Search Results

Cyprus: the fourth – and final – bailout? (updated)

The Memorandum of Understanding for Cyprus seems to indicate that restructuring of banks (though possibly only a timid one) should precede any financial aid to them. If this is the case, the Cyprus bailout will be a changing course in the story European bailouts.

With every Eurozone bailout, some new lessons are learnt – but so far, not the only sensible lesson: letting banks fail if needed, aggressively writing down debt and restructuring. That is a pie in the sky for European taxpayers, until the planned banking union, with not only a banking supervision but also a unified resolution structure will come into being. Until that rosy future dawns, banks are bailed out, bondholders and the official sector paid – though, as Greece shows, not always in full now.

But the Cyprus Memorandum of Understanding, the basis of its bailout, indicates that for the first time, restructuring failing banks might be a prerequisite for the bailout. If that is the case, the Cyprus bailout might help the EU turning a page – though the MoU raises the question if the restructuring is tough enough.

How much does Cyprus need?

How much is needed from the troika this time? The first numbers I heard floated earlier this year from a Cypriot source was something like €5-6bn to recapitalise the banks and slightly less for the sovereign, in total around €11bn. The number now mentioned is €17bn. Pimco, having been called in to do an independent estimate of the need, landed on €9.1-9.6bn – while others think it’s too low and €13bn would be more likely.

Much was made of the impact of the Greek writedown in March on Cypriot banks. No doubt, the effect was a serious one but the Greek writedown was only the last straw, not the real reason for the Cypriot failure. Already in the latest available IMF report, from 2011, on Cyprus there were ominous indications (emphasis mine):

The large banking sector, with assets totaling over 8 times GDP by the broadest measure, and with significant exposure to Greece, is a significant vulnerability. Banks face significant capital needs to reflect mark to market valuations on their sovereign bond holdings and to achieve a 9 percent core tier one capital ratio, as mandated by the European Banking Authority. Non-performing loans are increasing, and further loan deterioration could add to recapitalization needs. Meanwhile, the system is also vulnerable to an outflow of deposits in the event of adverse circumstances. Cypriot banks receive significant liquidity support from the European Central Bank.

With all these significant issues further to the significant numbers:

A large banking system with heavy exposure to Greece is a major vulnerability of the Cypriot economy. Bank assets total €152 billion (835 percent of GDP), while assets of commercial banks with Cypriot parents are €92 billion (500 percent of GDP). Exposure of these banks to Greece totals €29 billion, or 160 percent of GDP, including both Greek government bonds and loans to Greek residents. They also hold €1.6 billion of Cypriot government bonds but minimal amounts of sovereign debt of other peripheral euro area countries.

And as to the Greek writedown being the lethal hit to the Cypriot banks the IMF 2011 report puts that in perspective:

Commercial banks with Cypriot parents hold €92 billion (505 percent of GDP) in assets, dominated by three large banks (Bank of Cyprus, Marfin Popular Bank, and Hellenic Bank) which together account for 97 percent of total assets of this group. They have large foreign operations through branches and subsidiaries, primarily through the Marfin and Bank of Cyprus branches in Greece. They hold €23 billion (130 percent of GDP) in loans to Greek residents and €5 billion of Greek government bonds.

Did a 50% writedown of nominal value of €5bn in total assets of €152bn cause the collapse of the Cypriot banking system? Hardly. It was, as the 2011 IMF report shows, already a system about to collapse.

To say that loans are now being negotiated with the troika makes it seem as if Cyprus is still functioning on its own. That is not the case. As the IMF report mentions already last year Cypriot banks were receiving significant support from the ECB. Last May, FT Alphaville wrote on the ECB Emergency Liquidity Assistance Cypriot banks were making use of, gauging the banks had already had €3.8bn shot, which might well be an underestimate since this had probably been going on for a good part of 2011.

Restructuring – or tinkering?

Ever since it became clear that the troika aid to Ireland was a poisonous chalice – it saved Ireland from bankruptcy there and then but burdened the sovereign with private debt – the challenge has been how to avoid this debt migration from the private to the public sector. As is always the case under these circumstances, there are only two options for Cyprus: restructuring – or to borrow to pay its creditors in full.

During the Trichet aera at the ECB the word “restructuring” was unmentionable within the bank.

Cypriot media has published the Memorandum of Understanding between the troika and Cyprus (or at least a draft of it; in a Word version, fresh with “track changes”). Interestingly, key programme objective number 1 is:

to restore the soundness of the Cypriot banking sector by thoroughly restructuring, resolving and downsizing financial institutions, strengthening of supervision, addressing expected capital shortfall and improving liquidity management;

At least the word “restructuring” is now part of the bailout vocabulary.

Then there is this paragraph:

With the goal of minimising the cost to tax payers, bank shareholders and junior debt holders will take losses before state-aid measures are granted. Before any state recapitalisation is granted, the Central Bank of Cyprus will require a conversion of any outstanding junior debt instruments into equity for the purpose of protecting the public interest in financial stability, including by implementing voluntary or, if necessary, mandatory subordinated liability exercises (SLE). In order to facilitate a voluntary SLE, a small premium can be offered in line with state aid rules. To this end, the necessary legislation will be introduced no later than [January 2013]. The Central Bank of Cyprus together with the EC, the ECB and the IMF will monitor any operation converting junior debt instruments into equity.

As far as I understand the EU is not entirely against restructuring. But so far, the ECB cannot bring itself to go further than to junior debt – which is pretty useless in terms of solving the problem once and for all and not in painful steps over many years, à la Greece.

However, compared to the Greek MoU from February, there is a significant change in the Cyprus MoU: in Cyprus, it seems that restructuring will – or should – precede any financial assistance. In the Greek one, this was not the case. How this Cypriot restructuring will be carried out is a key thing. If it is just junior debt and not something more forceful this will be a tinkering and not the really necessary cleaning up, so lacking i.a. in Ireland.

Bailing out Cyprus – (in)directly helping the Russian Mafia?

Cyprus poses a particular problem: it is awash with Russian money. The historic ties go back before the collapse of the Soviet Union, strengthened by the Orthodox church. Later, Cyprus was the predilected offshore haven for Russian oligarchs and they actually followed the money. Limassol has the nickname Limassolgrad for a reason.

According to Spiegel, the German secret service, Bundesnachrichtendienst, BND, has warned that financial assistance to Cyprus amounts to assisting the Russian Mafia. A bailout for Cyprus is bound to raise not just the usual questions of why and how and who is paying more than others – but also how it will affect the shadowy side of the Cypriot banking system.

A year ago Cyprus got a loan of €2.5bn from Russia. This autumn, it hoped to negotiate another €5bn but the loan never materialized. The existing loan apparently has a tenor of 4 ½ years, meaning it would most likely come due during the time Cyprus is under the troika’s intensive care. The troika has to ask itself how it feels about paying back the Russian loan.

Cyprus is not only a haven for Russians. The island has all the attributes of an offshore haven, including a huge flow of money of uncertain origin. It is an international finance centre, allegedly with 40.000 companies registered on the island. Active companies pay a levy of €350 but dormant companies don’t pay anything. One of the possible revenue streams now under preparation is to let all companies, active or not, pay the levy.

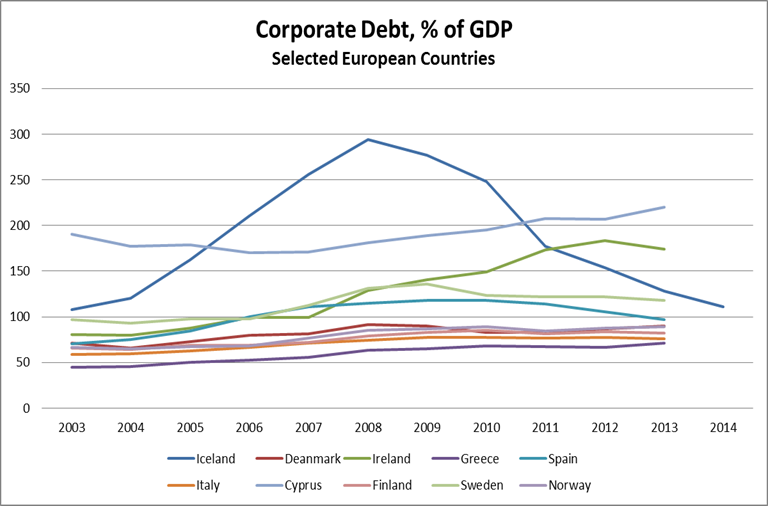

My feeling has been that Cyprus was mini-Greece, i.e. unclear as to the real size of the problem though with much lower numbers in a much smaller economy. My Cypriot source tells my I’m completely wrong – 17bn is the max number sought but most likely the island will use €15bn. I am not entirely convinced, given the huge and fast-growing, ballooning banks – I’ve seen too much of the Icelandic banks – not to mention the offshore environment. Qui vivra verra.

*For those who want to see an overview of the structure of the Cypriot banking system, i.e. types of banks and business areas, with thought-provoking numbers, take a look at the very informative Box 4 in the IMF 2011 report (ah, where would we be without the deliciously juicy IMF reports… and, since I’m mentioning names, enticing Eurostat data)

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

The Luxembourg walls that seem to shelter financial fraud

People, mostly pensioners, who previously took out equity release loans with Landsbanki Luxembourg, have for a decade been demanding that Luxembourg authorities look into alleged irregularities, first with the bank’s administration of the loans, then how the liquidator dealt with their loans after Landsbanki failed. The Duchy’s regulator, CSSF, has staunchly refused to consider this case. Yet, following criminal investigations in Iceland into the Icelandic banks, where around thirty people have been found guilty and imprisoned over the years, no investigation has been opened in Luxembourg into the Duchy operations of the Icelandic banks so far. Criminal investigation in France against the Landsbanki chairman at the time and some employees ended in January this year: all were acquitted. Recently, investors in a failed Luxembourg investment fund claimed the CSSF’s only interest is defending the Duchy’s status as a financial centre.

