Search Results

Further to the Iceland Watch campaign

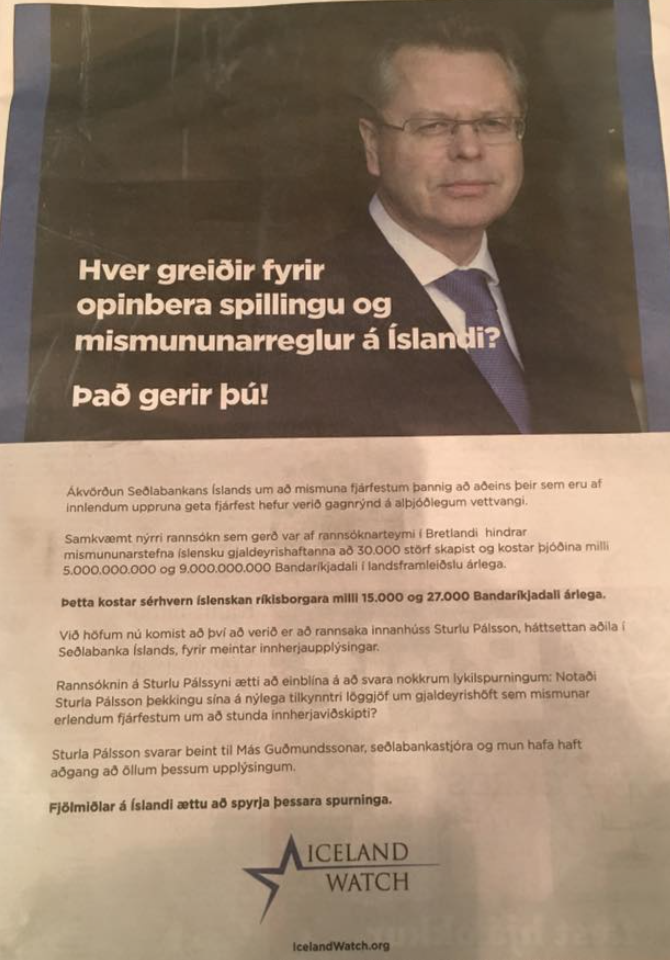

For the second day, the Iceland Watch, watching over the interest of the four largest offshore króna holders, has published an ad in Iceland warning Icelanders of corruption and claiming that an official at the Central Bank of Iceland is under investigation at the CBI for insider trading. The whole page ad is under a big portrait of the governor of the CBI Már Guðmundsson, see my yesterday blog.

This morning, the governor met with prime minister Sigurður Ingi Jóhannsson, Lilja Alfreðsdóttir minister of foreign affair and minister of finance Bjarni Benediktsson. After the meeting Guðmundsson said that no Icelandic action is being planned. He said the CBI was certain the measures taken regarding the offshore króna in order to protect the Icelandic economy were sound. “Of course there might be a reason to worry that people get the idea to put out statements like these but there is no reason to worry that any of the statements (in the ad) is based on fact because it isn’t,” Guðmundsson said to Rúv.

Negative response from the EFTA Surveillance Authority

The four funds holding offshore króna and contesting the measures taken earlier this year are Eaton Vance, Autonomy Capital, Loomis Sayles and Discovery Capital Management. This summer, two of the funds, Eaton Vance, brought the Icelandic offshore króna measures to the attention of the EFTA Surveillance Authority, ESA. Already in August ESA answered the complaint pointing out that it had already dealt with a number of complaints regarding the Icelandic capital controls.

The ESA conclusion was:

“It follows from the assessment set out above that an EEA State enjoys a wide margin of discretion as regards the adoption of protective measures as long as the (sic) comply with the substantive and procedural requirements of Articles 43(4) and 45 EEA. Once compliance with these requirements has been established, the exercise of the powers conferred on an EEA State pursuant to Article 43 EEA precludes the application of primary provisions in the sector concerned (such as Article 40 EEA).

Having taken account of the information on the facts of this case and the applicable EEA law, the Directorate cannot conclude that the Icelandic Government has erred in its application of Article 43 EEA.”

Eaton Vance was invited to submit its observations, which it did in September. ESA is now considering this last submission but given the earlier answer and previous ESA cases regarding the capital controls it now seems unlikely that Eaton Vance’s argument will win ESA over. That decision will then be final; there is no other instance to appeal to. So far, the EFTA Court has dismissed ruling on ESA decisions.

Who is behind the ads and the offshore króna holders?

Over the years, Icelanders have furiously speculated that there are large Icelandic stakeholders among the offshore króna holders. Nothing that I have seen or heard so far indicates that this is the case.

I’ve said earlier that there may well be Icelanders owning or having owned offshore króna but I find it highly unlikely that any of them hold large interests in the four main funds who own the largest part of the remaining funds, now ca. 10% of Icelandic GDP (see here for a recent overview of the capital controls and offshore króna from the CBI).

Funds as these four organise their investments normally in separate offshore funds as the maturity of underlying assets vary etc. Some of these funds may well have Icelandic names but I would imagine the names relate to the place of investment rather than the owners being Icelandic.

As I’ve pointed out earlier the funds have allied with Institute for Liberty, mostly dormant since it fought the Obama care some years ago and now revived with the offshore króna cause. The PR company DCI Group, based in Washington, is advising the funds. As far as I can see these are the entities driving the campaign against Iceland.

Baseless claims of Iceland in breach

The bombastic claims by Iceland Watch that Iceland is somehow breaching international rules and regulations have so far been shown to be baseless. As pointed out earlier, the International Monetary Fund has not criticised the measures taken in Iceland and these measures, as others, have been taken with the full knowledge of the IMF.

That said, the funds may well have success in litigating Icelandic authorities somewhere sometime but so far it seems the ESA challenge will not have a successful outcome for the four funds.

As to the ad campaign in Iceland it’s as ill advised and as unintelligent as can be.

Updated: I’ve been made aware that Loomis Sayles is not at all involved in the Iceland Watch campaign against Iceland. I’m sorry that my earlier information here was not correct.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

A weird ad in bad Icelandic against the Central Bank of Iceland

The libertarian Iceland Watch has posted quite a remarkable ad in Icelandic media insinuating serious corruption by a named individual at the Central Bank of Iceland with a large photo of the governor of the Central Bank Már Guðmundsson. If the four largest offshore króna holders, on whose behalf Iceland Watch seems to be campaigning, think they are winning friends in Iceland with these serious and unfounded insinuations, they should think again: the few who seem to notice it ridicule it or find it hugely upsetting.

Iceland Watch, earlier fighting Obama care and now fighting for the cause of the offshore króna holders that feel they have been wronged by the Icelandic government and the Central Bank of Iceland, CBI, has topped its earlier ads. It is now directly addressing Icelandic voters, claiming they are losing out due to the bad policies and corruption at the CBI. Whereas earlier ad was placed in media in Iceland, Denmark and the US, the latest one has, as far as I can see, only been posted in Iceland.

The four funds holding offshore króna are Eaton Vance, Autonomy Capital, Loomis Sayles and Discovery Capital Management.

So what is the Iceland Watch message, accompanied by a photo of CBI governor Már Guðmundsson, to Icelandic voters?

“Who is paying for public corruption and discriminating rules in Iceland? You do!

The decision taken by the Central Bank of Iceland to discriminate between investors so that only those of domestic origin can invest there has been criticised internationally.

According to a new study done by a research team in Britain the discriminatory policy of the Icelandic capital control hinders the creation of 30.000 new jobs and costs the nation between 5.000.000.000 and 9.000.000.000 US dollars in GDP annually.

This costs each Icelandic citizen between 15.000 and 27.000 US dollars annually.

We have now discovered that Sturla Pálsson, a highly placed individual at the Central Bank of Iceland, is being investigated in-house for alleged insider information.

The investigation of Sturla Pálsson should focus on answering some key questions: Did Sturla Pálsson use his knowledge of the recently announced legislation on capital control that discriminate foreign investors in carrying out insider trading?

Sturla Pálsson answers directly to governor Már Guðmundsson and is believed to have had access to all this information.

Media in Iceland should be asking these questions.

Capital controls and booming economy

Corruption is not an unknown theme in Icelandic politics but it will come as a surprise to most Icelanders that Icelandic officials are acting in a corrupt way to punish the four foreign funds holding offshore króna. We should keep in mind that the International Monetary Fund has followed and scrutinised policies in Iceland since October 2008.

The policy that’s such a thorn in the side of the four funds that they are willing to go to these lengths in advertising their pain internationally has also been passed with full acceptance of the IMF. Yes, the IMF isn’t infallible and perhaps the EFTA Surveillance Agency will indeed find Iceland at fault. But to think that the measures in summer came about because of corruption in Iceland seems pretty far-fetched. Shouting it from the roof tops won’t add to the arguments the funds have presented with the ESA and possibly in courts.

Saying that only domestic investors can invest in Iceland isn’t correct. This does no doubt refer to measures re offshore króna holders but it’s not a correct presentation.

Why doesn’t the Iceland Watch quote the UK research? As far as I know it comes from the Legatum Institute, connected to the Dubai-based Legatum Group established in 2006 by Christopher Chandler. The Legatum Institute recently had a discussion on Iceland and capital controls and has also published research of capital controls and anti-competitive policies. What is wholly missing is how the easing of capital controls has been done; it only focuses on the perceived harm caused by the most recent measures that has so upset the four funds.

Eh, creating 30.000 jobs in an economy with close to full employment in a country of 332.000 that needs to import people to fill jobs? And let’s put the figures in context: $5bn to $9bn amounts to 25-40% of Icelandic GDP. Is it credible that these latest measures hurting the four funds are really costing the Icelandic economy these sums annually? Intelligent readers can figure out the answers on their own.

If Iceland Watch intended to clarify to Icelanders the enormous losses they are suffering it would have helped to publish these losses in Icelandic króna, not in US dollars.

Serious allegation against a CBI official

It will be news to Icelanders that the CBI is investigating Sturla Pálsson for using his knowledge of the recent measures for his own gain via insider trading. Again, this is a statement with no verification. Given that the Icelandic media mostly ignores the ad and the reaction in Iceland is not to take this seriously at all it’s not certain that the CBI will see any reason to answer.

Pálsson has however recently been named in the Icelandic media related to breach of trust over the weekend October 4 to 5 2008: he told his wife, who was at the time the legal council at the Icelandic Banking Association (and is in addition closely related to Bjarni Benediktsson leader of the Independence Party and minister of finance) of the imminent Emergency Act. – The Iceland Watch allegation could possibly be a misunderstood echo of this recent reporting in the Icelandic media or indeed a new and much more serious allegation, unknown in Iceland.

Regardless of the basis for the allegation against Pálsson the question as it is put is ambivalent: Did Sturla Pálsson use his knowledge of the recently announced legislation on capital control that discriminate foreign investors in carrying out insider trading? – I guess this is insinuating Pálsson used his information to carry out insider trading but the sentence is so muddled that this isn’t clear at all. (The Iceland Watch text is: “Did Palsson use his position of knowledge about the recently announced capital controls legislation which discriminates against foreign investors to make insider trades?”)

