Search Results

Offshore onshore and Luxembourg, the black heart of Europe

“Corruption and the role of tax havens” was the headline of the annual workshop of the Tax Justice Network – and the word Luxembourg was heard quite often there.

There were plenty of interesting talks, much to learn. Two things are still playing around in my head: an exchange on the offshore bubble inside, not outside, of our Western countries – and the destructive role of Luxembourg when it comes to both taxation and finance.

Offshore is actually onshore

I was on a panel today about “Stories of secrecy;” I gave a talk about “Iceland, the offshorisation of an economy” and Richard Smith from Naked Capitalism talked about the role of Scottish LPs in the Moldova bank robbery where $800 were syphoned off, into offshore companies. Nicholas Shaxson, author of “Treasure Islands,” was the moderator.

Shaxson mentioned the increasing focus on financial stability and the offshore universe, something that is very clear when it comes to Iceland and events in autumn 2008 – the offshorisation did not alone cause the banking collapse but it played its role in hiding money, connections, ownership, debt and everything else that can be hidden offshore.

One image I have been toying with lately, in order to explain the dangerous effect of offshorisation, is that each Western country is like a balloon where law and order, civil society seems to permeate the whole balloon. However, at a closer look, the offshore is like a bubble inside the balloon, where civil society is kept out, where bankers, accountants and other facilitators, together with companies and wealthy individuals act as if the rules of society, the social pact, didn’t exist; i.a. have created this safe haven from law and order.

What we should really be focusing on is that offshore isn’t outside of our countries, it is right within, creating a space immune to all the things the social pact otherwise touches, the social pact of taxation, rule of law etc. And it hugely undermines financial stability… as we saw in 2008, not only in Iceland.

Luxembourg: at the heart of dirty deals and tax destruction

Omri Marian is an assistant professor of law at the Irvine School of Law, University of California. He has studied 172 of the tax contracts the Lux Leaks brought into the open. His very illuminating point is that at first glance the Luxembourg tax laws looks just as sophisticated as tax laws normally do in Western countries. However, there is simply no execution of this convincingly looking legal tax code.

It sounds insane but one person, a certain Marius Kohl, was in charge of agreeing to all the privately negotiated “advance tax agreement,” effectively the tax for individual companies. The agreements, normally running to hundreds of pages, would often be signed off by the very hard-working Kohl on the day of application.

This reminded my of my experience with the Luxembourg financial regulator, Commission de Surveillance du Secteur Financier, CSSF. After the collapse of the Icelandic banks in October 2008 it slowly dawned on me that most of the banks’ dirty deals, especially in Kaupthing and Landsbanki, had been run through their Luxembourg operations.

Yet, when I asked lawyers and accountants I was told that all was in good order in Luxembourg, they had strict laws regarding the financial sector; the CSSF was there to keep an eye on things.

Listening to Marian it dawned on me that yes, this is how Luxembourg does it: it pays lip service to European rules and regulation and what you normally expect from a Western democracy by having a legal code on tax and the finance sector. But that’s all: the laws exist but only on paper – there is no execution to speak of.

Some years ago I visited the CSSF, got an audience with some six or seven people there. A very memorable meeting; we sat at the largest meeting table I have ever sat at; I on one side, the CSSF-ers on the other side. I told them what was slowly coming to light in Iceland: the alleged fraud and shenanigans, the loans with light covenants and little or no collaterals and guarantees, alleged market manipulations via the banks’ proprietary trading and share parking in companies the banks finances etc. – so, weren’t they going to look into the banks’ operations. There were darting eyes and down-cast faces: no, no need to do anything, all in good order in Luxembourg. D’accord…

I intend to write further on the thoughts above – but suffice it to say that if the European Union is at all serious about acting on the offshorisation of the European economies it has to make sure that Luxembourg not only adorns itself with all the correct-looking legal codes but actually enforces it, i.a. by having the staff needed to do so.

*Nicholas Shaxson blogged today on the Tax Justice Network on these aspects of Luxembourg and quoted some of my earlier blogs on Luxembourg, i.a. my observations that Luxembourg attract financial companies because they know full well that Luxembourg is a safe haven… from regulatory scrutiny.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Jim Ratcliffe and his feudal hold of Icelandic salmon rivers and farming communities

The largest landowner in Iceland owns around 1% of Iceland, mostly land adjacent to salmon rivers in the North East of Iceland – and he is not Icelandic but one of the wealthiest Brits, James or Jim Ratcliffe, a Sir since last year, of Ineos fame. His secretive acquisitions of farms with angling rights have been facilitated by the Icelandic businessmen who for years have been investing in salmon rivers through offshore companies. Opaque ownership is nothing new. Though the novelty is the grip on these rivers now held by a foreigner, with no ties to the community and assets valued at just above the Icelandic GDP, the central problem is mainly the nationality of the owner, but the concentration of ownership.

“If you are doing honest business, I assume you would feel better if you could talk freely about it. This secrecy breeds suspicion,” says Ævar Rafn Marinósson, a farmer at Tungusel in North East Iceland. The secretive business he is talking about is the business of buying farms adjacent to salmon rivers in his part of Iceland.

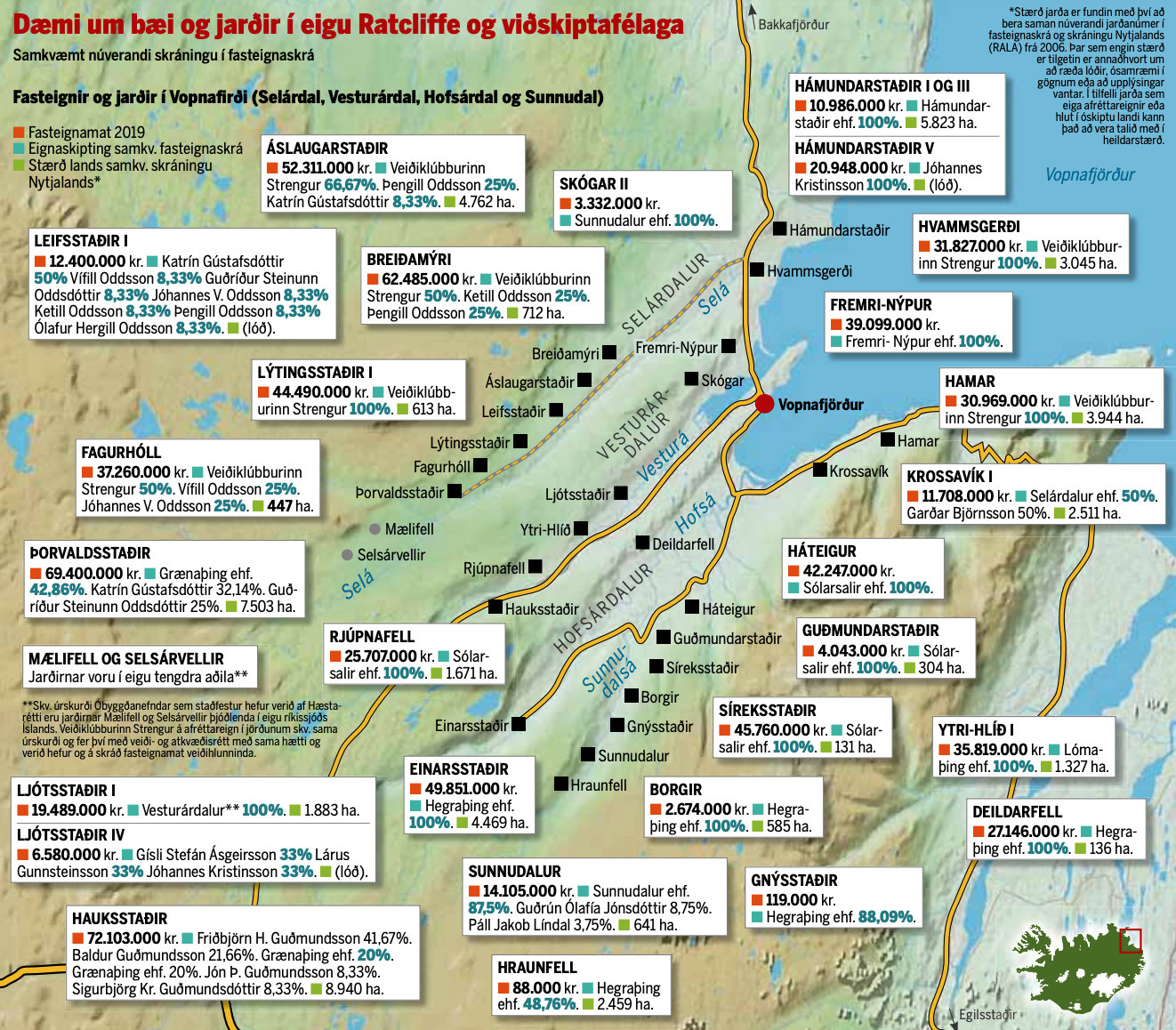

The secrecy is not new: for more than a decade, the ownership of the attractive salmon rivers in Iceland has been hidden in an opaque web of on- and offshore companies. That opacity might now hit the community when rivers and land is increasingly being held by one man, Jim Ratcliffe, whose assets are estimated £18.15bn. Through direct and indirect ownership, Ratcliffe owns over forty Icelandic farms concentrated in and around Vopnafjörður, which gives him the control of angling rights in some of the best salmon rivers in Iceland.

The petrochemical giant Ineos is Ratcliffe’s source of wealth. Interestingly, his salmon investments are part of his recent, rapidly growing investment in sport, from cycling, sailing and football to his, so far, tentative interest in British Premier League football clubs with price tags of billions. Ratcliffe claims that his petrochemical industries are run in an environmentally friendly way and strongly denies that his sport investments are any form of green-washing.

The secrecy surrounding Ratcliffe’s Icelandic investments, so out of proportions in this rural community of salmon and sheep farmers, has bred both rumours and suspicion that splits apart families, neighbours and the local communities as they debate whether the funds on offer are a substitute for losing control of the angling and the land.

