Archive for February, 2012

The hard core Kaupthinking – and Ice-banking

Here is a video, with a voice-over in English based on Icelandic tv reporting on Kaupthing, explaining the bank’s prop trading, how it kept the share price high and allegedly manipulated the market. “Kaupthinking, thinking beyond” was the slogan the bank used in its advertising.

To my mind, the prime example of Kauthinking is found in an email sent by Kaupthing Luxembourg manager Magnus Gudmundsson, now indicted by the Office of the Special Prosecutor, and Armann Thorvaldsson CEO of Kaupthing Singer & Friedlander. In the mail they called themselves “association of loyal CEOs.” Describing the set-up of a certain bonus scheme, they write: “The bank wouldn’t make any margin calls on us and would shoulder any theoretical losses, in case they occurred.” (In Icelandic: ,,Bankinn hefði engin margincall á okkur og myndi taka á sig fræðilegt tap ef að yrði.”

This is the Kaupthinking behind all loans to favoured clients, be they Icelandic or foreign. The question is: What sort of banking was this? In the interest of Kaupthing’s 33.000 shareholders? – To be fair, this kind of lending wasn’t unique to Kaupthing. It was common to the Icelandic financial system before the collapse of the banks (and hopefully no longer). Creating a slogan, this was Ice-banking.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

The al Thani story behind the Kaupthing indictment (updated)

The Office of the Special Prosecutor is indicting Kaupthing’s CEO Hreidar Mar Sigurdsson and Kaupthing’s chairman Sigurdur Einarsson for a breach of fiduciary duty and market manipulation in giving loans to companies related to the so-called ‘al Thani’ case; indicting Kaupthing Luxembourg manager Magnus Gudmundsson for his participation in these loans and Kaupthing’s second largest shareholder Olafur Olafsson for his participation. In addition, Olafsson faces charges of money laundering because he accepted loans to his companies without adequate guarantees.

In September 2008 Kaupthing made much fanfare of the fact that Sheikh Mohammed bin Khalifa al Thani, a Qatari investor related to the Qatar ruler al Thani, bought 5.1% of Kaupthing’s shares. The 5.1% stake in the bank made al Thani Kaupthing’s third largest shareholder, after Olafsson who owned 9.88%. This number, 5.1%, was crucial, meaning that the investment had to be flagged – and would certainly be noticed. Einarsson, Sigurdsson and Olafsson all appeared in the Icelandic media, underlining that the Qatari investment showed the bank’s strong position and promising outlook.

What these three didn’t tell was that Kaupthing lent the al Thani the money to buy the stake in Kaupthing – a well known pattern, not only in Kaupthing but in the other Icelandic banks as well. A few months later, stories appeared in the Icelandic media indicating that al Thani wasn’t risking his own money. More was told in SIC report – and now the OSP writ tells quite a story. A story the four indicted and their defenders will certainly try to quash.

The story told in the OSP writ is that on Sept. 19 Sigurdsson organised that a loan of $50m was paid into a Kaupthing account belonging to Brooks Trading, a BVI company owned by another BVI company, Mink Trading where al Thani was the beneficial owner. Sigurdsson bypassed the bank’s credit committee and was, according to the bank’s own rules, not allowed to authorise on his own a loan of this size. The loan to Brooks was without guarantees and collaterals. This loan, first due on Sept. 29 but referred to Oct. 14 and then to Nov. 11 2008, has never been repaid. – Gudmundsson’s role was to negotiate and organise the payment to Brooks. According to the charges he should have been aware that Sigurdsson was going beyond his authority by instigating the loan.

But this was only the beginning. The next step, on Sept. 29, was to organise two loans, each to the amount of ISK12.8bn, in total ISK25.6bn (now €157m) to two BVI companies, both with accounts in Kaupthing: Serval Trading, belonging to al Thani and Gerland Assets, belonging to Olafsson. These two loans were then channelled into the account of a Cyprus company, Choice Stay. Its beneficial owners are Olafsson, al Thani and another al Thani, Sheikh Sultan al Thani, said to be an investment advisor to al Thani the Kaupthing investor. From Choice Stay the money went into another Kaupthing account, held by Q Iceland Finance, owned by Q Iceland Holding where al Thani was the beneficial owner. It was Q Iceland Finance that then bought the Kaupthing shares. As with the Brooks loan, none have been repaid.

These loans were without appropriate guarantees and collaterals – except for Serval, which had al Thani’s personal guarantee. After noon Wed. Oct. 8, when Kaupthing had collapsed, the US dollar loan to Brooks was sent express to Iceland where it was converted into kronur at the rate of ISK256 to the dollar (twice the going rate in Iceland that day) and used to repay Serval’s loan to Kaupthing – in order to free the Sheik from his personal guarantee.

