Search Results

The two Al Thani cases, Qatari investors and Western banks

At the height of the banking crisis in 2008, Qatari investors stepped in to invest in two European banks – Barclays and Kaupthing. Later, these investments were and are the focus of criminal charges, not against the investors but the bankers, who orchestrated the investments. Both cases show that the Qatari investors were intent on profiting not only from the investments but also from hidden fees and sham arrangements. “A sham agreement requires two parties;” if the defendants were dishonest, so were the other party, the Qatari investors,” said Justice Jay during the Barclays trial recently. – This is not only relevant in connection to stories from 2008 but raises impertinent questions regarding Qatari investments in Deutsche Bank and other banks.

In autumn 2008, many Western banks were forced to seek emergency loans from governments. Three banks – Barclays, Deutsche Bank and Credit Suisse – were boastful of the fact that they did not need government funding. As has now become abundantly clear, all three tapped heavily into US measures to save US banks and foreign banks operating in the US. Even more to brag about was the fact that Barclays and Credit Suisse were able to raise funds in the market: Qatari investors were crucial in saving the two banks. Admittedly investment at a high price but these were singularly difficult times.

The Barclays investors were two Royal Qataris. Sheikh Hamad bin Jassim bin Jabr Al Thani, at the time Qatari’s prime minister, also known by his initials, HBJ. In 2013, The Independent dubbed him “the man who bought London” where he has invested both through his private companies and Qatar Investment Authority, QIA. His co-investor was Sheikh Mohammed Bin Khalifa Al Thani who in 2008 also invested in Kaupthing. Barclays paid them £66m for bringing along Sheikh Mansour Bin Zayed al Nahyan, well known in the UK for high octane investments such as Manchester City Football Club, another 2008 investment of his.

The Barclays Qatar story took a different turn in 2012 when the Serious Fraud Office, SFO, opened a criminal investigation into the Barclays deal with the Qataris: the price for the investment was even higher than previously disclosed as Barclays had kept quiet about two “Advisory Services Agreements.” On the basis of these agreements, Barclays paid the Qatari investors and Sheikh Mansour £322m; allegedly, no advice was given. The four Barclays bankers – Barclays CEO at-the-time John Varley and then-senior executives Roger Jenkins, Richard Boath and Tom Kalaris – who orchestrated the payments are now fighting criminal charges in court. Intriguingly, charges against Barclays PLC concerning a loan of $3bn to the Qatari investors were dismissed last year by the High Court.

In Iceland, the Special Prosecutors has exposed another Qatari investment saga, at the core of a criminal case against three Kaupthing bankers and the bank’s second largest investor. It turned out that a Qatari investment in Kaupthing in September 2008 was entirely funded by Kaupthing. Sheikh Khalifa was not charged but charges brought against three Kaupthing bankers and Ólafur Ólafsson, the second largest shareholder at the time, all of them sentenced to lengthy prison sentences.

Now, to the plights of Deutsche Bank. It survived 2008, much thanks to US funding but in 2014 Deutsche Bank was lacking capital; luckily, Sheikh Hamad bin Jassim bin Jabr Al Thani and Sheikh Mohammed Bin Khalifa Al Thani started investing in the bank, eventually becoming the bank’s largest investors. Now, as the German government hopes that a merger between two weak banks, Deutsche Bank and Commerzbank, might (contrary to evidence and experience) make a strong bank, the Qatari investors have indicated they might be ready to invest further.

Intriguingly, two criminal cases regarding Qatari investments show hidden deals the banks did with the Qataris to meet their demands for benefits beyond what investors could normally expect. The question is if these hidden favours were only relevant for these two cases – or if they are general indications of Qatari investors’ preferences in doing deals. If so, it raises questions regarding other Qatari investments in European banks.

Kaupthing and the Qatari investment in September 2008

After a tsunami of bad news in 2008, the one good news for Kaupthing came in September, miraculously a week after the collapse of Lehman Brothers: Sheikh Mohammed Bin Khalifa Al Thani, of the Qatari ruling family, had privately invested in Kaupthing. The investment amounted to 5.01%, just above the 5% threshold that triggered a notification to the Icelandic stock exchange, securing media attention. This investment made the Sheikh Kaupthing’s third largest investor and the only major foreign investor.

In a statement, the Sheikh claimed he had followed Kaupthing closely for some time and was satisfied of its performance and good management team. Chairman of Kaupthing Sigurður Einarsson said at the time that the bank’s strategy to diversify the shareholder base was paying off. To Icelandic media Kaupthing’s CEO Hreiðar Már Sigurðsson said this showed investors had faith in the bank.

But this investment was not enough to save the bank: in the second week of October 2008, Kaupthing collapsed, together with 90% of the Icelandic financial system.

The Kaupthing undisclosed loan and fees behind the Qatari investment

Only months later, rumours were circulating that the Qatari investment in Kaupthing had not been quite what it seemed to be. In April 2010, when the Icelandic Special Investigative Commission, SIC, published its report one of its many colourful stories recounted the reality behind this Qatari investment in Kaupthing: it had been entirely funded by Kaupthing and Sheikh Mohammed Bin Khalifa Al Thani had apparently only lent his name to this Kaupthing PR stunt. The go-between was Ólafur Ólafsson, Kaupthing’s second largest investor.

The mechanism was that Kaupthing lent funds to an Icelandic company owned by the Sheikh. In addition, Kaupthing issued a loan of $50m, labelled as advance profit, to another company owned by the Sheikh. The three Kaupthing bankers involved in the transaction – Hreiðar Már Sigurðsson, Sigurður Einarsson and Kaupthing Luxembourg’s director Magnús Guðmundsson – and also Ólafur Ólafsson were charged for breach of fiduciary duty and market manipulation and sentenced to between three and five and half years in prison (further on Icelog on the Icelandic al Thani case). Although the case was called “the Al Thani case,” the Sheikh was not charged with any wrongdoing.

Kaupthing had further plans of joint ventures with the Sheikh. In summer 2008 there had been an announcement, duly noted in the Icelandic media, that the Sheikh was investing in Alfesca, owned by Ólafsson. According to the SIC report, also here the plan was that Kaupthing would finance Sheikh Al Thani’s Alfesca investment.

In August and September 2008 Kaupthing, advise by Deutsche Bank, financed credit linked notes, CLN, transactions linked to Kaupthing’s credit default swaps, CDS, in order to influence, or rather manipulate, the CDS spreads. Two rounds of transactions were carried out: first via companies owned by a group of Kaupthing clients, then on behalf of Ólafur Ólafsson. A third round was planned, via a company owned by Sheikh Mohammed Bin Khalifa Al Thani, mimicking the earlier transactions, again with Deutsche Bank. Neither the Sheikh’s involvement with Alfesca nor the CDS trades happen as Kaupthing had run out of time and money (further on the CDS saga, see Icelog).

Barclays and Qatari investors in June and October 2008

Kaupthing was a small fry in the financial ocean, Barclays a much bigger fish. Already in spring of 2008, funding worries at Barclays were rising – the share price was falling, market conditions worsening. As Marcus Agius, Barclays chairman of the Barclays’ board 2006 to 2012, recently a witness for the prosecution in the criminal case against the four Barclays bankers, explained in court 19 February 2019, Barclays wanted to be ahead of the market, i.e. adequately capitalised: in the summer of 2008 it was time to raise capital, in fierce competition with other banks.

