‘Money isn’t everything’

Walking through ‘Hljomskalagardurinn’, the little park by the pond in the centre of Reykjavik, earlier this evening the city seemed to be at the heart of Southern Europe: the temperature is around 20 degrees and the sun is still shining now just after 9pm. Every city shows its best side on a sunny summer evening but I don’t know any city that so much opens up and spreads out its charm as does Reykjavik on a evening like tonight. Especially because the inhabitants, not always caressed by the elements, show their uninhibited appreciation of their good luck and turn very cheerful. Even the ducks and geese swim merrily in the saturated colours.

It is a truly magical evening – and the weather has been like this most of the summer. It seems that every summer is just better than the one before or rather, that’s what it’s like in Southern Iceland. The Northern part seems to have lost its warm summer that everyone in Southern Iceland was envious of. And there is a vibrant atmosphere, with open shops and cafés. On Saturday there is the annual ‘culture night.’

And Bankastraeti, ‘Bank Street’, could be San Francisco.

At Christmas 2006 I sat at this same café, b5 and heard, on my right, young men in black planning to buy an airline. An identical group, to my left, were planning to buy a bank. Tonight, one of these breathtakingly good-looking Icelandic girls passed me just above the café, talking to a friend. The sentence I caught was: ‘Money isn’t everything.’

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Einarsson: the future is unclear

Around 6pm the Office of the Special Prosecutor decided to call it a day – and Sigurdur Einarsson left the office after a whole day of interrogations. As he left he said to the media that all allegations against him are wholly unfounded. The Kaupthing management had not been involved in market manipulation, fraud or embezzlement as the investigations indicates.

The OSP isn’t finished with Einarsson just yet. He has to show up tomorrow for another day. It’s still unclear if he came to some sort of an agreement with the OSP that he would only show up if he wouldn’t be put into custody though it seems, a priori, rather unlikely that the OSP would do such an agreement.

The UK Serious Fraud Office is conducting its own investigation into Kaupthing. The OSP and the SFO are collaborating though the investigations are independent of each other.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Sigurdur Einarsson: off the Interpol list and in Iceland

Sigurdur Einarsson, Kaupthing’s ex-executive chairman no longer figures on the Interpol wanted list. His name was taken off the Interpol list on Tuesday. Yesterday, he arrived in Iceland and is now being interrogated by the special prosecutor. The investigation by the Office of the Special Prosecutor relates to alleged market manipulation, fraud and embezzlement.

As he arrived this morning at the OSP he said to the journalists waiting for him that due to having his name on the Interpol list he had been unable to travel and that it hadn’t been a pleasant experience. He said he didn’t know how long he would stay in Iceland and added that his conscience was clean. Noticeably slimmer than last time seen he arrived accompanied by his lawyer Gestur Jonsson who was the lawyer of Jon Asgeir Johannesson during the Baugur trials some years ago.

In May, some Kaupthing ex-managers were kept in custody, the longest for ten days, as the OSP investigated their statements. At the time, Einarsson was due to appear but allegedly changed his mind when he saw the treatment his collegues received. The OSP reaction was to have Einarsson put on the Interpol list. The has effectively meant that Einarsson was in involuntary custody in London where he lives.

The development at the OSP today and the coming days will be in the glare of the Icelandic media.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

UK: still no questions asked?

‘If the RBS had gone down it would have taken the rest with it,’ Alistair Darling, ex-Chancellor of the Exchequer, said on the BBC’s Today programme earlier this morning. He was being asked about the events in October as Royal Bank of Scotland and other banks were teetering on the brink of bankruptcy. Darling told how a senior executive of RBS had been in touch with him saying that the bank would go under in just a few hours. ‘Happily we did have a plan and we stopped the bank from closing,’ Darling said – and the government stepped in. The financial system didn’t go under, money could still be taken out of cash machines and bank accounts. Just like in Iceland the UK banks were pulled through and there wasn’t a break down of the financial system.

But unlike Iceland the Labour government at the time and now the coalition government of Conservatives and the Liberal Democrats have done nothing to poke around in the once-teetering banks to understand what happened at the RBS and other banks that had to be saved. It’s almost a law of nature that in companies heading for bankruptcy things are done that aren’t necessarily entirely legal – or entirely cricket at the Brits say.

