House searches in Landsbanki Luxembourg

Today (April 17), thirty people – six of them from the Office of the Special Prosecutor in Iceland – have conducted house searches in Luxembourg on behalf of the OSP. The searches have been ongoing at the office of the Landsbanki estate and at two addresses in Luxembourg. According to special prosecutor Olafur Hauksson the searches are connected to nine cases, which surfaced in the media after searches in Iceland in January last year.

As reported on Icelog earlier, the cases under investigation are thought to relate to the following:

1. Alleged market manipulation related to shares in Landsbanki.

2. Loans to four companies Hunslow S.A., Bruce Assets Limited, Pro-Invest Partners Corp and Sigurdur Bollason ehf. to buy shares in Landsbanki.

3. Landsbanki Luxembourg’s sale of loans to Landsbanki only a few days before the bank collapsed in Oct. 2008.

4. The buying of shares by eight offshore companies that supposedly were set up to hold shares related to employees’ options.

The loans to the four companies follow a well-known pattern from the Icelandic banks: huge loans, no collaterals or only the underlying shares being bought in the bank itself – and no apparent intention to have the investors shoulder any risk. All on the bank. It’s always interesting to observe who the benefactors of such loans are since such loans often reveal special relationships behind the banks’ choice of investors.

As pointed out earlier, “Hunslow S.A. was registered in Panama in Feb. 2008. In November 2009 two Novator companies (Novator is the investment fund of Bjorgolfur Thor Bjorgolfsson who was a major shareholder in Landsbanki and Straumur investment bank together with his father) were registered in Panama with the same law firm as Hunslow. The same five directors are on the board of the two Novator companies and Hunslow but there are probably hundreds of companies registered at this one law firm.” This doesn’t prove anything but it’s an intriguing fact.

According to Stoed 2, which broke the news today, Hunslow is owned by Stefan Ingimar Bjarnason, an Icelandic investor, who apart from having profited from Landsbanki’s generosity just before its demise, isn’t a well-known name in Iceland. Bruce Assets is owned by brothers, both known investors in Iceland but no high-flyers, Olafur Steinn and Kristjan Gudmundsson. Only last year did they appear as surprisingly big borrowers at Landsbanki. Interestingly, they invested in companies where Bjorgolfsson was a major investor. The brothers hadn’t been noticed because the loans, in total ISK23bn, all went to offshore companies they owned. The loans to the brothers seemed to have been issued against no collaterals or guarantees. As far as I can see, Bruce Assets is neither registered in Panama nor Luxembourg, can’t see where it’s registered (but would like to know, in case anyone knows).

Prior to the collapse, Sigurdur Bollason was an investor who frequently appeared alongside Jon Asgeir Johannesson and Baugur-related investments. Bollason was a big borrower, without any apparent merit except for strong relations to the banks’ favored circle.

Pro-Invest Partners belongs to a certain Georg Tsvetanski, a long-time business partner of Bjorgolfsson. Tsvetanski is an ex-Deutsche Bank banker. In 2004, he set up the investment fund Altima Partners in the UK together with other Deutsche bankers who specialised in Eastern Europe and who had, during their Deutsche time, cooperated with Bjorgolfsson. Among these are Radenko Milakovic and Dominic Redfern. This group was from from early on involved in Eastern European privatization from 2000, led by or done with Bjorgolfsson: Bulgartabak (which they didn’t get), Balkanpharma (later merged with Actavis), Bulgaria Telecom and in the Czech Republic, Cesky Telecom and Ceske Radiokomunkace.

Early on, Tsvetanski was for while on the board of Pharmaco, the owner of Balkanpharma. As the CEO of the state-owned Balkanpharma he had been a strategic partner. There seems to be an untold story in the privatisation process. Now and then there have been Bulgarian spurts to investigate the matter but so far, it’s never been done. Bjorgolfsson and Altima have also co-invested in Bulgarian properties, through their Luxembourg fund, Landmark.* A rather spectacular golf club and resort, Thracian Cliffs, seems to be a Landmark investment. One of Landmark’s board members is Arnar Gudmundsson, who is at Arena Wealth Management, run by Icelandic ex-bankers, with a very uninformative website. At the end of September 2008, only a week before the bank collapsed, Tzvetanski got an overdraft of ISK4.5bn.

