Search Results

The Georgiou affair: how Greece keeps failing the political corruption test

After the election in Greece last summer, the country seemed to be on a positive path away from populism towards a more stable political environment. Though born into his party New Democracy, the new prime minister, Kyriakos Mistotakis, brought with him the air of the outside world: he had been a banker and consultant in London, before entering Greek politics in the early 2000s. Yet, he seems to stick to the same common thread as his predecessors in office since 2011: the persecution of the former head of ELSTAT, Andreas Georgiou, who took over as the head of the revamped Greek statistical office in August 2010 following the exposure in 2009 of how the national statistics had been falsified. Intriguingly, Georgiou and his staff have been persecuted relentlessly by political forces, whereas the falsification of the national statistics has not even been investigated at all. And not only that: those in positions of responsibility for the statistics from the time of falsified statistics sued Andreas Georgiou for slander and won at first instance civil court in 2017; since then, Georgiou’s hearing to appeal this decision has been continuously postponed, most recently to September 2020.

Just like Icelanders, Greeks earned a lot of sympathy when Greece tumbled into a financial crisis in 2009. But the Greek crisis exposed that the political ruling class in Greece had, since the end of the 1990s, falsified the Greek national statistics, i.e. the government deficit and debt were considerably higher than the published figures showed. For example, the deficit in 2006, 2007 and 2008 had been presented in official Greek statistics in mid-2009, just before the Greek crisis erupted, at 2.8%, 3.6% and 5% of GDP, respectively. However, the real figures, which were calculated by ELSTAT, the reformed statistical office, in 2010, were about double that, reaching 6.2%, 6.8% and 9.9% of GDP, respectively. And the government debt, which had been misreported at oscillating from 96 to 99% of GDP those years, was actually rising and had reached 110% of GDP by end 2008.

After years of legal wrangling, there seems to be no end in sight of the persecutions of the statistician who put Greek statistics on the path stipulated by European regulations on national statistics. Persecutions, which are an affront to Greek and European rule of law on many counts. If the Greek Government of Mitsotakis wants to confirm that the bad habits of falsified statistics are well and truly over and that Greece is firmly in the core of the European Union, it should give the Greek courts an opportunity to right a wrong and to exonerate Andreas Georgiou instead of punishing him for doing his job according to the European and Greek law.

Exposed: Greek statistical frauds… from 1997 to 2003

Greek statistics, as they are now for the years before the crisis hit, are not what Greek statistics were showing before autumn of 2009. Not for the first time, there was a lingering suspicion that not all was well with Greek statistics. Before joining the euro in 2001, the Greek budget deficit and public debt dived miraculously low, well below their less glorious average in the years before joining the euro. Although only the deficit figure ever went below the required Maastricht criteria, Greece was allowed to join the euro.

The lingering suspicion was there for a reason. Already in 2004 Eurostat had discovered that the debt and deficit dip around the euro entry was no miracle but manipulation: Greek authorities simply reported the wrong figures. In 2004, Eurostat’s Report on the revision of the Greek government deficit and debt figures showed that this had been an on-going story from 1997 to 2003.

Consequently, the Greek statistical authorities, the then National Statistical Service of Greece, NSSG, was forced to revise its data upward for the years 1997 to 2003, including for the test year of 1999 for Greece’s entry into the Eurozone, above the criteria set by the EU for Greece: Revisions in statistics, and in particular in government deficit data, are not unusual… However, the recent revision of the Greek budgetary data is exceptional.” – The unusual aspect was that the wrong figures did not stem from missing or faulty data but from deliberate misreporting. The real figures were dismal so “better” figures, even though wrong, were reported.

Exposed again in 2009: repeated falsifications of national statistics

After the exposure in 2004, Greek statistics were under intense and unprecedented scrutiny. But NSSG was not prepared to abandon its earlier bad practices. In autumn 2009 the ECOFIN Council requested a new report, this time from the EU Commission, due to “renewed problems in the Greek fiscal statistics” after the “reliability of Greek government deficit and debt statistics (has) been the subject of continuous and unique attention for several years.”

Greek figures on debt and deficit had, yet again, significant problems: First, deficit forecasts for 2009 changed drastically between March 2009 and September 2009 and then the forecasts changed again even further in October 2009. Regarding the actual statistics, the EC report on Greek Government Deficit and Debt Statistics, published in January 2010, showed that the statistics for the actual 2008 deficit had been revised upward significantly (by 2.7 % of GDP). Again, as the report pointed out, such a revision was rare in EU member states “but have taken place for Greece on several occasions.” Once the real statistics for 2009 were available in April 2010, the numbers proved to be higher than any of the projections provided earlier and previous years’ statistics were again revised upwards.

As earlier, the faulty statistics had not been produced solely at the NSSG but were also made with components produced at the General Accounting Office (GAO) and other parts of the Ministry of Finance, as well as other public sector institutions responsible for providing data to NSSG. There was political interference and “deliberate misreporting” with the NSSG, GAO, MoF and other institutions involved in the reporting all playing their part, according to the January 2010 EC report. In total, the word “misreporting” was used eight times in the report.

Events before the setting up of ELSTAT and Georgiou’s time there

The Goldman Sachs, GS, off-market swap story was one chapter in the faulty statistics saga and one of many examples of misreporting affecting government deficit and debt statistics. In 2008, when Eurostat made official enquiries in all member states on off-market swaps, Greek authorities informed Eurostat promptly that the Greek state had engaged in nothing of the sort.

This statement turned out to be a blatant lie as Eurostat found out when investigating the matter in 2010; the findings were published in a Eurostat report (p.16) in November 2010. By 2009, this misreporting was understating the level of the Greek government debt by 2.3 percent of GDP. As with many other examples of faulty statistics, this misreporting, on the off-market swaps and the ensuing effect on government debt, was not a single event but a deceit running for years, in this case since 2001, where several Greek government agencies played their part.

Needless to say, fiddling with the numbers did not eradicate the actual debt and deficit problem. While this deceit was being uncovered in the last quarter of 2009 and early 2010, Greece was losing access to markets. Negotiations on a bailout were complicated by unreliable information on Greek public finances. On May 2, 2010, as the first Greek Memorandum of Understanding was signed, accompanied by a €110bn loan – €80bn from European institutions and €30bn from the IMF – it was clear that the crucial figures of debt and deficit might still go up.

Following these major failures at the NSSG, its head had resigned in mid-October 2009. With the new government of George Papandreou taking office in early October 2009, there were changes at the leadership of the MoF and the GAO, with a new minister, vice minister and general secretaries. However, the ranks below remained unchanged, as did the mentality.

With a new government and following these exposures the laws on official statistics were changed in the spring of 2010. NSSG was abolished, replaced by a new statistical office, ELSTAT. Andreas Georgiou, who having been with the IMF for more than 20 years, returned home to be the head of the new statistical office. After Georgiou took over, the last upward revisions to government deficit and debt data were done.

The context of the 2009 deficit and the statistical adjustments 2009 to 2010

It is important to keep in mind the context for the 2009 deficit: there was the forecasted deficit of 3.9% of GDP, put forth by the MoF and conveyed to the European Commission by NSSG in April 2009 and then the estimate of the actual 2009 deficit of 13.6%, as produced and reported by NSSG in April 2010. All of this, an upward adjustment of almost 10 percentage points of GDP, took place before Georgiou took over at ELSTAT in August 2010.

With the 2009 deficit number of 13.6% in April 2010, way up from the originally forecasted 3.9%, it was still clear and publicised by Eurostat that the final figure could be higher. As indeed it was: the final adjustment from 13.6% to 15.4% was made by Georgiou and his team. The actual monetary figure behind the last revision of the deficit figure was about 4 billion euro.

This final adjustment made by Georgiou and his team seemed at the time wholly innocuous and a straightforward continuation of the earlier and much larger adjustments. But things were changing in Greece, though not in the direction of what those hoping for new and better times in Greece, would have hoped for.

The worm pit of Greek politics

Greek politics was a veritable worm pit during these months of fears over the country’s finances as the Papandreou government negotiated rescue packages and bailouts – in May 2010 and in June 2011 – with the IMF and European institutions.

