Search Results

Guess who came to a Downing Street dinner? David Rowland

The UK Conservative Party battles against the sleaze that’s oozing out in the wake of the under-cover Sunday Times interview with Tory treasurer Peter Cruddas, now understandably the ex-treasurer. In the interview, Cruddas sets the rates for access to Tory leading lights, mentioning that £250.000 will get you a dinner with Prime Minister David Cameron. A case now called “Cash for Cameron” by the UK media.

Cameron completely denies all this, finds Cruddas’ entrepreneurship on behalf of the party “completely unacceptable.” Having admitted to invited some main donors to dinner, Cameron was forced to publish a list of those favoured with such favours. On the list is the man who was going to be treasurer himself, until he found out he didn’t have the time. That decision might have had something to do with a series of very unflattering articles that the Daily Mail published on him.

But however unflattering Daily Mail’s reporting did no lasting harm to Rowland’s reputation in Downing Street. On Feb. 28 last year, David Rowland and his wife were invited to dinner, together with Baron Andrew Feldman, ennobled by his friend Cameron for whom he has been a diligent fundraiser and now a co-chairman of the Conservative Party. They will most likely have sat in this nicely conservative state room above nr 11 Downing Street and sipped whatever those with conservative leanings sip.

Cruddas pointed out that by paying the £250.000 one would be in the “premier league” and would be listened to. Rowland is way beyond that since his contribution to the party is counted in millions of pounds. So what might he have discussed with Cameron? Apart from the usual, such as too much taxation, Rowland might have talked about the fantastic opportunities he finds in having a bank in Luxembourg and Monaco, a newspaper in Latvia and shares in the Icelandic MP Bank, not to mention Belarus.

Since Belarus has been in the news lately for political repression and horrors, Cameron could have been interested in Rowland’s Belarus venture, the first FDI fund there. At the time, Havilland’s press release was probably still on the Havilland website but it’s now been removed. We don’t know how Cameron’s staff prepared these dinners but most likely Cameron was more listening than questioning. After all, Rowland and other guests did quite a bit to bring Cameron to Downing Street and critical questions might have been as unacceptable as Cameron thought Cruddas’ fundraising initiative.

*Rowland also has ties to Prince Andrew. Here are links to other Icelog entries on Rowland.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

The al Thani story behind the Kaupthing indictment (updated)

The Office of the Special Prosecutor is indicting Kaupthing’s CEO Hreidar Mar Sigurdsson and Kaupthing’s chairman Sigurdur Einarsson for a breach of fiduciary duty and market manipulation in giving loans to companies related to the so-called ‘al Thani’ case; indicting Kaupthing Luxembourg manager Magnus Gudmundsson for his participation in these loans and Kaupthing’s second largest shareholder Olafur Olafsson for his participation. In addition, Olafsson faces charges of money laundering because he accepted loans to his companies without adequate guarantees.

In September 2008 Kaupthing made much fanfare of the fact that Sheikh Mohammed bin Khalifa al Thani, a Qatari investor related to the Qatar ruler al Thani, bought 5.1% of Kaupthing’s shares. The 5.1% stake in the bank made al Thani Kaupthing’s third largest shareholder, after Olafsson who owned 9.88%. This number, 5.1%, was crucial, meaning that the investment had to be flagged – and would certainly be noticed. Einarsson, Sigurdsson and Olafsson all appeared in the Icelandic media, underlining that the Qatari investment showed the bank’s strong position and promising outlook.

What these three didn’t tell was that Kaupthing lent the al Thani the money to buy the stake in Kaupthing – a well known pattern, not only in Kaupthing but in the other Icelandic banks as well. A few months later, stories appeared in the Icelandic media indicating that al Thani wasn’t risking his own money. More was told in SIC report – and now the OSP writ tells quite a story. A story the four indicted and their defenders will certainly try to quash.

The story told in the OSP writ is that on Sept. 19 Sigurdsson organised that a loan of $50m was paid into a Kaupthing account belonging to Brooks Trading, a BVI company owned by another BVI company, Mink Trading where al Thani was the beneficial owner. Sigurdsson bypassed the bank’s credit committee and was, according to the bank’s own rules, not allowed to authorise on his own a loan of this size. The loan to Brooks was without guarantees and collaterals. This loan, first due on Sept. 29 but referred to Oct. 14 and then to Nov. 11 2008, has never been repaid. – Gudmundsson’s role was to negotiate and organise the payment to Brooks. According to the charges he should have been aware that Sigurdsson was going beyond his authority by instigating the loan.

