Search Results

OSP: a step closer to the secrets of Luxembourg

For three days in February this year the Office of the Special Prosecutor, together with a team of 40 Luxembourg police men, searched the premises of Kaupthing, now Banque Havilland, and other places in Luxembourg in relation to the OSP investigation into Kaupthing. This was one of the biggest actions of this type ever conducted in the Archduchy of Luxembourg. A judge has been ploughing through the documents, believed to be quite a bundle, to certify that the documents retained matched the criteria given by the OSP.

Although the owners of Havilland later claimed that the searches had been unnecessary, the bank would of course have supplied the OSP with all the information it needed, Havilland and 19 others have protested against the handing-over of the documents. A county court in Luxembourg ruled two weeks ago that OSP should have the documents. But that wasn’t the end of story since Havilland e.a. have appealed to the Luxembourg Supreme Court, which is expected to rule on the issue in February.

The OSP investigation will unquestionably move quite a bit forward when and if the boxes from Luxembourg land on their desk. Anyone who has glanced at the Kaupthing loan overview from end of September 2008, leaked via the now so famous Wikileaks, will know that a lot of the seemingly dodgy loans stem from Luxembourg (whereas almost all the loans that look normal come from the Danish FIH). The SIC report confirmed much the same. And it wasn’t only Kaupthing that allegedly made good use of Luxembourg for its apparently shady deals: so did Landsbanki and its former major shareholder Thor Bjorgolfsson still has a wide net of companies there. Glitnir’s operation in Luxembourg wasn’t nearly as big as those of the other two.

Waiting until February is somewhat too long to hold one’s breath but the outcome will be waited with great anticipation. The ruling of the lower court gives hope but Luxembourg is famously a country that guards its secrets well; it’s almost palpable. No doubt, those who want its secrets to stay secret will be pushing hard to convince the authorities that this could jeopardise Luxembourg’s interests in the financial sector since it could set a precedence for others. The Rowlands pere et fils, Havilland’s owners, would like to believe that they are very well connected in Luxembourg. But Luxembourg might also discover that aiding transparency is where the wind is blowing for now.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Rowland and Straumur

Everyone who follows Icelandic affairs will be interested in the activities of the Rowlands, David and Jonathan, who took over Kaupthing Luxembourg, turned it into Banque Havilland and who are now Kaupthing’s administrators through the ‘bad debt’ structure Pillar Securitisation.

A further insight into earlier contacts with Iceland, in this case Straumur Investment bank, have transpired through a court case in London. As Rowena Mason has reported in the Telegraph, Jonathan Rowland is now being sued by Straumur. Three years ago, shares in a company called Xg Technology were transferred to Rowland but the £2m payment never arrived. According to the Rowland camp it turned out that sale of these shares was restricted, Rowland hadn’t been informed and they were consequently worth a lot less than the sum demanded. Straumur now claims that the money is owed by Rowland, no matter what.

There is a whole story out there about Xg – they claimed they had developed a sensational radio technology that has never been realised and their value has plummeted from earlier heights. There is a blog with Xg stories – it makes a riveting read and goes some years back. One of Xg’s directors is an Icelander called Palmi Sigmarsson who was connected to a Swedish company, Spectra, also operating in Iceland but without any apparent success.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

More on Rowland and Kaupthing

The Daily Mail, a UK newspaper, has taken quite an interest in David Rowland, the media-shy millionaire that lived in Guernsey until recently when he felt a pressing urge to donate £2,7m to the Conservative Party. Earlier this year, the party nominated Rowland its new treasurer, due to take office now in autumn. Daily Mail has been untiring in digging up interesting stories about Rowland in order to show the Conservatives predilection for shady money men. As the new owner of Kaupthing Luxembourg, now Banque Havilland, Rowland is of a particular interest to those interested in the aftermath of the collapse of the Icelandic banks.

August 7 Daily Mail came up with a very Daily-Mailish photo of the married Rowland sitting with a middle-aged blond in his lap. Not his wife but, according to the paper, an Italian property agent working in Antigua who, in spite of the intimacy of the scene, wasn’t at all taken in by Rowland. She said he presented himself as a single man but she likes men with ‘more soul’ – and apparently Rowland doesn’t meet that standard. All this according to Daily Mail.

The photo was allegedly taken in Antigua in autumn 2008, a few weeks after Kaupthing collapsed. Rowland was then on this Carribean island pursuing his interest in a property development, i.a. in Hodges Bay, a $60m waterside development where Kaupthing had been the main financial backer.

The collapse of Kaupthing was yet another setback for the Antiguan government – after all, Allan Stanford who is now charged in the US with a $8bn fraud ran his bank and the fraudulent schemes in Antigua. But the Hodges Bay Club still exists and is, according to the club’s website ‘now the reality of a very exclusive dream.’

Who Kaupthing was backing isn’t at all clear since the club’s website doesn’t contain any information on who now owns the club. Kaupthing funded various luxury developments, most noticeably with the Candy brothers. It would indeed be of interest to know who the Kaupthing clients were in the case – the development seems to have been run from London.

But back to David Rowland: it’s mighty interesting that Rowland was scrutinising the Kaupthing backed development because it shows some Rowland ties to Kaupthing. According to the lady on his lap in the end Rowland didn’t invest in the club.

