Search Results

The Lopapeysa is not enough – Huang Nubo has no convincing foreign enterprises to show

In a document, seen by Icelog, sent to the Icelandic Government to underpin his project of investing up to $200m to build a highland resort at Grimsstadir in Iceland, the Chinese entrepreneur Huang Nubo mentions his first ties to Iceland: as a student he became friends with an Icelander and so warm was the friendship that the mother of his Icelandic friend knitted a lopapeysa (a typical Icelandic sweater, made from Icelandic wool in natural colours). This friend, Hjorleifur Sveinbjornsson, later married Ingibjorg Solrun Gisladottir, the leader of the social democrats 2005-2009 and minister of foreign affairs 2007-2009 – and Sveinbjornsson has been one of Huang’s ardent advocates in Iceland.

Huang Nubo is now mightily upset with the Icelandic government for not embracing his plans. According to the FT (subscription only), Huang sees this as a racial discrimination. “I think this is racial discrimination because I am Chinese,” he told the FT. “Many people have invested in Iceland in the past but no one has been treated like I have.”

This isn’t entirely true. There are serious restrictions to foreign investment in Iceland, especially when it comes to investment from outside the EU/EEA. Icelanders tend to be suspicious towards foreign investment. Ia a Canadian company, investing in energy in Iceland, at the time called Magma, now called something else, ran into similar problems, as explained earlier on Icelog. Magma found a way around this by setting up a company in Sweden. This caused hefty debate in Iceland, the investment was accepted – incidentally, this investor seems to have lost interest in Iceland, as sometimes happens.

The serious problem with Huang as an international investor is that he has nothing to show outside of China. The properties and companies he owns in the US are nothing to speak of, in terms of operations and having done something substantial. When he seemed to be losing the bid to invest in Iceland he turned his attention to Denmark, was interviewed there but again, just words and nothing seems to be moving there.

Another problem is the inconsistency in his intentions, which he has aired. He said he would fund it all himself, out of his own pocket and that wouldn’t be a problem. One day, he announced he would fund the Grimstadir operations by selling 100 Grimsstadir luxury dwellings to rich Chinese. It seemed to have escaped his attention that due to restrictions on nonEU/EEA owning property in Iceland this plan would make things very complicated. When I inquired about this with his Huang’s spokesman in Iceland this seemed just one idea out of many.

And this seems to have been a problem all along. There were many ideas and not concrete plans. So far, no independent due diligence has been done by Icelandic public sector entities, negotiating with Huang. All the information worked on comes from Huang himself. In that sense, these entities have not done a convincing job in securing public interest at stake here.

Huang Nubo makes much of the fact that he is a poet. Unfortunately, when it comes to business poetic visions aren’t substantial enough to bank on.

*A link to earlier Icelogs on Huang.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

The cartoon news version of the Huang Nubo story (updated)

NMA tv is a *Chinese website that specialises in cartoon versions of news stories. They have their own cartoon take on the Huang Nubo story that you can watch here.

*As pointed out in the comments, NMA is Taiwanese, not Chinese – and that adds a twist to this story. Thanks for the comment.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

A ministerial ‘no’ to Huang Nubo

Minister of Interior Ogmundur Jonasson has refused the Chinese enrepreneur Huang Nubo the right to buy the big plot of land, Grimstadir a Fjollum, that he had his eyes on. As reported on Icelog earlier, the sale was a hot topic in Iceland.

Jonasson, from the Left Green party, seems to have angered his coalition partner, the social democrats. Minister of Economy and Trade Arni Pall Arnason said this weekend that this was a test for the coalition. Other leading social democrats have also expressed anger and irritation. Jonasson has already expressed his doubts. The answer hardly comes as a great surprise.

Nubo’s Icelandic plans have attracted great attention in the international media, ia the FT which yesterday had the latest development in the Nubo case on its front page, as has been the case with the paper’s earlier reporting. This interest indicates the focus not only on Iceland but on Chinese ventures abroad.

