Archive for the ‘Iceland’ Category

The CBI loan to Kaupthing October 6, 2008 (updated)

One of the more incomprehensible events in the Icelandic collapse saga is the loan of €500m issued on October 6 2008 by the Central Bank of Iceland to Kaupthing. The burning question is why this loan was issued.

The collateral was the Danish bank, FIH, which CBI became the unhappy owner of after Kaupthing failed. The whole FIH saga is a sorry saga in itself – the CBI sale of FIH has incurred huge losses for the CBI, €180-423m. It’s also unclear how much of the loss stems from the CBI’s bad handling of the sale.

But back to the 500m loan. It indicates that the CBI thought Kaupthing had a greater chance for survival than Glitnir and Landsbanki, which is why the CBI issued the loan. This was a fairly widely held public belief these days. But the CBI should have known better – on Friday October 3, the Bank of England had already taken measures to close down Kaupthing by taking over all deposits coming into the bank from that day. This clearly spelled the end for the bank. Didn’t the CBI know about the UK measures? Or didn’t it care?

By Monday October 6 it was clear that the banks had no chance of survival – the politicians and others had come to terms with the facts over the weekend – and that’s what PM Geir Haarde told the stunned nation in a televised speech at 4pm that Monday. It was also abundantly clear that one big risk factor was the banks’ inter-connectedness.

After the loan came to the light it was for quite a while unclear where the money went. The SIC report from April 2012 indicates that €200m were used to guarantee Kaupthing Sweden, where the Government stepped in for the bank (I actually thought the Swedish Government stepped in, making the Icelandic guarantee superfluous but perhaps I misunderstood something?). The rest? Apparently, it was divided between various other operations, in Luxembourg, Norway and Finland.

But here is another mystery, as far as I can see. Within Kaupthing’s management it was clear that the KSF operation in the UK was a central place in the Kaupthing universe. A failed KSF would cause cross-defaults, leading to the collapse of the Kaupthing Group. As far as I know, Kaupthing got this CBI loan for saving KSF – but none of the money went to the UK.

At the trial over Geir Haarde, the ex-PM was asked what happened to the money. He said it went to a different place than Kaupthing had indicated. Unfortunately, this wasn’t pursued by the prosecutor.

But most terribly regrettably, David Oddsson former Governor of the CBI wasn’t asked at the trial why the CBI issued this loan to Kaupthing, ia if those responsible at the CBI knew that the UK action against Kaupthing had already started, what Kaupthing’s motivation was for receiving the loan and if the CBI did anything to guarantee that the loan was used for its stated purpose.

This perhaps isn’t a big issue – but it’s one of the few completely murky events of these fateful days in early October 2008. Well, there is of course the offer of a Russian loan.

*In May 2010, Vidskiptabladid (in Icelandic) wrote that on Oct. 6 2008 Kaupthing lent ISK28bn to Lindsor, a BVI company that figured in other Kaupthing transactions. The CBI loan to Kaupthing that day amounted to ca ISK80bn. The Lindsor loan was apparently used to buy bonds from Kaupthing Luxembourg and other securities from Skuli Thorvaldsson and the bank’s key managers.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

The Haarde Trial: some highlights from the first 3 days

Although it’s tempting to think of the trial of ex-PM Geir Haarde as a national katharsis and a truth commission that’s not the case at all. There is one person on trial and that’s Geir Haarde. The witnesses throw their own light on facts and events and it’s of great interest to hear the different versions of events. Even though much of it is already known from the SIC report it’s interesting to hear the different persons recount different things. As is in the nature of the whole exercise, prosecutor Sigridur Fridjonsdottir uses the questioning to fill in and clarify documents, which have been collected.

The charges against Haarde are the following:*

1 A serious omission to fulfil the duties of a prime minister facing a serious danger

2 Omitting to take the initiative to do a comprehensive analysis of the risk faced by the state due to danger of a financial shock

3 Omitting to ensure that the work of a governmental consultative group on financial stability led to results

4 Omitting to guarantee that the size of the Icelandic banking system would be reduced

5 For not following up on moving the Landsbanki UK Icesave accounts into a subsidiary

The five charges against Haarde do steer the questioning but a whole range of issues has been touched upon.

During his day in court, Haarde underlined that by 2008 there was nothing that he as a PM could have done to prevent the collapse of the three banks – Glitnir, Landsbanki and Kaupthing. Any necessary measures would have taken too long – selling assets would for example have been impossible at the time – and he would hardly have had the support of Althing. The main point was also, said Haarde, how far the state should go to save private companies. Ia it transpired from Haarde’s testimony that the FSA was more reluctant to accept Icesave than has been thought earlier.

As is clear from the SIC report Minister of Banking at the time Bjorgvin Sigurdsson (soc.dem.) didn’t seem to have much understanding of what was going on in the banks and his co-ministers seem not to have trusted him. His testimony indicated much the same.

Arnor Sighvatsson was the chief economist at the CBI at the time. He said that already in 2005 – two years after the privatisation of Landsbanki and Bunadarbanki ended – the banks were facing problems and their CDS were rising. In hindsight, Sighvatsson said, already at that time there were some danger signals though only later did it become clear how poor the assets of the banks were and that they were financing the acquisition of their own shares.

Sighvatsson wasn’t aware of Icesave opening in the Nethelands (in May 2008) until later. At this time, said Sighvatsson, there was nothing the CBI could do. The FME should have acted on Icesave at the beginning. Deposits are a standard solution to lack of liquidity – the banks, met with suspicion already in 2005, lacked liquidity and Landsbanki turned to Icesave.