Whom was the RBS lending to? Some Icelandic businessmen, among others. RBS headed for world dominion, or at least to grow faster than fast and bigger than big. And so it did. That’s what Kaupthing was doing as well. The strategy of growth above everything tends to lead to unwise and imprudent lending. Plenty of that in Kaupthing, also to UK clients like the Tchenguiz brothers, Kevin Stanford and others. And at the RBS? We don’t know because the bank hasn’t been picked over by the FSA or any UK authority. Neither has HBOS or Lloyds or any of the other UK banks that needed assistance at the time. Yes, admirably the Parliament has asked questions and produced reports but nothing that’s nearly enough to explain and clarify what was going on in the banks at the time.

And so it is that billions of public money were poured into the UK banks, no questions asked. Iceland has had its very thorough report of the operations of the collapsed Icelandic banks. In the US much has been done and many stories have come out, clarifying what went on in the US banking sector. In the UK: nothing.

Just as in Iceland British politicians were eager to see the growth of the banking sector in the years up to 2008. Leaders like Tony Blair and Gordon Brown were visibly in awe of the financial wizards of the City. Industry has been disappearing in the UK over the past decades, factories closing. Banking was the economy’s new save-all. In Iceland, the dream of making Iceland an international financial centre completely blinded the politicians. And the financial and regulatory authorities.

The same happened in the UK. The FSA was either inept or unable to keep up with the growing and ever more complicated financial sector. At the time, I thought that since the Icelandic banks operated in the UK nothing much could be wrong with them since the FSA surely would be a strict regulator in a country with such a big financial sector and so much attention and focus on it as well as a great tradition of making laws and regulations. – That turned out to be far from the truth, as the SFO might be finding out if it doesn’t give up on investigating Kaupthing. And the FSA probably didn’t too great a job on the UK banks either.

Now the UK coalition government is readjusting the architecture of the FSA but it will be run by Hector Sants as earlier. There is no indication of acknowledging what went wrong and why, let alone investigating anything at all. The Conservatives are living up to their reputation of being intimate with the City. And it doesn’t seem to change a thing that the Lib Dem Vince Cable, earlier so vocal and clear in criticising the banks, is now a business secretary.

As the two years’ anniversary of the financial world crisis nears, Icelander are well informed about the operation of the collapsed banks. In the UK nothing is or has been done to investigate the operations of the banks leading up to the collapse of some of the UK banks. And the otherwise so outstanding Today journalist who interviewed Darling this morning didn’t even think of asking why the Labour government hadn’t done anything to investigate the banks.

The UK seems to be like Luxembourg: the banking sector here is too omnipotent and influential, too wedded to the political sphere, to be asked impertinent questions.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Iceland seen from Italy

My annual Italian vacation is coming to an end. I’ve been coming regularly to Italy for twenty years now, speak Italian and in general understand the Italian way of thinking and being – coming here feels like coming home since it’s all very familiar. I know that only a few minutes after I land I’ll hear someone discussing what they had for dinner last night, what they are cooking tonight or remembering some good food they’ve had recently.

There are, however, darker sides to this country than it’s love of food. It isn’t for nothing that the Italian word ‘mafia’ has entered the global vocabulary. But it isn’t something that you necessarily notice when you just fly in and fly out for vacation. Some years ago I spent a few weeks in Naples, in Monte Santo, at the centre, or rather at the heart of the city. I would buy my capuccino at a small bar where I was usually the only guest – this was in August, the traditional Italian holiday month – and I would get my mozzarella and tomatoes from a tiny grocery shop run by two elderly men in the steep maze that is Monte Santo. All so friendly and wonderful.

But when I asked Lidia (not her real name), a middle-aged lady who grew up in Monte Santo, if the inhabitants noticed the mafia she explained that only those who run a business come in contact with the dark forces. ‘And they all pay, no matter what they say!’ As a young woman her dream had been to set up business in Monte Santo. When the opportunity arose she decided against it. ‘I couldn’t bear the idea that part of the money I earned with my own hands would end up undeserved in the hands of the bad lot.’

I’ve often said that I didn’t understand Iceland until I got to know Italy. In Iceland, like in Italy, everything is resolved through personal relations if possible. And in both countries it isn’t easy to be a foreigner because then you are without the personal connections unless you are married into an Italian/Icelandic family. It’s the ample space of personal relations that can easily be a fertile ground for corruption if decisions are made regardless of merit or against the interest of the community but solely in the interest of the few who are more powerful than others.