It seems that some of these Landsbanki loans, now being investigated, were issued in Luxembourg. Many of my sources have mentioned that the Landsbanki saga can’t be understood except by mapping out the Luxembourg loans – the source of the dodgiest loans. And that’s where the OSP is at today.

*There is a small galaxy of Landmark companies registered in Luxembourg and some are attached to offshore companies with Icelandic names, ia Keldur Holding Limited, a BVI company and Gort Holding, a Guernsey company.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Monday April 23 – the verdict in the Haarde trial

The verdict in the Althing trial against ex-Prime Minister Geir Haarde will be announced next Monday at 2pm, Icelandic time (GMT). The ruling will be transmitted live. Yes, I will be watching.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Bruno Iksil, the $100bn bet and JP Morgan’s CDS

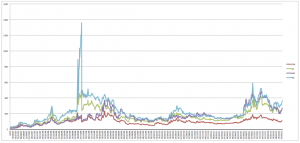

Is Iksil betting on the JP Morgan CDS spread? Well, at least JP Morgan’s CDS looks enviously better than the spread of the other Three Big banks. Their graphs separated late last summer.

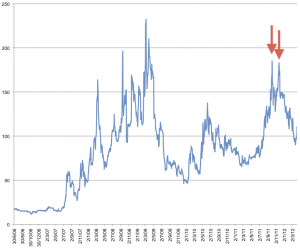

Earlier, I toyed with the idea that JP Morgan’s Bruno Iksil might be making these humongous bets to lower JPM’s CDS spreads. Here is some more data – comparing JP Morgan’s CDS with that of the three other big banks: Bank of America, Morgan Stanley and Goldman Sachs. Let’s look at the (illuminating?) graph:  It shows that before the enormous fluctuations in autumn 2008 the four banks had more or less been on the same road. Following the great quakes of autumn 2008, JP Morgan has slowly slowly separated itself from the other three. From last summer the three have been hovering together, ever rising and/or fluctuating more wildly than JP Morgan. True, this doesn’t prove anything – but it’s intriguing.

It shows that before the enormous fluctuations in autumn 2008 the four banks had more or less been on the same road. Following the great quakes of autumn 2008, JP Morgan has slowly slowly separated itself from the other three. From last summer the three have been hovering together, ever rising and/or fluctuating more wildly than JP Morgan. True, this doesn’t prove anything – but it’s intriguing.

JP Morgan might have been seen to have more prudent – though recent CFTC fines of $20m and various other things don’t seem to support that theory – and/or it might have been more clever at managing perceptions. Or, just possibly, it might have done like Kaupthing did, on Deutsche Bank’s advise, and made some clever trades to influence its CDS. Some question marks hanging in the spring air.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Could Bruno Iksil’s $100bn bet be related to JP Morgan’s own CDS?

Sounds like a crazy idea? Kaupthing, advised by Deutsche Bank, organised trades in 2008 to lower its own CDS. Deutsche co-invested in the scheme.

JP Morgan’s trader Bruno Iksil is the latest banker to gain unwanted fame for trading astronomical sums. He’s now even famous enough to have nicknames – the London Whale or Voldemort, after the Harry Potter villain. Iksil seems to have been betting investing in corporate CDS, ie Markit CDX IG (Investment Grade) 9 credit index, an index of investment grade corporate CDS, based on 121 (previously 125) big US corporations, financial and others.

Iksil works in the bank’s chief investment office, which manages and hedges “the firm’s foreign-exchange, interestrate and other structural risks,” according to the bank’s spokesman, focusing on long-term “structural assets and liabilities.” Iksil has placed such hefty bets, guessed to have reached $100bn, that he seems to be moving the index and that’s been irritating some hedge funds that are affected.

Trading in that index surged 61 percent the past three months, according to data from Depository Trust & Clearing Corp.