Also, because Ratcliffe is a distant owner. He leaves it to his Icelandic representatives to talk to the farmers some of whom, like Marinósson, refuse to sell and as a consequence feel harassed. And then there are the pertinent questions of how Ratcliffe’s funds flow into the local economy, as one farmer opposed to Ratcliffe’s growing hold of the region, mentioned in an interview in the Icelandic media.

Following Ratcliffe’s purchases, foreign ownership of land is now a hot topic in Iceland. The government is looking at legal restrictions to limit foreign ownership. A new poll shows that 83.6% of Icelanders support this step. – But that might be a mistaken angle: the problem is not foreign ownership but concentrated ownership.

“I’m not upset with Ratcliffe, he’s just a businessman pursuing his interests. I’m upset with the government of Iceland that is letting this happen,” says Marinósson. He is not the only one to point out that a new legislation might come too late for the salmon rivers in the North East.

Angling – strictly regulated

Though far from being a mass industry, angling has long been both a beloved sport in Iceland and attracted wealthy foreigners. In the early and mid 20th century, English aristocrats came to fish in Iceland. In the 1970s and 1980s, the Prince of Wales was fishing in Hofsá, now controlled by Ratcliffe. With the changing pattern of wealth came high-flyers from the international business world.

As angling interest grew, net fishing for salmon was restricted so as to let the angling flourish. In 2011, 90% of the salmon caught in Iceland was from angling. The annual average salmon catch is around 36.000 salmon, with the figures jumping over 80.000 in the best years. There are in total 62 salmon rivers with 354 rods allowed; the rivers in the North East are thirty, with 124 rods (2011 brochure in English; Directorate of Fisheries).

According to the Salmon and Trout Act from 2006, the fishing rights are privately owned by those who own the land adjacent to rivers and lakes. The fishing rights come with a string of obligations, supervised by the Directorate of Fisheries and most importantly: the fishing rights cannot be split from the land – the only way to control the angling is to own a farm or farms holding the angling right.

The owners of the farms owning a river or lake are obliged to set up a fishing association to manage the angling; both the necessary investment and the profit has to be shared according to the amount of land owned. The ownership is split according to voting rights and percentage owned.

Wielding control over the angling, these associations can decide either to manage the angling themselves or lease out the rights to angling clubs or other consortia.

From overfishing to highly regulated angling regime

Already in the 1970s, the fishing associations run by the farmers owning the best salmon rivers were increasingly leasing out the angling rights to groups of wealthy Icelandic anglers, mostly business men from Reykjavík.

In some rare cases, foreign anglers who frequented Iceland, held the angling rights through a lease. One attractive salmon river in the North East, Hafralónsá, where Ævar Rafn Marinósson and his family are among the owners, was leased by a Swiss angler from 1983 to 1994; from 1995 to 2003, a British and a French angler leased the river.

During the 1990s, the popularity of angling led to overfishing in many salmon rivers with tension between biology and the financial profits from the angling rights. But the owners of the angling rights quickly came to understand that overfishing would kill the goose laying the golden eggs, or rather the salmon that brought wealth to the community.

The angling is now restricted in many ways: each river has only a certain number of rods; the angling time is restricted to certain hours of the day and a certain amount of annual angling days, often 90 days, from mid-June.

In addition, some form of “fish and release” is in place in most if not all the highly sought after and expensive salmon rivers. All these protective measures have been driven by those who control the angling, i.e. the fishing associations owned by the landowners.

Foreign anglers mainly pursue the sporty fly-fishing, whereas Icelanders tend not to frown upon using spoons and worms. Icelandic anglers know it is good to fish with spoons and worms after the foreign fly-anglers have been “beating the river” as we say in Icelandic. That normally ensures great catch, a trick the Icelandic anglers are happy to use.

Angling – from farmers to wealthy business men

The leases related to the salmon rivers normally run for some years. The fees to the fishing associations are a significant part of income for the farmers. The lessees are normally obliged to undertake investment in the infrastructure around the river.

Part of cultivating the salmon population in the rivers is expanding the habitat. This is for example done by building “salmon-ladders,” enabling the salmon to migrate beyond waterfalls or other hindrances, potentially increasing the rods allowed in each river and thus making the river more profitable.

Those who rent the rivers try to sell each rod at as high a price as the market can tolerate. Angling in the best rivers in Iceland is an expensive sport, also because the fishing is sold as a package with accommodation and meals included.

No longer primitive huts, the best fishing lodges are like boutique hotels, where the best chefs in Iceland come and cook for discerning anglers with the wines to match. Part of the summer news in the Icelandic media is reporting on the number of salmon caught in the well-known rivers, size and weight, what tools were used and sometimes also who is angling where.

This is the angling of the very wealthy. But angling is also popular with thousands of ordinary Icelanders. Angling for salmon, trout and sea trout in less famous rivers and lakes, is an affordable and ubiquitous sport in Iceland.

The opaque ownership web that Ratcliffe is buying into

Incidentally, this development of buying farms, not just licensing the angling rights, has been going on in Iceland for decades. In the early 1970s, a medical doctor and keen angler in Reykjavík, Oddur Ólafsson, bought five farms along Selá. Decades and several owners later these farms are now owned by Ratcliffe.

Orri Vigfússon (1942-2017) was a businessman and passionate angler, who in 1990 set up the North Atlantic Salmon Fund as an international initiative in order to protect and support the wild North Atlantic salmon. Vigfússon was influential in Icelandic angling circles and well known in angling circles all around the North Atlantic. He was also primus motor in Strengur, a company that for decades has controlled the best rivers in the North East, now controlled by Ratcliffe.

The web of on- and offshore companies related to angling has been in the making in Iceland since the late 1990s, when the general offshorisation of wealthy Icelanders boomed through the foreign operations of the Icelandic banks. A key person in this web is an Icelandic businessman.

Born in 1949, Jóhannes Kristinsson has been living in Luxembourg for years. Media-shy in Iceland he was in business with flashy businessmen like the duo Pálmi Haraldsson and Jón Ásgeir Jóhannesson of Baugur fame, synonymous with the Icelandic boom before the 2008. Kristinsson seems to be linked to around 25 Icelandic companies.

By 2006, it was attracting media attention in Iceland that wealthy anglers were no longer just licencing the angling rights but were outright buying farms holding angling rights. One name figured more often than others, Jóhannes Kristinsson. In an interview at the time, Kristinsson said he probably owned only one farm outright but was mostly a co-owner with others, without wanting to divulge how much he owned.

The farmers felt they knew Kristinsson, a frequent guest in the North East and the opaque ownership did not seem much of an issue. However, the effect of the opacity is now becoming very clear as Kristinsson is selling to a foreigner with no ties to the community, leaving the community potentially little or no control over some of its glorious rivers and land.

Luxembourg, Ginns and Reid

Kristinsson’s ownership of lands and rivers in the North East seems to have been held in Luxembourg from early on. Dylan Holding is a Luxembourg company, registered in 2000, by BVI companies, which Kaupthing owned and used to offshorise its clients. No beneficial owner is named in any of the publicly available Dylan Holding documents but the company was set up with Icelandic króna, indicating its Icelandic ownership.

According to Dylan Holding’s 2018 annual accounts, the company, still filing accounts in Icelandic króna, held assets worth ISK2.6bn. Its 2017 accounts list eleven Icelandic holding companies, fully or majority-owned by Dylan Holding, among them Grænaþing. Last year, Ratcliffe bought Grænaþing, as part of the deal with Kristinsson; an indication of Kristinsson being the beneficial owner of Dylan Holding.

The names of two of Ratcliffe’s trusted Ineos lieutenant, Jonathan F Ginns and William Reid, are closely linked to Ratcliffe’s Icelandic ventures as to so many other Ratcliffe ventures. According to UK Companies House, Ginns sits or has been on the board of over seventy Ineos/Ratcliffe related companies, Reid on seven.

Ginns and Reid sit on the boards of three Icelandic companies previously owned by Dylan Holding indicating that these companies are now under Ratcliffe’s control. Whether Ratcliffe has bought Dylan Holding outright or where exactly his ownership stands at, remains to be seen but it seems safe to conclude that Ratcliffe now owns significantly more land on his own rather than, as earlier, through joint venture with Kristinsson and others. Kristinsson seems to be withdrawing, leaving Ratcliffe as the sole owner.

Ratcliffe’s rapid rise to being Iceland’s largest landowner

Jim Ratcliffe, the angler with the funds to indulge his salmon passion was nr.3 on the Sunday Times Rich List this year, with assets valued at £18.15bn, down from £20.05bn in 2018, when he ranked nr.1. A Brexiteer who is not waiting for Brexit to happen: after relocating to the UK from Switzerland, where Ratcliffe and Ineos were domiciled from 2010 until some months after the EU referendum in 2016, Ratcliffe moved to Monaco last year. Tax and regulation seem to be his main concerns.

Ratcliffe had been fishing in Vopnafjörður for some years without attracting any attention. It was not until late 2016, when he visibly started buying into the Icelandic angling consortia, that his name first appeared in the Icelandic media. By then, he already owned eleven farms in the area, both through sole ownership and through his share in Strengur. Local sources believe Ratcliffe started investing earlier in angling assets, hidden in opaque ownership structures.

In December 2016 it was announced that Ratcliffe had bought the major part of the single largest farmland in Iceland, Grímsstaðir. This mostly barren wasteland of glorious beauty in the highlands beyond Mývatn had been owned by Grímstaðir farmers and their families for generations. The Icelandic state was a minority owner and has retained its share of the land. Ratcliffe stated at the time he was buying Grímsstaðir because it was part of the Selá water system; buying the land was part of his plan to support and protect the wild salmon.

The Grímsstaðir deal drew a lot of media attention in Iceland because in 2011, a Chinese businessman and poet, Huang Nubo, had tried to purchase this land with unclear intentions. Nubo had some Icelandic friends from his university years but practically no assets abroad except some real estate in the US, which he seemed to struggle to maintain. In 2014, the Icelandic government vetoed Nubo’s plans: he was not European, and his plans lacked clarity.

