Archive for August, 2019

Jim Ratcliffe and his feudal hold of Icelandic salmon rivers and farming communities

The largest landowner in Iceland owns around 1% of Iceland, mostly land adjacent to salmon rivers in the North East of Iceland – and he is not Icelandic but one of the wealthiest Brits, James or Jim Ratcliffe, a Sir since last year, of Ineos fame. His secretive acquisitions of farms with angling rights have been facilitated by the Icelandic businessmen who for years have been investing in salmon rivers through offshore companies. Opaque ownership is nothing new. Though the novelty is the grip on these rivers now held by a foreigner, with no ties to the community and assets valued at just above the Icelandic GDP, the central problem is mainly the nationality of the owner, but the concentration of ownership.

“If you are doing honest business, I assume you would feel better if you could talk freely about it. This secrecy breeds suspicion,” says Ævar Rafn Marinósson, a farmer at Tungusel in North East Iceland. The secretive business he is talking about is the business of buying farms adjacent to salmon rivers in his part of Iceland.

The secrecy is not new: for more than a decade, the ownership of the attractive salmon rivers in Iceland has been hidden in an opaque web of on- and offshore companies. That opacity might now hit the community when rivers and land is increasingly being held by one man, Jim Ratcliffe, whose assets are estimated £18.15bn. Through direct and indirect ownership, Ratcliffe owns over forty Icelandic farms concentrated in and around Vopnafjörður, which gives him the control of angling rights in some of the best salmon rivers in Iceland.

The petrochemical giant Ineos is Ratcliffe’s source of wealth. Interestingly, his salmon investments are part of his recent, rapidly growing investment in sport, from cycling, sailing and football to his, so far, tentative interest in British Premier League football clubs with price tags of billions. Ratcliffe claims that his petrochemical industries are run in an environmentally friendly way and strongly denies that his sport investments are any form of green-washing.

The secrecy surrounding Ratcliffe’s Icelandic investments, so out of proportions in this rural community of salmon and sheep farmers, has bred both rumours and suspicion that splits apart families, neighbours and the local communities as they debate whether the funds on offer are a substitute for losing control of the angling and the land.

Also, because Ratcliffe is a distant owner. He leaves it to his Icelandic representatives to talk to the farmers some of whom, like Marinósson, refuse to sell and as a consequence feel harassed. And then there are the pertinent questions of how Ratcliffe’s funds flow into the local economy, as one farmer opposed to Ratcliffe’s growing hold of the region, mentioned in an interview in the Icelandic media.

Following Ratcliffe’s purchases, foreign ownership of land is now a hot topic in Iceland. The government is looking at legal restrictions to limit foreign ownership. A new poll shows that 83.6% of Icelanders support this step. – But that might be a mistaken angle: the problem is not foreign ownership but concentrated ownership.

“I’m not upset with Ratcliffe, he’s just a businessman pursuing his interests. I’m upset with the government of Iceland that is letting this happen,” says Marinósson. He is not the only one to point out that a new legislation might come too late for the salmon rivers in the North East.

Angling – strictly regulated

Though far from being a mass industry, angling has long been both a beloved sport in Iceland and attracted wealthy foreigners. In the early and mid 20th century, English aristocrats came to fish in Iceland. In the 1970s and 1980s, the Prince of Wales was fishing in Hofsá, now controlled by Ratcliffe. With the changing pattern of wealth came high-flyers from the international business world.

As angling interest grew, net fishing for salmon was restricted so as to let the angling flourish. In 2011, 90% of the salmon caught in Iceland was from angling. The annual average salmon catch is around 36.000 salmon, with the figures jumping over 80.000 in the best years. There are in total 62 salmon rivers with 354 rods allowed; the rivers in the North East are thirty, with 124 rods (2011 brochure in English; Directorate of Fisheries).

According to the Salmon and Trout Act from 2006, the fishing rights are privately owned by those who own the land adjacent to rivers and lakes. The fishing rights come with a string of obligations, supervised by the Directorate of Fisheries and most importantly: the fishing rights cannot be split from the land – the only way to control the angling is to own a farm or farms holding the angling right.

The owners of the farms owning a river or lake are obliged to set up a fishing association to manage the angling; both the necessary investment and the profit has to be shared according to the amount of land owned. The ownership is split according to voting rights and percentage owned.

Wielding control over the angling, these associations can decide either to manage the angling themselves or lease out the rights to angling clubs or other consortia.

From overfishing to highly regulated angling regime

Already in the 1970s, the fishing associations run by the farmers owning the best salmon rivers were increasingly leasing out the angling rights to groups of wealthy Icelandic anglers, mostly business men from Reykjavík.

In some rare cases, foreign anglers who frequented Iceland, held the angling rights through a lease. One attractive salmon river in the North East, Hafralónsá, where Ævar Rafn Marinósson and his family are among the owners, was leased by a Swiss angler from 1983 to 1994; from 1995 to 2003, a British and a French angler leased the river.

During the 1990s, the popularity of angling led to overfishing in many salmon rivers with tension between biology and the financial profits from the angling rights. But the owners of the angling rights quickly came to understand that overfishing would kill the goose laying the golden eggs, or rather the salmon that brought wealth to the community.

The angling is now restricted in many ways: each river has only a certain number of rods; the angling time is restricted to certain hours of the day and a certain amount of annual angling days, often 90 days, from mid-June.

In addition, some form of “fish and release” is in place in most if not all the highly sought after and expensive salmon rivers. All these protective measures have been driven by those who control the angling, i.e. the fishing associations owned by the landowners.

Foreign anglers mainly pursue the sporty fly-fishing, whereas Icelanders tend not to frown upon using spoons and worms. Icelandic anglers know it is good to fish with spoons and worms after the foreign fly-anglers have been “beating the river” as we say in Icelandic. That normally ensures great catch, a trick the Icelandic anglers are happy to use.

Angling – from farmers to wealthy business men

The leases related to the salmon rivers normally run for some years. The fees to the fishing associations are a significant part of income for the farmers. The lessees are normally obliged to undertake investment in the infrastructure around the river.

Part of cultivating the salmon population in the rivers is expanding the habitat. This is for example done by building “salmon-ladders,” enabling the salmon to migrate beyond waterfalls or other hindrances, potentially increasing the rods allowed in each river and thus making the river more profitable.

Those who rent the rivers try to sell each rod at as high a price as the market can tolerate. Angling in the best rivers in Iceland is an expensive sport, also because the fishing is sold as a package with accommodation and meals included.

No longer primitive huts, the best fishing lodges are like boutique hotels, where the best chefs in Iceland come and cook for discerning anglers with the wines to match. Part of the summer news in the Icelandic media is reporting on the number of salmon caught in the well-known rivers, size and weight, what tools were used and sometimes also who is angling where.

This is the angling of the very wealthy. But angling is also popular with thousands of ordinary Icelanders. Angling for salmon, trout and sea trout in less famous rivers and lakes, is an affordable and ubiquitous sport in Iceland.

The opaque ownership web that Ratcliffe is buying into

Incidentally, this development of buying farms, not just licensing the angling rights, has been going on in Iceland for decades. In the early 1970s, a medical doctor and keen angler in Reykjavík, Oddur Ólafsson, bought five farms along Selá. Decades and several owners later these farms are now owned by Ratcliffe.

Orri Vigfússon (1942-2017) was a businessman and passionate angler, who in 1990 set up the North Atlantic Salmon Fund as an international initiative in order to protect and support the wild North Atlantic salmon. Vigfússon was influential in Icelandic angling circles and well known in angling circles all around the North Atlantic. He was also primus motor in Strengur, a company that for decades has controlled the best rivers in the North East, now controlled by Ratcliffe.

The web of on- and offshore companies related to angling has been in the making in Iceland since the late 1990s, when the general offshorisation of wealthy Icelanders boomed through the foreign operations of the Icelandic banks. A key person in this web is an Icelandic businessman.

Born in 1949, Jóhannes Kristinsson has been living in Luxembourg for years. Media-shy in Iceland he was in business with flashy businessmen like the duo Pálmi Haraldsson and Jón Ásgeir Jóhannesson of Baugur fame, synonymous with the Icelandic boom before the 2008. Kristinsson seems to be linked to around 25 Icelandic companies.

By 2006, it was attracting media attention in Iceland that wealthy anglers were no longer just licencing the angling rights but were outright buying farms holding angling rights. One name figured more often than others, Jóhannes Kristinsson. In an interview at the time, Kristinsson said he probably owned only one farm outright but was mostly a co-owner with others, without wanting to divulge how much he owned.

