Archive for 2010

A PS to the Johannesson Freezing Order

Part of Glitnir’s arguments for the international freezing order against Jon Asgeir Johannesson relates to a €13,6m loan to 101 Chalet, a company owned by Johannesson and Palmadottir, his wife and ‘alter ego’, to use the phraseology from the Glitnir charges brought in New York against the couple together with five others. An interesting addition to this story is that according to the Glitnir QC Richard Gillis Johannesson claims that his sister, Kristin Johannesdottir who’s been a director in many companies related to her brother, signed a guarantee for the loan, without his knowledge.

The report of the Investigative Commission points out that ‘innumerable companies’ are related to Gaumur, the holding company of the Johannesson’s family, with extensive ties to offshore secrecy jurisdictions. 101 Chalet is one of them, owned by Johannesson and his wife. The 101 Chalet loan was a key argument in Glitnir’s motivation for the freezing order since it’s both shows how intertwined the couple’s assets are and how assets were moved between companies and eventually beyond the reach of creditors.

Instead of insisting that the Johannesson companies sold assets and paid up debt during the difficult times of August 2008 Glitnir issued a 13,6m loan to 101 Chalet to buy a chalet in Courchevel. At the time, the owners of 101 Chalet claimed that a loan from a foreign bank was coming their way. Glitnir’s management only accepted though to issue a bridge loan for three months and sought to secure its interests with a letter from the chalet-buyers that the chalet would be sold if the other loan hadn’t materialised in three months and the Glitnir loan repaid. In addition, Glitnir had collaterals in 101 Chalet and in Piano Holding, a Panama company holding the 101 Heesen yacht (sold by the Kaupthing Luxembourg administrators, Banque Havilland, last year). When the loan wasn’t repaid it transpired that the Piano Holding guarantee was worthless from inception because the 101 yacht had been encumbered.

In addition, Glitnir sought a guarantee from Gaumur, signed by Johannesson, his sister and his father.

Three months later, Glitnir had collapsed and no other loan had been secured for the chalet. However, the chalet wasn’t sold until more than a year later. During the freezing order case Johannesson admitted that the 101 Chalet loan contract had been breached.

As with so many of the loans to the Icelandic banks’ chosen customers the loan to 101 Chalet was passed on to another Baugur company, BG Danmark. Last year, when the chalet was finally sold the proceeds from the sale didn’t go to Glitnir but to Palmadottir. Johannesson has now paid ISK2bn to Glitnir but Glitnir notes that the money is partly coming from Palmadottir, not out of Johannesson’s assets. Another chalet, previously owned by BG Danmark is amongst the assets of the now bankrupt Baugur in Iceland and 101 Chalet’s value is 0 on the list of Johannesson’s assets.

An interesting twist in this tale is that in QC Gillis’ skeleton statement it says: ‘Mr Johannesson sought to argue that the personal guarantee* in his name had been signed by his sister without his authority.’ – I leave it to the readers to interpret what this implies.

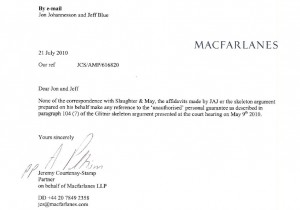

Johannesson’s sister firmly denies having signed the Gaumur guarantee without her brother’s authority. Johannesson hasn’t been interviewed on this issue. He has however issued a statement** saying that he has never accused his sister of having signed anything without his knowledge. Attached to his statement is a letter from his lawyer Jeremy Courtenay-Stamp.

Plenty of conflicting stories here – so there must be more to come…

*The Gaumur guarantee.

** In Icelandic but there are quotes there in English. The letter above is from Johannesson’s statement.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

The collective amnesia – will there be the Johannesson Institute?

Back in the 80s, one of the highlights of the year in the US financial sector was the annual Beverly Hills’ junk bond convention organised by the godlike junk bond king, Michael Milken. But as so masterly recounted in ‘The Den of Thieves’ – and confirmed in a US court, Milken was a common fraudster, convicted and sentenced to ten years in prison after being indicted on 98 counts of racketeering and fraud. This included a whole raft of illegal activities such as insider trading, stock parking, tax evasion and taking cut of illicit profits that others gained based on Milken’s information. This looks like a list of activity some of his Icelandic brothers-in-spirit might eventually be convicted of if the Office of the Special Prosecutor is on the right track.

