Search Results

European FX loans revisited – the wandering curse

The Polish “Stop BankingInjustice Association” is one of many grass root organisations that have sprouted in many European countries in the last few years, due to FX loans: retail lending to people only with income and assets in their domestic currency. Today, the Polish organisation held a meeting in the Polish Parliament in order to explain the politicians and others the status of FX loans affairs in Poland and elsewhere in Europe, with speakers inter alia from Italy, Spain, Ukraine, Hungary and Iceland. – Interestingly, only in Iceland have the FX loans been dealt with, fairly speedily though never without pain for the borrowers.

The problems of FX loans in Iceland came up fairly quickly after the banking collapse in October 2008. No wonder, the króna had collapsed and everything linked to the currency rates was rapidly rising. To begin with, I was not particularly interested, felt that the borrowers should have been aware of the risk, not much to do. However, after getting an email from a Croatian FX borrower, telling me of the plight of FX borrowers in her country, I started looking at these loans in a wider perspective.

FX loans: a wandering curse for more than 40 years

In short, FX loans have been a wandering curse, going from one country to another, for over forty years. There is abundant evidence that FX loans are utterly unsuited as a standard financial product for ordinary people with no income in FX and no buffer.

I have earlier pointed out this wandering curse element of FX loans, how they have wandered from country to country – Australia in 1980s, New Zealand in the 1990s, also in Austria, Germany, Italy and then after 2000 in Iceland and many countries of Central and Eastern Europe – is quite remarkable and also the fact that the pattern is always the same: it ends in tears. This is not a case of this time it’s different; indeed, it’s always the same.

Lessons learnt long time ago, yet banks keep offering FX loans

This statement from the Australian FX loan saga, captures the risk perfectly: “…nobody in their right mind, if they had done a proper analysis of what could happen, would have gone ahead with it (i.e. FX loans).” And in 2013 the Austrian National Bank warned: “Foreign currency loans to private consumers are not suitable as a mass product…” This was the lesson that the Austrian Finance Market Authority, FMA had already drawn in 2008 but only in 2013 did it state this so clearly and unequivocally.

The FX lending pattern is always the same: the banks have the need to hedge themselves, for various reasons (usually because their financing is in some way FX linked) so they offer retail FX loans. Because the interest rates are lower than the domestic rates people can borrow more, thus in a certain sense creating sub prime lending, from the point of view of the capacity to service loans in the domestic currency.

FX loans, sub prime aspects and the unavoidable shock

Given that the loans normally stretch over years and even decades and FX fluctuations happen quite frequently, it’s clear that the circumstances at the time when the loan is issued are unlikely to stay unchanged. It can be argued that borrowers with FX assets or available funds can profit from FX loans over the lifetime of the loan. That however is not the situation for the majority of FX borrowers who at the outset borrow what they at most can service.

In all countries, where FX retail loans have become widespread, the pattern has always been the same: first, the borrowers are castigated for taking loans they then can’t service. Then, the sub prime lending aspects appear: banks haven’t really informed the clients properly, minimised the risks etc and haven’t done the due diligence as to what would happen to these clients should the currency rates change. The question how far authorities should go in protecting people is certainly justified but all European countries do indeed have a strong focus on consumer rights and scrutinising the banks’ information and behaviour with regard to FX loans should be obvious.

The ruling of the Árpad Kásler case, in the European Court of Justice, ECJ, ECJ C?26/13 in 2014 turned the tables against the banks and in the favour of borrowers. Slowly slowly, the sub prime aspect, the insufficient information and the fact that these loans are normally not really FX loans but FX indexed loans has also mattered.

Iceland and elsewhere: FX indexed loans illegal, not FX loans per se

Iceland is the only country in the recent FX loan saga where the loans have sytematically been written down. In that sense, the Icelandic FX loan saga is success from the point of view of hard-hit borrowers. But it didn’t happen over night, it took time: the króna collapsed in 2008 and kept falling until late 2009. The two first Supreme Court rulings, testing the validity of the loans came in summer of 2010. Only by the end of 2014 and after ca. 30 Supreme Court rulings had the loans been recalculated.

The Supreme Court ruled that FX loans are not illegal but the FX lending isn’t really a FX lending but lending in domestic currency where another currency or a combination of more than one currency set the interest rate.

At the conference there were FX loan stories from different European countries, reflecting the state of affairs in the respective countries. In general it can be said that courts, taking note of the Kásler ECJ case, have at times ruled in favour of borrowers but it differs how willing courts are to take note of the precedence.

In Italy, FX loans cases have been in the courts for five years but have yet to reach a verdict in the lowest court. In Ukraine, there has been a moratorium on enforcing FX loans collaterals since 2014.

All in all, what is generally needed is an acknowledgement of the fact that FX loans all follow a similar pattern, no matter if it’s Australia in the 1980s or Spain in the 21st Century. FX loans are a type of sub prime lending and not a product fit as a general product. Until banks and authorities draw the same conclusion as the Austrian central bank and the Austrian Financial Services Authority in 2013 banks can go on selling these poisonous product and pretend to be surprised when it goes, so predictably, wrong.

FX loans are a great interest of mine, see my earlier blogs on FX loans, inter alia here and here.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

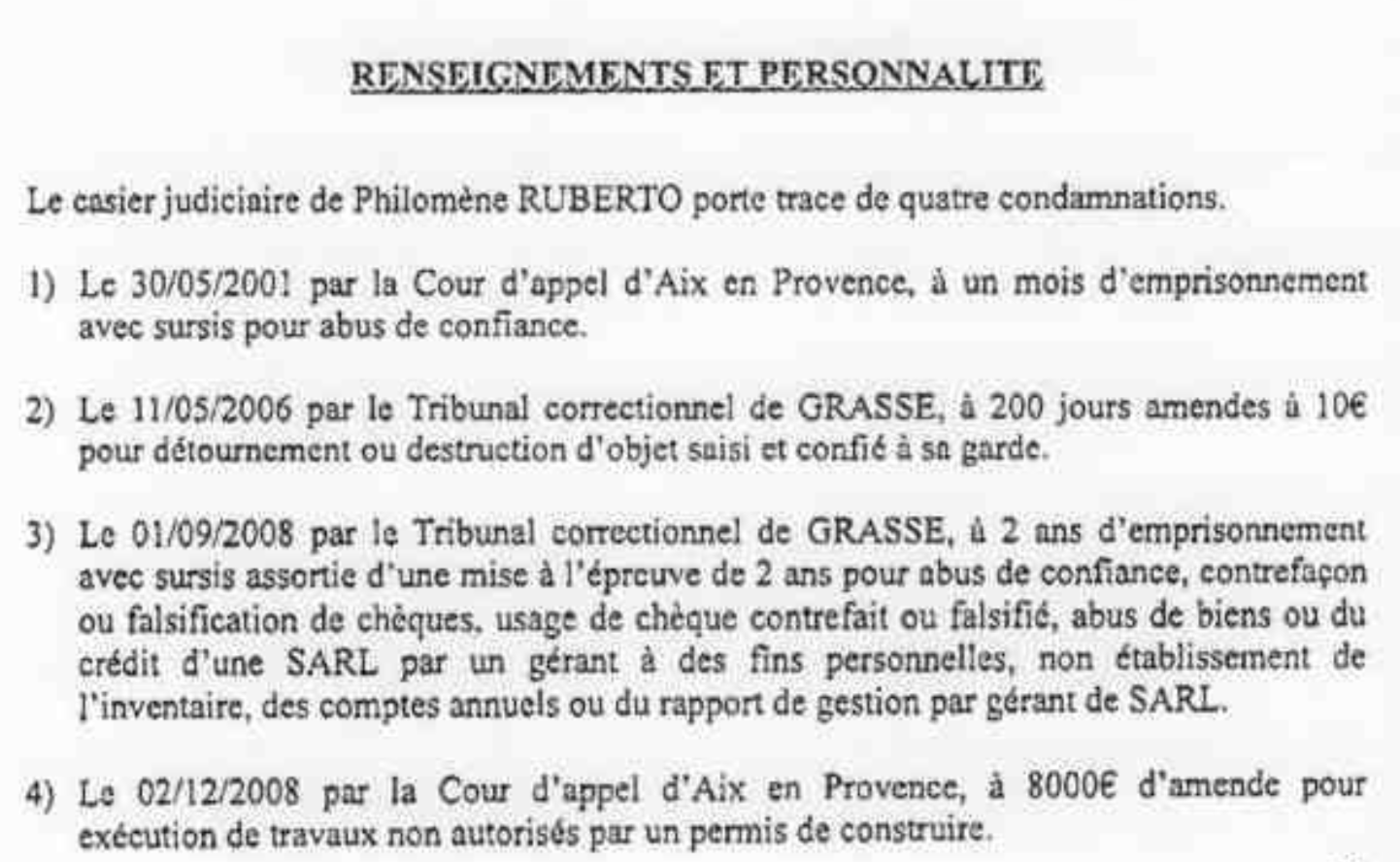

Landsbanki Luxembourg equity release loans – again in Paris Court

In August 2017, French prosecutors lost their criminal case against ex Landsbanki chairman of the board Björgólfur Guðmundsson* and eight former employees of Landsbanki Luxembourg. These nine were charged in relation to the bank’s equity release loans. The prosecution won an appeal and the case is now in court again at Palais de Justice, expected to run into June.

