Search Results

Iceland, Russia and Bayrock – some facts, less fiction

Contacts between Iceland and Russia have for almost two decades been a source of speculations, some more fancifully than others. The speculations have now again surfaced in the international media following the focus on US president Donald Trump and his Russian ties: part of that story involves his connections with Bayrock where two Icelandic companies, FL Group and Novator, are mentioned. Contrary to the rumours at the time, Icelandic expansion abroad up to the banking collapse in 2008 can be explained by less sensational sources than Russian money – but there are some Russian ties to Iceland.

“We have never seen businessmen who operate like the Icelandic ones, throwing money around as if funding was never a problem,” an experienced Danish business journalist said to me in 2004. From around 2002 to the Icelandic banking collapse in October 2008, the Icelandic banks and their largest shareholders attracted attention abroad for audacious deals.

The rumours of Russian links to the Icelandic boom quickly surfaced as journalists and others sought to explain how a tiny country of around 320.000 people could finance large business deals by Icelandic businesses abroad. The owners of one of Iceland’s largest banks, Landsbanki, father and son Björgólfur Guðmundsson and Björgólfur Thor Björgólfsson, had indeed become rich in Saint Petersburg in the 1990s.

The unequivocal answer on how the foreign expansion of Icelandic banks and businesses was funded came in the Special Investigative Commission Report, SICR, in 2010: the funding came from Icelandic and international banks; the Icelandic banks found easy funding on international markets, the protagonist were at the same time the banks’ largest shareholders and their largest borrowers.

The rumours of Russian connections have surfaced again due to the Bayrock saga involving US president Donald Trump and his relations to Russia and Russian mobsters. Time to look at the Icelandic chapter in the Bayrock saga and Russian Icelandic links.

The Bayrock saga

By now, there is hardly a media company in the world that has not paid some attention to Donald Trump and Bayrock, with a mention of the Icelandic FL Group and the Russian money in Icelandic banks and businesses. The short version of that saga is the following:

Tevfik Arif, born in Kazakhstan during the Soviet era, was a state-employed economist who turned to hotel development in Turkey in the 1990s before moving into New York property development where he founded Bayrock in 2001. As with many real estate companies Bayrock’s structure was highly complex with myriad companies and shell companies, on- and offshore.

Arif hired a Russian to run Bayrock. Felix Sater or Satter was born in Russia in but moved to New York as youngster with his family. In 1991 Sater was sentenced to prison for a bar brawl cutting up the face of his adversary with a broken glass. Having admitted to security fraud in cohort with some New York Mafia families in 1998 he was eventually found guilty but apparently got a lenient sentence in return for becoming an informant for the law enforcement.

In 2003, Arif and Sater were introduced to a flamboyant property developer by the name of Donald Trump, already a hot name in New York. One of their joint projects was the Trump Soho. The Trump connection did attract media attention. Apparently following a New York Times profile of Sater in December 2007, unearthing his criminal records, Arif dismissed Sater in 2008.

Bayrock and FL Group

By then, another scheme was brewing and that is where the Icelandic FL Group enters the Bayrock and Trump story. This part of the story has surfaced in court cases, still ongoing, where two ex-Bayrock employees, Jody Kriss and Michael Ejekam, are suing Bayrock for cheating them of profit inter alia from the Trump SoHo deal.

Their story details complicated hidden agreements whereby Arif and Sater, according to Kriss and Ejekam, essentially conspired to skim off profit from Bayrock, cheating everyone who entered an agreement with them. According to the story told in the court documents (see inter alia here) Bayrock entered an agreement with FL Group in May 2007: for providing a loan of $50m FL Group would get 62% of the total profits from four Bayrock entities, expected to generate a profit of around $227.5m.

The loan arrangement with FL Group did not make a great financial sense for Bayrock, again according to Kriss and Ejekam, but it was part of Arif and Sater’s scheme to cheat investors as well the US tax authorities. When Kriss complained to Sater that the $50m loan from FL Group was not distributed as agreed, Sater “made him (Kriss) an offer he couldn’t refuse: either take $500,000, keep quiet and leave all the rest of his money behind, or make trouble and be killed.” – Given Sater’s criminal record and threats he had made to another Bayrock partner Kriss left Bayrock.

The short and intense FL saga and its record losses

FL Group was one of the companies that formed the Icelandic boom. Out of many financial follies in pre-crash Iceland the FL Group saga was one of the most headline-creating. In 2002 Jón Ásgeir Jóhannesson, of Baugur fame, bought 20% in the listed air carrier Flugleiðir. In 2004 he teamed up with Hannes Smárason who with a degree from the MIT and four years at McKinsey in Boston had a stellar CV.

Smárason was first on the board until he became a CEO in October 2005. The duo oversaw the take-over of Flugleiðir, sold off assets and turned the company into an investment company, FL Group; inter alia FL Group was for a short while the largest shareholder in EasyJet.

In spring 2007, a group of investors led by Jóhannesson became the largest shareholder in Iceland’s third largest bank, Glitnir. Their Glitnir holding was through FL Group, consequently the bank’s largest shareholder.

At the beginning of 2007, the FL Group debt with the Icelandic banks amounted to almost €600m but had risen to €1.1bn in October 2008. Interestingly, its debt to Glitnir rose by almost 800%. As mentioned above, Jóhannesson and his business partners, among them FL Group, became Glitnir’s largest shareholder in spring 2007, following the pattern that the banks’ largest shareholders were also their largest borrowers.

FL Group – folly or a classic “pump and dump”?

By the end of 2007, 26 months after Hannes Smárason became CEO, FL Group had set an Icelandic record in losses: ISK63bn, now €660m, ten times the previous record, from 2006, incidentally set by a media company controlled by Jóhannesson.

Facing these stunning losses Smárason left FL Group in December 2007. The story goes that at the shareholders’ meeting where his departure was announced he left the room waving, saying “See you in the next war, guys” (In Icelandic: “Sjáumst í næsta stríði, strákar).

There are endless stories of staggering cost and insane spending related to the FL Group boom and bust. Interestingly, a large part of the losses stemmed from consultancy cost for projects that never materialised. Smaller investors lost heavily and in hindsight the question arises if the FL saga was a folly or some version of a “pump and dump.” Smárason was charged with embezzlement in 2013, acquitted in Reykjavík District Court but the State Prosecutor’s appeal was thrown out of the Supreme Court due to the Prosecutor’s mistakes.

FL Group never recovered from the losses and was delisted in the spring of 2008 and its name changed to Stoðir. FL Group never went into bankruptcy but its debt was written off. A group of earlier FL Group managers (Smárason is not one of them) now owns over 50% of Stoðir.

FL Group and the Icelandic Bayrock

Part of FL Group’s eye-watering losses was the Bayrock adventure. FL Group set up a company in Iceland, FL Bayrock Holdco, financed by the Icelandic mother company. Already in 2008 the FL Group Bayrock was a loss-making enterprise, its three FL Bayrock US companies were written off with losses amounting to ISK17.6bn, now €157m. When the Icelandic FL Bayrock finally failed in January 2014 Stoðir (earlier FL Group) was more or less the only creditor, its claims amounting to ISK13bn; no assets were found.

According to the Kriss-Ejekam story, FL Group willingly and knowingly took part in a scam. When I approached a person close to FL Group, he maintained the investment had not been a scam but just one of many loss-making investments, not even a major investment, compared to what FL Group was doing at the time.

An FL Group investor told me that he had never even heard of the Bayrock investment until the Trump-related Bayrock stories surfaced. He expressed surprise that such a large investment could have been made without the knowledge of anyone except the CEO and managers. He added however that this was perhaps indicative of the problems in FL Group: managers making utterly insane and ill-informed decisions leading to the record losses.

Bayrock and Novator

Another Icelandic company, mentioned in the Kriss-Ejekam case is Novator, which was offered to participate in Bayrock. There is a whole galaxy of Novator companies, inter alia 19 in Luxembourg, encompassing assets and businesses of Björgólfur Thor Björgólfsson.

This, according to court documents (emphasis mine):

During the early FL negotiations, Bayrock was approached by Novator, an Icelandic competitor of FL’s, which promised to go into the same partnership with Bayrock as FL was contemplating, and at better terms. Arif and Satter told Kriss that this would not be possible, because the money behind these companies was mostly Russian and the Russians behind FL were in favor with Putin, but the Russians behind Novator were not, and so they had to deal with FL. Whether or not this was true and what further Russian involvement existed must await disclosure.

This is the clause that has yet again fuelled speculations of Russian dirty money in the Icelandic banks and Icelandic companies. As stated in the last sentence this is however all pure speculation.

The story from the Novator side is a different one. In an email answer to my query, the spokeswoman for Björgólfsson wrote that Bayrock approached Novator Properties, which considered the project far from attractive. Following some due diligence Novator concluded that the people involved were not appealing partners, which led Novator to decline the invitation to participate.