In an interview recently in Iceland Eva Joly, the investigative Norwegian-French judge who sent around 30 high-placed people to prison in the Elf trial, pointed out that some high-flyers never admit to any wrongdoing even when they are convicted and sent to prison. Milken was one of them. This is the story according to the man himself, as published on his website:

“In 1989, the government charged Milken with securities/reporting violations in a case that continues to engender controversy. He admitted conduct that resulted – during a brief period in his 20 years on Wall Street – in five violations. Although such conduct had never before (nor has since) been prosecuted criminally – a fact rarely mentioned in press reports – he resolved the case without a trial to prevent further impact on his family. After paying a $200 million fine and serving a one-year-and-10-month sentence, he resumed his philanthropic work.”

Milken’s version skips the fact that he has a lifetime ban on working in securities and paid around $1,1bn in fines and various settlements with the SEC and investors who lost money on his schemes – not to forget that he was indeed convicted and received a sentence of ten years, out of which he should serve a minimum of three years. In the end he only served just over two years because he was diagnosed with prostate cancer with only around two years to live.

Yet, he still lives to tell the story and the glamorous Beverly Hills conference, now the Global Conferencen, is again a major get-together, last held in April this year. Milken is still among the wealthiest people on this planet and has been very astute at using his wealth to buy himself respect and a seat at the right tables. His story is an intriguing example in any debate on whether crime pays – his $200m SEC fine bore no relation to the sums he made on the activities he was fined for. This spring, he shared the podium at the Global Conference with no less than the economist superstar Nouriel Roubini – which to my mind rather reduced Roubini to a junk bond status.

Icelanders follow with avid interest how those who bankrupted the Icelandic financial system – bankers and businessmen alike – still live in apparent wealth. Just this week, it turned out that Magnus Kristinsson and his family all drive around in big and expensive cars though the banks have had to make a ISK50bn, £265m, write-off on his debt. At the height of the folly, Kristinson commuted from his home in the Vestman Islands by his own helicopter – his original source of wealth was fishing. Kristinsson is unknown abroad but well known in Iceland, i.a. for owning Gnupur, an investment company that was the first – and only – investment company to fail during the winter of 2007-08. Its collapse immediately sent the banks’ CDS spreads sky-rocketing and a shiver down the spine of bankers and businessmen: if this was the effect of the bankruptcy of a small obscure investment company it was obvious that if a major company like Baugur, FL Group or Exista would fail the effect would be cataclysmic. The banks made sure it didn’t happen.

The question in Iceland is if and when the Viking raiders and their bankers will go to prison. The story of Michael Milken shows that crime can pay. For the time being, names like Johannesson or Bjorgolfsson only attract scorn and anger in Iceland – but if Icelanders will be hit by the same kind of general amnesia that helps Milken buying his place in elevated company there might be Icelandic institutions in the future bearing these and other now so infamous names.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

The squeezed big boys

Goldman Sachs was charged with fraud, or as former Under Secretary of the US Treasury Peter Fisher put it, the bank showed the kind of behaviour Fisher has called ‘naughtiness.’ Now, it can pay its way out of court with a $500m fine to the SEC. The story is that a hedge fund, Paulson, was certain that the mortgage market had peeked and wanted a mortgage product it could bet against. It chose products to put in a bundle, called Abacus – Goldman’s staff chose about half of it. Then it was sold to customers who weren’t told that this product was made for someone to bet against, thus defining customers’ relations the Goldman way. As envisaged, the customers who bought the product lost and Goldman and Paulson won (though Goldman’s CEO Leo Blankfein tried to pretend during hearing at US Congress that Goldman had also lost until he was reminded of the fact that Goldman only lost because it couldn’t sell all these product, not because it believed in the product).

Plenty of people will not have too great a sympathy for the customers who lost. Aren’t they institutions who should know better, who have the means to know what they are buying? In short, aren’t they big boys who should be big enough to know what they were being sold?