The net amount of wagers on the index, which is tied to the creditworthiness of companies such as Wal-Mart Stores Inc. and now-junk-rated bond insurer MBIA Insurance Corp., soared to almost $145 billion at the end of March from $90 billion three months earlier, according to DTCC, which runs a central registry for credit-default swaps and reports weekly aggregate volumes.

Perhaps the hedgies have been muttering to Bloomberg, first out with the story April 5, just because Iksil is affecting their positions. More pondering, info and graphs re Iksil’s trades on the wonderfully informative FT Alphaville. And there is speculation if this type of trades will become part of financial history when the Volcker rules come to rule, in July.

Iksil seems to be doing all of this not as a rogue trader but with the blessing from JP Morgan’s commanding heights. Maybe this is a clever long-time hedge. Perhaps perhaps… At least, the management doesn’t seem to mind Iksil risking/investing $100bn moving the market.

But what market are JP Morgan’s commanding heights glad he is moving? Just the index? Or might it be JP Morgan’s own CDS? Perhaps this is a completely freakish development but JP Morgan’s CDS was painfully high at the end of last year, almost as high as in autumn 2008, when all financial CDS shot up:

The most recent peaks, indicated by the arrows, are Oct. 4 and Nov. 25 2011.

From the beginning of this year the JP Morgan CDS has been steadily falling, as the graph shows. Interestingly, it has fallen in the last three months, when the trades in the CDS index has surged, apparently due to Iksil’s diligence. As pointed out earlier: possible just a freak development. Other forces than Voldemort’s might certainly be at large.

But can anyone be so hubristic/daring/foolhardy/foolish to manually influence its own CDS? Well, the know-how to influence one’s own CDS has been out there for a while. In the summer of 2008 Kaupthing was suffering from murderously high CDS – the management felt it was all horribly unjust since the bank was, according to the key figures, doing incredibly well.

Kaupthing seems to have aired their concerns with Deutsche Bank, which came up with a brilliant solution: companies should be created to buy CDS on Kaupthing. Deutshce seems to have thought it was a brilliantly viable plan – it even invested in it. Kaupthing implemented the idea – not via its prop trading, a la JP Morgan, but by getting favoured clients (some of whom the bank was lending heavily to invest in Kaupthing shares so as to keep the share price from crashing) to lend their names as owners of companies, which Kaupthing and Deutshce lent into – and then these companies did the trades. Did it help? Well, for whatever reason Kaupthing’s CDS did move… downwards.*

The interesting tail to both to the Kaupthing and Iksil trades would be to know who is on the other end. In Kaupthing’s case we don’t know but whoever it was did very very well.

Kaupthing did meet its end in October 2008 – bankrupt, as happens when the wrong decisions are taken over some time. JP Morgan can happily bet in whatever crazy way. Its management has tried and tested the ground – so far, a bank like JP Morgan won’t have to face the results of bad/insane decisions and hubris. Will banks be able to bank on that forever?

*Deutsche’s plan is outlined in the SIC report, chapter 7.3.6.3 (only in Icelandic).: Deutsche put up a loan of €125m and harvested handsomely: it got a fee of €5m for the package. In June 2010 Reuters reported that the Serious Fraud Office was investigating this scheme but nothing has been heard of it since. More here from Icelog on the scheme and those involved in it, ia Kevin Stanford and Karen Millen.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

SFO wrestles with the Tchenguiz case

Serious Fraud Office seems to have committed a major blunder in the handling of documents when Vincent Tchenguiz, together with his brother Robert, was arrested in March last year, together with Sigurdur Einarsson, ex-chairman of Kaupthing’s board and six others. The arrest was connected to an SFO investigation into the relationship between the Tchenguiz brothers and Kaupthing. According to the FT, a High Court judge has scolded the SFO for “sheer incompetence:” the SFO admits is has “no clear record” of the information it used to obtain search warrant. True, it seems pretty gross that the SFO can’t document the information used to obtain the search warrant – but this dispute doesn’t touch the substance of the charges, only the way SFO documented their case for making the arrests. And it seems only to relate to the warrant on Vincent Tchenguiz, not the others.