But this was only the beginning. The next step, on Sept. 29, was to organise two loans, each to the amount of ISK12.8bn, in total ISK25.6bn (now €157m) to two BVI companies, both with accounts in Kaupthing: Serval Trading, belonging to al Thani and Gerland Assets, belonging to Olafsson. These two loans were then channelled into the account of a Cyprus company, Choice Stay. Its beneficial owners are Olafsson, al Thani and another al Thani, Sheikh Sultan al Thani, said to be an investment advisor to al Thani the Kaupthing investor. From Choice Stay the money went into another Kaupthing account, held by Q Iceland Finance, owned by Q Iceland Holding where al Thani was the beneficial owner. It was Q Iceland Finance that then bought the Kaupthing shares. As with the Brooks loan, none have been repaid.

These loans were without appropriate guarantees and collaterals – except for Serval, which had al Thani’s personal guarantee. After noon Wed. Oct. 8, when Kaupthing had collapsed, the US dollar loan to Brooks was sent express to Iceland where it was converted into kronur at the rate of ISK256 to the dollar (twice the going rate in Iceland that day) and used to repay Serval’s loan to Kaupthing – in order to free the Sheik from his personal guarantee.

This is the scheme, as I understand it from the OSP writ. And all this was happening as banks were practically not lending. There was a severe draught in the international financial system.

The Brooks loan is interesting. It can be seen as an “insurance” for al Thani that no matter what, he would never lose a penny. When things did go sour – the bank collapsed and all the rest of it – this money was used to unburden him of his personal guarantee. Otherwise, it would have been money in his pocket. It’s also interesting that the loan was paid out to Brooks on Sept. 19, his investment was announced on Sept. 22 – but the trade wasn’t settled until Sept. 29. This means that his “guarantee” was secured before he took the first steps to become a Kaupthing investor.

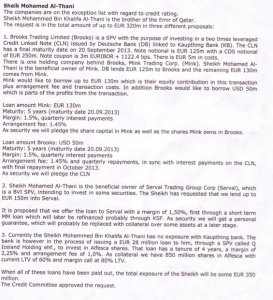

Apparently, Kaupting’s credit committee was in total oblivion of all this. The CC was presented with another version of reality. Below is an excerpt from the minutes regarding the al Thani loan, discussed when the Board of Kaupthing Credit Committee met in London Sept. 24. 2008 (click on the image to enlarge).

Three things to note here: that the $50m loan “is parts of the profits from the transaction.” Second, that al Thani borrowed €28m to invest in Alfesca. It so happens that Alfesca belonged to Olafsson. Al Thani’s acquisition in Alfesca was indeed announced in early summer of 2008 and should, according to rules, have been settled within three months. At the end of Oct. 2008 it was announced that due to the market upheaval in Iceland al Thani was withdrawing his Alfesca investment. Thirdly, it’s interesting to note that Deutsche bank did lend into this scheme – as it also did into another remarkable Kaupthing scheme where the bank lent money to Olafsson and others for CDS trades, to lower the bank’s spread; yet another untold story.

According to the OSP writ, the covenants of the al Thani loans differed from what the CC was told. It’s also interesting to note that the $50m loan to al Thani’s company was paid out on Sept. 19, five days before the CC meeting. This fact doesn’t seem to have been made clear to the CC.

The OSP writ also makes it clear that any eventual profits from the investment would have gone to Choice Stay, owned by Olafsson and the two al Thanis.

Why did al Thani pop up in September 2008? It seems that he was a friend of Olafsson who has is said to have extensive connection in al Thani’s part of world. Olafsson’s Middle East connection are said to go back to the ‘90s when he had to look abroad to finance some of his Icelandic ventures. London is the place to cultivate Middle East connections and that’s also where Olafsson has been living until recently. It is interesting to note that the Financial Times reports on the indictments without mentioning the name of Sheikh al Thani.

The four indicted Icelanders are all living abroad. Sigurdur Einarsson lives in London and it’s not known what he has been doing since Kaupthing collapsed. Hreidar Mar Sigurdsson lives in Luxembourg where he, together with other former Kaupthing managers, runs a company called Consolium. His wife runs a catering company and a hotel in Iceland.