Over the last few decades, equity release loans have wrecked havoc for borrowers in many countries. Like FX loans (see Icelog here), they have been a wandering financial curse. When circumstances change, bankers claim they could not have known – a hollow claim given the history of these loans.

The Landsbanki equity release lending saga has now been running for over a decade, closely followed on Icelog for the last few years (an overview here; link to earlier coverage here). This is a saga in three chapters:

1 The Landsbanki Luxembourg lending – how the loans were sold (an interesting aspect, given that banks all over Europe have lost FX lending cases due to EU consumer directives); the (unrealistically high?) evaluation of the properties used as collaterals; was there ever a viable plan in place in the bank to properly invest that part of the loan that was suppose to pay for the payout part; how credible and trustworthy was the bank’s information to customers? Given that Landsbanki was in dire straits when it started selling these loans it is also of interest what the bank’s purpose was with the loans: just another financial product or a product to save the bank? – This chapter is part of the criminal case in Paris.

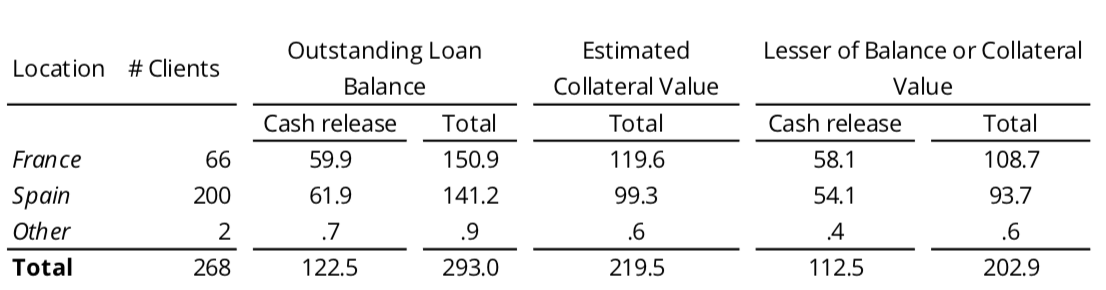

2 The administration of Landsbanki Luxembourg has raised many and serious questions that Luxembourg authorities have so far been utterly unwilling to consider. The administrator, Yvette Hamilius, accuses the borrowers of simply trying to avoid paying. In 2012, the Luxembourg prosecutor Robert Biever issued a statement in her favour, without ever having investigated the case; an interesting if scary example of how the justice operates in the Duchy that depends on banking for its good life. – However, as earlier recounted on Icelog, the borrowers have a very different story to tell, of misleading and conflicting information on their loans and then an unwillingness on behalf of the administrator to engage with them and answer their questions. – Interestingly, Landsbanki Luxembourg has recently been losing in civil cases in Spain where equity release borrowers have brought the estate to court, mainly on the ground of consumer protection (see ERVA for various moves in Spain).

3 The sole creditor to Landsbanki Luxembourg is LBI., the estate of the failed Landsbanki Iceland. LBI has no direct control over Landsbanki Luxembourg but as seen from its webpage, it follows the case closely. The assets in Luxembourg are now the only assets left for LBI to distribute to its creditors. The question is if the administrator’s hard line against the borrowers, with the accruing legal cost and the clock ticking in eternity, really is in the interest of Landsbanki Luxembourg’s sole creditor.

This time there is a formidable presence on the borrowers’ legal team. Originally Norwegian, Eva Joly studied law in France. She was appointed an investigative judge in the early 1990s, famous for taking on the great and the not so good in major corruption case, where dozens of people, who never expected to see the inside of a prison cell, ended up just there. Joly, an MEP since 2006, cooperates with her daughter, Caroline, also a lawyer.

It remains to be seen how things progress this time in the Paris court room at the grandiose Palais de Justice.

*Together with his son Thor Björgólfsson, Björgólfur Guðmundsson was the largest shareholder of Landsbanki; father and son owned just over 40% of the bank but in reality, controlled over 50% of the bank since ca. 10% of the bank’s shares were in several offshore companies, controlled by the bank itself. This is one the many things exposed by the 2010 report by the Icelandic Special Investigative Commission. Guðmundsson was declared bankrupt following the banking collapse, his son is still one of the wealthiest people on this planet.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Landsbanki Luxembourg managers charged in France for equity release loans

After a French investigation, Landsbanki Luxembourg managers and Björgólfur Guðmundsson, who together with his son Thor Björgólfsson was the bank’s largest shareholder, are being charged in relation to the bank’s equity release loans. These charges would never have been made except for the diligence of a group of borrowers. Intriguingly, authorities in Luxembourg have never acknowledged there was anything wrong with the bank’s Luxembourg operations, have actively supported the bank’s side and its administrator and shunned borrowers. The question is if the French case will have any impact on the Luxembourg authorities.

In the years up to the Icelandic banking collapse in October 2008, all the Icelandic banks had operations in Luxembourg. Via its Luxembourg subsidiary, Landsbanki entered a lucrative market, selling equity release loans to mostly elderly and retired clients, not in Luxembourg but in France and Spain (I have covered this case for a long time, see links to earlier posts here). Many other banks were doing the same, also out of Luxembourg. The same type of financial products had been offered in i.a. Britain in the 1980s but it all ended in tears and these loans have largely disappeared from the British market after UK rules were tightened.

In a nutshell, this double product, i.e. part loan part investment, was offered to people who were asset rich but cash poor as elderly people and pensioners can be. A loan was offered against a property; typically, 1/4 paid out in cash and the remainder invested with the promise that it would pay for the loan. As so often when a loan is sold with some sort of insurance it does not necessarily work out as promised (see my blog post on Austrian FX loans).

The question is if Landsbanki promised too much, promised a risk-free investment. Also, if it breached the outline of what sort of products it invested in when it invested in Landsbanki and Kaupthing bonds. This relates to what managers at Landsbanki did. In addition, the borrowers allege that the Landsbanki Luxembourg administrator ignored complaints made, mismanaged the investments made on behalf of the borrowers. Consequently, the complaints made by the borrowers refer both to events at Landsbanki, before the bank collapsed and to events after the collapse, i.e. the activities of the administrator.

The authorities in Luxembourg have shown a remarkable lack of interest in this case and certainly the borrowers have been utterly and completely shunned there. The most remarkable and incomprehensible move was when the Luxembourg state prosecutor, no less, Robert Biever Procureur Général d’Etat sided with the administrator as outlined here on Icelog. The prosecutor, without any investigation, doubted the motives of the borrowers, saying outright that they were simply trying to avoid to pay back their debt.

However, a French judge, Renaud van Ruymbeke, took on the case. Earlier, he had passed his findings on to a French prosecutor. He has now formally charged Landsbanki managers, i.a. Gunnar Thoroddsen and Björgólfur Guðmundsson. Guðmundsson is charged as he sat on the bank’s board. He was the bank’s largest shareholder, together with his son Thor Björgólfsson. The son, who runs his investments fund Novator from London, is no part in the Landsbanki Luxembourg case. In total, nine men are charged, in addition to Landsbanki Luxembourg.

According to the French charges, that I have seen, Thoroddsen and Guðmundsson are charged for having promised risk-free business and for being in breach of the following para of the French penal code:

“ARTICLE 313-1

(Ordinance no. 2000-916 of 19 September 2000 Article 3 Official Journal of 22 September 2000 in force 1 January 2002)

Fraudulent obtaining is the act of deceiving a natural or legal person by the use of a false name or a fictitious capacity, by the abuse of a genuine capacity, or by means of unlawful manoeuvres, thereby to lead such a person, to his prejudice or to the prejudice of a third party, to transfer funds, valuables or any property, to provide a service or to consent to an act incurring or discharging an obligation.