After the elections that New Democracy lost in early October 2009, Antonis Samaras replaced the long-standing and earlier so powerful leader of the party of 12 years, Kostas Karamanlis. Karamanlis had been prime minister from 2004 until he lost the elections in 2009, that is during the time of the second round of the fraudulent statistics. In a much-noted speech in September 2011, Samaras attacked George Papandreou, accusing him of manipulating the statistics after Papandreou came to power in 2009, claiming Papandreou had done this only to discredit Kostas Karamanlis. This speech proved fateful, not for Papandreou but for ELSTAT’s president Andreas Georgiou.

Shortly after the Samaras’ speech, Georgiou was called to the parliament to explain the revision of the deficit and debt figures he had done. He was accused of ignoring national interests and inflating the 2009 figures under instruction of Eurostat to push Greece into the Adjustment Programme, set up to save the Greek state.

This narrative ignored four facts: the main corrections had been done before Georgiou took over at ELSTAT; Georgiou followed the same European regulation on national accounts statistics (Regulation 2223/96) and the same European Statistics Code of Practice as all other statistical offices in the EU; Greece had entered the Adjustment Programme three months before Georgiou took over at ELSTAT; Greece had repeatedly reported faulty data up to 2004 and then again up to end of 2009.

Political figures both on the left and the right of the political spectrum united against the ELSTAT president as if the only reason for the country’s debt and deficit problems were the statistics. The Greek Association of Lawyers even accused Georgiou of high treason.

Politicians unite in finding a scapegoat for the crisis: ELSTAT staff

In addition to the parliamentary hearing, the Samaras’ speech sat another thing in motion: a prosecutor opened a case against Georgiou and two ELSTAT managers and eventually pressed criminal charges in January 2013. In August 2013 an investigating judge recommended that the case be dropped as nothing was found to merit taking the case further.

However, political interventions, out in the open for all to see, kept the case alive in the Greek judicial system where it has been like a yo-yo: two additional times, in 2014 and 2015, prosecutors proposed that the case be dropped. However, what followed were interventions from nearly all sides of the political spectrum, fuelling the narrative of “false statements on the 2009 deficit and debt,” thus allegedly causing the Greek state to suffer staggering damages. A narrative that pushed the case to trial where the punishment should be relative to the damages, calculated to amount to €171bn, effectively amounting to a prison sentence for life.

In 2015 the charges against Georgiou and two ELSTAT managers, for allegedly making false statements on the 2009 statistics, were dropped by the Appeals Court Council after proceedings behind closed doors. However, this decision was annulled by the Supreme Court in 2016 after a proposal by Greece’s Chief Prosecutor and the Appeals Court Council, with new members, had to reconsider the case.

In 2017, the Appeals Court Council decided again to drop the charges, but the Supreme Court yet again annulled the decision, following yet another proposal for annulment by the Chief Prosecutor, an extraordinary move in Greek legal history. Then, in March 2019, the Appeals Court Council, under yet a new composition, decided for a third time to drop the charges against Georgiou and two senior staff regarding the alleged inflation of the deficit. This time, the decision was not annulled by the Supreme Court.

An acquittal that did not end the case

However, charges against Georgiou for alleged violation of duty, for not bringing the 2009 revised deficit and debt figures to a vote by the former board of ELSTAT before their publication in November 2010, were upheld. This, despite proposals to the contrary, by various investigating judges and prosecutors assigned to the case on three different occasions, in 2013, 2014 and 2015. Eventually, Georgiou was tried in open court in 2016 and acquitted.

However, this acquittal did not put an end to the case: ten days later, and before even the rationale of the acquitting decision had been made available, another prosecutor annulled the acquittal and Georgiou had to be retried in a “Double Jeopardy” trial in 2017. He was convicted to two years in jail, a suspended sentence unless he gets another conviction within three years. Georgiou appealed to the Greek Supreme Court, but his appeal was rejected, and the conviction sustained in a 2018 Supreme Court decision.

In court, Georgiou had argued that he was following both Greek and EU law, which refer to the European Statistics Code of Practice, making it clear that the head of the statistical authority has the “sole responsibility for deciding on statistical methods, standards and procedures, and on the content and timing of statistical releases”.

Georgiou requested the Greek courts to put – as provided in the Treaties – a pre-trial question to the European Court of Justice on the matter of the interpretation of the European Statistics Code of Practice in this matter; the courts ignored Georgiou’s request. Instead the convicting decision chose to use a blatantly false translation and interpretation of the European Statistics Code of the Practice asserting that “sole responsibility for deciding” does not really mean what is stated in the Code.

It seems safe to conclude that the conviction of Andreas Georgiou to two years in jail for not putting up the revised deficit and debt statistics to a vote does not rhyme with Greek and European rule of law. If the Greek Government of Mitsotakis wanted to set Greece back on the right track in this fundamental area and show that Greece is firmly in the core of the EU, it should initiate a re-examination of the case and give the Greek courts an opportunity to right a wrong and to exonerate Andreas Georgiou as he did his job according to the European and Greek law.

Further, two criminal cases

There are also two other ongoing criminal cases in Greece involving Andreas Georgiou.

In September 2016, the Chief Prosecutor of Greece ordered a new, preliminary criminal investigation into allegedly the 2009 deficit figures. This case, not the same as the case in which Georgiou and the two ELSTAT staff were acquitted in 2019, implicated not only Georgiou and the two ELSTAT staff for inflating the deficit figures but also officials from the European Commission, Eurostat and the IMF. So far, no charges have been pressed and Georgiou has not been summoned by the assigned prosecutor.

Another criminal case against Andreas Georgiou is with regard to his requesting ELSTAT staff in 2013 to sign a statistical confidentiality declaration, as required under the European Statistics Code of Practice, Indicator 5.2, for the purpose of protecting the private information of households and enterprises. There were two separate preliminary criminal investigations initiated in mid-2013 related to the Code, later combined into one. To this date no charges have been pressed but, as with the above-mentioned case, there is no evidence that the case has been closed.

If Greece and its political class wants to stop the scapegoating, all these cases against Andreas Georgiou ought to be dropped.

In addition to criminal cases: civil cases

In 2014, a civil case for criminal slander was brought against Georgiou. The plaintiff was Nikos Stroblos, who had been director of national accounts of the Greek statistics office in 2006 to 2010. Stroblos claimed Georgiou had engaged in criminal slander when he, as head of ELSTAT issued a press release in 2014, defending the final revised 2009 deficit and debt statistics produced by ELSTAT after Georgiou took over. The press release was published because of the legal proceedings since 2011 and the continuous attacks from most of the Greek political spectrum.

In 2017, the First Instance Civil Court decided that Georgiou had committed what is called in Greek legal terminology “simple slander,” meaning that what Georgiou said in his press release was true but had hurt the plaintiff’s reputation, (as opposed to “criminal slander”, whereby false statements are made to hurt somebody’s reputation). Thus, the court decided that Georgiou told the truth but he should not have made the statement he did. To atone for this, Georgiou was obliged to pay a compensation to the plaintiff and make a public apology in the Greek newspaper, Kathimerini, in the form of publishing large parts of the court decision against him.

When Georgiou appealed the decision, things took a peculiar turn: the appeal hearing has been postponed time and again. The last delay happened in January this year: the case was scheduled for January 16 but then postponed, for more than nine months, until September 24, 2020.

There is a peculiar irony here: Georgiou is appealing a court decision that found him guilty of “simple” slander for publicly defending his agency’s work; in layman’s terms, he was found liable for making true statements that happened to hurt someone’s reputation, an actual crime in Greece. If found liable, the person who restored the credibility of Greek statistics will have to publicly apologize to the person who was fudging the data previously and pay him compensation. This outcome would further damage Greece’s troubled image in the eyes of the global community.

European Convention on Human Rights: cases should be heard within a reasonable time

Now, six years after this civil case started, and nine years after Georgiou was first put under investigation, he and his family are still living with these never-ending court proceedings and the eternal postponements. It is of interest to keep in mind Article 6.1. of the European Convention on Human Rights: In the determination of his civil rights and obligations or of any criminal charge against him, everyone is entitled to a fair and public hearing within a reasonable time by an independent and impartial tribunal established by law.

Interestingly, one of Stroblos’ witnesses in the civil suit against Georgiou is Nikos Logothetis, who was vice-chairman of the board of ELSTAT when the board had demanded to vote on the revised 2009 deficit and debt figures in November 2010. Only weeks earlier, Logothetis was forced to resign from the ELSTAT board after the Greek police found that Logothetis had hacked Georgiou’s private email. A criminal investigation was opened against Logothetis at that time and in early 2011 two charges, of felony and misdemeanour, were pressed against him.