Magnus Gudmundsson also lives in Luxembourg. David Rowland kept him as a manager after buying Kaupthing Luxembourg, now Banque Havilland, but Rowland fired Gudmundsson after Gudmundsson was imprisoned in Iceland for a few days, related to the OSP investigation. In the Icelandic Public Records it’s said that Olafsson lives in the UK but he has now been living in Lausanne for about two years. In Iceland, he has a low profile but is most noted in horse breeding circles, a popular hobby in Iceland. He breeds horses at his Snaefellsnes farm and owns a number of prize-winning horses.

Following the indictment, Olafsson and Sigurdsson have stated that they haven’t done anything wrong and that the al Thani Kaupthing investment was a genuine deal. The case could come up in the District Course in the coming months. But perhaps this isn’t all: it’s likely that there will be further indictment against these four on other questionable issues related to Kaupthing.

*The OSP indictment, in Icelandic.

**Does it matter that the four indicted are all living abroad? When I made an inquiry at the Ministry of Justice in Iceland some time ago whether Icelanders, living abroad but indicted in Iceland, could seek shelter in any country in Europe by refusing to return to Iceland I was told they couldn’t. If an Icelandic citizen is indicted in Iceland and refuses to return, extradition rules will apply. In this case, Iceland would be seeking to have its own citizens extradited and such a request would be met. – It has been noted in Iceland how many of those seen to be involved in the collapse of the banks now live abroad. It can hardly be because they intend to avoid being brought to court – they would have to go farther. Ia it’s more likely they want to avoid unwanted attention. For those with offshore funds it might be easier to access them outside of Iceland rather than in a country fenced off by capital controls.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

CSSF, Kaupthing Luxembourg and Rowland: many questions, fewer answers

Icelandic banks grew and expanded abroad and caught attention in countries where they operated but they never got rid of rumours of dodgy dealings, of money laundering and Russian connections. In spring of 2006, the expansion of Icelandic banks and businesses in Denmark attracted attention, causing worries and consternation. According to a Danish source this was even discussed informally on the board of the Danish National Bank. All along, the only people who seemed totally oblivious to these rumours were the financial services authorities in the countries where the Icelandic banks operated.

And so it was in Luxembourg, at the Commission de Surveillance du Secteur Financier, CSSF, the financial services authorities of this tiny state, which builds its wealth on offshore operations at the heart of Europe.

Only a few weeks after the collapse of the Icelandic banks in October 2008 my attention was drawn to the banks’ operations in Luxembourg. I spent months trawling through the Mémorial/Tagesblatt, the official publication that lists information on Luxembourg companies. The banks, especially Kaupthing, had from 1999, set up hundreds of companies for their Icelandic clients. In 2005, Kaupthing started a successful UK operation, which meant that many of the bank’s largest UK clients also had accounts and companies in Luxembourg.

On a visit to Luxembourg last year, I gathered that the CSSF had been completely ignorant of what was going on in the Icelandic banks. It seemed that the CSSF had not had any insight into the fact that the banks breached the limits how much they could lend to each entity/person and the insufficient or no collaterals/guarantees.

However, I have recently learnt that this wasn’t the case at all. The CSSF was indeed very worried about the situation in the Icelandic banks, at least in Kaupthing and Landsbanki (the Glitnir operation in Luxembourg was never big, it came too late to the game). So worried, that following the Q1 result in 2008 CSSF asked the external auditors of the two banks for a thorough report, ia on credit risk.

How Landsbanki responded I do not know but if they met the CSSF as they met demands from the UK FSA it’s safe to conclude that they were neither swift nor forthcoming. Kaupthing Luxembourg managers dragged their feet. The deadline was in June 2008, the report wasn’t finished until the latter half of July. The report was based on Kaupthing’s position at the end of March. The CSSF didn’t like what they saw but in reality the situation, by late summer 2008, was much worse than the report indicated since the underlying numbers had changed much for the worse.

Kaupthing answered in the Kaupthing way, claiming that the CSSF was entirely wrong about essential things. There was, according to the Kaupthing Luxembourg management nothing wrong and the credit risk well managed. However, Kaupthing Luxembourg was in the end forced to sell assets, providing some much needed liquidity. On Friday October 3 Kaupthing Luxembourg manager Magnus Gudmundsson told some employees that the Luxembourg operations were now secured for the coming months.