The official Rowland story is that Blackfish Capital, the Rowland investment fund, first became involved with Kaupthing in early spring 2009 as the negotiations with the Libyan Investment Authority on buying Kaupthing Luxembourg collapsed. The Libyan deal collapsed because the bank’s creditors didn’t accept it. Blackfish Capital became involved because the Rowlands, David and his son Jonathan now CEO of Banque Havilland, had been in touch with Kaupthing Luxembourg manager Magnus Gudmundsson earlier that year when the Rowlands were buying some bonds from the collapsed bank.

The rumour in Luxembourg is that Kaupthing’s major shareholder and/or managers were in touch with the Rowlands and still have an interest in the bank. The fact that the Rowlands kept the Icelandic management seemed to support these rumours. It wasn’t until Magnus Gudmundsson was put into custody in Iceland in May that the Rowlands sacked him. The Rowlands firmly deny any contact with Icelanders, earlier connected to Kaupthing.

The fact that Rowland went to Antigua to look into the Kaupthing-related investment is interesting because it shows an earlier Kaupthing connection.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

A PS to the Johannesson Freezing Order

Part of Glitnir’s arguments for the international freezing order against Jon Asgeir Johannesson relates to a €13,6m loan to 101 Chalet, a company owned by Johannesson and Palmadottir, his wife and ‘alter ego’, to use the phraseology from the Glitnir charges brought in New York against the couple together with five others. An interesting addition to this story is that according to the Glitnir QC Richard Gillis Johannesson claims that his sister, Kristin Johannesdottir who’s been a director in many companies related to her brother, signed a guarantee for the loan, without his knowledge.

The report of the Investigative Commission points out that ‘innumerable companies’ are related to Gaumur, the holding company of the Johannesson’s family, with extensive ties to offshore secrecy jurisdictions. 101 Chalet is one of them, owned by Johannesson and his wife. The 101 Chalet loan was a key argument in Glitnir’s motivation for the freezing order since it’s both shows how intertwined the couple’s assets are and how assets were moved between companies and eventually beyond the reach of creditors.

Instead of insisting that the Johannesson companies sold assets and paid up debt during the difficult times of August 2008 Glitnir issued a 13,6m loan to 101 Chalet to buy a chalet in Courchevel. At the time, the owners of 101 Chalet claimed that a loan from a foreign bank was coming their way. Glitnir’s management only accepted though to issue a bridge loan for three months and sought to secure its interests with a letter from the chalet-buyers that the chalet would be sold if the other loan hadn’t materialised in three months and the Glitnir loan repaid. In addition, Glitnir had collaterals in 101 Chalet and in Piano Holding, a Panama company holding the 101 Heesen yacht (sold by the Kaupthing Luxembourg administrators, Banque Havilland, last year). When the loan wasn’t repaid it transpired that the Piano Holding guarantee was worthless from inception because the 101 yacht had been encumbered.

In addition, Glitnir sought a guarantee from Gaumur, signed by Johannesson, his sister and his father.

Three months later, Glitnir had collapsed and no other loan had been secured for the chalet. However, the chalet wasn’t sold until more than a year later. During the freezing order case Johannesson admitted that the 101 Chalet loan contract had been breached.

As with so many of the loans to the Icelandic banks’ chosen customers the loan to 101 Chalet was passed on to another Baugur company, BG Danmark. Last year, when the chalet was finally sold the proceeds from the sale didn’t go to Glitnir but to Palmadottir. Johannesson has now paid ISK2bn to Glitnir but Glitnir notes that the money is partly coming from Palmadottir, not out of Johannesson’s assets. Another chalet, previously owned by BG Danmark is amongst the assets of the now bankrupt Baugur in Iceland and 101 Chalet’s value is 0 on the list of Johannesson’s assets.

An interesting twist in this tale is that in QC Gillis’ skeleton statement it says: ‘Mr Johannesson sought to argue that the personal guarantee* in his name had been signed by his sister without his authority.’ – I leave it to the readers to interpret what this implies.

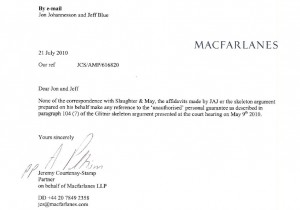

Johannesson’s sister firmly denies having signed the Gaumur guarantee without her brother’s authority. Johannesson hasn’t been interviewed on this issue. He has however issued a statement** saying that he has never accused his sister of having signed anything without his knowledge. Attached to his statement is a letter from his lawyer Jeremy Courtenay-Stamp.

Plenty of conflicting stories here – so there must be more to come…

*The Gaumur guarantee.

** In Icelandic but there are quotes there in English. The letter above is from Johannesson’s statement.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

The complicated life of David Rowland

David Rowland, who will be the Conservative Party’s treasurer come October, has had a colourful live with some dirty spots here and there – or that’s at least what the Daily Mail has dug up. Rowland bought Kaupthing Luxembourg, turned it into Banque Havilland with his son Jonathan now as its CEO after Magnus Gudmundsson who used to run Kaupthing Luxembourg and was retained by the Rowlands was remanded in custody because of an ongoing Icelandic investigation of Kaupthing. Havilland is the administrator of the failed bank, through Pillar Securitisation.