The farmers felt they knew Kristinsson, a frequent guest in the North East and the opaque ownership did not seem much of an issue. However, the effect of the opacity is now becoming very clear as Kristinsson is selling to a foreigner with no ties to the community, leaving the community potentially little or no control over some of its glorious rivers and land.

Luxembourg, Ginns and Reid

Kristinsson’s ownership of lands and rivers in the North East seems to have been held in Luxembourg from early on. Dylan Holding is a Luxembourg company, registered in 2000, by BVI companies, which Kaupthing owned and used to offshorise its clients. No beneficial owner is named in any of the publicly available Dylan Holding documents but the company was set up with Icelandic króna, indicating its Icelandic ownership.

According to Dylan Holding’s 2018 annual accounts, the company, still filing accounts in Icelandic króna, held assets worth ISK2.6bn. Its 2017 accounts list eleven Icelandic holding companies, fully or majority-owned by Dylan Holding, among them Grænaþing. Last year, Ratcliffe bought Grænaþing, as part of the deal with Kristinsson; an indication of Kristinsson being the beneficial owner of Dylan Holding.

The names of two of Ratcliffe’s trusted Ineos lieutenant, Jonathan F Ginns and William Reid, are closely linked to Ratcliffe’s Icelandic ventures as to so many other Ratcliffe ventures. According to UK Companies House, Ginns sits or has been on the board of over seventy Ineos/Ratcliffe related companies, Reid on seven.

Ginns and Reid sit on the boards of three Icelandic companies previously owned by Dylan Holding indicating that these companies are now under Ratcliffe’s control. Whether Ratcliffe has bought Dylan Holding outright or where exactly his ownership stands at, remains to be seen but it seems safe to conclude that Ratcliffe now owns significantly more land on his own rather than, as earlier, through joint venture with Kristinsson and others. Kristinsson seems to be withdrawing, leaving Ratcliffe as the sole owner.

Ratcliffe’s rapid rise to being Iceland’s largest landowner

Jim Ratcliffe, the angler with the funds to indulge his salmon passion was nr.3 on the Sunday Times Rich List this year, with assets valued at £18.15bn, down from £20.05bn in 2018, when he ranked nr.1. A Brexiteer who is not waiting for Brexit to happen: after relocating to the UK from Switzerland, where Ratcliffe and Ineos were domiciled from 2010 until some months after the EU referendum in 2016, Ratcliffe moved to Monaco last year. Tax and regulation seem to be his main concerns.

Ratcliffe had been fishing in Vopnafjörður for some years without attracting any attention. It was not until late 2016, when he visibly started buying into the Icelandic angling consortia, that his name first appeared in the Icelandic media. By then, he already owned eleven farms in the area, both through sole ownership and through his share in Strengur. Local sources believe Ratcliffe started investing earlier in angling assets, hidden in opaque ownership structures.

In December 2016 it was announced that Ratcliffe had bought the major part of the single largest farmland in Iceland, Grímsstaðir. This mostly barren wasteland of glorious beauty in the highlands beyond Mývatn had been owned by Grímstaðir farmers and their families for generations. The Icelandic state was a minority owner and has retained its share of the land. Ratcliffe stated at the time he was buying Grímsstaðir because it was part of the Selá water system; buying the land was part of his plan to support and protect the wild salmon.

The Grímsstaðir deal drew a lot of media attention in Iceland because in 2011, a Chinese businessman and poet, Huang Nubo, had tried to purchase this land with unclear intentions. Nubo had some Icelandic friends from his university years but practically no assets abroad except some real estate in the US, which he seemed to struggle to maintain. In 2014, the Icelandic government vetoed Nubo’s plans: he was not European, and his plans lacked clarity.

For decades, Strengur, under changing ownership, has managed the angling rights in Selá and Hofsá, two of the best salmon rivers in the North East and bought up farms adjacent to the rivers. In 2012, a new 960sq.m fishing lodge opened by Selá, a good example of the investment done in order to improve the angling experience and cater to wealthy anglers.

Following a 2018 transaction Ratcliffe owns almost 87% of Strengur, a jump from the 34% he had owned earlier, meaning that he controls the angling rights in both Selá and Hofsá. Ratcliffe bought the 52.75% by purchasing a company owned by Jóhannes Kristinsson. Strengur’s director Gísli Ásgeirsson (who features in this Ineos PR video) is now seen as Ratcliffe’s mouthpiece. He has ties to around twenty Icelandc companies, many of which are linked to Kristinsson.

The Ratcliffe Kristinsson consortium now owns 40 to 50 farms. But Ratcliffe is looking for more: earlier this year, Ratcliffe added one farm to his Icelandic portfolio. He now seems trying to secure ownership of yet another river, Hafralónsá.

The Icelandic media had reported that he had now secured majority in the angling association of that river but that does not seem to be the case. Ævar Rafn Marinósson is one of the owners of Hafralónssá. He says to Icelog that as far as he knows, Ratcliffe is still a minority owner.

The suspicion among those who are not in Ratcliffe’s fold is rife as a change in ownership might bring about drastic changes. With majority hold, Ratcliffe might for example drive the farmers in minority to bankruptcy by forcing through investments in the Hafralónsá angling association, which would wipe out the profits that make an important part of the farmers’ annual income.

Ratcliffe’s representative made Marinósson an offer to buy his farm. His answer was that the farm, which he owns with his parents, was not for sale. The representative then visited his elderly parents with the same offer, although it had been made clear to him that the farm was not for sale.

Misinformed passion

In a PR video from Ineos, Jim Ratcliffe talks of “overfishing and ignorance” that threat the salmon populations in Iceland. In the video Ratcliffe’s passion for salmon fishing is given as his drive for investing “heavily in the region to help expand the salmon’s natural breeding grounds” through constructing of salmon ladders in six rivers. The latter part of the video is about his investment in safari parks in Africa, with both initiatives presented as rising from Ratcliffe’s environmental concerns.

As mentioned earlier, the times of overfishing in Icelandic salmon rivers are long over. To portray Ratcliffe as a saviour of the salmon rivers in the North East is at best misinformed, at worst profoundly patronising to the farmers who have lived and bred salmon all their live and whose livelihoods have partly depended on the silvery fish. But the fact that Ratcliffe has the funds to follow his passion cannot be disputed.

In August this year Ineos Technology Director Peter S. Williams signed an agreement on behalf of Ratcliffe with the Marine and Fresh Water Institute in Iceland, where Ratcliffe takes on to fund salmon research to the amount of ISK80m, around £525.000. At the time it was announced that any profit from Strengur will be ploughed into maintaining and supporting the salmon populations in the rivers that Strengur controls. Strengur’s director Gísli Ásgeirsson said at the time that the aim was sustainability in cooperation with the farmers and local councils. There will be those in the local community who feel that cooperation is exactly what is lacking.

In a Rúv tv interview I did with Ratcliffe in 2017 (unfortunately no longer available online), Ratcliffe said he was driven by his passion for angling and the uniqueness of the unspoiled nature in Iceland, a value in itself. There is some speculation in Iceland that Ratcliffe’s angling investments might be driven by something else then his passion for angling.

Some think water as commodity in a world facing water shortage is his real interest, which would explain his emphasis on buying the rivers outright instead of joint venture or just renting the angling rights. Others, that plans by Bremenport to build a port in nearby Finnafjörður in order to service the coming Transpolar Sea Route might be in Ineos’ interest. Again, total speculation but heard in Iceland. – Ineos is investing in facilities in Willhelmshaven, where Bremenport is building a new container terminal.

Mushrooming sport investment: from millions in salmon and safari to, possibly, billions in Premier League football

Ratcliffe’s UK holding company for his Icelandic assets is Halicilla Ltd, incorporated in 2015, its business being “mixed farming.” Halicilla’s 2017 accounts list two Icelandic companies as assets, Fálkaþing, incorporated in 2013 and Grenisalir, incorporated in 2016, “Icelandic companies, which in turn hold land and fishing rights.”

Ratcliffe has been unwilling to divulge how much he has invested in Iceland but that can be gleaned with some certainty from the Halicilla accounts: its assets amounted to £9.7m in 2016, which with further acquisitions in 2017, had grown to £15.3m by the end of 2017, financed directly by the shareholder, i.e. Ratcliffe.

In addition to investments in Icelandic salmon rivers, Ratcliffe’s sports investments have mushroomed in the recent years. In December 2017, he announced his investment in luxury eco-tourism project in safari parks in Tanzania through a UK company, Falkar Ltd, incorporated in 2015. As Halicilla, Falkar is financed by Ratcliffe, with a loan of £6.3m, at the end of 2017. With his interest in sailing, Ratcliffe owns two yachts, one of them, Hampshire II a superyacht worth $150m, with two of his Ineos partners owning three yacths. In addition, Ratcliffe owns four jets, three Gulfstream jets and one Dassault Falcon.