However, both cases against him were dropped for reasons that are difficult to fathom in the context of the rule of law and how Georgiou’s cases have fared in the Greek courts: one case was dropped as the court did not consider it before the five-year statute of limitations expired; the other case was thrown out because a receipt for a €20 fee, due when a complaint is filed, could not be found in the court file. And then, as if this was not scandalous enough, the court later met Logothetis’ request: that his computer, which the police had previously confiscated and which still contained Georgiou’s stolen emails, should be handed back to him.

International support for Georgiou – but that does not save him from the persecutions

There have been many instances of international support for Andreas Georgiou over the years. Below are some examples of recent ones.

The European Commission has repeatedly mentioned Georgiou’s case in its periodic reports of the post-program reviews for Greece. In its November 2019 Enhanced Surveillance Report it noted: The Commission has continued to monitor developments in relation to the legal proceedings against … the former President and senior staff of the Hellenic Statistical Authority. The case against the former Hellenic Statistical Authority President A. Georgiou related to charges filed in connection with fiscal statistics has been irrevocably dismissed. An appeal introduced by Mr. Georgiou in a civil defamation lawsuit is scheduled to be heard in January 2020.”

The International Statistical Institute noted in a statement published in December 2019: “It is of great concern to us that the legal harassment of Mr Georgiou is not yet over. There are three legal cases against him in Greece which are still open. He took these actions in accordance with statistical principles in his capacity as head of the national statistics office… Defending official statistics, as required by the UN Fundamental Principles of Statistics and the European Statistics Code of Practice, should not lead to any legal proceedings and even less to damages being awarded and public apologies. Now is the time for a fresh start in Greek statistics, and the ending of the victimisation of Mr Georgiou.”

The Board of the American Statistical Association also issued a statement in December 2019 stating inter alia that the Association was “troubled by Greece’s continued persecution of its former head statistician. Now in the ninth year, there are still open investigations and trials of Georgiou, a government professional who is loyal to his country. Greece’s new government provides an opportunity to remedy the unjust official treatment of Georgiou. Ending the prosecutions, accusations and legal proceedings and exonerating Georgiou would signal Greece’s commitment to accurate and ethical official statistics. This, in turn, could help foster foreign investment and overall confidence among Greece’s international partners, which helps Greece’s economy.”

Political witch hunt

In August 2017, Nikos Konstandaras columnist at Kathimerini and the New York Times warned that the Georgiou affair was “a witch hunt, not a thirst for justice.” Konstandaras concluded:

Beyond the injustice and the terrible personal cost for a fellow citizen, beyond the damage to the country’s credibility, the most tragic aspect of the affair is that people who know how dangerous this all is are investing in fantasies and encouraging fanaticism.

History, though, will record the role they played. In the end they will be loaded with more blame than that which they are trying to saddle onto others.

Now, more than two and a half years after this was written, the persecution of a civil servant who did what he was supposed to do, is still ongoing. Much to the shame of Greece the man who led ELSTAT from August 2010 to August 2015, putting in procedures for correct reporting of statistics following the exposure of fraudulent statistics for over a decade, is being prosecuted. At the same time, the people who for years provided false and fraudulent statistics to Greece, European authorities and the world, enjoy total impunity and even participate and benefit from Georgiou’s prosecutions.

In an article in the Washington Post as recently as 2 January this year, Georgiou’s case was brought up, pointing out how both professional rivals and politicians had decided to scapegoat Georgiou during the contagious time he was in office, creating the narrative that “he had “inflated” the deficit to “trap” Greece into accepting bigger international bailouts, with harsher conditions, than it needed.”

As pointed out, “the Greek government has changed hands multiple times” since the legal cases against Georgiou started, a particularly damning point for Mitsotakis and his government. “So far, though, those in power have continued to foment or tolerate the scapegoating of civil servants, and refused to help Georgiou clear his name.”

A worrying disincentive to service truthful information

The numerous prosecutions are utterly damning for the Greek political system. Equally, that the IMF and EU have not been able to adequately and decisively assist the quest for truthful statistics. It is a travesty of the rule of law that a civil servant has for more than eight years been persecuted for doing his job truthfully, to the professional standards expected of his office. A travesty that is harmful for not only for Greek civil servants and their work but elsewhere. Or, as concluded in the Washington Post article 2 January:

“And make no mistake: Georgiou may be the primary victim of this weaponization of the judicial system, but he is hardly its only target. Other civil servants — in Greece and in other countries weighing their commitment to rule of law — are watching and learning what happens when a number cruncher decides to tell the truth.”

In December 2016, Georgiou said to Icelog: “The numerous prosecutions and investigations against me and others that have been going on for years – as well as the persistence of political attacks and the absence of support by consecutive governments – have created disincentives for official statisticians in Greece to produce credible statistics. As a result, we cannot rule out the prospect that the problem with Greece’s European statistics will re-emerge. The damage already caused concerns not only official statistics in Greece, but more widely in the EU and around the world, and will take time and effort to reverse.”

How can Greece, the political class in Greece, face the fact that an innocent man is persecuted, and the real fraud of national statistics has never been investigated?

*Icelog has followed the Georgiou case since I visited Greece in 2015. See here for earlier blogs on the case.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

The Luxembourg walls that seem to shelter financial fraud

People, mostly pensioners, who previously took out equity release loans with Landsbanki Luxembourg, have for a decade been demanding that Luxembourg authorities look into alleged irregularities, first with the bank’s administration of the loans, then how the liquidator dealt with their loans after Landsbanki failed. The Duchy’s regulator, CSSF, has staunchly refused to consider this case. Yet, following criminal investigations in Iceland into the Icelandic banks, where around thirty people have been found guilty and imprisoned over the years, no investigation has been opened in Luxembourg into the Duchy operations of the Icelandic banks so far. Criminal investigation in France against the Landsbanki chairman at the time and some employees ended in January this year: all were acquitted. Recently, investors in a failed Luxembourg investment fund claimed the CSSF’s only interest is defending the Duchy’s status as a financial centre.

Out of many worrying aspects of the rule of law in Luxembourg that the Landsbanki Luxembourg case has exposed, the most outrageous one is still the intervention in 2012 of the State Prosecutor of Luxembourg, Robert Biever. At the time, a group of the bank’s clients, who had taken out equity release loans with Landsbanki Luxembourg, were taking action against the bank’s liquidator Yvette Hamilius. Then, out of the blue, Biever, who neither at the time nor later, had investigated the case, issued a press release. Siding with Hamilius, Biever stated that a small group of the Landsbanki clients, trying to avoid paying back their loans, were resisting to settle with the bank.

Criminal proceedings in Iceland against managers and shareholders of the Icelandic banks, where around 30 people have been found guilty, show that many of the dirty deals were carried out in Luxembourg. Since prosecutors in Iceland have obtained documents in Luxembourg in these cases, all of this is well known to Luxembourg authorities. Yet, neither the regulator, Commission de Surveillance du Secteur Financier, CSSF, nor other authorities have apparently seen any ground for investigations, with one exception. A case related to Kaupthing has been investigated but, so far, nothing has come out of that investigation (here more on that case, an interesting saga in itself).

However, it now seems that not only the Landsbanki Luxembourg clients have their doubts about on whose side the CSSF really is. Investors in a Luxembourg-registered fund claim they were defrauded but that the CSSF has been wholly unwilling to investigate their claims. Their conclusion: the CSSF’s only mission is to promote Luxembourg as a financial centre, which undermines “its responsibility to protect investors.”

That would certainly chime with the experience of the Landsbanki clients. Further, the fact that Luxembourg is a very small country, which greatly relies on its financial sector, might also explain why the Landsbanki Luxembourg clients have found it so difficult even to find lawyers in Luxembourg, willing to take on their case.

A slow realisation – information did not add up

It took a while before borrowers of equity release loans from Landsbanki Luxembourg started to suspect something was amiss. The messages from the bank in the first months after the liquidators took over, in October 2008, were that there was nothing to worry about. However, it quickly materialised that there was indeed a lot to worry about: the investments, which had been made as part of the loans, seemed to have been wiped out; what was left was the loan, which had to be paid off.