In an ideal market they are big enough to know. But the market was far from ideal in 2007 leading up to autumn 2008. Recently, I talked to an analyst who worked for Kaupthing, the failed Icelandic banks. He mentioned the Goldman Sachs case, adding ‘we were the suckers back then,’ meaning that also Kaupthing bought similar products (not the Goldman products at the heart of the fraud case though) that later turned out to generate losses (although none of the Icelandic banks bought much of the subprime toxic products – their largest clients turned out to be much more toxic though but that’s another story).

Kaupthing, like any other bank, had of course analysts who in principle should analyse what the bank was being offered. But these weren’t normal times. In 2007, the analysts got ever shorter time to analyse. Towards the end of the year they weren’t given any time at all to do their work. The bigger boys, the big banks and the market makers shoved a product under their nose with the offer ‘buy it now or leave it,’ giving no time to scrutinise or analyse.

Those who didn’t say ‘yes’ fast enough just lost the opportunity to buy this product and then eventually would lose out on everything. Or that at least was what they feared. The refrain was ‘if you don’t buy it we will sell it to someone else.’ End of story – and banks like Kaupthing feared they would simply be left out of the loop completely. No deals, nothing would be coming their way. And that would of course have been end of story. End of their story.

I have no pity for any of these banks and certainly no sympathy for a bank like Goldman. But behind this story is the story of big boys being squeezed, threatened and bullied by yet bigger boys. Like Goldman Sachs.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

C’est la vie

In Iceland, playful kids throw snowballs at each other in winter. Not so playful businessmen, down on their last million, throw threats of personally suing those who on behalf of the collapsed banks are clawing back the billions of Icelandic Kronur of debt. In an interview, published in the Icelandic Vidskiptabladid today, Jon Asgeir Johannesson claims he will personally sue Steinunn Gudbjartsdottir the chairman of the Glitnir Winding-Up Board for her ‘sworn lies’ submitted in connection with the freezing order, confirmed last Friday.

According to Johannesson Gudbjartsdottir alleges that his assets are more exstensive than the £1.1m. In an email sent to Glitnir CEO Larus Welding and Stodir (earlier FL Group) Jon Sigurdsson just before the collapse of the banks in Oct. 2008 Johannesson lists accounts holding £202m. The email hasn’t been published so it’s unclear why Johannesson was listing these assets to the two CEOs.

During the freezing order hearings Glitnir’s lawyer pointed out that, contrary to what Johannesson now claims, Gudbjartsdottir didn’t know who owned these £202m. She didn’t know May 11 when the freezing order was submitted – and she didn’t know late June when asked again. In the meantime Johannesson had given a statement, saying that the money belonged to the supermarket chain Iceland where he was a director until he resigned in May due to the freezing order.

Now, Iceland’s CEO Malcolm Walker, who Johannesson and his co-investor in Iceland chose as a CEO, has written a letter to Gudbjartsdottir, saying that the millions belonged to Iceland the supermarket chain. If Johannesson thought it important to clarify who owned the £202m it’s rather mystifying why he didn’t ask Walker to document this while the freezing order was still being dealt with by the court. Why did he wait until after the Court had already confirmed the freezing order?

Gudbjartsdottir is hardly quaking in her boots over Johannesson’s threat – and by the way, he hasn’t mentioned if he will sue her in Iceland or abroad. From other resolution committees and winding-up boards I know that the big debtors regularly threat to sue their members personally. For those who deal with the big debtors who are used to being able to rule with money and the threat of making use of their money it’s all part of their job – for them c’est la vie.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

A refreshing clarity

On Friday, Justice David Steel had two things to consider regarding the freezing order on Jon Asgeir Johannesson’s assets: did he believe that Johannesson had more assets than those he had already informed Glitnir of – and is Johannesson’s career and character such that he might possibly try to dispose of assets without informing Glitnir?

By upholding the freezing order Justice Steel answered these two questions quite clearly. No, he didn’t believe Johannesson had given a ‘full and frank disclosure’ of his assets – and yes, he did believe that Johannesson, a man of ‘low standard of commercial morality’ according to Justice Steel, might indeed try to dispose of assets and thus continue trying to avoid paying his humongous debt to Glitnir. This phrase, ‘low standard of commercial morality,’ is a marvellous example of English understatement and is indeed laden with potent meaning.