The prosecutor asked if Sighvatsson thought Landsbanki should have been required to put Icesave into a subsidiary. His answer was that since Icesave was set up to solve a liquidity problem and the lack of foreign liquidity putting Icesave in a UK subsidiary wouldn’t have solved the bank’s problem.

Lack of liquidity is like a heart attack, he explained, whereas lack of own capital is like cancer. In the end, a terminally ill cancer patient got a heart attack. People were hoping the liquidity problem would pass – now, said Sighvatsson, it’s clear there was never any of hope of that. If the state had lent to the banks, Iceland’s sovereign debt would be close to Italy’s.

Sighvatsson thinks that from the beginning the Icelandic banks were met with great suspicion abroad. In 2005, he attended at meeting with bankers from Barclays who already then were rattled by the rapid growth of the Icelandic banks and their lack of transparency. At the time, neither he nor Barclays knew of the poor quality of the banks’ assets. This suspicion eventually led to European banks stopping all lending to the Icelandic banks in 2006 but the banks saved themselves by borrowing from US banks.

Interestingly, said Sighvatsson, the banks didn’t seem to worry that their CDS shot up. They didn’t seem to care about the rates they had to pay on their loans.

Would asset sales have solved the problem in 2008? No, Sighvatsson thought that was out of the question. If the banks had sold their best assets they would have been left with only junk. Any buyers would also have conducted due diligence – and that would have thrown light on various things, Sighvatsson said.

No matter what, the banks were doomed and they had much better rating than they deserved – yet another indication of the colossal failure of the rating agencies.

In Iceland, David Oddsson widely seen as one of the main culprits in the collapse of the banks – as a PM in the 90s he led the privatisation of the banking system and shaped the political climate at the time. A climate both favourable to and uncritical of the banks. And he was a Governor of the CBI in the critical time from 2005-2009.

The thrust of his testimony was that he had been very worried for a long time but his views had not been appreciated within the bank. – This is interesting, considering how worried and critical Sighvatsson evidently was. It’s been said that Oddsson was isolated within the CBI, not necessarily because of his views but because he wasn’t an economist and didn’t know how to steer this machine that a central bank is.

He himself underlined that he wasn’t the only governor – there were three – but says that by 2007 his colleagues agreed with him. Anyone used to reading central bank reports, he said, should have seen that the CBI was issuing warnings. Oddsson said that for a long time he didn’t believe the infrastructure of the banks was weak. After all, their accounts were signed by the banks’ managers and the leading auditing firms. There didn’t seem to be any reason to distrust them.

An insight into little Iceland: Oddsson said that after he stepped down as a PM there were fewer meetings between the PM and the CBI governor. There was less formality because Haarde and Oddsson had known each other since they were kids.

Oddsson said that the crisis in 2006 had been a close call – the PM at the time Halldor Asgrimsson had called him one weekend, telling him that the banks would all fail the following Monday. That’s what the CEOs themselves thought, said Oddsson. But the banks did survive in the end. This had taught Oddsson that things might be a lot more precarious than they appeared and move swiftly.

Oddsson said that Ingibjorg Solrun Gisladottir leader of the Social democrats and Minister of Foreign Affairs had suggested the state should lend €30-40bn to the banks. That would have killed the Icelandic state, said Oddsson. – As far as I know, this is news; Gisladottir will be a witness later and must address this point since it won’t do her political legacy much good.

Following the acute 2006 crisis the CBI tightened its liquidity control and posed serious questions to the FME regarding the cross-ownership and cross-lending of the banks. Not until the collapse of Glitnir was it clear how loosely the FME defined “related party,” the banks’ lending beyond legal limits to their biggest shareholders and how the banks were lending each other. Oddsson says he never hid his opinion that the FME was much too weak to put up any fight with the banks.

Oddsson is a known humorist. It caused some laughter when he pointed out that Landsbanki didn’t define the bank’s largest shareholders, the father-and-son duo Bjorgolfur Gudmundsson and Bjorgolfur Thor Bjorgolfsson, as “related parties” – and that he had once asked Gudmundsson’s wife is she didn’t find this embarrassing.

In February 2008 Oddsson had met abroad with foreign bankers and rating agencies, which made him very alarmed over the situation in Iceland. Back home he tried to communicate this anxiety but realises in hindsight that the banks were already beyond salvation and there wasn’t much the Government could have done. Though the banks were complaining that they could only borrowed in ISK it later transpired that by getting loans from the ECB their euro loans were indeed higher than their ISK loans. These were smart men, Oddsson said.

Asked about a letter from Mervy King in spring 2008 where King refused a currency swap but offered some help – Haarde said on Monday that the offer from King was never refused; it just wasn’t reacted on in Iceland – Oddsson said that this offer had just been a bit of “nicety.” The main thing was the refusal of doing a swap.

It seems clear both from Oddsson and Sighvatsson’s testimonies that not even at the beginning of Icesave, in autumn 2006, did Landsbanki have the assets to back up Icesave in a UK subsidiary. Much less was this possible in 2008. Landsbanki complained bitterly over the FSA demands. Oddsson said that Landsbanki Iceland clearly didn’t have assets that would have satisfied the FSA and even if it did, the transfer would have weakened the bank in Iceland.