It was through Kaupthing Luxembourg that Kaupthing, under Gudmundson, ran its most shady deals – and from there the web trails to offshore havens such as Panama, Cyprus and most notably the BVI. Recently, authorities in Luxembourg searched the premisses of Havilland on behalf of the Office of the Special Prosecutor in Iceland, to aid investigations unrelated to the present Banque Havilland.

It’s interesting to note, however, that there are still some Icelandic clients at Havilland. Gaumur, a company owned by Jon Asgeir Johannesson and his family, has a Luxembourg subsidiary registered with Havilland with three BVI companies, previously owned by Kaupthing, registered as Gaumur S.A.’s directors so no changes there in that respect.

Daily Mail notes that Rowland once said that money makes your life complicated and the more money the more complicated life becomes. Now that Rowland will be taking up a position with the Tories he’s bound to be heavily scrutinised by the press and that might in turn make his life more complicated.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

A tale of a ‘low standard of commercial morality’

‘There is something unreal about this,’ the sharp and witty Justice David Steel said late in the day Friday afternoon, after listening to Glitnir lawyers debating from the morning with lawyers representing Jon Asgeir Johannesson. In the dignified surroundings of Old Bailey his team was trying to quash the international freezing order that the Glitnir Winding-Up Board obtained at the Royal Court of Justice in May. More than once, Justice Steel reminded himself and the others present – mostly lawyers, apart from the black-clad couple Johannesson and Ingibjorg Palmadottir and a couple of their friends – that Johannesson had been the prince of the UK high street challenging the king of retail, Sir Philip Green.

To begin with, Johannesson’s lawyer asked for the hearing to be held in private – the delicate information unavoidably disclosed would be all over the Icelandic papers tomorrow (as a matter of fact the news was out during the lunch break) – but Justice Steel upheld the core British principle of an open court. So I wasn’t thrown out but could sit and listen – and there was a lot to hear.

Johannesson claims that his assets now total only £1,1m: his assets in the UK total £199.000, including three cars – a Rolls Royce Phantom, a Range Rover and an Aston Martin. However, after presenting the list of assets earlier Johannesson has now changed his mind on the Rolls Royce claiming it’s a gift to his wife though he hasn’t produced any documents to support his claim. In London Johannesson lives in a rented property, paying £6.000 a month. From JMS Partners, the company that Johannesson co-owns with House of Fraser chairman Don McCarthy and ex-CEO of Baugur Gunnar Sigurdsson Johannesson draws a £700.000 annual salary – though its operation is rather unclear.

In Iceland, his assets are again three cars, two Range Rovers and a Bentley and then four houses one of which is heavily mortgaged, £15.000 in four bank accounts and shares of no value in several companies, most noteworthy in Gaumur where Johannesson owns 45%. Gaumur’s debt is ISK8bn and seems, according to Justice Steel, in reality insolvent. Earlier, Johannesson had claimed that he co-owned Hotel 101 with his wife but now claims that his wife owns is. He also claims that two properties are hers although the mortgages are in his name. He has £22.000 in a Coutt’s account and some $70.000 in an account with Citigroup.

Justice Steel was intrigued by the fact that a man who was once said to be worth £600m, who had in the years 2001-2008 a monthly expenditure £280.000-350.000 (!) and also had £11m flowing through his Glitnir account in autumn 2008, as the banks were collapsing, now only has a paltry £1,1m worth of asset to show for it out of which 275.000 are in cars. An expenditure on this level couldn’t but leave something more substantial behind thought the judge.

Around the time that Glitnir obtained the freezing order Johannesson had ca £500.000 flowing in and out of his account at Coutt’s (a UK bank for very wealthy individuals) – Johannesson’s lawyer explained, apparently to Justice Steel surprise, that the money stemmed from the sale of his ex-wife’s house, bought by him, and then used immediately to pay off bills that Johannesson hadn’t been able to pay earlier.

Today it transpired that Johannesson and his wife used to own two (not just one as earlier believed) yachts, one of which had been repossessed and sold on by Kaupthing Luxembourg (in reality, Banque Havilland). The interesting point here is that according to Justice Steel no documents have been produced to prove the sale – and the Kaupthing Luxembourg administrators have not been willing to co-operate with Glitnir on this matter. The question left hanging in the air was if the proceeds of the sale really did go to Kaupthing. The other yacht, a Ferretti, was pledged to and apparently repossessed by Sparbank – a surprising lender if it’s the Danish Sparbank since it’s a small bank.

An additional reason to distrust Johannesson’s list of assets produced was, according to Justice Steel, the fact that Johannesson had been less than forthcoming with information and had then changed his mind on some things without any documents to support what Johannesson then called ‘mistakes.’ Also that he hadn’t been able or willing to produce any overview of his salary at Baugur – only, that a flow of £3-4m had gone through his pockets every year. In all, £30m had been paid to his Glitnir accounts during these years. SWIFT transfers show accounts with Kaupthing Luxembourg, KSF and Royal Bank of Scotland.

