Search Results

OSP brings charges in the al-Thani case (updated)

The Office of the Special Prosecutor in Iceland has now brought charges in the so-called al-Thani case. In September 2008 Kaupthing announced that a Qatar investor, Mohamed bin Khalifa al-Thani, had bought just over 5% of share in Kaupthing. It later turned out that al-Thani wasn’t risking his own money but Kaupthing’s fund: the bank lent him money to buy the shares. A familiar pattern but this was an important statement because it made the bank seem like a good investment. The interesting thing is that according to documents from Kaupthing Deutsche Bank was involved in the al-Thani investment scheme.

Those charged now are the bank’s CEO Hreidar Mar Sigurdsson, Chairman Sigurdur Einarsson, Kaupthing Luxembourg manager Magnus Gudmundsson and the second largest shareholder in Kaupthing Olafur Olafsson. They are all charged with market manipulation. Sigurdsson and Einarsson are seen as the organisers and are in addition charged with breach of fiduciary duty. Olafsson and Gudmundsson are charged for participation in this breach and Olafsson is in addition charged for money laundering.

The charges are not public yet. Those four now charged are all living abroad. Olafsson has sent out a statement denying the charges. Sigurdsson says he is disappointed and holds on to the official story from September 2008: the sale was genuine and the sheikh did indeed risk his money.

*A blog on the al-Thani case will be coming here soon. Here are earlier blogs referring to the al-Thani case. – The OSP writ can be read here, only in Icelandic.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Deutsche Bank, Kaupthing and alleged market manipulation

“It’s not unlikely that an international bank wants to avoid being accused of market manipulation,” said Prosecutor Björn Þorvaldsson in Reykjavík District Court on October 11, 2017. The “international bank” was Deutsche Bank and the court case was the so-called CLN case. Deutsche was not charged with anything – the criminal case was against Kaupthing managers, charged with fraudulent lending of €510m into a scheme concocted with Deutsche. However, both Kaupthing administrators and liquidators of two BVI companies saw a way of using alleged market manipulation in these transactions to recover from Deutsche the €510m, Kaupthing had paid to Deutsche. In December 2016, Deutsche eventually concluded that paying €425m was preferable to having to recount the ignominious saga in court. All parties to the agreement are unwilling to divulge further facts but a UK court document throws light on Deutsche’s part in the alleged market manipulation, affecting not only Kaupthing’s CDS spreads but also the bond market. – The question is if this really was the only scheme of alleged market manipulation that Deutsche instigated. Further, the case throws light on how tension between Deutsche’s staff working on the scheme and those responsible for legal and reputational risk was dealt with, potentially explaining the same in other Deutsche schemes.

In January 2009, Kaupthing’s ex-chairman Sigurður Einarsson felt compelled to send a letter to family and friends to counter claims in the Icelandic media regarding Kaupthing’s activities in the months before the bank failed in October 2008. One was that in 2008 the bank had traded on its own credit default swaps, CDS, linked to credit-linked notes, CLN, to bring down the bank’s CDS spreads and thus lower the bank’s cost of financing.

Einarsson wrote that Kaupthing had indeed funded such transactions, via what he called “trusted clients” in cooperation with Deutsche Bank; the underlying assumption was that a reputable international bank would not have done anything questionable – those were the days before international banks like Deutsche were being questioned and fined for criminal actions.

The Icelandic 2010 Special Investigations Committee, SIC, report told the CDS saga in greater detail, documenting Deutsche’s full knowledge from the beginning. A 2012 London court decision added to the story: in order to recover documents related to the transactions, Stephen Akers and Mark McDonald from Grant Thornton London – appointed liquidators of two BVI companies, Chesterfield and Partridge, used in the CDS transactions in the names of the “trusted clients” – had brought Deutsche Bank to court.

The CDS saga was summed up in 2014 charges in a criminal case in Iceland: Einarsson, Kaupthing’s CEO Hreiðar Már Sigurðsson and head of the bank’s Luxembourg operations Magnús Guðmundsson were charged with breach of fiduciary duty, causing a loss of €510m to Kaupthing, some of which Kaupthing paid to Deutsche literally as Kaupthing was failing. – All of this has earlier been reported in detail on Icelog(most notably here, December 2015 and here, November 2017).

The latest addition to the CDS saga is in another court document, consolidated particulars* from 2014, as the liquidators of the two BVI companies sought to recover funds from Deutsche in a civil case by suing Sigurðsson, Einarsson, Venkatesh (or Venky) Vishwanathan the Deutsche senior banker who liaised with Kaupthing on the CLN trades and, most importantly, the liquidators sued Deutsche Bank. The fifth defendant was Jaeger Investors Corp., BVI, a director nominee for Chesterfield and Partridge.

The 2014 document shows, in extensive quotes from emails etc., that contrary to Deutsche’s version in its Annual Reports etc., the bank was fully aware of the fact that Kaupthing set up these trades and funded them in order to influence its CDS spreads, i.e. allegedly the scheme was effectively a market manipulation. In addition, the Icelandic criminal case related to the CLN transactions documented that Deutsche was on the other side of the bet, thereby effectively creating a hedge for itself.

Thus the Icelandic SIC, the Icelandic Special Prosecutor, the Kaupthing administrators and of course the liquidators of the two BVI companies have all come to the same conclusion: Kaupthing and Deutsche colluded in market manipulation.

This goes a long way to explain why Deutsche, by the end of 2016, chose to settle with Kaupthing – Deutsche Bank was not going to be dragged into court to explain the discrepancy between its public statements and internal Deutsche documents, in addition to profiting from being a counterparty in the transactions. The liquidators alleged Deutsche took part in criminal activity. This has however not been tested in court; the SFO had as early as 2010 looked at these transactions but later apparently dropped its investigation as so many others.

One intriguing aspect of the CLN transactions is that Deutsche staff took measures to hide facts from staff working on legal and reputational risk. This has immense ramification for so many other questionable transactions in the bank, which have come to light over the last few years, inter alia Deutsche’s involvement in the largest known case of money laundering of all times: Danske Bank money laundering in Estonia 2007 to 2015, a saga still in the making.

The Deutsche version of the CDS saga (is very short)

Deutsche first mentioned the CLN claims in its 2015 Annual Report (p. 340). As an introduction to the bank’s 2016 Annual Report, Deutsche CEO John Cryan sent out a message to the bank’s employees on February 2 2017 where the settlement with Kaupthing was one of four legal issues the bank had resolved and chose to emphasise.

Deutsche has consistently presented the CDS transactions as if it had only learned of the realities well after the CLN transactions, as here in 2017 (the text is the same in Deutsche’s 2015 and 2016 (p. 369) Annual Reports):

Kaupthing CLN Claims

In June 2012, Kaupthing hf, an Icelandic stock corporation, acting through its winding-up committee, issued Icelandic law claw back claims for approximately € 509 million (plus costs, as well as interest calculated on a damages rate basis and a late payment rate basis) against Deutsche Bank in both Iceland and England. The claims were in relation to leveraged credit linked notes (“CLNs”), referencing Kaupthing, issued by Deutsche Bank to two British Virgin Island special purpose vehicles (“SPVs”) in 2008. The SPVs were ultimately owned by high net worth individuals. Kaupthing claimed to have funded the SPVs and alleged that Deutsche Bank was or should have been aware that Kaupthing itself was economically exposed in the transactions.Kaupthing claimed that the transactions were voidable by Kaupthing on a number of alternative grounds, including the ground that the transactions were improper because one of the alleged purposes of the transactions was to allow Kaupthing to influence the market in its own CDS (credit default swap) spreads and thereby its listed bonds. Additionally, in November 2012, an English law claim (with allegations similar to those featured in the Icelandic law claims) was commenced by Kaupthing against Deutsche Bank in London (together with the Icelandic proceedings, the “Kaupthing Proceedings”). Deutsche Bank filed a defense in the Icelandic proceedings in late February 2013. In February 2014, proceedings in England were stayed pending final determination of the Icelandic proceedings. Additionally, in December 2014, the SPVs and their joint liquidators served Deutsche Bank with substantively similar claims arising out of the CLN transactions against Deutsche Bank and other defendants in England (the “SPV Proceedings”). The SPVs claimed approximately € 509 million (plus costs, as well as interest), although the amount of that interest claim was less than in Iceland. Deutsche Bank has now reached a settlement of the Kaupthing and SPV Proceedings which has been paid in the first quarter of 2017. The settlement amount is already fully reflected in existing litigation reserves and no additional provisions have been taken for this settlement.

As can be seen from the text, the wording is carefully calculated. Inter alia, Deutsche has never in its public statements mentioned when and how it learned of the realities of the scheme, i.e. it was funded by Kaupthing in order to manipulate its CDS spreads.

Deutsche sent Venky Vishwanathan on leave in the spring of 2015 because of his involvement in the Kaupthing scheme. In 2016, Reuters reported that Vishwanathan was suing Deutsche for unfair dismissal. The status of his case is unclear; he has not responded to my queries on LinkedIn.

An overview of the Kaupthing CLN transactions

In February 2008, at the time of the first meeting regarding the CDS spreads with Deutsche bankers, the Kaupthing management was smarting from steadily increasing financing cost; Kaupthing managers insisted the bank was unfairly targeted by hedge funds and were trying to figure out how Kaupthing could erase the image of weakness implied by the CDS spreads. Already at the first meeting with Venky Vishwanathan it was abundantly clear that Kaupthing was seeking to use own funds to influence the CDS spreads; that was the plan from the beginning – the question was just how to structure it in order to influence the CDS spreads most effectively.

The CDS scheme was developed further in the coming months as the pressure on Kaupthing increased: in spring 2008, the CDS spreads stood alarmingly at 900bp. Deutsche advised against Kaupthing’s original idea of its own direct involvement in the transactions. The solution was to find trusted clients of Kaupthing – Kevin Stanford and his wife Karen Millen, Tony Yerolemou and Skúli Þorvaldsson, all large clients of Kaupthing – who would in name own Chesterfield, the BVI company, entirely funded by Kaupthing; the transactions would be done via Chesterfield.