Out of many worrying aspects of the rule of law in Luxembourg that the Landsbanki Luxembourg case has exposed, the most outrageous one is still the intervention in 2012 of the State Prosecutor of Luxembourg, Robert Biever. At the time, a group of the bank’s clients, who had taken out equity release loans with Landsbanki Luxembourg, were taking action against the bank’s liquidator Yvette Hamilius. Then, out of the blue, Biever, who neither at the time nor later, had investigated the case, issued a press release. Siding with Hamilius, Biever stated that a small group of the Landsbanki clients, trying to avoid paying back their loans, were resisting to settle with the bank.

Criminal proceedings in Iceland against managers and shareholders of the Icelandic banks, where around 30 people have been found guilty, show that many of the dirty deals were carried out in Luxembourg. Since prosecutors in Iceland have obtained documents in Luxembourg in these cases, all of this is well known to Luxembourg authorities. Yet, neither the regulator, Commission de Surveillance du Secteur Financier, CSSF, nor other authorities have apparently seen any ground for investigations, with one exception. A case related to Kaupthing has been investigated but, so far, nothing has come out of that investigation (here more on that case, an interesting saga in itself).

However, it now seems that not only the Landsbanki Luxembourg clients have their doubts about on whose side the CSSF really is. Investors in a Luxembourg-registered fund claim they were defrauded but that the CSSF has been wholly unwilling to investigate their claims. Their conclusion: the CSSF’s only mission is to promote Luxembourg as a financial centre, which undermines “its responsibility to protect investors.”

That would certainly chime with the experience of the Landsbanki clients. Further, the fact that Luxembourg is a very small country, which greatly relies on its financial sector, might also explain why the Landsbanki Luxembourg clients have found it so difficult even to find lawyers in Luxembourg, willing to take on their case.

A slow realisation – information did not add up

It took a while before borrowers of equity release loans from Landsbanki Luxembourg started to suspect something was amiss. The messages from the bank in the first months after the liquidators took over, in October 2008, were that there was nothing to worry about. However, it quickly materialised that there was indeed a lot to worry about: the investments, which had been made as part of the loans, seemed to have been wiped out; what was left was the loan, which had to be paid off.

In addition, there were conflicting information as to the status of the loans, the amounts that had been paid out and the status on the borrowers’ bank accounts. The borrowers, mostly elderly pensioners in France and Spain, many of them foreigners, took out loans with Landsbanki Luxembourg, with their properties in these two countries as collaterals. To begin with, they were to begin with dealing with this situation alone, trying to figure out on their own what was going on. It took the borrowers some years until they had found each other and had founded an action group, Landsbanki Victims Action Group.

Landsbanki clients in Spain are part of an action group in Spain against equity release loans, The Equity Release Victims Association, Erva. The Landsbanki clients have taken the Landsbanki estate to court in Spain in order to annul the administrator’s recovery actions there. Lately, the clients have been winning but given that cases can be appealed it might take a while to bring these cases to a closure. The administrator’s attempt to repatriate Spanish court cases against the bank to Luxembourg have, so far, apparently not been successful.

Criminal case in France, civil cases in France and Spain

Finding a lawyer, both for the group and the single individuals who took action on their own, proved very difficult: it has taken a lot of time and effort and been an ongoing problem.

By January 2012, a French judge, Renaud van Ruymbeke, had opened an investigation into the loans in France. The French prosecutor lost the case in the Criminal Court of First Instance in Paris in August 2017; on 31 January 2020, the Paris Appeal Court upheld the earlier ruling, acquitting Landsbanki Luxembourg S.A., in liquidation and some of its managers and employees at the time. The case regarded the operations before the bank’s collapse, the administrator was not prosecuted. The Public Prosecutor as well as the borrowers, in a parallel civil case, have now challenged the Paris Appeal Court decision with a submission to the Cour de cassation.

While this case is still ongoing, the administrator’s recovery actions in France were understood to be on hold. According to Icelog sources, that has not entirely been the case.

Landsbanki Luxembourg: opacity before its demise in October 2008

The main issues with the bank’s marketing and administration of the loans has earlier been dealt with in detail on Icelog but here is a short overview:

As Hamilius mentioned in an interview in May 2012 with the Luxembourg newspaper Paperjam, the loans were sold through agents in Spain and France. After all, the whole operation of the equity release loans depended on agents; Landsbanki Luxembourg was operating in Luxembourg, not in France and Spain.

The use of agents has an interesting parallel in how foreign currency loans, FX loans, have been sold in Europe (see Icelog on FX loans and agents). In the case of FX loans, the Austrian Central Bank deemed that one reason for the unhealthy spread of these risky loans was exactly because they were sold through agents. Agents had great incentives to sell the loans and that the loans were as high as possible but no incentive to warn the clients against the risk. Interestingly, the sale of financial products through agents has been found illegal in some European cases regarding FX loans.*

Other questions relate to how the equity release loans were marketed, i.e. the information given, that the bank classified the borrowers as professional investors, which greatly diminished the bank’s responsibility in informing the clients and also what sort of investments they would choose for the investment part of the loan. Life insurance was a frequent part of the package, another familiar feature in FX loans.

Again, given rulings by the European Court of Justice on FX loans, it seems incomprehensible that the same conditions should not apply to equity release loans as FX loans. After all, there are exactly the same issues at stake, i.e. how the loans were sold, how borrowers were informed and classified (as professional investors though they clearly were not).

How appropriate the investments were for these types of loans and clients is an other pertinent question in this saga. After the collapse of Landsbanki Luxembourg, the borrowers discovered to their great surprise that in some cases the investments were in Landsbanki bonds, even in its shares, as well as in shares and bonds of the two other Icelandic banks, Glitnir and Kaupthing.

That the bank would invest its own loans in the bank’s bonds is simply outrageous. Already in analysis of the Icelandic banks made by foreign banks as early as 2005 and 2006, the high interconnection of the Icelandic banks, was seen as a risk. Thus, if the CSSF had at all had its eyes on these investments, made by a bank operating in Luxembourg, the regulator should have intervened.

It was also equally wholly unfitting to buy bonds in the other Icelandic banks: their credit default swap, CDS, spread made their bonds far from suitable for low-risk investments. – Interestingly, the administrator confirmed in the Paperjam interview 2012 that the loans were indeed invested in short-term bonds of Landsbanki and the two other banks: thus, there is no doubt that this was the case. – Only this fact per se, should have made the liquidator take a closer look at the time.

The value of the properties used as collaterals also raises questions. The sense is that the bank wanted to lend as much as possible to each and every borrower, thus putting a maximum value of the properties put up as collateral.

One of many intriguing facts regarding the Landsbanki Luxembourg equity release loans exposed in the French criminal case was when French borrowers told of getting loan documents in English and English borrowers of getting documents in French. As pointed out earlier on Icelog this seems to indicate a concerted effort by the bank to diminish clarity (at least in some cases, clients were promised they would get the documents in their language of choice, i.e. English borrowers getting documents in English, but the documents never materialised).

Again, this raises serious questions for the CSSF: did the bank adhere to MiFID rules at the time? And did the liquidator really see nothing worth reporting to the CSSF?

Landsbanki Luxembourg: opacity after its demise in October 2008

After Landsbanki Luxembourg failed in October 2008, Yvette Hamilius and Franz Prost were appointed liquidators for Landsbanki. Following Prost’s resignation in May 2009, Hamilius has been alone in charge. As the Court had originally appointed two liquidators the Court could have been expected to appoint another one after Prost resigned. That however was not the case. Not in Luxembourg. There have been some rumours as to why Prost resigned but nothing has been confirmed.

Be that as it may, the relationship between Hamilius and the borrowers has been a total misery for the borrowers. One of the things that early on led to frustration and later distrust were conflicting and/or unexplained figures in statements. Clarification, both on figures on accounts, and more importantly regarding the investments, was not forthcoming according to borrowers Icelog has heard from.

Hamilius’ opinion of the borrowers could be seen from the Paperjam interview in 2012 and from the remarkable statement from State Prosecutor Biever: the liquidator’s unflinching view was that the borrowers were simply trying to make use of the fact the bank had failed in order to save themselves from repaying the loans.

The interview and the statement from Biever came as a response to when a group of borrowers tried to take legal action against the Landsbanki Luxembourg and its liquidator. In the interview, Hamilius was asked if she was solely trying to serve the interest of Luxembourg as a financial centre, something she staunchly denied.

The action against Landsbanki Luxembourg has so far been unsuccessful, partly because Luxembourg lawyers are noticeably unwilling to take action against a bank, even a failed bank. In that sense, anyone trying to take action against a Luxembourg financial firm finds himself in a double whammy: the CSSF has proved to be wholly unsympathetic to any such claims and finding a lawyer may prove next to impossible.

Why was the investment part of the Landsbanki Luxembourg equity release loans killed off?

The key characteristic of equity release loans is that this product consists of a loan and investment, two inseparable parts. However, that proved not to be the case in the Landsbanki Luxembourg loans. Suddenly, after the demise of the bank, the borrowers found themselves to be debtors only, with the investment wiped out. This did fundamentally alter the situation for the borrowers.

The liquidator seems allegedly to have taken the stance that to a great extent, there was nothing to do about the investments in these cases where the bank had invested in Icelandic bank shares and bonds. That is an intriguing point: as pointed out earlier, the bank should never have been allowed to make these investments on behalf of these clients.