In addition, there were conflicting information as to the status of the loans, the amounts that had been paid out and the status on the borrowers’ bank accounts. The borrowers, mostly elderly pensioners in France and Spain, many of them foreigners, took out loans with Landsbanki Luxembourg, with their properties in these two countries as collaterals. To begin with, they were to begin with dealing with this situation alone, trying to figure out on their own what was going on. It took the borrowers some years until they had found each other and had founded an action group, Landsbanki Victims Action Group.

Landsbanki clients in Spain are part of an action group in Spain against equity release loans, The Equity Release Victims Association, Erva. The Landsbanki clients have taken the Landsbanki estate to court in Spain in order to annul the administrator’s recovery actions there. Lately, the clients have been winning but given that cases can be appealed it might take a while to bring these cases to a closure. The administrator’s attempt to repatriate Spanish court cases against the bank to Luxembourg have, so far, apparently not been successful.

Criminal case in France, civil cases in France and Spain

Finding a lawyer, both for the group and the single individuals who took action on their own, proved very difficult: it has taken a lot of time and effort and been an ongoing problem.

By January 2012, a French judge, Renaud van Ruymbeke, had opened an investigation into the loans in France. The French prosecutor lost the case in the Criminal Court of First Instance in Paris in August 2017; on 31 January 2020, the Paris Appeal Court upheld the earlier ruling, acquitting Landsbanki Luxembourg S.A., in liquidation and some of its managers and employees at the time. The case regarded the operations before the bank’s collapse, the administrator was not prosecuted. The Public Prosecutor as well as the borrowers, in a parallel civil case, have now challenged the Paris Appeal Court decision with a submission to the Cour de cassation.

While this case is still ongoing, the administrator’s recovery actions in France were understood to be on hold. According to Icelog sources, that has not entirely been the case.

Landsbanki Luxembourg: opacity before its demise in October 2008

The main issues with the bank’s marketing and administration of the loans has earlier been dealt with in detail on Icelog but here is a short overview:

As Hamilius mentioned in an interview in May 2012 with the Luxembourg newspaper Paperjam, the loans were sold through agents in Spain and France. After all, the whole operation of the equity release loans depended on agents; Landsbanki Luxembourg was operating in Luxembourg, not in France and Spain.

The use of agents has an interesting parallel in how foreign currency loans, FX loans, have been sold in Europe (see Icelog on FX loans and agents). In the case of FX loans, the Austrian Central Bank deemed that one reason for the unhealthy spread of these risky loans was exactly because they were sold through agents. Agents had great incentives to sell the loans and that the loans were as high as possible but no incentive to warn the clients against the risk. Interestingly, the sale of financial products through agents has been found illegal in some European cases regarding FX loans.*

Other questions relate to how the equity release loans were marketed, i.e. the information given, that the bank classified the borrowers as professional investors, which greatly diminished the bank’s responsibility in informing the clients and also what sort of investments they would choose for the investment part of the loan. Life insurance was a frequent part of the package, another familiar feature in FX loans.

Again, given rulings by the European Court of Justice on FX loans, it seems incomprehensible that the same conditions should not apply to equity release loans as FX loans. After all, there are exactly the same issues at stake, i.e. how the loans were sold, how borrowers were informed and classified (as professional investors though they clearly were not).

How appropriate the investments were for these types of loans and clients is an other pertinent question in this saga. After the collapse of Landsbanki Luxembourg, the borrowers discovered to their great surprise that in some cases the investments were in Landsbanki bonds, even in its shares, as well as in shares and bonds of the two other Icelandic banks, Glitnir and Kaupthing.

That the bank would invest its own loans in the bank’s bonds is simply outrageous. Already in analysis of the Icelandic banks made by foreign banks as early as 2005 and 2006, the high interconnection of the Icelandic banks, was seen as a risk. Thus, if the CSSF had at all had its eyes on these investments, made by a bank operating in Luxembourg, the regulator should have intervened.

It was also equally wholly unfitting to buy bonds in the other Icelandic banks: their credit default swap, CDS, spread made their bonds far from suitable for low-risk investments. – Interestingly, the administrator confirmed in the Paperjam interview 2012 that the loans were indeed invested in short-term bonds of Landsbanki and the two other banks: thus, there is no doubt that this was the case. – Only this fact per se, should have made the liquidator take a closer look at the time.

The value of the properties used as collaterals also raises questions. The sense is that the bank wanted to lend as much as possible to each and every borrower, thus putting a maximum value of the properties put up as collateral.

One of many intriguing facts regarding the Landsbanki Luxembourg equity release loans exposed in the French criminal case was when French borrowers told of getting loan documents in English and English borrowers of getting documents in French. As pointed out earlier on Icelog this seems to indicate a concerted effort by the bank to diminish clarity (at least in some cases, clients were promised they would get the documents in their language of choice, i.e. English borrowers getting documents in English, but the documents never materialised).

Again, this raises serious questions for the CSSF: did the bank adhere to MiFID rules at the time? And did the liquidator really see nothing worth reporting to the CSSF?

Landsbanki Luxembourg: opacity after its demise in October 2008

After Landsbanki Luxembourg failed in October 2008, Yvette Hamilius and Franz Prost were appointed liquidators for Landsbanki. Following Prost’s resignation in May 2009, Hamilius has been alone in charge. As the Court had originally appointed two liquidators the Court could have been expected to appoint another one after Prost resigned. That however was not the case. Not in Luxembourg. There have been some rumours as to why Prost resigned but nothing has been confirmed.

Be that as it may, the relationship between Hamilius and the borrowers has been a total misery for the borrowers. One of the things that early on led to frustration and later distrust were conflicting and/or unexplained figures in statements. Clarification, both on figures on accounts, and more importantly regarding the investments, was not forthcoming according to borrowers Icelog has heard from.

Hamilius’ opinion of the borrowers could be seen from the Paperjam interview in 2012 and from the remarkable statement from State Prosecutor Biever: the liquidator’s unflinching view was that the borrowers were simply trying to make use of the fact the bank had failed in order to save themselves from repaying the loans.

The interview and the statement from Biever came as a response to when a group of borrowers tried to take legal action against the Landsbanki Luxembourg and its liquidator. In the interview, Hamilius was asked if she was solely trying to serve the interest of Luxembourg as a financial centre, something she staunchly denied.

The action against Landsbanki Luxembourg has so far been unsuccessful, partly because Luxembourg lawyers are noticeably unwilling to take action against a bank, even a failed bank. In that sense, anyone trying to take action against a Luxembourg financial firm finds himself in a double whammy: the CSSF has proved to be wholly unsympathetic to any such claims and finding a lawyer may prove next to impossible.

Why was the investment part of the Landsbanki Luxembourg equity release loans killed off?

The key characteristic of equity release loans is that this product consists of a loan and investment, two inseparable parts. However, that proved not to be the case in the Landsbanki Luxembourg loans. Suddenly, after the demise of the bank, the borrowers found themselves to be debtors only, with the investment wiped out. This did fundamentally alter the situation for the borrowers.

The liquidator seems allegedly to have taken the stance that to a great extent, there was nothing to do about the investments in these cases where the bank had invested in Icelandic bank shares and bonds. That is an intriguing point: as pointed out earlier, the bank should never have been allowed to make these investments on behalf of these clients.

In Britain, as in many European countries, the law in general stipulates that if a lender fails, loans are not to be payable right away. As far as I can see, this counts for equity release loans as well: both parts of the loan should be kept going, the loan as well as the investment. Frequently, a liquidator sells off the package at a discount, for another company to administer, in order to be able to close the books of the failed bank.

This has not been the case in Landsbanki Luxembourg equity release loans, the investments were wiped out – and yet, Luxembourg authorities have paid no attention at all to the borrowers’ claims of unfair treatment by the liquidator.

As mentioned above, Hamilius’ version of the sorry saga is that the borrowers are simply unwilling to repay the loan.

The dirty deals of the Icelandic banks in Luxembourg

The recurrent theme in so many of the criminal cases in Iceland after the banking collapse 2008 against bankers and others related to the banks is the role of the banks’ subsidiaries in Luxembourg. The dirtiest parts of the deals were done through the Luxembourg subsidiaries (particularly noticeable in the Kaupthing cases). Since Hamilius has assisted investigations into Landsbanki in Iceland, she will be perfectly well aware of the Icelandic cases related to Landsbanki.