The Chesterfield transactions were done in August 2008. According to the SIC Report (p.26-28; in Icelandic), the CDS spreads changed on 10 August 2008, following the transaction, from 1000bp to 700bp. Though the spread diminished only for some days, it was deemed success, which should be repeated. For the second round, in September, the CLN transactions were done via another BVI company, Partridge, owned by Ólafur Ólafsson, domiciled in Switzerland, still a wealthy businessman, then Kaupthing’s second largest shareholder and a major borrower in Kaupthing. Again, the Partridge transactions were wholly funded by Kaupthing, organised by Deutsche on behalf of Kaupthing.

In total, Kaupthing paid €510m to Deutsche for the Chesterfield and Partridge trades, the last millions transferred to Deutsche from Kaupthing just as the bank teetered; it formally failed 9 October 2008. Emergency funding from the Icelandic Central Bank to Kaupthing of €500m was partly used to pay Deutsche as part of the Partridge transactions although the funding had been issued to safeguard Kaupthing’s UK operations (See the longer version on Icelog.)

Kaupthing accordingly lost the €510m because the two BVI companies had no assets to speak of, which made it clear from the beginning that should the trades go awry, the loans would be non-recoverable; a fact the liquidators noted, as did the Special Prosecutor in Iceland.

Al-Thani and the CLN trades that never happened

A very intriguing part of this story surfaced in the SIC Report (p.26-28): there had been plans for a third round of Kaupthing-funded CLN transactions through Brooks Trading Ltd, owned by a Qatari investor, Sheikh Mohamed Khalifa al Thani. Kaupthing agreed to a loan of €130m to Mink Trading, an al Thani company, in addition to a loan of $50m to Brooks Trading Ltd, another al Thani company, as up-front profit from the trades.

Again, the purpose of the loan to Mink Trading was to invest in CLN linked to Kaupthing’s CDS, again via Deutsche Bank in transactions structured as the Chesterfield and Partridge transactions. But Kaupthing ran out of time; the loan to Brooks Trading was paid out according to the SIC Report, not the loan to Mink Trading; the al Thani CLN transactions never happened.

Sheikh al Thani is a well-known name in Iceland from his role in another Kaupthing criminal case, the so-called al Thani case; although the case is commonly named after the Sheikh he was not charged (the $50m loan to Brooks Trading might have been connected to the real al Thani case, not the CLN transactions, according the the SIC Report). In the al Thani case the three Kaupthing managers, charged in the CLN case, and Ólafur Ólafsson were sentenced to three to 5 ½ years in prison. As in the CLN case, the bankers were charged for fraudulent lending, breach of fiduciary duty and market manipulation; Ólafsson was sentenced for market manipulation.

According to the SIC Report Kaupthing also agreed to lend Ólafsson €50m against profits from the Partridge trade but SIC documents do not show that the loan was issued.

The doggedly diligent liquidators

The liquidators of the two BVI companies, Stephen Akers and Mark McDonald, quickly seem to have sensed a potentially intriguing story behind the CDS transactions and had some impertinent questions for Deutsche Bank. When Deutsche was remarkably unwilling to answer their questions the liquidators took legal action against the bank in order to obtain documents, as seen in this UK court decision in February 2012.

In his affidavit in the 2012 Decision, Akers said: “It is very difficult to see how the transactions made commercial sense for the Companies.” – As the liquidators were to uncover the short answer here is that the transactions did not make sense for the companies, which were only a tool for Kaupthing managers, as Deutsche full well knew.

This can be gauged in detail from the 2014 consolidated particulars. Well documented, it recounts the whole saga behind the CLN transactions, inter alia the following:

Already at the initial meeting in February 2008 it was clear that Kaupthing’s only reason for setting up the schemes was to bring down its CDS spreads and Kaupthing would fund the transactions; Kaupthing was willing to pay Deutsche for reaching this goal and Deutsche agreed to assisting Kaupthing in reaching it, i.e. bringing down its CDS spreads; from Kaupthing, its most senior managers were involved; at Deutsche, senior staff in London worked on the plan (para 56). A larger group were kept informed by emails, amongst them Jan Olsson managing director of Deutsche and CEO of Deutsche in the Nordics.

After a slow start, the urgency increased in summer 2008: on 18 June 2008, Vishwanathan sent an email to the Kaupthing managers proposing a concrete strategy: “Kaupthing should fund the purchase of a CLN referenced to itself. DB, as the vendor of the CLN, would then hedge its exposure under the CLN, by selling Kaupthing CDS in the market, and this would have the desired effect of lowering Kaupthing’s CDS spread.” (para 62.)

A flurry of emails followed, also because Deutsche’s legal department was hard to please (para 68-69). The bank’s Global Reputational Risk Committee was involved. Kaupthing managers understood that Deutsche staff was “bit stressed about this from a ‘reputation’ point of view.” In July, Deutsche invited Hreiðar Már Sigurðsson and his family on a trip to Barcelona, i.e. paid for flights and hotel, where Sigurðsson attended DB’s Global Markets Conference and discussed the CDS scheme (para 75).

The conclusion was that Kaupthing could not be seen to go directly into the market in transactions linked to its own CDS. The solution was to set up a Luxembourg company for the CDS trades, as Sigurðsson explained in an email to Vishwanathan during the conference: Kaupthing’s lawyer would be “setting up the lux company for our trade” (sic), also offering to discuss further “the right structure that you (i.e. Deutsche) would be comfortable with.” (para 79). That same day, Vishwanathan sent an email to a colleague informing him he was working on “putting together a bespoke ETF for some of (Kaupthing’s) close high net worth clients to take a view on (Kaupthing) CDS…” (para 80).

Late July, Kaupthing’s lawyer in Luxembourg presented an overview in an email to Deutsche’s Shaheen Yusuf, including the ownership structure with the names of the four Kaupthing clients who owned Chesterfield. The presentation clearly stated that the funding, €125m, would come from Kaupthing and that the CLN used was part of a wider scheme where Deutsche would offer CDS for sale with a total nominal value of €250m (para 89). – This document included everything regarding the planned transactions, also the funding.

As all of this is documented in email exchanges between Kaupthing managers and Deutsche staff it is clear that when Deutsche claims, inter alia in its 2015 and 2016 Annual Reports it did not know a) that the funding came from Kaupthing – and – b) that the aim of the transactions was to lower Kaupthing’s CDS spread, it goes against documents, which Deutsche had on its system at the time and should still have.

Avoiding a paper trail

Given that Deutsche’s legal department and its Global Reputational Risk Committee had been worried, the overview and its detailed information on funding etc. was unavoidably a strong dosis for Deutsche to stomach. Yusuf called Kaupthing – it’s not clear if she spoke to Hreiðar Már Sigurðsson or Magnús Guðmundsson – but her mission was to ask Kaupthing to withdraw the presentation and replace it with a new one where the fact that Kaupthing was funding the transactions would be omitted. The Kaupthing Luxembourg lawyer quickly followed her instructions, sending another presentation, with the requested changes: Kaupthing was no longer referenced as the lender.

The BVI liquidators point out that there was a phone call and not an email, concluding this was done in order to avoid a paper trail at Deutsche (para 92-93).

When the Chesterfield trades were executed in August 2008, the effect was immediate, just as Deutsche bankers had promised (para 114). In an email to Vishwanathan Hreiðar Már Sigurðsson said it seemed “our Barcelona trip paid of” (sic) – the trip where the plans were finalised (para 115-116).

Indeed, so pleased were the Kaupthing managers that they decided to do another trade of the same kind (in spite of a very short-lasting effect) (para 117). This time, it would be through a company owned by Ólafur Ólafsson, very much a part of the Kaupthing’s inner circle and a close friend of the Kaupthing managers.

“Are u not paid to work for us?”

Due to force majeur, the second CDS transactions hardly registered: Lehman Brothers collapsed on the 15 September 2008, shaking the world’s financial system to its core. Two days later, Kaupthing’s CDS spread had deteriorated further and stood at record 1150bp. As if nothing had happened in the world of finance, Magnús Guðmundsson, clearly less than pleased, wrote in an email to Vishwanathan: “How can the CDS spread be were they are compare to our trade(.) Are u not paid to work for us? (sic)” (para 128).

This exchange clearly shows how Kaupthing saw Deutsche’s role – Deutsche was acting on behalf of Kaupthing, not for the owners of the two BVI companies. Both Kevin Stanford and Tony Yerolemou have stated they had no idea how the BVI companies in their name were used – they had no idea of the funds that flowed through their companies as Kaupthing strove to meet margin calls. – Interestingly, these are not the only examples of Kaupthing using clients’ companies without the owners’ knowledge.

The liquidators conclude that the nature of the transactions of Chesterfield and Partridge were unlawful as “they were intended to, and did, secretly manipulate Kaupthing’s CDS spreads and thereby the market for CDS referenced to Kaupthing, and the market for Kaupthing bonds.” (para 142-148, further 149-176.)

According to the liquidators, Deutsche Bank broke laws on market manipulation and market abuse not only in the UK but also in other countries where financial products, influenced by Deutsche’s unlawful activities, were traded. (para 143-145). This abuse and manipulation did not only affect Kaupthing’s CDS but also Kaupthing’s bonds as the manipulated CDS affected the pricing of Kaupthing bonds.

Further questions regarding the CDS transactions

In addition to market manipulation and being counterpart to trades Deutsche itself set up, the Kaupthing CLN transactions have other interesting aspects to ponder on.

Emails between Deutsche staff show how employees involved in the Kaupthing transactions were allegedly prepared to withhold information on the owners of the BVI companies from Deutsche’s own know-your-customer team. Also, the staff was aware of the reputational risk from being involved in transaction where a bank tried to influence its own CDS spreads.