Evidently, Kaupthing’s management also convinced people at the Central Bank of Iceland that Kaupthing was, contrary to Glitnir and Landsbanki, in a strong position to weather the storm. On Monday 6 October 2008 the CBI agreed to provide Kaupthing a loan of €500m. Considering the fact that Kaupthing, as well as Landsbanki, was from Friday 3 October forced to put all new deposits into Bank of England, meaning that the banks were no longer operating freely, the loan is incomprehensible. I’ve never been able to certify if the CBI knew about the BoE action but my conclusion is that the CBI must have been aware of it.

It’s never been explained what happened to the €500m. Some of it seems to have gone to Sweden, some of it to Luxembourg. But the real mystery is why this money wasn’t used to save Kaupthing by strengthening Kaupthing Singer & Friedlander. Due to cross default clauses it was clear that if KSF collapsed it would trigger a Kaupthing default. KSF and Kaupthing were in a dialogue with the FSA during the last days. FSA set certain conditions for liquidity, Kaupthing claimed it could meet the limits but never did. Not even when it had the €500m.

But back to Luxembourg in October 2008. Although CSSF had been chasing Kaupthing for credit risk and over-exposure to only a few clients it didn’t seem too concerned about the way the Kaupthing managers had run the bank. Kaupthing went into administration, Franz Fayot, a well connected Luxembourg lawyer, was appointed an administrator. But little changed at the bank where Gudmundsson and the other Icelanders kept on running the bank. Apparently, no questions were asked, in spite of CSSF serious doubts.

After JC Flowers and the Libyan Investment Agency had considered buying Kaupthing but decided against it, the English investor, David Rowland finally took Kaupthing over. His bank, Banque Havilland now acts as an administrator for the Kaupthing assets in Pillar Securitisation. The Luxembourg state risked a loan of €320m to facilitate the deal with Rowland, again no questions asked in spite of CSSF’s earlier doubts and worries.

Rowland fired all his Icelandic employees, except one, after the Office of the Special Prosecutor arrested Gudmundsson last year. The message was that Iceland wasn’t important for Havilland any longer. Yet, suddenly Rowland appeared as an investor in an Icelandic bank, the resurrected MP bank. Rowland seems to have an exotic interest in outliers, investing in Iceland and Belarus. MP bank has invested in Ukraine and the Baltic countries. The question is why Rowland, who was called ‘shady’ in the UK Parliament, is suddenly so interested in Iceland and a bank there.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Rowland and Jo Lewis shareholders in MP bank in Iceland

After buying Kaupthing Luxembourg, the object of serial searches by the Icelandic Special Prosecutor and now also the UK Serious Fraud Office, David Rowland hasn’t lost the appetite for Icelandic banks with a questionable reputation. He, together with the ex-Kaupthing Singer & Friedlander client, Jo Lewis, is buying 10% of the Icelandic bank MP Bank, according to Vidskiptabladid, the Icelandic business newspaper.

MP bank survived the crash but now needs more equity. A group of Icelandic shareholders, led by Skuli Mogensen, earlier CEO of Oz. Oz was an Icelandic dotcom venture in the 90s that a huge number of Icelanders lost money on in a case that was never investigated. According to Vidskiptabladid, the Icelanders have procured 10% from Rowland, Lewis and a third foreign investor who hasn’t been named.

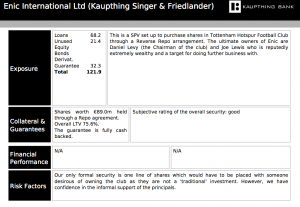

According to the leaked Kaupthing loan book, Lewis and Daniel Levy, through their holding company Enic, had a loan facility with KSF of €121.9 million, in a ‘reverse repo’ arrangement, against a collateral in shares in their trophee asset Tottenham Hotspur, worth only €89m, meaning the loan was only partly covered. A note on the risk read: “Our only formal security is one line of shares which would have to be placed with someone desirous of owning the club as they are not a traditional investment.” I.e., the collateral was highly illiquid. Yet, it said that the subjective rating of the collateral was ‘good.’