Jon Th Sigurgeirsson, who became head of the Office of the board of Governors at the CBI in April 2008, said that already in November 2005 it was clear where the Icelandic banks were heading because he heard that foreign banks were ready to short-sell Icelandic bank shares. He also pointed out that it’s incredible how renowned auditors could sign the audit of the banks.

In a few words: The above is just a much digested version but it’s clear that the real problem of the Icelandic banks wasn’t lack of liquidity – they were short of capital. They had massively eroded their own capital by lending to buy shares in themselves. This didn’t start in 2008 as a way to save the banks – this tendency had started earlier. The feeble standing of the Icelandic banks is an indictment over those foreign banks that lent them money, the rating companies and the auditing companies.

It seems that from the beginning Landsbanki didn’t have the assets to back up Icesave in a UK subsidiary. The FSA wasn’t tough enough in dealing with Landsbanki. The Icelandic FME was of the opinion that it couldn’t stop the accounts. It’s absolutely incredible that the Dutch FSA allowed Landsbanki to open Icesave in the Netherlands in May 2008. It can’t hid behind EU rules – certainly, the EU passport rules can’t set a lower limit than the home banks have to follow (I understand that these rules have now been changed).

By 2008 the banks couldn’t be saved – but the question is why they were allowed to become so big, relative to the Icelandic economy, considering how weak they were already in 2006. It’s not unique in a country that the banks are beyond and above the political power but it’s unique that the banks, which had demonstrated their weaknesses early on, were still allowed to grow so wildly.

Oddsson was sure that the Icelandic Deposit Guarantee Scheme didn’t apply to Icesave. Others have been less clear on it – but even though many understood the implication for the Icelandic economy, no one seems to have done anything to clarify how these matters stood.

*Revised from an earlier blog.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

The latest from IMF on Iceland: much achieved but risks ahead

Here is the IMF concluding statement of the IMF mission after the 2012 Article IV Consultation on Iceland. The short version is this:

March 2, 2012

Iceland has achieved much since the crisis and its economy is growing again. Nonetheless, considerable challenges remain. Tackling these will require steady policy implementation, increased coordination, and stronger policy frameworks.

Outlook and Risks

The outlook is for a moderate recovery. Over the medium-term, the drivers of growth will gradually shift away from domestic demand (notably investment) toward external demand (as exports increase). However, there are risks to this outlook, emanating from both external and domestic sources.”

To read more, click here.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

The trial over ex-PM Geir Haard (updated)

Monday March 5 was the first day of trial against Geir Haarde, Iceland’s Prime Minister June 2006 – Februar 2009. Haarde is being tried by a special court, “Landsdómur,” never before convened in the history of Iceland. This court’s only function is to try ministers and is modelled on the Danish legal system.

The trial has been covered by the world media, ia by the BBC, Guardian and Sky.

The five charges brought against Haarde regard alleged omissions in office and are the following:

1 A serious omission to fulfil the duties of a prime minister facing a serious danger

2 He didn’t take the initiative to do a comprehensive analysis of the risk faced by the state due to danger of a financial shock

3 He omitted to ensure that the work of a governmental consultative group on financial stability led to results*

4 For omitting to guarantee that the size of the Icelandic banking system would be reduced

5 For not following up on moving the Landsbanki UK Icesave accounts into a subsidiary**

Regardless whether people think it’s fair to indict only one minister it is already clear after the first two days that the trial will provide an interesting insight into a whole range of issues related to the collapse of the banks. Although the setting and the purpose differ, in Iceland the court hearings are being compared to “a truth commission” since it will give the general public the possibility to hear what politicians, civil servants and bankers have to say on the various issues in question.

Unfortunately, the court has decided against broadcasting the hearings. There are only ca 40 places available in the court hall for the media and the general public to share. The court has been asked to reconsider its decision. The hope is very much that it will change its mind.

On the first day, Haarde was questioned for eight hours. Tuesday, witnesses were called in for questioning. Below is a list of the witnesses published by the court:

Monday March 5:

Geir Haarde

Tuesday March 6:

Bjorgvin Sigurdsson former Minister of Trade

Arnor Sighvatsson former chief economist, CBI

David Oddsson former Governor of the CBI

Wednesday March 7

Ingimundur Fridriksson former Governor of the CBI

Baldur Gudlaugsson former permanent secretary of the Ministry of Finance

Bolli Thor Bollason former permanent secretary of the Prime Minister’s Office

Aslaug Arnadottir former head of department in the Ministry of Trade and chairman of the board of the Deposit Guarantee Fund

Jon Sigurdsson former chairman of the board of the FME and member of the board of the CBI

Jon Th Sigurgeirsson head of the Office for the Board of Governors of the CBI

Thursday March 8:

Jon Thor Sturluson former assistant to the Minister of Trade

Jonas Fr Jonsson former director of FME

Jonina Larusdottir former permanent secretary of the Ministry of Trade

Hreidar Mar Sigurdssonr former CEO, Kaupthing

Gudjon Runarsson director of the Icelandic Financial Services Association

Runar Gudmundsson head of the Insurance Department FME

Thorsteinn Mar Baldvinsson former chairman of the board at Glitnir

Friday March 9:

Sigurdur Sturla Palsson former head of CBI’s International Department

Tryggvi Thor Herbertsson former economic adviser to the Government

Vilhelm Mar Thorsteinsson former head of treasury, Glitnir

Heimir V Haraldsson former member of Glitnir ResCom

Johannes Runar Johannsson former member of Kaupthing ResCom

Larentsinur Kristjansson former chairman of Landsbanki ResCom

Vignir Rafn Gislason certified accountant PWC

Kristjan Andri Stefansson former head of department, Prime Minister’s Office

Sylvia Kristin Olafsdottir former head of contingency planning, CBI

Ossur Skarphedinsson former Minister of Industry

Johanna Sigurdardottir former Minister of Social Affairs

Monday March 12:

Ingibjorg Solrun Gisladottir former Minister of Foreign Affairs

Sigurdur Einarsson former chairmand of the board, Kaupthing

Larus Welding former CEO Glitnir

Stefan Svavarsson chief accountant CBI and member of the board, FME

Halldor Kristjansson former CEO Landsbanki

Sigurjon Arnason former CEO Landsbanki

Bjorgolfur Gudmundsson former chairman of the board, Landsbanki

Tueday March 13:

Tryggvi Palsson former head of financial stability, CBI

Gudmundur Jonsson head of lending, FME

Jon Thorsteinn Oddleifsson former head of treasury, Landsbanki

Sverrir Haukur Gunnlaugsson former Icelandic ambassador, UK

Arni M Mathiesen former Minister of Finance

Sigridur Benediktsdottir member of the SIC

Tryggvi Gunnarsson member of the SIC

Atli Gislason member of Althing

Birgitta Jonsdottir member of Althing

Eyglo Hardardottir member of Althing

Lilja Rafney Magnusdottir member of Althing

Magnus Orri Schram member of Althing

Oddny Gudbjorg Hardardottir member of Althing

Steingrimur Sigfusson member of Althing

As this list show, both Prime Minister Johanna Sigurdardottir and Minister of Economic Affairs Steingrimur Sigfusson will appear before the court. It’s also an intriguing thought that bankers Sigurdur Einarsson, Hreidar Mar Sigurdsson and Larus Welding have already been indicted by the Office of the Special Prosecutor. The two CEOs of Landsbanki have been sued by the bank’s WUB and will most likely, at some point, be indicted by the OSP. The first OSP case ruled on by the High Court was against Baldur Gudlaugsson who recently was sentenced to two years in prison for insider trading.

Last but not least, Bjorgolfur Gudmundsson might have a flash back when he takes place before the court: it was in this same hall that Gudmundsson, together with his son Bjorgolfur Thor Bjorgolfsson and their business partner from St Petersburg Magnus Thorsteinsson, signed the agreement to buy 42% of Landsbanki in January 2003.

*The consultative group was comprised of civil servants from the Prime Minister’s Office, the Ministry of Finance, the Ministry of Business Affairs, the FME and the CBI. It was founded with a written agreement on February 21 2008. Its remit was financial stability and contingency planning. On its purpose and work see the executive summary of the SIC report. – I will be following the trial, unfortunately from abroad, but will try to bring a short digest of interesting testimonies.

**The charges have been updated from an earlier version.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

The presidential puppet master

When president Olafur Ragnar Grimsson gave his New Year speech January 1 Icelanders were waiting in suspense. Was the president running for election the fifth time or was he stepping down? Then came this:

“My conclusion may sound like a paradox; it is, nevertheless, that the situation in Iceland is now such that I can be of greater assistance if my choice of action is subject only to my own will, free of the restraints which the office of the Presidency always imposes on speech and action. Without the duties of a head of state on my shoulders, I shall have more scope to devote energy to cherished goals and causes that have long been dear to me; I shall be able to make a contribution of a different kind towards progress and prosperity, science, research and economic activity. New avenues will open up for me to support the battle against climate change and to promote the use of green energy, to develop collaboration in the circumpolar region and foster our relations with leading nations in 7 other parts of the world, and to expand the opportunities open to our young people and support democracy in our society. Thus, my decision does not mean a farewell, but rather the beginning of another journey, a new phase of service to the ideals that have long guided me; at greater liberty to act and enriched by the experience which service as President brings to every individual chosen by the nation.”

Grimsson clearly thought that Iceland and Icelanders were in a good place and he, as the paternal figure, could safely leave his children on their own. Icelanders nodded, saying that well, this was it – the president was going to leave office. Some were surprised that he was stepping down instead of setting a new record of time in office. Others said that clearly he was going to leave little Iceland to explore his global opportunities in the market for former presidents.

After a few days, people woke up to the thought why the president hadn’t said more clearly that he was leaving. His predecessors had, at this point in their career, declared that they were not running for office again. Clear and unequivocal. Not Ragnarsson. He didn’t say he wasn’t running. Just that he had other things to attend to.

People started debating what he had meant: was he or wasn’t he running again? Why hadn’t he said these words “not running again.” The president was asked what he really meant. He didn’t want to say. He just meant what he had said – but that didn’t really answer the question, which is why it was being asked again.

Some thought it utterly unbearable to see him go. No one else could possibly such a good president. No one else could be the president of Iceland. An ad hoc group led by former ministers Gudni Agustsson (Progressive Party) and Ragnar Arnalds (from a left party no longer existing) set up webpage for people to sign the following petition: “We signees challenge you, Mr Olafur Ragnar Grimsson, to run for office this summer. We trust you better than any other person to protect the interests of the people in this country in the difficult times ahead.”

The first flood wave of signees dried up very quickly. A week ago, Agustsson handed Grimsson 31.000 signatures. “I can’t hide,” Grimsson said, “that such an occasion wasn’t in my mind nor was it part of what I had thought would happen, especially not after my New Year’s speech at the time.” Contrary to earlier presidents, he said, there was an obvious will among the people to keep him – a rather insulting remark towards his predecessors.