For decades, Strengur, under changing ownership, has managed the angling rights in Selá and Hofsá, two of the best salmon rivers in the North East and bought up farms adjacent to the rivers. In 2012, a new 960sq.m fishing lodge opened by Selá, a good example of the investment done in order to improve the angling experience and cater to wealthy anglers.

Following a 2018 transaction Ratcliffe owns almost 87% of Strengur, a jump from the 34% he had owned earlier, meaning that he controls the angling rights in both Selá and Hofsá. Ratcliffe bought the 52.75% by purchasing a company owned by Jóhannes Kristinsson. Strengur’s director Gísli Ásgeirsson (who features in this Ineos PR video) is now seen as Ratcliffe’s mouthpiece. He has ties to around twenty Icelandc companies, many of which are linked to Kristinsson.

The Ratcliffe Kristinsson consortium now owns 40 to 50 farms. But Ratcliffe is looking for more: earlier this year, Ratcliffe added one farm to his Icelandic portfolio. He now seems trying to secure ownership of yet another river, Hafralónsá.

The Icelandic media had reported that he had now secured majority in the angling association of that river but that does not seem to be the case. Ævar Rafn Marinósson is one of the owners of Hafralónssá. He says to Icelog that as far as he knows, Ratcliffe is still a minority owner.

The suspicion among those who are not in Ratcliffe’s fold is rife as a change in ownership might bring about drastic changes. With majority hold, Ratcliffe might for example drive the farmers in minority to bankruptcy by forcing through investments in the Hafralónsá angling association, which would wipe out the profits that make an important part of the farmers’ annual income.

Ratcliffe’s representative made Marinósson an offer to buy his farm. His answer was that the farm, which he owns with his parents, was not for sale. The representative then visited his elderly parents with the same offer, although it had been made clear to him that the farm was not for sale.

Misinformed passion

In a PR video from Ineos, Jim Ratcliffe talks of “overfishing and ignorance” that threat the salmon populations in Iceland. In the video Ratcliffe’s passion for salmon fishing is given as his drive for investing “heavily in the region to help expand the salmon’s natural breeding grounds” through constructing of salmon ladders in six rivers. The latter part of the video is about his investment in safari parks in Africa, with both initiatives presented as rising from Ratcliffe’s environmental concerns.

As mentioned earlier, the times of overfishing in Icelandic salmon rivers are long over. To portray Ratcliffe as a saviour of the salmon rivers in the North East is at best misinformed, at worst profoundly patronising to the farmers who have lived and bred salmon all their live and whose livelihoods have partly depended on the silvery fish. But the fact that Ratcliffe has the funds to follow his passion cannot be disputed.

In August this year Ineos Technology Director Peter S. Williams signed an agreement on behalf of Ratcliffe with the Marine and Fresh Water Institute in Iceland, where Ratcliffe takes on to fund salmon research to the amount of ISK80m, around £525.000. At the time it was announced that any profit from Strengur will be ploughed into maintaining and supporting the salmon populations in the rivers that Strengur controls. Strengur’s director Gísli Ásgeirsson said at the time that the aim was sustainability in cooperation with the farmers and local councils. There will be those in the local community who feel that cooperation is exactly what is lacking.

In a Rúv tv interview I did with Ratcliffe in 2017 (unfortunately no longer available online), Ratcliffe said he was driven by his passion for angling and the uniqueness of the unspoiled nature in Iceland, a value in itself. There is some speculation in Iceland that Ratcliffe’s angling investments might be driven by something else then his passion for angling.

Some think water as commodity in a world facing water shortage is his real interest, which would explain his emphasis on buying the rivers outright instead of joint venture or just renting the angling rights. Others, that plans by Bremenport to build a port in nearby Finnafjörður in order to service the coming Transpolar Sea Route might be in Ineos’ interest. Again, total speculation but heard in Iceland. – Ineos is investing in facilities in Willhelmshaven, where Bremenport is building a new container terminal.

Mushrooming sport investment: from millions in salmon and safari to, possibly, billions in Premier League football

Ratcliffe’s UK holding company for his Icelandic assets is Halicilla Ltd, incorporated in 2015, its business being “mixed farming.” Halicilla’s 2017 accounts list two Icelandic companies as assets, Fálkaþing, incorporated in 2013 and Grenisalir, incorporated in 2016, “Icelandic companies, which in turn hold land and fishing rights.”

Ratcliffe has been unwilling to divulge how much he has invested in Iceland but that can be gleaned with some certainty from the Halicilla accounts: its assets amounted to £9.7m in 2016, which with further acquisitions in 2017, had grown to £15.3m by the end of 2017, financed directly by the shareholder, i.e. Ratcliffe.

In addition to investments in Icelandic salmon rivers, Ratcliffe’s sports investments have mushroomed in the recent years. In December 2017, he announced his investment in luxury eco-tourism project in safari parks in Tanzania through a UK company, Falkar Ltd, incorporated in 2015. As Halicilla, Falkar is financed by Ratcliffe, with a loan of £6.3m, at the end of 2017. With his interest in sailing, Ratcliffe owns two yachts, one of them, Hampshire II a superyacht worth $150m, with two of his Ineos partners owning three yacths. In addition, Ratcliffe owns four jets, three Gulfstream jets and one Dassault Falcon.

Ratcliffe’s other sport investments involve much higher figures than his investments in salmon and safari. Last year, he invested £110m in Britain’s America’s Cup team. His investment in March in the cycling Team Sky, now Team Ineos, seemed to imply that the Team’s earlier budget of £34m would increase significantly. In 2017 he bought the Lausanne-Sport football club, where his brother is now the club’s president, and has recently completed a £88.7m deal to buy Ligue 1 club Nice.

The figures might rise: last year, Ratcliffe led an unsuccessful bid of £2bn for Chelsea FC and has aired his interest to buy his favourite team, Manchester United – one day, some super-star footballers might be practicing fly-fishing under Ratcliffe’s instructions in Vopnafjörður.

Split families and farming communities, threats and bullying

The farmers in the North East face a dilemma. It is in the interest of farmers to be able to sell their farm for a reasonable price if they intend to retire or give up farming for other reasons. However, seeing whole fjords and entire rivers now owned not by a consortium of wealthy anglers in Reykjavík but by a single foreigner, wholly unrelated to the country and the North East, with a strangle hold on the community, has spread unease.

When the Icelandic consortia started buying farms in order to gain control of the angling, the farmers often continued to live on the farm, as tenants. On the whole, the farms have continued to be farmed, though there are exceptions.

Ratcliffe has stated he is keen for the farmers to keep living on the farms and has offered them to stay as tenants. With money in the bank the tenants can profit from the land as earlier but no longer benefit from the angling rights as earlier or have any say on the use of the river.

Ratcliffe’s acquisitions have completely changed the game around the rivers. The novelty is his immense buying power. His entrance into the angling circles has split families and communities. To sell or not to sell is a burning question for many since Ratcliffe’s representatives keep making lucrative offers to the few farmers who have so far been unwilling to sell.

This is, as such, not entirely Ratcliffe’s fault – he simply has an exorbitant amount of money to indulge in one of his hobbies though he has shown little interest in learning from the farmers who know the rivers like the back of their hands. But this sowing of anger and unease has been the side effect of his investments. Perhaps also to some degree because of the people he has chosen to work with in Iceland; how well informed Ratcliffe is of the circumstances surrounding his investments is unclear.

Ratcliffe flies in and out of Iceland. The Icelanders who work for him are there and some live in the communities Ratcliffe has already bought or is trying to buy. His salmon shopping spree may be backed by the best intensions, but the side effect is effectively making him the ruler of a few hundred Icelanders who live off the land they love dearly. The land, which Ratcliffe visits at his leisure, once in a while.

Restrictions on ownership of land may come too late for the North East

Foreign ownership is a hot topic in Iceland for the time being, given the quick and enormous concentration of Ratcliffe’s ownership in the North East. But it would be wrong to focus on foreign ownership – the real problem is concentrated ownership.

Ratcliffe is not the only foreign landowner in Iceland. There are a few others but there is increased interest from abroad for land in Iceland. One foreign owner closed off his land with signs of “Private road,” much to the irritation of his Icelandic neighbours since free passage in the country side is seen as a general right in Iceland. One practical reason is the gathering of sheep: sheep roam freely in summer and farmers need to roam just as freely when the sheep is gathered in autumn.

Though rapidly developing, luxury tourism is still a rarity in Iceland, and has so far not led to land being closed off. As Ratcliffe’s Tanzania investment shows, he is interested in luxury tourism. Seeing angling turning into an even more rarefied luxury than it already is, marketed mainly for people in Ratcliffe’s wealth bracket, is not an enticing thought for most Icelanders.