Lewis and Levy, the chairman of the club, used the loan to raise their stake in Tottenham to 84% in 2007, the year of golden deals. It is fair to say that by receiving this loan, Lewis and Levy had firmly placed themselves as clients that KSF wanted to keep happy with good deals, or as it read in the loan book: “Joe Lewis is reputedly extremely wealthy and a target for doing further business with.’ I.e. KSF wanted to smooze up to Lewis by offering him a bit of something extra.

From any normal business perspective it beggars belief that Rowland, now teamed up with Lewis, would want to buy into a bank in Iceland. A bank under scrutiny from the regulator where the MP himself, its founder Margeir Petursson a famous chess player, has resigned. Petursson had until last year an image of being whiter than snow in the Icelandic business community. There is now some ash on the snow. Deals between MP bank and Byr, a saving society, are part of charges that the Office of the Special Prosecutor has pressed i.a. against the former MP CEO. In addition, Rowland and Lewis are buying into a bank in a country with capital restrictions. Rowland, through Havilland, is investing in Belarus. MP operates in Ukraine.

There have been consistent rumours that Rowland bought Kaupthing Luxembourg as a front man for someone else. Rowland has always denied this, saying the bank is his and his alone. These rumours will flare up now that he moves to buy shares in MP bank. Hasn’t Rowland had enough of buying into Icelandic banks with questionable reputation? But at least, he will recognise the Special Prosecutor Olafur Hauksson if ever he meets him in the corridors of MP Bank.

Here is the page from the Kaupthing loan book, on the Enic loan (click on it to enlarge):

*An update: the third investor is a Canadian tax lawyer, Robert Raich, with no apparent Icelandic connections.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

SFO and OSP: further searches in Luxembourg

According to a press release from the SFO there have been house searches in Luxembourg today, on request from both the Serious Fraud Office and the Office of the Special Prosecutor in Iceland. The operation has involved 70 investigator, from the Luxembourg Police, SFO and the OSP.

The searches per se are interesting – and also the fact that this is a joint operation, involving the three countries. It remains to be seen if the Luxembourg authorities will now be opening up an investigation of its own. However, this doesn’t mean that the investigations in Iceland and the UK are being merged. It’s still separate investigations but forces are combined when practical.

It seems that the SFO is conducting house searches at Consolium, where some ex-Kaupthing managers run a consultancy. On the Consolium team there are the following: Hreidar Mar Sigurdsson, Ingolfur Helgason, Steingrimur Karason, Gudmundur Thor Gunnarsson (arrested in Iceland in connection to the SFO searches recently) and Kristinn Eiriksson. The OSP is focusing further on Skuli Thorvaldsson and searched Banque Havilland.

In february last year the OSP did house searches in Luxembourg in an operation that was, at the time, one of the largest of its kind in Luxembourg. Some 19 parties did at the time protest the handing over of the documents and it took the OSP the best part of a year to get the documents, after the 19 took their case to an appeal court. However, since then the rules in Luxembourg have been changed and it’s no longer possible to appeal. It means that this time the process to get the documents could take no more than a few months, not a year like last time.

Update: here is how the Guardian reported on the searches.

Further update: the searches were at two homes and three work places. The homes were those of Hreidar Mar Sigurdsson ex-CEO of Kaupthing and Magnus Gudmundsson manager of Kaupthing Luxembourg. The three work places were Havilland, Consolium and the third place, so far unidentified.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Rowland in royal company

Prince Andrew has a special talent for choosing friends. First there was the American millionaire Jeff Epstein, convicted for sexual relationships with under-age girls. Now it turns out, according the Telegraph, that David Rowland, owner of Banque Havilland earlier Kaupthing Luxembourg, has paid off debt of £85,000 for the prince’s ex-wife. Previously, prince Andrew had attended the opening of Banque Havilland, as seen on this photo from Havilland’s annual report 2009.

Rowland’s royal connection, in addition to his ties to the Conservative party is a further example of Rowland’s influence in high places although he, as quoted in the Telegraph article, has been accused of looting a company that he once bought in the US, Rowland denies this, and further has been called “shady” in Parliament.

As long as leaders of the political parties are so in awe of millionaires with shady money and shady money supports political parties it’s a struggle to investigate people and companies that get rich in an opaque way. Something that The Economist highlighted in a brilliant satire this week. As they point out, “respectability is on sale” – and the best market place is indeed London. The ties between prince Andrew, Rowland and the Conservative party, the debt and indebtedness involved, are a case in point.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Who tried to prevent the OSP getting the Luxembourg documents?

