Search Results

OSP brings charges in the al-Thani case (updated)

The Office of the Special Prosecutor in Iceland has now brought charges in the so-called al-Thani case. In September 2008 Kaupthing announced that a Qatar investor, Mohamed bin Khalifa al-Thani, had bought just over 5% of share in Kaupthing. It later turned out that al-Thani wasn’t risking his own money but Kaupthing’s fund: the bank lent him money to buy the shares. A familiar pattern but this was an important statement because it made the bank seem like a good investment. The interesting thing is that according to documents from Kaupthing Deutsche Bank was involved in the al-Thani investment scheme.

Those charged now are the bank’s CEO Hreidar Mar Sigurdsson, Chairman Sigurdur Einarsson, Kaupthing Luxembourg manager Magnus Gudmundsson and the second largest shareholder in Kaupthing Olafur Olafsson. They are all charged with market manipulation. Sigurdsson and Einarsson are seen as the organisers and are in addition charged with breach of fiduciary duty. Olafsson and Gudmundsson are charged for participation in this breach and Olafsson is in addition charged for money laundering.

The charges are not public yet. Those four now charged are all living abroad. Olafsson has sent out a statement denying the charges. Sigurdsson says he is disappointed and holds on to the official story from September 2008: the sale was genuine and the sheikh did indeed risk his money.

*A blog on the al-Thani case will be coming here soon. Here are earlier blogs referring to the al-Thani case. – The OSP writ can be read here, only in Icelandic.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

The still untold story of the Kaupthing loan

Of the known unknowns of the Icelandic banking collapse in early October 2008, the most intriguing story is the €500m emergency loan issued to Kaupthing by the Icelandic Central Bank. In the early hours of 6 October 2008, the prime minister and other leading ministers had realised that the only thing to do was to put in place the Emergency Act, enabling the authorities to take over the banks. Yet, on that same day, the CBI shovelled €500m from the fast depleting foreign currency reserve into Kaupthing although the governor of the CBI at the time did not believe Kaupthing would ever be able to repay the loan. The CBI has now published a much delayed report on the loan: it leaves all the fundamental questions unanswered and adds one question to the sorry saga: is it ever a good idea to let an organisation investigate itself?

“What are we doing? We are deciding we’re not paying the debt of spendthrifts… We are not going to pay other people’s debts. We are not going to pay debt of the banks that have been somewhat reckless.’ This is how the then governor of the Central Bank, Davíð Oddsson, explained in an interview 7 October 2008 the drastic measures Icelandic authorities had taken with the Emergency Act the day before.

The governor was also asked about a certain loan to Kaupthing. He explained that the information had been made public by mistake the previous day; a so-called bridge loan amounting to €500m to be repaid in a few days. In the unlikely circumstances that the bank would default on the loan, the CBI had a good collateral, the Danish FIH Bank, a Kaupthing subsidiary.

The day before appearing on television, the governor had described this loan rather differently. In a telephone conversation with then prime minster Geir Haarde, Oddsson sought the agreement of the prime minister for the loan, which they had apparently discussed earlier.

Intriguingly, Oddsson made the call not from his office but the office of another employee, where Oddsson knew the call could be recorded. That recording remained a mystery for years as the CBI refused to release it, claiming it contained sensitive information. In November 2011, Morgunblaðið, where the editor is a certain Davíð Oddsson, published a transcript of the call. Haarde expressed his annoyance but no measures were taken against the paper for the publication of material it could not explain how it had obtained.

In the phone call 6 October 2008, Oddsson emphasised that the loan was risky and would most likely be of some relief for Kaupthing for only four or five days, adding: “I don’t expect we will get this money back. They say they will repay us in four or five days but I think that’s untrue or let’s say wishful thinking.”

That inkling proved to be correct – less than 48 hours after receiving the loan, Kaupthing was in default. Neither Oddsson nor Haarde have ever explained why the loan was issued.

Now a report (only in Icelandic) on the loan saga, published by the CBI 27 May shows that there is no documentation to be found at the CBI on the loan: nothing that explains why the loan was issued, what it was intended for nor properly how Kaupthing made use of it. Worse is, that the new report fails standards set in other reports, most recently a report on how Kaupthing was bought in 2003 on false premises. The obvious question is: was it ever justified that the CBI would write a report on its own deeds?

The unannounced report and its unclear goal

In the new report, CBI governor Már Guðmundsson says in his preface that the work on the report started four years ago. As far as I can see, there is no press release on the CBI website to announce that the CBI is now embarking clarifying its €500m loan to Kaupthing nor has this ever been mentioned in the bank’s annual reports.

When I checked my emails, I can see that I first heard about the report in late 2016: I wrote to the bank’s spokesman in November 2016 asking him about the report I had then just heard Guðmundsson mention in the media, also when it could be expected. The answer was that the bank was waiting for the final results of the sale of the FIH. I mentioned that the sale, which was obviously going to incur losses for the bank, was the result of the loan – the interesting bit was why the loan was issued.

Over the years, my inquiries into the report-in-making have usually been answered by pointing out that the final result of the FIH sale – which happened in 2010 – was still due.

In his preface, governor Guðmundsson writes that since the collapse, the bank has been focused on the present and the future, rather than the past. Also, that the FIH sale had been a complicated issue and those working on it had been very busy doing other things. I have to say that I find it beneath the dignity of the bank to explain the long conception time by saying that CBI employees have been busy. It just gives the sense that this report was far from any priority at the CBI.

From the preface, it is clear that to begin with the report was meant to focus on the loss-incurring FIH sale. Only after receiving a query from prime minister Katrín Jakobsdóttir as late as November 2018 on how Kaupthing made use of the loan, i.e. where the funds flowed, the bank had set about to make inquiries to clarify this issue.

This indicates that there was no proper plan to begin with but to focus on the FIH sale, not on the real issue: why did the CBI lend Kaupthing €500m when the governor was clear the loan was a risk and would not be repaid?

No paper trail, no documentation at the CBI

As pointed out in the CBI report there is indeed no paper trail of the loan, no documentation, nothing, at the bank. The report emphasises that everything regarding the loan seems to have been planned outside the bank. Therefore, the report has nothing to add on why the loan was issued, why the loan figure was €500m, what it was intended to do etc.

There have been indications earlier, that the documentation regarding the loan, the collateral, interest rates etc. was only made some days after the loan was issued, i.e. that the loan document was back-dated. Again, this is not mentioned in the CBI report and what exactly is on paper is not clear. It is however clear that there is no paper trail as to how the loan came into being, i.e. there is a lacuna at the bank regarding this loan, which the governor at the time suspected, so as not to say knew, would not be repaid.

The report states that decisions regarding the Kaupthing loan were taken outside of the bank, explaining the lack of documentation at the bank. However, it does not make it entirely clear if ever there was a documentation, which then has disappeared or if there really never were any documents at all in the bank.

Since the lacuna must have been clear from early on, the CBI knew from early on that by only focusing on documents in the bank, nothing much would come out of its investigation. Why it did not try to turn to other sources, such as the FME, which took a back-up of all the banks right after they failed or the Kaupthing estate, indicates that publishing a report with nothing in it, did not feel too disturbing.

Where did the loan end up?

Already in earlier criminal cases against Kaupthing managers, notably the CLN case, evidence emerged as to how some of the €500m were used, or rather how funds were allocated on 6 October 2008 as the collapse of Kaupthing was imminent. There has however not been any comprehensive overview of transactions in Kaupthing these days, i.e. how did Kaupthing allocate funds from 6 October 2008, when the loan was issued.

Interestingly, we know that as the bank was stumbling to default, the Kaupthing managers had their eyes on making payments to fulfil the bank’s obligations in the CLN transactions, in total €50m. Also, Kaupthing issued a loan to a company called Lindsor Holding Corporation, a total of €171m. Lindsor was owned by some Kaupthing employees and amongst other things used to buy bonds from Skúli Þorvaldsson, an Icelandic businessman living in Luxembourg, with strong ties to Kaupthing. This diminished Þorvaldsson’s losses but increased Kaupthing’s losses.

Lindsor is the only Icelandic entity being investigated by Luxembourg authorities. Over two years ago it seemed that criminal charges might soon be brought in that case but since then, total silence. Yet another example of the extreme lethargy in the Duchy when it comes to investigating banks (see here blogs related to Lindsor).

The CBI report mentions these two loans but in its overview of outgoings it does not list the Lindsor loan, only the CLN transactions. This, in addition to the single highest payment €225m to deposit holders in Kaupthing Edge, €170m to Nordic central banks, €42m REPO payments to two European banks, €203m in foreign currency transactions – and then, the only novelty in the CBI report: 400-500 “small transactions” according to the CBI report, i.e. lower than €10m, in total €114,5m.

It is not clear why the Lindsor loan is mentioned but not added to the list. Also, there is no further information regarding the “small transactions” – who were the beneficiaries, individuals or companies, who owned the companies, how many transactions at around €8 to €10m etc.?