The origin of rumours of corrupt Russian connections to Iceland

Towards the end of 2002 the largest Icelandic banks and their main shareholders were already attracting foreign media attention. Euromoney (paywall) raised “Questions over Landsbanki’s new shareholder” in November 2002 focusing on the story of the father and son Björgólfur Guðmundsson and Björgólfur Thor Björgólfsson, who with their business partner Magnús Þorsteinsson struck gold in Saint Petersburg in the 1990s and were now set to buy over 40% of privatised Landsbanki.

The two businessmen, the Brit Bernard Lardner and his Icelandic partner Ingimar Ingimarsson, who in the mid 1990s had hired the three Icelanders to run their joint Saint Petersburg venture, were less lucky. In 2011 Ingimarsson published a book in Iceland, The Story that Had to be Told, (Sagan sem varð að segja), where he tells his side of the story: how father and son through tricks and bullying took over the Lardner and Ingimarsson venture, essentially the story told in Euromoney in 2002 (see earlier Icelog).

In June 2005, Guardian’s Ian Griffith wrote an article on the Icelandic businessmen Björgólfsson and Jón Ásgeir Jóhannesson, ever more visible in the London business community, asking where the Icelandic “Viking raiders” as they were commonly called got their money from, hinting at Russian mafia money. The quick rise to riches, wrote Griffith, exposed the Icelanders to “the persistent but unsubstantiated whispering that the country’s economic miracle has been funded by Russian mafia money rather than growth and liberalisation.”

As Griffith points out, Björgólfsson and his partners were operating in Saint Petersburg, “the city regarded as the Russian mafia capital. That investment was being made in the drinks sector, seen by the mafia as the industry of choice.

Yet against all the odds, Bravo went from strength to strength.

Other St Petersburg brewing executives were not so fortunate. One was shot dead in his kitchen from the ledge of a fifth-floor window. Another perished in a hail of bullets as he stepped from his Mercedes. And one St Petersburg brewery burned to the ground after a mishap with a welding torch.

But the Bravo business, run by three self-confessed naives, suddenly found itself to be one of Russia’s leading brewers. In under three years it became the fastest-growing brewer in the country. It secured a 17% market share in the St Petersburg region and 7% in the Moscow area. It was selling 2.5m hectolitres of beer a year in 2001 and heading for 4m when Heineken of the Netherlands stepped in to buy it for $400m in 2002. Heineken said one of the reasons for the Bravo purchase was the absence of any corruption.”

Björgólfsson has always vehemently denied stories of his alleged links to the Russian dark forces and Ingimarsson’s story. Billions to Bust and Back, published in 2014, is Björgólfsson’s own story of his life. The book has not been published in Iceland.

The Icelandic miracle exposed: international banks and “favoured clients”

During the Icelandic boom years Griffith was not the only one to question how the tiny economy of tiny Iceland could fund the enormous expansion of Icelandic banks and businesses abroad. The Russian rumours were persistent, some of them originating in the murky London underworld, all to explain this apparently miraculous growth. Most of this coverage was however more fiction than facts (the echo of this is found in my financial thriller, Samhengi hlutanna, which takes place in London and Iceland after the collapse, published in Iceland in 2011; English synopsis.)

The Icelandic Special Investigative Commission Report, SICR, published in April 2010, convincingly answered the question where the money came from: “Access to international financial markets was, for the banks, the principal premise for their big growth,” facilitated by their high credit ratings and Iceland’s membership of the European Economic Area, EEA. As to the largest shareholders the SICR concluded: “The largest owners of all the big banks had abnormally easy access to credit at the banks they owned, apparently in their capacity as owners… in all of the banks, their principal owners were among the largest borrowers.”

The story told in the SICR is how the Icelandic banks essentially ran a double banking system: one for normal bank clients who got loans against sound collaterals and loan contracts with normal covenants – and then another system for what I have called the “favoured clients,” i.e. the largest shareholders and their business partners.

The loans to the “favoured clients” were on very favourable terms, mostly bullet loans extended as needed, often with little or no collateral and light covenants. The consequence was that systematically, these clients profitted but if things went wrong the banks shouldered the losses. – In recent years, some of these abnormally favourable loans have sent around twenty bankers to prison.

The real Russian connections in Iceland

Although the Icelandic expansion abroad can be explained with less exciting facts than Russian Mafia and money laundering, there are a few tangible Russian contacts to Iceland: Vladimir Putin and the Kremlin did show an interest in Iceland at a crucial time, just as in Cyprus in 2013; Alisher Usmanov had ties to Kaupthing; the Danish lawyer Jens Peter Galmond, famous for his Leonid Reiman connections, and his partner Claus Abildstrøm did have Icelandic clients and Mikhail Fridman gets a mention.

At 4pm Monday 6 October 2008 prime minister and leader of the Independence party (conservative) Geir Haarde addressed Icelanders via the media: the government was introducing emergency measures to deal with the banks in an orderly manner. Icelanders sat glued to their tv sets struggling to understand the meaning of it all.

Haarde’s last words, “God bless Iceland,” brought home the severity of the situation. Icelanders had never heard head of government bless the country and never heard of measures like the ones introduced. The speech and the emergency Act it introduced came to be seen as the collapse moment – the three banks were expected to fail and by Wednesday 8 October they had all failed indeed.

An elusive Russian loan offer

The next morning, 7 October 2008 as Icelanders woke up to a failing financial system, the then governor of the Icelandic Central Bank, CBI, Davíð Oddsson, an earlier leader of the Independence Party and prime minister, told the still shocked Icelanders that all would be well: around 7am Victor I. Tatarintsev the Russian ambassador in Iceland had called Oddsson to inform him that the Russian government was willing to lend €4bn to Iceland, bolstering the Icelandic foreign reserves.

According to the CBI press release the loan would be at 30-50bp above Libor and have a maturity of three to four years. Later that day another press release just stated that representatives of the two countries would meet in the coming days to negotiate on “financial issues” – no mention of a loan.

According to Icelog sources, the morning news was hardly out when the CBI heard from news agencies that Russian minister of finance Alexei Kudrin had denied the story of a Russian loan to Iceland; indeed the loan never materialised though some CBI officials did fly out to Moscow a week later.

There have of course been wild speculations as to if the offer was real, why Kremlin was ready to offer the loan and then why Kremlin did, in the end, not stand by that offer.

Judging from Icelog sources it seems no misunderstanding that Tatarintsev mentioned a loan to Oddsson. As to why Kremlin – because that is where the offer did come from – wanted to lend or at least to tease with the offer is less clear though there is no lack of undocumented stories.

One story is that some Russian oligarchs did have money invested in Iceland. Fearing their funds would be inaccessible they pulled some strings but when they realised their funds were not in danger they lost interest in helping Iceland and so did Kremlin. Another explanation is that Kremlin just wanted to tease the West a bit, make as if it was stretching its sphere of interest further west. Yet another story is that a European minister of finance called his Russian counterpart telling him to stay away from Iceland; the European Union, EU would take care of the country.

Iceland found in the end a more conventional source of emergency funding: by 19 November 2008 it had secured $2.1bn loan from the International Monetary Fund, IMF.

Russia, Iceland and Cyprus

In 2013, Russia played the same game with Cyprus: it teased Cyprus with a loan. The difference was however that the Russian offer to Cyprus did not come as a surprise: Russia had long-standing and close political ties to the island. Russian oligarchs and smaller fries had for years made use of Cyprus as a first stop for Russian money out of Russia. At the end of 2011, Russia had lent €2.5bn to Cyprus. However, the crisis lending did not materialise, any more than it had in Iceland (see my Cyprus story).

The international media reported frequently that the EU and the IMF were reluctant to assist Cyprus because these organisations were irritated by the easy access of Russian funds to and through the island’s banks. A classified German report was said to show how Cyprus had been a haven for money laundering (if that report did indeed exist Germans could and should have used the same diligence to check their own Deutsche Bank!)

After the 2008 collapse in Iceland a credible source told me he had seen a US Department of Justice classified report on money laundering stating that Icelandic banks were mentioned as open to such flows. Given the credibility of the source I have no doubt that the report exists (though all my efforts to trace it have failed). I have however no idea if that report was thoroughly researched or not nor in what context the Icelandic banks were mentioned.

Kaupthing and Usmanov

Some Icelandic banks did have clients from Russia and the former Soviet Union. The only one mentioned in the SICR, is the Uzbek Alisher Usmanov. He turned to Kaupthing in summer of 2008 when he was seeking to buy shares in Mmc Norilsk Adr. According to the SICR the bank also sold Usmanov shares in Kaupthing – by the end of September 2008 he owned 1.48% in the bank.

I am told that Usmanov was not Kaupthing client until in the summer of 2008 (earlier Icelog). Funding was generally drying up but Kaupthing was keen on the connection as it was planning to branch out to Russia and consequently looking for Russian connections.