Ratcliffe’s other sport investments involve much higher figures than his investments in salmon and safari. Last year, he invested £110m in Britain’s America’s Cup team. His investment in March in the cycling Team Sky, now Team Ineos, seemed to imply that the Team’s earlier budget of £34m would increase significantly. In 2017 he bought the Lausanne-Sport football club, where his brother is now the club’s president, and has recently completed a £88.7m deal to buy Ligue 1 club Nice.

The figures might rise: last year, Ratcliffe led an unsuccessful bid of £2bn for Chelsea FC and has aired his interest to buy his favourite team, Manchester United – one day, some super-star footballers might be practicing fly-fishing under Ratcliffe’s instructions in Vopnafjörður.

Split families and farming communities, threats and bullying

The farmers in the North East face a dilemma. It is in the interest of farmers to be able to sell their farm for a reasonable price if they intend to retire or give up farming for other reasons. However, seeing whole fjords and entire rivers now owned not by a consortium of wealthy anglers in Reykjavík but by a single foreigner, wholly unrelated to the country and the North East, with a strangle hold on the community, has spread unease.

When the Icelandic consortia started buying farms in order to gain control of the angling, the farmers often continued to live on the farm, as tenants. On the whole, the farms have continued to be farmed, though there are exceptions.

Ratcliffe has stated he is keen for the farmers to keep living on the farms and has offered them to stay as tenants. With money in the bank the tenants can profit from the land as earlier but no longer benefit from the angling rights as earlier or have any say on the use of the river.

Ratcliffe’s acquisitions have completely changed the game around the rivers. The novelty is his immense buying power. His entrance into the angling circles has split families and communities. To sell or not to sell is a burning question for many since Ratcliffe’s representatives keep making lucrative offers to the few farmers who have so far been unwilling to sell.

This is, as such, not entirely Ratcliffe’s fault – he simply has an exorbitant amount of money to indulge in one of his hobbies though he has shown little interest in learning from the farmers who know the rivers like the back of their hands. But this sowing of anger and unease has been the side effect of his investments. Perhaps also to some degree because of the people he has chosen to work with in Iceland; how well informed Ratcliffe is of the circumstances surrounding his investments is unclear.

Ratcliffe flies in and out of Iceland. The Icelanders who work for him are there and some live in the communities Ratcliffe has already bought or is trying to buy. His salmon shopping spree may be backed by the best intensions, but the side effect is effectively making him the ruler of a few hundred Icelanders who live off the land they love dearly. The land, which Ratcliffe visits at his leisure, once in a while.

Restrictions on ownership of land may come too late for the North East

Foreign ownership is a hot topic in Iceland for the time being, given the quick and enormous concentration of Ratcliffe’s ownership in the North East. But it would be wrong to focus on foreign ownership – the real problem is concentrated ownership.

Ratcliffe is not the only foreign landowner in Iceland. There are a few others but there is increased interest from abroad for land in Iceland. One foreign owner closed off his land with signs of “Private road,” much to the irritation of his Icelandic neighbours since free passage in the country side is seen as a general right in Iceland. One practical reason is the gathering of sheep: sheep roam freely in summer and farmers need to roam just as freely when the sheep is gathered in autumn.

Though rapidly developing, luxury tourism is still a rarity in Iceland, and has so far not led to land being closed off. As Ratcliffe’s Tanzania investment shows, he is interested in luxury tourism. Seeing angling turning into an even more rarefied luxury than it already is, marketed mainly for people in Ratcliffe’s wealth bracket, is not an enticing thought for most Icelanders.

The government led by Katrín Jakobsdóttir, leader of the Left Green party (Vinstri Grænir), with the Independence party (Sjálfstæðisflokkur) and the Progressives (Framsóknarflokkur), is now under pressure to consider means to limit foreign ownership. A working group has been gathering material and new law is promised this coming winter. One step in the right direction of focusing on concentrated ownership, not just foreign ownership, would be to reintroduce pre-emptive purchase rights of local councils, abolished in 2004.

Finding the proper criteria that drive rural development in the right direction will not be easy. But Icelanders are certainly waiting for that to happen – having stratospherically wealthy people, Icelandic or foreign, owning entire rivers and fjords on a scale not seen since the time of the feudal lords of the Icelandic sagas is not seen as positive rural development. When law is finally passed, it might be too late to prevent that to happen in the North East.

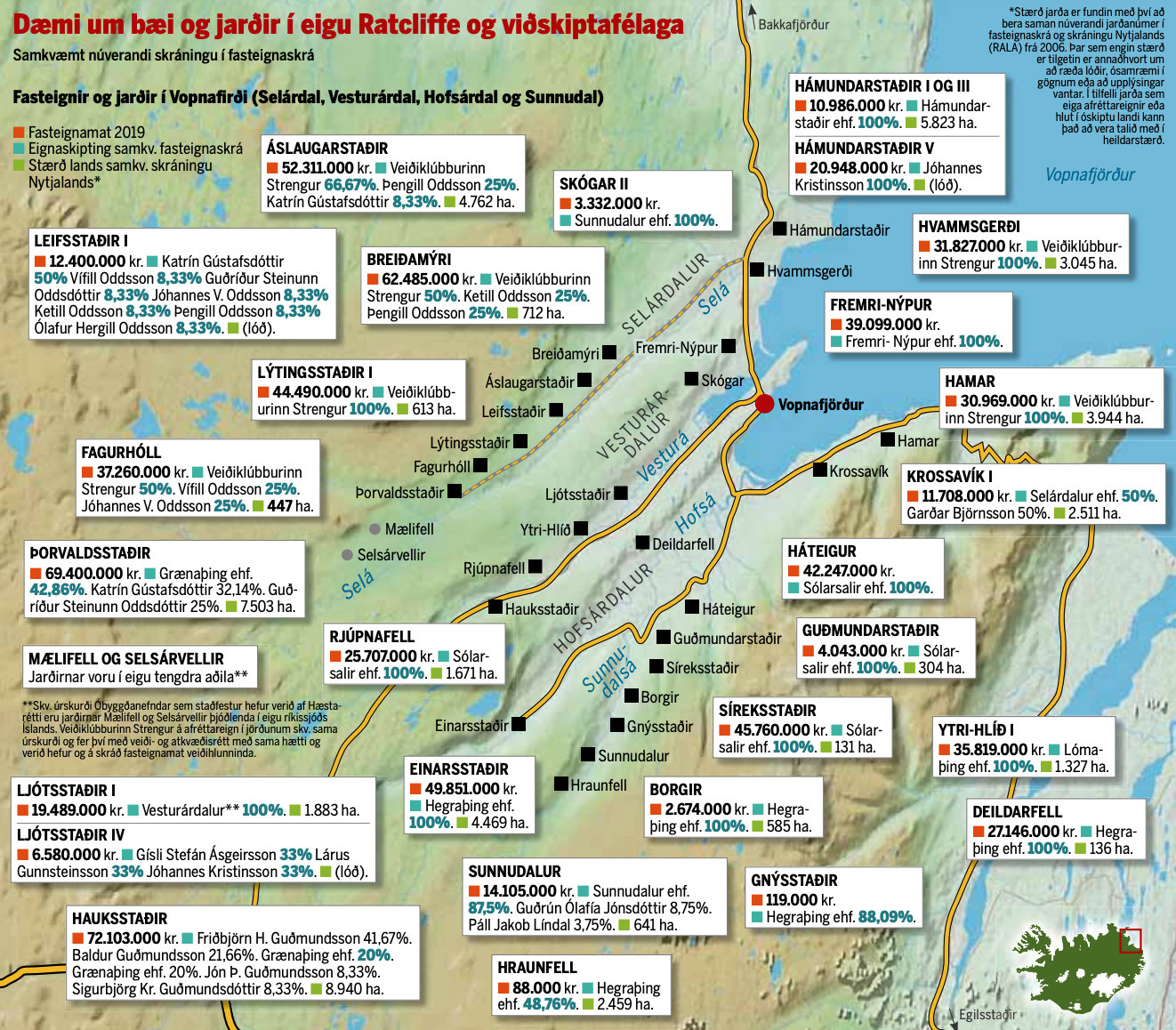

*This image is from a July 21 July 2018 article on Ratcliffe’s acquisitions in the Icelandic daily Morgunblaðið and shows ownerships of farms in Vopnafjörður (there are other farms in the neighbouring communities.)