In Britain, as in many European countries, the law in general stipulates that if a lender fails, loans are not to be payable right away. As far as I can see, this counts for equity release loans as well: both parts of the loan should be kept going, the loan as well as the investment. Frequently, a liquidator sells off the package at a discount, for another company to administer, in order to be able to close the books of the failed bank.

This has not been the case in Landsbanki Luxembourg equity release loans, the investments were wiped out – and yet, Luxembourg authorities have paid no attention at all to the borrowers’ claims of unfair treatment by the liquidator.

As mentioned above, Hamilius’ version of the sorry saga is that the borrowers are simply unwilling to repay the loan.

The dirty deals of the Icelandic banks in Luxembourg

The recurrent theme in so many of the criminal cases in Iceland after the banking collapse 2008 against bankers and others related to the banks is the role of the banks’ subsidiaries in Luxembourg. The dirtiest parts of the deals were done through the Luxembourg subsidiaries (particularly noticeable in the Kaupthing cases). Since Hamilius has assisted investigations into Landsbanki in Iceland, she will be perfectly well aware of the Icelandic cases related to Landsbanki.

The administrators of the Icelandic banks in Iceland were crucial in providing material for the criminal proceedings in Iceland. Yet, as far as can be seen, the administrator has allegedly not deemed it necessary to take a critical look at the Landsbanki operations in Luxembourg. Which is why no questions regarding the equity release loans have been raised by the administrator with Luxembourg authorities.

The incredibly long winding-up saga at Landsbanki Luxembourg

One interesting angle of the winding-up of Landsbanki Luxembourg saga is the time it is taking. The administrators (winding-up boards) of the three large Icelandic banks, several magnitudes larger than Landsbanki Luxembourg, more or less finished their job in 2015, after which creditors took over the administration of the assets, mostly to sell them off for the creditors to recover their funds. The winding-up proceedings of LBI ehf., the estate of Landsbanki Iceland, came to an end in December 2015, when a composition agreement between LBI ehf. and its creditor became effective.

For some years now, the LBI ehf has been the only creditor of Landsbanki Luxembourg, i.e. all funds recovered by the liquidator go to LBI ehf. Formally, LBI ehf has no authority over the Landsbanki Luxembourg estate. Yet, it is more than an awkward situation since LBI ehf is kept in the waiting position, while the liquidator continues her actions against the equity release borrowers, whose funds are the only funds yet to be recovered.

That said, Luxembourg is not unused to long winding-up sagas. The fall of the Luxembourg-registered Bank of Credit and Commerce International, BCCI, in 1991, was one of the most spectacular bankruptcies in the financial sector at the time, stretching over many countries and exposing massive money laundering and financial fraud. Famously, the winding-up took well over two decades, depending on countries. Interestingly, Yvette Hamilius was one of several administrators, in charge of the process from 2003 to 2011; the winding-up was brought to an end in 2013.

The CSSF on a mission to protect its financial sector, not investors

Recently, another case has come up in Luxembourg that throws doubt on whose interest the CSSF mostly cares for: the financial sector it should be regulating or investors and deposit holders. A pertinent question, as pointed out in an article in the Financial Times recently (23 Feb., 2020), since Luxembourg is the largest fund centre in Europe, with €4.7tn of assets under management and gaining by the day as UK fund managers shift business from Brexiting Britain to the Duchy.

The recent case seems to rotate around three investment funds – Columna Commodities, Aventor and Blackstar Commodities – domiciled in Luxembourg, sub funds of Equity Power Fund. As early as 2016, the CSSF had expressed concern about the quality of the investments: astoundingly, 4/5 of the investments were concentrated in companies related to a single group. Lo and behold, this all came crashing down in 2017.

The investors smelled rat and contacted David Mapley at Intel Suisse, a financial investigator who specialises in asset recovery. Mapley has a success to show: in 2010 he won millions of dollars from Goldman Sachs on behalf of hedge funds, which felt cheated by the bank.

In order to gain insight into the Luxembourg operations, Mapley was appointed a director of LFP I, one of the investment funds in the Equity Power Fund galaxy. (Further on this story, see Intel Suisse press release August 2018 and coverage by Expert Investor in January and October 2019.)

According to the FT, the directors of LFP I claim the CSSF has not lived up to its obligation under EU law. They have now submitted a complaint against the CSSF to European Securities and Markets Authority, Esma, which sets standards and supervises financial regulators in the EU.

In a letter to Esma, Mapley states that the CSSF’s “marketing mission to promote Luxembourg as a financial centre” has undermined its focus on protecting investors. Mapley also alleges the CSSF has attempted to quash the directors’ investigations into mismanagement and fraud by the funds’ previous managers and service providers in order to undermine the funds’ efforts “and prevent any reputational risk”. – That is, the reputational risk of Luxembourg as a financial centre.

As FT points out, investors in a Luxembourg-listed fund that invested in Bernard Madoff’s $50bn Ponzi scheme have also accused the CSSF of leniency, i.e. sheltering the fraudster and not the investors.

Luxembourg, the stain on the EU that EU is unwilling to rub off

Worryingly, the CSSF’s lenient attitude might be more prominent now than ever as Luxembourg competes with other small European jurisdictions of equally doubtful reputation such as Cyprus and Malta (where corrupt politicians set about to murder a journalist, Daphne Caruana Galizia, investigating financial fraud; brilliant Tortoise podcast on the murder inquiry) in attracting funds leaving the Brexiting UK. Esma has been given tougher intervention powers, though sadly watered down from the original intension, in order to hinder a race to the bottom. It is very worrying that the EU does not seem to be keeping an eye on this development.

As long as this is the case, corrupt money enters Europe easily, with the damaging effect on competition, businesses, politics – and ultimately on democracy.

*Foreign currency loans, FX loans, have been covered extensively on Icelog, see here. For a European Court of Justice decision in the first FX loans case, see Árpád Kásler and Hajnalka Káslerné Rábai v OTP Jelzálogbank Zrt, Case C‑26/13.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Lessons from Iceland: the SIC report and its long lasting effect / 10 years after

The Bill passed by the Icelandic parliament in December 2008 on setting up an independent investigative commission, the Special Investigative Commission did not catch much attention at the time. The goal was nothing less than finding out the truth in order to establish events leading up to the 2008 banking collapse, analyse causes and drawing some lessons. The SIC report was an exemplary work and immensely important at the time to establish a narrative of the crisis. But in hindsight, there is yet another lesson to be learnt: its importance does not diminish with time as it helps to counteract special interests seeking to rewrite history.

There were no big headlines when on 12 December 2008 Alþingi, the Icelandic parliament, passed a Bill to set up an investigative commission “to investigate and analyse the processes leading to the collapse of the three main banks in Iceland,”which had shaken the island two months earlier. The palpable lack of enthusiasm and attention was understandable: the nation was still stunned and there was no tradition in Iceland for such commissions. No one knew what to expect, the safest bet was to not expect very much.

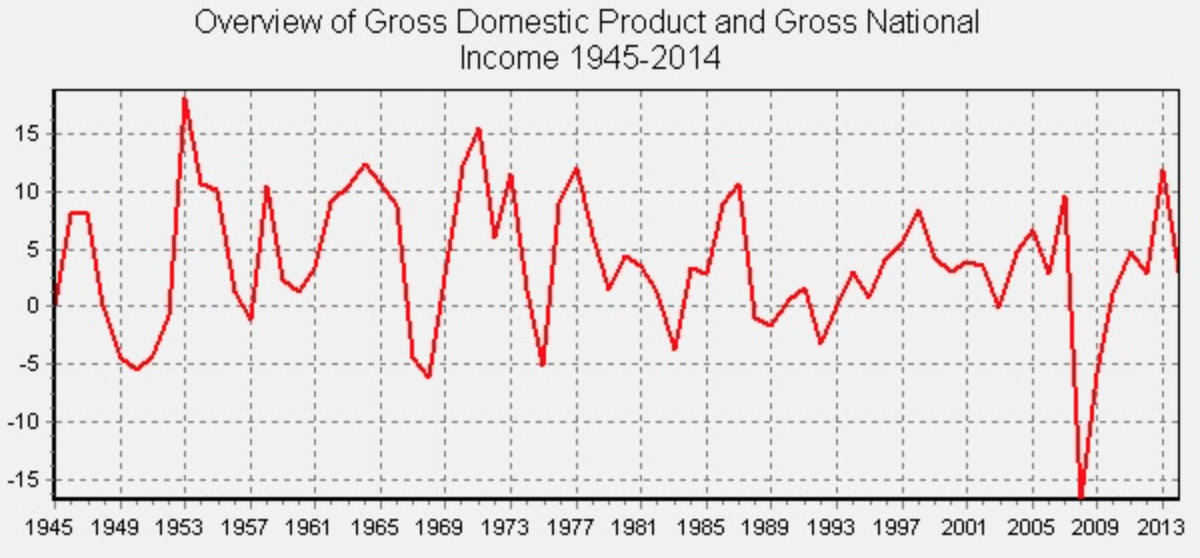

That all changed when the Commission presented its results in April 2010. Not only was the report long – 2600 pages in print in addition to online-only material – but it did actually tell the real story behind the collapse: the immensely rapid growth of the banks, from one GDP in 2002 to ten times the GDP in 2008, the stronghold the largest shareholders, incidentally also the largest borrowers, had on the banks’ managements, the political apathy and lax regulation by weak regulators, stemming from awe of the financial sector.

Unfortunately, the SIC report was not translated in full into English; see executive summary and some excerpts here.

With time, the report’s importance has not diminished: at the time, it clarified what had happened thus preventing those involved or others with special interest, to reshape the past according to their own interests. With time, hindering the reshaping of the past has become of major importance, also in order to draw the right lessons from the calamitous events in October 2008.

What was the SIC?