A bank is rarely a good collateral

In his preface, governor Már Guðmundsson concludes that in hindsight, the lending was miscalculated. However, the lending was not miscalculated only in hindsight: the governor at the time did not believe the loan would ever be repaid.

Governor Guðmundsson also claims that one lesson from the Kaupthing loan saga is that shares in a foreign bank do not constitute a good collateral. In my opinion, this is too limited a lesson: a bank, domestic or foreign, is not a good collateral.

In evaluating collateral, not only its monetary value is of importance but also how quickly and easily it can be sold. A bank makes a bad collateral as it can hardly ever be a quick sale and it is also costly to sell. For good reasons, central banks do not normally accept a bank as a collateral; they prefer assets that can be sold easily and quickly at not too high a cost.

I have not scrutinised that part of the report, which deals with the loss-incurring sale of the FIH bank as I have very little insight into that story. The sale itself turned into quite a saga in Denmark, covered by the Danish media.

Poorly planned and sloppily executed work

To my mind, it is beneath the dignity of the bank to publish this report as so much is lacking. The long time it took to write it cannot be excused by CBI employees being busy; it just shows that writing the report was never a priority.

If the CBI concluded it did not have the authority to ask for further information, it should have turned to the Prime Minister Office to suggest the report should be written by someone with the proper authority to do so. Indeed, it is a fundamental question why the CBI was allowed to handle this investigation, an untrustworthy move from the beginning.

Almost eleven years after the banking collapse in early October 2008, one key story of these days is still untold. The CBI is clearly uninterested in the story. The question is if the political powers in Iceland are equally uninterested.

*I have long been interested in this loan, see here a blog from 2013 on the CBI loan to Kaupthing.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

The two Al Thani cases, Qatari investors and Western banks

At the height of the banking crisis in 2008, Qatari investors stepped in to invest in two European banks – Barclays and Kaupthing. Later, these investments were and are the focus of criminal charges, not against the investors but the bankers, who orchestrated the investments. Both cases show that the Qatari investors were intent on profiting not only from the investments but also from hidden fees and sham arrangements. “A sham agreement requires two parties;” if the defendants were dishonest, so were the other party, the Qatari investors,” said Justice Jay during the Barclays trial recently. – This is not only relevant in connection to stories from 2008 but raises impertinent questions regarding Qatari investments in Deutsche Bank and other banks.

In autumn 2008, many Western banks were forced to seek emergency loans from governments. Three banks – Barclays, Deutsche Bank and Credit Suisse – were boastful of the fact that they did not need government funding. As has now become abundantly clear, all three tapped heavily into US measures to save US banks and foreign banks operating in the US. Even more to brag about was the fact that Barclays and Credit Suisse were able to raise funds in the market: Qatari investors were crucial in saving the two banks. Admittedly investment at a high price but these were singularly difficult times.

The Barclays investors were two Royal Qataris. Sheikh Hamad bin Jassim bin Jabr Al Thani, at the time Qatari’s prime minister, also known by his initials, HBJ. In 2013, The Independent dubbed him “the man who bought London” where he has invested both through his private companies and Qatar Investment Authority, QIA. His co-investor was Sheikh Mohammed Bin Khalifa Al Thani who in 2008 also invested in Kaupthing. Barclays paid them £66m for bringing along Sheikh Mansour Bin Zayed al Nahyan, well known in the UK for high octane investments such as Manchester City Football Club, another 2008 investment of his.

The Barclays Qatar story took a different turn in 2012 when the Serious Fraud Office, SFO, opened a criminal investigation into the Barclays deal with the Qataris: the price for the investment was even higher than previously disclosed as Barclays had kept quiet about two “Advisory Services Agreements.” On the basis of these agreements, Barclays paid the Qatari investors and Sheikh Mansour £322m; allegedly, no advice was given. The four Barclays bankers – Barclays CEO at-the-time John Varley and then-senior executives Roger Jenkins, Richard Boath and Tom Kalaris – who orchestrated the payments are now fighting criminal charges in court. Intriguingly, charges against Barclays PLC concerning a loan of $3bn to the Qatari investors were dismissed last year by the High Court.

In Iceland, the Special Prosecutors has exposed another Qatari investment saga, at the core of a criminal case against three Kaupthing bankers and the bank’s second largest investor. It turned out that a Qatari investment in Kaupthing in September 2008 was entirely funded by Kaupthing. Sheikh Khalifa was not charged but charges brought against three Kaupthing bankers and Ólafur Ólafsson, the second largest shareholder at the time, all of them sentenced to lengthy prison sentences.

Now, to the plights of Deutsche Bank. It survived 2008, much thanks to US funding but in 2014 Deutsche Bank was lacking capital; luckily, Sheikh Hamad bin Jassim bin Jabr Al Thani and Sheikh Mohammed Bin Khalifa Al Thani started investing in the bank, eventually becoming the bank’s largest investors. Now, as the German government hopes that a merger between two weak banks, Deutsche Bank and Commerzbank, might (contrary to evidence and experience) make a strong bank, the Qatari investors have indicated they might be ready to invest further.

Intriguingly, two criminal cases regarding Qatari investments show hidden deals the banks did with the Qataris to meet their demands for benefits beyond what investors could normally expect. The question is if these hidden favours were only relevant for these two cases – or if they are general indications of Qatari investors’ preferences in doing deals. If so, it raises questions regarding other Qatari investments in European banks.

Kaupthing and the Qatari investment in September 2008

After a tsunami of bad news in 2008, the one good news for Kaupthing came in September, miraculously a week after the collapse of Lehman Brothers: Sheikh Mohammed Bin Khalifa Al Thani, of the Qatari ruling family, had privately invested in Kaupthing. The investment amounted to 5.01%, just above the 5% threshold that triggered a notification to the Icelandic stock exchange, securing media attention. This investment made the Sheikh Kaupthing’s third largest investor and the only major foreign investor.

In a statement, the Sheikh claimed he had followed Kaupthing closely for some time and was satisfied of its performance and good management team. Chairman of Kaupthing Sigurður Einarsson said at the time that the bank’s strategy to diversify the shareholder base was paying off. To Icelandic media Kaupthing’s CEO Hreiðar Már Sigurðsson said this showed investors had faith in the bank.

But this investment was not enough to save the bank: in the second week of October 2008, Kaupthing collapsed, together with 90% of the Icelandic financial system.

The Kaupthing undisclosed loan and fees behind the Qatari investment

Only months later, rumours were circulating that the Qatari investment in Kaupthing had not been quite what it seemed to be. In April 2010, when the Icelandic Special Investigative Commission, SIC, published its report one of its many colourful stories recounted the reality behind this Qatari investment in Kaupthing: it had been entirely funded by Kaupthing and Sheikh Mohammed Bin Khalifa Al Thani had apparently only lent his name to this Kaupthing PR stunt. The go-between was Ólafur Ólafsson, Kaupthing’s second largest investor.

The mechanism was that Kaupthing lent funds to an Icelandic company owned by the Sheikh. In addition, Kaupthing issued a loan of $50m, labelled as advance profit, to another company owned by the Sheikh. The three Kaupthing bankers involved in the transaction – Hreiðar Már Sigurðsson, Sigurður Einarsson and Kaupthing Luxembourg’s director Magnús Guðmundsson – and also Ólafur Ólafsson were charged for breach of fiduciary duty and market manipulation and sentenced to between three and five and half years in prison (further on Icelog on the Icelandic al Thani case). Although the case was called “the Al Thani case,” the Sheikh was not charged with any wrongdoing.

Kaupthing had further plans of joint ventures with the Sheikh. In summer 2008 there had been an announcement, duly noted in the Icelandic media, that the Sheikh was investing in Alfesca, owned by Ólafsson. According to the SIC report, also here the plan was that Kaupthing would finance Sheikh Al Thani’s Alfesca investment.

In August and September 2008 Kaupthing, advise by Deutsche Bank, financed credit linked notes, CLN, transactions linked to Kaupthing’s credit default swaps, CDS, in order to influence, or rather manipulate, the CDS spreads. Two rounds of transactions were carried out: first via companies owned by a group of Kaupthing clients, then on behalf of Ólafur Ólafsson. A third round was planned, via a company owned by Sheikh Mohammed Bin Khalifa Al Thani, mimicking the earlier transactions, again with Deutsche Bank. Neither the Sheikh’s involvement with Alfesca nor the CDS trades happen as Kaupthing had run out of time and money (further on the CDS saga, see Icelog).

Barclays and Qatari investors in June and October 2008

Kaupthing was a small fry in the financial ocean, Barclays a much bigger fish. Already in spring of 2008, funding worries at Barclays were rising – the share price was falling, market conditions worsening. As Marcus Agius, Barclays chairman of the Barclays’ board 2006 to 2012, recently a witness for the prosecution in the criminal case against the four Barclays bankers, explained in court 19 February 2019, Barclays wanted to be ahead of the market, i.e. adequately capitalised: in the summer of 2008 it was time to raise capital, in fierce competition with other banks.