Grimsson took a whole week to ponder on his next move but today the suspense ended (his statement, only in Icelandic): in spite of what Grimsson calls his “clear words” in the New Year’s speech he now bows to the will of so many Icelanders and is running again, adding: “It’s my sincere wish that the nation will understand that when there is again a constitutional and governmental stability in the country and our standing among the nations is more clear I will decide to turn to other projects before the end of term, so presidential election might then be held earlier than anticipated.” – The short and concise meaning of this that he is staying until a better offer pops up.

Abroad, he champions himself as a leader who paved the way for the democratic process in Iceland, portraying the Icesave referenda as a “yes” or “no” to bailing out the banks. In Iceland, many remember him being a willing host to bankers and business men, literally their fellow traveller, and an avid messenger of the innate and superior brilliance of Icelandic banking and business acumen.

By his little show, the presidential puppet master has, yet again, shown himself to be a master plotter, this time playing on many strings. By creating the uncertainty of him running or not he has kept other possible candidates at bay. Or discouraged them to step forth. It’s long been clear that he is not in favour of Icelandic membership of the European Union and, having vetoed the Icesave agreement twice, he feels he has saved Icelandic democracy.

Any candidate will have to declare his standing on both issues, which means that, unless he is the only candidate, the election will ia be on Icelandic EU membership and Icesave. This is the clearest evidence of the changes of the presidential office Grimsson has instigated during his presidency: from a formal but non-political office to just the opposite.

In his New Year speech, Grimsson talked about going on a new journey. Right he was. It’s a new journey. But it’s not a journey he’s undertaking by himself. He’s taking the whole of Iceland along. It remains to be seen where this journey leads to – and if there is any credible candidate that can make Icelanders leave Grimsson by the roadside. For the moment, Grimsson is pulling all the strings.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

The hard core Kaupthinking – and Ice-banking

Here is a video, with a voice-over in English based on Icelandic tv reporting on Kaupthing, explaining the bank’s prop trading, how it kept the share price high and allegedly manipulated the market. “Kaupthinking, thinking beyond” was the slogan the bank used in its advertising.

To my mind, the prime example of Kauthinking is found in an email sent by Kaupthing Luxembourg manager Magnus Gudmundsson, now indicted by the Office of the Special Prosecutor, and Armann Thorvaldsson CEO of Kaupthing Singer & Friedlander. In the mail they called themselves “association of loyal CEOs.” Describing the set-up of a certain bonus scheme, they write: “The bank wouldn’t make any margin calls on us and would shoulder any theoretical losses, in case they occurred.” (In Icelandic: ,,Bankinn hefði engin margincall á okkur og myndi taka á sig fræðilegt tap ef að yrði.”

This is the Kaupthinking behind all loans to favoured clients, be they Icelandic or foreign. The question is: What sort of banking was this? In the interest of Kaupthing’s 33.000 shareholders? – To be fair, this kind of lending wasn’t unique to Kaupthing. It was common to the Icelandic financial system before the collapse of the banks (and hopefully no longer). Creating a slogan, this was Ice-banking.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

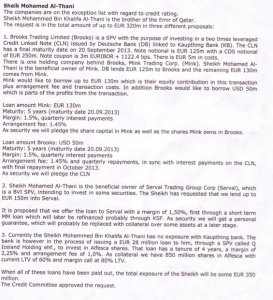

The al Thani story behind the Kaupthing indictment (updated)

The Office of the Special Prosecutor is indicting Kaupthing’s CEO Hreidar Mar Sigurdsson and Kaupthing’s chairman Sigurdur Einarsson for a breach of fiduciary duty and market manipulation in giving loans to companies related to the so-called ‘al Thani’ case; indicting Kaupthing Luxembourg manager Magnus Gudmundsson for his participation in these loans and Kaupthing’s second largest shareholder Olafur Olafsson for his participation. In addition, Olafsson faces charges of money laundering because he accepted loans to his companies without adequate guarantees.

In September 2008 Kaupthing made much fanfare of the fact that Sheikh Mohammed bin Khalifa al Thani, a Qatari investor related to the Qatar ruler al Thani, bought 5.1% of Kaupthing’s shares. The 5.1% stake in the bank made al Thani Kaupthing’s third largest shareholder, after Olafsson who owned 9.88%. This number, 5.1%, was crucial, meaning that the investment had to be flagged – and would certainly be noticed. Einarsson, Sigurdsson and Olafsson all appeared in the Icelandic media, underlining that the Qatari investment showed the bank’s strong position and promising outlook.

What these three didn’t tell was that Kaupthing lent the al Thani the money to buy the stake in Kaupthing – a well known pattern, not only in Kaupthing but in the other Icelandic banks as well. A few months later, stories appeared in the Icelandic media indicating that al Thani wasn’t risking his own money. More was told in SIC report – and now the OSP writ tells quite a story. A story the four indicted and their defenders will certainly try to quash.

The story told in the OSP writ is that on Sept. 19 Sigurdsson organised that a loan of $50m was paid into a Kaupthing account belonging to Brooks Trading, a BVI company owned by another BVI company, Mink Trading where al Thani was the beneficial owner. Sigurdsson bypassed the bank’s credit committee and was, according to the bank’s own rules, not allowed to authorise on his own a loan of this size. The loan to Brooks was without guarantees and collaterals. This loan, first due on Sept. 29 but referred to Oct. 14 and then to Nov. 11 2008, has never been repaid. – Gudmundsson’s role was to negotiate and organise the payment to Brooks. According to the charges he should have been aware that Sigurdsson was going beyond his authority by instigating the loan.