Losing friends and influence… in Iceland

I’ve earlier expressed surprise that the funds think they are gaining friends and influence in Iceland through their alliance with Iceland Watch. This latest ad, apparently only directed at Icelanders, indicates a profound lack of understanding of the country they are trying to influence (tough I can’t imagine this approach will indeed work anywhere).

The photo of the ad above is my screenshot of a post on Facebook by minister of foreign affairs Lilja D. Alfreðsdóttir. Her comment to the ad is: “This attack on Icelandic interests is intolerable and what’s the aim of those behind it?” There are only few comments to the ad but some mention that this will hardly help the cause of those sponsoring it.

The ad is now also on the Iceland Watch website in English. The translation above is my translation as it gives some sense of what it looks like in Icelandic. The story is that this remarkable ad addressed to Icelandic voters is written in a version of Icelandic that resembles a Google translate text. Given that Icelanders are often quite pedantic about their language this will hardly induce Icelanders to take the ad seriously. Or as it says in one comment on Alfreðsdóttir’s Facebook page the ad is “a crime against the Icelandic language” – and that’s a serious offence in Iceland.

Updated: I’ve been made aware that Loomis Sayles is not at all involved in the Iceland Watch campaign against Iceland. I’m sorry that my earlier information here was not correct.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

International ad campaign and un-worried Icelanders

The offshore króna holders have now taken to the international media to cry out over the unfair treatment they have been submitted to by the Icelandic government. As earlier, they have allied with a strongly libertarian organisation, Institute for Liberty, a think-tank of sort. Perhaps the ads will shake international investors but the effect in Iceland seems to be next to none and the move is clearly not intended to win them friends in Iceland. Perhaps it’s too early to tell but so far, the International Monetary Fund does not seem to side with offshore króna holders and rating agencies seem forgiving. All of this is taking place as Iceland has taken yet another step to lift capital controls, which are now almost entirely lifted for both businesses and individuals.

After placing articles in various international media recently, “Iceland Watch,” an initiative organised by a so-called think tank, Institute for Liberty with the slogan “Defending America’s Right To Be Free” has now taken a new step: placing an ad in US, Danish and Icelandic media. As mentioned earlier, DCI Group, a political PR group based in Washington acts on behalf of the funds involved.*

If Iceland will be hit with a full-force international legislation the offshore króna holders may be the last to laugh but so far Icelanders are just shrugging their shoulders at the ad campaign they don’t really understand.

A clever campaign?

It’s not clear to me who this campaign is supposed to stir and shake. Here in Iceland, very few people have any particular understanding of the issues at stake. After the very unexpected outcome of the EFTA Court Icesave ruling in January 2013 most Icelanders will feel there is little to fear from international courts.

Of course an erratic opinion, the offshore króna case is a different problem but in addition to lacking the insight the words “international litigation” will not sound frightening in Iceland. Given how few Icelanders understand the issues at stake the ads look bizarre to most Icelanders.

There is now an election campaign going on in Iceland, election on October 29 and the offshore króna situation doesn’t figure at all. Nor are the capital controls an issue since they have now been lifted on domestic entities and individuals. I’ve earlier pointed out that Icelanders didn’t really seem to notice when measures to lift capital controls were announced.

I’m not sure the campaign rocks the boat among international investors. Anyone with a nuanced understanding of the Icelandic situation will sense that the Iceland Watch claims are not really fitting the situation in Iceland but bombastic, unintelligent and wide off the mark.

Select default? Doesn’t sound like it according to IMF or rating agencies

I have earlier expressed surprise at the action taken in Iceland. Iceland is clearly exposing itself to a legal risk – there is a question of discrimination, as the offshore króna holders claim and given the good times in Iceland it’s difficult to argue for the haircut.

That said, it’s interesting to observe that neither the IMF nor rating agencies, have so far admitted to the haircut potentially being a case of selected default. The offshore króna holders might have wanted the international community to kick Iceland in place but no one is moving for them except those the króna holders muster to speak their case.

Choosing Institute for Liberty as an ally is intriguing but perhaps not surprising given that many large players in the hedge fund world have libertarian leanings.

The offshore króna saga according to the CBI

In its latest Financial Stability report the CBI spells out the offshore króna problem:

Important steps have been taken towards lifting the capital controls in recent months. In May, Parliament passed legislation on the treatment of offshore krónur, providing for amendments designed to ensure that the special restrictions applying to offshore krónur under the capital controls will hold even though large steps are taken to lift controls on individuals and businesses. In June, the Central Bank of Iceland held a foreign currency auction in which it invited owners of offshore krónur to exchange their krónur for euros before general liberalisation begins. Although most of the bids submitted in the auction were accepted, large owners submitted bids at an exchange rate higher than the Central Bank could accept, and the stock of offshore krónur was therefore reduced by one-fourth. During the summer, the Central Bank set the Rules on Special Reserve Requirements for New Foreign Currency Inflows, and afterwards there was a reduction in new investment in domestic Treasury bonds, which can prove to be a source of volatile capital flows. With the passage of a bill of legislation in October, most of the capital controls on individuals and businesses have been lifted.

This is of course the offshore problem according to the CBI and Icelandic authorities, so far neither challenged by the IMF nor, perhaps more surprising, the rating agencies. The four large offshore króna holders will beg to differ.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Let them litigate

“Iceland’s selective default?” was the topic of a seminar in New York this week, organised by EMTA, the association of emerging markets investors. The measures taken by the Icelandic government and the Central Bank to reduce the offshore króna have placed the question mark in the question. Sadly, that question mark was not erased at the meeting but that doesn’t seem to worry the Icelandic government.

The concept selective default has been waved around recently in connection with the measures taken by the Icelandic government: at the strategic time, just before – what is or was to be – the last offshore króna auction, two foreign experts waved the “selective default” banner in Wall Street Journal and FT Alphaville (see my latest on this).

The two writers were present at the EMTA event in New York, James Glassman as the moderator, with Arturo Porzecanski on the panel together with Magnús Árni Skúlason, an Icelandic economist advising some of the funds holding the offshore króna and Lee Buchheit from Cleary, Gottlieb, advising the Icelandic government.*

Very much contrary to how the estates of the failed banks were dealt with last year (as I have repeatedly pointed out) – when nothing was finalised until the creditors had agreed to the measures – the Icelandic government, advised by Cleary, is engaging with offshore króna holders, to use an Icelandic expression, “with two ram’s horns,” meaning belligerently. Or as Buchheit said: let them litigate.

It is indeed a real possibility that the largest funds will litigate their way through this mess. The question is what that would entail for Iceland in terms of inter alia long-lasting and costly litigation, negative effect on credit ratings and possible delays in lifting capital controls, the goal of the whole exercise. In addition, several interesting points came up in the debate: the banks’ estate v offshore króna; recent restrictions on inflows; discrimination based on nationality – and was the recent auction really the last one?

Litigation: a real threat?

Icelandic authorities have deemed the auction successful because of good participation although CBI governor was more cautious. True, there were plenty of bids – but small ones. The large offshore króna holders didn’t participate or their offers weren’t accepted. Ergo, the bulk of the offshore króna is still inside capital controls. There is now litigation in the air, the largest offshore króna holders, all large international funds, have taken the first steps in that direction. The question is what the effect on Iceland and the Icelandic economy will be.

Buchheit said he wanted to puncture what the articles by Glasman and Porzecanski stated. He dismissed that the offshore króna holders had any claim on the Icelandic sovereign. Waving a dollar note, he stated that owning this note didn’t make him a creditor to the US; equally, owning a króna didn’t make the offshore króna holders a creditor to the Icelandic sovereign. – However, the large offshore króna holders aren’t waving króna bills but Treasury securities; around 2/3 of the offshore ISK319bn are Treasury securities which makes the situation slightly more convoluted.

Dismissing any comparison with Argentina, Buchheit did however neither directly counter the argument that the underlying assets are indeed Treasury securities nor give any tangible argument against the Argentina comparison except claiming it was not true. The funds could try litigating but neither Britain nor the Netherlands had found great sympathy for their cause, he said.

This must refer to the Icesave dispute, ruled on by the EFTA Court in January 2013 (link to the Judgement and my digest of the main points.) From the point of view of Iceland this seems a worryingly feeble argument since that dispute was, as far as I can see, fundamentally different from the issues at stake re the offshore króna (see below). Also, the argument that the offshore króna holders had bought their assets with a haircut inside capital controls seems beside the point; the point is that an owner of these securities can demand a payment on time and in full.

The testing point will be if courts – in Iceland and possibly elsewhere – will side with offshore króna holders or not. After all, Argentina decided to negotiate with those holding Argentinian sovereign bonds after a costly dispute lasting 15 years where Cleary Gottlieb was their main adviser (but not Buchheit until at the recent and final negotiations).

Cooperation last year, none this year

It now seems that the Icelandic strategy is to fix the offshore króna overhang with this last auction with remaining funds placed on locked low-interest accounts with the CBI, as the Treasury securities reach maturity, thus ignoring the possible legal risk. The next steps will then be towards lifting controls on the domestic economy, most importantly the pension funds. Only later will the locked accounts be revisited.

Magnús Árni Skúlason stressed that the funds he advised had come up with many proposals as to how to solve the issue. He pointed out that due to the very strong and booming Icelandic economy and sizeable foreign currency reserves it was difficult to argue for a haircut on grounds of a weak economy.

As I’ve repeatedly pointed out I find the difference in approach last year with the creditors of the failed banks and now with the offshore króna holders perplexing. In the latest IMF Article IV Consultation with Iceland, concluded on June 20, the IMF compares its 2014 recommendations with Authorities’ responses. On capital controls the IMF recommended in 2014 that the “updated liberalization strategy should be comprehensive, conditions based, and with an emphasis on a cooperative approach with appropriate incentives.”

As to the Authorities’ response the “updated liberalization strategy released in June 2015 takes a staged approach. The bank estates were resolved first, in a cooperative manner, which minimized legal and reputational risks and won credit rating upgrades. The authorities are now working to release offshore króna investments via an auction. Residents will be addressed thereafter (emphasis mine).

Minister of finance Bjarni Benediktsson has earlier emphasised the same as the IMF above, as did Buchheit at the EMTA meeting, that creditors have not challenged the measures last year in lifting capital controls on the banks’ estates. Due to the “cooperative manner” last year there were no legal challenges, which again raises the question why it’s suddenly not important to avoid the legal and reputational risk. So far, no clear answer.

Misconceptions on Icelandic “vindictiveness”

In his FT Alphaville guest blog Arturo Porzecanski criticised the Icelandic government for its measures on offshore króna, pointing out that the measures would place Iceland in selective default. He also strongly criticised recent law authorising the CBI to impose measures to discourage foreign inflows into Iceland.