Since I broke the news in Iceland of the hearing on Friday I’ve heard from many Icelanders – and the message has been: what a relief to hear a judge speak so clearly of Johannesson and his character. Here was a venerable judge who absolutely didn’t mince his words and left no lingering doubt as to what sort of a businessman he thought he was dealing with – a businessman of ‘low standard of commercial morality.’

Those I’ve heard from are also content that the case has been brought out of Iceland, into another context, absolutely beyond any possible interference of interests and personal connection. I firmly belief that in spite of the dismal story of the Baugur case earlier (where most of the charges against Johannesson were thrown out but where Johannesson was indeed handed a sentence of three months in jail, albeit a conditional sentence) the Icelandic courts will be able to deal with eventual charges against bankers and their fellow business travellers in a fair and frank way – but the clarity of Justice Steel was refreshing and uplifting and will hopefully constitute an example for his Icelandic opposite numbers.

But it’s not just in Iceland that there is a lack of clarity when it comes to alleged fraud. In his statement before the US Senate’s Subcommittee on Crime in May the economist James Galbraith pointed out that on the day that the SEC charged Goldman Sachs with fraud a former Under Secretary of the US Treasury Peter Fisher couldn’t bring himself to mention the word ‘fraud.’ Instead, he used the word ‘naughtiness’ – as if a banker had been caught in spending the night with his secretary on the bank’s expenses account.

Clarity is also sorely needed when it comes to the flight of certain businessmen into secrecy jurisdictions – the web of offshore havens that the big banks have been pretty good at offering to their clients when they want to be really naughty. It’s to the great shame of both the UK and the US that the major part of these secrecy jurisdictions thrive in places connected to these two countries. But also here there is an ongoing detectable change: HSBC is under criminal investigations in the US for selling offshore tax services to their clients – and Deutsche Bank is under similar investigation in Germany, alleged to have assisted clients to avoid tax by trading emission allowances. The intriguing bit of the DB story is that DB bankers were warned beforehand of extensive raids but the investigators were a step ahead and were listening in on their phone calls.

The refreshing clarity that Justice Steel showed isn’t only desperately needed in Iceland but when dealing with white-collar fraud in general. In Johannesson’s case Justice Steel saw more than just some naughtiness – he spotted the low standard of commercial morality, not only an Icelandic trait.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

The Magma mega mess

There is the Eton mess, a delicious summer dessert of whipped cream, icecream, strawberries and meringue. The Magma mega mess is less delicious but it’s also a summer thing and is now all-consuming news in Iceland. There is suddenly a frantic political activity to stop the Magma deal but it’s not clear what will happen.

It was during summer last year that Magma Energy surfaced in Iceland as the potential buyer of one of the Icelandic energy companies, HS Orka, to begin with the share of OR, Reykjavik Energy, owned by the city of Reykjavik. This wasn’t the first move towards mixing private enterprise and public ownership. A year before the Icelandic banks imploded in October 2008 it emerged that some of the most risk-prone businessmen, notably Hannes Smarason of FL Group-fame, together with Bjarni Armannsson ex-CEO of Glitnir, a banker no less taken up by his own interest than the bank’s, had been planning a particularly cunning deal to buy OR. Part of the cunning was that the deal would immediately release zillions of Kronur for Armannsson, Smarason and their partners. Since the city of Reykjavik was incidentally aiding the instantaneous enrichment of the few chosen the news of this deal so enraged Icelanders that the deal collapsed.

Ever since, it’s been clear that Armannsson, together with other ex-Glitnir managers, has been looking for opportunities in the Icelandic energy sector. After all, energy and food was Glitnir’s speciality. Armannsson is now involved in one of the date centre projects in Iceland.

Favoured deals, like the OR deal, has been the chosen way of doing business in Iceland – a way that many Icelanders now hope will come to an end. After all, it’s clear that this was a major factor in the fall of the banks. Therefore, many in Iceland have a lingering feeling that ex-Glitnir bankers or other Icelanders are somewhere involved in the Magma affairs in Iceland.