But this was only the beginning. The next step, on Sept. 29, was to organise two loans, each to the amount of ISK12.8bn, in total ISK25.6bn (now €157m) to two BVI companies, both with accounts in Kaupthing: Serval Trading, belonging to al Thani and Gerland Assets, belonging to Olafsson. These two loans were then channelled into the account of a Cyprus company, Choice Stay. Its beneficial owners are Olafsson, al Thani and another al Thani, Sheikh Sultan al Thani, said to be an investment advisor to al Thani the Kaupthing investor. From Choice Stay the money went into another Kaupthing account, held by Q Iceland Finance, owned by Q Iceland Holding where al Thani was the beneficial owner. It was Q Iceland Finance that then bought the Kaupthing shares. As with the Brooks loan, none have been repaid.

These loans were without appropriate guarantees and collaterals – except for Serval, which had al Thani’s personal guarantee. After noon Wed. Oct. 8, when Kaupthing had collapsed, the US dollar loan to Brooks was sent express to Iceland where it was converted into kronur at the rate of ISK256 to the dollar (twice the going rate in Iceland that day) and used to repay Serval’s loan to Kaupthing – in order to free the Sheik from his personal guarantee.

This is the scheme, as I understand it from the OSP writ. And all this was happening as banks were practically not lending. There was a severe draught in the international financial system.

The Brooks loan is interesting. It can be seen as an “insurance” for al Thani that no matter what, he would never lose a penny. When things did go sour – the bank collapsed and all the rest of it – this money was used to unburden him of his personal guarantee. Otherwise, it would have been money in his pocket. It’s also interesting that the loan was paid out to Brooks on Sept. 19, his investment was announced on Sept. 22 – but the trade wasn’t settled until Sept. 29. This means that his “guarantee” was secured before he took the first steps to become a Kaupthing investor.

Apparently, Kaupting’s credit committee was in total oblivion of all this. The CC was presented with another version of reality. Below is an excerpt from the minutes regarding the al Thani loan, discussed when the Board of Kaupthing Credit Committee met in London Sept. 24. 2008 (click on the image to enlarge).

Three things to note here: that the $50m loan “is parts of the profits from the transaction.” Second, that al Thani borrowed €28m to invest in Alfesca. It so happens that Alfesca belonged to Olafsson. Al Thani’s acquisition in Alfesca was indeed announced in early summer of 2008 and should, according to rules, have been settled within three months. At the end of Oct. 2008 it was announced that due to the market upheaval in Iceland al Thani was withdrawing his Alfesca investment. Thirdly, it’s interesting to note that Deutsche bank did lend into this scheme – as it also did into another remarkable Kaupthing scheme where the bank lent money to Olafsson and others for CDS trades, to lower the bank’s spread; yet another untold story.

According to the OSP writ, the covenants of the al Thani loans differed from what the CC was told. It’s also interesting to note that the $50m loan to al Thani’s company was paid out on Sept. 19, five days before the CC meeting. This fact doesn’t seem to have been made clear to the CC.

The OSP writ also makes it clear that any eventual profits from the investment would have gone to Choice Stay, owned by Olafsson and the two al Thanis.

Why did al Thani pop up in September 2008? It seems that he was a friend of Olafsson who has is said to have extensive connection in al Thani’s part of world. Olafsson’s Middle East connection are said to go back to the ‘90s when he had to look abroad to finance some of his Icelandic ventures. London is the place to cultivate Middle East connections and that’s also where Olafsson has been living until recently. It is interesting to note that the Financial Times reports on the indictments without mentioning the name of Sheikh al Thani.

The four indicted Icelanders are all living abroad. Sigurdur Einarsson lives in London and it’s not known what he has been doing since Kaupthing collapsed. Hreidar Mar Sigurdsson lives in Luxembourg where he, together with other former Kaupthing managers, runs a company called Consolium. His wife runs a catering company and a hotel in Iceland.

Magnus Gudmundsson also lives in Luxembourg. David Rowland kept him as a manager after buying Kaupthing Luxembourg, now Banque Havilland, but Rowland fired Gudmundsson after Gudmundsson was imprisoned in Iceland for a few days, related to the OSP investigation. In the Icelandic Public Records it’s said that Olafsson lives in the UK but he has now been living in Lausanne for about two years. In Iceland, he has a low profile but is most noted in horse breeding circles, a popular hobby in Iceland. He breeds horses at his Snaefellsnes farm and owns a number of prize-winning horses.

Following the indictment, Olafsson and Sigurdsson have stated that they haven’t done anything wrong and that the al Thani Kaupthing investment was a genuine deal. The case could come up in the District Course in the coming months. But perhaps this isn’t all: it’s likely that there will be further indictment against these four on other questionable issues related to Kaupthing.

*The OSP indictment, in Icelandic.