In my Ruv reporting I have pointed out that Nubo, though portrayed as one of China’s dollar billionaires, has no business ventures outside of China that indicate his ability to develop the huge tourism plans he seemed to have in mind for Grimstadir. His main foreign ventures are in the US where he ia owns a plot of land, plans to build a shopping mall, but hasn’t had the money, because of the crisis, to commence. He is also developing tourist fascilities at a ranch in Nashville. Due to opacity in the Chinese business environment, Nubo’s ventures are yet another example of how difficult it is to ascertain the real standing of Chinese companies.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

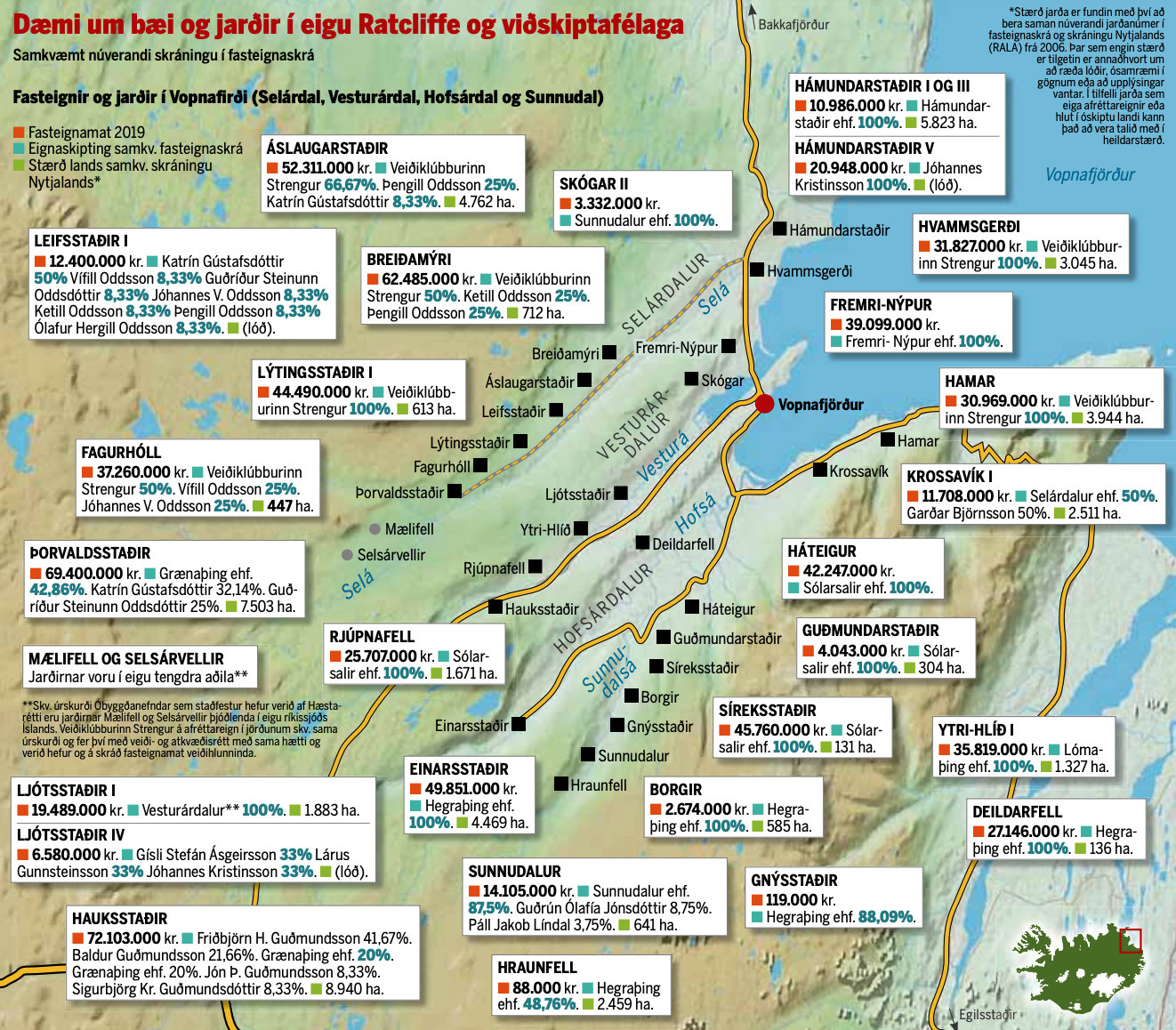

Jim Ratcliffe and his feudal hold of Icelandic salmon rivers and farming communities

The largest landowner in Iceland owns around 1% of Iceland, mostly land adjacent to salmon rivers in the North East of Iceland – and he is not Icelandic but one of the wealthiest Brits, James or Jim Ratcliffe, a Sir since last year, of Ineos fame. His secretive acquisitions of farms with angling rights have been facilitated by the Icelandic businessmen who for years have been investing in salmon rivers through offshore companies. Opaque ownership is nothing new. Though the novelty is the grip on these rivers now held by a foreigner, with no ties to the community and assets valued at just above the Icelandic GDP, the central problem is mainly the nationality of the owner, but the concentration of ownership.