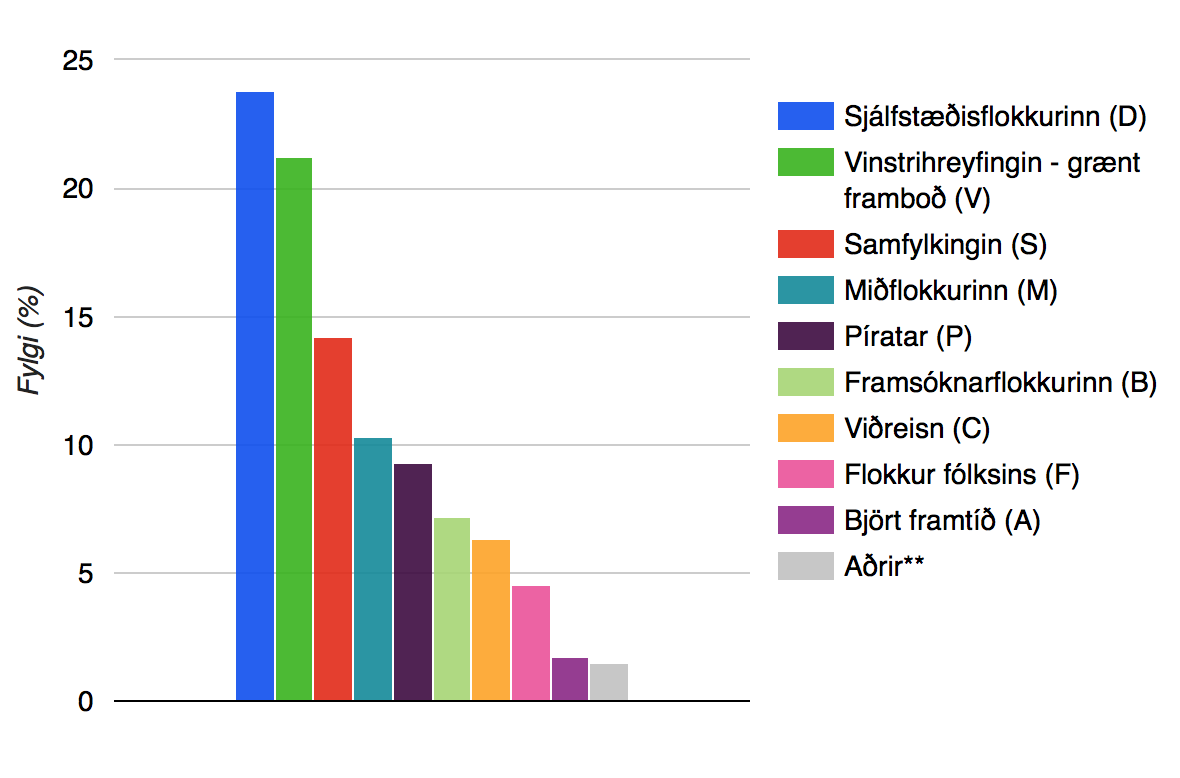

The government led by Katrín Jakobsdóttir, leader of the Left Green party (Vinstri Grænir), with the Independence party (Sjálfstæðisflokkur) and the Progressives (Framsóknarflokkur), is now under pressure to consider means to limit foreign ownership. A working group has been gathering material and new law is promised this coming winter. One step in the right direction of focusing on concentrated ownership, not just foreign ownership, would be to reintroduce pre-emptive purchase rights of local councils, abolished in 2004.

Finding the proper criteria that drive rural development in the right direction will not be easy. But Icelanders are certainly waiting for that to happen – having stratospherically wealthy people, Icelandic or foreign, owning entire rivers and fjords on a scale not seen since the time of the feudal lords of the Icelandic sagas is not seen as positive rural development. When law is finally passed, it might be too late to prevent that to happen in the North East.

*This image is from a July 21 July 2018 article on Ratcliffe’s acquisitions in the Icelandic daily Morgunblaðið and shows ownerships of farms in Vopnafjörður (there are other farms in the neighbouring communities.)

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Landsbanki Luxembourg equity release loans – again in Paris Court

In August 2017, French prosecutors lost their criminal case against ex Landsbanki chairman of the board Björgólfur Guðmundsson* and eight former employees of Landsbanki Luxembourg. These nine were charged in relation to the bank’s equity release loans. The prosecution won an appeal and the case is now in court again at Palais de Justice, expected to run into June.

Over the last few decades, equity release loans have wrecked havoc for borrowers in many countries. Like FX loans (see Icelog here), they have been a wandering financial curse. When circumstances change, bankers claim they could not have known – a hollow claim given the history of these loans.

The Landsbanki equity release lending saga has now been running for over a decade, closely followed on Icelog for the last few years (an overview here; link to earlier coverage here). This is a saga in three chapters:

1 The Landsbanki Luxembourg lending – how the loans were sold (an interesting aspect, given that banks all over Europe have lost FX lending cases due to EU consumer directives); the (unrealistically high?) evaluation of the properties used as collaterals; was there ever a viable plan in place in the bank to properly invest that part of the loan that was suppose to pay for the payout part; how credible and trustworthy was the bank’s information to customers? Given that Landsbanki was in dire straits when it started selling these loans it is also of interest what the bank’s purpose was with the loans: just another financial product or a product to save the bank? – This chapter is part of the criminal case in Paris.

2 The administration of Landsbanki Luxembourg has raised many and serious questions that Luxembourg authorities have so far been utterly unwilling to consider. The administrator, Yvette Hamilius, accuses the borrowers of simply trying to avoid paying. In 2012, the Luxembourg prosecutor Robert Biever issued a statement in her favour, without ever having investigated the case; an interesting if scary example of how the justice operates in the Duchy that depends on banking for its good life. – However, as earlier recounted on Icelog, the borrowers have a very different story to tell, of misleading and conflicting information on their loans and then an unwillingness on behalf of the administrator to engage with them and answer their questions. – Interestingly, Landsbanki Luxembourg has recently been losing in civil cases in Spain where equity release borrowers have brought the estate to court, mainly on the ground of consumer protection (see ERVA for various moves in Spain).

3 The sole creditor to Landsbanki Luxembourg is LBI., the estate of the failed Landsbanki Iceland. LBI has no direct control over Landsbanki Luxembourg but as seen from its webpage, it follows the case closely. The assets in Luxembourg are now the only assets left for LBI to distribute to its creditors. The question is if the administrator’s hard line against the borrowers, with the accruing legal cost and the clock ticking in eternity, really is in the interest of Landsbanki Luxembourg’s sole creditor.

This time there is a formidable presence on the borrowers’ legal team. Originally Norwegian, Eva Joly studied law in France. She was appointed an investigative judge in the early 1990s, famous for taking on the great and the not so good in major corruption case, where dozens of people, who never expected to see the inside of a prison cell, ended up just there. Joly, an MEP since 2006, cooperates with her daughter, Caroline, also a lawyer.

It remains to be seen how things progress this time in the Paris court room at the grandiose Palais de Justice.

*Together with his son Thor Björgólfsson, Björgólfur Guðmundsson was the largest shareholder of Landsbanki; father and son owned just over 40% of the bank but in reality, controlled over 50% of the bank since ca. 10% of the bank’s shares were in several offshore companies, controlled by the bank itself. This is one the many things exposed by the 2010 report by the Icelandic Special Investigative Commission. Guðmundsson was declared bankrupt following the banking collapse, his son is still one of the wealthiest people on this planet.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

The unsolved case of Landsbanki in dirty-deals Luxembourg / 10 years on

The Icelandic SIC report and court cases in Iceland have made it abundantly clear that most of the questionable, and in some cases criminal, deals in the Icelandic banks were executed in their Luxembourg subsidiaries. All this is well known to authorities in Luxembourg who have kindly assisted Icelandic counterparts in obtaining evidence. One story, the Landsbanki Luxembourg equity release loans, still raises many questions, which Luxemburg authorities do their best to ignore in spite of a promised investigation in 2013. Some of these questions relate to the activities of the bank’s liquidator, ranging from consumer protection, the bank’s investment in the bank’s own bonds on behalf of clients and if the bank set up offshore companies for clients without their consent.

The Landsbanki Luxembourg equity release loans were issued to clients in France and Spain. Indeed, all these loans were issued to clients outside of Luxembourg. One intriguing fact emerged during the French trial in Paris last year against Landsbanki Luxembourg and nine of its executives and advisors: the French clients got the bank’s loan documents in English, the non-French clients got theirs in French.*

Landsbanki Iceland went into administration October 7 2008. The next day, Landsbanki Luxembourg was placed into moratorium; liquidation proceedings started 12 December. Over the years, Icelog has raised various issues regarding the Landsbanki Luxembourg equity release loans, mostly sold to elderly people (see here). These issues firstly relate to how the bank handled these loans, both the marketing and the investments involved and secondly, how the liquidator Yvette Hamilius, has handled the Landsbanki Luxembourg estate and the many complaints raised by the equity release clients.

A liquidator is an independent agent with great authority to investigate. There is abundant material in Iceland, both from the 2010 Report of the Special Investigative Commission, SIC and Icelandic court cases where almost thirty bankers and others close to the banks have been sentenced to prison. These cases have invariably shown that the most dubious deals were done in the banks’ Luxembourg operations.

Already by June 2015, liquidators of the estates of the three large Icelandic banks were ending their work, handing remaining assets over to creditors. In the, in comparison, tiny estate of Landsbanki Luxembourg there is no end in sight due to various legal proceedings. Yet, its arguably largest problem, the so-called Avens bond, was solved already in 2011. At the time, Már Guðmundsson governor of the Icelandic Central Bank paid tribute to the help received from amongst others Hamiliusfor “considerable efforts in leading this issue to a successful conclusion.”

The Landsbanki Luxembourg equity release clients have another story to tell, both in terms of their contacts with the liquidator and Luxembourg authorities. In May 2012, these clients, who to begin with had each and everyone been struggling individually, had formed an action group and aired their complaints in a press release, questioning Luxembourg’s moral standing and Hamilius’ procedures.

The following day, the group got an unexpected answer: Luxembourg State Prosecutor Robert Biever issued a press release. As I mentioned at the time, it was jaw-droppingly remarkable that a State Prosecutor saw it as his remit to address a press release directed at the liquidator of a private company in a case the Prosecutor had not investigated. According to Biever, Hamilius had offered the borrowers “an extremely favourable settlement” but “a small number of borrowers,” unwilling to pay, was behind the action.

In 2013 Luxembourg Justice Minister promised an investigation into the Landsbanki products that was already taking “great strides.” So far, no news.

The Landsbanki Luxembourg equity release scheme: high risk, rambling investments

In theory, the magic of equity release loans is that by investing around 75% of the loan the dividend will pay off the loan in due course. I have seen calculations of some of the Landsbanki equity release loans that make it doubtful that even with decent investments, the needed level of dividend could have been reached – the cost was simply too high.

If something seems too good to be true it generally is. However, this offer came not from a dingy backstreet firm but from a bank regulated and supervised in Luxembourg, a country proud to be the financial centre of Europe. And Landsbanki was not the only bank offering these loans, which interestingly have long ago been banned or greatly limited in other countries. In the UK, equity release loans wrecked havoc and created misery some decades ago, leading to a ban on putting up the borrower’s home as collateral.

