Archive for 2010

Another ex-Kaupthing manager in custody

Magnus Gudmundsson, earlier the head of Kaupthing Luxembourg, now the manager of Banque Havilland owned by David and Jonathan Rowland, has also been imprisoned after the Office of the Special Prosecutor in Iceland asked for a custody of two weeks over him. The charges that can be expected to be brought against Gudmundsson and Hreidar Mar Sigurdsson could possibly bring an imprisonment of at most eight years if the two will be convicted. The offices of KPMG and PWC in Reykjavik have also been searched in connection with the investigation.

PS It now seems that Gudmundsson was brought in for questioning but isn’t being held over night like Sigurdsson. What happens later is still unclear. A custody might be demanded Frid.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Kaupthing’s ex-CEO in custody

Ex-CEO of Kaupthing Hreidar Mar Sigurdsson has been imprisoned after the Office of the Special Prosecutor in Iceland requested a two weeks’ custody for Sigurdsson at the Reykjavik District Court. The Court will rule tomorrow on whether the request will be granted. Sigurdsson is being investigated for various financial malpractice, i.a. market manipulation. It’s most likely that Sigurdsson is only first in line – other managers, board members and major shareholders might well hear from the OSP.

The news has created quite a stir in Iceland. It’s been known that the OSP has been investigating Kaupthing. The fear has been that the cases might prove too big and complicated but no doubt the advice given by the Norwegian French ex magistrate Eva Joly has helped the staff at the OSP to find fruitful directions in the investigation. But it’s not only in Iceland that Kaupthing is being investigated.

The Serious Fraud Office in London also has the collapsed bank under investigation and there is a close collaboration between the countries. Earlier this year, the OSP requested house searches in Luxembourg where 40 policemen conducted searches for three days, mainly concentrating on the now Banque Havilland, earlier Kaupthing Luxembourg, bought by the UK financiers Jonathan and David Rowland. The Rowlands are thought to be unconnected to the alleged fraud.

Now that the OSP has demanded custody for the ex-CEO the question is who will be next. The recent report by the Althingi Investigative Committee threw light on the complicated affairs between Kaupthing’s management and its main shareholders, Agust and Lydur Gudmundsson, Olafur Olafsson and foreigners such as Kevin Stanford and Robert Tchenguiz – wealthy men who became even more wealthy as favoured clients and shareholders of Kaupthing. The Report seems to indicate highly questionable dealings and clear signs of market manipulation.

The interesting angle of the Kaupthing story is how the bank grew exorbitantly in close collaboration with its core shareholders generating huge sums from proprietary trading, fees and joint ventures with the relatively small group of big clients. The bank also serviced clients like the Candy brothers, the London-based property developers and the Russian oligarch Alisher Usmanov, the metal magnate and owner of Arsenal.

The question that many Icelanders will be asking today is if the meteoric rise of Kaupthing and its main shareholders and clients was all too good to be true. When rapid growth and bad loans go hand in hand in a bank it’s often taken as a possible sign of fraudulent behaviour. I’ve pointed out earlier that it’s difficult to find any parallel to the Icelandic banks except Italian Mafia banks. The outcome of the Kaupthing investigation and other ongoing investigations remain to be seen – it will take a while until Icelanders know for sure if their entire banking system was taken over by a group of bankers and businessmen using fraudulent means to enrich themselves.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Living the Icelandic Kreppa

By guest contributor Michael Schulz. A social scientist who has worked for 30 years as a humanitarian manager in development, natural disasters and conflict on missions for the Red Cross in Africa, Asia, the Middle East, Russia and Trans-Caucasus and was i.a. based in Ramallah for two years. The last 5 years Michael was a diplomat with a Red Cross delegation in New York, accredited to the UN. – His Icelandic connection is through his partner who gives Michael an ‘Icelandicness’ and the authority to speak of Iceland though seen through his European eyes. Michael takes a keen interest in all aspects of the ‘Kreppa’ (Icelandic for ‘crisis’) in a philosophical, historical, political, socio-economic and cultural context.