Porzecanski embellished his points further at the EMTA meeting. According to him, the Icelandic government is, in his words, being “vindictive;” as if investors were responsible for the 2008 crisis, the government now wanted to “bleed investors” as it had tried last year with what he called a “departure tax” on creditors of the failed bank. However, he didn’t mention that the outcome an agreement with creditors (see my blog). To him this all smelled of punitive coercive action, just as in Greece and Argentina.

The tone in Iceland towards foreign investors has at times been harsh, mainly because of the politics at play, but Porzecanski’s description is to my mind out of proportions. After all, a 2010 report by an Icelandic Special Investigative Commission on the 2008 banking collapse, firmly and squarely placing the responsibility with Icelandic authorities, the CBI and politicians. And Icelandic bankers have been sentenced to imprisonment for criminal actions before the collapse of the banks.

The measures to temper inflows have long been expected: already in 2012 the CBI published a report on Prudential Rules Following Capital Controls, outlining what is needed to preserve financial stability once the capital controls have been lifted. Quoting IMF research one of the measures announced is restricting inflows, as indeed many countries have done over the past decades.

Porzecanski claims this is just done because the inflows were seen as a problem earlier, saying there is no justification for this measure. Well, he is right that the inflows were seen as a problem earlier, indeed the capital controls were put in place with the blessing of the IMF because of inflows, now the offshore króna overhang. As Porzecanski should be aware of and as emphasized in the 2012 report, IMF research underpins these measures, as do many economists. From the publication of the 2012 report it was clear that in due course these fairly traditional restrictions would be made use of.

Discriminating between foreigners and Icelanders?

A question from the audience at the EMTA event, on potential discrimination between Icelanders and foreigners, raised some interesting issues. The point was that Icelanders holding a króna would get a full króna whereas the offshore króna measures subjected foreign króna holders to getting only say 70 aurar (100 aurar = 1 króna). Buchheit’s point was that there was no discrimination involved. – Yet, the question still raises an interesting aspect.

The Emergency Law, passed on 6 October 2008 did differentiate between deposits held by individuals and entities domiciled in Iceland and abroad (which has partly shaped the definition of the offshore króna). This division was in fact a version of splitting the banks into a bad and good bank since roughly the foreign loans were put into the estates and Icelandic deposits into the new, living banks (it was slightly more complicated but this is the rough outline). – The Emergency Law has been contested in Icelandic courts and found to be in accordance with the constitution and Iceland’s international obligations.– These were extreme measures in extreme time taken by a sovereign defending its vital interests.

Eventual discrimination came up also in the Icesave case as the EFTA Surveillance Authority claimed in the EFTA Court, focusing on the use of the Icelandic Deposit Guarantee Fund, TIF. The question of discrimination was deflected in the Judgement due to the course of events in Iceland: the deposits had indeed been moved from the failed banks to the new banks but not reimbursed by the Icelandic TIF. Consequently, the Icelandic TIF didn’t need to reimburse foreign depositors, i.e. there was on discriminations involved and no breach of the relevant Directive. – Maybe it’s my lack of legal intricacies but I don’t quite see the relevance of the EFTA Court Icesave Ruling for the offshore króna problematic (as above, link to the Judgement and my digest of the main points.)

Is this really the last auction – and more confusion

In his introductory remarks Buchheit mentioned offhandedly that there are FX auctions all the time and this latest one was just another auction, in a series of 22 offshore króna auctions. Porzecanski asked if this meant this latest really was just another auction, would there be auctions following this announced last one but got no answer.

Porzecanski also pointed out that this last auction was indeed not a proper auction, more like bringing work of art to an auction house which then would set the price, i.e. no bidder on the other side.

During the question and answer session Skúlason mentioned that one concern of his was that part of the underlying assets was indeed Treasury bonds. Buchheit agreed there were some bonds, which would be paid in full and on time as Iceland had a stainless record in terms of fulfilling its sovereign obligations: it has never defaulted. – This statement seems to conflict with earlier statements – unless there is some tricky teleological interpretation behind the advice to the Icelandic government.

Last year, my main worry regarding the estates of the failed banks was if the government was ever going to have the political strength to agree on the necessary measures (mainly the haircut of the estates’ króna assets) and secondly that these measures would steer clear of legal risks. This year, the worry is that for some inexplicable reasons the cooperative method isn’t in vogue, in Iceland, possibly leading to legal risks and reputational damage so astutely avoided last year. Maybe I’m missing something but the discussions at the EMTA meeting didn’t inspire much confidence: “let them litigate” sounded decidedly belligerent compared to the cooperative approach last year.

*I had been invited to join the panel but ended up only listening via phone from London.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Iceland’s recovery: myths and reality (or sound basics, decent policies, luck and no miracle)

Icelandic authorities ignored warnings before October 2008 on the expanded banking system threatening financial stability but the shock of 90% of the financial system collapsing focused minds. Disciplined by an International Monetary Fund program, Iceland applied classic crisis measures such as write-down of debt and capital controls. But in times of shock economic measures are not enough: Special Prosecutor and a Special Investigative Committee helped to counteract widespread distrust. Perhaps most importantly, Iceland enjoys sound public institutions and entered the crisis with stellar public finances. Pure luck, i.e. low oil prices and a flow of spending-happy tourists, helped. Iceland is a small economy and all in all lessons for bigger countries may be limited except that even in a small economy recovery does not depend on a one-trick wonder.

“The medium-term prospects for the Icelandic economy remain enviable,” the International Monetary Fund, IMF, wrote in its 2007 Article IV Consultation

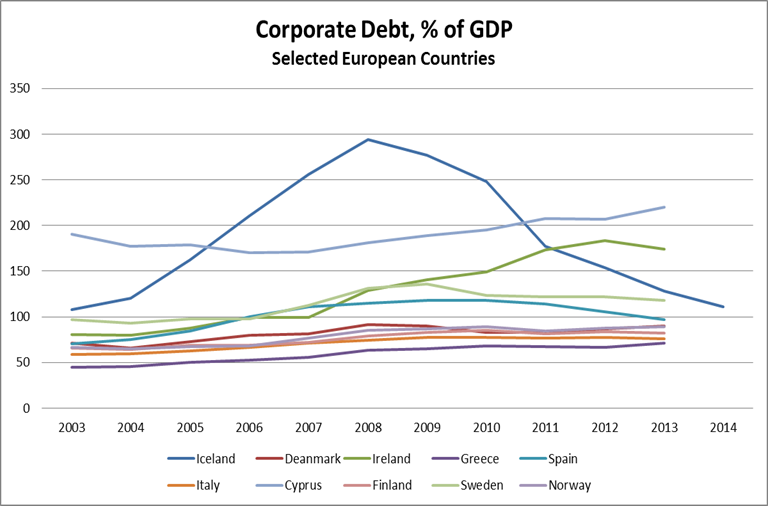

Concluding Statement, though pointing out there were however things to worry about: the banking system with its foreign operations looked ominous, having grown from one gross domestic product, GDP, in 2003 to ten fold the GDP by 2008. In early October 2008 the enviable medium-term prospect were clouded by an unenviable banking collapse.

All through 2008, as thunderclouds gathered on the horizon, the Central Bank of Iceland, CBI, and the coalition government of social democrats led by the Independence party (conservative) staunchly and with arrogance ignored foreign advice and warnings. Yet, when finally forced to act on October 6 2008, Icelandic authorities did so sensibly by passing an Emergency Act (Act no. 125/2008; see here an overview of legislation related to the restructuring of the banks and here more broadly on economic measures).

Iceland entered an IMF program in November 2008, aimed at restoring confidence and stabilising the economy, in addition to a loan of $2.1bn. In total, assistance from the IMF and several countries amounted to ca. $10bn, roughly the GDP of Iceland that year.

In spite of mostly sensible measures political turmoil and demonstrations forced the “collapse government” from power: it was replaced on February 1 2009 by a left coalition of the Left Green party, led by the social democrats, which won the elections in spring that year. In spite of relentless criticism at the time, both governments progressed in dragging Iceland out of the banking mess.

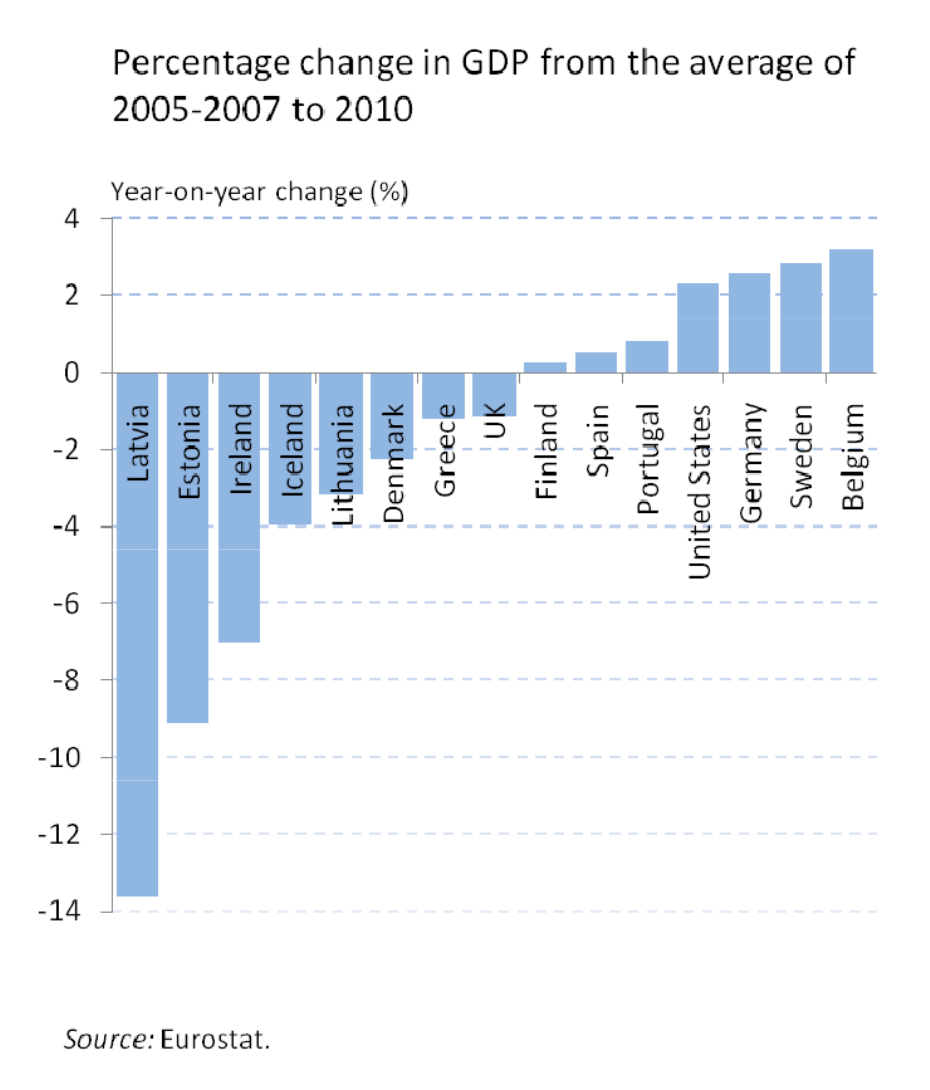

After the GDP contracted by 4% in the first three years the Icelandic economy was already back to growth summer 2011 and is now in its fifth year of economic growth. In 2015, Iceland became the first European country, hit by crisis in 2008-2010, to surpass its pre-crisis peak of economic output.