According to the December 2008 SIC Act (in Icelandic), the goal was setting up an investigative commission, that would, at the behest of Alþingi, seek “the truth about the run-up to and the causes of the collapse of the Icelandic banks in 2008 and related events. [The SIC] is to evaluate if this was caused by mistake or neglect in carrying out law and regulation of the financial sector in Iceland and its supervision and who could be held responsible for it.” – In order to fulfil its goal the SIC was inter alia to collect information on the financial sector, assess regulation or lack thereof and come up with proposals to prevent the repetition of these events.

In some countries, most notably in South Africa after apartheid, “Truth Commissions,” have played a major part in reconciliation with the past. Although the remit of the Icelandic SIC was to establish the truth, the SIC was never referred to as a “truth commission” in Iceland though that concept has been used in foreign coverage of the SIC.

The SIC had the power to make use of a vast array of sources, both by calling in people to be questioned and documents, public or private such as bank data, including data on named individuals, data from public institutions, personal documents and memos. Data, normally confidential, had to be shared with the SIC, which was obliged to operate as any other public body handling sensitive or confidential information.

Although the SIC had to follow normal procedures of discretion on personal data the SIC could “publish information, normally subject to discretion, if the SIC deems this necessary to support its conclusions. The Commission can only publish information on personal matters of named individuals, including their financial affairs, if the public interest is greater than the interest of the individuals concerned.” – In effect, this clause lift banking secrecy.

One source close to the process of setting up the SIC surmised the political intentions behind the SIC Act did not include lifting banking secrecy, indicating that the extensive powers given to the SIC were accidental. Others have claimed the SIC’s extensive powers were always part of the plan. I am in two minds about this but my feeling is that the source close to the process was right – the powers to scrutinise the main shareholders were far greater than intended to begin with.

Naming the largest borrowers, incidentally also the largest shareholders

Intentional or not, the extensive powers enabled naming the individuals who received the largest loans from the banks, incidentally their largest shareholders and their closest business partners. This was absolutely essential in order to understand how the banks had operated: essentially, as private fiefdoms of the largest shareholders.

In order to encourage those called in for questioning to speak freely, the hearings were held behind closed doors; there were no public hearings. The SIC had extensive powers to call people in for questioning: it could ask for a court order if anyone declined its invitation, with the threat of taking that person to court on grounds of contempt in case the invitation was declined.

Criminal investigation was not part of the SIC remit but its power to call for material or call in people for questioning was parallel to that of a prosecutor. As stated in the report, the SIC was obliged to inform the State Prosecutor if there was suspicion of criminal conduct:

The SIC’s assessment, pursuant to Article 1(1) of Act no. 142/2008, was mainly aimed at the activities of public bodies and those who might be responsible for mistakes or negligence within the meaning of those terms, as defined in the Act. Although the SIC was entrusted with investigating whether weaknesses in the operations of the banks and their policies had played a part in their collapse, the Commission was not expected to address possible criminal conduct of the directors of the banks in their operations.

As to suspicion of civil servants having failed to fulfil their legal duties, the SIC was supposed to inform appropriate instances. The SIC was not obliged to inform the individuals in question. As to ministers, the SIC was to follow law on ministerial responsibility.

The three members

The SIC Act stipulated it should have three members: the Alþingi Ombudsman, then as now Tryggvi Gunnarsson, an economist and, as a chairman, a Supreme Court Justice. The nominated economist was Sigríður Benediktsdóttir, then lecturer at Yale University (director of Financial Stability at CBI 2012 to 2016 when she returned to Yale). The chairman was Páll Hreinsson (since 2011 judge at the EFTA Court).

In addition to the Commission there was a Working Group on Ethics: Vilhjálmur Árnason professor of philosophy, Salvör Nordal director of the Centre for Ethics, both at the University of Iceland and Kristín Ástgeirsdóttir director of the Equal Rights Council in Iceland. Their conclusions were published in Vol. 8 of the SIC report.

In total, the SIC had a staff of around 30 people. As with the Anton Valukas report, published in March 2010, on the collapse of Lehman Brothers, organising the material, especially the data from the banks, was a major task. The SIC had access to the databases of the three collapsed banks but had only limited data from the banks’ foreign operations.

There were absolutely no leaks from the SIC, which meant it was unclear what to expect. Given its untrodden path, the voices expressing little faith were the most frequently heard. I had however heard early on, that the SIC had a firm grip on turning material into searchable databases, which would mean a wealth of material. With qualified members and staff, I was from early on hopeful that given their expertise of extracting and processing data the SIC report would most likely prove to be illuminating – though I certainly did not imagine how extensive and insightful it turned out to be.

Greed, fraud and the collapse of common sense

After the October 2008 collapse, my attention had been on some questionable practices that I heard of from talking to sources close to the failed banks.

One thing I had quickly established was how the banks, through their foreign subsidiaries, had offshorised their Icelandic clients. This counted not only for the wealthy businessmen who obviously understood the ramifications of offshorising but also people with relatively small funds. These latters had in many cases scant understanding of these services.

In the last few years, as information on offshorisation has come to the light via Offshoreleaks etc., it has become clear that Iceland was – and still is – the most offshorised country in the world (here, 2016 Icelog on this topic). Once the “art” of offshorisation is established, with all the vested interests accompanying it, it does not die easily – this might be considered one of the failed banks’ more evil legacies.

Another point of interest was how the banks had systematically lent clients, small and large, funds to buy the banks’ own shares, i.e. Kaupthing lent funds to buy Kaupthing shares etc. Cross-lending was also a practice: Bank A would lend clients to buy Bank B shares and Bank B lent clients to buy Bank A shares. This was partly used to hinder that shares were sold when buyers were few and far behind, causing fall in market value. In other words, massive market manipulation had slowly been emerging. Indeed, the managers of all three failed banks have in recent years been sentenced for market manipulation.

It had also emerged, that the banks’ largest shareholders/clients and their business partners had indeed been what I have called “favoured clients,” i.e. enjoying services far beyond normal business practices. One side of this came to light in the banks’ covenants in lending agreements: in the case of the “favoured clients,” the lending agreements tended to guarantee clients’ profit, leaving the banks with the losses. In other words, the banks took on far greater portion of the risk than these clients.

Icelog blogs I wrote in February 2010, before the publication of the SIC report, give some sense of what was known at the time. Already then, it seemed fair to conclude that greed, fraud and the collapse of common sense had been decisive factors in the event in Iceland in October 2008.

Monday morning 12 April 2010 – when time stood still in Iceland

The excitement in Iceland on Monday morning 12 April 2010 was palpable. The press conference was transmitted live. All around Iceland employers had arranged for staff to watch as the SIC presented its conclusions.

After Páll Hreinsson’s short introduction, Sigríður Benediktsdóttir gave an overview of the main findings regarding the banks, presenting “The main reasons for the collapse of the banks,” followed by Tryggvi Gunnarsson’s overview of the reactions within public institutions (here the presentations from the press conference, in Icelandic).

The main reason for the collapse of the three banks was their rapid growth and their size at the time they collapsed; the three big banks grew 20-fold in seven years, mainly 2004 and 2005; the rapid expansion into new/foreign markets was risky; administration and due diligence was not in tune with the banks’ growth; the quality of loans greatly deteriorated; the growth was not in tune with long-time interest of sound banking; there were strong incentives within the banks grow.

Easy access to short-term lending in international markets enabled the banks’ rapid growth, i.e. the banks’ main creditors were large international banks. With the rapid expansion, also abroad, the institutional framework in Iceland, inter alia the Central Bank and the FME, quickly became wholly inadequate. The under-funded FME, lacking political support, was no match for the banks, which systematically poached key staff from the FME. Given the size of the humungous size of the Icelandic financial system relative to GDP there was effectively no lender of last resort in Iceland; the Central Bank could in no way fulfil this role.

This had no doubt be clear to the banks’ management for some time. In his book, “Frozen Assets,” published in 2009, Ármann Þorvaldsson, manager of KSF, Kaupthing’s UK operation, writes that he “always believed that if Iceland ran into trouble it would be easy to get assistance from friendly nations… despite the relative size of the banking system in Iceland, the absolute size was of course very small.” (P. 194). – A breath-taking recklessness, naivety or both but might well have been the prevalent view at the highest echelons of the Icelandic financial sector at the time.

The banks’ largest shareholders and their “abnormally easy access to lending”