The administrators of the Icelandic banks in Iceland were crucial in providing material for the criminal proceedings in Iceland. Yet, as far as can be seen, the administrator has allegedly not deemed it necessary to take a critical look at the Landsbanki operations in Luxembourg. Which is why no questions regarding the equity release loans have been raised by the administrator with Luxembourg authorities.

The incredibly long winding-up saga at Landsbanki Luxembourg

One interesting angle of the winding-up of Landsbanki Luxembourg saga is the time it is taking. The administrators (winding-up boards) of the three large Icelandic banks, several magnitudes larger than Landsbanki Luxembourg, more or less finished their job in 2015, after which creditors took over the administration of the assets, mostly to sell them off for the creditors to recover their funds. The winding-up proceedings of LBI ehf., the estate of Landsbanki Iceland, came to an end in December 2015, when a composition agreement between LBI ehf. and its creditor became effective.

For some years now, the LBI ehf has been the only creditor of Landsbanki Luxembourg, i.e. all funds recovered by the liquidator go to LBI ehf. Formally, LBI ehf has no authority over the Landsbanki Luxembourg estate. Yet, it is more than an awkward situation since LBI ehf is kept in the waiting position, while the liquidator continues her actions against the equity release borrowers, whose funds are the only funds yet to be recovered.

That said, Luxembourg is not unused to long winding-up sagas. The fall of the Luxembourg-registered Bank of Credit and Commerce International, BCCI, in 1991, was one of the most spectacular bankruptcies in the financial sector at the time, stretching over many countries and exposing massive money laundering and financial fraud. Famously, the winding-up took well over two decades, depending on countries. Interestingly, Yvette Hamilius was one of several administrators, in charge of the process from 2003 to 2011; the winding-up was brought to an end in 2013.

The CSSF on a mission to protect its financial sector, not investors

Recently, another case has come up in Luxembourg that throws doubt on whose interest the CSSF mostly cares for: the financial sector it should be regulating or investors and deposit holders. A pertinent question, as pointed out in an article in the Financial Times recently (23 Feb., 2020), since Luxembourg is the largest fund centre in Europe, with €4.7tn of assets under management and gaining by the day as UK fund managers shift business from Brexiting Britain to the Duchy.

The recent case seems to rotate around three investment funds – Columna Commodities, Aventor and Blackstar Commodities – domiciled in Luxembourg, sub funds of Equity Power Fund. As early as 2016, the CSSF had expressed concern about the quality of the investments: astoundingly, 4/5 of the investments were concentrated in companies related to a single group. Lo and behold, this all came crashing down in 2017.

The investors smelled rat and contacted David Mapley at Intel Suisse, a financial investigator who specialises in asset recovery. Mapley has a success to show: in 2010 he won millions of dollars from Goldman Sachs on behalf of hedge funds, which felt cheated by the bank.

In order to gain insight into the Luxembourg operations, Mapley was appointed a director of LFP I, one of the investment funds in the Equity Power Fund galaxy. (Further on this story, see Intel Suisse press release August 2018 and coverage by Expert Investor in January and October 2019.)

According to the FT, the directors of LFP I claim the CSSF has not lived up to its obligation under EU law. They have now submitted a complaint against the CSSF to European Securities and Markets Authority, Esma, which sets standards and supervises financial regulators in the EU.

In a letter to Esma, Mapley states that the CSSF’s “marketing mission to promote Luxembourg as a financial centre” has undermined its focus on protecting investors. Mapley also alleges the CSSF has attempted to quash the directors’ investigations into mismanagement and fraud by the funds’ previous managers and service providers in order to undermine the funds’ efforts “and prevent any reputational risk”. – That is, the reputational risk of Luxembourg as a financial centre.

As FT points out, investors in a Luxembourg-listed fund that invested in Bernard Madoff’s $50bn Ponzi scheme have also accused the CSSF of leniency, i.e. sheltering the fraudster and not the investors.

Luxembourg, the stain on the EU that EU is unwilling to rub off

Worryingly, the CSSF’s lenient attitude might be more prominent now than ever as Luxembourg competes with other small European jurisdictions of equally doubtful reputation such as Cyprus and Malta (where corrupt politicians set about to murder a journalist, Daphne Caruana Galizia, investigating financial fraud; brilliant Tortoise podcast on the murder inquiry) in attracting funds leaving the Brexiting UK. Esma has been given tougher intervention powers, though sadly watered down from the original intension, in order to hinder a race to the bottom. It is very worrying that the EU does not seem to be keeping an eye on this development.

As long as this is the case, corrupt money enters Europe easily, with the damaging effect on competition, businesses, politics – and ultimately on democracy.

*Foreign currency loans, FX loans, have been covered extensively on Icelog, see here. For a European Court of Justice decision in the first FX loans case, see Árpád Kásler and Hajnalka Káslerné Rábai v OTP Jelzálogbank Zrt, Case C‑26/13.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

No end to the Greek government’s relentless persecution of ELSTAT staff

In spite of earlier promises to the Eurogroup the Greek government continues to persecute former head of ELSTAT Andreas Georgiou and two of his former senior staff. As long as the never-ending prosecutions continue the Greek government cannot claim it is seriously committed to turn the country around. By continuing these persecutions the Greek government is clinging to the story that the fraudulent statistics from around 2000 to 2009 are the correct ones, thereby in effect presenting the 2010 revisions as criminal misreporting. Thus, the Eurogroup and other international partners should refuse to cooperate with the Greek government as long as these trials continue.

In spite of earlier acquittals time and again, Greek authorities keep finding new ways to prosecute the former head of ELSTAT. The latest development happened last week, July 18 and 19. As at the trial in May, there was a shouting and insulting mob of around thirty people present in court at the trial on July 18 when Georgiou was being tried for alleged violation of duty. The mob was clearly cheering on the accusation witnesses in a disturbing way; again, something that would be unthinkable in any civilised country.

On July 19, the Chief Prosecutor of the Greek Supreme Court proposed yet again to annul the acquittal of Georgiou and two senior ELSTAT staff for allegedly intentionally inflating the 2009 government deficit and causing Greece a damage of €171bn.

Mob trial

After being unanimously found innocent of charges of violation of duty in December last year by a panel of three judges, as the trial prosecutor had recommended, this acquittal was annulled by another prosecutor. This is how this farce and mockery of justice has been kept going: acquittals are annulled and on goes the persecution.

This trial will now continue on 31 July when judgement is also expected – and it can be fully expected that Georgiou will be found guilty.

This report from Pastras Times gives an idea of the atmosphere at the trial: The professor [Z. Georganda] argued that from the data she has at her disposal, she considers that the 2009 government deficit was around 4 to 5% [of GDP] – a statement, which ignited the reaction of the audience that began applauding and shouting: “Traitors” “Hang them on Syntagma square”… The witness continued her point arguing that Greece had one of the lowest deficits “but we could and we were paying our debts because there was economic activity. Georgiou led the country to prolonged recession.” Ms. Georganda said characteristically, causing the audience to explode anew.

A pattern over six years: acquittals followed by repeated prosecution

As everyone who knows the story of the discoveries made in 2009 and 2010 of the Greek state statistics Georganda’s arguments are a total travesty of the facts, a story earlier recounted on Icelog (here the long story of the fraudulent stats and the revisions in 2010; here some blogs on the course of this horrendous saga).

July 19 was the deadline for the Chief Prosecutor of the Supreme Court, Xeni Demetriou to make a proposal for annulment of the decision of the Appeals Court Council to acquit Georgiou and two former senior ELSTAT staff of the charge of making false statements about the 2009 government deficit and causing Greece a damage of €171bn. Demitrou opted to propose to annul the acquittal decision.

The Criminal Section of the Supreme Court will now consider her proposal for the annulment of the acquittal. If the latter agrees with the proposal of the Chief Prosecutor of Greece, the case will be re-examined by the Appeals Court Council. If the Appeals Court Council, under a new composition, then decides to not acquit Georgiou and his colleagues, the three will be subjected to full a trial by the Appeals Court. If convicted they face a sentence of up to life in prison.

This would then be yet another round of the same case: in September 2015, the same Prosecutor of the Supreme Court, then a Deputy Prosecutor, proposed the annulment of the then existing acquittal decision of the Appeals Court Council. In August 2016, the Criminal Section of the Supreme Court agreed to this proposal, which is why the Appeals Court Council re-considered the case.