This is the scheme, as I understand it from the OSP writ. And all this was happening as banks were practically not lending. There was a severe draught in the international financial system.

The Brooks loan is interesting. It can be seen as an “insurance” for al Thani that no matter what, he would never lose a penny. When things did go sour – the bank collapsed and all the rest of it – this money was used to unburden him of his personal guarantee. Otherwise, it would have been money in his pocket. It’s also interesting that the loan was paid out to Brooks on Sept. 19, his investment was announced on Sept. 22 – but the trade wasn’t settled until Sept. 29. This means that his “guarantee” was secured before he took the first steps to become a Kaupthing investor.

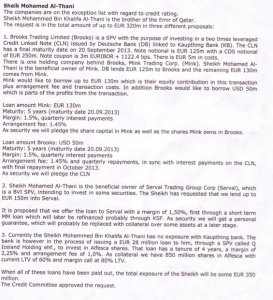

Apparently, Kaupting’s credit committee was in total oblivion of all this. The CC was presented with another version of reality. Below is an excerpt from the minutes regarding the al Thani loan, discussed when the Board of Kaupthing Credit Committee met in London Sept. 24. 2008 (click on the image to enlarge).

Three things to note here: that the $50m loan “is parts of the profits from the transaction.” Second, that al Thani borrowed €28m to invest in Alfesca. It so happens that Alfesca belonged to Olafsson. Al Thani’s acquisition in Alfesca was indeed announced in early summer of 2008 and should, according to rules, have been settled within three months. At the end of Oct. 2008 it was announced that due to the market upheaval in Iceland al Thani was withdrawing his Alfesca investment. Thirdly, it’s interesting to note that Deutsche bank did lend into this scheme – as it also did into another remarkable Kaupthing scheme where the bank lent money to Olafsson and others for CDS trades, to lower the bank’s spread; yet another untold story.

According to the OSP writ, the covenants of the al Thani loans differed from what the CC was told. It’s also interesting to note that the $50m loan to al Thani’s company was paid out on Sept. 19, five days before the CC meeting. This fact doesn’t seem to have been made clear to the CC.

The OSP writ also makes it clear that any eventual profits from the investment would have gone to Choice Stay, owned by Olafsson and the two al Thanis.

Why did al Thani pop up in September 2008? It seems that he was a friend of Olafsson who has is said to have extensive connection in al Thani’s part of world. Olafsson’s Middle East connection are said to go back to the ‘90s when he had to look abroad to finance some of his Icelandic ventures. London is the place to cultivate Middle East connections and that’s also where Olafsson has been living until recently. It is interesting to note that the Financial Times reports on the indictments without mentioning the name of Sheikh al Thani.

The four indicted Icelanders are all living abroad. Sigurdur Einarsson lives in London and it’s not known what he has been doing since Kaupthing collapsed. Hreidar Mar Sigurdsson lives in Luxembourg where he, together with other former Kaupthing managers, runs a company called Consolium. His wife runs a catering company and a hotel in Iceland.

Magnus Gudmundsson also lives in Luxembourg. David Rowland kept him as a manager after buying Kaupthing Luxembourg, now Banque Havilland, but Rowland fired Gudmundsson after Gudmundsson was imprisoned in Iceland for a few days, related to the OSP investigation. In the Icelandic Public Records it’s said that Olafsson lives in the UK but he has now been living in Lausanne for about two years. In Iceland, he has a low profile but is most noted in horse breeding circles, a popular hobby in Iceland. He breeds horses at his Snaefellsnes farm and owns a number of prize-winning horses.

Following the indictment, Olafsson and Sigurdsson have stated that they haven’t done anything wrong and that the al Thani Kaupthing investment was a genuine deal. The case could come up in the District Course in the coming months. But perhaps this isn’t all: it’s likely that there will be further indictment against these four on other questionable issues related to Kaupthing.

*The OSP indictment, in Icelandic.