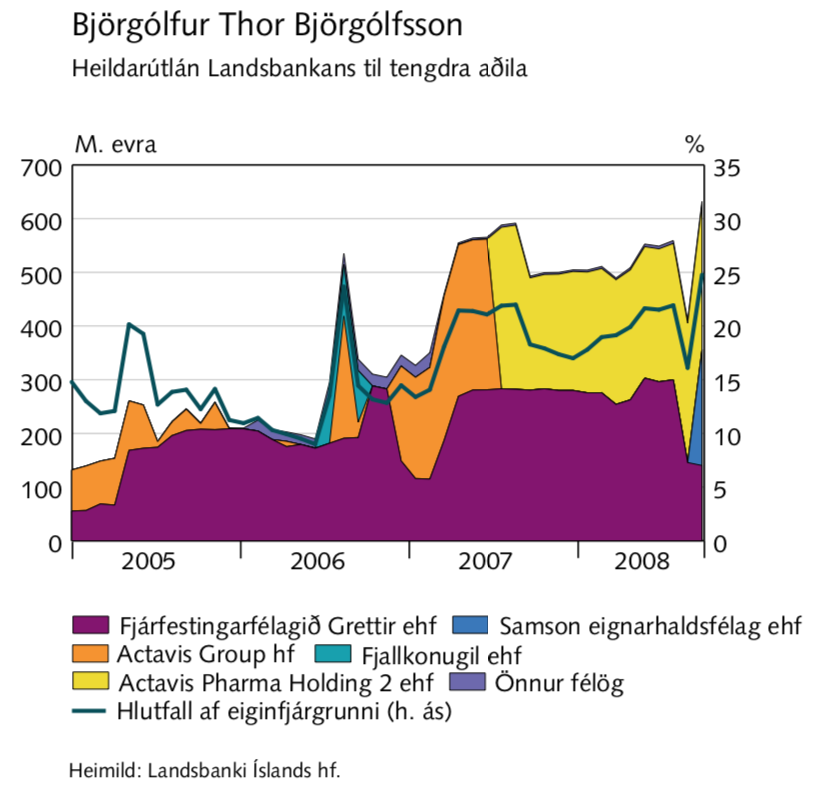

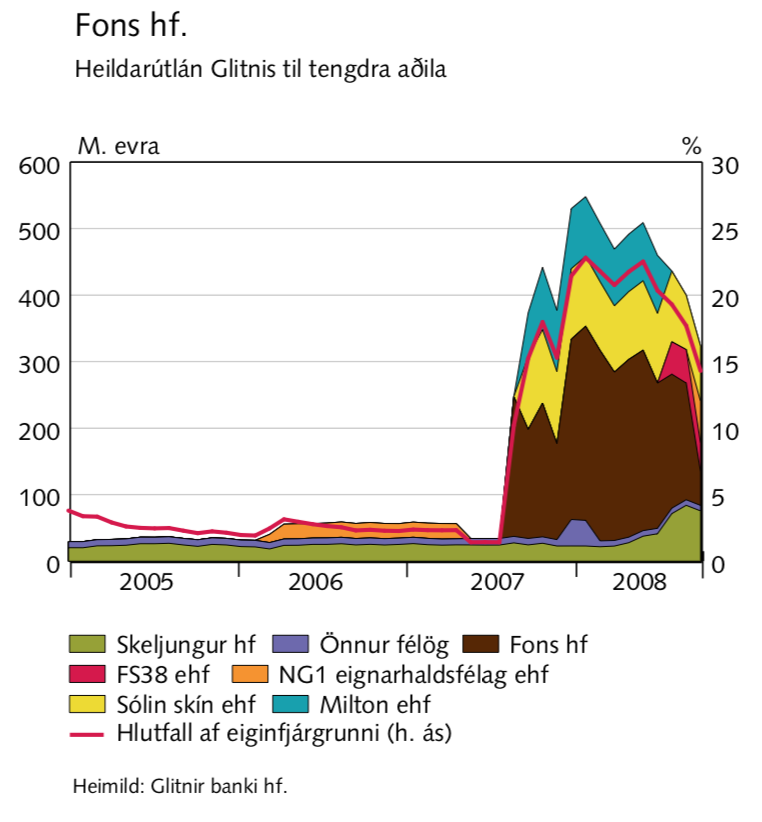

When it came to “Indebtedness of the banks’ largest owners” the conclusions were truly staggering: “The SIC concludes that the owners of the three largest banks and Straumur (investment bank where the main shareholders were the same as in Landsbanki, i.e. Björgólfur Thor Björgólfsson and his fater) had abnormally easy access to lending in these banks, apparently only because their ownership of these banks.”

The largest exposures of the three large banks were to the banks’ largest shareholders. “This raises the question if the lending was solely decided on commercial terms. The banks’ operations were in many ways characterised by maximising the interest of the large shareholders who held the reins rather than running a solid bank with the interest of all shareholders in mind and showing reasonable responsibility towards shareholders.” – Creative accounting helped the banks to avoid breaking rules on large exposures.

Benediktsdóttir showed graphs to illustrate the lending to the largest shareholders in the various banks. It is worth keeping in mind that these large shareholders all had foreign assets and were all clients of foreign banks as well. In general, the Icelandic lending shot up in 2007 when international funding dried up. At this point, the Icelandic banks really showed how favoured the large shareholders were because these clients were, en masse, getting merciless margin calls from their foreign lenders.

In reality, the Icelandic banks were at the mercy of their shareholders. If the large shareholders and/or their holding companies would default, the banks themselves were clearly next in line. The banks could not make margin calls where their own shares were collateral as it would flood the markets with shares no one wanted to buy with the obvious consequence of crashing share prices.

Two of the graphs from the SIC report, shown at the press conference in April 2010, exposed the clear drift in lending at a decisive time: to Björgólfur Thor Björgólfsson, still an active investor based in London and to Fons, a holding company owned by Pálmi Haraldsson, who for years was a close business partner of Jón Ásgeir Jóhannesson, once a king on the UK high street with shops like Iceland, Karen Millen, Debenhams and House of Fraser to his name.

The lending related to Fons/Haraldsson is particularly striking since Haraldsson was part of the consortium Jóhannesson led in spring of 2007 to buy around 40% of Glitnir: after the consortium bought Glitnir, the lending to Haraldsson shot up like an unassailable rock.

Absolution of risk

The common thread in so many of the SIC stories was how favoured clients – and in some cases bank managers themselves – were time and again wholly exempt from risk. One striking example is an email (emphasis mine), sent by Ármann Þorvaldsson and Kaupthing Luxembourg manager Magnús Guðundsson, jokingly calling themselves “associations of loyal CEOs,” to Kaupthing’s chairman Sigurður Einarsson and CEO Hreiðar Sigurðsson.

“Hi Siggi and Hreidar, Armann and I have discussed this (association of loyal CEOs) and have come to the following conclusion on our shares in the bank: 1. We set up a SPV (each of us) where we place all shares and loans. 2. We get additional loans amounting to 90% LTV or ISK90 to every 100 in the company which means that we can take out some money right away. 3. We get a permission to borrow more if the bank’s shares rise, up to 1000. It means that if the shares go over 1000 we can’t borrow more. 4. The bank wouldn’t make any margin calls on us and would shoulder any theoretical loss should it occur.We would be interested in using some of this money to put into Kaupthing Capital Partners [an investment fund owned by the bank and key managers] Regards Magnus and Armann”

This set-up, where the borrower is risk-free and the bank shoulders all the risk, has lead to several cases where bankers being sentenced for breach of fiduciary duty, i.e. lending in such a way that it was from the beginning clear that losses would land with the bank. (Three of these Kaupthing bankers, Guðmundsson, Einarsson and Sigurðsson, not Þorvaldsson, have been charged and sentenced in more than one criminal case).

The “home-knitted” crisis

Due to measures taken in October 2008 in the UK against the Icelandic banks, there was a strong sense in Iceland that the Icelandic banks had collapsed because of British action. The use of anti-terrorism legislation by the British government against Landsbanki greatly contributed to these sentiments.

A small nation, far away from other countries, Icelanders have a strong sense of “us” and “the others.” This no doubt exacerbated the understanding in Iceland around the banking collapse that if it hadn’t been for evil-meaning foreigners, hell-bent on teaching Iceland a lesson, all would have been fine with the banks. Some leading bankers and large shareholders were of the opinion that Icelanders had been such brilliant bankers and businessmen that they had aroused envy abroad: British action was a punishment for being better than foreign competitors (yes, seriously; see for example Þorvaldsson’s book “Frozen Assets”).

The story told in the SIC report showed convincingly and in great detail how wrong all of this was: the banks had dug their own grave. Icelandic politicians and civil servants had tried their best to fool foreign countries and institutions how things stood in Iceland. Yes, the turmoil in international markets toppled the Icelandic banks but they were weak due to bad governance, great pressure by the largest shareholders and then weak infrastructure in Iceland, as I pointed out in a blog following the publication of the SIC report.

This understanding is at times heard in Iceland but the convincing and well-documented story told in the SIC report has slowly all but eradicated this view.

Court cases and political controversies

Some, but by far not all, of the dubious deals recounted in the SIC report have ended up in court. The SIC brought a substantial amount of cases deemed suspicious to the attention of the Office of Special Prosecutor, incidentally set up by law in December 2008. However, most if not all of these cases had also been spotted by the FME, which passed them on to the Special Prosecutors.

CEOs and managers in all three banks have been sentenced in extensive market manipulation cases – the bankers were shown to have directed staff to sell and buy shares in a pattern indicating planned market manipulation. In addition, there have been cases involving shareholders, most notably the so-called al Thani case (incidentally strikingly similar to the SFO case against four Barclays bankers) where Ólafur Ólafsson, Kaupthing’s second largest shareholder, was sentenced to 5 1/2 years in prison, together with the bank’s top management.

In total, close to thirty bankers and major shareholders have been sentenced in cases related to the old banks, the heaviest sentence being six years. The cases have in some instances thrown an interesting light on operations of international banks, such as the CLN case on Deutsche Bank.

The SIC’s remit was inter alia to point out negligence by civil servants and politicians. It concluded that the Director General of the FME Jónas Fr. Jónsson and the three Governors of the CBI, Davíð Oddsson, Eiríkur Guðnason and Ingimundur Friðriksson, had shown negligence as defined in the law “in the course of particular work during the administration of laws and rules on financial activities, and monitoring thereof.” – None of them was longer in office when the report was published in April 2010 and no action was taken against them.

The Commission was of the opinion that “Mr. Geir H. Haarde, then Prime Minister, Mr. Árni M. Mathiesen, then Minister of Finance, and Mr. Björgvin G. Sigurðsson, then Minister of Business Affairs, showed negligence… during the time leading up to the collapse of the Icelandic banks, by omitting to respond in an appropriate fashion to the impending danger for the Icelandic economy that was caused by the deteriorating situation of the banks.”