“If you are doing honest business, I assume you would feel better if you could talk freely about it. This secrecy breeds suspicion,” says Ævar Rafn Marinósson, a farmer at Tungusel in North East Iceland. The secretive business he is talking about is the business of buying farms adjacent to salmon rivers in his part of Iceland.

The secrecy is not new: for more than a decade, the ownership of the attractive salmon rivers in Iceland has been hidden in an opaque web of on- and offshore companies. That opacity might now hit the community when rivers and land is increasingly being held by one man, Jim Ratcliffe, whose assets are estimated £18.15bn. Through direct and indirect ownership, Ratcliffe owns over forty Icelandic farms concentrated in and around Vopnafjörður, which gives him the control of angling rights in some of the best salmon rivers in Iceland.

The petrochemical giant Ineos is Ratcliffe’s source of wealth. Interestingly, his salmon investments are part of his recent, rapidly growing investment in sport, from cycling, sailing and football to his, so far, tentative interest in British Premier League football clubs with price tags of billions. Ratcliffe claims that his petrochemical industries are run in an environmentally friendly way and strongly denies that his sport investments are any form of green-washing.

The secrecy surrounding Ratcliffe’s Icelandic investments, so out of proportions in this rural community of salmon and sheep farmers, has bred both rumours and suspicion that splits apart families, neighbours and the local communities as they debate whether the funds on offer are a substitute for losing control of the angling and the land.

Also, because Ratcliffe is a distant owner. He leaves it to his Icelandic representatives to talk to the farmers some of whom, like Marinósson, refuse to sell and as a consequence feel harassed. And then there are the pertinent questions of how Ratcliffe’s funds flow into the local economy, as one farmer opposed to Ratcliffe’s growing hold of the region, mentioned in an interview in the Icelandic media.

Following Ratcliffe’s purchases, foreign ownership of land is now a hot topic in Iceland. The government is looking at legal restrictions to limit foreign ownership. A new poll shows that 83.6% of Icelanders support this step. – But that might be a mistaken angle: the problem is not foreign ownership but concentrated ownership.

“I’m not upset with Ratcliffe, he’s just a businessman pursuing his interests. I’m upset with the government of Iceland that is letting this happen,” says Marinósson. He is not the only one to point out that a new legislation might come too late for the salmon rivers in the North East.

Angling – strictly regulated

Though far from being a mass industry, angling has long been both a beloved sport in Iceland and attracted wealthy foreigners. In the early and mid 20th century, English aristocrats came to fish in Iceland. In the 1970s and 1980s, the Prince of Wales was fishing in Hofsá, now controlled by Ratcliffe. With the changing pattern of wealth came high-flyers from the international business world.

As angling interest grew, net fishing for salmon was restricted so as to let the angling flourish. In 2011, 90% of the salmon caught in Iceland was from angling. The annual average salmon catch is around 36.000 salmon, with the figures jumping over 80.000 in the best years. There are in total 62 salmon rivers with 354 rods allowed; the rivers in the North East are thirty, with 124 rods (2011 brochure in English; Directorate of Fisheries).

According to the Salmon and Trout Act from 2006, the fishing rights are privately owned by those who own the land adjacent to rivers and lakes. The fishing rights come with a string of obligations, supervised by the Directorate of Fisheries and most importantly: the fishing rights cannot be split from the land – the only way to control the angling is to own a farm or farms holding the angling right.

The owners of the farms owning a river or lake are obliged to set up a fishing association to manage the angling; both the necessary investment and the profit has to be shared according to the amount of land owned. The ownership is split according to voting rights and percentage owned.

Wielding control over the angling, these associations can decide either to manage the angling themselves or lease out the rights to angling clubs or other consortia.

From overfishing to highly regulated angling regime

Already in the 1970s, the fishing associations run by the farmers owning the best salmon rivers were increasingly leasing out the angling rights to groups of wealthy Icelandic anglers, mostly business men from Reykjavík.

In some rare cases, foreign anglers who frequented Iceland, held the angling rights through a lease. One attractive salmon river in the North East, Hafralónsá, where Ævar Rafn Marinósson and his family are among the owners, was leased by a Swiss angler from 1983 to 1994; from 1995 to 2003, a British and a French angler leased the river.