Iceland is now doing well in economic terms and yet the soul is lagging behind. Trust in the established political parties has collapsed: instead, the Pirate party, which has never been in government, enjoys over 30% following in opinion polls.

Compared to Ireland and Greece, Iceland’s recovery has been speedy, giving rise to questions as to why so quick and could this apparent Icelandic success story be applied elsewhere. Interestingly, much of the focus of that debate is very narrow and in reality not aimed at clarifying the Icelandic recovery but at proving or disproving aspects of austerity, the euro or both.

Unfortunately, much of this debate is misleading because it is based on three persistent myths of the Icelandic recovery: that Iceland avoided austerity, did not save its banks and that the country defaulted. All three statements are wrong: Iceland has not avoided austerity, it did save some banks though not the three largest ones and did not default.

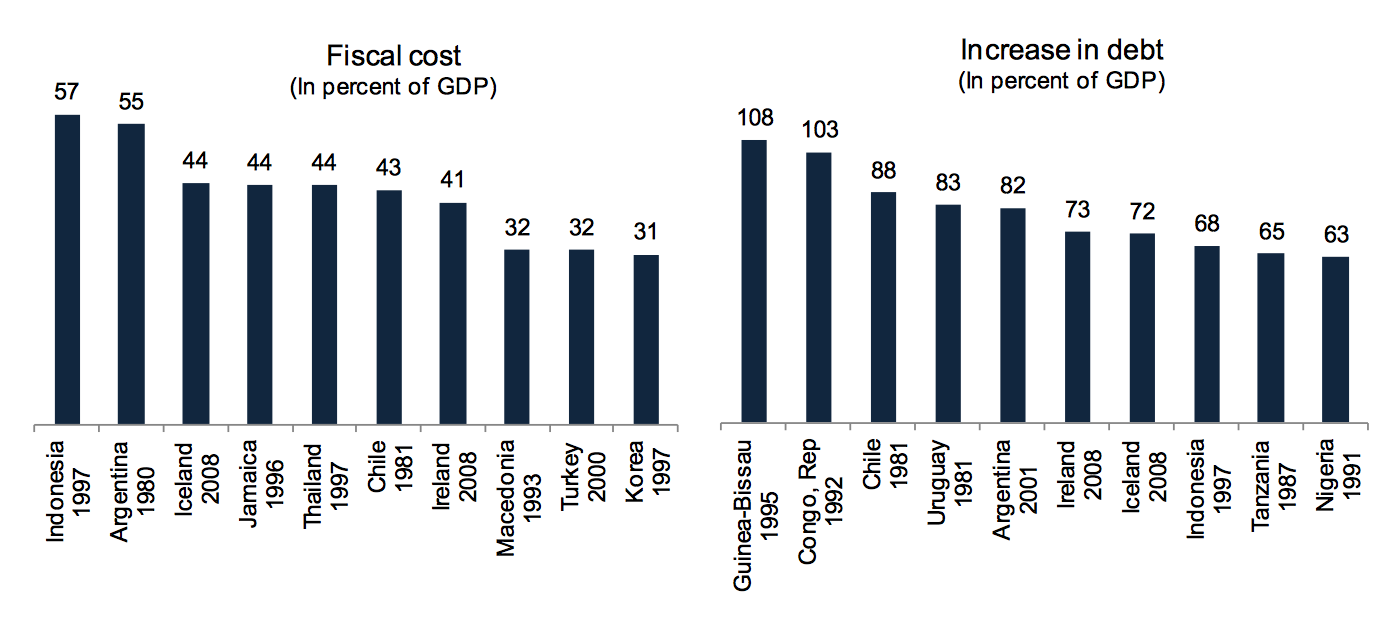

Indeed, the high cost of the Icelandic collapse is often ignored, amounting to 20-25% of GDP. Yet, not as high as feared to begin with: the IMF estimated it could be as much as 40%. The net fiscal cost of supporting and restructuring the banks is, according to the IMF 19.2% of GDP.

Costliest banking crisis since 1970; Luc Laeven and Fabián Valencia.

As to lessons to avoid the kind of shock Iceland suffered nothing can be learnt without a thorough investigation as to what happened, which is why I believe the report, a lesson in itself, by the Special Investigative Commission, SIC, in 2010 was fundamental. Tackling eventual crime, as by setting up the Office of the Special Prosecutor, is important to restore trust. Recovering from a collapse of this magnitude is not only about economic measures and there certainly is no one-trick fix.

On specific issues of the economy it is doubtful that Iceland, a micro economy, can be a lesson to other countries but in general, the lessons are simple: sound public finances and sound public institutions are always essential but especially so in times of crisis.

In general: small economies fall and bounce fast(er than big ones)

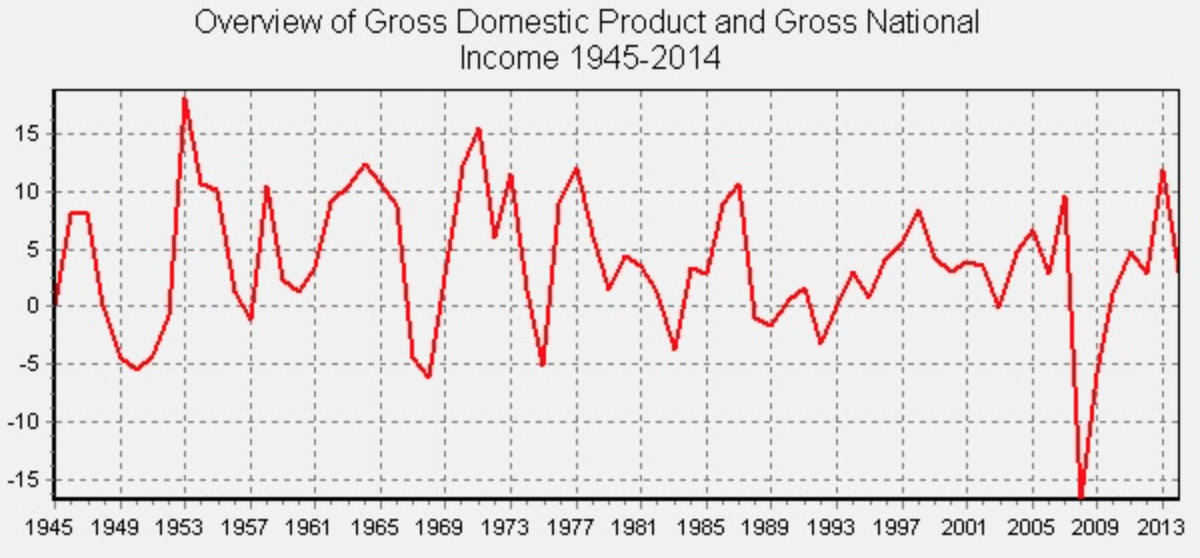

The path of the Icelandic economy over the past fifty years has been a path up mountains and down deep valleys. Admittedly, the banking collapse was a major shock, entirely man-made in a country used to swings according to whims of fishing stocks, the last one being in the last years of the 1990s.

(Statistics, Iceland)

Sound public finances, sound institutions

What matters most in a crisis country? Cleary a myriad of things but in hindsight, if a country is heading for a major crisis make sure the public finances are in a sound state and public authorities and institutions staffed with competent people, working for the general good of society and not special interests – admittedly not a trivial thing.

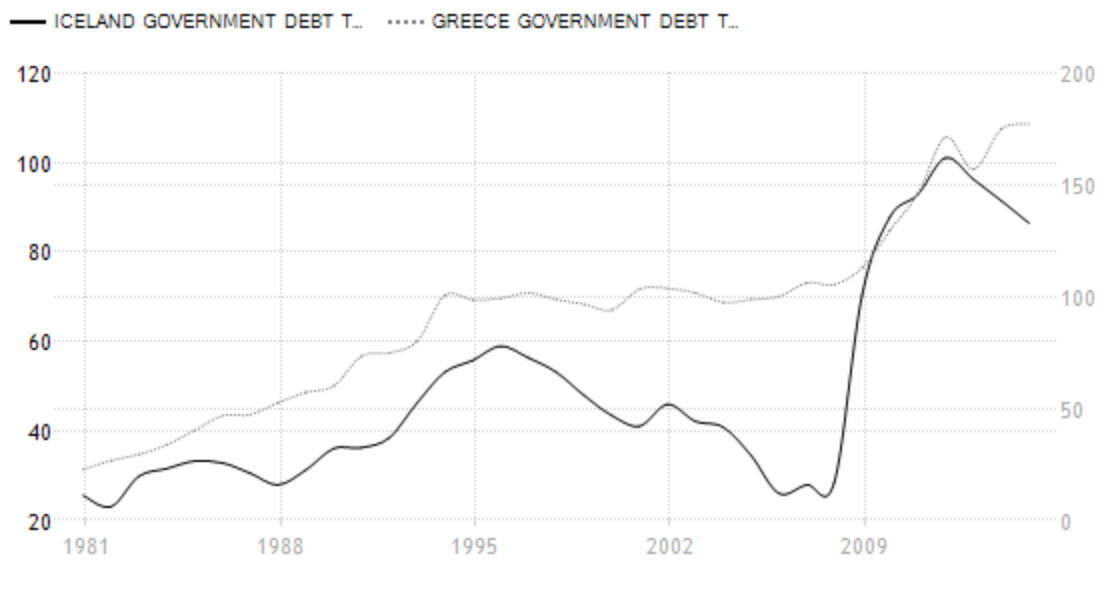

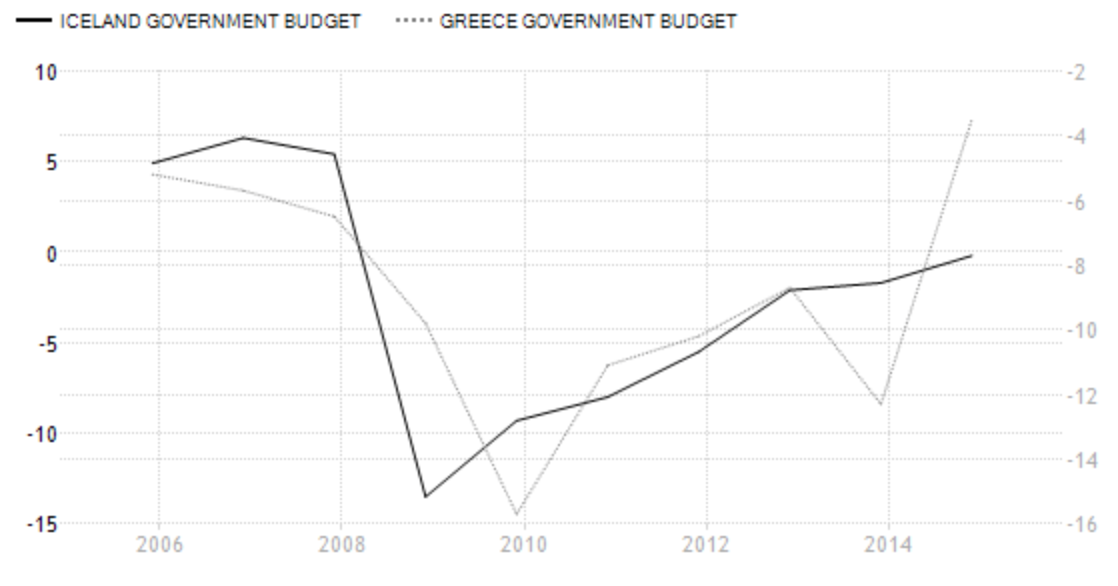

Since 1980 Icelandic sovereign debt to GDP was on average 48.67%, topped at almost 60% around the crisis in late 1990s and had been going down after that. Compare with Greece.