It is for Alþingi to decide on action regarding ministerial failings. After a long deliberation, Alþingi voted to bring only ex-PM Geir Haarde to court. According to Icelandic law a minister has to be tried by a specially convened court, which ruled in April 2012 that the minister was guilty of only one charge but no sentence was given (see here for some blogs on the Haarde case). Geir Haarde brought his case to the European Court of Human Rights but the judgment went against him. Haarde is now the Icelandic ambassador in Washington.

The SIC lacunae

In hindsight, the SIC was given too short a time. With some months more, the role of auditors in the collapse could for example have been covered in greater detail. It is quite clear that the auditing was far too creative and far too wishful, to say the very least. The relationship between the banks and the four large international auditors, who also operate in Iceland, was far too cosy bordering on the incestuous.

The largest gap in the SIC collapse story stems from the fact that the SIC had little access to the banks foreign operations. Greater access would not necessarily have altered the grand narrative. But court cases have shown that some of the banks’ criminal activities, were hidden abroad, notably in the case of Kaupthing Luxembourg. – As I have time and again pointed out, it is incomprehensible that authorities in Luxembourg have not done a better job of investigating the banking sector in Luxembourg. The Icelandic cases are a stern reminder of this utter failure.

As mentioned above, only excerpts of the report were translated into English. To my mind, this was a big error and extremely short-sighted. Many of the stories in the report involve foreign banks and foreign clients of the Icelandic banks. The detailed account of what happened in Iceland throws light on not only what was going on in Iceland but also in other countries where the banks operated. The excerpts are certainly better than nothing but by far not enough – publishing the whole report in English would have done this work greater justice and been extremely useful in a foreign context.

Why the SIC report’s importance has grown with time

It is now just over eight years since the publication of the SIC report. Whenever something related to the collapse is discussed the report is a constant source and the last verdict. The report established a narrative, based on extensive sources, both verbal and written.

Some of those mentioned in the report did not agree with everything in the report. When they sent in their own reports these have been published on-line. However, undocumented statements amount to little compared to the report’s findings. Its narrative and conclusions can’t be dismissed without solid and substantiated arguments to counter its well-documented conclusions.

This means the story of the 2008 banking collapse cannot easily be reshaped. This is important because changing the story would mean undermining its conclusions and lessons to be learnt. In a recent speech, Tory MP Tom Tugendhat mentioned the UK financial crisis as the “forces of globalisation.” These would be the same forces that caused the collapse of the Icelandic banks – but from the SIC report Icelanders know full well that this is far too imprecise a description: the banks, both in the UK and Iceland, collapsed due to lack of supervision and public and political scrutiny, following year of lax policies.

Lessons for other countries

In order to learn from the financial crisis, countries need to know why there was a crisis – with no thorough analysis no lessons can be learnt. Also, not only in Iceland was criminality part of the crisis. Though not a criminal investigation, many of these stories surfaced in the SIC report, another important aspect.

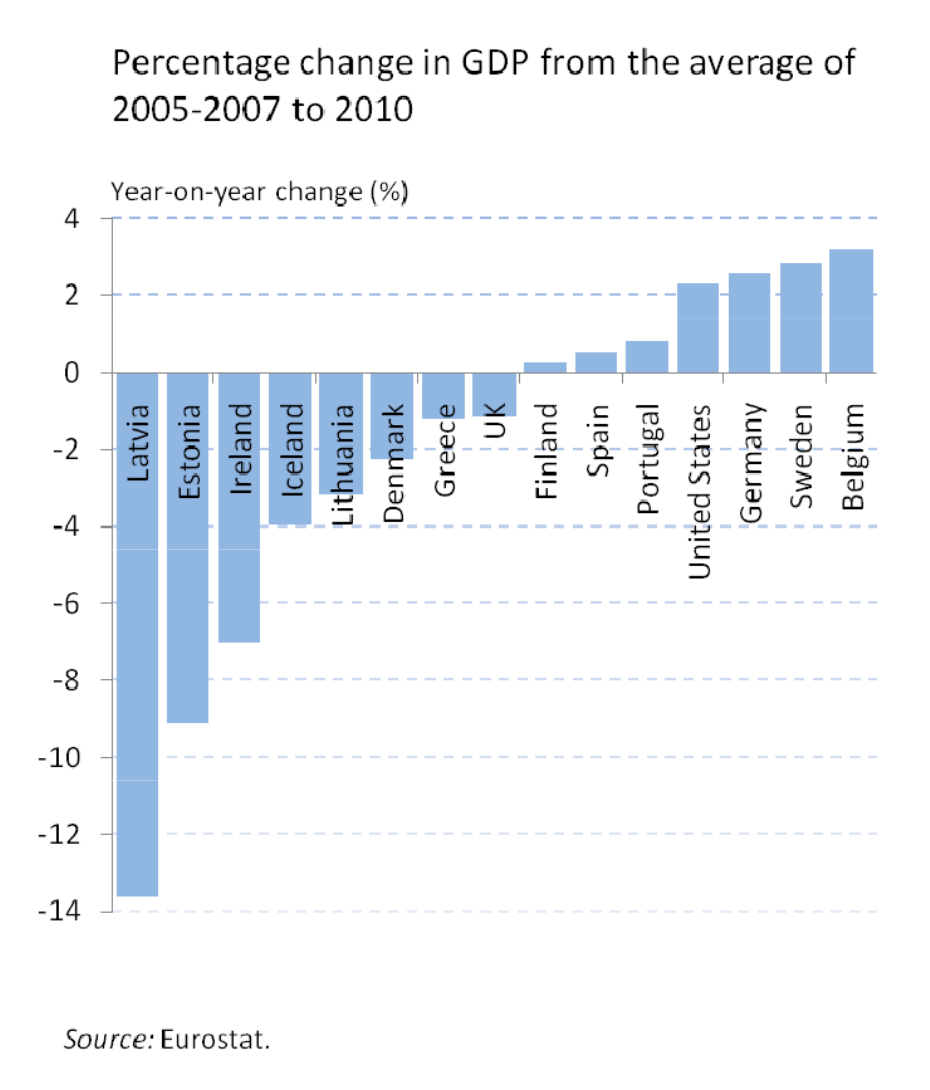

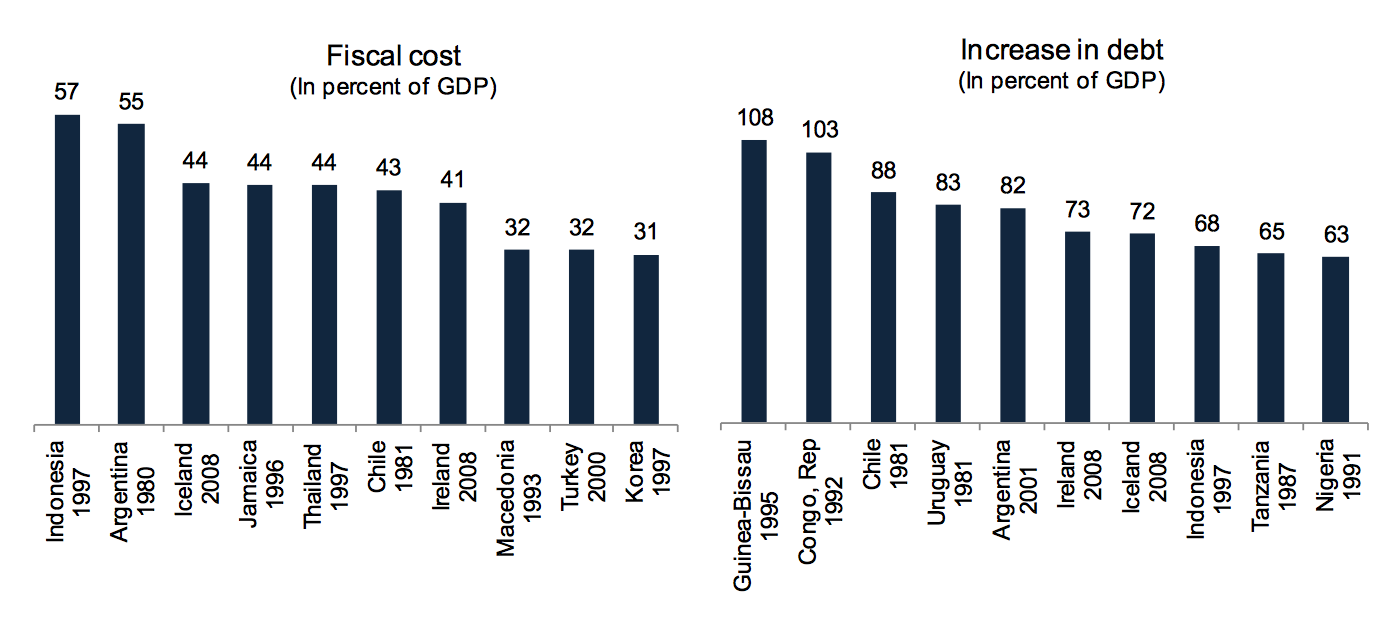

Greece, Cyprus, UK, Ireland, US – five countries shaken and upset by overstretched banks, which needed to be bailed out at great expense and pain to taxpayers. However, all of these countries have kept their citizens in the dark as to what happened apart from some tentative and wholly inadequate attempts. The effect of hiding how policies and actions of individuals, in politics, banking etc, caused the calamities has partly been the gnawing discontent and lack of trust, i.a. visible in Brexit and the election of Donald Trump as US president.

Although Iceland enjoyed a speedy recovery (Icelog Sept. 2015), I’m not sure there are any particular economic lessons to be learned from Iceland. There were no magic solutions in Iceland. What contributed to a relatively speedy recovery was the sound state of the economy before the crisis, classic but unavoidably painful economic measures, some prescribed by the IMF, in 2008 and the following years – and some luck. If there is however one lesson to learn it is the importance of a thorough analysis of the causes of the crisis.