**Does it matter that the four indicted are all living abroad? When I made an inquiry at the Ministry of Justice in Iceland some time ago whether Icelanders, living abroad but indicted in Iceland, could seek shelter in any country in Europe by refusing to return to Iceland I was told they couldn’t. If an Icelandic citizen is indicted in Iceland and refuses to return, extradition rules will apply. In this case, Iceland would be seeking to have its own citizens extradited and such a request would be met. – It has been noted in Iceland how many of those seen to be involved in the collapse of the banks now live abroad. It can hardly be because they intend to avoid being brought to court – they would have to go farther. Ia it’s more likely they want to avoid unwanted attention. For those with offshore funds it might be easier to access them outside of Iceland rather than in a country fenced off by capital controls.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

OSP brings charges in the al-Thani case (updated)

The Office of the Special Prosecutor in Iceland has now brought charges in the so-called al-Thani case. In September 2008 Kaupthing announced that a Qatar investor, Mohamed bin Khalifa al-Thani, had bought just over 5% of share in Kaupthing. It later turned out that al-Thani wasn’t risking his own money but Kaupthing’s fund: the bank lent him money to buy the shares. A familiar pattern but this was an important statement because it made the bank seem like a good investment. The interesting thing is that according to documents from Kaupthing Deutsche Bank was involved in the al-Thani investment scheme.

Those charged now are the bank’s CEO Hreidar Mar Sigurdsson, Chairman Sigurdur Einarsson, Kaupthing Luxembourg manager Magnus Gudmundsson and the second largest shareholder in Kaupthing Olafur Olafsson. They are all charged with market manipulation. Sigurdsson and Einarsson are seen as the organisers and are in addition charged with breach of fiduciary duty. Olafsson and Gudmundsson are charged for participation in this breach and Olafsson is in addition charged for money laundering.

The charges are not public yet. Those four now charged are all living abroad. Olafsson has sent out a statement denying the charges. Sigurdsson says he is disappointed and holds on to the official story from September 2008: the sale was genuine and the sheikh did indeed risk his money.

*A blog on the al-Thani case will be coming here soon. Here are earlier blogs referring to the al-Thani case. – The OSP writ can be read here, only in Icelandic.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

A tale of two countries

Tonight, the main news on the Bloomberg‘s webpage is on the new Greek deal. Beneath it there is a Bloomsberg article from earlier today that has shot to the top in the course of the day. If the Greeks read the article on Iceland there would be a massive uprising in Greece because of the new deal: the Icelandic lesson, according to Bloomberg, is that public anger does pay.

Given the circumstances, it’s difficult to imagine what could possibly improve the life of the Greeks – their situation differs from Iceland. But the new EU deal on Greek won’t do wonders for Greece. It will help private sector creditors of Greece, though there is an attempt to force them to write down their debt. Ordinary Greeks will all the same be paying with blood, sweat and tears for years to come in a country where harsh economic measures stifle growth, leaving the Greeks with absolutely no means to grow out of this misery. It remains to be seen how history will judge those Greek politicians who are signing the deal tonight.

The Bloomberg headline on Iceland is “Icelandic Anger Brings Record Debt Relief in Best Crisis Recovery Story.” There are two things of interest here – debt relief and crisis recovery.

As professor Thorolfur Matthiasson explains to Bloomberg, the measures the Icelandic Government has used to help indebted households have worked. “Without the relief, homeowners would have buckled under the weight of their loans after the ratio of debt to incomes surged to 240 percent in 2008, Matthiasson said.” The Government and the banks agreed to forgive debt exceeding 110% of home values. A recent ruling regarding a forex loan indicates a further bonus to those who took out forex loans but the end of that saga, and if it will lead to further debt relief for those who took out indexed loans, is still unclear. The 110% way is, according to professor Matthiasson, “the broadest agreement that’s been undertaken.”

Greeks aren’t fighting forex loans and high private debt but horrific public debt and consequent cuts to the bone. The Icelandic Government did have to make deep cuts but nothing compared to what Greece is facing. Those who want to study the Icelandic recovery find a wealth of information on the IMF website, from a conference held in Iceland last October, as reported earlier on Icelog.

Bloomberg points out that Iceland’s $13 billion economy shrank 6.7% in 2009, but grew 2.9% last year. According to an OECD forecast it will expand 2.4 percent this year and next. In comparison the euro area will grow 0.2% this year. In contrast, Greek GDP has been decreasing for 6-7% a year for the last two years. The forecast for this year, according to the statistics in the new deal, is a decrease of 4.3% – most likely too optimistic – followed by a 0% growth in 2013 and – probably overly optimistic – a growth of 2.3% in 2014.

A significant difference between Icelandic and Greek fortune is that Greece is being forced to fork out money it doesn’t have – but has to borrow – to pay its creditors. Banks with cheap money that didn’t bother to do the math and figure out that Greece should never have been lent all the money it got. For every unwise borrower there is a really dumb lender.