Consequently, Barclays decided to raise capital and underwriting was arranged. As summerised in Barclays 2008 Annual Report: On 22nd July 2008, Barclays PLC raised approximately £3,969m (before issue costs) through the issue of 1,407.4 million new ordinary shares at £2.82 per share in a placing to Qatar Investment Authority, Challenger Universal Limited (a company representing the beneficial interests of His Excellency Sheikh Hamad Bin Jassim Bin Jabr Al-Thani, the Chairman of Qatar Holding LLC, and his family), China Development Bank, Temasek Holdings (Private) Limited and certain leading institutional shareholders and other investors, which shares were available for clawback in full by means of an open offer to existing shareholders. Valid applications under the open offer were received from qualifying shareholders in respect of approximately 267 million new ordinary shares in aggregate, representing 19.0 per cent. of the shares offered pursuant to the open offer. Accordingly, the remaining 1,140.3 million shares were allocated to the various investors with whom they had been conditionally placed.

The Qatari investors were new to Barclays. At the time, Barclays’ top management saw it as highly beneficial for the bank to attract major investors from the Middle East, according to Agius. Keen to expand, the bank aimed at being a global player. The Qatari connection fitted the bank’s vision of its goal in the international world of finance.

The second round in autumn 2008 – the “tart” and the Sheikh

In autumn 2008, market conditions went from worrying to worse than anyone had thought possible, according to Agius’ witness statement in court. There were only two options: accept state funding or try another capital raising. Barclays hoped to again raise capital from the Qataris.

This time, the Qataris brought another Middle Eastern investor to the table, Sheikh Mansour Bin Zayed al Nahyan. Interestingly, there was some confusion if an Abu Dhabi public body was investing or if Sheikh Mansour was investing privately as Barclays publicly stated to begin with. In the end, the investor turned out to be International Petroleum Company where Sheikh Mansour was a chairman.

The Abu Dhabi investment saga is an even more colourful financial thriller than the Qatari saga. An independent financier Amanda Staveley advised Sheikh Mansour and got at least 30m of the £110m Sheikh Mansour allegedly got in fees from Barclays. In addition, Staveley’s company has sued Barclays for fees of £720m plus interests and cost, potentially well over £1bn,in relations to Sheikh Mansour’s investment. Her case is on hold until the criminal case against the Barclays four is brought to an end.

Somewhat ungracefully, the Barclays bankers referred to Staveley as a “tart” in a telephone recording played at the Southwark County Court recently during the Barclays trial. Intriguingly, this name-calling came from one of the charged bankers, Roger Jenkins, who argued for £25m bonus for 2008 as he had been instrumental in bringing in the Sheikhs, rather belittling Staveley’s part in it.

Barclays’ cash call of £6.1bn in times of panic

There was panic in the autumn air of 2008. Barclays fought to raise capital in order to avoid making use of the 8 October 2008 banking package, in total a staggering £500bn on offer from the government; for comparison, the total government annual spending was 618bn. One condition: participating banks would have to sign up to an agreement with the FSA on executive pay and dividend, making it rather unappealing for the well-paid Barclays bankers.

After some hesitation from the Gulf investors – they allegedly left the negotiations but returned – the bank could finally put out an innocuous statement on 31 October 2008 that Barclays had “held discussions in recent days with Qatar Holding LLC and entities representing the beneficial interests of HH Sheikh Mansour Bin Zayed Al Nahyan (“the Investors”) who agreed … to invest substantial funds into Barclays.”

As summerised in Barclays 2008 Annual Report, Barclays would issue “£4,050m of 9.75% Mandatorily Convertible Notes (MCNs) maturing on 30th September 2009 to Qatar Holding LLC, Challenger Universal Limited and entities representing the beneficial interests of HH Sheikh Mansour Bin Zayed Al Nahyan … and existing institutional shareholders and other institutional investors. If not converted at the holders’ option beforehand, these instruments mandatorily convert to ordinary shares of Barclays PLC on 30th June 2009. The conversion price is £1.53276 and, after taking into account MCNs that were converted on or before 31st December 2008, will result in the issue of 2,642 million new ordinary shares.”

Further, Barclays issued warrants on 31 October 2008 “in conjunction with a simultaneous issue of Reserve Capital Instruments [RCI] issued by Barclays Bank PLC … to subscribe for up to 1,516.9 million new ordinary shares at a price of £1.97775 to Qatar Holding LLC and HH Sheikh Mansour Bin Zayed Al Nahyan. The warrants may be exercised at any time up to close of business on 31st October 2013.” – Qatar Holding now held 6.4% of Barclays shares.

Expensive and unpopular funding

Fund raising in these tumultuous times, as banks were scurrying for government money, might have looked like quite a feat. But the reception to Barclays fundraising was disappointing: the news came as a surprise to the market and existing shareholders were dismayed; also because the fund raising had not been a normal process, Agius said in court.

Reaching the agreement with the Sheikhs had been tough. In an email to Roger Jenkins John Varley said the Qataris and Sheikh Mansour had had “too good a deal.” It did in fact prove difficult to get shareholders to agree; many of the smaller shareholders were very upset.

At least one large shareholder in Barclays voiced concern publicly: though at the time not knowing how high the cost was indeed for Barclays, the pension fund Scottish Widows claimed the capital raising had been driven through at a high cost, just to avoid state ownership and its effect on bonuses. However, by the end of November Barclays shareholders had agreed to the capital raising.

In his foreword to the Barclays 2008 Annual Report, Agius acknowledged the anger the capital raising had caused among shareholders: “…we also recognised that some of our shareholders were unhappy about some aspects of the November capital raising. This unhappiness is a matter of great regret to us.” Further, Agius set out to explain the process and the great care taken by the board to make these difficult decisions “…as we sought to react to the circumstances prevailing at the time. The Board regrets, however, that the capital raising denied Barclays existing shareholders their full rights of pre-emption and that our private shareholders were not able to participate in the raising.”

It was indeed an expensive undertaking: the official terms seemed quite generous, 2% on the RCIs, 4% on the MCNs, as Agius pointed out in court. The RCIs carried interests of 14% until June this year, 2019, (see 2008 Annual Report p.228) when the rate would be 13.4% on top of three months LIBOR. The initial coupon was deemed to carry a cost of 10% after tax for Barclays. In addition, there was a disclosed fee of £66m to the Qatari investors, for having introduced Sheikh Mansour.

The undisclosed fees of £322m for the Sheikhs – and a Barclays loan to the investors

What Agius and others at the bank say they did not know was that the cost of extracting investment from the Qatari and Abu Dhabi Sheikhs were even higher than disclosed. The four Barclays bankers agreed to fees totalling £322m, to be paid over 60 months, hidden in two so-called “Advisory Services Agreements,” ASAs, now the focus of the SFO case against the Barclays four.

What transpires from the Barclays court case is that the three Sheikhs wanted fees for investing; the original figure floated was £600m. It was not trivial to dress up the agreed fee as anything remotely acceptable: after all, these three investors were getting fees no other investors were offered. When the “Advisory Services Agreements” surfaced in communication between the Barclays bankers and the Qataris negotiating on behalf of the Middle Eastern investors as a way for Barclays to pay the companies investing, it turned out that Sheikh Hamad bin Jassim bin Jabr Al Thani also wanted fees for his personal investment.

The bankers saw the absurdity in an ASA with a prime minister: he could not be an adviser to Barclays any more than a US president could be an adviser to JP Morgan! The solution was to increase the total payment for the ASAs to QIA: there would probably be some means to get the extra funds from QIA to its chairman, Sheikh Hamad bin Jassim bin Jabr Al Thani.

The thrust of the criminal case against the four Barclays bankers is if the fees were paid for real service, if any services were given in return for the exorbitant fees. So far, witnesses have not been aware of any services given; indeed, Agius and other witnesses were not aware of the ASAs until some years later, when the they surfaced in relation to the SFO investigation.

It is also known that the Qatari investors got a loan of $3bn from Barclays at the time, which is interesting given the Kaupthing story. This information surfaced in SFO charges against Barclays bank itself; this case was however dismissed in May 2018 by the Crown Court; in October 2018 the High Court ruled against SFO’s application to reinstate the case.

Deutsche Bank – another big bank at the mercy of Qatari investors

Deutsche Bank survived the 2008 crisis through the open funding route in the US. As Adam Tooze points out: In Europe, the bullish CEOs of Deutsche Bank and Barclays claimed exceptional status because they avoided taking aid from their national governments. What the Fed data reveal is the hollowness of those boasts.” Fed records show “the liquidity support provided to a bank like Barclays on a daily basis, revealing a first hump of Fed Borrowing during the Bear Stearns crisis and a second in the aftermath of Lehman (p.218).”