**Does it matter that the four indicted are all living abroad? When I made an inquiry at the Ministry of Justice in Iceland some time ago whether Icelanders, living abroad but indicted in Iceland, could seek shelter in any country in Europe by refusing to return to Iceland I was told they couldn’t. If an Icelandic citizen is indicted in Iceland and refuses to return, extradition rules will apply. In this case, Iceland would be seeking to have its own citizens extradited and such a request would be met. – It has been noted in Iceland how many of those seen to be involved in the collapse of the banks now live abroad. It can hardly be because they intend to avoid being brought to court – they would have to go farther. Ia it’s more likely they want to avoid unwanted attention. For those with offshore funds it might be easier to access them outside of Iceland rather than in a country fenced off by capital controls.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

OSP brings charges in the al-Thani case (updated)

The Office of the Special Prosecutor in Iceland has now brought charges in the so-called al-Thani case. In September 2008 Kaupthing announced that a Qatar investor, Mohamed bin Khalifa al-Thani, had bought just over 5% of share in Kaupthing. It later turned out that al-Thani wasn’t risking his own money but Kaupthing’s fund: the bank lent him money to buy the shares. A familiar pattern but this was an important statement because it made the bank seem like a good investment. The interesting thing is that according to documents from Kaupthing Deutsche Bank was involved in the al-Thani investment scheme.

Those charged now are the bank’s CEO Hreidar Mar Sigurdsson, Chairman Sigurdur Einarsson, Kaupthing Luxembourg manager Magnus Gudmundsson and the second largest shareholder in Kaupthing Olafur Olafsson. They are all charged with market manipulation. Sigurdsson and Einarsson are seen as the organisers and are in addition charged with breach of fiduciary duty. Olafsson and Gudmundsson are charged for participation in this breach and Olafsson is in addition charged for money laundering.

The charges are not public yet. Those four now charged are all living abroad. Olafsson has sent out a statement denying the charges. Sigurdsson says he is disappointed and holds on to the official story from September 2008: the sale was genuine and the sheikh did indeed risk his money.

*A blog on the al-Thani case will be coming here soon. Here are earlier blogs referring to the al-Thani case. – The OSP writ can be read here, only in Icelandic.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

A tale of two countries

Tonight, the main news on the Bloomberg‘s webpage is on the new Greek deal. Beneath it there is a Bloomsberg article from earlier today that has shot to the top in the course of the day. If the Greeks read the article on Iceland there would be a massive uprising in Greece because of the new deal: the Icelandic lesson, according to Bloomberg, is that public anger does pay.

Given the circumstances, it’s difficult to imagine what could possibly improve the life of the Greeks – their situation differs from Iceland. But the new EU deal on Greek won’t do wonders for Greece. It will help private sector creditors of Greece, though there is an attempt to force them to write down their debt. Ordinary Greeks will all the same be paying with blood, sweat and tears for years to come in a country where harsh economic measures stifle growth, leaving the Greeks with absolutely no means to grow out of this misery. It remains to be seen how history will judge those Greek politicians who are signing the deal tonight.

The Bloomberg headline on Iceland is “Icelandic Anger Brings Record Debt Relief in Best Crisis Recovery Story.” There are two things of interest here – debt relief and crisis recovery.

As professor Thorolfur Matthiasson explains to Bloomberg, the measures the Icelandic Government has used to help indebted households have worked. “Without the relief, homeowners would have buckled under the weight of their loans after the ratio of debt to incomes surged to 240 percent in 2008, Matthiasson said.” The Government and the banks agreed to forgive debt exceeding 110% of home values. A recent ruling regarding a forex loan indicates a further bonus to those who took out forex loans but the end of that saga, and if it will lead to further debt relief for those who took out indexed loans, is still unclear. The 110% way is, according to professor Matthiasson, “the broadest agreement that’s been undertaken.”

Greeks aren’t fighting forex loans and high private debt but horrific public debt and consequent cuts to the bone. The Icelandic Government did have to make deep cuts but nothing compared to what Greece is facing. Those who want to study the Icelandic recovery find a wealth of information on the IMF website, from a conference held in Iceland last October, as reported earlier on Icelog.

Bloomberg points out that Iceland’s $13 billion economy shrank 6.7% in 2009, but grew 2.9% last year. According to an OECD forecast it will expand 2.4 percent this year and next. In comparison the euro area will grow 0.2% this year. In contrast, Greek GDP has been decreasing for 6-7% a year for the last two years. The forecast for this year, according to the statistics in the new deal, is a decrease of 4.3% – most likely too optimistic – followed by a 0% growth in 2013 and – probably overly optimistic – a growth of 2.3% in 2014.

A significant difference between Icelandic and Greek fortune is that Greece is being forced to fork out money it doesn’t have – but has to borrow – to pay its creditors. Banks with cheap money that didn’t bother to do the math and figure out that Greece should never have been lent all the money it got. For every unwise borrower there is a really dumb lender.

During 2008 the Icelandic Government tried to borrow money abroad to bail out its banks but couldn’t secure the necessary loans. Luckily for Iceland, events in early October 2008 overwhelmed the Government and the IMF – no one could figure out a way to bail out the banks (one Icelog source pointed out that a ECB repo could have been set up but there wasn’t the time). According to my sources, IMF employees present in Iceland as it all happened were furious that the Icelandic Government let the bank collapse but it was all too late and no way to figure out a way when it was all happening.

Instead of the immediate impossibility of saving the banks they were split up: domestic accounts were put into operating domestic banks – and further secured by making domestic deposits a priority claim – whereas the foreign operations were left to go bankrupt, leaving international creditors with whatever can be sold and turned into cash. In addition, the Icelandic Central Banks imposed capital controls to stop a capital flight from the country. This is, in short, the Icelandic way to prevent a banking disaster from turning into a national catastrophe.

This isn’t necessarily a panacea for all sovereigns who hit the rocks – but it’s well worth considering whether saving all banks and let private debt migrate to the public sector, as if it were a natural law to privatise gains and nationalise losses, really is the only way. Iceland couldn’t find any other way at the time (but did indeed later throw good public money at bad private banks; another story mentioned here).