It is clear from the SIC report that Robert Tchenguiz was both Kaupthing’s largest borrower, with his loans of €2bn, and had stakes in the bank’s largest shareholder, Exista. He was on the board of Exista, whose founders and owners were Lydur and Agust Gudmundsson. This relationship – being a major shareholder and the largest borrower or among the largest borrowers – is the normal one in the most abnormal loans issued by the Icelandic banks: loans that ia broke the banks’ rules on legal limits exposure, had no or worthless collaterals, weren’t subjected to margin calls or paid by issuing new loans etc.

Vincent’s relationship to Kaupthing was far less extensive. He had a loan of €208m, which he seems to have taken/been offered as he put up an extra collateral for his brother. In court documents related to Vincent’s legal wrangle with Kaupthing over this collateral – a whole saga in itself, ended late last year with an agreement between Kaupthing and Tchenguiz’ entities – it’s clear that Vincent was of the understanding that Kaupthing wouldn’t claim the collateral.

Further, Vincent Tchenguiz also claims that Kaupthing knew the collateral couldn’t be claimed because of cross-default triggered if the assets changed hands. The value of an unenforceable collateral raises some intriguing questions, ia for the bank’s auditors since such a loan seems to be worth not much. Now, this is only Vincent’s side of the story. The Kaupthing managers haven’t told their story of this loan – nor of any of the loans, so abnormally favourable to the clients and abnormally unfavourable for the bank.

It seems pretty clear that the Kaupthing loans – as is true for the loans of Landsbanki and Glitnir to favoured clients – are far from normal. The question is why the banks decided these loans were a good idea for the bank. The Tchenguiz brothers have claimed that Kaupthing duped them into investing in the bank, that they didn’t know the bank was running a scheme, which could be seen as a market manipulation.

All these favoured clients, including the Tchenguiz brothers, are experienced businessmen. Same with Kevin Stanford, mentioned on an earlier Icelog: experienced business men must have known that the loans they were offered weren’t quite the run-of-the-mill loans any bank would offer. They would also know that borrowing from a bank doesn’t necessarily mean that the bank, as a side offer, peddles a loan to buy some of the bank’s shares. It’s normally not necessary to be a shareholder in order to borrow from a bank. Claiming to be a victim of Kaupthing managers’ duplicity makes these victims seem more than ordinarily naive.

Some of the favoured clients of the Icelandic banks have claimed that the offers were too good to refuse. The SFO seems to be investigating what the real relationship was between Kaupthing and the Tchenguiz brothers. If the SFO suspicions are valid it is unfortunate that they could possibly hinge on technical issues. Remains to be seen.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

The latest on the Haarde trial

After much criticism that the trial over ex-PM Geir Haarde wasn’t broadcasted, the Court, Landsdomur, has now put all the audio recordings of the witness statements online (obviously only in Icelandic). It was a great shame that the trial wasn’t broadcasted but, as they say in Icelandic, better late than never.

The verdict is expected later this month, nothing more exact than that. It’s not clear how far in advance the exact date will be given.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Guess who came to a Downing Street dinner? David Rowland

The UK Conservative Party battles against the sleaze that’s oozing out in the wake of the under-cover Sunday Times interview with Tory treasurer Peter Cruddas, now understandably the ex-treasurer. In the interview, Cruddas sets the rates for access to Tory leading lights, mentioning that £250.000 will get you a dinner with Prime Minister David Cameron. A case now called “Cash for Cameron” by the UK media.

Cameron completely denies all this, finds Cruddas’ entrepreneurship on behalf of the party “completely unacceptable.” Having admitted to invited some main donors to dinner, Cameron was forced to publish a list of those favoured with such favours. On the list is the man who was going to be treasurer himself, until he found out he didn’t have the time. That decision might have had something to do with a series of very unflattering articles that the Daily Mail published on him.

But however unflattering Daily Mail’s reporting did no lasting harm to Rowland’s reputation in Downing Street. On Feb. 28 last year, David Rowland and his wife were invited to dinner, together with Baron Andrew Feldman, ennobled by his friend Cameron for whom he has been a diligent fundraiser and now a co-chairman of the Conservative Party. They will most likely have sat in this nicely conservative state room above nr 11 Downing Street and sipped whatever those with conservative leanings sip.