The SIC was, and still is, a shiny example of thorough investigative work following a major financial crisis, also for other countries. It did not alleviate anger; anger is still lingering in Iceland. An investigative report is not a panacea, nothing is, but it is essential to establish what happened and why, with names named.

There are never any mystical “forces” or laws of nature behind financial crisis and collapse. They are caused by a combination of human actions, which can all be analysed and understood. Without analysis and investigations it is easy to tell the wrong story, ignore the causes, ignore responsibility – and ultimately, ignore the lessons.

This is the second blog in “Ten years later” – series on Iceland ten years after the 2008 financial collapse, running until the end of this year.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

The Trump saga in the grand scheme of Russian influence

During the Cold War, both the United States and the Soviet Union used various ways to influence political leaders and decision makers all over the world. Parts of the Soviet power structure, most notably of the KGB, live on in Russia. Three angles are of interest: 1) Vladimir Putin’s Russia has for years sought to influence the West via Nord Stream. 2) Admiration of Putin as the strong man thrives on the far Right in Europe and elsewhere. 3) The evolving saga of US president Donald Trump’s Russian ties might show a new side of Russian influence if it turns out that the Trump empire did receive Russian funds in its hour of need. – In addition, the Magnitsky Act proves to be an intriguing prism on Russian influence in the West.

Nord Stream and Nord Stream 2

The planning of a Russian gas pipeline from Russia to Europe started in the 1990s. It happened in an atmosphere of uncertainty following the collapse of the Soviet Union as to how the Russian relationship with the democratic West could or would develop. Some even thought Russia could join the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation, Nato.

From the beginning, Nord Stream was developed within and closely related to Gazprom, the Russian state-owned natural gas company founded in 1989 and a key factor in the Russian power structure. The first concrete step towards the pipeline was taken in 1997 but in 2005, the year the construction started, Nord Stream AG was incorporated in Zug, Switzerland. Gazprom has had various partners over the years but it still holds 51% of the shares.

In the countries affected by Nord Stream – Poland, the Baltic states, Finland, Sweden, Denmark and Germany – the effect of the pipeline in terms of environmental effect, national security, energy security and political influence has been a hotly debated topic all these years.

The pipeline was ceremoniously inaugurated in 2011 by Russian president Dmitry Medvedev, German Chancellor Angela Merkel and French Prime Minister Francois Fillon. Nord Stream 2 is now being planned.

Nordstream has always been about “Russia’s pipeline power” as Edoardo Saravelle at the Center for a New American Security wrote recently: Russia’s attempt to influence the US reaches far beyond attempting to influence the US presidential elections. “The pipeline is a naked Russian attempt to divide and conquer Europe. What makes the Kremlin so clever, and this effort so insidious, is that Gazprom has engineered an attractive business case for the project for a number of European gas importers,” writes Saravelle.

Due to the geo-political dimension of Nord Stream not only politicians and voters in the affected countries were interested in the Nord Stream development but also US politicians.

The Nord Stream effect

As German Chancellor 1998 to 2005, the social democratic leader Gerhard Schröder showed to begin with little liking for Boris Yeltsin’s Russia. That changed when Vladimir Putin, fluent in German after living there as a KGB agent, rose to power. One sign of Schröder’s strong ties to Russia was his enthusiasm for the Baltic gas pipeline and Nord Stream. One of Schröder’s last acts in office was to agree to a state guarantee of €1bn for part of the Nord Stream construction cost.

Only weeks after stepping down as Chancellor, Schröder accepted the Nord Stream offer to become head of the shareholder group of Nord Stream AG, a post he still holds. Not only Germans were shocked. Washington Post wrote an editorial on what the paper called Schröder’s “Sellout” – Democrat Congressman Tom Lantos, a holocaust survivor who died in 2008, chair of the House of Representatives foreign relations committee said that Schröder’s close ties to the Russian energy sector was “political prostitution.”

Equally, it shocked many Fins in 2008 when their social democratic Prime Minister 1995 to 2003 Paavo Lipponen became a Nord Stream consultant. A year later, Poland blocked Lipponen from being put forward as EU foreign policy chief because of his work for Nord Stream.

The new US sanctions against Russia enjoy a large bipartisan support in spite of Trump’s opposition. The new sanctions threaten to hit European companies working on the Nord Stream 2 joint venture with Russia, a major headache for the EU.

The far Right admiration for Putin

As social democrats and in spite of their ties to Putin’s Russia, both Schröder and Lipponen have been advocates of a strong and united Europe Union. But over the last decade or so, many far Right politicians in Europe and the US have shown great sympathy and even admiration for Putin.

Wholly ignoring the dismal state of the Russian economy under Putin and no matter his decidedly undemocratic and despotic tendencies many on the far Right seem to admire him as a strong leader. They have swallowed Putin’s own portrayal of himself, utterly ignoring that Putin’s iconography is unattached to reality.

The French leader of Front National Marine Le Pen and UKIP’s Nigel Farage are part of the Putin fan club. As is Republican congressman of California, Dana Rohrabacher who met with Putin in the 1990s and is known as one of Putin’s staunchest allies on Capital Hill, according to a May 2017 New York Times article.

This may well be a question of values but it can also be interpreted as flirting with an autocratic rule, characterised by “Constraints on the press, centralisation of power and various elements of nationalism” combined “with a backlash against progressive ideals and globalisation” as Olga Oliker expressed it in an article for International Institute for Strategic Studies, IISS.

Trump: more than a political admirer of Putin?

Donald Trump has shown the same admiration for Putin and autocratic rule as many on the far Right though Trump can in many ways not entirely be defined as a far Right; his vision is too rambling to show a single direction.

During his electoral campaign Donald Trump certainly flirted with ideas of autocratic rule: the idea that the president could do this and that unhampered by the House and the Senate, his many utterances against the media, his nationalistic stance and emphasis on US first, his disdain of international agreement and free trade.

Same tendencies can be found in his words and actions, or attempts to action, as president. And he does not hold back in his admiration for Putin as a person and a leader.

Last year, Republican Congressman and the House majority leader Kevin McCarthy was caught on tape saying: “There’s two people I think Putin pays: Rohrabacher and Trump.” McCarthy now says this was only a poor joke. However, indications of a much more direct Russian Trump connection than only an ideological dallying with anti-democratic ideas have now led to the investigation led by Richard Mueller.

Make Russia great again

Former National Intelligence Director James Clapper recently said that Trump’s actions were “making Russia great again.” – There is a certain irony that a US President who got voted on the slogan Make America Great Again is now being investigated for Russian ties – and one does not need Cold War glasses to understand the severity of the allegations.

But in many ways, Trump is only the icing on a Russian pie, rich of intriguing Russian ties to Washington DC. There is Rohrabacher, as mentioned earlier. Unconnected to Trump and not under investigation as far as is known, Trump’s Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross has a particular interesting history of Russian relations. Ross led a group of investors recapitalising Bank of Cyprus in 2014, a year after a financial crisis shook the island, a safe haven for Russian money. Ross ousted some Russians from the board, leading to speculations he was not at all a friend of Russia.

However, Viktor Vekselberg, seen as central part of Putin’s financial empire, is now the largest single shareholder in Bank of Cyprus with a representative on the board. Ross appointed Joseph Ackerman, CEO of Deutsche Bank 2002 to 2012, as a chairman of the board of Bank of Cyprus. Deutsche Bank was so active in Russia in the 1990s that one source told me the bank should have been called Russische Bank. In January 2017 Deutsche was fined $630m for having laundered $10bn on behalf of Russians.

As sources indicate that Attorney General Jeff Sessions met Russian officials during the Trump campaign in spite of his earlier categorical denials Sessions is now under renewed pressure to testify again. Then there are the contacts Trump’s son-in-law and advisor Jared Kushner and Trump’s son Donald Junior had with Russians. Paul Manafort and Michael Flynn lost their jobs due to Russian ties. (See here a Washington Post overview over Team Trump and its Russian connections.)

Burt and his network

Richard Burt, a former journalist, US Ambassador in Federal Republic of Germany 1985 to 1989 during the Reagan administration and a known lobbyist for Russian interests, is one of those who have suddenly been swept into the limelight because of the investigation into Trump’s Russian connections.

Burt has confirmed that he was present at two dinners hosted by Jeff Sessions during the 2016 campaign. Sessions had explicitly denied having met any lobbyists working on behalf of the Russians. Burt said to the Guardian that Sessions possibly did not know of his activities though they are widely known in Washington.

It now seems certain that Sessions met Sergey Kislyak, who until recently was the Russian Ambassador to the US, at an event in April 2016 at the Mayflower Hotel, hosted by the magazine The National Interest in Washington. At this event Trump delivered his first major speech on foreign affairs. Burt was an adviser on that speech but has said little from his notes was taken up in the speech.

An article in April this year in The National Interest, published by the think tank Center for the National Interest where Burt is on the board, gives an idea of Burt’s view on Russia. In “A Grand Strategy for Trump” Burt advocates that a US military build-up could incentivise Russia “to seek a more productive relationship with the West.” Other steps would be “finding a settlement in Ukraine, examining ways to cooperate in fighting ISIS, and addressing a new agenda of military threats and non-proliferation.”

The problem, according to Burt, is the “current Russiagate mania” “a partisan and increasingly hysterical debate in Washington over what, if anything, the Trump campaign did to assist Russian hackers in intervening in the 2016 elections.” Quoting Henry Kissinger that “demonizing Putin is not a strategy” Burt then asks: “if the United States gave up, at least for now, its twenty-five-year-old policy of turning Russia into a Western-style democracy, but instead focused on the external threats it poses, would a more politically secure Kremlin be prepared to respond positively?”