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Kaupthing Luxembourg and Banque Havilland – risk, fraud and favoured clients

Banque Havilland has just celebrated its tenth anniversary: it is now ten years since David Rowland bought Kaupthing Luxembourg out of bankruptcy. A failed bank not only tainted by bankruptcy but severely compromised by stark warnings from the regulator, CSSF. Yet, neither the regulator nor the administrators nor later the new owner saw any reason but to keep the Kaupthing Luxembourg manager and key staff. In four criminal cases in Iceland involving Kaupthing the dirty deals were done in the bank’s Luxembourg subsidiary with back-dated documents. Two still-ongoing court cases, which Havilland is pursuing with fervour in Luxembourg, indicate threads between Kaupthing Luxembourg and Havilland, all under the nose of the CSSF.

“The journey started with a clear mission to restructure an existing bank and the ambition of the new shareholder to lay strong foundations, which an international private bank could be built on,” wrote Juho Hiltunen CEO of Banque Havilland on the occasion of Havilland’s 10th anniversary in June this year.

This cryptic description of the origin of Banque Havilland hides the fact that the ‘existing bank’ David Rowland bought was the subsidiary of Kaupthing Luxembourg, granted suspension of payment 9 October 2008, the same day that the mother-company, Kaupthing hf, defaulted in Iceland.

The last year of Kaupthing Luxembourg’s operations had been troubled by serious concerns at the Luxembourg regulator, Commission de Surveillance du Secteur Financier, CSSF, regarding the bank’s risk management and the management’s willingness to move risk from clients onto the bank.

Unperturbed by all of this, Rowland not only bought the bank but kept the key employees, including the bank’s Icelandic director, Magnús Guðmundsson, instrumental in selling Kaupthing Luxembourg to Rowland. Guðmundsson stayed in his job until 2010, when news broke in Iceland he was under investigation, later charged and found guilty in two criminal cases (two are still ongoing) in Iceland, where he has served several prison sentences. He was replaced by Jean-Francois Willems, another Kaupthing Luxembourg manager, CEO of Banque Havilland Group since 2017. Willems was followed by Peter Lang, also an earlier Kaupthing manager. Lang left that position when Banque Havilland was fined by the CSSF for breaches in money laundering procedures.

David Rowland’s reputation in his country of origin, Britain, was far from pristine – in Parliament, he has been called a ‘shady financier.’ However, all that seemed forgotten in 2010 when the media-shy tycoon was set to become treasurer of the Conservative Party, having donated in total £2.8m to the party in less than a year. As the British media revised on Rowland stories, Rowland realised he was too busy to take on the job and stepped out of the spotlight again.

In the Duchy of Luxembourg, Rowland was seen as fit and proper to own a bank. And the bank, CSSF had severely criticised, was seen as fit and proper to receive a state aid in the form of a loan of €320m in order to give the bank a second life.

Criminal investigations in Iceland showed that Kaupthing hf’s dirty deals were consistently carried out in Luxembourg. There were clearly plenty of skeletons in the Kaupthing Luxembourg that Rowland bought. Two still-ongoing legal cases connect Kaupthing and Havilland in an intriguing way.

In December 2018, the CSSF announced that Banque Havilland had been fined €4m and now had “restrictions on part of the international network” for lack of compliance regarding money laundering and terrorist financing, the regulator’s second heftiest fine of this sort. Eight days later the bank announced a new and stronger management team: a new CEO, Lars Rejding from HSBC. It was also said that there were five new members on the independent board but their names were not mentioned. An example of the bank’s rather sparse information policy.

KAUPTHING LUXEMBOURG: RISK, FRAUD AND FAVOURED CLIENTS

2007: CSSF spots serious lack of attention to risk in Kaupthing Luxembourg

On August 25 2008, the CSSF wrote to the Kaupthing Luxembourg management, following up on earlier exchanges. The letter shows that as early as in the summer of 2007, the CSSF was aware of the serious lack of attention to risk. The regulator’s next step, in late April 2008, was to ask for the bank’s credit report, based on the Q1 results, from the bank’s external auditor, KPMG. In the August 2008 letter, the CSSF identified six key issues where Kaupthing Luxembourg was at fault:

1 The CSSF deemed it unacceptable that Kaupthing Luxembourg financed the buying of Kaupthing shares “as this may represent an artificial creation of capital at group level.”

2 Analysing the bank’s loan portfolio, the CSSF concluded that the bank’s activity was more akin to investment banking than private banking as the bulk of credits were “indeed covered by highly concentrated portfolios (for example: (Robert) Tchenguiz, (Kevin) Stanford, (Jón Ásgeir) Johannesson, Grettir (holding company owned by Björgólfur Guðmundsson, Landsbanki’s largest shareholder, together whith his son, Björgólfur Thor Björgólfsson) etc.)” The CSSF saw this “as highly risky and we ask you to reduce it.” This could only continue in exceptional cases where the loans would have a clear maturity (as opposed to bullet loans that were rolled on).

3 Private banking loans should have diversified portfolio of quoted securities and be easy to liquidate, based on a formal written procedure as to how that should be done.

4 Personal guarantees from the parent company should be documented in the loan files so that the external auditor and the CSSF could verify how these exposures were collateralised in the parent bank.

5 As the CSSF had already pointed out in July 2007, the indirect concentration risk should not exceed 25% of the bank’s own funds. CSSF concluded that the bank was not complying with that requirement as the indirect risk concentration on Eimskipafélagið hf, owned by Björgólfur Guðmundsson, and on Kaupthing hf, the parent bank, was above this limit.

6 At last, CSSF stated that only quoted securities could be easily liquidated, meaning that securities illiquid in a stress scenario, could not be placed as collateral. CSSF emphasised that securities like Kaupthing hf, Exista hf and Bakkavor Group hf, could not be used as a collateral, exactly the securities that some of Kaupthing’s largest clients were most likely to place as collaterals.

It is worth keeping in mind that the regulator had been studying figures from Q1 2008; in August, when CSSF sent its letter, the Q2 figures were already available: the numbers had changed much for the worse. Unfazed, Kaupthing Luxembourg managers insisted in their answer 18 September 2008 that the regulator was wrong about essential things and they were doing their best to meet the CSSF concerns.

What the CSSF identified: the pattern of “favoured clients”

The CSSF had been crystal clear: after closely analysing the Kaupthing Luxembourg operation it did not like what it saw. Kaupthing’s way of banking, lending clients funds to buy the bank’s shares and absolving certain clients of risk and moving it onto the bank, was not to the CSSF’s liking. What the CSSF had indeed identified was a systematic pattern, explained in detail in the 2010 Icelandic SIC report.

This was the pattern of Kaupthing’s “favoured clients”: Kaupthing defined a certain group of wealthy and risk-willing clients particularly important for the bank. In addition to loans for the client’s own projects, there was an offer of extra loans to invest in Kaupthing shares, with nothing but the shares as collateral. In some cases, Kaupthing set up companies for the client for this purpose, or the bank would use companies, owned by the client, with little or no other assets. The loans were issued against Kaupthing shares, placed in the client’s company.

How this system would have evolved is impossible to say but over the few years this ran, these shareholding companies profited from Kaupthing’s handsome dividend. The loans were normally bullet loans, rolled on, where the client’s benefit was just to collect the dividend at no cost. In some cases, the dividend was partly used to pay off the loan but that was far from being the rule.

What the bank management gained from this “share parking,” was knowing where these shares were, i.e. that they would not be sold or shorted without the management’s knowledge. Kaupthing had to a large extent, directly and indirectly funded the shareholdings of the two largest shareholders, Exista and Ólafur Ólafsson. In addition to these large shareholders there were all the minor ones, funded by Kaupthing. It can be said that the Kaupthing management had de facto complete control over Kaupthing.

All the three largest Icelandic banks practiced the purchase of own shares against loans to a certain degree but only Kaupthing had sat this up as part of its loan offer to wealthy clients. In addition, Kaupthing had funded share purchase for many of its employees.* This activity effectively turned into a gigantic market manipulation machine in 2008, again especially in Kaupthing, as the share price fell but would no doubt have fallen steeper and more rapidly if Kaupthing had not orchestrated this share buying on an almost industrial scale.

The other main characteristic of Kaupthing’s service for the favoured clients was giving them loans with little or no collaterals. This also led to concentrated risk, as pointed out in para 2 and 3 in the CSSF’s letter from August 2008 and later in the SIC report. As one source said to Icelog, for the favoured clients, Kaupthing was like a money-printing machine.