Trading Economics

Same with the public budget: there was a surplus of 5-6% in the years up to 2008, against an average of -1.15% of GDP from 1998 to 2014. With a shocking deficit of 13.5% in 2009 it has since steadily improved, pointing to a balanced budget this year and a tiny surplus forecasted for next year. Again, compare with Greece.

Trading Economics

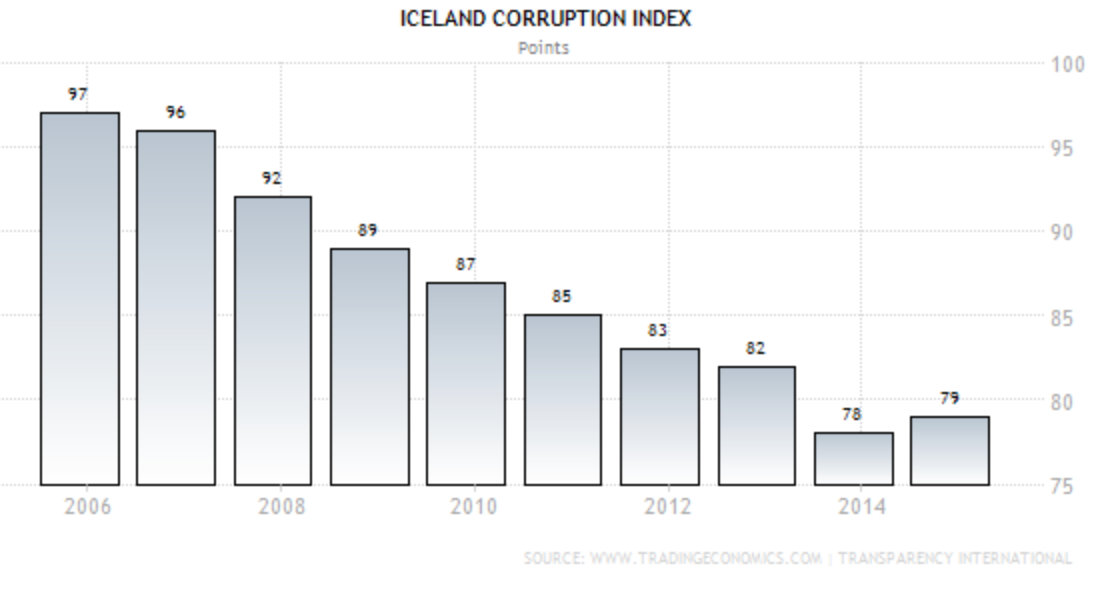

As to institutions, the CBI has been crucial in prodding the necessary recovery policies; much more so after change of board of governors in early 2009. Sound institutions and low corruption is the opposite of Greece, where national statistics were faulty for more than a decade (see my Elstat saga here).

Events in 2008

In early 2007, with sound state finances and fiscal strength the situation in Iceland seemed good. The banks felt invincible after narrowly surviving the mini crisis on 2006 following scrutiny from banks and rating agencies (the most famous paper at the time was by Danske Bank’s Lars Christensen).

Icelanders were keen on convincing the world that everything was fine. The Icelandic Chamber of Commerce hired Frederic Mishkin, then professor at Columbia, and Icelandic economist Tryggvi Þór Herbertsson to write a report, Financial Stability in Iceland, published in May 2006. Although not oblivious to certain risks, such as a weak financial regulator, they were beating the drum for the soundness of the Icelandic economy.

But like in fairy tales there was one major weakness in the economy: a banking system with assets, which by 2008 amounted to ten times the country’s GDP. Among economists it is common knowledge that rapidly growing financial sector leads to deterioration in lending. In Iceland, this was blissfully ignored (and in hindsight, not only in Iceland: Royal Bank of Scotland is an example).

Instead, the banking system was perceived to be the glory of Icelandic policies in a country that had only ever known wealth from the sea. Finance was the new oceans in which to cast nets and there seemed to be plenty to catch.

In early 2008 things had however taken a worrying turn: the value of the króna was declining rapidly, posing problems for highly indebted households – 15% of their loans were in foreign currency, i.a. practically all car loans. The country as a whole is dependent on imports and with prices going up, inflation rose, which hit borrowers; consumer-price indexed, CPI, loans (due to chronic inflation for decades) are the most common loans.

Iceland had been flush with foreign currency, mainly from three sources: the Icelandic banks sought funding on international markets; they offered high interest rates accounts abroad – most of these funds came to Iceland or flowed through the banks there (often en route to Luxembourg) – and then there was a hefty carry trade as high interest rates in Iceland attracted short- and long-term investors.

“How safe are your savings?” Channel 4 (very informative to watch) asked when its economic editor Faisal Islam visited Iceland in early March 2008. CBI governor Davíð Oddsson informed him the banks were sound and the state debtless. Helping the banks would not be “too much for the state to swallow (and here Oddsson hesitated) if it wanted to swallow it.” – Yet, timidly the UK Financial Services Authority, FSA, warned savers to pay attention not only to the interest rates but where the deposits were insured the point being that Landsbanki’s Icesave accounts, a UK branch of the Icelandic bank, were insured under the Icelandic insurance scheme.

The 2010 SIC report recounts in detail how Icelandic authorities ignored or refused advise all through 2008, refused to admit the threat of a teetering banking system, blamed it all on hedge funds and soldiered on with no plan.

The first crisis measure: Emergency Act Oct. 6 2008

Facing a collapsing banking system did focus the minds of politicians and key public servants who over the weekend of October 4 to 5 finally realised that the banks were beyond salvation. The Emergency Act, passed on October 6 2008 laid the foundation for splitting up the banks. Not into classic good and bad bank but into domestic and foreign operations, well adapted to alleviating the risk for Iceland due to the foreign operations of the over-extended banks.

The three old banks – Kaupthing, Glitnir and Landsbanki – kept their old names as estates whereas the new banks eventually got new names, first with the adjective “Nýi,” “new,” later respectively called Arion bank, Íslandsbanki and Landsbankinn. Following the split, creditors of the three banks own 87% of Arion and 95% of Íslandsbanki, with the state owning the remaining share. Due to Icesave Landsbanki was a different case, where the state first owned 81.33%, now 97.9%.

In addition to laying the foundation for the new banks, one paragraph of the Emergency Act showed a fundamental foresight:

In dividing the estate of a bankrupt financial undertaking, claims for deposits, pursuant to the Act on on (sic) Deposit Guarantees and an Investor Compensation Scheme, shall have priority as provided for in Article 112, Paragraph 1 of the Act on Bankruptcy etc.

By making deposits a priority claim in the collapsed banks interests of depositors were better secured than had been previously (and normally is elsewhere).

When 90% of a financial system is swept away keeping payment systems functioning is a major challenge. As one participant in these operations later told me the systems were down for no more than ca. five or ten minutes during these fateful days. All main institutions, except of course the three banks, withstood the severe test of unprecedented turmoil, no mean feat.

The coming months and years saw the continuation of these first crisis measures.

It is frequently stated that Iceland, the sovereign, was bankrupted by the collapse or defaulted on its debt. That is not correct though sovereign debt jumped from ca. 30% of GDP in 2008 until it peaked at 101% in 2012.

IMF and international assistance of $10bn

That fateful first weekend of October 2008 it so happened that there were people from the IMF visiting Iceland and they followed the course of events. Already then seeking IMF assistance was discussed but strong political forces, mainly around CBI governor Davíð Oddsson, former prime minister and leader of the Independence party, were vehemently against.

One of the more surreal events of these days was when governor Oddsson announced early morning on October 7 that Russia would lend Iceland €4bn, with maturity of three to four years, the terms 30 to 50 basis points over Libor. According to the CBI statement “Prime Minister Putin has confirmed this decision.” – It has never been clarified who offered the loan or if Oddsson had turned to the Russians but as the Cypriot and Greek government were to find out later this loan was never granted. If Oddsson had hoped that a Russian loan would help Iceland avoid an IMF program that wish did not come true.

On November 17, 2008 the Prime Minister’s Office published an outline of an Icelandic IMF program: Iceland was “facing a banking crisis of extraordinary proportions. The economy is heading for a deep recession, a sharp rise in the fiscal deficit, and a dramatic surge in public sector debt – by about 80%.”

The program’s three main objectives were: 1) restoring confidence in the króna, i.a. by using capital controls; 2) “putting public finances on a sustainable path”; 3) “rebuilding the banking system… and implementing private debt restructuring, while limiting the absorption of banking crisis costs by the public sector.”

An alarming government deficit of 13.5% was now forecasted for 2009 with public debt projected to rise from 29% to 109% of GDP. “The intention is to reduce the structural primary deficit by 2–3 percent annually over the medium-term, with the aim of achieving a small structural primary surplus by 2011 and a structural primary surplus of 3½-4 percent of GDP by 2012.” – This was never going to be austerity-free.

By November 20 2008 IMF funds had been secured, in total $2.1bn with $827m immediately available and the remaining sum paid in instalments of $155m, subject to reviews. The program was scheduled for two years and the loan would be repaid 2012 to 2015.

Earlier in November Iceland had secured loans of $3bn from the other Nordic countries together with Russia and Poland (acknowledging the large Polish community in Iceland). Even the tiny Faroe Islands chipped in with $50m. In addition, governments in the UK, the Netherlands and Germany reimbursed depositors in Icelandic banks, in all ca. $5bn. Thus, Iceland got financial assistance of around $10bn, at the time equivalent of one GDP, to see it through the worst.

In spite of a lingering suspicion against the IMF, both on the political left and right, there was never the defiance à la greque. Both the “collapse coalition” and then the left government swallowed the bitter pill of an IMF program and tried to make the best of it. Many officials have mentioned to me that the discipline of being in a program helped to prioritise and structure the necessary measures.

Recently, an Icelandic civil servant who worked closely with the IMF staff, told me that this relationship had been beneficial on many levels, i.a. had the approach of the IMF staff to problem solving been an inspiration. Here was a country willing to learn.