As time passed, the German bank behemoth, weighed down by falling share prices inter alia caused by scandals and fines for financial misdemeanour and sheer criminal acts in various countries, struggled to stay above required capital ratio. Already in 2014, there were news of Qatari investments in Deutsche Bank according to Der Spiegel: the deal in 2014 had been arranged by the then CEO of Deutsche, Anshu Jain. Of course, Jain knew Sheikh Hamas bin Jassim Bin Jabr Al Thani, one of the wealthiest and most influential men in the Gulf. The Sheikh had long been a valued Deutsche customer, even before the 2014 investment of €1.75bn in Deutsche made him one of the larger shareholders in Deutsche.

In autumn 2016, more was needed. Again, the Sheikh was ready to invest, this time with Sheikh Hamad Bin Khalifa Al Thani, the Kaupthing investor. The two surpassed BlackRock as Deutsche’s largest shareholders, via two investment vehicles, the BVI-registered Paramount Services Holdings Ltd and Supreme Universal Holdings Ltd., registered in the Cayman Islands, respectively owned by Sheikh Jassim and Sheikh Khalifa.

With the Kaupthing saga in mind, I sent some questions to Deutsche Bank in August 2016, asking if Deutsche knew how the Qatari shareholders had financed their investment in the bank, if Deutsche could guarantee that the bank was not lending the Qatari shareholders, or anyone related to them, the invested funds, entirely or partly, and if the Qataris were getting in dividend in advance or other benefits that might later arise from their investments.

On 25 August 2016, Deutsche’s spokesman Ronald Weichert gave the following answer:

Special agreements with individual shareholders would be a breach of the stock corporation act. We want to point out, that allegations or the mere assumption that the Supervisory Board or the Management Board could enter into such an agreement or could have entered into such agreement, are absolutely unfounded and is highly defamatory. There is absolutely no indication to justify such a reporting or any allegation of this kind.

In addition to the Icelandic Al Thani case, I pointed out that Deutsche had quite some track record in being fined or scrutinized for various illegal activities, which made the tone in the answer somewhat surprising and a tad misplaced.

In addition, I mentioned that the Qatari shares purchase in Deutsche Bank, at a crucial time for the bank, had intriguingly, been just high enough to be flagged (as with the Al Thani Kaupthing investment); exactly this fact had caused attention in the media in various countries, an interest reflected in my question. I was merely trying to understand the situation, based on what had transpired in Kaupthing and Barclays with Qatari investors.

Qatari networks in European banks, with a Chinese hint

As Der Spiegel pointed out, there have long been rumours about the origin of the fortune of Sheikh Hamas bin Jassim Bin Jabr Al Thani “some of which don’t cast a particularly flattering light on the sheikh…” He himself has mentioned that his wealth, “like that of all Qataris, may be questionable from a Western point of view. But according to Qatari standards, it was legitimate and had been obtained through legitimate business.” – And, as Der Spiegel noted, the Sheikh had a predilection for investing in the financial sector.

When the long-troubled Dexia sold Banque International a Luxembourg, BIL, in 2011, the Sheikh bought 90% of the shares via a Luxembourg company, Precision Capital, for €750m, with the remaining 10% going to the Luxembourg government, indirectly giving the bank a touch of state guarantee. BIL has offices in Switzerland, the Middle East and in Denmark, since 2000, and Sweden since 2016. In 2017, Precision Capital sold its holdings in BIL for €1.6bn, more than double the purchase price less than six years earlier.

The buyer was Legend Holdings, a Chinese investment fund with roots in the technology industry, best known as the owner of Lenovo Group. The Chinese fund enthusiastically touted its BIL acquisition as a new Chinese European co-operation and the fund’s gateway into Europe.

BIL is well connected in tiny Luxembourg: the chairman of the board is Luc Frieden, former minister for various ministries in Jean-Claude Juncker’s governments, last minister of finance 2009 to December 2013 when both Juncker, now president of the European Commission since 2014 and Frieden left Luxembourg politics. After politics, Frieden joined Deutsche Bank as vice chairman in 2014. Based in London, he advised the bank on international and European matters, as well as being chairman of Deutsche’s supervisory board in Luxembourg, until he joined BIL’s Board in early 2016, a post he kept after Legend Holdings became the bank’s largest shareholder.

In 2012, Precision Capital also bought a Luxembourg banking group, KBL European Private Bankers, which owns seven small banks and asset managing firms spread over Europe. One of them is Merck Finck, with sixteen offices in Germany.

Legend Holdings purchase of BIL coincided with other Chinese companies buying into European banks. Fosun is now the largest shareholder in Portugal’s largest listed bank, Millennium BCP, holding 24% of its shares.

Most noticeable was however HNA Group interest in Deutsche Bank.The HNA Group, formerly Hanan Airlines, holds €83bn in global assets, mainly in hotels and airlines. HNA Group is not state-owned but its chairman, Chen Feng, is a member of the National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party. In 2017 HNA Group had suddenly become Deutsche’s largest shareholder, peaking with a shareholding of just under 10%. HNA Group announced in September 2018 it would sell its stake of 7.6% over the coming 18 months; it is no longer among the largest shareholders in Deutsche.

The Chinese interest in European banks has been a cause for concern and controversy, both in terms of political ties to Chinese authorities and in terms of management issues.

Deutsche Bank – more is needed, again the Qataris stand ready to invest

The 2014 purchase of Deutsche Bank shares was at the time seen as Sheikh Hamas bin Jassim Bin Jabr Al Thani’s most important strategic investment so far in European banks. In 2016, there had been rumours that the Qataris aimed at owning anything up to 25% of shares in Deutsche and were interested in exerting greater influence on the bank, which was not run to their taste. However, no such drastic steps were taken though the Sheikh showed support for Deutsche’s chairman, Paul Achleitner who faced criticism after the bank’s shares lost 50% of their value in early 2016.

The position of the largest shareholder in Deutsche has been wandering between a few firms. BlackRock had long been the largest shareholder until the investment by two Qatari-owned companies. In May 2017, the order changed as Deutsche raised capital. Although the two Qatari companies had been rumoured to be willing to increase their shareholding, they did not. Not then.

This was when the Chinese HNA Group replaced the two Qatar companies as the largest shareholder, holding just under 10%, a stake worth approximately €3,4bn. Shortly after the investment in Deutsche Bank, Hanan Group’s chairman Chen Feng visited Doha and met with Qatar dignitaries.

Now, BlackRock is again Deutsche’s largest single shareholder with 4.88%. However, the two Qatari companies, Paramount Services Holdings and Supreme Universal Holdings, each hold respectively exactly 3.05% and should for all practical purposes be seen as operating together, again making them the largest shareholder with 6.10%.

For years, Deutsche insiders have been searching for a turn-around plan for the bank without a clear success. Deutsche is now at a critical point: the echelons of power in Deutsche and the German government have come to the conclusion that the problem of two weak large banks – Deutsche and Commerzbank – will best be solved by merging them.

Again, Deutsche is in need of capital. It now seems that the public Qatar entity, QIA, stands ready to invest in Deutsche. A strategic investment as Qatar’s deputy prime minister and minister of foreign affairs Sheikh Mohammed bin Abdulrahman Al Thani, also chairman of QIA, has stated that Qatar is interested in further investments in Germany.

Recently, Deutsche reluctantly disclosed a hidden loss of $1.6bn, stemming from municipal bond-investment from a run-up to the 2008 crisis, which does little to strengthen the bank’s position prior to the merger with Commerzbank. – And then there is the latest scandal: Deutsche’s involvement in Danske Bank’s laundering of €230bn through its Estonian branch. In the end, Deutsche might be not only need capital but also moral vision, which might not necessarily come with Qatari funds.

Credit Suisse and the Qataris

The Qatari investment in Credit Suisse in 2008 was definitely a turning point for the bank and saved it from needing a state bailout. Though Qatar Holding has lowered its shareholding in the bank, it is still the largest shareholder with 5.21%, followed by Harris Associates, Norges Bank, the Olayan Group, owned by a Saudi family investing in the West since the 1950s and BlackRock.

The investment in Credit Suisse 2008 did not come cheaply for the bank: as in Barclays, the investment was more complicated than just buying shares. It was designed as convertible bonds in Credit Suisse, with a coupon of between 9 and 9.5%. This means that while regular shareholders have seen meagre dividends, Qatar Holding collects CHF380m each year from Credit Suisse.

Until February 2017, an Al Thani of the younger generation, Sheikh Jassim bin Hamad Al Thani, son of Sheikh Mohammed Bin Khalifa Al Thani, was on the board. When the young Sheikh stepped down, apparently without explanation, he was not replaced by another Qatari. His departure did not make much difference on the board except there would be fewer cigarette breaks without him.