Back-dated documents in Kaupthing

After the Icelandic Kaupthing failed, the Kaupthing Resolution Committee, ResCom, quickly discovered it had a particular problem to deal with. The ResCom had kept some key staff from the failed bank, thinking it would help to have people with intimate knowledge working on the resolution.

A December 23 2008 memorandum from the law firm Weil Gotschal & Manges, hired by the ResCom, pointed out an ensuing problem: lending to companies owned by Robert Tchenguiz, who for a while sat on the board of Exista, Kaupthing’s largest shareholder, had been highly irregular, according to the law firm. As the ResCom would later find out, this irregularity was by no means only related to Tchenguiz but part of the lending to favoured clients.

The law firm pointed out that some employees had been close to these clients or to their closest associates in the bank and advised that all electronic data and hard drives from Sigurður Einarsson, Hreiðar Már Sigurðsson and seven other key employees should be particularly taken care of. Also, it noted that two of those employees, working for the ResCom, should be sacked; it could not be deemed safe that they had access to the failed bank’s documents. The ResCom followed the advice but by then these employees had already had complete access to all material for almost three months.

Criminal cases against Kaupthing managers have exposed examples of back-dated documents, done after the bank failed. According to one such document, Hreiðar Már Sigurðsson was supposed to have signed a document in Reykjavík when he was indeed abroad (from the embezzlement case against HMS). There is also an example of September 2008 minutes of a Kaupthing board meeting being changed after the collapse of Kaupthing. No one has been charged specifically with falsifying documents, but these two examples are not the only examples of evident falsification.

The central role of Kaupthing Luxembourg in Kaupthing hf’s dirty deals

The fully documented stories behind the many dirty deals in Kaupthing first surfaced in April 2010 in the report by the Special Investigative Commission, SIC. Intriguingly, these deals were, almost without exception, executed in Luxembourg.

By the time the SIC published its report, the Icelandic regulator, FME, already had a fairly clear picture of what had been going on in the banks. The fraudulent activities in Kaupthing made that bank unique – and most of these activities involved fraudulent loans to the favoured clients. In January 2010, the Icelandic regulator, FME, sent a letter to the CSSF with the header “Dealings involving Kaupthing banki hf, Kaupthing Bank Luxembourg S.A., Marple Holding S.A., and Lindsor Holdings Corporation.”

Through the dealings of these two companies, Skúli Þorvaldsson profited over the last months before the bank’s collapse by around ISK8bn, at the time over €50m. These trades mainly related to Kaupthing bond trades: bonds were bought at a discount but then sold, even on the same day, at a higher price or a par. Þorvaldsson profited handsomely through these trades, which effectively tunnelled funds from Kaupthing Iceland to Þorvaldsson, via Kaupthing Luxembourg.

Þorvaldsson was already living in Luxembourg when Kaupthing set up its Luxembourg operations in the late 1990s. He quickly bonded with Magnús Guðmundsson; Icelog sources have compared their relationship to that of father and son. When the bank collapse, Þorvaldsson was Kaupthing Luxembourg’s largest individual borrower and, in September 2008, the bank’s eight largest shareholder, owning 3% of Kaupthing hf through one of his companies, Holt Investment Group. At the end of September 2008, Kaupthing’s exposure to Þorvaldsson amounted to €790m. The CSSF would have been fully familiar with the fact that Þorvaldsson’s entire shareholding was funded by Kaupthing loans.

In addition, the FME pointed out that four key Kaupthing Luxembourg employees, inter alia working on those trades, had traded in bonds, financed by Kaupthing loans, profiting personally by hundreds of thousands of euros. Intriguingly, these employees had not previously traded in Kaupthing bonds for their own account. Some of these trades took place days before Kaupthing defaulted, with the FME pointing out that in some cases the deals were back-dated.

The central role of Kaupthing Luxembourg in Kaupthing’s Icelandic criminal cases

Following the first investigations in Iceland, the Office of the Special Prosecutor, OSP, in Iceland, now the County Prosecutor, has in total brought charges in five cases against Kaupthing managers, who have been found guilty in multiple cases: the so-called al Thani case, and the Marple Holding case, connected to Skúli Þorvaldsson, who was charged in that case but found not guilty.

The third is the CLN case, the fourth case is the largest market manipulation ever brought in Iceland. The charges in the fifth case concern pure and simple embezzlement where Hreiðar Már Sigurðsson, at the time the CEO of Kaupthing Group, is charged with orchestrating Kaupthing loans to himself in summer of 2008 in order to sell Kaupthing shares so as to create fraudulent profit for himself. Three of the cases are still ongoing. The two cases, which have ended, the al Thani case and the market manipulation case resulted in heavy sentencing of Sigurðsson, Magnús Guðmundsson and Sigurður Einarsson, as well as other employees.

The first case brought was the al Thani case where Sigurðsson, Guðmundsson, Einarsson and Ólafsson were charged were misleading the market – they had all proclaimed that Sheikh Mohammed Bin Khalifa al Thani had bought shares in the bank without mentioning that the shares were bought with a loan from Kaupthing. The lending issued by the Kaupthing managers was ruled to be breach of fiduciary duty. The hidden deals in this saga were done in Kaupthing Luxembourg. Equally in the Marple case and the CLN case: the dirty deals, at the core of these cases, were done in Kaupthing Luxembourg.

Hreiðar Már Sigurðsson has been charged in all five cases; Magnús Guðmundsson in four cases and chairman of the board at the time Sigurður Einarsson in two cases. In addition, the bank’s second largest shareholder and one of Kaupthing’s largest borrowers Ólafur Ólafsson was charged and sentenced in the al Thani case.

What the CSSF has been investigating: Lindsor and the untold story of 6 October 2008

One of the few untold stories of the Icelandic banking collapse relates to Kaupthing. On 6 October 2008, the Icelandic Central Bank, CBI, issued a €500m loan to Kaupthing after the CBI governor Davíð Oddsson called the then PM Geir Haarde to get his blessing. This loan was not documented in the normal way: it is unclear where this figure of €500m came from, what its purpose was or how it was then used. As Oddsson nonchalantly confirmed on television the following day, the loan was announced by accident on the day it was issued. The loan was issued on the day the government passed the Emergency Act, in order to take over the banks and manage their default.

On the day that Kaupthing received the CBI loan, Kaupthing issued a loan of €171m to a BVI company, Lindsor Holdings Corporation, incorporated in July 2008 by Kaupthing, owned by Otris, a company owned by some of Kaupthing’s key managers. The largest transfer from Kaupthing October 6 was €225m in relation to Kaupthing Edge deposit holders, who were rapidly withdrawing funds. The second largest transfer was the Lindsor loan.

Having obtained the loan of €171m, Lindsor purchased bonds from Kaupthing entities and from Skúli Þorvaldsson, again via Marple, which seems to have profited by €67.5m from this loan alone. In its January 2010 letter to the CSSF, FME stated it “believes that the purpose of Lindsor was to create a “rubbish bin” that was used to dispose of all of the Kaupthing bonds still on the books of Kaupthing Luxembourg as the mother company, Kaupthing Iceland, was going bankrupt… Lindsor appears to FME to be a way to both reimburse favoured Kaupthing bondholders (Marple and Kaupthing Luxembourg employees) as well as remove losses from the balance sheet of Kaupthing Luxembourg. These losses were transferred to Lindsor, and entity wholly owned by Kaupthing Iceland,” at the time just about to go into default.

In addition, FME pointed out that most of the documents related to these Lindsor transactions had not been signed until December 2008 “but forged to appear as though they had been signed in September 2008. Employees in both Kaupthing Luxembourg and Kaupthing Iceland appear to have been complicit in this forgery.” – Yet another forgery story.

Intriguingly, when the OSP in Iceland decided to investigate Marple Holding, it already had a long-standing relationship with authorities in Luxembourg, having inter alia conducted multiple house searches in Luxembourg, first in 2010, with assistance from the Luxembourg authorities.

The purpose of the FME letter in January 2010 was not only to inform but to encourage the CSSF to open investigations into these trades. It took the CSSF allegedly some years until it started to investigate Lindsor. According to the Icelandic daily Morgunblaðið, the Prosecutor Office in Luxembourg now has the fully investigated case on his desk – the only thing missing is a decision if the case will be prosecuted or not.

Judging from evidence available on Lindsor in Iceland, there certainly seems a strong case to prosecute but the question remains if the investigation wins over the extreme lethargy in the Duchy of Luxembourg in investigating financial institutions.