In summer 1992 the Sicilian investigative judge Giovanni Falcone was brutally assassinated by the mafia together with his wife and bodyguards. Just a few weeks later another prolific colleague of his, Paolo Borsellino, was also assassinated, together with some of his bodyguards as he came for his regular Sunday visit to his mother. Falcone once said that the mafia operates where the state isn’t present. And there is plenty of space in Italy where the state isn’t present. It’s the same in Iceland – plenty of space where things are resolved by personal contacts without official control or transparency.

Until recently, when comparing Iceland and Italy, I would always add that the main difference between Italy and Iceland was that there was no money to speak of in Iceland – and of course there isn’t organised crime in Iceland. Not at all.

But then, around 2004 Iceland was awash with money, mostly borrowed from abroad. We now know, broadly speaking but not in detail, how the banks lent that money: it was mostly lent to a small group of businessmen, closely related to the banks. They used the Enron system: create a myriad of companies where the loans were place, to move assets and debt about which makes it very difficult to keep an overview – and that’s of course the advantage for those who want to evade control and transparency.

But unlike Enron the Icelandic myriad of companies was privately related to these businessmen who are thought to have tunnelled money out of these companies into their own private companies, well hidden from the view of the banks’ resolution committees. The Glitnir charges in New York are one attempt to claw back some of this money. – Interestingly, the big shareholders didn’t go bankrupt though their shareholdings in the banks, thought to be their main assets, evaporated with the collapse of the banks in October 2008.

Just recently, the Italian police imprisoned 300 gangsters connected to the Calabria mafia called ‘Ndrangheta’ – the Italian mafia has several names according to where it operates. In an article in Foreign Policy recently the journalist Alexander Stille recounts these events and their connection to Italian politics. It may come as a surprise to readers unfamiliar with Italian affairs how explicitly Stille discusses the alleged mafia connections of Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi but that’s how things are talked about in Italy. Ever since Berlusconi entered politics in the early 90s it’s been clear that he is in politics to guard his private interests that are unaligned to the interests of his county – and yes, yet he’s voted into power again and again, one of the paradoxes of this country, another story.

Part of the Italian mafia story is the connection with Italian politics as Stille’s article shows. The Icelandic political parties and individual politicians got handsome donations from the banks and the companies that thrived on handouts from the banks. In order to understand the Icelandic story of recent years it’s important to keep in mind the connections between politics and business.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

More on Rowland and Kaupthing

The Daily Mail, a UK newspaper, has taken quite an interest in David Rowland, the media-shy millionaire that lived in Guernsey until recently when he felt a pressing urge to donate £2,7m to the Conservative Party. Earlier this year, the party nominated Rowland its new treasurer, due to take office now in autumn. Daily Mail has been untiring in digging up interesting stories about Rowland in order to show the Conservatives predilection for shady money men. As the new owner of Kaupthing Luxembourg, now Banque Havilland, Rowland is of a particular interest to those interested in the aftermath of the collapse of the Icelandic banks.

August 7 Daily Mail came up with a very Daily-Mailish photo of the married Rowland sitting with a middle-aged blond in his lap. Not his wife but, according to the paper, an Italian property agent working in Antigua who, in spite of the intimacy of the scene, wasn’t at all taken in by Rowland. She said he presented himself as a single man but she likes men with ‘more soul’ – and apparently Rowland doesn’t meet that standard. All this according to Daily Mail.

The photo was allegedly taken in Antigua in autumn 2008, a few weeks after Kaupthing collapsed. Rowland was then on this Carribean island pursuing his interest in a property development, i.a. in Hodges Bay, a $60m waterside development where Kaupthing had been the main financial backer.

The collapse of Kaupthing was yet another setback for the Antiguan government – after all, Allan Stanford who is now charged in the US with a $8bn fraud ran his bank and the fraudulent schemes in Antigua. But the Hodges Bay Club still exists and is, according to the club’s website ‘now the reality of a very exclusive dream.’

Who Kaupthing was backing isn’t at all clear since the club’s website doesn’t contain any information on who now owns the club. Kaupthing funded various luxury developments, most noticeably with the Candy brothers. It would indeed be of interest to know who the Kaupthing clients were in the case – the development seems to have been run from London.