During 2008 the Icelandic Government tried to borrow money abroad to bail out its banks but couldn’t secure the necessary loans. Luckily for Iceland, events in early October 2008 overwhelmed the Government and the IMF – no one could figure out a way to bail out the banks (one Icelog source pointed out that a ECB repo could have been set up but there wasn’t the time). According to my sources, IMF employees present in Iceland as it all happened were furious that the Icelandic Government let the bank collapse but it was all too late and no way to figure out a way when it was all happening.

Instead of the immediate impossibility of saving the banks they were split up: domestic accounts were put into operating domestic banks – and further secured by making domestic deposits a priority claim – whereas the foreign operations were left to go bankrupt, leaving international creditors with whatever can be sold and turned into cash. In addition, the Icelandic Central Banks imposed capital controls to stop a capital flight from the country. This is, in short, the Icelandic way to prevent a banking disaster from turning into a national catastrophe.

This isn’t necessarily a panacea for all sovereigns who hit the rocks – but it’s well worth considering whether saving all banks and let private debt migrate to the public sector, as if it were a natural law to privatise gains and nationalise losses, really is the only way. Iceland couldn’t find any other way at the time (but did indeed later throw good public money at bad private banks; another story mentioned here).

Sadly for the Greeks, it doesn’t seem that any amount of public anger of the Greek demos can diminish this dreadful pain and sad future. Iceland got a quick stab. Today, Greece has been condemned to a lingering pain.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Baldur, the blame game – and the “Flat-Screen Theory of Blame”

The first Surpreme Court ruling in a case of insider trading in Iceland has constituted a clear example: the gain was ISK192m, €1.2m, the sentence is two years imprisonment. There are two fundamentally significant aspects of this case: it’s the first Supreme Court ruling in a case brought by the Office of the Special Prosecutor – and the man found guilty, Baldur Gudlaugsson (b. 1946), is not one of the thirty or so major players in the collapse of the Icelandic banks but a former permanent secretary (a civil servant) at the Ministry of Finance.

Gudlaugsson is a lawyer, intimately connected to the Independence Party, a personal friend of its former leader David Oddsson and as a board member of many companies a prominent person in the Icelandic business community. Interestingly, there was one Supreme Court judge who thought that Gudlaugsson’s guilt was not clear – his name is Olafur Borkur Thorvaldsson, a relative of David Oddsson and his appointment to the Court in 2003 was hotly disputed.

The law Gudlaugsson is seen to have violated is from 2007. The criminal deeds are clearly defined, Gudlaugsson’s sale of shares in Landsbanki in September 2008, shortly before the bank collapsed was, according to the law, illegal. This law has now stood its test.

The ruling will no doubt be a food for thought at the OSP. The state prosecutor lost his last case in the District Court (a case related to Byr and MP Bank). Remains to be seen what the Supreme Court does in the Byr case. The OSP is probably still testing the legal ground before bringing forth further charges.

At the moment, the question of blame is widely debated in Iceland – and the ruling in Gudlaugsson’s case leads to the sarcastic remark, often heard since the District Court ruling, that one civil servant, who made a profit of ISK192m, may be the only person to be sent to prison for criminal acts connected to the collapse of the banks. A scapegoat for the infamous thirty who many Icelanders do blame for these events. – It’s an untimely remark: it’s still far too early to tell what the outcome of the present and coming OPS cases will be.

Apart from Gudlaugsson’s case, the debate on blame falls into two categories: there is what could be called the “Flat-Screen Theory of Blame” – and then the theory, according to which the OSP is working, that alleged crimes are committed by certain individuals. Suspicion of criminal doings should lead to an investigation and, depending on the outcome of the investigation, charges should be brought.

The “Flat-Screen Theory” draws its name from an interview with Bjorgolfur Gudmundsson, who together with his son Bjorgolfur Thor, owned 42% of Landsbanki at the time of its collapse.* In the interview, published a few months after the events of October 2008, Gudmundsson pointed out that Icelanders had lived beyond their means, the number of flat-screens sold in Iceland being a case in point. The core of this theory is that everyone is to blame. Jon Asgeir Johannesson recently aired the same idea – no single person did anything wrong or is to blame; in his version, the collapse seemed like a natural disaster. What happened in Iceland, according to the “Flat-Screen Theory,” was a sort of collective madness that ended in a collective collapse.

This theory has a tail to it, now wagged more and more by various prominent lawyers, who happen to be somehow connected to those seen by many to be to blame. The tail is that the OSP investigations and journalism that seeks to unearth what really happened is “witch-hunt” and “rabble’s court.” This also suggests, implicitly and explicitly, that the attempts to unearth criminal deeds and figure out what really happened is now seen by these lawyers as a much greater threat to the wellbeing and the economy of Iceland than the collapse itself.