Consequently, Barclays decided to raise capital and underwriting was arranged. As summerised in Barclays 2008 Annual Report: On 22nd July 2008, Barclays PLC raised approximately £3,969m (before issue costs) through the issue of 1,407.4 million new ordinary shares at £2.82 per share in a placing to Qatar Investment Authority, Challenger Universal Limited (a company representing the beneficial interests of His Excellency Sheikh Hamad Bin Jassim Bin Jabr Al-Thani, the Chairman of Qatar Holding LLC, and his family), China Development Bank, Temasek Holdings (Private) Limited and certain leading institutional shareholders and other investors, which shares were available for clawback in full by means of an open offer to existing shareholders. Valid applications under the open offer were received from qualifying shareholders in respect of approximately 267 million new ordinary shares in aggregate, representing 19.0 per cent. of the shares offered pursuant to the open offer. Accordingly, the remaining 1,140.3 million shares were allocated to the various investors with whom they had been conditionally placed.

The Qatari investors were new to Barclays. At the time, Barclays’ top management saw it as highly beneficial for the bank to attract major investors from the Middle East, according to Agius. Keen to expand, the bank aimed at being a global player. The Qatari connection fitted the bank’s vision of its goal in the international world of finance.

The second round in autumn 2008 – the “tart” and the Sheikh

In autumn 2008, market conditions went from worrying to worse than anyone had thought possible, according to Agius’ witness statement in court. There were only two options: accept state funding or try another capital raising. Barclays hoped to again raise capital from the Qataris.

This time, the Qataris brought another Middle Eastern investor to the table, Sheikh Mansour Bin Zayed al Nahyan. Interestingly, there was some confusion if an Abu Dhabi public body was investing or if Sheikh Mansour was investing privately as Barclays publicly stated to begin with. In the end, the investor turned out to be International Petroleum Company where Sheikh Mansour was a chairman.

The Abu Dhabi investment saga is an even more colourful financial thriller than the Qatari saga. An independent financier Amanda Staveley advised Sheikh Mansour and got at least 30m of the £110m Sheikh Mansour allegedly got in fees from Barclays. In addition, Staveley’s company has sued Barclays for fees of £720m plus interests and cost, potentially well over £1bn,in relations to Sheikh Mansour’s investment. Her case is on hold until the criminal case against the Barclays four is brought to an end.

Somewhat ungracefully, the Barclays bankers referred to Staveley as a “tart” in a telephone recording played at the Southwark County Court recently during the Barclays trial. Intriguingly, this name-calling came from one of the charged bankers, Roger Jenkins, who argued for £25m bonus for 2008 as he had been instrumental in bringing in the Sheikhs, rather belittling Staveley’s part in it.

Barclays’ cash call of £6.1bn in times of panic

There was panic in the autumn air of 2008. Barclays fought to raise capital in order to avoid making use of the 8 October 2008 banking package, in total a staggering £500bn on offer from the government; for comparison, the total government annual spending was 618bn. One condition: participating banks would have to sign up to an agreement with the FSA on executive pay and dividend, making it rather unappealing for the well-paid Barclays bankers.

After some hesitation from the Gulf investors – they allegedly left the negotiations but returned – the bank could finally put out an innocuous statement on 31 October 2008 that Barclays had “held discussions in recent days with Qatar Holding LLC and entities representing the beneficial interests of HH Sheikh Mansour Bin Zayed Al Nahyan (“the Investors”) who agreed … to invest substantial funds into Barclays.”

As summerised in Barclays 2008 Annual Report, Barclays would issue “£4,050m of 9.75% Mandatorily Convertible Notes (MCNs) maturing on 30th September 2009 to Qatar Holding LLC, Challenger Universal Limited and entities representing the beneficial interests of HH Sheikh Mansour Bin Zayed Al Nahyan … and existing institutional shareholders and other institutional investors. If not converted at the holders’ option beforehand, these instruments mandatorily convert to ordinary shares of Barclays PLC on 30th June 2009. The conversion price is £1.53276 and, after taking into account MCNs that were converted on or before 31st December 2008, will result in the issue of 2,642 million new ordinary shares.”

Further, Barclays issued warrants on 31 October 2008 “in conjunction with a simultaneous issue of Reserve Capital Instruments [RCI] issued by Barclays Bank PLC … to subscribe for up to 1,516.9 million new ordinary shares at a price of £1.97775 to Qatar Holding LLC and HH Sheikh Mansour Bin Zayed Al Nahyan. The warrants may be exercised at any time up to close of business on 31st October 2013.” – Qatar Holding now held 6.4% of Barclays shares.

Expensive and unpopular funding

Fund raising in these tumultuous times, as banks were scurrying for government money, might have looked like quite a feat. But the reception to Barclays fundraising was disappointing: the news came as a surprise to the market and existing shareholders were dismayed; also because the fund raising had not been a normal process, Agius said in court.

Reaching the agreement with the Sheikhs had been tough. In an email to Roger Jenkins John Varley said the Qataris and Sheikh Mansour had had “too good a deal.” It did in fact prove difficult to get shareholders to agree; many of the smaller shareholders were very upset.

At least one large shareholder in Barclays voiced concern publicly: though at the time not knowing how high the cost was indeed for Barclays, the pension fund Scottish Widows claimed the capital raising had been driven through at a high cost, just to avoid state ownership and its effect on bonuses. However, by the end of November Barclays shareholders had agreed to the capital raising.

In his foreword to the Barclays 2008 Annual Report, Agius acknowledged the anger the capital raising had caused among shareholders: “…we also recognised that some of our shareholders were unhappy about some aspects of the November capital raising. This unhappiness is a matter of great regret to us.” Further, Agius set out to explain the process and the great care taken by the board to make these difficult decisions “…as we sought to react to the circumstances prevailing at the time. The Board regrets, however, that the capital raising denied Barclays existing shareholders their full rights of pre-emption and that our private shareholders were not able to participate in the raising.”

It was indeed an expensive undertaking: the official terms seemed quite generous, 2% on the RCIs, 4% on the MCNs, as Agius pointed out in court. The RCIs carried interests of 14% until June this year, 2019, (see 2008 Annual Report p.228) when the rate would be 13.4% on top of three months LIBOR. The initial coupon was deemed to carry a cost of 10% after tax for Barclays. In addition, there was a disclosed fee of £66m to the Qatari investors, for having introduced Sheikh Mansour.

The undisclosed fees of £322m for the Sheikhs – and a Barclays loan to the investors

What Agius and others at the bank say they did not know was that the cost of extracting investment from the Qatari and Abu Dhabi Sheikhs were even higher than disclosed. The four Barclays bankers agreed to fees totalling £322m, to be paid over 60 months, hidden in two so-called “Advisory Services Agreements,” ASAs, now the focus of the SFO case against the Barclays four.

What transpires from the Barclays court case is that the three Sheikhs wanted fees for investing; the original figure floated was £600m. It was not trivial to dress up the agreed fee as anything remotely acceptable: after all, these three investors were getting fees no other investors were offered. When the “Advisory Services Agreements” surfaced in communication between the Barclays bankers and the Qataris negotiating on behalf of the Middle Eastern investors as a way for Barclays to pay the companies investing, it turned out that Sheikh Hamad bin Jassim bin Jabr Al Thani also wanted fees for his personal investment.

The bankers saw the absurdity in an ASA with a prime minister: he could not be an adviser to Barclays any more than a US president could be an adviser to JP Morgan! The solution was to increase the total payment for the ASAs to QIA: there would probably be some means to get the extra funds from QIA to its chairman, Sheikh Hamad bin Jassim bin Jabr Al Thani.

The thrust of the criminal case against the four Barclays bankers is if the fees were paid for real service, if any services were given in return for the exorbitant fees. So far, witnesses have not been aware of any services given; indeed, Agius and other witnesses were not aware of the ASAs until some years later, when the they surfaced in relation to the SFO investigation.

It is also known that the Qatari investors got a loan of $3bn from Barclays at the time, which is interesting given the Kaupthing story. This information surfaced in SFO charges against Barclays bank itself; this case was however dismissed in May 2018 by the Crown Court; in October 2018 the High Court ruled against SFO’s application to reinstate the case.