Having scrutinised the investments made for some of the Landsbanki Luxembourg clients the first striking thing is an absolutely staggering foreign currency risk, also related to the Icelandic króna. Underlying bonds on the foreign entities such as Rabobank and European Investment Bank were nominated in Icelandic króna (see here on Rabobank ISK bond issue Jan. 2008), in addition to the bonds of Kaupthing and Landsbanki, the largest and second largest Icelandic banks at the time.

Currencies were bought and sold, again a strategy that will have generated fees for the bank but was of dubious use to the clients.

The second thing to notice is the rudderless investment strategy. To begin with the money was in term deposits, i.e. held for a fixed amount of time, which would generate slightly higher interest rates than non-term deposits. Then shares and bonds were bought but there was no apparent strategy except buying and selling, again generating fees for the bank.

The equity release clients were normally not keen on risk but the investments were partially high risk. The 2007 and 2008 losses on some accounts I have looked have ranged from 10% to 12%. These were certainly testing years in terms of investment but amid apparently confused investing there was indeed one clear pattern.

One clear investment pattern: investing in Landsbanki and Kaupthing bonds

Having analysed statements of four clients there is a recurring pattern, also confirmed by other clients and a source with close knowledge of the bank’s investments: in 2008 (and earlier) Landsbanki Luxembourg invariably bought Landsbanki bonds as an investment for clients, thus turning the bank’s lending into its own finance vehicle. In addition, it also bought Kaupthing bonds. The 2010 SIC report cites examples of how the banks cooperated to mitigate risk for each other.

It is not just in hindsight that buying Landsbanki and Kaupthing bonds as equity release investment was a doomed strategy. Both banks had sky-high risk as shown by their credit default swap, CDS. The CDS are sort of thermometer for banks indicating their health, i.e. how the market estimates their default risk.

The CDS spread for both banks had for years been well below 100 points but started to rise ominously in 2007 as the risk of their default was perceived to rise. At the beginning of 2008, the CDS spread for Landsbanki was around 150 points and 300 points for Kaupthing. By summer, Kaupthing’s CDS spread was at staggering 1000 points, then falling to 800 points. Landsbanki topped close to 700 points. The unsustainably high CDS spread for these two banks indicated that the market had little faith in their survival. With these spreads, the banks had little chance of seeking funds from institutional investors (SIC Report, p.19-20).

The red lights were blinking and yet, Landsbanki Luxembourg staff kept on steadily buying Landsbanki and Kaupthing bonds on behalf of clients who were clearly risk-averse investors.

Equity release investment in some details

To give an idea of the investments Landsbanki Luxembourg made for equity release borrowers, here is some examples of investment (not a complete overview) for one client, Client A:

Loan of €2.1m in January 2008; the loan was split in two, each half converted into Swiss francs and Japanese yens. The first investment, €1.4m, two thirds of the loan,was in LLIF Balanced Fund (in Landsbanki Luxembourg loan documents the term used is Landsbanki Invest. Balanced Fund 1 Cap but in later overviews from the liquidator it is called LLIF Balanced Fund, a fund named in Landsbanki’s Financial Statements 2007 as one of the bank’s investment funds).

Already in February 2008 Landsbanki Luxembourg bought Kaupthing bond for this client for €96.000. End of April 2008 €155.000 was invested in Landsbanki bond, days before €796.000 of the LLIF Balanced Fund investment was sold. Late May and end of August Landsbanki bonds were bought, in both cases for around €99.000. In early September 2008 Landsbanki invested $185.000 in Kaupthing bonds for this client. The next day, the bank sold €520.000 in LLIF Balanced Fund.

Landsbanki’s investments were focused on the financial sector that in 2008 was showing disastrous results. For client A the bank bought bonds in Nykredit, Rabobank, IBRD and EIB, apparently all denominated in Icelandic króna. In addition, there were shares in Hennes & Maurits, and a Swedish company selling food supplement.

A similar pattern can be seen for the other clients: funds were to begin with consistently invested in LLIF Balanced Fund but later sold in favour of Kaupthing and Landsbanki bonds. Although investment funds set up by the Icelandic banks were later shown to contain shares in many of the ill-fated holding companies owned by the banks’ largest shareholders – also the banks’ largest borrowers – a balanced fund should have been seen as a safer investment than bonds of banks with sky-high CDS spreads.

MiFID and the Landsbanki Luxembourg equity release loans

Landsbanki certainly did not invent equity release loans. These loans have been around for decades. Much like foreign currency, FX, loans, a topic extensively covered by Icelog, they have brought misery to many families, in this case mostly elderly people. FX lending has greatly diminished in Europe, also because banks have been losing in court against FX borrowers for breaking laws on consumer protection.

There might actually be a case for considering the equity release loans as FX loans since the loans, taken in euros, were on a regular basis converted into other currencies, as mentioned above. – This is, so far, an unexplored angle of these cases that Luxembourg authorities have refused to consider.

Another legal aspect is that the first investments were normally done before the loans had been registered with a notary, as is legally required in France.

The European MiFID, Markets in Financial Instruments Directive was implemented in Luxembourg and elsewhere in the EU in 2007. The purpose was to increase investor protection and competition in financial markets.

Consequently, Landsbanki Luxembourg was, as other banks in the EU, operating under these rules in 2007. It is safe to say, that the bank was far below the standard expected by the MiFID in informing its clients on the risk of equity release loans.

The following paragraph was attached to Landsbanki Luxembourg statements: “In the event of discrepancies or queries, please contact us within 30 days as stipulated in our “General Terms and Conditions.”– However, the bank almost routinely sent notices of trades after the thirty days had passed.

It is unclear if the liquidator has paid any attention to these issues but from the communication Hamilius has had with the equity release clients there is nothing to indicate that she has investigated Landsbanki operations compliance with the MiFID. MiFID compliance is even more important given that courts have been turning against equity release lenders in Spain due to lack of consumer protection – and that banks have been losing in courts all over Europe in FX lending cases.

Clients offshorised without their knowledge

The “Panama Papers” revealed that Landsbanki was one of the largest clients of law firm Mossack Fonseca; it was Landsbanki’s go-to firm for setting up offshore companies. Kaupthing, no less diligent in offshoring clients, had its own offshore providers so the leak revealed little regarding Kaupthing’s offshore operations. The prime minister of Iceland Sigmundur Davíð Gunnlaugsson, who together with his wife owned a Mossack Fonseca offshore company, became the main story of the leak and resigned less than 48 hours after the international exposure.

In September 2008, a Landsbanki Luxembourg client got an email from the bank with documents related to setting up a Panama company, X. The client was asked to fill in the documents, one of them Power of Attorney for the bank and return them to the bank. The client had never asked for this service and neither signed nor sent anything back.

In May 2009, this client got a letter from Hamilius, informing him that the agreement with company X was being terminated since Landsbanki was in liquidation. The client was asked to sign a waiver and a transfer of funds. Attached was an invoice from Mossack Fonseca of $830 for the client to pay. When the client contacted the liquidator’s office in Luxembourg he was told he should not be in possession of these documents and they should either be returned or destroyed. Needless to say, the client kept the documents.

Company X is in the Offshoreleak database, shown as being owned by Landsbanki and four unnamed holders of bearer shares. – Widely used in offshore companies, bearer shares are a common way of hiding beneficial ownership. Though not a proof of money laundering, the Financial Action Task Force, FATF, considers bearer shares to be one of the characteristics of money laundering.

This shows that Landbanki Luxembourg set up a Panama company in the name of this client although the client did not sign any of the necessary documents needed to set it up. Also, that the liquidator’s office knew of this. (This account is based on the September 2009 email from Landsbanki Luxembourg to the client and a statement from the client).

Other clients I have heard from were offered offshore companies but refused. The story of company X only came out because of the information mistakenly sent from the liquidator to the client.

Landsbanki Luxembourg clients now wonder if companies were indeed set up in their names, if their funds were sent there and if so, what became of these funds. This has led them to attempt legal action in Luxembourg against the liquidator. Only the liquidator will know if it was a common practice in Landsbank Luxembourg to set up offshore companies without clients’ consent, if money were moved there and if so, what happened to these funds.

The curious role of a certain Philomène Ruberto

Invariably, the equity release loans in France and Spain were not sold directly by Landsbanki Luxembourg but through agents. This is another parallel to FX lending characterised by this pattern. According to the Austrian Central Bank this practice increases the FX borrowing risk as agents are paid for each loan and have no incentive to inform the client properly of the risks involved.

One of the agents operating in France was a French lady, Philomène Ruberto. In 2011, well after the collapse of Landsbanki, the Landsbanki Luxembourg was putting great pressure on the equity release borrowers to repay the loans. At this time, Ruberto contacted some of the clients in France. Claiming she was herself a victim of the bank, she offered to help the clients repay their loans by brokering a loan through her own offshore company linked to a Swiss bank, Falcon Private Bank, now one of several banks caught up in the Malaysian 1MDB fraud.