During the 1990s, the popularity of angling led to overfishing in many salmon rivers with tension between biology and the financial profits from the angling rights. But the owners of the angling rights quickly came to understand that overfishing would kill the goose laying the golden eggs, or rather the salmon that brought wealth to the community.

The angling is now restricted in many ways: each river has only a certain number of rods; the angling time is restricted to certain hours of the day and a certain amount of annual angling days, often 90 days, from mid-June.

In addition, some form of “fish and release” is in place in most if not all the highly sought after and expensive salmon rivers. All these protective measures have been driven by those who control the angling, i.e. the fishing associations owned by the landowners.

Foreign anglers mainly pursue the sporty fly-fishing, whereas Icelanders tend not to frown upon using spoons and worms. Icelandic anglers know it is good to fish with spoons and worms after the foreign fly-anglers have been “beating the river” as we say in Icelandic. That normally ensures great catch, a trick the Icelandic anglers are happy to use.

Angling – from farmers to wealthy business men

The leases related to the salmon rivers normally run for some years. The fees to the fishing associations are a significant part of income for the farmers. The lessees are normally obliged to undertake investment in the infrastructure around the river.

Part of cultivating the salmon population in the rivers is expanding the habitat. This is for example done by building “salmon-ladders,” enabling the salmon to migrate beyond waterfalls or other hindrances, potentially increasing the rods allowed in each river and thus making the river more profitable.

Those who rent the rivers try to sell each rod at as high a price as the market can tolerate. Angling in the best rivers in Iceland is an expensive sport, also because the fishing is sold as a package with accommodation and meals included.

No longer primitive huts, the best fishing lodges are like boutique hotels, where the best chefs in Iceland come and cook for discerning anglers with the wines to match. Part of the summer news in the Icelandic media is reporting on the number of salmon caught in the well-known rivers, size and weight, what tools were used and sometimes also who is angling where.

This is the angling of the very wealthy. But angling is also popular with thousands of ordinary Icelanders. Angling for salmon, trout and sea trout in less famous rivers and lakes, is an affordable and ubiquitous sport in Iceland.

The opaque ownership web that Ratcliffe is buying into

Incidentally, this development of buying farms, not just licensing the angling rights, has been going on in Iceland for decades. In the early 1970s, a medical doctor and keen angler in Reykjavík, Oddur Ólafsson, bought five farms along Selá. Decades and several owners later these farms are now owned by Ratcliffe.

Orri Vigfússon (1942-2017) was a businessman and passionate angler, who in 1990 set up the North Atlantic Salmon Fund as an international initiative in order to protect and support the wild North Atlantic salmon. Vigfússon was influential in Icelandic angling circles and well known in angling circles all around the North Atlantic. He was also primus motor in Strengur, a company that for decades has controlled the best rivers in the North East, now controlled by Ratcliffe.

The web of on- and offshore companies related to angling has been in the making in Iceland since the late 1990s, when the general offshorisation of wealthy Icelanders boomed through the foreign operations of the Icelandic banks. A key person in this web is an Icelandic businessman.

Born in 1949, Jóhannes Kristinsson has been living in Luxembourg for years. Media-shy in Iceland he was in business with flashy businessmen like the duo Pálmi Haraldsson and Jón Ásgeir Jóhannesson of Baugur fame, synonymous with the Icelandic boom before the 2008. Kristinsson seems to be linked to around 25 Icelandic companies.

By 2006, it was attracting media attention in Iceland that wealthy anglers were no longer just licencing the angling rights but were outright buying farms holding angling rights. One name figured more often than others, Jóhannes Kristinsson. In an interview at the time, Kristinsson said he probably owned only one farm outright but was mostly a co-owner with others, without wanting to divulge how much he owned.

The farmers felt they knew Kristinsson, a frequent guest in the North East and the opaque ownership did not seem much of an issue. However, the effect of the opacity is now becoming very clear as Kristinsson is selling to a foreigner with no ties to the community, leaving the community potentially little or no control over some of its glorious rivers and land.

Luxembourg, Ginns and Reid

Kristinsson’s ownership of lands and rivers in the North East seems to have been held in Luxembourg from early on. Dylan Holding is a Luxembourg company, registered in 2000, by BVI companies, which Kaupthing owned and used to offshorise its clients. No beneficial owner is named in any of the publicly available Dylan Holding documents but the company was set up with Icelandic króna, indicating its Icelandic ownership.