It’s now clear who, apart from Banque Havilland, tried to hinder the Office of the Special Prosecutor in Iceland to get access to the documents from Kaupthing Luxembourg, now the Rowland family’s Banque Havilland that bought Kaupthing’s Luxembourg subsidiary. Earlier, when I inquired at the courts in Luxembourg I was told that only those connected to the case could get the verdict. Now, Vidskiptabladid Iceland, has obtained a copy of the verdict.

Unsurprisingly, both Kaupthing’s CEO and chairman of the board, Hreidar Mar Sigurdsson and Sigurdur Einarsson, tried to hinder the OSP to get the documents obtained via house searches a year ago. Another paper, DV, wrote today the the OSP had been very successful in finding documents at the home of Magnus Gudmundsson, who was Kaupthing Luxembourg manager and stayed on at Havilland. Some of the documents were in Gudmundsson’s car. (If you ever drive in an ex-Kaupthing manager’s car look around and try to get a peep into the booth.) Gudmundsson however is not on the OSP ‘opposition team.’

Others in this team are Olafur Olafsson,* the second largest shareholder in Kaupthing and four companies owned by him: Sable Air APS Denmark and three BVI companies, Marine Choice Ltd, Fort Shannon Ltd and Fordace Ltd. In addition there are Skuli Thorvaldsson, Egill Agustsson and his business partner Einar Bjarni Sigurdsson, living in Denmark.

This is quite an intriguing circle of business men. All these people, apart from Einar Bjarni, are names that are already connected to alleged market manipulation and other manipulation by Kaupthing. It’s save to conclude that this is a group of men who formed a close network at the core of deals that the OSP is investigating.

Olafsson was connected to the al-Thani deal: a sheikh from the Qatar ruling family bought 5% in Kaupthing in a highly publicised deal in early September 2008. But instead of the deal showing the sheikh’s believe in Kaupthing it apparently showed that the bank was unable to sell any shares except by offering ‘risk-free’ loans (the risk was all on the bank, making these deals look like a breach of fiduciary duty on behalf of the bank’s management). The sheikh also got a loan of $50m towards future profits. Needless to say there were no future profits only imminent losses. Olafsson got the sheikh another Kaupthing loan to buy shares in Alfesca, where Olafsson is a major shareholder, also a highly publicised deal that then came to nothing. – Olafsson still holds his interests in Alfesca where the chairman is Arni Tomasson chairman of the Glitnir’s ResCom. Olafsson, who earlier lived in London, now lives in Switzerland.

Skuli Thorvaldsson had an interesting relationship with Kaupthing. He has been living in Luxembourg for decades and wasn’t known for being fabulously wealthy. His branch has been property investment. His connection with Kaupthing first became clear when the loan overview from Sept. 08 was leaked on Wikileaks. The SIC made it known that Thorvaldsson was Kaupthing’s biggest debtor in Luxembourg, pretty staggering considering his apparently low key property business. His loans with Kaupthing peaked at €200m just before the collapse of the banks. Thorvaldsson was also involved in Kaupthing plots to lower its CDS: the bank lent Thorvaldsson huge sums through a web of companies enabling Thorvaldsson to buy CDS and affect the bank’s CDS spread. An audacious attempts that Deutsche Bank was involved in – Kaupthing managers claim the idea came from DB but DB claims it, unaware of the aim, only advised these structures. Kevin Stanford and Olafsson were also involved in these CDS acrobatics – and yes, DB’s role is, ahem, interesting.

Agustsson’s business partner is otherwise unknown but Agustsson is connected to companies that were close to Kaupthing and their habit of lending to companies, most noticeably a company called Desulo that has featured in an earlier Icelog on the deals Agustsson and others from the OSP ‘opposition’ were engaged in.

Unsurprisingly, it turns out that those who tried to hinder the OSP to obtain the documents are all, except Banque Havilland, part of Kaupthing’s inner circle, connected to deals and companies that the OSP is investigating.