Living in Iceland, as pointed out earlier on Icelog, ‘it’s clear that,’ as pointed out here earlier, the collapse of the Icelandic banks ‘wasn’t an event but a process that hasn’t yet come to an end.’

What I’ve been missing in discussions are much more conscious and informed references to the process, or, perhaps even more accurate, the accumulation of many events that make up the various processes we’re witnessing. (Far from being a linguist I do wonder if possibly the notion of creeping could be inherent to the meaning of Kreppa, the Icelandic word for ‘crisis’ – a crisis in motion, a process?)

This is not to say that the SIC (Special Investigation Commission) in its by now famous Black Report, did not revisit the history that lead up to the collapse of the banking sector. Or that politicians were and are not in the art of making optimistic prophecies on account of some yet unknown future, trying to talk an end to crisis into existence. All quite to the contrary.

Of course, the length of this crisis does matter, and to none more than those worst affected, those with acute human and humanitarian needs. Of course, debt and interest accrue every day while credit/debt payments are delayed. But length as a measure of a process or processes, as if a timeline of crisis, does not suffice to the understanding of Kreppa. Besides length there have to be also other directional and qualitative measures of depth, width and height. At least I experience Kreppa multi-dimensional during my physical and virtual Rambles in Iceland. As you so rightly say it is: there’s an ongoing collapse.

Isn’t it true that risks are omni-potential and omni-present? That crisis reveals itself in sudden onset, and that its unraveling progresses with a time lag, in slow motion, almost invisible, felt only over expanses of time? Trends continue, further spiraling downwards, further into the depth of Kreppa. A friend, working with an NGO, reports that the numbers of families in need of (food) support remain staggering and that needs are real and serious. Countless people are caught in the web of toxic loans. How to manage credit card debts in times of Kreppa?

As point out earlier on Icelog two “Sparkassen” (building societies) went into receivership mid April. Last week, I heard that pension funds had to cut back on pensions. A few weeks ago two councils went into receivership; reportedly other eight communities hover on the brink. Quasi on the 1st of May, Labour Day, statisticians report: the number of employed persons was 163,900 and unemployed persons were 13,600. The unemployment rate was 7.6%. The number of unemployed persons increased by 900 from the first quarter of 2009 and the number of employed decreased by 1,600. Never mind the verbal logic, the message is that unemployment increased during the 1st quarter 2010.

A business friend called from abroad alarmed by the fact that already meager hard currency quotas had been further restricted, holding hostage her investment capital, Icelandic Kronur, on her Reykjavik bank account. More still: on the 3rd of May, statisticians reported that 292 companies in Iceland went bankrupt in the first quarter of 2010, according to new information from Statistics Iceland. This is an almost 12% increase compared to the first quarter of 2009, when 261 companies went bust.

One could carry on and on. But, so I believe, thus far the facts augur enough ill to state q.e.d. (or quod erat demonstrandum): the Kreppa is moving on to new depths claiming a daily toll on individuals and all sectors of society. The next question might then be whether or not it is gaining width? Perhaps that‘s only a hypothetical question as above stated facts illustrate that the Kreppa has and continues to spread while growing deeper. What started – and continues – in the financial and monetary sectors has taken firm hold of the economy. Austerity measures in the fiscal sector are increasingly and negatively affecting all other sectors by means of tax hikes and budget cuts, not least the public domain: social, health, education, culture, et cetera. People, individuals are hurting.

If Kreppa gains length, depth and width, what about its height? When will measures of crisis resolution gain traction? When will the Kreppa peak? What will the consequences be? No, I will not join the choir of prophets. Yes, the Kreppa in its directedness and dynamics is a process. And, as said, it is also an accumulation of events, and there are, along the way, events that will result in partial resolutions. The Black Report, for example, seems to feed into the work of the Special Prosecutors Office. Justice shall be sought in cases when neglect or criminal intent prevailed. There shall be an agreement concluding the Icesave scandal and the like.