At the time, there were speculations that Qatar Holding would be selling its stake in the bank, that Credit Suisse might be cutting the ties to the Qataris and would possibly use the opportunity to replace the convertible bonds with less expensive options as they came callable in 2018.

The bank did indeed do that at first opportunity, October 23 2018. In order to cut funding cost, it bought back around CHF5.9bn of debt issued after the financial crisis to QIA and the Olayan family; Qatar held just over CHF4bn, Olayan Group the rest, both being entitled to 9.5% on the securities.

The Qatar shareholding in Credit Suisse briefly dipped below 5% last year but then rose again to the present 5.21%. Some changes were made to the board in February 2019 but it is as if the Qataris have lost interest in the bank: in spite of being the largest shareholder they have not had a representative on the board since 2917.

Who learns what from whom?

“A sham agreement is one that does not mean what it says,” said Justice Jay to the jury recently at the trial against the four Barclays bankers. “It requires two parties. The counterparty to the [advisory services agreements] was a Qatari entity. The logic of the prosecution case that these defendants were dishonest must be that one or more individuals comprising or connected with the Qatari entity was equally dishonest in the criminal sense. There’s no getting around that.”

There was a sham agreement with Qatari investors at the core of the Icelandic criminal case against the three Kaupthing bankers and the bank’s second largest shareholder parallel to the sham agreement with Qatari investors at the core of the Barclays case.

It is not surprising to hear of corrupt business practices in the Middle East – it is known as a thoroughly corrupt part of the world with fabulously wealthy rulers where neither democracy nor transparency is a priority. As can be seen from the billions of pounds, dollars and euros, paid in fines by systemically important Western banks in less than a decade, partly for criminal activity, these banks do not have the highest of moral standards either.

The belief, perhaps a naïve one, was that when businessmen from corrupt parts of the world would do business with Western banks they would have to adhere to Western standards. Apart from the moral standards in Western banks clearly being shockingly low in too many cases, it seems that bankers at Barclays – and Kaupthing – were ready to meet the Middle Eastern investors at the level set by the investors. The question is how other banks have met the requests for the special treatment Middle Eastern investors seem prone to demand.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Deutsche Bank, Kaupthing and alleged market manipulation

“It’s not unlikely that an international bank wants to avoid being accused of market manipulation,” said Prosecutor Björn Þorvaldsson in Reykjavík District Court on October 11, 2017. The “international bank” was Deutsche Bank and the court case was the so-called CLN case. Deutsche was not charged with anything – the criminal case was against Kaupthing managers, charged with fraudulent lending of €510m into a scheme concocted with Deutsche. However, both Kaupthing administrators and liquidators of two BVI companies saw a way of using alleged market manipulation in these transactions to recover from Deutsche the €510m, Kaupthing had paid to Deutsche. In December 2016, Deutsche eventually concluded that paying €425m was preferable to having to recount the ignominious saga in court. All parties to the agreement are unwilling to divulge further facts but a UK court document throws light on Deutsche’s part in the alleged market manipulation, affecting not only Kaupthing’s CDS spreads but also the bond market. – The question is if this really was the only scheme of alleged market manipulation that Deutsche instigated. Further, the case throws light on how tension between Deutsche’s staff working on the scheme and those responsible for legal and reputational risk was dealt with, potentially explaining the same in other Deutsche schemes.

In January 2009, Kaupthing’s ex-chairman Sigurður Einarsson felt compelled to send a letter to family and friends to counter claims in the Icelandic media regarding Kaupthing’s activities in the months before the bank failed in October 2008. One was that in 2008 the bank had traded on its own credit default swaps, CDS, linked to credit-linked notes, CLN, to bring down the bank’s CDS spreads and thus lower the bank’s cost of financing.

Einarsson wrote that Kaupthing had indeed funded such transactions, via what he called “trusted clients” in cooperation with Deutsche Bank; the underlying assumption was that a reputable international bank would not have done anything questionable – those were the days before international banks like Deutsche were being questioned and fined for criminal actions.

The Icelandic 2010 Special Investigations Committee, SIC, report told the CDS saga in greater detail, documenting Deutsche’s full knowledge from the beginning. A 2012 London court decision added to the story: in order to recover documents related to the transactions, Stephen Akers and Mark McDonald from Grant Thornton London – appointed liquidators of two BVI companies, Chesterfield and Partridge, used in the CDS transactions in the names of the “trusted clients” – had brought Deutsche Bank to court.

The CDS saga was summed up in 2014 charges in a criminal case in Iceland: Einarsson, Kaupthing’s CEO Hreiðar Már Sigurðsson and head of the bank’s Luxembourg operations Magnús Guðmundsson were charged with breach of fiduciary duty, causing a loss of €510m to Kaupthing, some of which Kaupthing paid to Deutsche literally as Kaupthing was failing. – All of this has earlier been reported in detail on Icelog(most notably here, December 2015 and here, November 2017).

The latest addition to the CDS saga is in another court document, consolidated particulars* from 2014, as the liquidators of the two BVI companies sought to recover funds from Deutsche in a civil case by suing Sigurðsson, Einarsson, Venkatesh (or Venky) Vishwanathan the Deutsche senior banker who liaised with Kaupthing on the CLN trades and, most importantly, the liquidators sued Deutsche Bank. The fifth defendant was Jaeger Investors Corp., BVI, a director nominee for Chesterfield and Partridge.

The 2014 document shows, in extensive quotes from emails etc., that contrary to Deutsche’s version in its Annual Reports etc., the bank was fully aware of the fact that Kaupthing set up these trades and funded them in order to influence its CDS spreads, i.e. allegedly the scheme was effectively a market manipulation. In addition, the Icelandic criminal case related to the CLN transactions documented that Deutsche was on the other side of the bet, thereby effectively creating a hedge for itself.

Thus the Icelandic SIC, the Icelandic Special Prosecutor, the Kaupthing administrators and of course the liquidators of the two BVI companies have all come to the same conclusion: Kaupthing and Deutsche colluded in market manipulation.

This goes a long way to explain why Deutsche, by the end of 2016, chose to settle with Kaupthing – Deutsche Bank was not going to be dragged into court to explain the discrepancy between its public statements and internal Deutsche documents, in addition to profiting from being a counterparty in the transactions. The liquidators alleged Deutsche took part in criminal activity. This has however not been tested in court; the SFO had as early as 2010 looked at these transactions but later apparently dropped its investigation as so many others.

One intriguing aspect of the CLN transactions is that Deutsche staff took measures to hide facts from staff working on legal and reputational risk. This has immense ramification for so many other questionable transactions in the bank, which have come to light over the last few years, inter alia Deutsche’s involvement in the largest known case of money laundering of all times: Danske Bank money laundering in Estonia 2007 to 2015, a saga still in the making.

The Deutsche version of the CDS saga (is very short)

Deutsche first mentioned the CLN claims in its 2015 Annual Report (p. 340). As an introduction to the bank’s 2016 Annual Report, Deutsche CEO John Cryan sent out a message to the bank’s employees on February 2 2017 where the settlement with Kaupthing was one of four legal issues the bank had resolved and chose to emphasise.

Deutsche has consistently presented the CDS transactions as if it had only learned of the realities well after the CLN transactions, as here in 2017 (the text is the same in Deutsche’s 2015 and 2016 (p. 369) Annual Reports):

Kaupthing CLN Claims

In June 2012, Kaupthing hf, an Icelandic stock corporation, acting through its winding-up committee, issued Icelandic law claw back claims for approximately € 509 million (plus costs, as well as interest calculated on a damages rate basis and a late payment rate basis) against Deutsche Bank in both Iceland and England. The claims were in relation to leveraged credit linked notes (“CLNs”), referencing Kaupthing, issued by Deutsche Bank to two British Virgin Island special purpose vehicles (“SPVs”) in 2008. The SPVs were ultimately owned by high net worth individuals. Kaupthing claimed to have funded the SPVs and alleged that Deutsche Bank was or should have been aware that Kaupthing itself was economically exposed in the transactions.Kaupthing claimed that the transactions were voidable by Kaupthing on a number of alternative grounds, including the ground that the transactions were improper because one of the alleged purposes of the transactions was to allow Kaupthing to influence the market in its own CDS (credit default swap) spreads and thereby its listed bonds. Additionally, in November 2012, an English law claim (with allegations similar to those featured in the Icelandic law claims) was commenced by Kaupthing against Deutsche Bank in London (together with the Icelandic proceedings, the “Kaupthing Proceedings”). Deutsche Bank filed a defense in the Icelandic proceedings in late February 2013. In February 2014, proceedings in England were stayed pending final determination of the Icelandic proceedings. Additionally, in December 2014, the SPVs and their joint liquidators served Deutsche Bank with substantively similar claims arising out of the CLN transactions against Deutsche Bank and other defendants in England (the “SPV Proceedings”). The SPVs claimed approximately € 509 million (plus costs, as well as interest), although the amount of that interest claim was less than in Iceland. Deutsche Bank has now reached a settlement of the Kaupthing and SPV Proceedings which has been paid in the first quarter of 2017. The settlement amount is already fully reflected in existing litigation reserves and no additional provisions have been taken for this settlement.