In general, the OSP seems to enjoy a high level of trust in Iceland though many find it frustrating how long a time the investigations take. It is however pretty clear who adhere to the “flat-screen theory of blame:” it’s mostly those who were part of, or are now connected to, the political and business elites before the collapse.

Eva Joly (who at the time was much maligned by some of those now propagating the “flat-screen theory of blame”) warned that when those in power feel threatened they use infamy and dirty tricks to further their causes. Gunnar Andersen, the director of the Icelandic Financial Services Authority, the FME, is fighting against being driven out of office. The result of his wrestle with the board, which has just produced a third report into his past at Landsbanki, is still unclear. The FME has, incidentally, sent almost 80 cases to the OSP.

The “Flat-Screen” theorists tend to portray a strikingly selective view of events prior to the collapse. A view that bears little similarity to the findings of the April 2010 report of the Althing Special Investigative Committee. Indeed, in addition to belittling or directly undermining the endeavours of the OSP they also throw doubt on the SIC report or just pretend it doesn’t exist by never referring to it.

It’s fair to say that there is a battle raging in Iceland between the “Flat-Screen” theorists and those who think investigations are necessary in order to show that crime doesn’t pay. That battle is fought over who gets to interpret the past. Those who eventually manage to shape the Icelanders’ understanding of events and circumstances up to October 2008 will come to own the present – and eventually the political and financial future of Iceland.

*Landsbanki WUB claims that father and son – through Landsbanki, Straumur and related parties – controlled 73% of shares in Landsbanki and not only the 42% they held. Bjorgolfsson denies this on his website (only in Icelandic).

The Supreme Court ruling over Gudlaugsson is here (only in Icelandic). – There are two Court levels in Iceland: District Court – and – Supreme Court. I have earlier sometimes used High Court and County Court but it’s the same as DC and SC.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Fitch Ratings upgrates Iceland – outlook stable

The latest on Iceland from Fitch Ratings, positive this time:

-17 February 2012: Fitch Ratings has upgraded Iceland’s Long-term foreign currency Issuer Default Rating (IDR) to ‘BBB-‘ from ‘BB+’ and affirmed its Long-term local currency IDR at ‘BBB+’. Its Short-term foreign currency IDR has also been upgraded to ‘F3’ from ‘B’ and its Country Ceiling to ‘BBB-‘ from ‘BB+’. The Outlooks on the Long-term ratings are Stable.

‘The restoration of Iceland’s Long-term foreign currency rating to investment grade reflects the progress that has been made in restoring macroeconomic stability, pushing ahead with structural reform and rebuilding sovereign creditworthiness since the 2008 banking and currency crisis,” says Paul Rawkins, Senior Director in Fitch’s Sovereign Rating Group.

“Iceland has successfully exited its IMF programme and gained renewed access to international capital markets. A promising economic recovery is underway, financial sector restructuring is well-advanced, while public debt/GDP appears to be close to peaking on the back of a robust fiscal consolidation programme” added Rawkins.

As the first country to suffer the full force of the global financial crisis, Iceland successfully completed a three-year IMF-supported rescue programme in August 2011. Despite some setbacks along the way, the programme laid the foundations for renewed access to international capital markets in mid-2011 and an encouraging rebound in economic growth to 3% for 2011 as a whole. Flexible labour and product markets and a floating exchange rate have facilitated the correction of external imbalances and contained the rise in unemployment, while the financial system has shrunk to one fifth of its former size.

Iceland has been among the front runners on fiscal consolidation in advanced economies: the primary deficit has contracted from 6.5% of GDP in 2009 to 0.5% in 2011 and Iceland appears to be on track to attain primary fiscal surpluses from 2012 and headline surpluses from 2014.

Fitch believes that gross general government debt may have peaked at around 100% of GDP in 2011 (excluding potential Icesave liabilities); net debt is significantly lower at around 65% of GDP, reflecting appreciable deposits at the Central Bank (CBI). Barring further shocks, Iceland should see a sustained reduction in its public debt/GDP ratio from 2012, assuming economic recovery continues and the government adheres to its medium term fiscal targets. Ample general government deposits at the CBI and record foreign exchange reserves ameliorate near-term fiscal financing concerns.

However, the risk of additional contingent liabilities migrating to the sovereign’s balance sheet remains high. Iceland’s unorthodox crisis policy response has succeeded in preserving sovereign creditworthiness in the face of unprecedented financial sector distress. However, legacy issues remain, notably the protracted dispute over Icesave, an offshore branch of the failed Landsbanki that accepted foreign exchange deposits in the UK and the Netherlands, and the slow unwinding of capital controls imposed in 2008.