Justice Steel had also doubts about the source of Johanneson’s funding, i.a. the loan on the flats in New York where Landsbanki had lent of $25m without any security. It was obvious that his Lordship struggled to understand the logic in this for the bank. And he also struggled to understand the change of ownership in the media company 365 midlar that Johannesson now claims belongs to his wife. Nor could his Lordship understand that someone who didn’t seem to have any assets was engaging lawyers both in the UK and the US. Probing his lawyer on that the lawyer also had difficulties in explaining the importance of a freezing order when there were practically no assets to freeze.

Listening to these and other issues, Justice Steel said he wasn’t assured that Johannesson had given a full and frank disclosure of his assets. In addition, there was the complicated corporate structure that would give ample room to move assets around. The fact that Johannesson had sold the Chalet 101 to his wife while negotiating with Glitnir on how to repay the loan didn’t inspire confidence either. The judge also mentioned what the Glitnir lawyer had said: that Johannesson’s conduct indicated a ‘low standard of commercial morality’ – on the whole there was, according to Justice Steel, a real risk that assets would be disposed of, leading him to renew the freezing order.

In the end, Johannesson’s lawyers had to disclose their bill of whopping £600.000 – Johannesson has to pay all cost, possibly running up to £360.000 but the immediate payment is £150.000. If he doesn’t pay he risks being declared bankrupt.

The freezing order is related to the Glitnir case in the UK against Palmi Haraldsson and Johannesson regarding ISK6bn loan to Haraldsson’s Fons. The basis of that case is that assets were sold at a premium only to extract money from Glitnir for the benefit of the two businessmen and make the bank lose. – No doubt, there is more of amorality and the unreal to come.

*There were no documents handed out in court – I hope the information above is correct but mis-hearing or misunderstanding can’t be ruled out.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Where are they now?

‘Iceland was bankrupted by twenty or thirty men.’ That’s how Vilhjalmur Bjarnason lecturer at the University of Iceland and a vocal commentator on finance and business put it a few months after the collapse of the banks in October 2008. At first, many felt that Bjarnason was overstating his case but time – and most clearly the report of the Althingi Investigative Commission – has shown that it did indeed only take ca thirty people (almost all male) to bankrupt Iceland.

Most Icelanders will be able to list these thirty odd names. These are the bank managers, the banks’ chairmen and the banks’ principal shareholders. The understanding is that the Office of the Special Prosecutor will in due course most likely bring criminal charges against these people. The banks’ resolution and winding-up committees are already bringing charges or planning charges against these people to claw back the money extracted from the banks by illegal means.

All these people were extremely prominent and visible in Iceland in the years up to October 2008. They sponsored art, culture, sport and charities and appeared frequently in the media. Some of them gave interviews in the weeks and months after the collapse but as more light was thrown on the operations of the banks and their shareholders they have become increasingly silent. After the report, little is heard from them – there isn’t much to say now that the report has spelled it out so clearly what went on, including verbatim sources such as emails. Some of this material contains phrases that everyone in Iceland now knows by heart such as ‘Thank you, more than enough:-)’ – the succinct answer from Magnus Gudmundsson director of Kaupthing Luxembourg when Kaupthing’s executive chairman informed him, in equally few words, that his bonus for 2007 would be €1m.

From being feted and admired these people are now generally despised in Iceland. There are stories of theatregoers unwilling to stand up to let them to their seats at the theatre, guests at restaurants driving them out, passengers accosting them as they waited for their luggage at Keflavik airport. There are even stories that they have been hit or spat on, on the streets. People threw snowballs at Jon Asgeir Johannesson when he left his wife’s hotel in Reykjavik during the winter following the collapse of the banks.

No wonder that many of them prefer to live abroad. There have been rumours lately that some of them might want to move to Luxembourg but sources close to a well known Luxembourg bank claim that some of the more famous names have already been turned down as clients. And in order to properly settle down in Luxembourg one has to register with the police. People then do have to declare if they have an earlier conviction or if they are under investigation – not a trivial question for some of the Icelanders who might be considering to move to Luxembourg.

For most of these people the yachts and private jets are gone. Some are bankrupt other still hold on to some assets though more might be lost later on. In Iceland, many speculate if and then how much these people have stacked away on in offshore save havens. But where are they now, the bankers and the Viking raiders?

Kaupthing

When Sigurdur Einarsson ex-executive chairman of Kaupthing was summoned to Iceland in May to be interviewed by the OSP in Iceland he refused to go to Iceland since he didn’t want to risk following three Kaupthing ex-top executives into custody. He probably didn’t expect that he would end up on Interpol’s wanted list – but that’s where he’s now. Einarsson isn’t known to have been involved in any business after the collapse of the bank and has been living in London since 2005. According to the AIC report Kaupthing lent Einarsson the £10m needed to buy his house in Chelsea – and then Einarsson rented his house to the bank so he could live in the house, apparently an exceedingly smart way of living for free as the rent paid or didn’t pay off the mortgage.

Kaupthing’s CEO Hreidar Mar Sigurdsson moved to Luxembourg last year to run Consolium, a consultancy staffed by several ex-Kaupthing managers. Sigurdsson was held in custody for ten days in May as the OSP picked through his testimony and some of his colleagues’. Sigurdsson is now back in Luxembourg.