But back to David Rowland: it’s mighty interesting that Rowland was scrutinising the Kaupthing backed development because it shows some Rowland ties to Kaupthing. According to the lady on his lap in the end Rowland didn’t invest in the club.

The official Rowland story is that Blackfish Capital, the Rowland investment fund, first became involved with Kaupthing in early spring 2009 as the negotiations with the Libyan Investment Authority on buying Kaupthing Luxembourg collapsed. The Libyan deal collapsed because the bank’s creditors didn’t accept it. Blackfish Capital became involved because the Rowlands, David and his son Jonathan now CEO of Banque Havilland, had been in touch with Kaupthing Luxembourg manager Magnus Gudmundsson earlier that year when the Rowlands were buying some bonds from the collapsed bank.

The rumour in Luxembourg is that Kaupthing’s major shareholder and/or managers were in touch with the Rowlands and still have an interest in the bank. The fact that the Rowlands kept the Icelandic management seemed to support these rumours. It wasn’t until Magnus Gudmundsson was put into custody in Iceland in May that the Rowlands sacked him. The Rowlands firmly deny any contact with Icelanders, earlier connected to Kaupthing.

The fact that Rowland went to Antigua to look into the Kaupthing-related investment is interesting because it shows an earlier Kaupthing connection.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Viking-raider spotting

There are the train spotters, bird spotters, yacht spotters, plain spotters – and now the Viking raider spotters! Viking raider spotting has turned into a popular hobby in Iceland where emails and rumours circulate with news of ‘last-seen’. There must be an upcoming website soon.

As I was writing the last log, on Bjorgolfur Thor Bjorgolfsson, I got an email from an Icelandic friend with the news that Bjorgolfsson had been seen in front of a fitness centre. He was talking loudly on the phone, in English, ‘as if he owned the place,’ my friend added.

Recently, I heard of Larus Welding jogging in North London where he now lives (as is clear from the court documents in the charges Glitnir is bringing against Welding, Jon Asgeir Johannesson, his wife Ingibjorg Palmadottir, Palmi Haraldsson and others in New York). Welding was the Glitnir CEO who served Johannesson and Haraldsson rather too well, according to the charges.

A couple of weeks ago the newspaper DV heard of Hannes Smarason being in town, in Reykjavik. Smarason has been living in London the last few years. DV did try to spot him but always came too late – he moved around faster than the DV photographer. When DV visited a villa in an attractive part of town that used to belong to Smarason the wife of Magnus Armann answered the door bell and drove the reporter away. As the paper pointed out, this was interesting since Armann has been closely linked to many of Jon Asgeir Johannesson’s now failed investments and the two have been closely linked to Smarason as well. They still stick together, DV concluded.

Landsbanki lent money to Smarason to buy this villa, indeed he bought two, next to each other. As with the three flats in Gramercy Park that Landsbanki financed for Johannesson Landsbanki has been unwilling to clarify if the bank has repossessed Smarason’s villa. It seems clear that the loan hasn’t been paid but it seems that he still has use of the villa where his friends the Armanns have been staying according to DV.

Apart from the spotting: it’s intriguing to see that now, almost two years after the collapse of the three Icelandic banks and various other financial institutions most of the former high-fliers are still flying high. Gone are the yachts and the private jets, as far as we know, but they all seem to be in business and, with only two exceptions (Bjorgolfur Gudmundsson and Magnus Thorsteinsson) certainly not personally bankrupt.

Glitnir was the first – and so far the only – bank to bring charges against those who according to the report of the Althingi Investigative Commission did so dismally run down the Icelandic banking system. We are still waiting to see what Kaupthing and Landsbanki will do – the managers and the biggest shareholders in these two banks acted no less questionably, according to the report, than the ‘cabal of businessmen led by a convicted white collar criminal Jon Asgeir Johannesson,’ to use the phraseology from the Glitnir charges in New York.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Thor Bjorgolfsson – apparently saved, but Icesave still nagging

According to news in Iceland today, Thor Bjorgolfsson has now been saved from the threat of a personal bankruptcy. This seems to imply that he has reached an agreement with Deutche Bank on his debt in Actavis – and must have done the same with his Icelandic creditors. According to his spokesman, he had nothing to do with the running of Landsbanki, where he was the biggest shareholder together with his now bankrupt father, implying that he wasn’t like Jon Asgeir Johannesson who Glitnir is accusing of putting pressure on Glitnir’s managers to tunnel money his way. Accordingly, Icesave is none of his responsibility, says the spokeman.