There is nothing to indicate that this was done because the Deutsche bankers engaging with Kaupthing were less ethical than other colleagues or more prepared to stray away from the straight and narrow road of regulation – rather, that this was a way of working at the bank. It can only be assumed that in a case like this there was no guidance from the echelons of power at Deutsche, relevant to keep in mind given the enormous sums Deutsche has paid out over the years in fines, also in cases with criminal ramifications.

The CLN saga shows the inner workings of Deutsche, relevant to understand how the bank’s internal safeguarding against illegal activities were side-lined when up against the possibility of profit. Relevant for so many other cases of questionable conduct that have surfaced in the last few years. Intriguing to keep in mind regarding the latest Deutsche scandal: it’s role in Danske Bank’s money laundering in Estonia where $230bn were laundered in 2007 to 2015, where Deutsche seems to have handled around $180bn.

Another aspect is how keenly the Kaupthing managers honoured the agreement with Deutsche. Money was tight in August 2008 when the Chesterfield transaction was done. In September, money was quite literally running out and no doubt the three managers had a lot on their mind. Yet, they never lost focus on these transactions with Deutsche, diligently though with great effort meeting margin calls, even making use of the emergency lending from the Icelandic Central Bank. The managers have explained that Kaupthing’s relationship mattered greatly. Yet, given what was going on at the bank, the question still lingering in my mind why these transactions were apparently so profoundly important to the Kaupthing managers.

Deutsche Bank – the bank that paid €14.5bn(!) in fines March 2012-July 2018

Over the last few years, Deutsche Bank has been fighting regulators on all continents. In total, Deutsche paid fines of €14.5bn from March 2012 to July 2018 for criminal activity ranging from Libor fixing to money laundering, according to ZDF. And there might well be more to come as Deutsche is now involved in the largest money laundering saga of all times, Danske Bank’s laundering of $230bn from 2007 to 2015 where Deutsche allegedly handled close to $180bn of the $230bn.

Intriguingly, in June 2010 the SFO was looking at Deutsche’s role in the CDS trades, according to the Guardian. But as with so much of suspicious activities in UK banks around 2008 (and forever!) nothing more was heard of SFO’s investigation.

Deutsche has refuted having known about the realities of the CDS transactions – that Kaupthing was indeed funding the trades and doing it in order to lower its CDS spreads. However, the paper trail within the bank tells a very clear story, according to the liquidators: Deutsche full well knew the realities and thus took part in market manipulation that in the end affected not only the CDS spreads but, much more seriously, the price of Kaupthing’s bonds. The same was clear already from the SIC Reportand from the CLN criminal case in Iceland.

As mentioned earlier on Icelog, the CLN charges (in Icelandic) support and expand the evidence of Deutsche’s role in the CDS trades. The charges show that Deutsche made for example no attempt to be in contact with the Kaupthing clients who at least on paper were the owners of the two companies; Deutsche was solely in touch with Kaupthing. Inter alia, the owners were not averted regarding margin calls; Deutsche sent all claims directly to Kaupthing, apparently knowing full well where the funding was coming from and who was making the necessary decisions.

Another interesting question is who was on the other side of the CDS bets, i.e. who gained in the end when the Kaupthing-funded companies lost so miserably?

According to the Icelandic Prosecutor, the three Kaupthing bankers “claim they took it for granted that the CDS would be sold in the CDS market to independent investors and this is what they thought Deutsche Bank employees had promised. They were however not given any such guarantee. Indeed, Deutsche Bank itself bought a considerable part of the CDS and thus hedged its Kaupthing-related risk. Those charged also emphasised that Deutsche Bank should go into the market when the CDS spread was at its widest. That meant more profit for the CLN buyer Chesterfield (and also Partridge) but those charged did not in any way secure that this profit would benefit Kaupthing hf, which in the end financed the transactions in their entirety.”

Deutsche’s fees for the two CLN transactions amounted to €30m for the total CDS transactions of €510m. In addition, Deutsche will have profited from going into the market buying “a considerable part of the CDS” thus hedging its risk related to Kaupthing.

Effectively, Deutsche was not interested in having the realities of the case tested in court – it did not want to spell out in court its part in the Kaupthing market manipulation and it did not want to spell out it had itself been a counterpart in the trades. After years of legal wrangling, it chose to settle with Kaupthing and agreed to pay back €425m of the €510m Kaupthing paid to Deutsche for these transactions. – Another case of alleged banking fraud buried in the UK.

*Published by Kjarninn Iceland as an attachment to an open letter (in English but the attachments are linked to the Icelandic version) to Hreiðar Már Sigurðsson and Magnús Guðmundsson from the well-known UK retailer, Kevin Stanford. He and his ex-wife Karen Millen were clients of Icelandic banks, also of Kaupthing. – All emphasis above is mine.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Will special counsel Mueller surprise with Icelandic Russia-related stories?

The Russian Icelandic connections keep stimulating the fantasy. In a recent Bloomberg article Timothy L. O’Brien calls on special counsel Robert Mueller to “check out Iceland.” The facts are indeed elusive but Mueller and his team should be in an ace position to discover whatever there is to discover, via FL Group. If there is no story untold re Russia and Iceland, the unwillingness of the British government to challenge Russian interests is another intriguing Russia-related topic to explore.

“Iceland, Russia and Bayrock – some facts, less fiction” was my recent contribution to the fast growing compendium of articles on potential or alleged connections between nefarious Russian forces and Iceland. The recent Bloomberg article by Timothy L. O’Brien adds nothing new to the topic in terms of tangible facts.

The Russian oligarch Boris Berezovsky was one of those who early on aired the potential connection. Already in 2009, in a Sky interview that O’Brien mentions, Berezovsky made sweeping comments but gave no concrete evidence, as can be heard here in the seven minutes long interview.

What however Berezovsky says regarding London, the dirty money pouring into London is correct. That flow has been going on for a long time and will no doubt continue: it doesn’t seem to matter who is in power in Britain, the door to Russian money and dirty inflow in general is always open, serviced by the big banks and the enablers, such as accountants and lawyers, operating in London.

What Berezovsky really said

Asked how Putin and the oligarchs operated, Berezovsky said they bought assets all over the world but also took on a lot of debt. “They took a lot of credit from the banks and so they were not able to pay that back. And the best example is definitely Iceland. And you remember when lets say three months ago Russian government declared that they would help Iceland. And Russia is so strong that they’re able to help even a member of Nato. And their trick is very simple because Russian let’s say top level bureaucrats like Putin, like others and oligarchs together they created system how to operate on the West. How to use this fantastic money to buy assets and so and so. They found this very clever solution. They took a country and bought the country, which is member of Nato, which is not a member of EU. It means that regulation is different. They put a lot of money, dirty money in general, yeah.”

When asked further if Russians were buying high-end property in London with dirty money Berezovsky said this was indeed the case, all done to gain power: “The example which I gave you. As far as Iceland is concerned just confirmed realistically that Putin and his cronies made absolutely dirty money and tried to invest their money all over the world including Britain.”

This is very much Berezovsky but hardly a clear exposé. Exactly what the connection was, through the banks or the country as a whole isn’t clear. Sadly, Berezovsky died in 2013, under what some see as mysterious circumstances, others consider it a suicide. Incidentally, Berezovsky’s death is one of fourteen deaths in the UK involving Russians, enablers to Russian oligarchs or others with some Russian ties, recently investigated in four articles by Buzzfeed.

The funding of the Icelandic banks – yet again

In his Bloomberg article O’Brien visits the topic of the funding of the Icelandic banks. As I mentioned in my previous Russia blog, the rumours regarding the Russian Icelandic connections and the funding of the Icelandic banks were put to rest with the report of the Special Investigative Commission, SIC. The report analysed the funding the banks sought on international markets, from big banks that then turned into creditors when the banks failed.

O’Brien’s quotes Eva Joly the French investigative judge, now an MEP, who advised Icelandic authorities when they were taking the first steps towards investigating the operations of the then failed banks. Joly says that the Russian question should be asked. “There was a huge amount of money that came into these banks that wasn’t entirely explained by central bank lending,” Joly is quoted as saying, adding “Only Mafia-like groups fill a gap like that.”

I’m not sure where the misunderstanding crept in but of course the Icelandic central bank was not funding the Icelandic banks. As the SIC report clearly showed, the Icelandic banks, as most other banks, sought and found easy funding by issuing bonds abroad at the time when markets were flooded by cheap money. Prosecutor Ólafur Hauksson, who has been in charge of the nine-year banking investigations in Iceland, says to O’Brien that he and his team have not seen any evidence of money laundering but adds that the Icelandic investigations have not focused on international money flows via the banks.

As I pointed out in my earlier Russia blog, the Jody Kriss evidence, from court documents in his proceedings against Bayrock, the company connected to president Donald Trump, is again inconclusive. Something that Kriss himself points out; Kriss is quoting rumours and has nothing more to add to them.

Why and how would money have been laundered through Icelandic banks?

The main purpose of money laundering is to provide illicit money with licit origin. Money laundering in big banks like HSBC, Deutsche Bank and Wachovia is well documented and in general, patterns of money laundering are well established. The Russian Icelandic story will not be any better by repeating the scanty indications. We could turn the story around and ask: if the banks were really used by Russians or any other organized crime how would they have done it?

One pattern is so-called back-to-back loans, i.e. illicit money is deposited in a bank (which then ignores “know your customer” regulation) but taken out as a loan issued by that bank. That gives these funds a legitimate origin; they are now a loan. As far as I understand, there are no sign of this pattern in any of the Icelandic banks.