But, apart from legalistic proceedings in selected events, what are the answers and solutions to the process as if the totality of events? I remain dumbfounded by, for example, politicians who seek patchwork answers, solutions in conventional doctrines of salvation. Is it done with vague blanket apologies? Temporary resignations? Displays of ignorance? Escapism or denial? Finger pointing, singling out one as opposed to the other? Change image as if solely a matter of PR? Is it done with a hastily rewritten legislation here and there, changing a few rules and regulations, or job descriptions, or redrafting the President‘s terms of reference, or … ? Is it desirable to simply work at re-establishing the status quo ante allowing only a few erratic corrections? Shall self-serving elite allegiance again matter more than competence and merit?

True, there are exceptions in all walks of public office, academia and media, or the corporate sector for that matter. But they are too few versus. Some of the few have voiced calls to look at the problem in its entirety, to take a holistic view. I am convinced that only a full understanding of the Kreppa as a process will allow an understanding as to why and how it has and continues to (holistically) impact the society at large, all sectors, the state and the nation because. While not convinced, I would not be surprised if a full understanding of Kreppa would turn out to stand synonymous with a Kreppa of statehood.

Again a few have called to join the EU as a member and to adhere to the Euro. A call by the few against the objections of the many, according to pollsters. Another call is made for a constitutional assembly. Are these timely calls in the absence of a full understanding of Kreppa and its diverse, multi-facetted impacts? What are the objectives? Certainly, the EU is not a Kreppa repair workshop, the Euro not a tool to salvation. What does a constitution matter if its spirit doesn‘t become a reality because it misses reality? Could such initiatives defeat good intentions because the Kreppa-process falls short in understanding?

In Iceland I now sense, rightly or wrongly, a desire to reach a holistic solution to Kreppa albeit without a holistic understanding. Not only the politicians have failed this society in the past but also they treated the Republic badly. Res publica, public affaires, were too often handled by elites excluding the Republic. Let us hope the politicians will now assume responsibility and leadership and conduct a public discourse for all to understand Kreppa and what the options are.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

William Black on Iceland

Prof. William K. Black is in Iceland these days, giving two public lectures. He was also interviewed on a political talk show last Sunday. Mar Wolfgang Mixa, an Icelandic economist, has posted an extensive blog in English about Black and his views on Iceland here.

Black has a great track record as a regulator and a scholar specialising in financial fraud. He recently testified before the House Financial Services Committee on Lehman and gave a memorable account of Lehman’s demise and has been widely interviewed on Lehman and Goldman Sachs case.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

The ongoing collapse

Now, eighteen months after the collapse of the three banks – Kaupthing, Landsbanki and Glitnir – in October 2008 it’s clear that their collapse wasn’t an event but a process that hasn’t yet come to an end. A case in point is the Icelandic system of building societies, ‘sparisjóðir.’ Iceland had a strong system of building societies, similar to the German and Scandinavian ‘Sparkasse.’ Last week, two building societies were taken over by the state. Out of ca twenty societies a decade ago, only two are now left as independent institutions. The rest has either been taken over by the state or merged with one of the banks. Sadly, a financial system, closely linked to communities around the country, has been wiped out. The loss of this backbone of the local economy will, no doubt, make it much more difficult for small businesses all over the country to get financial service tailored to their needs.

The building societies, owned by locals, were run like cooperatives. The members owned what they put into the society and got a dividend of this part only. In 2000 these owners owned 15% of the societies’ equity. In 2002, laws on building societies were changed, enabling the owners to sell their part on the market. From this time the societies were allowed to become listed companies though only one of them eventually did, in 2007 as the tide of easy money was turning.

These changes were made around the time when the banks were privatized. In the following years the banks and their biggest shareholders sought to influence the building societies in their ever-greater need for money, manipulating their managements in the interest of the banks. Many building societies turned into hedge funds gambling with shares in the banks and companies like Exista and FL Group. At a closer look, the profits of the building societies didn’t stem from the banking activities but from shares. The building societies turned into satellites of the three banks, eventually doing a lot of repo loans with the Central Bank as the credit crunch struck.