According to Dylan Holding’s 2018 annual accounts, the company, still filing accounts in Icelandic króna, held assets worth ISK2.6bn. Its 2017 accounts list eleven Icelandic holding companies, fully or majority-owned by Dylan Holding, among them Grænaþing. Last year, Ratcliffe bought Grænaþing, as part of the deal with Kristinsson; an indication of Kristinsson being the beneficial owner of Dylan Holding.

The names of two of Ratcliffe’s trusted Ineos lieutenant, Jonathan F Ginns and William Reid, are closely linked to Ratcliffe’s Icelandic ventures as to so many other Ratcliffe ventures. According to UK Companies House, Ginns sits or has been on the board of over seventy Ineos/Ratcliffe related companies, Reid on seven.

Ginns and Reid sit on the boards of three Icelandic companies previously owned by Dylan Holding indicating that these companies are now under Ratcliffe’s control. Whether Ratcliffe has bought Dylan Holding outright or where exactly his ownership stands at, remains to be seen but it seems safe to conclude that Ratcliffe now owns significantly more land on his own rather than, as earlier, through joint venture with Kristinsson and others. Kristinsson seems to be withdrawing, leaving Ratcliffe as the sole owner.

Ratcliffe’s rapid rise to being Iceland’s largest landowner

Jim Ratcliffe, the angler with the funds to indulge his salmon passion was nr.3 on the Sunday Times Rich List this year, with assets valued at £18.15bn, down from £20.05bn in 2018, when he ranked nr.1. A Brexiteer who is not waiting for Brexit to happen: after relocating to the UK from Switzerland, where Ratcliffe and Ineos were domiciled from 2010 until some months after the EU referendum in 2016, Ratcliffe moved to Monaco last year. Tax and regulation seem to be his main concerns.

Ratcliffe had been fishing in Vopnafjörður for some years without attracting any attention. It was not until late 2016, when he visibly started buying into the Icelandic angling consortia, that his name first appeared in the Icelandic media. By then, he already owned eleven farms in the area, both through sole ownership and through his share in Strengur. Local sources believe Ratcliffe started investing earlier in angling assets, hidden in opaque ownership structures.

In December 2016 it was announced that Ratcliffe had bought the major part of the single largest farmland in Iceland, Grímsstaðir. This mostly barren wasteland of glorious beauty in the highlands beyond Mývatn had been owned by Grímstaðir farmers and their families for generations. The Icelandic state was a minority owner and has retained its share of the land. Ratcliffe stated at the time he was buying Grímsstaðir because it was part of the Selá water system; buying the land was part of his plan to support and protect the wild salmon.

The Grímsstaðir deal drew a lot of media attention in Iceland because in 2011, a Chinese businessman and poet, Huang Nubo, had tried to purchase this land with unclear intentions. Nubo had some Icelandic friends from his university years but practically no assets abroad except some real estate in the US, which he seemed to struggle to maintain. In 2014, the Icelandic government vetoed Nubo’s plans: he was not European, and his plans lacked clarity.

For decades, Strengur, under changing ownership, has managed the angling rights in Selá and Hofsá, two of the best salmon rivers in the North East and bought up farms adjacent to the rivers. In 2012, a new 960sq.m fishing lodge opened by Selá, a good example of the investment done in order to improve the angling experience and cater to wealthy anglers.

Following a 2018 transaction Ratcliffe owns almost 87% of Strengur, a jump from the 34% he had owned earlier, meaning that he controls the angling rights in both Selá and Hofsá. Ratcliffe bought the 52.75% by purchasing a company owned by Jóhannes Kristinsson. Strengur’s director Gísli Ásgeirsson (who features in this Ineos PR video) is now seen as Ratcliffe’s mouthpiece. He has ties to around twenty Icelandc companies, many of which are linked to Kristinsson.

The Ratcliffe Kristinsson consortium now owns 40 to 50 farms. But Ratcliffe is looking for more: earlier this year, Ratcliffe added one farm to his Icelandic portfolio. He now seems trying to secure ownership of yet another river, Hafralónsá.

The Icelandic media had reported that he had now secured majority in the angling association of that river but that does not seem to be the case. Ævar Rafn Marinósson is one of the owners of Hafralónssá. He says to Icelog that as far as he knows, Ratcliffe is still a minority owner.

The suspicion among those who are not in Ratcliffe’s fold is rife as a change in ownership might bring about drastic changes. With majority hold, Ratcliffe might for example drive the farmers in minority to bankruptcy by forcing through investments in the Hafralónsá angling association, which would wipe out the profits that make an important part of the farmers’ annual income.