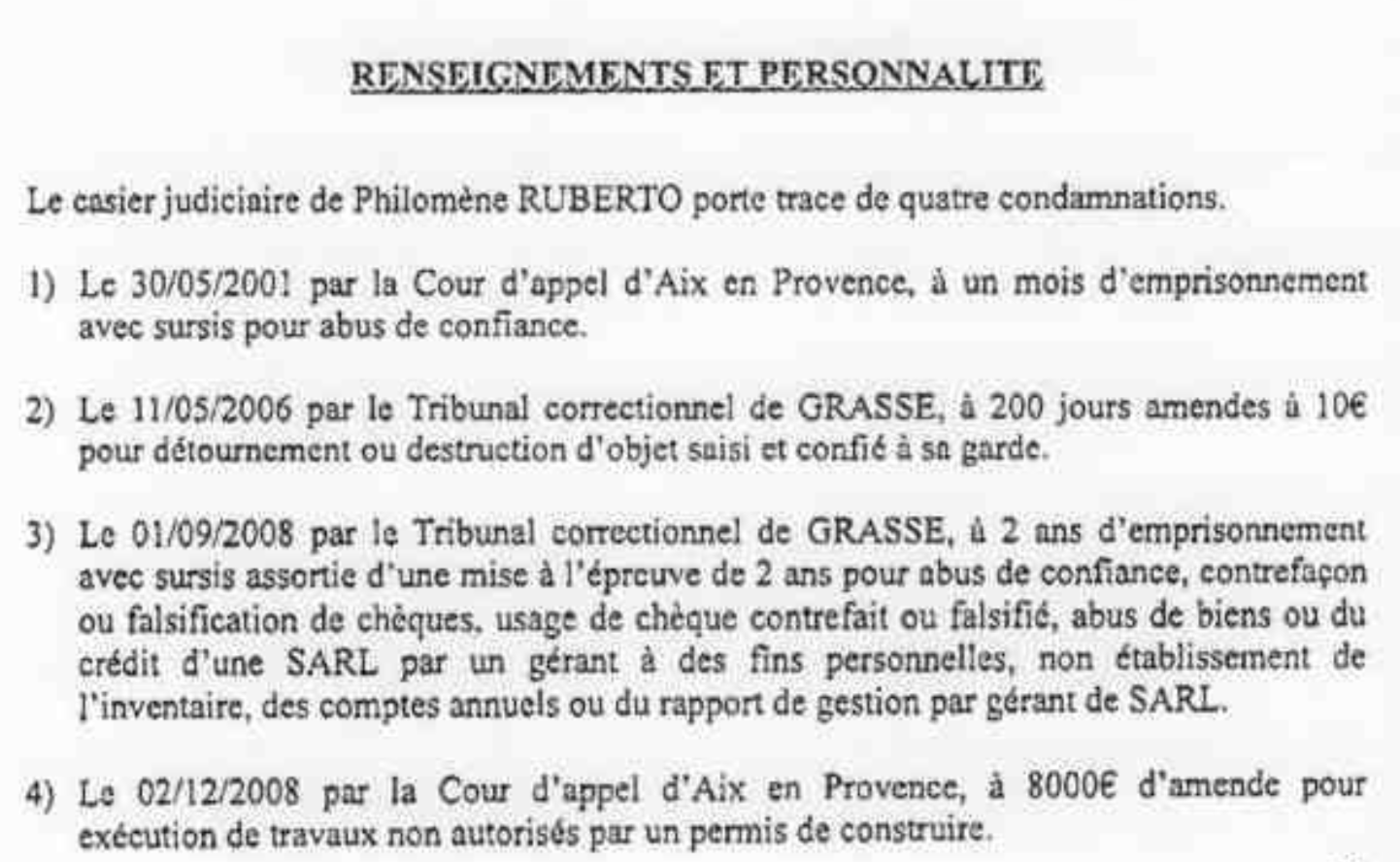

Some clients accepted the offer but that whole operation ended in court, where the clients accused Ruberto of fraud and breach of trust. In a civil case judgement at the Cour d’appel d’Aix en Provence in spring 2013, the judge listed a series of Ruberto’s earlier offenses, committed before and during the time she acted as an agent for Landsbanki:

This case was sent on a prosecutor. In a penal case in autumn 2014 Ruberto was sentenced by Tribunal Correctionnel de Grasse to 36 months imprisonment, a fine of €15,000 in addition to the around €190,000 she was ordered to pay the civil parties. According to the 2104 judgement Ruberto was, at the time of that case, detained for other causes, indicating that she has been a serial financial fraud offender since 2001.

But Ruberto’s relationship with Landsbanki Luxembourg prior to the bank’s collapse has a further intriguing dimension: GD Invest, a company owned by Ruberto and frequently figuring in documents related to her services, was indeed also one of Landsbanki Luxembourg largest borrowers. The SIC Report (p.196) lists Ruberto’s company, GD Invest, as one of the bank’s 20 largest borrowers, with a loan of €5,4m.

In 2007, at the time Ruberto was acting as an agent in France for Landsbanki Luxembourg, she not only borrowed considerably funds but, allegedly, on very favourable terms. In March 2007, GD Invest borrowed €2,7m and then further €2.3m in August 2007, in total almost €5,1m. Allegedly, Ruberto invested €3m in properties pledged to Landsbanki but the remaining €2m were a private loan. It is not clear what or if there was a collateral for that part.

By the end of 2011, Ruberto’s debt to Landsbanki Luxembourg was in total allegedly €7,5m. In January 2012 it is alleged that the Landsbanki Luxembourg liquidator made her an offer of repaying €2,4m of the total debt, around 1/3 of the total debt. Ruberto’s track record of fraudulent behaviour from 2001, raises questions to her ties first to Landsbanki and then to Landsbanki Luxembourg liquidator. (The overview of Ruberto’s role is based on emails and court documents provided by Landsbanki Luxembourg equity release borrowers.)

Inconsistent information from the Landsbanki Luxembourg liquidator

From 2012, when I first heard from Landsbanki Luxembourg equity release borrowers, inconsistent information from the liquidator has been a consistent complaint. The liquidator had then been, and still is, demanding repayment of sums the clients do not recognise. There are also examples of the liquidator coming up with different figures not only explained by interest rates. The borrowers have been unwilling to pay because there are too many inconsistencies and too many questions unanswered.

As mentioned above, Landsbanki Luxembourg was put in suspension of payment, in October 2008 and then into administration in December 2008. As far as is known, people who later took over the liquidation were called on to work at the bank during this time. During this time, many clients were informed that their properties had fallen in value, meaning that the collateral for their loan, the property, was inadequate. Consequently, they should come up with funds. At this time, there was no rational for a drop in property value. This is one of the issues the borrowers have, so far unsuccessfully, tried to raise with the liquidator.

Other complaints relate to how much had been drawn. One example is a client who had, by October 2008, in total drawn €200,000. This is the sum this client want to repay. Mid October 2008, after Landsbanki Luxembourg had failed, this client got a letter from a Landsbanki employee stating that close to €550,000, that the client had earlier wanted transferred to a French account, was still “safe” on the Landsbanki account. This amount was never transferred but the liquidator later claimed it had been invested and demanded that the client repay it.

The liquidator has taken an adversarial stance towards these clients. The clients complain of lack of transparency, inconsistent information, lack of information and lack of will to meet with them to explain controversies.

The role and duty of a liquidator

By late 2009 the liquidator had sold off the investments. This is what liquidators often do: after all, their role is to liquidate assets and pay creditors. However, a liquidator also has the duty to scrutinise activity. That is for example what liquidators of the banks in Iceland have done. A liquidator is not defending the failed company but the interests of creditors, in this case the sole creditor, LBI ehf.

Incidentally, the liquidator has not only been adversarial to the clients of Landsbanki but also to staff. In 2011 the European Court of Justice ruled against the liquidator in reference for a preliminary ruling from the Luxembourg Cour du cassation brought by five employees related to termination of contract.

Liquidators have great investigative powers. In addition to documents, they can also call in former staff as witnesses to clarify certain acts and deeds. If this had been done systematically the things outlined above would be easy to ascertain such as: is it proper in Luxembourg that a bank systematically invests clients’ funds in the bank’s own bonds? Was the investment strategy sound – or was there even a strategy? Were clients’ funds systematically moved offshore without their knowledge? If so, was that done only to generate fees for the bank or were there some ulterior motives? And have these funds been accounted for? A liquidator can take into account the circumstances of the lending and settle with clients accordingly.

And how about informing the State Prosecutor of Landsbanki’s investments on behalf of clients in Landsbanki bonds and the offshoring of clients without their knowledge?

But having liquidators in Luxembourg asking probing questions and conducting investigations is possibly not cherished by Luxembourg regulators and prosecutors, given that the country’s phenomenal wealth is partly based on exactly the kind of dirty deals seen in the Icelandic banks in Luxembourg.

LBI ehf – the only creditor to Landsbanki Luxembourg

Landsbanki Luxembourg has only one creditor – the LBI ehf, the estate of the old Landsbanki Iceland. According to the LBI 2017 Financial Statements the expected recovery of the Landsbanki Luxembourg amounts to €84,3m, compared to €74,3m estimated last year. The increase is following what LBI sees as a “favourable ruling by the Criminal Court in Paris on 28 August 2017,” i.e. that all those charged were acquitted.

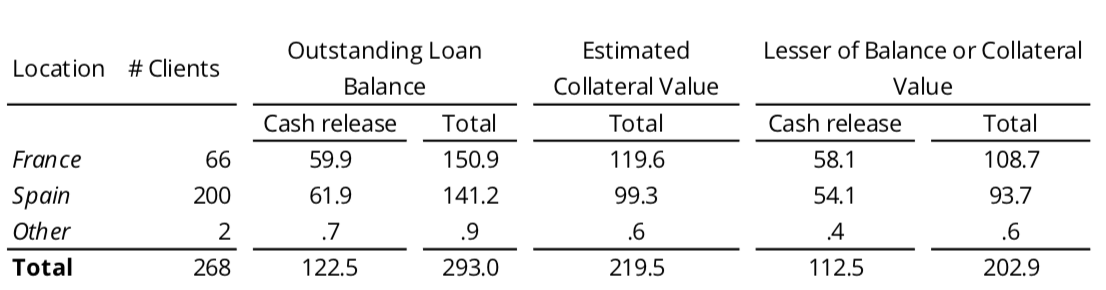

The only assets in Landsbanki Luxembourg are the equity release loans. The breakdown of the loans, in EUR millions, in the LBI 2017 Statements is the following:

Further to this the Statements explain that “LBI’s claims against the Landsbanki Luxembourg estate amounted to EUR 348.1 million, whereas the aggregate balance of outstanding equity release loans amounted to EUR 293.0 million with an estimated recoverable value … of EUR 84.3 million.”

As pointed out, the information “regarding legal matters pertaining to the Landsbanki Luxembourg estate is mainly based on communications from that estate‘s liquidator, and not all of such information has been independently verified by LBI management.”