Deutsche Bank – another big bank at the mercy of Qatari investors

Deutsche Bank survived the 2008 crisis through the open funding route in the US. As Adam Tooze points out: In Europe, the bullish CEOs of Deutsche Bank and Barclays claimed exceptional status because they avoided taking aid from their national governments. What the Fed data reveal is the hollowness of those boasts.” Fed records show “the liquidity support provided to a bank like Barclays on a daily basis, revealing a first hump of Fed Borrowing during the Bear Stearns crisis and a second in the aftermath of Lehman (p.218).”

As time passed, the German bank behemoth, weighed down by falling share prices inter alia caused by scandals and fines for financial misdemeanour and sheer criminal acts in various countries, struggled to stay above required capital ratio. Already in 2014, there were news of Qatari investments in Deutsche Bank according to Der Spiegel: the deal in 2014 had been arranged by the then CEO of Deutsche, Anshu Jain. Of course, Jain knew Sheikh Hamas bin Jassim Bin Jabr Al Thani, one of the wealthiest and most influential men in the Gulf. The Sheikh had long been a valued Deutsche customer, even before the 2014 investment of €1.75bn in Deutsche made him one of the larger shareholders in Deutsche.

In autumn 2016, more was needed. Again, the Sheikh was ready to invest, this time with Sheikh Hamad Bin Khalifa Al Thani, the Kaupthing investor. The two surpassed BlackRock as Deutsche’s largest shareholders, via two investment vehicles, the BVI-registered Paramount Services Holdings Ltd and Supreme Universal Holdings Ltd., registered in the Cayman Islands, respectively owned by Sheikh Jassim and Sheikh Khalifa.

With the Kaupthing saga in mind, I sent some questions to Deutsche Bank in August 2016, asking if Deutsche knew how the Qatari shareholders had financed their investment in the bank, if Deutsche could guarantee that the bank was not lending the Qatari shareholders, or anyone related to them, the invested funds, entirely or partly, and if the Qataris were getting in dividend in advance or other benefits that might later arise from their investments.

On 25 August 2016, Deutsche’s spokesman Ronald Weichert gave the following answer:

Special agreements with individual shareholders would be a breach of the stock corporation act. We want to point out, that allegations or the mere assumption that the Supervisory Board or the Management Board could enter into such an agreement or could have entered into such agreement, are absolutely unfounded and is highly defamatory. There is absolutely no indication to justify such a reporting or any allegation of this kind.

In addition to the Icelandic Al Thani case, I pointed out that Deutsche had quite some track record in being fined or scrutinized for various illegal activities, which made the tone in the answer somewhat surprising and a tad misplaced.

In addition, I mentioned that the Qatari shares purchase in Deutsche Bank, at a crucial time for the bank, had intriguingly, been just high enough to be flagged (as with the Al Thani Kaupthing investment); exactly this fact had caused attention in the media in various countries, an interest reflected in my question. I was merely trying to understand the situation, based on what had transpired in Kaupthing and Barclays with Qatari investors.

Qatari networks in European banks, with a Chinese hint

As Der Spiegel pointed out, there have long been rumours about the origin of the fortune of Sheikh Hamas bin Jassim Bin Jabr Al Thani “some of which don’t cast a particularly flattering light on the sheikh…” He himself has mentioned that his wealth, “like that of all Qataris, may be questionable from a Western point of view. But according to Qatari standards, it was legitimate and had been obtained through legitimate business.” – And, as Der Spiegel noted, the Sheikh had a predilection for investing in the financial sector.

When the long-troubled Dexia sold Banque International a Luxembourg, BIL, in 2011, the Sheikh bought 90% of the shares via a Luxembourg company, Precision Capital, for €750m, with the remaining 10% going to the Luxembourg government, indirectly giving the bank a touch of state guarantee. BIL has offices in Switzerland, the Middle East and in Denmark, since 2000, and Sweden since 2016. In 2017, Precision Capital sold its holdings in BIL for €1.6bn, more than double the purchase price less than six years earlier.

The buyer was Legend Holdings, a Chinese investment fund with roots in the technology industry, best known as the owner of Lenovo Group. The Chinese fund enthusiastically touted its BIL acquisition as a new Chinese European co-operation and the fund’s gateway into Europe.

BIL is well connected in tiny Luxembourg: the chairman of the board is Luc Frieden, former minister for various ministries in Jean-Claude Juncker’s governments, last minister of finance 2009 to December 2013 when both Juncker, now president of the European Commission since 2014 and Frieden left Luxembourg politics. After politics, Frieden joined Deutsche Bank as vice chairman in 2014. Based in London, he advised the bank on international and European matters, as well as being chairman of Deutsche’s supervisory board in Luxembourg, until he joined BIL’s Board in early 2016, a post he kept after Legend Holdings became the bank’s largest shareholder.

In 2012, Precision Capital also bought a Luxembourg banking group, KBL European Private Bankers, which owns seven small banks and asset managing firms spread over Europe. One of them is Merck Finck, with sixteen offices in Germany.

Legend Holdings purchase of BIL coincided with other Chinese companies buying into European banks. Fosun is now the largest shareholder in Portugal’s largest listed bank, Millennium BCP, holding 24% of its shares.

Most noticeable was however HNA Group interest in Deutsche Bank.The HNA Group, formerly Hanan Airlines, holds €83bn in global assets, mainly in hotels and airlines. HNA Group is not state-owned but its chairman, Chen Feng, is a member of the National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party. In 2017 HNA Group had suddenly become Deutsche’s largest shareholder, peaking with a shareholding of just under 10%. HNA Group announced in September 2018 it would sell its stake of 7.6% over the coming 18 months; it is no longer among the largest shareholders in Deutsche.

The Chinese interest in European banks has been a cause for concern and controversy, both in terms of political ties to Chinese authorities and in terms of management issues.

Deutsche Bank – more is needed, again the Qataris stand ready to invest

The 2014 purchase of Deutsche Bank shares was at the time seen as Sheikh Hamas bin Jassim Bin Jabr Al Thani’s most important strategic investment so far in European banks. In 2016, there had been rumours that the Qataris aimed at owning anything up to 25% of shares in Deutsche and were interested in exerting greater influence on the bank, which was not run to their taste. However, no such drastic steps were taken though the Sheikh showed support for Deutsche’s chairman, Paul Achleitner who faced criticism after the bank’s shares lost 50% of their value in early 2016.

The position of the largest shareholder in Deutsche has been wandering between a few firms. BlackRock had long been the largest shareholder until the investment by two Qatari-owned companies. In May 2017, the order changed as Deutsche raised capital. Although the two Qatari companies had been rumoured to be willing to increase their shareholding, they did not. Not then.

This was when the Chinese HNA Group replaced the two Qatar companies as the largest shareholder, holding just under 10%, a stake worth approximately €3,4bn. Shortly after the investment in Deutsche Bank, Hanan Group’s chairman Chen Feng visited Doha and met with Qatar dignitaries.

Now, BlackRock is again Deutsche’s largest single shareholder with 4.88%. However, the two Qatari companies, Paramount Services Holdings and Supreme Universal Holdings, each hold respectively exactly 3.05% and should for all practical purposes be seen as operating together, again making them the largest shareholder with 6.10%.

For years, Deutsche insiders have been searching for a turn-around plan for the bank without a clear success. Deutsche is now at a critical point: the echelons of power in Deutsche and the German government have come to the conclusion that the problem of two weak large banks – Deutsche and Commerzbank – will best be solved by merging them.

Again, Deutsche is in need of capital. It now seems that the public Qatar entity, QIA, stands ready to invest in Deutsche. A strategic investment as Qatar’s deputy prime minister and minister of foreign affairs Sheikh Mohammed bin Abdulrahman Al Thani, also chairman of QIA, has stated that Qatar is interested in further investments in Germany.