*4.3.’08: Olafsson has issued a statement saying that he didn’t oppose the handing over of documents to the OSP but that he opposed that documents unrelated to issues being investigated should be handed over.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Once upon a time

As I have mentioned, president Olafur Ragnar Grimsson’s critics claim that by taking stance on the Icesave issue he’s diverting attention from widespread criticism for his previous involvement with discredited business leaders, some of whom are now under investigation for alleged fraud. Below is a photo* from this past. From the beginning, he emphasised that his role in promoting Icelandic businesses abroad. Few would contend with this role, after all head of states and leading politicians mostly do it. But some will feel that Grimsson got a bit to cosy with some of the Icelandic business leaders who have lost their reputation.

The one person truly out of place on this photo is Finland’s president Tarja Halonen to whom these leading lights of Icelandic business life ca 2004-2007 were clearly being presented. Far left is Robert Wessman, who was probably the CEO of Actavis at the time of this meeting. Wessman bought shares in Glitnir for ISK6bn a few days before the bank collapsed. ‘Sometimes you gain, sometimes you loose,’ he said stoically on tv after this disastrous deal became known. Considering what we now know about how the banks lent their favourite clients to buy shares there might still be something unknown about this deal. Wessman, the only businessman on the photo still living in Iceland, is now embroiled in law suits with his former boss and business partner Bjorgolfur Thor Bjorgolfsson. The cases regard Wessman’s departure from Actavis. The two were earlier close enough to co-invest in property deals in Spain that failed, possibly an added source of discontent between the two.

Next to Wessman is Hannes Smarason, apparently ill at ease in his unsharp suit. After working for McKinsey in the US, whereby he gained a lot of credibility, Smarason returned to Iceland in the late ’90s to be a CFO at deCode. He has denied that he and deCode’s CEO Kari Stefansson were the middlemen when deCode sold shares in the grey market before floating on the Iceland Stock Exchange. SEC filings show that the sale was conducted through a Luxembourg company, Biotek Invest. When Biotek Invest was dissolved by a Panama company it held almost $40m. Smarason later left deCode to join the rising business star of the early ’00s, Jon Asgeir Johannesson. They bought into Icelandair, sold the air business in 2004 and started on a shortlived investment spree. By the end of 2007 FL Group had failed and Smarason left the company. Since then, no big stories, except from the past, have been heard of Smarason who lives in London. It’s believed that matters related to Smarason are being investigated by the Office of the Special Prosecutor in Iceland. Smarason is also one of the defendants in the Glitnir case in New York that now seems to be about to be reopened after being dismissed last December.

On Halonen’s right is the ever photogenic sharp dresser Bjorgolfur Thor Bjorgolfsson. The formerly so fabulously wealthy major shareholder in the two failed banks Landsbanki and Straumur is still, at least on paper, connected to Actavis, the pharmaceutical company that he built up and then took off the market in summer 2007. However, it seems that Deutsche Bank, Actavis main creditor (Landsbanki took part in financing the Actavis deal but the deal was constructed in such a way that the bank was left with nothing, according to Landsbanki’s ex-CEO Sigurjon Arnason, when Actavis ran into trouble). The fact that Bjorgolfsson’s father, his co-investor in the two banks, was jailed for fraud in the ’80s seems to have made Bjorgolfsson determined that money and respect went hand in hand. He still has money but in Iceland there isn’t much left of the respect. He runs an Icelandic website to explain his side of the matters. I’ve been told that he’s preparing to write a book, both in Icelandic and English, telling his version of the Icelandic fall (in interviews he has blamed everyone except himself but in the report of the Special Investigative Commission some of those involved in the events in October 2008 have said that at that time Bjorgolfsson lied to them about the state of Landsbanki) but his spokespersons say that though he keeps track of things no book plans are confirmed. Bjorgolfsson has been involved in real estate companies in Denmark where an old friend of his, and co-investor both with Bjorgolfsson and Johannesson, Birgir Bieltvedt lives. Bjorgolfsson lives in London and has an office in Mayfair.

Hreidar Mar Sigurdsson was the CEO of Kaupthing. Sigurdsson now lives in Luxembourg and, together with other ex-Kaupthing employees, runs an investment/consulting company there called Consolium. Sigurdsson was held in custody last year in connection to an ongoing OSP investigation into Kaupthing. Consolium has been very close to Banque Havilland, owned by the Rowland family who are the administrators for Pillar Securitisation, the bad debt part of Kaupthing Luxembourg that the Rowlands bought. These close ties – the Rowlands kept Kaupthing Luxembourg’s manager Magnus Gudmundsson until he was remanded to custody like Sigurdsson – have led to speculations about the ties between the Rowlands and Kaupthing’s key managers and major shareholders like Exista og and Olafur Olafsson.