As can be seen from the text, the wording is carefully calculated. Inter alia, Deutsche has never in its public statements mentioned when and how it learned of the realities of the scheme, i.e. it was funded by Kaupthing in order to manipulate its CDS spreads.

Deutsche sent Venky Vishwanathan on leave in the spring of 2015 because of his involvement in the Kaupthing scheme. In 2016, Reuters reported that Vishwanathan was suing Deutsche for unfair dismissal. The status of his case is unclear; he has not responded to my queries on LinkedIn.

An overview of the Kaupthing CLN transactions

In February 2008, at the time of the first meeting regarding the CDS spreads with Deutsche bankers, the Kaupthing management was smarting from steadily increasing financing cost; Kaupthing managers insisted the bank was unfairly targeted by hedge funds and were trying to figure out how Kaupthing could erase the image of weakness implied by the CDS spreads. Already at the first meeting with Venky Vishwanathan it was abundantly clear that Kaupthing was seeking to use own funds to influence the CDS spreads; that was the plan from the beginning – the question was just how to structure it in order to influence the CDS spreads most effectively.

The CDS scheme was developed further in the coming months as the pressure on Kaupthing increased: in spring 2008, the CDS spreads stood alarmingly at 900bp. Deutsche advised against Kaupthing’s original idea of its own direct involvement in the transactions. The solution was to find trusted clients of Kaupthing – Kevin Stanford and his wife Karen Millen, Tony Yerolemou and Skúli Þorvaldsson, all large clients of Kaupthing – who would in name own Chesterfield, the BVI company, entirely funded by Kaupthing; the transactions would be done via Chesterfield.

The Chesterfield transactions were done in August 2008. According to the SIC Report (p.26-28; in Icelandic), the CDS spreads changed on 10 August 2008, following the transaction, from 1000bp to 700bp. Though the spread diminished only for some days, it was deemed success, which should be repeated. For the second round, in September, the CLN transactions were done via another BVI company, Partridge, owned by Ólafur Ólafsson, domiciled in Switzerland, still a wealthy businessman, then Kaupthing’s second largest shareholder and a major borrower in Kaupthing. Again, the Partridge transactions were wholly funded by Kaupthing, organised by Deutsche on behalf of Kaupthing.

In total, Kaupthing paid €510m to Deutsche for the Chesterfield and Partridge trades, the last millions transferred to Deutsche from Kaupthing just as the bank teetered; it formally failed 9 October 2008. Emergency funding from the Icelandic Central Bank to Kaupthing of €500m was partly used to pay Deutsche as part of the Partridge transactions although the funding had been issued to safeguard Kaupthing’s UK operations (See the longer version on Icelog.)

Kaupthing accordingly lost the €510m because the two BVI companies had no assets to speak of, which made it clear from the beginning that should the trades go awry, the loans would be non-recoverable; a fact the liquidators noted, as did the Special Prosecutor in Iceland.

Al-Thani and the CLN trades that never happened

A very intriguing part of this story surfaced in the SIC Report (p.26-28): there had been plans for a third round of Kaupthing-funded CLN transactions through Brooks Trading Ltd, owned by a Qatari investor, Sheikh Mohamed Khalifa al Thani. Kaupthing agreed to a loan of €130m to Mink Trading, an al Thani company, in addition to a loan of $50m to Brooks Trading Ltd, another al Thani company, as up-front profit from the trades.

Again, the purpose of the loan to Mink Trading was to invest in CLN linked to Kaupthing’s CDS, again via Deutsche Bank in transactions structured as the Chesterfield and Partridge transactions. But Kaupthing ran out of time; the loan to Brooks Trading was paid out according to the SIC Report, not the loan to Mink Trading; the al Thani CLN transactions never happened.

Sheikh al Thani is a well-known name in Iceland from his role in another Kaupthing criminal case, the so-called al Thani case; although the case is commonly named after the Sheikh he was not charged (the $50m loan to Brooks Trading might have been connected to the real al Thani case, not the CLN transactions, according the the SIC Report). In the al Thani case the three Kaupthing managers, charged in the CLN case, and Ólafur Ólafsson were sentenced to three to 5 ½ years in prison. As in the CLN case, the bankers were charged for fraudulent lending, breach of fiduciary duty and market manipulation; Ólafsson was sentenced for market manipulation.

According to the SIC Report Kaupthing also agreed to lend Ólafsson €50m against profits from the Partridge trade but SIC documents do not show that the loan was issued.

The doggedly diligent liquidators

The liquidators of the two BVI companies, Stephen Akers and Mark McDonald, quickly seem to have sensed a potentially intriguing story behind the CDS transactions and had some impertinent questions for Deutsche Bank. When Deutsche was remarkably unwilling to answer their questions the liquidators took legal action against the bank in order to obtain documents, as seen in this UK court decision in February 2012.

In his affidavit in the 2012 Decision, Akers said: “It is very difficult to see how the transactions made commercial sense for the Companies.” – As the liquidators were to uncover the short answer here is that the transactions did not make sense for the companies, which were only a tool for Kaupthing managers, as Deutsche full well knew.

This can be gauged in detail from the 2014 consolidated particulars. Well documented, it recounts the whole saga behind the CLN transactions, inter alia the following:

Already at the initial meeting in February 2008 it was clear that Kaupthing’s only reason for setting up the schemes was to bring down its CDS spreads and Kaupthing would fund the transactions; Kaupthing was willing to pay Deutsche for reaching this goal and Deutsche agreed to assisting Kaupthing in reaching it, i.e. bringing down its CDS spreads; from Kaupthing, its most senior managers were involved; at Deutsche, senior staff in London worked on the plan (para 56). A larger group were kept informed by emails, amongst them Jan Olsson managing director of Deutsche and CEO of Deutsche in the Nordics.

After a slow start, the urgency increased in summer 2008: on 18 June 2008, Vishwanathan sent an email to the Kaupthing managers proposing a concrete strategy: “Kaupthing should fund the purchase of a CLN referenced to itself. DB, as the vendor of the CLN, would then hedge its exposure under the CLN, by selling Kaupthing CDS in the market, and this would have the desired effect of lowering Kaupthing’s CDS spread.” (para 62.)

A flurry of emails followed, also because Deutsche’s legal department was hard to please (para 68-69). The bank’s Global Reputational Risk Committee was involved. Kaupthing managers understood that Deutsche staff was “bit stressed about this from a ‘reputation’ point of view.” In July, Deutsche invited Hreiðar Már Sigurðsson and his family on a trip to Barcelona, i.e. paid for flights and hotel, where Sigurðsson attended DB’s Global Markets Conference and discussed the CDS scheme (para 75).

The conclusion was that Kaupthing could not be seen to go directly into the market in transactions linked to its own CDS. The solution was to set up a Luxembourg company for the CDS trades, as Sigurðsson explained in an email to Vishwanathan during the conference: Kaupthing’s lawyer would be “setting up the lux company for our trade” (sic), also offering to discuss further “the right structure that you (i.e. Deutsche) would be comfortable with.” (para 79). That same day, Vishwanathan sent an email to a colleague informing him he was working on “putting together a bespoke ETF for some of (Kaupthing’s) close high net worth clients to take a view on (Kaupthing) CDS…” (para 80).

Late July, Kaupthing’s lawyer in Luxembourg presented an overview in an email to Deutsche’s Shaheen Yusuf, including the ownership structure with the names of the four Kaupthing clients who owned Chesterfield. The presentation clearly stated that the funding, €125m, would come from Kaupthing and that the CLN used was part of a wider scheme where Deutsche would offer CDS for sale with a total nominal value of €250m (para 89). – This document included everything regarding the planned transactions, also the funding.

As all of this is documented in email exchanges between Kaupthing managers and Deutsche staff it is clear that when Deutsche claims, inter alia in its 2015 and 2016 Annual Reports it did not know a) that the funding came from Kaupthing – and – b) that the aim of the transactions was to lower Kaupthing’s CDS spread, it goes against documents, which Deutsche had on its system at the time and should still have.

Avoiding a paper trail

Given that Deutsche’s legal department and its Global Reputational Risk Committee had been worried, the overview and its detailed information on funding etc. was unavoidably a strong dosis for Deutsche to stomach. Yusuf called Kaupthing – it’s not clear if she spoke to Hreiðar Már Sigurðsson or Magnús Guðmundsson – but her mission was to ask Kaupthing to withdraw the presentation and replace it with a new one where the fact that Kaupthing was funding the transactions would be omitted. The Kaupthing Luxembourg lawyer quickly followed her instructions, sending another presentation, with the requested changes: Kaupthing was no longer referenced as the lender.