Fraudulent obtaining is punished by five years’ imprisonment and a fine of €375,000.

ARTICLE 313-3

Attempt to commit the offences set out under this section of the present code is subject to the same penalties.

The provisions of article 311-12 are applicable to the misdemeanour of fraudulent obtaining.

ARTICLE 313-7

(Act no. 2001-504 of 12 June 2001 Article 21 Official Journal of 13 June 2001)

(Act no. 2003-239 of 18 March 2003 Art. 57 2° Official Journal of 19 March 2003)

Natural persons convicted of any of the offences provided for under articles 313-1, 313-2, 313-6 and 313-6-1 also incur the following additional penalties:

1° forfeiture of civic, civil and family rights, pursuant to the conditions set out under article 131-26;

2° prohibition, pursuant to the conditions set out under article 131-27, to hold public office or to undertake the social or professional activity in the course of which or on the occasion of the performance of which the offence was committed, for a maximum period of five years;

3° closure, for a maximum period of five years, of the business premises or of one or more of the premises of the enterprise used to carry out the criminal behaviour;

4° confiscation of the thing which was used or was intended for use in the commission of the offence or of the thing which is the product of it, with the exception of articles subject to restitution;

5° area banishment pursuant to the conditions set out under article 131-31;

6° prohibition to draw cheques, except those allowing the withdrawal of funds by the drawer from the drawee or certified cheques, for a maximum period of five years;

7° public display or dissemination of the decision in accordance with the conditions set out under article 131-35.

ARTICLE 313-8

(Act no. 2003-239 of 18 March 2003 Art. 57 3° Official Journal of 19 March 2003)

Natural persons convicted of any of the misdemeanours referred to under articles 313-1, 313-2, 313-6 and 313-6-1 also incur disqualification from public tenders for a maximum period of five years.”

As far as I know the scale of this case makes it one of the largest fraud cases in France. As with the FX lending the fact that the alleged fraud was carried out in more than one country by non-domestic banks helps shelter the severity and the large amounts at stake.

Again, I can not stress strongly enough that I find it difficult to understand the stance taken by the Luxembourg authorities. After all, Landsbanki has been under investigation in Iceland, where managers have been charged i.a. for market manipulation. – Without the diligent attention by a group of Landsbanki Luxembourg borrowers this case would never have been brought to court. Sadly, it also shows that consumer protection does not work well at the European level.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Austrian banks and FX lending: tip-toeing authorities and households as carry traders (part 1)

Austria was one of the eleven founding members of the Eurozone in January 1999 but the Austrians never quite put their money where their mouth was: Austria is the only euro country where households flocked to take out foreign currency loans. About three quarters of these loans are coupled with repayment vehicles. Unfortunately, the Austrian authorities have known for more than a decade that the repayment vehicles add risk to the already risky FX loans: the crunch time for domestic foreign currency loans will be in 2019 and later when 80% of these loans mature. – This is the saga of authorities that knew full well of the risks and yet allowed the banks to turn households into carry traders.

Foreign currency loans are “… not suitable as a mass market product” – This was the lesson that the Austrian Finance Market Authority, FMA, had already in 2008 drawn from the extensive foreign currency, FX, lending to Austrian households; only in 2013 did the FMA state it so clearly. Long before these risky loans shot up by 10-15%, following the dramatic Swiss decap from the euro in January 2015, the risks were clear to the authorities.

From 1995, Austrian banks had turned a finance product, intended only for specialised investments, into an everyman mass-market product. Contrary to other founding euro countries, the euro did not dampen the popularity of the FX loans, mostly in Swiss francs, CHF. Austrian banks expanded into the neighbouring emerging markets, offering the same product there. Consequently, Austrian banks have turned households at home and abroad into carry traders.

From the beginning, the FMA and later also the Austrian Central Bank, ÖNB had been warning the fast-growing financial sector, with kind words and kid-gloves, against FX loans to unhedged households. The warnings were ignored: the banks raked in fees, FX lending kept rising until it topped (on unadjusted basis) in 2010, not in 2008 when the FMA claimed it banned FX lending.

FX loans in Austria are declining: in 2008 270.000 households had FX loans, 150.000 in March 2015. In February 2015 the FX loans to households amounted to €26bn, ca 18% of household loans. With maturity period of ten to 25 years serious legacy issues remain.

Further, three quarters of these loans, ca. €19.5bn, are coupled with repayment vehicle, sold as a safety guarantee to pay up the loans at maturity. Ironically, they now risk doing just the opposite: according to FMA the shortfall by the end of 2012 (the latest available figure) stood at €5.3bn. An FMA 2013 regulation to diminish this risk will only be tested when the attached FX loans mature: 80% of them are set to mature in or after 2019.

Added to the double risk of the domestic FX loans and the repayment vehicles are FX loans issued by small and medium-sized Austrian banks in the Central European and South-Eastern European, CESEE (the topic of the next article in this series). All this risk is susceptible to multiple shocks, as the IMF underlined as late as January 2014: “Exchange rate volatility (e.g., CHF) or asset price declines associated to repayment vehicles loans (RPVs) could increase credit risk due to the legacy of banks’ FCLs to Austrian households.”

Consequently, as stated by the ÖNB in April this year, seven years after the 2008 crisis FX loans “continue to constitute a risk for households and for the stability of the Austrian financial system” – a risk well and clear in sight since Austria became one of the founding euro countries in 1999. There are still significant challenges ahead for Austrian Banks. Nonperforming loans are rising – Austrian banks are above the European average, very much due to Austrian banks’ operations in CESEE.

Add to all of this the Hypo Alpe Adria scandals and the Corinthia guarantees and the Austrian hills not alive with the sound of music but groaning with well-founded worries, to a great extent because Austrian authorities did not react on their early fears but allowed banks to continue the risky project of turning households into carry traders – yet another lesson that soft-touch regulation does work well for banks but not for society.

Kid-gloves against a mighty and powerful banking (and insurance) sector

There are over 800 banks in Austria, but the three largest, Erste, Raiffeisen and UniCredit Bank Austria, “account for almost half of total bank assets” according to the IMF, which in 2013 pointed out that the financial system, “dominated by a large banking sector,” faces “significant structural challenges, especially the smaller banks.”

Six Austrian banks, three of which are Raiffeisenbanks in different parts of Austria, were included in the ECB Asset Quality Review in October 2014. As expected, the Österreichische Volksbank, partially nationalised, did not pass but the others did. However, the Austrian banks require an additional loan provisioning of €3bn.

The size of the banking sector as a ratio of GDP has been rising, at 350% by mid 2014. The expansion of small Austrian banks in CESEE, where non-covered non-performing loans in these banks’ operations are high, is a serious worry. As is the sector’s low profitability, seen as a long-term structural risk, as is a domestic market dominated by a few big banks and large CESEE exposures.

Theoretically, unhedged borrowers alone bear the risk of FX loans but in reality the risk can eventually burden the banks if the loans turn into non-performing loans en masse, which make these loans significant in terms of financial stability as the IMF has been warning about for years.

Intriguingly, already in 2013 the IMF pointed out that Austria needed to put in place a special bank resolution scheme and should not await the formal adoption of the EU Directive on bank recovery and resolution. It should also pre-empt the coming EU Deposit Guarantee Scheme Directive and the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) Core Principles for Effective Deposit Insurance Schemes as minimum standards. However, the progress in this direction has been slow.

Austrian FX loans: from a specialised product to everyman mortgage

In the mid 1990s Austrian households cultivated an appetite for FX loans, unknowing that they were indeed turning into carry traders without the necessary sophistication and knowledge. The trend started in the 1980s in Vorarlberg, the Bundesland in Western Austria where many commute for work to neighbouring Switzerland and Liechtenstein.

At the end of the 1980s 5% of household loans in Vorarlberg were in FX, compared to the Austrian average of 0.2%. From 1995 there was a veritable Austrian boom in FX lending, with borrowers preferring the CHF, and to a lesser degree, the Japanese yen, to the Austrian Schilling. This trend only got stronger as the interest rate differential between these currencies and the Schilling widened.

Quite remarkably, the introduction of the euro January 1 1999 did not dampen the surge: the Austrians kept their faith to the currency of their Swiss neighbours. At the end of 1995 FX loans to individuals amounted to 1.5% of total lending; in 2000 this had risen to 20%. The popularity of the FX loans was clear: in December 2000 82% of household loans issued that month were in FX. Even though the CHF appreciated by over 6% in 2000 it did not affect the popularity of the FX loans. The FX selling machine was well-oiled.