When Wachovia laundered money for Mexican drug lords cash was deposited with forex exchanges, doing business with Wachovia. The bank brought the funds to Wachovia branches in the US, either via wire transfers, travellers’ cheques or as part of the bank’s cash-moving operations. When the funds were then made available to the drug lords again in Mexico, it seemed as if the money was coming from the US, enough to give the illegitimate funds a legitimate sheen. Nothing like these operations was part of what the Icelandic banks were doing.

Money laundering outside the banks?

There might of course have been other ways of laundering money but again the question is from where to where. As I mentioned in my Russia blog, FL Group, the company connected to the Bayrock story, was short-lived but attracted and lost a spectacular amount of money. As did other Icelandic companies, which have since failed: there could be potential patterns of money laundering there though again there are no Russians in sight (except for Bayrock) – or simply examples of disastrously bad management.

Russians, or anyone else, certainly would not need Icelandic banks to move funds for example into the UK – the big banks were willing to and able to do it, as can be seen from the oligarchs and others with shady funds buying property in London. It was eye-opening to join one of the London tours organised by Kleptocracy Tours and see the various spectacular properties owned by Russian oligarchs here in London.

The Magnitsky Act was introduced in the US in 2012 but is only finding its way into UK law this year in the Criminal Finances Bill, meant to enable asset freezing and denying visa to foreign officials known to be corrupt and having violated human rights.

The Icelandic banks – the most investigated banks

There were indeed real connections to Russians in the Icelandic banks as I listed in my previous Russia blog. In addition, Kaupthing financed the super yacht Serene for Yuri Shefler with a loan of €79.5m according to a leaked overview of Kauthing lending, from September 2008. These customers were among Kaupthing non-Russian high-flying London customers, mostly clients in Kaupthing Luxembourg, such as Alshair Fiyaz, Simon Halabi, Mike Ashley and Robert and Vincent Tchenguiz.

None of the tangible evidence corroborates the story of the Icelandic banks being some gigantic Russian money laundering machine. That said, I have heard from investigators who claim they are about to unearth more material.

In the meantime we should not forget that Iceland has diligently been prosecuting bankers for financial assistance, breach of fiduciary duty and market manipulation – almost thirty bankers and others close to the banks have been sentenced to prison. Now that 2008 investigations are drawing to a close in Iceland, four Barclays bankers are facing charges in London, the first SFO case related to events in 2008, in a case very similar to one of the Icelandic cases, as I have pointed out earlier.

Exactly because the Icelandic banks have been so thoroughly investigated and so much is known about them, their clients etc., it is difficult to imagine there are humongous stories there waiting to be told. But perhaps Robert Mueller and his team will surprise us.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

The ‘puffin plot’ – a saga of international bankers and Icelandic greed

In a formal signing ceremony 16 January 2003 a group of Icelandic investors and the German bank Hauck & Aufhäuser purchased shares in a publicly-owned Icelandic bank. Paul Gatti represented the German bank, proudly airing the intension of being a long-term owner together with the Icelandic businessman Ólafur Ólafsson. What neither Gatti nor Ólafsson mentioned was that earlier that same day, at a meeting abroad, their representatives had signed a secret contract guaranteeing that the Icelandic bank Kaupthing, called ‘puffin’ in their emails, would finance the H&A purchase in Búnaðarbanki. A large share of the profit, 57,5 million USD, would accrue to Ólafsson via an offshore company, whereas 46,5 million USD was transferred to the offshore company Dekhill Advisors Limited, whose real owners remain unknown. Thus, Ólafsson and the H&A bankers fooled Icelandic authorities with the diligent help of advisors from Société General. – This 14 year old saga has surfaced now thanks to the Panama Papers. What emerges is a story of deception similar to the famous al Thani story, which incidentally sent Ólafsson and some of the Kaupthing managers involved in the ‘puffin plot’ to prison in 2015. Ólafsson is however still a wealthy businessman in Iceland.

The privatisation of the banking sector in Iceland started in 1998. By 2002 when the government announced it was ready to sell 45.8% in Búnaðarbanki, the agrarian bank, it announced that foreign investors would be a plus. When Ólafur Ólafsson, already a well-known businessman, had gathered a group of Icelandic investors, he informed the authorities that his group would include the a foreign investor.

At first, it seemed the French bank Société General would be a co-investor but that changed last minute. Instead of the large French bank came a small German bank no one had heard of, Hauck & Aufhäuser, represented by Peter Gatti, then a managing partner at H&A. But the ink of the purchase agreement had hardly dried when it was rumoured that H&A was only a front for Ólafsson.

Thirteen years later, a report by Reykjavík District judge Kjartan Björgvinsson, published in Iceland this week, confirms the rumours but the deception ran much deeper: through hidden agreements Ólafsson got his share in Búnaðarbanki more or less paid for by Kaupthing. Together with Kaupthing managers, two Société General advisers, an offshore expert in Luxembourg, Gatti and H&A legal adviser Martin Zeil, later a prominent FDP politician in Bayern, Ólafsson spun a web of lies and deceit. A few months after H&A pretended to buy into Búnaðarbanki the hidden agreements made an even greater sense when tiny Kaupthing bought the much larger Búnaðarbanki. Until Kaupthing collapsed in 2008 Ólafsson was Kaupthing’s second largest shareholder and, it can be argued, Kaupthing’s hidden mastermind.

The H&A deceit turned out to be only an exercise for a much more spectacular market manipulation. In the feverish atmosphere of September 2008, Ólafsson, following a similar pattern as in 2003, got a Qatari sheikh to borrow money from Kaupthing and pretend he bought 5.1% in Kaupthing as a proof of Kaupthing’s strength. Ólafsson was charged with market manipulation in 2015 and sentenced to 4 ½ years in prison, together with Kaupthing managers Sigurður Einarsson, Hreiðar Már Sigurðsson and Magnús Guðmundsson, all partners in Ólafsson’s H&A deceit.

Preparing the ‘puffin plot’

Two SocGen bankers, Michael Sautter and Ralf Darpe, worked closely with Ólafsson from autumn 2002 to prepare buying the 45.8% of Búnaðarbanki the Icelandic government intended to sell. Ólafsson gave the impression that SocGen would be the foreign co-investor with his holding company, Egla. Sautter, who had worked on bank privatisation in Israel and Greece, said in an interview with the Icelandic Morgunblaðið in September 2002 that strong core investors were better than a spread ownership, which was being discussed prior to the privatisation. In hindsight it’s easy to guess that the appearances of Ólafsson’s advisers were part of his orchestrated plot.

But something did not work out with SocGen: by mid December 2002 the bank withdrew from the joint venture with Ólafsson who asked for an extended deadline from the authorities to come up with new foreign co-investors. The SocGen bankers now offered to assist in finding a foreign investor and that’s how Ólafsson got introduced to H&A, Peter Gatti and Martin Zeil.

The privately held H&A came into being in 1998 when two private Frankfurt banks merged: 70% was owned by wealthy individuals, the rest held by BayernLB and two insurance companies.

Until last moment Ólafsson withheld who the foreign investor would be but assuring the authorities there would be one. And lo and behold, Peter Gatti showed up at the signing ceremony 16 January 2003, held in the afternoon in an old and elegant building in Reykjavík, formerly a public library. H&A bought the shares in Búnaðarbanki through Egla, Ólafsson’s holding company, which also meant that Ólafsson was in full control of the Búnaðarbanki shares.

At the ceremony in Reykjavík Gatti played the part of an enthusiastic investor, promising to bring contacts and knowledge to the Icelandic banking sector. To the media Ólafsson in his calmly assuring way praised the German bank, which would be valuable to Búnaðarbanki and Icelandic banking. “We chose the German bank,” he stated, “because they were the best for Búnaðarbanki and for our endeavours.”

The particular benefit for Búnaðarbanki never materialised but the arrangement certainly turned out to be extremely lucrative for Ólafsson and others involved. However, it wasn’t the agreement signed in Reykjavík but another one signed some hours earlier, far from Reykjavík, that did the trick.

The hidden agreements at the heart of the ‘puffin plot’

The other agreement, in two parts, signed far away from Reykjavík told a very different story than the show put on at the old library in Reykjavík.

That agreement came into being following hectic preparation by Guðmundur Hjaltason, who worked for Ólafsson, Sautter and Darpe, Gatti and Zeil, an offshore expert in Luxembourg Karim van den Ende and a group of Kaupthing bankers. The Kaupthing bankers were Sigurður Einarsson, Hreiðar Már Sigurðsson, Steingrímur Kárason, Bjarki Diego and Magnús Guðmundsson who have all been convicted of various fraud and sentenced to prison, and two others, Kristín Pétursdóttir, now an investor in Reykjavík and Eggert Hilmarsson, Kaupthing’s trusted lawyer in Luxembourg. Karim Van den Ende is a well known name in Iceland from his part in various dubious Kaupthing deals through his Luxembourg firm, KV Associates.

The drafts had been flying back and forth by email between the members this group. Three days before the signing ceremony Zeil was rather worried, as can be seen from an email published in the new report. One of his questions was:

Will or can Hauck & Aufhäuser be forced by Icelandic law to declare if it acts on its own behalf or as trustee or agent of a third party?

Zeil’s email, where he also asked for an independent legal opinion, caused a flurry of emails between the Kaupthing staff. Bjarki Diego concluded it would on the whole be best that “as few as possible would know about this.”

But how was the H&A investment presented at the H&A? According to Helmut Landwehr, a managing partner and board member at H&A at the time of the scam, who gave a statement to the Icelandic investigators the bank was never an investor in Iceland; H&A only held the shares for a client. Had there been an investment it would have needed to be approved by the H&A board. – This raises the question if Gatti said one thing in Iceland and another to his H&A colleagues, except of course for Zeil who operated with Gatti.

The offshored profits

The hidden agreement rested on offshore companies provided by van den Ende. Kaupthing set up an offshore company, Welling & Partners, that placed $35.5m, H&A’s part in the Búnaðarbanki share purchase, on an account with H&A, which then paid this sum to Icelandic authorities as a payment for its Búnaðarbanki purchase. In other words, H&A didn’t actually itself finance its purchase in the Icelandic bank; it was a front for Ólafsson. H&A was paid €1m for the service.