If Usmanov’s shareholding in Kaupthing comes as surprise it is important to keep in mind that part of Kaupthing’s business model was to lend money to clients to buy Kaupthing shares. This was no last minute panic plan but something Kaupthing had been doing for years.

This model, which looks like a share-parking scheme, is a likelier explanation for Usmanov’s stake in Kaupthing rather than a sign of Usmanov’s interest in Kaupthing. A Kauphting credit committee minute from late September 2008, leaked after the collapse, shows that Kaupthing had agreed to lend Usmanov respectively €1,1bn and $1.2bn. According to Icelog sources the bank failed before the loans were issued.

Fridman, Exista and Baugur/Gaumur

There are two Icelandic links to Mikhail Fridman, through Kaupthing and the investment bank Straumur. Its chairman, largest investor and eventually largest borrower was Björgólfur Thor Björgólfsson.

By 1998, Kaupthing was operating in Luxembourg. In June that year, a Luxembourg lawyer, Francis Kass, appeared twice on the same day as a representative of two BVI companies, Quenon Investments Ltd and Shapburg Ltd, both registered at the same post box address in Tortola. His mission was to set up two companies, both with names linked to the North: Compagnie Financiere Scandinave Holding S.A. and Compagnie Financiere Pour L’Atlantique du Nord Holding S.A. The directors were offshore service companies, owned by Kaupthing or used in other Kaupthing offshore schemes.

These two French-named companies, founded on the same day by the same lawyer, came to play major roles in the Icelandic boom until the bust in October 2008. The former was for some years controlled by Kaupthing top managers until it changed name in 2004 to Meiður and to Exista the following year. By then it was the holding company for Lýður and Ágúst Guðmundsson who became Kaupthing’s largest shareholders, owning 25%. In 2000, the latter company’s name changed to Gaumur. Gaumur was part of the Baugur sphere, controlled by Jón Ásgeir Jóhannesson.

The owners of Exista and Baugur were dominating forces in the years when Icelandic banks and businesses were on their Ikarus flight.

Apart from the UK, the Icelandic business expansion abroad was most noticeable in Denmark. Danish journalists watched with perplexed scepticism as swaggering Icelanders bought some of their largest and most eye-catching businesses. In Iceland, politicians and business leaders talked of Danish envy and hostility, claiming the old overlords of Iceland were unable to tolerate the Icelandic success. They were much happier with the UK press that followed the Icelandic rise rather breathlessly.

In 2006 the Danish tabloid Ekstra bladet wrote a series of articles again bringing up Russian ties. Part of the coverage related to the two Krass companies: Quenon and Shapburg have also set up Alfa companies, part of Mikhail Fridman’s galaxy of on- and offshore companies.

The Danish articles were translated into English and posted on the internet. Kaupthing sued the Danish tabloid, which was forced to retract the articles in order to avoid the crippling costs of a libel case in an English court.

JP Galmond – the fixer who lost his firm

An adversary of Fridman, with Icelandic ties, figures in a long saga where also Usmanov plays a role: the Danish lawyer, Jeffrey Peter Galmond. – Some of the foreign fixers who have worked for ex-Soviet oligarchs have in some cases lost their lives under mysterious circumstance. JP Galmond lost his law firm. His story has been told in the international media over many years (my short overview of the Galmond saga).

Galmond was one of the foreign pioneers in St Petersburg in the early 1990s where he soon met Leonid Reiman, manager at the city’s telephone company. By the end of 1990s many foreign businessmen had learnt there was not a problem Galmond could not fix. Reiman went on to become a state secretary in 1999 when Boris Jeltsin made his Saint Petersburg friend Vladimir Putin prime minister.

By 2000 the Danish lawyer had turned to investment via IPOC, his Bermuda-registered investment fund. The following year he bought a stake in the Russian mobile company Megafon. Soon after the purchase Mikhail Fridman claimed the shares were his. This turned into a titanic legal battle fought for years in courts in the Netherlands, Sweden, Britain, Switzerland, the British Virgin Islands and Bermuda.

In 2004 Galmond’s IPOC had to issue a guarantee of $40m to a Swiss court in one of the innumerable Megafon court cases. The court could not accept the money without checking its origin. An independent accountant working for the court concluded that the intricate web of IPOC companies sheltered a money-laundering scheme. In spring of 2008 IPOC was part of a criminal case in the BVI. That same spring, the Megafon battle ended when Alisher Usmanov bought IPOC’s Megafon shares.

The Megafon battle exposed Galmond as a straw-man for Leonid Reiman who was forced to resign as a minister in 2009 due to the IPOC cases. In 2007, Galmond was forced to leave his law firm due to the Megafon battle; his younger partner Claus Abildstrøm took over and set up his own firm, Danders & More, in 2008.

Galmond’s Icelandic ties

In spite of the international media focus on Galmond, he and his partner Claus Abildstrøm enjoyed popularity among Icelandic businessmen setting up business in Copenhagen. An Icelandic businessman operating in Denmark told me he did not care about Galmond’s reputation; what mattered was that both Galmond and Abildstrøm understood the Icelandic mentality and the need to move quickly.

Already in 2002, Abildstrøm had an Icelandic client, Birgir Bieltvedt, a friend and business partner of both Björgólfur Thor Björgólfsson and Jón Ásgeir Jóhannesson. In 2004 Abildstrøm assisted Bieltvedt, Jón Ásgeir Jóhannesson and Straumur investment bank, where Björgólfsson was the largest shareholder, to buy the department store Magasin du Nord, where Abildstrøm then became a board member.

In 2007, when the IPOC court cases were driving Galmond to withdraw from his legal firm, the Danish newspaper Børsen reported that among Galmond’s clients were some of the wealthiest Icelanders operating in Denmark, such as Björgólfur Thor Björgólfsson and Jón Ásgeir Jóhannesson.

In his book, Ingimar Ingimarsson claimed that Galmond acted as an advisor to Björgólfsson. According to an Icelog source Galmond represented a consortium led by Björgólfsson’s father Björgólfur Guðmundsson when they bought a printing press in Saint Petersburg in 2004. Björgólfsson has denied any ties to Galmond and to Reiman but has confirmed that Abildstrøm has earlier worked for him.

Alfa, Pamplona Capital Management and Straumur/Björgólfsson

Pamplona Capital Management is a London-based investment fund, which in late 2007 entered a joint venture, according to the SICR, with Straumur, an investment bank where Björgólfur Thor Björgólfsson was the largest shareholder, chairman of the board and Björgólfsson-related companies were eventually the largest borrower (SICR).

In 2005 Pamplona had bought a logistics company, ADR-HAANPAA, operating in the Nordic countries, the Baltics, Poland and Russia. In 2007 Straumur provided a loan of €100m to refinance ADR in a structure where Pamplona owned 80.8%, Straumur 7.7% and ADR managers the rest.

Pamplona was set up in 2004 by the Russian Alexander Knaster, who as a teenager had immigrated to the US with his parents. Knaster was the CEO of Fridman’s Alfa Bank from 1998 until 2004 when he founded Pamplona, partly with capital from Fridman. Knaster has been a British citizen since 2009 and has, as several other Russian billionaires living in the UK, donated money, £400.000, to the Conservatives.

Incidentally, Pamplona shares the same London address as Novator, Björgólfsson’s investment fund, according to Companies House data: 25 Park Lane is one of London’s most attractive business addresses.

The Icelandic business model: corrupt patterns v “time is money”

Big banks such as Wachovia and Citigroup have been fined for facilitating money laundering for Mexican gangs. Deutsche Bank as been fined recently for doing the same for Russians with ties to president Trump. All of this involves violating anti-money laundering rules and regulations and this criminal activity has almost invariably only been discovered through whistle-blowers. Since large international banks could get away with laundering money, could something similar have been going on in the Icelandic banks?

The Icelandic Financial Supervisor, FME, was famously lax during the years of the banks’ stratospheric growth and expansion abroad. One anecdotal evidence does not inspire confidence: during the boom years an Icelandic accountant drew the attention of the police to what he thought might be a case of money laundering in a small company operating in Iceland and offshore. The police seemed to have a very limited understanding of money laundering other than crumpled notes literally laundered.

However, the banking collapse set many things in motion. The failed banks’ administrators, foreign consultants and later experts at the Office of the Special Prosecutor have scrutinised the accounts of the failed banks landing some bankers and large shareholders in prison. I have never heard anyone with plausible insight and authority mention money laundering and/or hidden Russian connections.

I do not know if it was systematically investigated but some of those familiar with the failed banks would know that money laundering, though of course hidden, leaves a certain patterns of transactions etc. But most importantly, the banks’ operation in Luxembourg, where in the Kaupthing criminal cases the dirty deals were done, have not been scrutinised at all by Luxembourg authorities.