There are some disturbing inconsistencies. Last year, Magma-CEO Ross Beaty, also Magma’s largest shareholder, sought to convince Icelanders that he wasn’t at all interested in buying the whole of HS Orka. Well, now nothing less will do.

Already last September I pointed out two major flaws in the Magma deal: firstly, when a public good is sold it has to be done in a transparent way – not the case here, there’s total opacity. Instead of a transparent deal where Magma pays outright and OR sells outright its coveted share in HS Orka the deal is convoluted with loans from the sellers. This is completely opposite to golden rules on privatisation laid out by the World Bank, OECD and others: if a public good is sold the sale should be transparent and bring plane cash to the coffers right away. All risk should be on the buyer, not the seller as is the case in the Magma deal.

Secondly, is so happens that Icelandic law prohibits non-EU/EEA companies to buy into the Icelandic energy sector. Magma found a way around this lay by setting up a subsidiary in Sweden as a holding company for its Icelandic assets. The Swedish company has, as far as is known, no purpose other than owning the Icelandic assets. It’s clear that if all it takes to own energy assets in Iceland is an off-the-shelf company in some EU/EEA country then the law is void and meaningless. – It’s difficult to belief that the Efta-court will let this pass since this would constitute an example in the other EEA countries.

It’s also interesting to note that Magma didn’t set up an Icelandic holding company. Most likely, a Swedish company brings some tax benefits. The ownership of Magma itself is an interesting case: a charitable foundation, Sitka Foundation, owned by Beaty, is the major shareholder. This has all the characteristics of a tax speculation and hidden ownership.

Consequently, Magma has been able to buy up ever-greater parts of HS Orka and now owns 43% and is buying Geysir Green Energy’s 55% in HS Orka. As if all this weren’t enough the truly scary part is that whereas it was at first trumpeted that Magma would bring much needed investment to Iceland it’s now liaised with a fund owned by the Icelandic Pension Funds that will invest in HS Orka. It also seems that Magma was allowed to buy offshore Kronur, no doubt at a favourable rate, instead of bringing foreign currency to Iceland. This weekend, it transpired that Magma’s CEO is himself lending money to Magma – a rather surreal course of events in a company that was supposed to be a strong investor bringing foreign investment to Iceland.

An ever-present element in discussion on foreign investment in Iceland is the atavistic Icelandic xenophobia, the fear of foreign barbarians at Icelandic shores. However, in the case of Magma there is a firm and solid ground to doubt the soundness of this investment. Foreign investment is of course painfully necessary in Iceland. It beggars belief why politicians are so prone to make elementary mistakes when it comes to foreign investment and the sale of public good. The fearful danger is that this proneness will create one mess after the other, certainly no Eton mess – and that this proneness will perpetuate itself by attracting the wrong kind of foreign investors to Iceland.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Johannesson’s assets

This is the list of Jon Asgeir Johannesson’s assets as presented to the UK court on Friday:

British assets:

Bank accounts:

Coutt’s £30,675.89 (ISK5,8m) 5.7. 2010

Coutt’s £71.53 (ISK13.400) 5.7. 2010

Cars:

Range Rover, valued £15,000 (ISK2,8m)

Rolls Royce Phantom, valued £90.000 (ISK17m) Regisistered on Johannesson who now claims it’s a birthday present to his wife

Aston Martin, valued £40.000 (ISK7,5m) In the process of being sold

Shares:

Shares in JMS Partners, valued £32.000 (ISK6m) according to an offer from the two other shareholders (Gunnar Sigurdsson Baugur’s ex-CEO and Don McCarthy chairman of board House of Fraser) will be sold; until then Johannesson is paid as a boardmember

Icelandic assets

Property:

Laufasvegur 69, valued £600.000 (ISK113,5m)

Hverfisgata 10, valued £3.125.000 (ISK591m)*

Farmland in Skagafjordur, valued £73.000 (ISK13,8m)

Vatnsstigur, valued £182.395 (ISK34,4m)

Mjoanes, Thingvellir, valued £40.000 (ISK7,5m)

Langjokull Chalet, valued £11.000 (ISK2m)

Shares:

Thu Blasol, valued 0

Gaumur efh, valued 0

101 Chalet efh, valued 0

Bank accounts:

Glitnir, ISK2,2m

Byr, ISK0,5m

Arion, ISK0,1m

Cars:

Range Rover 1, valued £20.000 (ISK3,7m)

Range Rover 2, valued £20.000 (ISK3,7m)

Bentley, valued £70.000 (ISK13,2m)

*Johannesson now claims this property belongs to his wife

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

A peephole on the life of a Viking raider

The beauty of the American court system is the transparency into the cases as they evolve – and right now, it’s the Glitnir Winding-Up Board against the Johannesson Defendants, i.e. Jon Asgeir Johannesson and his wife Ingibjorg Palmadottir. An active business woman in her own right she’s aired her irritation at being seen as her husband’s ‘alter-ego.’ No doubt, this is because her husband is seen as the main culprit but due to the fact that their business interests have become intertwined this is the way American lawyers have chosen to frame the case. After all, it’s difficult to suspect the GWB of sexism: it’s headed by a sure-footed female lawyer, Steinunn Gudbjartsdottir.

Johannesson, his wife and five others are being brought to court in New York as the GWB seeks to get back $2bn claimed to have been looted from the bank by this gang of seven with a strong support of Glitnir’s auditor PriceWaterhouseCooper, Iceland. For the time being, the case centres on Johannesson-Palmadottir and their ownership of three flats in the super-exclusive NY condo 50 Gramercy Park, also mentioned in the international freezing order, confirmed by a UK court on Friday.

The flats have been the centre of some attention lately. In 2006-07 – the time when the folly of the favoured clients of the Icelandic banks reached its climax, the years of buying yachts, jets and other trophy assets – the couple bought not one but three flats at this Ian Schrager-designed condo, 16A, 17A, 18A, for $25m. Two flats were merged, which is why just two flats are often being mentioned. Landsbanki lent the money but either didn’t bother their clients with collaterals or forgot – I’ve repeatedly asked the Landsbanki resolution committee about this case but they decline to comment until this case is over. However, on in the UK court papers it seems that Johannesson has given conflicting information on the financing, claiming at different times that his family financed it or that the financing came from Landsbanki.

Be that as it may, from the NY court document it’s now clear that the couple possesses these three units, now two flats: one flat is now a collateral held by Landsbanki, the other by Glitnir. Palmadottir’s address in the court documents is given as 50 Gramercy Park though in a recent statement she claims to be domiciled in the UK. Johannesson’s address is the same though he also gives a Knightsbridge address and the address of JMS Partners, one of his businesses in the UK, in London’s West End. From the documents it’s also clear that the couple rents one of the NY flats out, collecting a rent of $312.000. According to Palmadottir’s statement her son (from a previous marriage) now lives in the other one. She also confirms earlier news that other inhabitants at Gramercy Park have sued the couple because they hadn’t kept to the high standard of interior decoration expected in this distinguished property (the couple fitted their flat with an IKEA kitchen).

In an article recently, Johannesson refused that he had any assets in offshore islands. According to the NY documents he has millions with the Royal Bank of Canada – interestingly, the bank offers extensive offshore services and is under investigation in Canada for allegedly helping some clients to evade tax. Out of these millions the couple are said to have paid up a loan to the RBC recently of $10m. The GWB claims that these 10m are part of the Glitnir loot. Palmadottir claims that she bought the flats with her own family money, she comes from a wealthy family, and that the flats belong to her except for a 1% belonging to her husband. At the UK court on Friday, Johannesson’s lawyer maintained that Johannesson’s total assets now only amount to £1,1m.

The report of the Althingi Investigative Commission tells a rather different story. Palmadottir, as business partners like Palmi Haraldsson, Magnus Armann, Sigurdur Bollason, Thorsteinn Jonsson, Hannes Smarason and several others were a tightly knit group where assets moved around in an incestuously intimate way – made all the easier because the banks quite often didn’t see these parties as at all related though every Icelander on the street would know that the ties were indeed close. – The NY court documents mention these close ties.

The couple is mainly contesting the jurisdiction of the NY court, claiming that any case against them should be brought in Iceland, the information from subpoena regarding 50 Gramercy Park and from Royal Bank of Canada be revealed and that Glitnir can use any information from the NY court case in either Icelandic or British court.