Magnus Gudmundsson was the director of Kaupthing Luxembourg where some think that Kaupthing’s darkest secrets, if there are any, were kept. When David and Jonathan Rowland, father and son, took over Kaupthing Luxembourg last year and turned the good bank into Banque Havilland and put the bad assets into Pillar Securitisation that Havilland administrates, they retained Gudmundsson as a director, much to the surprise of those who thought that the new owners wanted to start with a clean slate and a new business. When however the OSP put Gudmundsson into custody the Rowlands dropped him like a hot potato. Consolium had business ties with Havilland and Pillar and according to my sources these ties are still in place.

Olafur Olafsson has a longer business record than most of the other high-flying Icelandic bankers and businessmen since he’s older than most of them. He grew up when political ties were essential and his fortune was tied to the Progressive Party and the co-op movement, part of the Progressive sphere of influence. From Kaupthing’s first ventures during the late 90s he was close to them, underlining that bank’s connection to this party.

The softly spoken cultivated Olafsson wasn’t much seen in Iceland during the noughties but he had and still has a charity there. He used to have an office in Knightsbridge and lived close by. Last year he moved to Lausanne. According to a Swiss source he lives modestly. The SIC report is full of juicy stories of Olafsson – there’s his connection to the Qatari investor al Thani who seemed to have the greatest trust and belief in Olafsson’s two main undertakings in Iceland, Alfesca and Kaupthing. But according to the report there was less trust and more loans from Kaupthing. Through Kjalar Olafsson owned 10% in Kauphting but still holds on to companies in Iceland, most notably the shipping company Samskip. The Kaupthing loan overview from end of September 2008 indicates that Olafsson’s personal loans from Kaupthing Luxembourg were €49m.

Until shortly before the collapse of Kaupthing brothers Lydur and Agust Gudmundsson, the bank’s biggest shareholders, were seen as being of a different breed from Viking raiders such as Jon Asgeir Johannesson and Thor Bjorgulfsson. The brothers started in fish manufacturing during the 90s, seemed to have built their wealth up out of concrete things and not only financial acrobatics. But the report throws a different light on their activities, their close if not incestuous connections with Kaupthing and equally close ties to many of the bulging Icelandic pension funds. Robert Tchenguiz sat on the board of Exista.

Lydur owns a beautiful house in Reykjvik where he hasn’t been much seen lately and a grand house on Cadogan Place that Pillar now wants to take over due to unpaid mortage of £12,8m. It seems that Agust might suffer the same fate – Pillar isn’t showing any mercy and according to the loan overview Agust had a mortage of €9m with Kaupthing Luxembourg. As Olafsson the brothers still hold on to companies in Iceland, most notably the investment company Exista and the food company Bakkvor UK – but the final outcome is still unclear.

Landsbanki

Father and son, Bjorgolfur Gudmundsson and Thor Bjorgolfsson, shot to fame in Iceland when they managed to set up a brewery in St Petersburg in the 90s. The story of that venture is most fully told in a front-page article in Euromoney November 2002, ‘Is this man fit to be at the helm (of Landsbanki)?’ and in documents on Wikileaks: the short version is that father and son were working for two investors running a bottling plant in St Petersburg in the early 90s. One day in 1995 the investors found out they no longer owned the bottling plant though they couldn’t remember ever having sold the plant father and son and their co-worker Magnus Thorsteinsson. The venture took off and the St Petersburg power elite, i.a. Vladimir Putin, was friendly. Deutsche Bank started financing other Bjorgolfsson’s ventures in Easter Europe in the late 90s. When the trio sold the brewery to Heineken in 2002 they had the money to buy 40% of Landsbanki, then already partly privatised.

The distinguished-looking Gudmundsson is now bankrupt, having not only lost his share of Landsbanki but also his ultimate trophy asset West Ham and lives in Iceland. His son, with the body of a body builder and the square jaws to go with it, still lives in Holland Park though there might be fewer vintage cars in the garage now. It’s not clear if he still owns his country house in Oxfordshire but he is holding on to Novator, his investment company with ties to Luxembourg, the Cayman, Cyprus and other offshore havens. The fate of his biggest asset, Actavis, depends on what Deutsche Bank intends to do about the loan against Actavis, said to the single biggest loan on DB’s loanbook. The question is if DB turns the debt into equity, practically taking Actavis over, or if Bjorgolfsson manages to turn things to his benefit. Thorsteinsson was declared bankrupt in Iceland last year, used to have a large country estate in the UK but is now said to live where it all started, St Petersburg.

Landsbanki had two CEOs, Sigurjon Arnason and Halldor Kristjansson. Kristjansson was a civil servant before becoming the CEO of Landsbanki as it was being privatised. Arnason was the CEO of Bunadarbanki but when Kaupthing bought the bank he and a whole team from Bunadarbanki defected over to Landsbanki. Kristjansson kept the quiet demeanour of a civil servant, Arnason was the aggressive banker known to empty bowls of chocolate is within his reach. It’s interesting to note that Kristjansson kept his post after the privatisation, possibly underlining that the change wasn’t as fundamental as one might have thought – the political ties were still important. Kristjansson now lives in Canada, working for a financial company. Arnason lives in Iceland and is, as far as is known, not involved in any business.