The BVI liquidators point out that there was a phone call and not an email, concluding this was done in order to avoid a paper trail at Deutsche (para 92-93).

When the Chesterfield trades were executed in August 2008, the effect was immediate, just as Deutsche bankers had promised (para 114). In an email to Vishwanathan Hreiðar Már Sigurðsson said it seemed “our Barcelona trip paid of” (sic) – the trip where the plans were finalised (para 115-116).

Indeed, so pleased were the Kaupthing managers that they decided to do another trade of the same kind (in spite of a very short-lasting effect) (para 117). This time, it would be through a company owned by Ólafur Ólafsson, very much a part of the Kaupthing’s inner circle and a close friend of the Kaupthing managers.

“Are u not paid to work for us?”

Due to force majeur, the second CDS transactions hardly registered: Lehman Brothers collapsed on the 15 September 2008, shaking the world’s financial system to its core. Two days later, Kaupthing’s CDS spread had deteriorated further and stood at record 1150bp. As if nothing had happened in the world of finance, Magnús Guðmundsson, clearly less than pleased, wrote in an email to Vishwanathan: “How can the CDS spread be were they are compare to our trade(.) Are u not paid to work for us? (sic)” (para 128).

This exchange clearly shows how Kaupthing saw Deutsche’s role – Deutsche was acting on behalf of Kaupthing, not for the owners of the two BVI companies. Both Kevin Stanford and Tony Yerolemou have stated they had no idea how the BVI companies in their name were used – they had no idea of the funds that flowed through their companies as Kaupthing strove to meet margin calls. – Interestingly, these are not the only examples of Kaupthing using clients’ companies without the owners’ knowledge.

The liquidators conclude that the nature of the transactions of Chesterfield and Partridge were unlawful as “they were intended to, and did, secretly manipulate Kaupthing’s CDS spreads and thereby the market for CDS referenced to Kaupthing, and the market for Kaupthing bonds.” (para 142-148, further 149-176.)

According to the liquidators, Deutsche Bank broke laws on market manipulation and market abuse not only in the UK but also in other countries where financial products, influenced by Deutsche’s unlawful activities, were traded. (para 143-145). This abuse and manipulation did not only affect Kaupthing’s CDS but also Kaupthing’s bonds as the manipulated CDS affected the pricing of Kaupthing bonds.

Further questions regarding the CDS transactions

In addition to market manipulation and being counterpart to trades Deutsche itself set up, the Kaupthing CLN transactions have other interesting aspects to ponder on.

Emails between Deutsche staff show how employees involved in the Kaupthing transactions were allegedly prepared to withhold information on the owners of the BVI companies from Deutsche’s own know-your-customer team. Also, the staff was aware of the reputational risk from being involved in transaction where a bank tried to influence its own CDS spreads.

There is nothing to indicate that this was done because the Deutsche bankers engaging with Kaupthing were less ethical than other colleagues or more prepared to stray away from the straight and narrow road of regulation – rather, that this was a way of working at the bank. It can only be assumed that in a case like this there was no guidance from the echelons of power at Deutsche, relevant to keep in mind given the enormous sums Deutsche has paid out over the years in fines, also in cases with criminal ramifications.

The CLN saga shows the inner workings of Deutsche, relevant to understand how the bank’s internal safeguarding against illegal activities were side-lined when up against the possibility of profit. Relevant for so many other cases of questionable conduct that have surfaced in the last few years. Intriguing to keep in mind regarding the latest Deutsche scandal: it’s role in Danske Bank’s money laundering in Estonia where $230bn were laundered in 2007 to 2015, where Deutsche seems to have handled around $180bn.

Another aspect is how keenly the Kaupthing managers honoured the agreement with Deutsche. Money was tight in August 2008 when the Chesterfield transaction was done. In September, money was quite literally running out and no doubt the three managers had a lot on their mind. Yet, they never lost focus on these transactions with Deutsche, diligently though with great effort meeting margin calls, even making use of the emergency lending from the Icelandic Central Bank. The managers have explained that Kaupthing’s relationship mattered greatly. Yet, given what was going on at the bank, the question still lingering in my mind why these transactions were apparently so profoundly important to the Kaupthing managers.

Deutsche Bank – the bank that paid €14.5bn(!) in fines March 2012-July 2018

Over the last few years, Deutsche Bank has been fighting regulators on all continents. In total, Deutsche paid fines of €14.5bn from March 2012 to July 2018 for criminal activity ranging from Libor fixing to money laundering, according to ZDF. And there might well be more to come as Deutsche is now involved in the largest money laundering saga of all times, Danske Bank’s laundering of $230bn from 2007 to 2015 where Deutsche allegedly handled close to $180bn of the $230bn.

Intriguingly, in June 2010 the SFO was looking at Deutsche’s role in the CDS trades, according to the Guardian. But as with so much of suspicious activities in UK banks around 2008 (and forever!) nothing more was heard of SFO’s investigation.

Deutsche has refuted having known about the realities of the CDS transactions – that Kaupthing was indeed funding the trades and doing it in order to lower its CDS spreads. However, the paper trail within the bank tells a very clear story, according to the liquidators: Deutsche full well knew the realities and thus took part in market manipulation that in the end affected not only the CDS spreads but, much more seriously, the price of Kaupthing’s bonds. The same was clear already from the SIC Reportand from the CLN criminal case in Iceland.

As mentioned earlier on Icelog, the CLN charges (in Icelandic) support and expand the evidence of Deutsche’s role in the CDS trades. The charges show that Deutsche made for example no attempt to be in contact with the Kaupthing clients who at least on paper were the owners of the two companies; Deutsche was solely in touch with Kaupthing. Inter alia, the owners were not averted regarding margin calls; Deutsche sent all claims directly to Kaupthing, apparently knowing full well where the funding was coming from and who was making the necessary decisions.

Another interesting question is who was on the other side of the CDS bets, i.e. who gained in the end when the Kaupthing-funded companies lost so miserably?

According to the Icelandic Prosecutor, the three Kaupthing bankers “claim they took it for granted that the CDS would be sold in the CDS market to independent investors and this is what they thought Deutsche Bank employees had promised. They were however not given any such guarantee. Indeed, Deutsche Bank itself bought a considerable part of the CDS and thus hedged its Kaupthing-related risk. Those charged also emphasised that Deutsche Bank should go into the market when the CDS spread was at its widest. That meant more profit for the CLN buyer Chesterfield (and also Partridge) but those charged did not in any way secure that this profit would benefit Kaupthing hf, which in the end financed the transactions in their entirety.”

Deutsche’s fees for the two CLN transactions amounted to €30m for the total CDS transactions of €510m. In addition, Deutsche will have profited from going into the market buying “a considerable part of the CDS” thus hedging its risk related to Kaupthing.

Effectively, Deutsche was not interested in having the realities of the case tested in court – it did not want to spell out in court its part in the Kaupthing market manipulation and it did not want to spell out it had itself been a counterpart in the trades. After years of legal wrangling, it chose to settle with Kaupthing and agreed to pay back €425m of the €510m Kaupthing paid to Deutsche for these transactions. – Another case of alleged banking fraud buried in the UK.

*Published by Kjarninn Iceland as an attachment to an open letter (in English but the attachments are linked to the Icelandic version) to Hreiðar Már Sigurðsson and Magnús Guðmundsson from the well-known UK retailer, Kevin Stanford. He and his ex-wife Karen Millen were clients of Icelandic banks, also of Kaupthing. – All emphasis above is mine.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Lessons from Iceland: the SIC report and its long lasting effect / 10 years after

The Bill passed by the Icelandic parliament in December 2008 on setting up an independent investigative commission, the Special Investigative Commission did not catch much attention at the time. The goal was nothing less than finding out the truth in order to establish events leading up to the 2008 banking collapse, analyse causes and drawing some lessons. The SIC report was an exemplary work and immensely important at the time to establish a narrative of the crisis. But in hindsight, there is yet another lesson to be learnt: its importance does not diminish with time as it helps to counteract special interests seeking to rewrite history.

There were no big headlines when on 12 December 2008 Alþingi, the Icelandic parliament, passed a Bill to set up an investigative commission “to investigate and analyse the processes leading to the collapse of the three main banks in Iceland,”which had shaken the island two months earlier. The palpable lack of enthusiasm and attention was understandable: the nation was still stunned and there was no tradition in Iceland for such commissions. No one knew what to expect, the safest bet was to not expect very much.