Together, the building societies owned a bank, Icebank, that threw itself head on into unsustainable investments, i.a. some of the most deranged property projects abroad. One of them was a redevelopment of a hotel in Florida, Longkey, where Icebank eventually lost $8,5m. The key person was an Icelandic investor, Karl Wernersson, who was a principal shareholder in Glitnir before he sold to Jon Asgeir Johannesson. Clearly, fast-talking foreign developers who promised riches and delivered nothing led the Icelandic investors badly astray.

Around Christmas I spoke to a manager from one of the two building societies still standing – one is in the West of Iceland, the other in the North. He complained that competition was now tough since his society was competing against state-funded building societies. As to why his fund was still standing he said that the fund had mostly steered clear of investing in shares. And he and his colleagues had stayed away from making business with people from Reykjavik. ‘At one point,’ he said, ‘we had some clients from Reykjavik but our experience of making business with them wasn’t good.’ – Sometimes, it pays to stay close to one’s roots.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Goldman Sachs: who was allowed to profit and who to lose?

From the Icelandic perspective SEC’s charges against Goldman Sachs raise interesting questions. In the Icelandic banks some shareholders and companies were allowed to make huge profits and to borrow exorbitant amount of money against the interests of other shareholders and other clients.

The charges against Goldman Sachs indicate that some clients and the bank itself profited from Abacus, the fund at the core of the charges. I would be interested in knowing who exactly was allowed to make profit and who was allowed to lose, also in possibly similar investment schemes. The answer to this question would go a long way to map the power sphere of Goldman Sachs.

PS For those who want to understand what SEC charges agains Goldman Sachs are about two articles by Steve Randy Waldman clarify the case, even to the layman; Goldman-plated excuses; L’affair Goldman in price/information terms. Waldman blogs at Interfluidity.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

The Icelandic banks: a case of a gigantic market manipulation?

As the crisis hit in 2007 the Icelandic banks could not make use of margin calls because their largest debtors seriously put the banks’ position at risk – a typical example of what happens when the power in a bank’s client relation is reversed: the bank loses the stronghold on a client that has borrowed far beyond all sensible and justifiable limits. I’ve already pointed out the similarities to corrupt Italian banks. But the banks were also seriously hampered in making margin calls among smaller clients who had pledged the banks’ own shares.

In reality, many of the loans against the banks’ shares, particularly prevalent at Kaupthing (and not only towards the end) were no ordinary loans. It’s more precise to describe these transactions as ‘parking’ – the banks, especially Kaupthing, didn’t want just whoever to own shares so they ‘parked’ the shares with friendly partners. The banks wanted to control the shares, originally perhaps to avoid a hostile take-over, later to keep the share price at a level that the bank itself found satisfactory.

At Kaupthing, many employees borrowed from the bank to buy Kauphting shares with the shares as collateral. These sums were often far beyond what the employees’ salaries could reasonably justify. There are indications that the bank used pressure to induce the staff to make use of this offer that the bank said were ‘risk-free.’ In late 2002, as the share-price started to fall the bank couldn’t make margin calls on these loans thus leaving the employees who mostly didn’t have their shares in a limited liabilities holding company in a limbo. Just before the bank collapsed these employees were released of their responsibility for these loans. The legal wrangle on that decision is still unsolved. On the whole, these loans appear a horribly cynical action by the bank’s management that literally gambled with the employees’ future – a modern version of slavery.

This share ‘parking’ and other means the banks apparently used to keep up their share price is now under investigation in Iceland as market manipulation. It seems these tricks might have started well before the collapse in October 2008. If this proves to be the case investors and bond holders might well see a case for legal action against those responsible. At least one of the banks’ large creditors is preparing a case on these grounds.