Since household debt in Austria was fairly low, Austria being among the lower middle group of countries as to the debt-to-equity ratio, the ÖNB was relatively relaxed about these changes – but not quite: already in its first Financial Stability report, published in 2001, it underlined the risk of FX lending and borrowing.

FX loans issuance to Austrian households continued to increase. In 2004, 12% of households reported a mortgage in FX. The trend topped in 2006, after which the demand fell. By the end of 2007 the FX loans, measured in euro, amounted to €32bn, i.e. almost 30% of the volume of loans issued. Here it is interesting to keep in mind that with the exception of few months annual growth rates of FX loans to households have always exceeded the growth of household loans in the domestic currency, until late 2006.

FX loans in Austria are declining: 2008 270.000 households had FX loans, 150.000 in March 2015 but the size of the problem is by no means trivial: in December 2014 “18.9% of the total volume of loans extended to Austrian households was still denominated in foreign currency;” in February 2015 the FX loans to households amounted to €26bn.

There are also indications that because the FX loans seemed cheaper than the euro loans households tended to borrow more. The ÖBN has pointed out that the growth in household borrowing in 2003 to 2004 “can to a large part be attributed to foreign currency loans.” As I have mentioned earlier, the fact that FX loans seem cheaper than loans in the domestic currency, lends them the characteristics of sub-prime lending, i.e. leads to households borrowing more than sensible, thus yet fuelling the FX risk.

This FX lending boom did not only signify borrowers’ taste for carry trade but also that financial products, earlier only on offer for large-scale investments had now become an everyman product, as was ominously pointed out in the first ÖBN Financial Stability report 2001.

Why did (only) Austrians turn into a nation of carry traders?

Nowhere in Europe were FX loans to households as popular as in Austria, as the ÖBN noted in its first Financial Stability report in 2001. At the introduction of the euro, FX loans had been popular in various European countries. Around 2000 Austria stood out but so did Germany where FX loans were being issued at the same rate as in Austria. But only in Austria did the trend continue.

The question is why Austrian households favoured FX over euro loans.

A study in the December 2008 Financial Stability report sketched a profile of Austrian household borrowers, based on an Austrian 2004 wealth survey of 2556 households. The outcome suggested “that risk-loving, high-income, and married households are more likely to take out a housing loan in a foreign currency than other households. Housing loans as such are, moreover, most likely taken out by high-income households. These findings may partially assuage policy concerns about household default risk on foreign currency housing loans.” – This profile only tells who was most likely to choose FX loans over domestic loans, not why this group in Austria differed from the same social groups in the other euro countries.

As I have explained earlier, FX loans often characterise emerging markets, as in the CESEE, where Austrian banks have indeed promoted them, or in Asia in the 1980s and the 1990s. FX tend to gain ground in newly liberalised markets, as in Australia in the 1980s. Then there is Iceland where the banks, fully privatised in 2003, expanding and borrowing abroad, hedged themselves by issuing FX loans, also to households.

FX loans are often an indication of instability where people try to bypass a fickle domestic currency, the apparition of bad policies and feeble politicians. In addition, there are interest rate margin, which may look tempting, if one ignores the fact that currencies rarely have a stable period of more than a few years, making them risky as an index for mortgages, normally runnig for ten to twenty years or more.

None of this is particularly fitting for Austria or any more fitting for Austria than the other mature European economies.

As always when FX loans turn into a problem, the banks blame the borrowers for demanding these highly risky products. If this were the case it could only happen because banks do not fulfil their duty of care, of fully informing the clients of the risks involved. As an Australian banker summed up the lessons of the Australian FX lending spree in the 1980s: “…nobody in their right mind, if they had done a proper analysis of what could happen, would have gone ahead with it (i.e. FX loans).”

According the ÖNB’s December 2008 Financial Stability report banks did claim there was so much demand for these loans that in order to be competitive they had to issue FX loans. But Peter Kolba from the Austrian Consumers Association, Verein für Konsumentinformation, VKI, disagrees that the demand came from the customers: in an information video he claims the loans were very much peddled by the banks, which reaped high fees from these loans.

It is indeed interesting that from 1995 to 2000 Austrian banks experienced a veritable fee surge of 75%, part of which the ÖNB attributed to the increase in FX lending. For the banks there was an extra sugar coating on the increased FX lending profits: “the interest rate and exchange rate risks are borne largely by the borrowers. However, the risk of default by debtors has increased the risk potential of such operations” – the possibility of a default did of course expose the banks to a growing FX risk.

There is one aspect of the Austrian FX lending, which seems to have greatly underpinned their popularity: the loans were widely sold by agents, paid directly for each loan, thus with no incentive to inform clients faithfully about the risk. In addition, the same agents often sold the repayment vehicles, thus reaping profits twice from the same customer.

As summed up by ÖNB’s spokesman Christian Gutlederer (in an e-mail to me) there were specific Austrian structural weaknesses: “Presumably, the interplay of the role of financial service providers, extensive media coverage and rational herding behaviour would offer the most plausible explanation for the popularity of such products in Austria. Tax incentives provided one additional layer: payments of life insurance premiums (the most important kind of repayment vehicle loans) and, in some cases, interest payments for mortgages can be deducted from the tax base.”

The above caused an Austrian FX loans surge, contrary to other euro countries. In addition, the fact that the authorities were so timid in clamping down on the risky behaviour of the banks is worth keeping in mind: the lesson for policy makers is to act decisively on their fears.

Lessons of domestic FX loans: “not suitable as mass product”

Being so aware of the risk the ÖNB and the FMA, have over the years taken various measures to mitigate the risk stemming from the FX lending, though timidly for the first many years.

Already in 2003 the FMA issued a set of so-called “Minimum Standards” in FX lending to households but this did little to dampen rise in FX loans to Austrian households. In 2006, the FMA and the ÖNB jointly published a brochure for those considering FX loans, warning of the risk involved. At the time, businesses were less inclined to take out FX loans: whether the brochure or something else, there was a decline in FX loans 2006 but only temporary.

Andreas Ittner, ÖBN’s Director of Financial Institutions and Markets worried at the time that “private borrowers in particular are unaware of all of the risks and consequences.” FMA Executive Director Kurt Pribil found it particularly worrying that “people seem to be unaware of the cumulative risks involved and of the implications this might have, especially if you consider the length of the financing.”

Though contradicted by the rise in FX lending to households, the two officials emphasised that restrictions put in place in 2003 were working. There was though a clear unease at the state of affairs: “At the end of the day, any foreign currency loan is nothing more than currency speculation.”

On October 10 2008, during turbulent times on the financial markets, the FMA “strongly recommended” that banks to stop issuing FX loans to households. The FMA has since repeatedly claimed FX loans were “banned” in 2008 but that was not the wording used at the time. Funnily enough there is no press release in the ÖBN web archive from this date related to the October restrictions. In its 2014 Annual Report it talks of the autumn 2008 measures “de facto ban” on issuance of new FX loans to households.

According to the IMF, in 2013, the measures “introduced in late 2008 to better monitor and contain FC liquidity risks, by encouraging banks to diversify FC funding sources across counterparties and instruments, and lengthen FC funding tenors.”– There was no ban, not even a “de facto ban.”

FMA’s 2003 “Minimum Standards” for FX lending were revised in 2010. By then, the FMA and the ÖNB had been warning about the FX loans for a decade or longer. In spite of the “non-ban” 2008 measures, it was only in 2010 that Austrian banks “made a commitment to stop extending foreign currency loans associated with high levels of risk, in line with supervisory guidance provided to this effect (“guiding principles”).” In January 2013 the FMA revised the “Minimum Standards,” also taking into account recommendations by the European Systemic Risk Board, ESRB.

All of these warnings are in tip-toeing and kid-glove central bank and regulator speak: there is no doubt that behind these Delphic utterances there were real concern. All along, Austrian authorities have underlined that these standards were not rules and regulations, more a kind advice to the banks to act more sensibly.

The IMF has over the years voiced concern in a much stronger tone and language than the Austrian authorities. As late as January 2014 the IMF underlined the possibility of multiple shock: “Exchange rate volatility (e.g., CHF) or asset price declines associated to repayment vehicles loans (RPVs) could increase credit risk due to the legacy of banks’ FCLs to Austrian households.”