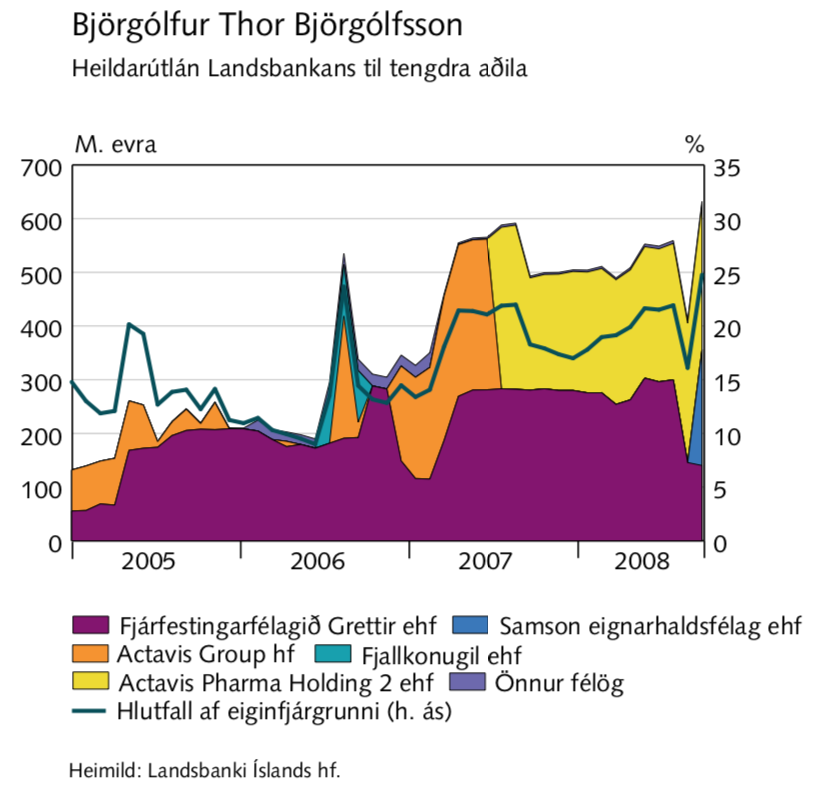

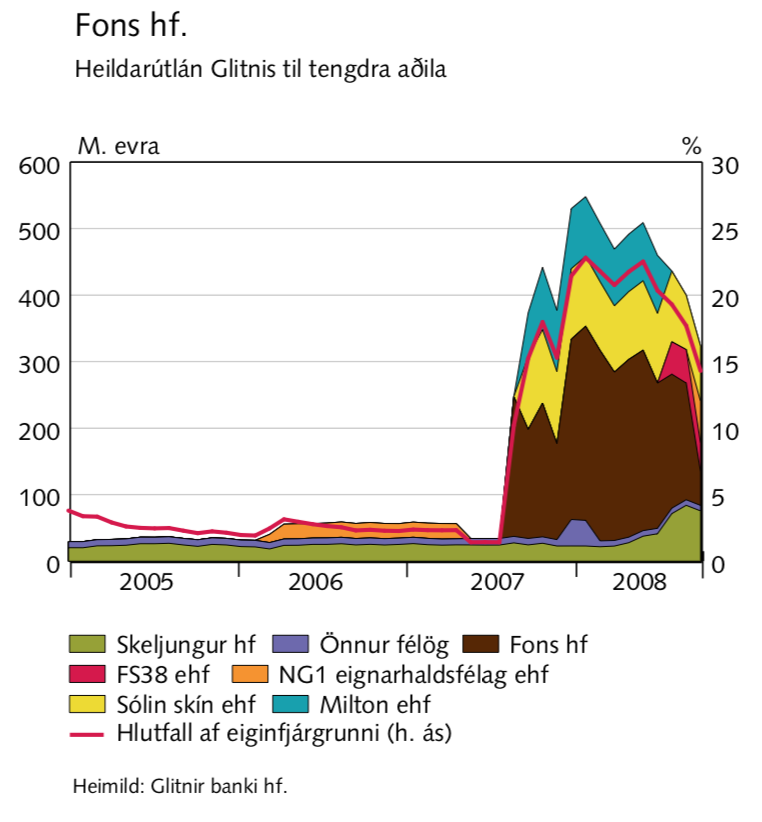

That all changed when the Commission presented its results in April 2010. Not only was the report long – 2600 pages in print in addition to online-only material – but it did actually tell the real story behind the collapse: the immensely rapid growth of the banks, from one GDP in 2002 to ten times the GDP in 2008, the stronghold the largest shareholders, incidentally also the largest borrowers, had on the banks’ managements, the political apathy and lax regulation by weak regulators, stemming from awe of the financial sector.

Unfortunately, the SIC report was not translated in full into English; see executive summary and some excerpts here.

With time, the report’s importance has not diminished: at the time, it clarified what had happened thus preventing those involved or others with special interest, to reshape the past according to their own interests. With time, hindering the reshaping of the past has become of major importance, also in order to draw the right lessons from the calamitous events in October 2008.

What was the SIC?

According to the December 2008 SIC Act (in Icelandic), the goal was setting up an investigative commission, that would, at the behest of Alþingi, seek “the truth about the run-up to and the causes of the collapse of the Icelandic banks in 2008 and related events. [The SIC] is to evaluate if this was caused by mistake or neglect in carrying out law and regulation of the financial sector in Iceland and its supervision and who could be held responsible for it.” – In order to fulfil its goal the SIC was inter alia to collect information on the financial sector, assess regulation or lack thereof and come up with proposals to prevent the repetition of these events.

In some countries, most notably in South Africa after apartheid, “Truth Commissions,” have played a major part in reconciliation with the past. Although the remit of the Icelandic SIC was to establish the truth, the SIC was never referred to as a “truth commission” in Iceland though that concept has been used in foreign coverage of the SIC.

The SIC had the power to make use of a vast array of sources, both by calling in people to be questioned and documents, public or private such as bank data, including data on named individuals, data from public institutions, personal documents and memos. Data, normally confidential, had to be shared with the SIC, which was obliged to operate as any other public body handling sensitive or confidential information.

Although the SIC had to follow normal procedures of discretion on personal data the SIC could “publish information, normally subject to discretion, if the SIC deems this necessary to support its conclusions. The Commission can only publish information on personal matters of named individuals, including their financial affairs, if the public interest is greater than the interest of the individuals concerned.” – In effect, this clause lift banking secrecy.

One source close to the process of setting up the SIC surmised the political intentions behind the SIC Act did not include lifting banking secrecy, indicating that the extensive powers given to the SIC were accidental. Others have claimed the SIC’s extensive powers were always part of the plan. I am in two minds about this but my feeling is that the source close to the process was right – the powers to scrutinise the main shareholders were far greater than intended to begin with.

Naming the largest borrowers, incidentally also the largest shareholders

Intentional or not, the extensive powers enabled naming the individuals who received the largest loans from the banks, incidentally their largest shareholders and their closest business partners. This was absolutely essential in order to understand how the banks had operated: essentially, as private fiefdoms of the largest shareholders.

In order to encourage those called in for questioning to speak freely, the hearings were held behind closed doors; there were no public hearings. The SIC had extensive powers to call people in for questioning: it could ask for a court order if anyone declined its invitation, with the threat of taking that person to court on grounds of contempt in case the invitation was declined.

Criminal investigation was not part of the SIC remit but its power to call for material or call in people for questioning was parallel to that of a prosecutor. As stated in the report, the SIC was obliged to inform the State Prosecutor if there was suspicion of criminal conduct:

The SIC’s assessment, pursuant to Article 1(1) of Act no. 142/2008, was mainly aimed at the activities of public bodies and those who might be responsible for mistakes or negligence within the meaning of those terms, as defined in the Act. Although the SIC was entrusted with investigating whether weaknesses in the operations of the banks and their policies had played a part in their collapse, the Commission was not expected to address possible criminal conduct of the directors of the banks in their operations.

As to suspicion of civil servants having failed to fulfil their legal duties, the SIC was supposed to inform appropriate instances. The SIC was not obliged to inform the individuals in question. As to ministers, the SIC was to follow law on ministerial responsibility.

The three members

The SIC Act stipulated it should have three members: the Alþingi Ombudsman, then as now Tryggvi Gunnarsson, an economist and, as a chairman, a Supreme Court Justice. The nominated economist was Sigríður Benediktsdóttir, then lecturer at Yale University (director of Financial Stability at CBI 2012 to 2016 when she returned to Yale). The chairman was Páll Hreinsson (since 2011 judge at the EFTA Court).

In addition to the Commission there was a Working Group on Ethics: Vilhjálmur Árnason professor of philosophy, Salvör Nordal director of the Centre for Ethics, both at the University of Iceland and Kristín Ástgeirsdóttir director of the Equal Rights Council in Iceland. Their conclusions were published in Vol. 8 of the SIC report.

In total, the SIC had a staff of around 30 people. As with the Anton Valukas report, published in March 2010, on the collapse of Lehman Brothers, organising the material, especially the data from the banks, was a major task. The SIC had access to the databases of the three collapsed banks but had only limited data from the banks’ foreign operations.