The Icelandic businessmen most active in Iceland and abroad were famous for two things: complex structures, not an Icelandic invention – and buying assets at 10-20% higher prices than others were willing to offer.

As one Danish journalist asked me in 2004: “Why are Icelanders always willing to pay more than the asking price?” The Icelandic businessmen explained this by “time is money” – instead of wasting time to negotiate pennies or cents it paid off to close the deals quickly, they claimed.

Paying more than the asking price, exorbitant consultancy fees, sales at inexplicable prices to related parties and complicated on- and offshore structures are all known characteristics of systematic looting, control fraud and money laundering – and there are many examples of all of this from the Icelandic boom years. But these features can also be the sign of abysmally bad management.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

The ‘puffin plot’ – a saga of international bankers and Icelandic greed

In a formal signing ceremony 16 January 2003 a group of Icelandic investors and the German bank Hauck & Aufhäuser purchased shares in a publicly-owned Icelandic bank. Paul Gatti represented the German bank, proudly airing the intension of being a long-term owner together with the Icelandic businessman Ólafur Ólafsson. What neither Gatti nor Ólafsson mentioned was that earlier that same day, at a meeting abroad, their representatives had signed a secret contract guaranteeing that the Icelandic bank Kaupthing, called ‘puffin’ in their emails, would finance the H&A purchase in Búnaðarbanki. A large share of the profit, 57,5 million USD, would accrue to Ólafsson via an offshore company, whereas 46,5 million USD was transferred to the offshore company Dekhill Advisors Limited, whose real owners remain unknown. Thus, Ólafsson and the H&A bankers fooled Icelandic authorities with the diligent help of advisors from Société General. – This 14 year old saga has surfaced now thanks to the Panama Papers. What emerges is a story of deception similar to the famous al Thani story, which incidentally sent Ólafsson and some of the Kaupthing managers involved in the ‘puffin plot’ to prison in 2015. Ólafsson is however still a wealthy businessman in Iceland.

The privatisation of the banking sector in Iceland started in 1998. By 2002 when the government announced it was ready to sell 45.8% in Búnaðarbanki, the agrarian bank, it announced that foreign investors would be a plus. When Ólafur Ólafsson, already a well-known businessman, had gathered a group of Icelandic investors, he informed the authorities that his group would include the a foreign investor.

At first, it seemed the French bank Société General would be a co-investor but that changed last minute. Instead of the large French bank came a small German bank no one had heard of, Hauck & Aufhäuser, represented by Peter Gatti, then a managing partner at H&A. But the ink of the purchase agreement had hardly dried when it was rumoured that H&A was only a front for Ólafsson.

Thirteen years later, a report by Reykjavík District judge Kjartan Björgvinsson, published in Iceland this week, confirms the rumours but the deception ran much deeper: through hidden agreements Ólafsson got his share in Búnaðarbanki more or less paid for by Kaupthing. Together with Kaupthing managers, two Société General advisers, an offshore expert in Luxembourg, Gatti and H&A legal adviser Martin Zeil, later a prominent FDP politician in Bayern, Ólafsson spun a web of lies and deceit. A few months after H&A pretended to buy into Búnaðarbanki the hidden agreements made an even greater sense when tiny Kaupthing bought the much larger Búnaðarbanki. Until Kaupthing collapsed in 2008 Ólafsson was Kaupthing’s second largest shareholder and, it can be argued, Kaupthing’s hidden mastermind.

The H&A deceit turned out to be only an exercise for a much more spectacular market manipulation. In the feverish atmosphere of September 2008, Ólafsson, following a similar pattern as in 2003, got a Qatari sheikh to borrow money from Kaupthing and pretend he bought 5.1% in Kaupthing as a proof of Kaupthing’s strength. Ólafsson was charged with market manipulation in 2015 and sentenced to 4 ½ years in prison, together with Kaupthing managers Sigurður Einarsson, Hreiðar Már Sigurðsson and Magnús Guðmundsson, all partners in Ólafsson’s H&A deceit.

Preparing the ‘puffin plot’

Two SocGen bankers, Michael Sautter and Ralf Darpe, worked closely with Ólafsson from autumn 2002 to prepare buying the 45.8% of Búnaðarbanki the Icelandic government intended to sell. Ólafsson gave the impression that SocGen would be the foreign co-investor with his holding company, Egla. Sautter, who had worked on bank privatisation in Israel and Greece, said in an interview with the Icelandic Morgunblaðið in September 2002 that strong core investors were better than a spread ownership, which was being discussed prior to the privatisation. In hindsight it’s easy to guess that the appearances of Ólafsson’s advisers were part of his orchestrated plot.

But something did not work out with SocGen: by mid December 2002 the bank withdrew from the joint venture with Ólafsson who asked for an extended deadline from the authorities to come up with new foreign co-investors. The SocGen bankers now offered to assist in finding a foreign investor and that’s how Ólafsson got introduced to H&A, Peter Gatti and Martin Zeil.

The privately held H&A came into being in 1998 when two private Frankfurt banks merged: 70% was owned by wealthy individuals, the rest held by BayernLB and two insurance companies.

Until last moment Ólafsson withheld who the foreign investor would be but assuring the authorities there would be one. And lo and behold, Peter Gatti showed up at the signing ceremony 16 January 2003, held in the afternoon in an old and elegant building in Reykjavík, formerly a public library. H&A bought the shares in Búnaðarbanki through Egla, Ólafsson’s holding company, which also meant that Ólafsson was in full control of the Búnaðarbanki shares.

At the ceremony in Reykjavík Gatti played the part of an enthusiastic investor, promising to bring contacts and knowledge to the Icelandic banking sector. To the media Ólafsson in his calmly assuring way praised the German bank, which would be valuable to Búnaðarbanki and Icelandic banking. “We chose the German bank,” he stated, “because they were the best for Búnaðarbanki and for our endeavours.”

The particular benefit for Búnaðarbanki never materialised but the arrangement certainly turned out to be extremely lucrative for Ólafsson and others involved. However, it wasn’t the agreement signed in Reykjavík but another one signed some hours earlier, far from Reykjavík, that did the trick.

The hidden agreements at the heart of the ‘puffin plot’

The other agreement, in two parts, signed far away from Reykjavík told a very different story than the show put on at the old library in Reykjavík.

That agreement came into being following hectic preparation by Guðmundur Hjaltason, who worked for Ólafsson, Sautter and Darpe, Gatti and Zeil, an offshore expert in Luxembourg Karim van den Ende and a group of Kaupthing bankers. The Kaupthing bankers were Sigurður Einarsson, Hreiðar Már Sigurðsson, Steingrímur Kárason, Bjarki Diego and Magnús Guðmundsson who have all been convicted of various fraud and sentenced to prison, and two others, Kristín Pétursdóttir, now an investor in Reykjavík and Eggert Hilmarsson, Kaupthing’s trusted lawyer in Luxembourg. Karim Van den Ende is a well known name in Iceland from his part in various dubious Kaupthing deals through his Luxembourg firm, KV Associates.

The drafts had been flying back and forth by email between the members this group. Three days before the signing ceremony Zeil was rather worried, as can be seen from an email published in the new report. One of his questions was:

Will or can Hauck & Aufhäuser be forced by Icelandic law to declare if it acts on its own behalf or as trustee or agent of a third party?

Zeil’s email, where he also asked for an independent legal opinion, caused a flurry of emails between the Kaupthing staff. Bjarki Diego concluded it would on the whole be best that “as few as possible would know about this.”

But how was the H&A investment presented at the H&A? According to Helmut Landwehr, a managing partner and board member at H&A at the time of the scam, who gave a statement to the Icelandic investigators the bank was never an investor in Iceland; H&A only held the shares for a client. Had there been an investment it would have needed to be approved by the H&A board. – This raises the question if Gatti said one thing in Iceland and another to his H&A colleagues, except of course for Zeil who operated with Gatti.

The offshored profits

The hidden agreement rested on offshore companies provided by van den Ende. Kaupthing set up an offshore company, Welling & Partners, that placed $35.5m, H&A’s part in the Búnaðarbanki share purchase, on an account with H&A, which then paid this sum to Icelandic authorities as a payment for its Búnaðarbanki purchase. In other words, H&A didn’t actually itself finance its purchase in the Icelandic bank; it was a front for Ólafsson. H&A was paid €1m for the service.

Then comes the really clever bit: H&A promised it would not sell to anyone but Welling & Partners – and it would sell its share at an agreed time for the same amount it had paid for it, $35.5m. When that time came, in 2005, the H&A share in Búnaðarbanki was worth quite a bit more, $104m to be precise.

Kaupthing then quietly bought the shares so as to release the profit – and here comes another interesting twist: this profit of over $100m went to two offshore companies: $57.5m to Marine Choice, owned by Ólafsson and $46.5m to a company called Dekhill Partners. Kaupthing then invested Ólafsson’s profit in various international companies.