The impact of Icesave on Iceland’s sovereign creditworthiness has diminished over time and Landsbanki has begun to remunerate deposit liabilities. Nonetheless, Fitch considers that Icesave still has the capacity to raise public debt by 6%-13% of GDP, should an EFTA Court ruling go against Iceland. Resolution of Icesave will be important for restoring normal relations with external creditors and removing this uncertainty for public finances.

Capital controls continue to block repatriation of USD3bn-USD4bn of non-resident investment in ISK-denominated public debt and deposit instruments. Fitch acknowledges that Iceland’s exit from capital controls promises to be lengthy, given the underlying risks to macroeconomic stability, fiscal financing and the newly restructured commercial banks’ deposit base.

So far, Iceland has been relatively unaffected by the eurozone sovereign debt crisis and, although growth is expected to slow to 2%-2.5% in 2012-13, Fitch does not expect Iceland to slip back into recession. However, the private sector remains heavily indebted – household debt exceeds 200% of disposable income and corporate debt 210% of GDP – highlighting the need for further domestic debt restructuring, while the key export sector has been held back by capacity constraints and a lack of investment exacerbated in part by the slow unwinding of capital controls.

Fitch says that future sovereign rating actions will take a broad range of factors into account including continued economic recovery and fiscal consolidation and progress towards public and external debt reduction. Iceland is still a relatively high income country with standards of governance, human development and ease of doing business more akin to a high grade sovereign than low investment grade. Accelerated private sector domestic debt restructuring, a progressive unwinding of capital ontrols, normalisation of relations with external creditors and enduring monetary and exchange rate stability would help to further advance Iceland’s investment grade status.

Additional information is available at www.fitchratings.com

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

(Yet another) forex loans earthquake in Iceland

Yesterday, the Icelandic High Court ruled in a case related to a forex loan. The ruling stipulates that although the loan contracts have been declared void and nil and unconstitutional in an earlier ruling the foreign interest rates should still apply to these loans. If this ruling will constitue an example it means bingo and bonanza to those who took out forex loans: instead of paying Icelandic interest rates of up to 20% they only have to pay 2%-5%, depending on the currency, most commonly CHF and yen.

In a log on an earlier forex loan ruling I wrote that the interest rates were still unclear but the borrowers could hardly expect to get the windfall of paying only the foreign interest rates. I was totally wrong. This is exactly what the new ruling states. The Court – or four out of the seven judges who ruled – came to the conclusion that the loan’s interest rates should prevail. The ruling goes against common sense in the sense that no bank would have lent money on these terms but well, common sense and High Court ruling don’t alway go together.

It’s still early days, the financial institutions will be mulling over this but it’s clear that after recalculating thousands of loans – in the wake of previous rulings – the work will most likely commence yet again. This time, the ruling seems to imply a huge payout for the banks. Soothing voices in Iceland say that this will not bankrupt the banks.

While those who took out forex loans might rejoice those who took out Icelandic-only indexed loans will see themselves as losers. No doubt the banks shudder at the thought that this might create a political pressure to “correct” this difference for those with the latter loans. Such voices are already being heard.

The ruling itself gives a nourishing food for thought for the legal profession. Earlier, the High Court had ruled that the Emergeny Act from Oct. 6 2008 was legal although it’s retroactive. This time the Court rules that setting new interest rates would be retroactive and interfere with the property rights in the Constitution’s paragraph 72 – even though it has already ruled that certain types of the forex loan contracts are nil and void because they are unconstitutional. – Or, not being a laywer this is my understanding.

If this new ruling turns out to be bingo and bonanza to certain borrowers the legal profession will also get something to chew on here.

*The new ruling is here, in Icelandic.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

New Zealand worries over Chinese investment in dairy farms

Icelandic authorities recently vetoed the sale of land in the Icelandic inland to a Chinese billionair, Huang Nubo. That case is indeed still milling on. The latest is that the adjacent municipalities are exploring the possibility of buying the land, with a loan from Nubo, to rent it out to Nubo.

But it’s not only in Iceland that Chinese investment is met with some skepticism.

This week, the High Court in New Zealand halted a planned sale of dairy farms to Chinese investors. The reason for the ruling is that the High Court claims the New Zealand government overstated the economic benefits the Chinese investment would bring when it allowed the sale some 16 months ago. The ruling isn’t prohibiting the sale per se but puts onus on the government to review the evaluation with stricter criteria. The court case was brought by some Australian farmer and a banker who were outbid by the Chinese investor.