Recently, Deutsche reluctantly disclosed a hidden loss of $1.6bn, stemming from municipal bond-investment from a run-up to the 2008 crisis, which does little to strengthen the bank’s position prior to the merger with Commerzbank. – And then there is the latest scandal: Deutsche’s involvement in Danske Bank’s laundering of €230bn through its Estonian branch. In the end, Deutsche might be not only need capital but also moral vision, which might not necessarily come with Qatari funds.

Credit Suisse and the Qataris

The Qatari investment in Credit Suisse in 2008 was definitely a turning point for the bank and saved it from needing a state bailout. Though Qatar Holding has lowered its shareholding in the bank, it is still the largest shareholder with 5.21%, followed by Harris Associates, Norges Bank, the Olayan Group, owned by a Saudi family investing in the West since the 1950s and BlackRock.

The investment in Credit Suisse 2008 did not come cheaply for the bank: as in Barclays, the investment was more complicated than just buying shares. It was designed as convertible bonds in Credit Suisse, with a coupon of between 9 and 9.5%. This means that while regular shareholders have seen meagre dividends, Qatar Holding collects CHF380m each year from Credit Suisse.

Until February 2017, an Al Thani of the younger generation, Sheikh Jassim bin Hamad Al Thani, son of Sheikh Mohammed Bin Khalifa Al Thani, was on the board. When the young Sheikh stepped down, apparently without explanation, he was not replaced by another Qatari. His departure did not make much difference on the board except there would be fewer cigarette breaks without him.

At the time, there were speculations that Qatar Holding would be selling its stake in the bank, that Credit Suisse might be cutting the ties to the Qataris and would possibly use the opportunity to replace the convertible bonds with less expensive options as they came callable in 2018.

The bank did indeed do that at first opportunity, October 23 2018. In order to cut funding cost, it bought back around CHF5.9bn of debt issued after the financial crisis to QIA and the Olayan family; Qatar held just over CHF4bn, Olayan Group the rest, both being entitled to 9.5% on the securities.

The Qatar shareholding in Credit Suisse briefly dipped below 5% last year but then rose again to the present 5.21%. Some changes were made to the board in February 2019 but it is as if the Qataris have lost interest in the bank: in spite of being the largest shareholder they have not had a representative on the board since 2917.

Who learns what from whom?

“A sham agreement is one that does not mean what it says,” said Justice Jay to the jury recently at the trial against the four Barclays bankers. “It requires two parties. The counterparty to the [advisory services agreements] was a Qatari entity. The logic of the prosecution case that these defendants were dishonest must be that one or more individuals comprising or connected with the Qatari entity was equally dishonest in the criminal sense. There’s no getting around that.”

There was a sham agreement with Qatari investors at the core of the Icelandic criminal case against the three Kaupthing bankers and the bank’s second largest shareholder parallel to the sham agreement with Qatari investors at the core of the Barclays case.

It is not surprising to hear of corrupt business practices in the Middle East – it is known as a thoroughly corrupt part of the world with fabulously wealthy rulers where neither democracy nor transparency is a priority. As can be seen from the billions of pounds, dollars and euros, paid in fines by systemically important Western banks in less than a decade, partly for criminal activity, these banks do not have the highest of moral standards either.

The belief, perhaps a naïve one, was that when businessmen from corrupt parts of the world would do business with Western banks they would have to adhere to Western standards. Apart from the moral standards in Western banks clearly being shockingly low in too many cases, it seems that bankers at Barclays – and Kaupthing – were ready to meet the Middle Eastern investors at the level set by the investors. The question is how other banks have met the requests for the special treatment Middle Eastern investors seem prone to demand.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

The Icelandic al Thani case and the British al Thani / Barclays case

Prosecuting big banks and senior bankers is hard for many reasons: they hire big name lawyers that fight tooth and nail, with delays, deviations and imaginable and unimaginable obstructions of all sorts. PR firms are hired to deviate and create smoke and mirrors. And some journalists seem easily to identify with the pillars of financial society, even talking about “victimless crime.” All of this springs to mind regarding the SFO charges against John Varley former CEO of Barclays and three senior managers – where an Icelandic parallel can possibly throw some light on the few facts in the case of Varley e.al.

In the summer of 2008, as liquidity was tight for many banks, two high-flying banks in the London business community, Barclays and Kaupthing, were struggling. Both sought salvation from Qatari investors. Not the same investors though the name al Thani, a ruling clan in the dessert state of Qatar, figures in both investment stories.

In 2012 as the Icelandic Office of the Special Prosecutor, OSP, brought charges against three Kaupthing managers and the bank’s second largest investor Ólafur Ólafsson, related to Qatari investment in Kaupthing in September 2008, the British Serious Fraud Office, SFO, was just about to start an investigation into the 2008 Qatari investment in Barclays.

In 2015 the four Icelanders were sentenced to 4 to 5 1/2 years in prison for fraudulent lending and market manipulation (see my overview here). SFO is now bringing ex CEO John Varley and three senior Barclays bankers to court on July 3 on the basis of similar charges. As the first UK bankers are charged for actions during the 2008 crisis such investigations are coming to a close in Iceland where almost 30 bankers and others have been sentenced since 2011 in crisis-related cases.

The Kaupthing charges in 2012 filled fourteen pages, explaining the alleged criminal deeds. That is sadly not the case with the SFO Barclays charges: only the alleged offences are made public. Given the similarities of the two cases it is however tempting to use the Icelandic case to throw some light on the British case.

SFO is scarred after earlier mishaps. But is the SFO investigation perhaps just a complete misunderstanding and a “victimless crime” as BBC business editor Simon Jack alleges? That is certainly what the charged bankers would like us to believe but in cases of financial assistance and market manipulation, everyone acting in the financial market is the victim.

These crimes wholly undermine the level playing field regulators strive to create. Do we want to live in a society where it is acceptable to commit a crime if it saves a certain amount of taxpayers’ money but ends up destroying the market supposedly a foundation of our economy?

The Barclays and Kaupthing charges – basically the same

When the Icelandic state prosecutor brings charges the underlying writ can be made public three days later. The writ carefully explains the alleged criminal deeds, quoting evidence that underpins the charges. Thus, Icelanders knew from 2012 the underlying deeds in the Icelandic case, called the al Thani case after the investor Sheikh Mohammed bin Khalifa al Thani who was not charged.

As to the SFO charges in the Barclays case we only know this:

Conspiracy to commit fraud by false representation in relation to the June 2008 capital raising, contrary to s1 and s2 of the Fraud Act 2006 and s1(1) of the Criminal Law Act 1977 – Barclays Plc, John Varley, Roger Jenkins, Thomas Kalaris and Richard Boath.

Conspiracy to commit fraud by false representation in relation to the October 2008 capital raising, contrary to s1 and s2 of the Fraud Act 2006 and s1(1) of the Criminal Law Act 1977 – Barclays Plc, John Varley and Roger Jenkins.

Unlawful financial assistance contrary to s151 of the Companies Act 1985 – Barclays Plc, John Varley and Roger Jenkins.

The Gulf investors named in 2008 were Sheikh Hamad bin Jassim bin Jabr al Thani, Qatar’s prime minister at the time and Sheikh Mansour bin Zayed al-Nahyan of Abu Dhabi. The side deals the bankers are charged for relate to the Qatari part of the investment, i.e. Barclays capital raising arrangements with Qatar Holding LLC, part of Qatar’s sovereign wealth fund and al Thani’s investment vehicle Challenger Universal Ltd and $3bn loan issued by Barclays to the State of Qatar, acting through the Ministry of Economy and Finance in November 2008.