In the new report the investigator points out that the owners of Dekhill Partners are nowhere named but strong indications point to Lýður and Ágúst Guðmundsson, Kaupthing’s largest shareholders who still own businesses in the UK and Iceland.

At some point in the process, which took around two years, the loans to Welling & Partners were not paid directly into Welling but channelled via other offshore companies. This is a common feature in the questionable deals in Icelandic banks, most likely done to hide from auditors and regulators big loans to companies with little or no assets to pledge.

Who profited from the ‘puffin plot’?

Ólafsson is born in 1957, holds a business degree from the University of Iceland and started early in business, first related to state-owned companies, most likely through family relations: his father was close to the Progressive party, the traditional agrarian party, and the coop movement. Ólafsson is known to have close ties to the Progressives and thought to be the party’s major sponsor, though mostly a hidden one.

Ólafsson was also close to Kaupthing from early on and was soon the bank’s second largest shareholder. The largest was Exista, owned by the Guðmundsson brothers.

There are other deals where Ólafsson has operated with foreigners who appeared as independent investors but at a closer scrutiny were only a front for Ólafsson and Kaupthing’s interests. The case that felled Ólafsson was the al Thani case: Mohammed Bin Khalifa al Thani announced in September 2008 a purchase of 5.1% in Kaupthing. The 0.1% over the 5% was important because it meant the purchase had to be flagged, made visible. To the Icelandic media Ólafsson announced the al Thani investment showed the great position and strength of Kaupthing.

In 2012, when the Special Prosecutor charged Sigurður Einarsson, Magnús Guðmundsson, Hreiðar Már Sigurðsson and Ólafsson for their part in the al Thani case it turned out that al Thani’s purchase was financed by Kaupthing and the lending fraudulent. Ólafsson was charged with market manipulation and sentenced in 2015 to 4 ½ years in prison. He had only been in prison for a brief period when laws were miraculously changed, shortening the period white-collar criminals need to spend in prison. Since his movements are restricted it drew some media attention when he crashed his helicopter (he escaped unharmed) shortly after leaving prison but he is electronically tagged and can’t leave the country until the prison sentence has passed.

The Guðmundsson brothers became closely connected to Kaupthing already in the late 1990s while Kaupthing was only a small private bank. Lýður, the younger brother was in 2014 sentenced to eight month in prison, five of which were suspended, for withholding information on trades in Exista, where he and his brother were the largest shareholders.

Both Ólafsson and the Guðmundsson brothers profited handsomely from their Kaupthing connections. Given Ólafsson’s role in the H&A alleged investment and later in the al Thani case it is safe to conclude that Ólafsson was a driving force in Kaupthing and could perhaps be called the bank’s mastermind.

In spite of being hit by Kaupthing’s collapse Ólafsson and the brothers are still fabulously wealthy with trophy assets in various countries. This may come as a surprise but a characteristic of the Icelandic way of banking was that loans to favoured clients had very light covenants and often insufficient pledges meaning the loans couldn’t be recovered, the underlying assets were protected from administrators and the banks would carry the losses. How much this applied to Ólafsson and Guðmundsson is hard to tell but yes, this was how the Icelandic banks treated certain clients like the banks’ largest shareholders and their close collaborators.

When Ólafsson was called to answer questions in the recent H&A investigation he refused to appear. After a legal challenge from the investigators and a Supreme Court ruling Ólafsson was obliged to show up. It turned out he didn’t remember very much.

Ólafsson engages a pr firm to take of his image. After the publication of the new report on the H&A purchase Ólafsson issued a statement. Far from addressing the issues at stake he said neither the state nor Icelanders had lost money on the purchase. Over the last months Ólafsson has waged a campaign against individual judges who dealt with his case, an unpleasant novelty in Iceland.

The Panama Papers added the bits needed to understand the H&A scam

In spite of Gatti’s presence at the signing ceremony in January 2003 the rumours continued, even more so as H&A was never very visible and then sold its share in Búnaðarbanki/Kaupthing. One person, Vilhjálmur Bjarnason, now an Independence party MP, did more than anyone to investigate the H&A purchase and keep the questions alive. Some years later, having scrutinised the H&A annual accounts he pointed out that the bank simply couldn’t have been the owner.

Much due to Bjarnason’s diligence the sale was twice investigated before 2010 by the Icelandic National Audit Office, which didn’t find anything suspicious. The investigation now has thoroughly confirmed Bjarnason’s doubts.

Both in earlier investigations and the recent H&A investigation Icelandic authorities have asked the German supervisors, Bundesanstalt für Finanzdienstleistungsaufschicht, BaFin, for information, a request that has never been granted. During the present investigation the investigators requested information on the H&A ownership in 2003. The BaFin answer was that it could only give that information to its Icelandic opposite number, the Icelandic FME. When FME made the request BaFin refused just the same – a shocking lack of German willingness to assist and hugely upsetting.

The BaFin seems to see its role more as a defender of German banking reputation than facilitating scrutiny of German banks.

The Icelandic Special Investigative Commission, SIC, set up in December 2008 to investigate the banking collapse did investigate the H&A purchase, exposed the role played by the offshore companies but could not identify the owners of the offshore companies involved and thus could not see who really profited.

The Panama leak last year exposed the beneficial owners of the offshore companies. That leak didn’t just oust the then Icelandic prime minister Sigmundur Davíð Gunnlaugsson, incidentally a leader of the Progressive party at the time but also threw up names familiar to those who had looked at the H&A purchase earlier.

Last summer, the Parliament Ombudsman, Tryggvi Gunnarsson who was one of the three members of the SIC made public he had new information regarding the H&A purchase, which should be investigated. The Alþingi then appointed District judge Kjartan Björgvinsson to investigate the matter.

By combining data the SIC had at its disposal and Panama documents the investigators were able to piece together the story above. However, Dekhill Partners was not connected to Mossack Fonseca where the Panama Papers originated, which means that the name of the owners isn’t found black on white. However, circumstantial evidence points at the Gudmundsson brothers.

How relevant is this old saga of privatisation fourteen years ago?

The ‘puffin plot’ saga is still relevant because some of the protagonists are still influential in Iceland and more importantly there is another wave of bank privatisation coming in Iceland. The Icelandic state owns Íslandsbanki, 98.2% in Landsbanki and 13% in Arion.

Four foreign funds and banks – Attestor Capital, Taconic Capital, Och-Ziff and Goldman Sachs – recently bought shares in Arion, in total 29.18% of Arion. Kaupskil, the holding company replacing Kaupthing (holding the rest of Kaupthing assets, owned by Kaupthing creditors) now owns 57.9% in Arion and then there is the 13% owned by the Icelandic state.

The new owners in Arion hold their shares via offshore vehicles and now Icelanders feel they are again being taken for a ride by opaque offshorised companies with unclear ownership. In its latest Statement on Iceland the IMF warned of a weak financial regulators, FME, open to political pressure, particularly worrying with the coming privatisation in mind. The Fund also warned that investors like the new investors in Arion were not the ideal long-term owners.

The palpable fear in Iceland is that these new owners are a new front for Icelandic businessmen like H&A. Although that is, to my mind, a fanciful idea, it shows the level of distrust. Icelanders have however learnt there is a good reason to fear offshorised owners.

The task ahead in re-privatising the Icelandic banks won’t be easy. The H&A saga shows that foreign banks can’t necessarily be trusted to give sound advice. The new owners in Arion are not ideal. The thought of again seeing Icelandic businessmen buying sizeable chunks of the Icelandic banks is unsettling, also with Ólafsson’s scam with H&A in mind.

It’s no less worrying seeing Icelandic pension funds, that traditionally refrain from exerting shareholder power, joining forces with Icelandic businessmen who then fill the void left by the funds to exert power well beyond their own shareholding. Or or… it’s easy to imagine various versions of horror scenarios.

In short, the nightmare scenario would be a new version of the old banking system where owners like Ólafsson and their closest collaborators rose to become not only the largest shareholders but the largest borrowers with access to covenant-light non-recoverable loans. Out of the relatively small ‘puffin plot’ Ólafsson pocketed $57.5m. The numbers rose in the coming years and so did the level of opacity. Ólafsson is still one of the wealthiest Icelanders, owning a shipping company, large property portfolio as well as some of Iceland’s finest horses.

In 2008, five years after the banks were fully privatised the game was up for the Icelandic banks. The country was in a state of turmoil and it ended in tears for so many, for example the thousands of small investors who had put their savings into the shares of the banks; Kaupthing had close to 40.000 shareholders. It all ended in tears… except for the small group of large shareholders and other favoured clients that enjoyed the light-covenant loans, which sustained them, even beyond the demise of the banks that enriched them.