It was not until 2013, five years after the crisis hit and, counting from 2000 when the FX lending had soared, numerous currency fluctuations later that the FMA finally had a clearly worded lesson for the banks and their household FX borrowers: “foreign currency loans to private consumers are not suitable as a mass product…”

Another dimension of FX lending risks: other shocks accompany exchange volatility

In the FMA’s latest regular FX lending overview, from December 2014 it points out that following initiatives to limit the risk on outstanding FX loans, as well as what it there (as elsewhere) calls ban in 2008 on new loans, the volume of borrowings has been falling: outstanding FX loans to private individuals, as a share of all outstanding loans end of September 20014 is now at 19.1%; 95% of these loans are denominated in CHF, the rest mostly in Japanese yen.

Correctly stated, the FX lending is declining but the devilish nature of FX loans is that the principal is affected by chancing rates of the currency the loans are linked to. The number of loans issued may have been declining – the ÖNB points out FX loans to Austrian borrowers have indeed been declining since autumn 2008 but the real decline in the FX lending has been “offset by the appreciation of the Swiss franc.” As seen from ÖNB data the loans did indeed not top until 2010 (see Table A11).

The ceiling set by the Swiss National Bank, SNB, in late summer 2011 helped stabilise the exchange rate – but this stability ended spectacularly in January this year.

What further adds to the risk of FX lending is that it is easy to envisage a situation where banks and borrowers are not hit only by a single shock wave stemming from currency fluctuations but by other simultaneous shocks, such as a slump in asset prices; again something that the ÖNB has underlined, i.a. as early as in the bank’s Financial Stability report April 2003.

If several private borrowers would become insolvent due to rising exchange rates, “the simultaneous and complete realization of the above-mentioned collateral would considerably dampen the price to be achieved.” Thus, banks with a high percentage of foreign currency loans incur a concentration risk, which would endanger financial stability in the region, if the collaterals needed to be sold. It is an extra risk that the banks with the highest share of FX lending were small and medium-sized regional banks in Western Austria; in some cases up to 50% of total assets were FX loans.

Repayment vehicles = no guarantee but an even greater risk

The fact that the majority of Austrian domestic FX loans comes with a repayment vehicle has often been cited as a safety net for FX borrowers and consequently for the banks. This is however a false safety and both the ÖNB and the FMA, as well as foreign observers such as the IMF have, again for a long time, understood this risk.

In order to gauge the risk it is necessary to understand the structure of the FX loans: almost 80% of the FX loans are balloon loans, i.e. the full principal is repaid on maturity: interest rates, according to the LIBOR of the currency and repriced every three months, are paid monthly. The FX loans can normally be switched to euro (or any other currency) but at a fee; another aspect in favour of the bank is a forced conversion clause, allowing the bank to convert the loan into a euro loan without the borrower’s consent.

The repayment vehicle is usually a life insurance contract or an investment in mutual fund, paid into the scheme in monthly instalments. The majority of those who have taken out the FX loans coupled with repayment vehicle have done so via an agent, clearly an added risk as mentioned above.

Consequently, for borrowers there is a twofold risk attached to FX loans with repayment vehicle: firstly, there is the currency risk related to the loans themselves; second there is the real risk of a shortfall in the repayment vehicle, clearly born out by the volatility in 2008. As pointed out in the ÖNB’s Financial Stability October 2008 report the repayment vehicles “in addition to other risks, are exposed to exchange rate risk.”

The ÖNB had however been aware of the repayment vehicle risk much earlier than 2008. Already in its Financial Stability October 2002 report, the risk was spelled out very clearly: the repayment vehicles “usually do not serve to hedge against exchange rate or interest rate risk; rather, they add risk to the entire borrowing scheme.”

If the repayment vehicle does not perform well enough to cover the principal of the FX loan one may try to switch to other investments but at a cost. “If the performance of these repayment vehicles cannot keep up with the assumptions used in the provider’s model calculations, the borrower, who is already exposed to high exchange rate and interest rate risk, becomes exposed to even greater risk.”

In short: on maturity, there is high risk that the repayment investment will not cover the loan, i.e. the alleged safety net has a hole in it. In the present environment of low interest rates it is a struggle to avoid this gap.

Following a 2011 survey there was already a growing shortfall in sight, according to an FMA statement in March 2012. At the time, FX loans with repayment vehicle amounted to €28.6bn. By the end of 2008 the shortfall had been €4.5bn, or 14% of the loan volume. End of 2011 the shortfall in cover amounted to ca. €5.3bn, at the time 18% of the outstanding loans; the increase between 2011 and 2012 had been €800m, an increase in the shortfall by 22%.

In 2013 the FMA put in place regulation, which obliges the insurance companies to create provisions from their own profits should these repayment vehicles fail. This will however only be tested when the attached FX loans mature: 80% of them are set to mature in or after 2019; a “significant redemption risks to Austrian banks” according to the ÖNB in December 2014.

The ÖNB and the FMA are indeed paying extra attention to the interplay between FX loans and the repayment vehicles: the two authorities are conducting a survey in the first quarter of 2015 to uncover the risks posed by these two risk factors, the FX loans and the repayment vehicles. Somewhat wearily, the ÖNB points out that the two authorities have been warning against these loans for more than ten years. Though reined in and declining FX loans still “continue to constitute a risk for households and for the stability of the Austrian financial system.”

Austrian consumer action in sight

Following the Swiss decap in January the Austrian Consumer Association, VKI, has taken action to inform FX borrowers on their options.

The Austrian FX loan agreements normally have a “stop-loss” clause, seemingly a protection for the borrower to limit sudden losses because of currency appreciation. Sadly, following the Swiss decap in January many FX borrowers have discovered that this clause did not limit their losses. These clauses have been the cause of many queries made at the VKI. The FMA, claiming it can not act on this, has advised borrowers to bring the matter to the attention of the banks, but gave the end of February 2015 as a deadline; a remarkably short time.

VKI is also advising FX borrowers to try to negotiate with the banks regarding coast of converting CHF into euro loans or loss incurred from the FX loans compared to euro loan, arguing that these costs should not be carried by the borrowers alone but shared with the bank.

As elsewhere, the Austrian banks have taken fees for administering the FX loans, typically 1 to 2%, as if they had incurred costs by going into the market to buy CHF in connection to the FX loans. However, as elsewhere, the Austrian loans are CHF indexed, not actual lending in FX. In the Árpad Kásler case the European Court of Justice, ECJ, ruled that this cost was illegal since there were no actual services carried out. Consequently, this might be of help to Austrian FX borrowers; also that part of the ruling, which obliges banks to inform clients properly.

If these actions take off this could mean a considerable hit for the banks. After all, 150.000 households have FX loans of €25bn in total, not a trivial sum.

Given the fact that so many of these loans and the repayment vehicles were sold through agents their responsibility for informing clients has to be tested at some point: it is inconceivable that important intermediaries between banks and their clients bear no responsibility at all for the products they arrange to be sold.

As in other countries, Austrian FX borrowers have already been heading for the courts. So far, the cases are few but have at least in some cases been positive for the borrowers.

The question is whether Austrian politicians will be firmly on the side of the banks or if they will come to the aid of FX borrowers. But there really is good reason for political attention, given that the problem certainly is still lingering. It should also be of political concern that the ÖNB and the FMA chose to treat banks with kid-gloves lightly – though full well knowing that the products being sold to consumers were highly explosive and hugely risky both to the borrowers and the country.

* This is the second article in a series on FX lending in Europe: the unobserved threat to FX unhedged borrowers – and European banks.The next article will be on Austrian banks and FX lending abroad. The series is cross-posted on Fistful of euros.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

This time, no different from earlier: FX risk hidden from borrowers

The Swiss Franc unpegging from the euro 15 January this year brought the risk of foreign currency borrowing for unhedged borrowers yet again to the fore. In Central, Eastern and South-Eastern Europe lending in Swiss Franc and other foreign currency, most notably in euros, has been common since the early 2000s, often amounting to more than half of loans issued to households. The 2008 crisis put some damper on this lending, did not stop it though and in addition legacy issues remain. Now, actions by foreign currency borrowers in various countries are also unveiling a less glorious aspect: mis-selling and breach of European Directives on consumer protection. Senior bankers involved in foreign currency lending invariably claim that banks could not possibly foresee FX fluctuation. Yet, all of this has happened earlier in different parts of the world, most notably in Australia in the 1980s.