Cruddas pointed out that by paying the £250.000 one would be in the “premier league” and would be listened to. Rowland is way beyond that since his contribution to the party is counted in millions of pounds. So what might he have discussed with Cameron? Apart from the usual, such as too much taxation, Rowland might have talked about the fantastic opportunities he finds in having a bank in Luxembourg and Monaco, a newspaper in Latvia and shares in the Icelandic MP Bank, not to mention Belarus.

Since Belarus has been in the news lately for political repression and horrors, Cameron could have been interested in Rowland’s Belarus venture, the first FDI fund there. At the time, Havilland’s press release was probably still on the Havilland website but it’s now been removed. We don’t know how Cameron’s staff prepared these dinners but most likely Cameron was more listening than questioning. After all, Rowland and other guests did quite a bit to bring Cameron to Downing Street and critical questions might have been as unacceptable as Cameron thought Cruddas’ fundraising initiative.

*Rowland also has ties to Prince Andrew. Here are links to other Icelog entries on Rowland.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Stanford, Millen and Tchenguiz: victims or favoured clients?

“In my opinion, it is quite wrong that a bank can pretend to have money and security which it doesn’t have, generate a false balance sheet and use its own customers to fund acquisition ambitions.” According to the Guardian, the fashion entrepreneur Karen Millen is pursuing a series of legal claims against the Kaupthing estate, together with her ex-husband Kevin Stanford (more on his Icelandic contacts). Millen is of the opinion that Kaupthing wasn’t entirely straight about its position. She might not be the only one to think so – but before it all went to painfully wrong, her ex-husband was indeed very close to the Kaupthing managers. It’s unclear how well informed Stanford kept his ex-wife on their business dealings. He was the financial motor in their cooperation, Millen the creative one.

Millen and Stanford built up a fashion label, the Karen Millen name is still prominent on UK high streets. But the name no longer belongs to her. Millen has lost her name to Kaupthing. She is understandably upset but she isn’t the first designer to lose her/his name to the bankers by being careless about the small print.

From the SIC report and other sources it’s clear that banking the Icelandic way implied bestowing huge favours on a group of chosen clients – in all three banks the banks’ major shareholders and an extended group around them. As so often pointed out on Icelog, these clients got convenant-light and/or collateral-light loans. In some cases the bankers promised their clients that the collateral wouldn’t be enforced – or the collateral were unenforceable for some reason. They were offered a “risk-free business” – ia risk-free for the customer whereas the bank shouldered all the risk and eventual losses. (This screams of breach of fiduciary duty, indeed part of charges brought in some cases by Office of the Special Prosecutor and not doubt more to come.)

After the collapse, some of Kaupthing’s favoured clients have claimed they were victims of Kaupthing’s managers who did not inform them of the bank’s real standing. Karen Millen is the latest to complain of Kaupthing misleading her. She is, understandably, outraged at not being able to use her name for her label. A clever lawyer would have made sure it couldn’t happen. Stanford was evidently very close to the Kaupthing managers, which might have lulled him into the false believe that he didn’t need to be too careful about the wording of the contracts.

How close was Stanford to Kaupthing? Just before the collapse he was the bank’s fourth biggest shareholder and among the largest borrowers – the familiar correlation between large shareholding and huge loans in the Icelandic banks.

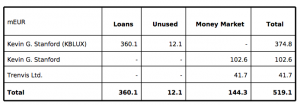

Here is an overview of Stanford’s loans September 2008:

What was this enormous business that Stanford was running that merited loans of €519m?

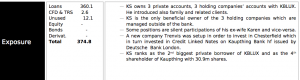

Here is how Stanford was introduced on the loan overview of exposures exceeding €45m:

Pay attention here. Stanford introduced “family and related clients.” – Did he, as sometimes happens, get paid for the introduction? – And then this, that some of this was “silent participation” of his ex-wife and vice versa. Did she have a full insight into how her name was used by her husband? Noticeably, he was the second biggest private borrower in Kaupthing Luxembourg, where all the dodgiest loans were issued.