Obs.: the text has been updated with some corrections, i.a. the state share sold in 2003 was 45.8% and not 48.8% as stated earlier.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

IMF (still) worried: political pressure on bank supervisors in Iceland

It beggars belief: over eight years from a calamitous financial crash in Iceland, much to do with failed financial supervision, there is still reason to worry about financial supervision in Iceland. Or rather, there is again reason to worry now that the sheltering capital controls are for all intents and purposes abolished Iceland. All of this, according to the latest IMF Concluding Statement of the 2017 Article IV Mission on Iceland. To Icelog Ashok Vir Bhatia who led the IMF mission says that “worried” wouldn’t be the right word regarding the Icelandic financial supervision but there certainly was cause for concern, as the Statement reflects.

‘The economy of Iceland is doing very well,’ Ashok Vir Bhatia said to Icelog today. With growth of 7% of GDP Iceland is clearly doing well indeed. This rapid growth might be another cause for concern but according to Bhatia the growth seems sustainable.

In short, this is the IMF summary:

Iceland is stepping into a new era of financial openness. It should stride with confidence and care. The top priority must be a decisive strengthening of financial sector oversight. Risks associated with capital flows should be addressed by ensuring that macroeconomic policies, financial sector regulation and supervision, and macroprudential measures act in concert. Current strong growth rates—more than 7 percent last year—are driven by tourism and private consumption, not leverage. Nonetheless, overheating risks are evident. Króna appreciation is a dampening mechanism. Should further króna strength drive inflation prospects lower, there may be room for interest rate cuts. Fiscal policy should be tightened this year in response to demand pressures, but over the medium term there may be room for additional public spending on infrastructure, healthcare, and education.

What the IMF is worried about, is political pressure on Fjármálaeftirlitið, FME, the Icelandic supervisory authority. FME “is not sufficiently insulated from the political process.” The outline of political pressure is there to see. FME needs to go hat in hand to the Parliament every year to beg for a slice of the budget. The present chairman of the board, appointed by prime minister Bjarni Benediktsson during his time in office as a minister of finance, is a young ex-banker; difficult to imagine anyone with her CV in the same position with any regulator in the neighbouring countries.

In Iceland, the IMF Statement will be read with the people at FME in mind, how fit they are at their job. From the point of view of the IMF this criticism is about institutions, not people. If the institutional framework is robust, there is less scope for political pressure. As it is, the institutional frame isn’t as robust as it should be – and that’s what the IMF is emphasising here.

Banks and ownership is one thing to worry about now that things in Iceland will slowly be normalised, post controls. The fear is that the old normal – few big shareholders in each of the three largest banks, not only the largest owners but also the largest borrowers – will be normal again.

The recent purchase of creditors of Arion (via Kaupskil the holding company of Kaupthing) all through totally opaque offshore vehicles, has led to a furious debate in Iceland of fit and proper owners. Here the FME took a rather weak stance as to identifying beneficial owners, after all these new owners have been in Iceland for some years, not exactly new faces.

The new owners are Taconic Capital Advisors, Attestor Capital, Och-Ziff Capital Management Group and Goldman Sachs. Reading between the lines the IMF Statement indicates these are not necessarily ideal bank owners: ‘The recent purchase of the one privately owned pillar bank poses a test for Fjármálaeftirlitid. Financial stability considerations and fairness require that the mandatory fit and proper assessment be thorough, uncompromising, and evenhanded.’

The phenomenal, compared to other European countries, growth of the Icelandic economy is mainly due to tourism and as Bhatia points out to Icelog experience from other countries suggests that tourism doesn’t normally vanish over night. ‘The effect is not just temporary. Tourism is fundamentally good for the economy, a real blessing.’

In Iceland, the attitude towards the booming tourism has been that surely this is like the herring: it comes and goes and while it’s there it should just be exploited. This is answered in the new Statement: ‘Evidence from elsewhere suggests the shoal of tourists is not about to swim away abruptly: tourists are not herring.’ – The Statement emphasises the need for holistic tourism strategy.

A real friend is the one who doesn’t shy away from criticising – this old Icelandic saying comes to mind reading the latest IMF Statement on Iceland.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Will the last bit of capital controls soon be removed?

Now that ordinary Icelanders can invest ISK100m abroad a year and buy one property abroad, life is returning back to normal after capital controls or at least for the 0.01% of Icelanders that will be able to make use of this new normal. This new CBI regime was put in place on the last day of 2016.

For all others, capital controls have for a long time not been anything people sensed in everyday life. The controls really were on capital, in the sense that Icelanders could not invest abroad, but they could buy goods and services, i.e. ordered stuff online and, mostly relevant for companies, paid for foreign services.

The almost only tangible remains of the capital controls regard the four large funds – Eaton Vance, Autonomy, Loomis Sayles and Discovery Capital Management – still locked inside the controls with their offshore króna (by definition króna owned by foreigners, i.e. króna owned by foreigners who potentially want to exchange it to foreign currency).

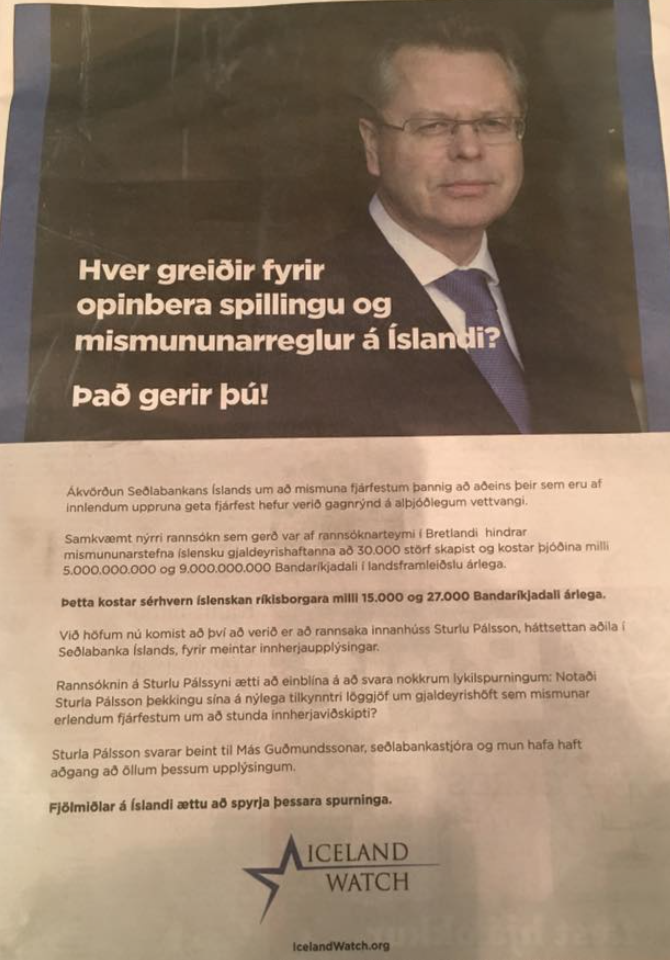

I’ve written extensively on this issue earlier, recently with a focus on the utterly misplaced ads regarding the policy of the Icelandic government (the policy can certainly be disputed but absolutely not in the way the ads chose to portray it; see here and here; more generally here). From over 40% of GDP end of November 2008, when the controls were put in place, the offshore króna amounted to ca. 10% of GDP towards the end of 2016 (see the CBI: Economy of Iceland 2016, p. 75-81.) The latest CBI data is from 13 January this year, showing the amount of offshore króna at ISK191bn, below 10% of GDP.

It now seems there have been high-level talks and as far as I can understand there is great willingness on both sides to find an agreement, which would most likely involve an exit rate somewhat less favourable than the present rate (meaning there would be some haircut for the funds, i.e. some loss) and also that they would exit over some period of time (they have earlier indicated that they are in no hurry to leave).

As before, the greatest risk here is political: will the opposition or parts of it, try to use this case to portray the government as dancing to the tune of greedy foreigners? Icelanders have had a share of the populism so prevalent in other parts of the world but Icelandic politics is by no means engulfed by it.

Arguments in this direction can’t be ruled out but the argument for solving the issue is that Iceland should be moving out of the long shadows of the 2008 collapse, the Central Bank has been buying up foreign currency in order to fetter the ever-stronger króna and this is a problem easier to solve now with the economy booming rather than at some point later in a more uncertain future.

Obs.: on 4 June 2016 the CBI announced a new instrument to “temper and affect the composition of capital inflows.” Some people call this a new form of capital controls. I don’t agree and see these measures, as does the CBI, as a set of prudence rules, announced as a possible course of action already in 2012. Over the last decades other countries have taken a similar course to prevent the inflow of capital that could in theory leave quickly.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

A government born out of discontent and weak majority

It took Bjarni Benediktsson leader of the Independence Party 73 days and three attempts to form a government with two small centre-right parties, Bright Future (Björt Framtíð) and the Reform Party (Viðreisn). The majority is the tiniest possible: one seat. And so is the enthusiasm for the new government, really tiny. New opinion poll shows that 25% is content with the government. The left opposition lost an opportunity to form a government, the voters of the two small coalition parties feel they were cheated into securing an Independence Party rule and the latter party is sour because the government seems weak and Southern Iceland that brought the party most votes got no minister(s). – Thus starts the life of a new government, with irritation and anger. Things can only get better or there will be early elections, again.