Viewing the Barclays side deals via the Kaupthing case

The Barclays saga is allegedly that apart from the Qatari investments in Barclays in June and October 2008, in total £6.1bn, there were two side deals, allegedly financial assistance: Barclays promised to pay £322m to Qatari investors, apparently fee for helping Barclays with business development in the Gulf; in November 2008, Barclays agreed to issue a loan of $3bn to the State of Qatar, allegedly fitting the funds prime minister Sheikh al Thani invested, according to The Daily Telegraph.

Thus it seems the Barclays bankers (all four following the June 2008 investment, two of them following the October investment) were allegedly misleading the markets, i.e. market manipulation, when they commented on the two Qatari investments.

If we take cue from the Icelandic al Thani case it is most likely that the Barclays managers begged and pestered the Gulf investors, known for their deep pockets, to invest.

In the al Thani case, the Abu Dhabi sovereign wealth fund had earlier considered buying Kaupthing shares but thought the price was too high. Kaupthing then wooed the Qatari investors with some good offers.

What Kaupthing promised was a “risk-free” loan, a classic Kaupthing special offer to special clients, to place as an investment in Kaupthing. In other words, there was never any money coming into Kaupthing as an investment. It was just money merry-go-round from one Kaupthing account to another: funds going out as a loan and coming back as an investment. In addition, the investors got a loan of $50m directly into their pockets, defined as pre-paid profit.

Barclays hardly made such a crude offer to the Qatari investors but the £322m fee leads the thought to the pre-paid profit in the Kaupthing saga; the Barclays fee could allegedly be defined as pre-payment for services-to-come.

The $3bn loan to the state of Qatar is intriguing, given that the state of Qatar is and the finances of its ruling family have allegedly often seemed closely connected.

What we don’t know regarding the Barclays side deals

The September 2008 Qatari investment in Kaupthing figured in the 2010 report of the Special Investigative Commission, SIC, a report that thoroughly explained and mapped the operations of the Icelandic banks up to the 2008 collapse. The criminal case added details to the SIC saga. It is for example clear that Kaupthing didn’t really expect the Gulf investors to pay back the investment but handed them $50m right away.

Little is yet known about the details of the alleged Barclays side deals. How were the covenants for the $3bn loan? Has this loan been repaid or is it still on Barclays books? And was the service for the £322m ever carried out? Was there any specification as to what Barclays was paying for? Why were these services apparently pre-paid instead of being paid against an invoice after the services had been carried out?

These are some of the things we would need to know in order to assess the side deals and their context and connections to the Qatari investment in Barclays. Clearly, the SFO knows and this will no doubt be part of the coming court case.

The whiff of Qatari investors and how it touches Deutsche Bank

The Kaupthing resolution committee went after the Qatari investors to recover the loans, threatening them with legal proceedings. Investigators from the Office of the Special Prosecutor did question the investors.

According to Icelog sources, the Qatari investors were adamant about clarifying the situation both with Kaupthing and the OSP. The understanding was that the investors were worried about their reputation. They did in the end reach a settlement with the Kaupthing resolution committee as Kaupthing announced in 2013.

These two investment sagas do however leave a certain whiff. In August last year, when it transpired that Qatari investors had invested in troubled Deutsche Bank I sent a query to Deutsche’s spokesman asking if the bank was possibly lending the investors money. I got a stern reply that I was hinting at Deutsche committing a legal offense (well, as if Deutsche had not been found to have rigged markets, assisted in money laundering etc) but was later assured that no, Deutsche had not given any financial assistance to its Qatari investors, no side deals related to their investment in the bank.

Companies don’t commit crimes – people do

Although certainly not the only one, Barclays is a bank with a long register of recent financial sins, inter alia: in 2012 it paid a fine of £290m for Libor manipulation; in 2015 it paid £2.3bn for rigging FX markets and £72m to settle money laundering offenses.

As to lessons learnt: this spring, it turned out that Barclays CEO Jes Staley, has broken whistleblower-rules by trying to unmask a Barclays whistleblower. CEOs have been remarkably short lived at Barclays since Varley left in 2010: his successor Bob Diamond was forced out in 2012, replaced by Antony Jenkins who had to leave in 2015, followed by Jes Staley.

In spite of Barclays being fined for matters, which are a criminal offence, the SFO has treated these crimes (and similar offences in many other banks) as crimes not committed by people but companies, i.e. no Barclays bankers have been charged… until now.

After all, continuously breaking the law in multiple offences over a decade, under various CEOs indicates that something is seriously wrong at Barclays (and in many other big banks). Normally, criminals are not allowed just to pay their way out of criminal deeds. In the case of banking fines banks have actually paid with funds accrued by criminal offences. Ironically, banks pay fines with shareholders’ money and most often, senior managers have not even taken a pay cut following costs arising from their deeds.

In all its unknown details the Barclays case is no doubt far from simple. But compared to FX or Libor rigging, it is manageable, its focus being the two investments, in June and October 2008, the £322m fee and the November 2008 loan of $3bn.

The BBC is not amused… at SFO charges

Instead of seeing the merit in this heroic effort by the SFO BBC’s business editor Simon Jack is greatly worried, after talking to what only appear to be Barclays insiders. There is no voice in his comment expressing any sympathy with the rule of law rather than the culpable bankers.

Jack asks: Why, over the past decade, has the SFO been at its most dogged in the pursuit of a bank that DIDN’T require a taxpayer bailout? In fact, it was Barclays’ very efforts to SPARE the taxpayer that gave rise to this investigation.

This is of course exactly the question and answer one would hear from the charged bankers but it is unexpected to see this argument voiced by the BBC business editor on a BBC website as an argument against an investigation. In the Icelandic al Thani case, those charged and eventually sentenced also found it grossly unfair that they were charged for saving the bank… with criminal means.

Jack’s reasoning seems to justify a criminal act if the goal is deemed as positive and good for society. One thing for sure, such a society is not optimal for running a company – the healthiest and most competitive business environment surely is one where the rule of law can be taken for granted.

Another underlying assumption here is that the Barclays management sought to safe the bank by criminal means in order to spare the taxpayer the expense of a bailout. Perhaps a lovely thought but a highly unlikely one. There were plenty of commentaries in 2008 pointing out that what really drove Barclays’ John Varley and his trusted lieutenants hard to seek investors was their sincere wish to avoid any meddling into Barclays bonuses etc.

Is the alleged Barclays fraud a “victimless crime”?

It’s worth remembering that taxpayers didn’t bail out Barclays and small shareholders didn’t suffer the massive losses that those of RBS and Lloyds did. One former Barclays insider said that if there was a crime then it was “victimless” and you could argue that Barclays – and its executives – did taxpayers and its own shareholders a massive favour, writes Jack.

It comes as no surprise that “one former Barclays insider” would claim that saving a bank, even by breaking the law, is just fine and actually a good deed. For anyone who is not a Barclays insider it is a profound and shocking misunderstanding that a financial crime like the Barclays directors allegedly committed is victimless just because no one is walking out of Barclays with a tangible loss or the victims can’t be caught on a photo.

We don’t know in detail how Barclays was managed, there is no British SIC report. So we don’t know if the $3bn loan has been paid back. If it was not repaid or had abnormally weak covenants it makes all Barclays clients a victim because they will have had to pay, in one way or another, for that loan.

Even if the loan was normal and has been paid a bank that uses criminal deeds to survive turns the whole society into the victims of its criminal deeds: financial assistance and market manipulation skew the business environment, making the level playing field very uneven.

Pushing Jack’s argument further it could be conclude that the RBS and Lloyds managers at the time did evil by not using criminal deeds to save their banks, compared to the saintly Barclays managers who did – a truly absurd statement.