Ratcliffe’s representative made Marinósson an offer to buy his farm. His answer was that the farm, which he owns with his parents, was not for sale. The representative then visited his elderly parents with the same offer, although it had been made clear to him that the farm was not for sale.

Misinformed passion

In a PR video from Ineos, Jim Ratcliffe talks of “overfishing and ignorance” that threat the salmon populations in Iceland. In the video Ratcliffe’s passion for salmon fishing is given as his drive for investing “heavily in the region to help expand the salmon’s natural breeding grounds” through constructing of salmon ladders in six rivers. The latter part of the video is about his investment in safari parks in Africa, with both initiatives presented as rising from Ratcliffe’s environmental concerns.

As mentioned earlier, the times of overfishing in Icelandic salmon rivers are long over. To portray Ratcliffe as a saviour of the salmon rivers in the North East is at best misinformed, at worst profoundly patronising to the farmers who have lived and bred salmon all their live and whose livelihoods have partly depended on the silvery fish. But the fact that Ratcliffe has the funds to follow his passion cannot be disputed.

In August this year Ineos Technology Director Peter S. Williams signed an agreement on behalf of Ratcliffe with the Marine and Fresh Water Institute in Iceland, where Ratcliffe takes on to fund salmon research to the amount of ISK80m, around £525.000. At the time it was announced that any profit from Strengur will be ploughed into maintaining and supporting the salmon populations in the rivers that Strengur controls. Strengur’s director Gísli Ásgeirsson said at the time that the aim was sustainability in cooperation with the farmers and local councils. There will be those in the local community who feel that cooperation is exactly what is lacking.

In a Rúv tv interview I did with Ratcliffe in 2017 (unfortunately no longer available online), Ratcliffe said he was driven by his passion for angling and the uniqueness of the unspoiled nature in Iceland, a value in itself. There is some speculation in Iceland that Ratcliffe’s angling investments might be driven by something else then his passion for angling.

Some think water as commodity in a world facing water shortage is his real interest, which would explain his emphasis on buying the rivers outright instead of joint venture or just renting the angling rights. Others, that plans by Bremenport to build a port in nearby Finnafjörður in order to service the coming Transpolar Sea Route might be in Ineos’ interest. Again, total speculation but heard in Iceland. – Ineos is investing in facilities in Willhelmshaven, where Bremenport is building a new container terminal.

Mushrooming sport investment: from millions in salmon and safari to, possibly, billions in Premier League football

Ratcliffe’s UK holding company for his Icelandic assets is Halicilla Ltd, incorporated in 2015, its business being “mixed farming.” Halicilla’s 2017 accounts list two Icelandic companies as assets, Fálkaþing, incorporated in 2013 and Grenisalir, incorporated in 2016, “Icelandic companies, which in turn hold land and fishing rights.”

Ratcliffe has been unwilling to divulge how much he has invested in Iceland but that can be gleaned with some certainty from the Halicilla accounts: its assets amounted to £9.7m in 2016, which with further acquisitions in 2017, had grown to £15.3m by the end of 2017, financed directly by the shareholder, i.e. Ratcliffe.

In addition to investments in Icelandic salmon rivers, Ratcliffe’s sports investments have mushroomed in the recent years. In December 2017, he announced his investment in luxury eco-tourism project in safari parks in Tanzania through a UK company, Falkar Ltd, incorporated in 2015. As Halicilla, Falkar is financed by Ratcliffe, with a loan of £6.3m, at the end of 2017. With his interest in sailing, Ratcliffe owns two yachts, one of them, Hampshire II a superyacht worth $150m, with two of his Ineos partners owning three yacths. In addition, Ratcliffe owns four jets, three Gulfstream jets and one Dassault Falcon.

Ratcliffe’s other sport investments involve much higher figures than his investments in salmon and safari. Last year, he invested £110m in Britain’s America’s Cup team. His investment in March in the cycling Team Sky, now Team Ineos, seemed to imply that the Team’s earlier budget of £34m would increase significantly. In 2017 he bought the Lausanne-Sport football club, where his brother is now the club’s president, and has recently completed a £88.7m deal to buy Ligue 1 club Nice.

The figures might rise: last year, Ratcliffe led an unsuccessful bid of £2bn for Chelsea FC and has aired his interest to buy his favourite team, Manchester United – one day, some super-star footballers might be practicing fly-fishing under Ratcliffe’s instructions in Vopnafjörður.