And so it goes in circles, seemingly until the legal process gets to the “right result” – trial and conviction.

Can the three ELSTAT staff get a fair trial?

Given the fact that the same case goes in circles – with one part of the system agreeing to acquittals, which then are thrown out, in the same case – it can only be concluded that Andreas Georgiou and his two ELSTAT colleagues are indeed being persecuted for fulfilling the standard of EU law, as of course required by Eurostat and other international organisations.

As this saga has been on-going for six years it seems that the three simply cannot get a fair hearing in Greece. This raises serious questions about the rule of law in Greece and the state of human rights there.

At the same time the last chapter in this six-year saga took place now in July, €7.7bn of EU taxpayer funds, a tranche of EU and IMF funds for Greece, was paid out. This, inter alia on the basis of the statistics revised in 2010, for which the Greek state keeps prosecuting the ELSTAT statisticians thereby de facto claiming these statistics were the product of criminal misreporting.

Tsakalotos breaks his promise

As reported earlier on Icelog the Eurogroup has clearly noticed the ELSTAT case: at the Eurogroup meeting of 22 May ECB governor Mario Draghi raised the matter, saying that as agreed earlier, priority should be given to implementing “actions on ELSTAT that have been agreed in the context of the programme. Current and former ELSTAT presidents should be indemnified against all costs arising from legal actions against them and their staff.”

Greek minister of finance Euclid Tsakalotos announced that “On ELSTAT, we are happy for this to become a key deliverable before July.”

In an apparent attempt to appease the Eurogroup, it was announced this week that ELSTAT will pay legal costs for the former ELSTAT employees facing trial. However, the legal provision proposed by the government is wholly inadequate and may actually do more harm than good to Georgiou and his colleagues.

For example, it says that these official statisticians will have to return any funds they get if they are convicted. This is legislating perverse incentives. It is like saying: Convict them otherwise we will have to pay them.

The proposed legislation also puts a very low limit on the amounts that would be covered. In addition, it would not cover costs of legal counsel, costs of interpretation of foreign witnesses, nor would it cover the cost of travel and accommodation of these witnesses when they come to Greece abroad to be defence witnesses for Georgiou. There also seems to be a labyrinthine process for accessing the funds making it unlikely the accused will ever see any reimbursement of cost.

It is thus quite clear from events this week that not only has Tsakalotos broken the promise he gave to Draghi and the Eurogroup in May – he clearly has no intention of keeping it. The question is how long the Eurogroup will tolerate broken promises and the fact that by prosecuting the ELSTAT staff the Greek government does indeed keep portraying the revised statistics as criminal misreporting.

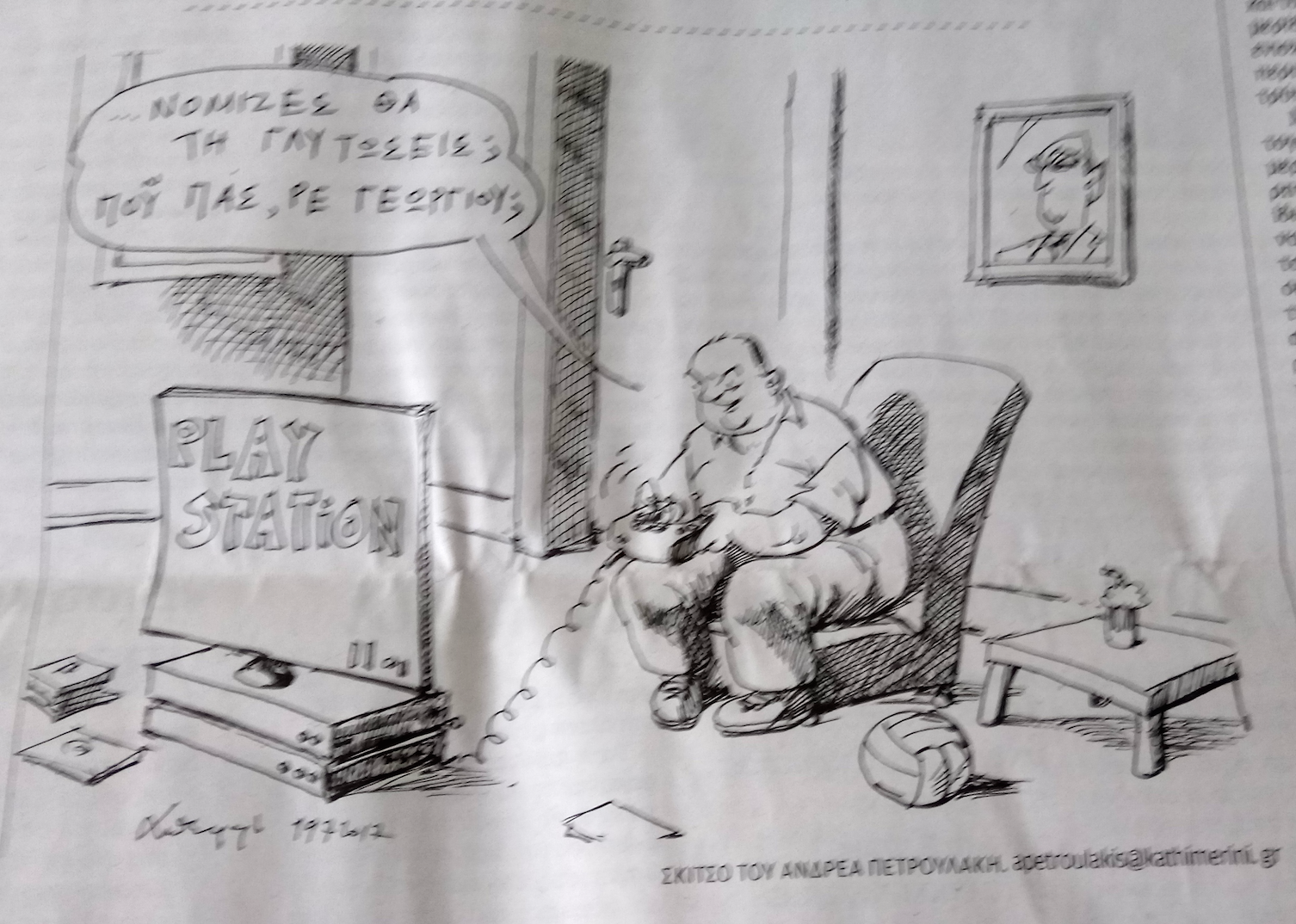

According the Kathimerini‘s cartoonist, the ELSTAT saga is a simple one: New Democracy PM 2004 to 2009 Kostas Karamanlis is unwilling to let go of the persecution – “You thought you would get away? Where do you think you are going, eh Georgiou?”

According the Kathimerini‘s cartoonist, the ELSTAT saga is a simple one: New Democracy PM 2004 to 2009 Kostas Karamanlis is unwilling to let go of the persecution – “You thought you would get away? Where do you think you are going, eh Georgiou?”

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Will the last bit of capital controls soon be removed?

Now that ordinary Icelanders can invest ISK100m abroad a year and buy one property abroad, life is returning back to normal after capital controls or at least for the 0.01% of Icelanders that will be able to make use of this new normal. This new CBI regime was put in place on the last day of 2016.

For all others, capital controls have for a long time not been anything people sensed in everyday life. The controls really were on capital, in the sense that Icelanders could not invest abroad, but they could buy goods and services, i.e. ordered stuff online and, mostly relevant for companies, paid for foreign services.

The almost only tangible remains of the capital controls regard the four large funds – Eaton Vance, Autonomy, Loomis Sayles and Discovery Capital Management – still locked inside the controls with their offshore króna (by definition króna owned by foreigners, i.e. króna owned by foreigners who potentially want to exchange it to foreign currency).

I’ve written extensively on this issue earlier, recently with a focus on the utterly misplaced ads regarding the policy of the Icelandic government (the policy can certainly be disputed but absolutely not in the way the ads chose to portray it; see here and here; more generally here). From over 40% of GDP end of November 2008, when the controls were put in place, the offshore króna amounted to ca. 10% of GDP towards the end of 2016 (see the CBI: Economy of Iceland 2016, p. 75-81.) The latest CBI data is from 13 January this year, showing the amount of offshore króna at ISK191bn, below 10% of GDP.