The GWB claims that the Johannesson transactions made no economic sense for Glitnir. The same counts for so much of the money the favoured few obtained from the Icelandic banks – and so much of these loans wasn’t used to build up any business but was just spent on private assets such as houses, cars, yachts and jets.

Most likely, Kaupthing will be issuing charges later this year, possibly late summer or autumn. The resolution committee has already gathered a lot of material passed on to the Office of the Special Prosecutor. Johannesson was also a big borrower in Landsbanki. Hopefully, the Landsbanki resolution committee will at some point throw light on Johannesson’s relations with Landsbanki – and within Landsbanki there are undoubtedly many interesting stories, indeed whole sagas, waiting to be told of the bank’s relations with its major shareholders father and son Bjorgolfur Gudmundsson and Thor Bjorgolfsson who in addition also had yet another bank Straumur, with yet more stories in addition to the apparent interconnections of the banks and their major shareholders.

There are plenty of new Icelandic sagas in the making…

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

The complicated life of David Rowland

David Rowland, who will be the Conservative Party’s treasurer come October, has had a colourful live with some dirty spots here and there – or that’s at least what the Daily Mail has dug up. Rowland bought Kaupthing Luxembourg, turned it into Banque Havilland with his son Jonathan now as its CEO after Magnus Gudmundsson who used to run Kaupthing Luxembourg and was retained by the Rowlands was remanded in custody because of an ongoing Icelandic investigation of Kaupthing. Havilland is the administrator of the failed bank, through Pillar Securitisation.

It was through Kaupthing Luxembourg that Kaupthing, under Gudmundson, ran its most shady deals – and from there the web trails to offshore havens such as Panama, Cyprus and most notably the BVI. Recently, authorities in Luxembourg searched the premisses of Havilland on behalf of the Office of the Special Prosecutor in Iceland, to aid investigations unrelated to the present Banque Havilland.

It’s interesting to note, however, that there are still some Icelandic clients at Havilland. Gaumur, a company owned by Jon Asgeir Johannesson and his family, has a Luxembourg subsidiary registered with Havilland with three BVI companies, previously owned by Kaupthing, registered as Gaumur S.A.’s directors so no changes there in that respect.

Daily Mail notes that Rowland once said that money makes your life complicated and the more money the more complicated life becomes. Now that Rowland will be taking up a position with the Tories he’s bound to be heavily scrutinised by the press and that might in turn make his life more complicated.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

A tale of a ‘low standard of commercial morality’

‘There is something unreal about this,’ the sharp and witty Justice David Steel said late in the day Friday afternoon, after listening to Glitnir lawyers debating from the morning with lawyers representing Jon Asgeir Johannesson. In the dignified surroundings of Old Bailey his team was trying to quash the international freezing order that the Glitnir Winding-Up Board obtained at the Royal Court of Justice in May. More than once, Justice Steel reminded himself and the others present – mostly lawyers, apart from the black-clad couple Johannesson and Ingibjorg Palmadottir and a couple of their friends – that Johannesson had been the prince of the UK high street challenging the king of retail, Sir Philip Green.

To begin with, Johannesson’s lawyer asked for the hearing to be held in private – the delicate information unavoidably disclosed would be all over the Icelandic papers tomorrow (as a matter of fact the news was out during the lunch break) – but Justice Steel upheld the core British principle of an open court. So I wasn’t thrown out but could sit and listen – and there was a lot to hear.

Johannesson claims that his assets now total only £1,1m: his assets in the UK total £199.000, including three cars – a Rolls Royce Phantom, a Range Rover and an Aston Martin. However, after presenting the list of assets earlier Johannesson has now changed his mind on the Rolls Royce claiming it’s a gift to his wife though he hasn’t produced any documents to support his claim. In London Johannesson lives in a rented property, paying £6.000 a month. From JMS Partners, the company that Johannesson co-owns with House of Fraser chairman Don McCarthy and ex-CEO of Baugur Gunnar Sigurdsson Johannesson draws a £700.000 annual salary – though its operation is rather unclear.