It’s also interesting that the Serious Fraud Office is investigating Kaupthing with a team of eleven people. A possible market manipulation is most likely a part of that investigation.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

The ‘home-knitted’ crisis

‘How far are you in reading the report?’ is a question that everyone asks in Iceland these days. The report in question is of course the report of the Investigative Commission, published April 12. The 2600 pages offer a lot of information to mull over regarding the banks and the public sector, including the Financial Services Authority, FME and the Central Bank.

One of the most important findings is that the banks didn’t fail because of evil foreigners – hedge funds, the UK Treasury or the FSA or any other foreign force. The banks collapsed because they were allowed to grow too quickly. In addition, there were some serious anomalies within the banks: the main shareholders used ‘their’ banks as their personal ‘piggy-banks’, the same small clique borrowed from all the banks and the banks made use of cross-financing to finance their own shares and shares of the other banks.

The report shows clearly that the banks’ principal shareholders were also the banks’ largest borrowers. At Kaupthing, the second largest debtor was Exista, a listed company ruled by Agust and Lydur Gudmundsson. Robert Tchenguiz had been on the board of Exista since early 2007 and was, as the bank collapsed, the bank’s largest debtor, with a debt of ISK200bn, ca €1,7bn, which also makes him the largest single debtor in Iceland. – In Iceland, foreigners with strong ties to Iceland are called ‘Íslandsvinir,’ ‘friends of Iceland. Tchenguiz’ strong ties to Iceland add a new meaning to the word ‘Íslandsvinur.’ – Another large debtor in Kauphing and a large shareholder is Olafur Olafsson who still owns the shipping company Samskip.

Bjorgolfur Thor Bjorgolfsson and his father, Bjorgolfur Gudmundsson, were the main shareholders at Landsbanki. Bjorgolfsson was also the main shareholder in the investmentbank Straumur. In total, father and son owe Landsbanki over ISK200bn which is more than Landbanki’s entire equity. At Straumur father and son are also the bank’s largest debtors.

At Glitnir, the largest borrower was Baugur and related companies/investors. Jon Asgeir Johannesson, his wife Ingibjorg Palmadottir (who miraculously still owns the 101 Hotel in Reykjavik), his father Johannes Jonsson as well as his mother in total owed ISK250bn to the banks. Related to Johannesson is his business partner for many years Palmi Haraldsson. From 1998 Johannesson had been trying to become a principal shareholder in an Icelandic bank but it wasn’t until mid-year 2007 that he and Haraldsson finally got hold of a bank, Glitnir. Their borrowing, already high, accelerated. As the bank collapsed Baugur and related companies owed more than ISK250bn, equal to 70% of the bank’s equity base.

In addition to using the banks as their personal piggy-banks, the largest shareholders seem to have swayed the investments of the banks’ money market funds towards their own companies and the banks themselves. Consequently, the funds lost heavily. The Icelandic money market funds never operated as normal MMFs, were i.a. not independently rated. In addition, the funds were marketed as ‘as save as current accounts, only with better interests.’

The management of the banks’ MMFs is a chapter in itself in this sad story. In a Glitnir fund a politician from the Independence Party was on the board. Whether it mattered in the end is an open question but the state did put money into the funds in order to minimize the losses – an action that still raises questions as to political influence in the collapse and why these funds were helped thereby helping many individuals, typically middle class professionals.

There is no doubt that quite a number of court cases will arise from the collapse of the Icelandic banks. The other day, I was walking towards the pond, ‘Tjornin,’ in the heart of Reykjavik when I saw a firework exploding over the hill beyond the pond. It reminded me that when I was in Naples in the summer of 2007 there were bursts of fireworks almost every day. A Neapolitan friend explained that it was customary to celebrate the release of a prisoner with fireworks – and that was happening all the time because of an amnesty to diminish the prison population. Since no one has yet been put in prison because of the banks this single firework can’t have had anything to do with a prison sentence. Perhaps Icelanders, who are the most firework-happy population on earth on New-years eve, will one day learn to use fireworks to express relief when those responsible for the banks’ collapse will be convicted.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Eyjafjallajokull: blinking into the crater

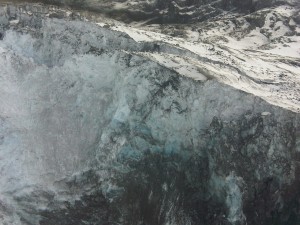

I had the opportunity today, at 7pm, to fly in a helicopter up to Eyjafjallajokull to visit the crater that’s cancelling flights all over Europe. The trip to the crater took about 10 mins. As we came flying up the volcano we saw directly into the crater, the ash, fumes and steam bulging up.