Apart from the criminal action in Paris and the appeal of the August 2017 judgment, the Financial Statements mention other legal proceedings: “Landsbanki Luxembourg is also subject to criminal complaints and civil proceedings in Spain. … In November 2012, several customers in France and Spain brought a criminal complaint in Luxembourg against the liquidator, alleging that the former activities of Landsbanki Luxembourg are criminal and thus that the estate’s liquidator should be convicted for money laundering by trying to execute the mortgages. Other criminal complaints have been filed in Luxembourg in 2016 and 2017 based on the same grounds against the liquidator personally.”

This all means that “LBI’s presented estimated recovery numbers are subject to great uncertainty, both in timing and amount.”

What is Luxembourg doing?

It is not the first time I ask this question here on Icelog. In July 2013 there was the news from Luxembourg, according to the Luxembourg paper Wort, that there were two investigations on-going in Luxembourg related to Landsbanki. This surfaced in the Luxembourg parliament as the Justice Minister Octavie Modert responded to a parliamentary question from Serge Wilmes, from the centre right CSV, Luxembourg’s largest party since founded in 1944.

According to Modert both cases related to alleged criminal conduct in the Icelandic banks. One investigation was into financial products sold by Landsbanki. “…the deciding judge is making great strides,” she said, adding that in order not to jeopardize the investigation, the State Attorney was unable to provide further details on the results already achieved.”

Sadly, nothing further has been heard of this investigation.

In spring 2016 the Luxembourg financial regulator, Commission de surveillance du secteur financier, CSSF had set up a new office to protect the interests of depositors and investors. This might have been good news, given the tortuous path of the Landsbanki Luxembourg clients to having their case heard in Luxembourg – CSSF has so far been utterly unwilling to consider their case.

The person chosen to be in charge is Karin Guillaume, the magistrate who ruled on the Landsbanki Luxembourg liquidation in December 2008. As pointed out in PaperJam, Guillaume has been under a barrage of criticism from the Landsbanki clients due to her handling of their case, which somewhat undermines the no doubt good intentions of the CSSF. From the perspective of the Landsbanki Luxembourg clients, CSSF has chosen a person with a proven track record of ignoring the interests of depositors and investors.

So far, Luxembourg authorities have resolutely avoided investigating Landsbanki and the other Icelandic banks. In Iceland almost 30 bankers, also from Landsbanki, and others close to the banks have been sentenced to prison, up to six years in some cases (changes to Icelandic law on imprisonment some years ago mean that those sentenced serve less than half of that time in prison before moving to half-way house and then home; they are however electronically tagged and can’t leave the country until the time of the sentence is over).

In the CSSF 2012 Annual Report its Director General Jean Guill wrote:

During the year under review, the CSSF focused heavily on the importance of the professionalism, integrity and transparency of the financial players. It urged banks and investment firms to sign the ICMA Charter of Quality on the private portfolio management, so that clients of these institutions as well as their managers and employees realise that a Luxembourg financial professional cannot participate in doubtful matters, on behalf of its clients.

Almost ten years after the collapse of Landsbanki, equity release clients of Landsbanki Luxembourg are still waiting for the promised investigation, wondering why the liquidator is so keen to soldier on for a bank that certainly did participate in doubtful matters.

*In court, the French singer Enrico Macias mentioned that all his documents were in English. I found this strange since I had seen documents in French from other clients and knew there was a French documentation available. When I asked Landsbanki Luxembourg clients this pattern emerged. All the clients asked for contracts in their own language. When the non-French clients asked for contracts in English they were told the documentation had to be in French as the contracts were operated in France. Conversely, the French were told that the language was English as it was an English scheme. I have now seen this consistent pattern on documents for the various clients. – Here is a link to all Icelog blogs, going back to 2012, related to the equity release loans. Here is a link to the Landsbanki Luxembourg victims’ website.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Lessons from Iceland: the SIC report and its long lasting effect / 10 years after

The Bill passed by the Icelandic parliament in December 2008 on setting up an independent investigative commission, the Special Investigative Commission did not catch much attention at the time. The goal was nothing less than finding out the truth in order to establish events leading up to the 2008 banking collapse, analyse causes and drawing some lessons. The SIC report was an exemplary work and immensely important at the time to establish a narrative of the crisis. But in hindsight, there is yet another lesson to be learnt: its importance does not diminish with time as it helps to counteract special interests seeking to rewrite history.

There were no big headlines when on 12 December 2008 Alþingi, the Icelandic parliament, passed a Bill to set up an investigative commission “to investigate and analyse the processes leading to the collapse of the three main banks in Iceland,”which had shaken the island two months earlier. The palpable lack of enthusiasm and attention was understandable: the nation was still stunned and there was no tradition in Iceland for such commissions. No one knew what to expect, the safest bet was to not expect very much.

That all changed when the Commission presented its results in April 2010. Not only was the report long – 2600 pages in print in addition to online-only material – but it did actually tell the real story behind the collapse: the immensely rapid growth of the banks, from one GDP in 2002 to ten times the GDP in 2008, the stronghold the largest shareholders, incidentally also the largest borrowers, had on the banks’ managements, the political apathy and lax regulation by weak regulators, stemming from awe of the financial sector.

Unfortunately, the SIC report was not translated in full into English; see executive summary and some excerpts here.

With time, the report’s importance has not diminished: at the time, it clarified what had happened thus preventing those involved or others with special interest, to reshape the past according to their own interests. With time, hindering the reshaping of the past has become of major importance, also in order to draw the right lessons from the calamitous events in October 2008.

What was the SIC?

According to the December 2008 SIC Act (in Icelandic), the goal was setting up an investigative commission, that would, at the behest of Alþingi, seek “the truth about the run-up to and the causes of the collapse of the Icelandic banks in 2008 and related events. [The SIC] is to evaluate if this was caused by mistake or neglect in carrying out law and regulation of the financial sector in Iceland and its supervision and who could be held responsible for it.” – In order to fulfil its goal the SIC was inter alia to collect information on the financial sector, assess regulation or lack thereof and come up with proposals to prevent the repetition of these events.

In some countries, most notably in South Africa after apartheid, “Truth Commissions,” have played a major part in reconciliation with the past. Although the remit of the Icelandic SIC was to establish the truth, the SIC was never referred to as a “truth commission” in Iceland though that concept has been used in foreign coverage of the SIC.

The SIC had the power to make use of a vast array of sources, both by calling in people to be questioned and documents, public or private such as bank data, including data on named individuals, data from public institutions, personal documents and memos. Data, normally confidential, had to be shared with the SIC, which was obliged to operate as any other public body handling sensitive or confidential information.

Although the SIC had to follow normal procedures of discretion on personal data the SIC could “publish information, normally subject to discretion, if the SIC deems this necessary to support its conclusions. The Commission can only publish information on personal matters of named individuals, including their financial affairs, if the public interest is greater than the interest of the individuals concerned.” – In effect, this clause lift banking secrecy.

One source close to the process of setting up the SIC surmised the political intentions behind the SIC Act did not include lifting banking secrecy, indicating that the extensive powers given to the SIC were accidental. Others have claimed the SIC’s extensive powers were always part of the plan. I am in two minds about this but my feeling is that the source close to the process was right – the powers to scrutinise the main shareholders were far greater than intended to begin with.

Naming the largest borrowers, incidentally also the largest shareholders

Intentional or not, the extensive powers enabled naming the individuals who received the largest loans from the banks, incidentally their largest shareholders and their closest business partners. This was absolutely essential in order to understand how the banks had operated: essentially, as private fiefdoms of the largest shareholders.

In order to encourage those called in for questioning to speak freely, the hearings were held behind closed doors; there were no public hearings. The SIC had extensive powers to call people in for questioning: it could ask for a court order if anyone declined its invitation, with the threat of taking that person to court on grounds of contempt in case the invitation was declined.

Criminal investigation was not part of the SIC remit but its power to call for material or call in people for questioning was parallel to that of a prosecutor. As stated in the report, the SIC was obliged to inform the State Prosecutor if there was suspicion of criminal conduct:

The SIC’s assessment, pursuant to Article 1(1) of Act no. 142/2008, was mainly aimed at the activities of public bodies and those who might be responsible for mistakes or negligence within the meaning of those terms, as defined in the Act. Although the SIC was entrusted with investigating whether weaknesses in the operations of the banks and their policies had played a part in their collapse, the Commission was not expected to address possible criminal conduct of the directors of the banks in their operations.

As to suspicion of civil servants having failed to fulfil their legal duties, the SIC was supposed to inform appropriate instances. The SIC was not obliged to inform the individuals in question. As to ministers, the SIC was to follow law on ministerial responsibility.

The three members

The SIC Act stipulated it should have three members: the Alþingi Ombudsman, then as now Tryggvi Gunnarsson, an economist and, as a chairman, a Supreme Court Justice. The nominated economist was Sigríður Benediktsdóttir, then lecturer at Yale University (director of Financial Stability at CBI 2012 to 2016 when she returned to Yale). The chairman was Páll Hreinsson (since 2011 judge at the EFTA Court).

In addition to the Commission there was a Working Group on Ethics: Vilhjálmur Árnason professor of philosophy, Salvör Nordal director of the Centre for Ethics, both at the University of Iceland and Kristín Ástgeirsdóttir director of the Equal Rights Council in Iceland. Their conclusions were published in Vol. 8 of the SIC report.

In total, the SIC had a staff of around 30 people. As with the Anton Valukas report, published in March 2010, on the collapse of Lehman Brothers, organising the material, especially the data from the banks, was a major task. The SIC had access to the databases of the three collapsed banks but had only limited data from the banks’ foreign operations.

There were absolutely no leaks from the SIC, which meant it was unclear what to expect. Given its untrodden path, the voices expressing little faith were the most frequently heard. I had however heard early on, that the SIC had a firm grip on turning material into searchable databases, which would mean a wealth of material. With qualified members and staff, I was from early on hopeful that given their expertise of extracting and processing data the SIC report would most likely prove to be illuminating – though I certainly did not imagine how extensive and insightful it turned out to be.