Charging those at the top compared to charging only the “arms” of the top managers, i.e. those who carry out the commands of senior managers, shows that the SFO understands how a company like Barclays functions; making side deals like these is not decided by low-level staff. Further, again with an Icelandic cue, it is highly likely that the SFO has tangible evidence like emails, recordings of phone calls etc. implicating the four charged managers.

The Barclays battles to come

Criminal investigations are partly to investigate what happened, partly a deterrent and partly to teach a lesson. If the buck stops at the top, charging those at the top is the right thing to do when these managers orchestrate potentially criminal actions.

But those at the top have ample means to defend themselves. Icelandic authorities now have a considerable experience in prosecuting alleged crimes committed by bankers and other wealthy individuals.

And Icelanders also have an experience in observing how wealthy defendants react: how they try to manipulate the media via their own websites and/or social media, by paying PR firms to orchestrate their narrative, how their lawyers or other pillars of society, strongly identifying with the defendants, continue to refute sentences outside of the court room etc. And how judges, prosecutors and other authorities come under ferocious attack from the charged or sentenced individuals and their errand boys.

All of this is nothing new; we have seen this pattern in other cases where wealth clashes with the law. And since this is nothing new, it is stunning to read such a blatant apology for the charged Barclays managers on the website of the British public broadcaster. Even if the SFO prosecution against the Barclays bankers were to fail apologising the bankers ignores the general interest of society in maintaining a rule of law for everyone without any grace and favour for wealth and social standing.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Supreme Court rules in al Thani case: imprisonment confirmed

“The results today shows that it is possible to bring complicated financial cases to court and get conviction,” Ólafur Hauksson head of Office of the Special Prosecutor said to Icelog, now that the Supreme Court has ruled in one of the OSP’s major cases, the al Thani case. “Building up the expertise has been a long process but the ruling today demonstrates that setting up an office, which didn’t exist earlier, was fully justified. No society can tolerate that certain parts of it are beyond law and justice.”

Those four charged were Sigurður Einarsson chairman of Kaupthing board, Magnús Guðmundsson manager of Kaupthing Luxembourg, Kaupthing CEO Hreiðar Már Sigurðsson and Ólafur Ólafsson the bank’s second largest shareholder. Reykjavík District Court had earlier ruled in the case where Einarsson was sentenced to 5 years in prison, Guðmundsson 3 years, Sigurðsson 5 1/2 years and Ólafsson 3 1/2 years. The Supreme Court has confirmed the ruling over Sigurðsson whereas Ólafsson has now been sentenced to 4 1/2 years, Einarsson to 4 years instead of 5 years and Guðmundsson to 4 years.

As detailed in an earlier Icelog the core of the al Thani case were loans to Ólafsson and Sheikh Mohammed bin Khalifa al Thani, a Qatari investor from the country’s ruling family. It is important to notice that the issuing of these loans was the criminal deed in the case – the three Kaupthing managers broke law by doing it and Ólafsson was complicit in that criminal deed.

The story behind the case is that in in September 2008 Kaupthing made much fanfare of the fact that Sheikh al Thani bought 5.1% of Kaupthing’s shares. The 5.1% stake in the bank made al Thani Kaupthing’s third largest shareholder, after Olafsson who owned 9.88%. This number, 5.1%, was crucial, meaning that the investment had to be flagged – and would certainly be noticed. Einarsson, Sigurðsson and Ólafsson all appeared in the Icelandic media, underlining that the Qatari investment showed the bank’s strong position and promising outlook.

What these three didn’t tell was that Kaupthing lent al Thani the money to buy the stake in Kaupthing – a well known pattern, not only in Kaupthing but in the other Icelandic banks as well. A few months later, stories appeared in the Icelandic media indicating that al Thani was not risking his own money. More was told in SIC report and the SIC recount indicated a fraudulent behaviour. The ruling today has confirmed the doubts, which have surrounded this investment from early on.

Although the case draws its name from Sheikh al Thani he has not been accused of any wrongdoing. He was one of the witness in the case, gave a statement over the phone.

As I have pointed out earlier there is an echo of this investment story in the ongoing investigation into Qatari and Middle East investment in Barclays, which saved the bank from seeking state support in autumn 2008.

The ruling in Iceland is i.a. in stark contrast to how Irish courts have tackled financial crimes related to the Irish collapsed banks. In April last year a court ruled that two former Anglo Irish managers, who had been convicted of issuing loans to prop up the bank’s share price, should not be imprisoned in spite of being found guilty. The judge ruled it was unjust they should go to prison for a criminal deed because they believed they had acted lawfully. Sean FitzPatrick, the bank’s former chairman, was cleared in this case. I find this Irish ruling truly incredible. This loan saga – loans to the so-called “Golden Circle” – has striking parallels in other Icelandic cases, which are being processed.

Icelandic law on financial fraud is in most respect similar to law on these issues in Northern Europe. There is nothing special about the Icelandic situation – except the will to carry out investigations and bringing cases to court. As Hauksson pointed out financial crimes need not be too complicated to be successfully prosecuted – and no part of society should be beyond the reach of the law.

*Update: I have seen some comments that because the four sentenced to prison in the al Thani case are living abroad they are unlikely to go to prison. That is not correct: the fact that they live abroad – in London, Switzerland and Luxembourg – will apparently not change anything. Ólafsson has already said he will come when called to go to prison. That is an unavoidable consequence of the sentencing.

*Update 25.2. 2015: Ólafsson asked to start his sentencing as soon as possible. According to Icelandic media he is now already in prison at Kvíabryggja, Snæfellsnes, where this sentenced in earlier banking collapse cases have been sent to jail (see here for details of this prison).

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Reykjavik District Court rules in the al Thani case today

A ruling in the so-called al Thani case is expected today at 3pm in Iceland. The Office of the Special Prosecutor earlier charged Kaupthing top managers – Sigurður Einarsson, Hreiðar Már Sigurðsson, Magnús Guðmundsson – and the second largest Kaupthing shareholder, Ólafur Ólafsson, for market manipulation and breach of fiduciary duty. The case derives its name from a member of the Qatar-ruling al Thani family, involved in the case but not charged.

Involving both management and a shareholder this case is one of the most extensive cases brought by the OSP. So far, the District Court has tended to be more lenient than the Supreme Court in cases brought by the OSP. All of the OSP cases have gone to the second and highest court, the Supreme Court. No matter the outcome, this case will almost certainly be appealed by either party.

The OSP had demanded a six year unsuspended imprisonment for Einarsson and Sigurðsson and four years for the other two. See here for earlier Icelogs on the al Thani case.

UPDATE: Sigurðsson has been sentenced to 5 1/2 years, Einarsson 5 years, Ólafsson 3 1/2 years and Guðmundsson 3 years.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Yet another unexpected turn in the al Thani case

The al Thani case has taken yet another unexpected turn – it seems that there are only unexpected turns in this case. Instead of postponing the oral hearing until February next year, as Justice Pétur Guðgeirsson of Reykjavík County Court had decided after a meeting with the new defence lawyers, the case will be assigned to a new judge, Símon Sigvaldason. Guðgeirsson will be off due to illness. The oral hearing is now set to start 21 October. The Office of the Special Prosecutor and the defendants heard of this yesterday, according to Rúv.

The al Thani case relates to the share purchase of a Qatari investor from Qatar’s ruling family. He bought 5.1% of shares in Kaupthing in September 2008. It later transpired that Kaupthing financed the purchase. The case has strong parallels to a Qatari investment in Barclays in autumn 2008, saving the bank from seeking a bail-out from the UK Government (link to earlier Icelogs on the al Thani case).