Sadly for the Greeks, it doesn’t seem that any amount of public anger of the Greek demos can diminish this dreadful pain and sad future. Iceland got a quick stab. Today, Greece has been condemned to a lingering pain.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Baldur, the blame game – and the “Flat-Screen Theory of Blame”

The first Surpreme Court ruling in a case of insider trading in Iceland has constituted a clear example: the gain was ISK192m, €1.2m, the sentence is two years imprisonment. There are two fundamentally significant aspects of this case: it’s the first Supreme Court ruling in a case brought by the Office of the Special Prosecutor – and the man found guilty, Baldur Gudlaugsson (b. 1946), is not one of the thirty or so major players in the collapse of the Icelandic banks but a former permanent secretary (a civil servant) at the Ministry of Finance.

Gudlaugsson is a lawyer, intimately connected to the Independence Party, a personal friend of its former leader David Oddsson and as a board member of many companies a prominent person in the Icelandic business community. Interestingly, there was one Supreme Court judge who thought that Gudlaugsson’s guilt was not clear – his name is Olafur Borkur Thorvaldsson, a relative of David Oddsson and his appointment to the Court in 2003 was hotly disputed.

The law Gudlaugsson is seen to have violated is from 2007. The criminal deeds are clearly defined, Gudlaugsson’s sale of shares in Landsbanki in September 2008, shortly before the bank collapsed was, according to the law, illegal. This law has now stood its test.

The ruling will no doubt be a food for thought at the OSP. The state prosecutor lost his last case in the District Court (a case related to Byr and MP Bank). Remains to be seen what the Supreme Court does in the Byr case. The OSP is probably still testing the legal ground before bringing forth further charges.

At the moment, the question of blame is widely debated in Iceland – and the ruling in Gudlaugsson’s case leads to the sarcastic remark, often heard since the District Court ruling, that one civil servant, who made a profit of ISK192m, may be the only person to be sent to prison for criminal acts connected to the collapse of the banks. A scapegoat for the infamous thirty who many Icelanders do blame for these events. – It’s an untimely remark: it’s still far too early to tell what the outcome of the present and coming OPS cases will be.

Apart from Gudlaugsson’s case, the debate on blame falls into two categories: there is what could be called the “Flat-Screen Theory of Blame” – and then the theory, according to which the OSP is working, that alleged crimes are committed by certain individuals. Suspicion of criminal doings should lead to an investigation and, depending on the outcome of the investigation, charges should be brought.

The “Flat-Screen Theory” draws its name from an interview with Bjorgolfur Gudmundsson, who together with his son Bjorgolfur Thor, owned 42% of Landsbanki at the time of its collapse.* In the interview, published a few months after the events of October 2008, Gudmundsson pointed out that Icelanders had lived beyond their means, the number of flat-screens sold in Iceland being a case in point. The core of this theory is that everyone is to blame. Jon Asgeir Johannesson recently aired the same idea – no single person did anything wrong or is to blame; in his version, the collapse seemed like a natural disaster. What happened in Iceland, according to the “Flat-Screen Theory,” was a sort of collective madness that ended in a collective collapse.

This theory has a tail to it, now wagged more and more by various prominent lawyers, who happen to be somehow connected to those seen by many to be to blame. The tail is that the OSP investigations and journalism that seeks to unearth what really happened is “witch-hunt” and “rabble’s court.” This also suggests, implicitly and explicitly, that the attempts to unearth criminal deeds and figure out what really happened is now seen by these lawyers as a much greater threat to the wellbeing and the economy of Iceland than the collapse itself.

In general, the OSP seems to enjoy a high level of trust in Iceland though many find it frustrating how long a time the investigations take. It is however pretty clear who adhere to the “flat-screen theory of blame:” it’s mostly those who were part of, or are now connected to, the political and business elites before the collapse.

Eva Joly (who at the time was much maligned by some of those now propagating the “flat-screen theory of blame”) warned that when those in power feel threatened they use infamy and dirty tricks to further their causes. Gunnar Andersen, the director of the Icelandic Financial Services Authority, the FME, is fighting against being driven out of office. The result of his wrestle with the board, which has just produced a third report into his past at Landsbanki, is still unclear. The FME has, incidentally, sent almost 80 cases to the OSP.

The “Flat-Screen” theorists tend to portray a strikingly selective view of events prior to the collapse. A view that bears little similarity to the findings of the April 2010 report of the Althing Special Investigative Committee. Indeed, in addition to belittling or directly undermining the endeavours of the OSP they also throw doubt on the SIC report or just pretend it doesn’t exist by never referring to it.

It’s fair to say that there is a battle raging in Iceland between the “Flat-Screen” theorists and those who think investigations are necessary in order to show that crime doesn’t pay. That battle is fought over who gets to interpret the past. Those who eventually manage to shape the Icelanders’ understanding of events and circumstances up to October 2008 will come to own the present – and eventually the political and financial future of Iceland.

*Landsbanki WUB claims that father and son – through Landsbanki, Straumur and related parties – controlled 73% of shares in Landsbanki and not only the 42% they held. Bjorgolfsson denies this on his website (only in Icelandic).

The Supreme Court ruling over Gudlaugsson is here (only in Icelandic). – There are two Court levels in Iceland: District Court – and – Supreme Court. I have earlier sometimes used High Court and County Court but it’s the same as DC and SC.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.