In the history of Icelandic politics since the founding of the republic in 1944 political instability hasn’t been dominant. Icelanders got through the 2008 banking collapse but shed the collapse government after a winter of protests, which felt more playful than threatening, hence the cute name of the ‘Pots and pans’ revolution. When the left government, voted to power in the spring of 2009, survived a whole parliament term of four years in spite of fierce infighting it seemed that Iceland was back to stability.

Even more so since the new centre right coalition led by the Progressive Party, with the Independence Party had a safe majority, 38 out of 63 seats. The Panama papers shattered that strength April 3 2016. The day after prime minister Sigmundur Davíð Gunnlaugsson stumbled through the now world famous interview and tried to lie his way out of the revealing questions Bjarni Benediktsson signalled the end of Gunnlaugsson’s government by refusing to back Gunnlaugsson. Two days after the interview Gunnlaugsson resigned, ending the politically weirdest 48 hours Icelanders had ever witnessed.

After a political limbo from spring 2016 to autumn came the October 29 election and 73 days later a new government. None of this signals strength. The new government starts its life with bets against it enduring a full term.

EU: both a raison d’etre and a non-issue

The main reason for former Independence Party voters or right-leaning social democrats to vote for Reform (it seems mainly to have taken voters from the latter, many pro-EU voters had already left the IP in the last two elections) was to secure an action regarding an Icelandic EU membership. Reform was founded by angry IP voters who felt the grand old party had been less than grand in going back on its promise of a referendum.

But this raison d’etre for Reform has now turned into a non-issue, both because many Icelanders want to see how Brexit fares and also because EU is not a pressing issue for booming Iceland.

The Reform party: born out of pro-EU sentiments

The broken promise, which spurned some political enthusiasts into action, was a promise that IP leader Bjarni Benediktsson gave before the 2013 elections. In 2009, the social democrats, buoyed by their election victory and the prime minister post, fulfilled their long-standing promise of applying for EU membership. The Left Greens, their coalition partner, was against membership but the social democrats didn’t take no for an answer.

Up to the 2013 elections IP’s Benediktsson, whose party is split on EU, said holding a referendum asking voters if they wanted to continue membership negotiations was the best way to test voters’ EU sentiments. When in government with the Progressives, who had in principle supported such a vote though the party is fiercely anti-EU, Benediktsson suddenly saw nothing but a ‘political impossibility’ in holding such a vote as both coalition parties were against EU membership.

This caused huge outrage and protests for weeks – there has never been a clear majority in opinion polls to join the EU but this time, there was a huge majority for finalising a membership agreement and then vote on it. This anger spurred pro-EU former Independent party-member Benedikt Jóhannesson to form Reform. The Icelandic name, ‘Viðreisn,’ means ‘Revival’ rather than ‘Reform.’ In Icelandic politics the word refers to a period in Icelandic history, end of the 1950s and 1960s, when IP was in government with the social democrats, seen as a time of prosperity and growth in Iceland.

Now: Icelandic EU membership – let’s forget it

After being so wedded to an EU membership many feel that Jóhannesson and BF’s leader Óttarr Proppé have turned very meek in front of the IP’s EU antipathy. All there is left of a promise of a referendum is this: ‘The government parties agree that if the subject of a referendum on accession negotiations with the European Union is raised in the Althingi, the issue will be put to a vote and finalised towards the end of the electoral period. The government parties may have different opinions on this matter and will respect each other’s views.’

This indicates that well, maybe the matter won’t be raised and then there will be no referendum. However, Reform’s MP Jón Steindór Valdimarsson, a prominent advocate for Icelandic EU membership, has stated that people can rest assured: EU membership will be brought up in the Alþingi. And also, that the parties have agreed to disagree when a referendum will be brought to a vote.

EU membership is not a hot topic in Iceland but the anger still simmers against the last government’s blatant change-of-plan. This means that this very feeble promise on the issue is seen as an abject failure by the two small parties to stick to their EU focus; effectively that the IP bulldozed over them.

‘System change’

One of the most prominent words before the election last October was ‘system change’ – in short, the new parties – i.e. Reform, Bright Future and the Pirates – advocated ‘system change’ whereas the ‘four-party’ as the old parties are called in Icelandic – IP, the Progressives, the social democrats and Left Green – sounded less enthusiastic.

The word mostly referred to fundamental changes in how to allot fishery quotas and farming subsidies, i.e. policies concerning the two old sectors in the Icelandic economy. Two sectors still shaped by the political climate of earlier decades though their part of the economy has dwindled – now, tourism is both the largest sector and the growth sector.

Reform advocated what it called ‘the market approach’ to both these old sectors. Fishing quotas should to a certain degree be auctioned off in order to increase the national profit of fisheries, i.e. levies and taxes, akin how the Faroese have done.

This ambition has been whittled down in the new government’s ‘Platform:’ “The government considers that the benefits of the catch quota system are important for continuing creation of value in the fishing industry. Attention will be given to the benefits of basing the system on long-term agreements rather than allocations without time limits; at the same time, other possible choices will be examined, such as market-linking, a special profit-based fee or other methods to better ensure that payment for access to this common resource will be proportional to the gains derived from it. The long-term security of operations in the sector and economic stability in the rural areas must be ensured.”

Those who advocate changed agricultural policy, away from subsidies to a more consumer-friendly, less protective agriculture, with more import of foreign agricultural produce find this statement very weak: “The allocation of import quotas must be revised and the premise for the dairy industry’s derogations from competition law must be analysed and suitable amendments made.”

The government may surely surprise Icelanders but so far, there is little to indicate that the new parties will be allowed to make a strong departure to the way the IP has run the basic industries for decades.

Feeble vision on tourism

The previous Progressive-led government lost three precious years where the fastest growing most cash-giving industry, tourism, blossomed but without any policy guidelines as to what sort of tourism Iceland wants to pursue. The previous government seemed to be beholden to the interests of certain companies: it couldn’t solve the problem of identifying the most pressing infrastructure projects nor was it able to decide on a levy-structure in tourism. Truly a phenomenal omission.

The new government is worryingly vague on its aims for tourism in Iceland, only two sentences on it in its ‘Platform:’ The importance of tourism as an occupational sector is to be reflected in the administration’s tasks and long-term policy-making. In the years to come, emphasis will be placed on projects that will be conducive to harmonised management of tourism, research and reliable gathering of data, increased profitability of the sector, the spread of tourists to all parts of the country, and rationalised levying of fees, e.g. in the form of parking fees.

Is parking fees the only grand idea of funding? Then that’s worryingly limited and unambitious.

At the same time Iceland is clearly becoming immensely dependent on tourism. With hotels sprouting everywhere there are whispers in the banking sector that further lending to tourism-related projects should be severely conservative.

The truly revolutionary turn: no more polluting heavy industries

Many Icelanders are worried that the aspect of clean and pure nature is hugely compromised by several recent heavy-polluting industries around Iceland in addition to the old ones. Hidden in the three-paragraphs on ‘Environment and Natural Resources’ there is this sentence: ‘There will be no new concessionary investment agreements for the building of polluting heavy industry.’

This may not seem much but in the Icelandic context this is truly revolutionary: a sharp turn from decades of striving to attract heavy polluting industries to Iceland, often with investment agreement granting some form of governmental favours. It can’t be emphasised too much what a turnaround this is – yes, truly revolutionary.

Clear right-leaning policy with a social slant

Although the government advocates responsible housekeeping and financial stability there is also some focus on social matters. Benedikt Jóhannesson has mentioned that Iceland is competing with its Nordic neighbours in holding on to young Icelanders, of getting them to return home from studying abroad or keeping them at home instead of moving abroad.

Jóhannesson has very correctly identified this problem: Icelanders do indeed compare their standard of living to their Nordic neighbours – and Iceland falls short in many aspects.

One policy advocated by the new government is to adapt Icelandic study loans to the system in the other Nordic countries: ‘A scholarship system based on the Nordic model will be adopted and lending from the Student Loan Fund will be based on full cost of living support and incentives for academic progress. Consideration will be given to the social role of the Fund. – This seems a more costly option then the present student loan system and the extra funds needed haven’t been specified as far as I know.

Immigrants are less skilled than Icelanders who emigrate

One potential danger is the above: the mismatch in outflow and inflow of people. The booming tourism needs a lot of low-skilled work, now largely provided by foreign workers whereas educated or highly skilled Icelanders have been tempted to emigrate or don’t return after studying abroad but choose to find work after finishing their studies.