This is the latest in a long wrestle over bringing the al Thani case to court. As reported earlier, the defense team of Sigurður Einarsson chairman of Kaupthing and Ólafur Ólafsson, the bank’s second largest shareholder, had used up all possibilities to have the case thrown out or postponed when they brought about a delay by simply resigning from the case and then refusing to obey the judge when he refused to accept their resignation.

The fact that the court itself has now taken action to diminish the delay indicates that further delaying tactics might prove more difficult. Those following the prosecution of bankers in Iceland are no doubt in for some interesting twists and turns in the different trial sagas.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

The latest on the al Thani case

Instead of starting the oral hearings in the al Thani case – where the Office of the Special Prosecutor in Iceland has charged three former Kaupthing managers and the bank’s second largest shareholder – as planned Thursday morning, April 11, the hearings were postponed until further notice. This happened after the defense lawyers of Sigurdur Einarsson and Olafur Olafsson took the unprecedented step not to heed the judge who refused to accept their resignation of the case. In court, prosecutor Bjorn Thorvaldsson pleaded that the two lawyers would receive penalties for willfully causing delays to the case. The judge will consider any such step after the case had finally been heard.

The defendants have now appointed new lawyers who need to read up on the case. The two lawyers who resigned – Gestur Jonsson and Ragnar Hall – are two of the most experienced lawyers in Iceland. Jonsson was i.a. lawyer for Baugur’s main shareholder Jon Asgeir Johannesson in the so-called Baugur case and is also Johannesson’s defense lawyer in a case brought against Johannesson by the Office of the Special Prosecutor, the so-called Aurum case.

The defense in the Aurum case shows a similar trend to the al Thani case. – The oral hearings were due to start in January, got postponed until early April when it was again postponed, this time because documents that the defense team wanted to present were not ready. After the events in the al Thani case Special Prosecutor Olafur Hauksson expressed his worries that similar things might start to happen in other cases brought by the OSP.

The two lawyers replacing Jonsson and Hall – Olafur Eiriksson and Thorolfur Jonsson– are not at all big names in the Icelandic legal profession. The are both from Logos, the largest Icelandic law firm.

The two lawyers who resigned claim they felt forced to resign because of the way their clients have been treated. Still, they have neither filed any complaints nor taken any action. Earlier, they had made several attempts to have the case thrown out or postponed, taking their cases all the way to the Supreme Court, which has rejected their attempts. In its last ruling re the case the Supreme Court reprimanded the two lawyers, saying their case was without merit.

The strong feeling in Iceland is that the two lawyers resigned in order to gain the postponements they could not obtain via the courts. It is well known in big white-collare cases that highly paid lawyers often try all possible tricks to thwart and delay going to court. Both lawyers strongly deny any such tactics.

The judge will meet with the new defense lawyers on April 22, after which it might be clear when the oral hearings will start. Given the complexity of the case, it is quite likely that the next chapter in the case will not commence until autumn.

*Here are earlier blogs where the al Thani case is mentioned – and here is the story behind the charges in the al Thani case.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

New turn in the al Thani case – but again on track to start on April 11th – but not quite (updated)

Just as the defense team for those indicted in the al Thani case – Kaupthing’s second largest shareholder Olafur Olafsson and managers Sigurdur Einarsson, Hreidar Mar Sigurdsson and Magnus Gudmundsson – had exhausted all means of getting the case thrown out of court or suspended, the defense lawyers for Einarsson and Olafsson, Gestur Jonsson and Ragnar Hall, have resigned from the case. They claim that the defendants are not getting a fair trial and criticise the investigation by the Office of the Special Prosecutor and how the County Court and the Supreme Court have handled their case.

Bjorn Thorvaldsson, who represents the OSP, says to Ruv that the move by the defense lawyers came as a great surprise. The two lawyers tried five different ways to have the case thrown out or suspended, all five times taking the case to the Supreme Court. In the last case, for suspension, ruled on the the Supreme Court only last week, the Supreme Court reprimanded the two lawyers in its ruling for bringing a needless case to the Court.

However, only a few hours after the two lawyers handed in their letter (in Icelandic) to the Country Court, the judge in the coming case, Petur Gudgeirsson, refused to acknowledged their resignation. The oral hearings are planned to run for eight days. Ca. 50 people are being called to give witness. Now that the latest attempt by the defense lawyers to suspend the case it seems that the oral hearings will start, as planned, on Thursday.

*Updated: In spite of the judge having refused to acknowledge the lawyers’ resignation the two defense lawyers have reiterated their intention. No one seems to know what the legal situation is here. The lawyers can hardly be pushed against their will to defend their two clients. It means that the case is now in jeopardy and might be postponed until next autumn.

*A link to earlier Icelogs on the al Thani case.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

The al Thani Kaupthing case on the horizon

The case that the Icelandic Office of the Special Prosecutor is bringing against three Kaupthing managers and Olafur Olafsson, at the time Kaupthing’s second largest shareholder, is coming up in the Reykjavik County Court today. It seems that now all legal quibbles the defendants brought up have been dealt with – all of them brushed aside – which means that the case can now take its course. Not quite now though, that will happen in mid April when the main proceedings are due to start. The Kaupthing managers charged are Sigurdur Einarsson, Hreidar Mar Sigurdsson and Magnus Gudmundsson.

This is by far the largest case brought so far by the OSP. There are fifty names on the witness list. One of them is the man who has given the case its name, Sheikh Mohammed bin Khalifa al Thani. The Sheikh is not accused of any wrongdoing and has not been charged but the OSP would like him to bear witness. It is not known if he will answer the request.

This case has been extensively dealt with on Icelog, i.a. here. The interesting UK angle to the story is that there are striking parallels of this loan story – a Middle Eastern investor being lent money by a bank to invest in that same bank, which then uses that investment as a sign of its rude health – in the Barclay story, also from 2008, now being investigated by the SFO, also covered earlier on Icelog.

Middle Eastern and Russian money is famously finding its way into many London-based investments and investment companies, adding glamour and building cranes to the city. The question is how sparkling clean and healthy all this money is – but as we know from the HSBC money laundering case even major banks are not too squeamish when it comes to the choosing their customers.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Kaupthing Winding-Up Board settles with Sheikh al Thani

Kaupthing hf – the Winding-up Board of Kaupthing bank – has announced it has reached “an agreement concerning the settlement of all claims and liabilities between them. This agreement has been reached on a commercial basis with no admission of liability by any party. As a result of the settlement, the proceedings commenced in Iceland by Kaupthing against Sheikh Mohammed Bin Khalifa Bin Hamad Al Thani have been discontinued and all other claims and liabilities have been released. All other terms of the settlement remain confidential.”

According the SIC report Kaupthing loaned companies owned by Sheikh al Thani to buy shares in Kaupthing. This loan was allegedly behind the purchase of Kaupthing shares in September 2008. As reported earlier on Icelog the Office of the Special Prosecutor has charged three former Kaupthing managers and Kaupthing’s second largest shareholder in relation to this loan in a case similar to Barclays and the Qatari investors: neither bank declared it had allegedly loaned the investors money to buy the shares. In addition, Kaupthing lent the Sheikh against future profits. The Sheikh has not been charged of any wrong doing in Iceland but according to Icelandic media the OSP has indicated it might want to call him in as a witness in this case.

So what is Kaupthing hf settling? The SIC report and the OSP charges indicate that as well as issuing two loans in ISK, now around €157m, one of the Sheikh’s companies got a loan of $50m. This loan was “parts of the profits from the transaction” according to a Kaupthing overview of loans issued or discussed in one of the bank’s credit committees just before it collapsed. According to the writ, these three loans have never been repaid.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

The al Thani story behind the Kaupthing indictment (updated)

The Office of the Special Prosecutor is indicting Kaupthing’s CEO Hreidar Mar Sigurdsson and Kaupthing’s chairman Sigurdur Einarsson for a breach of fiduciary duty and market manipulation in giving loans to companies related to the so-called ‘al Thani’ case; indicting Kaupthing Luxembourg manager Magnus Gudmundsson for his participation in these loans and Kaupthing’s second largest shareholder Olafur Olafsson for his participation. In addition, Olafsson faces charges of money laundering because he accepted loans to his companies without adequate guarantees.