Then comes the really clever bit: H&A promised it would not sell to anyone but Welling & Partners – and it would sell its share at an agreed time for the same amount it had paid for it, $35.5m. When that time came, in 2005, the H&A share in Búnaðarbanki was worth quite a bit more, $104m to be precise.

Kaupthing then quietly bought the shares so as to release the profit – and here comes another interesting twist: this profit of over $100m went to two offshore companies: $57.5m to Marine Choice, owned by Ólafsson and $46.5m to a company called Dekhill Partners. Kaupthing then invested Ólafsson’s profit in various international companies.

In the new report the investigator points out that the owners of Dekhill Partners are nowhere named but strong indications point to Lýður and Ágúst Guðmundsson, Kaupthing’s largest shareholders who still own businesses in the UK and Iceland.

At some point in the process, which took around two years, the loans to Welling & Partners were not paid directly into Welling but channelled via other offshore companies. This is a common feature in the questionable deals in Icelandic banks, most likely done to hide from auditors and regulators big loans to companies with little or no assets to pledge.

Who profited from the ‘puffin plot’?

Ólafsson is born in 1957, holds a business degree from the University of Iceland and started early in business, first related to state-owned companies, most likely through family relations: his father was close to the Progressive party, the traditional agrarian party, and the coop movement. Ólafsson is known to have close ties to the Progressives and thought to be the party’s major sponsor, though mostly a hidden one.

Ólafsson was also close to Kaupthing from early on and was soon the bank’s second largest shareholder. The largest was Exista, owned by the Guðmundsson brothers.

There are other deals where Ólafsson has operated with foreigners who appeared as independent investors but at a closer scrutiny were only a front for Ólafsson and Kaupthing’s interests. The case that felled Ólafsson was the al Thani case: Mohammed Bin Khalifa al Thani announced in September 2008 a purchase of 5.1% in Kaupthing. The 0.1% over the 5% was important because it meant the purchase had to be flagged, made visible. To the Icelandic media Ólafsson announced the al Thani investment showed the great position and strength of Kaupthing.

In 2012, when the Special Prosecutor charged Sigurður Einarsson, Magnús Guðmundsson, Hreiðar Már Sigurðsson and Ólafsson for their part in the al Thani case it turned out that al Thani’s purchase was financed by Kaupthing and the lending fraudulent. Ólafsson was charged with market manipulation and sentenced in 2015 to 4 ½ years in prison. He had only been in prison for a brief period when laws were miraculously changed, shortening the period white-collar criminals need to spend in prison. Since his movements are restricted it drew some media attention when he crashed his helicopter (he escaped unharmed) shortly after leaving prison but he is electronically tagged and can’t leave the country until the prison sentence has passed.

The Guðmundsson brothers became closely connected to Kaupthing already in the late 1990s while Kaupthing was only a small private bank. Lýður, the younger brother was in 2014 sentenced to eight month in prison, five of which were suspended, for withholding information on trades in Exista, where he and his brother were the largest shareholders.

Both Ólafsson and the Guðmundsson brothers profited handsomely from their Kaupthing connections. Given Ólafsson’s role in the H&A alleged investment and later in the al Thani case it is safe to conclude that Ólafsson was a driving force in Kaupthing and could perhaps be called the bank’s mastermind.

In spite of being hit by Kaupthing’s collapse Ólafsson and the brothers are still fabulously wealthy with trophy assets in various countries. This may come as a surprise but a characteristic of the Icelandic way of banking was that loans to favoured clients had very light covenants and often insufficient pledges meaning the loans couldn’t be recovered, the underlying assets were protected from administrators and the banks would carry the losses. How much this applied to Ólafsson and Guðmundsson is hard to tell but yes, this was how the Icelandic banks treated certain clients like the banks’ largest shareholders and their close collaborators.

When Ólafsson was called to answer questions in the recent H&A investigation he refused to appear. After a legal challenge from the investigators and a Supreme Court ruling Ólafsson was obliged to show up. It turned out he didn’t remember very much.

Ólafsson engages a pr firm to take of his image. After the publication of the new report on the H&A purchase Ólafsson issued a statement. Far from addressing the issues at stake he said neither the state nor Icelanders had lost money on the purchase. Over the last months Ólafsson has waged a campaign against individual judges who dealt with his case, an unpleasant novelty in Iceland.

The Panama Papers added the bits needed to understand the H&A scam

In spite of Gatti’s presence at the signing ceremony in January 2003 the rumours continued, even more so as H&A was never very visible and then sold its share in Búnaðarbanki/Kaupthing. One person, Vilhjálmur Bjarnason, now an Independence party MP, did more than anyone to investigate the H&A purchase and keep the questions alive. Some years later, having scrutinised the H&A annual accounts he pointed out that the bank simply couldn’t have been the owner.

Much due to Bjarnason’s diligence the sale was twice investigated before 2010 by the Icelandic National Audit Office, which didn’t find anything suspicious. The investigation now has thoroughly confirmed Bjarnason’s doubts.

Both in earlier investigations and the recent H&A investigation Icelandic authorities have asked the German supervisors, Bundesanstalt für Finanzdienstleistungsaufschicht, BaFin, for information, a request that has never been granted. During the present investigation the investigators requested information on the H&A ownership in 2003. The BaFin answer was that it could only give that information to its Icelandic opposite number, the Icelandic FME. When FME made the request BaFin refused just the same – a shocking lack of German willingness to assist and hugely upsetting.

The BaFin seems to see its role more as a defender of German banking reputation than facilitating scrutiny of German banks.

The Icelandic Special Investigative Commission, SIC, set up in December 2008 to investigate the banking collapse did investigate the H&A purchase, exposed the role played by the offshore companies but could not identify the owners of the offshore companies involved and thus could not see who really profited.

The Panama leak last year exposed the beneficial owners of the offshore companies. That leak didn’t just oust the then Icelandic prime minister Sigmundur Davíð Gunnlaugsson, incidentally a leader of the Progressive party at the time but also threw up names familiar to those who had looked at the H&A purchase earlier.

Last summer, the Parliament Ombudsman, Tryggvi Gunnarsson who was one of the three members of the SIC made public he had new information regarding the H&A purchase, which should be investigated. The Alþingi then appointed District judge Kjartan Björgvinsson to investigate the matter.

By combining data the SIC had at its disposal and Panama documents the investigators were able to piece together the story above. However, Dekhill Partners was not connected to Mossack Fonseca where the Panama Papers originated, which means that the name of the owners isn’t found black on white. However, circumstantial evidence points at the Gudmundsson brothers.

How relevant is this old saga of privatisation fourteen years ago?

The ‘puffin plot’ saga is still relevant because some of the protagonists are still influential in Iceland and more importantly there is another wave of bank privatisation coming in Iceland. The Icelandic state owns Íslandsbanki, 98.2% in Landsbanki and 13% in Arion.

Four foreign funds and banks – Attestor Capital, Taconic Capital, Och-Ziff and Goldman Sachs – recently bought shares in Arion, in total 29.18% of Arion. Kaupskil, the holding company replacing Kaupthing (holding the rest of Kaupthing assets, owned by Kaupthing creditors) now owns 57.9% in Arion and then there is the 13% owned by the Icelandic state.

The new owners in Arion hold their shares via offshore vehicles and now Icelanders feel they are again being taken for a ride by opaque offshorised companies with unclear ownership. In its latest Statement on Iceland the IMF warned of a weak financial regulators, FME, open to political pressure, particularly worrying with the coming privatisation in mind. The Fund also warned that investors like the new investors in Arion were not the ideal long-term owners.

The palpable fear in Iceland is that these new owners are a new front for Icelandic businessmen like H&A. Although that is, to my mind, a fanciful idea, it shows the level of distrust. Icelanders have however learnt there is a good reason to fear offshorised owners.

The task ahead in re-privatising the Icelandic banks won’t be easy. The H&A saga shows that foreign banks can’t necessarily be trusted to give sound advice. The new owners in Arion are not ideal. The thought of again seeing Icelandic businessmen buying sizeable chunks of the Icelandic banks is unsettling, also with Ólafsson’s scam with H&A in mind.

It’s no less worrying seeing Icelandic pension funds, that traditionally refrain from exerting shareholder power, joining forces with Icelandic businessmen who then fill the void left by the funds to exert power well beyond their own shareholding. Or or… it’s easy to imagine various versions of horror scenarios.

In short, the nightmare scenario would be a new version of the old banking system where owners like Ólafsson and their closest collaborators rose to become not only the largest shareholders but the largest borrowers with access to covenant-light non-recoverable loans. Out of the relatively small ‘puffin plot’ Ólafsson pocketed $57.5m. The numbers rose in the coming years and so did the level of opacity. Ólafsson is still one of the wealthiest Icelanders, owning a shipping company, large property portfolio as well as some of Iceland’s finest horses.

In 2008, five years after the banks were fully privatised the game was up for the Icelandic banks. The country was in a state of turmoil and it ended in tears for so many, for example the thousands of small investors who had put their savings into the shares of the banks; Kaupthing had close to 40.000 shareholders. It all ended in tears… except for the small group of large shareholders and other favoured clients that enjoyed the light-covenant loans, which sustained them, even beyond the demise of the banks that enriched them.

Obs.: the text has been updated with some corrections, i.a. the state share sold in 2003 was 45.8% and not 48.8% as stated earlier.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Does Iceland have a better legal code to deal with dodgy banking?