AND SO, BANQUE HAVILLAND ROSE FROM KAUPTHING LUXEMBOURG’S COMPROMISED BOOKS

Enter the administrators

It is clear, that already in the summer of 2008, before Kaupthing Luxembourg collapsed together with the Icelandic mother company, Luxembourg authorities were fully aware that not everything in the Kaupthing Luxembourg operations had been in accordance with legal requirements and best practice.

On 9 October 2008, Kaupthing hf was put into administration in Iceland. On that same day, Kaupthing Luxembourg was granted suspension of payment for six months with the CSSF appointing administrators: Emmanuelle Caruel-Henniaux from PricewaterhouseCoopers, PWC, and the lawyer Franz Fayot. After Banque Havilland later came into being, PWC became the bank’s auditor. Its auditing fees in 2010 amounted to €422,000. In 2017, the fees had jumped to €1.3m.

Fayot was to play a visible role in the second coming of Kaupthing Luxembourg and has, as PWC, continued to do legal work for Banque Havilland. From 1997 to 2015 Fayot worked for the law firm Elvinger Hoss Prussen, EHP, another name to note; in 2015 Fayot joined the Luxembourg lawyer, Laurent Fisch, setting up FischFayot.

Contrary to the measures taken in Kaupthing Iceland, there was allegedly no visible attempt by the Kaupthing Luxembourg administrators to comparable scrutiny: Magnús Guðmundsson stayed with the bank and worked alongside the administrators with other Kaupthing employees. Their aim seems to have been to make sure that the bank, bursting with skeletons, would be sold on to someone with a certain understanding of Kaupthing’s business model.

The Kaupthing sale could only have happened with the understanding and goodwill of Luxembourg authorities: in spite of knowing of the severe issues and faulty management, the regulator seems to have left the administrators and Kaupthing staff to its own devices. Crucially, the state of Luxembourg was instrumental in giving the bank a second life, as Banque Havilland, by guaranteeing it a state aid of €320m.

JC Flowers, the Libyans and Blackfish Capital

Consequently, right from the beginning, everything was in place to enhance Kaupthing Luxembourg’s appeal for restructuring; the only thing missing was a new owner. The Luxembourg government had already outlined a rescue plan, drawing in the Belgian government, as Kaupthing Luxembourg had operated a subsidiary in Belgium where it marketed its high-interest accounts, Kaupthing Edge.

In a flurry of sales activity, the administrators contacted 40 likely buyers but the call for tender was open for everyone. The investment fund JC Flowers, which earlier had been involved with Kaupthing hf, had briefly shown interest in buying the Luxembourg subsidiary. But already by late 2008, Kaupthing Luxembourg seemed to be firmly on the path of being sold to the Libyan Investment Authority, LIA, the Libyan sovereign wealth fund, at the time firmly under the rule of the country’s leader Muammar Gaddafi.

The LIA certainly had the means to purchase the Luxembourg bank. In the end, however, two things proved an unsurmountable obstacle. The creditors rejected the Libyan plan 16 March 2009, possibly taking the reputational risk into account. And perhaps most importantly, given that the Luxembourg state wanted to enable the purchase with considerable funds, the Luxembourg authorities did in the end balk at the deal with the Libyans but only after months of negotiations.

Blackfish Capital and Jonathan Rowland’s “lieutenant”

In 2008, Michael Wright, a solicitor turned businessman, was working for Jonathan Rowland, son of David Rowland. In an ensuing court case, Wright described his role as being Jonathan’s “lieutenant” in spotting investment opportunities.

By 2013, Wright had fallen out with the Rowlands, later suing father and son in London where he lost his case in 2017. According to the judgement, Wright maintained that he had played a leading role in securing the purchase of Kaupthing Luxembourg for the Rowlands: after being introduced to Sigurður Einarsson or “Siggi” as he called him, already in late 2008, Wright brought the opportunity to purchase Kaupthing Luxembourg to the Rowlands.

The Rowlands admitted that Wright had been involved in “some discussions” with Einarsson and Kaupthing Bank representatives in early 2009 relating to “a proposed transaction concerning bonds,” which did not materialise but that the contact leading to the Rowlands acquiring Kaupthing Luxembourg came “subsequently.” The judge on the case noted that all three men were unreliable witnesses.

As late as March 2009, a deal with the LIA to purchase Kaupthing Luxembourg still seemed on track. According to Kaupthing hf Creditors’ report, updated in March 2009, the government of Luxembourg and a consortium led by the LIA had signed a memorandum of understanding with the aim of enabling Kaupthing Luxembourg to continue its operations. In order to facilitate the restoration, the governments of Luxembourg and Belgium had agreed to lend the bank €600m, enabling the bank to repay its 22,000 retail depositors.

From other sources, Icelog understands that the Rowlands were only contacted after it was clear that neither JC Flowers nor LIA would be buying Kaupthing Luxembourg. The person who contacted the Rowlands, according to Icelog sources, was indeed Magnús Guðmundsson, who had heard that father and son might be looking for a private bank to buy. By early June 2009, the Rowlands’ agreement with the administrators was in place.

Interestingly, there had apparently been some tentative interest from large Kaupthing shareholders – who nota bene had all bought Kaupthing shares with Kaupthing loans. The Guðmundsson brothers, Lýður and Ágúst, who owned Exista, Kaupthing’s largest shareholder, had allegedly been interested in joining David Rowland as minority shareholders but that did not happen. In an open letter to Hreiðar Már Sigurðsson and Magnús Guðmundsson, published in January 2019, Kevin Stanford, once close to the Kaupthing managers, claimed the two bankers did explore the possibility of buying Kaupthing together with the Guðmundsson brothers but the plan was abandoned.

Whatever the reality of these tentative plans, they show that the Kaupthing managers and the largest shareholders focused on keeping Kaupthing Luxembourg alive, caring less for other parts of the bank. That is intriguing, given the role of the Luxembourg subsidiary in Kaupthing’s dirty deals.

The €320m Luxembourg state aid for restructuring

From contemplating a loan of €600m, as the Kaupthing hf creditors had been led to believe, the final figure was a still generous €320m. Led by Luxembourg, with half of the funds provided by the Belgian government through an inter-state loan, the deal was finalised 10 June 2009. The sum of €320m was decided since €310m was deemed to cover the liquidity shortfall with €10m extra as a margin.

In December 2008, the Kaupthing Luxembourg shares had been moved to a new company, Luton Investments (now BH Holdings), set up by a BVI nominee company, Quebec Nominees Limited that Kaupthing Luxembourg had often used (and most likely owned).

Rowland took Luton Investments over in May 2009. On 10 July, Rowland increased its capital by the agreed amount of €50m, raising its capital to the agreed figure, according to the restructuring plan. Rowland also pledged to add further €25 to 75m in liquidity. The private banking activities and the deposits, at 13 March 2009 €275 to 325m, were taken over by Rowland’s Blackfish Capital, and registered as a new bank, Banque Havilland. Its starting balance was €1.3bn, €750 to 800m of which were existing commitments to the Luxembourg Central Bank, BCL.

Part of Rowland’s lot was also Kaupthing Luxembourg’s entire infrastructure, including headquarters and IT system. With Kaupthing’s staff of 100 employees, Banque Havilland had from the beginning funding, infrastructure and staff to ensure a smooth transition from the old Kaupthing Luxembourg to the new Banque Havilland.

On July 9 2009, the European Commission gave its approval of the state aid. It indicates that the Banque Havilland’s main source of income during its early years, was indeed the money coming from the Luxembourg state.

Pillar Securitisation

Banque Havilland’s €1.3bn starting balance was only around half of old Kaupthing Luxembourg’s balance sheet. The rest, €1.2bn, more or less the old bank’s lending operations, for which no buyer was found, was placed in a new company, Pillar Securitisation, in order to be sold over the coming years, to pay off the main creditors: the Luxembourg state, the Luxembourg deposit guarantee fund, AGDL, Luxembourg Deposit Guarantee Association (funded by retail banks), and Kaupthing Luxembourg’s inter-bank creditors.

Having received a banking licence, Banque Havilland came into being on July 10 2009: Luton Investments, the sole owner of Kaupthing Luxembourg, was split in two, Banque Havilland, the “living” bank and Pillar Securitisation, the “dead” bank. Crucially, Pillar was de facto not a separate unit: it had no staff but was run in-house by Banque Havilland, residing at the Banque Havilland address at 35A avenue J.F. Kennedy, formerly the premises of Kaupthing Luxembourg.

The proceeds of Pillar were vital for the recovery of creditors since asset sales of that company determine their recovery. The main creditors were the two governments that lent into the restructuring. The loan was divided into a super-senior tranche of €210m and a senior tranche of €110m, split in two to repay the two states, Luxembourg and Belgium. The same was for the AGDL, and the around €300m it covered as deposits were transferred: AGDL received bonds in return.