Glitnir

While Landsbanki and Kaupthing were involved with high-flyers abroad Islandsbanki, later Glitnir, seemed more down-to-earth expanding in Norway. Bjarni Armannsson ran the bank with experience from the investment bank FBA in the late 90s. The AIC report shows that Armannsson was very deft at trading for his own companies along running the bank leading the report to advice clearer regulation of CEO’s personal dealings. Armannsson left the bank when Jon Asgeir Johannesson and the FL Group gang became the bank’s largest shareholder in early 2007. He moved to Norway for a while but has recently returned to Iceland and runs his own business there.

Earlier on, two brothers were among Glitnir’s major shareholder, Karl and Steingrimur Wernersson. Their father was a wealthy pharmacist and they, mainly Karl, built on that wealth which mushroomed into companies at home and abroad under their investment fund Milestone. Milestone bought into the Swedish financial sector, bought a bank in Macedonia and an Icelandic insurance company, Sjova, in Iceland. The crudeness and excesses of it all, i.a. a villa in Italy and a vinyard in Macedonia, have been masterly documented by the daily DV in Iceland. Milestone is bankrupt and the brothers are no longer on speaking terms as Steingrimur, who now lives in North London, has accused his brother of bullying him into business ventures. Karl lives in Iceland and spends most of his time on his farm in Southern Iceland where he tames and breeds horses.

The group that came to power and ownership in Glitnir was headed by Jon Asgeir Johannesson, famous his UK retail partners such as Sir Philip Green, Tom Hunter, Kevin Stanford and Don McCarthy. Johannesson started his business ventures by opening a supermarket with his father Johannes Jonsson who now lives in Akureyri. Jonsson is still involved in business though there a now more debts than assets to care for.

Johannesson has for years invested together with a small group of Icelandic businessmen, most notably Palmi Haraldsson, Magnus Armann and his wife Ingibjorg Palmadottir, herself the daughter of the man who built up the biggest retail empire until Johannesson arrived on the scene, bought the empire and later got the princess as well. These shareholders brought in a new CEO, Larus Welding who ran the bank for just over a year. Welding now lives in Northern London and doesn’t seem to be involved in banking anymore. Johannesson still owns the biggest private media company in Iceland. His ownership is the source of some speculation in Iceland since Baugur, also Baugur UK, and so many other investments of his have failed.

On the sideline in this group but for a while extremely powerful was Hannes Smarason, much admired as the McKinsey man who turned biotech to gold at deCode and later built up the investment fund FL Group that outshone everyone in excesses and, in the end, losses. Smarason lives in Notthing Hill, London and documents at Companies House show a string of failed business ventures of his.

The connection between Johannesson, Armann and Haraldsson goes roughly a decade back and though his Icelandic partners were less famous than some of his UK partners they stayed with him. Now they all and Palmadottir are charged by the Glitnir Winding Up Committee that wants $2bn dollars back. Haraldsson has two major investment companies, one is bankrupt the other is in operation and he still owns Iceland Express. Haraldsson has been living in Iceland but has a flat in Chelsea, London.

Johannesson allegedly lives with his wife in Surrey on the same road as Armann, yet again underlining not only the closeness of these two but also the Icelandic tendency to stay with one’s own countrymen. A clan mentality that also characterised the now failed Icelandic banks and businesses.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Icelandic Tory ties: Rowland, Spencer and Yerolemou

David Rowland, the owner of Blackfish Capital UK, has been named the treasurer of the Conservative party. Through their ownership of Banque Havilland Luxembourg David and his son Jonathan are almost household names in Iceland. But there are other intriguing Tory connections to the Icelandic banks, notably Kaupthing.

David and Jonathan Rowland, or rather their investment company Blackfish Capital, took over the Kaupthing operation in Luxembourg last year and turned it into Banque Havilland. Havilland draws its name from the family’s Guernsey address, the splendid Havilland Hall. Father and son firmly deny any connections to the owners of Kaupthing but they held onto Magnus Gudmundsson until he was taken into custody due to the Kaupthing investigation in Iceland. The Rowlands have stressed that house searches at the former Kaupthing premises in Luxembourg earlier this year were unrelated to Banque Havilland. It is of interest that Martyn Konig, a well merited banker who had worked for Blackfish, resigned as a chairman of Havilland almost as soon as it opened.

Earlier, the Rowlands weren’t bothered neither over the Kaupthing investigation in Iceland nor in the UK – and yet, it’s been clear for a long time that the Kaupthing Luxembourg operation was central in all the deals and connection that are being investigated, be it the al Thani case or loans to UK business men such as Kevin Stanford and Robert Tchenguiz. It’s interesting to notice that al Thani is of the Qatari ruling family. Recently, a court case in London showed that a Qatari company bowed to pressure from Prince Charles. Christian Candy who won that case was also one of Kaupthing’s clients and a partner in joint ventures with the bank.

A source close to the Havilland informed me earlier this year that the Rowlands were interested in private banking and had been looking for a bank to buy for some time. When the Libyian Investment Authority’s offer for restructuring Kaupthing was turned down by the bank’s creditors and JC Flower’s rumoured interest didn’t materialise the Rowlands stepped in to buy the bank. The good assets were put into Havilland and Pillar Securitisation took over the bad assets, administrated by Havilland.