“No” is the short answer. The Icelandic penal code on i.a. breach of fiduciary duty and market manipulation is similar to law in Western countries. The difference in Iceland was the swift awareness in autumn 2008 that there might be something worth investigating, later supported by setting up an Office of a Special Prosecutor, Special Investigating Commission and strengthening the financial supervision. Also, the Special Prosecutor quickly realised that behind the invariably complicated web of shell companies and transactions stories of fraud are in reality quite simple and follow the same patterns over and over again. This is why bankers and shareholders have been successfully prosecuted in Iceland – not because Iceland has better penal code.

“How come that Iceland is successfully prosecuting bankers, getting them sentenced to lengthy prison terms when no one else is doing it?” This is a question I keep being asked. The short answer is the one above but there is also a longer one.

Soon after Icelanders got used to the fact that the three large Icelandic banks had collapsed, in early October 2008, the country and the media was rife with rumours that something not entirely normal, not entirely legal, had been going on in the banks. Some tried to explain alleged irregularities by the unavoidable panic; that well, perhaps the bankers had in some cases overstepped the legal borderline, strayed into grey territories, as they fought to keep the banks as going concerns.

The Icelandic parliament, Alþingi, took two measures in December 2008 to clarify the collapse: it set up an investigative commission, The Special Investigative Commission, SIC, into the banking collapse – and it set up an Office of a Special Prosecutor, OSP.

The SIC already came across a number of cases it could not quite align with normal banking practices. These cases were outlined in its thorough report in April 2012 and it also presented its findings to the OSP. At the same time the financial supervisor, FME, was diligently reviewing the operations of the banks prior to the collapse. This meant that the OSP i.a. got input from these two institutions.

The Icelandic lesson from dealing with fraud related to the banks’ operations up to the banking collapse just proved the old saying: where there is a will there is a way.

A meagre and humble start

The beginnings of the OSP were not promising. First, no one applied for the job. Then a small-town sheriff was asked to apply and that is how Ólafur Hauksson, from Akranes across the bay from Reykjavík, got the job. This is a story often told before: Hauksson had never seen anything more serious than speed-driving, drunk driving, moonlighting, domestic violence, break-ins and drunken brawl, the average criminality in an Icelandic small town.

But Hauksson proved that give a person the occasion to shine and he/she very well might. He got funds to hire staff, three prosecutors were hired. Slowly slowly, the charges emerged. Slowly slowly, bankers started to pack to go on an unexpected trip, sent by the Supreme Court, to Snæfellsnes, the beautiful peninsula visible from Reykjavík, to an old farm, Kvíabryggja, a prison for non-violent prisoners.

Last year, following a system change, the OSP was moved into a bigger structure, the Office of County Prosecutor. This time, several people applied to lead the new institution. Hauksson was among the applicants and landed the job.

Digging out the simple truth from entangled webs of emails, shell companies and transactions

The main stories emerging from the collapse cases so far have revolved around market manipulation and breach of fiduciary duty. The real lesson here is the same as everywhere else: these cases look complicated, there are mountains of documents to read, often complicated web of shell companies and offshore companies, money floating around. Interestingly, phone tapping has been used successfully and there are also recordings from the old banks.

However, as in all such cases the underlying stories tend to be simple: the ways to commit a crime are not myriad. Think Enron: looks complicated, with all of the above – at the bottom, a simple story how losses were hidden from shareholders. Another entangled web is the Savings & Loan scandals in the US in the 1980s, nota bene where cases were really investigated and people sentenced to prison.

And these things do not happen by themselves. In every case it takes more than one to do all the necessary things. A prosecutor then decides whose deeds are grave enough to prosecute, who bears the responsibility etc.

Considering how little has been done i.a. in the UK to investigate the banks’ operations leading to the autumn 2008 banking collapse there and considering the screamingly obvious inactions by authorities in Luxembourg regarding banks – all the worst cases in Iceland have ties to the banks’ operations in Luxembourg – it is ironic that the OSP would have been a lot less successful were it not for a fruitful cooperation with these two countries. Authorities in both countries have carried out house searches and assisted in finding and identifying documents relevant for the OSP’s work. Yes, that is hugely ironic…

Market manipulation: burying shares like drug dealers with too much cash

Icelandic cases of market manipulation where bankers have been sentenced have mainly been carried out in two ways: through the banks’ own trading and by parking the banks’ shares into shell companies, invariably owned by clients with some particularly cosy ties to the banks and/or the banks’ shareholders.

Although Landsbanki and Kaupthing, Glitnir to a much lesser extent, were successfully running high interest rates internet accounts, to fund their operations (Landsbanki and the ill-fated Icesave), all three banks relied on selling bonds on international markets. This funding kept the banks going like mills with water. When funding dried up in summer 2007 it was clear that the banks would come to a grinding halt.

That is also what foreign banks sensed, quickly starting to call in loans and, with sinking asset prices, making margin calls on the big Icelandic businesses, i.e. the banks’ main shareholders and their closest partners. Since Icelandic bank shares were the collaterals in most of these loans (after all, the banks had lent the large shareholders money to buy their shares, another aspect that made Icelandic banks weak), it was clear that the markets would be flooded with Icelandic bank shares if the margin calls went through.

Faced with this the Icelandic banks decided to increase the lending to their largest clients – yes, all of them large and the largest shareholders in the banks – in order to prevent this flooding. The feeling when reading the court rulings in these cases is that the banks were like drug dealers with more cash than they can stash, needing to bury it etc.; i.e. the shares were buried in various companies and these transactions were funded by the banks.

Lending on contracts with no provisions to hinder possible losses

Breach of fiduciary duty has figured prominently in banking collapse cases leading to imprisonment. These cases all revolve in some way around lending where the bank carries all the risk, where eventual losses, were they to arise, would always fall on the bank, i.e. losses were foreseeable.

It seems to me that there are some Irish cases very similar to the Icelandic ones of foreseeable losses, i.e. the management didn’t seem to have the interest of the banks and their shareholders at heart but assisting individual clients beyond rhyme and reason.

These Icelandic loan agreements were often only agreed on by the banks’ managers, i.e. outside of regular processes, without the knowledge of credit committees etc. There would then be lower-placed trusted lieutenants who organised the lending. In some cases they have also been charged and sentenced, in some cases not.

Thus, the banks lend in such a way, apparently knowingly, that would the borrower not be able to pay, it would lead to the bank losing money. Here it is important to keep in mind that these banks were public companies with thousands of shareholders – Kaupthing had well over thirty thousand shareholders – losing money on bad lending.

“No society can tolerate that certain parts of it are beyond law and justice” – well, some can…

From reading the SIC report it is clear that some cases have been prosecuted, others not. There was too much of this going on but yes, the managers and the top tier, in some cases also shareholders, have been targeted by the OSP.

It is important to keep in mind that bankers in Iceland have not been sentenced for stupid or unwise decisions but for actions which the Supreme Court has then ruled were criminal actions.

When I talked to Hauksson following the conviction in the so-called al Thani case, in February 2015, he pointed out that the Supreme Court’s decisions showed “that it is possible to bring complicated financial cases to court and get conviction. Building up the expertise has been a long process but the ruling today demonstrates that setting up an office, which didn’t exist earlier, was fully justified. No society can tolerate that certain parts of it are beyond law and justice.”

For some reason, countries like the US and the UK, with old and esteemed legal traditions have in many cases decided to fine rather than prosecute for financial crimes, thereby showing the opposite of the Icelandic examples show – the US and the UK have indeed at times shown that yes, certain parts of society are indeed beyond law and justice. That has sadly been the UK and the US lessons of the financial calamities of 2008.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Iceland’s recovery: myths and reality (or sound basics, decent policies, luck and no miracle)

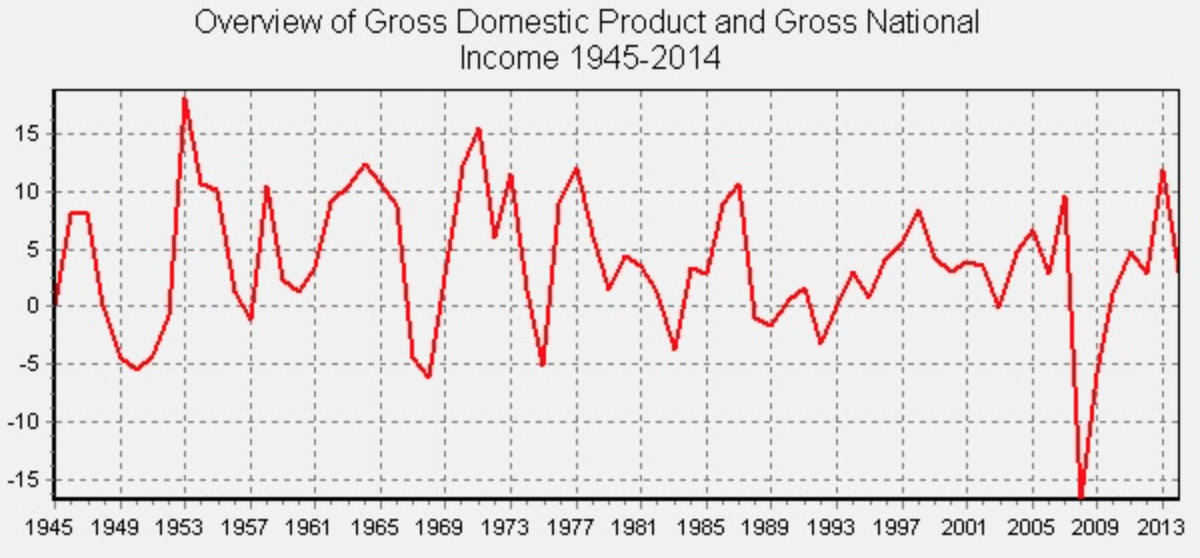

Icelandic authorities ignored warnings before October 2008 on the expanded banking system threatening financial stability but the shock of 90% of the financial system collapsing focused minds. Disciplined by an International Monetary Fund program, Iceland applied classic crisis measures such as write-down of debt and capital controls. But in times of shock economic measures are not enough: Special Prosecutor and a Special Investigative Committee helped to counteract widespread distrust. Perhaps most importantly, Iceland enjoys sound public institutions and entered the crisis with stellar public finances. Pure luck, i.e. low oil prices and a flow of spending-happy tourists, helped. Iceland is a small economy and all in all lessons for bigger countries may be limited except that even in a small economy recovery does not depend on a one-trick wonder.