Burt is a managing director at McLarty Associates, previously part of Kissinger McLarty Associates. In his role at McLarty he has been a lobbyist for Nord Stream II. In addition he is on the board of Deutsche Bank closed-end funds. He has also been an adviser for Alfa Capital Partners, the investment arm of Alfa Bank, operating in Russia, the Netherlands, UK, Belarus, Ukraine and Kazakhstan.

The Group’s largest investor, holding 32.8%, is Mikhail Fridman, the Ukrainian oligarch who over the years has managed to distance himself from Russia and Kremlin with his wealth intact in spite of some skirmishes: Fridman was forced to sell his stake in the oil company TNK-BP, the Russian joint venture with the BP, to the Kremlin controlled Rosneft but he apparently got a full price in cash at the top of the cycle, according to a Forbes in November 2016, written when Alfa had become part of … yes, the Trump story.

Incidentally, Gerhard Schröder sat for a while on the board of the TNK-BP. And Deutsche Bank has over the years been the largest lender to the Trump empire.

The Magnitsky prism: what does it mean talking about adoption?

“It was not a long conversation, but it was, you know, could be 15 minutes. Just talked about — things. Actually, it was very interesting, we talked about adoption… We talked about Russian adoption. Yeah. I always found that interesting. Because, you know, he (Putin) ended that years ago. And I actually talked about Russian adoption with him, which is interesting because it was a part of the conversation that Don [Jr., Mr. Trump’s son] had in that meeting.” – This is how Trump described his tête-à-tête with Putin at the G20 dinner in July in a New York Times interview.

Talking about adoption sounds very innocent – except the context is less so: Putin put an end to Americans adopting Russian children in retaliation to the Sergei Magnitsky Rule of Law Accountability Act, passed in the US in 2012. Only now is a similar act finding its way into UK law in the Criminal Finance Bill. Similar law is being passed in Canada, Estonia has already its Magnitsky Act and it has been discussed in the EU.

The hedge fund manager Bill Browder hired Magnitsky as his lawyer but after exposing $230m tax fraud enriching Putin and his cohort, Magnitsky was imprisoned in Moscow in autumn 2008 and died from torture in prison a year later. Browder’s book “Red Notice” (2015) is a horrifying exposé of the whole fraud saga leading to Magnitsky’s death.

As Browder explained in a recent interview, Kremlin pays the lawyer Natalia Veselnitskaya and others millions to lobby against the Magnitsky Act. In addition to being Browder’s nemesis in fighting the Magnitsky Act she has represented Russians, with ties to Kremlin, who had their assets frozen by the US Department of Justice frozen due to the Act.

In general, corrupt politicians and officials need to get their funds abroad in order to be able to make use of these funds to pay bribes, invest etc. An essential part of corruption is of course that it is hidden and those who operate by corrupt means operate through others. With funds abroad they can promise the helpers impunity and payment abroad.

Putin, often estimated to be the richest man in the world, is no exception: if the flow of funds abroad is hindered his power is seriously diminished. The Magnitsky Act hits this flow and has exposed Putin’s Achilles heal.

Trump’s interest in adoption relates directly to the campaign against the Magnitsky Act, exposes the Russian enablers and the extensive Russian attempts to influence US politics, ultimately a serious threat to the security of the West and rule of law and democracy.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Iceland, Russia and Bayrock – some facts, less fiction

Contacts between Iceland and Russia have for almost two decades been a source of speculations, some more fancifully than others. The speculations have now again surfaced in the international media following the focus on US president Donald Trump and his Russian ties: part of that story involves his connections with Bayrock where two Icelandic companies, FL Group and Novator, are mentioned. Contrary to the rumours at the time, Icelandic expansion abroad up to the banking collapse in 2008 can be explained by less sensational sources than Russian money – but there are some Russian ties to Iceland.

“We have never seen businessmen who operate like the Icelandic ones, throwing money around as if funding was never a problem,” an experienced Danish business journalist said to me in 2004. From around 2002 to the Icelandic banking collapse in October 2008, the Icelandic banks and their largest shareholders attracted attention abroad for audacious deals.

The rumours of Russian links to the Icelandic boom quickly surfaced as journalists and others sought to explain how a tiny country of around 320.000 people could finance large business deals by Icelandic businesses abroad. The owners of one of Iceland’s largest banks, Landsbanki, father and son Björgólfur Guðmundsson and Björgólfur Thor Björgólfsson, had indeed become rich in Saint Petersburg in the 1990s.

The unequivocal answer on how the foreign expansion of Icelandic banks and businesses was funded came in the Special Investigative Commission Report, SICR, in 2010: the funding came from Icelandic and international banks; the Icelandic banks found easy funding on international markets, the protagonist were at the same time the banks’ largest shareholders and their largest borrowers.

The rumours of Russian connections have surfaced again due to the Bayrock saga involving US president Donald Trump and his relations to Russia and Russian mobsters. Time to look at the Icelandic chapter in the Bayrock saga and Russian Icelandic links.

The Bayrock saga

By now, there is hardly a media company in the world that has not paid some attention to Donald Trump and Bayrock, with a mention of the Icelandic FL Group and the Russian money in Icelandic banks and businesses. The short version of that saga is the following:

Tevfik Arif, born in Kazakhstan during the Soviet era, was a state-employed economist who turned to hotel development in Turkey in the 1990s before moving into New York property development where he founded Bayrock in 2001. As with many real estate companies Bayrock’s structure was highly complex with myriad companies and shell companies, on- and offshore.

Arif hired a Russian to run Bayrock. Felix Sater or Satter was born in Russia in but moved to New York as youngster with his family. In 1991 Sater was sentenced to prison for a bar brawl cutting up the face of his adversary with a broken glass. Having admitted to security fraud in cohort with some New York Mafia families in 1998 he was eventually found guilty but apparently got a lenient sentence in return for becoming an informant for the law enforcement.

In 2003, Arif and Sater were introduced to a flamboyant property developer by the name of Donald Trump, already a hot name in New York. One of their joint projects was the Trump Soho. The Trump connection did attract media attention. Apparently following a New York Times profile of Sater in December 2007, unearthing his criminal records, Arif dismissed Sater in 2008.

Bayrock and FL Group

By then, another scheme was brewing and that is where the Icelandic FL Group enters the Bayrock and Trump story. This part of the story has surfaced in court cases, still ongoing, where two ex-Bayrock employees, Jody Kriss and Michael Ejekam, are suing Bayrock for cheating them of profit inter alia from the Trump SoHo deal.

Their story details complicated hidden agreements whereby Arif and Sater, according to Kriss and Ejekam, essentially conspired to skim off profit from Bayrock, cheating everyone who entered an agreement with them. According to the story told in the court documents (see inter alia here) Bayrock entered an agreement with FL Group in May 2007: for providing a loan of $50m FL Group would get 62% of the total profits from four Bayrock entities, expected to generate a profit of around $227.5m.

The loan arrangement with FL Group did not make a great financial sense for Bayrock, again according to Kriss and Ejekam, but it was part of Arif and Sater’s scheme to cheat investors as well the US tax authorities. When Kriss complained to Sater that the $50m loan from FL Group was not distributed as agreed, Sater “made him (Kriss) an offer he couldn’t refuse: either take $500,000, keep quiet and leave all the rest of his money behind, or make trouble and be killed.” – Given Sater’s criminal record and threats he had made to another Bayrock partner Kriss left Bayrock.

The short and intense FL saga and its record losses

FL Group was one of the companies that formed the Icelandic boom. Out of many financial follies in pre-crash Iceland the FL Group saga was one of the most headline-creating. In 2002 Jón Ásgeir Jóhannesson, of Baugur fame, bought 20% in the listed air carrier Flugleiðir. In 2004 he teamed up with Hannes Smárason who with a degree from the MIT and four years at McKinsey in Boston had a stellar CV.

Smárason was first on the board until he became a CEO in October 2005. The duo oversaw the take-over of Flugleiðir, sold off assets and turned the company into an investment company, FL Group; inter alia FL Group was for a short while the largest shareholder in EasyJet.

In spring 2007, a group of investors led by Jóhannesson became the largest shareholder in Iceland’s third largest bank, Glitnir. Their Glitnir holding was through FL Group, consequently the bank’s largest shareholder.

At the beginning of 2007, the FL Group debt with the Icelandic banks amounted to almost €600m but had risen to €1.1bn in October 2008. Interestingly, its debt to Glitnir rose by almost 800%. As mentioned above, Jóhannesson and his business partners, among them FL Group, became Glitnir’s largest shareholder in spring 2007, following the pattern that the banks’ largest shareholders were also their largest borrowers.

FL Group – folly or a classic “pump and dump”?

By the end of 2007, 26 months after Hannes Smárason became CEO, FL Group had set an Icelandic record in losses: ISK63bn, now €660m, ten times the previous record, from 2006, incidentally set by a media company controlled by Jóhannesson.

Facing these stunning losses Smárason left FL Group in December 2007. The story goes that at the shareholders’ meeting where his departure was announced he left the room waving, saying “See you in the next war, guys” (In Icelandic: “Sjáumst í næsta stríði, strákar).

There are endless stories of staggering cost and insane spending related to the FL Group boom and bust. Interestingly, a large part of the losses stemmed from consultancy cost for projects that never materialised. Smaller investors lost heavily and in hindsight the question arises if the FL saga was a folly or some version of a “pump and dump.” Smárason was charged with embezzlement in 2013, acquitted in Reykjavík District Court but the State Prosecutor’s appeal was thrown out of the Supreme Court due to the Prosecutor’s mistakes.

FL Group never recovered from the losses and was delisted in the spring of 2008 and its name changed to Stoðir. FL Group never went into bankruptcy but its debt was written off. A group of earlier FL Group managers (Smárason is not one of them) now owns over 50% of Stoðir.

FL Group and the Icelandic Bayrock