There will be many Icelanders who ask if this really is the end of story regarding Bjorgolfsson’s involvement with the Icelandic banks. After all, it so happens that as Landsbanki collapsed Bjorgolfsson personally and companies related to him were the largest debtor in the bank. However he did secured the loans for himself and his companies Icesave was an important source of all loans issued from late 2006 when Icesave was set up, demonstrating the bank’s ‘pure genius’ (tær snilld) as the then CEO of Landsbanki Sigurjon Arnason proclaimed it at the time. As the banks collapsed, Bjorgolfsson was nr 5 on the list of the largest debtors in the three banks.

Bjorgolfsson was the main shareholder of the investment bank Straumur, now in moratorium but possibly soon in business again. Incidentally, Straumur was very keen to invest in companies related to Novator.

The report of the Investigative Commission offers many interesting insights into Bjorgolfsson’s way of doing business. As the banks were collapsing in October 2008 there were hectic meetings where Bjorgolfsson, not on the bank’s board, seemed to be the bank’s main representative. He assured the others that Landsbanki was alright, the problems had been solved, leading some politicians and bankers to go on record in the report saying that Bjorgolfsson was a liar.

However, if things do indeed go as his spokesman has now stated, things are indeed going to be just fine for the investor himself.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

A PS to the Johannesson Freezing Order

Part of Glitnir’s arguments for the international freezing order against Jon Asgeir Johannesson relates to a €13,6m loan to 101 Chalet, a company owned by Johannesson and Palmadottir, his wife and ‘alter ego’, to use the phraseology from the Glitnir charges brought in New York against the couple together with five others. An interesting addition to this story is that according to the Glitnir QC Richard Gillis Johannesson claims that his sister, Kristin Johannesdottir who’s been a director in many companies related to her brother, signed a guarantee for the loan, without his knowledge.

The report of the Investigative Commission points out that ‘innumerable companies’ are related to Gaumur, the holding company of the Johannesson’s family, with extensive ties to offshore secrecy jurisdictions. 101 Chalet is one of them, owned by Johannesson and his wife. The 101 Chalet loan was a key argument in Glitnir’s motivation for the freezing order since it’s both shows how intertwined the couple’s assets are and how assets were moved between companies and eventually beyond the reach of creditors.

Instead of insisting that the Johannesson companies sold assets and paid up debt during the difficult times of August 2008 Glitnir issued a 13,6m loan to 101 Chalet to buy a chalet in Courchevel. At the time, the owners of 101 Chalet claimed that a loan from a foreign bank was coming their way. Glitnir’s management only accepted though to issue a bridge loan for three months and sought to secure its interests with a letter from the chalet-buyers that the chalet would be sold if the other loan hadn’t materialised in three months and the Glitnir loan repaid. In addition, Glitnir had collaterals in 101 Chalet and in Piano Holding, a Panama company holding the 101 Heesen yacht (sold by the Kaupthing Luxembourg administrators, Banque Havilland, last year). When the loan wasn’t repaid it transpired that the Piano Holding guarantee was worthless from inception because the 101 yacht had been encumbered.

In addition, Glitnir sought a guarantee from Gaumur, signed by Johannesson, his sister and his father.

Three months later, Glitnir had collapsed and no other loan had been secured for the chalet. However, the chalet wasn’t sold until more than a year later. During the freezing order case Johannesson admitted that the 101 Chalet loan contract had been breached.

As with so many of the loans to the Icelandic banks’ chosen customers the loan to 101 Chalet was passed on to another Baugur company, BG Danmark. Last year, when the chalet was finally sold the proceeds from the sale didn’t go to Glitnir but to Palmadottir. Johannesson has now paid ISK2bn to Glitnir but Glitnir notes that the money is partly coming from Palmadottir, not out of Johannesson’s assets. Another chalet, previously owned by BG Danmark is amongst the assets of the now bankrupt Baugur in Iceland and 101 Chalet’s value is 0 on the list of Johannesson’s assets.

An interesting twist in this tale is that in QC Gillis’ skeleton statement it says: ‘Mr Johannesson sought to argue that the personal guarantee* in his name had been signed by his sister without his authority.’ – I leave it to the readers to interpret what this implies.