It’s all familiar to Icelanders: the supporters of the sale say it brings much needed foreign investment into the dairy sector that’s anything but prosperous. Those against it says it runs against Australian interests to sell farmland. Quite interestingly the buyer in spe is a company run by a property developer called Jiang Zhaobai. As in the case of Nubo’s company property in China is notoriously difficult to evaluate.

*Previous Icelogs on the Nubo sale are here and here.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

The CBI: as steady as a weather vane?

A good way to inspire trust is to make sensible plans and stick to them. In November last year the Icelandic Central Bank outlined a plan to work towards the abolition of the capital control. According to the CBI’s press release, “the Central Bank of Iceland will hold foreign exchange auctions in which it will purchase foreign currency in exchange for Icelandic krónur to be used for domestic investment, provided that the investment remains in Iceland for a long-term commitment period… The Central Bank’s aim with the transactions is to facilitate the removal of the capital controls without causing major exchange rate or monetary instability or jeopardising financial stability.”

This plan, built on a liberalisation strategy announced March 25 2011, was clear-cut, straight and simple, aiming at financial stability. The theory was that this would gradually make the offshore rate and the onshore rate converge, in the sense that the offshore rate would approach the onshore rate.

The CBI badly needs foreign currency and an auction last summer was a failure. The only buyers were Icelandic pension funds – not terribly prudent of them to be selling off foreign assets – but they were clearly under pressure to step in.

But now it turns out that the CBI only has a plan until it conjures up another one. In a daily note (in Icelandic) on Feb. 3 the financial analysts at Islandsbanki pointed out that after a failed auction last summer and a most remarkable deal at the end of last year with an unknown foreign seller the bank was still short of €130m.

In this unexpected and inexplicable deal, the CBI bought Icelandic sovereign bonds for ISK18bn, €111m – and paid for it in foreign currency. As is scarily obvious, this deal, not a trivial one in terms of size, goes completely against the bank’s plan from last year.

At an auction on Feb 15 the bank intends to buy €100m from pension funds and from foreigners wanting to invest in Iceland, by making use of the so called 50/50 way: foreigners (not Icelanders) can use offshore ISK as half of any investment made in Iceland; the rest has to be in foreign currency.

So far, the 50/50 way hasn’t aroused much interest and the pension funds might be squeezed again. It could even be argued that the funds’ foreign assets will be used to finance the deal with this mysterious seller. A seller who was deemed to be of such importance that he got paid in foreign currency that that bank is sorely lacking.

At a press conference recently, CBI governor was asked about this deal. He claimed it was an entirely regular affair, it had been a good offer but the bank would not give any information on the mysterious buyer; such information was never public. – According to rumours, CBI staff had no inkling of the deal until it was done. It seems that in accordance with a tried and tested Icelandic management style, the CBI governor didn’t much confer with staff regarding this move.

The question is how anything can be a good offer if you are selling what you really need more of, not less? And when part of the cost is diminished trust? Whose offer was so good that the governor gladly accepted to ignore the bank’s policy?

After this event it is only fair to say that the CBI has a plan to abolish the capital controls but it doesn’t stick to it. Its course towards abolishing the controls isn’t straight but crooked. So much for the vital need of a central bank to be seen as trustworthy.

*If anyone has information on this mysterious deal and who was lucky enough to sell ISK assets to the CBI against currency I would love to know.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

The Icelandic pension funds, the banks and their main shareholders – still too many unanswered questions

The Investigative Committee on Pension Funds, ICPF, sat up at the behest of the Icelandic Association of Pension Funds, LL, had a hard act to follow, producing a report that would be as thorough and informative as the Special Investigative Committee. The SIC was set up by the Icelandic Althing to investigate the collapse of the Icelandic banks. In short, the ICPF hasn’t addressed the issues nearly as sharply and comprehensively as many had hoped for.

To be fair, the ICPF didn’t have the same wide access to material and sources as the SIC since it was working on behalf of the LL and not Althing. However, that doesn’t excuse the lack of sharp questions and focus on the relevant topics. With a sharper focus and a clear definition of the most relevant issues a lot more could have been squeezed out the available material.

About eight out of 32 Icelandic pension funds hold around 70% of the funds’ assets. Consequently, it would have been relevant to focus on these seven funds and scrutinise their activities. Instead, all the funds are dealt with more or less evenly.

The report focuses on the losses made, in total ISK480bn, almost €3bn. The assets of the funds now amount to ISK1.909.498.621. These numbers are interesting but they are not new and could already be gauged from stats available from the Central Bank. What is of great interest – and unfortunately not dealt with adequately in the report – is 1) why the funds were in general so sloppy when it came to covenants, an issue previously underlined on Icelog – and 2) why the funds took part in currency deals from which the funds incurred heavy losses, ISK36bn, €222m.