In Iceland, his assets are again three cars, two Range Rovers and a Bentley and then four houses one of which is heavily mortgaged, £15.000 in four bank accounts and shares of no value in several companies, most noteworthy in Gaumur where Johannesson owns 45%. Gaumur’s debt is ISK8bn and seems, according to Justice Steel, in reality insolvent. Earlier, Johannesson had claimed that he co-owned Hotel 101 with his wife but now claims that his wife owns is. He also claims that two properties are hers although the mortgages are in his name. He has £22.000 in a Coutt’s account and some $70.000 in an account with Citigroup.

Justice Steel was intrigued by the fact that a man who was once said to be worth £600m, who had in the years 2001-2008 a monthly expenditure £280.000-350.000 (!) and also had £11m flowing through his Glitnir account in autumn 2008, as the banks were collapsing, now only has a paltry £1,1m worth of asset to show for it out of which 275.000 are in cars. An expenditure on this level couldn’t but leave something more substantial behind thought the judge.

Around the time that Glitnir obtained the freezing order Johannesson had ca £500.000 flowing in and out of his account at Coutt’s (a UK bank for very wealthy individuals) – Johannesson’s lawyer explained, apparently to Justice Steel surprise, that the money stemmed from the sale of his ex-wife’s house, bought by him, and then used immediately to pay off bills that Johannesson hadn’t been able to pay earlier.

Today it transpired that Johannesson and his wife used to own two (not just one as earlier believed) yachts, one of which had been repossessed and sold on by Kaupthing Luxembourg (in reality, Banque Havilland). The interesting point here is that according to Justice Steel no documents have been produced to prove the sale – and the Kaupthing Luxembourg administrators have not been willing to co-operate with Glitnir on this matter. The question left hanging in the air was if the proceeds of the sale really did go to Kaupthing. The other yacht, a Ferretti, was pledged to and apparently repossessed by Sparbank – a surprising lender if it’s the Danish Sparbank since it’s a small bank.

An additional reason to distrust Johannesson’s list of assets produced was, according to Justice Steel, the fact that Johannesson had been less than forthcoming with information and had then changed his mind on some things without any documents to support what Johannesson then called ‘mistakes.’ Also that he hadn’t been able or willing to produce any overview of his salary at Baugur – only, that a flow of £3-4m had gone through his pockets every year. In all, £30m had been paid to his Glitnir accounts during these years. SWIFT transfers show accounts with Kaupthing Luxembourg, KSF and Royal Bank of Scotland.

Justice Steel had also doubts about the source of Johanneson’s funding, i.a. the loan on the flats in New York where Landsbanki had lent of $25m without any security. It was obvious that his Lordship struggled to understand the logic in this for the bank. And he also struggled to understand the change of ownership in the media company 365 midlar that Johannesson now claims belongs to his wife. Nor could his Lordship understand that someone who didn’t seem to have any assets was engaging lawyers both in the UK and the US. Probing his lawyer on that the lawyer also had difficulties in explaining the importance of a freezing order when there were practically no assets to freeze.

Listening to these and other issues, Justice Steel said he wasn’t assured that Johannesson had given a full and frank disclosure of his assets. In addition, there was the complicated corporate structure that would give ample room to move assets around. The fact that Johannesson had sold the Chalet 101 to his wife while negotiating with Glitnir on how to repay the loan didn’t inspire confidence either. The judge also mentioned what the Glitnir lawyer had said: that Johannesson’s conduct indicated a ‘low standard of commercial morality’ – on the whole there was, according to Justice Steel, a real risk that assets would be disposed of, leading him to renew the freezing order.

In the end, Johannesson’s lawyers had to disclose their bill of whopping £600.000 – Johannesson has to pay all cost, possibly running up to £360.000 but the immediate payment is £150.000. If he doesn’t pay he risks being declared bankrupt.

The freezing order is related to the Glitnir case in the UK against Palmi Haraldsson and Johannesson regarding ISK6bn loan to Haraldsson’s Fons. The basis of that case is that assets were sold at a premium only to extract money from Glitnir for the benefit of the two businessmen and make the bank lose. – No doubt, there is more of amorality and the unreal to come.

*There were no documents handed out in court – I hope the information above is correct but mis-hearing or misunderstanding can’t be ruled out.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.