Part of the answer to why Iceland did so well is that the two governments more or less followed the course set out in he IMF program. This turned into a success saga for Iceland and the IMF. One major reason for success was Iceland’s ownership of the program: politicians and leading civil servants made great effort to reach the goals set in the program. – An aside to the IMF: if you want a successful program find a country like Iceland to carry it out.

Capital controls: a classic but much maligned measure

For those at work on crisis measures at the CBI and the various ministries there was little breathing space these autumn weeks in 2008. No sooner was the Emergency Act in place and the job of establishing the new banks over (in reality it took over a year to finalise) when a new challenge appeared: the rapidly increasing outflow of foreign funds threatened to sink the króna below sea level and empty the foreign currency reserves of the CBI.

On November 28 the CBI announced that following the approval of the IMF, capital flows were now restricted but would be lifted “as soon as circumstances allow.” De facto, Iceland was now exempt from the principle of freedom of capital movement as this applies in the European Economic Area, EEA. The controls were on capital only, not on goods and services, affected businesses but not households.

At the time they were set, the capital controls kept in place foreign-owned ISK650bn, or 44% of Icelandic GDP, mostly harvest from carry trades. Following auctions and other measures these funds had dwindled down to ISK291bn by the end of February 2015, just short of 15% of GDP. However, other funds have grown, i.e. foreign-owned ISK assets in the estates of the failed banks, now ca. ISK500bn or 25% of GDP.

In addition, there is no doubt certain pressure from Icelandic entities, i.e. pension funds, to invest abroad. The Icelandic Pension Funds Association estimates the funds need to invest annually ISK10bn abroad. Greater financial and political stability in Iceland will help to ease the pressure. (Further to the numbers behind the capital controls and plan to ease them, see my blog here).

With capital controls to alleviate pressure politicians in general have the tendency to postpone solving the problems kept at bay by the controls; this has also been the case in Iceland. The left government made various changes to the Foreign Exchange Act but in the end lacked the political stamina to take the first steps towards lifting them. With up-coming elections in spring 2013 it was clear by late 2012 that the government did not have the mandate to embark on such a politically sensitive plan so close to elections.

In spring 2015, after much toing and froing, the coalition of Independence party led by the Progressive party presented a plan to lift the controls. The most drastic steps will be taken this winter, first to bind what remains from the carry trades and second to deal with the estates, where ca. 80% of their foreign-owned ISK assets will be paid as a “stability contribution” to the state. (I have written extensively on the capital controls, see here). The IMF estimates it might take up to eight years to fully lift the controls.

It is notoriously difficult to measure the effects of capital controls. It is however a well-known fact that with time capital controls have a detrimental effect on the economy, as the CBI has incessantly pointed out in its Financial Stability reports.

In its 2012 overview over the Icelandic program the IMF summed up the benefits of controls:

“… as capital controls restricted investment opportunity abroad, both foreign and local holders of offshore króna found it profitable to invest in government bonds, which facilitated the financing of budget deficit and helped avoid a sovereign financing crisis.” – Considering the direct influence of inflation, due to CPI-indexation of household debt, the benefits also count for households.

Again, measuring is difficult but the stability brought by the controls seems to have helped though the plan to lift them came none too soon. Some economists claim the controls were unnecessary and have only done harm. None of their arguments convince me.

Measures for household and companies

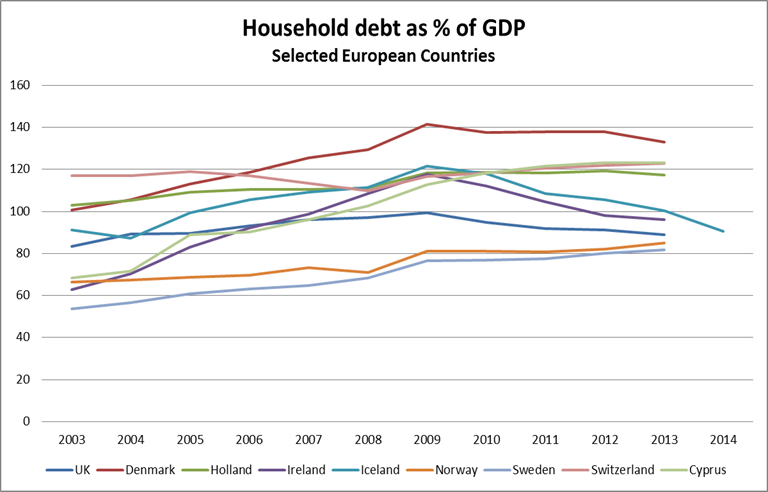

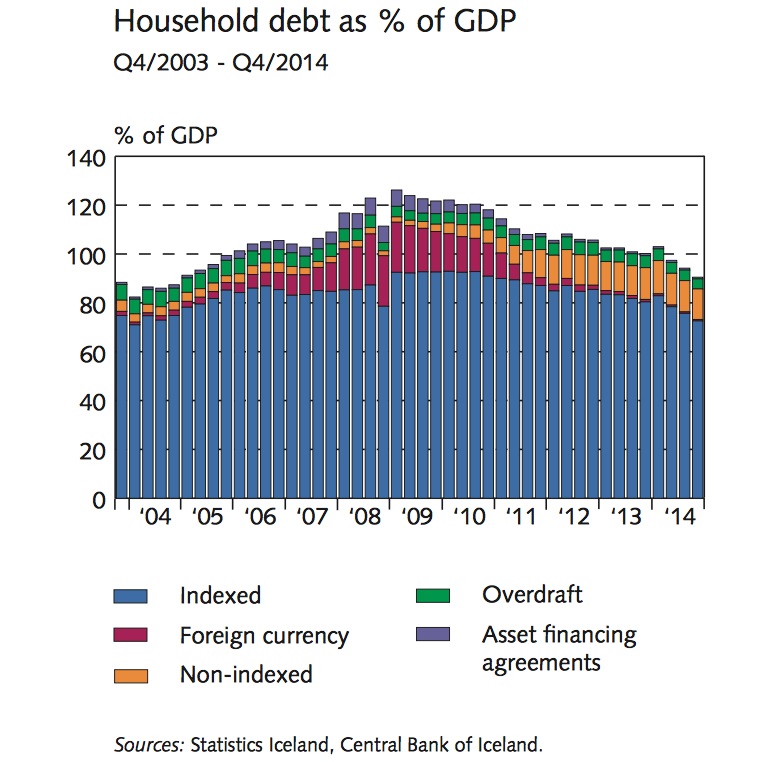

Icelandic households have for decades happily lived beyond their means, i.e. household debt has been high in Iceland. The debt peaked in 2009 but has been going down rapidly since then.

CBI

Already in early 2008, the króna started to depreciate versus other currencies. From October 2007 to October 2008 the changes were dramatic: €1 stood at ISK85 at the beginning of this period but at ISK150 in the end; by October 2009 the €1 stood at ISK185.

Even before the collapse it was clear that households would be badly hit in various ways by the depreciating króna, i.a. due to the CPI-indexation of loans as mentioned above. In addition, banks loaded with foreign currency from the carry trades had for some years been offering foreign currency loans, in reality loans indexed against foreign currencies. With the króna diving instalments shot up for those borrowing in foreign currency; as pointed out earlier, 15% of household debt was in foreign currency.

The left government’s main stated mission was to shield poorer households and defend the welfare system during unavoidable times of austerity following the collapse. In addition, there was also the point that in a contracting economy private spending needed to be strengthened.

The first measure aimed directly at households was in November 2008 when the government announced that people could use private pension funds to pay down debt.

Soon after the banking collapse borrowers with loans in foreign currency turned to the courts to test the validity of these loans. As the courts supported their claims the government stepped in to push the banks to recalculate these loans.

In total, at the end of January 2012 write-downs for households amounted to ISK202bn. For non-financial companies the write-downs totalled ISK1108bn by the end of 2011 (based on numbers from Icelandic Financial Services Association). In general, Icelandic households have been deleveraging rapidly since the crisis.

CBI

Governments in other crisis countries have been reluctant to burden banks with the cost of write-downs and non-performing loans. In Iceland, there was a much greater political willingness to orchestrate write-downs. The fact that foreign creditors owned two of the three banks may also have made it less painful to Icelandic politicians to subject the banks to the unavoidable losses stemming from these measures.

Changes in bankruptcy law

In 2010 the Icelandic Bankruptcy Act was changed. Most importantly, the time of bankruptcy was shortened to two years. The period to take legal action was shortened to six months.

There are exemptions from this in case of big companies and bankruptcy procedures for financial companies are different. However, the changes profited individuals and small companies. In crisis countries such as Greece, Ireland and Spain bankruptcy laws has been a big hurdle in restructuring household finances, only belatedly attended to.

… and then, 21 months later, Iceland was back to growth

It was indicative of the political climate in Iceland that when the minister of finance, trade and economy Steingrímur Sigfússon, leader of the Left Green party, announced in summer 2011 that the economy was now growing again his tone was that of an undertaker. After all, the growth was “only” forecasted to be around 2%, much less than what Iceland had enjoyed earlier. Yet, this was a growth figure most of his European colleagues would have shouted from the rooftops.

Abroad, Sigfússon was applauded for turning the economy around but he enjoyed no such appreciation in Iceland.

As inequality diminished during the first years of the crisis the government could to a certain degree have claimed success (see on austerity below). However, the left government did poorly in managing expectations. Torn by infighting, its political opponents, both in opposition and within the coalition parties never tired of emphasising that no measures were ever enough. That was also the popular mood.

The króna: help or hindrance?

Much of what has been written on the Icelandic recovery has understandably been focused on the króna – if beneficial and/or essential to the recovery or curse – often linked to arguments for or against the EU and the euro.

A Delphic verdict on the króna came from Benedikt Gíslason, member of the capital controls taskforce and adviser to minister of finance Bjarni Benediktsson. In an interview to the Icelandic Viðskiptablaðið in June 2015 Gíslason claimed the króna had had a positive effect on the situation Iceland found itself in. “Even though it (the króna) was the root of the problem it is also a big part of the solution.”

Those who believe in the benefits of own independent currency often claim that Iceland did devalue, as if that had been part of a premeditated strategy. That however was not the case: the króna has been kept floating, depreciating sharply when funds flowed out in 2008. The capital controls slammed the break on, stabilising and slowly strengthening the króna.

Lately, with foreign currency inflows, i.a. from tourism, the króna has further appreciated but not as much as the inflows might indicate: the CBI buys up foreign currency, both to bolster its reserve and to hinder too strong a króna. Thus, it is appropriate to say that the króna float is steered but devaluation, as a practiced in Iceland earlier (up to the 1990s) and elsewhere, has not been a proper crisis tool.

Had Iceland joined the EU in 1995 together with Finland and Sweden, would it have taken up the euro like Finland or stayed outside as Sweden did? There is no answer to this question but had Iceland been in the euro capital controls would have been unnecessary (my take on Icelandic v Greek controls, see here). Would the euro group and the European Central Bank, ECB, have forced Iceland, as Ireland, to save its banks if Iceland had been in the euro zone? Again, another question impossible to answer. After all, tiny Cyprus did a bail-in (see my Cyprus saga here).