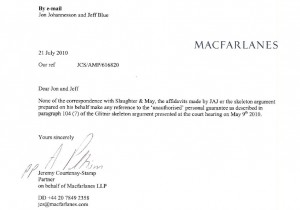

Johannesson’s sister firmly denies having signed the Gaumur guarantee without her brother’s authority. Johannesson hasn’t been interviewed on this issue. He has however issued a statement** saying that he has never accused his sister of having signed anything without his knowledge. Attached to his statement is a letter from his lawyer Jeremy Courtenay-Stamp.

Plenty of conflicting stories here – so there must be more to come…

*The Gaumur guarantee.

** In Icelandic but there are quotes there in English. The letter above is from Johannesson’s statement.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

The collective amnesia – will there be the Johannesson Institute?

Back in the 80s, one of the highlights of the year in the US financial sector was the annual Beverly Hills’ junk bond convention organised by the godlike junk bond king, Michael Milken. But as so masterly recounted in ‘The Den of Thieves’ – and confirmed in a US court, Milken was a common fraudster, convicted and sentenced to ten years in prison after being indicted on 98 counts of racketeering and fraud. This included a whole raft of illegal activities such as insider trading, stock parking, tax evasion and taking cut of illicit profits that others gained based on Milken’s information. This looks like a list of activity some of his Icelandic brothers-in-spirit might eventually be convicted of if the Office of the Special Prosecutor is on the right track.

In an interview recently in Iceland Eva Joly, the investigative Norwegian-French judge who sent around 30 high-placed people to prison in the Elf trial, pointed out that some high-flyers never admit to any wrongdoing even when they are convicted and sent to prison. Milken was one of them. This is the story according to the man himself, as published on his website:

“In 1989, the government charged Milken with securities/reporting violations in a case that continues to engender controversy. He admitted conduct that resulted – during a brief period in his 20 years on Wall Street – in five violations. Although such conduct had never before (nor has since) been prosecuted criminally – a fact rarely mentioned in press reports – he resolved the case without a trial to prevent further impact on his family. After paying a $200 million fine and serving a one-year-and-10-month sentence, he resumed his philanthropic work.”

Milken’s version skips the fact that he has a lifetime ban on working in securities and paid around $1,1bn in fines and various settlements with the SEC and investors who lost money on his schemes – not to forget that he was indeed convicted and received a sentence of ten years, out of which he should serve a minimum of three years. In the end he only served just over two years because he was diagnosed with prostate cancer with only around two years to live.

Yet, he still lives to tell the story and the glamorous Beverly Hills conference, now the Global Conferencen, is again a major get-together, last held in April this year. Milken is still among the wealthiest people on this planet and has been very astute at using his wealth to buy himself respect and a seat at the right tables. His story is an intriguing example in any debate on whether crime pays – his $200m SEC fine bore no relation to the sums he made on the activities he was fined for. This spring, he shared the podium at the Global Conference with no less than the economist superstar Nouriel Roubini – which to my mind rather reduced Roubini to a junk bond status.

Icelanders follow with avid interest how those who bankrupted the Icelandic financial system – bankers and businessmen alike – still live in apparent wealth. Just this week, it turned out that Magnus Kristinsson and his family all drive around in big and expensive cars though the banks have had to make a ISK50bn, £265m, write-off on his debt. At the height of the folly, Kristinson commuted from his home in the Vestman Islands by his own helicopter – his original source of wealth was fishing. Kristinsson is unknown abroad but well known in Iceland, i.a. for owning Gnupur, an investment company that was the first – and only – investment company to fail during the winter of 2007-08. Its collapse immediately sent the banks’ CDS spreads sky-rocketing and a shiver down the spine of bankers and businessmen: if this was the effect of the bankruptcy of a small obscure investment company it was obvious that if a major company like Baugur, FL Group or Exista would fail the effect would be cataclysmic. The banks made sure it didn’t happen.

The question in Iceland is if and when the Viking raiders and their bankers will go to prison. The story of Michael Milken shows that crime can pay. For the time being, names like Johannesson or Bjorgolfsson only attract scorn and anger in Iceland – but if Icelanders will be hit by the same kind of general amnesia that helps Milken buying his place in elevated company there might be Icelandic institutions in the future bearing these and other now so infamous names.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.