In Iceland, things are going swimmingly, the economy is booming and at long last Moody’s as the first of the rating agencies has acknowledged it. So far, so good.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.