On average, fisheries have contributed around 10% to the Icelandic GDP, 11% in 2013 and the industry provided 15-20% of jobs. Fish is a limited resource with many restrictions, meaning that no matter markets or currency fishing more is not an option.

Tourism has now surpassed the fishing industry as a share of GDP. Again, depreciating króna could in theory help here but Iceland is not catering to cheap mass tourism but to a more exclusive kind of tourism where price matters less. Attracting over a million tourists a year is a big chunk for a population of 330.000 but my hunch is that the value of the króna only has a marginal effect, much like on the fishing industry: the country’s capacity to receive tourists is limited.

Currency is a barometer of financial soundness. One of the problems with the króna is simply the underlying economy and the soundness of the governments’ economic policies or lack of it, at any given time. Sound policies have often been lacking in Iceland, the soundness normally not lasting but swinging. Older Icelanders remember full well when the interests of the fishing industry in reality steered the króna, much like the soya bean industry in Argentina.

The króna is no better or worse than the underlying fundamentals of the economy. In addition, in an interconnected world, the ability of a government to steer its currency is greatly limited, interestingly even for a major currency like the British pound. What counts for a micro economy like Iceland is not necessarily applicable for a reserve currency.

Needless to say, the króna did of course have an effect on how Iceland fared after the collapse but judging exactly what that effect has been is not easy and much of what has been written is plainly wrong. (I have earlier written about the right to be wrong about Iceland; more recent example here). In addition, much of what has been written on Iceland and the króna is part of polemics on the EU and the euro and does little to throw light on what happened in Iceland.

Iceland: no bailouts, no austerity?

There have been two remarkably persisting stories told about the Icelandic crisis: 1) it didn’t save its banks and consequently no funds were used on the banks 2) Iceland did not undergo any austerity. – Both these stories are only myths, which have figured widely in the international debate on austerity-or-not, i.a. by Paul Krugman (see also the above examples on the right to be wrong about Iceland) who has widely touted the Icelandic success as an example to follow. Others, like Tyler Cowen, have been more sceptical.

True, Iceland did not save its three largest banks. Not for lack of trying though but simply because that task was too gigantic: the CBI could not possibly be the lender of last resort for a banking system ten times the GDP, spread over many countries.

When Glitnir, the first bank to admit it had run out of funds, turned to the CBI for help on September 29 2008, the CBI offered to take over 75% of the bank and refinance it. It only took a few days to prove that this was an insane plan. The CBI lent €500m to Kaupthing on the day the Alþingi passed the Emergency Act, October 6 2008, half of which was later lost due to inappropriate collaterals. This loan is the only major unexplained collapse story.

The left government later tried to save two smaller banks – a futile exercise, which only caused losses to the state – and did save some building societies. The worrying aspect of these endeavours was the lack of clear policy; it smacked of political manoeuvring and clientilismo and only added to the high cost of the collapse, in international context.

As to austerity, every Icelander has stories to tell about various spending cuts following the shock in October 2008. Public institutions cut salaries by 15-20%, there were cuts in spending on health and education. (Further on cuts see IMF overview 2012).

With the left government focused on the poorer households it wowed to defend benefit spending and interest rebates on mortgages. These contributions are means-tested at a relatively low income-level but helped no doubt fending off widening inequality. Indeed, the Gini coefficients have been falling in Iceland, from 43 in 2007 to 24 in 2012, then against EU average of 30.5. (See here for an overview of the social aspects of the collapse from October 2011, by Stefán Ólafsson).

In addition, it is however worth observing that although inequality in general has not increased, there are indications that inter-generational inequality has increased, as pointed out in the CBI Financial Stability Report nr. 1, 2015: at end of 2013 real estate accounted for 82% of total assets for the 30 to 40 years age group, compared to 65% among the 65 to 70 years old. The younger ones, being more indebted than the older ones are much more vulnerable to external shocks, such as changes in property prices and interest rates. Renters and low-income families with children, again more likely to be young than older people, are still vulnerable groups.

In the years following the crisis the unemployment jumped from 2.4% in 2008 to peak of 7.6% in 2011, now at 4.4%. Even 7.6% is an enviable number in European perspective – the EU-28 unemployment was 9.5% in July 2015 and 10.9.% for the euro zone – but alarming for Iceland that has enjoyed more or less full employment and high labour market participation.

Many Icelanders felt pushed to seek work abroad, mostly in Norway, either only one spouse or the whole family. Poles, who had sought work in Iceland, moved back home. Both these trends helped mitigate cost of unemployment benefits.

Austerity was not the only crisis tool in Iceland but the country did not escape it. And as elsewhere, some have lamented that the crisis was not used better to implement structural changes, i.a. to increase competition.

The pure luck: low oil prices, tourism and mackerel

Iceland is entirely dependent on oil for transport and the fishing fleet is a large consumer of oil. Iceland is also dependent on imports, much of which reflect the price of oil, as does the cost of transport to and from the country. It is pure luck that oil prices have been low the years following the collapse, manna from heaven for Iceland.

The increase in tourism has been crucial after the crisis. Tourism certainly is a blessing but the jobs created are notoriously low-paying jobs. As anyone who has travelled around in Iceland can attest to, much of these jobs are filled not by Icelanders but by foreigners.

Until 2008, mackerel had never been caught in any substantial amount in Icelandic fishing waters: the catch was 4.200 ton in 2006, 152.000 ton in 2012. Iceland risked a new fishing war by unilaterally setting its mackerel quota. Fishing stocks are notoriously difficult to predict and the fact that the mackerel migrated north during these difficult years certainly was a stroke of luck.

The non-measureables: Special Prosecutor and the SIC report

As Icelanders caught their breath after the events around October 6 2008 the country was rife with speculations as to what had indeed happened and who was to blame. There were those who blamed it all squarely on foreigners, especially the British. But the collapse also changed the perception of Icelanders of corruption and this perception has lingered in spite of action taken against individuals. This seems to be changing, yet slowly.

When Vilhjálmur Bjarnason, then lecturer at the University of Iceland, now MP for the Independence party, said following the collape that around thirty men (yes, all males) had caused the collapse, many nodded.

Everyone roughly knew who they were: senior bankers, the main shareholders of the banks and the largest holding companies, all prominent during the boom years until the bitter end in October 2008. Many of these thirty have now been charged, some are already in prison and other fighting their case in courtrooms.

Alþingi responded swiftly to these speculations, by passing two Acts in December: setting up an Office of a Special Prosecutor, OSP and a Special Investigative Committee, SIC to clarify the collapse of the financial sector. These two Acts proved important steps for clearing the air and setting the records straight.

After a bumpy start – no one applied for the position of a Special Prosecutor – Ólafur Hauksson a sheriff from Reykjavík’s neighbouring town Akranes was appointed in January 2009. Out of 147 cases in the process of being investigated at the beginning of 2015, 43 are related to the collapse (the OSP now deals with all serious cases of financial fraud).

The Supreme Court has ruled in seven cases related to the collapse and sentenced in all but one case; Kaupthing’s second largest shareholder and three of the bank’s senior managers are now in prison after a ruling in the so-called al Thani case. – Gallup Iceland regularly measures trust in institutions. Since the OSP was included, in 2010, it has regularly come out on top as the institution enjoying the highest trust.

As to the SIC its report, published on 12 April 2010, counts a 2600 page print version, which sold out the day it was published, with additional material online; an exemplary work in its thoroughness and clarity.

The trio who oversaw the work – its chairman then Supreme Court judge Páll Hreinsson (now judge at the EFTA Court), Alþingi’s Ombudsman Tryggvi Gunnarsson and Sigríður Benediktsdóttir then lecturer in economics at Yale (now head of Financial Stability at the CBI) – presented a convincing saga: politicians had not understood the implication of the fast growing banking sector and its expansion abroad, regulators were too weak and incompetent, the CBI not alert enough and the banks egged on by over-ambitious managers and large shareholders who in some cases committed criminality.

How have these two undertakings – the OSP and the SIC – contributed to the Icelandic recovery? I fully accept that the effect, as I interpret it, is subjective but as said earlier: recovery after such a major shock is not only about direct economic measures.

Setting up the OSP has strengthened the sense that the law is blind to position and circumstances; no alleged crime is too complicated to investigate, be it a bank-robbery with a crowbar or excel documents from within a bank. The OSP calmed the minds of a nation highly suspicious of bankers, banks and their owners.

The benefit of the SIC report is i.a. that neither politicians nor special interests can hi-jack the collapse saga and shape it according to their interests. The report most importantly eradicated the myth that foreigners were only to blame – that Iceland had been under siege or attack from abroad – but squarely placed the reasons for the collapse inside the country.

The SIC had a wide access to documents, also from the banks. The report lists loans to the largest shareholders and other major borrowers. This clarified who and how these people profited from the banks, listed companies they owned together with thousands of Icelandic shareholders.

The SIC’s thorough and well-documented saga may have focused the political energy on sensible action rather than wasting it on the blame game. Interestingly, this effect is no less relevant as time goes by. To my mind, the atmosphere both in Ireland and Greece, two countries with no documented overview of what happened and why, testifies to this.

In addition, the report diligently focuses on specific lessons to be learnt by the various institutions affected. Time will show how well the lessons were learnt but at least heads of some of these institutions took the time and effort, with their staff, to study the outcome.

A country rife with distrust and suspicion is not a good place to be and not a good place for business. Both these undertakings cleared the air in Iceland – immensely important for a recovery after such a shock, which though in its essence an economic shock is in reality a profound social shock as well.

I mentioned sound institutions above. Their effect is not easily measureable but certainly well functioning key institutions such as ministries, National Statistics and the CBI have all been important for the recovery.

Lessons?

In its April 2012 Ex Post Evaluation of Exceptional Access Under the 2008 Stand-by Arrangement the IMF came up with four key lessons from Iceland’s recovery:

(i) strong ownership of the program … (ii) the social impact can be eased in the face of fiscal consolidation following a severe crisis by cutting expenditures without compromising welfare benefits, while introducing a more progressive tax system and improving efficiency; (iii) bank restructuring approach allowing creditors to take upside gains but also bear part of the initial costs helped limit the absorption of private sector losses by public sector; and (iv) after all other policy options are exhausted, capital controls could be used on a temporary basis in crisis cases such as Iceland, where capital controls have helped prevent disorderly deleveraging and stabilize the economy.

The above understandably refers to the economic recovery but recovering from a shock like the Icelandic one – or as in Ireland, Greece and Cyprus – is not only about finding the best economic measures, though obviously important. It is also about understanding and coming to terms with what happened.

As mentioned above, I firmly believe that apart from classic measures regarding insolvent banks and debt, both sovereign and private, the need to clarify what happened, as was done by the SIC and to investigate alleged criminality, as done by the OSP, is of crucial importance – something that Ireland (with a late and rambling parliamentary investigation), Greece, Cyprus and Spain could ponder on. All of this in addition to sound institutions and sound public finances before a crisis.