“The medium-term prospects for the Icelandic economy remain enviable,” the International Monetary Fund, IMF, wrote in its 2007 Article IV Consultation

Concluding Statement, though pointing out there were however things to worry about: the banking system with its foreign operations looked ominous, having grown from one gross domestic product, GDP, in 2003 to ten fold the GDP by 2008. In early October 2008 the enviable medium-term prospect were clouded by an unenviable banking collapse.

All through 2008, as thunderclouds gathered on the horizon, the Central Bank of Iceland, CBI, and the coalition government of social democrats led by the Independence party (conservative) staunchly and with arrogance ignored foreign advice and warnings. Yet, when finally forced to act on October 6 2008, Icelandic authorities did so sensibly by passing an Emergency Act (Act no. 125/2008; see here an overview of legislation related to the restructuring of the banks and here more broadly on economic measures).

Iceland entered an IMF program in November 2008, aimed at restoring confidence and stabilising the economy, in addition to a loan of $2.1bn. In total, assistance from the IMF and several countries amounted to ca. $10bn, roughly the GDP of Iceland that year.

In spite of mostly sensible measures political turmoil and demonstrations forced the “collapse government” from power: it was replaced on February 1 2009 by a left coalition of the Left Green party, led by the social democrats, which won the elections in spring that year. In spite of relentless criticism at the time, both governments progressed in dragging Iceland out of the banking mess.

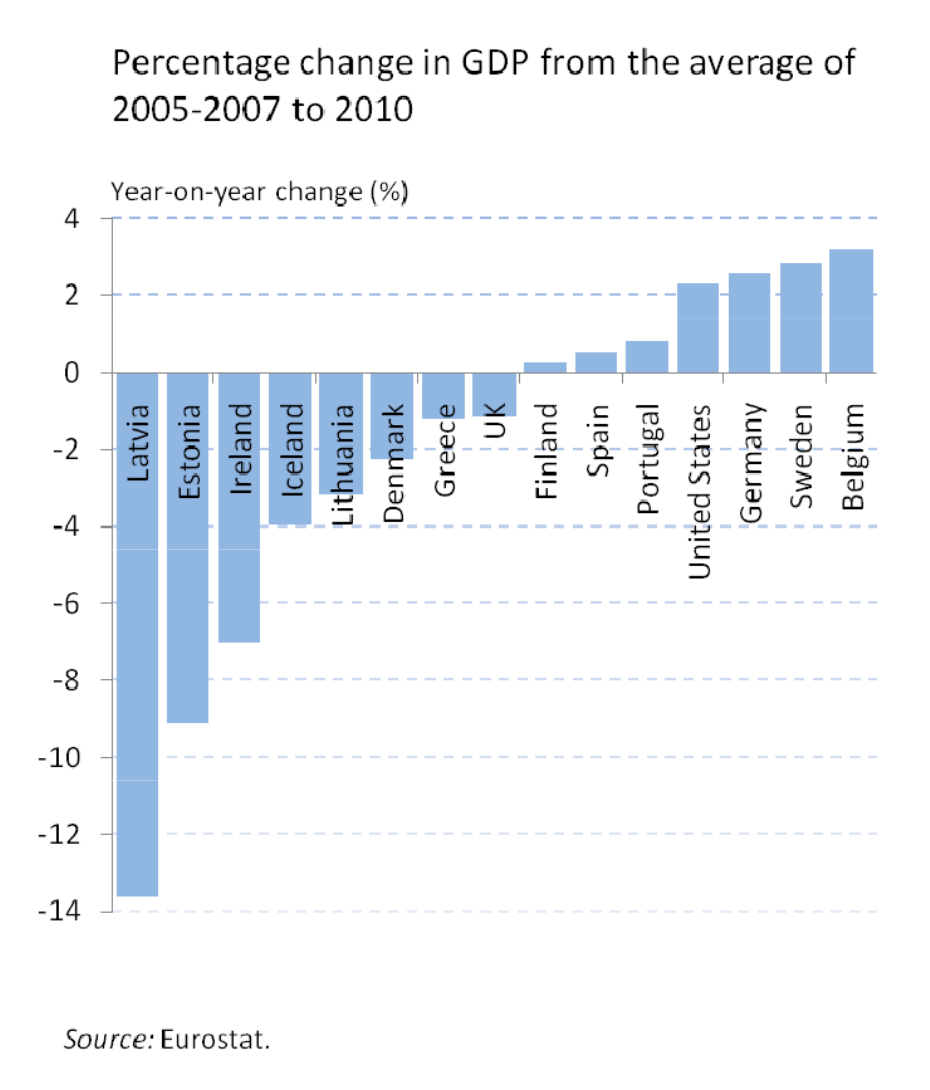

After the GDP contracted by 4% in the first three years the Icelandic economy was already back to growth summer 2011 and is now in its fifth year of economic growth. In 2015, Iceland became the first European country, hit by crisis in 2008-2010, to surpass its pre-crisis peak of economic output.

Iceland is now doing well in economic terms and yet the soul is lagging behind. Trust in the established political parties has collapsed: instead, the Pirate party, which has never been in government, enjoys over 30% following in opinion polls.

Compared to Ireland and Greece, Iceland’s recovery has been speedy, giving rise to questions as to why so quick and could this apparent Icelandic success story be applied elsewhere. Interestingly, much of the focus of that debate is very narrow and in reality not aimed at clarifying the Icelandic recovery but at proving or disproving aspects of austerity, the euro or both.

Unfortunately, much of this debate is misleading because it is based on three persistent myths of the Icelandic recovery: that Iceland avoided austerity, did not save its banks and that the country defaulted. All three statements are wrong: Iceland has not avoided austerity, it did save some banks though not the three largest ones and did not default.

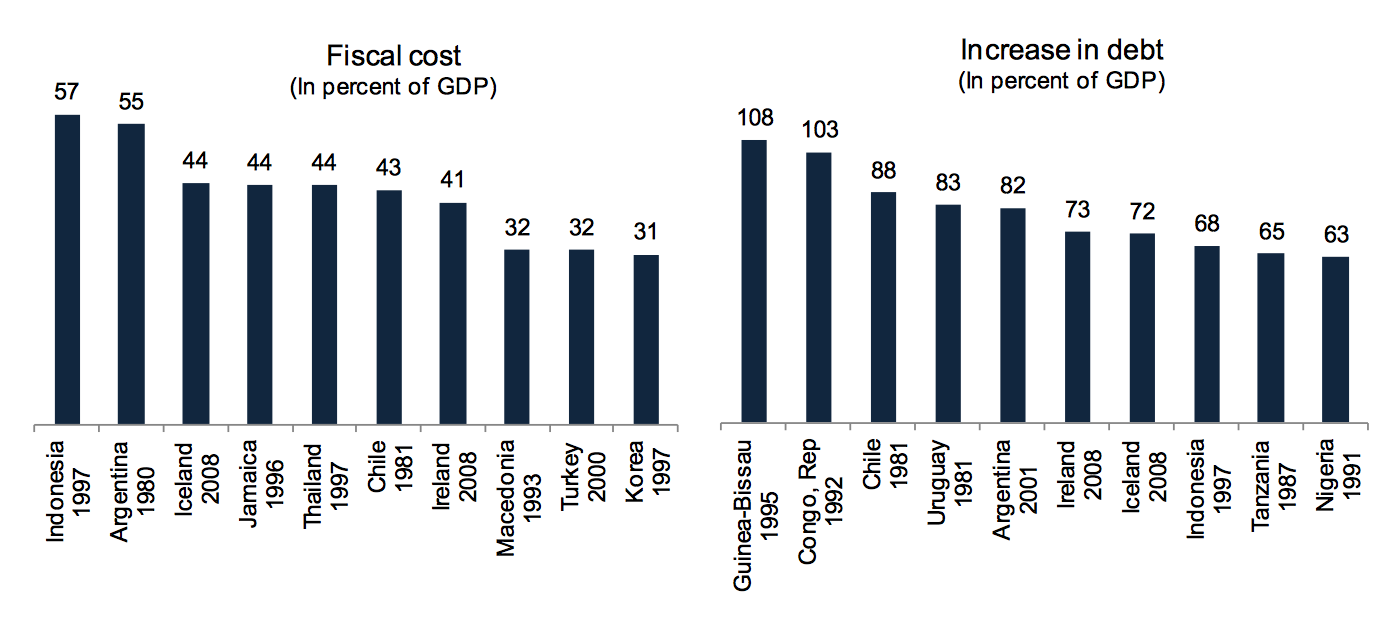

Indeed, the high cost of the Icelandic collapse is often ignored, amounting to 20-25% of GDP. Yet, not as high as feared to begin with: the IMF estimated it could be as much as 40%. The net fiscal cost of supporting and restructuring the banks is, according to the IMF 19.2% of GDP.

Costliest banking crisis since 1970; Luc Laeven and Fabián Valencia.

As to lessons to avoid the kind of shock Iceland suffered nothing can be learnt without a thorough investigation as to what happened, which is why I believe the report, a lesson in itself, by the Special Investigative Commission, SIC, in 2010 was fundamental. Tackling eventual crime, as by setting up the Office of the Special Prosecutor, is important to restore trust. Recovering from a collapse of this magnitude is not only about economic measures and there certainly is no one-trick fix.

On specific issues of the economy it is doubtful that Iceland, a micro economy, can be a lesson to other countries but in general, the lessons are simple: sound public finances and sound public institutions are always essential but especially so in times of crisis.