Having scrutinised the state loans to Kaupthing Luxembourg, the European Commission ruled that the loans amounted to state aid: after all, no commercial bank would have agreed to a non-interest loan to a bank during suspension of payment. These advantages were conferred to Blackfish Capital via the state-aided restructuring plan. However, the Commission was equally clear that this state aid was compatible with the Treaty, which does allow for a remedy caused by “serious disturbance in the economy of a Member State.”

Interestingly, the original plan was to wind Pillar down in just a few years; ten years later, that goal has still not been reached.

ROWLAND, THE BANK OWNER

What Rowland bought: CSSF’s concerns and Kaupthinking in practice

By buying a failed bank, Rowland showed he was not too bothered about reputational risk. By keeping the ex-manager of Kaupthing Luxembourg, Magnús Guðmundsson and his staff, he also showed that he was not worried about Kaupthing’s activities. True, much of that story was not public at the time. Rowland would however have heard of CSSF’s serious concern in summer of 2008, before the bank failed. Concern, related to risky loans to large shareholders and related parties, that would have leapt out of the books on due diligence.

Although the CSSF had been chasing Kaupthing for credit risk and over-exposure to large clients and shareholders, the regulator was apparently as unbothered as the administrators that the Kaupthing managers were in charge of the bank during its suspension of payment.

Not only did CSSF apparently not follow up on earlier worries but the Luxembourg state decided to facilitate the bank’s second life with loans, notably without making it a condition that the management should be changed.

In Banque Havilland’s 2010 annual accounts, COO Venetia Lean (Rowland’s daughter) and CFO Jean-Francois Willems stated in their introduction that the bank would focus on retaining clients who met “strategic requirements… Towards the end of the year the family started to introduce members of its network to the Bank and we are working on the development of co-investment products whereby clients have the opportunity to invest alongside the family.” This focus, on co-investing with the family, is no longer mentioned.

Rowland’s first foreign investments after Luxembourg: Belarus and Iceland

In November 2010, Banque Havilland embarked on its first foreign venture, in Belarus: ‘the first Belarusian foreign direct investment fund,’ apparently a short-lived joint-venture with the Russian Sberbank Group. The press release seems to have disappeared from the Havilland website.

From 2011 to 2015 Banque Havilland expanded both in Luxembourg and abroad, i.e. in Monaco, London, Moscow, Liechtenstein, Switzerland and Nassau, either by buying banks or opening offices. The expansion in Monaco, Liechtenstein and Switzerland were done inter alia by buying Banque Pasche in these three locations. In the London office it set up a partnership with 1858Ltd in order to add art consultancy to its services.

Rowland’s interest for Icelandic investments did not end with Kaupthing Luxembourg. Contrary to most other foreign investors at the time, Rowland did not seem unduly worried by capital controls in Iceland, in place since autumn 2008. In the spring of 2011, it transpired that he had bought just under 10% of shares in the Icelandic MP Bank, which he held through a family-owned company, Linley Limited, represented on the MP board by Michael Wright.

MP Bank was named after its founder Margeir Pétursson, a Grand Master in chess, who set it up in 1999. In 2005, Pétursson was interested in expanding abroad but rather than following Icelandic bankers to the neighbouring countries, he made use of his knowledge of Russian and bought Lviv Bank in Ukraine. MP Bank survived the banking collapse in 2008 but was struggling. By 2010, the bank was no longer under Pétursson’s control and he left the board. In early 2011 the bank was split in two, with Pétursson still running that part owning the bank’s foreign assets.

At the time Rowland bought shares in MP Bank the bank was being revived with new capital and new shareholders. Another new foreign shareholder, who bought a stake in MP, equal to Rowland’s, was the ex-Kaupthing client, Joe Lewis, who, with Kaupthing loan to buy shares in Kaupthing and scantily covered loans, fitted the characteristics of a favoured client.

Enic was a holding company Lewis co-owned with Daniel Levy through which they held their trophy asset, Tottenham Hotspur. Kaupthing Singer & Friedlander, KSF, Kaupthing’s UK subsidiary, had issued a loan of €121.9 million to Enic, with shares in the football club as collateral. Kaupthing deemed the club was worth €89m, which meant the loan was only party covered in addition to the collateral being highly illiquid. Yet, the rating of the collateral on Kaupthing books was ‘good’ as Kaupthing had “confidence in the informal support of the principals.” According to the loan book “Joe Lewis is reputedly extremely wealthy and a target for doing further business with.”

Kaupthing, Banque Havilland and Kvika

In 2009, the former KSF director Ármann Þorvaldsson published a book, Frozen Assets, about his Kaupthing life. In it, he tells, almost with palpable nostalgia, of sitting on Lewis’ yacht in June 2007, discussing further projects; Þorvaldsson was keen to build a stronger relationship with the man estimated to be one of the 20 richest people in the UK. What ties were being forged on the yacht is anyone’s guess.

Rowland was clearly as unworried about MP Bank’s reputation – at the time, involved in some court cases – as he had been about Kaupthing Luxembourg’s reputational risk. In 2014, MP Bank and Virðing, an Icelandic asset management company with numerous ex-Kaupthing employees, attempted to merge with MP Bank, giving rise to rumours in Iceland that a new Kaupthing was in the making. The merger floundered. In the summer of 2015, both Rowland and Lewis apparently sold their stakes to Straumur, another resurrected Icelandic investment bank. Yet, according to Linley Limited 2015 annual accounts, the MP Bank shares were written down that year and Rowland is no longer a shareholder in the bank.

After the Straumur purchase in 2015, MP Bank changed its name to Kvika. As Virðing and Kvika did indeed merge in 2017, the former director of KSF, Ármann Þorvaldsson became CEO of Kvika until he recently demoted himself by swapping places with Kvika’s deputy CEO Marínó Örn Tryggvason, another ex-Kaupthing employee, and moved to London in order to focus on Kvika London. The question is if Kaupthing’s former clients in London will be tempted to bank with Kvika. One of them has already stated to Icelog that he will not be switching to Kvika.

Out of the three largest Icelandic banks, that collapsed in October 2008, Kaupthing, or rather Kaupthing-related people, both managers and shareholders, seem to be the only ones who keep giving the idea that Kaupthing-connections are still alive and meaningful. These musings reverberate in the Icelandic media from time to time.

THE KAUPTHING SKELETONS IN BANQUE HAVILLAND

The Kaupthing – Banque Havilland link: Immo-Croissance

One link that connects old Kaupthing with Banque Havilland is the real estate company, Immo-Croissance, founded in 1988. By the time, Immo-Croissance attracted Icelandic attention, it owned two prime assets in Luxembourg, Villa Churchill and a building, set for demolition, on Boulevard Royal, where the land was the valuable asset. In 2008, Jón Ásgeir Jóhannesson, the Icelandic businessman of Baugur-fame and a long-time large borrower of Kaupthing and all other Icelandic banks, had set his eyes on Immo-Croissance.

Jóhannesson had hoovered up real estate companies here and there, most notably in Denmark, where he had been on a wild shopping spree, all merrily funded by the three Icelandic banks. Interestingly, he used Kaupthing Luxembourg for this transaction – Kaupthing put up a loan of €122m – although a consortium under Jóhannesson’s control had been the largest shareholder in Glitnir since spring 2007.

In November 2007, Immo-Croissance’s board reflected the Baugur ownership as Baugur-related directors took seat on the board, together with Kaupthing employee Jean-François Willems. Under Baugur-ownership, Immo-Croissance apparently went on a bit of a cruise through several Baugur-owned companies. In June 2008, a Baugur Group company, BG Real Estate Europe, merged with Immo-Croissance, whereby magically the €122m loan to buy Immo-Croissance landed on Immo-Croissance own books.

But as with so many purchases by the Kaupthing’s favoured clients, Baugur’s purchase depended entirely on Kaupthing’s funding. By the end of September 2008, Baugur was in dire straits and Immo-Croissance was sold, or somehow passed on to SK Lux, a company belonging to the Kaupthing Luxembourg’s largest borrower, Skúli Þorvaldsson.

According to Icelog sources in Luxembourg, familiar with the Immo-Croissance deals in 2008, the SK Lux purchase of Immo-Croissance left all the risk with Kaupthing Luxembourg, a consistent pattern in deals financed by Kaupthing for the bank’s favoured clients.