Two and a half years after the collapse of the banks, these five business men – and to some extent Grimsson – are still very much defined by the events of 2008 and their questionable success in the short lived once upon a time of an Icelandic business boom.

*I can’t credit the photographer since there wasn’t any name with the photo but I guess it’s an official photo from the office of the Finnish president.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

150 kg of Luxembourg documents

Yesterday, the Office of the Special Prosecutor formally received the documents that the Appeal Court in Luxembourg recently ruled that could be handed over to the OSP. The documents were seized during three days of house searches at Kaupthing Luxembourg, now Banque Havilland, and other locations. Who those 19 parties are who, together with Banque Havilland, tried to oppose the handing-over still remains in the dark.

The paper documents weigh 150 kg but in addition to that there are electronic documents. Needless to say, these are copies so the Luxembourg authorities retain the documents as well. Due to security, the OSP didn’t announce that they had the documents until after they received them.

This being a prosecutor’s office there was most surely no champagne to celebrate. The real feast lies in the 150 kg of documents and the electronic data.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

OSP: major breakthrough re Kaupthing Luxembourg

The Supreme Court in Luxembourg has now ruled that the documents from Kaupthing Luxembourg, demanded by the Office of the Special Prosecutor in Iceland after house searches in Luxembourg in February last year, can be handed over to the OSP. The documents, mostly found at Banque Havilland that in summer 2009 took over the operation of Kaupthing, are thought to be related to loans, accounts and transactions connected to Kaupthings’ major clients, owners and the bank’s senior management.

The house searches in Luxembourg by the local police are one of the most extensive searches ever done in Luxembourg. Afterwards, the rumour was that the OSP had found documents far beyond what they had hoped for and had their eyes on a lot more than they had originally in mind. The process has been a lengthy one. First, a judge had to review the documents to see if the search warrant applied to them. That took until autumn, as far as I understand. Then it turned out that parties, to whom the documents related, could try to veto the handing over of the documents.

The result was that Banque Havilland, that had earlier said they would try to be as accommodating to the OSP as possible, together the 19 parties (no names have been mentioned but I would be very interested in see a list of these 19 names) asked that the documents shouldn’t be released. Interestingly, Banque Havilland said after the searches that they would cooperate fully with the OSP. The fact that Havilland took a lead in attempting to hinder the OSP to get the documents tells another story. The attempted veto had to go through a county judge, that ruled in favour of the OSP. That ruling was appealed. Today, Banque Havilland and the 19 lost the appeal. Now, the OSP will get the coveted documents in the coming days.

What might the Kaupthing documents contain? Already, the 25.9. 2008 loan overview from Kaupthing, leaked on Wikileaks in summer of 2009, showed that loans to parties with bad credit ratings, against no or insufficient guarantees and collaterals, almost all went through Kaupthing Luxembourg. The report of the Althingi Special Investigative Committee confirmed this.

It seems clear that the most opaque dealings of Kaupthing were dealt with in Luxembourg. Someone familiar with Kaupthing’s operations recently told me that Kaupthing can’t be fully understood without a full insight into the bank’s Luxembourg operations. That’s what the OSP surely knew when the Luxembourg house searches were done last year. It now remains to be seen if some of the senior management of the bank, some of whom were held in custody last year for questioning, will be questioned again in the light of a fuller picture emerging.

For Luxembourg itself, the High Court ruling is of major importance. Lately, I’ve heard that some individuals in Luxembourg are scrutinising certain individuals and companies in order to bring into the open certain allegedly questionable or even criminal activities in the financial sector. It’s now clear that banks can’t hide behind the Luxembourg bank secrecy anymore. Nor should they. Innumerable banks and financial institutions have for decades used Luxembourg to run offshore operations at the centre of Europe. When I was in Luxembourg early last summer I met many locals who weren’t at all happy with the fact that their country had become a synonyme of a place to do dirty deals. The ruling today shows that when a case is supported by sound reasons the Luxembourg High Court agrees.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.