In general: small economies fall and bounce fast(er than big ones)

The path of the Icelandic economy over the past fifty years has been a path up mountains and down deep valleys. Admittedly, the banking collapse was a major shock, entirely man-made in a country used to swings according to whims of fishing stocks, the last one being in the last years of the 1990s.

(Statistics, Iceland)

Sound public finances, sound institutions

What matters most in a crisis country? Cleary a myriad of things but in hindsight, if a country is heading for a major crisis make sure the public finances are in a sound state and public authorities and institutions staffed with competent people, working for the general good of society and not special interests – admittedly not a trivial thing.

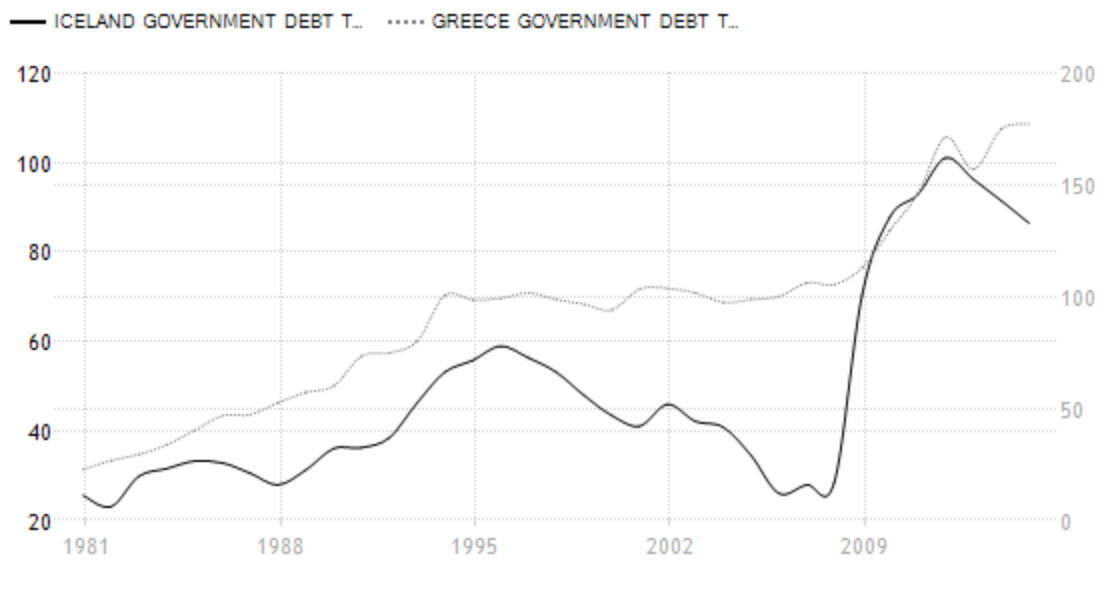

Since 1980 Icelandic sovereign debt to GDP was on average 48.67%, topped at almost 60% around the crisis in late 1990s and had been going down after that. Compare with Greece.

Trading Economics

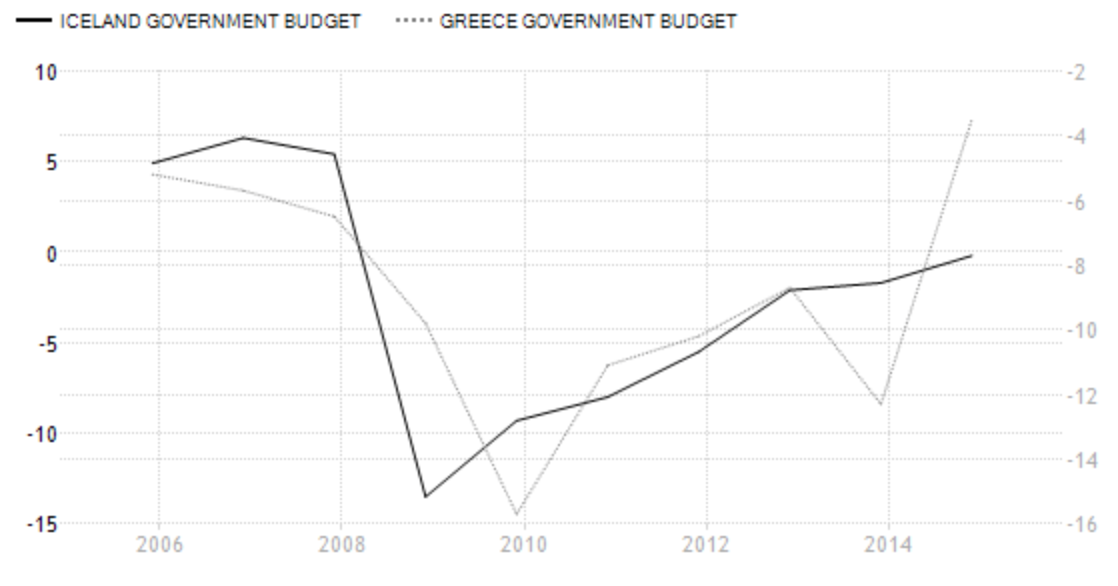

Same with the public budget: there was a surplus of 5-6% in the years up to 2008, against an average of -1.15% of GDP from 1998 to 2014. With a shocking deficit of 13.5% in 2009 it has since steadily improved, pointing to a balanced budget this year and a tiny surplus forecasted for next year. Again, compare with Greece.

Trading Economics

As to institutions, the CBI has been crucial in prodding the necessary recovery policies; much more so after change of board of governors in early 2009. Sound institutions and low corruption is the opposite of Greece, where national statistics were faulty for more than a decade (see my Elstat saga here).

Events in 2008

In early 2007, with sound state finances and fiscal strength the situation in Iceland seemed good. The banks felt invincible after narrowly surviving the mini crisis on 2006 following scrutiny from banks and rating agencies (the most famous paper at the time was by Danske Bank’s Lars Christensen).

Icelanders were keen on convincing the world that everything was fine. The Icelandic Chamber of Commerce hired Frederic Mishkin, then professor at Columbia, and Icelandic economist Tryggvi Þór Herbertsson to write a report, Financial Stability in Iceland, published in May 2006. Although not oblivious to certain risks, such as a weak financial regulator, they were beating the drum for the soundness of the Icelandic economy.

But like in fairy tales there was one major weakness in the economy: a banking system with assets, which by 2008 amounted to ten times the country’s GDP. Among economists it is common knowledge that rapidly growing financial sector leads to deterioration in lending. In Iceland, this was blissfully ignored (and in hindsight, not only in Iceland: Royal Bank of Scotland is an example).

Instead, the banking system was perceived to be the glory of Icelandic policies in a country that had only ever known wealth from the sea. Finance was the new oceans in which to cast nets and there seemed to be plenty to catch.

In early 2008 things had however taken a worrying turn: the value of the króna was declining rapidly, posing problems for highly indebted households – 15% of their loans were in foreign currency, i.a. practically all car loans. The country as a whole is dependent on imports and with prices going up, inflation rose, which hit borrowers; consumer-price indexed, CPI, loans (due to chronic inflation for decades) are the most common loans.

Iceland had been flush with foreign currency, mainly from three sources: the Icelandic banks sought funding on international markets; they offered high interest rates accounts abroad – most of these funds came to Iceland or flowed through the banks there (often en route to Luxembourg) – and then there was a hefty carry trade as high interest rates in Iceland attracted short- and long-term investors.

“How safe are your savings?” Channel 4 (very informative to watch) asked when its economic editor Faisal Islam visited Iceland in early March 2008. CBI governor Davíð Oddsson informed him the banks were sound and the state debtless. Helping the banks would not be “too much for the state to swallow (and here Oddsson hesitated) if it wanted to swallow it.” – Yet, timidly the UK Financial Services Authority, FSA, warned savers to pay attention not only to the interest rates but where the deposits were insured the point being that Landsbanki’s Icesave accounts, a UK branch of the Icelandic bank, were insured under the Icelandic insurance scheme.

The 2010 SIC report recounts in detail how Icelandic authorities ignored or refused advise all through 2008, refused to admit the threat of a teetering banking system, blamed it all on hedge funds and soldiered on with no plan.

The first crisis measure: Emergency Act Oct. 6 2008

Facing a collapsing banking system did focus the minds of politicians and key public servants who over the weekend of October 4 to 5 finally realised that the banks were beyond salvation. The Emergency Act, passed on October 6 2008 laid the foundation for splitting up the banks. Not into classic good and bad bank but into domestic and foreign operations, well adapted to alleviating the risk for Iceland due to the foreign operations of the over-extended banks.

The three old banks – Kaupthing, Glitnir and Landsbanki – kept their old names as estates whereas the new banks eventually got new names, first with the adjective “Nýi,” “new,” later respectively called Arion bank, Íslandsbanki and Landsbankinn. Following the split, creditors of the three banks own 87% of Arion and 95% of Íslandsbanki, with the state owning the remaining share. Due to Icesave Landsbanki was a different case, where the state first owned 81.33%, now 97.9%.

In addition to laying the foundation for the new banks, one paragraph of the Emergency Act showed a fundamental foresight:

In dividing the estate of a bankrupt financial undertaking, claims for deposits, pursuant to the Act on on (sic) Deposit Guarantees and an Investor Compensation Scheme, shall have priority as provided for in Article 112, Paragraph 1 of the Act on Bankruptcy etc.

By making deposits a priority claim in the collapsed banks interests of depositors were better secured than had been previously (and normally is elsewhere).

When 90% of a financial system is swept away keeping payment systems functioning is a major challenge. As one participant in these operations later told me the systems were down for no more than ca. five or ten minutes during these fateful days. All main institutions, except of course the three banks, withstood the severe test of unprecedented turmoil, no mean feat.

The coming months and years saw the continuation of these first crisis measures.