Greed, fraud and the collapse of common sense

After the October 2008 collapse, my attention had been on some questionable practices that I heard of from talking to sources close to the failed banks.

One thing I had quickly established was how the banks, through their foreign subsidiaries, had offshorised their Icelandic clients. This counted not only for the wealthy businessmen who obviously understood the ramifications of offshorising but also people with relatively small funds. These latters had in many cases scant understanding of these services.

In the last few years, as information on offshorisation has come to the light via Offshoreleaks etc., it has become clear that Iceland was – and still is – the most offshorised country in the world (here, 2016 Icelog on this topic). Once the “art” of offshorisation is established, with all the vested interests accompanying it, it does not die easily – this might be considered one of the failed banks’ more evil legacies.

Another point of interest was how the banks had systematically lent clients, small and large, funds to buy the banks’ own shares, i.e. Kaupthing lent funds to buy Kaupthing shares etc. Cross-lending was also a practice: Bank A would lend clients to buy Bank B shares and Bank B lent clients to buy Bank A shares. This was partly used to hinder that shares were sold when buyers were few and far behind, causing fall in market value. In other words, massive market manipulation had slowly been emerging. Indeed, the managers of all three failed banks have in recent years been sentenced for market manipulation.

It had also emerged, that the banks’ largest shareholders/clients and their business partners had indeed been what I have called “favoured clients,” i.e. enjoying services far beyond normal business practices. One side of this came to light in the banks’ covenants in lending agreements: in the case of the “favoured clients,” the lending agreements tended to guarantee clients’ profit, leaving the banks with the losses. In other words, the banks took on far greater portion of the risk than these clients.

Icelog blogs I wrote in February 2010, before the publication of the SIC report, give some sense of what was known at the time. Already then, it seemed fair to conclude that greed, fraud and the collapse of common sense had been decisive factors in the event in Iceland in October 2008.

Monday morning 12 April 2010 – when time stood still in Iceland

The excitement in Iceland on Monday morning 12 April 2010 was palpable. The press conference was transmitted live. All around Iceland employers had arranged for staff to watch as the SIC presented its conclusions.

After Páll Hreinsson’s short introduction, Sigríður Benediktsdóttir gave an overview of the main findings regarding the banks, presenting “The main reasons for the collapse of the banks,” followed by Tryggvi Gunnarsson’s overview of the reactions within public institutions (here the presentations from the press conference, in Icelandic).

The main reason for the collapse of the three banks was their rapid growth and their size at the time they collapsed; the three big banks grew 20-fold in seven years, mainly 2004 and 2005; the rapid expansion into new/foreign markets was risky; administration and due diligence was not in tune with the banks’ growth; the quality of loans greatly deteriorated; the growth was not in tune with long-time interest of sound banking; there were strong incentives within the banks grow.

Easy access to short-term lending in international markets enabled the banks’ rapid growth, i.e. the banks’ main creditors were large international banks. With the rapid expansion, also abroad, the institutional framework in Iceland, inter alia the Central Bank and the FME, quickly became wholly inadequate. The under-funded FME, lacking political support, was no match for the banks, which systematically poached key staff from the FME. Given the size of the humungous size of the Icelandic financial system relative to GDP there was effectively no lender of last resort in Iceland; the Central Bank could in no way fulfil this role.

This had no doubt be clear to the banks’ management for some time. In his book, “Frozen Assets,” published in 2009, Ármann Þorvaldsson, manager of KSF, Kaupthing’s UK operation, writes that he “always believed that if Iceland ran into trouble it would be easy to get assistance from friendly nations… despite the relative size of the banking system in Iceland, the absolute size was of course very small.” (P. 194). – A breath-taking recklessness, naivety or both but might well have been the prevalent view at the highest echelons of the Icelandic financial sector at the time.

The banks’ largest shareholders and their “abnormally easy access to lending”

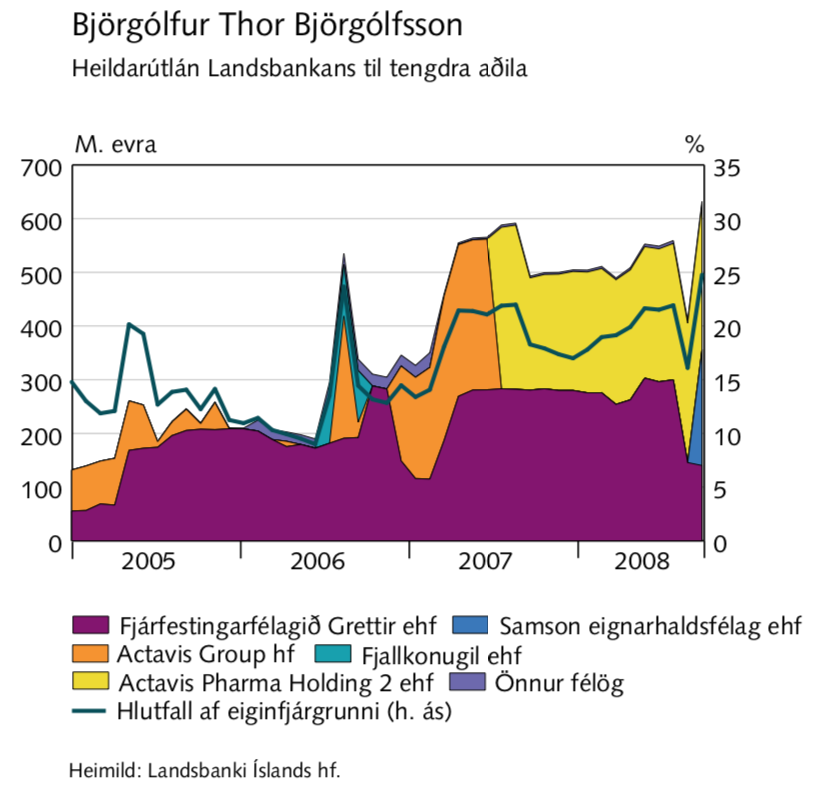

When it came to “Indebtedness of the banks’ largest owners” the conclusions were truly staggering: “The SIC concludes that the owners of the three largest banks and Straumur (investment bank where the main shareholders were the same as in Landsbanki, i.e. Björgólfur Thor Björgólfsson and his fater) had abnormally easy access to lending in these banks, apparently only because their ownership of these banks.”

The largest exposures of the three large banks were to the banks’ largest shareholders. “This raises the question if the lending was solely decided on commercial terms. The banks’ operations were in many ways characterised by maximising the interest of the large shareholders who held the reins rather than running a solid bank with the interest of all shareholders in mind and showing reasonable responsibility towards shareholders.” – Creative accounting helped the banks to avoid breaking rules on large exposures.

Benediktsdóttir showed graphs to illustrate the lending to the largest shareholders in the various banks. It is worth keeping in mind that these large shareholders all had foreign assets and were all clients of foreign banks as well. In general, the Icelandic lending shot up in 2007 when international funding dried up. At this point, the Icelandic banks really showed how favoured the large shareholders were because these clients were, en masse, getting merciless margin calls from their foreign lenders.

In reality, the Icelandic banks were at the mercy of their shareholders. If the large shareholders and/or their holding companies would default, the banks themselves were clearly next in line. The banks could not make margin calls where their own shares were collateral as it would flood the markets with shares no one wanted to buy with the obvious consequence of crashing share prices.

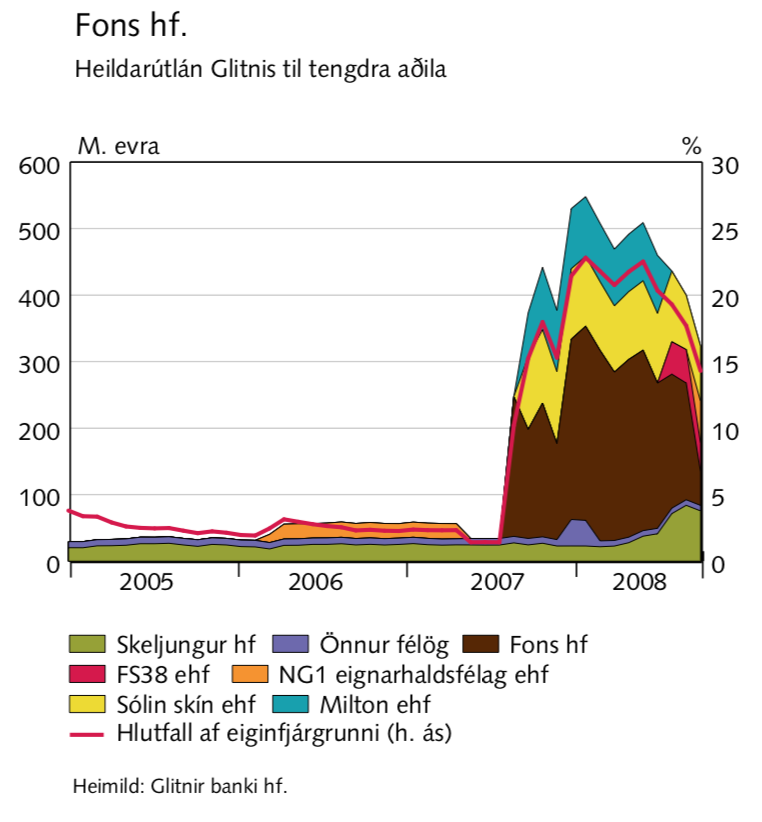

Two of the graphs from the SIC report, shown at the press conference in April 2010, exposed the clear drift in lending at a decisive time: to Björgólfur Thor Björgólfsson, still an active investor based in London and to Fons, a holding company owned by Pálmi Haraldsson, who for years was a close business partner of Jón Ásgeir Jóhannesson, once a king on the UK high street with shops like Iceland, Karen Millen, Debenhams and House of Fraser to his name.

The lending related to Fons/Haraldsson is particularly striking since Haraldsson was part of the consortium Jóhannesson led in spring of 2007 to buy around 40% of Glitnir: after the consortium bought Glitnir, the lending to Haraldsson shot up like an unassailable rock.

Absolution of risk