As to topics mentioned but not really dealt with is that commissions paid to funds abroad can’t be read from the funds’ financial statements. It would be interesting to know why that is the case – and to whom the commissions were paid. The reasoning behind many investments is quasi non-existent. It would be interesting to know why and what that says about decision-making at the funds.

Abnormally weak guarantees and covenants – and extended loans

An interesting case in point is when Kaupthing brokers sold a ISK1bn worth of bonds, €6m, for Bakkavor – whose major shareholders were two brothers, Agust og Lydur Gudmundsson who incidentally were also Kaupthing’s largest shareholders. These bonds were not secured by any operations and were used as a take-over fund for Bakkavor. The funds that bought these bonds bought the risk of shares at the price of bonds. A fabulous deal for Bakkavor and a truly lousy deal for the bondholders, the pension funds.

Also lacking here were clauses related to changes in relevant parameters such as capital. There were simply no proper covenants that would trigger a repayment of the loan in case there were significant changes affecting the status of the bond issuer. Neither the pension funds nor the banks showed any interest in more strict covenants.

This is all the more interesting when one keeps in mind that the banks did indeed operate abroad where pension funds would never have looked at such bonds. The question is why there was this difference? And who made the decisions on behalf of the pension funds? Were their fund managers too inexperienced? And is this way of doing things still thriving?

Because of these weak covenants the holding companies like Exista, Baugur and the other usual suspects could sweep up money from the pension funds. This practice has led to grotesque losses for the funds.

Out of total losses for the funds of ISK480bn, 90bn, €555m, stem from losses of corporate bonds and ISK100bn, €62m stem from bonds from financial institutions. Losses from shareholding amount the ISK199bn, €124m.

Losses related to the different business spheres are interesting: 44% of losses relate to Exista and related companies such as Exista, Kaupthing’s main shareholders, in total ISK171bn, €105m; 20% of the losses relate to the Baugur sphere, Glitnir’s main shareholders from mid 2007, or ISK77bn, €47m. For some reason, losses related to Landsbanki’s main shareholders Bjorgolfur Thor and his father Bjorgolfur Gudmundsson are not calculated but according to Visir (the media website owned by Jon Asgeir Johannesson of Baugur fame) losses attributed to the Bjorgolfsson’s sphere amount to ISK74bn, €46m.

An example of the report’s lack of perspicacity is its treatment of prolonged loans. It’s simply pointed out that increasingly new bonds, which were due, like bullet loans, on a single date, paid the bonds. This hid the fact that the bond issuers could not repay their loans. Again, this is only pointed out but there is no analysis as to why this practice became so prevalent and if this is still the case.

Incidentally, this trend follows what was happening at the banks: that the favoured borrowers were lent money to repay their loans, thus hiding the fact that they couldn’t or wouldn’t pay.

It’s already been pointed out on Icelog how the banks lent to holding companies, in reality turning them into banks without the risk management. By buying bonds from these companies, the pension funds did their part to make this possible.

The currency hedges

One of the issues, which expose the close ties between the banks and the pension funds, are the forex deals. Instead of holding on to their foreign assets, many pension funds actually sold their foreign currency towards the end, when the banks were seriously short on currency. The funds were led into believing that betting on a rising ISK was a wise thing to do because they had foreign assets they should be hedging. This view didn’t take into account that the foreign assets were in themselves hedged the Icelandic assets.

There was also a painful shortage of settlement provisions in the contracts concluded by the pension funds with the banks on management or purchase of currency hedges. International contracts on currency hedges usually have so-called ISDA terms and conditions, which describe in detail how they are to be dealt with in the case of flawed assumptions on the part of the contracting parties.

It is quite clear that the funds were easily swayed by the banks into these disastrously bad deals. Here, a much greater digging is needed. Why did the pension funds agree to these deals? Who convinced them? Was this really in the interest of the pension funds? What was the motivation – and last, but not least, what there the relations between fund managers at the pension funds and the banks?

Iceland is a small society and personal relations run back and forth there, as in other small societies. There are plenty of rumours and stories about pension fund managers and fund employees being wined and dined and pampered home and abroad by the banks and the companies from whom they bought bonds. Unfortunately, this aspect isn’t explored.

As said earlier, only a handful of the funds hold the largest part of the Icelandic pension funds’ assets. Each fund had perhaps two or so fund managers – in total, 10-20 people were the key people during the last few years before the collapse of the banks. It wouldn’t have been overly complicated to map their relationships to the banks, check on “revolving doors” etc. But that wasn’t done and consequently the whole saga isn’t told in this report.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.