It now seems there have been high-level talks and as far as I can understand there is great willingness on both sides to find an agreement, which would most likely involve an exit rate somewhat less favourable than the present rate (meaning there would be some haircut for the funds, i.e. some loss) and also that they would exit over some period of time (they have earlier indicated that they are in no hurry to leave).

As before, the greatest risk here is political: will the opposition or parts of it, try to use this case to portray the government as dancing to the tune of greedy foreigners? Icelanders have had a share of the populism so prevalent in other parts of the world but Icelandic politics is by no means engulfed by it.

Arguments in this direction can’t be ruled out but the argument for solving the issue is that Iceland should be moving out of the long shadows of the 2008 collapse, the Central Bank has been buying up foreign currency in order to fetter the ever-stronger króna and this is a problem easier to solve now with the economy booming rather than at some point later in a more uncertain future.

Obs.: on 4 June 2016 the CBI announced a new instrument to “temper and affect the composition of capital inflows.” Some people call this a new form of capital controls. I don’t agree and see these measures, as does the CBI, as a set of prudence rules, announced as a possible course of action already in 2012. Over the last decades other countries have taken a similar course to prevent the inflow of capital that could in theory leave quickly.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Next step by offshore króna holders: call the IMF

Congressman Dennis A Ross has written a letter, see below, to Sunil Sabharval, US Executive Director at the International Monetary Fund, IMF, inquiring as to what US officials knew about the offshore króna actions taken by the Icelandic government. The Congressman’s mission is clearly to safeguard US interests, i.e. the interest of US funds holding offshore króna, a problem I have dealt with extensively in earlier blogs, inter alia here. Although not stated explicitly, the most sensitive underlying assets are sovereign securities, payable in Icelandic króna.

In the letter the reasons for the Icelandic collapse are somewhat simplified to say the very least, apparently easier to blame the government than the banks; also rather funny to see the offshore króna holders treated as entirely blameless lured by good deals, another saga.

The thrust of the letter is that since Iceland has now recovered well from its 2008 crisis Iceland shouldn’t be discounting the offshore króna or offering the investors punitive terms. – Further to this: intriguingly, Iceland had not made a loss on the 2008 banking crisis but a gain of 9% of GDP(!), according to the latest IMF Article IV Consultation statement on Iceland, from June 22.

The Congressman points out that the offshore króna holders (i.e. the largest holders) have come up with various solution but Icelandic authorities have been unwilling to take any notice. He now wants to know if US officials are aware of what is going on – and he expects an answer, which as far as I know has not yet been given. IMF has preached a cooperative approach to lift capital controls, reiterated in its June statement on Iceland but seems to consent with the action taken by Icelandic authorities re the offshore króna.

Here is Congressman Ross’ letter:

Last time, this time – in general

As I recounted at length in the years, months and days up to the plan to lift capital controls on the estates of the banks, presented June 8 last year, Icelandic authorities dithered for long due to infighting until they took the plunge – to be fair, the authorities claimed it just took time to prepare the plan and refused all allegations of infighting. But the plunge wasn’t taken until it was clear the plan was supported by the largest creditors.

The same now with the offshore króna action, it all took longer than had been planned, my understanding is that it took long because of different views; however, those involved say it just took the time it took, complicated matters etc. Yet, this time the government acted unilaterally, no agreement with the largest offshore króna holders. Thus inter alia the above letter, I assume.

The government claims the offshore króna holders do not act as a group, contrary to the creditors to the old banks. That isn’t wholly correct – each estate had to be dealt with separately and support was sought for each estate. Thus, the creditors were not a unified group but three groups. So much for that argument now re the offshore króna holders.

As a ground for pride Bjarni Benediktsson minister of finance has pointed out that there was no legal aftermath to the plan last year. Quite true but that’s because the plan wasn’t passed until creditors’ support was ensured. Which is exactly the opposite of now where the government has acted unilaterally re the offshore króna holders who consequently have taken the first steps towards legal action.

In addition, there is the concern Congressman Ross shows, as well as articles in the Wall Street Journal and FT Alphaville, as I have mentioned in earlier blogs – offshore króna holders are clearly trying to point out to the world that Iceland, by planning a haircut on the offshore króna assets (when they are converted into foreign currency) doesn’t intend to honour its international commitments.

Last time, this time – in particular

I have earlier pointed out that I was wondering if the Icelandic government was going to make use of some “tricky teleological interpretation” in its dealings with offshore króna holders.

I didn’t explain in any detail what I had in mind but here it is:

Long before the June 8 plan last year, the Icelandic government claimed it couldn’t possibly have anything to do with the composition of three private banks. Right, except that composition was meaningless if it wasn’t clear beforehand how much of the Icelandic assets creditors (only 10% of the assets went to Icelandic creditors, mostly the CBI) could convert into foreign currency. Composition agreement couldn’t be reached until the government had found a solution i.e a haircut, which the creditors could agree to – that was what mostly took so long to solve.

This time, the core of the offshore króna problem is similar regarding sovereign securities. The government can claim that it’s honouring all its obligations as it will pay out any such securities in full and on time… in króna. The thing is that offshore króna holders can – or could, the auction is now over – either choose to convert at ISK190 a euro (the onshore rate is now ISK136, was ISK139 at the time of the auction) or have their króna kept on a special deposit account at 0.5% interest rates with no maturity in sight. The question is if this is seen as fair… or not.

Last year, the government came to the conclusion that it had to step in to facilitate a composition. Now, it’s just shrugging its shoulder and the message is, as I’ve stated earlier, “let them litigate” – alors, last year, the goal was to prevent legal action, this year it’s bring it on…

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

An auction that didn’t solve the problem and the past as an aberration

The outcome of the offshore króna auction 16 June has now been made public: offers at the rate of ISK190 a euro or lower were accepted. According to the Central Bank of Iceland press release a “total of 1,646 offers were submitted and 1,619 accepted; however, these figures could be subject to change upon final settlement. The amount of the accepted offers totalled just over 72 b.kr., out of nearly 178 b.kr. offered for sale in the auction.” – The on-shore rate is ISK139 to the euro. The question is how credible this outcome is, given the good economic conditions in Iceland. (Further to the background see an earlier Icelog here).

Although the auction apparently was a final offer the CBI is now offering to “purchase offshore króna assets not sold in the auction at the auction exchange rate of 190 kr. per euro.” The terms and conditions will be published tomorrow with the deadline at 10 o’clock this coming Monday morning, 27 June. The finale outcome of the 16 June auction and potential transactions in the following days, until Monday morning, will be published that Monday with settlement of both transactions completed on that day.

This outcome is far from the stock of ISK319bn that the offshore króna amounts to. The auction was supposed to be the last in a series of 23 auctions; this offer to buy offshore króna at the auction price of ISK190 is now a tail to that last auction.

In an interview on Rúv tonight, CBI governor Már Guðmundsson said that out of 1,646 offers submitted 1,619 had been accepted, or 98%. This means there are now a whole lot fewer offshore króna holders left – but the problem is, as Guðmundsson rightly acknowledges, that all the big funds holding these assets are holding on to their króna. “It is clear that the rather big holders have either not participated or offered a rate we could not accept,” said Guðmundsson.

In a cage – at the back of the queue

The governor said that with the auction out of the way, capital controls can now be lifted on domestic entities and individuals, i.e. Icelandic companies, pension funds etc. The process has been designed in such a way, according to Guðmundsson “that those who do not leave now stay in a similar financial environment as they have been in so far as to investment offers with added changes, which were necessary to secure that this environment would be stable even if we lift controls on domestic entities. They (i.e. the offshore króna holders) will now go to the back of the queue, they were at the front and then at some point it will again be their turn.”

This is undoubtedly a description the big offshore króna holders will contest. They will claim that conditions have been seriously tightened. When their assets mature these assets will automatically go into deposits at 0.5% interest rates, effectively negative interest rates, held with the CBI, very much akin to the cage that Guðmundsson once described so vividly at a meeting in Iceland.*

Thus the big offshore króna holders, who did not participate (or offered a non-accepted rate) will now feel they are in a cage at the back of a queue not knowing when they will be released. Or in other words: they will claim that the sovereign isn’t paying back its loans.

Calling things their right names

What is it called if a country pays only some of its debt? The term is “selective default” – and worryingly that’s now the term attached to Iceland if offshore króna holders, where Icelandic sovereign bonds and T-bills are the underlying assets, are not paid out in full.