“The 2008-09 financial crisis has highlighted the problems associated with currency mismatches in the balance sheets of emerging market borrowers, particularly in Emerging Europe,” economists at the European Bank of Reconstruction and Development, EBRD, Jeromin Zettelmeyer, Piroska Nagy and Stephen Jeffrey wrote in the summer of 2009.*

In the grand scheme of Western and Northern European countries this mismatch was a little-noticed side-effect of the 2008 crisis. But at the EBRD, focused on Central, Eastern, South East European, CESEE, countries, its chief economist Erik Berglöf and his colleagues worried since foreign currency, FX, lending was common in this part of Europe. FX lending per se was not the problem but the fact that these loans were to a great extent issued to unhedged borrowers, i.e. borrowers who have neither assets nor income in FX. This lending was also partly the focus of the Vienna Initiative, launched in January 2009 by the EBRD, European and international organisations and banks to help resolve problems arising from CESEE countries mainly being served by foreign banks.

In Iceland FX lending took off from 2003 following the privatisation of the banks: with the banks growing far beyond the funding capacity of Icelandic depositors, foreign funding poured in to finance the banks’ expansion abroad. Icelandic interest rates were high and the rates of euro, Swiss Franc, CHF and yen attractive. Less so in October 2008 when the banks had collapsed: at the end of October 2007 1 euro stood at ISK85, a year later at ISK150 and by October 2009 at ISK185.

After Icelandic borrowers sued one of the banks, the Supreme Court ruled in a 2010 judgement that FX loans were indeed legal but not FX indexed loans, which most of household loans were. It took further time and several judgements to determine the course of action: household loans were recalculated in ISK at the very favourable foreign interest rates. Court cases are still on-going, now to test FX lending against European directives on consumer-protection.

In all these stories of FX loans turning into a millstone around the neck of borrowers in various European countries senior bankers invariably say the same thing: “we couldn’t possibly foresee the currency fluctuations!” In a narrow sense this is true: it is not easy to foresee when exactly a currency fluctuation will happen. Yet, these fluctuation are frequent; consequently, if a loan has a maturity of more than just a few years it is as sure as the earth revolving around the sun that a fluctuation of ca. 20%, often considerably more, will happen.

Interestingly, many of the banks issuing FX loans in emerging Europe did indeed make provisions for the risk, only not on behalf of their clients. According to economist at the Swiss National Bank, SNB, Pinar Yeşin “banks in Europe have continuously held more foreign-currency-denominated assets than liabilities, indicating their awareness of the exchange-rate-induced credit risk they face.”

Indeed, many of the banks lending to unhedged borrowers took measures to hedge themselves. Understandably so since it has all happened before. Recent stories of FX lending misery in various European countries are nothing but a rerun of what happened in many countries all over the world in earlier decades: i.a., events in Australia in the 1980s are like a blueprint of the European events. In Australia leaked documents unveiled that senior bankers knew full well of the risk to unhedged borrowers but they kept it to themselves.

It can also be argued that given certain conditions FX lending led to systematic lending to CESEE clients borrowing more than they would have coped with in domestic currency making FX lending a type of sub-prime lending. What now seems clear is that cases of mis-selling, unclear fees and insufficient documentation now seem to be emerging, albeit slowly, in European FX lending to unhedged borrowers.

FX lending in CESEE: to what extent and why

A striking snapshot of lending in Emerging Europe is that “local currency finance comes second,” with the exception of the Czech Republic and Poland, as Piroska Nagy pointed out in October 2010, referring to EBRD research. With under-developed financial markets in these countries banking systems there are largely dominated by foreign banks or subsidiaries of foreign banks.

This also means, as Nagy underlined, that there is an urgent need to reduce “systemic risks associated with FX lending to unhedged borrowers” as this would remove key vulnerabilities and “enhance monetary policy effectiveness.”

Although action has been taken in some of the European countries hit by FX lending, “legacy” issues remain, i.e. problems stemming from prolific FX lending in the years up to 2008 and even later. In short, FX lending is still a problem to many households and a threat to European banks, in addition to non-performing loans, i.e. loans in arrears, arising from unhedged FX lending.

The most striking mismatch in terms of banks’ behaviour is evident in the operations of the Austrian banks that have been lending in FX at home in Austria the euro country, but also abroad in the neighbouring CESEE countries. In Austria, FX loans were available to wealthy individuals who mostly hedged their FX balloon loans (i.e. a type of “interest only” loans) with insurance of some sort. Abroad however, “these loans in most cases had not been granted mostly to relatively high income households,” as somewhat euphemistically stated in the Financial Stability report by the Austrian Central Bank, OeNB in 2009.

There is plenty of anecdotal evidence to conclude that during the boom years banks were pushing FX loans to borrowers, rather than the other way around. Thus, it can be concluded that the FX lending in CESEE countries was a form of sub-prime lending, that is people who did not meet the requirements for borrowing in the domestic currency could borrow, or borrow more, in FX. This would then also explain why FX loans to unhedged borrowers did become such a major problem in these countries.

Where these loans have become a political issue FX borrowers have often been met with allegations of greed; that they were trying to gain by gambling on the FX market. In 2010 Martin Brown, economist at the SNB and two other economists published a study on “Foreign Currency Loans – Demand or Supply Driven?” They attempted to answer the question by studying loans to Bulgarian companies 2003-2007. What they discovered was i.a. that for 32% of the FX business loans issued in their sample the companies had indeed asked for local currency loan.

“Our analysis suggests that the bank lends in foreign currency, not only to less risky firms, but also when the firm requests a long-term loan and when the bank itself has more funding in euro. These results imply that foreign currency borrowing in Eastern Europe is not only driven by borrowers who try to benefit from lower interest rates but also by banks hesitant to lend long-term in local currency and eager to match the currency structure of their assets and liabilities.”

In other words, the banks had more funding in euro than in the local currency and consequently, by lending in FX (here, euro), the banks were hedging themselves in addition to distancing themselves from instable domestic conditions. A further support for this theory is FX lending in Iceland, which took off when the banks started to seek funding on international markets. (The effect on banks’ FX funding is not uncontested: further on reasons for FX lending in Europe see EBRD’s “Transition Report” 2010, Ch. 3, esp. Box 3.2.)

The Australian lesson: with clear information “…nobody in their right mind… would have gone ahead with it”

Financial deregulation began in Australia in the early 1970s. Against that background, the Australian dollar was floated in December 1983. In the years up to 1985 banks in Australia had been lending in FX, often to farmers who previously had little recourse to bank credit. However, the Australian dollar started falling in early 1985; from end of 1984 to the lowest point in July 1986 the trade-weighted index depreciated by more then a third. Consequently, the FX loans became too heavy a burden for many of the burrowers, with the usual ensuing misery: bankruptcy, loss of homes, breaking up of marriages and, in the most tragic cases, suicide.

The Australian bankers shrugged their shoulders; it had all been unforeseeable. FX borrowers who tried suing the banks lost miserably in court, unable to prove that bankers had told them the currency fluctuations would never be that severe and if it did the bank would intervene. As one judge put it: “A foreign borrowing is not itself dangerous merely because opportunities for profit, or loss, may exist.” The prevailing understanding in the justice system was that those borrowing in FX had willingly taken on a gamble where some lose, some win.

But gambling turned out to be a mistaken parallel: a gambler knows he is gambling; the FX borrowers did not know they were involved in FX gambling. The borrowers got organised, by 1989 they had formed the Foreign Currency Borrowers Association and assisted in suing the banks. The tide finally turned in favour of the borrowers and against the banks; the courts realised that unlike gamblers the borrowers had been wholly unaware of the risk because the banks had not done their duty in properly informing the FX borrowers of the risk. But by this time FX borrowers had already been suffering pain and misery for four to five years.

What changed the situation were internal documents, two letters, tabled on the first day of a case against one of the banks, Westpac. The letters, provided by a Westpac whistle-blower, John McLennan, showed that when the loan in question was issued in March 1985 the Westpac management was already well aware of the risk but said nothing to clients. Staff dealing with clients was often ignorant of the risks and did not fully understand the products they were welling. When it transpired who had provided the documents Westpac sued McLennan – a classic example of harassment whistle-blowers almost invariably suffer – but later settled with McLennan.

As a former senior manager summed it up in 1991: “Let us face it – nobody in their right mind, if they had done a proper analysis of what could happen, would have gone ahead with it.” (See here for an overview of some Australian court cases regarding FX loans).

FX borrowers of all lands, unify!

“Probably like a lot of other people (.) I felt that the banks knew what they were doing, and you know, that they could be trusted in giving you the right advice,” is how one Westpac borrower summed it up in a 1989 documentary on the Australian FX lending saga.

This misplaced trust in banks delayed action against the banks in Australia in the 1980s and in all similar sagas. However, at some point bank clients realise the banks take their care of duty towards clients lightly but are better at safeguarding own interests. As in Australia, the most effective way is setting up an association to fight the banks in a more targeted cost-efficient way.