The second and third life of Immo-Croissance

A key person in the Immo-Croissance saga, as in the origin of Banque Havilland, is the lawyer Franz Fayot, Kaupthing Luxembourg’s administrator until the bank was sold in summer of 2009. It was during his time as administrator of Kaupthing Luxembourg that Immo-Croissance was put up for sale, as SK Lux defaulted when the Kaupthing loan came to maturity at the end of October 2008.

At the time, Dexia was interested in buying Immo-Croissance. Its offer was a set-off against Kaupthing debt to Dexia, in addition to a cash payment. Kaupthing Luxembourg however preferred to sell to an Italian businessman Umberto Ronsisvalle and his company, R Capital. Guðmundsson arranged the deal for Ronsisvalle through Consolium, a Luxembourg company set up by an Icelandic company, later taken over by Guðmundsson and a few other ex-Kaupthing bankers. Consolioum went through name changes, with some of the bankers’ wives later taking over the ownership as the bankers got indicted or were at risk from being indicted in Iceland.

Ronsisvalle offered €5.5m. In addition, Immo-Croissance would get a loan from Kaupthing Luxembourg of €123m to refinance the earlier loan. This time however the loan was against proper guarantees, not like the earlier loan to the Icelandic Immo-Croissance owners, where no guarantees to speak of were in place.

By the end of January 2009, Umberto Ronsisvalle was in charge of Immo-Croissance but only for some months. By early summer 2009, the Kaupthing-related directors were again in charge, amongst them Jean-François Willems.

The unexpected turn of events took place in early 2009. Ronsisvalle paid the €5.5m but asked for some payment extension since he had problems in moving funds. He had understood that Kaupthing had agreed but hours after he provided the funds, Kaupthing changed its mind: it announced the loan was in default and moved to take a legal action to seize not only Immo-Croissance but also the collaterals, getting hold of €35m. The thrust of Kaupthing’s legal action was that Ronsisvalle had tried to take over Immo-Croissance without paying for it.

Early on, a judge refuted this Kaupthing allegation, pointing out that there was both the down-payment of €5.5m and the guarantees, contrary to earlier arrangements. Ronsisvalle’s side of event is that Kaupthing manipulated a default in order to get hold of the cash and the collaterals, in addition to keeping the assets in Immo-Croissance, a saga followed by the Luxembourg Land.

Havilland, Immo-Croissance and EHP

The lawyer for Kaupthing in the Immo-Croissance case was Pierre Elvinger from the legal firm Elvinger Hoss Prussen, EHP, where Franz Fayot worked prior to taking on the administration of Kaupthing. As the case has stretched over a decade now, Pillar Securitisation replaced the old Kaupthing Luxembourg in the Immo-Croissance chain of legal cases. Franz Fayot has been a lawyer for Havilland in these cases.

In 2013, the case had reached a point where a judge had ordered Pillar to hand back Immo-Croissance to Ronsisvalle, its legal owner according to the judge. The problem was that in the meantime, Pillar had sold the company’s two most valuable assets, Villa Churchill and the building on Boulevard Royal.

In an article in Land, in July 2013, it was pointed out that Villa Churchill was sold to a company owned by three partners at EHP. The Boulevard Royal asset was sold to Banque de Luxembourg, a private bank where one EHP partner was a member of the board. In both cases, questions were raised regarding the price and a friendly deal.

EHP complained about the reporting and its comment was published in Land: EHP pointed out that Fayot ceased to be administrator as Banque Havilland and Pillar Securitisation came in to being in July 2009, whereas the two assets were sold in 2010. Also, that the price had to be agreed on by Immo-Croissance owner, Pillar Securitisation, i.e. the Pillar creditors’ committee.

What the law firm does not mention is that Fayot has stayed in business relationship with Banque Havilland, inter alia as a lawyer for Banque Havilland, for example in the Immo-Croissance cases and in a case against a Kaupthing employee whom Havilland has kept in a legal battle for over a decade.

Court cases related to this action are still ongoing but Ronsisvalle has so far won at every stage and has regained control of the company after fighting in court for years. He is now involved in a legal battle with Banque Havilland and Pillar regarding the assets sold. Since Immo-Croissance was placed in Pillar Securitisation, the outcome could in the end spell losses for the creditors of Pillar, mainly the two governments that provided the state-aid, which made Kaupthing Luxembourg an attractive and largely risk-free purchase.

The ex-Kaupthing employee hounded by Banque Havilland

On 9 October 2008, the day of Kaupthing Luxembourg’s default, the bank’s risk manager resigned. In his opinion, the bank had paid far too little attention to his warnings on exposures to the large favoured clients, with equally little notice being taken to the CSSF’s warnings on the same issues. The attitude of the bank’s management seemed to be that it could not care less.

In his resignation letter, the risk manager referred to the CSSF August letter to the Kaupthing management. In spite of the warnings, Kaupthing had, according to the risk manager, not taken any measures to diminish the risk, thus probably aggravating the bank’s situation. And by doing nothing, the bank had cast shadow over the reputation of both the bank itself and its risk professionals.

In addition, the bank had not dedicated enough resources to its risk management, leaving it both lacking in personnel and IT solutions. This had also led to the standards of risk management, as expressed in the bank’s Handbook, being wholly unachievable. All of this had become much more pressing since the bank’s liquidity position had turned dramatically for the worse after 3 October 2008.

As he had resigned by putting forth a harsh criticism of the bank, effectively making himself an internal whistle-blower, he expected to be contacted by the CSSF. When that did not happen, he did contact the regulator. It turned out that the letter had not been passed on to the CSSF and no one there was particularly interested in meeting him. After pressing his point, the risk manager did get a meeting with the CSSF, which showed remarkable little enthusiasm for his message.

The CSSF, in August 2008 so critical of the Kaupthing Luxembourg management, now seemed wholly uninterested in the bank. That is rather remarkable, given that the state of Luxembourg had risked millions of euros to revive the bank, now run by the bankers that the CSSF had earlier criticised.

Baseless accusations of hacking and theft of documents

The risk manager heard nothing further from the CSSF nor from the administrators but strangely enough he got a letter from Magnús Guðmundsson, with the Kaupthing logo as if nothing had happened. He finally brought his case to Labour Court in Luxembourg both to assert that he had had the right to resign and to get a final salary settlement with Kaupthing Luxembourg.

Although the risk manager quit Kaupthing around nine months before Banque Havilland came into being, that bank counter-sued the risk manager for hacking, theft of documents and breach of banking secrecy. Interestingly these allegations were raised in 2010, after the risk manager had been called in as a witness by the UK Serious Fraud Office and the Icelandic OSP.

The hacking and theft allegations ended with a judgment in 2015, where the risk manager won the case. The judge found that the risk manager had obtained these documents as part of his duties and could legitimately hold them as evidence in the Labour Court case. This case had delayed the Labour Court case, which then could only be brought to court by the end of 2017, a still ongoing case.

Technically, the labour case was part of the liabilities that Banque Havilland took over and litigations take time. The remarkable thing is that Banque Havilland has pursued the case without any regard for the evidence of illegalities taking place in Kaupthing as well as not paying consideration to the fact that the CSSF had severely criticised Kaupthing’s management.

After all the risk manager had quit Kauthing as he felt he could no longer work with the management the CSSF had found to be failing. Using the courts to harass people is a common tactic, used to the fullest in this case. Havilland has pursued the case forcefully, which is why the case is still doing the rounds in the various courts of Luxembourg thus undermining the risk manager both financially and in terms of his professional reputation.

If a Banque Havilland employee has ever contemplated criticising the bank or in any way bringing up anything about the bank, this case shows how the Havilland owners might react. It is not certain that the attitude of Luxembourg authorities regarding whistle-blowers rhyme with European legislation.

Luxembourg, the rotten heart of financial Europe

The ongoing legal wrangling with the risk manager and the Immo-Croissance are two stories that embody the strong and long-lived ties between Kaupthing Luxembourg and Banque Havilland. Both Franz Fayot and Pierre Elvinger from EHP, the company that still resides in Villa Churchill bought out of Immo-Croissance, have represented Banque Havilland in court.

Quite remarkably, the CSSF lost all interest in Kaupthing Luxembourg, after the bank failed. Instead, it chose to lend funds to its new owners, who had less than a stellar reputation. Owners, who kept the Kaupthing management, that had given rise to the CSSF’s earlier concerns.

In addition, after knowing full well what had gone on in Kaupthing Luxembourg and being fully informed about the criminal cases in Iceland, the Luxembourg Prosecutor, now seems to be dithering as to bringing a case related to Lindsor Holding, not to mention other cases that were never investigated.

This is the state of affairs in Luxembourg, still the rotten heart of financial Europe.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.