Stanford’s Icelandic connections are on the whole quite intriguing. He wasn’t only closely connected to Kaupthing but also to Glitnir, at least after Jon Asgeir Johannesson, with ia Hannes Smarason and Palmi Haraldsson, became the bank’s largest shareholder in summer 2007. When Glitnir financed a clever dividend scheme in Byr, the building society, Millen suddenly appeared as one of the stakeholders in Byr. Was that because she was so keen to invest in an Icelandic building society? Some of Stanford’s fashion businesses were joint ventures with Johannesson and his company, Baugur.

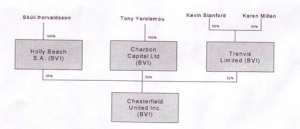

Stanford was also close enough to Kaupthing be part of a clever set-up to influence the bank’s scarily high CDS in the summer of 2008. Together with Olafur Olafsson, Kaupthing’s second largest shareholder, Tony Yerolemou and Skuli Thorvaldsson – all of them in the Kaupthing inner circle in terms of the business opportunities they got from the bank – Stanford and Millen owned one of three companies financed by Kaupthing to buy Kaupthing CDS. This was the set-up:

This scheme doesn’t seem to have hit Stanford and Millen with losses in spite of a loan of €41m to this entreprise.

Last year, Stanford wrote a letter to the Kaupthing Singer & Friedlander estate to substantiate his claim that he should not pay back KSF £130m he had borrowed to buy Kaupthing shares. According to his understanding, this lending was part of Kaupthing’s support scheme, in other words (which Stanford didn’t use) ‘market manipulation.’ – Stanford is and wants to be taken seriously as a business man. Didn’t he see anything strange in the fact that a bank was lending him money, with no risk for Stanford, to buy its own shares, with (if the scheme was the usual one) nothing but the shares as a collateral?

Stanford says that after talking to former Kaupthing Singer & Friedlander staff he now understands that the Kaupthing Edge deposits were used to buy ‘crap’ assets from Kaupthing Iceland, which lent the money on to Kaupthing Luxembourg that then had the money to lend to high net worth clients like Stanford. This scheme, according to Stanford, enabled senior Kaupthing managers to sell their Kaupthing shares.

This is an interesting description of the use of the Kaupthing Edge deposits, which (contrary to Landsbanki’s Icesave) were in a UK subsidiary and consequently guaranteed by the UK deposit guarantee scheme.* Stanford is right that the money was lent to high net worth clients – but not just to any clients: it was lent to the favoured clients who got the conventant-light loans. Kaupthing senior managers may have sold some of their shares but they did by far not sell out – it would have caused too much of attention and undermined trust in the bank.

Other big Kaupthing clients, like Vincent and Robert Tchenguiz, have also complained of being the victims of Kaupthing’s market manipulation. All these people are – or have been – locked in lawsuits with Kaupthing. The claims to the media is part of their PR strategy.

Being duped by Kaupthing means someone did the duping, allegedly the managers of the bank. Yet, none of these ‘ill-treated’ is suing any of the managers. They are suing the failed bank’s estate. That’s logical because the estate has assets. But it also raises the question if the strong bonds, which clearly connected the Kaupthing senior managers and their major clients, have survived the collapse and the consequent losses.

It’s also worth noticing that in spite of enormous loans that the favoured clients got, they have, like Stanford and the Tchenguiz brothers, proved remarkably resilient to losses. That may be due to luck, business acumen or both – but a part of it might also be the convenant- and collateral-light loans that Kaupthing did, after all, bestow on them. Which is part of the Kaupthing-related cases that both the Serious Fraud Office and the OSP are investigating. This way of banking runs against all business logic. The question is what sort of logic it followed.