Split families and farming communities, threats and bullying

The farmers in the North East face a dilemma. It is in the interest of farmers to be able to sell their farm for a reasonable price if they intend to retire or give up farming for other reasons. However, seeing whole fjords and entire rivers now owned not by a consortium of wealthy anglers in Reykjavík but by a single foreigner, wholly unrelated to the country and the North East, with a strangle hold on the community, has spread unease.

When the Icelandic consortia started buying farms in order to gain control of the angling, the farmers often continued to live on the farm, as tenants. On the whole, the farms have continued to be farmed, though there are exceptions.

Ratcliffe has stated he is keen for the farmers to keep living on the farms and has offered them to stay as tenants. With money in the bank the tenants can profit from the land as earlier but no longer benefit from the angling rights as earlier or have any say on the use of the river.

Ratcliffe’s acquisitions have completely changed the game around the rivers. The novelty is his immense buying power. His entrance into the angling circles has split families and communities. To sell or not to sell is a burning question for many since Ratcliffe’s representatives keep making lucrative offers to the few farmers who have so far been unwilling to sell.

This is, as such, not entirely Ratcliffe’s fault – he simply has an exorbitant amount of money to indulge in one of his hobbies though he has shown little interest in learning from the farmers who know the rivers like the back of their hands. But this sowing of anger and unease has been the side effect of his investments. Perhaps also to some degree because of the people he has chosen to work with in Iceland; how well informed Ratcliffe is of the circumstances surrounding his investments is unclear.

Ratcliffe flies in and out of Iceland. The Icelanders who work for him are there and some live in the communities Ratcliffe has already bought or is trying to buy. His salmon shopping spree may be backed by the best intensions, but the side effect is effectively making him the ruler of a few hundred Icelanders who live off the land they love dearly. The land, which Ratcliffe visits at his leisure, once in a while.

Restrictions on ownership of land may come too late for the North East

Foreign ownership is a hot topic in Iceland for the time being, given the quick and enormous concentration of Ratcliffe’s ownership in the North East. But it would be wrong to focus on foreign ownership – the real problem is concentrated ownership.

Ratcliffe is not the only foreign landowner in Iceland. There are a few others but there is increased interest from abroad for land in Iceland. One foreign owner closed off his land with signs of “Private road,” much to the irritation of his Icelandic neighbours since free passage in the country side is seen as a general right in Iceland. One practical reason is the gathering of sheep: sheep roam freely in summer and farmers need to roam just as freely when the sheep is gathered in autumn.

Though rapidly developing, luxury tourism is still a rarity in Iceland, and has so far not led to land being closed off. As Ratcliffe’s Tanzania investment shows, he is interested in luxury tourism. Seeing angling turning into an even more rarefied luxury than it already is, marketed mainly for people in Ratcliffe’s wealth bracket, is not an enticing thought for most Icelanders.

The government led by Katrín Jakobsdóttir, leader of the Left Green party (Vinstri Grænir), with the Independence party (Sjálfstæðisflokkur) and the Progressives (Framsóknarflokkur), is now under pressure to consider means to limit foreign ownership. A working group has been gathering material and new law is promised this coming winter. One step in the right direction of focusing on concentrated ownership, not just foreign ownership, would be to reintroduce pre-emptive purchase rights of local councils, abolished in 2004.

Finding the proper criteria that drive rural development in the right direction will not be easy. But Icelanders are certainly waiting for that to happen – having stratospherically wealthy people, Icelandic or foreign, owning entire rivers and fjords on a scale not seen since the time of the feudal lords of the Icelandic sagas is not seen as positive rural development. When law is finally passed, it might be too late to prevent that to happen in the North East.

*This image is from a July 21 July 2018 article on Ratcliffe’s acquisitions in the Icelandic daily Morgunblaðið and shows ownerships of farms in Vopnafjörður (there are other farms in the neighbouring communities.)

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

New Zealand worries over Chinese investment in dairy farms

Icelandic authorities recently vetoed the sale of land in the Icelandic inland to a Chinese billionair, Huang Nubo. That case is indeed still milling on. The latest is that the adjacent municipalities are exploring the possibility of buying the land, with a loan from Nubo, to rent it out to Nubo.

But it’s not only in Iceland that Chinese investment is met with some skepticism.