Unexpectedly, the Rowlands and Blackfish are also a well-known name in Latvia. When the renowned newspaper Diena was sold last year it seemed at first that Latvian businessmen with previous ties to the paper were buying it. Then it turned out they didn’t really have that kind of money and in the end the real owners came forth: Blackfish and the Rowlands. Why they suddenly wanted to own a newspaper in Latvia seemed hard to explain – and hasn’t really been explained except the Rowlands say they won’t interfere with the editorial line. That didn’t satisfy the Diena journalist: most of them left the paper and have now founded a new paper.

David Rowland moved from Guernsey to England in 2009 to be able to donate money to the conservatives. He has donated £3m, is now the party’s major donor – and that qualifies him to be the next party treasurer when Michael Spencer steps down in autumn. Now that the Conservatives are in government Spencer isn’t quite the kind of name they want to be linked to. Spencer has long had a reputation for being rather unsquemish when it comes to ways to make money. Last December, Spencer’s company Icap made $25m settlement with the US Securities & Exchange Commission, following a four years investigation, to escape charges for using fake trades to encourage customers to trade.

But Spencer’s company Icap was also a broker in the UK and did business with the Icelandic banks. Butlers, Icap’s financial consultancy, advised its customers, i.a. many of the UK councils, to keep their funds with the Icelandic banks even though the rating agencies, unbelievably late, downgraded the banks. Consequently, the councils that used the advice of Butlers lost badly and lost more than those who had other or no advisors. A possible conflict of interest has been alleged but strongly denied by Icap and Spencer. But the owner of a company that used fake trades would certainly have found a common ground with the Icelandic banks that are now being investigated i.a. for market manipulation.

Interestingly, the incoming and the present treasurer of the Conservative party aren’t the only conservative high-fliers with Icelandic connections. Tony Yerolemou is one of the Tories important donors and has been over the years. The Cypriot food producer was one of the owners of Katsouris Food, sold to Bakkavor in 2001. He got very close with the Bakkavor owners Lydur and Agust Gudmundsson who eventually became Kaupthing’s biggest shareholders. – And mentioning the Rowlands: as administrator Pillar is claiming back a Kaupthing Luxembourg loan to Lydur who might lose his £12.8m house on Cadogan Place if he can’t refinance his loan.

The Rowlands might also have to pick over their fellow conservative Yerolemou who not only sat on the Kaupthing board but had huge loans with the bank through Luxembourg. When the bank collapsed Yerolemou was one of the bank’s biggest debtors, his loans through Luxembourg amounting to €365 (whereof £203m were unused). The report of the Althingi Investigative Commission concludes that because of the loans and because his companies were firmly in red Yerolemou hadn’t been fit and proper to be on the bank’s board. Together with Skuli Thorvaldsson Yerolemou was involved in companies organised by Kaupthing and partly financed by Deutsche Bank to influence Kaupthing’s CDS spread. Yerolemou has been the chairman for Conservatives for Cyprus – and interestingly, the Conservative party had pledged before the election to give Cyprus priority when the party would be in power. Yerolemou has donated money to the campaigns of various MPs, i.a. Theresa Villiers now minister of State for transport and who also very much has the interest of Cyprus at heart.

Apart from ongoing investigations in Iceland the Serious Fraud Office is conducting an investigation into Kaupthing. With the conservatives in power and the particular ties that some conservatives have had with Kaupthing it will be of great interest to see what happens with the SFO investigation. It’s also interesting to see if authorities in Luxembourg make a move to look more closely at the Kaupthing operation in Luxembourg.

Who would have guessed there were so many Icelandic ties to the Conservative party? There are many stories to follow here.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

The Kaupthing-four free to travel again – widening investigation

The four ex-managers of Kaupthing, recently held in custody in Iceland where the office of the Special Prosecutor is investigating Kaupthing, are now free to travel. After Hreidar Mar Sigurdsson, Magnus Gudmundsson, Ingolfur Helgason and Steingrimur Karason were released from custody they weren’t allowed to leave the country. That ban has now been repealed. The four of them have all been living in Luxembourg.

Sigurdsson was the bank’s CEO, Gudmundsson was the manager of Kaupthing Luxembourg, Helgason was the CEO of Kaupthing Iceland and Karason was the head of risk. Gudmundsson was kept as a manager after the Rowland family, owner of Blackfish Capital, took over Kaupthing Luxembourg but after he was remanded in custody Magnusson was dismissed from his job at Banque Havilland. After the collapse of Kaupthing the three other ex-Kaupthing managers set up a company in Luxembourg, Consolium and had i.a. business relations with Gudmundsson.

As I’ve mentioned in earlier Icelogs there are plenty of rumours around the Blackfish acquisition of Kaupthing Luxembourg. The Rowlands have from the first firmly denied any Icelandic connections or that there are any Icelandic owners among them. They claim that since they had already in mind to set up a bank buying a bank, although in a moratorium, was a simpler process than building up one from scratch.