The soul lagging behind

In the olden days it was said that by traveling as fast as one did in a horse-drawn carriage the soul, unable to travel as fast, lagged behind (and became prone to melancholia). Same with a nation’s mood following an economic depression: the soul lags behind. After growth returns and employment increases it takes time until the national mood moves into the good times shown by statistics.

Iceland is a case in point. Although the country returned to growth, with falling unemployment, in 2011 the debate was much focused on various measures to ease the pain of households and nothing seemed ever enough.

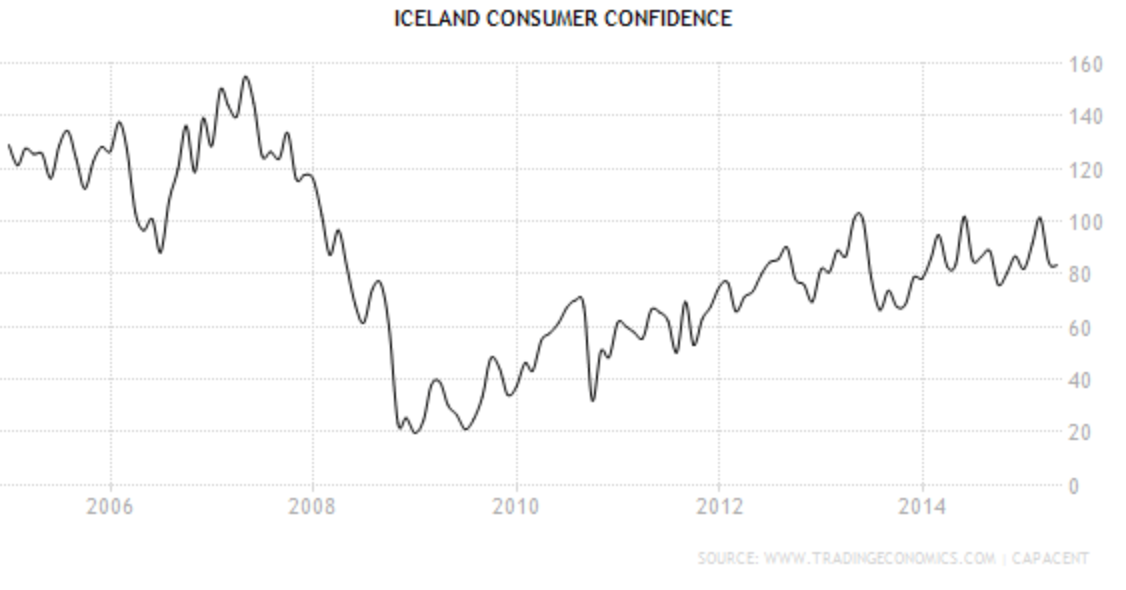

The Gallup Expectations monitor turned upwards in late 2009, after a steep fall from its peak in late 2007, and has been rising slowly since. Yet it is now only at the 2004 level; the Icelandic inclination to spending has been sig-sawing upwards. – Here two graphs, which indicate the mood:

With plan in place to lift capital controls, the last obvious sign of the 2008 collapse will be out of the way. Implementation will take some years; a steady and secure execution this coming winter will hopefully lift spirits in the business community.

Living intimately with forces of nature, volcanoes and migrating fish stocks, and now tourists, as fickle as the fish in the ocean, Icelanders have a certain sangue-froid in times of uncertainty. Actions by the three governments since the collapse have at times been rambling but on the whole they have sustained recovery.

A sign of the lagging soul is that growth has not brought back trust in politics. Politicians score low: the most popular party now enjoying ca. 35% in opinion polls, almost seven years after the collapse and four years since turning to growth, is the Pirate party, which has never been in government.

Recovery (probably) secured – but not the future

As pointed out in a recent OECD report on Iceland the prospect is good and progress made on many fronts, the latest being the plan to lift capital controls: “inflation has come down, external imbalances have narrowed, public debt is falling, full employment has been restored and fewer families are facing financial distress. “

However, the worrying aspect is that in addition to fisheries partly based on cheap foreign labour the new big sector, tourism, is the same. Notoriously low productivity – a chronic Icelandic ill – will not be improved by low-paid foreign labour. Well-educated and skilled Icelanders are moving abroad whereas foreigners moving to the country have fewer skills. Worryingly, there is little political focus on this.

As the OECD points out “unemployment amongst university graduates is rising, suggesting mismatch. As such, and despite the economic recovery, Iceland remains in transition away from a largely resource-dependent development model, but a new growth model that also draws on the strong human capital stock in Iceland has yet to emerge.”

Iceland does not have time to rest on its recovery laurels. Moving out of the shadow of the crisis the country is now faced with the old but familiar problems of navigating a tiny economy in the rough Atlantic Ocean.

This post is cross-posted with A Fistful of Euros.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Gunnlaugsson goes solo on the abolition plan: beginning of an action plan or end of coalition?

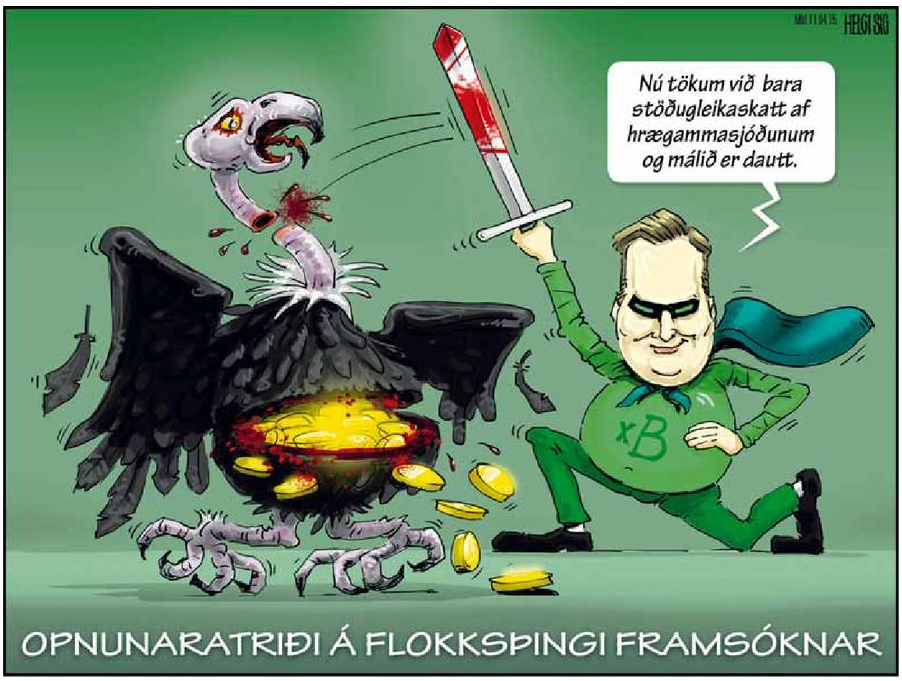

In an “overview speech” at his party’s annual conference prime minister Sigmundur Davíð Gunnlaugsson announced today an outline of an abolition plan, short on content – only stability tax mentioned – but long on scaremongering of creditors and their wealth amassed in Iceland, with strikingly wrong numbers. From earlier statements by Bjarni Benediktsson minister of finance, whose remit the capital controls are, it is difficult to imagine he condones Gunnlaugsson’s views. Apart from whether this is a good plan or not it is worrying that the prime minister has lately been quite “statement-happy,” expressing views, which neither Benediktsson nor others have heard of until reported on in the media.

Before the Parliament’s summer recess the government will present a Bill to lift capital controls. This is what prime minister Sigmundur Davíð Gunnlaugsson leader of the Progressive party announced at the party’s annual conference Friday.

The only concrete measure Gunnlaugsson announced is “stability tax” that according to the prime minister will bring billions of Icelandic króna to the state coffers. As earlier, Gunnlaugsson emphasised the financial gain and the need to remove the new bank’s ownership from creditors. Worryingly, Gunnlaugsson presented wrong numbers and statements, which do not quite seem to make sense or at least rest on some fairly particular interpretation of reality.

From earlier statements by minister of finance Bjarni Benediktsson on capital controls it is difficult to see how Gunnlaugsson’s statements fit Benediktsson’s prerequisites of an orderly process based on classic measures, as outlined in Benediktsson’s last status report on the controls (see my take on it here). In addition, Gunnlaugsson has now taken the initiative from Benediktsson. The question is if he did at all discuss his speech with Benediktsson beforehand – allegedly, the two do not spend much time and effort communicating.

This in addition to some recent statements from Gunnlaugsson, which have not been discussed with Benediktsson or in the government. Also, there is the report by his fellow party member Frosti Sigurjónsson on monetary systems, another solo initiative by the prime minister.

With Gunnlaugsson’s latest statement there have been some speculation if Benediktsson and his party feel to stay in this coalition much longer. However, it might prove tricky for the party to leave without making it look as if they are somehow caving into creditors whereas Gunnlaugsson is gallantly fighting them.

Icelanders are slowly learning that whenever the prime minister speaks they glimpse the world according to his “Weltanschuung” – and it does not always seem to rhyme with reality.

Wrong numbers, remarkable calculations

In his speech Gunnlaugsson said, according to Icelandic media (I have so far not found a link to the speech), that most of the creditors were hedge funds that having bought the claims in a fire sale had profited quite enormously. The claims in the collapsed banks are so high, he said, that it is difficult to imagine it – as much as ISK2500bn (which being ca 1 ½ Icelandic GDP is not that hard to imagine). “Were this sum invested it would be possible to hold Olympic games, just for the interests, every four years, for eternity.”

This is wrong. The claims themselves are around ISK7000bn, the assets of the three estates are at ISK2250bn. As to the interests of this sum possibly being a sort eternity machine to finance the Olympics this hardly adds up. If we postulate that half of the assets are in cash at 1% interest rates and other assets carry 5% interest rates the annual interest rates would amount to ISK67.5bn or ISK270bn, just under $2bn, over four years. Would that be enough to finance the Olympics? The cost of the London games amounted to $14.6bn, ISK2000bn, the cost of Sochi $51bn, ISK7000bn.

This is worryingly wrong and far beyond reality. The fact that the prime minister does not know the correct numbers is bad but almost worse that he does not have advisers to enlighten him and find the correct numbers for him. Whoever tried to impress him with the Olympics parallel if clearly not fit to be an adviser on financial matters.

Tellingly, all these numbers and the Olympics calculations were diligently reported on Morgunblaðið’s front page today.

The spying conniving creditors

With all these assets (albeit a wrong number) Gunnlaugsson concluded that creditors would be prepared to go to some length to protect their assets. Who wouldn’t? he asked, considering the sums.

“It is known that most if not all larger legal firms in Iceland have worked on behalf of these parties or their representatives. It would be hard to find a PR firm, operating in Iceland that has not worked for these same parties in addition to a large number of advisers in various fields. This activity is almost frightening and it is impossible to tell how far they reach but according to recent news creditors have bought services to protect their interests in this country for ISK18bn in recent years.”