Offering a rate of ISK190 to a euro when the on-shore rate is ISK139 in a country doing pretty well seems like a drastic haircut – and it is incidentally involuntary, from the point of view of the offshore króna holders, although the Icelandic government claims there was a fair second offer, i.e. the cage at the end of the queue.

In a defiant answer to a WSJ op ed, minister of finance Bjarni Benediktsson rejects that Iceland can be compared to Argentina. However, he fails to point out that after fighting creditors for fifteen years Argentina did indeed finally settle with creditors. A country can claim as much as it wants that it’s honouring all its obligation but the arbiter is not the country itself but the International Swaps and Derivatives Association, ISDA, which decides on which events release credit default swaps.

Reputation risk

I have earlier talked about the mixed messages from Iceland in dealing with creditors. Last year, great care was taken in negotiating with creditors when it came to lifting capital controls on the estates of the three collapsed banks.

This time, when the sovereign is directly involved, contrary to last year, the strategy is to offer a cage at the back of a queue with no date as to when that backend will be served. There must be a strategy somewhere but I can’t see it, which is worrying since the outcome could be lengthy court cases in all and sunder jurisdictions for years to come. In the world of short-term politics that would inevitably be a problem for another day and another government.

In the meantime, the financing cost of all things Icelandic, whether state or private sector, will either go up or stay as it is, instead of going down as it well could soon with the bright economic prospects there are (and as Moody’s had already beckoned). This was kept in mind last year. Now it seems that this past of playing carefully was not a prologue to the present but an aberration. Consequently, Iceland might be back to a costly future of reputation risk.

*At a public meeting on the offshore ISK in 2013, some of those present argued that the solution to the Icelandic current account problem was just to cage in the foreign-owned assets so capital controls could be lifted on the domestic part of the economy. Present at the meeting was CBI governor Már Guðmundsson who pointed that when new investors would then arrive in Iceland they would see the cage and ask who was in it. “The investors who invested in Iceland last time around.” (From an earlier Icelog).

Update: This morning, Wed. 22 June, minister of finance Benediktsson talked at Euromoney Global Borrowers and Investors Forum where I interviewed him afterwards; Benediktsson claimed the offshore króna auction had been a success in terms of the many bids received and now those remaining would have to wait. He said there had been no legal aftermath following the composition of the estates last year, precisely because it had been well prepared but said he was not worried this time. It was to be expected that the hedge funds holding offshore króna were making a noise but that was nothing the minister was worried about.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Mixed messages from Iceland

While the Icelandic government is planning to play clever and give offshore króna holders, i.e. sovereign bondholders, a haircut – apparently because the Icelandic economy isn’t strong enough – Kaupthing, the largest owner of Arion bank , and that bank are assessing how to make use of the strong Icelandic economy with regards to Kaupthing’s shares in Arion. An intriguing case of “mixed messages”… now that another step is being taken to further ease the capital controls, in place since November 2008.

In the past few days, two articles have appeared – an op ed in Wall Street Journal and a guest blog on FT Alphaville – spelling out that Iceland is about to opt for a sovereign default, quite voluntarily and apparently with open eyes.

Iceland, of course, doesn’t quite see it that way, as I explained recently at some length. That said, I have been utterly baffled why Iceland, having taken such care last year to avoid all legal risk by negotiating with the creditors of the three fallen banks, is now reverting to the tactic, which at the time of the collapsing banks in October 2008 was half (but not quite) jestingly called “xxck the foreigners.”

Last year, some foreign pundits were comparing Iceland’s situation with Argentina, a wholly misplaced comparison since the government was no partner to the composition of the estates of the banks though the government had to take on the role of a facilitator in solving problems related to the foreign-owned, i.e. offshore ISK assets of the estates.

The outcome was around 75% haircut of the Icelandic assets. So successful was this step towards easing capital controls that foreign inflows into sovereign bonds started at once, now amounting to around 5% of GDP – nothing compared to the 44% of GDP in November 2008 when the capital controls were put in place, under the auspice of the International Monetary Fund.

This time the government IS the other party since the offshore ISK assets are sovereign securities, which led James Glassman in the WSJ and then Arturo Porzecanski* in FT Alphaville to compare Iceland to Argentina: Iceland was about to turn into a very chilly version of Argentina.

Actually, after years of legal wrangling Argentina has of course finally settled with creditors, advised by the law firm Cleary Gottlieb, also advising Iceland (though somewhat ominously Cleary was the adviser not only in solving the Argentinian problem but also during the dark years); Argentina is now happily borrowing again. Financial firms have a notoriously short memory, after all they can’t afford to hold grudges. But the legal wrangling all over the world did blight the lives of Argentinians for around 15 years and no need to minimise how unpleasant and costly it all was.

The Icelandic situation right now is that tomorrow, on June 16, the Central Bank of Iceland will hold an auction for OS ISK holders (all info here). After setting the terms in such a way that a hair cut was all but inevitable for those participating in the auction and negative interest rates for those who didn’t the terms were changed this week – last minute wisdom… or panic, depending on the reader:

The amendments to the Terms of Auction removes ambiguity about whether, in spite of the auction results, the Bank can decide on a more favourable auction price than is specified in the table. As before, all owners of offshore krónur will receive the same price for their krónur, as the auction has a single-price format, which applies irrespective of whether the price accepted is lower than is specified in the table. It is appropriate to reiterate that as before, the Central Bank reserves the right to accept some or all of the offers submitted, or to reject all of them (emphasis mine).

Effectively, the CBI can now choose to accept the best offer… or well, come up with a better one.

Two questions: why this sudden and very late change and why was such care taken last year to negotiate whereas now it’s a take it or leave it offer?

As to the sudden change I don’t know but given the fact that a high participation is needed to solve the issue – or otherwise the OS ISK will be locked up in a really cold dungeon, i.e. at negative interest rates with no maturity in sight but only some vague words of a revision when suitable – it can be surmised that the CBI sensed that the large OS ISK holders were not going to participate: they have indicated as much. Although the auction is set for June 16 this isn’t the kind of auction where bidders walk in from the street and wave their hands; the bids will have been placed earlier due to time-consuming procedures.

On the different approach last year v now I had already made some guesses in my last blog: whetted appetite for collecting more for the state coffers, following last year’s windfall from the estates’ ISK assets; political need for a victory before the planned election in October (no date set yet); the certainty that OS ISK owners can’t rely on Icelandic courts to rule in their favour against the sovereign; using the harsh terms as a stick to beat the ISK holders (but when?) – I don’t find any of these very plausible, partly because I don’t see any of these reasons as a winning strategy.

One lesson from the Argentina very very long struggle is that international creditors rely on a many-pronged strategy, i.a. legal actions not only in the home country of the bond issuer but in many jurisdictions. I refuse to believe that Icelandic courts would side with the sovereign against the law but ultimately that’s not a deciding point since legal action will, most likely, be taken in many jurisdictions. And it’s not up to Iceland to define if a certain action is a default event or not.

The fact that two non-journalistic articles have already been published in international finance media indicates interest in certain quarters and a preparation, meaning that the large OS ISK holders, quite unsurprisingly, already have their plan A B and C mapped.

Considering the strong Icelandic economy Iceland has in general a weak case for forcing a haircut on holders of Icelandic sovereign bonds. The government can certainly hold its course but testing its limits to such a degree that it loses control of the situation – as it would i.a. if legal action were taken against it – shows at best lack of realism and worst a staggering stupidity.

That brings me to the same question as earlier: after the care taken last year to avoid time consuming action and legal risk why is the government and the CBI now opting for a course that involves all the things religiously avoided last year?

*In his blog Porzecanski is dismayed that the CBI and the government have recently passed a Bill to temper inflows. This action does however not come as any surprise. Already in its 2012 outline of prudence rules following the lifting of capital controls the CBI spelled out various measures which would be used in the future to secure financial stability. Considering the fact that the inflows in the years up to 2008 ultimately caused Iceland to opt for the capital controls, now being eased, this prudence is highly sensible, in my opinion. Yes, interest rates could be lowered in order to temper the appetite of international investors but that’s another thought for another day. In short, I definitely don’t share Porzecanski’s view though I can see his point. There is an Icelandic saying that a burnt child stays away from the fire – and that is, I’m sorry to say, an apt description of the mood in Iceland re foreign inflows.