That’s no doubt true in the sense that Kaupthing already had a client basis – but according to sources that I spoke to in Luxembourg when I was there last week it’s no easier, rather the opposite, when taking over an existing bank. Since Kaupthing was in moratorium the new owners will have been thoroughly scrutinised by the CSSF, the Luxembourg financial services authority. Buying will not have been a short-cut to get a banking license in Luxembourg.

The rumours haven’t died down and probably won’t until further light is thrown on Kaupthing’s operation by the OSP and the SFO, also investigating Kaupthing. After the OSP had meetings last week with authorities in Luxembourg, Belgium and representatives from the SFO and Europol it now seems likely that Luxembourg will become a party in these ongoing investigations and that the investigations will possibly be linked through Europol. Clearly, the possibly fraud that Kaupthing is being investigated for has ramifications far beyond Iceland.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Ripples from charges and investigations

Following the charges brought by Glitnir’s wind-up committee at a court in New York and an international freezing order on his assets from a court in London Jon Asgeir Johannesson has resigned from the boards of the two companies where he has represented the Landsbanki resolution committee, the supermarket chain Iceland and House of Fraser. Following Johannesson’s conviction in Iceland in the so-called Baugur case in 2008 he was forced to resign from all boards in his Icelandic companies since a conviction bars anyone from being on a board but the Icelandic conviction didn’t seem to affect his foreign activities. The Glitnir charges recently brought against Johannesson in Iceland didn’t seem to have any effect in this direction but it’s unclear if his decision now was a voluntary one or if he was under pressure to resign.

Following the freezing order Johannesson was obliged by the WuC to hand over a complete list of his assets within 48 hours. However, the WuC has declared that it won’t inform publicly whether Johannesson has met this obligation or not. First when Johannesson was presented with the charges in New York Johannesson indicated that he wouldn’t try to defend himself, the cost would be exorbitant. He has now changed his mind and will use all available legal powers to fight Glitnir’s WuP.

Magnus Gudmundsson, ex-manager of Kaupthing and, until recently, of Banque Havilland, was released from custody on Friday as was expected. Afterward, he issued a statement underlining his innocence, the harrowing effect that the case was having not only on him but his family and that he was co-operating fully with the Office of the Special Prosecutor. He pointed out that he had traveled to Iceland on his own accord for the questioning at the OPS.

The last statement could be seen as a message to ex-executive chairman of Kaupthing Sigurdur Einarsson who has been unwilling to travel to Iceland since he couldn’t get an assurance that he wouldn’t be taken into custody. There are rumours that the families and close friends of those who have been put into custody are very upset with Einarsson since his unwillingness to show up for questioning can very well have made life more difficult for the three who were placed in custody. Hreidar Mar Sigurdsson and Ingolfur Helgason were released from custody today. Sigurdsson isn’t allowed to leave the country until next week.

Asked yesterday on Silfur Egils, a political chat show on Icelandic tv, the French-Norwegian ex-magistrator and now French MEP Eva Joly, advising the OSP, said that Einarsson wouldn’t have anything to fear if he was innocent. The fact that Einarsson has chosen not to show up and is now on Interpol’s wanted list doesn’t change the course of the investigation, according to Joly. She was stoic about complaints that custodial sentences and Interpol arrest warrants were too severe but pointed out that many felt an acute discomfort over the treatment of alleged white-collar criminals. Only few identify with drug sellers and thieves but the whole establishment could usually identify with people who are charges with white-collar crimes. (You can watch the interview here; it’s in English but the programme begins in Icelandic.)

But there are more bad news for ex-Kaupthing high fliers. The bank lent in all ISK32bn (now £16m) to 80 key-employees to buy shares of the bank. Twenty of these 80 got ca 90% of these loans – and 50 of these 80 people are still working at Arion, the New Kaupthing. Hreidar Mar Sigurdsson borrowed ISK5,8bn and Sigurdur Einarsson borrowed ISK7,8bn. At the time, these loans were presented as a salary boost to these employes. In hindsight, this looks more like part of the extensive share ‘parking’, alleged to be part of market manipulation. The only collaterals for these loans were the shares themselves but the borrowers gave personal guarantees as well. A few of the employees had been allowed to place the shares in limited liabilities companies.

Shortly before Kaupthing collapsed the board of the bank decided to release these employees from their personal guarantee, thereby underlining that the employees weren’t meant to make any loss on these loans but only to pocket the dividend. The extent of these loans didn’t become public until well after the collapse. The loans have been a bone of contention for a long time, also with the tax authorities, symbolising so much of what was wrong with banking the Icelandic way.

The Kaupthing wind-up Committee has now decided that the employees shouldn’t be released from their personal guarantee. They now have ten days to either repay the loans or renegotiate the terms. The WuC has also declared that it will try to circumvent the right to put the shares into limited liabilities companies meaning that those with companies will also be hit. This will no doubt put many of the employees under severe financial strain since the loans were in many cases far beyond what the salaries of these people justified.

In the Althingi Investigative Commission’s Report it’s clear, from statements from ex-Kaupthing employees that they saw themselves as held hostages by the bank since they were not meant to sell their shares. This underlines the sense of share ‘parking’ by the bank. In the end, the loans that were supposed to enrich these chosen employees might well end up bankrupting them, showing the bank’s cynicism in serving its own interests rather than the interests of its employees.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.