*The fact that Kaupthing Edge was guaranteed by the UK deposit guarantee seems to be one of the motives for the SFO investigation. I find it incomprehensible that SFO isn’t investigating Landsbanki’s Icesave, which the UK Government did bail out – hence the Icesave dispute.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

The Irish Mahon report: a political corruption uncovered (albeit of the 80s and the 90s)

The 1990s in Ireland were characterised – much like the last decade – by property speculations, based on political connections. There were rumours about politicians getting paid for planning favours. These rumours were so persistent that in November 4 1997 a Tribunal of Inquiry into Certain Planning Matters and Payment was set up. Today, Thursday March 22, good fourteen years later and costing €300m, the Mahon tribunal, called after Judge Alan P. Mahon now its chairman, has published a 3270 pages final report, following four previous reports. It is, to say the very least, a damning description of politics, money and power in Ireland of the 1990s but also points out matters to consider in terms of ethics, regulators and politics.

Ex-Prime Minister Bertie Ahern and his source of money are at the centre of the report – and yes, the report finds ia that he accepted corrupt payments and used the accounts of his daughter Cecelia, now a famous writer, and wife to hide his corrupt income. His earlier explanations were “untrue” – Reuters is more blunt and says Ahern “lied.” Others named for dishonourable sources of money are former EU Commissioner and Minister Padraig Flynn, who on a popular chat show in 1999 defiantly refused rumours and accusations that he had taken money for political favours. The new report establishes that this wasn’t quite true.

Flynn and Ahern are only a few of many leading politicians from the 80s and the 90s whose reputation is now destroyed by the new report. A number of politicians from both main parties, Fianna Fail and Fine Gael, have been brought to court or indicted and cases are still running. More might be to come.

The Irish media and the whole nation has plenty to digest today. This investigation regards cases from over a decade ago and practices reaching back to the 80s. The report points out the staggering apathy there has been in Ireland regarding corruption. This might now be changing – but the question the Irish must be asking them now is how much Ireland has changed.

I have earlier compared Ireland and Iceland, ia on corruption (see ia here and here). After the Icelandic SIC report I pointed out that Icelanders knew a good deal more on their banking failure than Ireland. That changed to a certain degree after the publication of the Nyberg report though the SIC report goes into far greater detail on the major shareholders and the banks’ big clients.

It’s interesting to note that in spite of the entrenched corruption in Ireland it seems to be confined to the relationship between the property sector and politics. Ireland is doing well in attracting foreign investments in high-tech and biotech whereas Iceland is struggling in this respect.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

After the Haarde trial: a farce – or, actually, a trial?

There has widespread dismay in Iceland at the trial over ex-PM Geir Haarde – but not everyone is dismayed for the same reasons. Some are irritated that politicians and civil servants generally claimed nothing could have been done to prevent the collapse of the banks and that bankers can’t see they have done anything wrong. Others are upset that only one politician is on trial – there should have been more… or none.

When asked why Kaupthing had failed, the bank’s former CEO Hreidar Mar Sigurdsson said straightforwardly it had failed because of the Emergency Bill – the legislation passed on Monday Oct. 6 2008 to prevent a total chaos in Iceland as the banks were collapsing. Sigurdsson’s view is, to say the very least, quite narrow. On Friday Oct. 3 the Bank of England had already taken action against Kaupthing by taking over all new deposits to Kaupthing. Sigurdsson didn’t mention this action, which marked the beginning of actions against Kaupthing in the UK.

It needn’t come as any surprise that no one accepts any responsibility – that was already clear from the SIC report, ia based on extensive interviews with many of those involved. This tone of “it wasn’t me” or “nothing could be done” is abundantly clear from the quotes in the report.

It’s unlikely that any of the witnesses took much joy in bearing witness. Many of them will still feel uneasy about the past – and their future. Several of the witnesses at the Haarde trial have already been indicted by the Office of the Special Prosecutor – Sigurdsson is one of them – and/or are being sued by the Winding-up Boards of the banks and others might face lawsuits and charges. Everything they say will be coloured by their situation. Many of them have most likely rehearsed their answers with their lawyers.

Complaints that the trial is a farce seem to rest on a wholly unrealistic understanding of the nature of the trial. The trial is held because Haarde is accused of failures in office. The charges are built on a documentation of alleged failures. The trial is an act where the prosecutor seeks to clarify the documents and Haarde’s defence lawyer seeks to defend his client. The High Court Judges will come to their conclusion in 4-5 weeks.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.