This week, the High Court in New Zealand halted a planned sale of dairy farms to Chinese investors. The reason for the ruling is that the High Court claims the New Zealand government overstated the economic benefits the Chinese investment would bring when it allowed the sale some 16 months ago. The ruling isn’t prohibiting the sale per se but puts onus on the government to review the evaluation with stricter criteria. The court case was brought by some Australian farmer and a banker who were outbid by the Chinese investor.

It’s all familiar to Icelanders: the supporters of the sale say it brings much needed foreign investment into the dairy sector that’s anything but prosperous. Those against it says it runs against Australian interests to sell farmland. Quite interestingly the buyer in spe is a company run by a property developer called Jiang Zhaobai. As in the case of Nubo’s company property in China is notoriously difficult to evaluate.

*Previous Icelogs on the Nubo sale are here and here.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Chinese interest in Iceland (updated)

The FT dedicates a front-page article today to a Chinese property billionaire, Huang Nubo, who wants to buy the largest single farmland in Iceland, Grimstadir, for a major development of all-year tourist facilities and a hotel. He is also planning to build a bigger hotel in Reykjavik, though he hasn’t yet secured property or land there. The two hotels will be linked by his own air company, another angle to this grande scheme. Nubo has offered 1bnISK (€6m) for the land, saying he plans to invest further 20-30bnISK (€120-180m) in the project.

Nubo’s Icelandic connections go back to his student years, when he had an Icelandic friend. He has lately cultivated his Icelandic connections and taken some Icelandic friends to the North Pole. One of his Icelandic friends is married to the former leader of the Social democrats, former minister of foreign affairs Ingibjorg Solrun Gisladottir. This friend of Nubo is also closely related to the present minister of foreign affairs Ossur Skarphedinsson.

Huang Nubo worked for the Chinese communist party, was an official until he emerged as the owner of Chinese properties in 2003. His company, Zhongkun Group, owns properties in China, resorts and tourist facilities. His company website indicates that most of this is still no further developed than to the computer picture stage.

Lately, his interests have been turned to the US but a planned project in Tennessee hasn’t materialised. Now he seems to have his attention turned to Northen Europe, Iceland first and foremost, inspired by his love of and interest in nature and poetry. One article states he has invested 1m yuan (€108,000) another mentions $1m in ‘China-Iceland Culture Fund,’ a noticeable sum in Icelandic culture life that has so far, as so many of Nubo’s other projects, has failed to reach the tangible state.*

He is also said to be one of the largest shareholders in Royal Business Bank, an American-Chinese bank, investing $1m. Unfortunately, the bank’s website gives no indication of who the shareholders are but this allegedly largest shareholder doesn’t sit on the board of the bank. The bank was set up in 2008 with a capital of $71m.

The leader of the Progressive party, Sigmundur David Gunnlaugsson whose constituency would benefit from the Chinese enterprise, has welcomed the investment, saying it really doesn’t matter if the investor is French, German or Chinese. Svandis Svavarsdottir environment minister says that big plans need to be carefully scrutinised. Prime minister Johanna Sigurdardottir says that investors like Huang Nubo is just what Iceland sorely needs. With strong regulations, that Iceland has, according to Sigurdardottir, there is nothing to afraid of.

This Chinese interest in Iceland is one of several Chinese projects under discussion in Iceland. China plans to build a huge embassy, indicating that its interest must be for something more than just normal diplomatic relationship. A Chinese research institution is exploring the viability of building an unmanned research station, in addition to its station in the Antarctica, to investigate the Northern lights. In addition, there is great interest in China for the sea route through the ice cap around the North pole.

Only foreigners from the EEA can buy land in Iceland, which means that this matter has to go through official channels in Iceland.

Icelandic politicians must now decide whether and to what extent Iceland should welcome Chinese investors. Investors from a country where no one is rich unless deemed worthy by the Chinese Communist Party and its officials. A country that is avidly seeking investments abroad though at the same time foreign investment in China is a tortuous process. That’s the fundamental difference between investors from, say EU countries, and from China. A difference much noted in Africa where Chinese investors have invested vast sums in land, mining and infrastructure.

In case, Icelandic politicians haven’t noticed, the questions asked everywhere in democratic countries is if politicians and business leaders are content with dancing to the Chinese flute or if they think pressure should be exerted on the Chinese to open China to foreign investments, ia. by improving fundamental rights such as human rights and rights of private property.

*This is wrong. The money has materialised, is held by a fund in China, which sponsored a poetry festival in Iceland last year. The next festival, now in autumn, will take place in China.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.