This has now happened in many European countries hit by FX loans and devaluation. At a conference in Cyprus in early December, organised by a Cypriot solicitor Katherine Alexander-Theodotou, representatives from fifteen countries gathered to share experience and inform of state of affairs and actions taken in their countries regarding FX loans. This group is now working as an umbrella organization at a European level, has a website and aims i.a. at influencing consumer protection at European level.

Spain is part of the euro zone and yet banks in Spain have been selling FX loans. Patricia Suárez Ramírez is the president of Asuapedefin, a Spanish association of FX borrowers set up in 2009. She says that since the Swiss unpegging in January the number of Asuapedefin members has doubled. “There is an information mismatch between the banks and their clients. Given the full information, nobody in their right mind would invest all their assets in foreign currency and guarantee with their home. Banks have access to forecasts like Bloomberg and knew from early 2007 that the euro would devalue against the Swiss Franc and Japanese Yen.”

As in Australia, the first cases in most of the European countries have in general and for various reasons not been successful: judges have often not been experienced enough in financial matters; as in Australia clients lack evidence; there tends to be a bias favouring the banks and so far, only few cases have reached higher instances of the courts. However, in Europe the tide might be turning in favour of FX borrowers, thanks to an fervent Hungarian FX borrower.

The case of Árpád Kásler and the European Court of Justice

In April 2014 the European Court of Justice, ECJ, ruled on a Hungarian case, referred to it by a Hungarian Court: Árpád Kásler and his wife v OTP Jelzálogbank, ECJ C‑26/13. The Káslers had contested the bank’s charging structure, which they claimed unduly favoured the bank and also claimed the loan contract had not been clear: the contract authorised the bank to calculate the monthly instalment on the basis of the selling rate of the CHF, on which the loan was based, whereas the amount of the loan advanced was determined by the bank on the basis of the buying rate of the CHF.

After winning their case the bank appealed the judgement after which the Hungarian Court requested a preliminary ruling from the ECJ, concerning “the interpretation of Articles 4(2) and 6(1) of Council Directive 93/13/EEC of 5 April 1993 on unfair terms in consumer contracts (OJ 1993 L 95, p. 29, ‘the Directive’ or ‘Directive 93/13’).”

In its judgment the ECJ partly sided with the Káslers. It ruled that the fee structure was unjust: the bank did not, as it claimed, incur any service costs as the loan was indeed only indexed to CHF; the bank did not actually go into the market to buy CHF. The Court also ruled that it was not enough that the contract was “grammatically intelligible to the consumer” but should also be set out in such a way “that consumer is in a position to evaluate… the economic consequences” of the contract for him. Regarding the third question – what should substitute the contract if it was deemed unfair – the ECJ left it to the national court to decide on the substitute.

Following the ECJ judgement in April 2014, the Hungarian Supreme Court ruled in favour of the Káslers: the fee structure had indeed favoured the bank and was not fair, the contract was not clear enough and the loan should be linked to interest rates set by the Hungarian Central Bank. – As in the Australian cases Kásler’s fight had taken years and come at immense personal pain and pecuniary cost.

Hungarian law are not precedent-based, which meant that the effect on other similar loan contracts was not evident. In July 2014 the Hungarian Parliament decided that banks lending in FX should return the fee that the Kásler judgement had deemed unfair.

The European Banking Authority, EBS is the new European regulator. The ECJ ruling in many ways reflects what the EBA has been pointing from the time it was set up in 2011. In its advice in 2013 on good practice for responsible mortgage lending it emphasises “a comprehensive disclosure approach in foreign currency lending, for example using scenarios to illustrate the effect of interest and exchange rate movements.”

Calculated gamble v being blind-folded at the gambling table

“Since the ECJ judgment in the Kásler case, judges in Spain have started to agree with consumers from banks,” says Patricia Suárez Ramírez. So far, anecdotal evidence supports her view that the ECJ judgment in the Kásler case is, albeit slowly, determining the course of other similar cases in other EU countries.

The FX loans were clearly a risk to unhedged borrowers in the countries where these loans were prevalent. If judgements to come will be in favour of borrowers, as in ECJ C‑26/13, the banks clearly face losses: in some cases even considerable losses if the FX loans will have to be recalculated on an extensive scale, as did indeed happen in Iceland.

Voices from the financial sector are already pointing out the unfairness of demands that the banks recalculate FX loans or compensate unhedged FX borrowers. However, it seems clear that banks took a calculated gamble on FX lending to unhedged borrowers. In the best spirit of capitalism, you win some you lose some. The unfairness here does not apply to the banks but to their unhedged clients, who believed in the banks’ duty of care and who, instead of being sold a sound product, were led blind-folded to the gambling table.

*The first draft was written in July 2009; published 2010 as EBRD Working Paper.

This is the first article in a series on FX lending in Europe: the unobserved threat to FX unhedged borrowers – and European banks.The next article will be on Austrian banks, prolific FX lenders both at home and abroad, though with an intriguing difference. The series is cross-posted on Fistful of Euros.

See here an earlier article of mine on FX lending, cross-posted on Fistful of Euros and my own blog, Icelog.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Swiss franc appreciation reveals the sorry saga of FX lending to un-hedged individuals

Back in the 1980s Australians, many of them farmers, were offered low-interest loans, appealing in a high-interest environment. With changes in currency rates the loans in Swiss francs and Japanese yen quickly became much beyond the means of the borrowers to service with ensuing pain and suffering. The same story has since played out in country after country with the obvious lesson reiterated: for people with income only in their domestic currency FX borrowing is too high-risk to be wise. Icelanders felt the FX loans’ pain as the Icelandic króna depreciated 2008 as did many Eastern-European countries. – All these loans, often the result of predatory lending, follow the same pattern and it is no coincidence where they hit. There is now ample case for countries to take action: banks should be forbidden to lend in FX to private individuals with all their income in the domestic currency.

Australia in the 1980s, New Zealand in the 1990s, Iceland and a whole raft of other European countries in the 2000s saw liberalised markets but inflation was high and so were interest rates. By taking an FX loan or even just a loan pegged to FX the high domestic interest rates could be avoided – it seemed too good to be true.

Sadly it was indeed too good to be true: currency fluctuations changed the circumstances and servicing FX loans for those with income in the domestic currency became unsustainable. For loans running over many years this was, statistically seen, almost unavoidable. FX loans have turned into a huge problem in countries such Croatia, Bosnia, Bulgaria, Montenegro, Poland and Ukraine but politicians and banks have ignored the problem. These cases were spelled out at a conference on CHF/FX loans in Cyprus in December. Organised by Katherine Alexander-Theodotou president of the UK Anglo-Hellenic and Cypriot Law Association and various representatives of organisations fighting FX loans, the organisers have recently set up European Legal Committee for Consumer Rights to co-ordinate their work in the various countries marred by FX loans.

The recent shock of the CHF appreciation is now forcing the problem into the foreground in these countries. But more should be done: this problem should be solved once and for all because as long as banks and investors see profits in these loans this sorry saga will continue in new countries.

Australia in the 1980s

In Australia banks started offering customers, many of them farmers, yen and CHF loans in the 1980s. With Australian interest rates at around 10-16% the 7% rates of the yen and the CHF was attractive. When the Australian dollar started depreciating in 1986 the difference in interest rates was by far not enough to compensate for the new ratio between the Aussie dollar and other currencies.

As always, the borrowers first tried to keep on paying, then to negotiate new terms with the banks followed by court cases, mostly based on the banks’ negligence of warning the borrowers of the inherent risk of FX loans. To begin with, the borrowers were fighting on their own, not realising that there were so many others in the same situation.

The banks had the upper hand in court: people should have understood the risk and it was neigh impossible for the borrowers to prove what the bankers had said or not said, promised or not several years earlier. The banks claimed the loans had been issued in good faith and foreseeing the Aussie dollar depreciation had been impossible.

Westpac had been particularly successful in the FX loan market. In 1991 a former Westpac executive, John McLennan, leaked two letters from 1986 showing that the bank was well aware of the risk. What ensued was an investigation, which exposed that not only had Westpac been aware of the risk but a law firm had helped it covering its track. This turned into a classic whistle-blower case: Westpac sued McLennan but later settled.

The letters set the story straight, politicians finally turned against the banks and thus the borrowers got the upper hand and some compensation. But all of this only happened five years after the depreciation, leaving many borrowers bankrupt with all the tragedies such events bring on.