In the 2015 OECD Economic Survey of Iceland this problem is spelled out: ‘The current boom is based to some extent on the rapid development of the tourism sector. With one million visitors in 2014, this is welcome, but it tends to create relatively low-skilled low-wage jobs and comes with limited opportunities for productivity growth. Against the draw of migrants to the booming low-skill jobs, the Icelandic economy is experiencing outmigration of high-skilled people. Furthermore, unemployment amongst university graduates is rising, suggesting mismatch. As such, and despite the economic recovery, Iceland remains in transition away from a largely resource-dependent development model, but a new growth model that also draws on the strong human capital stock in Iceland has yet to emerge.’

This wasn’t at all welcome news in Iceland and it was clear that some politicians are in denial about this mismatch. Icelanders, especially politicians, like to portray Iceland as a country with highly skilled workforce. At a closer look, comparing higher education in Iceland to the neighbouring countries, this isn’t really true. And the above paragraph proved an unpalatable course (as I sensed when reporting for Rúv I brought this up: there was some attempt from political quarters to rubbish the OECD data.)

Therefore it’s particularly refreshing to hear Jóhannesson mention this fact – that Iceland is indeed in many ways struggling to maintain skilled people and people with higher education. Whether something sensible comes out of it remains to be seen but acknowledging the problem is a promising first step.

Will the government last the full parliamentary term?

It’s too early to tell, so far so eventless. Or well, not quite. As a minister of finance Bjarni Benediktsson reacted to the Panama leak – which cost Sigmundur Davíð Gunnlaugsson both his prime minister post and leadership of his party, the Progressives and showed that also Benediktsson had offshore connections – by setting up a taskforce in mid June to estimate Icelandic assets offshore and the loss to the Treasury caused by the Icelandic offshorisation.

The taskforce handed in its report on September 13 and gave a presentation to Benediktsson on October 5. On October 10 Benediktsson said in Alþingi the report would be published in the next few days but nothing happened. It wasn’t until January 6 that the report was unceremoniously published on the ministry’s website and sent to the Alþingi economy and trade committee – after some journalists and politicians had said they would demand access by using the Icelandic Freedom of Information act.

When questioned Benediktsson brusquely denied there had been any cover-up, the report had simply come too late to be discussed in the outgoing parliament. A day later, Benediktsson was forced to retract his words and apologise: there had indeed be enough time to present it before the elections. Notably, elections called because of offshorisation. – Benediktson, now prime minister, has recently refused to discuss the report with the Alþingi economy and trade committee but says he will discuss its finding when the report will be debated in Alþingi.

This wasn’t a glorious end to Benediktsson’s time as minister of finance and the beginning of his reign as prime ministers. His opponents talk of his attempted cover-up, others that this is his typical lack of attention to details, a certain carelessness and sloppiness.

Governing in good times – not as easy as it seems

Politicians in power in times of crisis and hardship may at times dream of the sweetness of power in good times. In Icelandic we say that it takes strong bones to survive prosperity. That’s exactly the challenges facing Iceland for the time being.

The GDP growth last year was around 4%, unemployment is 4%, building cranes crowed the Reykjavík city scape, the Central Bank is facing losses because of the foreign currency it’s hording to keep the króna, now record strong, from being even stronger – all of this both signs of prosperity and challenges. Right now, fishermen have been striking since mid December, no end in sight. They are both demanding substantial wage increases, which the fishing industries refuse to meet and that the government reinstalls earlier tax deductions, flatly denied by minister of finance Jóhannesson.

In spite of good times in Iceland there is a permanent political chill over the island for the time being. It remains to be seen if the new government finds the way to melt the chill without ending up with an overheated and out-of-control economy – a far too familiar phenomenon in the prone-to-bumpy-ride Icelandic economy.

There are eleven ministers and eight ministries in the new Icelandic government – from the Independence Party (6): party leader and prime minister Bjarni Benediktsson, Kristján Þór Júlíusson minister of Education, Science and Culture, Þórdís Kolbrún Reykfjörð Gylfadóttir minister of Tourism, Industries and Innovation (Ministry of Industries and Innovation), Guðlaugur Þór Þórðarson minister of foreign affairs, Sigríður Ásthildur Andersen minister of Justice (Ministry of the Interior), Jón Gunnarsson minister of Transport and Local Government (Ministry of the Interior); Reform Party (3): party leader and minister of Finance Benedikt Jóhannsson, Þorsteinn Víglundsson minister of Social Affairs and Gender Equality (Ministry of Welfare), Þorgerður Katrín Gunnarsdóttir minister of Fisheries and Agriculture (Ministry of Industries and Innovation); Bright Future (2): party leader Óttarr Proppé minister of Health (Ministry of Welfare), Björt Ólafsdóttir minister for the Environment and Natural Resources. – Only ministries with two ministers are mentioned above. The government has announced that it plans to split the Ministry of the Interior into Ministry of Justice and Ministry of Transport and Local Government, which means there will soon be nine ministries. – I have earlier used the name “Revival” for Viðreisn without noticing that on its English website “The Reform Party” is the name used.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Iceland: back to its old conservative roots?

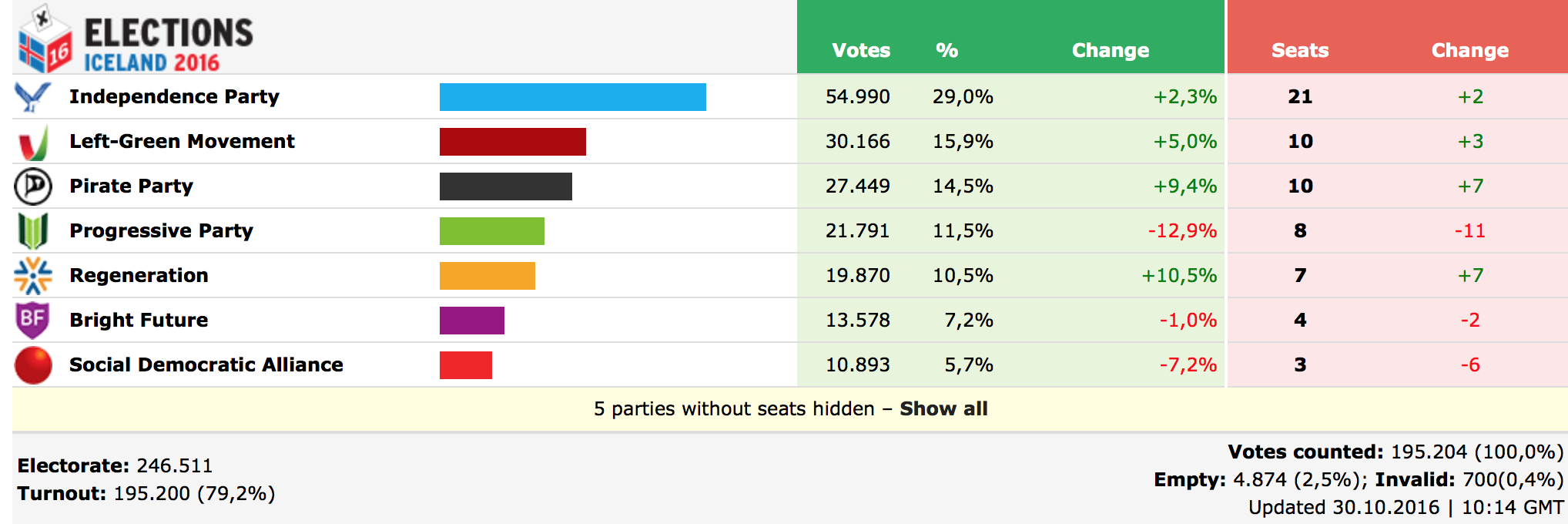

“Epic success! There are a lot of coalition possibilities” tweeted elated newly elected Pirate MP Smári McCarthy the morning after polling day. Quite true, the Pirates did well, though less well than opinion polls had indicated. Two of the four old parties, the Left Greens and the Independence Party could also claim success. The other two oldies, the Progressives and the Social Democrats, suffered losses. Quite true, with Bright Future and the new-comer Viðreisn, Revival, in total seven instead of earlier six parties, there are plenty of theoretical coalition possibilities. But so far, the party leaders have been eliminating them one by one leaving decidedly few tangible ones. Unless the new forces manage to gain seats in a coalition government Iceland might be heading towards a conservative future in line with its political history.

In spite of the unruly Pirates and other new parties the elections October 29 went against the myth of Iceland abroad as a country rebelling against old powers – the myth of a country that lost most of its financial system in a few days in October 2008 instead of a bailout, then set about to crowd-write a new constitution, investigate its banks and bankers and jailing some of them and is now, somehow as a result of all of this, doing extremely well.