Just in front there was this pristine white tip of snow.

Close up, there was ash over the glacier, everything black and grey except the blue sky beyond.

Flying back, we glided down the glacier, following a crevice formed by floods of warm water that melted as the eruption started. The water ran under the glacier causing parts of it to collapse, forming crevices as if the ice cap had been torn apart.

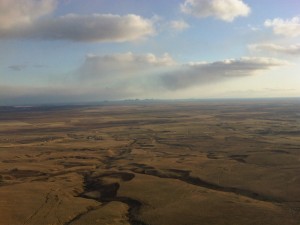

When we came down to the flatland the Vestmanna Islands seemed only a stone’s throw away, resting on the ocean under the tip of the ash spreading out over the Atlantic. Heimaey, the biggest island, erupted in 1973 – the island was evacuated over night and no one lived there for the best part of the year. Those who returned say that live wasn’t the same afterwards. Farthest to the right is Surtsey, formed on the ocean in an eruption 1963-67 that began underwater. As you can see the surface of the earth is cut and torn by rivers and floods.

Just before landing by Hotel Ranga with the plume out by the horizon.

This is the view I had with my dinner at Hotel Ranga, at around 8.50pm. Earlier, the volcano drew a deep breath with only white steam rising up from the crater. At this time, the lightening that plays around in the steam all the time was visible from time to time. – I sent the photo to someone who is in Germany and who had planned to fly back to London Thursday evening. He remarked that this eruption certainly didn’t look like forces of nature strong enough to bring halt all flights in Europe.

And that’s true. Here, so close to the volcano, life goes on as if nothing had happened. So far, it’s not a catastrophe – but the outlooks is different if this goes on for long. It will make life difficult i.a. for the farmers living right under the plume where the ash falls. The earth there is covered with what looks like pale grey snow.

And this is the tip of the plume lit up by the setting sun – like a tongue stuck out at Europe, the river Ranga floating by. A serene evening under the volcano.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Under the volcano – the source of the ash

Little did I know some weeks ago when I booked a room at Hotel Ranga that I would have an eruption outside my window. The hotel is ca 20 km from Eyjafjallajokull, the glacier now erupting and putting Europe to a standstill.

I left Reykjavik this morning. I didn’t realise it at the time but the top of some clouds, visible from Reykjavik, were indeed the top of the plume. Already on the heath East of Reykjavik the glacier and the plume hovering over it were visible. Below are photos that I took as I approached the volcano.

Eyjafjallajokull seen from Selfoss, ca 50 km from the volcano.

The horses didn’t seem to mind the volcano ca 20 km away. It’s a cold day today but the air clear and the view spectacular. The volcano is ca 1500m high, the steam and ash around 8km.

This is the view from the hotel. Around 4pm the eruption stopped…

… but only while the volcano took a deep breath: ca 20 min later it was spewing ash and steam again. The dark blanket to the right is the plume of ash that drifts over the sand South of the glacier and then out over the Atlantic, over to Scotland, England and down the continent.

This is only a small eruption on Icelandic scale – and yet it’s powerful enough to halt the life of millions of people all over the world. A friend in Paris was going to a concert tonight but the concert was cancelled because the orchestra from Lisbon hadn’t been able to fly to Paris. Another friend is stuck in Cincinnati, can’t get back to England. But here, close up to the volcano all is peaceful, the view is spectacular and it’s as if nothing had happened except nature following its course.

The word going around in Iceland now is that the last wish of the Icelandic Financial System was for its ashes to be spread out over Europe…

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.