The Australian saga entails the same elements later seen in country after country: banks lend in FX to people who neither have an FX income nor are particularly well-placed to gauge the risk; politicians side with the banks – and only after much struggle and long time are borrowers able to get a write-down or other assistance. But by then, tragedies such as divorce or homes lost have already happened and things can never be the same or compensated.

Iceland: where politicians sided with borrowers

High inflation and consequently high interest rates characterised booming Iceland after the privatisation of the financial system in 2003. Banks were eager to grow by issuing loans and lend funds they borrowed internationally. With credit boom in Iceland savings were insufficient to satisfy the credit demand. Icelandic borrowers were offered so called “currency basket loans”: FX indexed loans usually based on a mixture of currency, usually US$, euro, CHF and yen.

As in Australia, things changed and fairly quickly. From October 2007 to October 2008 the króna had been depreciating drastically: €1 cost ISK85 at the beginning of this period but ISK150 in the end; by October 2009 the €1 stood at ISK185.

Borrowers complained, turned to their banks and some individual solutions were found. However, quickly borrowers were not only turning to the banks but to courts. There were no class actions but individuals sought to court, the cases were well publicised and others in the same situation followed them intently.

Already in June 2010 the first Supreme Court judgment fell regarding two such cases. According to the ruling it was against Icelandic law to tie interest rates on Icelandic loans, loans in Icelandic króna, to foreign currency but perfectly legal to lend in FX.

The result was huge uncertainty: first of all, which loans were legal and which were not, i.e. which loans were real FX loans and which were only FX indexed loans – and if some of these loans were illegal what should the interest rates be?

The banks distinguished between loans to private individuals and to companies where company loans have mostly been regarded as legal FX loans, i.e. the companies did indeed receive FX whereas loans to individuals have all been treated as illegal, i.e. not proper FX loans but only with interest rates tied to FX, no matter the form. The Supreme Court ruled that instead of the FX currency interest rates the lowest CBI rates should be used causing substantial losses to the banks.

The Supreme Court has by now ruled in around thirty FX loans’ cases. There are however still on-going FX loan cases in the courts, some of them related to consumer information such as Directive 87/102/EEC The Consumer Credit Directive, Directive 93/13/EEC The Unfair Terms Directive and Directive 2005/29/EC The Unfair Commercial Practices Directive

The peculiarity of the Icelandic FX loans saga is that from the first borrowers had political support, very much contrary to other countries where FX loans have been common. This is partly due to the fact the Icelandic households have long been highly indebted, which has to a certain degree tilted sympathy towards debtors rather than towards those who are trying to save money.

Croatia, Hungary and Poland

The fight of Croatian FX borrowers have their own organisation, the Franc Association but their fight has been arduous, as covered earlier on Icelog. Already last year, Franc won a case against eight banks, all foreign or foreign-owned subsidiaries: UniCredit – Zagrebačka Banka, Intesa SanPaolo – Privredna Banka Zagreb, Erste & Steiermärkische Bank, Raiffeisenbank Austria, Hypo Alpe-Adria-Bank, OTP Bank, Société Générale – Splitska banka and Sberbenk.

The banks were found to have violated customer protection law by not informing clients properly. Further, the Croatian government has now decided to freeze interest rates for one year while further solutions will be sought, with banks forced to take a write-down on these loans.

In Hungary, where FX loans were among the most widespread in Eastern Europe before the 2008 crash, the government ordered banks last year to fix conversion of euro and CHF loans into Hungarian florints to a rate well below market levels. Following the recent CHF deprivation the government has said that no further action will be taken.

Polish FX loans have not been issued since the financial crisis of 2008 but the number of loans before that had been high, which means that many are still suffering their effect. Last year, governor of the Polish Central Bank Marek Belka said these loans were a ticking time-bomb. It certainly has blown up now with the CHF appreciation. The Polish government is now seeking a solution and regulators are investigating collusion on lending terms among the banks issuing the FX loans.

The underlying mechanism of FX loans

Although FX loan sagas vary in details from country to country the general mechanism is everywhere the same, always with four actors involved: international financial institutions looking for interest margins; investors, often called “Belgian dentists,” i.e. wealthy individuals looking for moderate-risk long-term investments; domestic financial institutions (often foreign subsidiaries) selling domestic currency, looking to lend in FX; domestic borrowers looking for low-interest loans.

The FX loans are normally marketed to middle or low-income earners in small or transition economies, recently been liberalised, with unstable currency or where the currency lacks credibility – and/or where interest rates are high. The banks issuing the loans are often, but not always, foreign banks, operating in a weak legal environment with weak or no customer protection.

There are certainly FX loans in other countries, such as the UK but there they have mostly been issued to wealthy borrowers often financing property deals abroad. The situation can certainly be painful for those individuals but these loans are anomalous, hitting only a very limited part of borrowers. In France, many local councils are struggling with CHF loans and fighting financial institutions in court, again clearly a major problem for the councils but now following the general pattern of FX loans listed above.

The general description above fits Australia, New Zealand, Iceland – and the countries where many borrowers have been sorely struggling with FX/CHF loans since 2008, i.a. Poland, Croatia, Hungary and other countries. With the exception of Iceland these countries have been fighting the banks for years, often with limited or only very late success. Only the recent CHF appreciation has finally managed to clearly demonstrate the calamity these loans are for normal borrowers with income only in their domestic currency.

The only sensible solution to FX (predatory) lending

For more than thirty years FX loans have periodically been causing huge harm and personal tragedy in country after country. The pattern is always the same. Banks continue this type of lending, every time minimising or ignoring the risk to unenlightened borrowers. The only new elements are a new country and new people to suffer the consequences.

Since this story has been repeating itself for decades, bankers issuing these loans cannot reasonably claim to be unaware of the risk. Instead, FX lending to private individuals with no FX hedge increasingly looks like predatory lending: the banks must have been aware of the risk and known that the risk had indeed materialised earlier in other countries.

Bankers have so far shown little aptitude of learning anything at all from the past few decades. National and international organisations working in the field of financial regulation and consumer protection should work towards making FX lending to private individuals with no FX hedge illegal. Until that happens the FX loans will continue to find new countries to wreck havoc in.

*Another side to the FX lending is whether the banks issuing the loans have properly hedged their FX exposure of their liabilities. There is indication that banks in i.a. Austria, Croatia and Hungary have held more CHF assets than liabilities. This is another interesting aspect, which I hope to cover later.

If any Icelog reader has documents showing that banks were aware of the risk of FX borrowing to clients but did wilfully not inform them I would be interested in hearing from them.

Update 15.11.22 – obs: some of the links are now out of date.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

The Luxembourg walls that seem to shelter financial fraud

People, mostly pensioners, who previously took out equity release loans with Landsbanki Luxembourg, have for a decade been demanding that Luxembourg authorities look into alleged irregularities, first with the bank’s administration of the loans, then how the liquidator dealt with their loans after Landsbanki failed. The Duchy’s regulator, CSSF, has staunchly refused to consider this case. Yet, following criminal investigations in Iceland into the Icelandic banks, where around thirty people have been found guilty and imprisoned over the years, no investigation has been opened in Luxembourg into the Duchy operations of the Icelandic banks so far. Criminal investigation in France against the Landsbanki chairman at the time and some employees ended in January this year: all were acquitted. Recently, investors in a failed Luxembourg investment fund claimed the CSSF’s only interest is defending the Duchy’s status as a financial centre.

Out of many worrying aspects of the rule of law in Luxembourg that the Landsbanki Luxembourg case has exposed, the most outrageous one is still the intervention in 2012 of the State Prosecutor of Luxembourg, Robert Biever. At the time, a group of the bank’s clients, who had taken out equity release loans with Landsbanki Luxembourg, were taking action against the bank’s liquidator Yvette Hamilius. Then, out of the blue, Biever, who neither at the time nor later, had investigated the case, issued a press release. Siding with Hamilius, Biever stated that a small group of the Landsbanki clients, trying to avoid paying back their loans, were resisting to settle with the bank.

Criminal proceedings in Iceland against managers and shareholders of the Icelandic banks, where around 30 people have been found guilty, show that many of the dirty deals were carried out in Luxembourg. Since prosecutors in Iceland have obtained documents in Luxembourg in these cases, all of this is well known to Luxembourg authorities. Yet, neither the regulator, Commission de Surveillance du Secteur Financier, CSSF, nor other authorities have apparently seen any ground for investigations, with one exception. A case related to Kaupthing has been investigated but, so far, nothing has come out of that investigation (here more on that case, an interesting saga in itself).