In September 2008 Kaupthing made much fanfare of the fact that Sheikh Mohammed bin Khalifa al Thani, a Qatari investor related to the Qatar ruler al Thani, bought 5.1% of Kaupthing’s shares. The 5.1% stake in the bank made al Thani Kaupthing’s third largest shareholder, after Olafsson who owned 9.88%. This number, 5.1%, was crucial, meaning that the investment had to be flagged – and would certainly be noticed. Einarsson, Sigurdsson and Olafsson all appeared in the Icelandic media, underlining that the Qatari investment showed the bank’s strong position and promising outlook.

What these three didn’t tell was that Kaupthing lent the al Thani the money to buy the stake in Kaupthing – a well known pattern, not only in Kaupthing but in the other Icelandic banks as well. A few months later, stories appeared in the Icelandic media indicating that al Thani wasn’t risking his own money. More was told in SIC report – and now the OSP writ tells quite a story. A story the four indicted and their defenders will certainly try to quash.

The story told in the OSP writ is that on Sept. 19 Sigurdsson organised that a loan of $50m was paid into a Kaupthing account belonging to Brooks Trading, a BVI company owned by another BVI company, Mink Trading where al Thani was the beneficial owner. Sigurdsson bypassed the bank’s credit committee and was, according to the bank’s own rules, not allowed to authorise on his own a loan of this size. The loan to Brooks was without guarantees and collaterals. This loan, first due on Sept. 29 but referred to Oct. 14 and then to Nov. 11 2008, has never been repaid. – Gudmundsson’s role was to negotiate and organise the payment to Brooks. According to the charges he should have been aware that Sigurdsson was going beyond his authority by instigating the loan.

But this was only the beginning. The next step, on Sept. 29, was to organise two loans, each to the amount of ISK12.8bn, in total ISK25.6bn (now €157m) to two BVI companies, both with accounts in Kaupthing: Serval Trading, belonging to al Thani and Gerland Assets, belonging to Olafsson. These two loans were then channelled into the account of a Cyprus company, Choice Stay. Its beneficial owners are Olafsson, al Thani and another al Thani, Sheikh Sultan al Thani, said to be an investment advisor to al Thani the Kaupthing investor. From Choice Stay the money went into another Kaupthing account, held by Q Iceland Finance, owned by Q Iceland Holding where al Thani was the beneficial owner. It was Q Iceland Finance that then bought the Kaupthing shares. As with the Brooks loan, none have been repaid.

These loans were without appropriate guarantees and collaterals – except for Serval, which had al Thani’s personal guarantee. After noon Wed. Oct. 8, when Kaupthing had collapsed, the US dollar loan to Brooks was sent express to Iceland where it was converted into kronur at the rate of ISK256 to the dollar (twice the going rate in Iceland that day) and used to repay Serval’s loan to Kaupthing – in order to free the Sheik from his personal guarantee.

This is the scheme, as I understand it from the OSP writ. And all this was happening as banks were practically not lending. There was a severe draught in the international financial system.

The Brooks loan is interesting. It can be seen as an “insurance” for al Thani that no matter what, he would never lose a penny. When things did go sour – the bank collapsed and all the rest of it – this money was used to unburden him of his personal guarantee. Otherwise, it would have been money in his pocket. It’s also interesting that the loan was paid out to Brooks on Sept. 19, his investment was announced on Sept. 22 – but the trade wasn’t settled until Sept. 29. This means that his “guarantee” was secured before he took the first steps to become a Kaupthing investor.

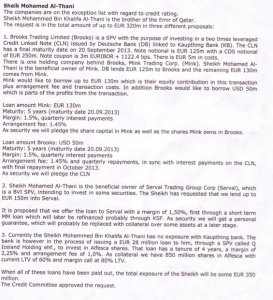

Apparently, Kaupting’s credit committee was in total oblivion of all this. The CC was presented with another version of reality. Below is an excerpt from the minutes regarding the al Thani loan, discussed when the Board of Kaupthing Credit Committee met in London Sept. 24. 2008 (click on the image to enlarge).

Three things to note here: that the $50m loan “is parts of the profits from the transaction.” Second, that al Thani borrowed €28m to invest in Alfesca. It so happens that Alfesca belonged to Olafsson. Al Thani’s acquisition in Alfesca was indeed announced in early summer of 2008 and should, according to rules, have been settled within three months. At the end of Oct. 2008 it was announced that due to the market upheaval in Iceland al Thani was withdrawing his Alfesca investment. Thirdly, it’s interesting to note that Deutsche bank did lend into this scheme – as it also did into another remarkable Kaupthing scheme where the bank lent money to Olafsson and others for CDS trades, to lower the bank’s spread; yet another untold story.

According to the OSP writ, the covenants of the al Thani loans differed from what the CC was told. It’s also interesting to note that the $50m loan to al Thani’s company was paid out on Sept. 19, five days before the CC meeting. This fact doesn’t seem to have been made clear to the CC.

The OSP writ also makes it clear that any eventual profits from the investment would have gone to Choice Stay, owned by Olafsson and the two al Thanis.

Why did al Thani pop up in September 2008? It seems that he was a friend of Olafsson who has is said to have extensive connection in al Thani’s part of world. Olafsson’s Middle East connection are said to go back to the ‘90s when he had to look abroad to finance some of his Icelandic ventures. London is the place to cultivate Middle East connections and that’s also where Olafsson has been living until recently. It is interesting to note that the Financial Times reports on the indictments without mentioning the name of Sheikh al Thani.

The four indicted Icelanders are all living abroad. Sigurdur Einarsson lives in London and it’s not known what he has been doing since Kaupthing collapsed. Hreidar Mar Sigurdsson lives in Luxembourg where he, together with other former Kaupthing managers, runs a company called Consolium. His wife runs a catering company and a hotel in Iceland.

Magnus Gudmundsson also lives in Luxembourg. David Rowland kept him as a manager after buying Kaupthing Luxembourg, now Banque Havilland, but Rowland fired Gudmundsson after Gudmundsson was imprisoned in Iceland for a few days, related to the OSP investigation. In the Icelandic Public Records it’s said that Olafsson lives in the UK but he has now been living in Lausanne for about two years. In Iceland, he has a low profile but is most noted in horse breeding circles, a popular hobby in Iceland. He breeds horses at his Snaefellsnes farm and owns a number of prize-winning horses.

Following the indictment, Olafsson and Sigurdsson have stated that they haven’t done anything wrong and that the al Thani Kaupthing investment was a genuine deal. The case could come up in the District Course in the coming months. But perhaps this isn’t all: it’s likely that there will be further indictment against these four on other questionable issues related to Kaupthing.

*The OSP indictment, in Icelandic.

**Does it matter that the four indicted are all living abroad? When I made an inquiry at the Ministry of Justice in Iceland some time ago whether Icelanders, living abroad but indicted in Iceland, could seek shelter in any country in Europe by refusing to return to Iceland I was told they couldn’t. If an Icelandic citizen is indicted in Iceland and refuses to return, extradition rules will apply. In this case, Iceland would be seeking to have its own citizens extradited and such a request would be met. – It has been noted in Iceland how many of those seen to be involved in the collapse of the banks now live abroad. It can hardly be because they intend to avoid being brought to court – they would have to go farther. Ia it’s more likely they want to avoid unwanted attention. For those with offshore funds it might be easier to access them outside of Iceland rather than in a country fenced off by capital controls.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.